1. Introduction

Respiratory and circulatory systems operate as interdependent physiological networks, particularly evident during spontaneous breathing where their dynamic interaction unfolds in a finely tuned manner. The synergistic relationship between these systems was first observed in 1700, when Stephen Hales [

1] documented cyclic variations in the level of blood within a glass tube inserted into a horse’s carotid artery, noting a clear association with the phases of respiration. This early observation laid the groundwork for centuries of investigation into cardio-respiratory interdependence.

Among the foundational studies, Cournand and colleagues [

2] evaluated the cardiovascular effects of intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV), both with and without continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), in healthy individuals. Their findings demonstrated a direct inverse relationship between mean airway pressure and cardiac output, highlighting that as airway pressure increased, cardiac output declined. This was linked to a drop in transmural pressure across the right ventricle and a subsequent reduction in systemic venous return.

Building on these principles, Guyton and collaborators [

3] later proposed a quantitative model for venous return, asserting that the driving force behind venous return is the pressure gradient between the mean systemic filling pressure (Pmsf) and the right atrial pressure (Pra). This theory provided a more precise framework for understanding how intrathoracic pressure variations impact venous return.

A useful conceptual model of heart-lung interaction involves considering the heart and lungs as two pumps operating in a shared anatomic compartment—the thoracic cavity. The cardiovascular system, functioning as a positive pressure pump, propels blood into the arterial system, whereas the respiratory system acts as a negative pressure pump, drawing air into the lungs and simultaneously facilitating blood return to the heart. Their shared space and vascular connections make pressure changes in the thoracic cavity during respiration pivotal in modulating cardiovascular dynamics. Before exploring how mechanical ventilation alters these relationships, it is essential to understand how spontaneous respiration influences cardiac output. This includes examining the mechanisms that control venous return to the heart and the heart’s capacity to manage that returning blood.

Right heart and determinants of preload

The Frank-Starling law of the heart provides a fundamental explanation of how the heart adapts its contractile force in response to changes in venous return. According to this principle, an increase in right ventricular (RV) preload—reflected as end-diastolic volume or wall stress—leads to greater myocardial fiber stretch, which enhances the force of ventricular contraction and subsequently increases stroke volume.

The flow of blood through the cardiovascular system is governed by pressure gradients between various anatomical compartments. A significant portion of the blood volume is housed within the venous system, which serves as a compliant reservoir. As proposed by Guyton, venous return (VR) is dictated by three core parameters: the mean systemic filling pressure (Pmsf), the right atrial pressure (Pra), and the resistance to venous return (RVP). This relationship is described by the equation:

Pmsf represents the theoretical pressure present throughout the vascular system in the absence of blood flow—essentially the “driving pressure” for venous return. The effectiveness of venous return is thus determined by the pressure differential between Pmsf and Pra. Importantly, Pmsf is influenced by the system’s total volume and the proportion of that volume considered “stressed”, i.e., exerting tension on the vessel walls. This stressed volume, along with vascular tone, plays a critical role in maintaining adequate preload and cardiac output under varying physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

The venous compartment contains approximately 70% of the body’s total blood volume, and most of this volume is held within vessels that are exposed to atmospheric pressure externally. If blood were gradually removed from a motionless circulation, one would observe a decline in mean systemic filling pressure (Pmsf) approaching zero, despite a substantial volume of blood still remaining within the vascular system. This phenomenon arises because blood that lies below the threshold required to generate vascular stretch merely occupies space within the vessels by conformationally expanding them from a collapsed to a partially open state, without exerting significant transmural pressure.

Once this unstressed volume has been exceeded, any additional intravascular volume begins to stretch the vessel walls, thereby contributing to the stressed volume, which actively increases Pmsf along the venous compliance curve. Hence, Pmsf is governed by the portion of the blood volume exerting outward pressure on the vessel walls, while the total circulating volume encompasses both stressed and unstressed components [

4]. The elastic recoil of venous vessels in response to this pressure provides the mechanical force necessary to propel blood toward the heart.

During the ventilatory cycle, right atrial pressure (Pra) fluctuates dynamically, leading to corresponding changes in venous return. Pra is influenced both by the compliance of the right atrium and by alterations in transmural pressure, which reflects the difference between intra-atrial pressure and the pressure surrounding the myocardium—typically the pleural pressure in the absence of pericardial disease [

5]. In spontaneous inspiration, contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles generates negative intrathoracic pressure (Ppl), which is transmitted to the right atrium. This enhances the pressure gradient between extrathoracic venous reservoirs and the RA, facilitating venous inflow. Simultaneously, the descent of the diaphragm increases intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), further promoting venous return by elevating Pmsf. The net effect is an augmentation of right ventricular preload, with subsequent increases in end-diastolic volume and stroke volume.

