1. Introduction

In modern industrial systems, maintenance maturity is crucial for operational efficiency, asset longevity, and cost-effectiveness [

1]. Over the years, maintenance strategies have evolved from reactive to predictive and condition-based approaches, yet increasing complexity demands adaptability to uncertainties and sustainability requirements [

2]. A mature maintenance system enhances reliability, minimizes downtime, optimizes resources, and ensures regulatory compliance while aligning with sustainability goals such as energy efficiency and waste reduction [

3].

Recently, technological advancements, including IoT and AI-driven analytics, require rethinking traditional maintenance models [

4]. Additionally, interdependencies between production, logistics, and maintenance introduce cascading risks, while aging infrastructure and workforce shortages necessitate smarter strategies balancing efficiency, cost, and sustainability. Regulatory pressures further demand continuous adaptation [

5]. However, traditional maintenance maturity models rely on rigid, deterministic assessments that fail to capture real-world uncertainties, such as unexpected failures and supply chain disruptions [

6,

7].

Resilience in maintenance ensures sustained performance under uncertainties by anticipating, monitoring, responding to, and learning from disruptions [

6,

8]. Modern industrial systems operate in highly dynamic environments where unexpected failures, fluctuating demand, supply chain disturbances, and regulatory shifts pose constant challenges. A resilient maintenance approach enables organizations to withstand such disruptions, adapt, and recover quickly, minimizing downtime and preserving operational continuity [

8]. As a result, this approach extends beyond reliability-centered maintenance, incorporating predictive strategies, real-time monitoring, and rapid response mechanisms. Learning from past failures further strengthens system resilience [

9,

10,

11,

12].

While resilience addresses the ability to cope with disruptions, sustainable maintenance emphasizes integrating maintenance strategies with environmental, economic, and social responsibility to ensure long-term viability [

13,

14]. Sustainable maintenance practices aim to reduce energy consumption, optimize resource utilization, minimize waste generation, and lower greenhouse gas emissions while maintaining high system reliability. By prioritizing sustainability, organizations can enhance the efficiency and longevity of industrial assets and contribute to corporate social responsibility (CSR) objectives and compliance with environmental regulations [

13,

15,

16,

17].

The synergy between resilience and sustainability in maintenance is becoming increasingly important in industrial systems [

18]. A resilient system that lacks sustainability may recover from disruptions but at a high economic or environmental cost. Conversely, a purely sustainable system without resilience may struggle to maintain operational continuity under uncertain conditions. Integrating these two concepts allows organizations to develop adaptive, long-term maintenance strategies that balance economic efficiency, environmental responsibility, and operational stability [

15,

19].

Recent studies highlight the growing importance of resilience and sustainability in maintenance management. Research indicates that maintenance strategies incorporating both aspects can significantly reduce downtime, improve asset longevity, and enhance overall system efficiency while minimizing environmental impact. Moreover, advances in digital twin technology, AI-driven predictive analytics, and cyber-physical systems have enabled organizations to develop more adaptive and resource-efficient maintenance strategies [

18,

19]. Despite these advancements, the conceptual integration of resilience and sustainability into maintenance maturity modeling remains limited. Established models often focus on traditional metrics (cost, reliability) and fail to provide a strategic roadmap for modern challenges, neglecting the critical role of maintenance in achieving organizational resilience and environmental responsibility. There is a clear gap in frameworks that holistically address the strategic development of maintenance capabilities in dynamic environments [

20].

Maintenance maturity refers to the progressive development of maintenance strategies, transitioning from reactive to optimized practices [

3]. Established models such as PAS 55, ISO 55000, and RCM focus on reliability and cost-efficiency but often neglect broader industrial dynamics [

21]. Most models are deterministic, relying on rigid scoring schemes (e.g., checklist or binary assessments) that fail to capture modern challenges such as adaptability and proactive capabilities [

22,

23,

24]. This inherent rigidity is a major practical shortcoming, as it cannot accurately assess the nuanced, subjective, and data-scarce conditions prevalent in many real-world industrial settings. Due to the above limitations, there is a growing need for a more comprehensive, multidimensional approach that incorporates both resilience and sustainability as key elements of maintenance maturity. This approach would better assess systems’ ability to adapt to uncertainty and align with long-term environmental, social, and economic goals.

In addition, most existing maintenance maturity models do not directly address the inherent uncertainty in modern industrial systems. These models also lack sufficient flexibility to effectively deal with unexpected failures, supply chain disruptions, or changing regulations. Moreover, current models rarely articulate how maturity assessment can support strategic foresight, long-term planning, and cross-sectoral adaptability. Therefore, there is a need to develop new frameworks that assess an organization’s ability to maintain operational continuity under uncertainty while integrating resilience and sustainability into the process. In this context, maintenance maturity assessment is a diagnostic tool and a foundation for developing intelligent, future-ready maintenance strategies.

Following this, the article presents the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) - a multidimensional framework that incorporates five key maturity potentials: reliability, safety, resilience, flexibility, and environmental impact. The IMMM’s fundamental advantage is that it shifts the paradigm from deterministic diagnosis to flexible, prescriptive assessment. Using a fuzzy logic-based inference system, IMMM enables nuanced assessment under uncertain conditions by effectively transforming qualitative expert knowledge into a precise, quantitative score. This overcomes the practical barrier faced by data-hungry models and provides a more accurate reflection of maintenance performance.

Following this, in this study, maintenance maturity is defined as the extent to which an organization’s maintenance system is systematically structured, managed, and continuously improved to ensure the reliability, safety, resilience, and sustainability of assets under uncertain conditions. It reflects not only the technical performance of maintenance (e.g., availability, cost efficiency, failure rates) but also its organizational and strategic capability to anticipate disruptions, adapt to change, and recover effectively.

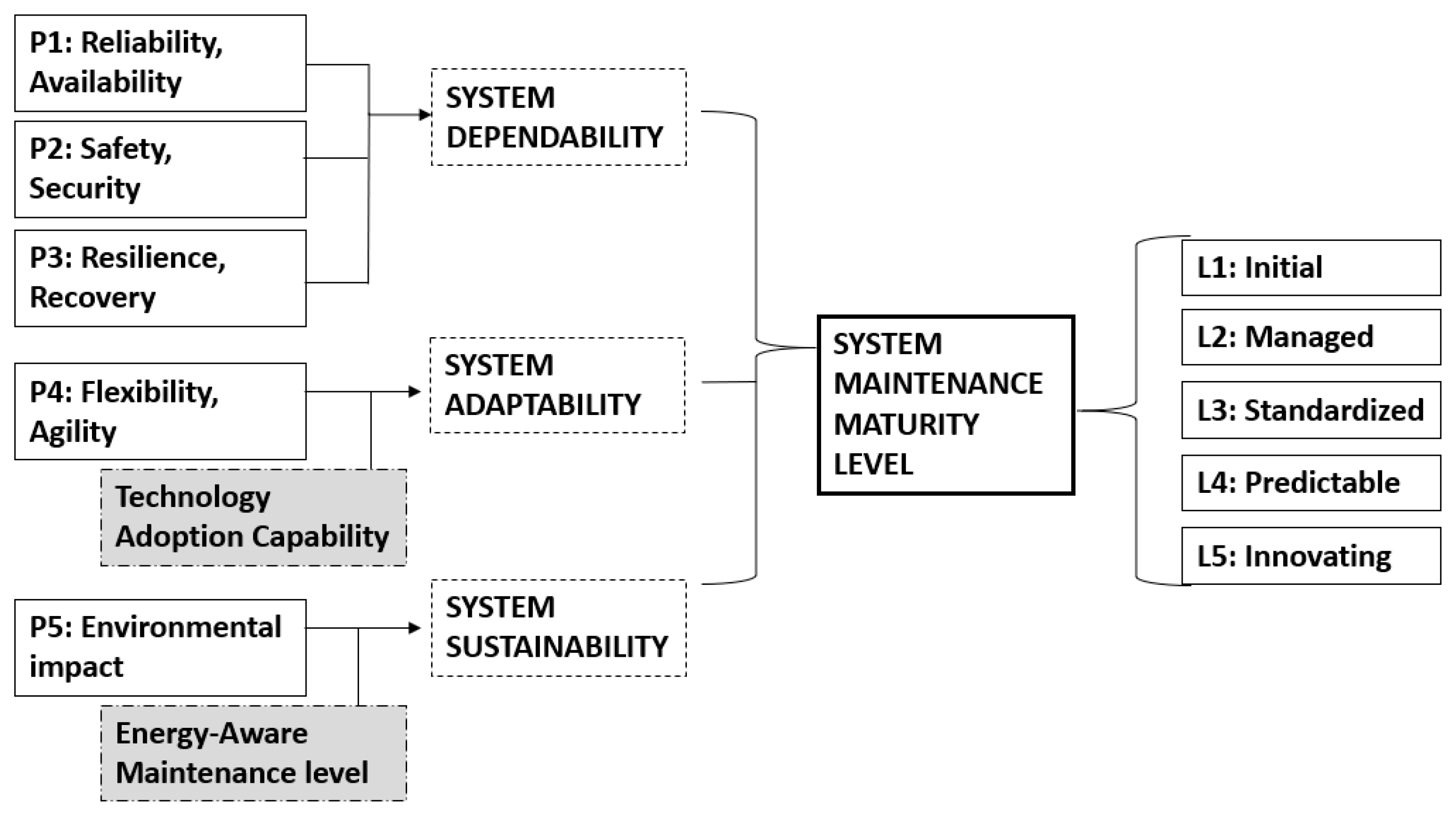

Therefore, maintenance maturity represents a long-term capability perspective, distinguishing it from short-term performance metrics. Within the proposed Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM), this maturity is operationalized through five interrelated potentials, i.e., Reliability and Availability (P1), Safety and Security (P2), Resilience and Recovery (P3), Flexibility and Agility (P4), and Sustainability (P5), and evaluated along three overarching system dimensions: Dependability, Adaptability, and Sustainability.

This work is a continuation of the authors’ previous study [

25], in which the conceptual foundations and applicability possibilities of the IMMM approach were introduced. Building on that foundation, the present article focuses on the practical methodology for maturity assessment using a fuzzy logic-based tool, enabling its implementation in real industrial contexts. Crucially, the IMMM is designed not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a prescriptive decision-support system, providing management with a clear path to prioritize and predict the impact of specific maturity-enhancing actions. In addition, the proposed approach introduces two additional parameters for system maturity dimensions assessment, namely: Technological adaptability and Resource efficiency.

Although the fuzzy inference method applied in this study follows the classical Mamdani framework, its novelty lies in the integration of fuzzy logic within the multidimensional maintenance maturity model. The proposed IMMM extends beyond traditional fuzzy maintenance applications by:

- (i)

embedding fuzzy reasoning into a hierarchical, multi-potential maturity structure that jointly evaluates dependability, adaptability, and sustainability, integrating strategic dimensions (P3: Resilience and P5: Sustainability) often neglected by established frameworks (e.g., M-SCOR, M3);

- (ii)

introducing two new fuzzy input parameters -Technology Adoption Capability and Energy-Aware Maintenance Level, to reflect the digitalization and sustainability dimensions of modern maintenance; and

- (iii)

linking fuzzy outputs directly to strategic decision-support insights that identify maturity gaps and prioritize resilience-enhancing actions, a capability absent in purely diagnostic, deterministic models.

This methodological integration makes the fuzzy approach not only diagnostic but also prescriptive, providing practical guidance for continuous improvement under uncertainty.

Unlike traditional maturity assessment approaches, the proposed Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) introduces a multidimensional structure supported by fuzzy inference logic. The model not only integrates dependability, adaptability, and sustainability dimensions but also incorporates two additional assessment factors, technology adoption capability and energy-aware maintenance level, allowing the evaluation of maintenance maturity under uncertainty. This combination of multidimensional modeling and fuzzy-based inference provides a new, practical way to identify maturity gaps and prioritize strategic improvements that is demonstrably superior in its robustness under uncertainty and its holistic scope. Indeed, the objectives of this study are to: (1) define a hierarchical maturity framework integrating resilience and sustainability; (2) identify input parameters based on key knowledge areas; (3) develop a fuzzy inference system for evaluation under uncertainty; and (4) validate the model through an industrial case study.

