Introduction

The gender-diverse community in India, which includes transgender, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming individuals, is currently grappling with a severe and urgent healthcare crisis. The Census of India, 2011, estimates that there are approximately 4.9 lakh transgender individuals in the country [

1]. Despite the legal framework provided by the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, the reality on the ground is starkly different. The healthcare needs of gender-diverse individuals are largely unmet and invisible due to systemic discrimination, societal stigma, and a lack of inclusive institutional frameworks [

2,

3]. The consequences of this exclusion are profound, leading to socio-economic marginalization, limited access to education and employment, and frequent experiences of violence and rejection. These factors significantly increase their vulnerability to a wide range of health issues, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), substance abuse, and mental health disorders [

4,

5]. Mistrust in healthcare systems is widespread—studies show that 70% of transgender individuals have been mistreated in medical settings, while nearly 30% avoid seeking care altogether due to fear of discrimination [

6].

Oral health, a fundamental component of overall well-being, remains one of the most overlooked aspects of health for gender-diverse populations. Many individuals experience oral health challenges linked to hormone replacement therapy (HRT), increased tobacco use, poor nutrition, and limited access to preventive care [

7]. However, the lack of awareness, infrastructure, and sensitivity in dental care systems significantly hinders their access to essential oral healthcare. Oral health professionals serve as gatekeepers to preventive and therapeutic care. However, existing literature points to a significant gap in their preparedness to cater to gender-diverse populations. Most dental practitioners lack training in gender sensitivity, cultural competency, and inclusive care [

8]. A 2018 study reported that half of all medical providers had never received training on transgender healthcare, with the dental field lagging further behind [

9]. Misgendering, biased behavior, and even refusal of care are common deterrents to seeking oral care [

10], further widening the care gap. Adding to this challenge is the absence of gender-inclusive principles in dental education and clinical guidelines that leave many practitioners underprepared to deliver appropriate care to gender-diverse individuals [

9,

11].

The Kartavya Model, proposed by Kumar et al., stands out as a landmark initiative in promoting inclusive, affirmative healthcare delivery. Emphasizing a multi-pronged approach involving policy reform, sensitization training, and community engagement, the model has begun to reshape how gender-diverse healthcare is envisioned in India. Its application within dentistry offers an opportunity to bridge a gap by equipping oral health providers with the tools to offer compassionate, informed, and respectful care. Despite international advancements, Indian dentistry has remained largely silent on this front. There is an urgent need for a systematic, empirical assessment of the gender sensitivity, inclusiveness, and clinical preparedness of oral health professionals. Such data are vital for informing policy decisions, reforming dental education, and fostering equitable care environments. Addressing these disparities is not only a matter of social justice but also a public health imperative, ensuring that every individual, regardless of their gender identity, has access to dignified and comprehensive oral healthcare. However, India still lacks robust, nation-wide evidence that evaluates these dimensions in oral healthcare delivery. Without such benchmarks, reform efforts remain fragmented and insufficient. To address this critical gap, the present study—Advancing Gender-Inclusive Dentistry in India: Multizonal National Benchmarking of Oral Health Professionals’ Sensitivity, Inclusiveness, and Preparedness Using the novel OHP-GSIP Tool—seeks to generate the first structured national dataset that can inform education, training, and policy frameworks for gender-inclusive dentistry.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was designed to assess the gender sensitivity, inclusivity, and preparedness of oral healthcare professionals in India towards providing care for the transgender population. The study utilized a novel pre-validated instrument, the Oral Healthcare Professional's Gender Sensitivity, Inclusivity, and Preparedness (OHP–GSIP) Scale. This comprehensive tool, a closed-ended, structured questionnaire comprising five distinct domains: Unit 1, Gender Sensitivity and Awareness (9 items); Unit 2, Safe, Inclusive Spaces for Oral Healthcare Delivery (4 items); Unit 3, Diversity and Inclusivity in Dental Practice (4 items); Unit 4, Attitudes of Dental Professionals Towards Inclusive Practice (5 items); and Unit 5, Preparedness to Provide Oral Healthcare Services to Transgender Individuals (4 items), has undergone rigorous face and content validation, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency. A pilot study was conducted among 50 oral healthcare professionals to assess the clarity, feasibility, and comprehensibility of the tool, and to inform the determination of the final sample size. The OHP-GSIP Tool is a robust and reliable instrument that provides a comprehensive assessment of the current state of gender-inclusive dentistry in India, instilling confidence in the accuracy and relevance of the study findings.

The sample size was calculated using the formula N = Z²pq/d², where Z = 1.96 (for a 95% confidence interval), p = 0.31 (the expected proportion based on pilot data), q = 1–p = 0.69, and d = 1.5 (the absolute precision). Substituting values: N = (1.96) ² × 31 × 69/(1.5) ² = 3,660. Thus, the final estimated sample size was 3,660 participants. A Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling technique was employed to ensure equitable representation of dental professionals from all geographic regions of India. This technique was chosen because it allows for a more accurate representation of the population, as it ensures that the sample size for each region is proportionate to the total number of registered dentists in that region. The six zones—Northern, Central, Eastern, Western, Southern, and North-Eastern—were considered for stratified sampling based on the total number of registered dentists, as per data obtained from the Dental Council of India (

https://dciindia.gov.in/DentistRegistered.aspx). The zonal distribution of registered dentists and the proportionally allocated sample sizes were as follows: Northern Zone 72,140 dentists, 679 participants; Central Zone 44,433 dentists, 418 participants; Eastern Zone 22,312 dentists, 210 participants; Western Zone 86,144 dentists, 811 participants; Southern Zone 155,337 dentists, 1,462 participants; and North-Eastern Zone 8,385 dentists, 79 participants. This stratified sampling method enhanced the representativeness, generalizability, and external validity of the study findings.

