Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

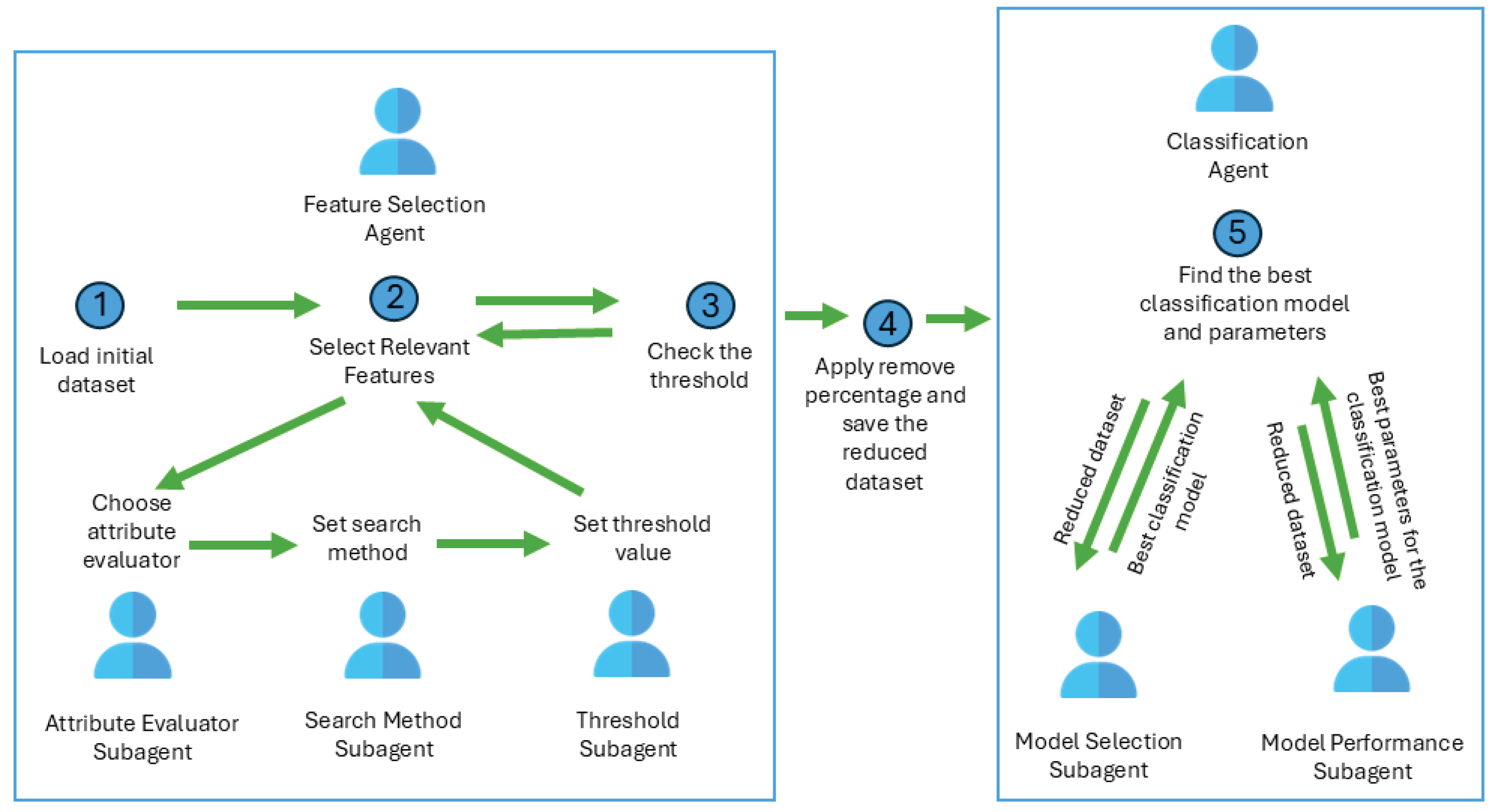

Intelligent Agents Based on Feature Selection for Time Improvement

- loads the initial medical dataset;

- finds the optimum subset in terms of accuracy and time taken to build models;

- if the threshold is reached, then sends the reduced dataset to Classification Agent.

- receives the reduced dataset from Feature Selection Agent;

- finds the best model and the best model configuration;

- sends the final model to the chatbot to be used for medical diagnosis.

- applies different evaluation methods to compute the relevance of an attribute (InfoGain, GainRation, Correlation, RelieF);

- uses search method (Ranker) for finding the relevant features that will be included in a specific subset of data;

- applies different threshold values to decide if the attribute is relevant and will be kept in the subset.

- learns the medical data with different models (decision trees, naïve bayes, deep learning neural networks);

- chooses the best model considering the model performance in terms of accuracy and time.

- finds the best model configuration;

- send the optimum model to the system’s chatbot to be used in medical diagnosis.

