1. Introduction

Tourism has become one of the most digitally transformed sectors of the global economy [

1,

2]. Destinations are increasingly adopting artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, virtual and augmented reality, and big data analytics to manage visitor flows and enhance experiences [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These technologies are promoted as solutions to long-standing challenges such as overtourism [

6,

7], environmental degradation [

8,

9] and fragmented governance [

10,

11], which threaten the resilience and competitiveness of destinations [

12]. Within this broader transition, digital twins—virtual replicas of real-world systems that integrate real-time data and simulate future scenarios—are emerging as one of the most transformative yet understudied innovations [

13,

14]. Their appeal lies in their capacity to provide decision-makers with dynamic tools for anticipating visitor behavior [

15], optimizing resource use [

16], and designing more sustainable and inclusive tourism systems [

17]. At the same time, the adoption of digital twins in tourism has implications that extend well beyond technical efficiency [

18]. They embody new forms of digital governance, raise questions of privacy, legitimacy, and authenticity, and risk amplifying inequalities if benefits are unevenly distributed [

19]. For this reason, their relevance must be situated within broader debates about sustainability, institutional trust, and public acceptance [

20,

21,

22]. Smart tourism is an example of good practice as a strategic response to contemporary challenges in tourism [

23,

24]. As the European Union and international organizations such as UNWTO increasingly promote smart destinations [

25] and digital sustainability agendas [

26], the question of how digital twins are perceived by tourists and stakeholders acquires both practical urgency and theoretical significance.

Despite growing policy interest, academic research on digital twins in tourism remains in its infancy. Existing scholarship has focused predominantly on technical capabilities [

27], system design [

28], and managerial applications [

29,

30], while social, cultural, and ethical dimensions have been comparatively neglected. Critical questions remain unanswered: How do tourists evaluate the trustworthiness, usefulness, and risks of digital twin applications? To what extent do stakeholders perceive them as legitimate tools for governance and sustainability? And how do contextual factors—such as local infrastructure, governance capacity, and branding—shape these perceptions across destinations? Addressing these questions is crucial, as the long-term viability of digital twins depends on balancing efficiency with social legitimacy and ensuring that technological advances do not exacerbate inequalities or erode authenticity.

This study responds to these gaps by adopting a mixed-methods design that combines a large-scale survey of tourists (N = 1,286) with semi-structured interviews with destination managers and stakeholders across four Spanish cities. By integrating quantitative and qualitative perspectives, the research captures both the measurable determinants of acceptance and the contextual nuances of governance, equity, and readiness. In doing so, it extends established technology acceptance models—most notably the Technology Acceptance Model [

31] and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [

32]—by incorporating sustainability attitudes and awareness, which have been emphasized in tourism research as critical drivers of digital adoption. At the same time, it addresses emerging concerns of trust, legitimacy, and inclusivity that have been highlighted in debates on smart destinations and governance capacity [

33], demonstrating that digital twin acceptance in tourism depends not only on technical performance but also on institutional reliability and social responsibility.

The contribution of this study is threefold. Theoretically, it demonstrates that acceptance of digital twins in tourism is shaped not only by classical adoption constructs such as trust, usefulness, and ease of use but also by sustainability orientations and governance factors specific to destination contexts. Methodologically, it shows the value of mixed-methods approaches in capturing both demand-side and supply-side perspectives, thereby bridging tourist attitudes with institutional conditions. Practically, it provides actionable insights for policymakers and destination managers, highlighting that successful implementation depends less on technological sophistication than on inclusive governance, sustainable financing, and the cultivation of public trust.

Spain was selected as the empirical setting because it represents one of Europe’s leading tourism markets and has positioned itself at the forefront of smart destination development [

34]. The chosen cities—Barcelona, Málaga, Valencia, and Benidorm—offer contrasting yet complementary contexts: Barcelona as a global cultural hub facing acute overtourism [

35], Málaga as a sustainability-oriented city with strong smart infrastructure [

36], Valencia as a green-branded destination prioritizing equity [

37], and Benidorm as a leisure hub with heavy reliance on external funding [

38]. These cases provide a strategic lens to examine how digital twin adoption is shaped not only by technical readiness but also by political will, social legitimacy, and economic capacity. Against this backdrop, the aim of the study is to assess the acceptance and perceived feasibility of digital twin applications in tourism by combining tourist and stakeholder perspectives. The specific objectives are threefold: (1) to identify the core dimensions of tourist acceptance of digital twins through factor-analytic modeling; (2) to examine how governance, equity, and readiness concerns shape stakeholder perspectives; and (3) to integrate these insights into a multidimensional framework that links tourist demand with institutional supply. On this basis, the study tests the Main Hypothesis (H1): the acceptance of digital twin applications in tourism is determined by tourists’ perceptions of trust, usefulness, ease of use, perceived risks, sustainability attitudes, and awareness, while destination-specific contexts shape variation in these perceptions.

The results demonstrate that tourist acceptance of digital twins can be reliably captured through a six-factor model encompassing trust, usefulness, ease of use, perceived risks, sustainability attitudes, and awareness. Confirmatory factor analysis provided excellent model fit, confirming the robustness of these dimensions. Cross-city comparisons revealed meaningful contextual variation: Barcelona respondents expressed higher institutional trust, Valencia respondents showed stronger support for sustainability-oriented applications, Málaga respondents were more concerned about technical reliability, and Benidorm respondents emphasized both digital reliance and authenticity concerns. Stakeholder interviews complemented these findings by identifying overtourism management, sustainability optimization, and governance innovation as the main perceived opportunities of digital twins, while financial constraints, equity concerns, and data privacy emerged as key barriers. Importantly, readiness for adoption differed across destinations, with Málaga perceived as most prepared due to existing infrastructure, while Benidorm faced significant financial dependency. These results highlight that the acceptance and feasibility of digital twins depend not only on tourists’ perceptions but also on governance capacity, equity considerations, and local political-economic contexts.

2. Literature Review

Trust is widely recognized as a fundamental prerequisite for the adoption of digital technologies [

39]. In online environments, trust encompasses not only confidence in the accuracy and reliability of information but also belief in the integrity and credibility of the institutions managing these digital systems [

40]. Within the tourism sector, trust in organizations has been consistently linked to travelers’ willingness to use mobile applications and share personal data [

41]. Since digital twin technologies rely on complex data integration across multiple sources and require high levels of institutional reliability [

42], trust becomes a cornerstone of their acceptance. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that higher levels of trust and perceived reliability will enhance tourists’ willingness to adopt digital twin applications (H1a). Beyond individual attitudes, trust contributes to perceptions of legitimacy, accountability, and transparency in technology-enabled governance, which collectively shape the societal acceptance of emerging digital infrastructures [

43]. In this sense, trust functions as both a psychological and institutional mechanism — a bridge between technological functionality and socio-political legitimacy. It ensures that users perceive digital transformation not as a threat but as a cooperative and ethically grounded process.

Building upon this foundation, technology adoption theory provides a complementary explanatory lens. Both the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) emphasize perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as key determinants of technology acceptance. Empirical research confirms that individuals are more likely to adopt new technologies when they offer tangible benefits and can be used with minimal cognitive effort [

44]. In tourism, mobile and smart applications are valued when they simplify trip planning, reduce stress, and enrich experiences through personalization and interactivity [

45]. Therefore, digital twins—conceived as advanced tools within smart tourism ecosystems—are expected to achieve higher adoption rates when tourists perceive them as both highly useful and easy to use (H1b). Moreover, perceived ease of use often reinforces perceived usefulness, as effortless interaction enhances the perceived value and efficiency of the technology [

46]. This dynamic interplay reflects the dual motivational structure underlying tourist engagement with digital systems, suggesting that usability and functionality must be designed in tandem to promote sustained adoption.

