Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Virus Stocks

2.3. Infections

2.4. Treatment with IFN

2.5. Endogenous Antiviral Response to Infection

2.6. Transcriptomic Analysis of IFN-Treated NHSK-1 Cells

2.7. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

2.8. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

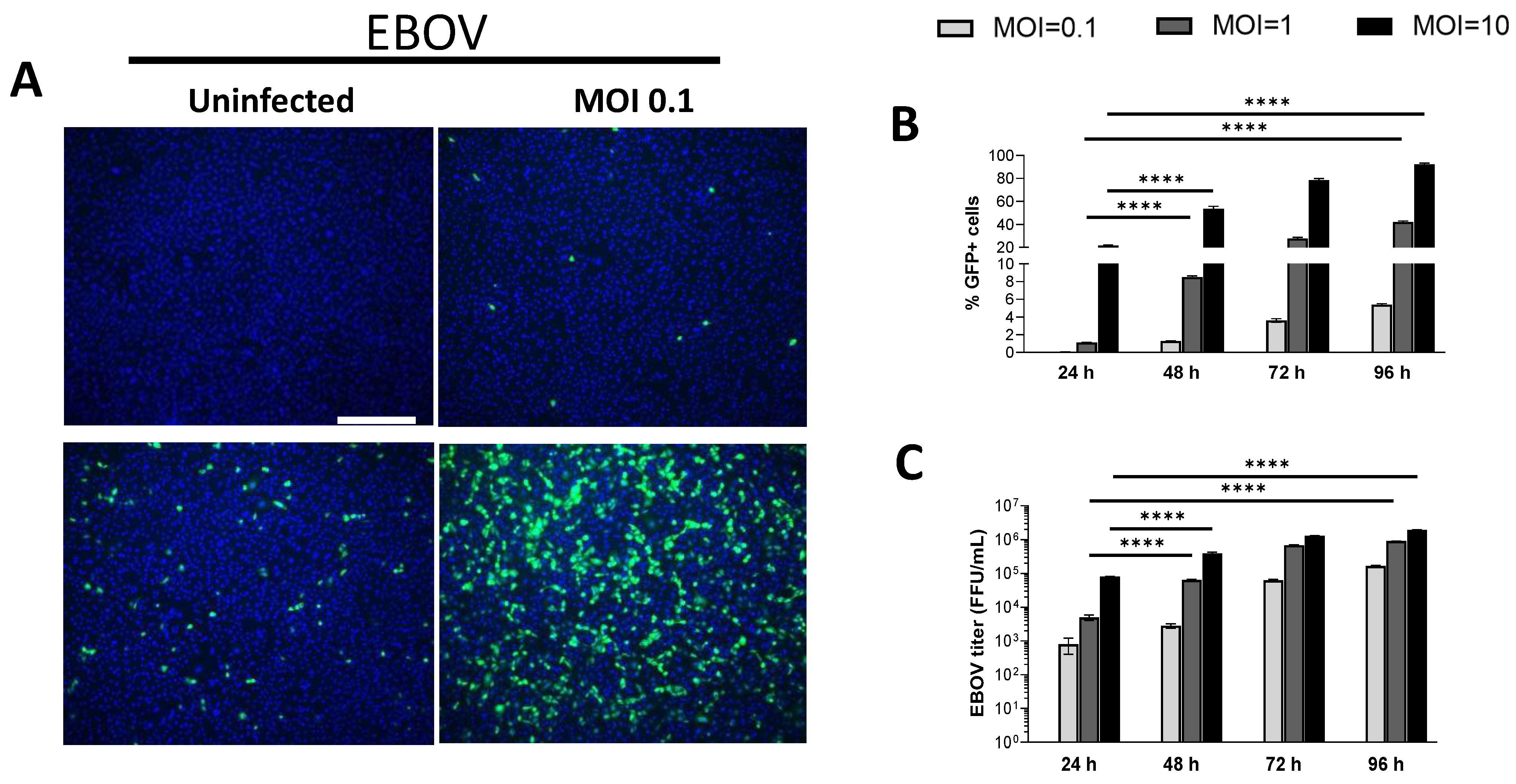

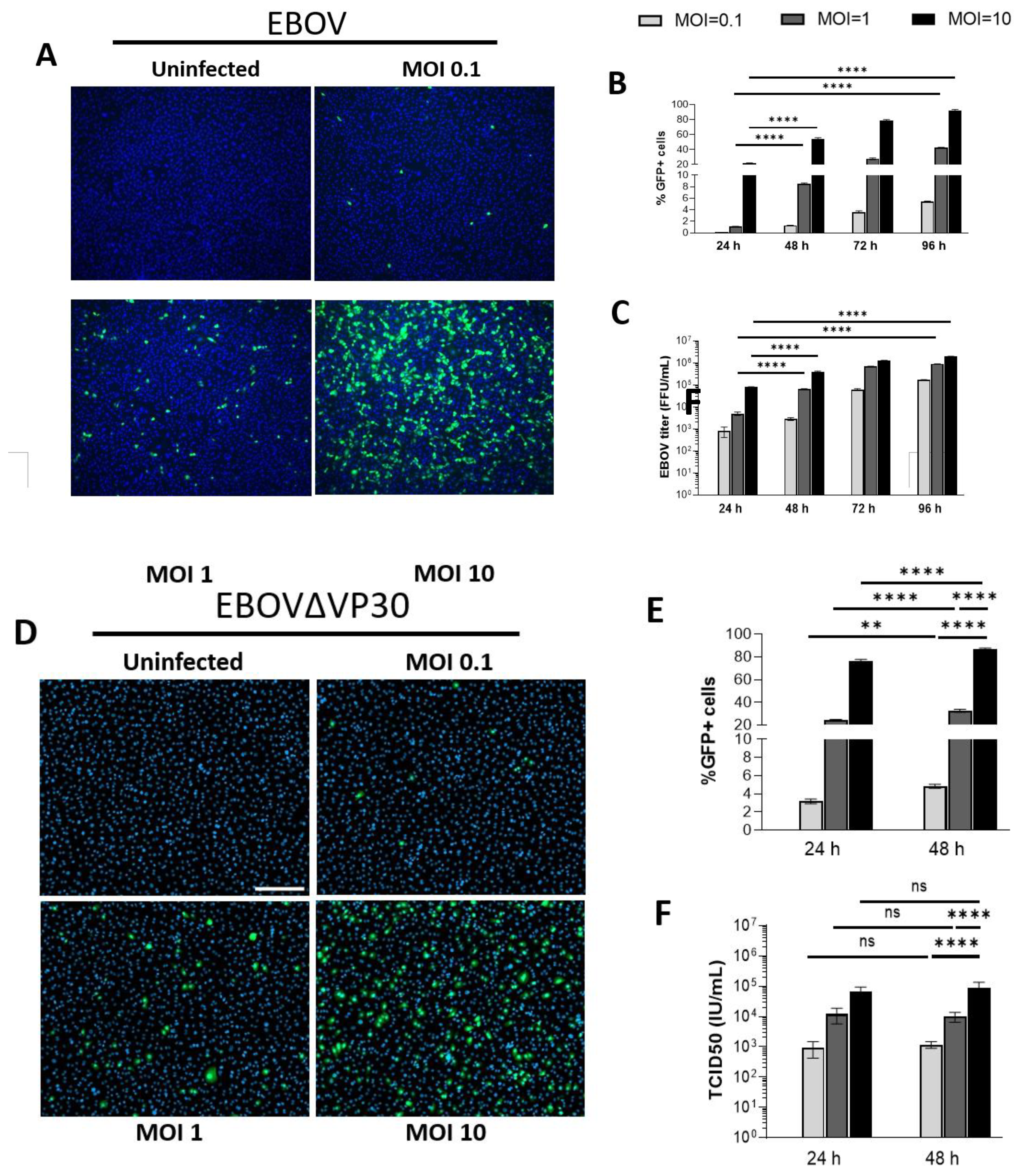

3.1. Human Keratinocytes Support EBOV and EBOVΔVP30 Infection

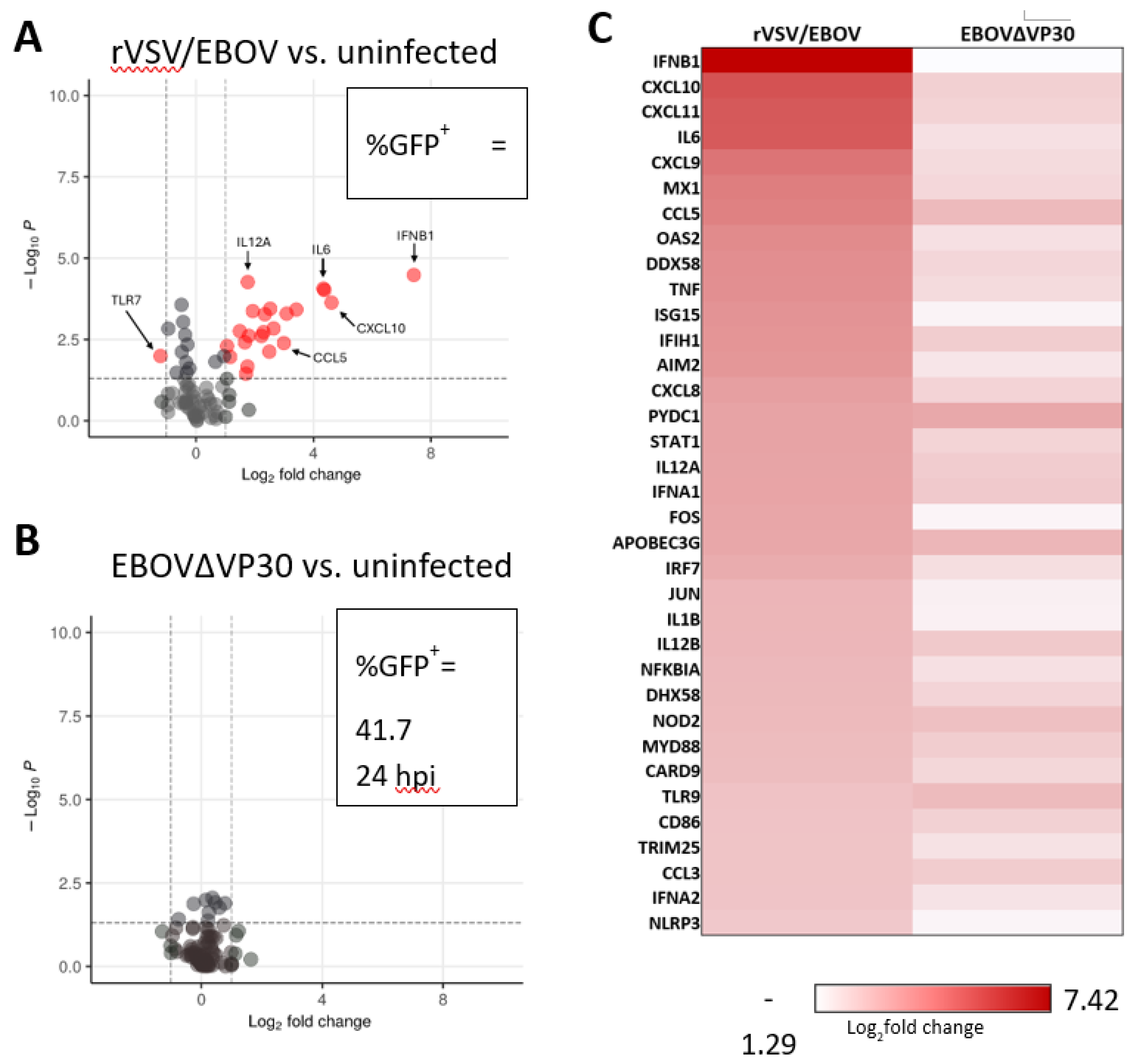

3.2. EBOVΔVP30 Infection Does Not Stimulate Innate Antiviral Responses in Human Keratinocytes

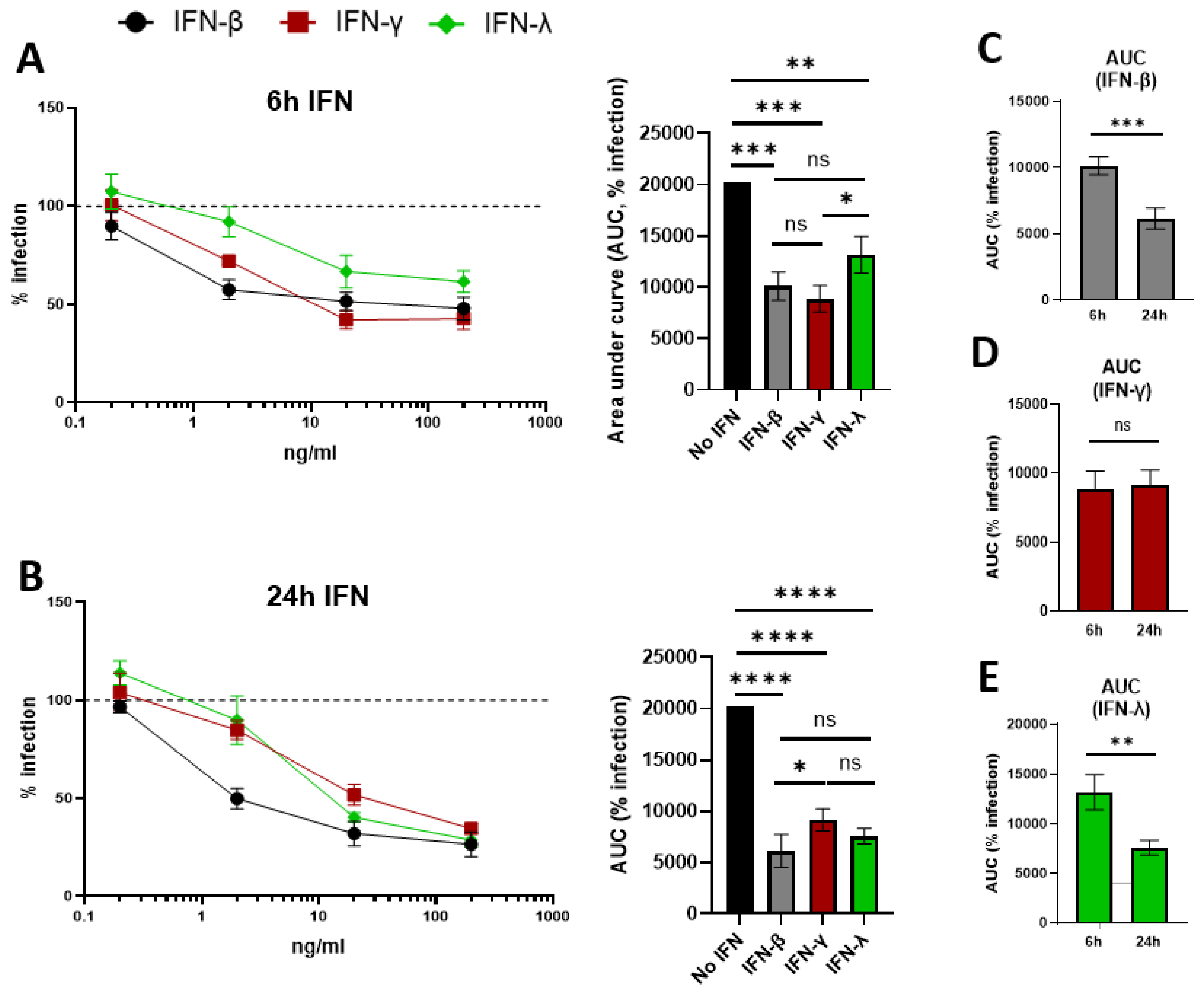

3.3. Exogenous Treatment with IFN-β, IFN-γ, and IFN-λ Inhibits EBOV Replication in Human Keratinocytes

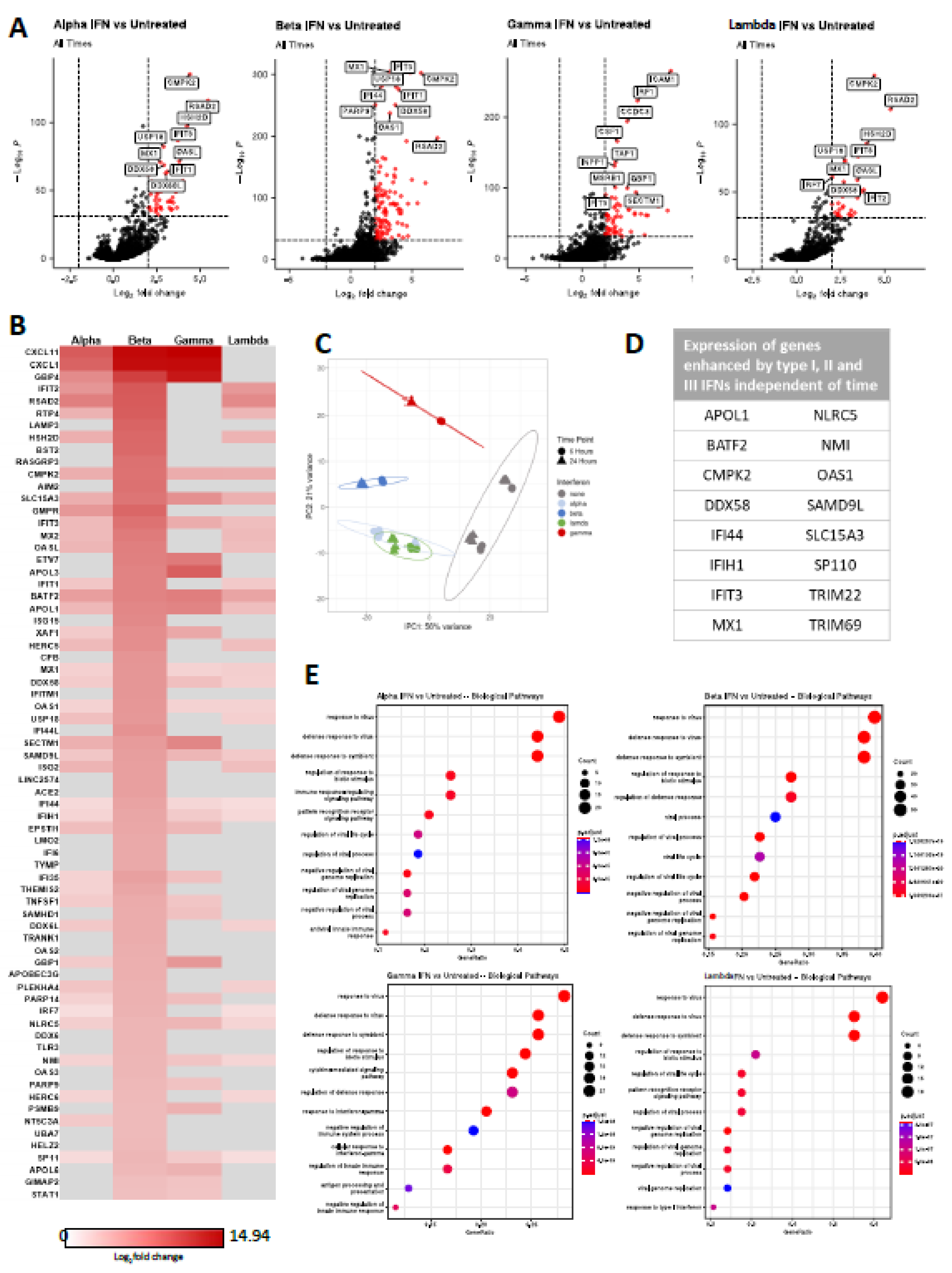

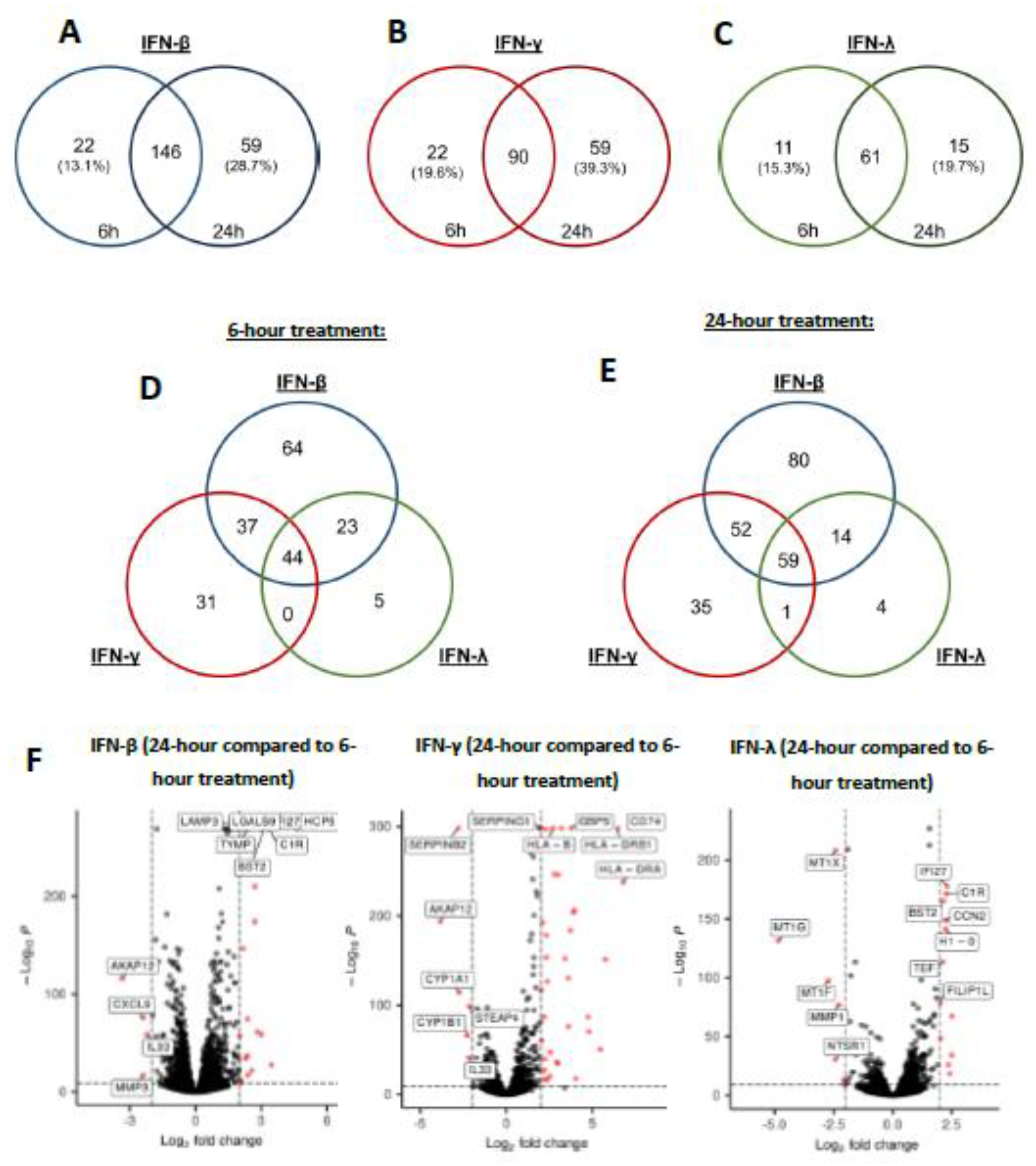

3.4. Interferons Elicit a Range of Overlapping and Unique ISGs in Human Keratinocytes

3.4. IFN Elicits Differential Gene Expression Patterns Between 6- and 24-Hours of Treatment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBOV | Orthoebolavirus zairense or Zaire Ebolavirus |

| EBOVΔVP30 | EBOV lacking expression of VP30 |

| rVSV/EBOV GP | Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus encoding EBOV GP |

