1. Introduction

As one of the world’s most consumed beverages, tea (

Camellia sinensis) is a globally significant crop cultivated across 5.7 million hectares, underpinning rural economies and livelihoods throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America [

1,

2,

3]. Globally, the tea trade is valued at over USD 9 billion annually, making its sustainability a priority in international agricultural policy [

1]. However, the environmental footprint of tea production poses a substantial challenge to its long-term viability. Intensive cultivation, characterized by heavy nitrogenous fertilizer application, frequently leads to soil degradation, including acidification and nutrient depletion, which compromises soil fertility [

4,

5]. Consequently, tea plantations have become notable sources of soil greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, particularly nitrous oxide (N

2O) and carbon dioxide (CO

2) [

6]. Addressing these interconnected challenges is now critical as the global community strives to meet sustainability targets for carbon neutrality and land restoration [

7,

8,

9]. This creates a critical tension necessitating innovative management practices that can align tea production with global climate and land restoration goals.

Two primary approaches to enhancing the sustainability of tea plantations have been the implementation of agroforestry practices and the addition of organic soil amendments. Shade-tree tea agroforestry—a management system integrating tea bushes with an overstory of diverse trees—offers a promising framework for developing sustainable solutions. These multi-strata structure enhances carbon sequestration, optimizes nutrient cycling and soil fertility, moderates the soil microclimate, and influences the microbial processes that drive GHG fluxes [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Organic soil amendments may also be used to enhance tea plantation sustainability by acting as both a direct source of nutrients and by enhancing soil physicochemical properties, including the capacity of the soil to retain water and nutrients. The primary organic soil amendments used in this context have been manures [e.g., [

14,

15]], composts [

16], mulches [

17], and bacterial inoculants [

18].

Biochar has recently emerged as a key soil amendment for climate-smart agriculture [

19]. Produced from the pyrolysis of biomass, biochar is a stable, carbon-rich material whose unique properties—including a highly porous structure, large specific surface area, and chemical recalcitrance—distinguish it from rapidly decomposing organic amendments like composts or manures [

20,

21]. Its application has been shown to improve soil physical structure, increase water and nutrient retention, enhance nutrient availability, create favorable conditions for soil microbial communities, and ameliorate soil acidity, providing a durable foundation for enhanced soil health in various agroecosystems [

3,

22,

23,

24,

25].

The intensive management required for tea production often leads to a cascade of soil health issues, including degradation from high nutrient demand, soil acidification, and compaction, which in turn drive inefficient water use and elevate emissions of GHGs [

4,

6]. Biochar application potentially offers a multifaceted approach to address these interconnected challenges. In tea gardens specifically, biochar amendments have been shown to ameliorate soil acidity, improve soil aggregate stability, and increase soil organic carbon stocks over multiple years [

23,

26,

27]. Beyond these direct soil health benefits, biochar is increasingly recognized for its potential to mitigate climate change by altering the biogeochemical pathways governing GHG fluxes. For instance, several studies in tea plantations have documented significant reductions in N

2O emissions following biochar application [

28,

29]. These combined characteristics establish biochar as a promising tool for sustainable soil management, yet its specific impacts on GHG fluxes, particularly CH4, CO

2, and water-vapour flux within tea agroecosystems, remain poorly understood.

CH

4 fluxes in tea agroecosystems have often been considered negligible due to the general notion that tea soils are typically well-drained and aerobic [

30], and integrated analyses have not considered CH

4 [

6]. This perspective, however, may overlook the effects of common management practices, such as soil compaction from human traffic or heavy machinery and altered soil chemistry from agrochemical inputs, which can create conditions favorable to methanogenesis. Biochar applications can alter these conditions. By increasing soil porosity and aeration, biochar may enhance the activity of methanotrophic bacteria, thereby increasing the soil’s capacity to act as a CH

4 sink. Conversely, certain biochars can release phenolic compounds that inhibit methane oxidation [

31] or create anaerobic microsites within aggregates that could potentially support methanogenesis. Laboratory incubations of acidic tea soils have shown inconsistent results, with some studies reporting no significant effect of biochar on CH

4 fluxes [

32]. The interactive effects of biochar with shade tree canopies, which alter soil temperature and moisture, remain entirely unexplored, leaving a critical gap in predicting field-scale CH

4 dynamics.

The impact of biochar on soil respiration (CO

2 flux) in tea plantations is equally unresolved. While the primary benefit of biochar is the addition of recalcitrant carbon for long-term sequestration, its immediate effect on native soil organic carbon (SOC) mineralization is debated. The addition of labile carbon from fresh biochar can trigger a positive priming effect, stimulate microbial activity and temporarily increase CO

2 emissions [

29,

33]. In contrast, other studies suggest biochar can stabilize native SOC within newly formed aggregates, leading to a negative priming effect and reduced overall respiration [

26]. Field studies in tea gardens have yielded conflicting results: for instance, Wang et al. [

32] observed a decrease in CO

2 emissions from an acidic tea garden soil amended with biochar, whereas Han et al. [

34] found that manure application stimulated respiration far more than biochar did.

Potential interactions between biochar, GHG fluxes, and soil moisture dynamics have been almost entirely overlooked. Biochar is widely recognized for its ability to improve soil water retention [

24]. Studies have also generally found that biochar reduces soil evaporation [

35,

36]. However, prior studies have focused on agricultural systems and field measurements of soil water-vapour (H

2O) flux in response to biochar amendment in woody crops appear to be non-existent. Soil moisture is a key variable that controls the redox conditions governing CH

4 cycling and modulates microbial and root respiration, directly influencing CO

2 emissions [

37]. Understanding how biochar-induced changes in soil water flux interact with the microclimate modifications from shade trees is essential for assessing impacts on water-use efficiency and the coupled C and water cycles.

The present study provides the first field assessment of biochar’s effects on soil CO2, CH4, and H2O fluxes within a subtropical tea agroforestry system, utilizing a high-resolution, closed-dynamic chamber system and real-time gas analysis for flux measurements. The primary objectives were to: (1) quantify how biochar treatment influences the fluxes of soil CH4, CO2, and H2O vapour; (2) determine the extent to which soil physicochemical properties, such as pH, bulk density, moisture content, temperature, organic matter, and macronutrient concentrations (N, P, K), mediate these flux responses; (3) assess whether shade trees interact with biochar treatment to modulate soil CH4, CO2, and H2O vapour fluxes; and (4) evaluate the relative contributions of drivers (e.g., edaphic factors, presence of shade trees) in shaping flux patterns. We hypothesized that biochar amendment would significantly reduce net CH4 emissions by improving soil aeration while having a negligible effect on total soil respiration (CO2), reduce H2O vapour fluxes, and that the presence of shade trees would modulate these responses by creating cooler, moister soil conditions conducive to CH4 oxidation and by reducing soil respiration and evaporation.