However, alongside trust and perceived usefulness, perceived risks persist as significant barriers to digital adoption. Prior studies have identified a range of perceived risks in online and mobile contexts, including concerns over privacy, surveillance, data misuse, technical failures, and the loss of authenticity [

47]. Such concerns are particularly pronounced in tourism, where authentic and spontaneous experiences form an integral part of travelers’ expectations [

48,

49]. When tourists believe that technological mediation may compromise these values, their willingness to engage with new tools diminishes [

50]. Consequently, it is hypothesized that stronger perceptions of risk will negatively affect tourists’ willingness to adopt digital twin applications (H1c). From a broader perspective, risk perception highlights the inherent tension between technological efficiency and cultural legitimacy. Adoption, therefore, depends not only on rational assessments of functionality but also on deeper normative judgments regarding ethics, privacy, and authenticity. In this regard, transparent communication and ethical governance mechanisms play crucial roles in mitigating perceived risks and restoring user confidence in digital infrastructures [

51].

A further determinant influencing technology acceptance is sustainability orientation. Recent scholarship in smart tourism highlights the potential of digital innovations to mitigate overtourism, optimize resource consumption, and promote environmental stewardship [

52]. Tourists with strong pro-sustainability attitudes tend to support technologies that facilitate responsible behavior, redistribute visitor flows, and encourage environmentally conscious decision-making [

53]. At the same time, awareness and familiarity with digital infrastructures reduce uncertainty, foster trust, and enhance openness to experimentation [

54]. Digital awareness thus represents a form of cultural capital that lowers barriers to innovation and enables tourists to perceive digital twins as accessible and beneficial rather than abstract or alien [

55]. Consequently, positive sustainability orientations combined with higher digital familiarity are hypothesized to strengthen support for digital twin adoption (H1d). Moreover, sustainability-minded tourists may act as social influencers, diffusing favorable perceptions of digital tools and reinforcing the alignment between technological innovation and environmental responsibility [

56]. This relationship underscores that the adoption of smart tourism technologies is as much a moral and cultural process as it is a technical one.

Despite these general trends, prior research indicates that attitudes toward smart technologies are context-dependent, varying across destinations according to governance capacity, infrastructural readiness, and branding strategies [

57]. The survey results from Spain confirm this contextual variation, revealing significant inter-city differences in perceptions of trust, authenticity, technical reliability, and sustainability. Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that tourists’ attitudes toward digital twin applications differ significantly across destinations (H2). Stakeholder interviews further illustrate these distinctions: in Málaga, advanced smart infrastructure [

58] is expected to foster greater readiness and technological confidence (H2a); in Valencia, sustainability-oriented branding [

59] should enhance support for environmentally aligned applications (H2b); in Barcelona, a strong reputation for innovation and digital leadership [

60] is likely to reinforce institutional trust (H2c); whereas in Benidorm, a leisure-oriented destination [

61] that relies heavily on external funding, concerns related to authenticity loss and surveillance are anticipated to be more pronounced (H2d). Together, these hypotheses integrate individual-level psychological drivers with destination-level governance and cultural contexts. They highlight that digital twin acceptance in tourism requires not only user trust and technological functionality but also coherent managerial strategies that align innovation with local sustainability goals and legitimacy priorities.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a pragmatic epistemological position, which is widely recognized as suitable for mixed-methods research in the social sciences. Pragmatism emphasized the practical value of knowledge and acknowledged that complex social phenomena—such as the adoption of digital twins in tourism—were best understood through multiple forms of evidence. Rather than committing exclusively to positivist or interpretivist paradigms, a pragmatic stance allowed for the integration of quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews, thereby combining breadth with depth. The survey provided measurable patterns of tourist attitudes and behavioral intentions, while the interviews captured stakeholder perspectives and contextual nuances. This dual strategy ensured that findings were both empirically grounded and sensitive to the social, political, and organizational dimensions of smart tourism and digital twin applications. Field research was conducted between September 2024 and September 2025, during which the authors repeatedly visited the selected destinations to carry out data collection.

3.1. Quantitative Component

The study was based on a sample of 1,286 respondents. The gender structure was relatively balanced, comprising 48.4% males (n = 622) and 51.6% females (n = 664). With regard to educational attainment, the majority of respondents had completed higher education, with 39.7% holding a college or faculty degree and 18.0% possessing an MSc or PhD. A further 32.3% reported secondary school education, while 10.0% had only completed ordinary schooling. The age distribution revealed that younger and middle-aged adults were predominant: 29.8% were aged 25–34 years, 24.7% were 35–44, and 13.1% were 18–24. Older participants were less represented: 16.3% were aged 45–54, 9.6% were 55–64, and only 6.5% were over 65. In terms of country of residence, most respondents were from Spain (32.9%), followed by the United Kingdom (10.7%), France (10.4%), Germany (9.6%), and the Netherlands (9.5%). Smaller proportions originated from Sweden (6.5%), Belgium (5.6%), Switzerland (5.6%), Italy (4.9%), and the United States (4.2%). Travel behavior patterns indicated that a plurality of respondents traveled one to two times per year (42.7%), while 37.9% reported traveling three to five times annually. Frequent travelers, defined as those traveling more than five times per year, represented 14.5% of the sample, whereas only 4.9% reported traveling less than once per year. Analysis of digital device usage while traveling showed that smartphones were dominant (76.0%), followed by tablets (14.9%), laptops (6.1%), and other devices (3.0%), underscoring the centrality of mobile connectivity in shaping contemporary travel experiences.

The survey was conducted exclusively on-site across four Spanish destinations: Barcelona, Valencia, Málaga, and Benidorm. Data collection took place at key tourist hotspots, including cultural landmarks, heritage sites, visitor centers, and transport hubs (e.g., airports, train stations). A total of 1,286 valid responses were collected, distributed as follows: Barcelona (n = 362, 28.1%), Valencia (n = 317, 24.7%), Málaga (n = 308, 23.9%), and Benidorm (n = 299, 23.3%). Respondents were approached through an intercept survey method while actively engaging in tourism activities. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with surveyors rotating across different locations and times of day to reduce sampling bias. The original questionnaire consisted of 49 statements designed to measure tourists’ perceptions of digital twin applications in tourism. After data cleaning and reliability analysis, 39 statements were retained. These were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The development of the instrument was guided by established theoretical perspectives. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and its successor, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) informed the measurement of perceived usefulness and ease of use. Items addressing trust, credibility, and risk were derived from research on online trust and e-service adoption. Scholarship on smart tourism and smart destinations emphasized the integration of digital tools and personalization [

62,

63], while literature on digital twin technologies in engineering and urban management informed items relating to accuracy, data integration, and credibility [

64]. Finally, sustainability items were grounded in established research on sustainable tourism, reflecting concerns with overcrowding, environmental protection, and heritage preservation [

65]. Taken together, the 39 statements reflected a multidimensional framework combining technology acceptance, trust and risk, smart tourism, and sustainability perspectives (

Appendix A).

3.2. Qualitative Component

The qualitative component comprised semi-structured interviews with stakeholders across four Spanish cities. Stakeholders were selected from five groups: local government and destination authorities, the tourism and hospitality sector, small businesses and cultural institutions, civil society and community representatives, and technology/data partners. This distribution reflected maximum variation sampling, ensuring representation of diverse interests and experiences. The decision to conduct approximately 20–23 interviews was consistent with qualitative research standards, which suggested that 15–30 interviews are typically sufficient to reach thematic saturation in multi-stakeholder studies [

66]. Distributing interviews across different urban contexts enabled comparative analysis and exploration of five key themes identified in the literature: overtourism, sustainability, challenges, equity, and readiness. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis [

67]. The analysis followed six steps: (1) familiarization with transcripts; (2) open coding; (3) clustering of codes into categories; (4) review of candidate themes; (5) definition and naming of themes; and (6) integration into the analytical framework. Coding was both deductive, based on sensitizing concepts from the literature, and inductive, allowing novel insights to emerge. To enhance reliability, coding was iterative and cross-checked across cases, with illustrative quotations retained to preserve authenticity. Comparative analysis across Barcelona, Málaga, Valencia, and Benidorm further highlighted convergences and divergences in stakeholder perspectives.