| IFN | Interferon |

| NHSK-1 | Normal Human Skin Keratinocyte 1 |

| ISG | Interferon stimulated gene |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| NHP | Non-human primate |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EVD | Ebola virus disease |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| IFNAR | Interferon-α/β receptor |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| IRF | Interferon regulatory factor |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| RT-qPCR | Real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| CLE | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus 1 |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

References

- Leroy, E.M.; Gonzalez, J.-P.; Baize, S. Ebola and Marburg haemorrhagic fever viruses: major scientific advances, but a relatively minor public health threat for Africa. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 964–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyer, J.; Grobbelaar, A.; Blumberg, L. Ebola Virus Disease: History, Epidemiology and Outbreaks. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2015, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izudi, J.; Bajunirwe, F. Case fatality rate for Ebola disease, 1976–2022: A meta-analysis of global data. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2024, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, H.; Sprecher, A.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1832–1842. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMra1901594. [CrossRef]

- Matson, M.J.; Chertow, D.S.; Munster, V.J. Ebola Virus Disease: Uniquely Challenging Amongst the Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkoghe, D.; Leroy, E.M.; Toung-Mve, M.; Gonzalez, J.P. Cutaneous manifestations of filovirus infections. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012, 51, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, A.; Bowen, E.T.W.; Platt, G.S.; McArdell, L.B.; Simpson, D.I.H. The pathology of experimental Ebola virus infection in monkeys. J. Pathol. 1978, 125, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, N.; Yadav, P.; Patil, D. Ebola virus outbreak preparedness plan for developing Nations: Lessons learnt from affected countries. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021, 14, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, S.; Nsio, J.; Camacho, A.; Kitenge, R.; Coulborn, R.M.; Gignoux, E.; Johnson, J.; Sterk, E.; Musenga, E.M.; Mustafa, S.H.B.; et