During expiration, however, intrathoracic pressure becomes less negative, leading to a rise in Pra and a modest reduction in venous return. Yet, there are physiological limits to the inspiratory enhancement of right heart filling. One such limitation is the collapsibility of the great veins, which possess thin, compliant walls. When intravascular pressure falls below the surrounding atmospheric pressure—as can occur just before entry into the thoracic cavity—further reductions in Ppl fail to enhance venous return. Additionally, the intrinsic compliance of the right heart limits the extent to which it can accommodate increased preload during inspiration.

In contrast, positive pressure ventilation (PPV) reverses the typical respiratory fluctuations in Pra: it causes an increase in RA pressure during inspiration and a decrease during expiration, modulated by changes in both intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressure [

5]. This reversal has significant clinical implications, especially in hypovolemic patients, where the pressure gradient for venous return—which normally ranges between 4–8 mmHg—can be severely compromised [

6]. Since the resistance of venous return (RVR) is very low, such a small pressure gradient is adequate to drive 100% of the cardiac output back to the heart each minute.

Despite the low resistance to venous return (RVR) under normal conditions, even small changes in positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) can induce notable reductions in preload and cardiac output. To counteract these effects, clinicians can attempt to raise Pmsf either by expanding the stressed volume (e.g., fluid administration) or by increasing venous tone (e.g., vasopressors).

Experimental studies, such as those by Katira et al. [

7] have shown that large tidal volumes combined with zero PEEP can drastically reduce Pra and RV end-diastolic volume. These conditions, compounded by elevated pulmonary vascular resistance due to lung overdistension, may lead to progressive cor pulmonale. Interestingly, applying a moderate level of PEEP (10 cmH₂O) and employing lung-protective tidal volumes effectively mitigated these adverse cardiovascular effects. [

7].

Right heart and determinants of afterload

The pulmonary vasculature is anatomically and functionally segmented into two main types of vessels: intra-alveolar and extra-alveolar. As the lungs expand during inspiration, intra-alveolar vessels—which are embedded within the alveolar walls—become compressed, resulting in a non-linear increase in their resistance. In contrast, extra-alveolar vessels, which are located within the connective tissue matrix surrounding the airways, experience a reduction in resistance due to expansion of their luminal diameter. The net effect of these opposing changes across varying lung volumes creates a U-shaped pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) curve, with its lowest point—i.e., the optimal resistance—typically occurring at functional residual capacity (FRC). Deviations from this volume in either direction result in increased PVR and, consequently, a rise in right ventricular (RV) afterload [

8].

From a West’s zone model perspective, spontaneous inspiration may transiently shift more lung regions into zone 2 physiology, where alveolar pressure (Palv) exceeds pulmonary venous pressure (Ppv), although it remains lower than pulmonary arterial pressure (Pa). This condition reduces capillary perfusion and increases RV afterload.

Given that the right ventricle acts primarily as a volume pump, rather than a pressure generator, it is especially sensitive to changes in intrathoracic pressure (ITP) and pulmonary vascular impedance. This sensitivity becomes clinically significant in pathological states such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), where hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and alveolar edema contribute to a substantial rise in RV afterload and, if sustained, can precipitate right ventricular failure.

To mitigate these adverse effects, recruitment maneuvers—which aim to reopen collapsed alveoli—can lower pulmonary vascular resistance and facilitate RV ejection. However, during positive pressure ventilation, especially when high tidal volumes are employed, overdistension of alveoli can increase PVR, thereby elevating RV afterload and impeding ejection. This effect is attenuated when lung-protective ventilation strategies—characterized by low tidal volumes and appropriate PEEP levels—are used.

Moreover, mechanical inspiration can induce more regions of the lung to shift into West’s zones 1 and 2, where alveolar pressure exceeds both arterial and venous pressures. This redistribution of pulmonary blood flow away from zone 3 (well-perfused) territories exacerbates ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch and further burdens the right ventricle.

Left heart and determinants of afterload

Afterload refers to the resistive forces the left ventricle (LV) must overcome to eject blood during systole. It is primarily governed by aortic pressure, arterial elastance, and total systemic vascular resistance. During spontaneous inspiration, the decrease in pleural pressure leads to a rise in LV transmural pressure, effectively increasing afterload and imposing a mechanical constraint on LV ejection.

In individuals with normal cardiac function, modest increases in LV afterload may have limited hemodynamic significance. However, when intrathoracic pressure drops markedly, as seen in respiratory distress, the associated rise in LV afterload, coupled with augmented venous return to the right heart, can increase intrathoracic blood volume and potentially lead to pulmonary congestion and edema.

Conversely, during positive pressure ventilation, the elevated intrathoracic pressure reduces LV transmural pressure, thereby decreasing afterload and improving cardiac output. Yet, this beneficial effect may be counterbalanced by a reduction in venous return and an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance—particularly when high PEEP or large tidal volumes are applied—ultimately impairing RV ejection.