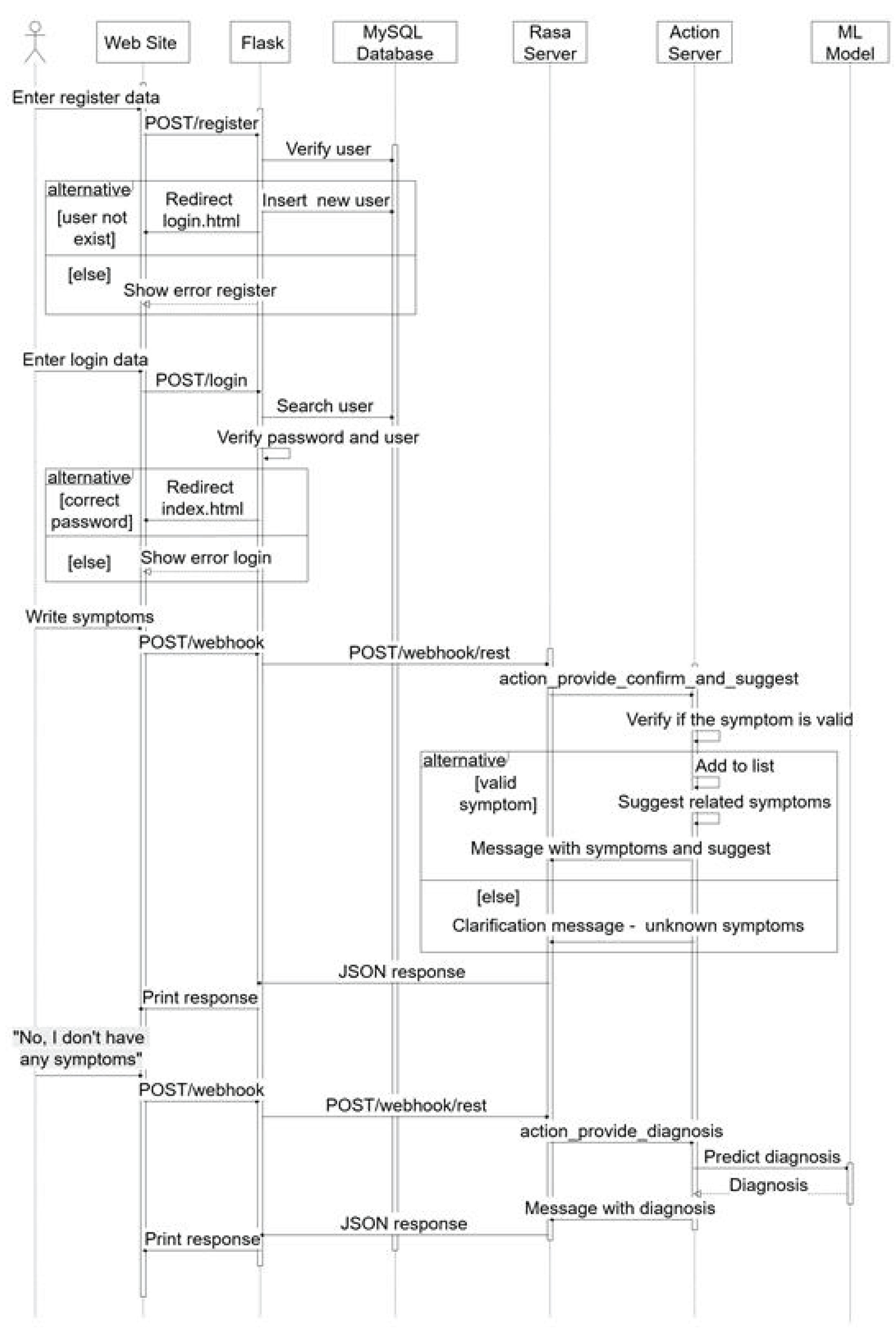

Medical Diagnosis System Using the Best Discovered Learning Model

- The user sends the symptoms via POST/webhook;

- The Flask Server forwards the POST/webhook/rest to the Rasa Server;

-

Race Server runs action_provide_diagnosis_and_suggest:

- o

-

Checks if the symptom is valid.

- ✓

- If it’s valid, add it to the list and suggest other symptoms.

- ✓

- Otherwise, it returns a message that the symptom has not been recognized.

- A JSON response is sent to the Web Site with the symptoms and symptom suggestions.

- The user sends the message “No, I don’t have any symptoms” via POST/webhook.

- A new POST/webhook/rest call is made to the Race Server.

-

action_provide_diagnosis shall be executed, which:

- o

- Sends the data to the model for prediction.

- o

- Gets a diagnosis.

- o

- Replies with a JSON message containing the diagnostic results.

