1. Introduction

Ophiolitic complexes are of particular interest as they represent key tectonic windows into the oceanic lithosphere. This makes them crucial in understanding processes such as mantle melting, the movement of melt extraction, and the evolution of supra-subduction zone dynamics [

1,

2] . The Bou Azzer inlier in the Central Anti-Atlas of Morocco is a classic Pan-African ophiolitic massif, widely recognised as a site that offers a window into the Neoproterozoic oceanic lithosphere and subsequent obduction onto the West African Craton [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]

The inlier contains a tectonically dislocated assembly of mantle peridotites, mafic-ultramafic cumulates, sheeted dikes, pillow lavas, and related accretionary mélange. It is cut by synkinematic to postkinematic calc-alkaline granitoids and overlain by sediments [

12]. These units have been well described by [

13]. Among the above-listed lithologies, serpentinites are the main composition of the mantle portion, and their investigation is fundamental in unraveling the thermal, chemical, and mechanical ophiolite evolution. Serpentinites are widely distributed within the Bou Azzer ophiolite assemblage and form a significant part of its basement complex. Petrographic aspects have been investigated in several studies [

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14] . Although mantle-derived rocks in the West African Craton (WAC) provide key records of Precambrian mantle geodynamics, the origin and tectonic history of the Bou Azzer peridotites remain debated. This is largely due to extensive serpentinization and the scarcity of preserved primary minerals[

8,

9,

13,

14,

15]. Consequently, different tectonic settings have been proposed for these ophiolitic peridotites [

11,

12,

13,

15]. Despite the controversial genetic models, the tectonic history of Bou Azzer is well known in detail. A major Pan-African folding phase (B1) is responsible for isoclinal folds and schistosity with epizonal metamorphic (green-schist to amphibolite facies). A last Pan-African folding phase (B2) is responsible for upright fold, slaty cleavage, and transcurrent faulting [

7,

12,

16]. This story is a part of the Anti-Atlas and WAC northern boundary [

7].

Serpentinization is a significant characteristic of the rheological evolution of subduction regions, impacting the global fluid dynamics and contributing to the adjustment of reducing conditions that are favorable for metal transport and the direction of mineral deposits [

17,

18]

Systematic chemical changes in the peridotites and their mineral compositions are essential to deduce the degree of fusion and the metasomatic signatures of the mantle [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The incompatible trace element properties take into account not just the nature and type of metasomatic agents, but also the chemical modifications that arise during fluid/melt–mantle rock interactions [

24]. Otherwise, the distribution of compatible elements (e.g., Sc, V, Ti, and heavy rare earth elements (HREE)) is used to estimate the melting and depletion in the melt of the mantle peridotite [

25].

Integrated petrographic, mineralogical, and geochemical analyses on serpentinites offer valuable information regarding the composition of the protolith in the mantle, the extent of partial melting, fluid/rock interactions, and the ensuing metamorphic conditions resulting from obduction and subsequent transpressional events. In this paper, we present and interpret new petrological, mineral chemistry, and geochemical data of serpentinites and associated chromitites of the Bou Azzer ophiolite to characterize the geodynamic context of the Bou Azzer ophiolitic complex. This helps to understand the evolution of the Neoproterozoic mantle beneath the WAC.

2. Geological Setting of the Study Area

The West African Craton (WAC) covers almost all of West Africa. It is a Paleoproterozoic craton where some of the oldest rocks outcrop [

26,

27,

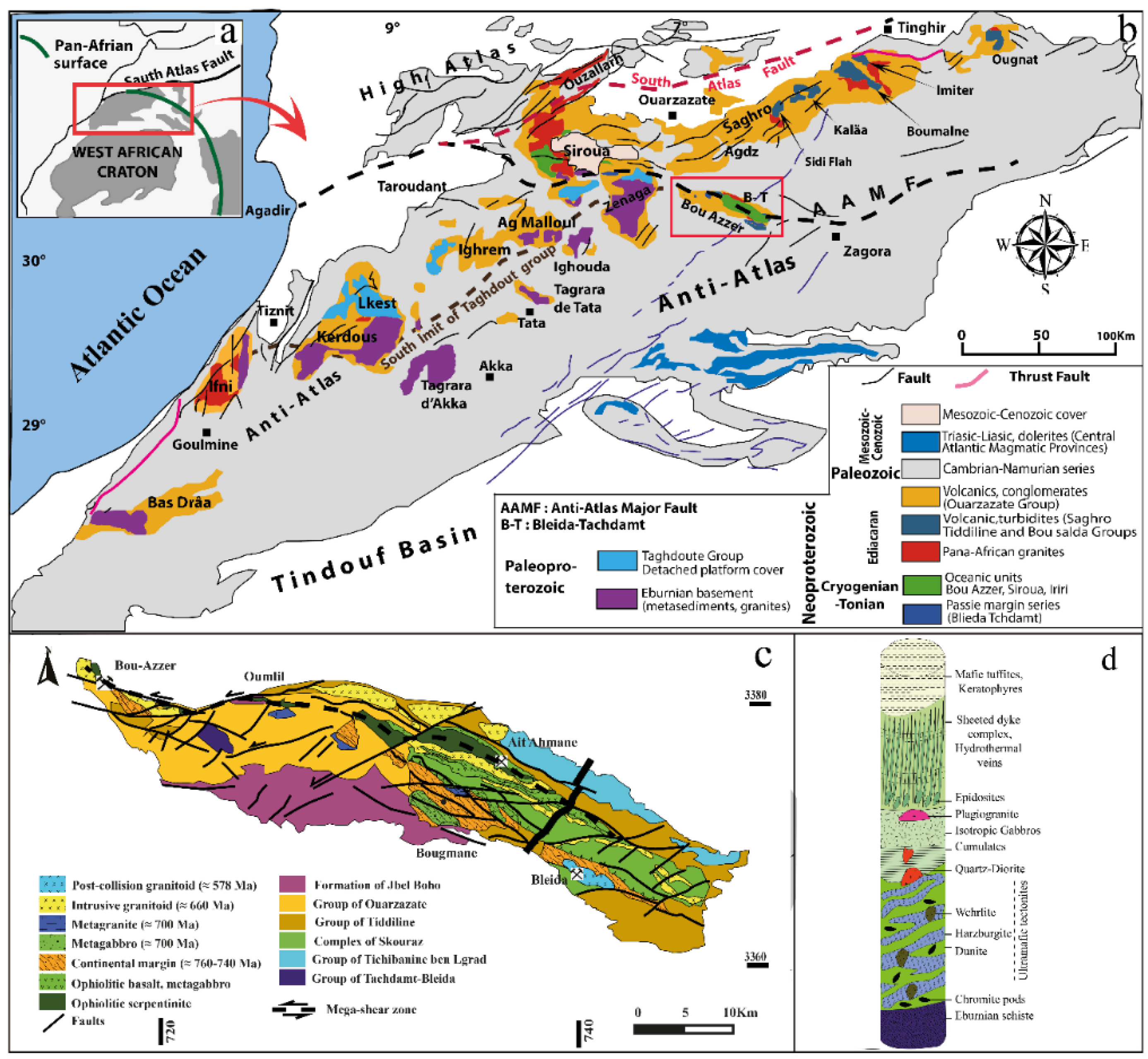

28]. The Anti-Atlas (ENE-WSW) is part of the WAC and lies in southern Morocco (

Figure 1a). It comprises a succession of inliers in the form of Proterozoic cores overlain by Paleozoic terrains [

29]. The Major Anti-Atlas Fault (MAAF) separates two domains; only the Neoproterozoic terrains are exposed in the eastern Anti-Atlas, whereas the Paleoproterozoic basement is exposed in the western Anti-Atlas [

3,

4,

12,

16,

29,

30], which is overlain or intruded by Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks, pyroclastic rocks, and granitoids [

31].

The Anti-Atlas domain has been affected by four major orogenic cycles, each of which had a distinct imprint on different parts of the Moroccan Anti-Atlas. The Eburnean orogeny [

26,

27,

28] is primarily recorded in the western Anti-Atlas, where Paleoproterozoic basement rocks underwent deformation and metamorphism, forming part of the West African Craton. The Pan-African orogeny [

3,

16,

30,

32,

33] had a profound influence across the entire Anti-Atlas, particularly through the development of Neoproterozoic ophiolitic and volcanic arc complexes, especially in the central and eastern regions. This orogeny led to the structuring of major shear zones and the emplacement of granitoids. The Variscan cycle [

34] mainly affected the northern margins of the Anti-Atlas, leading to localized deformation, folding, and the reactivation of older structures. Finally, the Alpine orogeny [

35] induced uplift and rejuvenation of fault systems, particularly evident in the southern parts and the bordering High Atlas, where neotectonic activity has shaped much of the current relief. This multi-orogenic history has led to a complex geological architecture, where each cycle contributed differently to the structural and lithological configuration of the Anti-Atlas.

The Bou Azzer-El Graara inlier is located in the central Anti-Atlas, 45 km as the crow flies SW of the city of Ouarzazate (

Figure 1b, c). This inlier marks the major accident of the Anti-Atlas. The Bou Azzer inlier is located between Latitudes 30°31'12" and 30°21'39.57" N, and longitudes 6°54'36" and 6°27'39.37" W, with an altitude of 1350 m, where a semi-desert climate prevails. Within this inlier (

Figure 2a), formations attributed to the Tachdamt Bleida Group and the Tazzegzout group at Bou Azzer show Tonian and early Cryogenian dates 900-700 Ma [

7,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Two active arcs dating to the Cryogenian are described. The first Arc in the north has been grouped as the Tichinbanine Ben Lagrad Group and consists of a complex tectonic assemblage of metagreywackes, basalts, andesites, rhyolites, and tuffs. It is dated between 761 ± 7 Ma and 767 ± 7 Ma [

5,

38,

40,

41,

42]. The second one in the south, attributed to the Bougmane Bou Azzer Group (Tazzegzout Group), consists of orthogneiss, metagabbro, schist, and pegmatite [

7,

37,

38].

The Pan-African orogenic cycle began with a north-dipping subduction around 760 Ma, followed by the obduction of the ophiolitic sequence onto the Gondwana margin [

7,

43,

44]. This ophiolitic sequence is defined as a Neoproterozoic suture zone, composed of a highly dismembered ophiolitic complex [

3,

4,

12,

13,

16,

30,

45].

The ophiolitic sequence, attributed to the Cryogenian Bou Azzer Group, consists of serpentinized peridotites containing podiform chromitites, layered gabbros, diabase dykes, and associated sedimentary rocks (Figure1 a-d). This sequence was intruded by syn-orogenic quartz-dioritic formations dated to 660–640 Ma [

38,

40,

46,

47,

48], and by a post-orogenic gabbrodiorite with an age of 594 ± 1.2 Ma [

38,

47].

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the Anti-Atlas belt at the boundary of the West African craton (WAC). (

b) Simplified geological map of the Anti-Atlas showing location of study area Gasquet et al., 2008 [

49], modified by Soulaimani et al. (2018) [

50]. (

c) Geologic map of the Bou-Azzer inlier showing the localization of the mining works. Modified from Leblanc (1981) [

13], Oberthur et al. (2009) [

51], and Blein et al. (2014) [

38], by Wafik et al. (2025) [

11]. (

d) Stratigraphic column for Bou Azzer ophiolite, showing lithostratigraphic units and characteristic lithologies completed from Wafik et al. (2025)[

11] and references therein.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the Anti-Atlas belt at the boundary of the West African craton (WAC). (

b) Simplified geological map of the Anti-Atlas showing location of study area Gasquet et al., 2008 [

49], modified by Soulaimani et al. (2018) [

50]. (

c) Geologic map of the Bou-Azzer inlier showing the localization of the mining works. Modified from Leblanc (1981) [

13], Oberthur et al. (2009) [

51], and Blein et al. (2014) [

38], by Wafik et al. (2025) [

11]. (

d) Stratigraphic column for Bou Azzer ophiolite, showing lithostratigraphic units and characteristic lithologies completed from Wafik et al. (2025)[

11] and references therein.