Therefore, the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations of maintenance maturity modeling and highlights the research gap.

Section 3 introduces the conceptual framework of the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) and defines the main maturity potentials.

Section 4 presents the fuzzy logic–based methodology used for qualitative and quantitative assessment.

Section 5 describes a case study that validates the model in an industrial context.

Section 6 discusses the results and implications for maintenance management, while Section 7 concludes with future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background

In this section, the authors comprehensively review existing studies on maintenance maturity models, resilience in maintenance, sustainable maintenance, and fuzzy logic applications in maintenance management. The review highlights research gaps and justifies the need for an Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) incorporating resilience and sustainability principles.

2.1. One-Dimensional Maintenance Maturity Models

Maintenance Maturity Models (MMMs) are frameworks used to assess and measure the progression of maintenance strategies within organizations, helping them evolve from basic reactive practices to more advanced, optimized methods [

3]. These models typically define various maturity levels and provide a structured approach for organizations to improve their maintenance capabilities over time. Several prominent MMMs exist, each with a specific focus and set of criteria. Standards like PAS 55 (now integrated into ISO 55000) provide a comprehensive framework for asset management, with maintenance maturity being a crucial component. These standards emphasize the strategic alignment of maintenance activities with broader organizational objectives, ensuring the long-term health and sustainability of assets [

21]. Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) Maturity Models offer another perspective, evaluating maintenance effectiveness through the lens of system reliability and risk management. These models guide organizations in developing proactive maintenance strategies based on understanding asset functions and the consequences of their failure, prioritizing maintenance efforts according to asset criticality [

26]. Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) Maturity Models take a different approach, focusing on maximizing equipment effectiveness by engaging all employees in proactive maintenance practices. TPM emphasizes principles like autonomous maintenance, planned maintenance, and the elimination of major losses to foster a culture of continuous improvement across the entire organization [

27].

The known traditional maintenance maturity models focus on operational excellence, emphasizing reliability, cost efficiency, and process optimization. However, they fail to address resilience and sustainability, limiting their ability to support maintenance in dynamic environments. Their rigid, deterministic assessments overlook uncertainty, adaptability, and long-term environmental impact. Such a conclusion can be supported by literature, e.g., [

28], where recent developments in this area are summarized. As a result, to bridge this gap, a new multidimensional approach is needed, integrating resilience, sustainability, and fuzzy logic to ensure adaptive, proactive maintenance strategies that align with operational continuity and modern industrial challenges.

2.2. Two-Dimensional Maintenance Perspective

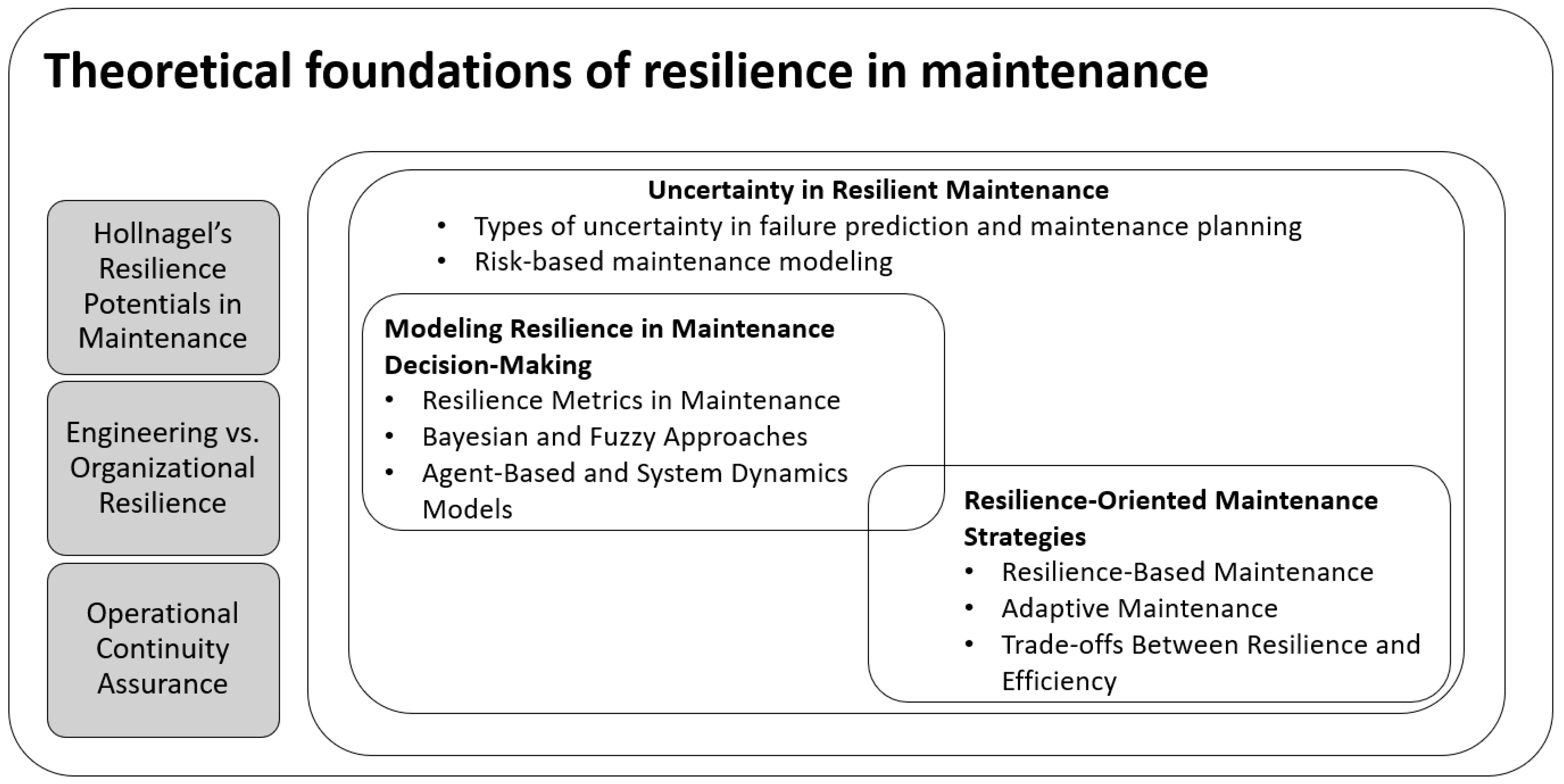

Ensuring operational continuity in industrial systems requires a maintenance approach that integrates resilience, sustainability, and strategies for managing uncertainty. Traditional maintenance maturity models primarily emphasize reliability and cost efficiency but fail to address these dimensions comprehensively. This section explores the role of resilience, sustainability, and uncertainty in maintenance and highlights gaps in relation to maturity modeling. Within this perspective, we can distinguish several key approaches that incorporate resilience and sustainability, addressing both adaptability to disruptions and long-term environmental, economic, and social impacts. These approaches have been summarized in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Resilience in maintenance extends beyond traditional reliability-focused approaches by incorporating adaptability, failure recovery, and system robustness. Existing frameworks primarily emphasize reliability, efficiency, and cost reduction, yet they often neglect the dynamic nature of industrial environments and the increasing uncertainty affecting maintenance decision-making. Theoretical foundations, such as Hollnagel’s resilience potentials - Respond, Monitor, Anticipate, and Learn - offer a structured way to integrate resilience into maintenance strategies, ensuring operational continuity and adapting to unforeseen disruptions [

29,

30].

Despite efforts to develop resilience-oriented maintenance strategies, the field still struggles to balance cost efficiency and system adaptability [

6]. While resilience-based maintenance expands beyond reliability-centered approaches by emphasizing system recovery and flexibility, challenges remain in implementing adaptive maintenance strategies that adjust dynamically based on evolving system conditions [

31,

32]. Maturity models for maintenance assessment have also been slow to integrate resilience factors, as most frameworks focus on linear, deterministic progressions that fail to capture the complexity of modern industrial systems. Recent research explores fuzzy-based models to address this gap, allowing for more nuanced evaluations of resilience maturity. However, existing models still lack comprehensive methodologies for quantifying resilience in a structured manner [

33,

34,

35].

Uncertainty in resilient maintenance poses another major challenge. Aleatory uncertainty, driven by random failures and variable operating conditions, and epistemic uncertainty, stemming from incomplete predictive models and diagnostic data, complicate decision-making. Current risk-based maintenance models do not fully account for resilience-enhancing mechanisms such as redundancy, adaptability, and proactive recovery measures [

9]. Additionally, while digital technologies, including digital twins and AI-driven predictive analytics, have the potential to strengthen maintenance resilience, their integration into existing maintenance frameworks remains limited [

19].

Despite advancements in resilience-oriented maintenance, significant gaps remain. There is a notable lack of quantitative methodologies for assessing resilience, as most existing models provide only qualitative insights without structured measurement frameworks. Additionally, the interplay between sustainability and resilience in maintenance is underexplored, with limited research addressing how organizations can simultaneously enhance both dimensions. Moreover, maintenance decision-making often relies on simplistic cost and reliability trade-offs, failing to incorporate resilience as a key factor.

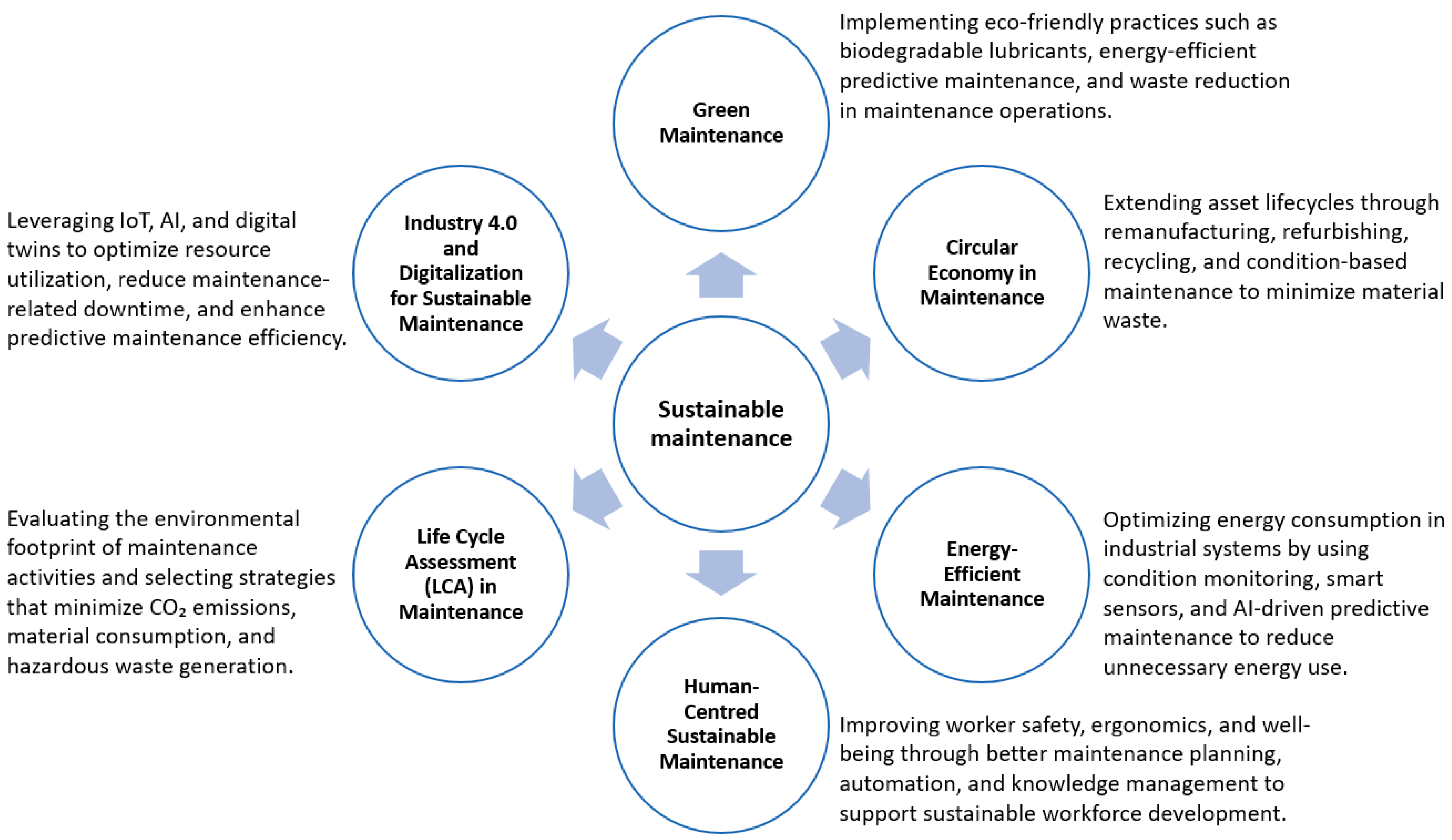

On the other hand, sustainable maintenance integrates environmental, economic, and social aspects to enhance long-term operational efficiency while minimizing negative impacts [

