1. Introduction

Despite their name, rare disorders are relatively common, affecting almost 3,5 - 6,9 % of world population and more than 70% of them display a pediatric onset [

1]. Main causes of rare diseases are in our DNA: 70% of them recognize a genetic defect [

1] and the number of genes related to a specific disorder is increasing rapidly, exceeding the 4500 threshold in 2024 (OMIM database accessed on 20/08/2025).

Pediatric genetic syndromes (PGS) are a growing and heterogeneous group of congenital disorders characterized by a multi-systemic presentation, with a strong prevalence of neurocognitive impairment [

2]. These conditions are related to genomic defects of highly variable types and sizes: from anomalies in chromosomal number or structure, to single base pair variations affecting coding and non-coding genomic sequence [

3]. Such genotypic and phenotypic complexity entails an equally complex diagnostic process [

4,

5].

Inherited metabolic diseases (IMDs) constitute a considerable slice of rare pediatric disorders, numbering nearly 1450 conditions according to last estimates [

6]. IMDs result from impairments in a specific biochemical pathway, although defects might not always be detectable through biochemical tests [

7].

For rare diseases, and for IMDs in particular, new sequencing techniques have drastically improved diagnostic yield, bridging the gap left behind by traditional approaches [

8].

Still, the large use of whole exome or genome sequencing (respectively WES and WGS) has a few side effects, one over all the generation of diagnostic hypotheses that possibly diverge from original clinical suspicion and need a field validation [

8]. This scenario perfectly fits IMDs and PGS: these two large and growing groups of conditions display strongly overlapping phenotypes, that could easily mislead clinicians, regardless of their experience. Bearing in mind the convergence between IMDs and PGS is crucial when defining clinical and molecular approach to pediatric cases, in order to avoid missed diagnoses and treatments.

Especially for IMD, achieving rapidly the right diagnosis could make the difference: the earlier targeted therapies are started, the better the effects. Multidisciplinary teams are the shortcut for diagnostic odisseys, especially in hub Centers [

9].

Here we describe our experience from a Third Level Hospital in North of Italy in managing and diagnosing rare pediatric diseases. We will investigate possible redflags that may have helped in avoiding diagnostic (and treatment) delay, pointing out benefits of a close cooperation embracing pediatricians and geneticists when facing rare congenital disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to explore the importance of multidisciplinary approach to mis-diagnosed cases and to deepen our knowledge about phenotypical overlap between IMDs and PGS, we retrospectively reviewed clinical charts of patients that were referred alternatively to Genetic or to IMDs outpatient Clinics at the SC Paediatrics, Clinica De Marchi, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan in the last five years. Clinical data were retrieved from electronic and paper medical records of any patient wrongly referred to one of these Services. Recorded information was de-identified and managed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

We collected data about final diagnosis, referral request, clinical presentation, laboratory and imaging investigations, and any molecular test performed. Also, we evaluated time gap between first access at our Hospital and achievement of final diagnosis. All variants related to the diagnosed condition were reviewed, verified and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were re-classified according to ACMG guidelines [

10].

3. Results

Our cohort is composed by 13 pediatric patients, 8 males and 5 females, with a mean age of 5 years (range 0-11 years). Patients were subsequently divided according to diagnostic processes: the first group consisted of 6 patients who were initially evaluated by a medical geneticist but ultimately received an IMD diagnosis (IMD group). The second group included 7 children (two of which brothers) with a reverse diagnostic process: despite suspicion of a metabolic disorder, a final diagnosis of a PGS was made (PGS group). Molecular information about each patient together with data concerning diagnostic iter is reported in

Table 1.