3.3. Analytic Strategy

Quantitative analyses proceeded in several steps. The suitability of the dataset for factor analysis was assessed with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using maximum likelihood extraction was conducted, followed by rotation to enhance interpretability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) validated the six-factor model, with fit assessed using χ², χ²/df, root mean square residual (RMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and incremental indices (CFI, TLI, IFI, NFI), as well as parsimony measures. Reliability was examined using composite reliability, while convergent and discriminant validity were assessed through average variance extracted (AVE), inter-construct correlations, and heterotrait–monotrait ratios (HTMT). One-way ANOVA was used to test inter-city differences. The qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis as described above, and integrated with quantitative findings to enable methodological triangulation. This two-stage strategy ensured that results were both statistically robust and contextually grounded.

4. Results

The suitability of the dataset for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value was 0.938, indicating an excellent degree of common variance among the variables and confirming that the data are highly appropriate for factor analysis. In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ²(741) = 25,286.357, p < .001, rejecting the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. This result confirms that the observed correlations among variables are large enough to justify the application of factor analysis. Taken together, these outcomes strongly support the appropriateness of proceeding with factor analysis, as both the KMO and Bartlett’s test demonstrate that the dataset meets the necessary assumptions.

Table 1.

Total Variance Explained by Extracted Factors.

Table 1.

Total Variance Explained by Extracted Factors.

| Factor |

Eigenvalue (Initial) |

% of Variance (Rotated) |

Cumulative % (Rotated) |

| 1 |

9.059 |

10.857 |

10.857 |

| 2 |

3.446 |

10.339 |

21.196 |

| 3 |

3.317 |

9.587 |

30.783 |

| 4 |

3.193 |

9.515 |

40.298 |

| 5 |

2.958 |

8.727 |

49.025 |

| 6 |

2.499 |

6.982 |

56.007 |

The total variance explained indicated that six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained, accounting for 62.75% of the variance in the initial solution. After extraction with the maximum likelihood method, these six factors explained 56.01% of the variance. Rotation redistributed the explained variance more evenly across the factors, with individual contributions ranging between 6.98% and 10.86%. This balanced distribution enhanced the interpretability of the factor structure, suggesting that the six-factor solution provides a parsimonious and meaningful representation of the underlying data.

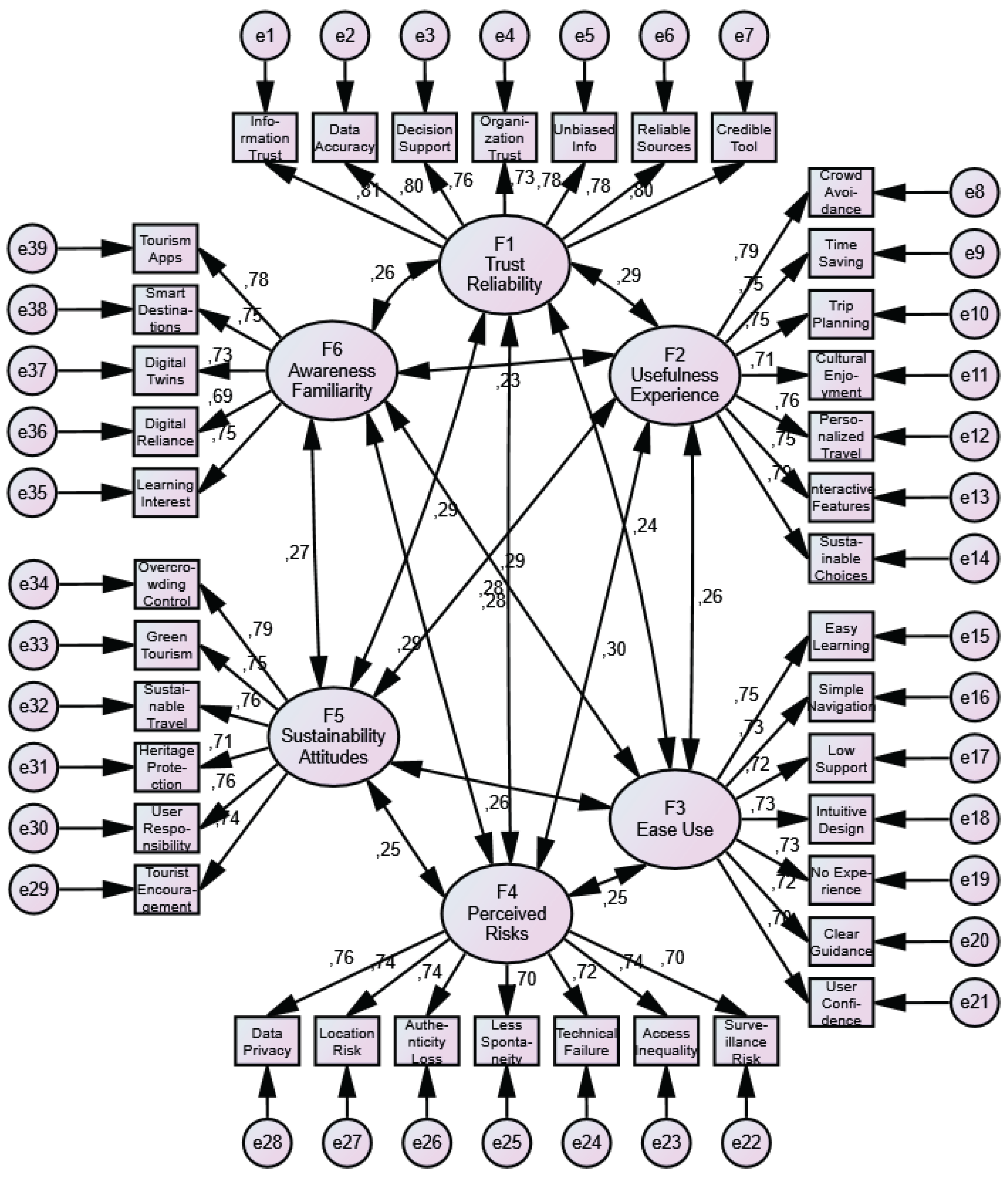

The rotated factor matrix (

Table 2) confirmed a coherent six-factor solution that aligns with theoretically meaningful dimensions of attitudes toward digital twin applications in tourism. The identified dimensions illustrate that the acceptance of digital technologies in tourism is not reducible to technical or functional considerations but rather emerges from a complex interaction between trust, perceived benefits, usability, perceived risks, sustainability values, and awareness. Together, these dimensions articulate a multidimensional framework that integrates classical determinants of technology acceptance with the ethical, experiential, and contextual factors characteristic of tourism environments. The first dimension, related to trust and reliability, reflects tourists’ belief in the credibility of information, the accuracy of data, and the integrity of the organizations responsible for managing and delivering digital services. This form of trust extends beyond the functional reliability of the system to encompass confidence in institutional competence, ethical standards, and transparency. It captures a broader sense of assurance that digital tools operate in accordance with public values and professional accountability. Such trust plays a decisive role in reducing uncertainty and perceived vulnerability, allowing users to engage with digital environments without fear of misuse or misrepresentation. In tourism, where emotional and experiential engagement is central, this confidence is essential to bridging the gap between technological mediation and authentic travel experiences.