14,

36] (

Figure 2). Recent surveys on sustainable maintenance problems are presented, e.g., in [

13,

17,

37,

38]. Key issues include six main research areas investigated: green maintenance circular economy approach, energy efficiency, human-centered approach, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) principles implementation, and Industry 4.0 technologies, including IoT, AI, and digital twins development. Additionally, regulatory and policy compliance ensures maintenance aligns with environmental regulations and corporate sustainability goals [

14].

The theoretical framework for assessing and improving sustainable maintenance practices has recently focused on robust, multi-criteria methodologies. Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek and Antosz [

39] defined key criteria for sustainable maintenance, emphasizing that its assessment requires a structured, multi-dimensional approach rather than reliance on single indicators. Further advancing this methodological rigor, Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek and Żywica [

40] proposed integrating the Balanced Scorecard with the non-additive fuzzy integral, demonstrating the need for sophisticated, non-linear aggregation techniques to accurately capture the interdependencies among sustainability performance metrics. This line of research continued with the development of comprehensive assessment models utilizing fuzzy set theory to handle the inherent imprecision and subjectivity of sustainability criteria [

41]. These studies highlight that Fuzzy Logic is a theoretically proven and necessary tool for building robust sustainability performance models.

Despite these advancements, traditional maintenance maturity models rarely integrate sustainability systematically, highlighting the need for frameworks that assess sustainability performance using measurable indicators such as carbon footprint reduction, resource efficiency, and workforce well-being (see, e.g., [

20]). Moreover, the integration of Maintenance 4.0 technologies (like IoT and AI) must be viewed through the lens of sustainability. As demonstrated in [

42], these technologies offer new opportunities to drive sustainability-oriented maintenance, linking technological adoption directly to measurable environmental and social outcomes. As highlighted by Madreiter et al. [

43], ensuring sustainable maintenance requires identifying and leveraging key technology drivers - such as digitalization, data-driven decision-making, and human-centric approaches - that contribute to manufacturing industries’ positive environmental and social impact. Furthermore, Franciosi et al. [

20] propose a comprehensive Maintenance Maturity and Sustainability Assessment Model, which integrates sustainability aspects into maintenance practices through a multi-criteria approach, enabling organizations to align their maintenance strategies with broader sustainability goals.

As a result, future maturity models should integrate sustainability indicators, such as carbon footprint reduction, resource efficiency, and workforce well-being, to ensure alignment with long-term operational and environmental goals.

2.3. Unified Multidimensional Maintenance Perspective

The concept of maintenance maturity has evolved from a purely technical assessment of maintenance capabilities to a more comprehensive, multidimensional construct. Contemporary research emphasizes that effective maintenance should ensure asset availability and reliability and align with broader organizational goals such as sustainability and resilience. However, existing maturity models focus on isolated aspects - operational excellence, sustainability, or resilience - without offering an integrated perspective.

Several studies have highlighted this fragmentation. For example, Franciosi et al. [

20] propose a Maintenance Maturity and Sustainability Assessment Model that considers environmental, social, and economic dimensions yet does not explicitly address system resilience. Conversely, Madreiter et al. [

43] identify key technology drivers to promote sustainable maintenance but emphasize the need for integrating these drivers with resilience strategies to maintain operational continuity under uncertainty.

This view aligns with Fiksel [

44], who argued that resilience and sustainability, while often treated separately, should be approached as interconnected system properties essential for long-term industrial viability. Similarly, Thomas et al. [

45] emphasized the need to profile and quantify manufacturing systems’ resilience and sustainability performance, identifying that a lack of integration between these concepts limits strategic planning and response capabilities.

Moreover, Briatore and Braggio [

19] highlight the potential of Maintenance 4.0 technologies - such as IoT, Digital Twins, and Cyber-Physical Systems - as key enablers of resilience and sustainability. However, their proposed implementation roadmap still lacks an embedded maturity model to measure the progression and effectiveness of these technologies in supporting both dimensions simultaneously.

Recent research also demonstrates that the transition toward predictive maintenance is increasingly supported by artificial intelligence (AI) and data-driven decision-making frameworks. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms can process heterogeneous sensor data to predict failures, optimize maintenance scheduling, and enhance operational resilience [

46]. Similarly, a comprehensive review by Ucar et al. [

47] in Applied Sciences highlights that trustworthy AI and explainable predictive models are becoming critical for ensuring sustainable and resilient maintenance ecosystems.

Despite these advancements, no existing maturity model holistically integrates the dual dimensions of resilience, focusing on adaptability, anticipation, recovery, and sustainability, encompassing resource efficiency, environmental impact, and human well-being. This lack of hybrid models becomes especially critical in increasingly volatile operating environments, where organizations must cope with unpredictable disruptions while meeting sustainability targets.

Sagharidooz et al. [

18] underscore the value of sustainability-informed maintenance optimization in their work on power transmission networks. Yet, their reliability-based models do not address system adaptability or continuity under disturbance. Similarly, Vimal et al. [

48] advocate for frameworks that balance resilience and sustainability in circular and sharing systems, highlighting the urgent need for models capable of managing trade-offs and uncertainty across dynamic industrial networks.

Furthermore, resilience in maintenance is often treated as a reactive capability rather than a structured, measurable element of maturity. This limits its practical implementation and the ability to benchmark progress over time. The summary of the recent maturity models is presented in

Table 1.

A comparative analysis of the current state-of-the-art in maintenance maturity modeling (

Table 1) reveals significant limitations that the IMMM is specifically designed to overcome. First, the vast majority of existing models (13 out of 16 listed) are fundamentally One-dimensional. These models assess maturity in isolated silos, failing to capture the complex interdependencies required for modern strategic planning. While some recent models, such as [

3,

6], and [

20], adopt a Multi-dimensional approach, they still exhibit key shortcomings. Second, regarding scope, even the multi-dimensional models fail to holistically integrate the dimensions critical for today’s dynamic environment. For instance, Sustainability is only a core focus in [

20], and models explicitly integrating Resilience are rare [

6]. The IMMM uniquely combines the five strategic potentials, Reliability, Safety, Resilience, Flexibility, and Sustainability, to provide a truly comprehensive assessment of an organization’s future-readiness. Finally, in terms of methodology, most models rely on deterministic approaches. Only the FMMR [

6] uses Fuzzy Logic. The IMMM leverages this methodology not only for assessment but also to achieve a crucial practical advantage: it transforms subjective, linguistic expert knowledge (necessary in data-scarce environments like SMEs) into a precise, quantitative score. This Fuzzy Logic-based assessment provides a superior, non-rigid alternative to the deterministic methods prevalent across the field.

Recent theoretical advances in asset management have shifted from deterministic prognosis to robust, uncertainty-aware modeling of system health, particularly addressing issues where measurement data is imprecise or noisy. This trend is exemplified by sophisticated research focusing on overcoming data limitations, such as robust degradation analysis with non-Gaussian measurement errors [

49] and methods for handling measurement errors in degradation-based burn-in procedures [

50]. This work acknowledges that advanced data-driven maintenance models (characteristic of Maturity Levels 4 and 5) often fail when faced with real-world complexities such as sensor faults, environmental noise, or human subjectivity, which lead to non-linear, non-Gaussian uncertainties. While these advanced statistical methods offer powerful diagnostic capabilities, their complexity often limits their practical adoption in conventional industrial settings (Maturity Levels 2–3) and they require massive, clean data sets.

This creates a distinct theoretical gap: few maturity models successfully bridge the highly complex analytical methods needed to manage non-Gaussian uncertainty with the practical need for interpretability and resilience in data-scarce industrial environments. Therefore, the primary theoretical contribution of the (IMMM is the deployment of Fuzzy Logic as a robust, non-statistical framework to explicitly operationalize the management of non-Gaussian uncertainty and linguistic ambiguity. The IMMM provides a transparent mechanism to systematically integrate expert judgment, which itself acts as a non-linear filter for noisy, incomplete, or non-Gaussian data, into the strategic maintenance decision-making process, a capability currently lacking in both purely deterministic and overly specialized prognostic models.

Following the literature review, there is a clear research gap in developing tools that support proactive, uncertainty-aware decision-making while ensuring operational continuity and long-term sustainability performance. In this context, the integration of AI-enhanced analytics and fuzzy logic reasoning becomes a promising direction for advancing maintenance maturity assessment. Building upon the literature review, one promising direction to address the identified research gap is the application of fuzzy logic in maintenance decision-making. Fuzzy logic provides a robust framework for dealing with uncertainty, imprecision, and subjectivity - characteristics that are inherent to real-world industrial environments [

51]. Maintenance systems often operate under incomplete or ambiguous data conditions, such as expert estimations, imprecise measurements, or unpredictable disturbances. Traditional binary or crisp decision models are limited in their ability to accommodate these complexities [

52].

Fuzzy logic enables the modeling of expert knowledge through rule-based systems (e.g., IF-THEN rules), allowing qualitative insights and experience to be systematically integrated into the decision-making process. It also supports the aggregation of multiple evaluation criteria - such as reliability, flexibility, resilience, and sustainability - without oversimplifying them into deterministic scores. Unlike previous multi-dimensional maturity models, the proposed Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model integrates fuzzy logic with multidimensional assessment under uncertainty, providing a unified, adaptive, and explainable approach to supporting strategic maintenance decisions. This is particularly important when assessing multidimensional maturity and planning maintenance strategies that must simultaneously ensure operational continuity and long-term environmental and social responsibility [

51].

In addition, a significant limitation of many contemporary maintenance maturity models is their reliance on extensive historical data or advanced monitoring systems (characteristic of Maturity Levels 4 and 5). This reliance on Big Data renders them practically irrelevant for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) or organizations in initial maturity stages (L1/L2), which typically operate in less data-rich environments. Our proposed Fuzzy Logic-based approach directly addresses this challenge. Fuzzy inference systems are designed to process linguistic variables and expert knowledge rather than precise numerical data, making the model inherently more robust when data is incomplete, imprecise, or unavailable. This flexibility ensures that the IMMM remains a powerful diagnostic and predictive tool, even when relying on the subjective judgment (tacit knowledge) of maintenance experts and managers within SMEs.

Table 1.

Summary of the recent maintenance maturity models available in the literature.

Table 1.