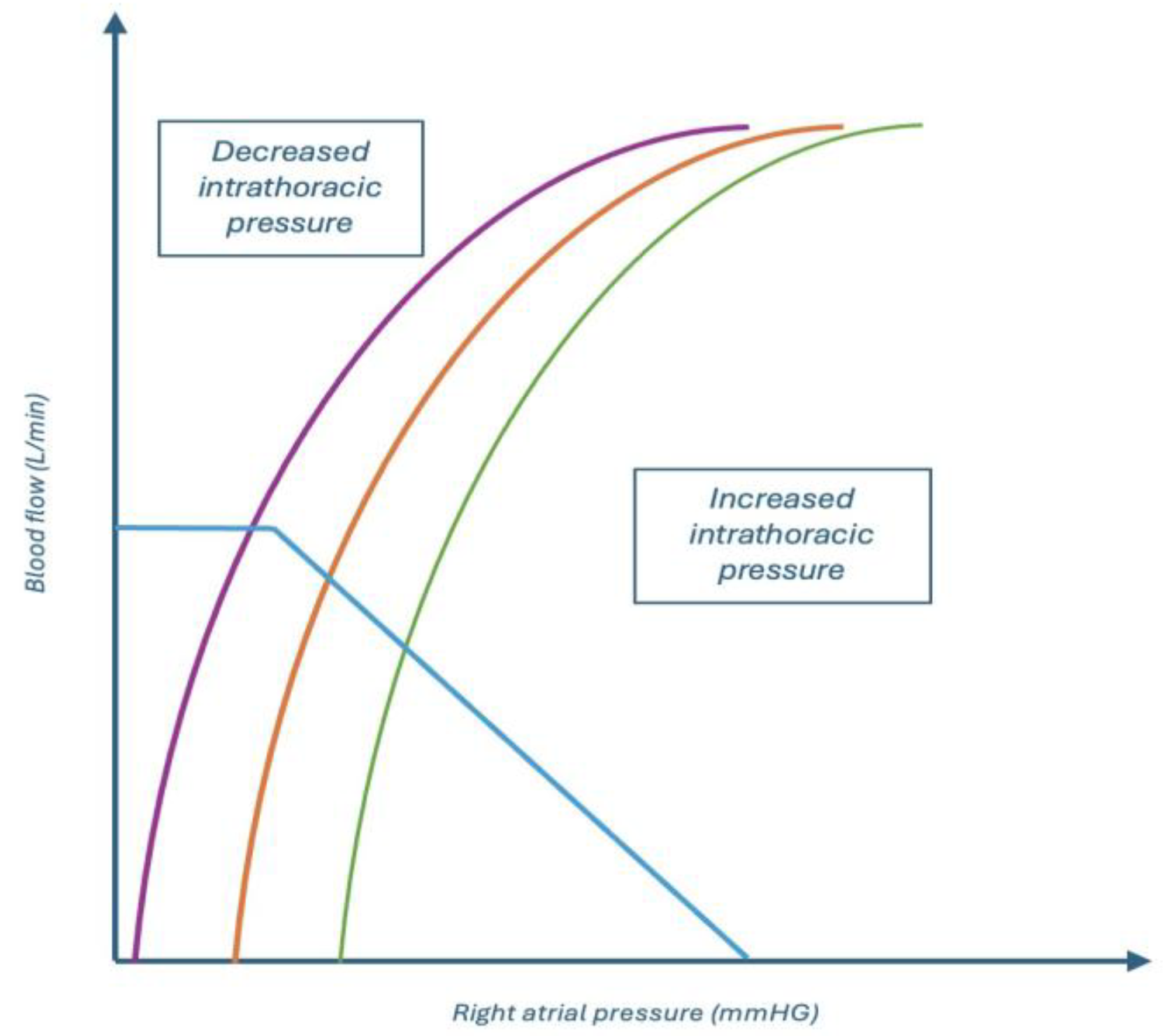

In patients with left heart failure, the use of positive pressure ventilation—especially with lung-protective parameters (low Vt, moderate PEEP)—can alleviate afterload and optimize forward flow, provided that volume loading and RV strain are adequately managed. A schematic representation of of how systemic venous return and left ventricular performance interact under varying intrathoracic pressures is shown in

Figure 1.

Left heart and determinants of preload: the concept of Ventricular interdependence

The interaction between the right and left ventricles is not limited to serial blood flow but is also mediated by their shared anatomical environment. During inspiration, increases in right ventricular preload and afterload can lead to RV dilation and enhanced stroke volume, particularly under conditions of increased venous return. However, this RV expansion occurs within the confined pericardial space and leads to mechanical displacement of the interventricular septum (IVS) toward the left side, thereby limiting LV filling—a phenomenon referred to as ventricular interdependence.

This mechanical interdependence is rooted in the heart’s architecture: the right and left ventricles are separated by the IVS, which is structurally supported by left ventricular myocardial fibers and encased within the relatively non-compliant pericardium. The LV, with its thick, helical myocardium, assumes a more spheroid geometry, whereas the RV wraps around it with a thinner, crescentic free wall. During normal respiratory efforts, RV end-diastolic volume and stroke volume may increase slightly, while LV stroke volume (LVSV) remains stable or experiences a minor decrease.

