1. Introduction

Over the more than 2,000 years since the Qin Dynasty, China’s elite class has long been alert to the periodic rise and fall characterized by “its ascent being vigorous and its downfall abrupt” [

1], and has also recognized the principle that “the people are like water, and the ruler is like a boat; water can carry the boat, but it can also capsize it” [

2]. However, their reflections were largely confined to aspects such as governance capacity, personal moral character, or the “Mandate of Heaven,” remaining at a level of “treating the head when the head aches and the foot when the foot hurts” (i.e., addressing symptoms rather than root causes). By the end of the imperial system, no one had publicly advocated breaking free from this cyclical trap through checks and balances on power. Only during the reign of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (Li Shimin) was there a regulation that imperial edicts required review by the Menxia Sheng (Chancellery) before being issued [

3]; yet this was merely a tentative attempt that ultimately came to nothing. Furthermore, no one dared to publicly question the fairness or legitimacy of treating public power as private property, abusing public power for private gain, or transforming the state into a family estate. It seems that the Chinese people lost the systematic ability of self-reflection and self-correction in terms of political models and social injustice.

On the other side of the globe, China’s unique cyclical phenomenon has attracted the attention of some insightful scholars. More than 250 years ago, Montesquieu, the French Enlightenment thinker, had already observed that there was a pattern in the dynastic changes in Chinese history and described the cycle of Chinese dynasties [4a]. Later, Hegel also stated bluntly: “In essence, China has no history; it is merely the repeated collapse of monarchs, from which no progress can emerge.” Although the Chinese people learned about magnets and printing technology quite early, they did not know how to make proper use of them. For instance, in terms of printing, they still carved characters on wooden blocks for printing instead of using movable type. Despite their proficiency in calculation, they had not yet grasped the highest form of the discipline of mathematics. They observed and recorded some solar and lunar eclipses, but failed to develop the science of astronomy. They treated European telescopes as decorative objects rather than understanding how to utilize them [

5], and so on.

However, under the cover of the “glorifying merits and concealing flaws” political narratives or packaged ideological discourses of patrimonial bureaucratic states, coupled with the interference of complex factors such as society, economy, culture, and technology, many outsiders find it difficult to discern the essence of China’s historical cyclical law. Even those immersed in this context are easily misled—even top Sinologists like John K. Fairbank were not exempt [

6].

Since the late Qing Dynasty, Chinese historians have begun to attach importance to this cyclical phenomenon [

7,

8]. In the 1940s, the “Loess Cave Dialogue” between Huang Yanpei and Mao Zedong in Yan’an, which focused on the Historical Cycle Rate (HCR), gained widespread attention [

9]. In the 1950s, before the “Cultural Revolution,” many people irrationally believed that China had escaped the trap of the “historical cyclical law.” However, after experiencing the heavy disaster of the “Cultural Revolution,” a considerable number of people rediscovered the “cyclical law” [

10].

In recent decades, many interdisciplinary scholars, both Chinese and foreign, have attempted to explain this phenomenon using variables such as climate change, natural disasters, external conflicts, population growth effects, and resource shortages [

11,

12], or methods like game theory [

13] and mathematical models [

14]. While these studies contain many insightful observations, most focus on certain superficial manifestations of the cycle. Moreover, being able to explain the cyclical phenomenon does not equate to uncovering its true internal driving forces.

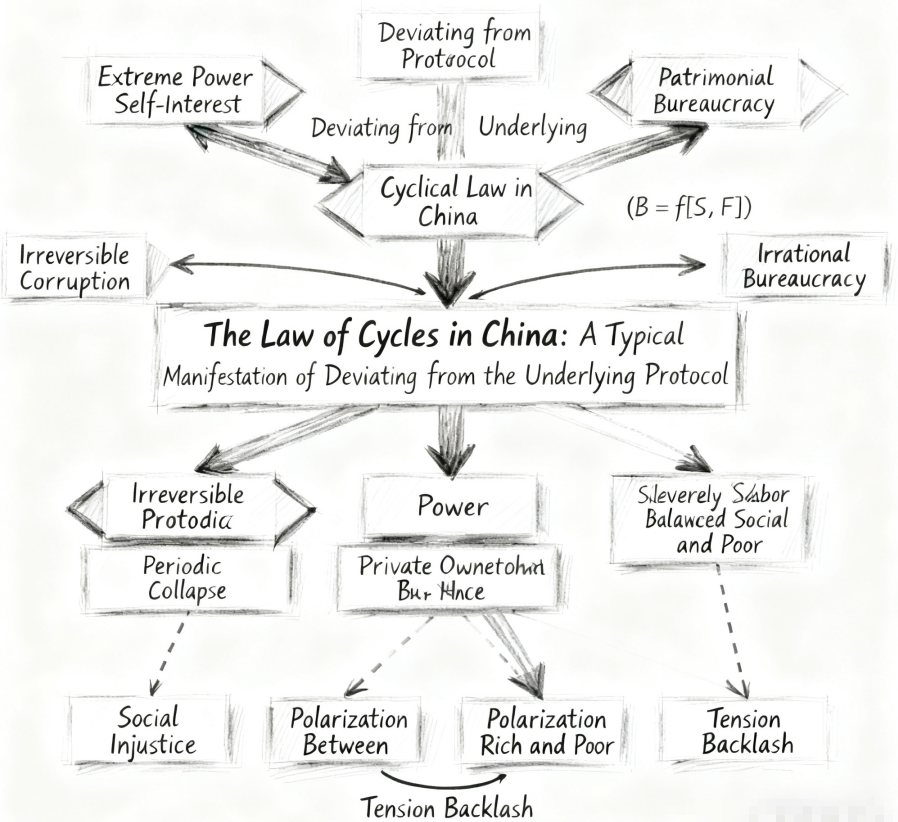

Based on summarizing decades of interdisciplinary research findings (spanning behavioral science, neuroscience, integrative psychological science, evolution, anthropology, history, etc.), Raphaeol Xue proposed the “Underlying Protocols (UP)” theory that transcends individual will and class positions [

15]. This theory reveals that in the course of human evolution, a psychological and behavioral tendency has been formed—one that balances self-interest and fairness, and possesses tension and elasticity, much like an “ancient scale” in the human mind (i.e., B = f[S, F]). Additionally, the theory introduces “power” as a special variable, providing a remarkably simple identification tool. This tool helps people recognize the biases in certain social practices or their governance theories, avoiding the repetition of humanitarian disasters such as those caused by Soviet-style socialism or fascism in the 20th century. Simultaneously, it offers a more concise tool for solving the long-perplexing “historical cyclical law.” When discussing the Underlying Protocols theory, China was used as an example to compare the survival capacity of states [

15], but no in-depth elaboration was provided.

2. Methodology

This study adopts an interdisciplinary mixed research method. It is neither a purely empirical research nor a purely philosophical speculation; instead, it is based on the theoretical framework of “Underlying Protocols (UP)”. Through the integration of interdisciplinary theories and verification with historical literature, this study achieves the combination of “theoretical depth” and “empirical rigor”. It transcends the previous explanatory focus on superficial factors such as “climate, population, environment, resources, and governance performance”, and ultimately provides an analytical tool with both historical explanatory power and practical warning significance for “the cyclical risks of irrational bureaucratic states”.

3. Results

In fact, the Historical Cycle Law of China is merely a typical manifestation of deviating from the Underlying Protocol (where B = f[S, F]); it is neither mysterious nor an exception. For dynasties under the Patrimonial Bureaucracy system, emperors themselves became the “greatest betrayers” of the fairness norms preserved through evolution [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Although the practices of the bureaucratic system led by emperors differed from those of Soviet-style socialist states—never causing fragmented damage to the people’s needs for self-interest and fairness—they created severe social injustice. Moreover, such systems institutionalized and organizationalized the privatization of power and the transformation of the state into a family estate, turning power (which should serve the public interest) into an exploitative tool for private gain. The emperor’s power was barely constrained, severely distorting the moral norms and reciprocal cooperation formed in the evolutionary era, weakening the possibility of preventing the “spread of betrayal,” and undermining the repair mechanism for individuals to refuse cooperation. This can be succinctly expressed by the function: B_Ps = f[S_Ps, F_Ps].