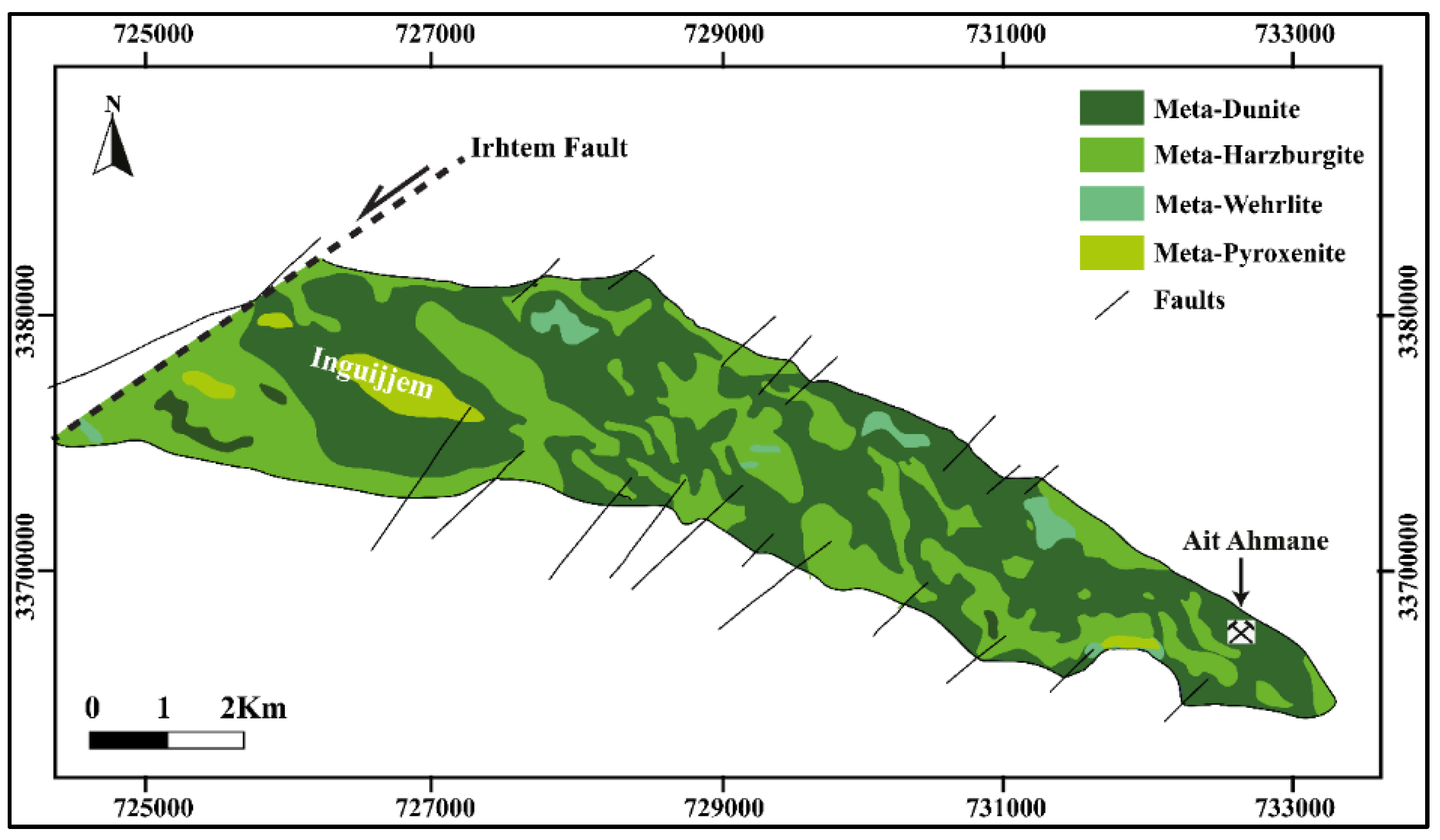

Figure 2.

Geological map of Ait Ahmane Inguijem ultramafic tectonites.

Figure 2.

Geological map of Ait Ahmane Inguijem ultramafic tectonites.

Supra-subduction zone peridotites represent highly depleted rocks formed in the sub-arc region either from the subducted slab or mantle wedge and characterized by a high degree of partial melting (

̴15 to 40%) [

52]. Abyssal peridotites are suggested to be a residual product of variable degrees of mantle melting (<20%) resulting from decompression and melt extraction processes beneath the mid-ocean spreading centers [

21,

53,

54,

55].

Although a great deal of research has been carried out on serpentinites (exposed mantle peridotites on land, particularly of Precambrian age) from the Bou Azzer, the central Anti-Atlas, in terms of their tectonic settings [

8,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

56], there is still little information available about their mantle magmatic processes and geodynamic evolution.

3. Analytical Methods

The main objective of this work was to make a geological update of the Bou Azzer ophiolite to bring new petrological and geochemical data on serpentinites. For this, different investigation techniques have been implemented on these targets. A sampling at the surface, at the trench, and on the drill core SC08 / -77 °, SC09 / -85 °, and SC06 / -90 ° in the different facies encountered. Making thin sections: more than 40 completed samples and Atomic Spectrometry and ICP-MS for whole rock chemistry, and 20 samples for XRD to see the mineralogical composition of serpentine rocks.

Samples were collected on each of the different areas to perform mineralogical analysis using microscopic observations on polished thin sections (Faculty of Science, Semlalia, Marrakech). Thin blades were performed and studied. They were then studied using an optical microscope. Complementary mineral characterization has been performed using micro-Raman spectroscopy (SOL instruments Confotec MR 520) with a laser of wavelength λ = 532 nm was used on thin sections and a scanning electron microscope or SEM (Tescam), in the Center of Analysis and Characterization, Marrakech University (CAC).

XRF analyses were carried out on all the slides to obtain their full spectrum. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were collected with a Rigaku SmartLab SE, X-ray diffractometer with monochromatized incident Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1:5418 Å) at 20keV and 10mA, and equipped with a x’Celerator detector of active length of 2.112º at the Center of Analysis and Characterization of the University of Marrakesh (Morocco). The patterns were obtained by scanning powders from 5°-90° 2θ on samples crushed to a particle size < 20µm. The mineral identification software used was OriginPro 2019 and X’Pert High Score Plus.

Subsequently, microprobe analyses are carried out to evaluate the contents of major, minor, and trace elements in the chromites. The experimental conditions of analysis are generally set at 20kV for the accelerating beam voltage, a beam current of 15 to 30 nA, and an acquisition time between 10 and 20 s for each element. Usually, the standards used are the pure metallic phases of each element.

Atomic Spectrometry and ICP-MS for whole-rock chemistry are used at Reminex, Managem Group, to give geochemical rock composition. The exact mineralogical composition of chromite and serpentinite facies was carried out with Electron Microprobe analysis, Camebax (Department of Petrology and Mineralogy, Paris VI, microanalyse laboratory, University of Paris VI). Jussieu and a JEOL JXA-8800 electron microprobe of Service Commun de Microscopies Electroniques et de Microanalyses X, Faculty of Sciences and Technologies, Lorraine University, Nancy, France, using a wavelength dispersive X-ray spectrometry at Nancy University, France. The analytical conditions were 15 kV accelerating voltage, 20 nA probe current, and 3 μm beam diameter. Most elements were measured with a counting time of 10s.

Back-Scattered Electron (BSE) and Secondary Electron (SE) images of polished thin sections were obtained using a Tescan VEGA3 thermionic emission SEM system that comes either with tungsten heated filament or lanthanum hexaboride (LaB6) as an electron source and a Field Emission SEM equipped with a high-resolution panchromatic detector CL at 185-850 nm and High a drift silicon drift EDS system (Cadi Ayyad University, Morocco). These instruments were operated under conditions of 20 kV (accelerating voltage).

4. Results and Analysis

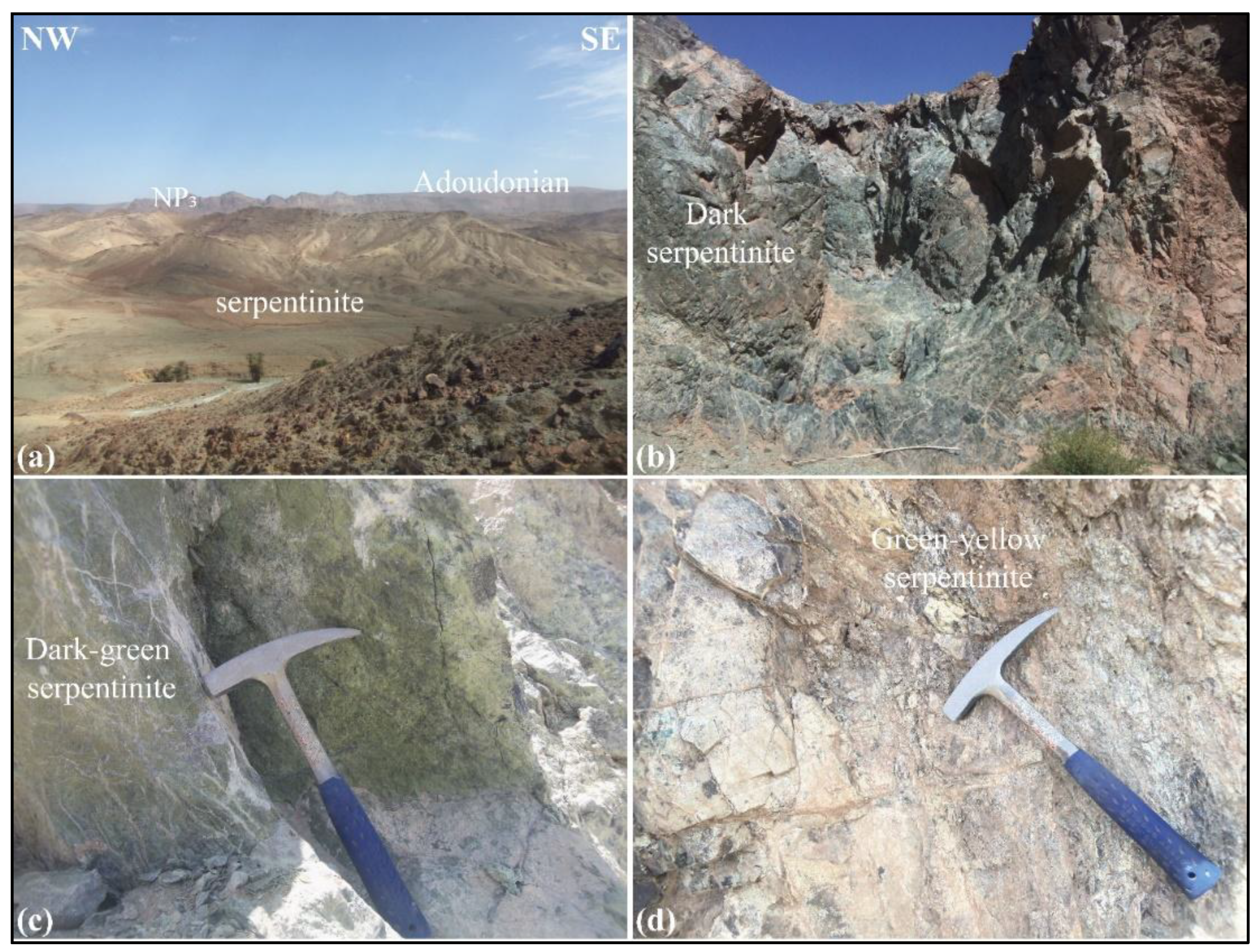

4.1. Lithology

The Bou Azzer inlier is characterized by the abundant occurrence of serpentinites, which represent a key component of the Neoproterozoic ophiolitic complex. These serpentinites are exposed as WNW–ESE-trending belts, typically forming steeply dipping sheets or lenses emplaced along major thrust faults. They occur within a distinct lithological assemblage that includes ultramafic cumulates, layered metagabbros, and schistose metavolcanic rocks (

Figure 2).

The Bou Azzer serpentinites originated through the hydrothermal alteration of peridotitic protoliths (harzburgites, dunites) and constitute the mantle sequence of the ophiolitic complex. They lie in tectonic contact with basic rocks, including ultramafic and mafic cumulates, gabbros and microgabbros, and quartz diorites. The contact is well-exposed at the surface, dipping 60–80° to the north, locally delineated by an alteration halo. The serpentinite bodies are elongate, with a WNW–ESE trend.