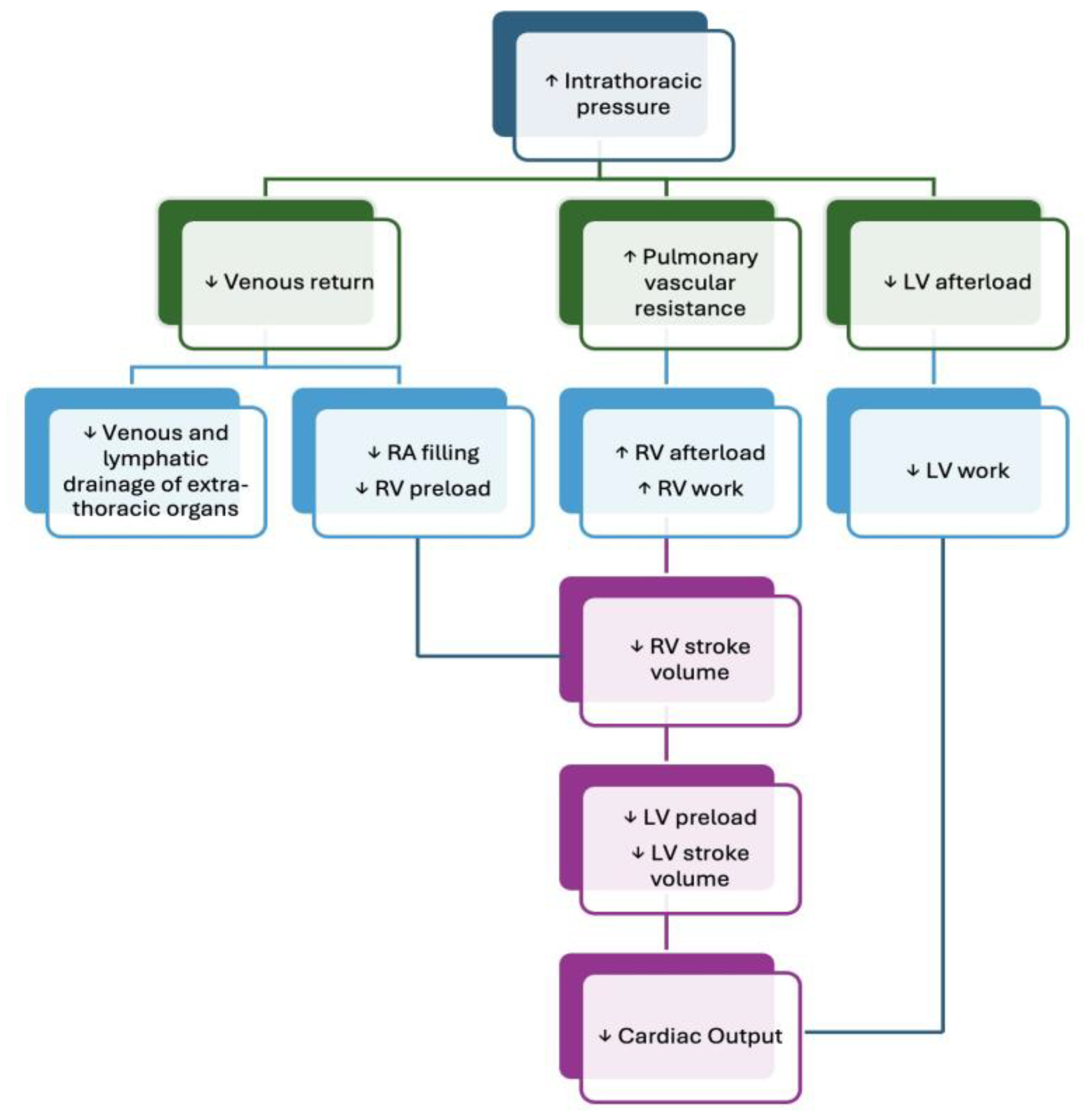

In scenarios involving deep inspiratory efforts—as in respiratory failure—the increase in RV end-diastolic volume becomes substantial enough to cause pronounced leftward septal shift, reducing LV compliance and thereby diminishing LV end-diastolic volume. Simultaneously, the increase in LV transmural pressure raises LV afterload. Together, these alterations contribute to a significant reduction in LV stroke volume, reinforcing the importance of accounting for bi-ventricular dynamics during respiratory support interventions. A summary of the effect of positive pressure ventilation on the cardiovascular system is shown in

Figure 2.

Clinical Implications in Heart-Lung Interactions

In critically ill patients, heart-lung interactions exert profound effects on hemodynamic stability, and understanding these effects is essential for appropriate clinical decision-making. Although the detailed pathophysiological mechanisms extend beyond the scope of this review, several examples illustrate their clinical relevance.

In acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dynamic hyperinflation is a hallmark feature. When intrathoracic pressures become highly negative during forceful inspiration—particularly in hypovolemic states—there may be a significant reduction in venous return due to flow limitation in the inferior vena cava and simultaneous elevation in intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). This, in turn, increases right ventricular (RV) afterload, which can ultimately compromise left ventricular (LV) filling through ventricular interdependence. Moreover, hypoxemia and hypercapnia, frequently present in these patients, may exacerbate pulmonary hypertension, further straining the RV [

9,

10]

Similar phenomena can occur in acute decompensated heart failure, where a pronounced drop in intrathoracic pressure during inspiration, accompanied by elevated IAP, may substantially increase LV afterload. In a failing left ventricle, where stroke volume is closely afterload-dependent, this may result in a marked reduction in cardiac output and exacerbate pulmonary congestion.

Conversely, positive pressure ventilation (PPV) provides cardiopulmonary benefits that extend beyond improved gas exchange. In contrast to healthy individuals, patients with acute heart failure or pulmonary edema may benefit from the hemodynamic unloading induced by PPV. Specifically, the application of non-invasive ventilation (NIV)—particularly when positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is utilized—can reduce RV preload by decreasing the venous return pressure gradient, and lower LV afterload by elevating intrathoracic pressure. These adjustments enhance ventilation-perfusion matching, recruit atelectatic alveoli, and may alleviate myocardial ischemia by improving the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption (DO₂/VO₂) [

11,

12].

In ARDS, the hemodynamic effects of PEEP are even more prominent. While recruitment of collapsed alveolar units improves oxygenation and reduces intrapulmonary shunt, lung compliance is often severely reduced, amplifying the transmission of airway pressure to intrathoracic structures. This necessitates cautious PEEP titration. The overall hemodynamic outcome of PEEP in ARDS is contingent on its recruitment-to-overdistension ratio. When PEEP contributes predominantly to alveolar recruitment, end-expiratory lung volume moves toward FRC, reducing pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and RV afterload. However, when PEEP leads to overdistension, resistance within intra-alveolar vessels increases, exacerbating PVR and impeding RV function. Both collapsed and normally aerated alveoli coexist in ARDS, making this balance delicate and highly patient-specific [

8].

Ecocardiographic Evaluation in Mechanical Ventilation

Clinicians managing mechanically ventilated patients must consider not only respiratory support but also the hemodynamic consequences of ventilator settings. Effective integration of ultrasound into bedside assessment enables early identification of cardiovascular compromise and supports timely intervention.

Since the 1980s, ultrasonography has become an indispensable tool in acute care, with portable platforms now widely available. The COVID-19 pandemic further catalyzed its routine use in emergency and intensive care environments [

13].

In this context, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) provides real-time insights into oxygen delivery (DO₂) components, guiding resuscitative efforts, evaluating fluid responsiveness, monitoring the impact of vasopressors and inotropes, and detecting signs of venous congestion or extravascular lung water accumulation [

14].

Right ventricular assessment by transthoracic ecocardiography

Right ventricular preload

As previously discussed, positive pressure ventilation profoundly affects right-sided cardiac preload, which is clinically estimated via RV end-diastolic volume or pressure—both reflective of systemic venous return [

15]

Dimension: The RV is best visualized in the apical four-chamber view, where end-diastolic dimensions are measured. RV dilatation is defined by a basal diameter >41 mm and a mid-level diameter >35 mm.

Interventricular septum (IVS): During PPV, posterior displacement of the IVS may be observed, particularly with excessive PEEP or tidal volume, leading to paradoxical septal motion during diastole. This distortion is associated with ventricular interdependence and can impair cardiac output. In parasternal short-axis view, the LV may take on a D-shaped appearance, indicative of septal flattening and leftward bowing—suggestive of increased RV afterload, potentially due to pulmonary hypertension, acute PE, or RV failure.

Inferior vena cava (IVC): Bedside assessment of the IVC remains a rapid, non-invasive proxy for central venous pressure (CVP) and right atrial pressure (RAP). Scanning is performed from a subcostal longitudinal view, 1–2 cm from the IVC-right atrial junction. A diameter <21 mm with >50% respiratory collapse is typically considered normal. However, in NIV patients, IVC assessment becomes less reliable, with conflicting findings across studies [

16]

Internal jugular vein (IJV): In mechanically ventilated patients, the IJV distensibility index is a validated surrogate for fluid responsiveness. It is calculated as:

Measurement is obtained in transverse orientation at the level of the cricoid cartilage using M-mode. A distensibility index >18% predicts a ≥15% increase in cardiac index, showing high sensitivity and specificity.

Venous excess ultrasound (VExUS): This tool aids in detecting volume overload, utilizing pulse-wave Doppler to assess flow patterns in the hepatic, portal, and intrarenal veins. Normally, hepatic vein flow is pulsatile, while portal and intrarenal veins exhibit continuous flow patterns. As RAP increases, these flow profiles become altered due to transmitted pressure changes [

17].

Right ventricular contractility

The contractile performance of the right ventricle (RV) is a critical determinant of global cardiac output, particularly in conditions of increased afterload or compromised pulmonary hemodynamics. Unlike the left ventricle, RV contraction occurs predominantly along the longitudinal axis, rather than radially.

