Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

2.2. Trait Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Variance

| Trait | Treatment | ANOVA across Treatments | ANOVA by Treatment | |||

| Genotype (G) | Treatment (T) | G × T | Genotype | h2 | ||

| RL | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.61 |

| Drought | ** | 0.83 | ||||

| SL | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.88 |

| Drought | ** | 0.82 | ||||

| RFW | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.85 |

| Drought | ** | 0.81 | ||||

| SFW | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.91 |

| Drought | ** | 0.80 | ||||

| RDM | Control | ** | ** | NS | ** | 0.54 |

| Drought | ** | 0.41 | ||||

| SDM | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.75 |

| Drought | ** | 0.80 | ||||

| RL/SL | Control | ** | NS | ** | ** | 0.77 |

| Drought | ** | 0.81 | ||||

| RFW/SFW | Control | ** | ** | ** | ** | 0.59 |

| Drought | ** | 0.83 | ||||

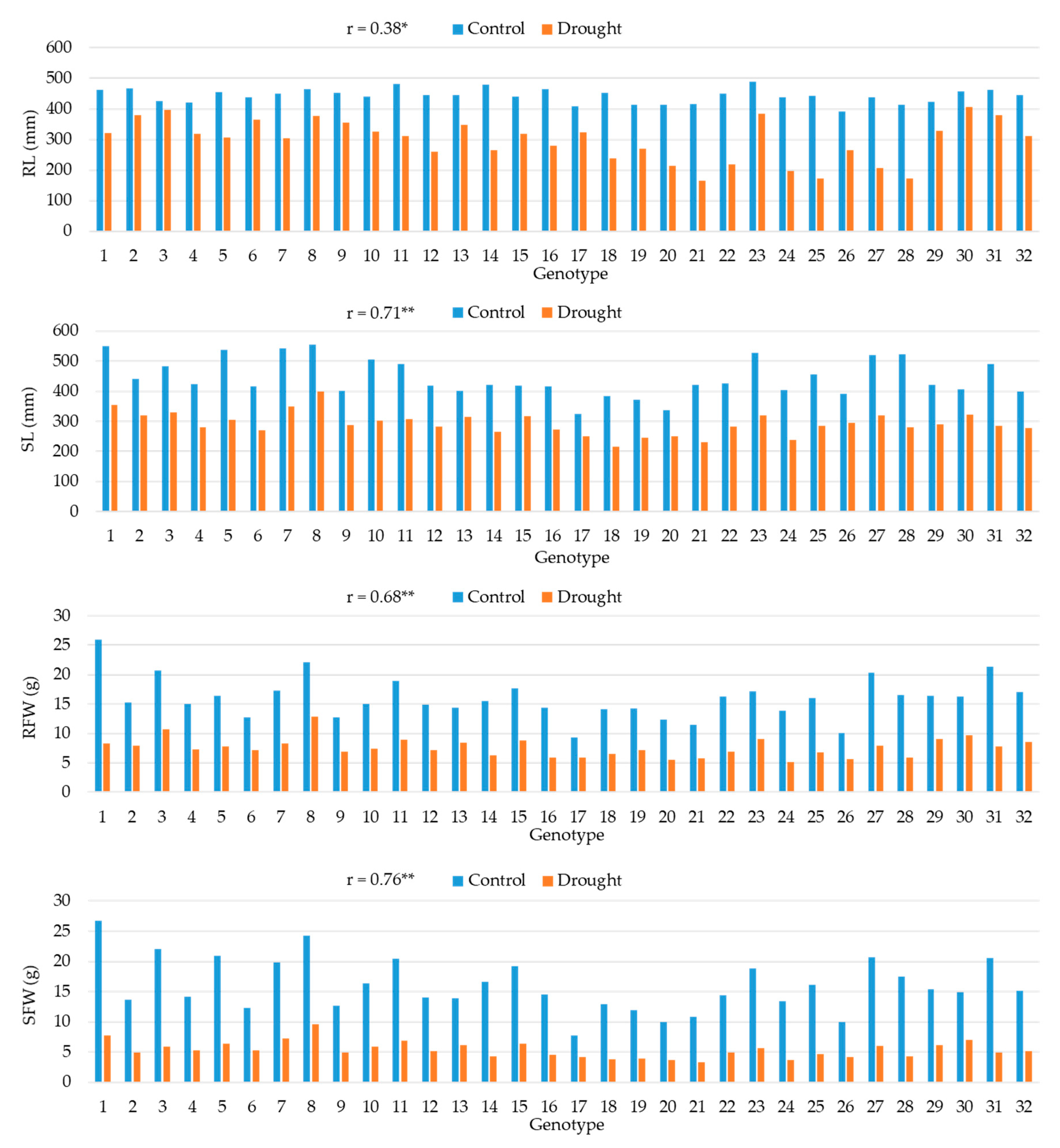

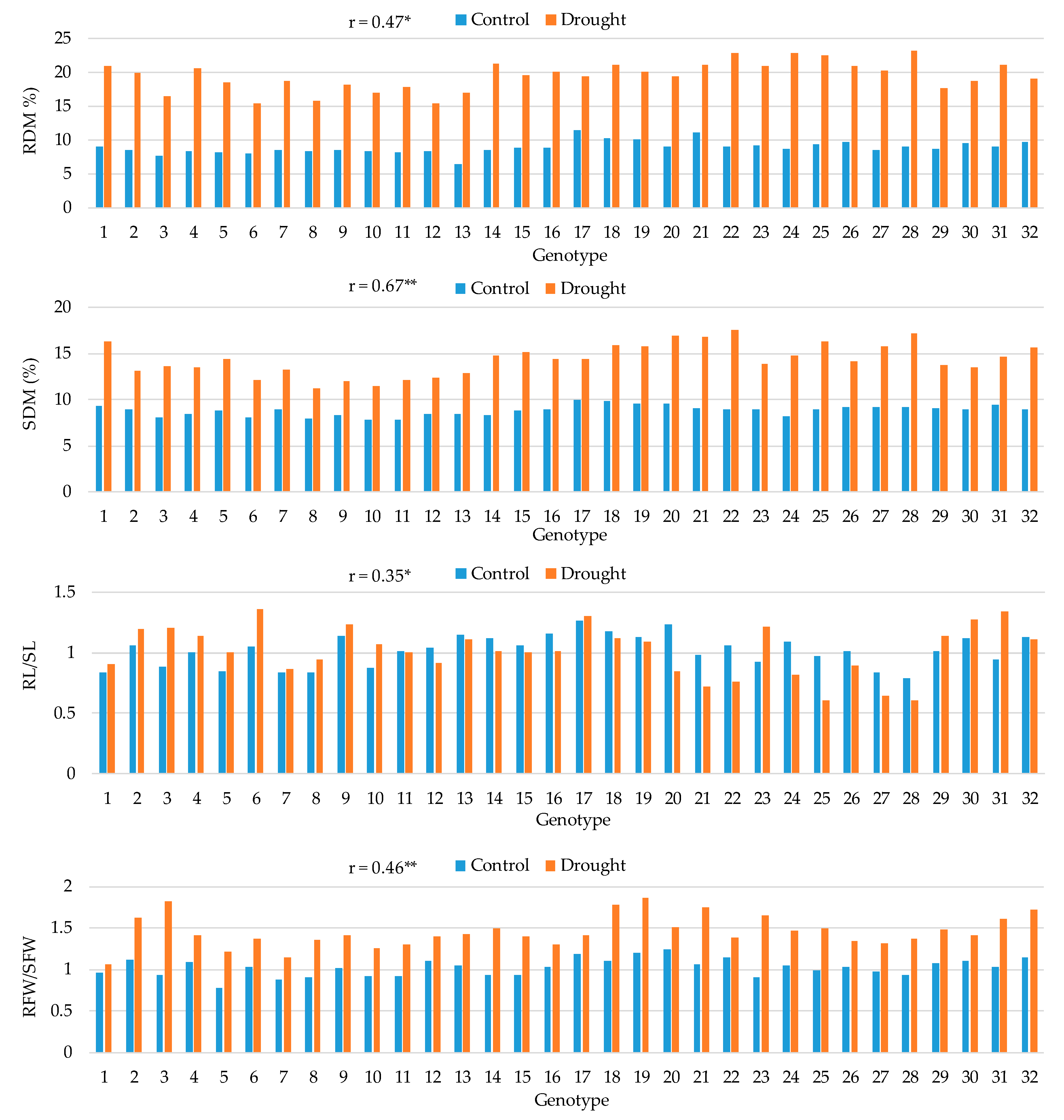

3.2. Effect of Drought on Trait Means

| Trait | Treatment | Absolute units | Change (% of Control) | |||||

| Mean | Min | Max | CV (%) | Mean | Min | Max | ||

| RL | Control | 443.81 | 346.40 | 517.00 | 6.9 | −33 | −7 | −61 |