If, as Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (Li Shimin) and his officials analogized, a Patrimonial Bureaucracy dynasty is compared to a boat and the people to water, then the extreme power self-interest (PS) that severely distorts social interaction relations means the boat is inherently flawed with serious structural problems from the start—much like the legendary RMS Titanic that set sail with inherent defects [

24], destined to be swallowed by the sea. The timing of its capsizing may be accelerated or delayed by variables such as governance performance (level of corruption) and the status of survival resources, but these factors cannot and have never altered the fate of Patrimonial Bureaucracy states being counterattacked by the “Underlying Protocol (B = f[S, F])”, ultimately leading inevitably to the “tragedy of the commons” [

25,

26].

To date, discussions on China’s cyclical law have mostly remained focused on describing phenomena and researching various variables [

11,

12]. Regarding the question “Is there an irresistible objective law behind the cyclical phenomenon?”, academic opinions differ. For instance, scholars like John K. Fairbank once argued that China’s political model was merely a “superficial” phenomenon superimposed on more fundamental developments in technology, economy, society, and culture. Nevertheless, they also acknowledged that within each Chinese dynasty, matters such as fiscal conditions, administrative efficiency, and power relations with “barbarians” followed surprisingly similar trajectories. They further noted that the concept of China’s “dynastic cycle” might have greater universal applicability than the “cultural cycles” proposed by Western historians such as Oswald Spengler and Arnold J. Toynbee [

27]. While this assertion remains open to debate, it implicitly aligns with the conclusion that the “Underlying Protocol” is universally applicable: human historical evolution may seem disorderly and chaotic, but all manifestations share similarities based on the “Underlying Protocol” formed in the evolutionary era. Cultural differences are largely comprehensive reflections of how humans adapt to natural and social environments.

4. The Puzzling “Golden Ages”

Regarding the universal pattern of “cycles of order and chaos without genuine revolution” in Chinese history, Xia Zengyou, a historian of the late Qing Dynasty and early Republican period, provided a general description of the Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties: A peaceful golden age would inevitably emerge within 40 to 50 years after large-scale revolutions and wars; and the prosperity of the state would last for approximately a century starting from that golden age [

7]. His description has been accepted or restated by some scholars [

8].

The renowned “golden ages” (“times of governance” or “periods of revival”) in history were all eras of unified ultra-stability. Before discussing these “golden ages,” we first briefly explain two related topics—both, like the “golden ages” themselves, are linked to the “state-as-family-estate” system.

First, for an emperor (a mortal being), a patrimonial bureaucratic state was like a private company that he monopolized without any capital investment. How strong must this “incentive” have been for him? After the completion of the new Weiyang Palace, Liu Bang—the first Chinese emperor from a commoner background—hosted a feast for feudal lords and ministers. During the feast, he held a jade wine vessel and toasted his father (the Supreme Emperor), asking: “Father, you always thought I was good for nothing, unable to manage property, and not as diligent or capable as my second brother Liu Zhong (Liu Xi). Now, comparing the family estate I have built to his, whose is larger?” [

28] Liu Bang’s complacency is evident in his words. However, incentives are a double-edged sword: sound incentives can stimulate potential and drive progress, while excessive, unbalanced incentives are more like a “temptation”—one that tests and often overcomes integrity and moral conduct in human nature. Such incentives not only lead to ethical failures but may also systematically select and encourage individuals with moral flaws, ultimately poisoning the culture of the entire organization [

29]. From this perspective, it becomes easier to understand the terrifying ways in which emperors of all dynasties treated their subjects (discussed below), as well as some seemingly abnormal phenomena in Chinese history: for example, the “killing of rabbits and boiling of hounds” (a metaphor for eliminating loyal subordinates once their usefulness ends), which reflects the coldness of the monarch-subject relationship; “lingchi” (commonly known as “death by a thousand cuts”), an extreme torture to intimidate the people; “zhu lian” (collective punishment of relatives) and “shi wu lian zuo” (collective responsibility of neighbors), which forced members of society to spy on one another; the criminalization of “tuo ji” (severing one’s household registration), which controlled personal freedom and solidified social strata [

30]; the “burning of books and burying of scholars” in the Qin Dynasty to the “literary inquisitions” of the Ming and Qing dynasties; the “monarch as the master of ministers” (a core Confucian norm equating political relations to father-son blood ties); the “three obediences and four virtues” (Confucian norms confining women) and the custom of foot-binding (valuing “three-inch golden lilies” as a standard of beauty), among others.

When the state became the royal family’s estate, emperors should have “strived for excellence without needing prodding” in managing it. In particular, founding emperors of all dynasties invariably “dedicated themselves to good governance,” often learning lessons from the decline and fall of previous dynasties to constantly patch the “loopholes” of the patrimonial bureaucracy. For instance: Liu Bang, Emperor Gaozu of the Han Dynasty, learned from the downfall of the Qin Dynasty, adopted a policy of “governing by non-interference,” and enfeoffed members of the Liu clan as feudal lords to serve as vassal guards; during the Sui and Tang dynasties, to weaken the constraints of powerful aristocratic families, the imperial examination system was established and promoted; Zhao Kuangyin, Emperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty, implemented a policy of “valuing civil officials over military officers” to prevent military generals from imitating his own “usurpation of power by wearing the yellow robe”; Zhu Yuanzhang, Emperor Taizu of the Ming Dynasty, issued “iron certificates” (certificates of immunity) and abolished the position of prime minister to eliminate political interference by imperial in-laws and powerful ministers. Through such measures, personal autocracy and the patrimonial bureaucracy were continuously consolidated, gradually forming an extremely sophisticated bureaucratic management system and a seemingly “ultra-stable” institutional structure. This “ultra-stable” patrimonial bureaucracy possessed the authoritarian advantage of “concentrating power to accomplish great things.” Through the prefecture-county system, bureaucratic apparatus, and cultural integration (e.g., unified writing systems and standardized axle widths), it could achieve efficient governance in the short term and concentrate resources to address crises (such as flood control and border defense). This was the foundation for creating the “vigorously ascending” golden ages, but it was also the cause of their “abruptly falling” decline (discussed separately below).

Second, tempted by the “state as family property” system, the lesson that “if you do not annex others, you will be annexed by others” gradually took shape starting from the Warring States Period. Driven by considerations such as “How can one tolerate others sleeping soundly beside one’s couch?” (a classical Chinese idiom signifying intolerance of potential threats in one’s immediate sphere of influence), emperors of the Qin-system era who sought to make achievements often had the urge to unify the entire Yangtze-Huaihe region or the desire to recover lost territories. Examples include Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty’s expansion into the Hexi Corridor and the Western Regions; the successive campaigns launched by Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty (Yang Guang) and Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (Li Shimin) to recover Liaodong or gain control over the Korean Peninsula; the attempts by Emperor Taizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (Zhao Guangyi) and some of his subsequent successors to reclaim the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan-Yun; and the recovery of Taiwan and the Penghu Islands during the Qing Dynasty.

After the Qin Dynasty, there were approximately 32 so-called “golden ages” (“times of governance” or “periods of revival”) recorded in historical records—including controversial or short-lived ones. They are listed as follows:

The Rule of Wen and Jing (Western Han Dynasty, Emperors Wen [Liu Heng] and Jing [Liu Qi] of Han);

The Golden Age of Emperor Wu (Western Han Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han [Liu Che]);

The Zhaoxuan Revival (Western Han Dynasty, Emperors Zhao [Liu Fuling] and Xuan [Liu Xun] of Han);

The Guangwu Revival (Eastern Han Dynasty, Emperor Guangwu of Han [Liu Xiu]);

The Rule of Ming and Zhang (Eastern Han Dynasty, Emperors Ming [Liu Zhuang] and Zhang [Liu Da] of Han);

The Rule of Taikang (Western Jin Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Jin [Sima Yan]);

The Rule of Yuanjia (Southern Song Dynasty [Liu Song], Emperor Wen of Song [Liu Yilong]);

The Rule of Yongming (Southern Qi Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Qi [Xiao Ze]);

The Rule of Tianjian (Southern Liang Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Liang [Xiao Yan]);

The Xiaowen Revival (Northern Wei Dynasty, Emperor Xiaowen of Wei [Yuan Hong], originally surnamed Tuoba);

The Rule of Kaihuang (Sui Dynasty, Emperor Wen of Sui [Yang Jian]);

The Rule of Zhenguan (Tang Dynasty, Emperor Taizong of Tang [Li Shimin]);

The Rule of Yonghui (Tang Dynasty, Emperor Gaozong of Tang [Li Zhi]);

The Rule of Wu Zhou (also called “Pioneering the Kaiyuan Era,” Empress Wu Zetian);