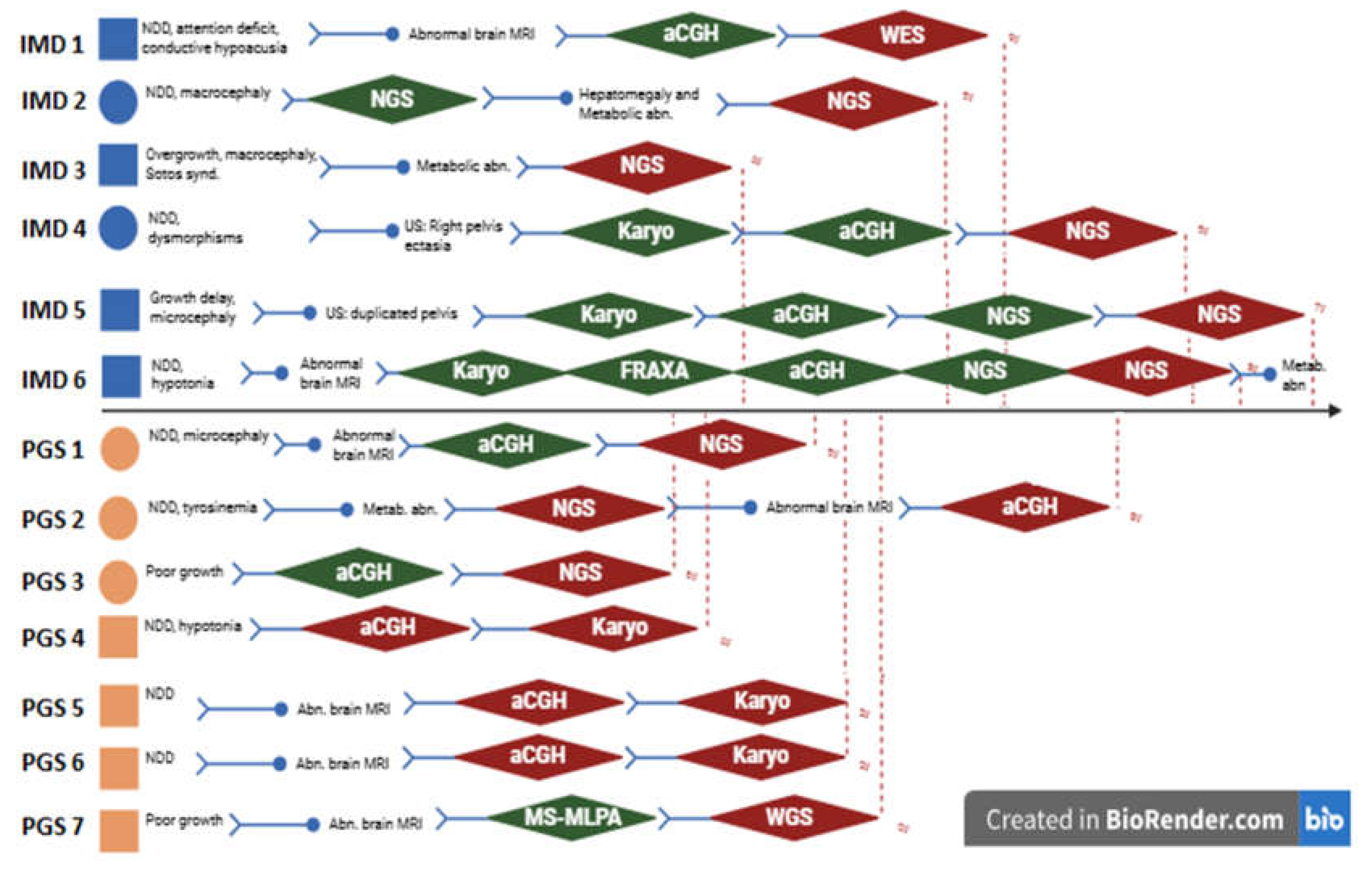

Figure 1.

A simplified representation of diagnostic iter, starting from the referral request. Each patient is represented by a square (males) or a circle (females), in blue (IMD group) or in orange (PGS group). Green rhombus represent a normal genetic analysis, red one a pathogenic test. Re d dotted line indicates the end of the diagnostic iter. Abbreviations: abd: abdominal, abn: abnormalities, aCGH: array CGH, FRAXA: X-fragile test, Karyo: Karyotype, IMD: inherited metabolic disorder; MBT: metabolic blood tests, Metab.: metabolic, MRI: magnetic resomnance imaging, NDD: neurodevelopmental disorder, NGS: Next generation sequencing tests, PGS: pediatric genetic syndrome, WES: whole exome sequencing, WGS: whole genome sequencing, y: years.

Figure 1.