The inclusion criteria consisted of registered and qualified dental practitioners across India. Exclusion criteria included dental professionals not currently engaged in clinical or institutional practice, undergraduate dental students, and individuals not registered to practice dentistry. Data were collected via a structured online survey distributed through Google Forms. The link was disseminated via email and through professional networks, forums, and dental societies to ensure wide and diverse participation across all zones. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the demographic characteristics and responses. Independent t-tests were used to assess differences in responses between institutional and private practitioners. One-way ANOVA was applied to compare mean scores across the five domains of the OHP–GSIP scale. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

The survey explored the understanding, awareness, and inclusivity attitudes of dental professionals and students regarding gender diversity, focusing on intersex, cisgender, and transgender identities. Most respondents correctly identified intersex as individuals born with reproductive or sexual anatomy not fitting typical male or female categories (65.5%) and cisgender as those whose gender identity aligns with their assigned sex at birth (77.2%). Approximately 66% recognized transgender individuals as individuals whose gender identity differs from their assigned sex. Despite this, misconceptions persisted, particularly equating these terms with cross-dressing or drag. While 65.1% indicated they would ask for a person's preferred pronouns, only 38.6% acknowledged the link between gender identity and expression. Structural inclusivity was limited, as only 23.5% reported having gender-neutral restrooms and 17.5% had intake forms that included options beyond binary gender choices. Nonetheless, over 90% expressed openness to employing, collaborating with, and supporting transgender individuals, though visual and educational representations remained limited. Overall, positive attitudes coexisted with gaps in institutional inclusivity and a lack of comprehensive understanding.

Descriptive statistics revealed moderate LGBTQIA+ knowledge (mean = 6.52/10, SD = 1.78), characterized by a slight negative skew and non-normal distribution. Participants reported moderate comfort in treating transgender patients (mean = 3.81/5, SD = 1.09). Awareness of gender-affirming clinics was limited (mean = 0.55), and perceived inclusivity in practice settings was moderate (mean = 3.23). Willingness to employ a transgender person was observed in 62% of respondents (mean = 0.62). All variables exhibited significant deviations from normality, underscoring room for improvement in knowledge, awareness, and structural inclusivity.

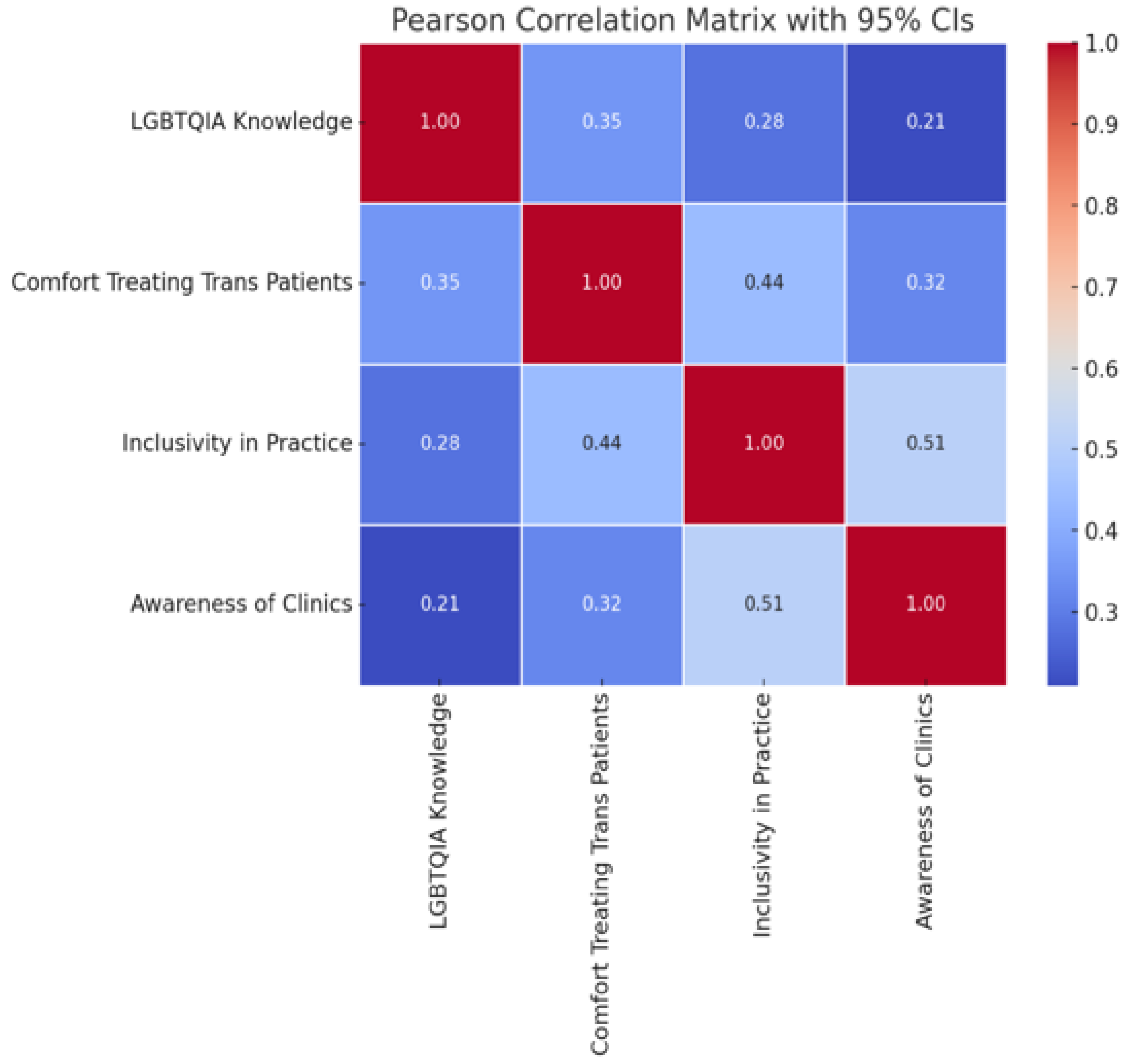

Chi-square analyses revealed no significant association between willingness to employ a transgender individual and comfort in treating trans patients (χ²(1) = 0.98, p = 0.322). Conversely, significant associations emerged between comfort and awareness of gender-affirming clinics (χ²(1) = 25.62, p < 0.001) and inclusivity in practice (χ²(1) = 39.24, p < 0.001), indicating that more inclusive environments correlated with greater clinical comfort. The correlation matrix highlighted moderate positive relationships among variables: inclusivity was strongly correlated with awareness of clinics (r = 0.51), and both were associated with comfort in treating transgender patients (r = 0.44 and r = 0.35, respectively). LGBTQIA+ knowledge correlated moderately with comfort (r = 0.35) and less with inclusivity and awareness, suggesting interconnected pathways influencing clinical attitudes.