The second dimension, encompassing perceptions of usefulness and experiential value, emphasizes that tourists adopt digital twins not only because of efficiency gains but also because of the experiential enrichment they offer. The perceived usefulness of digital twins derives from their ability to improve trip planning, save time, and provide personalized and interactive experiences that enhance cultural immersion and enjoyment. This dual character—simultaneously instrumental and hedonic—illustrates that technological adoption in tourism is motivated by both pragmatic and affective considerations. The sense of empowerment that arises when travelers feel that technology facilitates rather than replaces authentic experiences reinforces overall acceptance and satisfaction. Ease of use emerged as a separate yet closely connected dimension, underscoring the role of design simplicity and cognitive accessibility in encouraging adoption. Tourists value digital applications that are intuitive, easy to learn, and require minimal technical effort. When interfaces are clear and navigation straightforward, users experience a sense of control and confidence that reduces apprehension toward innovation. Ease of use thus serves as both a direct determinant of behavioral intention and an indirect enhancer of perceived usefulness. In the tourism context—where spontaneous decisions and varied digital literacy levels are common—simplicity and guidance become central to ensuring inclusivity and positive user experiences.

Perceived risks form a counterbalancing force within this framework, capturing concerns about privacy, surveillance, technical errors, and the potential loss of authenticity. Unlike in other digital domains, risk perceptions in tourism are deeply intertwined with cultural and experiential expectations. Travelers may fear that digital systems will over-structure their journeys or diminish the spontaneity and emotional richness that characterize tourism experiences. Concerns over surveillance and data misuse further heighten these reservations, reflecting a broader societal unease about digital monitoring and control. Such perceptions highlight that technological adoption is not a purely rational process but is filtered through moral and emotional evaluations that can override functional advantages if trust and transparency are insufficient. The sustainability dimension reflects a growing recognition that technological innovation in tourism must align with ethical and environmental imperatives. Tourists increasingly assess new technologies through the lens of their contribution to sustainable practices such as the reduction of overcrowding, the protection of heritage, and the promotion of responsible behavior. When digital twins are perceived as supporting environmentally conscious travel and equitable destination management, they gain legitimacy and moral value that transcend utilitarian considerations. This dimension thus anchors the acceptance of digital technologies in normative frameworks of responsibility and collective good, indicating that sustainability functions as both a motivator and a moral justification for adoption.

Finally, the dimension of awareness and familiarity highlights the cognitive and cultural preconditions for engaging with advanced digital systems. Awareness encompasses both knowledge of digital technologies and habitual reliance on them in everyday life, while familiarity reflects confidence derived from previous experience and curiosity about further learning. Tourists who are already accustomed to using mobile applications, smart platforms, and other digital tools tend to approach innovations like digital twins with greater openness and less uncertainty. Awareness reduces the psychological distance between users and technology, normalizing its presence in the travel experience and reinforcing perceptions of ease, trust, and usefulness. It also acts as a conduit for learning and experimentation, fostering adaptive behavior in rapidly evolving digital environments. Viewed together, these six dimensions portray digital twin adoption as a multifaceted process shaped by intertwined cognitive, emotional, ethical, and contextual influences. Trust and risk represent opposing but complementary forces defining users’ confidence boundaries; usefulness and ease of use describe the functional and experiential value of technology; while sustainability and awareness situate adoption within broader moral and cultural frameworks. The resulting model depicts digital transformation in tourism as a socio-technical phenomenon—one that depends as much on institutional legitimacy, design quality, and ethical coherence as on individual perceptions of convenience or efficiency. This integrated understanding reinforces that the successful implementation of digital twins in tourism requires not only technological sophistication but also sustained efforts to build trust, enhance digital literacy, and align innovation with the principles of sustainable and human-centered tourism development.

The confirmatory factor analysis (

Figure 1) indicated that the six-factor model provided an excellent fit to the data. The chi-square test was non-significant, χ²(687) = 736.131,

p = .095, and the relative chi-square (χ²/df = 1.072) was well below the recommended threshold, suggesting minimal discrepancy between the model and the observed data. Absolute and error-of-approximation indices supported this conclusion, with RMR = .037 below the .05 cut-off and RMSEA = .007 (90% CI [.000, .012], PCLOSE = 1.000) indicating a near-perfect approximation. Incremental fit indices further confirmed the model’s superiority over the independence model (CFI = .998, IFI = .998, TLI = .998, NFI = .971), while parsimony-adjusted measures (PCFI = .925; PNFI = .900) demonstrated a strong balance between model fit and simplicity. The Hoelter index values (N = 1308 at

p = .05; N = 1355 at

p = .01) indicated that the sample size was more than sufficient for model stability. All standardized loadings were statistically significant and exceeded .69, thereby confirming robust indicator reliability. Composite reliability values ranged from .886 to .915, surpassing the .70 threshold, while average variance extracted values ranged from .525 to .606, exceeding the .50 benchmark and supporting convergent validity. Discriminant validity was also confirmed, as the square roots of the AVEs (.725–.778) were greater than the inter-construct correlations, and HTMT ratios ranged between .425 and .512, well below the conservative .85 criterion. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the six-factor measurement model exhibits excellent fit, reliability, and validity, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural analyses.

All constructs meet standard thresholds for convergent validity (AVE ≥ .50) and internal consistency (CR ≥ .70). Digital Efficiency and Smart Personalization show strong reliability and shared variance with their indicators (CR ≈ .86; AVE ≈ .56–.62). Trusted Security also satisfies both criteria (CR ≈ .81; AVE ≈ .51). Digital Loyalty, with three indicators, attains acceptable reliability (CR ≈ .78) and AVE (.54); if you wish to further strengthen this construct in CFA, consider reviewing the lowest-loading item (v37 = .656) for potential rewording or adding a theoretically coherent indicator, though this is not required given current adequacy.

A one-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant inter-city differences on six of the 39 items, while no differences were observed for the remaining measures (p > .05). Perceptions of digital reliance were higher in Benidorm than in Málaga (F(3,1282) = 2.95, p = .032), suggesting that technological integration is more salient in Benidorm. Institutional trust was significantly greater among respondents in Barcelona compared to those in Benidorm (F(3,1282) = 2.91, p = .033), consistent with Barcelona’s reputation as a leader in smart destination initiatives. Beliefs in the impartiality of information were stronger in Málaga than in Benidorm (F(3,1282) = 3.20, p = .023), pointing to higher confidence in technological neutrality in Málaga. In contrast, concerns about the loss of authenticity in travel experiences were more pronounced in Benidorm than in Málaga (F(3,1282) = 2.94, p = .032). Perceptions of technical failure risks showed the largest divergence: respondents in Málaga reported significantly stronger concerns than those in Barcelona and Valencia, while Benidorm respondents also reported greater concerns than those in Barcelona (F(3,1282) = 4.38, p = .004). Finally, support for encouraging tourists to use applications that promote sustainable behavior was higher in Valencia than in Barcelona (F(3,1282) = 3.14, p = .025). Together, these findings demonstrate that while most attitudes toward digital twin applications are consistent across destinations, meaningful differences emerge in domains of digital reliance, institutional trust, information neutrality, perceived authenticity, technical reliability, and sustainability orientation, underscoring the need for destination-specific implementation strategies

The qualitative interviews with destination managers and stakeholders across four Spanish cities (Barcelona, Málaga, Valencia, and Benidorm) revealed diverse but interconnected perspectives on the potential of digital twins in tourism. Thematic analysis identified five central themes: overtourism, sustainability, challenges, equity, and readiness. Overtourism emerged as the most pressing concern, particularly in Barcelona, where respondents emphasized the potential of digital twins to provide real-time monitoring of visitor density at iconic sites such as Sagrada Familia and Park Güell. This was seen as a means to redistribute flows proactively and reduce congestion. Stakeholders in Valencia reinforced this view, noting the value of virtual simulations for testing crowd management policies before implementation. In Málaga, stakeholders consistently framed digital twins as tools for advancing sustainability. They highlighted their potential in optimizing transport, energy use, and forecasting external shocks such as cruise ship arrivals or extreme weather events. Respondents linked these applications not only to tourism management but also to broader agendas of urban environmental resilience.