3. Experimental Results

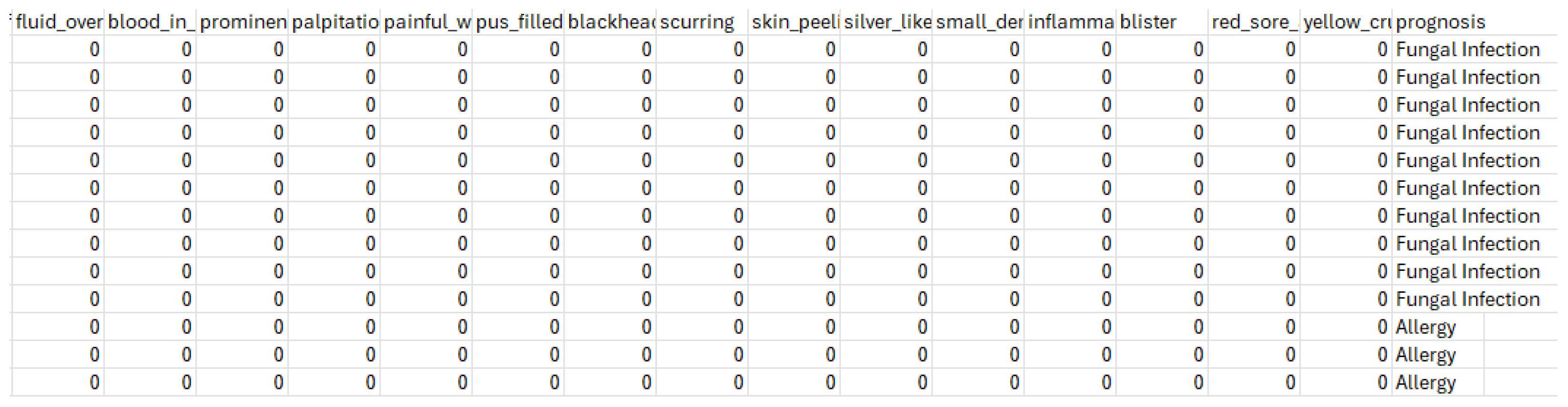

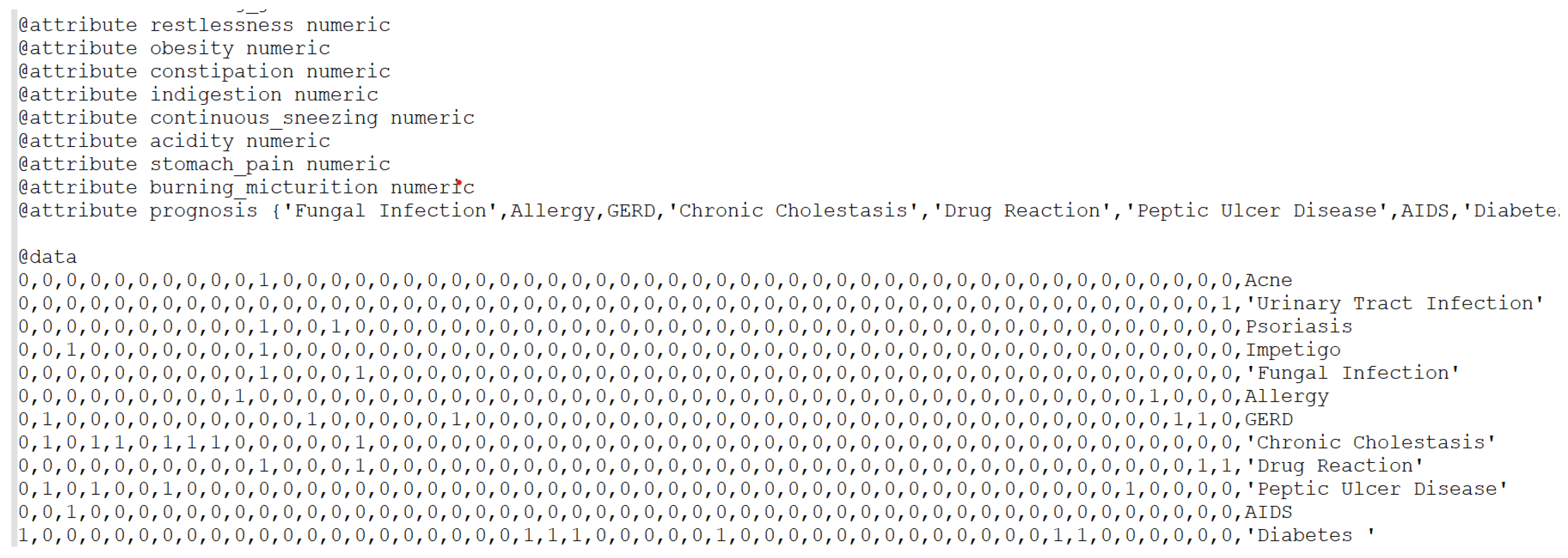

3.1. Symptom-Disease Prediction Dataset Description

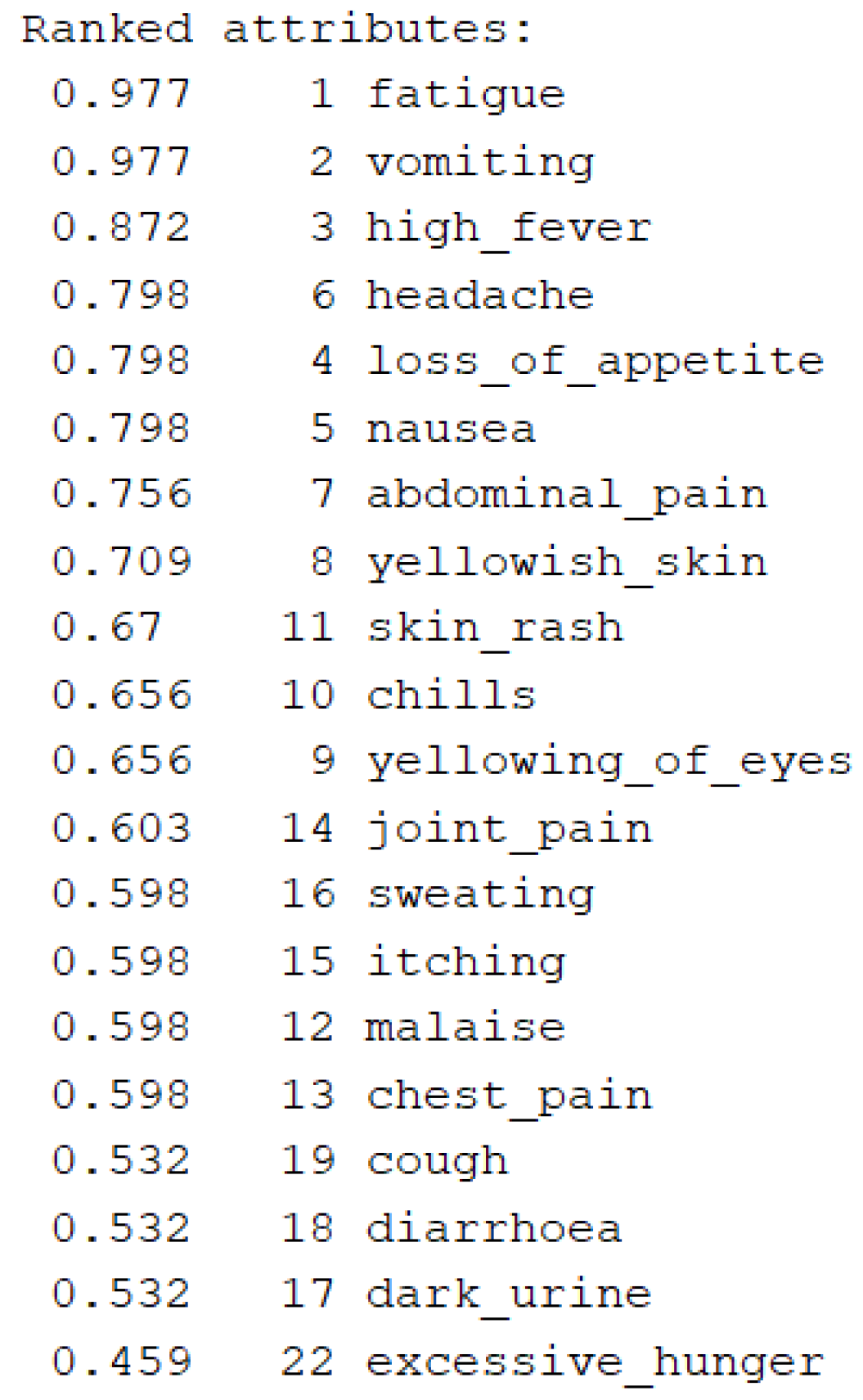

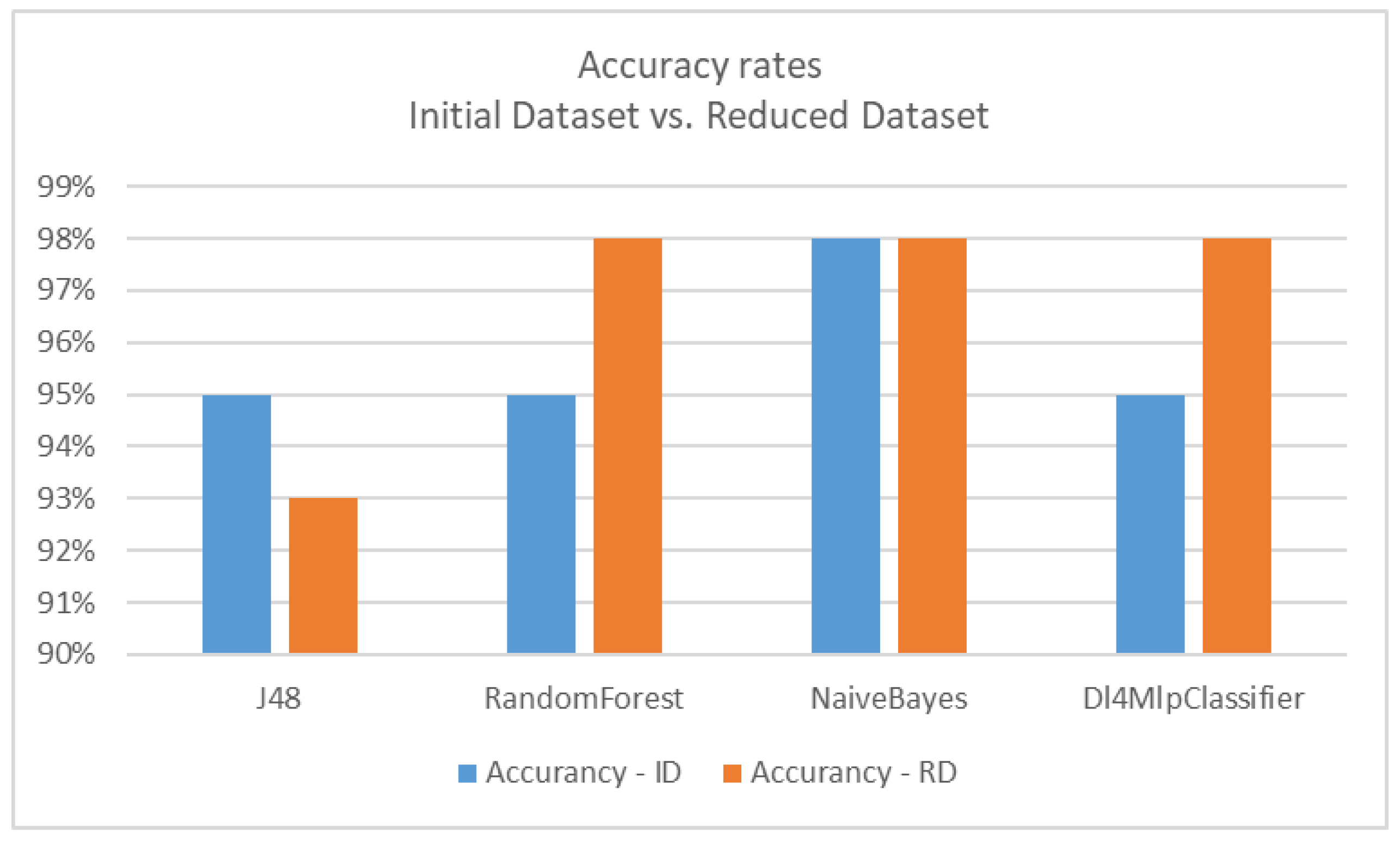

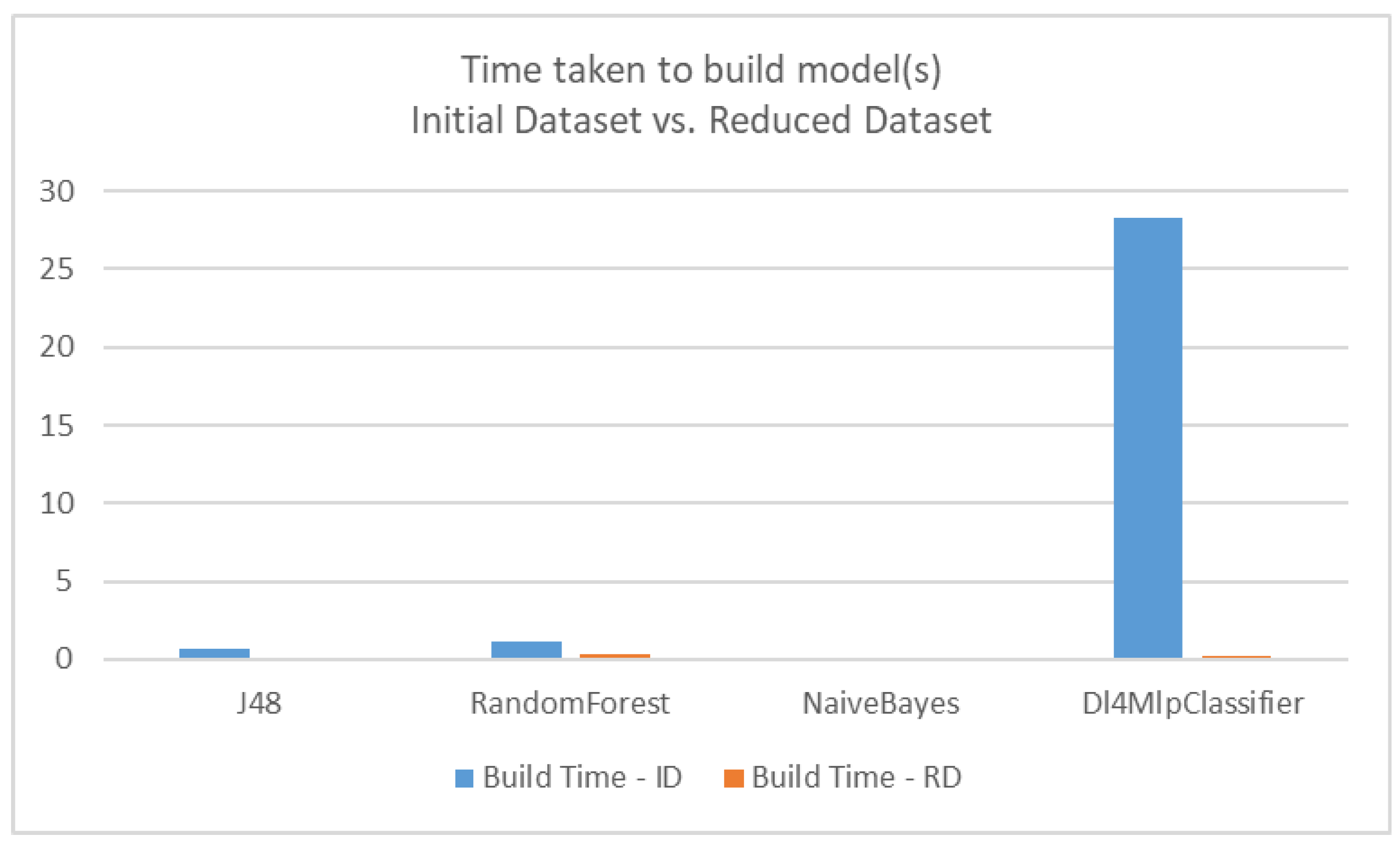

3.2. Feature Selection and Classification

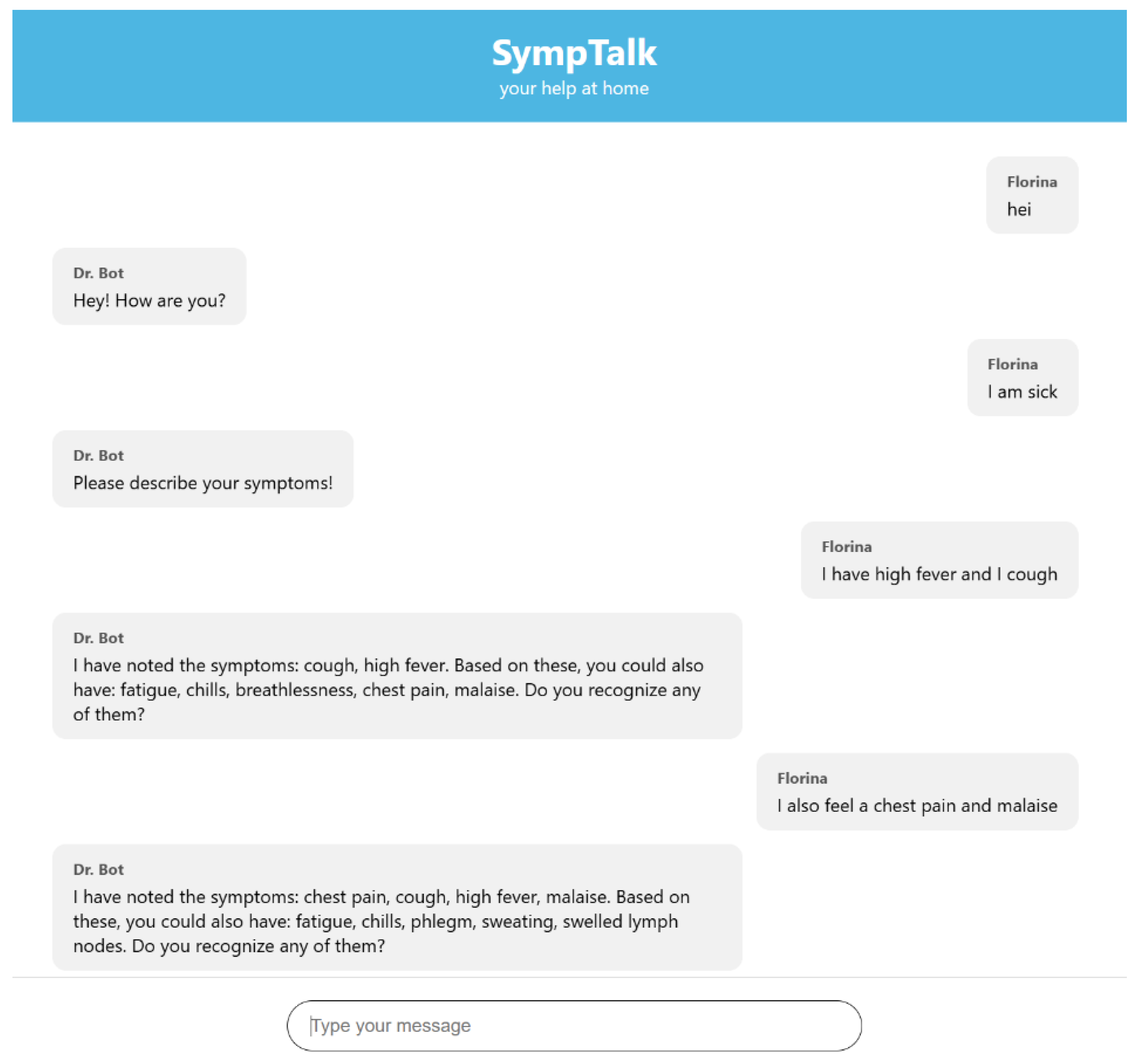

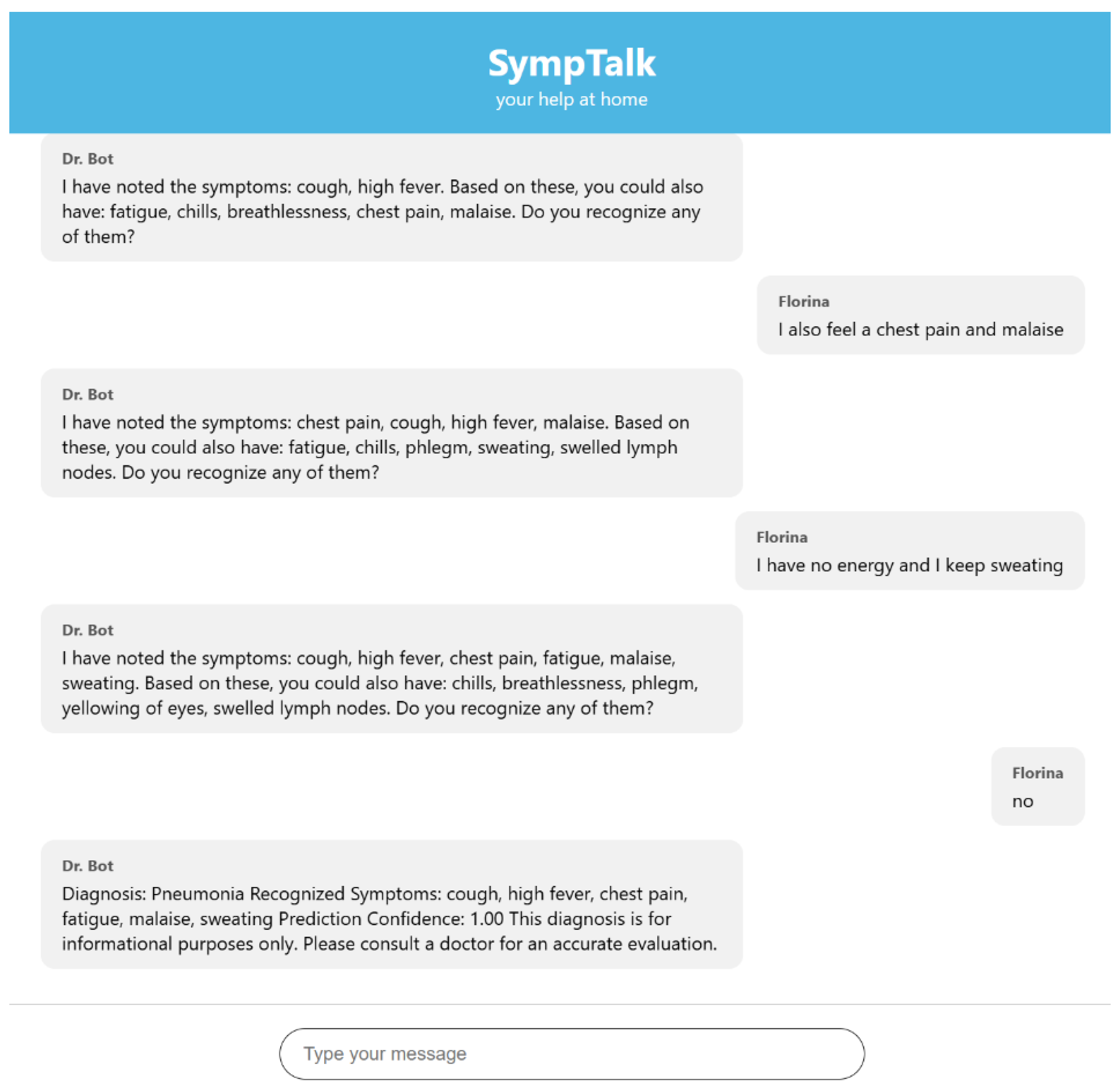

3.3. Testing the Chatbot Based Naïve Bayes Classifier

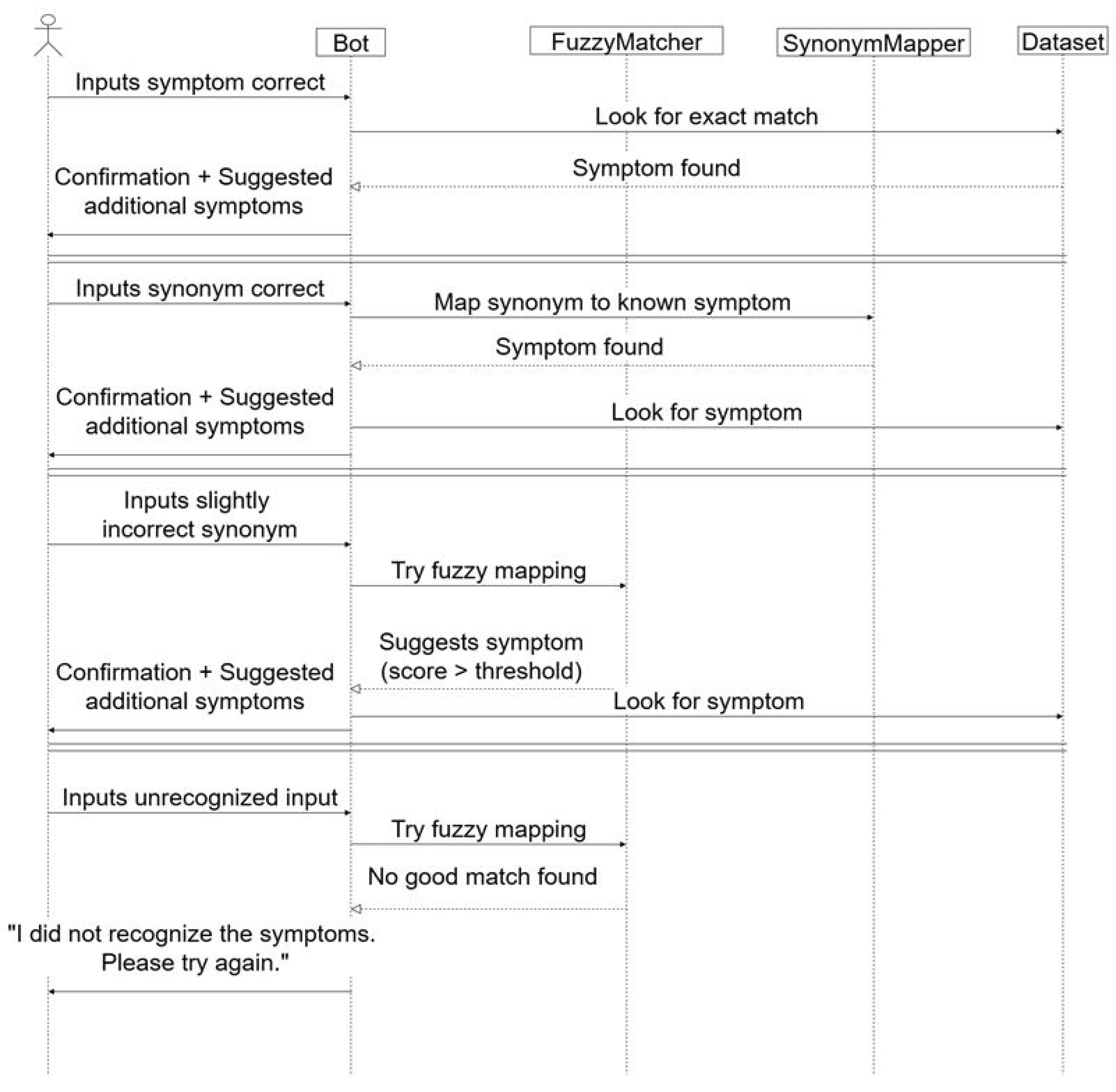

- The user sends a message in the interface

- The JavaScript in the index.html makes a POST to /webhook with the message

- Flask takes the message and sends it on to Rasa

- The race analyzes the message, executes actions

- The race sends a response (JSON) to the Flask

- Flask returns the response to the frontend

- The frontend displays it in chat as a bot message

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Developments