3. Results

Measurements indicated moderate rates of soil CO2 efflux in the tea agroecosystem, with values ranging from 1.33–4.41 µmol m−2 s−1 (overall mean [±SE] 2.63 ± 0.06 µmol m−2 s−1). Soil evaporation rates were low to moderate, ranging from 10.2–276.4 µmol m−2 s−1 (overall mean 84.1 ± 3.2 µmol m−2 s−1), consistent with relatively low to moderate soil water content characteristic of the dry-season. Net CH4 oxidation was observed for all measurements, with values ranging from -3.55 to -0.19 nmol m−2 s−1 (overall mean -1.92 ± 0.07 nmol m−2 s−1).

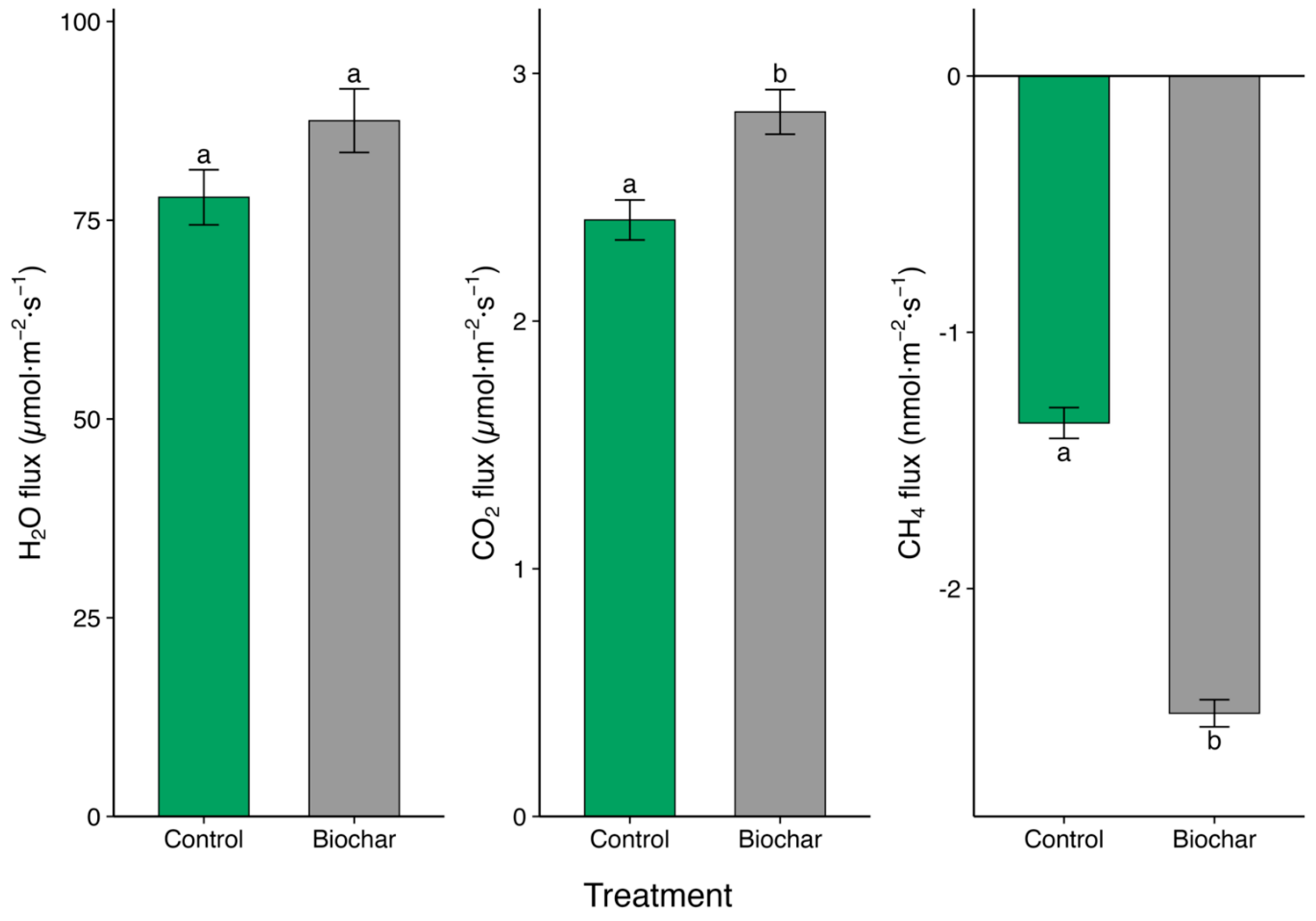

Biochar Effects on Soil CH4, CO2, and H2O Fluxes

Biochar addition (7.5 t ha

−1) significantly altered soil GHG exchange relative to the unamended control (

Figure 2). Mean CH

4 uptake shifted from –1.35±0.06 nmol·m

−2·s

−1 in control soils to –2.49±0.05 nmol·m

−2·s

−1 under the biochar addition treatment, an 84% increase in net uptake (p < 0.001) (

Figure 2c). Carbon-dioxide effluxes rose, from 2.41 ± 0.08 to 2.84 ± 0.09 µmol m

−2 s

−1—an 18% enhancement (p < 0.001) (

Figure 2b). Water-vapour flux exhibited only a marginally significant 12% rise (77.9±3.47 vs. 87.5±4.00 µmol m

−2 s

−1; p = 0.07) (

Figure 2a).