The Kaiyuan Golden Age (Tang Dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang [Li Longji]);

The Yuanhe Revival (Tang Dynasty, Emperor Xianzong of Tang [Li Chun]);

The Rule of Dazhong (Tang Dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang [Li Chen]);

The Rule of Changxing (Later Tang Dynasty, Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang [Li Siyuan]);

The Rule of Xianping (Northern Song Dynasty, Emperor Zhenzong of Song [Zhao Heng]);

The Rule of Renzong (Northern Song Dynasty, Emperor Renzong of Song [Zhao Zhen]);

The Rule of Qianchun (Southern Song Dynasty, Emperor Xiaozong of Song [Zhao Shen]);

The Jingsheng Revival (Liao Dynasty, Emperors Jingzong [Yelu Xian] and Shengzong [Yelu Longxu] of Liao);

The Rule of Dading (Jin Dynasty, Emperor Shizong of Jin [Wanyan Yong]);

The Rule of Mingchang (Jin Dynasty, Emperor Zhangzong of Jin [Wanyan Jing]);

The Rule of Hongwu (Ming Dynasty, Emperor Taizu of Ming [Zhu Yuanzhang]);

The Yongle Golden Age (Ming Dynasty, Emperor Chengzu of Ming [Zhu Di]);

The Rule of Ren and Xuan (Ming Dynasty, Emperors Renzong [Zhu Gaochi] and Xuanzong [Zhu Zhanji] of Ming);

The Hongzhi Revival (Ming Dynasty, Emperor Xiaozong of Ming [Zhu Youcheng]);

The Rule of Longqing (Ming Dynasty, Emperor Muzong of Ming [Zhu Zaiji]);

The Wanli Revival (Ming Dynasty, Emperor Shenzong of Ming [Zhu Yijun]);

The Kang-Qian Golden Age (Qing Dynasty, Emperors Kangxi [Aisin Gioro Xuanye], Yongzheng [Aisin Gioro Yinzhen], and Qianlong [Aisin Gioro Hongli] of Qing);

The Tongguang Revival (Qing Dynasty, Tongzhi and Guangxu periods; the de facto supreme ruler was Empress Dowager Cixi).

Compared with the approximately 330 emperors in history (including those of divided periods) [

31], the number of emperors honored with the reputation of “golden age,” “time of governance,” or “period of revival” is not large. Moreover, as Xia Zengyou noted: In the early days of a dynasty, after large-scale upheavals, the population decreased significantly, and the materials produced by nature (such as grain and other products) were more than sufficient to support the remaining population. Furthermore, most of those with ambition and the courage to incite upheaval had died in previous wars; the survivors had no higher aspirations other than being tired of war and wanting to survive. This is the fundamental reason for the formation of a peaceful golden age—it is interrelated and mutually influential with the output of land, and has nothing to do with the personal abilities of the monarch or his ministers. If the reigning monarch and his ministers could also practice “non-interference” and refrain from arbitrarily disrupting the people’s production and livelihoods, the effect of the peaceful golden age would be even more pronounced [

7].

Although Chinese and foreign historians have different understandings of “golden ages,” they almost all acknowledge the phenomenon itself. A widely accepted view among scholars is: After the upheavals at the end of the previous dynasty, the population sharply declined and large areas of land were left uncultivated. When a new dynasty was established, most founding emperors came from ordinary backgrounds and were familiar with the hardships of the people and the true state of society. They were highly gifted and knew how to exercise self-discipline and treat others, so problems were naturally less likely to arise [

8,

27]. Among these factors, the most widely recognized is the sharp decline in population.

Research by demographers also confirms that the population during “golden ages” was far smaller than that at the end of a dynasty. Below are four groups of population data comparisons: between the late period of the previous dynasty and the period before or during the golden age of the subsequent dynasty:

Late Qin Dynasty (before the uprisings led by Chen Sheng and Wu Guang): After the Qin Dynasty conquered the six states, the national population was nearly 40 million;

Western Han’s Rule of Wen and Jing: In the early Western Han Dynasty, the national population was approximately 14 to 18 million.

Late Western Han Dynasty (before the peasant uprisings led by the Green Forest and Red Eyebrow armies): In the second year of Yuanshi of Emperor Ping of Han (2 CE), the national population was approximately 59.59 million;

Eastern Han’s Guangwu Revival: When Emperor Guangwu of Han (Liu Xiu) died, the national population was approximately 21 million.

Late Eastern Han Dynasty (before the Yellow Turban peasant uprisings): In the second year of Yongshou of Emperor Huan of Han (156 CE), the national population was approximately 56.48 million;

Western Jin’s Rule of Taikang: In the first year of Taikang of Emperor Wu of Jin (280 CE), the national population was approximately 16.16 million.

Late Sui Dynasty (before the peasant uprisings): In the fifth year of Daye of Emperor Yang of Sui (609 CE), the national population was approximately 46.02 million;

Tang Dynasty’s Rule of Zhenguan: In the early Zhenguan period of the Tang Dynasty, the national population was approximately 12.35 million.

It can be seen from the comparisons that the renowned Rule of Wen and Jing, Guangwu Revival, Rule of Zhenguan, and Rule of Taikang all emerged against the background of a sharp population decline. In such contexts, per capita arable land increased, the people’s living resources improved, and after a period of “ten years of cultivation and ten years of education” (i.e., long-term recovery and development), the economy achieved natural restorative growth [

32].

In addition to the sharp population decline and abandoned farmland, the patrimonial bureaucratic state, while exploiting the people, also needed to maintain the survival of the exploited (to ensure sustainable exploitation). It even took the initiative to introduce policies such as “light corvée and low taxes” and “restoring production and nourishing the people,” or suppressed the annexation of land by local tyrants. For example, in the early Western Han Dynasty, the people had no savings at all—even the horses pulling the emperor’s carriage could not be matched with four horses of the same color, and some generals and prime ministers had to ride ox carts. In response, the emperor simplified laws, reduced prohibitions, and lowered land taxes; at the same time, he calculated the salaries of officials and estimated government expenditures to determine the amount of taxes levied on the people [33a]. Therefore, the royal family exhibited a “duality” in its attitude toward the people’s simple reproduction [34a]: it did not deprive the people of their self-interested needs for survival and reproduction. Moreover, humans have the strongest desire to satisfy their basic physiological and safety needs [

35]—this was the fundamental social-psychological driver for the creation of “golden ages.” As long as social stability was maintained and the people’s lives were not excessively disrupted, the economy could potentially grow driven by self-interest; at the very least, farmers could meet their needs for self-sufficiency.

5. Toward Irreversible Corruption

In a state under the patrimonial bureaucracy system, two contradictory dynamics coexist. On one hand, emperors driven by power self-interest always seek to dominate all matters, situations, or relationships, craving “unified authority”—an instinct shared by emperors across all ethnicities [

36]. On the other hand, as Francis Fukuyama argued, “governance of a large state like China must involve the delegation of power” [

37]. Within this patrimonial bureaucratic context, the emperor serves as both the originator of power and its supreme agent. The “princes, nobles, generals, and ministers” are all agents authorized by the emperor—essentially household retainers tasked with “guarding the estate.” Like ordinary people, they lack basic guarantees of personal freedom and property, let alone genuine dignity. The adage “if the ruler demands a minister’s death, the minister must die” encapsulates this reality. In a rule-by-man system where laws are as flexible as rubber bands (for example, the imperial secret police in the Ming Dynasty could arrest officials bypassing judicial procedures), the emperor or those holding imperial power (such as Huo Guang, a powerful minister from the imperial in-laws; Wei Zhongxian, a eunuch; and Empress Dowager Cixi) stood at the top of the power hierarchy. Their words were “edicts of gold,” allowing them to arbitrarily manipulate subordinates, and they could strip lower-ranking officials of their positions or even their lives on “unsubstantiated charges.” Examples include the cases of Yue Fei in the Southern Song Dynasty and Yuan Chonghuan in the late Ming Dynasty. Living in an environment where “serving the emperor is like accompanying a tiger,” officials sometimes faced more terror than commoners. Beyond daily surveillance by disciplinary or secret service agencies—such as the Censorate, the Court of Imperial Censors, the Six Boards’ Remonstrators, and the Embroidered Uniform Guard—they also feared accusations and informants. A notable example is the “bronze letter box system” in Empress Wu Zetian’s reign, which encouraged mutual denunciation [38a]. Since the Qin and Han dynasties, there have been countless cases of “casting aside the bow once the birds are gone, and boiling the hounds once the hares are caught” (eliminating useful subordinates after their purpose is served). When officials offended the emperor or lost in factional struggles, their family members (paternal, maternal, and spousal relatives), disciples, and old acquaintances could be implicated. For instance, the cases of Hu Weiyong and Lan Yu in the Ming Dynasty involved tens of thousands of people; even Li Shanchang, a meritorious official holding an “iron certificate of immunity from the death penalty,” was unable to save himself [38b]. In the Qing Dynasty, He Shen was condemned to death by Emperor Jiaqing (Yongyan) on twenty major charges, and his family property was confiscated—with legal procedures reduced to a mere formality.