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almadhor, A.; Sampedro, G.A.; Abisado, M.; Abbas, S. Efficient Feature-Selection-Based Stacking Model for Stress Detection Based on Chest Electrodermal Activity. Sensors 2023, 23, 6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, A.U.; Li, J.P.; Khan, J.; Memon, M.H.; Nazir, S.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, G.A.; Ali, A. Intelligent Machine Learning Approach for Effective Recognition of Diabetes in E-Healthcare Using Clinical Data. Sensors 2020, 20, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płudowski, J.; Mulawka, J. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Support of NAFLD Diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyasin, E.I.; Ata, O.; Mohammedqasim, H.; Mohammedqasem, R. Enhancing Self-Care Prediction in Children with Impairments: A Novel Framework for Addressing Imbalance and High Dimensionality. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qtaish, A.; Albashish, D.; Braik, M.; Alshammari, M.T.; Alreshidi, A.; Alreshidi, E.J. Memory-Based Sand Cat Swarm Optimization for Feature Selection in Medical Diagnosis. Electronics 2023, 12, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F.P.; García, A.A.D.B.; Russo, L.M.S.; Ayala, J.L. SOFIA: Selection of Medical Features by Induced Alterations in Numeric Labels. Electronics 2020, 9, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, M.S.; Nag, A.; Pathan, M.M.; Dev, S. Analyzing the Impact of Feature Selection on the Accuracy of Heart Disease Prediction. Healthcare Analytics 2022, 2, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghourabi, M.; Mourad-Chehade, F.; Chkeir, A. Eye Recognition by YOLO for Inner Canthus Temperature Detection in the Elderly Using a Transfer Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilieva, G. Extension of Interval-Valued Hesitant Fermatean Fuzzy TOPSIS for Evaluating and Benchmarking of Generative AI Chatbots. Electronics 2025, 14, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, M.V. Real-Time Detection of IoT Anomalies and Intrusion Data in Smart Cities Using Multi-Agent System. Sensors 2024, 24, 7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, M.V. Multi-Agent System for Intelligent Urban Traffic