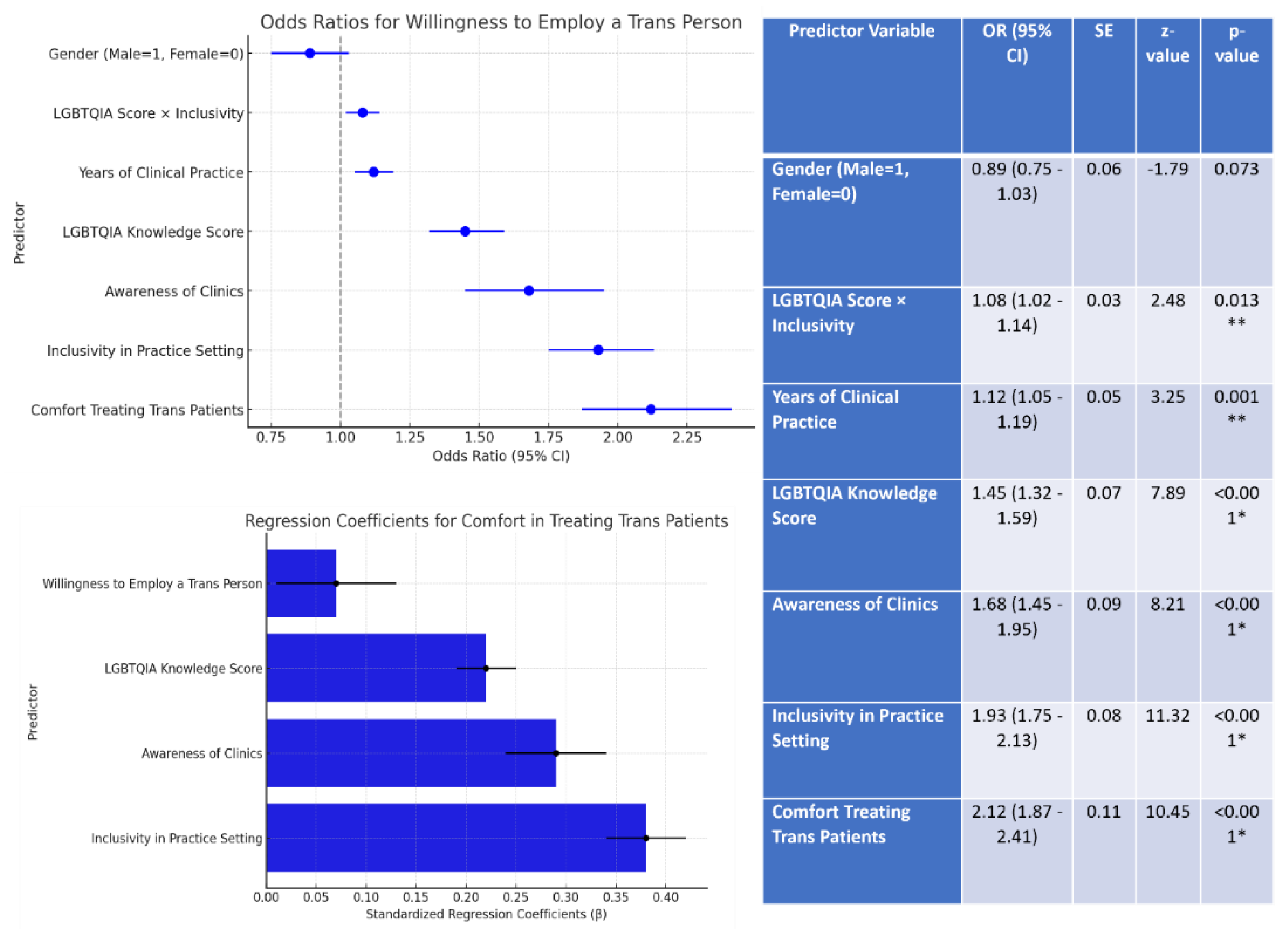

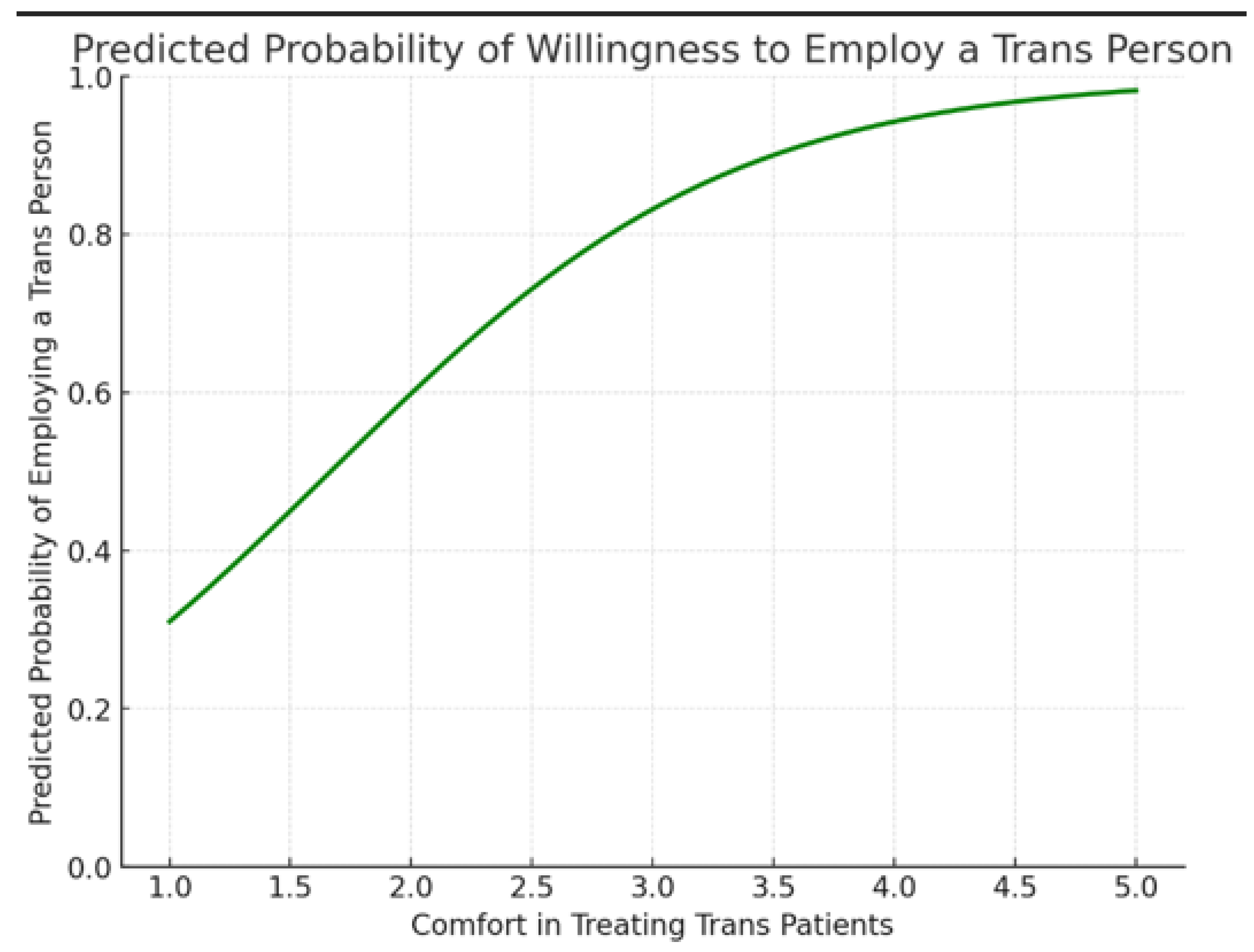

The multiple regression model demonstrated that inclusivity (β = 0.38, p < 0.001), awareness (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), and LGBTQIA+ knowledge (β = 0.22, p < 0.001) significantly predicted comfort in treating transgender patients, while willingness to employ a trans person was not a significant predictor. The model explained approximately 41% of the variance. Greater clinician comfort substantially increased the likelihood of willingness to employ transgender individuals (OR = 2.12, p < 0.001). Other significant predictors included practice inclusivity (OR = 1.93), awareness of clinics (OR = 1.68), knowledge of LGBTQIA+ issues (OR = 1.45), and clinical experience (OR = 1.12). Gender was not a significant factor. Overall, despite generally progressive attitudes, significant gaps in structural inclusivity and comprehensive understanding remained in dental settings.

Discussion

This study offers an important and timely look into how dental professionals in India understand and engage with the healthcare needs of transgender and gender-diverse individuals. While it echoes many global findings, it also presents unique insights that are specific to the Indian context. Globally, healthcare providers, including those in dentistry, have long struggled with issues related to gender sensitivity and inclusivity. Studies such as those by Heng et al. show that many dental professionals feel unprepared to treat LGBTQIA+ patients due to a lack of training and inclusive education [

9]. This sentiment is reflected in our findings, where respondents demonstrated only moderate levels of knowledge and awareness about LGBTQIA+ issues.

Other international research paints a similar picture. Obedin-Maliver and colleagues found that medical students receive very little formal education on transgender health, which leaves them unequipped to offer respectful and competent care [

8]. Safer and Tangpricha emphasized that this gap in education can lead to experiences of discrimination, ultimately deterring transgender individuals from seeking care [