Two main sets of structural planes have been observed. The first set consists of nearly subhorizontal fractures, oriented N130° with a dip of 20° to the southwest. The second set is composed of subvertical fractures trending N190° and dipping 60° to the northwest. Magnetite occurs either as a filling material within these fractures or as fine disseminations throughout the serpentinized matrix. In some cases, magnetite forms discrete pockets reaching up to 5 cm in diameter. A distinct band of serpentinite, located parallel to the contact with adjacent gabbroic rocks, exhibits intense carbonation. This band is crosscut by millimetric chrysotile veinlets arranged in a mesh texture, typical of advanced serpentinization.

Field observations confirm that all surface outcrops are completely serpentinized, with no fresh primary ultramafic rocks currently exposed. However, according to the geological map (

Figure 3) and drill core data, primary lithologies such as gabbros and, more rarely, dunites, are still preserved at depth in certain areas. These preserved lithologies help reconstruct the original architecture of the ophiolite. The serpentinites display a wide range of macroscopic features, particularly in terms of color and texture. They vary from black to dark green, to light green, and occasionally grayish tones. This color variation likely reflects differences in the degree of serpentinization, meteoric weathering, or tectonic deformation associated with serpentinite flow. At the hand specimen scale, foliated and massive serpentinites can be distinguished. Along faults and shear zones, serpentinites are often altered to talc-carbonates and listvenites.

4.1.1. Petrography of the Bou Azzer Serpentinites

At the macroscopic scale, the serpentinites appear as elongate bands of dark green to yellow-green. Two main types of serpentinites are distinguished: Green serpentinites, interpreted as serpentinized harzburgites with a tectonite texture, which outcrop as discontinuous bands aligned parallel to the inlier's structural axis. Green-yellow serpentinites, corresponding to serpentinized dunites, typically occur as lenses or bands. More rarely, dark serpentinites are observed, which are possibly derived from serpentinized wehrlites. Wehrlite serpentinites, less frequent, occur in lenses or bands parallel to the inlier axis and give a massive aspect. Most serpentinites are intensely fractured, showing two principal fracture systems that often intersect at variable angles and are commonly filled with secondary magnetite.

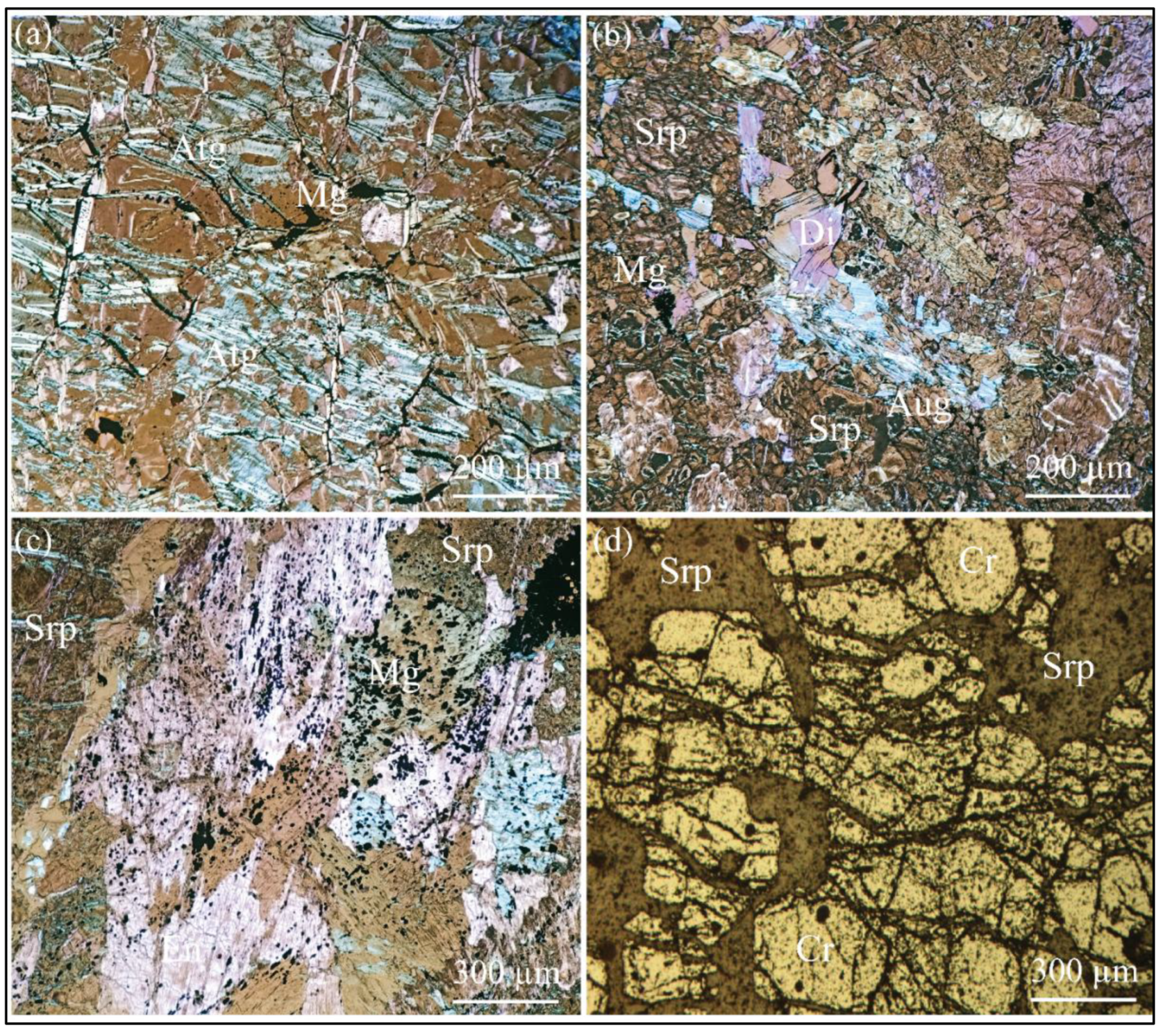

Microscopic and analytical investigations (optical microscopy and X-ray diffraction) All samples are completely serpentinized, with massive to sheared texture (

Table 1;

Figure 4). These investigations reveal that the serpentinites are primarily composed of antigorite, lizardite, and chrysotile, with variable amounts of chromian spinel, magnetite, carbonates, and talc.

Under the microscope, the serpentinites are largely characterized by a dark matrix mesh and reticulated textures, dominated by antigorite (

Figure 4a). In almost all samples, serpentinization is complete, with spinel being the only primary mineral locally preserved, the serpentine spindles having entirely replaced bastite (

Figure 4b and c). Chrysotile and calcite, and talc usually grow along veins that crosscut the early serpentine minerals and their boundaries (

Figure 4a- c). Associated chromitites are brecciated and sheared (

Figure 4d).

The massive serpentinite type reveals a pseudomorphic mesh texture crosscut by millimetric to centimetric chrysotile veinlets, while the sheared and foliated varieties show thinly recrystallized serpentine lamellae (Figs. 3 and 4). Matrix under the microscope is primarily antigorite and chrysotile, with 5–10% bastite pseudomorphs after pyroxene and olivine (

Figure 4b-c) in metadunite. Bastite textures are common in both harzburgite and wehrlite serpentinites, exhibiting granular extinction (

Figure 4b, c). Microscopically, they are dominated by antigorite with chrysotile veinlets and retain 10–25% bastite (

Figure 4c). Chromite in serpentinite, replaced in part or wholly by magnetite, is strewn through the matrix (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Idiomorphic magnetite crystals are ubiquitous, either occurring within serpentine mesh textures or along pyroxene cleavage traces and sometimes forming microscopic to macroscopic networks crosscutting the mesh texture. Talc and carbonates occur both as serpentine replacement products and as vein fillings along tectonic planes. Based on their abundance, these rocks are either talcified or carbonated serpentinite.

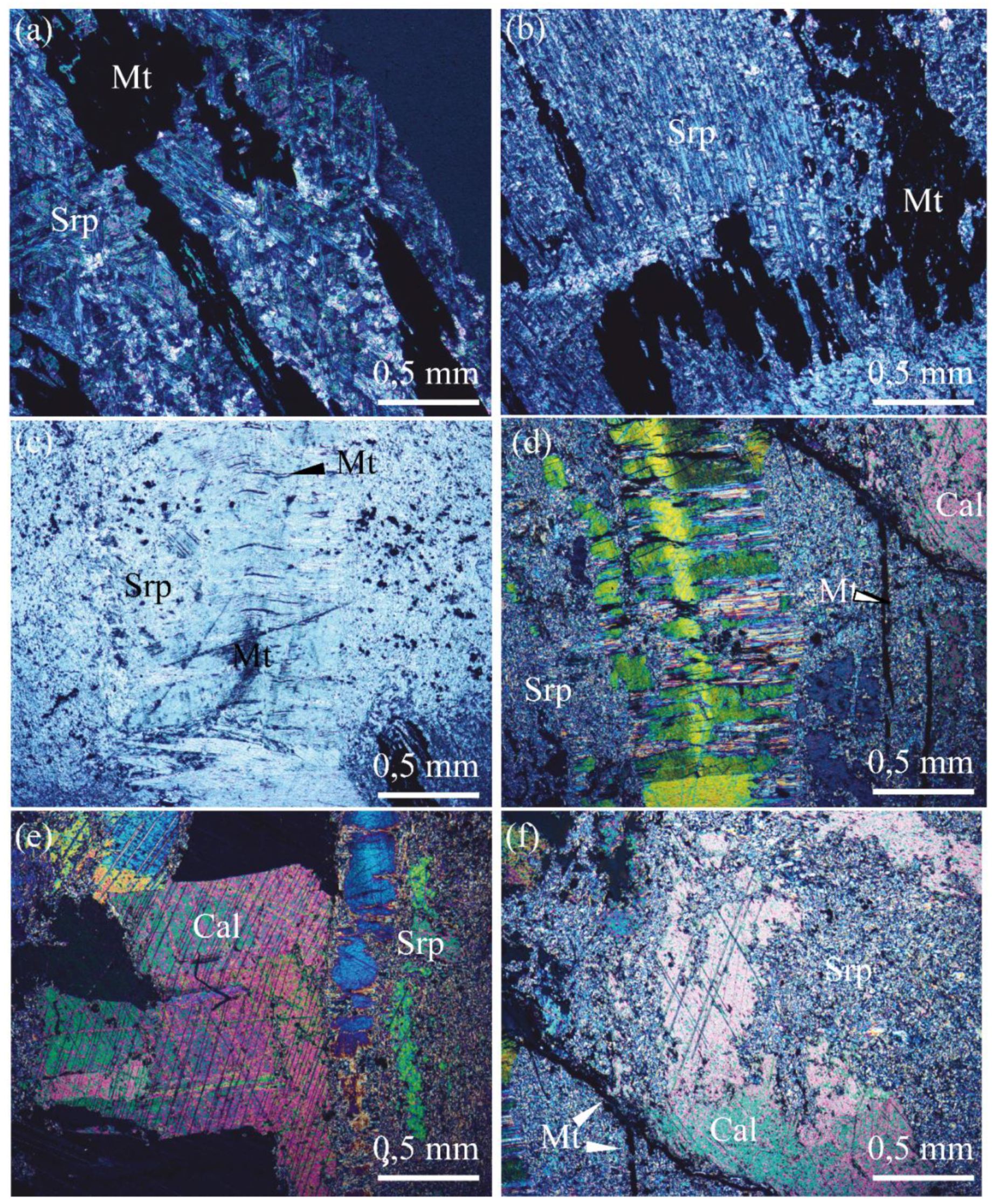

Serpentinites are dominated by mesh textures (

Figure 5a), that gradually develop into interpenetrating (

Figure 5b), lens-shaped mesh cells in deformed dunite serpentinites (

Figure 5a). In highly deformed and sheared serpentinites, the mesh textures are crosscut by fibrous clinochrysotile veinlets (

Figure 5c-f).

Magnetite outlines mesh cells from olivine ghost crystals and underlines bastite cleavage in massive serpentinite and underlines tectonic cleavage in sheared serpentinite (

Figure 5a-f). It developed micrometric to decimetric veins. Later carbonate veins are very common and evolved in pockets.