Within the vertical power chain, “a one-rank higher official can crush others.” Superiors could arbitrarily “make things difficult” for subordinates, and even humiliate them through corporal punishment such as flogging [

39]. Therefore, in the context of deviating from the Underlying Protocol, the balance between self-interest and fairness is disrupted both between the bureaucratic system and the emperor, and between senior and junior members within the bureaucracy. This imbalance leads to divergent perceptions of state survival: the emperor, while exploiting the people, at least seeks to maintain their basic means of reproduction to avoid “driving the people to rebellion”; by contrast, officials tend to prioritize self-preservation and muddle through their duties.During the Hongwu reign (1368-1398) of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor who had been a beggar in his early years, had a profound understanding of the corruption and chaos in the late Yuan Dynasty. After establishing the Ming Dynasty, he took a series of measures: on the one hand, he built a large standing army and implemented strict autocratic policies in politics, ideology, and culture; on the other hand, he cracked down heavily on powerful local clans, fought against corruption and advocated integrity, streamlined the tax and corvée system, and pursued a policy of “restoring people’s livelihoods through non-interference”. Nevertheless, more than 190 peasant protests triggered by the tense relationship between officials and common people broke out during his reign [

40].

Furthermore, according to psychoanalytic theory, when people’s needs are unmet, they seek psychological defense mechanisms and compensation to maintain mental balance [

41,

42]. Beyond the open benefits (such as salaries and rewards) and honors (such as returning home in glory) bestowed by the royal family, corruption becomes a potential “psychological balance” option for officials to manipulate behind the scenes. Three specific psychological factors further drive bureaucrats toward irreversible corruption:

1. Irreversibility Determined by the Self-Worth Protection Principle in Interpersonal Psychology

Everyone tends to approach those who affirm their self-worth, typically accepting only those who like, recognize, and support them, while keeping distance from those who deny or belittle them. Even emperors are not immune to this instinct, engaging in “selective exposure”—and self-interest and flattery are “two grasshopper on a string” (inseparable). It is inevitable for emperors and officials to be “hunted” (curried favor with) by their subordinates. The patrimonial bureaucracy system prioritizes loyalty to imperial power and recognition of the private ownership of power, rather than focusing on professional competence in handling specific affairs (such as expertise in finance, military affairs, or law) [43a]. For example, Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (Zhao Ji) favored six officials who “lacked the ability to govern but excelled at flattery.” The monarch and his ministers colluded in selfish interests: Cai Jing and Wang Fu provided political support for his “rationalized extravagance”; Tong Guan and Gao Qiu helped him “fulfill his vanity” (through territorial expansion and entertainment); Zhu Mian and Li Yan assisted him in “plundering wealth.” Among them, Cai Jing—Emperor Huizong’s most trusted minister—used his outstanding political skills and precise understanding of the emperor’s needs to serve as prime minister four times, totaling nearly 20 years in office (almost spanning the entire reign of Emperor Huizong). This directly led to political corruption and extreme hardship for the people in the late Northern Song Dynasty [44a]. Another example is the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty: He Shen, due to his exceptional talent, keen insight into the emperor’s intentions, and willingness to cater to the emperor’s preferences, gained the favor of Emperor Qianlong (Hongli) and became an arrogant “second emperor.” He cultivated cliques, engaged in nepotism, and built a network of influence across the country. Despite the Qing Dynasty accounting for one-third of the world’s GDP during the Qianlong era, with a full treasury, submission from neighboring states, and prestige extending far and wide, the underlying corruption could not be concealed. The so-called “golden age” was in fact a “hungry golden age” marked by extreme wealth disparity [45a]—a turning point from the Qing Dynasty’s prosperity to decline.

2. Irreversibility Determined by the “Imitation Law” of “Subordinates Imitating Superiors” [

46]

Lower social strata and individuals always imitate higher ones. As the Chinese saying goes, “what the superior favors, the subordinates will pursue even more intensely” [

47]. A classic allusion illustrating this is “King Zhuang of Chu favored slender waists”: King Ling of Chu admired men with slender waists. Fearing that their own waistlines would grow too thick and cost them the king’s favor, ministers at the court dared not eat their fill, surviving on just one meal a day to control their weight. Each morning, when getting dressed, they would hold their breath, tighten their belts, and support themselves against the wall to stand up. By the following year, the faces of all civil and military officials in the court had turned sallow and gaunt [

48]. Driven by the need to avoid harm, seek benefits, and conform for safety, officials’ imitation of the emperor’s words and deeds resembles the relationship between a “copy” and an “original.” Without interference, once imitation begins, it spreads exponentially and rapidly [

46].

The price phenomenon of Moutai liquor is precisely such a corrupt manifestation of “following the lead from above” that has accumulated over time [

49]. A 500ml bottle of Kweichow Moutai Liquor with an alcohol content of 53%vol is composed of 98%-99% ethanol and water, while organic compounds—including acids, esters, alcohols, and aldehydes—that contribute to its aroma and taste account for merely 1%-2%. Its retail price rose from 350 yuan to approximately 3,000 yuan (Renminbi) between 2004 and 2020 [

50]. What is perplexing is that amid the highly competitive market of premium liquors, Kweichow Moutai has remained in short supply for years, with demand far outstripping availability. Why is this the case?Clues can be found in a series of corruption cases involving liquor: Kweichow Moutai possesses a distinctive “non-commodity” attribute—those who purchase it are unwilling to consume it due to reluctance to part with it, while those who consume it do not need to purchase it, as others cover the cost [

51,

52]. It is clear that the scarcity of Kweichow Moutai stems not only from the affluence of certain groups but, more importantly, from the effect of “following the lead from above”: the upper echelons of the officialdom favor this liquor, which drives lower-ranking officials in the officialdom to cater to this preference. In turn, this has fueled “face-conscious consumption” in official-business social interactions. Individuals seeking favors often have no choice but to “put on a bold front despite financial constraints,” forcing themselves to afford the liquor even when they have limited funds.As a consequence, the “Moutai Phenomenon” has become an eccentric oddity in China’s consumer market at the turn of the 21st century. The fundamental reason for this lies in China’s inheritance of the traditional irrational bureaucratic system (to be discussed in subsequent sections). In the context of “official-centeredness,” the officialdom harbors the “highest-quality” trendsetters in consumption.

3. Irreversibility Determined by the Emperor’s “Betrayal” of Evolutionarily Preserved Fairness Norms

Interdisciplinary research—including behavioral experiments, neuroscientific experiments, genetic experiments, as well as studies in evolution and anthropology [

15]—has shown that tension exists between the need for self-interest and the need for fairness [

53]. Unfair distribution driven by self-interest or betrayal of reciprocal cooperation (such as fraud or free-riding) undermines cooperation efficiency and may even lead to the breakdown of cooperation. If left unchecked, the spread of betrayal disrupts the stability of social cooperation systems [

20] and can even trigger the “tragedy of the commons” [

25,

26]. However, to prevent the collapse of social systems and maintain fair cooperation, humans have developed “altruistic punishment” and repair mechanisms for upholding fair cooperation during social interactions involving distribution and reciprocity [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. In a patrimonial bureaucratic society, however, the emperor and the “princes, nobles, generals, and ministers” who “guard his estate” become a group that betrays social fairness norms—inevitably triggering the “spread of betrayal.” Even if the state apparatus is turned into an instrument of violent suppression to maintain the rule of private ownership and abuse of public power, such unjust systems and behaviors cannot endure. The reason is that “self-interested punishment” cannot replace “altruistic punishment” for upholding fair cooperation; nor can it eliminate the psychological tension that transcends individual will and class positions—this tension is encoded in human genes. “Betrayal” inevitably begets more “betrayal”: the emperor’s betrayal of social fairness norms inevitably leads to the further spread of betrayal, including within the bureaucratic system. Driven by the “imitation law” of “subordinates imitating superiors,” this ultimately results in the unbridled proliferation of power self-interest. Naturally, this process is non-linear.