10]. Our study's findings—such as the fact that only about 38.6% of respondents understood the connection between gender identity and expression—highlight the urgent need for improved education and awareness in Indian dental institutions.

Structural exclusion is another recurring theme. In countries like Canada and the United States, transgender individuals often face physical and systemic barriers when seeking care. Bauer et al. reported that many emergency departments lacked gender-neutral facilities and inclusive intake forms [

11]. In our survey, only 23.5% of respondents had gender-neutral restrooms, and a mere 17.5% offered non-binary options on intake forms—suggesting that these barriers are just as present in Indian dental practices. Despite these shortcomings, there is a silver lining. A striking majority of our respondents—over 90%—expressed a willingness to support, collaborate with, and employ transgender individuals. This openness contrasts with some Western contexts where overt or covert bias is still common. It signals a promising foundation upon which more inclusive dental practices can be built in India.

Another interesting observation is the disconnection between moral support and clinical confidence. While many participants were open to hiring transgender colleagues, this did not necessarily translate into feeling confident about treating transgender patients. This finding highlights an important nuance: good intentions alone are not enough. Training, experience, and supportive institutional policies are needed to turn goodwill into competent care, a point emphasized by Heng et al. [

9]. Our regression analysis revealed that a dentist's comfort in treating transgender individuals was most strongly predicted by three factors: the inclusivity of their practice environment (β = 0.38), their awareness of gender-affirming clinics (β = 0.29), and their general knowledge of LGBTQIA+ topics (β = 0.22). These findings align with international studies, which show that when providers are trained and supported by inclusive systems, their confidence and competence naturally improve [

9,

10].