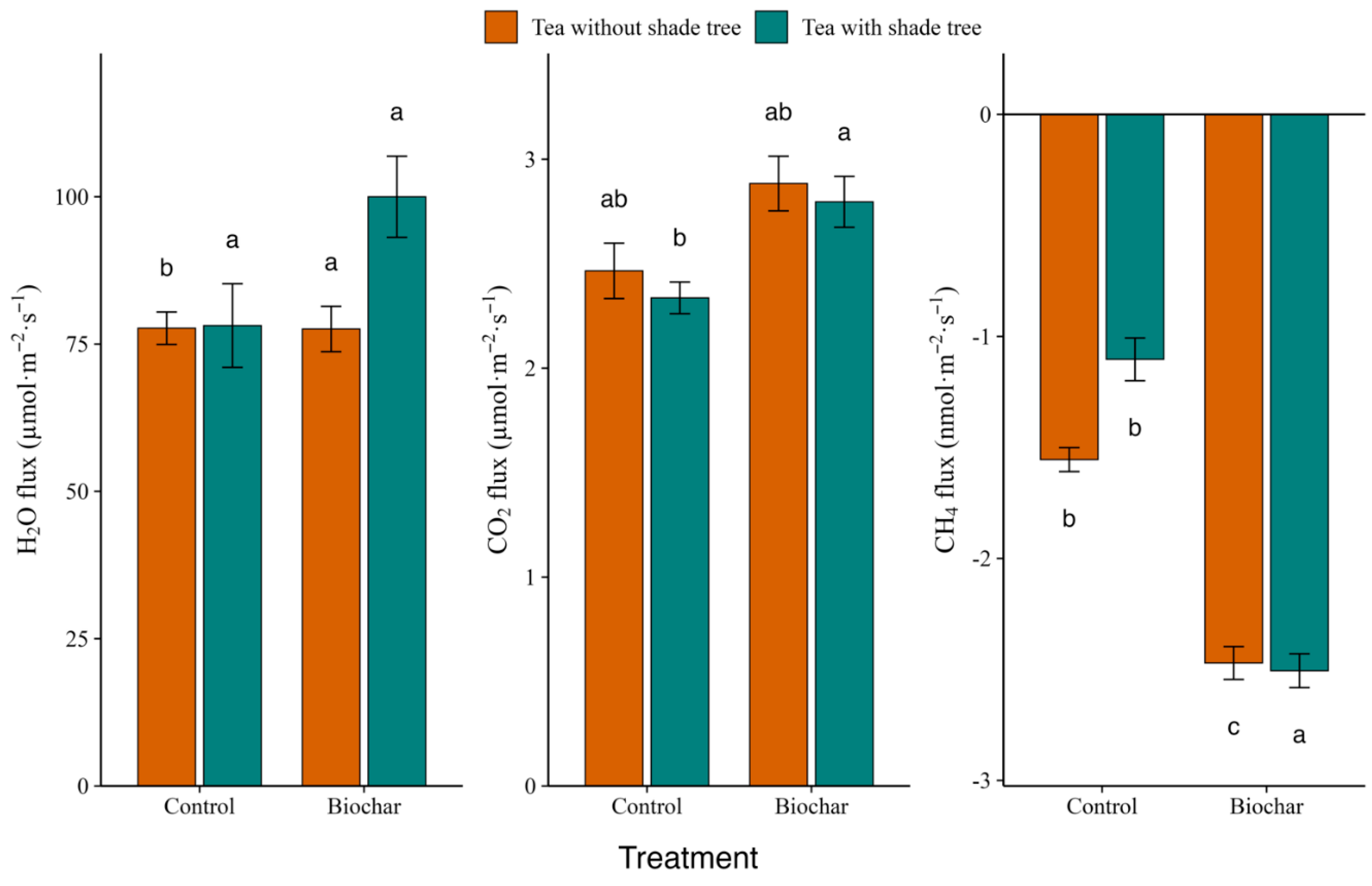

Interactive Effects of Biochar and Shade Trees on Soil GHG Exchange

A significant biochar × shade-tree interaction was detected overall for all three gases (mixed-effects model, p < 0.01), driven primarily by CH

4 and H

2O; for CO

2, post hoc comparisons indicated an additive pattern (i.e., shade lowered baseline flux but did not alter the biochar effect size) (

Figure 3). Net CH

4 uptake (

Figure 3c) was greatest in plots that received biochar but lacked shade trees (–2.51±0.08 nmol·m

−2·s

−1), marginally lower in shaded biochar plots (–2.47±0.07 nmol·m

−2·s

−1), and markedly weaker in the two control treatments (–1.55±0.05 nmol·m

−2·s

−1 without shade; –1.10±0.10 nmol·m

−2·s

−1 with). All four means differed at α = 0.05 (Tukey HSD).

Biochar addition resulted in elevated CO

2 efflux (

Figure 3b) under both canopy conditions, and shade did not modify the magnitude of the biochar response. Mean fluxes ranked as follows: unshaded + biochar 2.88 ± 0.13 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 ≈ shaded + biochar 2.80 ± 0.12 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 > unshaded control 2.47 ± 0.13 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 > shaded control 2.34 ± 0.08 µmol·m

−2·s

−1. Only the shaded control differed significantly from the other three groups, suggesting an additive—not synergistic—effect of the two factors.

Shade altered the biochar response for H

2O vapour flux (

Figure 3a). Unshaded biochar plots showed the highest H2O vapour loss (100 ± 6.8 µmol·m

−2·s

−1), significantly exceeding shaded biochar (77.6 ± 3.85 µmol·m

−2·s

−1; p = 0.014) and both control treatments (≈78 µmol·m

−2·s

−1, p < 0.03). Thus, biochar enhanced soil–atmosphere moisture exchange only when overstorey shade was absent.

Together these patterns indicate that biochar consistently strengthens CH4 uptake regardless of canopy, boosts CO2 efflux in an essentially additive fashion, and increases H2O flux only under full-sun conditions, highlighting the importance of canopy microclimate in mediating biochar effects.