Two widely adopted echocardiographic parameters are used to assess RV systolic function [

18,

19]:

Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE): Measured in the apical four-chamber view using M-mode, TAPSE reflects the longitudinal shortening of the RV free wall. A value <17 mm is generally considered indicative of RV systolic dysfunction.

Peak Systolic Velocity of the Lateral Tricuspid Annulus (S’ wave): This metric is obtained via tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) at the lateral tricuspid annulus in the apical four-chamber view. An S’ velocity <10 cm/s strongly correlates with impaired RV systolic performance.

Right ventricular afterload

RV afterload refers to the pressure the right ventricle must overcome during systolic ejection into the pulmonary circulation. It is primarily influenced by pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and pulmonary artery pressure (PAP).

Tricuspid Regurgitant (TR) Jet Velocity: This parameter serves as a non-invasive estimate of PAP. Utilizing continuous wave Doppler (CW) across the regurgitant jet, a peak TR velocity >2.8 m/s suggests elevated pulmonary pressures and may indicate pulmonary hypertension [

18,

19].

Left ventricular assessment by transthoracic ecocardiography

Left ventricular preload

LV preload is determined by multiple factors, including venous return, pericardial pressure, and ventricular compliance. In clinical practice, lung ultrasound (LUS) offers an adjunctive method to detect pulmonary congestion. The presence of B-lines occupying more than 50% of the pleural line in multiple intercostal spaces, without spared areas, is highly suggestive of cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Left ventricular contractility

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) remains the cornerstone parameter for evaluating LV systolic function. It represents the percentage of end-diastolic volume (EDV) ejected during systole and is calculated using:

Where SV is the stroke volume and ESV is end-systolic volume.

Multiple echocardiographic modalities are employed to assess LVEF:

An EPSS >10 mm is associated with reduced LVEF. [18,19]

Simpson’s Biplane Method: Recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography, this technique involves tracing the endocardial borders of the LV in both apical four- and two-chamber views, at end-diastole and end-systole. The ventricle is subdivided into disks, and their volumes are summed to determine EDV and ESV. Accurate tracing must include papillary muscles, and ECG gating is critical to identify the R wave (end-diastole) and T wave (end-systole) [

19]

According to the American College of Cardiology, LVEF stratifies heart failure as follows:

- ○

HFpEF (preserved EF): ≥50%

- ○

HFrEF (reduced EF): ≤40%

- ○

HFmrEF (mildly reduced): 41–49%

- ○

HFimpEF (improved EF): ≥40% with prior EF ≤40% [

20]

Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (MAPSE): A valuable indicator of LV function, especially in suboptimal imaging conditions, MAPSE is measured using M-mode in the apical four-chamber view. Values <8 mm suggest significant systolic dysfunction, with a normal reference range around 12 ± 2 mm. [19] LV Outflow Tract Velocity-Time Integral (LVOT-VTI): In hemodynamically unstable patients, LVEF may not accurately reflect stroke volume (SV), especially under hyperdynamic states. SV is calculated using:

The LVOT diameter is measured in the parasternal long-axis (PLAX) view, and VTI is acquired using pulse-wave Doppler in the apical five-chamber view. A VTI between 17–23 cm is considered normal. A low VTI associated with hypotension and elevated lactate suggests low-output shock, while a high VTI with similar clinical features may point to distributive shock [

15]. This parameter is especially helpful in assessing fluid responsiveness in patients on NIV.

Heart lung interactions during Non invasive ventilation: tricks and pitfalls

Non invasive ventilation (NIV) actually is the mainstay treatment for patients with acute or chronic respiratory failure that do not require an artificial airway. NIV improves respiratory function through several mechanisms. Primarily, it decreases the effort required for breathing by employing supra-atmospheric pressure intermittently to the airways, which elevates transpulmonary pressure, expands the lungs, increases tidal volume and alleviates strain on the inspiratory muscles, increases functional residual capacity, which helps with alveolar recruitment, decreases shunt and improves V/Q matching. These effects improve oxygenation and potentially alleviate dyspnoea by shifting the respiratory system to a more compliant region of the pressure–volume curve. NIV can improves encephalopathy due to hypercapnia, avoid continuous sedation often required during invasive mechanical ventilation and furthermore it can improves cardiac output by reducing afterload through a decreased transmyocardial pressure. This effect of MV is particularly dependent upon the type and severity of cardiac dysfunction. When ventricular dysfunction is preload-dependent (e.g. hypovolaemia, ischaemia, restrictive cardiomyopathy, tamponade, and valvular stenoses), MV will generally cause a further reduction in cardiac output. General measures to prevent hypotension include the use of MV parameters that minimise mean airway pressure together with volume loading and, when necessary, the use of vasoconstrictor agents. When left ventricular dysfunction is afterload-dependent, MV may improve cardiac output. In subjects with afterload-induced RV dysfunction (e.g. severe pulmonary hypertension, acute PE, COPD, or RV infarct) MV may also adversely effect the balance of RV oxygen supply and demand. The treatment of reversible pulmonary vasoconstriction (e.g. from hypoxia or acidosis) and defence of coronary perfusion pressure with pressor agents may be beneficial [

21]

NIV is so indicated in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD and asthma characterised by acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, increased work of breathing and no impaired consciousness but also in chronic COPD and pulmonary rehabilitation, in patients affected by OSAS, acute heart failure, COVID-19 and in post-exubation period above all in elderly, hypercapnia and elevated APACHE II score.