A simplified representation of diagnostic iter, starting from the referral request. Each patient is represented by a square (males) or a circle (females), in blue (IMD group) or in orange (PGS group). Green rhombus represent a normal genetic analysis, red one a pathogenic test. Re d dotted line indicates the end of the diagnostic iter. Abbreviations: abd: abdominal, abn: abnormalities, aCGH: array CGH, FRAXA: X-fragile test, Karyo: Karyotype, IMD: inherited metabolic disorder; MBT: metabolic blood tests, Metab.: metabolic, MRI: magnetic resomnance imaging, NDD: neurodevelopmental disorder, NGS: Next generation sequencing tests, PGS: pediatric genetic syndrome, WES: whole exome sequencing, WGS: whole genome sequencing, y: years.

Figure 1 globally resumes referral requests and diagnostic steps that were made for each patient to reach the diagnosis. A total number of 14 not diagnostic analyses were performed, among which 6 array-CGH (aCGH), 3 sequencing (collectively named after next generation sequencing (NGS)) and 3 karyotypes. Globally, median age at diagnosis was 5 years (Q1: 4 - Q4:9 years), median diagnostic delay was 13 months (Q1: 5 - Q4:96). Comparing the two groups, IMDs median age at diagnosis was 6 years (Q1: 5 - Q4: 9) with 16 months of time gap between first access and molecular definition; PGS display a smaller time gap (median 9 months, Q1: 4 - Q4: 96) and a younger median age at diagnosis (4 years) (see

Table 1).

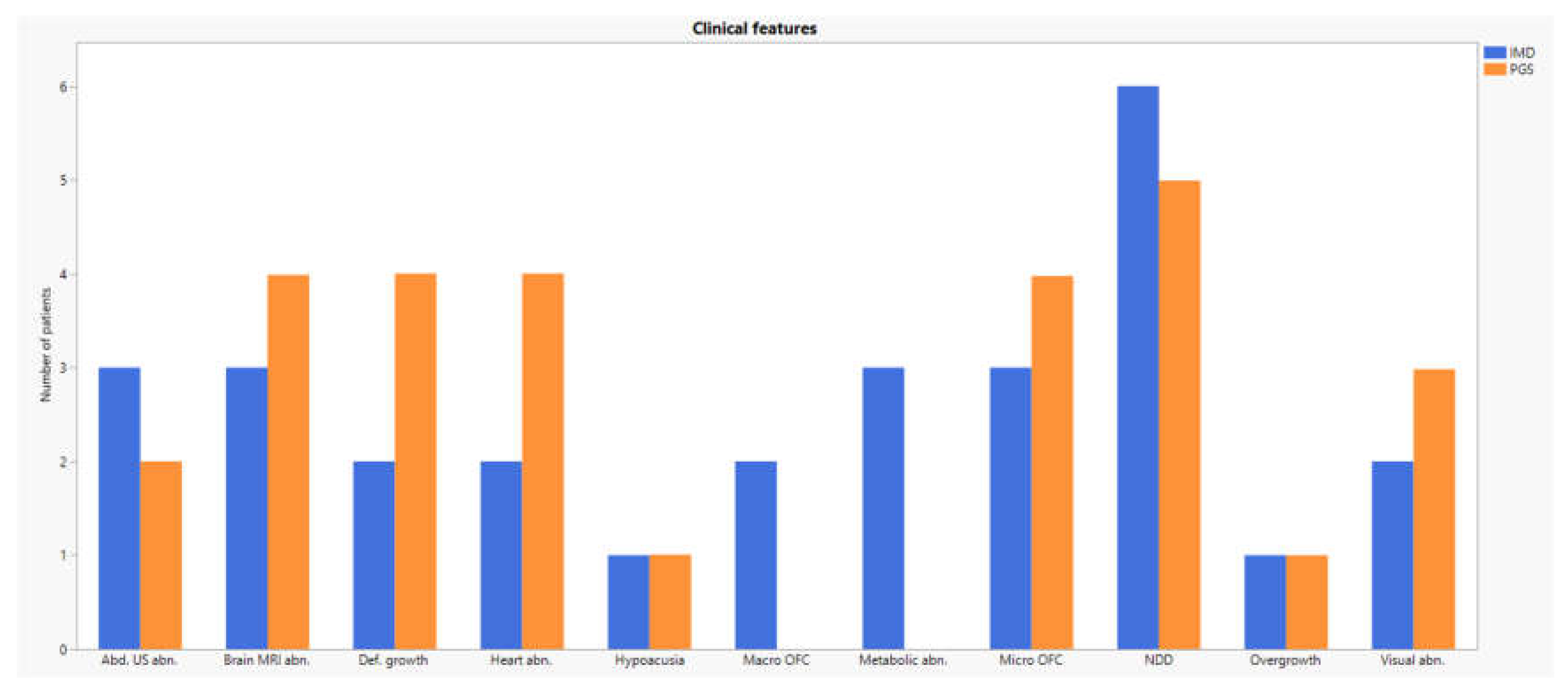

Most phenotypical features were shared between the two groups (see

Figure 2 and

Table 2).