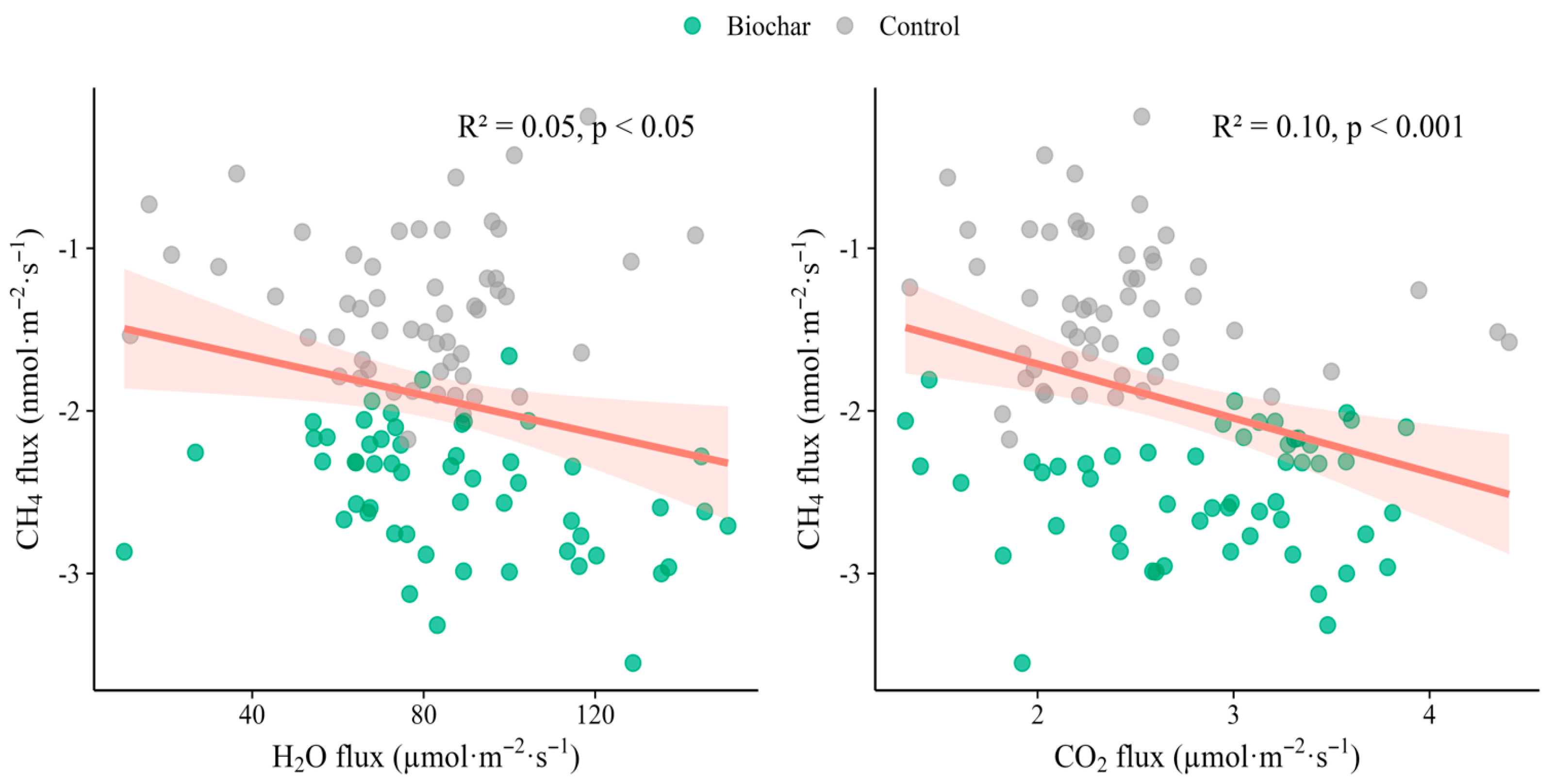

Relations Among CH4, CO2 and H2O Fluxes

Bivariate analyses showed that methane uptake was weakly but significantly coupled to the exchange of both H

2O vapour and CO

2 (

Figure 4). Across all collars and treatments CH

4 flux became more negative (i.e., uptake increased) as H

2O flux rose (slope = –0.006 nmol CH

4 m

−2 s

−1 per µmol H

2O m

−2s

−1, R

2 = 0.05, p = 0.03, Figure. 4a). A steeper inverse relationship was detected between CH

4 and CO

2 (slope = –0.333 nmol CH

4 m

−2 s

−1 per µmol CO

2 m

−2 s

−1, R

2 = 0.10, p < 0.001;

Figure 4b). Neither the slopes nor the intercepts differed between the biochar and control datasets (interaction terms, p > 0.1), so a single pooled regression is reported. These patterns suggest that conditions that stimulate soil respiration and water vapour loss—likely higher diffusivity and greater microbial activity—also favour methanotrophic CH

4 oxidation, reinforcing the fact that CH

4 dynamics are functionally integrated with broader carbon and moisture exchanges in this subtropical tea soil.