4.1.2. XRD Characterization

The Bou Azzer serpentinites X-ray diffraction analysis (

Table 1) reveals antigorite as the dominant serpentine phase, along with chrysotile and minor amounts of lizardite. Small amounts of lizardite indicate it was partly converted to antigorite upon serpentinization. Accessory minerals such as magnetite and magnesioferrite imply the oxidation of the Cr–Fe spinels upon hydration. Local occurrences of talc (2M polytype) support evidence of talcification within shear zones. Presence of carbonate phases (calcite and dolomite) at contacts and along microfractures suggests late-stage carbonate formation by infiltration of fluids.

The bulk XRD assemblage reflects a multiphase serpentinization history, with early lizardite-rich textures overprinted by antigorite and clinochrysotile under higher-temperature conditions, followed by late-stage talc and carbonate generation during post-obduction hydrothermal alteration.

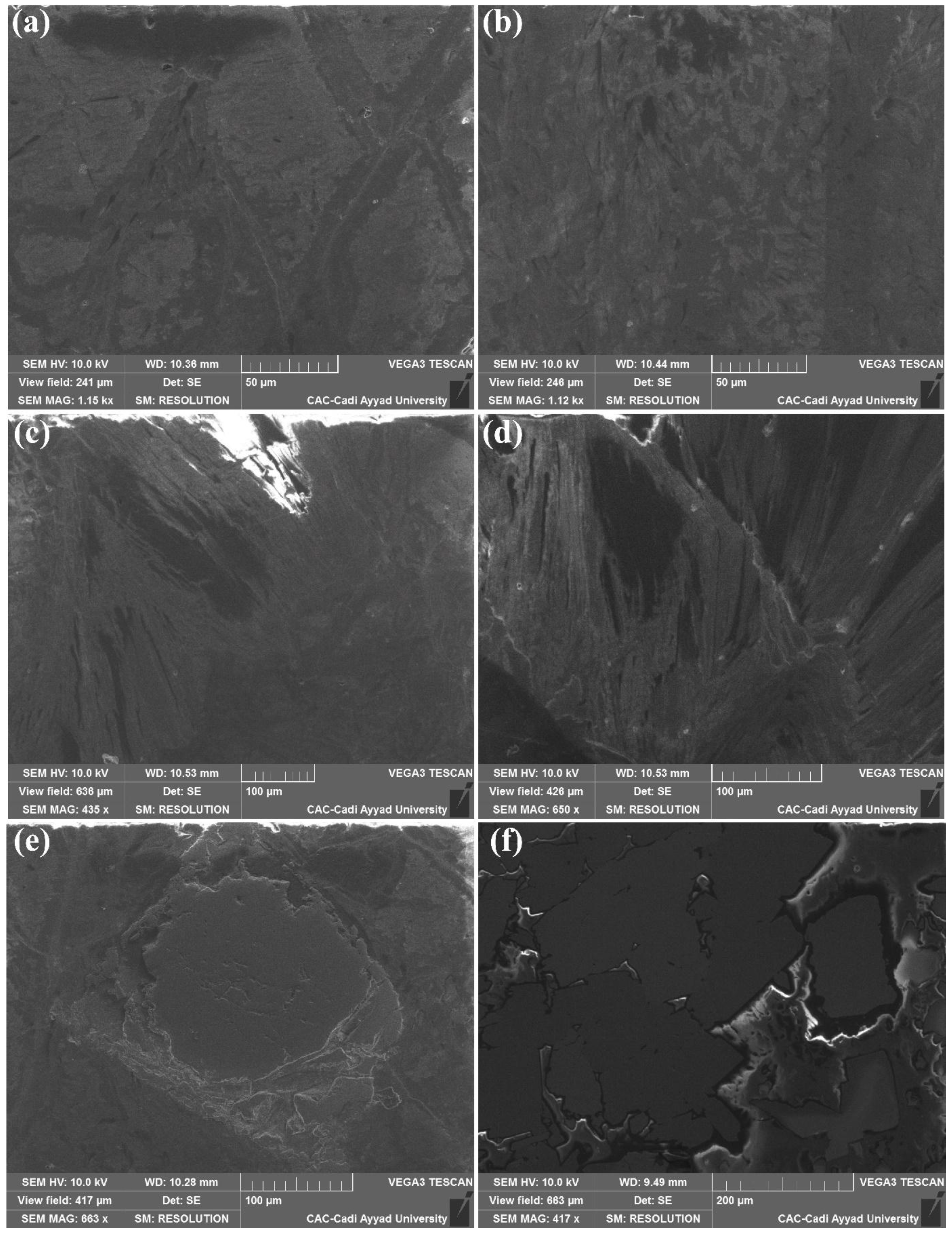

4.1.3. XRD SEM

SEM images of Bou Azzer serpentinites (

Figure 6) reveal successive textures and replacement relationships. Lizardite crystals are predominantly prismatic, whereas some globular crystals likely reflect high-grade metamorphic transformation, consistent with previous studies [

24,

57]. Fibrous particles observed along microfractures and veinlets are attributed to chrysotile (Wafik et al., submitted). Chrysotile invariably overprints earlier serpentine microstructures such as mesh textures and bastite pseudomorphs after olivine, indicating it is the youngest serpentine polymorph in the Bou Azzer ophiolitic sequence. These textures suggest chrysotile formation was strongly influenced by late-stage, fluid-assisted recrystallization.

4.1.4. Interpretation

The integration of field data, drill core observations, and petrographic analyses highlights a complex serpentinization history, marked by variable deformation intensity and localized carbonate alteration. These processes are spatially associated with major tectonic discontinuities within the ophiolitic sequence.

The paragenetic sequence—lizardite

→ antigorite

→ chrysotile—records progressive serpentinization under evolving pressure–temperature conditions during ophiolite evolution. Chrysotile formation is a late-stage, syn- to post-obduction event, facilitated by intense fracturing associated with Bou Azzer ophiolite emplacement. This reflects localized fluid infiltration along brittle structures, producing characteristic fibrous textures. These observations align with previous studies of chrysotile in ultramafic complexes [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] and highlight the key role of deformation-controlled fluid pathways during the final stages of Bou Azzer serpentinization [

8].

Optical Microscopic (

Figure 5) and SEM (

Figure 6) observation coupled with XRD data show that the investigated ultramafic rocks underwent a variable degree of serpentinization and carbonation (

Table 1). All of the rocks analyzed are completely serpentinized and mostly formed of antigorite and chrysotile, with minor quantities of lizardite, magnetite, chromian spinel, carbonates, and talc (

Table 1). The original cumulus textures are sometimes partially or totally preserved in the Bou Azzer serpentinites. Cumulus minerals have been replaced by serpentine minerals, with a gradual evolution from undistorted mesh and bastite pseudomorphic textures to foliated, ribbon-like lizardite textures characterized by clear crystallographic and shape-favored orientations. Serpentinite veins are common within fractures and shearing planes in most serpentinite facies (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

4.2. Geochemistry

4.2.1. Major Elements

The results of the contents of major and trace elements (

Table 2), recalculations of normative mineralogy (CIPW) of the serpentinized peridotites, and the classification of the samples (

Table 3), the value of the major elements recalculated in the absence of water to reduce the effects of dilution of the resulting variable elements of the serpentinization process are discussed below.

The analytic results display the high value of LOI (10.83-14.99 wt.%). This value is very well explained by the petrographic study, which displays a very altered serpentinite hydrothermal type. However, all samples are characterized by a lower concentration of SiO2 (30,19 -54,04 wt.%) and high values of MgO (24,21-42,32 wt.%). The ratio MgO/SiO2 ranges from 0,32 to 1,04, and Mg/(Mg + Fe) ranges from 0,81 to 0,85. the other oxides (Al2O3, Fe2O3, and MnO) show a lower concentration range, respectively from (0.26-1.5 wt.%, 4.46-9.19 wt.%, and 0.08-0.37 wt.%). CaO values are comprised between 0.02 to 11.78 wt.%. This high value is detected within carbonated facies, and contents are less than 0.01 wt.% for preserved serpentinite. TiO2 values are ≤ 0.02 for serpentinite to 0.70 wt.% for carbonates bearing serpentinites. Na2O ≤ 0.5 wt.% and K2O ≤ 0.02 wt.%) are very low are comparable to those from modern oceanic peridotites [

63].

Al/Mg ratio range between (0.01-0.82), Si/Mg ratio (0.2-1.2), and Ca/Al ranges from (0-0.96) for preserved serpentinite and is higher than for carbonate-bearing serpentinites. Therefore, the Fe/Al ratio ranges between (7.28-21), the Si/Al ratio ranges from 3.91 for carbonate-bearing serpentinite to 87.8, and Fe/Mg from (0.17-0.28).

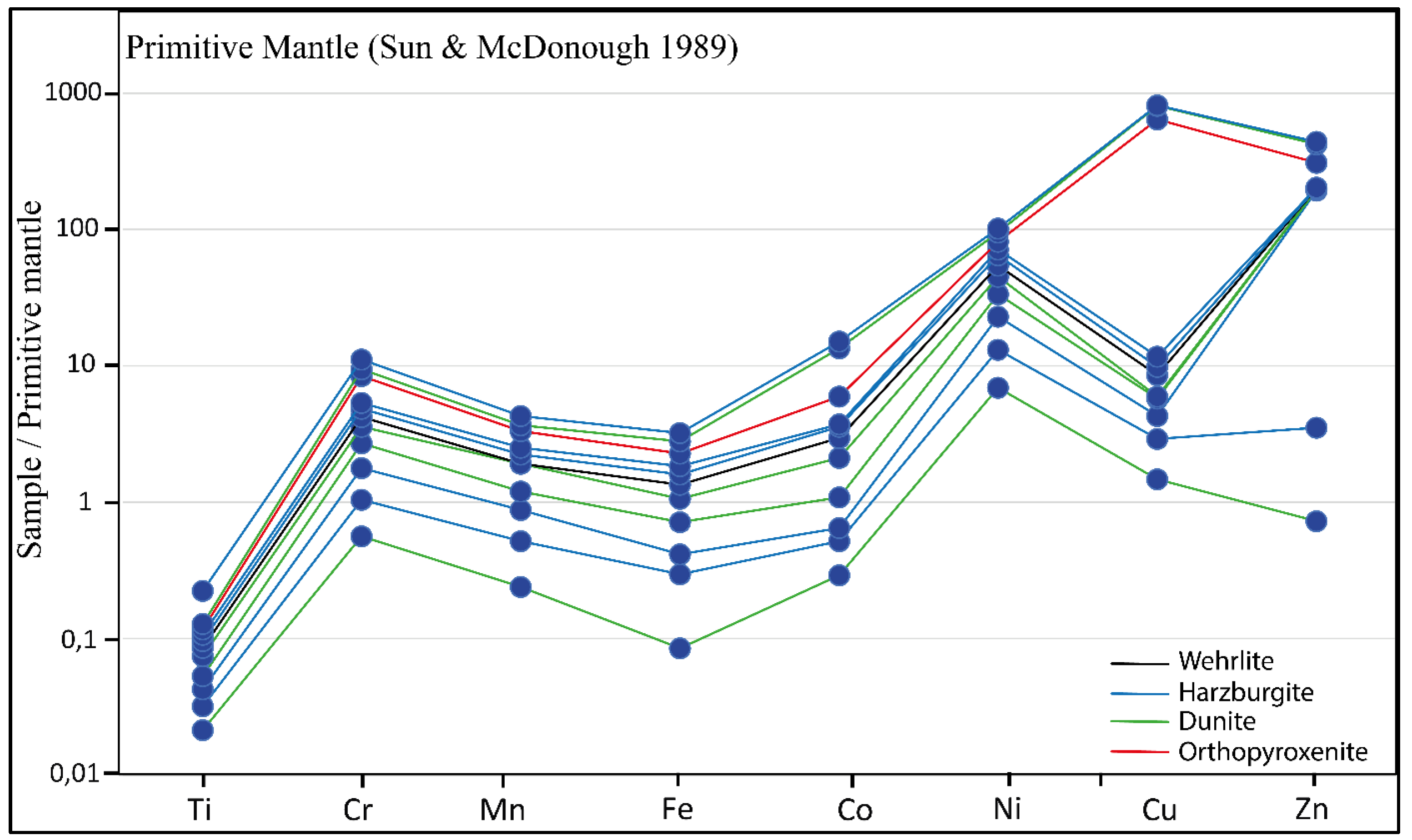

4.2.2. Traces Elements

Serpentinites, which are formed through the process of hydration of ultramafic rocks, serve a pivotal role as archives of processes occurring within the mantle, in addition to fluid-mediated geochemical cycling. The multi-element spider diagrams, normalized to the primitive mantle [

64], for the Bou Azzer serpentinite suite reveal distinctive geochemical signatures, reflecting varying degrees of melt depletion, serpentinization, and fluid-rock interaction [

64]. The selected elements (Ba, Sr, Nb, Zr, Y, Ti, V, Cr, Ni, Co) represent a range of geochemical comportments, from fluid-mobile large-ion lithophile elements (LILE) to high-field-strength elements (HFSE) and transition metals, thus offering insights into protolith characteristics and alteration histories that reflect a complex interplay of mantle source depletion, melt extraction, and late-stage fluid modification (see

Figure 7 and

Table 4).

