The Paradox of GLP-1RA Therapy

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have rapidly changed the management of diabetes and obesity, delivering robust benefits in weight loss, glycaemic stability, and cardiovascular protection [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, accumulating evidence reveals a consistent reduction in lean body mass across clinical trials [

3]. As Ceasovschih et al. emphasize, this finding is most concerning in older adults, frail individuals, and those with multimorbidity—groups in which even small decrements in muscle reserve may accelerate functional decline [

3].

Beyond Reduced Intake and Remodeling

Proposed mechanisms include appetite suppression leading to reduced caloric and protein intake, which may diminish substrate availability for muscle maintenance. GLP-1RAs have also been linked to shifts in mitochondrial efficiency and muscle fiber composition, suggesting qualitative remodeling that could partly offset quantitative loss. In addition, enhanced autophagy and proteostasis may contribute to muscle quality improvements despite net mass reduction [

3]. While these mechanisms are plausible and supported by emerging data, they are insufficient to fully account for the reproducible lean mass decline observed across trials. This gap underscores the need to consider complementary pathways, particularly

sustained glucagon suppression, as a systemic contributor to progressive muscle reserve erosion.

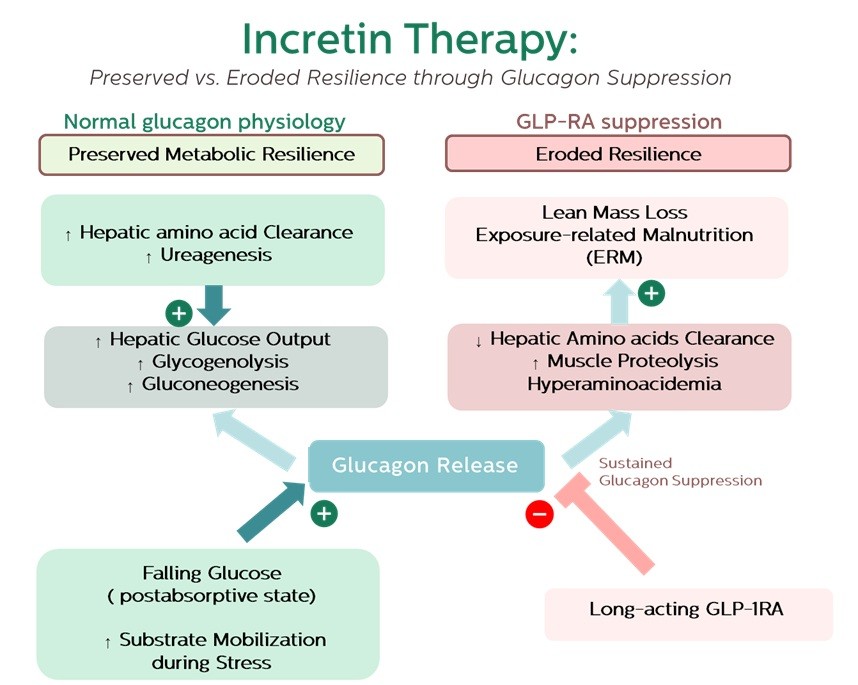

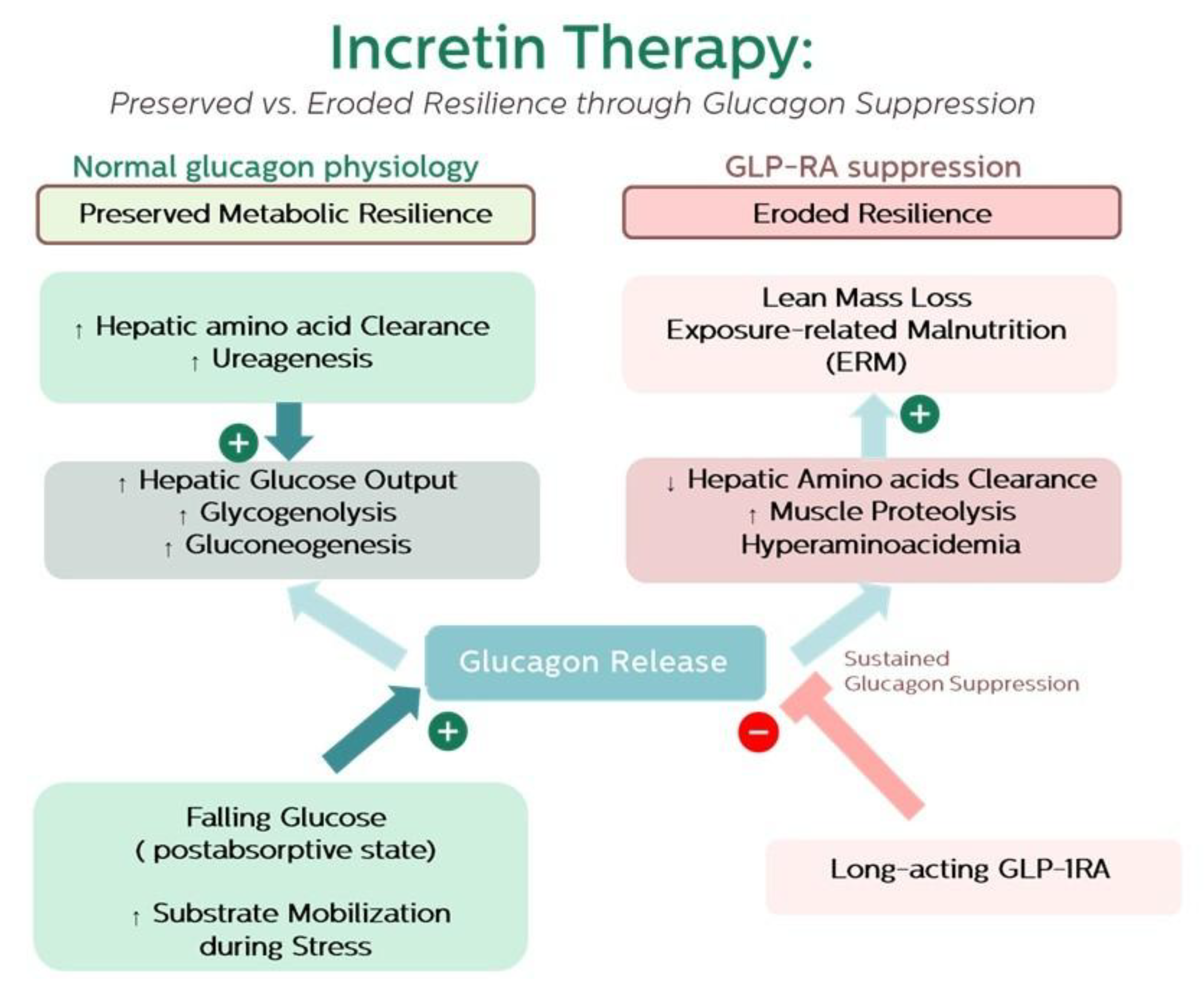

Glucagon as an Adaptive Hormone

Glucagon has long been recognized as insulin’s counter-regulator, yet its physiological role is broader: it coordinates substrate mobilisation through the liver–α-cell axis, regulates amino acid clearance, and supports stress adaptation [