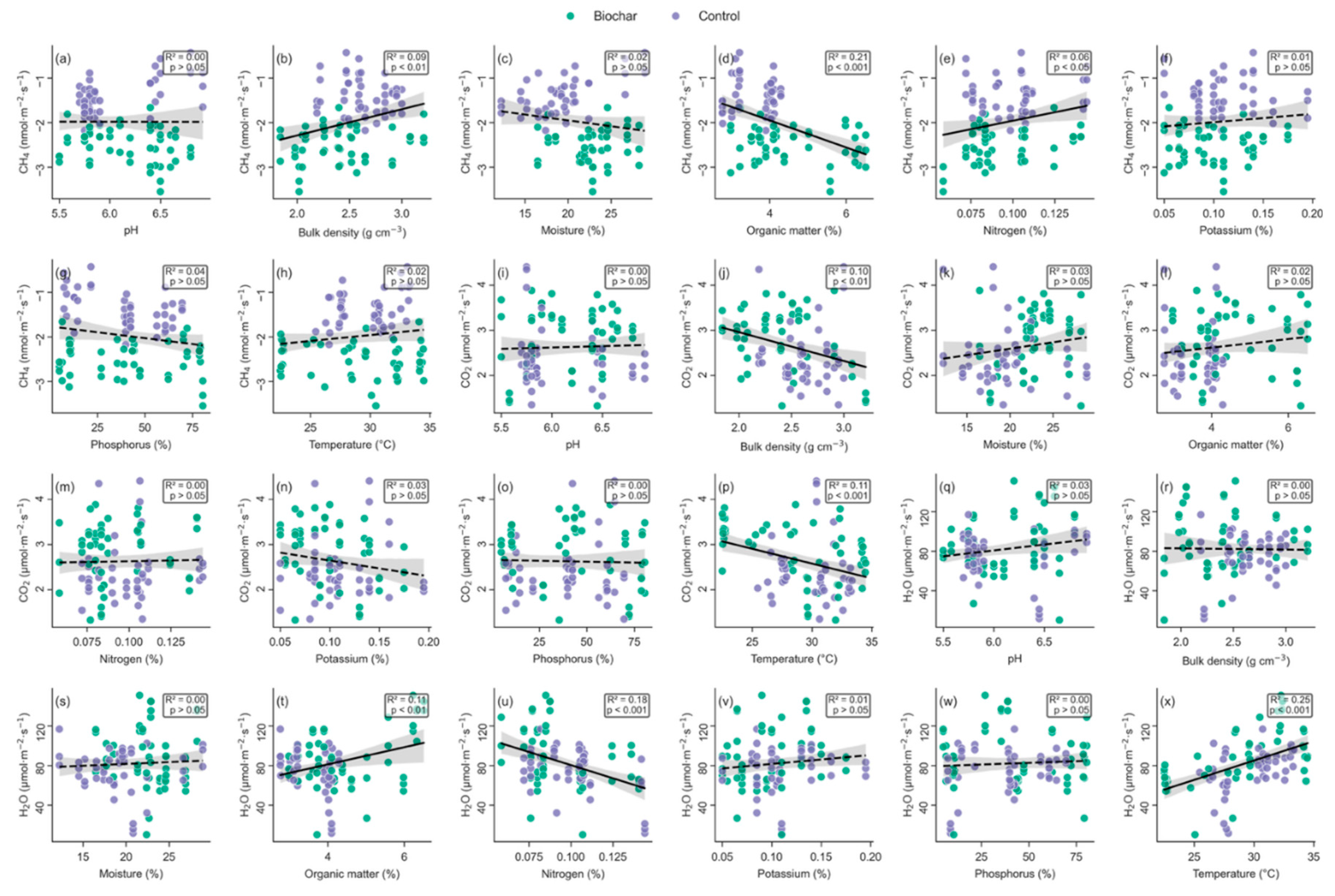

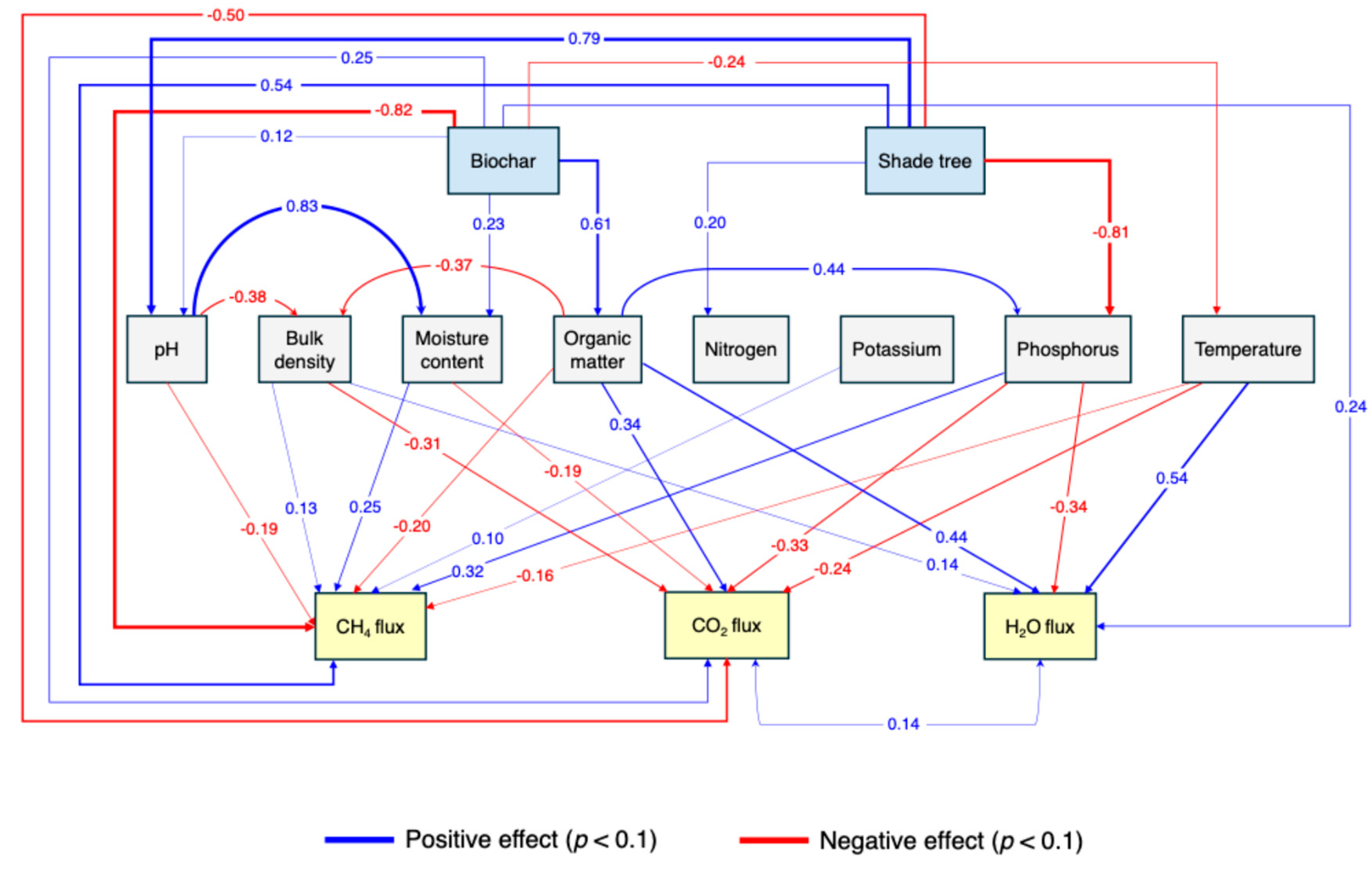

Soil Drivers and Mechanistic Pathways Governing Gas Exchange

The multivariate picture that emerged from the combined regression and structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) shows that each gas responds to a distinct but partially overlapping suite of soil and management factors.

For methane, the simple fits already pointed to strong physical and chemical constraints: CH

4 uptake declined as bulk density rose (R

2 = 0.09, p = 0.004,

Figure 5b), and it likewise weakened with increasing organic-matter content (R

2 = 0.21, p < 0.001,

Figure 5d) and total nitrogen (R

2 = 0.06, p = 0.02,

Figure 5e).

When these variables were embedded in the SEM (

Figure 6), the model captured 74.0% of the variance (R

2 = 0.74) and assigned the single largest path coefficient to the biochar treatment itself (β = –0.82, p < 0.001).

Positive paths from shade-tree presence (β = 0.54, p < 0.001), bulk density (β = 0.13, p = 0.055), gravimetric moisture (β = 0.25, p = 0.005), exchangeable K (β = 0.10, p = 0.010), and Bray-1 P (β = 0.32, p = 0.025) also increase uptake. Organic matter exerted a negative effect (β = –0.20, p = 0.023), indicating that the amendment reduces CH4 concentrations both directly and through the denser, moister, nutrient-enriched micro-environments it creates. Soil pH (β = –0.19, p = 0.081) and temperature (β = –0.16, p = 0.061) were marginally significant, suggesting additional minor constraints on CH4 oxidation.

The controls on CO

2 efflux were more diffuse. In the bivariate analysis CO

2 declined with bulk density (R

2 = 0.10, p = 0.004,

Figure 5j), decreased slightly with temperature (R

2 = 0.12, p < 0.001,

Figure 5p) and showed only a marginal tendency to fall with K (R

2 = 0.03, p = 0.08,

Figure 5n). The SEM, which explained 31.5% of the variance (R

2 = 0.315), refined these relationships: shade tree (β = –0.50, p = 0.003) and bulk density (β = –0.31, p = 0.008) exerted the strong suppressive effect, followed by Bray-1 P (β = –0.33, p = 0.014), temperature (β = –0.24, p = 0.039) and gravimetric moisture (β = –0.19, p = 0.042). In contrast, biochar (β = 0.25, p = 0.038) and organic matter (β = 0.34, p = 0.025) exerted a direct positive effect on soil CO

2 flux. These results suggest that CO

2 efflux is shaped more by physical structure and microclimate than by labile substrate pools, with some residual contribution from increased soil organic content.

For water-vapour flux, the collar-level regressions suggested a positive link with organic matter (R

2 = 0.11, p = 0.006,

Figure 5t) and a pronounced negative link with total N (R

2 = 0.18, p < 0.001,

Figure 5u). In the SEM, the strongest predictor was temperature (β = 0.54, p < 0.001), followed by organic matter (β = 0.44, p < 0.001). Bulk density showed a marginally positive effect (β = 0.14, p = 0.053), while biochar (β = 0.24, p = 0.015) had a significant direct influence on vapour fluxes. The model nonetheless accounted for 34.7% of the variance, suggesting that during the dry-season campaigns temperature and organic matter content outweighed the physical changes induced by the amendment in controlling vapour exchange.