| Drought | 296.12 | 112.40 | 448.00 | 27.6 | ||||

| SL | Control | 445.17 | 307.60 | 571.00 | 15.4 | −34 | −21 | −46 |

| Drought | 292.50 | 155.00 | 421.40 | 15.4 | ||||

| RFW | Control | 16.01 | 7.83 | 33.48 | 26.5 | −53 | −37 | −68 |

| Drought | 7.61 | 4.66 | 13.60 | 25.6 | ||||

| SFW | Control | 15.98 | 7.24 | 29.24 | 28.8 | −66 | −47 | −76 |

| Drought | 5.37 | 2.33 | 10.88 | 30.7 | ||||

| RDM | Control | 8.91 | 5.12 | 13.79 | 16.3 | 120 | 70 | 165 |

| Drought | 19.47 | 12.97 | 27.99 | 16.3 | ||||

| SDM | Control | 8.83 | 7.09 | 10.39 | 7.5 | 63 | 40 | 97 |

| Drought | 14.34 | 10.34 | 19.37 | 14.5 | ||||

| RL/SL | Control | 1.02 | 0.76 | 1.50 | 15.3 | 0 | −37 | 42 |

| Drought | 1.01 | 0.42 | 1.54 | 23.7 | ||||

| RFW/SFW | Control | 1.02 | 0.73 | 1.42 | 16.4 | 42 | 10 | 93 |

| Drought | 1.45 | 0.96 | 2.03 | 15.3 | ||||

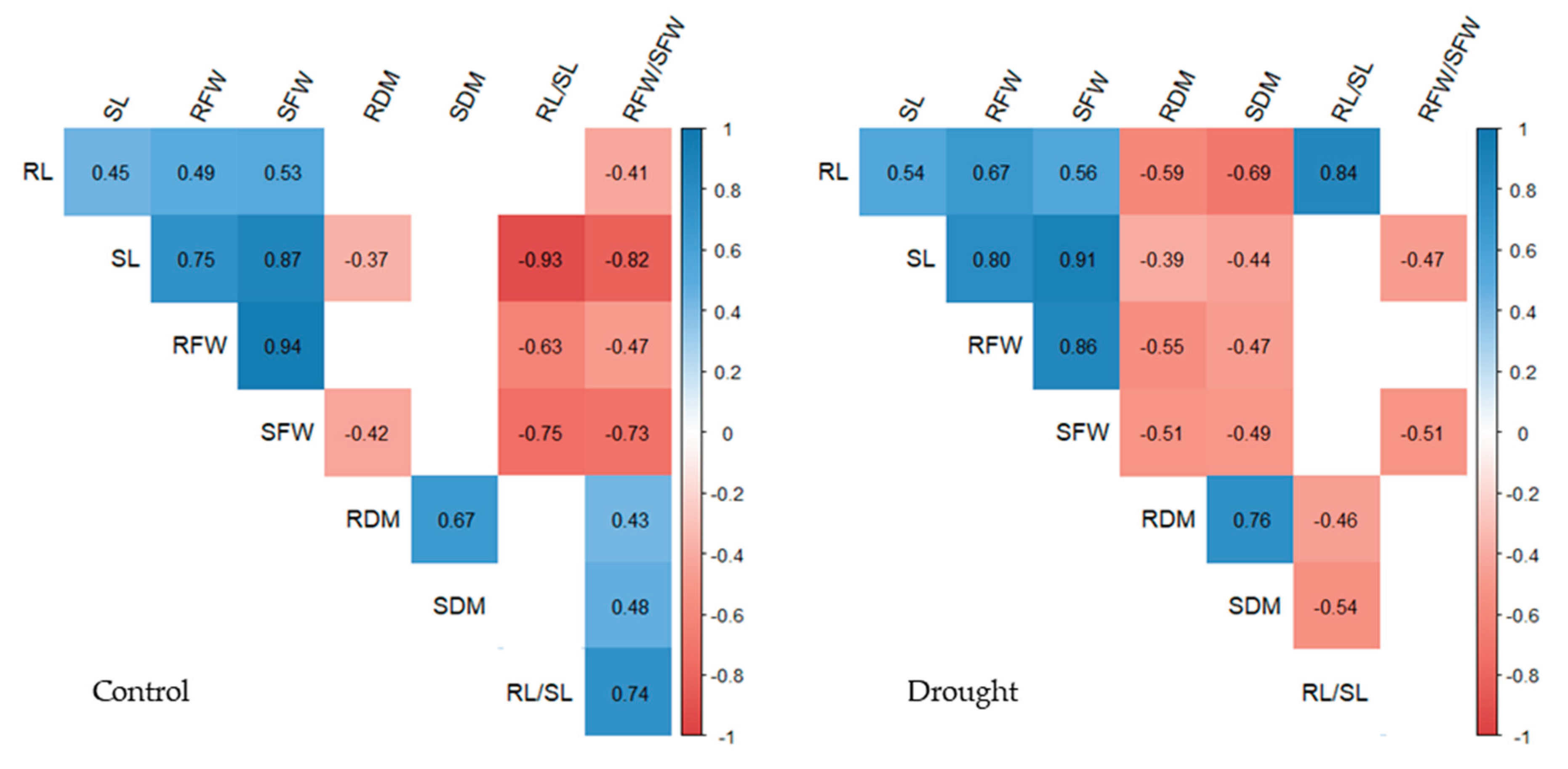

3.3. Correlation Between Traits

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deribe, H. Review on Effects of Drought Stress on Maize Growth, Yield and Its Management Strategies, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2025, 56:1, 123–143. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Olesen, J. E.; Wang, M.; Kersebaum, K.-C.; H. Chen, H.; Baby, S.; Öztürk, I.; Chen. F. Adapting maize production to drought in the northeast farming region of China. The European Journal of Agronomy 2016, 77, 47–58. [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 15th of September 2025).