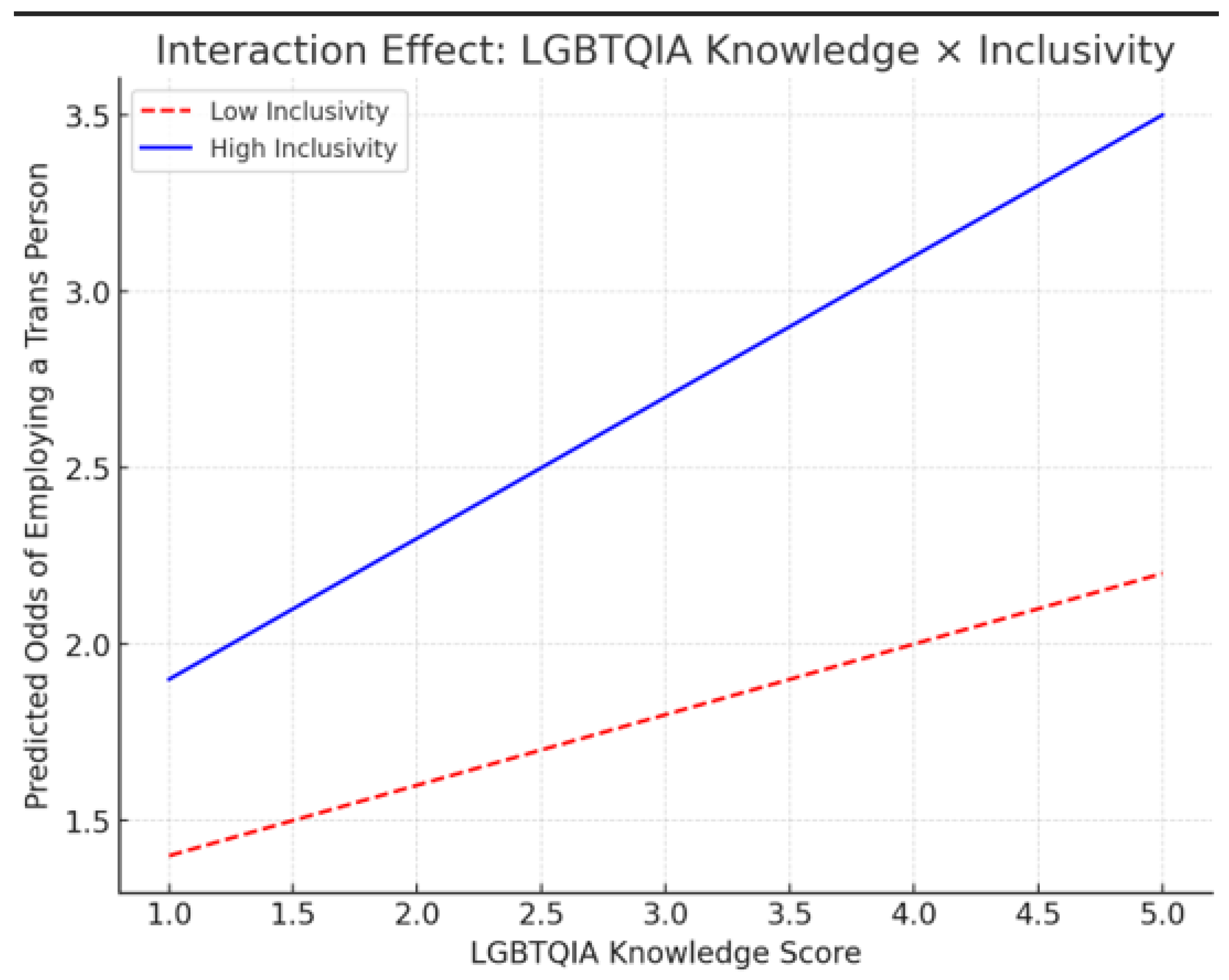

Interestingly, the simple willingness to employ a transgender person did not predict greater clinical comfort. This distinction matters: inclusive hiring is a significant first step, but it does not automatically lead to better patient care. A more holistic approach is needed—one that combines education, awareness, and institutional change. One of the most telling insights from this study is how inclusivity amplifies the effect of knowledge. Our data show that in more inclusive work environments, the benefits of having LGBTQIA+ knowledge are even greater when it comes to hiring and supporting transgender individuals. This reflects a core tenet of the Kartavya Model, proposed by Kumar et al., which advocates for systemic, multi-level reforms encompassing policy, training, and community engagement to create affirming healthcare spaces. This idea also echoes international work by Winter et al., who advocate for comprehensive reforms that integrate cultural competence into every level of the healthcare system [

4]. Both frameworks agree: inclusion is not just a checkbox—it is a catalyst for change.

Compared to much of the global literature, this study provides a more optimistic perspective on how Indian dental professionals perceive gender-diverse individuals. Still, there is work to be done. Knowledge gaps, infrastructural shortcomings, and limited clinical experience with transgender patients continue to pose significant barriers. Future efforts must prioritize inclusive curriculum development, structural reforms in practice environments, and sustained community engagement. As highlighted by Pega and Veale, addressing gender identity as a social determinant of health is not just progressive but essential to public health [

3].

Conclusion

This study reinforces a key message heard around the world: transgender individuals deserve the same dignity and quality of care as anyone else. Encouragingly, many Indian dental professionals are ready to be part of that change. With the proper training, support, and systemic reform, it is possible to create a healthcare system that truly sees and serves everyone—regardless of gender identity. Curriculum modules on gender inclusivity, mandatory sensitivity training, and integration into Dental Council of India accreditation standards should be prioritized.

Table 1.

Knowledge and Awareness of Gender-Diversity Terms among Dental Professionals (N = 3,660).

Table 1.