Overall, the integrated analysis indicates that biochar regulates CH4 primarily by modifying soil structure and associated nutrient pools, that CO2 efflux is governed by the interplay of substrate availability and diffusional constraints imposed by canopy cover and soil compaction, and that H2O flux is driven chiefly by temperature and organic matter rather than by the amendment’s physical legacy.

4. Discussion

Our study provides the first field assessment of biochar’s effects on concurrent soil fluxes of methane, carbon dioxide, and water vapour within a tea agroforestry system, revealing a complex suite of responses. The most pronounced effect was a substantial 84% enhancement of soil methane uptake following a 7.5 t ha−1 biochar application. Concurrently, we observed a modest but significant 18% increase in soil respiration (CO2 efflux) and a marginal 12% rise in water-vapour flux. Crucially, the presence of a shade-tree canopy modulated these outcomes, with a significant biochar × shade-tree interaction detected for all three gases; notably, the increase in water-vapour flux occurred only in unshaded conditions. These findings offer partial support for our initial hypotheses; while the prediction of enhanced methane oxidation was confirmed, the observed increases in CO2 and water-vapour fluxes contradict our expectation that biochar would have negligible or suppressive effects on these emissions.

Biochar Drives a Major Methane Sink Capacity via Competing Physical and Chemical Pathways

The 84% increase in soil CH4 uptake stands out as the most significant biogeochemical response to biochar amendment in this study, transforming the tea garden soil into a substantially stronger CH4 sink. This finding is particularly noteworthy given that such well-drained upland tropical soils are not typically considered major players in the methane cycle. Our structural equation model (SEM), which explained 74.0% of the variance in CH4 flux, provides strong evidence that this effect is complex, driven by both direct and indirect mechanisms

The primary driver was the direct effect of the biochar amendment itself (path coefficient β = –0.82), indicating that the inherent physical properties of biochar were paramount. The high porosity and large surface area of biochar particles likely improved soil aeration and gas diffusivity, creating optimal conditions for methanotrophic bacteria to oxidize atmospheric CH

4. This aligns with findings from other managed temperate and boreal forests where biochar application has been shown to increase CH

4 uptake [

56,

57,

58]. A comprehensive review by Li et al. [

37] confirms that enhanced aeration is the most commonly cited mechanism for increased CH

4 consumption in forest soils amended with biochar. Consistent with this, our findings indicate that biochar treatment exerts the strongest negative effect on CH

4 flux (β = 0.31), thereby enhancing CH

4 uptake.

However, our data also reveal a critical trade-off. Biochar’s direct positive effect on moisture content (β = 0.23) had a suppressive effect (β = 0.25) on CH

4 oxidation. This suggests that while the bulk soil becomes better aerated, the fine biochar particles can fill pore spaces and hold water, creating anaerobic microsites that may inhibit the activity of aerobic methanotrophs. Furthermore, the weak but significant negative relationships between CH

4 uptake and soil organic matter suggest that the addition of nutrient-rich biochar may alter microbial competition in ways that slightly temper the overall CH

4 sink strength. A similar weak negative relationship was also observed with temperature, likely because temperatures notably suppress methanotrophic activity in upland soils, possibly due to the inhibition of mesophilic methanotrophs [

59].

This result contrasts sharply with other studies in acidic tea soils and tropical plantations where biochar had negligible or inconsistent effects on CH

4 fluxes [

29,

60], highlighting that the net impact is highly dependent on biochar properties, soil type, and ecosystem context. The powerful, multifaceted response observed in our study underscores that biochar’s role in the CH

4 cycle is not simply a matter of adding porous material, but a complex interplay between enhanced gas exchange and the creation of inhibitory, water-saturated and/or nutrient-rich microsites.

Increased Soil Respiration Driven by an Indirect Substrate Priming Effect

The observed 18% increase in soil respiration (CO

2 efflux) following biochar application, while seemingly counterintuitive to the goal of carbon sequestration, is best explained as a short-term, indirect “positive priming effect.”. The freshly pyrolyzed biochar, produced from

Acacia auriculiformis off cuts, likely contained a fraction of labile organic compounds such as volatile fatty acids [

61] that served as a readily available energy source for soil microbes. This infusion of new substrate can stimulate the microbial community, leading to accelerated decomposition of not only the labile biochar components but also of native soil organic matter [

29,

33].

Our SEM results support this interpretation, showing that CO

2 flux was strongly predicted by biochar treatment and organic matter content. Moreover, the SEM revealed another strong direct path from biochar to organic matter, implying biochar’s direct influence on soil respiration is primarily controlled through its effect on soil microbial community. While some studies have reported reduced CO

2 emissions with biochar through SOC stabilization [

26], our findings align with others that show a transient increase in respiration due to substrate effects [

34].

From a carbon management perspective, this initial pulse of CO2 represents a short-term carbon cost. However, this is expected to be far outweighed by the long-term climate benefit derived from the much larger recalcitrant carbon pool within the biochar that will remain stable in the soil for centuries. In addition, increased microbial activity is expected to be associated with increased nutrient mineralization that can increase net primary productivity. Nevertheless, this priming effect must be considered in full life-cycle assessments of biochar as a climate mitigation tool.

Biochar’s Contradictory Effect on Water-Vapour Flux: A Thermal Trade-Off

Our finding that biochar increased soil water-vapour flux by up to 12%—and significantly so in unshaded plots—is notable because it contrasts with the commonly reported pattern that biochar reduces soil evaporation [

35,

36]. Most prior work has been in agricultural row-crop systems, whereas woody perennial systems like tea have been understudied.

Our results strongly suggest this unexpected outcome is not driven by soil hydrology, but rather by a thermal effect at the soil surface. The structural equation model (SEM) identified soil temperature one of the significant predictors of H

2O flux (β = 0.54). We attribute this to the dark color of the surface-applied biochar, which increases the absorption of solar radiation and elevates soil surface temperature [

62], thereby accelerating evaporation.

This thermal mechanism accurately explains why the effect was only statistically significant in unshaded plots exposed to direct sunlight and was completely negated under the cooler, shaded canopy. This highlights a critical and context-dependent trade-off. While biochar is well-known for its ability to improve water retention within the soil profile, our findings indicate that when applied to the surface in exposed environments, its thermal properties can overwhelm its hydraulic benefits, leading to increased evaporative water loss during dry periods. This has significant implications for water-use efficiency, suggesting that the net benefits of biochar for soil moisture may depend heavily on its placement (e.g., surface vs. incorporated) and the specific canopy environment of the agroecosystem.