6. Toward Irreversible Collapse

- 1)

First, in a society under the patrimonial bureaucracy, the emperor himself is the “greatest betrayer” of fairness norms. Power ceases to be a tool for upholding social justice; instead, it replaces land and capital as a means of exploiting the people. Starting from Shang Yang’s Reforms in the Qin State (356–350 BCE), the imperial court formulated industrial policies of “prioritizing agriculture and suppressing commerce,” a neighborhood mutual surveillance system of “shi wu lian zuo” (collective responsibility of neighbors), a twenty-rank military merit system, and an incentive mechanism for the bureaucratic system centered on “rewarding only achievements (administrative and agricultural achievements)” [

59]—all designed to cater to the extreme self-interest of the power-holding class. Over the subsequent 2,100-odd years, the Han Dynasty inherited the Qin system, the Tang inherited the Sui system, and the Qing inherited the Ming system; the bureaucratic system became increasingly sophisticated. At the top of this hierarchy was imperial power, while the middle tier consisted of the “nine ranks and eighteen grades” official system characterized by power inequality [

60], which enabled the implementation of a pyramid-style supervision and management system over subjects across the country.

- 2)

This social interaction framework (institutional and organizational) based on the “state-as-family-estate” system not only distorts the symbiotic relationship between self-interest and fairness among all social strata—leading to confrontational imbalance between the power-holding class and the common people—but also severely distorts the damage mechanism and repair mechanism within Tension (T), as well as the manifestation of Elasticity (E) [

15]. Since the emperor himself is an imposer of unfairness and a betrayer of fairness norms, both variables of the damage mechanism within tension—Imposition of Unfairness (IU) and Defection and its Contagion (DC)—are intensified. Consequently, social phenomena such as “imposition of unfairness” (e.g., forced transactions) and/or “defection and its contagion” (e.g., lack of contractual integrity) inevitably become more prevalent. This reverses the evolutionarily preserved repair mechanism of Punishing Defection (PD): it not only undermines the legitimacy of the power-holding class in “punishing defection” (e.g., suppressing dissidents) but also weakens the willingness of the people to Resist Unfairness (RU) (e.g., reluctance to uphold justice) and engage in Helping Victims (HV) (e.g., reluctance to assist elderly people who fall). In other words, the role of all three variables of the repair mechanism in maintaining social balance is weakened by power self-interest. At the same time, the three variables of elasticity (which mitigates destructive forces)—Cooperative Strategy (CS), Collective Efficiency (CE), and Individual Contribution (IC)—are also suppressed by the unfairness caused by power self-interest. The evolutionarily formed Cooperative Strategy (CS) for preventing social collapse is distorted; instead, a “rat philosophy” of pursuing petty gains and prioritizing profit over morality [

61],”External Confucianism and internal Legalism” which means saying one thing and doing another[

62],the Luo Zhi Jing (The Classic of Framing), a text focused on framing political opponents and manipulating others with cunning schemes.[

63], and the “thick-skinned and black-hearted” doctrine of “thick face and black heart” [

64] (a Chinese theory advocating ruthless tactics for success) have become prevalent in officialdom and society. Beyond maintaining the basic order required for people’s livelihoods, the legitimacy of Collective Efficiency (CE) goals (e.g., building imperial mausoleums) is greatly diminished. The people lack the willingness to cede rights, so the government can only maintain a seemingly stable situation through coercion and instilling fear. Individual Contribution (IC) is suppressed by exploitative institutions, leading to a widespread lack of creativity among the people. As Hegel pointed out [

5], even with inventions such as the compass, papermaking, gunpowder, and printing, there was no collective will to transform them into productive forces. Under the interference of power self-interest, the functions representing the backlash of Underlying Protocol tension and the elasticity for alleviating tension can be expressed as follows:

Second, the existence of a patrimonial bureaucratic state and its exploitation of interests can only be sustained by violent power. Therefore, the national policy of “prioritizing agriculture and suppressing commerce” (literally “valuing agriculture and restraining the secondary”) formulated by Shang Yang’s Reforms for Qin-style dynasties was essentially an extra-economic measure based on “absolute control,” which did not conform to the laws of economic operation. The historian Liu Zehua has elaborated in detail on how the state and bureaucratic system, under the dominance of privileged politics, undermined the exchange of commodity values and the reproduction of the small-scale peasant economy.

On one hand, the patrimonial bureaucratic state used policies to discriminate against merchants and industrialists—groups with high mobility that were difficult to control. For example: after the unification of China by the Qin Dynasty, merchants were exiled to defend the borders; in the early Western Han Dynasty, merchants were prohibited from riding horses or carriages and wearing silk clothing, and heavy taxes were imposed to impoverish them; during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, the “gao min ling” (edict encouraging the reporting of hidden property) was implemented, along with state monopolies on salt and iron and the official management of handicrafts; during the reign of Emperor Ai of Han, merchants were forbidden from owning land or holding official positions, with legal penalties for violators [33b], and so on. The imperial court even directly intervened in the economy in the name of “jun shu ping zhun” (a policy claiming to “equalize transportation and stabilize prices” for fairness). During the reign of Liu Che (Emperor Wu of Han), the state monopolized the salt and iron trade through “official management”—not only competing for profits with merchants and industrialists but also directly “skimming profits” from the people’s daily necessities. This monopoly led to a sharp rise in the prices of salt and iron, resulting in tragic situations where farmers could not afford salt and had to eat food without it, and could not afford farming tools and had to weed by hand.

On the other hand, it has long been claimed that “suppressing commerce” was intended to “prioritize agriculture.” However, in practice, this policy did not promote the development of agricultural production; instead, it made agriculture rigid and inflexible, preventing it from moving beyond the level of simple reproduction. Nevertheless, the “static” small-scale peasant economy aligned with the interests of the patrimonial bureaucratic state. The emperor, relying on privatized power, collected land taxes based on farmland and forests, poll taxes based on population, and forced farmers to provide corvée labor and military service for the state-as-family-estate. The small-scale peasant economy was extremely fragile, as reflected in the saying: “If one man does not plow, someone will go hungry; if one woman does not weave, someone will suffer from cold” [33a]. The intensity of such exploitative exactions varied across periods: for instance, during the early Western Han Dynasty (the reigns of Emperors Wen and Jing) and the mid-to-late Western Han (the reigns of Emperors Zhao and Xuan), policies of “governing by non-interference” and “restoring people’s livelihoods” were adopted, taxes and corvée were relatively light, and farmers could generally maintain simple reproduction—allowing social economy to recover and develop. In contrast, during the reigns of Emperors Wu, Cheng, and Ai of Han, as well as the Xin Dynasty (founded by Wang Mang), taxes and corvée were extremely heavy. Particularly during the reigns of Emperor Wu and Wang Mang, ignorance of economic laws and excessive interference in economic activities led to widespread social crises, ultimately triggering social conflicts and the collapse of the dynasty. Rulers of Qin-style dynasties in China have always advocated “prioritizing agriculture,” but from the history of the Qin and Han dynasties, “prioritizing agriculture” at best only maintained simple reproduction; more often than not, it pushed simple reproduction into a desperate situation [34b].

By comparison, emperors with normal intelligence would give more consideration to the duality of “water can carry the boat, but it can also capsize it.” However, the officials serving the imperial family might not share this view. In fact, under the emperor’s demonstration of “betraying” fairness norms, “imposition of unfairness” and “defection and its contagion” spread within the bureaucratic system in various forms. For example, officials used their power to bully commoners and force transactions; they pretended to comply with imperial orders while acting contrary to them, deceived superiors and concealed the truth, and engaged in corruption and abuse of power. After the establishment of a new dynasty, “deceptive behaviors” within the bureaucratic system almost accompanied economic recovery. For instance, in the early Western Han Dynasty, cases of embezzlement of imperial property and misappropriation of government funds were extremely serious. Even Empress Lü (known for her cruelty) and Emperor Wen (known for his frugality) had to constantly address this issue—either by issuing strict laws or dispatching imperial censors to supervise local governments. If officials dared to embezzle the royal family’s property, they would certainly exploit the common people. Emperor Jing of Han (Liu Qi, 188–141 BCE) once stated in an imperial edict: “Some officials do not abide by laws and regulations; they treat accepting bribes as a transaction, collude with each other to form cliques for private gain, regard harshness as thorough administration, and see cruelty as impartial law enforcement. As a result, innocent people lose their occupations and livelihoods” [33c]. This shows that even during the “Rule of Wen and Jing”—a so-called golden age—corruption within the bureaucratic system was already severe.