al. Effectiveness of rVSV-ZEBOV vaccination during the 2018–20 Ebola virus disease epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a retrospective test-negative study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Restrepo, A.M.; Camacho, A.; Longini, I.M.; Watson, C.H.; Edmunds, W.J.; Egger, M.; Carroll, M.W.; Dean, N.E.; Diatta, I.; Doumbia, M.; et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!). Lancet 2017, 389, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukarev, G.; Callendret, B.; Luhn, K.; Douoguih, M. A two-dose heterologous prime-boost vaccine regimen eliciting sustained immune responses to Ebola Zaire could support a preventive strategy for future outbreaks. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- nbsp; Pascal, K. E.; Dudgeon, D.; Trefry, J.C.; Anantpadma, M.; Sakurai, Y.; Murin, C.D.; Turner, H.L.; Fairhurst, J.; Torres, M.; Rafique, A.; et al. Development of Clinical-Stage Human Monoclonal Antibodies That Treat Advanced Ebola Virus Disease in Nonhuman Primates. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, S612–S626. [Google Scholar]

- Corti, D.; Misasi, J.; Mulangu, S.; Stanley, D.A.; Kanekiyo, M.; Wollen, S.; Ploquin, A.; Doria-Rose, N.A.; Staupe, R.P.; Bailey, M.; et al. Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody. Science 2016, 351, 1339–1342. Available from: https://www.science.org. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulangu, S.; Dodd, L.E.; Davey, R.T., Jr.; Tshiani Mbaya, O.; Proschan, M.; Mukadi, D.; Lusakibanza Manzo, M.; Nzolo, D.; Tshomba Oloma, A.; Ibanda, A.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Ebola Virus Disease Therapeutics. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Rewar, S.; Mirdha, D. Transmission of Ebola Virus Disease: An Overview. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2015, 80, 444–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, D.G.; Towner, J.S.; Dowell, S.F.; Kaducu, F.; Lukwiya, M.; Sanchez, A.; Nichol, S.T.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E. Assessment of the Risk of Ebola Virus Transmission from Bodily Fluids and Fomites. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S142–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gire, S.K.; Goba, A.; Andersen, K.G.; GSealfon, R.S.; Park, D.J.; Kanneh, L.; et al. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak [Internet]. Available from: https://www.science.org.