Two categories of barriers were consistently identified: technical/financial and ethical/social. In Benidorm, stakeholders stressed the high costs of infrastructure and the dependence on external funding as key constraints. Concerns in Granada focused on data privacy and tourists’ reluctance to share real-time location data, with transparency and trust-building seen as essential for public acceptance. Equity concerns were most pronounced in Valencia, where respondents warned that small businesses and artisans risk exclusion from digital twin systems due to limited resources and digital literacy. While larger firms, residents, and tourists were expected to benefit, the uneven distribution of advantages raised questions of fairness and legitimacy. Perceptions of readiness varied across destinations. Málaga was viewed as the most prepared due to existing smart city infrastructure and previous investments in digital systems. In Barcelona, political support existed but was constrained by slow budget allocations and uncertainty regarding public acceptance. In Benidorm, reliance on external funding was described as a limiting factor. Overall, the interviews demonstrate that digital twins are perceived as both an opportunity and a challenge. They are seen as promising tools for managing overtourism, enhancing sustainability, and fostering innovation in governance. At the same time, financial constraints, ethical concerns, and equity-related risks remain barriers to widespread adoption. Readiness for implementation differs significantly across destinations, underscoring the importance of local governance capacity, sustainable financing, and public trust. The full coding process supporting these results is documented in

Appendix B.

5. Discussion

This study examined tourist attitudes toward digital twin applications in tourism through a large-scale survey (N = 1,286) and qualitative interviews with destination managers and stakeholders across four Spanish cities. By combining quantitative breadth with qualitative depth, the research provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing acceptance and implementation of digital twins in tourism. The results reveal a coherent six-factor measurement model and confirm the relevance of trust, usefulness, ease of use, perceived risks, sustainability attitudes, and awareness familiarity in shaping tourists’ willingness to adopt such applications. At the same time, interviews highlight the opportunities and challenges of digital twin implementation from the perspective of governance, infrastructure, and equity. Together, these findings contribute to the theoretical development of technology acceptance in tourism and offer practical insights for policymakers and destination managers.

5.1. Interpretation of Quantitative Findings

The factor analyses confirmed a robust six-factor structure. Trust Reliability emerged as a cornerstone, with high loadings on items measuring credibility, accuracy, organizational trust, and unbiased information. This factor was a strong predictor of willingness to adopt, confirming H1a. Trust in institutions and confidence in data accuracy remain critical in the tourism domain, where travelers depend on reliable information for safety, planning, and enjoyment. The findings indicate that digital twin adoption will only advance if tourists perceive the underlying systems and their managing organizations as trustworthy. Usefulness Experience and Ease of Use also significantly shaped adoption intentions, supporting H1b. Usefulness was reflected not only in functional benefits such as time saving and planning efficiency but also in experiential enhancements including personalization and cultural enjoyment. Ease of use captured intuitive design, simple navigation, and low support requirements, confirming that digital twins must minimize technical complexity. These findings underscore the importance of aligning digital twins with established technology acceptance constructs, showing that even advanced systems must deliver practical benefits in a user-friendly format. The negative impact of Perceived Risks on adoption intentions supported H1c. Respondents expressed concerns over privacy, surveillance, technical failures, and authenticity loss. These risks resonate with broader societal debates on data use and technological mediation in tourism. Although the relative magnitude of risk perception was lower than the positive effects of trust and usefulness, its significance signals that adoption strategies must directly address risk perceptions through transparency, regulation, and user education.

Sustainability Attitudes and Awareness Familiarity had positive effects, supporting H1d. Respondents with stronger pro-sustainability orientations were more supportive of digital twins, particularly where they were linked to overcrowding control, green tourism, and heritage protection. Awareness and prior familiarity with digital technologies also predicted adoption intentions, demonstrating the role of baseline exposure in reducing uncertainty and fostering acceptance. These results extend the technology acceptance literature by highlighting sustainability and awareness as domain-specific constructs relevant to tourism digitalization. Cross-city comparisons revealed significant differences in attitudes, confirming H2. Benidorm showed higher digital reliance but also greater concerns about authenticity and surveillance. Barcelona respondents reported stronger institutional trust, while Valencia participants expressed higher support for sustainability-oriented applications. Málaga respondents were more concerned about technical failures yet demonstrated confidence in the impartiality of information. These variations highlight that attitudes toward digital twins are not homogeneous but shaped by local context, branding, and infrastructure. Sub-hypotheses were confirmed: Málaga’s relative readiness (H2a), Valencia’s sustainability emphasis (H2b), Barcelona’s stronger institutional trust (H2c), and Benidorm’s authenticity and surveillance concerns (H2d). These results demonstrate that while general acceptance factors are broadly consistent, local differences must guide tailored implementation strategies.

5.2. Interpretation of Qualitative Findings

The qualitative interviews enriched these findings by highlighting contextual dynamics. Across all four cities, overtourism emerged as a central theme. Barcelona stakeholders emphasized the potential of digital twins to monitor real-time density at major attractions and redistribute visitor flows, while Valencia respondents highlighted the potential of virtual simulations for testing policy interventions. These insights align with the survey finding that usefulness and sustainability strongly predict adoption, reinforcing the perception that digital twins can mitigate overtourism. Sustainability was a recurring theme, particularly in Málaga, where stakeholders linked digital twins to resource optimization, energy management, and environmental resilience. The alignment of digital twin applications with sustainability agendas reinforces the survey’s evidence that sustainability attitudes predict acceptance. The interviews confirm that destination managers view digital twins not only as tourism tools but also as components of broader smart city and sustainability strategies. Challenges were framed along two dimensions: technical/financial and ethical/social. In Benidorm, stakeholders stressed dependence on EU and state funding, reflecting limited local capacity. Granada respondents raised concerns about privacy and data sharing, highlighting barriers rooted in trust and social legitimacy. These findings provide context for the survey’s risk perceptions, illustrating that concerns are not abstract but tied to financing structures and ethical dilemmas.

Equity concerns were voiced most strongly in Valencia, where stakeholders warned of the exclusion of small businesses and artisans due to limited digital literacy and resources. This theme resonates with the broader challenge of ensuring that digital innovations do not deepen inequalities. It complements the quantitative finding that awareness familiarity predicts adoption, suggesting that uneven awareness and capacity may reinforce inequities. Readiness varied significantly across destinations. Málaga was viewed as best positioned due to existing infrastructure, Barcelona faced bureaucratic and social constraints despite political will, and Benidorm was constrained by dependence on external funding. These findings echo the survey’s inter-city differences, reinforcing the importance of contextual governance conditions in shaping implementation.

5.3. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

The integration of survey and interview results demonstrates the value of a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative analysis provides statistical validation of constructs and relationships, showing that trust, usefulness, ease of use, risks, sustainability, and awareness predict adoption. Qualitative interviews contextualize these findings, revealing how these constructs are embedded in local governance, infrastructure, and equity dynamics. For example, the survey established that trust is critical for adoption, while interviews clarified that trust depends on transparency, institutional reputation, and data governance. Similarly, the positive role of sustainability attitudes in the survey was echoed by stakeholder narratives linking digital twins to urban resilience and environmental management. The triangulation of tourist perceptions with stakeholder perspectives strengthens the validity of the findings and demonstrates that digital twin adoption depends on both demand-side and supply-side factors.

5.4. Theoretical Contributions

This study advances tourism technology acceptance research in four ways. First, it extends existing models (e.g., TAM, UTAUT) by integrating sustainability attitudes and awareness, thereby incorporating domain-specific drivers of adoption. Second, it demonstrates contextual variation across destinations, showing that adoption is shaped by local infrastructure, branding, and governance, thus contributing to place-based perspectives. Third, by combining quantitative and qualitative approaches, it enhances methodological triangulation and captures the interplay between user perceptions and institutional capacities. Finally, it advances debates on trust and risk by evidencing trust as both a predictor of adoption and a prerequisite for overcoming privacy and surveillance concerns.