- Maazou, A.-R.S.; Tu, J.L.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Z.Z. Breeding for Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.). American Journal of Plant Sciences 2016, 7, 1858–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Jie, H.; Ali, B.; He, P.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Y.; Xing, H.; Qari, S.H.; Hassan, M.U.; Hamid, M.R.; et al. Breeding Drought-Tolerant Maize (Zea mays) Using Molecular Breeding Tools: Recent Advancements and Future Prospective. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, W.; Siegert, K. Water Harvesting: A Manual for the Design and Construction of Water Harvesting Schemes for Plant Production. FAO, Rim, Italy, 1991.

- Sah, R.P.; Chakraborty, M. : Prasad, K.; Pandit, M.; Tudu, V.K.; Chakravarty, M.K.; Narayan, S.C.; Rana, M.; Moharana, D. Impact of water deficit stress in maize: Phenology and yield components. Sci. Rep. 2022, 10, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwale, R.O.; Awosanmi, F.E.; Ogunniyi, O.; Fadoju, A.O. Determinants of drought tolerance at seedling stage in early and extra-early maize hybrids. Maydica 2017, 62, M4. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, W.B.; Edmeades, G.O.; Barker, T.C. Molecular and physiological approaches to maize improvement for drought resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Denmead, O. T.; Shaw, R. H. The effects of soil moisture stress at different stages of growth on the development and yield of corn. Agron. J. 1960, 52, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmeades, G.O.; Lafitte, H.R.; Bolanos, J.; Chapman, S.C.; Bänziger, M.; Deutsch, J.A. Developing maize that tolerates drought or low nitrogen conditions. In: Stress tolerance breeding: maize that resists insects, drought, low nitrogen, and acid soils. Edmeades, G.O., Deutsch, J.A., Eds.; 1994, pp. 21–84.

- Duvick, D.N. What is yield? In: Developing drought and low-N tolerant maize. Edmeades, G.O., Bänziger, M., Mickelson, H.R., Peña-Valdivia, C.B., Eds., CIMMYT: El Batan, Mexico, 1997, pp. 332–335.

- Duvick, D. N.; Cassman, K. G. Post-green revolution trends in yield potential of temperate maize in the North-Central United States, Crop Sci, 1999, 39, 1622–1630.

- Adewale, S.A.; Akinwale, R.O.; Fakorede, M.A.B.; Badu-Apraku, B. Genetic analysis of drought-adaptive traits at seedling stage in early-maturing maize inbred lines and field performance under stress conditions. Euphytica. [CrossRef]