The concentrations of critical elements, such as chromium and nickel, were found to be remarkably elevated. Chromium levels in some samples reached values up to several thousand parts per million (ppm), while nickel levels in a sample designated as BA1 attained concentrations as high as approximately ninety thousand ppm. Chromium content is consistently greater than 500 ppm (except for one DO23 sample with 145 ppm), reflecting a strongly refractory protolith. Nickel concentrations remain high (typically 800–2,000 ppm), which is consistent with depleted spinel lherzolite or harzburgite sources [

65,

66]. Furthermore, elevated Cr–Ni contents are conducive to derivation from depleted mantle peridotite, as opposed to crustal sources. These are characteristic of ultramafic rocks and serpentinized peridotites, which are indicative of their mantle origin [

67].

Cobalt (Co):

The concentrations of these elements range from moderate to high (tens to hundreds ppm). Co is generally compatible and covaries with Ni and Cr in mantle peridotites. This variation is indicative of varying degrees of partial melting and/or metasomatic overprints.

Copper (Cu) and Zinc (Zn):

Cu shows strong enrichment in some samples (e.g., BA3, J05), possibly due to hydrothermal alteration and fluid circulation along serpentinization zones. Zn is variable but, overall, high relative to the primitive mantle. However, copper concentrations are highly variable (8 to >1000 ppm), indicating localised sulphide mobilisation and redistribution, likely during serpentinisation and late hydrothermal overprinting [

17,

68]. Samples with exceptionally high copper (>1000 ppm) occur preferentially in some localities, potentially reflecting sulphide accumulation associated with fluid percolation along major shear zones.

Immobile HFSE (Nb, Zr, Ti, Y):

High-field-strength elements (HFSEs), such as Ti and Zr, remain relatively low, consistent with depleted mantle sources. Titanium is consistently depleted across the dataset, a feature typical of residues after partial melting [

54,

69]. Some samples show moderate enrichment in vanadium, which potentially records variations in oxygen fugacity conditions during hydration and obduction-related tectonism [

70,

71]. Bou Azzer serpentinite Sc values (6.9-34.6 ppm). Sc is very low in many samples (<20 ppm). Such low Sc contents indicate that these rocks are pyroxene-poor harzburgites/dunites rather than lherzolites. This supports a highly depleted mantle origin, since extensive partial melting removes clinopyroxene (and thus Sc) [

72].

The Sc–V–Ti systematics place most samples within the harzburgite-lherzolite compositional field on MgO–Fe₂O₃–Al₂O₃ ternary diagrams, which supports their classification as residual mantle rocks.

Nb is found in extremely low concentrations or is below the level of detection in the majority of samples, which is a characteristic feature of a depleted mantle. The presence of titanium (Ti) is minimal (i.e., less than 15 – 5800 ppm), thereby confirming harzburgite/dunite affinity. Zr and Y generally exhibit low concentrations, which is consistent with a depleted mantle protolith.

LILE (Large-Ion Lithophile Elements – Sr, Ba, Pb):

Lithophile trace elements (Ba, Sr, Pb) manifest notable enrichment for several samples in comparison to the primitive mantle. Sr and Ba are locally enriched (J05, BA3), which is indicative of fluid metasomatism during serpentinization or subduction-related fluid fluxes. Furthermore, the presence of lead (Pb) in a limited number of samples is indicative of an additional indicator of hydrothermal overprint. Alternatively, they are considered to be the imprint of crustal contamination [

21,

55,

73]. Similarly, elevated Ba is indicative of fluid circulations. Both elevated Pb and Ba are likely related to subduction-derived or syn-obduction fluids and indicative of metasomatic inputs. Elevated Pb is especially assumed as fluid circulation [

21,

55,

73].

As, Sb, Mo, W anomalies:

The concentrations of As, Sb, and Mo exhibited elevated levels of As (detected in concentrations ranging from hundreds to >100 ppm in sample BA1) in select samples. These enrichments are not typically observed in pure mantle rocks; they suggest late hydrothermal input and ore-related processes (possibly linked to the Bou Azzer ophiolite's known Co–Ni–As mineralization).

Notably, Ga shows a wide range (1.1–13.6 ppm), with the highest values linked to podiform chromitite-bearing serpentinites, which is in line with Ga being partitioned into spinel during chromite crystallization, reflecting development from a depleted mantle peridotite source. This observation further supports a supra-subduction zone origin for the Bou Azzer mantle section. Furthermore, there is a slight enrichment in Ga only in some samples (especially those associated with chromitite), supporting heterogeneity in the mantle source.

Overall, the patterns of immobile elements support the interpretation that Bou Azzer serpentinites were initially a melt-depleted mantle section (Cr- and Ni-rich harzburgite), subsequently re-fertilized by melts or fluid influx similar to those found in mid-ocean ridges (MORB), and finally overprinted by late serpentinization, which mobilized chalcophile and incompatible trace elements. This interaction took place during obduction and emplacement in the Pan-African orogeny.

5. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5.1. Ptero-Geochemical Characteristics

The serpentinites of Bou Azzer have relatively higher loss of ignition (LOI) values (12,85 – 14,4 wt.%) (

Table 2). The serpentinization processes may have raised the LOI contents without affecting the primary element composition significantly. [

17]. Numerous geochemical studies demonstrated restricted mobility of major elements during serpentinization, and protolith primary signatures were retained [

17,

62,

74,

75]. Apart from hydration, serpentinization appears to have little effect on main element concentrations. The most important chemical variations between the samples are due to the primary heterogeneity of the peridotites, even if mobilization during serpentinization can also occur [

76]. So, we suggest that the protolith major element compositions must have been preserved during the hydration processes and that the geochemistry of the studied serpentinites displays mostly the original nature.

Ca-metasomatism is quite common in the Bou Azzer serpentinites; however, the very low CaO content (0.00-0.98 wt%) in the serpentinites indicates a limited effect of carbonate metasomatism. Two groups of serpentinites can be distinguished in Bou Azzer, based on CaO contents: group (0.00-0.98 wt%) < primitive mantle contents CaO, and group 2 (1.73- 3.77) wt.% ≤ primitive mantle contents. Except for some areas near the Co-Ni-As ore deposits, where two samples with 8.11and 22.06 wt.%. This suggests that the protolith's major element compositions must have been conserved through the hydration processes, and that the geochemistry of the examined serpentinites mostly reflects the protolith's original nature. The presence of clinopyroxene correlates with a greater CaO content in serpentinites. The MgO/Si02 ratio of 0.81-1.12 compares with a mean of 1,02 quoted by Coleman (1977), who suggests that if serpentinization does not involve brucite formation, it will be a process of Mg loss and/or Si02 gain. XRD study of Bou Azzer serpentinites did not reveal the presence of brucite, suggesting that the extreme serpentinization may have involved minor chemical adjustment.

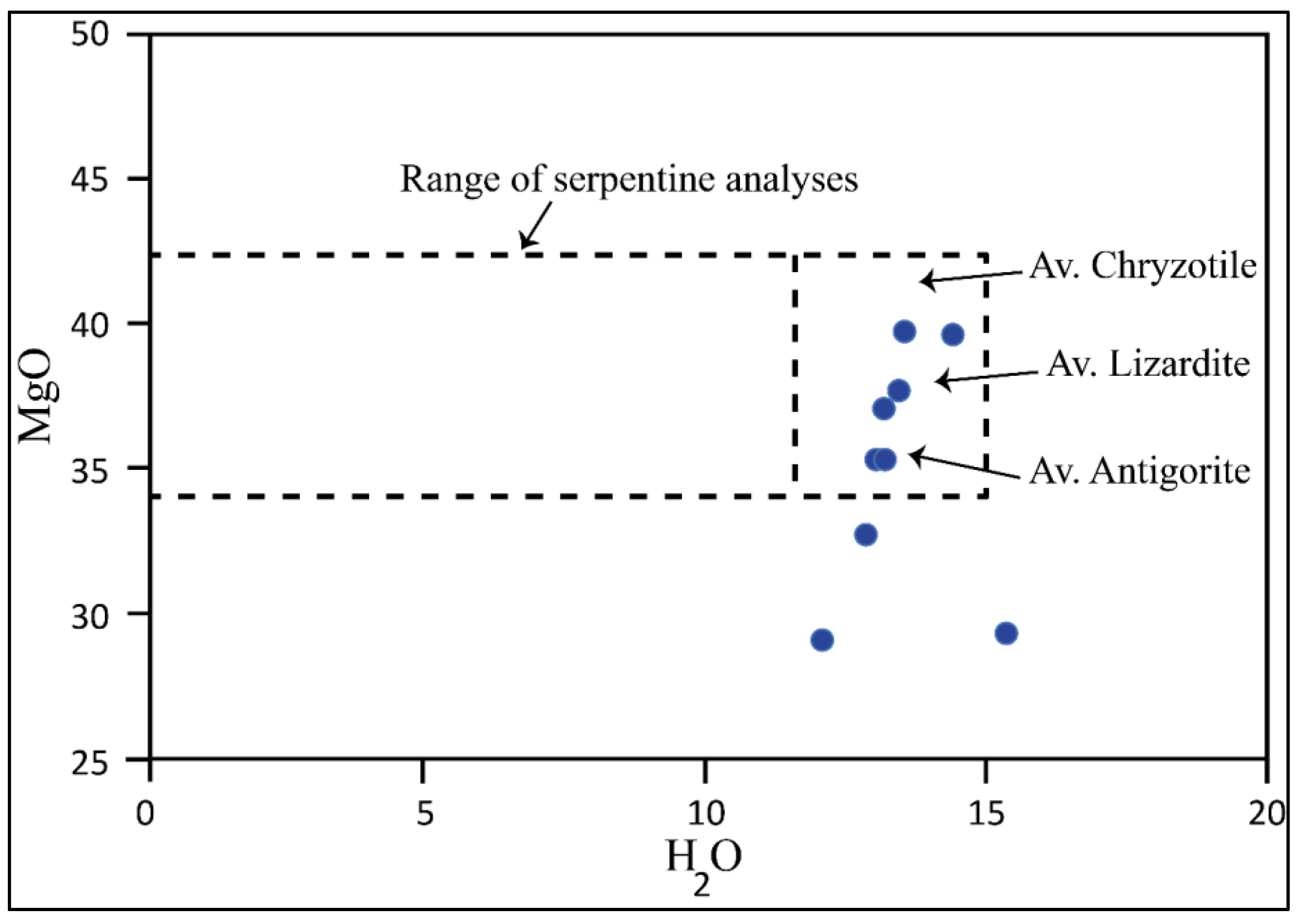

The MgO content in Bou Azzer serpentinites (MgO= 29,46 – 42,32 wt.% %) is less affected by serpentinization and indicates a highly depleted mantle source [

52,

78,

79]. Page (1966) proposed a binary diagram based on the relationship between MgO and H2O for ultramafic rocks (

Figure 8). It is used to give the mineralogy of serpentinites. It is evident from the diagram that the serpentinites studied at Bou Azzer are dominated by antigorite, with the subordinate presence of lizardite and chrysotile. The presence of antigorite over lizardite and chrysotile indicates that the analyzed serpentinites underwent prograde metamorphism.