5.5. Practical Contributions

The findings also have important implications for European destinations. Adoption depends not only on technical performance but also on governance, equity, and legitimacy, making institutional trust a key condition for success. Effective design requires balancing efficiency and experiential benefits while ensuring robust privacy protections. Aligning digital twins with EU sustainability and resilience agendas—through green tourism, heritage protection, and responsible travel—can further enhance legitimacy. Awareness and familiarity should be strengthened via education and participatory engagement to mitigate skepticism. Finally, destination-specific strategies are essential: Barcelona must balance ambition with acceptance, Málaga can leverage infrastructure, Valencia must ensure inclusivity, and Benidorm requires financial support. These differences highlight the need for tailored, context-sensitive approaches rather than universal models of implementation.

6. Conclusions

This study provided a comprehensive analysis of how tourists and stakeholders perceive the adoption of digital twin applications in tourism, using a mixed-methods design across four major Spanish destinations. The findings established a multidimensional acceptance framework in which trust, usefulness, ease of use, risk perceptions, sustainability attitudes, and awareness emerged as decisive determinants of adoption. Complementary qualitative insights revealed that governance capacity, financial feasibility, and equity concerns critically shape the prospects for implementation. Together, the evidence demonstrates that digital twins are not merely technological artifacts but governance innovations that link tourist demand with institutional supply. The study makes clear that digital twins are viewed ambivalently: they hold strong potential to address overtourism, support sustainability, and enhance governance efficiency, yet they also raise concerns related to surveillance, authenticity, and distributive fairness. Importantly, the integration of quantitative and qualitative results highlights that acceptance is shaped as much by contextual governance arrangements as by individual user attitudes. Successful implementation therefore depends on institutional trust, transparent risk management, and inclusive engagement strategies that ensure equitable benefits across stakeholder groups. By confirming a robust six-factor model of tourist acceptance, uncovering governance, equity, and readiness concerns among stakeholders, and integrating these insights into a multidimensional framework that bridges demand- and supply-side perspectives, this study fully achieved its threefold objectives and provides a comprehensive account of the factors shaping the adoption of digital twin applications in tourism.

Limitations should be acknowledged. The geographic scope was confined to four Spanish destinations, which limits the ability to generalize findings to other cultural or regulatory contexts. The reliance on self-reported perceptions rather than behavioral data constrains the assessment of actual usage patterns. Moreover, the cross-sectional design cannot capture how acceptance may evolve as digital twins mature, regulations are updated, and public debates intensify. Future research should extend the geographic scope to include non-European cases, allowing for comparative cross-cultural analysis of digital twin adoption. Longitudinal studies would be particularly valuable in tracing how perceptions shift over time and whether early skepticism diminishes with increasing familiarity and transparency. Experimental and simulation-based designs could further explore how different governance approaches—such as participatory planning, privacy-by-design protocols, or incentive structures—affect adoption outcomes. Finally, future inquiry should investigate the interplay between digital twins in tourism and parallel developments in other domains, such as urban management or cultural heritage, to assess how integrated digital infrastructures might reshape governance across sectors. In sum, this study shows that digital twins have the potential to become transformative tools in tourism, but their legitimacy and effectiveness will depend on aligning technological ambition with social responsibility, equity, and sustainability. Their role in the future of smart destinations will be determined not by technical capacity alone, but by the ability of institutions to foster trust, inclusiveness, and resilience.

In answering the critical questions that guided this study, the results demonstrate that tourists evaluate digital twins through a balance of trust, usefulness, and risk perceptions; stakeholders perceive them as legitimate when aligned with governance and sustainability goals; and contextual factors such as infrastructure, governance capacity, and destination branding decisively shape these perceptions across cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aleksandra Vujko and Vuk Mirčetić.; methodology, Aleksandra Vujko, Martina Arsić and Tijana Ljubisavljević; software, Vuk Mirčetić.; validation, Aleksandra Vujko and Vuk Mirčetić.; formal analysis Aleksandra Vujko.; investigation, Tijana Ljubisavljević, Martina Arsić and Vuk Mirčetić.; resources, Aleksandra Vujko.; data curation, Vuk Mirčetić.; writing—original draft preparation, Aleksandra Vujko.; writing—review and editing, Aleksandra Vujko.; visualization, Tijana Ljubisavljević.; supervision, Aleksandra Vujko. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Singidunum University (protocol code 139, 28. December 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Part A – Statements on Digital Twin Applications in Tourism

(5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; items randomized in questionnaire to avoid priming and common-method bias)

I am concerned about sharing personal data through the app.

I could easily learn how to use a digital twin app.

I have heard of digital twin technologies in other fields (e.g., engineering).

I would trust the organizations that manage the app.

Such an app could save me time during my trip.

I worry that my location data could be misused.

I would like to learn more about how digital twins can be applied in tourism.

I would be willing to pay a small fee for advanced features.

I fear that using such an app reduces the authenticity of my travel.

I think such apps can protect cultural heritage by managing visitor flows.

Using such an app would not require much technical support.

I would prefer destinations that offer such an app.

Tourists should be encouraged to use apps that promote sustainability.

I believe the design of these apps would be intuitive.

I intend to use digital twin applications in my future travels.

I am familiar with mobile applications used in tourism.

I think depending on technology might reduce spontaneity in tourism.

I feel responsible for using tools that reduce negative impacts.

I have previously used apps that provide real-time destination information.

I would download a digital twin–based app if available.

I would not need prior experience to use such an app.

I consider myself open to trying new tourism technologies.

A digital twin app could help me avoid crowded sites.

I would share my location data if it improved my experience.

I believe tourism technology should balance profit with sustainability.

I think there is a risk of excessive surveillance through smart technologies.

Personalized recommendations from the app would make my trip more memorable.

I feel confident that I could adapt to new digital tools while traveling.

I believe the app would give accurate, real-time data.

Clear instructions would make the app simple to use.

I would recommend such an app to friends and family.

I am aware of the concept of smart cities or smart destinations.

The app could support me in making more sustainable travel choices.

I worry that not all tourists will have equal access to such tools.

I believe such apps will become standard in tourism.

The app would be easy for me to navigate.

I believe the app would present unbiased information.

Interactive features (e.g., 3D maps, AR guides) would enrich my travel experience.

I think tourists are ready and willing to use such applications.

I would trust the app to integrate data from multiple reliable sources.

I am concerned about possible technical failures when using such an app.

I believe tourism destinations increasingly rely on digital tools.

I think destinations need stronger partnerships with tech companies and universities to scale digital twins.

I believe the app would be a credible and professional tool.

It could improve the quality of my trip planning.

I believe digital twins can promote environmentally friendly tourism.

I support the use of technology to reduce overcrowding.

It could enhance my enjoyment of cultural and heritage sites.

I prefer visiting destinations that use sustainable technology.

Part B – Demographics

(5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; items randomized in questionnaire to avoid priming and common-method bias)

Gender

☐ Male ☐ Female ☐ Other / Prefer not to say

Age ☐ < 18 years ☐ 18–24 ☐ 25–34 ☐ 35–44 ☐ 45–54 ☐ 55–64 ☐ 65+

Highest level of education completed

☐ Primary school ☐ Secondary school ☐ Vocational / Technical college ☐ University degree (undergraduate/graduate) ☐ Postgraduate degree (master’s/doctorate)

Occupation / Status ☐ Student ☐ Employed ☐ Self-employed ☐ Unemployed

☐ Retired ☐ Other

Country of residence [Open text field]

Frequency of travel ☐ Less than once a year ☐ 1–2 times per year ☐ 3–5 times per year ☐ More than 5 times per year

Primary digital device used while traveling ☐ Smartphon ☐ Tablet ☐ Laptop ☐ Other

Appendix B – Interview Guide, Raw Data, and Coding Process

A1. Interview Guide

The semi-structured interview guide was developed around five themes derived from the literature (overtourism, sustainability, challenges, equity, and readiness). Fourteen guiding questions were used:

Theme 1: Familiarity with Digital Twins

How familiar are you with the concept of digital twins in tourism or urban management?