The presence of a variable degree of neurocognitive impairment was almost invariably present (84,6 %), together with growth impairment. Anomalies in brain imaging were frequent, particularly in PGS group (4/7). Defective eye and ear function was occasionally reported (38,5% and 15,4% respectively), as well as heart (42,9) and inside organs affections (62,5).

4. Discussion

IMDs and PGS represent a challenging ground for both clinical geneticists and pediatricians. The extent of phenotypical overlap and the growing complexity of genetic background, paired with milder manifestations, give reasons to difficulties in referring children to the correct medical branch.

We reviewed clinical charts of 13 patients wrongly referred to Genetic or IMDs outpatient clinic in our Hospital and divided them into two groups according to final diagnosis (IMDs and PGS).

An outstanding point is that referral requests are often similar, with a strong prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in both groups (11/13). Hypotonia, dysmorphysms and growth defects are also frequent and equally reported in both categories. Overall, our results testify the significant clinical overlap between IMDs and PGS that critically fuels inappropriate specialist referrals. As a consequence, setting phenotypical boundaries between these two groups of conditions may not only be challenging, but self-defeating. Gathering IMDs and PGS together instead comes out as a better approach that may help to avoid pitfalls and diagnostic odysseys. Likewise, all different clinicians involved in diagnosis and management of rare pediatric congenital conditions should join up in multidisciplinary teams, in order to gain an all-around point of view of undiagnosed patients.

From a molecular point of view, it is to notice that patients belonging to IMD group often display a straighter diagnostic process compared to those of the PGS one.

In fact, most patients of the PGS group were correctly re-allocated based on cytogenetic analyses. In one girl (PGS 2) the diagnosis of a 22q13.33 deletion including SHANK3 (MIM#606230) was masked by the newborn label of tyrosinemia.

On the other hand, the windy road experienced by patients first referred to clinical geneticists further testifies the large fan of differential hypothesis that could mislead the diagnosis. Especially in past years, the lack of wide and comprehensive analyses troubled the diagnostic iter; in such a setting pinpointing the right diagnosis was a clinicians’ task, strongly dependent on personal experience. To date, the availability of genome wide tests partially overcomes these difficulties. In our cohort three patients (IMD 1, IMD 4 and PGS 7), despite their wrong first referral, were correctly addressed after the result of comprehensive genetic testing.

Still, new sequencing technologies are not a stand-alone diagnostic tool: molecular data always need their phenotypical counterpart to be trustworthy [

5]. This cross-check is apparently at hand for IMDs, whose biological impairments could be often detectable through blood examinations, but is for sure trickier in PGS, which increasing number goes at steady pace with difficulties in establishing genotype-phenotype correlations.

Nonetheless, what emerges from recent literature [

11,

12] is that suspected IMDs might hide more pitfalls than expected. On one hand, wide genome sequencing have exposed these conditions as a considerable part of pediatric undiagnosed disease [

8]. On the other, isolated molecular approach in IMDs often is not enough, needing biochemical tests to confirm the diagnosis. In this perspective, non-targeted metabolomic analyses are now emerging as a valuable tool for interpreting genetic variants but are not universally applicable to IMDs yet [

11].

Targeted therapies are now available for many IMDs, significantly improving their clinical outcomes, but benefits strongly rely on timing: the earlier the diagnosis and treatment, the better the effects.

Although limited by the small number of patients, in 3 of our patients a final diagnosis of a lysosomal storage disease (Muchopolysaccharidosis, MPS) was achieved. We take these metabolic conditions as a paradigm of how challenging it is to distinguish IMDs from PGS and of how this has knock on effect on the therapeutic side. Despite clinical overlap to PGS, red flag to suspect MPS in children include cognitive impairment with a variable but progressive course and ever coarser facial traits. MPS are currently treatable, both using enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and/or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), with significant benefits for disease manifestations [

13]. Any clinician dealing a child with developmental delay, should always bear in mind MPS and IMDs, not only to shorten diagnostic delays, but above all to prolong the therapeutic effects.