An Integrated Strategy: Combining Agroforestry and Biochar for Optimal Climate and Soil Benefits

The most significant insight from this study is the powerful synergy created by combining biochar with shade-tree agroforestry, revealing an integrated and highly effective path toward climate-smart tea production. Our findings demonstrate that an agroforestry system does not just coexist with biochar amendment but fundamentally improves its performance by mitigating its undesirable effects while locking in its key climate benefits. This highlights that the full potential of a soil amendment like biochar is only realized when it is deployed within a resilient, well-managed ecological system.

While biochar application alone successfully transformed the soil into a potent methane sink, it also came with the costs of increased carbon dioxide and water vapour emissions. However, the presence of shade trees acted as a critical environmental buffer. The canopy completely negated the biochar-induced increase in water evaporation by maintaining cooler soil temperatures, thereby conserving essential soil moisture. Furthermore, these cooler conditions under the canopy had a suppressive effect on soil respiration (β = –0.50), partially offsetting the temporary increase in CO2 caused by the biochar. Crucially, these benefits came at no significant cost to methane mitigation; CH4 uptake in shaded biochar plots remained high and was only marginally lower than in unshaded biochar plots.

From a land management perspective, this integrated approach is a near-optimal strategy. Biochar additions maximize the net greenhouse gas benefit by sustaining high methane uptake, support broader soil health by enhancing carbon cycling while conserving moisture, aligning with global goals for carbon neutrality and land restoration. By leveraging a biological solution (shade trees) to refine and enhance a technological one (biochar), this combined system provides a robust and actionable framework for building more sustainable and climate-resilient perennial cropping systems worldwide. Our results thus support the general case for strong benefits of biochar use in multi-species agroforestry systems [

63,

64].

While this study captures the pivotal dry-season response, it omits seasonal variation, biochar ageing, and N2O fluxes—critical elements of the complete GHG budget for tea systems. Long-term, multi-season trials that incorporate N2O dynamics, biochar placement depth, and tea yield-quality metrics are essential to validate durability and agronomic viability. Future work should also examine sub-surface or mulched biochar applications to decouple evaporation from soil warming and to test whether similar synergies arise in other perennial crops (coffee, cocoa, rubber) across tropical and subtropical regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MAH, NVG, and SCT; methodology, MAH, MRK, NVG, and SCT; software, MAH and MRK; formal analysis, MAH and MRK; investigation, MAH, MRK, and NVG; data curation, MAH and MRK; writing—original draft preparation, MAH; writing—review and editing, MAH, MRK, and SCT; supervision, SCT; funding acquisition, MAH, NVG, and SCT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

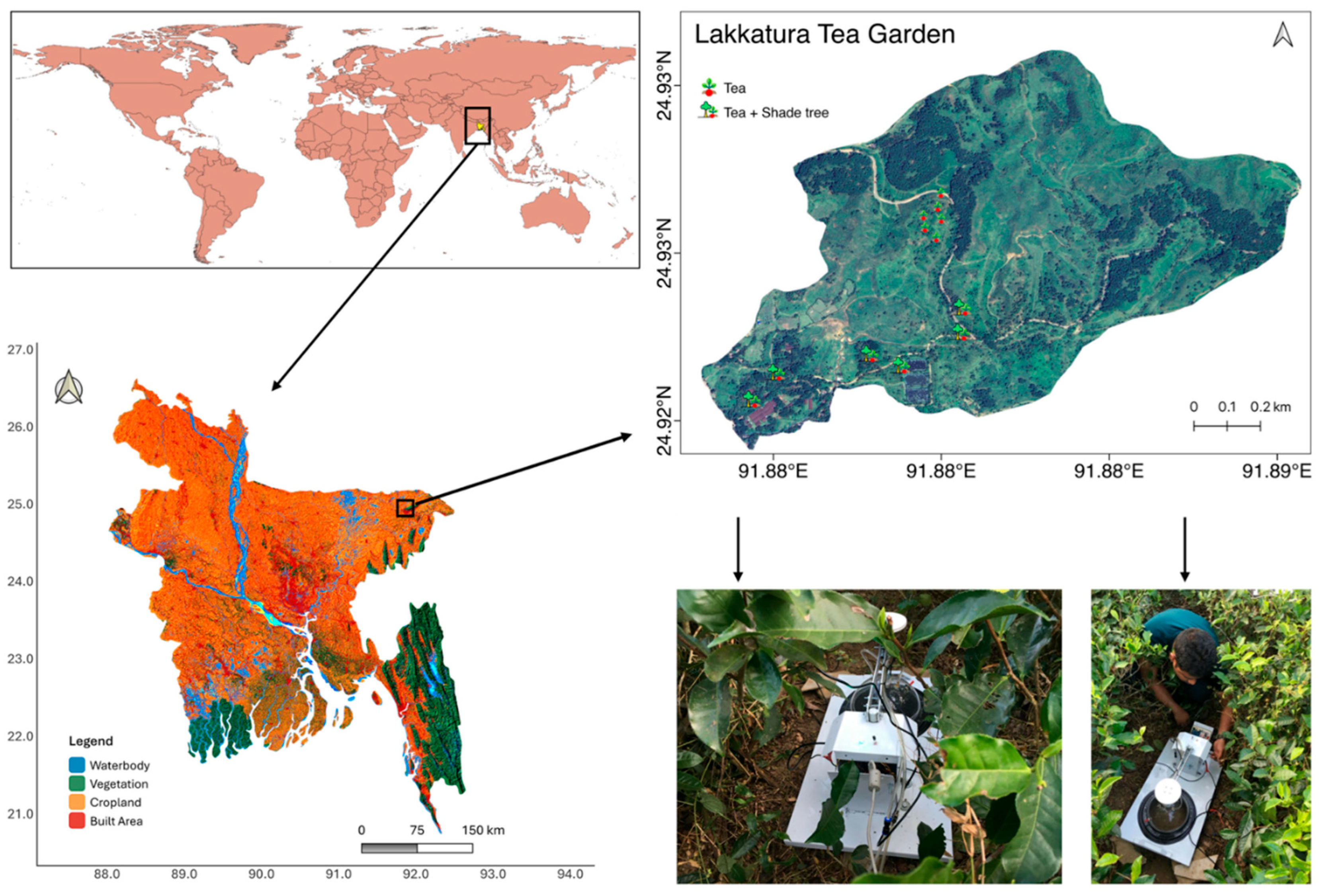

Figure 1.

Location of Lakkatura Tea Garden (Sylhet, north-eastern Bangladesh) and layout of the two experimental land-use systems. Monoculture tea plots (Camellia sinensis) and tea-based agroforestry plots (tea interplanted with Albizia odoratissima and Melia azedarach) that each received 7.5 t ha-1 biochar are delineated.

Figure 1.

Location of Lakkatura Tea Garden (Sylhet, north-eastern Bangladesh) and layout of the two experimental land-use systems. Monoculture tea plots (Camellia sinensis) and tea-based agroforestry plots (tea interplanted with Albizia odoratissima and Melia azedarach) that each received 7.5 t ha-1 biochar are delineated.