In summary, the patrimonial bureaucracy deviates from the genetically ingrained Underlying Protocol of humanity. Due to the extreme self-interest of power, every new patrimonial bureaucratic dynasty is like a giant ship setting sail with inherent defects, suffering from systemic imbalances in politics, economy, and society. In periods when population pressure is low and trust in the bureaucratic system remains, emperors like Taizong of Tang (Li Shimin)—who lived among commoners for a long time in his youth—and many ministers who participated in or witnessed the late Sui peasant uprisings had a genuine understanding of the people’s hardships. They took the fall of the Sui Dynasty as a warning and restrained their words and deeds [

65], which usually allowed the maintenance of superficial prosperity and stability. However, as Montesquieu noted: “After three or four emperors, successors gradually fall into corruption, luxury, laziness, and indulgence. Confined to the imperial palace, their spirits languish, their lifespans shorten, and the royal family declines. Ministers usurp power, eunuchs gain favor, and child emperors often ascend to the throne. The imperial palace then becomes an enemy of the state, and a large group of idlers in the court ruin the hardworking people. Usurpers kill or depose the emperor and establish a new dynasty” [4a].

7. Discussion

In the view of many Western scholars, the Chinese Empire during the medieval period was consistently ahead of Western Europe in terms of civilization and strength [

27,

66], yet its cyclical phenomenon remains fascinating to this day. Some studies have come close to uncovering its inherent essence: deviation from the “Underlying Protocol,” leading to backlash from social injustice and wealth polarization.

Ray Dalio summarized the cyclical changes of a state into six stages—early founding, recovery, prosperity, transition, decline, and collapse—based on eight dimensions: education, competitiveness, innovation and technology, economic output, share of global trade, military strength, strength of financial centers, and reserve currency status. He cited Chinese dynasties after the Tang Dynasty as typical cases of such cycles [

67]. Although his research focuses on measuring the long cycles of a nation’s wealth, power, and comprehensive strength—differing from the direction and focus of this study—his approach offers valuable insight: when dividing long cycles, he identifies wealth polarization caused by institutional injustice as a criterion for cyclical change. This implicitly aligns with the understanding of cyclical evolution in this paper: if the system established in the early founding period serves the self-interest of power, social injustice will reemerge during the recovery stage. Even during the prosperity stage (a so-called “golden age”), failure to check the self-interest of power will exacerbate social injustice and accelerate wealth polarization. Subsequently, driven by the tension of social imbalance, the state will transition to another round of decline and collapse. The length of the entire cycle and the speed of decline and collapse depend on two factors: the degree of power self-interest and the governance performance at each stage. Governance with public service attributes—such as Zhang Juzheng’s reforms in the Ming Dynasty [44b]—may alleviate the backlash of social tension; conversely, poor governance not only fails to alleviate tension but also intensifies its backlash and amplifies the destructive impact of external factors, as seen in the famines and border conflicts at the end of the Ming Dynasty [44c].

Based on the economic situation of the Western Han Dynasty to the Xin Dynasty, Liu Zehua roughly divided the Western Han Dynasty into five periods: 1. Economic recovery and development (the reigns of Emperors Wen and Jing); 2. Economic shift from development to crisis (the reign of Emperor Wu); 3. Economic recovery or rebound (the reigns of Emperors Zhao and Xuan); 4. Economic near-collapse (the reigns of Emperors Yuan, Cheng, Ai, and Ping); 5. Economic collapse and regime downfall (the Xin Dynasty). Despite differing intentions behind this division, significant variations in the social backgrounds of the economic characteristics of these periods, and inconsistencies in the ways dynasties intervened in the economy, this periodization captures the non-linear nature of cycles and reveals a clear thread: the social economic situation fluctuated in response to the orders and policies of the authoritarian regime, primarily driven by the scale of taxes and corvée. Excessive taxes and corvée were the main causes of social unrest [34a]. This conclusion also ties back to the issue of social injustice.

In 2014, Safa Motesharrei and his colleagues used mathematical modeling (incorporating four variables: elite population, commoner population, natural resources, and wealth) to study three social types—unequal societies (with economic stratification), egalitarian societies (without economic stratification), and fair societies (with workers and non-workers)—focusing on their sustainable equilibrium values and maximum population carrying capacities. This pioneering thought experiment showed that in unequal societies, as population grows, elite consumption continues to increase, eventually leading to overconsumption, famine among commoners, and loss of labor force—making social collapse inevitable. Notably, the risk of social collapse is often masked by short-term prosperity; for example, wealth growth may obscure resource depletion [

68]. This conclusion further confirms that social injustice is the internal driver of social collapse, providing support for understanding the rise and fall of patrimonial bureaucratic dynasties.

In fact, within the context of a patrimonial bureaucracy dominated by power self-interest, social injustice persists throughout. As discussed earlier, the so-called “golden ages” in history were merely golden ages for emperors and bureaucrats, not for ordinary people. Jia Yi, a political theorist, stated in a memorial to Emperor Wen of Han (Liu Heng): “Nearly forty years have passed since the founding of the Han Dynasty, yet the savings of both the state and private individuals remain distressingly meager. If rainfall misses the planting season, the people look back anxiously like wolves, fearing poor harvests and loss of livelihood. In years of bad harvests, when people cannot pay taxes, they beg to sell their official titles to raise money for tax payments, or even sell their children to survive” [33d].

The same was true for the Tang Dynasty, regarded as a peak of ancient Chinese civilization. The court imposed heavy taxes and corvée (the “zu, yong, diao” system), supplemented by various additional labor services and surtaxes. During the Zhenguan period, the state collected at least a quarter of the people’s annual harvest. In the event of natural disasters such as floods, droughts, or locust infestations—and consequent poor harvests—the government might take 30–40%, or even over 50%, of the annual income of poor households [

69]. Such exorbitant exploitation clearly far exceeded the actual bearing capacity of farmers. The Tianbao period saw similar conditions: farmers in better circumstances could barely sustain their livelihoods, while those in worse situations were inevitably reduced to bankruptcy and displacement [

70]. In other words, from the Zhenguan period to the Kaiyuan Golden Age, compared to the widespread starvation at the end of the Sui Dynasty, farmers who received land allocations under the Tang Dynasty lived a life of “not starving to death, but never having enough to eat” [32b].

Since the Qin and Han dynasties, large cities in ancient China were not natural products of economic development but were built under the impetus of political power, with their layout and management fully subject to the will of power. There was no independent citizenry within these cities; handicrafts, services, and commerce all relied on the consumption of political elites and were strictly controlled by political power. Even Chang’an, the capital that best embodied the prosperity of the Tang Dynasty, was no exception—it featured a typical power-centered layout. Chang’an had a total of 108 “fang” (districts; 110 during the Longshuo to Kaiyuan reigns of Emperor Gaozong and Xuanzong of Tang, and 109 after the Kaiyuan period). The entire city adopted a neat checkerboard layout, with 54 “fang” in the east and 54 in the west—a division reflecting the social hierarchy of “east for the nobility, west for the commoners”—administered by Chang’an County and Wannian County under the jurisdiction of Jingzhao Prefecture. In terms of layout, streets ran straight and crisscrossed, and “fang” districts were square. Residents lived in houses within walled “fang” and were prohibited from opening doors or building towers facing the streets; they could only enter and exit through “fang” gates set up by the government. In terms of management, the “lifang system” (residential district system) and curfew system were implemented to strictly control the personal freedom of residents. It was not until the Song Dynasty that the layout was changed to a more open street pattern, due to the geographical characteristics of Kaifeng (the Song capital). The design and management of these cities were oriented toward serving the power of the patrimonial bureaucracy—facilitating the protection of the royal family’s safety rather than providing convenience for the daily lives of residents [32b].

The renowned “Kang-Qian Golden Age” was no different. During the Qianlong period, records of people eating chaff and vegetables were widespread. In the summer of 1793 (the 58th year of the Qianlong reign), a British mission arrived in China and found that the country was not as described in Marco Polo’s travels—where gold was abundant and everyone wore silk. Upon setting foot in China, they were shocked by the stark poverty and emaciation of the people. Ordinary Chinese people would express profound gratitude every time they received the mission’s leftover food. They would greedily scramble for the tea leaves used by the British, then boil them to make tea [45a].