Summary of the recent maintenance maturity models available in the literature.

| Ref. |

Model name |

Publ. Year |

Dimension type |

Key dimensions covered |

Number of maturity levels |

Methodological basis |

Assessment approach |

Application context |

| [26] |

Reliability Centred Maintenance Maturity |

2003 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

5 |

RCM-based approach |

Conceptual |

Various industries |

| [53] |

Software Maintenance Capability Maturity Model (SMCMM ) |

2004 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

4 |

Capability maturity modeling |

Model architecture |

Software |

| [54] |

The House of Maintenance-based Capability maturity model |

2009 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

5 |

Capability maturity modeling |

Workshop, questionnaire |

Various industries |

| [55] |

Maintenance Management Information Maturity model |

2012 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

2 |

IT-maturity based |

Not specified |

Various industries |

| [1] |

Organization maturity level for maintenance management |

2012 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

3 |

Maintenance strategy |

Interview |

Various industries |

| [56] |

Maintenance Maturity Assessment method |

2013 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

5 |

Capability maturity modeling |

Maturity assessment based on scorecards |

Manufacturing industry |

| [57] |

PriMa-X Reference Model |

2018 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

3 layers |

Prescriptive maintenance strategy |

Reference model based on ML |

Various industries |

| [58] |

Knowledge-based Maintenance Maturity model |

2019 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

4 |

Knowledge-based maintenance strategy |

Performance indicators-based assessment |

Cyber-physical production systems |

| [27] |

Maintenance Maturity Level based on TPM Pillars |

2020 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

8 |

TPM-based approach |

Multi-attributive Border Approximation method |

Public service sector |

| [59] |

Organization performance maturity level for maintenance management |

2020 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

5 |

World-class concept based |

Self-assessment based on reading the tables’ content |

Various industries |

| [60] |

Asset Management Maturity model |

2022 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

6 |

ISO 55001:2014-based |

Interviews, direct observation, correlation index, scoring method |

Heavy equipment |

| [61] |

M³AIN4SME |

2022 |

One-dimensional |

Maintenance |

5 |

Literature review, expert validation |

Survey-based assessment |

SMEs |

| [3] |

Asset maintenance maturity model (AMMM) |

2013 |

Multi-dimensional |

People and environment, functional and technical aspects, maintenance budget |

3 |

Capability maturity modeling |

Performance measurement, ANP method |

Asset maintenance domain |

| [6] |

FMMR (Fuzzy Maintenance Maturity Rating) |

2021 |

Multi-dimensional |

Resilience, risk, maintenance performance |

5 |

Fuzzy logic, expert input |

Fuzzy assessment model |

Industrial systems |

| [20] |

Maintenance Maturity and Sustainability Assessment Model |

2023 |

Multi-dimensional |

Environmental, social and economic dimensions of maintenance; sustainability |

5 |

Literature, expert opinion, analytical assessment |

Survey research, mathematical formulations for maturity evaluation |

Manufacturing companies |

| Our model |

IMMM (Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model) |

2025 |

Multi-dimensional |

Reliability, Safety, Resilience, Flexibility, Sustainability |

5 |

Fuzzy Logic, Multi-Potential Framework |

Quantitative Score from Linguistic Input, Predictive Scenario Analysis |

Industrial Systems (Cross-sectoral applicability) |

By embedding fuzzy inference mechanisms into maturity assessment models, organizations can better quantify their current capabilities and evaluate improvement paths even in the presence of uncertainty. Thus, fuzzy logic emerges as a valuable tool to support proactive, informed, and uncertainty-aware maintenance decisions, effectively bridging the gap between resilience and sustainability in dynamic industrial contexts [

62,

63].

In the following sections of this paper, a descriptive model for the Maintenance Maturity approach is presented. This model outlines the conceptual foundation for assessing maturity across key dimensions such as reliability, safety, resilience, agility, and sustainability.

3. Proposed Maintenance Maturity Model

This section outlines the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM), which integrates reliability, safety, flexibility, resilience, and sustainability principles into a comprehensive maturity assessment framework. The model is designed to provide a flexible, quantitative, and adaptive approach to evaluate the maturity of maintenance systems under uncertainty. It uses fuzzy logic to capture the subjectivity and imprecision inherent in maintenance decision-making.

3.1. Conceptual Framework for IMMM

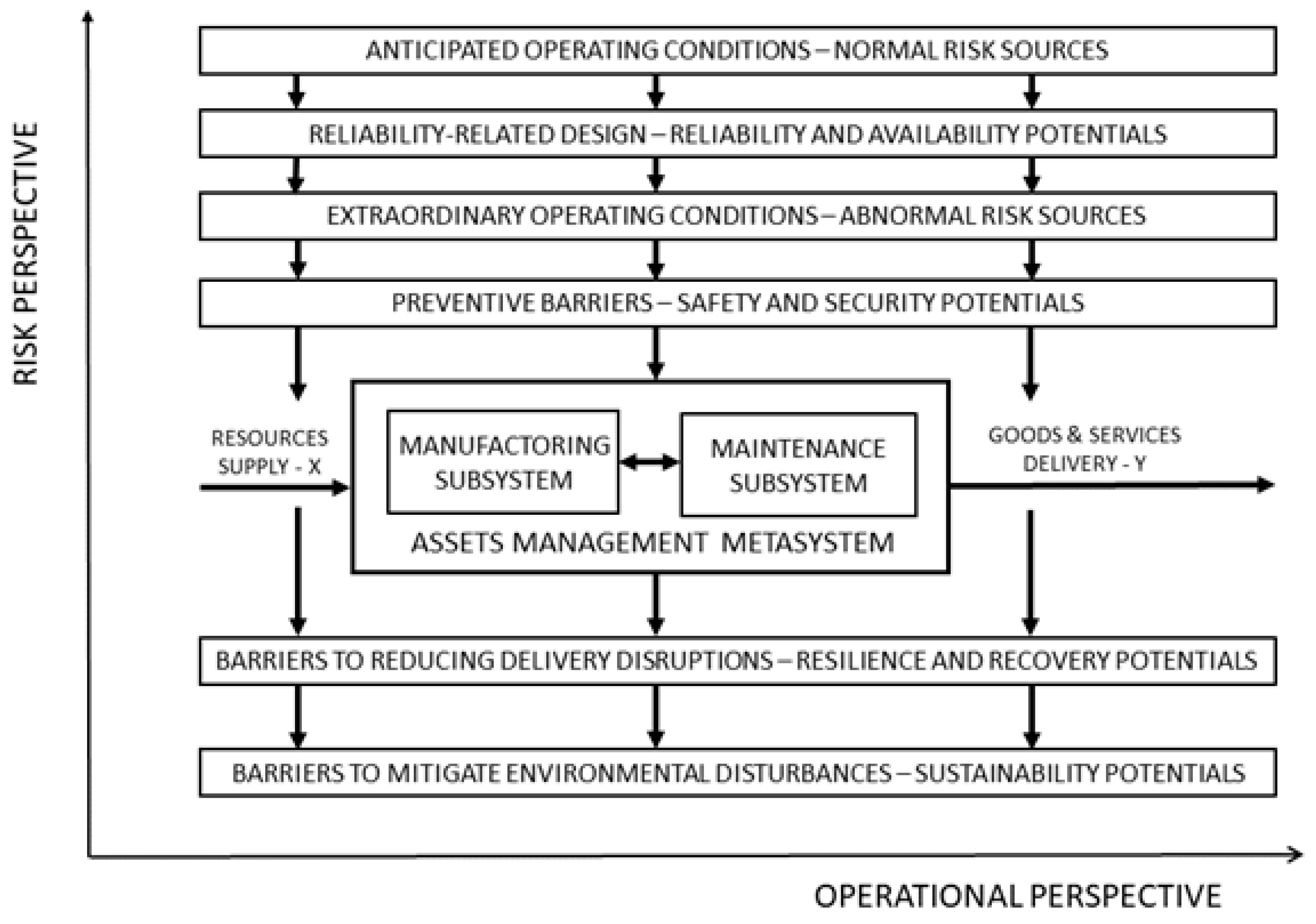

The Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) development is grounded in a systemic and risk-informed asset management approach, integrating operational continuity concepts, proactive risk mitigation, and sustainability. As a foundation, the proposed model draws on a multi-layered perspective that conceptualizes maintenance as a technical function and a strategic enabler of organizational resilience, operational agility, and sustainability.

The proposed approach adopts a layered barrier model along the vertical risk perspective, representing escalating levels of defense against operational, environmental, and systemic disturbances (

Figure 3).

From the operational perspective, a well-functioning production or service system efficiently transforms inputs (X) into outputs (Y), relying on stability, reliability, and performance optimization. Within this steady-state scenario, maintenance management typically focuses on reliability-related activities, such as preventive inspections, scheduled servicing, and condition-based monitoring, ensuring that assets perform their intended functions without failure. However, despite rigorous operational planning and asset management, real-world systems are inevitably exposed to disturbances, uncertainties, and abnormal events, ranging from internal component failures to external shocks or unpredictable environmental conditions.

This reality necessitates the consideration of a second, risk-informed perspective, complementing the operational viewpoint. This perspective is grounded in risk analysis and introduces an integrated framework of barrier-based defense layers designed to ensure operational reliability, resilience, and long-term sustainability. These layers support the system’s ability to maintain continuity, adapt to disturbances, and evolve in the face of emerging risks.

To address the multidimensional nature of uncertainty, the model introduces three interconnected protective layers:

preventive barriers – safety and security potentials: representing the system’s first line of defense, this layer encompasses proactive maintenance strategies to anticipate and avoid failures before they occur. Examples include condition-based maintenance, safety inspections, digital diagnostics, and security protocols. These activities form the foundation of a resilient operation by enhancing predictability and reducing the likelihood of incidents, tightly coupling maintenance with reliability engineering and preventive risk management,

disruption mitigation barriers – resilience and recovery potentials: when disturbances do occur, this second layer enables the system to absorb shocks and quickly recover. Key mechanisms include contingency planning, emergency maintenance procedures, flexible resource allocation, workforce cross-training, and redundancy in critical components. Maintenance plays a central role here as an enabler of adaptive capacity, facilitating real-time decision-making, repair prioritization, and recovery orchestration without significant performance degradation,

environmental disturbance mitigation barriers – sustainability potentials: the third layer embeds sustainability into maintenance practices, supporting the system’s long-term economic and ecological performance. This includes minimizing energy and material usage, extending equipment lifecycles, reducing waste, and integrating circular economy principles. Maintenance here is an operational function and a strategic lever contributing to eco-efficiency, compliance with environmental standards, and alignment with ESG goals.

These layered defense mechanisms operate across the same operational flow of inputs and outputs, yet they add depth and robustness to the system’s capability. The maturity of the maintenance system, especially its ability to integrate reliability, resilience, and sustainability dimensions, determines how effectively an organization can maintain continuity in the face of uncertainty while also achieving long-term performance objectives.

From this conceptual baseline, the IMMM structures maintenance maturity around five interdependent potentials, each rooted in a specific engineering knowledge domain and tied to measurable system attributes. These maintenance maturity potentials (P1–P5) reflect both short-term adaptability and long-term sustainability objectives (see [

25]).

This five-potential structure enables a holistic assessment of maintenance systems, bridging the traditionally fragmented domains of reliability, safety, resilience, flexibility, and sustainability. It reflects the layered conceptual foundations described earlier, where:

Reliability and safety align with preventive barriers,

Resilience and flexibility support disruption recovery and short-term adaptation,

Sustainability addresses long-term environmental and resource concerns.

A five-level Maintenance Maturity Matrix is proposed to assess each potential’s development in practical settings. This matrix captures the progression of an organization’s maintenance capabilities across the defined five maturity levels (

Table 2).