After Bonatti & Michael (1989) [

63], the bulk-rock Al

2O

3 content is relatively unaffected by serpentinization and therefore retains its original primary signature. The studied serpentinites have Al

2O

3 contents (0.05–1.02 wt.%) relative to the primary mantle. Their very low K

2O contents (0.00–0.06 wt. %) and Na

2O (0.00–0.359 wt.%) contents except for some samples with Na2O (up to 2.75) are similar to those of oceans and ophiolitic massifs depleted peridotites [

21,

52,

53,

80,

81,

82]. There is no correlation between Al

2O

3, CaO, Na

2O, K

2O contents, and LOI. The higher concentration of Na

2O in serpentinites is in correspondence with the presence of plagioclase and acmite.

The low CaO (0.00-0.98 wt%) and A1

20

3 (0.26 to 1.5 wt%) reflect the absence of plagioclase and clinopyroxene. Orthopyroxene in harzburgite contains 0.6-1.6% Al

20

3 and 1.3-1.4% CaO [

83], and whole-rock contents in excess of orthopyroxene contribution are probably accommodated in the spinel (Al

20

3) and the exsolved clinopyroxene (CaO) phases. Thus, samples, which have a slightly higher A1

2O

3 level, have a high modal spinel content, and samples that contain minor clinopyroxene have higher CaO and Na

2O.

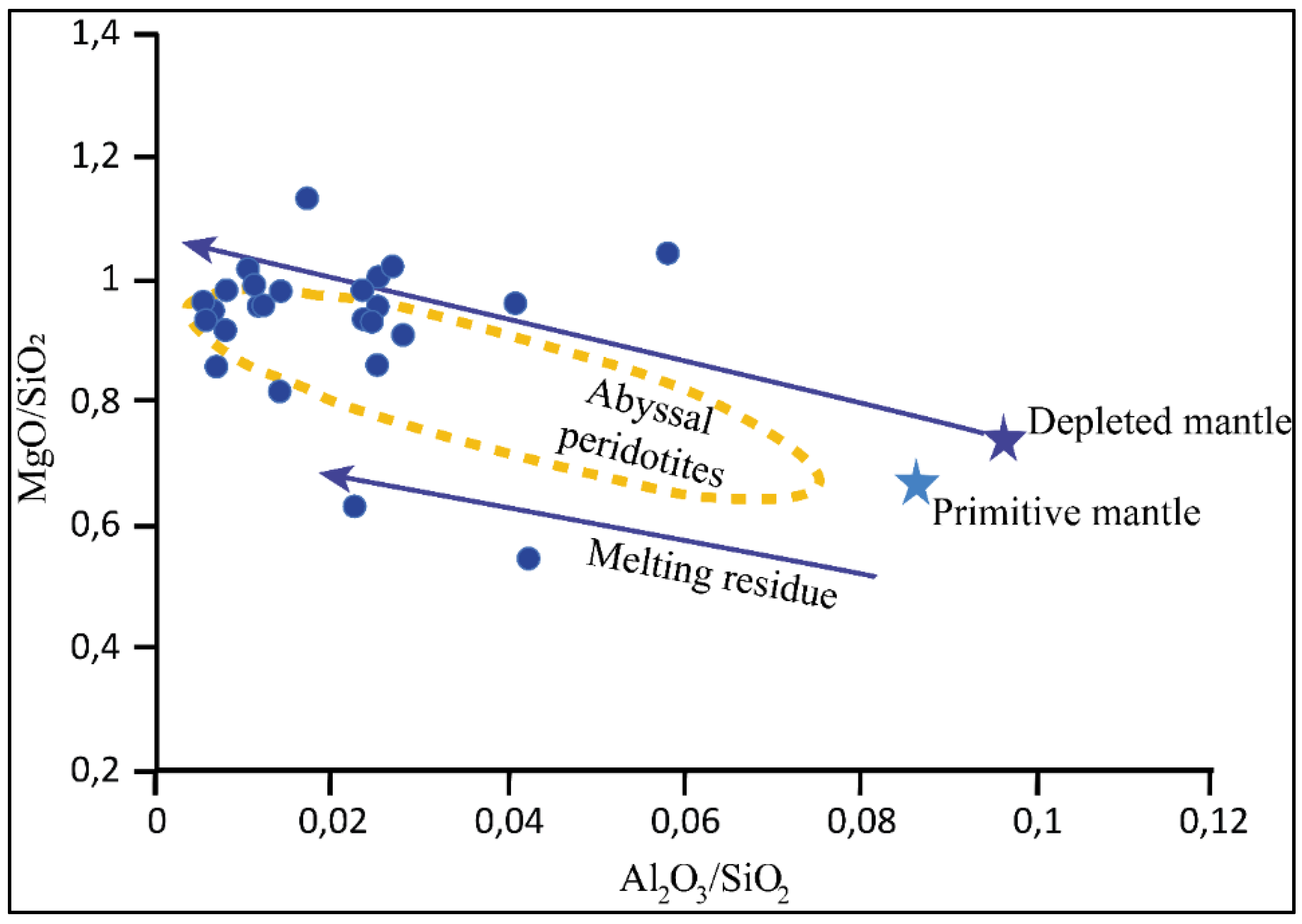

The Bou Azzer serpentinites have low CaO contents comparable to ophiolitic peridotites [

81]. Moreover, their low Al

2O

3/ SiO

2 ratios (mostly < 0.03) are similar to fore-arc mantle wedge serpentinites, suggesting that their protoliths had experienced partial melting before serpentinization, which does not affect this ratio (

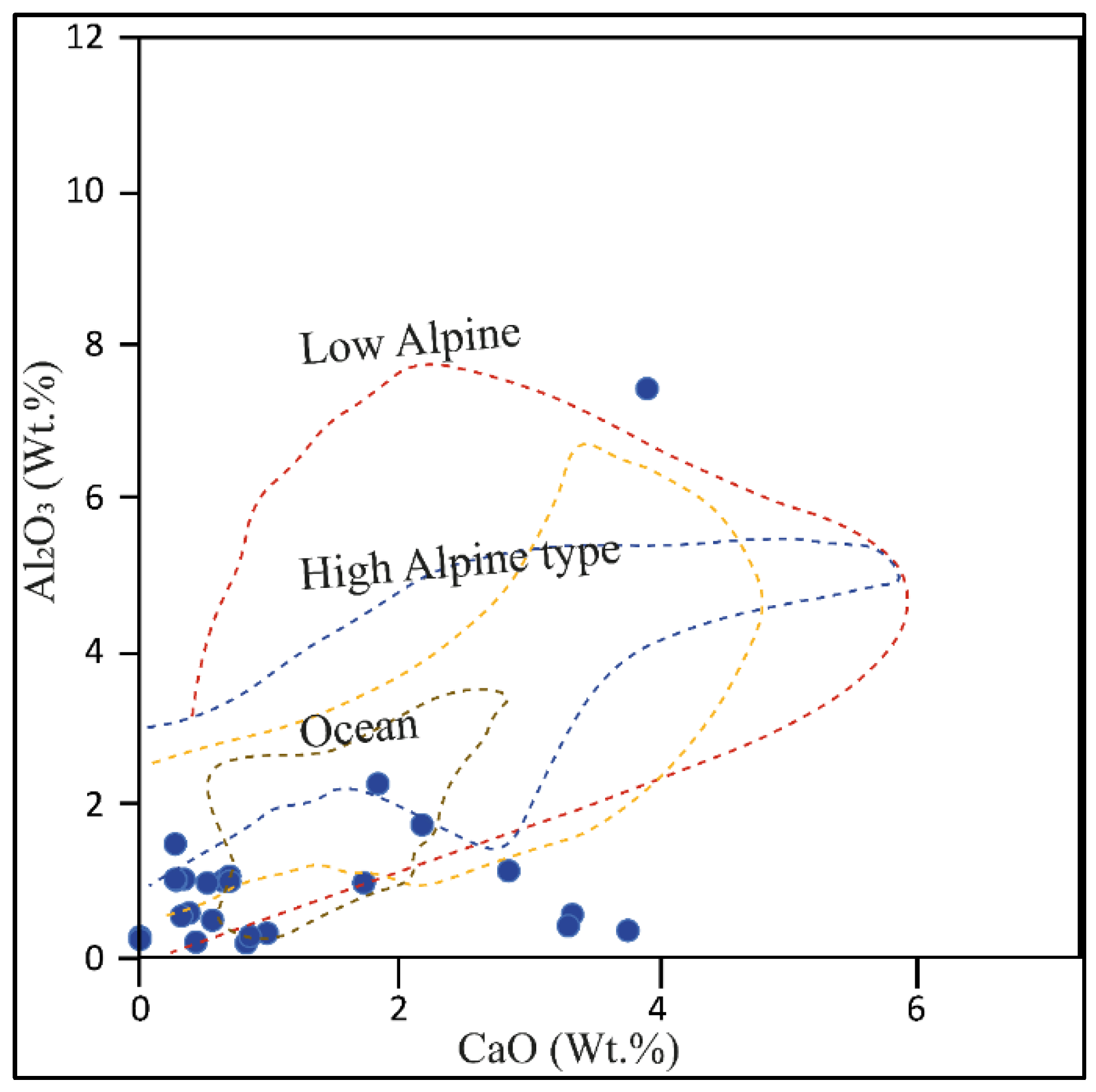

Figure 9).

Also, their low MgO/SiO

2 ratios (< 1.1) resemble serpentinised lherzolites and harzburgite [

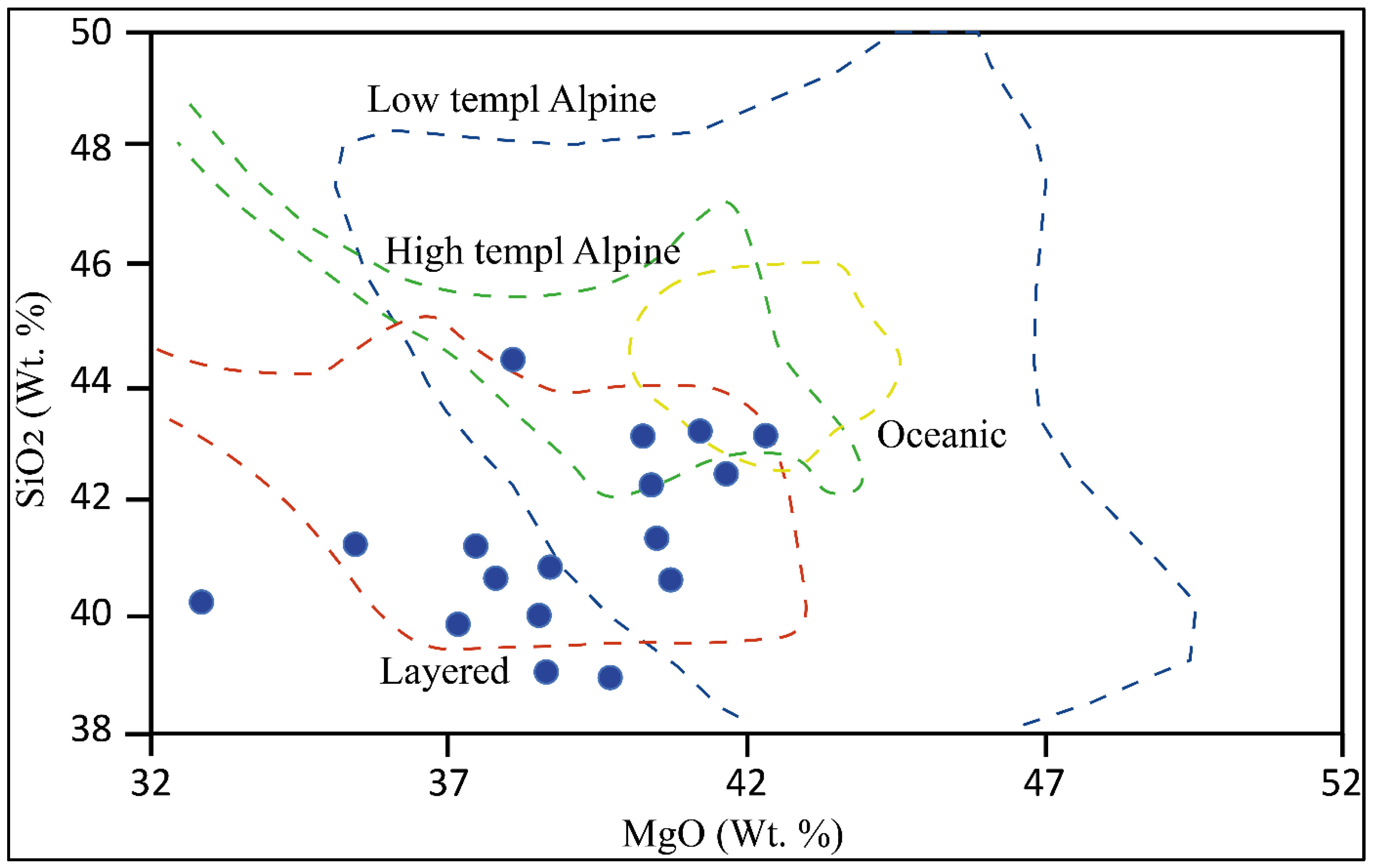

17]. It appears that the studied serpentinites fall in the low-temperature Alpine field and are close to the oceanic Mid-Atlantic Ridge field and layered complex (

Figure 10). They have low TiO

2 contents (0.01–0.06 wt.%) compared to depleted mantle composition but like subduction zone serpentinites [

17,

84].