NIV can be delivered through different modes as CPAP, BIPAP and volume-assured support mode and different interfaces as a facial mask, full- face mask, an helmet interface that use a soft transparent polyvinyl hood with a seal created by a rigid padded collar around the patient’s neck secured usually via armpit braces.

While not traditionally grouped into NIV, high nasal flow devices generate a high degree of humidified airflow and oxygen delivery, decreasing anatomical dead space, reducing carbon dioxide rebreathing and providing a small PEEP effect, leading to a decrease in work of breathing. As such, high nasal flow is a highly effective form of non-invasive respiratory support [

22]

NIV tolerance has been associated with NIV synchrony and success. Synchrony is the match between the patient’s neural inspiratory and expiratory times and the ventilator’s mechanical inspiratory and expiratory times; patient- ventilator asynchrony could be cause worsened gas exchange, wasted respiratory efforts and increased discomfort, and will incur increased need for secondary respiratory complications leading to sedation and invasive mechanical ventilation. The presence of interfaces leaks, no humidified devices, sleep deprivation, fever, sense of

claustrophobia, underlying lung and heart disease can create significant triggering delays or missed triggers, flow delivery mismatches with effort, and cycling asynchronies (both premature and delayed). All of these can produce considerable patient discomfort leading to dyspnea, anxiety and subsequently stress-related catechol release with increases in myocardial oxygen demands and risk of dysrhythmias. In addition, coronary blood vessel oxygen delivery can be compromised by inadequate gas exchange from the lung injury coupled with low mixed venous PO2 due to high oxygen consumption demands by the inspiratory muscles [

23]; so patient- ventilator asynchronies may reverse the beneficial effects of positive pressure ventilation on heart discuss above. In this contest ecocardiography plays a primary role in the evaluation and assessment heart-lung interaction before and after NIV prescription. In addition to anamnesis, physical examination and laboratoristic exams, know if patient is a ’fluid responsive’ or ’fluid unresponsive’ above all in patients with ventricular dysfunction preload- dependent, the RV and LV initial assessment in terms of preload and afterload and how it changes during non-invasive ventilation. Considering The amount of data we can obtain with echocardiography, future research should aim to standardize echocardiographic protocols specifically tailored to patients on non-invasive ventilation (NIV), according to their comorbidities and (patho)physiology.

Left Ventricular Diastolic Function and Weaning-Induced Pulmonary Edema (WIPO)

Mechanical ventilation typically alters diastolic filling of the left ventricle. During the weaning phase, the transition from positive to negative pressure ventilation can provoke WIPO through various mechanisms. In patients with chronic RV dysfunction, the sudden increase in RV preload during spontaneous breathing may lead to RV dilation, IVS deviation, and compromised LV filling—a manifestation of ventricular interdependence. In those with chronic LV dysfunction, the abrupt increase in LV afterload (due to exaggerated intrathoracic negativity, elevated IAP, and sympathetic surge-induced hypertension) can overwhelm a failing LV, precipitating pulmonary edema. Furthermore, a positive fluid balance and volume overload are contributing factors to WIPO. The presence of chest drains and their associated resistive impedance to inspiratory flow may exacerbate the phenomenon by amplifying pleural pressure swings during early spontaneous efforts [

8].

5. Conclusions

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Understanding the intricate interplay between the respiratory and cardiovascular systems is essential for the optimal management of critically ill patients, particularly those receiving non-invasive ventilatory support. The physiological consequences of positive pressure ventilation extend well beyond the pulmonary system, profoundly influencing preload, afterload, ventricular interdependence, and ultimately, cardiac output.

This review has highlighted the dynamic effects of spontaneous versus mechanical ventilation on heart-lung interactions, emphasizing how respiratory mechanics modulate right and left ventricular function. Special attention has been given to the hemodynamic impact of PEEP, the pathophysiological implications in ARDS and heart failure, and the clinical significance of echocardiographic assessment as a bedside tool for guiding fluid management, evaluating contractility, and identifying early signs of decompensation.

Proper interpretation of these interactions enables clinicians to make evidence-based decisions, personalize ventilatory strategies, and minimize cardiovascular compromise, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiac dysfunction or altered pulmonary vascular dynamics.

Future research should aim to:

Standardize echocardiographic protocols specifically tailored to patients on non-invasive ventilation (NIV), incorporating parameters that reliably reflect dynamic heart-lung interactions.