Following this, the proposed diagram illustrates the IMMM framework for assessing and improving maintenance function maturity (

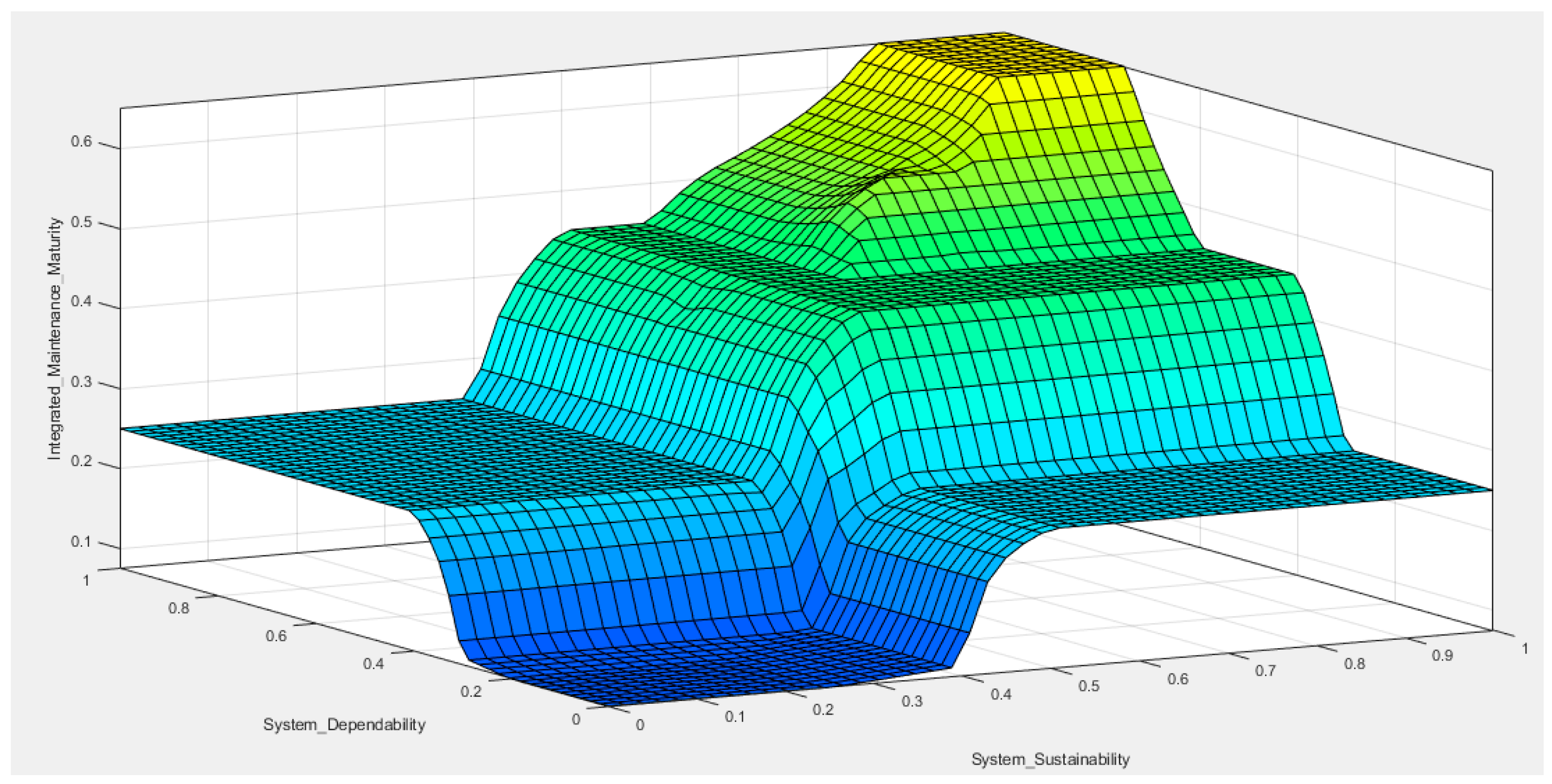

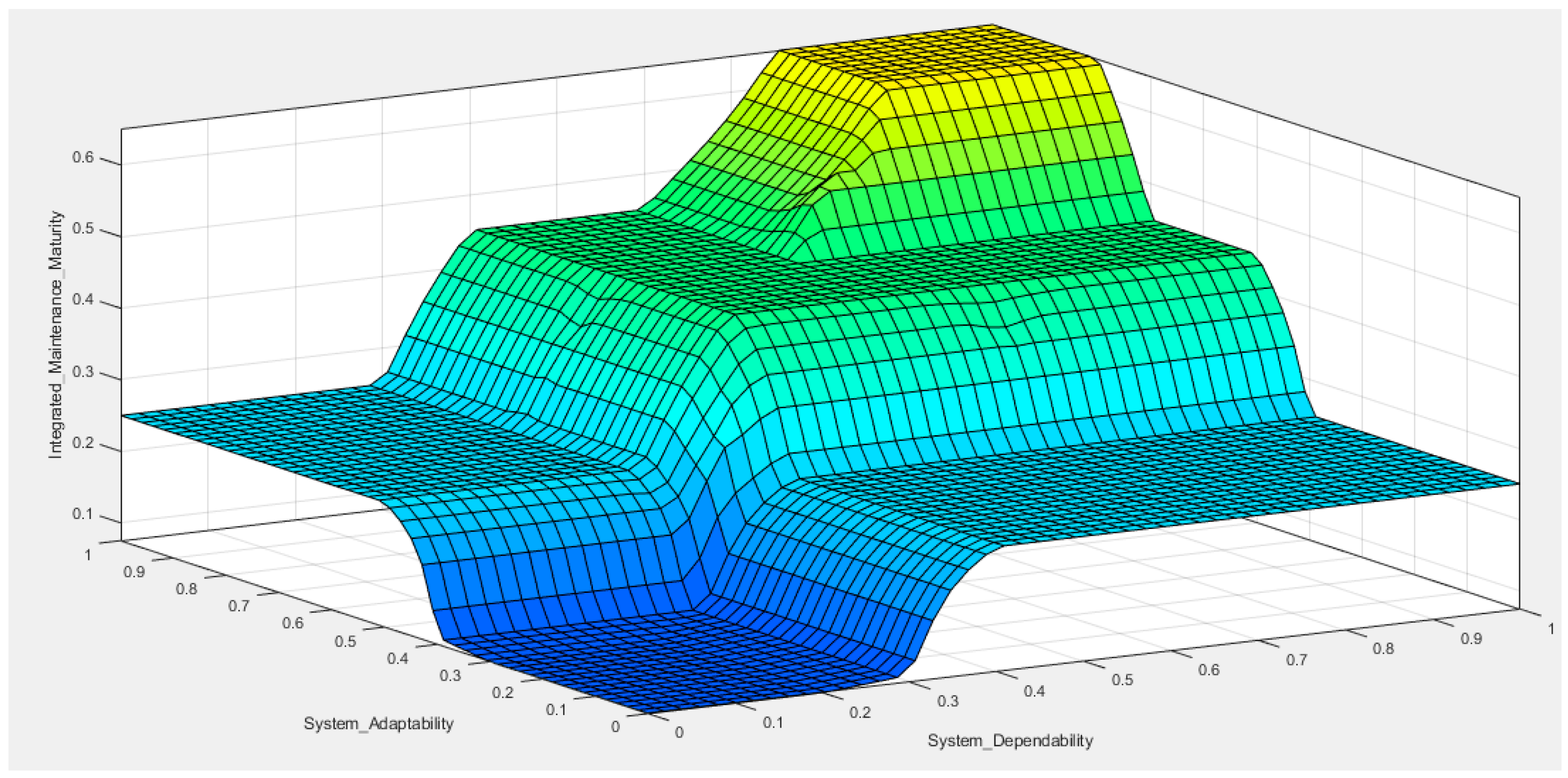

Figure 4). It links five core Potentials (P1–P5) – Reliability/Availability, Safety/Security, Resilience/Recovery, Flexibility/Agility, and Environmental Impact – to three higher-level System Maturity Dimensions: System Dependability, System Adaptability, and System Sustainability. These dimensions collectively determine the organization’s overall System Maintenance Maturity Level, progressing through five stages (L1–L5): Initial, Managed, Standardized, Predictable, and Innovating.

To provide a more realistic and system-oriented evaluation, the model integrates two additional input variables to enrich the assessment of specific dimensions:

Technology Adoption Capability (TAC), introduced as an additional input to the System Adaptability dimension, reflects the organization’s capability to adopt, integrate, and scale new technologies (e.g., digital tools, automation, AI). While Flexibility/Agility (P4) measures operational adaptability in maintenance, Technology Adaptability captures the infrastructure and cultural readiness for change, thus ensuring a more comprehensive view of adaptive potential,

Energy-Aware Maintenance level (EAML), added as a complementary input to the System Sustainability dimension, evaluates how effectively the organization incorporates energy efficiency considerations in its maintenance processes. This includes adopting energy-efficient technologies, scheduling maintenance in energy-optimized windows, and reducing energy consumption during maintenance activities. While Environmental Impact (P5) focuses on the outcome side (e.g., emissions, waste), EAML addresses the organization’s internal practices aimed at minimizing energy consumption, further strengthening the sustainability pillar from both operational and strategic perspectives.

By incorporating these additional input parameters, the IMMM provides a more holistic and fine-grained perspective on maintenance maturity, enabling organizations to understand their current state and identify strategic levers for progress toward greater efficiency, resilience, and sustainability in maintenance systems.

To sum up, the IMMM’s strength lies in its ability to integrate technical and strategic maintenance dimensions within a coherent, flexible assessment structure. By combining the proposed framework with fuzzy logic inference mechanisms (elaborated in

Section 3.2), the model enables nuanced evaluations under uncertainty, reflecting real-world complexities in industrial environments.

3.2. Fuzzy Logic-Based Assessment Methodology

The proposed approach is based on fuzzy logic and the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) structure for the developed maintenance maturity assessment methodology. The model assumes that maintenance maturity can be evaluated through five defined maintenance maturity potentials

Pi (according to

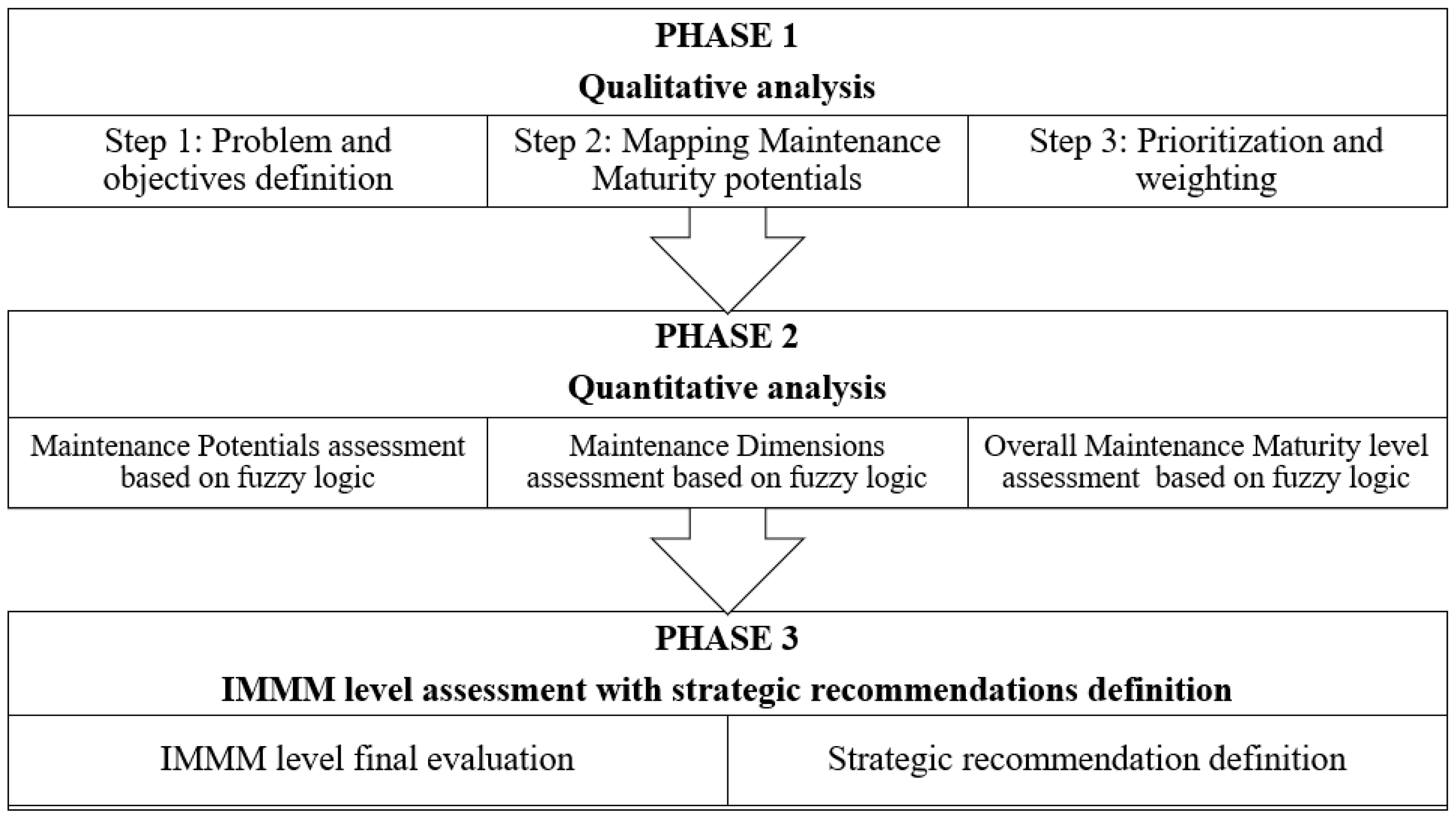

Table 1). Each potential is assessed individually, considering its performance level and relative importance in the organization. The methodology follows a structured three-phase process, which is presented in

Figure 5.