- Ericson, A.D.; Claude, K.M.; Vicky, K.M.; Lukaba, T.; Richard, K.O.; Hawkes, M.T. Detection of Ebola virus from skin ulcers after clearance of viremia. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 131, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T.M.; Mehta, A.K.; Davey, R.T., Jr.; Liddell, A.M.; Wolf, T.; Vetter, P.; Schmiedel, S.; Grünewald, T.; Jacobs, M.; Arribas, J.R.; et al. Clinical Management of Ebola Virus Disease in the United States and Europe. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 636–646. [Google Scholar]

- Twenhafel, N.A.; Mattix, M.E.; Johnson, J.C.; Robinson, C.G.; Pratt, W.D.; Cashman, K.A.; Wahl-Jensen, V.; Terry, C.; Olinger, G.G.; Hensley, L.E.; et al. Pathology of Experimental Aerosol Zaire Ebolavirus Infection in Rhesus Macaques. Veter- Pathol. 2013, 50, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, S.R.; Shieh, W.J.; Greer, P.W.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Ferebee, T.; Katshitshi, J.; et al. A Novel Immunohistochemical Assay for the Detection of Ebola Virus in Skin: Implications for Diagnosis, Spread, and Surveillance of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever [Internet]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/179/Supplement_1/S36/882144.

- Messingham, K.N.; Richards, P.T.; Fleck, A.; Patel, R.A.; Djurkovic, M.; Elliff, J.; et al. V I R O L O G Y Multiple cell types support productive infection and dynamic translocation of infectious Ebola virus to the surface of human skin [Internet]. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11. Available from: https://www.science.org.

- Richards, P.T.; Fleck, A.M.; Patel, R.; Fakhimi, M.; Bohan, D.; Geoghegan-Barek, K.; Honko, A.N.; Stolte, A.E.; Plescia, C.B.; Messingham, C.O.; et al. Ebola virus’ hidden target: virus transmission to and infection of skin. J. Virol. 2025, e0130025. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jvi.01300-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, R.; Dejarnac, O.; Wichit, S.; Ekchariyawat, P.; Neyret, A.; Luplertlop, N.; Perera-Lecoin, M.; Surasombatpattana, P.; Talignani, L.; Thomas, F.; et al. Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8880–8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomão, N.G.; Araújo, L.; de Souza, L.J.; Young, A.L.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, C.; Basílio-De-Oliveira, R.P.; de Carvalho, J.J.; Nunes, P.C.G.; Amorim, J.F.d.S.; Barbosa, D.V.D.S.; et al. Chikungunya virus infection in the skin: histopathology and cutaneous immunological response. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1497354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiamba, E.W.; Goodier, M.R.; Clarke, E. Immune responses to human papillomavirus infection and vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1591297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Viejo-Borbolla, A. Pathogenesis and virulence of herpes simplex virus. Virulence 2021, 12, 2670–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerimele, F.; Curreli, F.; Ely, S.; Friedman-Kien, A.E.; Cesarman, E.; Flore, O. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Can Productively Infect Primary Human Keratinocytes and Alter Their Growth Properties. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konde, M.K.; Baker, D.P.; Traore, F.A.; Sow, M.S.; Camara, A.; Barry, A.A.; Mara, D.; Barry, A.; Cone, M.; Kaba, I.; et al. Interferon β-1a for the treatment of Ebola virus disease: A historically controlled, single-arm proof-of-concept trial. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Rhein, B.; Powers, L.S.; Rogers, K.; Anantpadma, M.; Singh, B.K.; Sakurai, Y.; Bair, T.; Miller-Hunt, C.; Sinn, P.; A Davey, R.; et al. Interferon-γ Inhibits Ebola Virus Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.J.; Shtanko, O.; Vijay, R.; Mallinger, L.N.; Joyner, C.J.; Galinski, M.R.; Butler, N.S.; Maury, W. Acute Plasmodium Infection Promotes Interferon-Gamma-Dependent Resistance to Ebola Virus Infection. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 4041–4051.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, D.; Zanoni, I. Interferons in health and disease. Cell. 2025, 188, 4480–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazewski, C.; Perez, R.E.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Type I Interferon (IFN)-Regulated Activation of Canonical and Non-Canonical Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R. The Role of Structure in the Biology of Interferon Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and Distinct Functions of Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type i interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011, 472, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W.; MacDuff, D.A.; Imanaka, N.; Gainey, M.D.; Shrestha, B.; Eitson, J.L.; Mar, K.B.; Richardson, R.B.; Ratushny, A.V.; Litvak, V.; et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 2014, 505, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, D.F. Type I Interferon as a Link Between Innate and Adaptive Immunity through Dendritic Cell Stimulation. Leuk. Lymphoma 2004, 45, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, M.W.; Plumb, A.W.; Niss, K.; Lahl, K.; Brunak, S.; Johansson-Lindbom, B. Type I Interferons Promote Germinal Centers Through B Cell Intrinsic Signaling and Dendritic Cell Dependent Th1 and Tfh Cell Lineages. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 932388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Ashkar, A.A. The Dual Nature of Type I and Type II Interferons. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, C.P.; Crow, M.K. Type I interferons in health and disease: molecular aspects and clinical implications. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 2537–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnier, J.L.; Kahlenberg, J.M. The Role of Cutaneous Type I IFNs in Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore, S.; Corinti, S.; La Placa, M.; Didona, B.; Girolomoni, G. Interferon-γ promotes exaggerated cytokine production in keratinocytes cultured from patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1998, 101, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D.; Yao, X.; Zhao, M.; Kumari, S.; Lu, J.; Yu, D.; Lu, Q. Dysregulation in keratinocytes drives systemic lupus erythematosus onset. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 22, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tsoi, L.C.; Sarkar, M.K.; Xing, X.; Xue, K.; Uppala, R.; et al. IFN-γ enhances cell-mediated cytotoxicity against keratinocytes via JAK2/STAT1 in lichen planus [Internet]. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galão, R.P.; Wilson, H.; Schierhorn, K.L.; Debeljak, F.; Bodmer, B.S.; Goldhill, D.; Hoenen, T.; Wilson, S.J.; Swanson, C.M.; Neil, S.J.D. TRIM25 and ZAP target the Ebola virus ribonucleoprotein complex to mediate interferon-induced restriction. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, A.; Pitha, P.M.; Harty, R.N. ISG15 inhibits Ebola VP40 VLP budding in an L-domain-dependent manner by blocking Nedd4 ligase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 3974–3979. Available from: www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/. [CrossRef]