Explore the use of real-time ultrasound-guided algorithms for PEEP titration based on RV function, IVC dynamics, or venous congestion markers.

Investigate the prognostic value of combined cardiac and lung ultrasound in the context of weaning-induced pulmonary edema (WIPO) and difficult ventilator liberation.

Evaluate the impact of individualized PEEP on RV afterload and ventricular interdependence in different phenotypes of acute and chronic cardiopulmonary disease.

Integrate advanced hemodynamic monitoring tools (e.g., VExUS, LVOT-VTI trends, S’ wave velocities) into protocolized ventilatory support algorithms to improve patient outcomes.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach combining respiratory physiology, echocardiography, and hemodynamic monitoring will be essential to refine personalized ventilatory strategies in the ICU.

Author Contributions

RC: RS, EDR Writing – Original Draft Preparation: RC, RS Writing – Review and Editing: RC,RS, IM, AA, EDR – Supervision: EDR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable due the type of paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Noh SA, Kim HS, Kang SH, Yoon CH, Youn TJ, Chae IH. History and evolution of blood pressure measurement. Clin Hypertens. 2024 Apr 1;30(1):9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cournand A, Motley HL. Physiological studies of the effects of intermittent positive pressure breathing on cardiac output in man. Am J Physiol. 1948 Jan 1;152(1):162-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyton Ac, Lindsey Aw, Abernathy B, Richardson T. Venous return at various right atrial pressures and the normal venous return curve. Am J Physiol. 1957 Jun;189(3):609-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinsky MR, Teboul JL, Vincent JL, editors. Hemodynamic Monitoring. Cham: Springer; 2019.

- Mahmood SS, Pinsky MR. Heart-lung interactions during mechanical ventilation: the basics. Ann Transl Med. 2018 Sep;6(18):349. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buda AJ, Pinsky MR, Ingels NB Jr, Daughters GT 2nd, Stinson EB, Alderman EL. Effect of intrathoracic pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med. 1979 Aug 30;301(9):453-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katira BH, Giesinger RE, Engelberts D, Zabini D, Kornecki A, Otulakowski G, Yoshida T, Kuebler WM, McNamara PJ, Connelly KA, Kavanagh BP. Adverse Heart-Lung Interactions in Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Dec 1;196(11):1411-1421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak M, Teboul JL. Heart-Lungs interactions: the basics and clinical implications. Ann Intensive Care. 2024 Aug 12;14(1):122. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Human pulmonary vascular responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia.

- Gomez H, Pinsky MR. Effect of mechanical ventilation on heart–lung interactions. In: Tobin MJ, editor. Principles and Practice of Mechanical Ventilation. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2013. p.821-850.

- Bersten AD, Holt AW, Vedig AE, Skowronski GA, Baggoley CJ. Treatment of severe cardiogenic pulmonary edema with continuous positive airway pressure delivered by face mask. N Engl J Med. 1991 Dec 26;325(26):1825-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbenetz N, Wang Y, Brown J, Godfrey C, Ahmad M, Vital FM, Lambiase P, Banerjee A, Bakhai A, Chong M. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Apr 5;4(4):CD005351. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dandel, M. Heart-lung interactions in COVID-19: prognostic impact and usefulness of bedside echocardiography for monitoring of the right ventricle involvement. Heart Fail Rev. 2022 Jul;27(4):1325-1339. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delle Femine FC, D’Arienzo D, Liccardo B, Pastore MC, Ilardi F, Mandoli GE, Sperlongano S, Malagoli A, Lisi M, Benfari G, Russo V, Cameli M, D’Andrea A; Working Group in Echocardiography of the Italian Society of Cardiology. Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know. J Clin Med. 2024 Dec 27;14(1):77. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noor A, Liu M, Jarman A, Yamanaka T, Kaul M. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Use in Hemodynamic Assessment. Biomedicines. 2025 Jun 10;13(6):1426. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Si, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Cao, D.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Guan, X. Does Respiratory Variation in Inferior Vena Cava Diameter Predict Fluid Responsiveness in Mechanically Ventilated Patients? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.Anesthesia Analg. 2018, 127, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assavapokee T, Rola P, Assavapokee N, Koratala A. Decoding VExUS: a practical guide for excelling in point-of-care ultrasound assessment of venous congestion. Ultrasound J. 2024 Nov 19;16(1):48. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Otto, CM. Textbook of clinical echocardiography. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2023. Antonini-Canterin F, Carerj S, Colonna P, Giorgi M. Manuale di ecocardiografia transtoracica. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore; 2019.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al.; ACC/AHA Joint Committee Members. 2022.

- AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895–e1032. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Duke Cardiovascular effects of mechanical ventilation Critical Care and Resuscitation 1999; 1: 388-399.

- Criner GJ, Gayen S, Zantah M, et al. Clinical review of non-invasive ventilation. Eur Respir J 2024; 64: 2400396. [CrossRef]

- Neil R MacIntyre Physiologic Effects of Noninvasive Ventilation Respiratory Care, Volume 64, Number 6, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).