Have you or your organization previously worked with smart city or digital simulation technologies?

Theme 2: Perceived Benefits of Digital Twins

In your opinion, what benefits could digital twin technology bring to tourism management?

How could digital twins contribute to addressing overtourism and congestion?

Do you see potential for improving sustainability or cultural heritage preservation?

Theme 3: Challenges and Barriers

What are the main challenges in adopting digital twin solutions (technical, financial, organizational)?

How do you perceive the issue of data privacy and ethics in relation to digital twins?

What limitations or risks do you foresee for your destination?

Theme 4: Stakeholder Perspectives

Which stakeholder groups (tourists, residents, businesses, public authorities) would benefit the most from digital twin applications?

Do you think there are groups that could be disadvantaged or excluded?

How can conflicts of interest between stakeholders be managed?

Theme 5: Future Readiness

How ready is your destination to adopt and implement digital twin technologies?

What resources or support (funding, partnerships, policy) are necessary for successful implementation?

Do you think tourists are ready and willing to use such applications?

A2. Raw Data (Selected Excerpts)

Theme 1 – Familiarity

(Manager, Valencia): “I know digital twins mainly from urban planning. In tourism, the idea is newer, but we see potential to simulate visitor flows, test policies virtually, and then apply them with less risk.”

Theme 2 – Benefits

(Manager, Barcelona): “Our main challenge is overcrowding at Sagrada Familia and Park Güell. A digital twin could allow us to monitor real-time visitor density and redirect flows before congestion occurs.”

(Manager, Málaga): “We see digital twins as a tool to enhance sustainability. They can help optimize transport, energy use, and even predict how weather or cruise ship arrivals will impact the city.”

Theme 3 – Challenges

(Manager, Benidorm): “Funding is a major obstacle. Advanced simulation requires infrastructure and data integration that small municipalities often cannot afford without state or EU support.”

(Manager, Granada): “Data privacy is another issue. Tourists may not feel comfortable sharing real-time location data. We need transparent policies and strong communication to build trust.”

Theme 4 – Stakeholder Perspectives

(Manager, Valencia): “Tourists benefit through better experiences, locals through reduced congestion, and businesses through more efficient marketing. But small local businesses could be left behind if they lack digital skills or resources to join the system.”

Theme 5 – Future Readiness

(Manager, Málaga): “We already have elements of a smart city infrastructure. The step toward digital twins is logical, but we need stronger partnerships with tech companies and universities to scale it.”

(Manager, Barcelona): “Politically, there is interest, but implementation is slower. Public acceptance and budget allocation are the main hurdles.”

A3. Coding Process

Step 1 – Open Coding

Familiarity: knowledge from urban planning, novelty in tourism, potential for simulation, risk reduction.

Benefits: overcrowding at iconic sites, real-time density monitoring, redirection of tourists, sustainability optimization, transport and energy management, predicting external shocks.

Challenges: lack of funding, expensive infrastructure, need for EU/state support, data privacy concerns, lack of tourist trust, importance of transparent communication.

Stakeholders: tourists gain better experience, residents benefit from less congestion, big businesses gain efficiency, small businesses risk exclusion.

Readiness: smart city infrastructure exists, partnerships with tech and academia needed, political interest present, slow implementation, public acceptance uncertain, funding hurdles.

Step 2 – Categories (Grouped Codes)

Overtourism management: overcrowding, redirection, monitoring density.

Sustainability: optimizing transport, energy, weather impacts, environmental efficiency.

Technical/financial barriers: cost of infrastructure, funding dependence.

Ethical barriers: privacy concerns, trust, transparency.

Equity issues: small businesses excluded, uneven digital skills.

Governance & readiness: political will, public acceptance, existing infrastructure, partnerships needed.

Step 3 – Mapping to Central Themes

Overtourism: Barcelona case of Sagrada Familia and Park Güell; Valencia’s interest in simulating visitor flows.

Sustainability: Málaga’s emphasis on optimizing resources and predicting external shocks.

Challenges: Benidorm’s funding concerns; Granada’s data privacy and trust issues.

Equity: Valencia’s warning that small businesses could be left out.

Readiness: Málaga’s existing infrastructure and partnership needs; Barcelona’s political interest vs. slow implementation.

Step 4 – Interpretive Summary

This interview set reveals that stakeholders perceive digital twins as both promising and challenging. Barcelona emphasizes overtourism control, Málaga links digital twins to sustainability and smart infrastructure, while Benidorm and Granada highlight barriers of funding and data privacy. Valencia points to equity concerns, stressing that while tourists and large firms may benefit, small businesses risk exclusion. Across all destinations, readiness depends on governance capacity, funding, and public acceptance.

References

- Chang, G.; Wang, K.; Voda, M. Does Tourism Development Become an Accelerator of Low-Carbon Transition? The Moderating Role of Digital Economy and Green Finance. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 385, 125664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, H.; Raj, S. Digitalization and Digital Transformation in the Tourism Industry: A Bibliometric Review and Research Agenda. Tourism Review 2025, 80, 894–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Miao, L. Digital Transformation and Green Finance Efficiency of Tourism Enterprises: The Effect of Credit Ratings. International Review of Financial Analysis 2025, 106, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, Z. Wilds to Wonders: Digital Empowerment and the Vitality of Rural Tourism in Z Village. Journal of Rural Studies 2025, 120, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, I.; Zorgati, H.; Bouzaabia, R. The Impact of Immersive Virtual Reality Tour on Visit Intentions: The Moderating Role of Cybersickness and Destination Preference. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, M. A Method for Overtourism Optimisation for Protected Areas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2025, 49, 100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda-Robles, C.; Galindo-Pérez-de-Azpillaga, L.; Armario-Pérez, P. The Sustainable Management of Overtourism via User Content. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2025, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, S. Exploring the Impact of AI-Enhanced Virtual Tourism on Tourists' Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Model Perspective. Acta Psychologica 2025, 253, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, G. Global Perspectives on Environmental Policy Innovations: Driving Green Tourism and Consumer Behavior in Circular Economy. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 374, 124138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Camino, F.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Jara Alba, C.A. Rural Tourism Initiatives and Their Relationship to Collaborative Governance and Perceived Value: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2024, 34, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.M.; Haykel, I.; Cheung, K.; Matalon, T. Navigating the Complexities of AI and Digital Governance: The 5W1H Framework. Journal of Responsible Technology 2025, 23, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, B.W. Dynamic Construction and Maintenance of Destination Competitiveness Based on Interpretable Machine Learning. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2025, 37, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, M.; Dutta, H.; Minerva, R.; Crespi, N.; Raza, S.M.; Herath, M. Global Perspectives on Digital Twin Smart Cities: Innovations, Challenges, and Pathways to a Sustainable Urban Future. Sustainable Cities and Society 2025, 126, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, H. Concept and Framework of Digital Twin Human Geographical Environment. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 373, 123866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Budhiraja, I.; Singh, A.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Hassan, M.M. Energy Efficient Resource Allocation and Trajectory Optimization Method for Secure Digital Twin-Enabled UAV-Assisted MEC in 6G Networks. Computer Networks 2025, 272, 111679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Barata, J. Mirroring the Regional Food Supply Chain: A Multidimensional Digital Twin for Estrela Geopark. Sustainable Futures 2025, 10, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhardono, S.; Fitria, L.; Prayogo, W.; Lee, C.-H.; Suryawan, I.W.K. Enhancing Community Engagement with Digital Twins: Technological Adoption in Marine Debris Management. Journal of Urban Management. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Hasan, R.; Alsanad, A.; Alhogail, A.; Gumaei, A.H. Multiple Knowledge Depiction of Digital Twin-Driven Circular Economy: Concepts, Integrated Advanced Technologies, Triple Bottom Line of Smart Construction, and Exploratory Case Studies. Journal of Engineering Research. [CrossRef]

- Rahmadian, E.; Feitosa, D.; Virantina, Y. Digital Twins, Big Data Governance, and Sustainable Tourism. Ethics and Information Technology 2023, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrovali, G.; Tzanis, G.; Morfoulaki, M. Sustainable Tourism through Digitalization and Smart Solutions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yeo, J.; Son, M. Exploring Public Acceptance of Climate Technologies: A Study on Key Influences in South Korea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenesei, Z.; Kökény, L.; Ásványi, K.; et al. The Central Role of Trust and Perceived Risk in the Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles in an Integrated UTAUT Model. European Transport Research Review 2025, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirčetić, V.; Mihić, M. Smart Tourism as a Strategic Response to Challenges of Tourism in the Post-COVID. Sustainable Business Management and Digital Transformation: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-COVID Era. [CrossRef]

- Mirčetić, V.; Mihić, M. Developing Smart Tourism as a Strategic Approach to Tourism Challenges in the Post-COVID Era. SYMORG.