Knowledge and Awareness of Gender-Diversity Terms among Dental Professionals (N = 3,660).

| |

|

% within Level of experience |

Total (N) |

X2 |

P value |

| UNIT 1: GENDER SENSITIVITY & AWARENESS |

| Questions |

Options |

0-5 years |

5-15 years |

> 15 years |

|

|

|

| |

Total |

100%

(n=1435) |

100%

(n=770) |

100%

(n=1455) |

3660 |

|

|

1. What is the

full form of LGBTQIA? |

1. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, Queer, Intersex, Asexual |

67.8%

(n=973) |

70.6%

(n=544) |

70.2%

(n=1022) |

69.4%

(n=2539) |

5.932 |

0.043* |

| 2. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex Ally |

17.8%

(n=255) |

15.8%

(n=122) |

15.0%

(n=218) |

16.3%

(n=595) |

| 3. Both the above |

4.6%

(n=141) |

3.8%

(n=75) |

4.1%

(n=155) |

4.2%

(n=371) |

4. None of the above

|

4.6%

(n=66) |

3.8%

(n=29) |

4.1%

(n=60) |

4.2%

(n=155) |

| 2. Does Transgender and Transsexual mean the same? |

1.Yes |

17.8%

(n=256) |

15.8%

(n=122) |

15.1%

(n=220) |

16.3%

(n=598) |

4.083 |

0.0130* |

| 2.No |

82.2%

(n=1179) |

84.2%

(n=648) |

84.9%

(n=1235) |

83.7%

(n=3062) |

| 3. Is Gender and sex the same thing? |

1.Yes |

15.0%

(n=215) |

14.9%

(n=115) |

14.6%

(n=213) |

14.8%

(n=543) |

0.075 |

.0491* |

| 2.No |

85.0%

(n=1220) |

85.1%

(n=655) |

85.4%

(n=1242) |

85.2%

(n=3117) |

| 4. What do you understand by the term Intersex? |

1.When a person's gender identity or expression do not line up with societal expectation (sex assigned at birth based on genitals) |

27.1%

(n=389)

|

29.4%

(n=226) |

27.8%

(n=405) |

27.9%

(n=1020) |

5.784 |

0.0448*

|

| 2. Drag (performance/ playing dress-up/ cross-dressing) |

4.8%

(n=69) |

3.5%

(n=27) |

4.1%

(n=60) |

4.3%

(n=156) |

| 3. A general term used for various situations in which a person is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the categories of "female" or "male." |

65.9%

(n=946) |

64.0%

(n=493) |

65.9%

(n=959) |

65.5%

(n=2398) |

| 4. Denoting or relating to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex. |

2.2%

(n=31) |

3.1%

(n=24) |

2.1%

(n=31) |

2.3%

(n=86) |

| 5. What do you understand by the term Cisgender? |

1. When a person's gender identity or expression do not line up with societal expectation (sex assigned at birth based on genitals) |

4.9%

(n=71) |

4.0%

(n=31) |

4.4%

(n=64) |

4.5%

(n=166) |

5.112

|

0.0453*

|

| 2. Drag(performance/ playing dress-up/ cross-dressing ) |

8.8%

(n=126) |

10.6%

(n=82) |

10.9%

(n=159) |

10.0%

(n=367) |

| 3. A general term used for a variety of situations in which a person is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn't fit the categories of "female" or "male". |

8.4%

(n=121) |

7.9%

(n=61) |

8.3%

(n=121) |

8.3%

(n=303) |

| 4. Denoting or relating to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex |

77.8%

(n=1117) |

77.4%

(n=596) |

76.4%

(n=1111) |

77.2%

(n=2824) |

| 6. What do you understand by the term Transgender? |

1. When a person's gender identity or expression does not line up with societal expectations (sex assigned at birth based on genitals) |

65.5%

(n=940) |

63.5%

(n=489) |

67.5%

(n=982) |

65.9%

(n=2411) |

5.328 |

.005** |

| 2. Drag (performance/ playing dress-up/ cross-dressing ) |

4.0%

(n=58) |

4.2%

(n=32) |

4.0%

(n=58) |

4.0%

(n=148) |

| 3. A general term used for a variety of situations in which a person is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn't fit the categories of "female" or "male". |

30.4%

(n=436) |

32.2%

(n=248) |

28.5%

(n=415) |

30.0%

(n=1099) |

| 4. Denoting or relating to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex |

0.1%

(n=1) |

0.1%

(n=1) |

0.0%

(n=0) |

0.1%

(n=2) |

| 7. Is gender identity related to gender expression? |

1.Yes |

39.8%

(n=571) |

39.1%

(n=301) |

37.1%

(n=540) |

38.6%

(n=1412) |

2.294 |

.0381* |

| 2.No |

60.2%

(n=864) |

60.9%

(n=469) |

62.9%

(n=915) |

61.4%

(n=2248) |

| 8. If a person is born as a female but they identify themselves as male, what would be the gender of the person? |

1. Male |

16.1%

(n=231) |

15.5%

(n=119) |

17.3%

(n=251) |

16.4%

(n=601) |

| 2. Female |

12.1%

(n=174) |

11.6%

(n=89) |

12.2%

(n=177) |

12.0%

(n=440) |

| 3. Gender Fluid |

15.9%

(n=228) |

18.3%

(n=141) |

14.8%

(n=216) |

16.0%

(n=585) |

| 4. Transgender |

55.9%

(n=802) |

54.7%

(n=421) |

55.7%

(n=811) |

55.6%

(n=2034) |

| 9. When a person wearing a saree walks into your clinic/institute where you work/study, how will you address them? |

1. She/ Her |

27.9%

(n=401) |

28.1%

(n=216) |

28.0%

(n=408) |

28.0%

(n=1025) |

| 2. They/ Them |

4.5%

(n=65) |

4.7%

(n=36) |

4.3%

(n=62) |

4.5%

(n=163) |

| 3. Xe/ Xem |

2.6%

(n=38) |

2.2%

(n=17) |

2.3%

(n=33) |

2.4%

(n=88) |

| 4. Ask For Their Preferred Pronouns |

64.9%

(n=931) |

65.1%

(n=501) |

65.4%

(n=952) |

65.1%

(n=2384) |

| UNIT 2: SAFE INCLUSIVE SPACES FOR ORAL HEALTH CARE DELIVERY |

| 1. In your dental practice or institute in which you work/study, do you find posters, artwork, or information representing the transgender community? |