3.2.1. Qualitative Analysis - Identification and Structuring of Maintenance Maturity Potentials

In the first phase of the fuzzy logic-based methodology for assessing maintenance maturity, a qualitative analysis is carried out to define the key Maintenance Maturity Potentials (P1–P5) and their associated evaluation parameters. This foundational phase aims to structure the overall model by identifying what is important to measure and how those measurements should reflect the current and desired state of the maintenance function. It includes three main steps.

Step 1: Problem and objectives definition

The process begins by analyzing the organization’s current maintenance system. This includes identifying present challenges, performance gaps, and strategic objectives related to reliability, safety, resilience, responsiveness, and sustainability. The system’s context - such as industry type, technology level, and regulatory environment - also significantly shapes this understanding.

Step 2: Mapping Maintenance Maturity potentials (P1–P5)

This step defines the five core potentials of the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM), which serve as pillars for evaluating the comprehensiveness and advancement of a maintenance function. These potentials include (according to

Table 2):

P1: Reliability and Availability – potential that captures the system’s ability to perform its required functions under stated conditions over a defined period,

P2: Safety and Security – the dimension that protects personnel, assets, and data. It includes occupational health and safety performance, incident rates, risk mitigation strategies, and cybersecurity readiness in maintenance activities,

P3: Resilience and Recovery – potential assesses the system’s ability to absorb disturbances, adapt to changing conditions, and recover quickly from failures or disruptions. It involves redundancy strategies, emergency procedures, and continuity plans,

P4: Flexibility and Agility – a potential related to how quickly and efficiently the maintenance system can respond to internal and external changes, such as shifts in production priorities or unexpected breakdowns. It includes responsiveness, reconfigurability, and decision-making agility,

P5: Environmental impact – potential that reflects the environmental and social responsibility of the maintenance system. It includes energy consumption, resource efficiency, waste reduction, and alignment with ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) goals.

Each potential is supported by three key components: knowledge areas, measurement indicators, and performance objectives. Knowledge areas define the competencies and practices necessary for maturity development (e.g., condition monitoring, RCM, predictive maintenance for P1). Measurement indicators translate qualitative insights into quantifiable metrics, enabling systematic assessment and later fuzzy logic-based evaluation. Performance objectives set the direction for improvement and should align with the organization’s strategic priorities.

The selection of relevant parameters can follow two complementary approaches. The expert-driven approach gathers insights through expert panels, interviews, or Delphi studies [

64], capturing tacit and context-specific knowledge. Alternatively, structured decision-making methods such as AHP, DEMATEL, BWM, TOPSIS, or PROMETHEE [

65] support the objective prioritization of parameters. In data-rich environments, machine learning or clustering methods (e.g., PCA) may be applied for evidence-based selection. Hybrid approaches combining expert judgment with analytical techniques often yield the most balanced and context-sensitive outcomes.

Ultimately, the selection approach depends on the organization’s decision-making culture, availability of expertise, and the level of granularity desired in the assessment. Combining methods may offer comprehensive results, balancing expert intuition with analytical rigor. In addition to supporting identifying and selecting appropriate indicators, practitioners may refer to structured indicator frameworks, such as ISO 55000 series [

66], standard EN15341 [

67], or other relevant industry-specific standards or benchmarking databases.

Step 3: Prioritization and weighting

The final step in the qualitative phase involves assigning priority weights to the five maintenance maturity potentials and their associated indicators. This step ensures that the model reflects the relative importance of different aspects of maintenance maturity within a given organizational context. Weighting is a foundational input for the fuzzy inference system used in the next phase of the methodology, influencing how the maturity level is ultimately scored and interpreted.

The weighting process can follow one of two general approaches: expert-based or structured weighting methods. Expert-based weighting relies on the insights of domain experts, maintenance managers, and other key stakeholders familiar with the organization’s operational goals and strategic priorities. Weights can be assigned through direct estimation (e.g., allocating percentages across the five potentials), pairwise comparisons, or structured interviews. Consensus-building techniques, such as the Delphi method, may also be applied to reduce bias and improve the reliability of expert-derived weights.

For greater rigor and reproducibility, the second approach is recommended. Here, formal multi-criteria decision-making techniques can be applied to generate the weights. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is particularly effective for this task, as it allows decision-makers to perform pairwise comparisons and derive a consistent weight distribution [

68]. Other methods include the Best-Worst Method (BWM) for lower cognitive load or entropy-based weighting, which leverages available data to quantify the information contribution of each indicator. DEMATEL can also be used to understand causal relationships among indicators, helping prioritize those with the most influence.

In both approaches, the weights should be normalized (e.g., sum to 1 or 100%) to ensure consistency in aggregation during the fuzzy logic evaluation. It is also recommended that the final weights be validated with stakeholders to ensure alignment with the organization’s risk tolerance, regulatory obligations, and long-term maintenance objectives.

The result of this step is a complete, weighted framework that reflects qualitative expert insights and, optionally, quantitative decision-structuring. These weights will be used in the fuzzy aggregation logic to ensure that more critical aspects of maintenance maturity exert greater influence on the final maturity assessment outcome.

To ensure methodological transparency, expert workshops are to be organized to support the weighting and rule-base construction. A panel of eight experts was formed, including maintenance managers, reliability engineers, and academic researchers with a minimum of 10 years of experience in maintenance management or asset reliability. Experts were selected based on three main criteria: (1) professional experience in industrial maintenance systems, (2) familiarity with predictive and sustainable maintenance practices, and (3) involvement in reliability or resilience-focused projects. The workshops followed a Delphi-like structure comprising three iterative rounds. In the first round, individual experts provided preliminary weight estimations and rule proposals. In the second round, anonymized feedback was shared to highlight divergences and promote convergence. In the third round, final weights and rule adjustments were consolidated once a consensus threshold (standard deviation <10%) was reached. This structured approach minimized cognitive bias and ensured consistent expert input across the IMMM potentials and indicators.

3.2.2. Qualitative Analysis - Expert Evaluation and Fuzzy Aggregation

The main goal of this phase is to determine the overall maintenance maturity level of the organization and provide actionable recommendations for improvement based on the results of the fuzzy evaluation.

At the initial stage of this phase, expert opinions are collected regarding the assessment of each maintenance maturity potential within the IMMM framework (

Figure 4). Experts evaluate the values of key parameters, such as reliability, safety, resilience, agility, and environmental impact, based on observed practices and system characteristics. These evaluations use linguistic scales to reflect the inherent uncertainty and subjectivity in maintenance performance assessment. The workshops described earlier also should serve to validate the consistency of linguistic term interpretation among experts. Before aggregation, an inter-rater consistency check should be performed, and individual fuzzy evaluations should be compared using the Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) method. Cases where deviation exceeded 15% are to be revisited collectively to ensure semantic alignment of expert judgments. Furthermore, a simple sensitivity analysis should be conducted by varying assigned weights ±10% across the five maturity potentials to evaluate the robustness of the final maturity score. It is expected that such variation led to less than ±0.03 change in the global maturity level, confirming the model’s stability and low sensitivity to individual expert bias. This procedure provides an additional layer of transparency in handling uncertainty and validating the fuzzy-based aggregation.

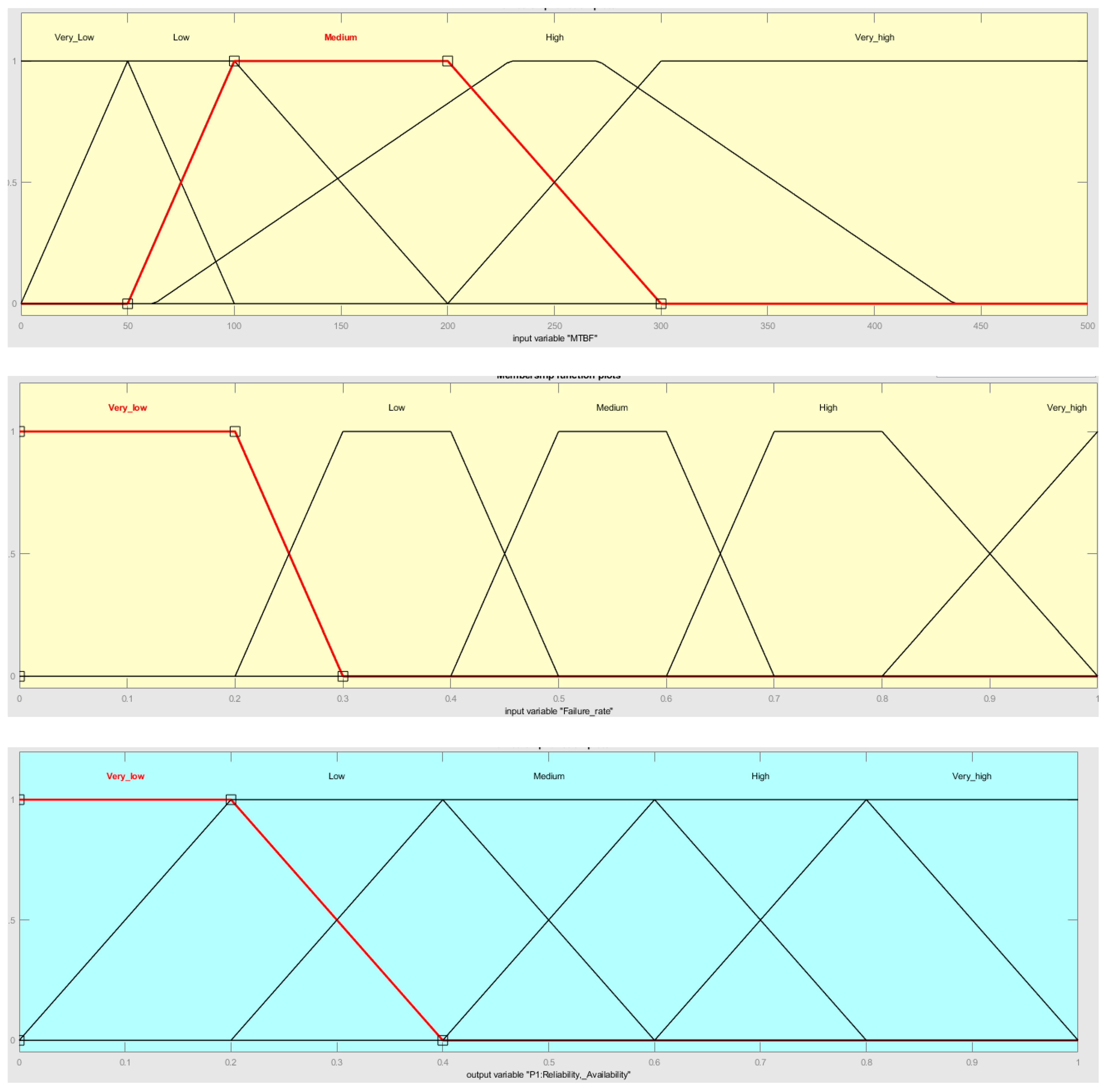

The appropriate definition of linguistic variables is grounded in expert knowledge and is tailored to the characteristics of the maintenance domain and the type of industrial system under consideration. In the subsequent step, the linguistic terms are modeled using fuzzy set theory to enable systematic and transparent reasoning under uncertainty.