- Keeley, A.R.; Koo, K.; Chapman, A.; Managi, S. Psychological and Socio-Economic Drivers of Public Acceptance for Direct Air Capture and Utilization Technology. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 519, 145962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The Use of Digital Twins to Address Smart Tourist Destinations’ Future Challenges. Platforms 2024, 2, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Lu, J.; Zhou, S. A Review of Digital Twin Capabilities, Technologies, and Applications Based on the Maturity Model. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2024, 62(A), 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, C.; Ababneh, R.F.; Alkhatib, L.A.; Saqallah, D.; Al Koutoubi, R.; Aljaghoub, H.; Alami, A.H.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A.G. Data-Driven Digital Twin for Fault Detection in Compressed Air Energy Storage Systems: Design and Experimental Validation. Energy 2025, 336, 138401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Qu, H.; Tsang, W.-S.L.; Lam, C.-W.R. The Influence of Smart Tourism Applications on Perceived Destination Image and Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Information Search Behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 46, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.B.; Soardi, G.; Attanasio, A.; Frazzon, E.M. Applying Theory of Constraints (TOC) to Digital Twins: Simulation and Managerial Outputs. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Goh, G.G.G.; Lee, Y.L.-E.; Zeb, A. To Be Digital Is to Be Sustainable—Tourist Perceptions and Tourism Development Foster Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orejon-Sanchez, R.D.; Crespo-Garcia, D.; Andres-Diaz, J.R.; Gago-Calderon, A. Smart Cities’ Development in Spain: A Comparison of Technical and Social Indicators with Reference to European Cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 81, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaire, J.A.; Galí, N.; Coromina, L. Evaluating Tourism Scenarios within the Limit of Acceptable Change Framework in Barcelona. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2024, 5, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyamiyan Gorji, A.; Hosseini, S.; Seyfi, S.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortes Macías, R.; Mena Navarro, A. ‘Málaga for Living, Not Surviving’: Resident Perceptions of Overtourism, Social Injustice and Urban Governance. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2026, 39, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, S.; Lavanga, M.; Koens, K. Using Adaptive Cycles and Panarchy to Understand Processes of Touristification and Gentrification in Valencia, Spain. Tourism Management 2025, 106, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Martínez, J.D.; McCabe, S.; Fernández-Morales, A. Assessing the Contribution of Different Markets in Combatting Destination Seasonality: The Case of Benidorm, Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2023, 29, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauttonen, J.; Rousi, R.; Alamäki, A. Trust and Acceptance Challenges in the Adoption of AI Applications in Health Care: Quantitative Survey Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e65567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanov, B.; Duenas Cid, D.; Leets, P. State versus Technology: What Drives Trust in and Usage of Internet Voting, Institutional or Technological Trust? Government Information Quarterly 2025, 42, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebab, M. Travel App Adoption Intentions: Extending the Technology Acceptance Model with Trust. Marketing Science & Inspirations 2025, 20, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, J.; Osho, J.; Wooley, A.; Harris, G. Do You Trust Digital Twins? A Framework to Support the Development of Trusted Digital Twins through Verification and Validation. International Journal of Production Research 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Funahashi, T.; Biljecki, F. Assessing Governance Implications of City Digital Twin Technology: A Maturity Model Approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 204, 123409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, D. Impact of Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness of Humanoid Robots on Students’ Intention to Use. Acta Psychologica 2025, 258, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şeker, F.; Kadirhan, G.; Erdem, A. The Factors Affecting Tourism Mobile Apps Usage. Tourism & Management Studies 2023, 19, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Zhiqiang, M.; Li, M.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S. The Mediating Effects of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use on Nurses’ Intentions to Adopt Advanced Technology. BMC Nursing 2025, 24, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Shaw, R. Risk Perception and Adoption of Digital Innovation in Stock Trading: A Behavioral Study. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Pavón, S.; López-Mosquera, N.; Sánchez González, M.J. The Impact of Technology Risks and Innovation on Smart Tourism Destination Management. Anatolia 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkhangplu, A.; Suwanthep, D. Travel Intention to Destination via Virtual Tour: Role of Perceived Travel Risks and Behavioral. Cogent Social Sciences 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, E.; Guo, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J. The Role of Technology Belief, Perceived Risk and Initial Trust in Users’ Acceptance of Urban Air Mobility: An Empirical Case in China. Multimodal Transportation 2024, 3, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Wang, B.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Xu, T. Navigating Ethical Decision-Making in Digital Transformation: Ethical Climate, Digital Competence, and Person–Organization Fit in China’s Banking Sector. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications 2025, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Zonah, S. Revolutionising Heritage Interpretation with Smart Technologies: A Blueprint for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, H.; Barboza, M.; Nogueira, C. Perceptions and Behaviors Concerning Tourism Degrowth and Sustainable Tourism: Latent Dimensions and Types of Tourists. Sustainability 2025, 17, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujko, A.; Knežević, M.; Arsić, M. The Future Is in Sustainable Urban Tourism: Technological Innovations, Emerging Mobility Systems and Their Role in Shaping Smart Cities. Urban Science 2025, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Shen, M.; Yi, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S. Extending X-Reality Technologies to Digital Twin in Cultural Heritage Risk Management: A Comparative Evaluation from the Perspective of Situation Awareness. Heritage Science 2024, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, N.; Vujko, A.; Stanišić, N.; Ljubisavljević, T.; Lunić, D. Digital Hospitality as a Socio-Technical System: Aligning Technology and HR to Drive Guest Perceptions and Workforce Dynamics. World 2025, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudu, P.N.; Mishra, V. Toward Smart and Green: A Sustainable IT-HRM Framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2025, 218, 124201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cristòfol, F.J. Strategic Management of the Malaga Brand through Open Innovation: Tourists and Residents’ Perception. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soursou, V.; Campo, J.; Picó, Y. Spatio-Temporal Variation and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics along the Touristic Beaches of a Mediterranean Coast Transect (Valencia Province, East Spain). Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 354, 120315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandajs, F.; Russo, A.P. Smarter City, Less Just Destination? Mobilities and Social Gaps in Barcelona. Journal of Place Management and Development 2023, 16, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Zayas, A.; Gómez-Carmona, D.; López Sánchez, J.A. Smart Tourism Destinations Really Make Sustainable Cities: Benidorm as a Case Study. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2023, 9, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, A.; Alepis, E. Smart Tourism: State of the Art and Literature Review for the Last Six Years. Array 2020, 6, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. How Do Smart Tourism Experiences Affect Visitors’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior? Influence Analysis of Nature-Based Tourists in Taiwan. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, Q.; Pan, C. A Credibility Evaluation Method for Digital Twin Based on Improved Evidence Theory. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2025, 143, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Sustainable Tourism at Nature-Based Cultural Heritage Sites: Visitor Density and Its Influencing Factors. npj Heritage Science 2025, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|