Our data globally confirm the importance of multidisciplinary approach when facing rare pediatric diseases [

9]: shared discussions of complex cases among pediatricians, geneticists and laboratory is the way to improve our clinical results, especially in hub Centers.

5. Conclusions

The present extensive clinical review for the first time inquiries about the clinical convergence among IMDs and PGS, that drives misdiagnoses and therapeutic delays.

Our data suggest that the distinction between these groups of conditions is often blurred, making the isolated specialist diagnostic approach not only ineffective, but also potentially harmful. Setting up multidisciplinary diagnostic pathways, where geneticists, pediatricians, and Laboratory work synergically, represents the key to achieve greater diagnostic accuracy and to improve clinical management, paving the way for a better approach to rare pediatric diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., F.F., and F.M.; methodology, G.B.M.; formal analysis, P.F., I.B., L.P., M.I.; investigation, D.M., G.S., F.T., F.F., and F.M..; data curation, G.B.M; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and T.F.; supervision, C.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to retrospective nature of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

part of the authors of this publication is a member of the European Reference Network on Rare Congenital Malformations and Rare Intellectual Disability ERN-ITHACA [EU Framework Partnership Agreement ID: 3HP-HP-FPA ERN-01-2016/739516]. The Authors are warmly grateful to families for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG |

American College of Medical Genetics |

| ERT |

Enzyme Replacement Therapy |

| HSCT |

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| IMDs |

Inherited metabolic diseases |

| MPS |

Muchopolysaccharidosis |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing |

| PGSs |

Pediatric Genetic Syndromes |

| SNV |

Single Nucleotide Variant |

| WES |

Whole Exome Sequencing |

| WGS |

Whole Genome Sequencing |

References

- Nguengang Wakap S, Lambert DM, Olry A, et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28(2):165-173. [CrossRef]

- Lee CE, Singleton KS, Wallin M, Faundez V. Rare Genetic Diseases: Nature's Experiments on Human Development. iScience. 2020;23(5):101123. [CrossRef]

- Wright CF, FitzPatrick DR, Firth HV. Paediatric genomics: diagnosing rare disease in children. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(5):325. [CrossRef]

- Hong J, Lee D, Hwang A, Kim T, Ryu HY, Choi J. Rare disease genomics and precision medicine. Genomics Inform. 2024;22(1):28. Published 2024 Dec 3. [CrossRef]

- Schuler BA, Nelson ET, Koziura M, Cogan JD, Hamid R, Phillips JA 3rd. Lessons learned: next-generation sequencing applied to undiagnosed genetic diseases. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(7):e154942. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira CR, Rahman S, Keller M, Zschocke J; ICIMD Advisory Group. An international classification of inherited metabolic disorders (ICIMD). J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44(1):164-177. [CrossRef]

- Morava E, Rahman S, Peters V, Baumgartner MR, Patterson M, Zschocke J. Quo vadis: the re-definition of "inborn metabolic diseases". J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38(6):1003-1006. [CrossRef]

- Furuta Y, Tinker RJ, Hamid R, et al. A review of multiple diagnostic approaches in the undiagnosed diseases network to identify inherited metabolic diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19(1):427. Published 2024 Nov 14. [CrossRef]

- Fecarotta S, Vaccaro L, Verde A, et al. Combined biochemical profiling and DNA sequencing in the expanded newborn screening for inherited metabolic diseases: the experience in an Italian reference center. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20(1):38. Published 2025 Jan 24. [CrossRef]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015 May;17(5):405-24. Epub 2015 Mar 5. PMID: 25741868; PMCID: PMC4544753. [CrossRef]

- Alaimo JT, Glinton KE, Liu N, et al. Integrated analysis of metabolomic profiling and exome data supplements sequence variant interpretation, classification, and diagnosis. Genet Med. 2020;22(9):1560-1566. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Xiao J, Gijavanekar C, et al. Comparison of Untargeted Metabolomic Profiling vs Traditional Metabolic Screening to Identify Inborn Errors of Metabolism. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2114155. Published 2021 Jul 1. [CrossRef]

- Moro E. Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomolecules. 2021;11(7):964. Published 2021 Jun 30. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).