Fuzzy set theory enhances comparative analysis’s consistency and improves expert reasoning’s transparency under uncertainty [

69]. Accordingly, in the context of maintenance maturity assessment, the modeled parameters are represented using trapezoidal fuzzy numbers, facilitating the aggregation and interpretation of fuzzy outputs.

A trapezoidal fuzzy number is defined as

Az = (

a,

b,

c, d), where

a and

d represent the lower and upper bounds of the FN, and

b and

c define the core (i.e., the interval of full membership). The corresponding membership function is given by [

70]:

Consequently, the linguistic variables associated with input indicators (maturity-related attributes) and output evaluations (maturity levels) are defined using triangular and trapezoidal membership functions, respectively. These fuzzy representations allow for a nuanced and robust assessment of maintenance maturity within the IMMM framework.

Although the present approach utilizes Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs), it is worth noting that multiple methods exist for constructing membership functions for fuzzy variables, each depending on the application context and availability of data (see [

71] for further discussion).

In practice, defining membership functions in environments with limited or estimated data poses a challenge, as the parameters (a, b, c, d) may reflect subjective expert judgment rather than empirical distributions. To ensure the correctness and robustness of the membership functions, several measures may be applied. First, the linguistic boundaries and core intervals will be established through iterative expert calibration during workshops, ensuring that different experts share a consistent interpretation of linguistic terms (e.g., “medium” or “high”). Second, sensitivity testing are to be conducted by slightly varying the membership parameters and observing the resulting impact on maturity scores, confirming that the model remained stable within acceptable ranges.

In future applications, hybrid calibration methods can be used to further improve precision—for example, combining expert-based fuzzy sets with data-driven tuning techniques such as adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) or genetic optimization algorithms. These methods allow empirical data (e.g., from CMMS or condition monitoring systems) to refine membership function parameters, thereby reducing subjectivity and increasing replicability in different industrial contexts.

Once expert assessments of individual maturity indicators are gathered using linguistic terms, these must be aggregated to evaluate each maturity potential. In line with [

72], a common and effective method for aggregating expert input is the arithmetic mean operator applied to TFNs. These aggregated fuzzy evaluations serve as the basis for determining the maturity level within each potential.

The weights defined in Phase 1 (qualitative analysis), both for indicators within a potential and for the potentials themselves, are applied to the fuzzy values. These weights reflect the relative importance of each aspect of maturity and ensure the aggregation process aligns with the organization’s strategic priorities.

Subsequent analysis follows the structure of a Mamdani-type fuzzy inference system (FIS), which has proven to be a widely accepted model for fuzzy reasoning under uncertainty [

73]. The Mamdani framework, grounded in Zadeh’s compositional rule of inference [

74], quantifies maturity performance levels based on expert-driven fuzzy inputs. The Mamdani fuzzy inference model was selected due to its interpretability, transparency, and suitability for expert-based decision environments. It allows experts to express linguistic judgments in a natural way (e.g., low, medium, high) and ensures that the reasoning process remains explainable. This approach bridges quantitative computation and qualitative understanding - crucial for maintenance decision-making under uncertainty.

The selection of the FIS architecture and Membership Functions (MFs) was justified through an evaluation against alternative methods to ensure optimal performance for a linguistic, expert-driven maturity assessment application.

Alternative FIS architectures, such as the Sugeno (Takagi-Sugeno) model, were considered but rejected. While Sugeno systems offer computational efficiency because their output is a crisp function rather than a fuzzy set, they sacrifice the interpretability necessary for a management diagnostic tool. The Mamdani model’s fuzzy output is inherently easier for maintenance experts to validate and understand, making it superior for achieving organizational acceptance and transparency in decision-support systems [

75].

Similarly, the use of Triangular and Trapezoidal Membership Functions was prioritized over smooth functions like Gaussian or Bell curves. For a maturity model based on expert consensus, the simple, piecewise linear boundaries of the Triangular/Trapezoidal MFs are easier for maintenance professionals to define and agree upon linguistically. Smooth MFs, while better for approximating noisy empirical data, introduce unnecessary mathematical complexity and ambiguity when converting qualitative expert knowledge into fuzzy sets, which is the primary data source in this application. This choice ensures high fidelity between the tacit knowledge gathered in workshops and the final model definition [

76].

The implementation of the Mamdani fuzzy model in this assessment consists of four primary components:

fuzzification – converts linguistic variables provided by experts into fuzzy numbers (in this case, TFNs), enabling a representation of values on a normalized scale from 0 to 1,

knowledge base – comprises a set of IF-THEN rules and corresponding membership functions for each input indicator across the five maturity potentials (e.g., reliability, safety, resilience),

Fuzzy Inference Mechanism (FIS) – employs fuzzy logic operations to process the rules. Specifically, the MIN operator is used to model logical conjunctions and implications. In contrast, the MAX operator aggregates fuzzy results from multiple rules,

defuzzification – converts the final aggregated fuzzy output into a crisp value using the Centroid of Area method [

77,

78]. This crisp value reflects the estimated maturity level for a given potential.

The defuzzified output z∗ is computed using the following formula [

77,

78]:

where: z* – the crisp value for the z output (defuzzified output);

– the aggregated output membership function; z – universe of discourse.

This process ultimately delivers a quantified maturity score for each of the IMMM’s five key potentials, supporting the interpretation of strengths and improvement areas in a maintenance strategy under uncertainty.

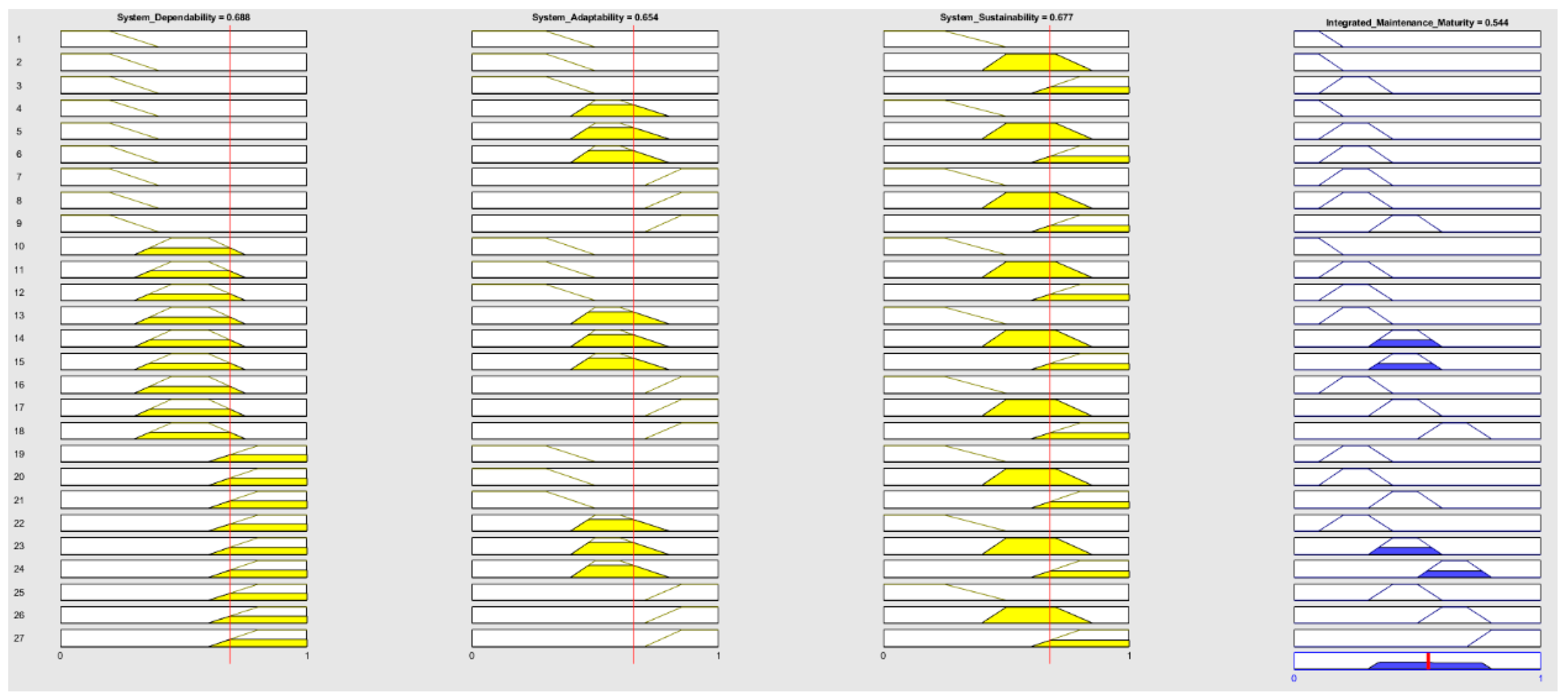

The second step in the IMMM framework regards assessing the three system maturity dimensions. The fuzzy logic approach is similar to the developed one for P1-P5 maintenance potential evaluation. Each dimension is assigned a composite fuzzy score based on the weighted aggregation of its underlying potentials. The fuzzy results may be defuzzified or maintained in linguistic form, depending on the intended granularity of analysis.

The last step in this area is the maturity level assignment. The dimension scores are then positioned within the five levels’ predefined IMMM maturity matrix (

Table 2). Based on the position of each dimension, an overall Maintenance Maturity Level is determined based on the fuzzy logic approach described above in this subsection.

At the end of the quantitative phase, the defuzzification process provides the crisp output value of the Maintenance Maturity level, an input to the last phase – the Output phase.

3.2.3. Integrated Maintenance Maturity Level Assessment with Strategic Recommendations Definition

Once the overall maintenance maturity level has been assessed, the next step involves designing tailored improvement actions to support advancement toward more advanced levels (Levels 4–5). These actions should prioritize areas with the lowest maturity scores, strategically significant potentials (e.g., critical to safety, reliability, or sustainability goals), and the readiness and capacity of the organization to implement change.

Organizations should first conduct a gap analysis between their current and desired maturity levels to ensure the recommendations are actionable and effective. Based on this, priorities should be established, focusing on critical business risks and strategic goals. Actions offering significant impact with limited resource requirements - so-called ‘quick wins’ - should be considered early in the process. Each recommendation should be accompanied by measurable indicators (KPIs) for tracking and evaluation. For organizations implementing advanced solutions such as AI or digital twins, it is advisable to begin with pilot implementations in selected areas to evaluate value before full-scale deployment. These steps will help align the maintenance improvement strategy with operational realities and long-term ambitions.

4. Case Study

To illustrate the applicability of the proposed Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM), a case study was conducted in a manufacturing company operating in the automotive sector. The selected enterprise is a key production facility in Lower Silesia, Poland, and plays a strategic role in the company’s global operations. With over 100 years of innovation in mobility technologies, the company specializes in developing and producing safety- and efficiency-critical systems for commercial vehicles. It operates across four continents with 28 production plants and three advanced test centers, including one in Poland. The Polish branch employs approximately 3,000 people, making it the largest employment hub of the company in Europe.