Management Using Wireless Sensor Networks Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales Mendes, A.F.; Sánchez San Blas, H.; Pérez Robledo, F.; De Paz Santana, J.F.; Villarrubia González, G. A Novel Multiagent System for Cervical Motor Control Evaluation and Individualized Therapy: Integrating Gamification and Portable Solutions. Multimedia Systems 2024, 30, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez San Blas, H.; Sales Mendes, A.; de la Iglesia, D.H.; Silva, L.A.; Villarrubia González, G. A Multiagent Platform for Promoting Physical Activity and Learning through Interactive Educational Games Using the Depth Camera Recognition System. Entertainment Computing 2024, 49, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yi, H., You, M. et al. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. npj Digit. Med. 8, 159 (2025). [CrossRef]

- https://ml.cms.waikato.ac.nz/weka (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Eibe Frank, Mark A. Hall, and Ian H. Witten (2016). The WEKA Workbench. Online Appendix for “Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques”, Morgan Kaufmann, Fourth Edition, 2016.

- Kenji Kira, Larry A. Rendell: A Practical Approach to Feature Selection. In: Ninth International Workshop on Machine Learning, 249-256, 1992.

- Marko Robnik-Sikonja, Igor Kononenko: An adaptation of Relief for attribute estimation in regression. In: Fourteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, 296-304, 1997.

- https://jade.tilab.com/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Maria Muntean, Honoriu Vălean, Remus Joldeș, Emilian Ceuca, Feature selection for classifier accuracy improvement, Acta Universitatis Apulensis, No. 26/2011 pp. 203-216.

- https://legacy-docs-oss.rasa.com/docs/rasa/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- https://www.mysql.com/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Tucker, Jay (2024), “SymbiPredict”, Mendeley Data, V1. [CrossRef]

- https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv5z3v2xyd/1 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- https://flask.