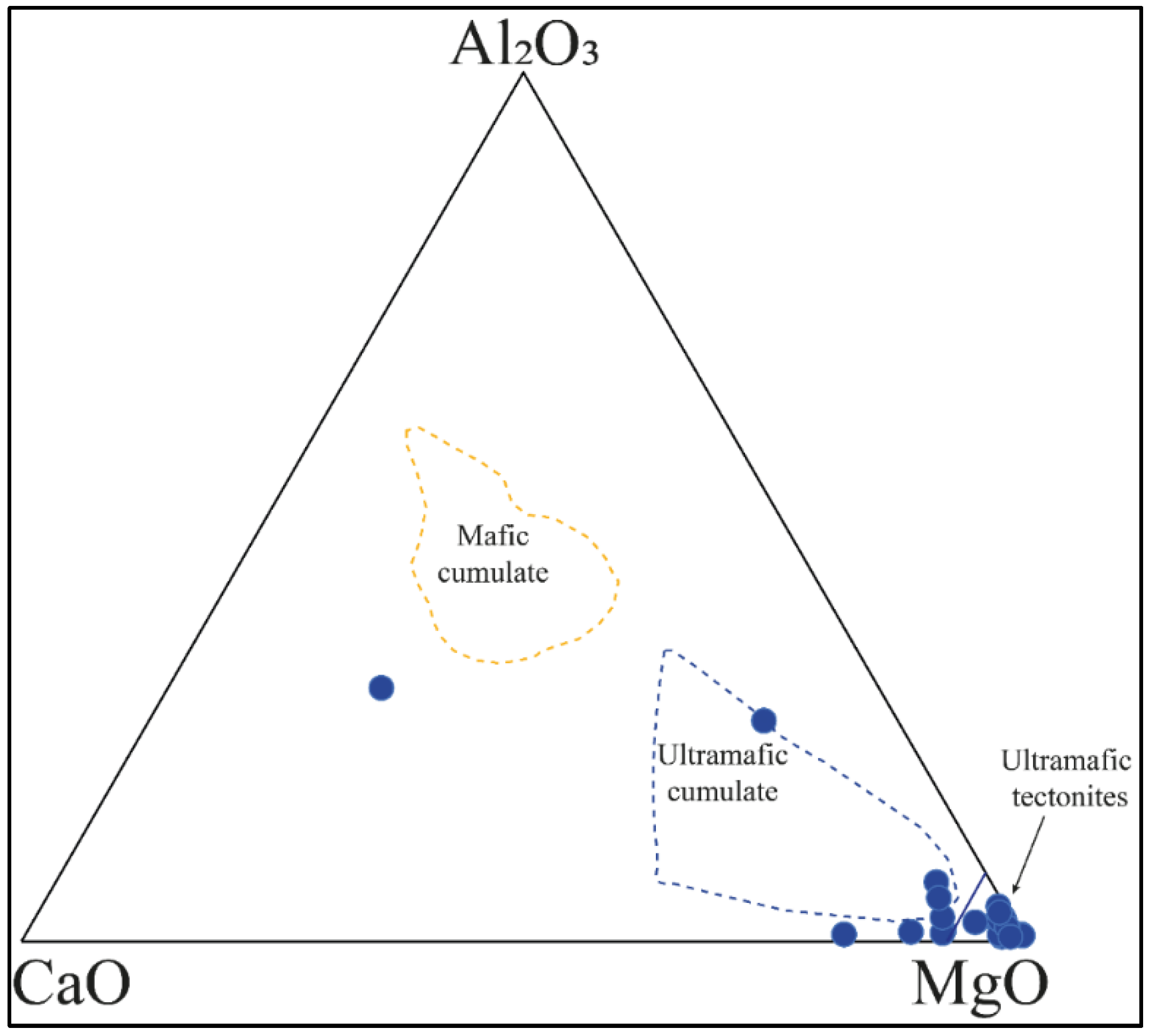

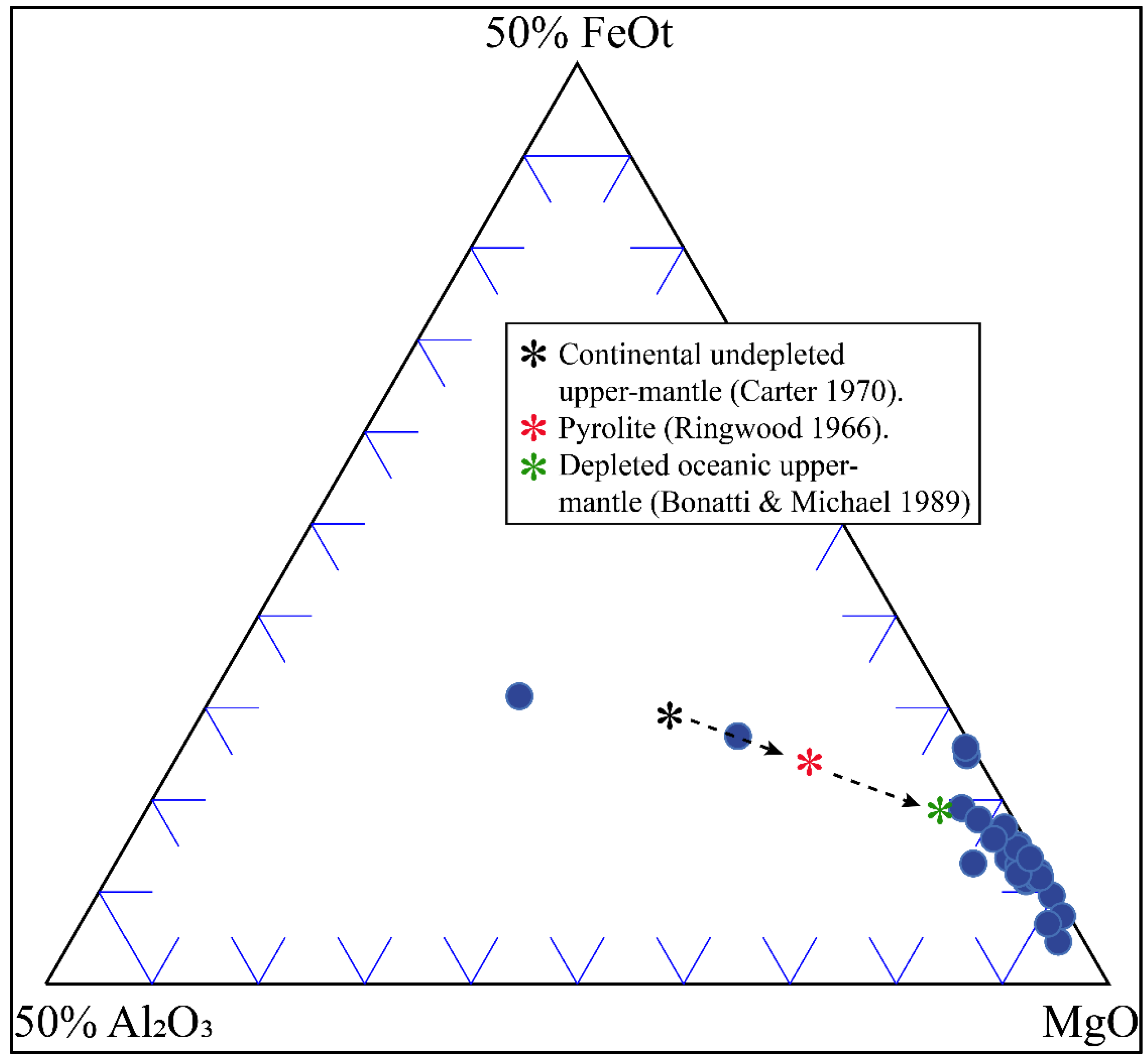

Figure 11 outlines the chemical composition of Bou Azzer serpentinites in the Al

2O

3-FeO-MgO diagram. The arrows indicate the mantle depletion sequence, with a continental undepleted mantle as the starting point. The major element compositions of the Bou Azzer serpentinites suggest they are mild refractories, corresponding to the compositional range of fertile mid-oceanic ridge peridotite [

63].

The extremely low levels of Al, Ca, K, Na, P, Ti, and the high Cr, Ni, and Mg are all suggestive of a residuum depleted by partial melt extraction. All of these data suggest that the majority of Bou Azzer serpentinites are residual mantle, subjected to variable degrees of depletion by partial melting and extraction of basaltic melt. The less-depleted mantle probably consisted of the plagioclase lherzolite seen in the ophiolites of Others, northern Greece, and other mantle sequences [

89].

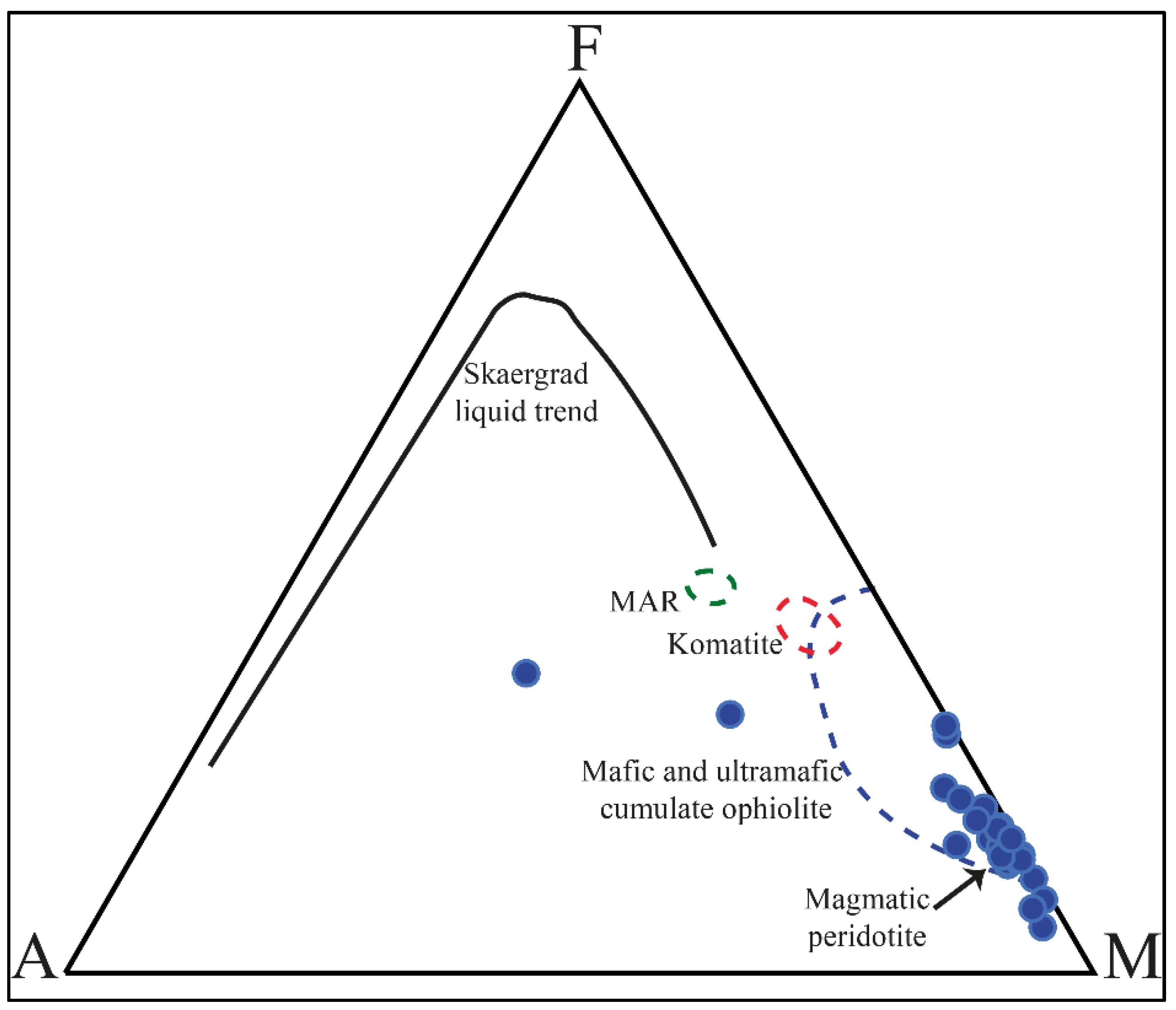

The AFM diagram was used to plot the examined Bou Azzer serpentinite samples [

77]. The analyzed samples display affinity to the typical magmatic peridotites and mafic and ultramafic cumulate ophiolite fields (

Figure 12).