4,

5,

6]. Chronic silencing of glucagon signalling, as occurs with long-acting GLP-1RAs, is therapeutically valuable in lowering hepatic glucose output [

2]. However, this persistent suppression may impair hepatic amino acid metabolism. Experimental antagonism of the glucagon receptor in humans leads to hyperaminoacidaemia, consistent with increased amino acid efflux from skeletal muscle [

7]. By analogy, chronic GLP-1RA therapy may induce a similar imbalance: when hepatic clearance is dampened, muscle proteolysis becomes the fallback substrate source.

Clinical Implications

If lean mass loss is systemic and drug-driven, mitigation requires more than nutritional counselling or resistance training. Monitoring of muscle strength, amino acid profiles, and resilience biomarkers should be considered in long-term GLP-1RA users. Older adults, frail patients, and those with multiple comorbidities may be especially vulnerable to this trade-off.

Recent evidence from the SURPASS program suggests that tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, may modulate glucagon dynamics differently from GLP-1RAs alone. In mechanistic substudies, tirzepatide produced substantial reductions in fasting and postprandial glucagon concentrations, in some cases exceeding those observed with semaglutide [

9,

10]. These findings underscore that dual agonism does not necessarily attenuate glucagon suppression; however, whether counterregulatory glucagon responses during hypoglycemia are better preserved with tirzepatide remains unresolved. Clarifying this distinction will be essential, as long-term muscle and resilience outcomes may differ across incretin-based therapies.