- Meeks, M.; Murray, S.C.; Hague, S.; Hays, D. Measuring Maize Seedling Drought Response in Search of Tolerant Germplasm. Agronomy 2013, 3, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemel, A.; Álvarez-Iglesias, L.; Pedrol, N.; López-Malvar, A.; Ordás, A.; Revila, P. Identification of drought tolerant populations at multi-stage growth phases in temperate maize germplasm. Euphytica 2018, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustamu, N.E.; Tampubolon, K.; Alridiwirsah, A.; Basyuni, M. Preliminary Identification of Local Maize Under Drought Stress By PEG-6000. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 69, 01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustamu, N.E.; Tampubolon, K.; Alridiwirsah, A.; Basyuni, M. , AL-Taey D. K.A., Janabi, H.J.K., Mehdizadeh, M. Drought stress induced by polyethylene glycol (PEG) in local maize at the early seedling stage, Heliyon 2023, 9, e20209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.; El-Shazly, H.H.; Tarawneh, R.A.; Börner, A. Screening for Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.) Germplasm Using Germination and Seedling Traits under Simulated Drought Conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, M.M.; Atit Parajuli, A.; Sah, B.P.; Shrestha, J.; Sakha, B.M.; Koirala, K.B.; Dhital, S.P. (2019). Effect of PEG Induced Drought Stress on Germination and Seedling Traits of Maize (Zea mays L.) Lines. Turkish Journal of Agricultural and Natural Sciences 2019, 6, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ul Islam, N.; Ali, G.; Dar, Z.A.; Maqbool, S.; Khulbe, R.K.; Bhat, A. (2019). Effect of PEG Induced Drought Stress on Maize (Zea mays L.) Inbreds. Plant Archives 2019, 19, 1677–1681. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, M.; da Silva Oliveira, C.E.; Steiner, F.; Zuffo, A.M.; Zoz, T.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Silva Mennes, V.; Mello, B.F.F.R.; Cabral, R.C.; Menis, F.T. Drought Stresses on Seed Germination and Early Growth of Maize and Sorghum. Journal of Agricultural Science 2019, 11, 310–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, L.; de la Roza-Delgado, B.; Reigosa, M.J.; Revilla, P.; Pedrol, N. A simple, fast and accurate screening method to estimate maize (Zea mays L.) tolerance to drought at early stages. Maydica 2017, 62, M34. [Google Scholar]

- Partheeban, C.; Chandrasekhar, C.N.; Jeyakumar, P. : Ravikesavan, R. ; Gnanam, R. Effect of PEG Induced Drought Stress on Seed Germination and Seedling Characters of Maize (Zea mays L.) Genotypes, Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodarahmpour, Z. Effect of drought stress induced by polyethylene glycol (PEG) on germination indices in corn (Zea mays L.) hybrids. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 18222–18227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatnezhad, M.; Gholamin, R.; Jamaati-e-Somarin, S.; Zabihi-e-Mahmoodabad, R. Effects of PEG Stress on Corn Cultivars (Zea mays L.) at Germination Stage. World Applied Sciences Journal 2010, 11, 504–506. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.J.; Fan, J.J.; Ruan, Y.Y. Application of polyethylene glycol in the study of plant osmotic stress physiology. Plant Physiol. Commun. 2004, 40, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Z.; Wang, L.; Duan, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y. Effects of PEG simulated drought stress on seed germination of Abutilon theophrasti medicus. Seed 2022, 41, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Hou, X.; Dong, S. Current views of drought research: experimental methods, adaptation mechanisms and regulatory strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1371895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramova, V.; Nagel, K.A.; AbdElgawad, H.; Bustos, D.; DuPlessis, M.; Fiorani, F.; Beemster, G.T.S. Screening for drought tolerance of maize hybrids by multi-scale analysis of root and shoot traits at the seedling stage. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2453–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, B.E. Evaluation of the water potentials of solutions of polyethylene glycol 8000. Plant Physiology 1983, 72, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute, Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) User’s Guide Version 9.4. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 2016.

- Hallauer, A.R.; Carena, M.J.; Filho, J.B.M. Quantitative Genetics in Maize Breeding; Springer, New York, USA, 2010.

- R Core Team _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_, version 4.4.2., R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024 https://www.R-project.

- Soetewey, A. Correlation coefficient and correlation test in R, Stats and R. Available online: https://statsandr.com/blog/correlation-coefficient-and-correlation-test-in-r/ (accessed on 16th of September 2025).

- Sharp, R.E.; Davies, W.J. Regulation of growth and development of plants growing with a restricted supply of water. In Plants under Stress. Biochemistry, Physiology and Ecology and Their Application to Plant Improvement, Jones, H.G., Flowers, T.J., Jones, M.B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1989.

- Ribaut, J.M.; Betran, J.; Monneveux, P.; Setter, T. Drought Tolerance in Maize. In Handbook of Maize: Its Biology, Bennetzen, J., Hake, S., Eds., Springer, New York, USA, 2009; pp. 311–344. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. H.; Ahsan, M.; Naveed, M.; Sadaqat, H. A.; Javed, I. Genetics of drought tolerance at seedling and maturity stages in Zea mays L. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2016, 14, e0705. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2016, 14, e0705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; K. J., Sa.; Lee, J.K. Drought tolerance screening of maize inbred lines at an early growth stage. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology 2019, 7, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).