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Mama, Eden & Sheri, Liel & Aperstein, Yehudit & Apartsin, Alexander. (2025). From Fuzzy Speech to Medical Insight: Benchmarking LLMs on Noisy Patient Narratives. 10.48550/arXiv.2509.11803.

- Leila Aissaoui Ferhi & Manel Ben Amar & Atef Masmoudi & Fethi Choubani & Ridha Bouallegue, 2025. “Improving Symptom-Based Medical Diagnosis Using Ensemble Learning Approaches,” Systems Research and Behavioral Science, Wiley Blackwell, vol. 42(4), pages 1294-1321, July.

| Classifier | Accuracy on Initial Dataset (ID) | Accuracy on Reduced Dataset (RD) |

|---|---|---|

| J48 (Decision tree) | 95% | 93% |

| RandomForest | 95% | 98% |

| NaïveBayes | 98% | 98% |

| Dl4MlpClassifier (Deep learning) | 95% | 98% |

| Classifier | Time for Initial Dataset (ID)-seconds | Time for Reduced Dataset (RD)-seconds |

|---|---|---|

| J48 (Decision tree) | 0.71 | 0.08 |

| RandomForest | 1.13 | 0.33 |

| NaïveBayes | 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Dl4MlpClassifier (Deep learning) | 28.26 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).