1.Yes |

47.2%

(n=678)

|

43.9%

(n=338) |

44.2%

(n=643) |

45.3%

(n=1659) |

5.329

|

.0471 |

| 2.No |

47.2%

(n=757) |

43.9%

(n=432) |

44.2%

(n=812) |

45.3%

(n=2001) |

| 2. Do you find any other Information-Education-Communication material on the transgender community in the waiting area of your dental practice or institute you work/study at? |

1.Yes |

29.2%

(n=419) |

29.7%

(n=229) |

25.9%

(n=377) |

28.0%

(n=1025) |

| 2.No |

70.8%

(n=1016) |

70.3%

(n=541) |

74.1%

(n=1078) |

72.0%

(n=2635) |

| 3. Does your dental practice/institute have a gender-neutral restroom with appropriate symbols/signage? |

1.Yes |

23.1%

(n=331) |

24.0%

(n=185) |

23.6%

(n=344) |

23.5%

(860) |

.285 |

.0437 |

| 2.No |

76.9%

(n=1104) |

76.0%

(n=585) |

76.4%

(n=1111) |

76.5%

(n=2800) |

| 4. Are genders other than male and female mentioned along with appropriate pronouns for salutations in your dental practice/institute's intake form (OPD paper) under the gender information section? |

1.Yes |

17.0%

(n=244) |

17.1%

(n=132) |

18.1%

(n=263) |

17.5%

(n=639) |

.644 |

.037 |

| 2.No |

83.0%

(n=1191) |

82.9%

(n=638) |

81.9%

(n=1192) |

82.5%

(n=3021) |

| UNIT 3: DIVERSITY AND INCLUSIVITY IN DENTAL PRACTICE |

| 1. Would you be open to give employment to a transgender person in your dental practice or at the institute you work/study? |

1.Yes |

89.5%

(n=1284) |

90.3%

(n=695) |

90.5%

(n=1317) |

90.1%

(n=3296) |

.915 |

.043 |

| 2.No |

10.5%

(n=151) |

9.7%

(n=75) |

9.5%

(n=138) |

9.9%

(n=364) |

| 2. Would you be comfortable working alongside a colleague who identifies themselves as Transgender? |

1.Yes |

92.0%

(n=1320) |

93.5%

(n=720) |

92.2%

(n=1341) |

92.4%

(n=3381) |

1.789 |

.0407 |

| 2.No |

8.0%

(n=115) |

6.5%

(n=50) |

7.8%

(n=114) |

7.6%

(n=279) |

| 3. Would you be willing to be working with forums working for the development of the transgender community? |

1.Yes |

94.3%

(n=1353) |

93.9%

(n=723) |

93.7%

(n=1364) |

94.0%

(n=3340) |

.388 |

.0482 |

| 2.No |

5.7%

(n=82) |

6.1%

(n=47) |

6.3%

(n=91) |

6.0%

(n=220) |

| 4. Would you feel comfortable seeing a person identifying themselves as Transgender in a leadership position at your dental practice/institute you work/ study? practice/institute's intake form (OPD paper) under the gender information section? |

1.Yes |

95.5%

(n=1370) |

96.4%

(n=742) |

96.0%

(n=1397) |

95.9%

(n=3509) |

1.130 |

.0456 |

| 2.No |

4.5%

(n=65) |

3.6%

(n=28) |

4.0%

(n=58) |

4.1%

(n=151) |

| UNIT 4: ATTITUDES OF DENTAL PROFESSIONALS TOWARDS AN INCLUSIVE PRACTICE |

| 1. If a person identifying as Transgender seeks treatment at your private practice/ institute you work/study at, would you :- |

1. Give them an appointment separately |

9.1%

(n=131) |

10.0%

(n=77) |

9.0%

(n=131) |

9.3%

(n=339) |

.645 |

.0372* |

| 2.Give them an appointment along with other patients |

90.9%

(n= 1304) |

90.0%

(n=693) |

91.0%

(n=1324) |

90.7%

(n= 3321) |

| 2. If a person identifying as Transgender seeks treatment from your practice/ institute you work/study at, would you :- |

1.Do the treatment yourself |

94.4%

(n= 1354) |

94.3%

(n=726) |

94.8%

(n=1379) |

94.5%

(n=3549) |

0.340 |

0.048 |

| 2.Pass it on to your trainees or associate |

5.6%

(n=81) |

5.7%

(n=44) |

5.2%

(n=76) |

5.5%

(n=201) |

| 3. Would you be comfortable treating a transgender person? |

1.Yes |

89.8%

(n=1288) |

87.9%

(n=677) |

90.7%

(n=1320) |

89.8%

(n=3285) |

|

|

| 2.No |

10.2%

(n= 147) |

12.1%

(n=93) |

9.3%

(n=135) |

10.2%

(n=375) |

|

|

| 4. If a transgender person seeks treatment from your private practice/ institute you work/study at, are you likely to give them :- |

1. Discounts if they belong from an economically backward status |

67.2%

(n=965) |

64.2%

(n=494) |

65.6%

(n=955) |

66.0%

(n=2414) |

2.244 |

0.0326 |

| 2.No discount |

32.8%

|

35.8%

|

34.4%

|

34.0%

|

| 5. For & after treating a transgender person, would you :- |

1. Use only disposable instruments so that you can throw them away |

12.7%

(n=182) |

11.7%

(n=90) |

11.2%

(n=163) |

11.9%

(n=435) |

1.548 |

0.0461* |

| 2. Follow appropriate sterilization protocol & reuse non-disposable instruments for other patients |

87.3%

(n=1253) |

88.3%

(n=680) |

88.8%

(n=1292) |

88.1%

(n=3225) |

| UNIT 4: ATTITUDES OF DENTAL PROFESSIONALS TOWARDS AN INCLUSIVE PRACTICE |

| 1. If a person identifying as Transgender seeks treatment from your private practice/institute you work/study at, you are more likely to check for:- |