Figure 2.

Effect of biochar addition (7.5 t ha−1) on soil GHG fluxes in a tea garden ecosystem. Bars show treatment means ± SE calculated from 30 collar measurements per treatment (5 collars × 3 plots × two campaigns) for (a) water vapour and (b) CO2 fluxes expressed in µmol m−2 s−1, and (c) CH4 flux expressed in nmol m−2 s−1. Positive values indicate net emission; negative values indicate net uptake. Columns sharing the same lowercase letter do not differ significantly (Tukey HSD, α = 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of biochar addition (7.5 t ha−1) on soil GHG fluxes in a tea garden ecosystem. Bars show treatment means ± SE calculated from 30 collar measurements per treatment (5 collars × 3 plots × two campaigns) for (a) water vapour and (b) CO2 fluxes expressed in µmol m−2 s−1, and (c) CH4 flux expressed in nmol m−2 s−1. Positive values indicate net emission; negative values indicate net uptake. Columns sharing the same lowercase letter do not differ significantly (Tukey HSD, α = 0.05).

Figure 3.

Interactive effect of biochar and shade-tree overstory on soil–atmosphere gas exchange. Bars show means ± SE for (a) H2O vapour and (b) CO2 fluxes (µmol m−2 s−1) and (c) CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1) in tea monoculture (brown) and tea + shade-tree agroforestry (teal) plots receiving either 0 t ha−1 (Control) or 7.5 t ha−1 (Biochar) amendments. Each mean is based on 30 collar measurements per treatment combination (five collars × three plots × two campaigns). Positive values denote net emission; negative values denote net uptake. Columns that share a lowercase letter do not differ significantly (mixed-effects model followed by Tukey HSD, α = 0.05).

Figure 3.

Interactive effect of biochar and shade-tree overstory on soil–atmosphere gas exchange. Bars show means ± SE for (a) H2O vapour and (b) CO2 fluxes (µmol m−2 s−1) and (c) CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1) in tea monoculture (brown) and tea + shade-tree agroforestry (teal) plots receiving either 0 t ha−1 (Control) or 7.5 t ha−1 (Biochar) amendments. Each mean is based on 30 collar measurements per treatment combination (five collars × three plots × two campaigns). Positive values denote net emission; negative values denote net uptake. Columns that share a lowercase letter do not differ significantly (mixed-effects model followed by Tukey HSD, α = 0.05).

Figure 4.

Bivariate relationships between methane uptake and co-emitted gases. (a) Relation between CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1) and water-vapour flux (µmol m−2 s−1); (b) relation between CH4 and CO2 flux (µmol m−2 s−1). Grey symbols = Control; green symbols = Biochar (7.5 t ha−1). Each point is the mean of the three consecutive fluxes from a single collar (n = 60 per panel). The solid red line is the ordinary-least-squares regression fitted to the pooled data; the shaded band is the 95% confidence envelope. Regression statistics (R2, p, equation) refer to this overall fit. Negative CH4 values denote net soil uptake.

Figure 4.

Bivariate relationships between methane uptake and co-emitted gases. (a) Relation between CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1) and water-vapour flux (µmol m−2 s−1); (b) relation between CH4 and CO2 flux (µmol m−2 s−1). Grey symbols = Control; green symbols = Biochar (7.5 t ha−1). Each point is the mean of the three consecutive fluxes from a single collar (n = 60 per panel). The solid red line is the ordinary-least-squares regression fitted to the pooled data; the shaded band is the 95% confidence envelope. Regression statistics (R2, p, equation) refer to this overall fit. Negative CH4 values denote net soil uptake.

Figure 5.

Bivariate relations between soil properties and gas fluxes in biochar-amended (green) and control (purple) tea plots. Columns show, from left to right, soil pH, bulk density (g cm−3), gravimetric moisture (%), organic-matter content (%), total nitrogen (%), exchangeable potassium (%), Bray-1 phosphorus (%), and soil temperature (oC). Rows give (a–h) CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1; negative values = net uptake), (i–p) CO2 flux (µmol m−2 s−1), and (q–x) H2O-vapour flux (µmol m−2 s−1). Each symbol is the collar-level mean of three consecutive flux values (n = 60). Ordinary-least-squares regressions were fitted to the pooled data; solid black lines indicate significant relationships (p < 0.05), and dashed lines denote non-significant trends. Shaded bands are 95% confidence envelopes, and inset boxes report model R2 and two-tailed p values for each panel.

Figure 5.

Bivariate relations between soil properties and gas fluxes in biochar-amended (green) and control (purple) tea plots. Columns show, from left to right, soil pH, bulk density (g cm−3), gravimetric moisture (%), organic-matter content (%), total nitrogen (%), exchangeable potassium (%), Bray-1 phosphorus (%), and soil temperature (oC). Rows give (a–h) CH4 flux (nmol m−2 s−1; negative values = net uptake), (i–p) CO2 flux (µmol m−2 s−1), and (q–x) H2O-vapour flux (µmol m−2 s−1). Each symbol is the collar-level mean of three consecutive flux values (n = 60). Ordinary-least-squares regressions were fitted to the pooled data; solid black lines indicate significant relationships (p < 0.05), and dashed lines denote non-significant trends. Shaded bands are 95% confidence envelopes, and inset boxes report model R2 and two-tailed p values for each panel.

Figure 6.

Covariance-based structural-equation model of controls on soil GHG exchange. Rectangles represent measured variables: biochar treatment, shade-tree presence, and eight soil properties (pH, bulk density, gravimetric moisture, organic matter, total N, exchangeable K, Bray-1 P, and soil temperature) are exogenous predictors; CH4 uptake, CO2 emission, and H2O-vapour flux are endogenous responses. Solid lines depict direct effects retained in the final model (standardized path coefficients printed alongside the arrows), whereas dashed lines indicate significant covariances between predictors. Blue arrows denote positive effects, red arrows negative effects; only paths with p ≤ 0.10 are shown. The model was based on 60 collar-level observations and provided acceptable fit (χ2 = 0.54, df = 14.86, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.989; RMSEA < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Covariance-based structural-equation model of controls on soil GHG exchange. Rectangles represent measured variables: biochar treatment, shade-tree presence, and eight soil properties (pH, bulk density, gravimetric moisture, organic matter, total N, exchangeable K, Bray-1 P, and soil temperature) are exogenous predictors; CH4 uptake, CO2 emission, and H2O-vapour flux are endogenous responses. Solid lines depict direct effects retained in the final model (standardized path coefficients printed alongside the arrows), whereas dashed lines indicate significant covariances between predictors. Blue arrows denote positive effects, red arrows negative effects; only paths with p ≤ 0.10 are shown. The model was based on 60 collar-level observations and provided acceptable fit (χ2 = 0.54, df = 14.86, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.989; RMSEA < 0.001).