- Wrensch, F.; Karsten, C.B.; Gnirß, K.; Hoffmann, M.; Lu, K.; Takada, A.; Winkler, M.; Simmons, G.; Pöhlmann, S. Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein–Mediated Inhibition of Host Cell Entry of Ebolaviruses. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, S210–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Halfmann, P.J.; Hill-Batorski, L.; Ozawa, M.; Lopes, T.J.S.; Neumann, G.; Schoggins, J.W.; Rice, C.M.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of interferon-stimulated genes that attenuate Ebola virus infection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckenhuber, M.; Seufert, I.; Müller-Ott, K.; Mallm, J.-P.; Klett, L.C.; Knotz, C.; Hechler, J.; Kepper, N.; Erdel, F.; Rippe, K. Epigenetic signals that direct cell type–specific interferon beta response in mouse cells. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202201823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervolaraki, K.; Talemi, S.R.; Albrecht, D.; Bormann, F.; Bamford, C.; Mendoza, J.L.; Garcia, K.C.; McLauchlan, J.; Höfer, T.; Stanifer, M.L.; et al. Differential induction of interferon stimulated genes between type I and type III interferons is independent of interferon receptor abundance. PLOS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aybey, B.; Brors, B.; Staub, E. Expression signatures with specificity for type I and II IFN response and relevance for autoimmune diseases and cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, K.K.; Reed, T.J.; Yang, J.; Cristea, I.M. Differential Contributions of Interferon Classes to Host Inflammatory Responses and Restricting Virus Progeny Production. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 3249–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourronc, F.A.; Robertson, M.M.; Herrig, A.K.; Lansdorp, P.M.; Goldman, F.D.; Klingelhutz, A.J. Proliferative defects in dyskeratosis congenita skin keratinocytes are corrected by expression of the telomerase reverse transcriptase, TERT, or by activation of endogenous telomerase through expression of papillomavirus E6/E7 or the telomerase RNA component, TERC. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scorza, B.M.; Wacker, M.A.; Messingham, K.; Kim, P.; Klingelhutz, A.; Fairley, J.; Wilson, M.E. Differential Activation of Human Keratinocytes by Leishmania Species Causing Localized or Disseminated Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, P.; Kim, J.H.; Ebihara, H.; Noda, T.; Neumann, G.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Generation of biologically contained Ebola viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 1129–1133. Available from: www.pnas.orgcgidoi10.1073pnas.0708057105. [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenen, T.; Groseth, A.; Callison, J.; Takada, A.; Feldmann, H. A novel Ebola virus expressing luciferase allows for rapid and quantitative testing of antivirals. Antivir. Res. 2013, 99, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.P.; Leung, L.W.; Hartman, A.L.; Martinez, O.; Shaw, M.L.; Carbonnelle, C.; Volchkov, V.E.; Nichol, S.T.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus VP24 Binds Karyopherin α1 and Blocks STAT1 Nuclear Accumulation. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5156–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.P.; Bornholdt, Z.A.; Liu, T.; Abelson, D.M.; Lee, D.E.; Li, S.; Woods, V.L., Jr.; Saphire, E.O. The Ebola Virus Interferon Antagonist VP24 Directly Binds STAT1 and Has a Novel, Pyramidal Fold. PLOS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas, W.B.; Loo, Y.-M.; Gale, M.; Hartman, A.L.; Kimberlin, C.R.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Saphire, E.O.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus VP35 Protein Binds Double-Stranded RNA and Inhibits Alpha/Beta Interferon Production Induced by RIG-I Signaling. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5168–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, C.F.; Mikulasova, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Paragas, J.; Mühlberger, E.; Bray, M.; Klenk, H.-D.; Palese, P.; García-Sastre, A. The Ebola Virus VP35 Protein Inhibits Activation of Interferon Regulatory Factor 3. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 7945–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotliar, D.; Lin, A.E.; Logue, J.; Hughes, T.K.; Khoury, N.M.; Raju, S.S.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Chen, H.; Kurtz, J.R.; Dighero-Kemp, B.; et al. Single-Cell Profiling of Ebola Virus Disease In Vivo Reveals Viral and Host Dynamics. Cell 2020, 183, 1383–1401.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, I.S.; Honko, A.N.; Gire, S.K.; Winnicki, S.M.; Melé, M.; Gerhardinger, C.; Lin, A.E.; Rinn, J.L.; Sabeti, P.C.; Hensley, L.E.; et al. In vivo Ebola virus infection leads to a strong innate response in circulating immune cells. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnosary, M.E.; Salem, F.K.; Mohamed, O.; Elbas, M.A.; Shaheen, A.A.; Mowafy, M.T.; Ali, I.E.; Tawfik, A.; Hmed, A.A.; Refaey, E.E.; et al. Unlocking the potential: a specific focus on vesicular stomatitis virus as a promising oncolytic and immunomodulatory agent in cancer therapy. Discov. Med. 2024, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, A.R.; Jankeel, A.; Feldmann, H.; Marzi, A.; Messaoudi, I. Antiviral Innate Responses Induced by VSV-EBOV Vaccination Contribute to Rapid Protection. mBio 2019, 10, e00597–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, J.; Hart, B.J.; Postnikova, E.; Cong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gerhardt, D.M.; Freeburger, D.; Michelotti, J.; Honko, A.N.; DeWald, L.E.; et al. Interferon-β and Interferon-γ Are Weak Inhibitors of Ebola Virus in Cell-Based Assays. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Benedetti, F.; Prencipe, G.; Bracaglia, C.; Marasco, E.; Grom, A.A. Targeting interferon-γ in hyperinflammation: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surasombatpattana, P.; Hamel, R.; Patramool, S.; Luplertlop, N.; Thomas, F.; Desprès, P.; Briant, L.; Yssel, H.; Missé, D. Dengue virus replication in infected human keratinocytes leads to activation of antiviral innate immune responses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 1664–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, C.F.; Wang, X.; Mü Hlberger †, E.; Volchkov, V.; Paragas, J.; Klenk, H.D.; et al. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist [Internet]. 2000. Available from: www.pnas.org.