The site contributes nearly 35% of the company’s global output, supplying a wide range of braking systems, suspensions, stabilization modules, and aerodynamic control systems to major OEM clients, including brands like Daimler, Scania, and Mercedes. Its operations are supported by a broad supplier base of over 500 entities worldwide. Internally, the facility is divided into seven departments, each focused on a distinct set of final products, with production involving technologically advanced processes like high-precision assembly, calibration, and functional testing under safety-critical conditions.

Given the manufacturing operations’ scale, complexity, and safety relevance, the maintenance function is pivotal in ensuring production continuity, minimizing operational risks, and aligning with sustainability expectations. Therefore, this company was selected as an ideal candidate for testing the IMMM methodology in a real-world industrial environment. Indeed, the main steps of the adopted approach for the case company are presented below.

4.1. Qualitative Analysis

Step 1: Problem and Objectives Definition

The case study began with a qualitative analysis aimed at identifying and structuring the key potentials that determine the maturity of the maintenance system in the examined company. The primary problem addressed was the need to ensure operational continuity and production reliability under conditions of increasing complexity and uncertainty. Despite the company’s high technological advancement and well-established preventive maintenance practices, several internal and external disruptions have exposed vulnerabilities in system resilience and sustainability performance.

A deeper investigation revealed specific challenges, such as variability in machine availability, occasional delays in critical component deliveries, and the environmental impact of intensive maintenance operations. Moreover, the company’s ambition to align its practices with global sustainability standards and to prepare for the next wave of digital transformation highlighted the need for a more integrated and strategic approach to maintenance maturity assessment.

Accordingly, the main objective of the analysis was to evaluate the company’s current state across five defined maintenance maturity potentials - (P1) Reliability and Availability, (P2) Safety and Security, (P3) Resilience and Recovery, (P4) Flexibility and Agility, and (P5) Sustainability - and to identify specific improvement directions. The goal was to assess maturity levels and understand how the maintenance system could evolve to support better strategic objectives such as risk resilience, production continuity, and environmental responsibility.

Implementing the IMMM model aimed to structure the decision-making process in a way that would support evidence-based prioritization of maintenance improvements, taking into account both expert knowledge and the fuzzy nature of industrial uncertainties. This approach was expected to provide actionable recommendations tailored to the organization’s operational context, maturity ambitions, and available resources.

Step 2: Mapping Maintenance Maturity potentials (P1–P5)

In this step, the five Maintenance Maturity Potentials of the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM) were mapped to the context of the analyzed company operating in the automotive sector. The purpose was to identify the key strategic areas of maintenance performance relevant to the organization and to structure the foundation for subsequent assessment and prioritization. These maturity potentials are grounded in theoretical insights and the specific operational characteristics of the selected company.

The mapping was carried out based on the theoretical framework presented in

Table 1, adapted to the studied plant’s technological, organizational, and strategic profile. The company under analysis, located in Lower Silesia, Poland, plays a critical role in the global production network by delivering over one-third of the organization’s worldwide output. It operates several technologically advanced production departments, each responsible for different high-value systems for commercial vehicles. Maintenance in such a context is essential to ensure technical availability and support safety, rapid recovery, and sustainability in a highly automated and quality-driven environment.

The five identified Maintenance Maturity Potentials include:

P1: Reliability and Availability: this potential reflects the company’s ability to ensure uninterrupted operation of production equipment through predictive maintenance, real-time condition monitoring, and optimization of preventive activities. The company’s reliance on high-precision machining and safety-critical assemblies makes uptime and reliability a top priority. Knowledge areas include reliability-centered maintenance (RCM), sensor-based diagnostics, and predictive analytics,

P2: Safety and Security: given the organization’s focus on safety-related components such as braking and stabilization systems, maintenance must ensure strict compliance with safety protocols for operators and end-products. This includes occupational safety, risk mitigation procedures, and cybersecurity readiness. Key knowledge areas include risk assessment methodologies, human-machine interface (HMI) safety, and maintenance cybersecurity protocols,

P3: Resilience and Recovery: the company’s exposure to supply chain fluctuations and the complexity of its production setup demand high resilience. Quick recovery from breakdowns, availability of critical spares, and structured emergency procedures are essential. This potential includes knowledge areas such as failure mode analysis, recovery time optimization, and emergency scenario planning,

P4: Flexibility and Agility: due to high product diversity and changing client requirements, maintenance systems must be agile enough to adapt to evolving production schedules and machine configurations. The ability to shift resources quickly and adjust maintenance plans is critical. Related knowledge areas include modular maintenance planning, digital work order systems, agile resource scheduling,

P5: Environmental impact: as the company aligns with global ESG objectives, it seeks to improve energy efficiency, minimize waste, and reduce emissions from maintenance activities. Efforts are made to integrate circular economy principles into equipment lifecycle management. Knowledge areas include energy monitoring systems, green maintenance practices, and environmental impact assessment.

A hybrid approach was used to identify and refine the elements of each maturity potential. A series of structured interviews with maintenance engineers and continuous improvement managers provided expert input into current practices and perceived priorities. Following this, thematic knowledge areas were identified for each potential to guide specific capabilities and practices. These areas were refined based on a combination of expert consultations with site engineers and a literature-based reference to relevant standards such as EN 15341 and ISO 55000. For example, in the case of P1, the focus included real-time vibration monitoring and predictive diagnostics using AI-enabled tools already piloted at the site.

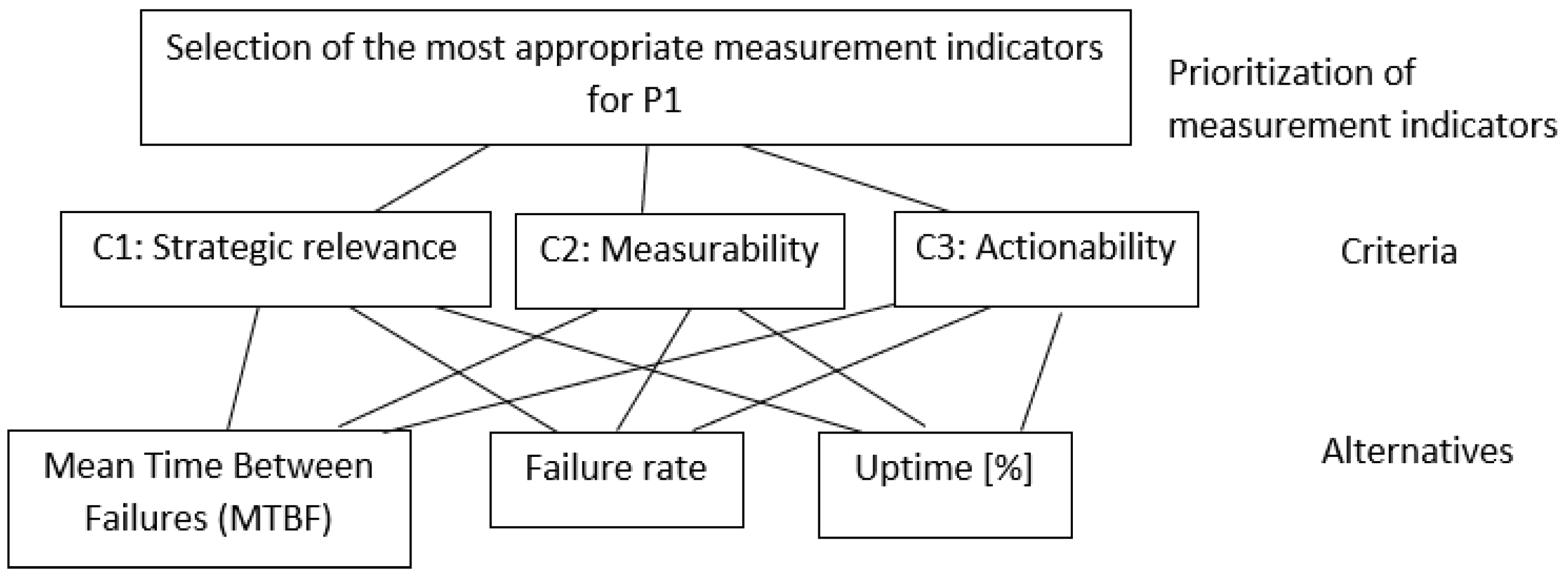

Simultaneously, selected indicators were verified using an AHP-based multi-criteria decision-making framework, ensuring traceable weighting of factors and alignment with strategic directions. Measurement indicators were proposed to provide an objective, data-driven evaluation. These included both lagging indicators and leading indicators. Indicator selection considered technical feasibility (availability of internal data) and strategic relevance (alignment with corporate goals). An example of AHP-based prioritization of measurement indicators for P1 is given in Appendix 1. Due to the performance of AHP-based prioritization of measurement indicators, for each maturity potential, two indicators with the highest rank were selected as input data for quantitative analysis.

In the end, performance objectives were set to guide improvement targets. For example, in P4, the plant aims to reduce maintenance response time by 20% within two years by expanding mobile access to work order systems. In P5, a specific goal was to reduce waste oil consumption by 15% through improved filtration and fluid analysis programs.

A reference table (

Table 3) presents indicators for each of the five maintenance maturity potentials, associated knowledge areas, and performance objectives. This table can guide organizations aiming to develop or adapt their measurement sets in line with the IMMM framework.

Step 3: Prioritization and weighting

In this step, the five Maintenance Maturity Potentials (P1–P5) and their associated measurement indicators were prioritized and assigned weights to reflect their relative importance within the organizational context. This process ensures that the final maturity assessment accurately emphasizes the most strategically relevant areas.

For this study, we adopted an expert-based approach, relying on the insights of maintenance professionals, engineers, and strategic managers familiar with the organization’s operational goals, risks, and priorities. Participants were asked to evaluate each potential’s strategic relevance and operational impact through a structured expert workshop.

Based on the consensus from expert inputs, the following normalized weights were assigned to the five maintenance maturity potentials (

Table 4).

Following this, it was possible to proceed to the next phase – quantitative analysis.

4.2. Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative analysis represents a crucial phase of implementing the Integrated Maintenance Maturity Model (IMMM). Building upon the qualitative insights, this step transforms the mapped maintenance maturity potentials (P1–P5) into measurable indicators. These indicators are then analyzed through a fuzzy logic-based framework to quantify the maturity levels, providing a more objective and data-driven evaluation. This process ensures that the strategic relevance of each maintenance potential is reflected in the final assessment. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis is performed to evaluate the robustness and flexibility of the model under varying conditions.

Following this, the first step of the quantitative analysis, according to

Figure 2, is the evaluation of maintenance maturity potentials (P1–P5). In this first stage of the quantitative analysis, the primary goal is to assess the maturity of the maintenance system using a fuzzy aggregation approach.

The fuzzy logic approach is adopted to quantify the maturity of each potential by incorporating expert knowledge and subjective evaluations. This allows for a more nuanced and flexible interpretation of the variables involved instead of a strict binary assessment. The fuzzy membership functions and linguistic terms used in this analysis enable the translation of expert assessments into quantitative scores, providing a comprehensive view of the system’s maturity level.

For each potential, linguistic terms are defined for the overall potential (e.g., Reliability, Availability) and the individual input indicators (e.g., MTBF, Failure Rate for P1). These terms represent different maturity levels, ranging from Very Low (VL) to Very High (VH), and are mapped to fuzzy membership functions. The choice of fuzzy sets reflects expert judgment on the importance and behavior of the respective indicators within the maintenance system.

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the linguistic terms and fuzzy membership functions for the first potential P1: Reliability, Availability, and its associated input variables. The assessments of potentials P2-P5 and their input variables are given in Appendix 2. The defined values are based on expert evaluations and theoretical foundations, aiming to reflect real-world scenarios in the maintenance of complex systems. The fuzzy membership functions for the input variables provide a way to quantify the system’s maturity for each potential.