8. Common Characteristics of Cyclical Social Collapse

A patrimonial bureaucracy driven by extreme self-interest creates severe institutional injustice, fostering an official culture of “seeking wealth through official positions” and a social culture centered on “officialdom supremacy.” Generally, official positions were neither hereditary nor lifelong; more often than not, they were passed between holders like a rotating stage—”as one group steps down, another takes the spotlight.” In an agrarian society, land was both wealth and the foundation for value appreciation. An official position functioned like a mold, producing one “power-backed landlord” after another. During the Tang Dynasty, the number of positions such as pushe (Grand Councillor), shangshu (Minister), and shilang (Vice Minister) was limited, yet many individuals held these roles. According to Yan Gengwang’s Table of Tang Dynasty Pushe, Shangshu, and Cheng Lang Officials, the total number of people who held such positions throughout the Tang Dynasty exceeded 1,100. Not all officials were corrupt, but a significant number became large landowners due to their official status. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, there were over 53,000 jinshi (successful candidates in the highest imperial examination). Most of these individuals were already landowners before passing the jinshi examination; however, by holding mid-to-high-ranking official positions and thus gaining privileges, they rapidly expanded their landholdings through means such as “land transactions” and rose to become even larger landowners [34c].

Where there is coercive injustice, there is a blade of backlash. The injustice and extreme wealth polarization of the patrimonial bureaucracy led to frequent peasant uprisings in China—more than in any other country in the world. This is also evident from the backgrounds and core demands (slogans) of peasant uprisings throughout Chinese history.

Excluding the Eastern Jin and Southern Song dynasties (which only ruled over southern China), China witnessed 10 unified Qin-style dynasties that governed both northern and southern territories, with an average duration of approximately 150 years. Despite differences in their social structures, economies, cultures, technologies, even systems, and ethnic compositions, these dynasties shared an identical institutional framework: highly centralized patrimonial bureaucratic states [43b]. In such states, power became an object of manipulation and an instrument of exploitation for emperors and officials.

Among these 10 unified dynasties, the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE) and Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE) lasted less than 50 years. Their cycles may seem incomplete and were intertwined with divisions among the upper echelons of society, yet both were overthrown by uprisings led primarily by peasants. Although the Western Jin Dynasty (265–316 CE) and Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE) were conquered by foreign ethnic groups, they both suffered severe blows from peasant uprisings during their existence, bearing the backlash of internal tensions. The remaining six dynasties were as follows: the Western Han Dynasty (211 years, including the Xin Dynasty, 202 BCE–9 CE), Eastern Han Dynasty (195 years, 25–220 CE), Tang Dynasty (289 years, including the Wu Zhou period, 618–907 CE), Yuan Dynasty (98 years, 1271–1368 CE), Ming Dynasty (276 years, 1368–1644 CE), and Qing Dynasty (268 years, 1644–1912 CE). Among these, the Western Han (including the Xin Dynasty), Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties were directly overthrown by peasant uprisings or social revolutions (e.g., the 1911 Revolution). The Eastern Han and Tang dynasties were also rapidly replaced shortly after nationwide peasant uprisings. All these dynasties met their end through the “correction” of the “Underlying Protocol,” leading to a complete restructuring of the state.

Demands (Slogans) of Peasant Uprisings and the Situation of Wealth Polarization in Successive Dynasties:

| Dynasty |

Demands of Peasant Uprisings |

Situation of Wealth Polarization |

| Qin Dynasty |

Chen Sheng and Wu Guang Uprising: “Are nobles and high officials born to be superior?” – Resisting exploitation by power and economic solidification. |

The direct cause was the Qin Dynasty’s harsh penalties for failing to report for military service on time, but the underlying cause lay in the extreme exploitation of civilian labor under the state’s mobilization system [71]. Archaeology and bamboo slips (e.g., Shuihudi Qin Bamboo Slips) confirm that Qin laws regulated the conscription and management of corvée with extreme rigor, and its criminal penalties were brutal [72]. |

| Western Han Dynasty (Including the Xin Dynasty) |

Red Eyebrow and Green Forest Uprisings: “He who kills shall die; he who injures shall compensate for the harm!” – Fighting for the right to survival and justice. |

The core issue was the failure of Wang Mang’s reforms, which exacerbated land annexation and the antagonism between the rich and the poor. The History of the Han Dynasty · Treatise on Food and Commodities records that during the reign of Emperor Ai, “powerful officials and wealthy commoners possessed millions in property, while the poor and weak became increasingly destitute.” Ge Jianxiong, through calculations of population and cultivated land data, revealed the structural contradiction where the landlord class occupied large tracts of land while peasants went bankrupt and became refugees [73a]. |

| Eastern Han Dynasty |

Yellow Turban Uprising: “The Azure Sky has perished; the Yellow Sky shall prevail; in the year of Jiazi, the world shall enjoy great fortune.” – Attempting to establish a new peaceful order. |

The root cause lay in the malignant development of the manorial economy of powerful landlords and political corruption. Zhong Changtong, in his contemporary essay Changyan · On Order and Chaos, profoundly exposed the sharp antagonism where “the mansions of powerful families stretch for hundreds of rooms, and fertile fields cover the wilderness” [74]. |

| Western Jin Dynasty |

Li Te’s Refugee Uprising: Sichuan civilians built stockades for self-defense to resist oppression by local officials and powerful clans. |

The wars and natural disasters triggered by the “War of the Eight Princes” were catalysts, but the root cause was the monopoly of political and economic resources by aristocratic clans. With economic and political privileges merged into one, the Western Jin’s “land occupation system” essentially recognized and protected the interests of large aristocratic estates, reducing a large number of peasants to dependent tenants or refugees [75]. |

| Sui Dynasty |

Late Sui Peasant Uprisings: “Do not die in vain in Liaodong!” – Resisting corvée and military service that reduced the people to destitution. |

Similar to the Qin Dynasty, the overexploitation of civilian labor was the main cause. According to The History of the Sui Dynasty · Biography of Emperor Yang, the construction of the eastern capital, the excavation of the Grand Canal, and repeated military campaigns against Liaodong mobilized a total of over 10 million civilian workers. This led to a tragic situation where those who left never returned, those who stayed lost their livelihoods, and people resorted to cannibalism [76]. |

| Tang Dynasty |

Huang Chao Uprising: “King Huang raises troops for the common people.” – Resisting the exploitation by the power of the patrimonial bureaucracy. |

The direct causes were the heavy taxes resulting from the fiscal crisis (e.g., additional corvée after the “Two-Tax System”) and the harsh salt monopoly policy. Chen Yinke, in Draft Essays on the Political History of the Tang Dynasty, pointed out that conflicts between the central government and local military governors (fanzhen), as well as between old aristocratic clans and emerging classes, intertwined and finally erupted through the Huang Chao Uprising [77]. |

| Northern Song Dynasty |

Wang Xiaobo Uprising: “I hate the inequality between the rich and the poor; I shall equalize it for you.” Fang La Uprising: “This Dharma is equal; there is no distinction between high and low!” |

The state policy of “not suppressing land annexation” led to a high degree of land concentration. Large landlords (official households, influential households, big merchants, and usurers), accounting for only 5-6% of total households, controlled most of the land in the country [78,79]. The “Flower and Rock Gang” (a system of expropriating rare flowers and rocks for the imperial court) in the late Northern Song Dynasty was an extreme manifestation of exploitation by bureaucratic privileges. |

| Yuan Dynasty |

Red Turban Uprising: “Maitreya will descend; the Bright King will appear!” – Resisting injustice and pursuing justice. |

Ethnic hierarchy and land annexation (e.g., the enclosure of pastures by Mongol nobles) were intertwined. Han Rulin, editor-in-chief of History of the Yuan Dynasty, pointed out that in the late Yuan Dynasty, officialdom was corrupt, finances were exhausted, the reckless issuance of paper money led to hyperinflation, and coupled with the Yellow River floods, the people were reduced to extreme destitution [80]. |

| Ming Dynasty |

Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong Uprisings: “Welcome the Rebel King; no grain tax shall be paid.” “Equalize land and exempt taxes.” |

The annexation of land by the privileged class was shocking, and the imposition of the “Three Extra Taxes” (for border defense, suppressing rebels, and military training) was the last straw that crushed the peasants. Gu Cheng, in History of the Late Ming Peasant Wars, meticulously verified the high degree of land concentration, unequal taxes and corvée in the late Ming Dynasty, as well as the heavy burden imposed on ordinary people by the “Liao Tax” (for border defense against the Liao), “Jiao Tax” (for suppressing rebels), and “Lian Tax” (for military training) [30b,81]. |

| Qing Dynasty |

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement: “Cultivate the same land; eat the same food; no place shall be unequal; no one shall go hungry or cold.” 1911 Revolution: “Expel the Manchus; restore China; establish a republican government; equalize land ownership.” |

The privileged class (royal family, officials, landlords, and Bannermen) monopolized all resources. The bottom-level people (peasants, handicraftsmen) not only “had no land to cultivate and no food to eat” but also faced “exorbitant taxes and levies, ethnic oppression, and judicial injustice.” The traditional patrimonial bureaucracy could no longer cope with the survival challenges faced by modern China [82,83]. |

Of course, social collapse cannot rule out the role of factors such as the natural environment, external social relations, population, and resources, but these are not the true internal drivers.