- de Almeida, L.; Khare, S.; Misharin, A.V.; Patel, R.; Ratsimandresy, R.A.; Wallin, M.C.; Perlman, H.; Greaves, D.R.; Hoffman, H.M.; Dorfleutner, A.; et al. The PYRIN Domain-only Protein POP1 Inhibits Inflammasome Assembly and Ameliorates Inflammatory Disease. Immunity 2015, 43, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachner, J.; Mlitz, V.; Tschachler, E.; Eckhart, L. Epidermal cornification is preceded by the expression of a keratinocyte-specific set of pyroptosis-related genes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, P.; Hill-Batorski, L.; Kawaoka, Y. The Induction of IL-1β Secretion Through the NLRP3 Inflammasome During Ebola Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, S504–S507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, A.R.; Jankeel, A.; Feldmann, H.; Marzi, A.; Messaoudi, I. Antiviral Innate Responses Induced by VSV-EBOV Vaccination Contribute to Rapid Protection. mBio 2019, 10, e00597–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L.C.; A Hile, G.; Berthier, C.C.; Sarkar, M.K.; Reed, T.J.; Liu, J.; Uppala, R.; Patrick, M.; Raja, K.; Xing, X.; et al. Hypersensitive IFN Responses in Lupus Keratinocytes Reveal Key Mechanistic Determinants in Cutaneous Lupus. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervolaraki, K.; Stanifer, M.L.; Münchau, S.; Renn, L.A.; Albrecht, D.; Kurzhals, S.; Senís, E.; Grimm, D.; Schröder-Braunstein, J.; Rabin, R.L.; et al. Type I and Type III Interferons Display Different Dependency on Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases to Mount an Antiviral State in the Human Gut. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougal, M.B.; De Maria, A.M.; Ohlson, M.B.; Kumar, A.; Xing, C.; Schoggins, J.W. Interferon inhibits a model RNA virus via a limited set of inducible effector genes. Embo Rep. 2023, 24, e56901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyall, J.; Hart, B.J.; Postnikova, E.; Cong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gerhardt, D.M.; Freeburger, D.; Michelotti, J.; Honko, A.N.; DeWald, L.E.; et al. Interferon-β and Interferon-γ Are Weak Inhibitors of Ebola Virus in Cell-Based Assays. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, P.; Zou, F.; Bin, L. The Solute Carrier Transporter SLC15A3 Participates in Antiviral Innate Immune Responses against Herpes Simplex Virus-1. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, J.B.; Hsu, J.C.-C.; Xia, H.; Han, P.; Suh, H.-W.; Grove, T.L.; Morrison, J.; Shi, P.-Y.; Cresswell, P.; Laurent-Rolle, M. CMPK2 restricts Zika virus replication by inhibiting viral translation. PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, W.H. Medical Virology of Hepatitis B: how it began and where we are now. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 239–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, B. Greenberg. Effect of human leukocyte interferon on Hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic active hepatitis. 1976.

- Lmar, E.; Aeckel, J.; Arkus, M.; Ornberg, C.; Eresa, T.; Antantonio, S. , et al. TREATMENT OF ACUTE HEPATITIS C WITH INTERFERON ALFA-2b A BSTRACT Background In people who are infected with the [Internet]. N Engl J Med. 2001, 345. Available from: www.nejm.org.

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y.; Sutter, K.; Dittmer, U. , et al. Functional Comparison of Interferon-α Subtypes Reveals Potent Hepatitis B Virus Suppression by a Concerted Action of Interferon-α and Interferon-γ Signaling. 486 Hepatology. 2021, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, S.; Koh, D.H.; Yu, S.Y.; Choi, M.; Huh, K.; Yeom, J.S. , et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of interferon (Type I and Type III) therapy in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Geisbert, T.W.; Geisbert, J.B.; Swearengen, J.R.; Bray, M.; Jaax, N.K. , et al. Evaluation of Immune Globulin and Recombinant Interferon-a2b for Treatment of Experimental Ebola Virus Infections [Internet]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/179/Supplement_1/S224/881508.

- Qiu, X.; Wong, G.; Fernando, L.; Audet, J.; Bello, A.; Strong, J.; et al. E B O L A mAbs and Ad-Vectored IFN-a Therapy Rescue Ebola-Infected Nonhuman Primates When Administered After the Detection of Viremia and Symptoms [Internet]. Available from: https://www.science.org.

- Senthilkumaran, C.; Kroeker, A.L.; Smith, G.; Embury-Hyatt, C.; Collignon, B.; Ramirez-Medina, E. , et al. Treatment with Ad5-Porcine Interferon-α Attenuates Ebolavirus Disease in Pigs. Pathogens. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Hensley, L.E.; Geisbert, T.W.; Johnson, J.; Stossel, A.; Honko, A. , et al. Interferon- therapy prolongs survival in rhesus macaque models of ebola and marburg hemorrhagic fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013, 208, 310–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, S.; Journeaux, A.; Gloaguen, E.; Schaeffer, J.; Varet, H.; Pietrosemoli, N. , et al. Immune parameters and outcomes during Ebola virus disease. Immune parameters and outcomes during Ebola virus disease. JCI Insight. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).