1. Common oral manifestations of HIV |

10.9%

(n=156) |

11.6%

(n=89) |

9.9%

(n=144) |

10.6%

(n=389) |

5.932 |

0.0431* |

| 2.Tobacco history |

1.5%

(n=22) |

1.4%

(n=11) |

2.0%

(n=29) |

1.7%

(n=62) |

| 3. Hormone replacement therapy |

5.8%

(n=83) |

7.3%

(n=56) |

6.4%

(n=93) |

6.3%

(n=232) |

| 4. All of the above |

81.8%

(n=1174) |

79.7%

(n=614) |

81.7%

(n=1189) |

81.3%

(n=2977) |

| 2. Are you aware of the nearest testing & treatment facilities for HIV services for referral and linkages? |

1. Yes |

17.8%

(n=256) |

15.8%

(n=122) |

15.1%

(n=220) |

16.3%

(n=598) |

2.711 |

0.0258 |

| 2. No |

82.2%

(n=1179) |

84.2%

(n=648) |

84.9%

(n=1235) |

83.7%

(n=3062) |

| 3. Are you aware of oral manifestations of Hormone Replacement Therapy? |

1.Yes |

43.8%

(n=628) |

45.2%

(n=348) |

43.7%

(n=636) |

44.0%

(n=1612) |

0.525 |

0.0401 |

| 2.No |

56.2%

(n=807) |

54.8%

(n=422) |

56.3%

(n=819) |

56.0%

(n=2048) |

| 4. Do you know about clinics, hospitals and healthcare professionals providing various gender-affirmative healthcare services (in case required by your transgender client)? |

1. Yes |

27.9%

(n=400) |

29.1%

(n=224) |

27.6%

(n=401) |

28.0%

(n=1025) |

0.605 |

0.0487 |

| 2.No |

72.1%

(n=1035) |

70.9%

(n=546) |

72.4%

(n=1054) |

72.0%

(n=2635) |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables (N = 3660).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables (N = 3660).

| Variable |

Mean (SD) |

Median (IQR) |

Min |

Max |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Normality (Shapiro-Wilk p) |

| LGBTQIA Knowledge Score (0-10) |

6.52 (1.78) |

7 (5-8) |

2 |

10 |

-0.46 |

2.35 |

<0.001* |

| Comfort in Treating Trans Patients (1-5) |

3.81 (1.09) |

4 (3-5) |

1 |

5 |

-0.52 |

2.12 |

<0.001* |

| Awareness of Gender-Affirming Clinics (Yes=1, No=0) |

0.55 (0.49) |

1 (0-1) |

0 |

1 |

-0.20 |

1.04 |

0.021 |

| Inclusivity in Practice Setting (1-5) |

3.23 (1.36) |

3 (2-4) |

1 |

5 |

0.14 |

2.41 |

0.018 |

| Willingness to Employ a Trans Person (Yes=1, No=0) |

0.62 (0.48) |

1 (0-1) |

0 |

1 |

-0.49 |

1.13 |

<0.001* |

Table 3.

Chi-Square Test for Association Between Categorical Variables.

Table 3.

Chi-Square Test for Association Between Categorical Variables.

| Variables Compared |

χ² (df) |

p-value |

Cramér's V |

Interpretation |

| Willingness to Employ a Trans Person vs. Comfort Treating Trans Patients |

0.98 (1) |

0.322 |

0.05 |

No Significant Association |

| Awareness of Clinics vs. Comfort Treating Trans Patients |

25.62 (1) |

<0.001* |

0.20 |

Moderate Association |

| Inclusivity in Practice vs. Comfort Treating Trans Patients |

39.24 (1) |

<0.001* |

0.27 |

Strong Association |

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Comfort in Treating Trans Patients.

Dependent Variable: Comfort in Treating Trans Patients (1-5 scale).

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Comfort in Treating Trans Patients.

Dependent Variable: Comfort in Treating Trans Patients (1-5 scale).

| Predictor Variable |

β (Std.) |

SE |

t-value |

p-value |

VIF |

| LGBTQIA Knowledge Score |

0.22 |

0.03 |

7.11 |

<0.001* |

1.21 |

| Inclusivity in Practice Setting |

0.38 |

0.04 |

9.32 |

<0.001* |

1.39 |

| Awareness of Clinics |

0.29 |

0.05 |

6.45 |

<0.001* |

1.18 |

| Willingness to Employ a Trans Person |

0.07 |

0.06 |

1.45 |

0.147 |

1.05 |

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix of key variables.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix of key variables.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression predicting willingness to employ transgender individuals.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression predicting willingness to employ transgender individuals.

Figure 3.

Positive correlation between comfort and willingness to employ transgender individuals.

Figure 3.

Positive correlation between comfort and willingness to employ transgender individuals.

Figure 4.

Interaction effect of knowledge and inclusivity.

Figure 4.

Interaction effect of knowledge and inclusivity.

References

- Census of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011.

- Government of India. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act. 2019.

- Pega F, Veale JF. The case for the World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health to address gender identity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):e58–62. [CrossRef]

- Winter S, Settle E, Wylie K, et al. Synergies in health and human rights: A call to action to improve transgender health. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):2221–33. [CrossRef]

- Reisner SL, White JM, Bradford JB, Mimiaga MJ. Transgender health disparities: Comparing full cohort and nested matched-pair study designs in a community health center. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):103–113. [CrossRef]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet LA, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016.

- Armuand GM, Dhejne C, Olofsson JI, Stefenson M. Transgender people’s experiences of fertility preservation: A qualitative study. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):383–390.

- Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender–related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977. [CrossRef]

- Heng JY, Hackett J, Minchin K. Dental students' and dental professionals' attitudes towards LGBT patients: A scoping review. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(10):1022–1029.

- Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of transgender persons. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2451–2460. [CrossRef]

- Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Deutsch MB, Massarella C. Reported emergency department avoidance, use, and experiences of transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;63(6):713–720.e1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).