China is a vast country with abundant resources and a geographically enclosed terrain. In history, it was rarely conquered by foreign ethnic groups, and even less likely to perish due to shortages of natural resources. Under normal governance, common short-cycle natural disasters would not trigger social collapse—even in the face of large-scale famines like the one in the 1960s, which was “70% man-made disaster and 30% natural disaster.” Disasters on the scale of climate change are even rarer; shocks of the kind that the Roman Empire once suffered [

84] typically occur only after a state has existed for more than a millennium. For dynasties with a lifespan of less than 200–300 years, such factors hold little significance. Therefore, although cyclical factors like the natural environment, external conflicts, and resource shortages exert a superimposed effect—alongside the degree of power self-interest and poor governance—during the stage of social collapse, they are not the internal drivers of the cyclical phenomenon.

As for the “Malthusian trap” proposed in An Essay on the Principle of Population, it did manifest in the rise and fall of Chinese dynasties, as there is a limit to the population that land productivity can support [32b]. However, the pressure of population growth in China was linked to the irrationality of the patrimonial bureaucracy [43b]. For the Chinese royal family, population—like land and forests—was part of its “family property,” and there existed an extra-economic personal dependency relationship [34d]. As a component of this “family property,” rulers of all dynasties allowed population reproduction to proceed naturally; some even took the increase or decrease in household registration as a key criterion for evaluating local officials’ performance [73b]. Yet the government provided almost no social welfare for the people, including old-age security, forcing them to rely on the concept of “raising children for old age.” Driven by the traditional patriarchal clan system and the utilitarian need for self-security, the cultural concept of “more children bring more blessings” and a competitive attitude toward childbearing gradually took shape. This had a causal relationship with the power self-interest (PS) of China’s patrimonial bureaucracy, but it remained a superimposed and indirect factor in the process of social collapse.

In the rise and fall of a state, these external factors—under the premise of power self-interest and social injustice—act as interference variables (γ) that affect the degree of social imbalance (the people’s tolerance) and accelerate social collapse. They interact with the degree of power self-interest and governance performance, resulting in non-linear periodicity (hysteresis) and volatility. Different degrees of power self-interest (PS) exert varying levels of negative impact on society’s ability to address crises such as natural disasters, external conflicts, population pressure, and resource shortages. When the balance between self-interest and fairness is disrupted, society may remain within the tolerance range for social injustice due to factors such as improved environmental conditions (e.g., abundant survival resources offsetting unfairness caused by self-interest) or self-correction (e.g., China’s Reform and Opening-up, Vietnam’s Đổi Mới). In such cases, the backlash of Underlying Protocol tension against the power-holding class may be delayed or alleviated, but this backlash will not disappear automatically. The non-linear volatility (δ), periodicity (hysteresis) (sin[θ]), and disturbances from individual events (ϵ) resulting from their interaction can be expressed by the function:γ = f(δ, sin[θ], ϵ)

9. Historical Review and Contemporary Bureaucracy

China’s patrimonial bureaucracy originated in the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046–771 BCE). Prior to the Western Zhou, the earliest Xia Dynasty remains a legendary regime, with neither archaeological evidence to confirm nor refute its existence. The subsequent Shang Dynasty, renowned for its oracle bone inscriptions, was the only Chinese dynasty to endure for over 500 years; however, it operated as a confederation of states rather than a patrimonial bureaucratic system [

85].

After its victory in the Battle of Muye, the Western Zhou Dynasty replaced the Shang Dynasty and implemented a system of “syncretism of family and state” [

86]. The Zhou king styled himself as the “Son of Heaven,” the suzerain of all under heaven, and claimed that “All lands under heaven belong to the king; all people within the realm are the king’s subjects” [

87]. During the reign of the Duke of Zhou (Ji Dan), the “enfeoffment system” was systematically promoted and refined nationwide. Enfeoffed states enjoyed nearly complete autonomy, and the obligatory relationship between the king and vassals superficially resembled Western European feudalism. However, unlike Western European feudalism, which was based on contracts (customary law), Western Zhou’s enfeoffment was rooted in the patriarchal clan system. The primary recipients of enfeoffment were blood relatives (e.g., the rulers of Lu and Jin) and a few meritorious officials (e.g., the Jiang clan of Qi), with the system maintained through ritual-music institutions and blood ties. The direct jurisdiction of the royal family was limited to the capital region.

As generations passed, blood ties weakened. By the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods), vassal states gradually became alienated from the royal court, and the “rituals collapsed and music declined.” During this era, population growth and the adoption of iron tools led to the gradual disintegration of the well-field system. To compete for hegemony, several vassal states successively implemented institutional reforms, such as Guan Zhong’s reforms in Qi, Li Kui’s reforms in Wei, Wu Qi’s reforms in Chu, and Shang Yang’s reforms in Qin. Among these, Shang Yang’s reforms were the most thorough, establishing a nationwide militarized system where the military merit hierarchy, household registration, collective punishment laws, and industrial policies all centered on military needs. In 221 BCE, Ying Zheng (Emperor Qin Shi Huang) conquered the six eastern states, popularized a bureaucratic system based on the prefecture-county model nationwide, and established a typical patrimonial bureaucratic dynasty—elevating the degree of power self-interest and centralization to new heights.

It was not until the early 20th century, after the victory of the 1911 Revolution, that China entered the era of republicanism. Sun Yat-sen’s Provisional Constitution designed a power-checking framework of “separation of powers among five yuan (branches),” ending the patrimonial bureaucratic system that had lasted for over 2,100 years. However, with the “shot of the October Revolution,” which brought Soviet-style socialism to China, it also introduced the Soviet-style bureaucracy. The Russian Empire (the predecessor of the Soviet Union), like ancient China, was a patrimonial bureaucratic state emphasized in Max Weber’s studies [43c]. The “democratic centralism” and collective leadership proposed by Lenin were essentially replicas of the traditional bureaucracy: the “tsarist army” of the patrimonial era was replaced by the principle of “the Party commands the gun”; “tsarist family property” was replaced by state-owned or collectively owned assets controlled by power; and the tsar’s power was replaced by the “collective leadership” under “democratic centralism.” The logic of power operation remained virtually unchanged—the power-holding class served as both rule-makers, referees, and players. Thus, the Soviet-style “collective leadership” under “democratic centralism” remained an irrational system.

Whether in groups of two to three hundred, twenty to thirty, or even eight to nine people, when making decisions within opaque “small circles,” individuals are influenced not only by conformity bias but also by affiliation bias [

88]. People suppress dissent to maintain group harmony and avoid awkwardness, and such “groupthink” may lead to views more extreme than the average of individual opinions. Social psychologist David G. Myers argues that it is precisely factors such as the group’s need for cohesion, insularity, and leadership authority that contributed to catastrophic failures like the Pearl Harbor attack, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the Vietnam War [

89].

Furthermore, individuals within a group exhibit psychological traits such as anonymity and diffusion of responsibility [

90]. In anonymous environments, adults are more prone to selfish behavior; when making decisions collectively with others in a group or team, they are more likely to accommodate others or shirk responsibility [

91]. Thus, in contexts emphasizing “centralization,” relevant personnel tend to act according to the inherent tendency of “seeking advantages and avoiding disadvantages” [

92]—as the common saying goes, “one’s position dictates one’s perspective”—making it difficult to sustain fair, efficient, and scientific decision-making and management.

Moreover, Soviet-style socialist theory regards the state as an instrument of violence rather than a public service apparatus. When deviating from grassroots agreements and facing public discontent or resistance, it tends to rationalize and normalize violent discipline [