Recognition of drug-induced undernutrition is better reflected by biomarker patterns than by single analytes. As outlined in our ERM framework, cross-domain trade-offs—such as sustained inflammation, reduced short half-life transport proteins, and longer-term impacts on maintenance and reproductive functions—offer a more translational signal of early nutrient erosion and resilience loss [

8]. Emerging stress-responsive markers like growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15), which links mitochondrial stress to energy-conservation signaling between brain and body, may enhance sensitivity to early bioenergetic strain. Integrative panels, ideally developed through machine-learning approaches that combine metabolomics, proteins, and functional measures, hold promise for identifying high-risk individuals and guiding personalized strategies in long-term GLP-1RA users.

Given that GLP-1 RAs may induce up to 25% of fat-free mass loss, particularly in older adults and those with sarcopenic obesity, proactive muscle-preserving strategies are essential. As Ceasovschih et al. emphasize, two of the most effective non-pharmacologic measures are structured resistance or combined exercise programs and adequate protein intake, which together attenuate lean mass decline while improving functional outcomes [

3]. Practical recommendations include targeting ≥1.2–1.5 g/kg/day of high-quality protein, distributed in smaller, frequent meals to overcome GLP-1RA-related anorexia, and incorporating resistance or mixed aerobic–resistance regimens shown to mitigate fat-free mass loss in older adults. In parallel, emerging pharmacologic adjuncts such as bimagrumab and other anti-myostatin pathway antibodies are being investigated for their ability to stimulate muscle growth and may, in the future, help counterbalance lean mass reduction observed with incretin-based therapy.

Together, these insights—from differential effects across incretin classes, to biomarker-guided monitoring, to proactive interventions—highlight a need for more integrative care pathways.

Conclusion

GLP-1RA therapy epitomises the duality of modern metabolic medicine: transformative benefits paired with under-recognised risks. By highlighting the overlooked role of sustained glucagon suppression, we extend the discussion beyond weight and glucose endpoints to include long-term muscle health and adaptive capacity. Framing these effects within ERM provides a translational model for recognising early warning signs and balancing the promise of GLP-1RAs with the preservation of resilience.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- Zheng Z, Zong Y, Ma Y, Tian Y, Pang Y, Zhang C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2024;9(1):234. [CrossRef]

- Thomas MC, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. The postprandial actions of GLP-1 receptor agonists: The missing link for cardiovascular and kidney protection in type 2 diabetes. Cell metabolism. 2023;35(2):253-73. [CrossRef]

- Ceasovschih A, Asaftei A, Lupo MG, Kotlyarov S, Bartušková H, Balta A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and muscle mass effects. Pharmacological Research. 2025;220:107927. [CrossRef]

- Holst JJ, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Pedersen J, Knop FK. Glucagon and Amino Acids Are Linked in a Mutual Feedback Cycle: The Liver-α-Cell Axis. Diabetes. 2017;66(2):235-40. [CrossRef]

- Petersen MC, Vatner DF, Shulman GI. Regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism in health and disease. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2017;13(10):572-87. [CrossRef]

- Harp JB, Yancopoulos GD, Gromada J. Glucagon orchestrates stress-induced hyperglycaemia. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2016;18(7):648-53. [CrossRef]

- Elmelund E, Galsgaard KD, Johansen CD, Trammell SAJ, Bomholt AB, Winther-Sørensen M, et al. Opposing effects of chronic glucagon receptor agonism and antagonism on amino acids, hepatic gene expression, and alpha cells. iScience. 2022;25(11):105296. [CrossRef]

- Tippairote T, Hoonkaew P, Suksawang A, Tippairote P. From adaptation to exhaustion: defining exposure-related malnutrition as a bioenergetic phenotype of aging. Biogerontology. 2025;26(5):161. [CrossRef]

- Frias JP, De Block C, Brown K, Wang H, Thomas MK, Zeytinoglu M, et al. Tirzepatide Improved Markers of Islet Cell Function and Insulin Sensitivity in People With T2D (SURPASS-2). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2024;109(7):1745-53. [CrossRef]

- Heise T, Mari A, DeVries JH, Urva S, Li J, Pratt EJ, et al. Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022;10(6):418-29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).