Coleman (1977) proposed two discrimination diagrams based on several major oxides. Al

2O

3, CaO, and MgO, ternary discrimination diagram proposed by Coleman (1977)[

77], shows that the Bou Azzer serpentinites are characterized as ultramafic tectonites (

Figure 13). While some of the serpentinite samples appear to be in the ultramafic cumulate field, this can be explained by the effects of sub-solidus events. All the analyzed samples fall within the ultramafic cumulates and ultramafic tectonites metamorphic peridotite field, which originated in orogenic belts. Only two samples are parallel to the Skaegraad liquid.

Figure 13.

(a) Triangular diagram of MgO–CaO–Al2O3 (wt.%) for mafic and ultramafic rocks. Komatite field from various sources and MAR represents the average composition of Mid-Ocean Ridge basalts. The Skaegaard liquid trend is displayed to illustrate possible corollaries to the differentiation of a basaltic liquid in ophiolite sequences.

Figure 13.

(a) Triangular diagram of MgO–CaO–Al2O3 (wt.%) for mafic and ultramafic rocks. Komatite field from various sources and MAR represents the average composition of Mid-Ocean Ridge basalts. The Skaegaard liquid trend is displayed to illustrate possible corollaries to the differentiation of a basaltic liquid in ophiolite sequences.

Figure 13.

(b) Triangular diagram of MgO–CaO–Al2O3 (wt.%) for mafic and ultramafic rocks.

Figure 13.

(b) Triangular diagram of MgO–CaO–Al2O3 (wt.%) for mafic and ultramafic rocks.

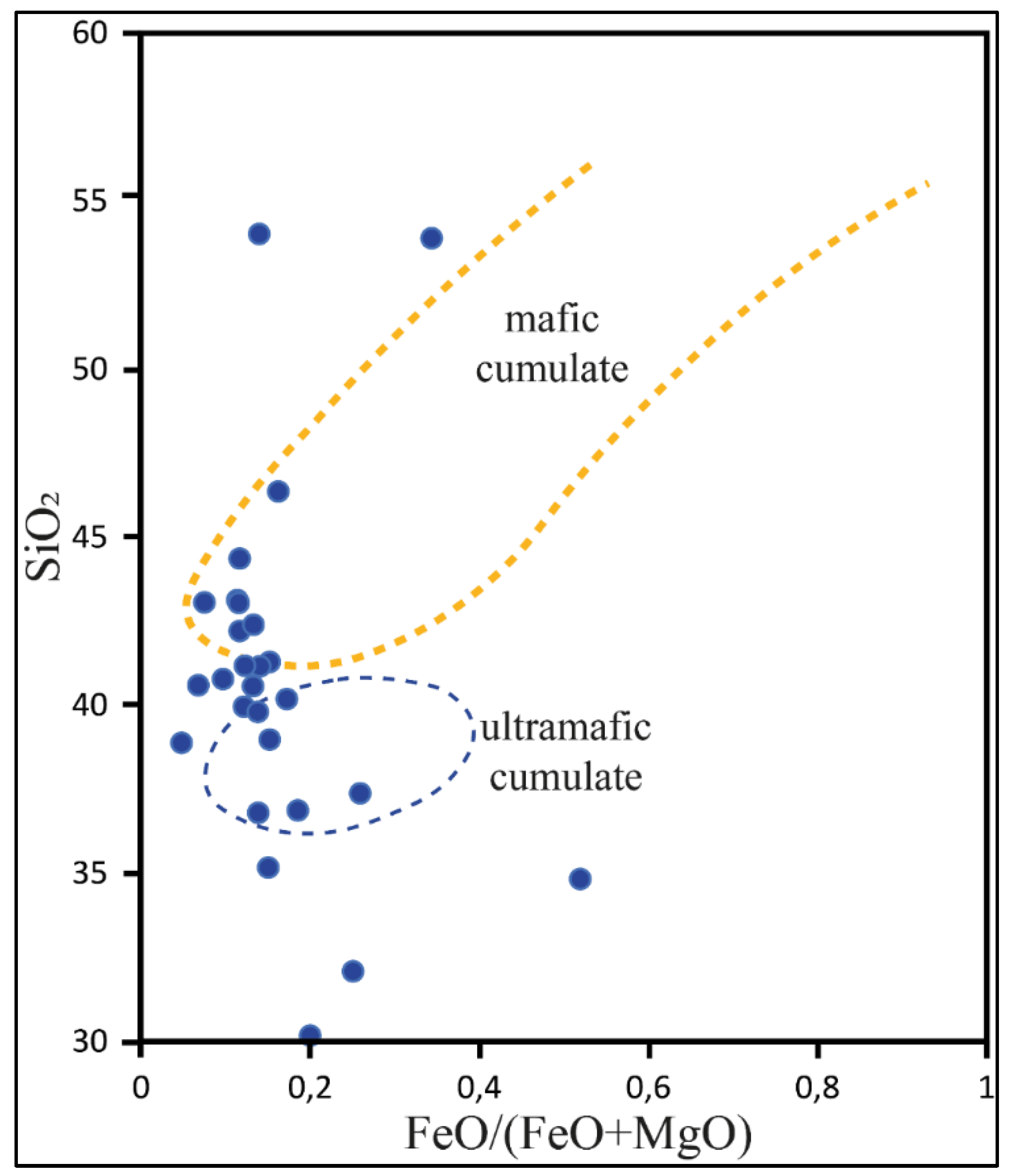

The SiO

2% versus FeOt/FeOt+ MgO ratio (

Figure 14) is used to discriminate between ultramafic and mafic cumulates. All analyzed samples of the studied serpentinites clearly plot in both the ultramafic cumulate and mafic cumulate fields, describing a trend.

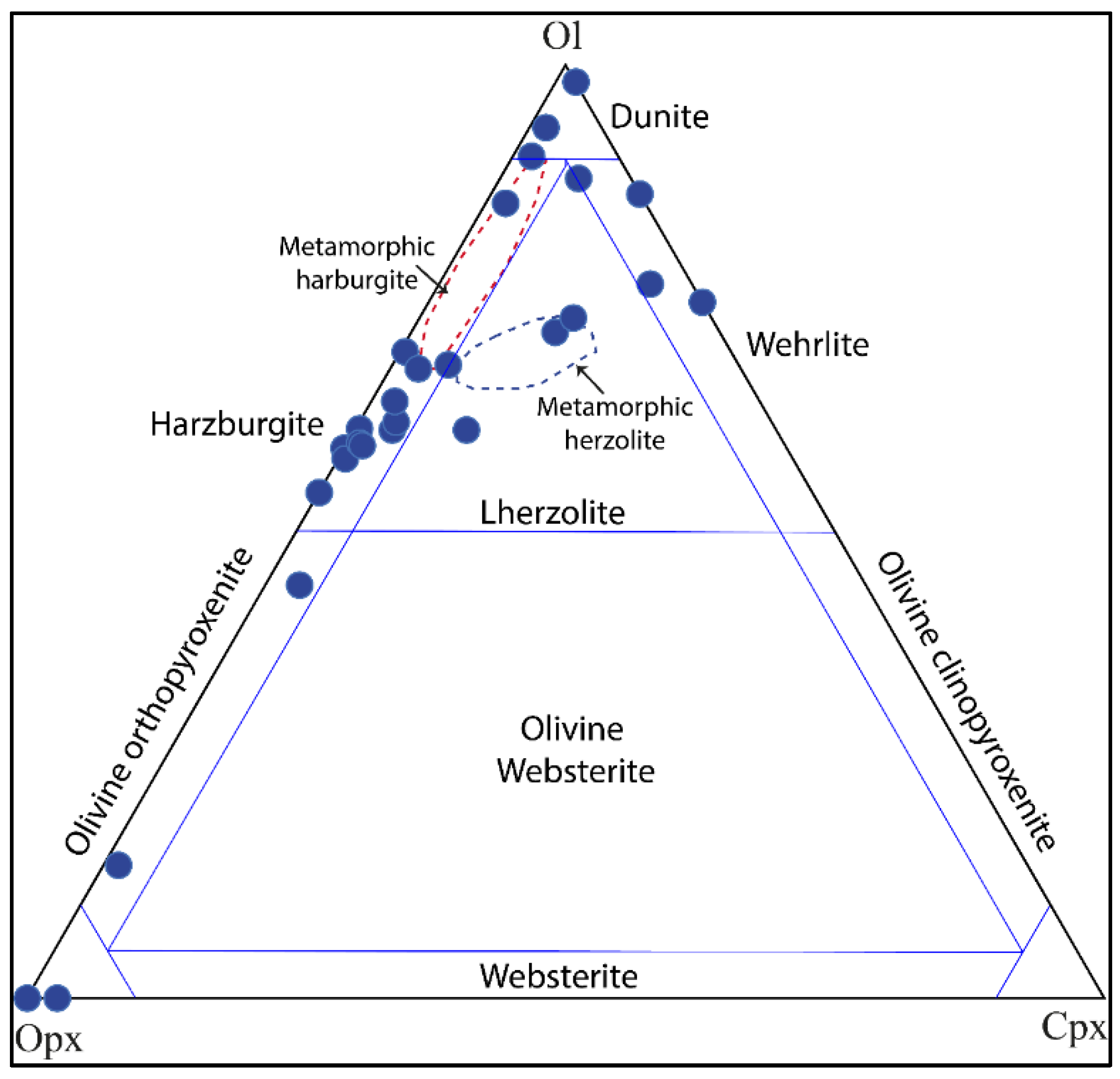

The Ol-Opx-Cpx diagram is used to plot the normative composition of the serpentinites studied [

77] (

Figure 15). They fall mainly in the harzburgite and metamorphic harzburgite field, with some samples in the wehrlite and the lherzolite field, and some others fall in the olivine orthopyroxenite and orhopyroxenite field.

The Bou Azzer ultramafic rocks corresponding to lherzolites exhibit a unique geochemical fingerprint: they are relatively fertile in major elements but highly depleted in incompatible trace elements. Such a pattern is reminiscent of mantle domains described in the southern French Massif Central [

90,

91]. This geochemical signature can be explained as the trace of low-degree partial melting of a fertile peridotitic mantle, similar to the depleted MORB-source mantle (DMM) composition [

91,

92].

A different model is the secondary enrichment of previously refractory mantle. In this case, strongly depleted harzburgitic protoliths might then have been refertilized by MORB-like silicate melts or metasomatic fluids [

93]. which injects basaltic constituents, thus endowing the peridotite with major-element enrichment but magmaphile trace-element depletion. Indeed, Lenoir et al. (2000) [

90] suggested that the LREE-depleted lherzolites from the French Massif Central formed by such refertilization. More recently, Puziewicz et al. (2020) [

94] demonstrated that lherzolites from the same area were produced by melt percolation and reaction with a depleted harzburgitic protolith.

Combined, these analogies imply that the Bou Azzer lherzolites probably capture a mantle history of melt extraction followed by partial refertilization. Such a two-stage evolution emphasizes the dynamic nature of the sub-continental lithospheric mantle below the Anti-Atlas and correlates with processes reported from other orogenic peridotite massifs.

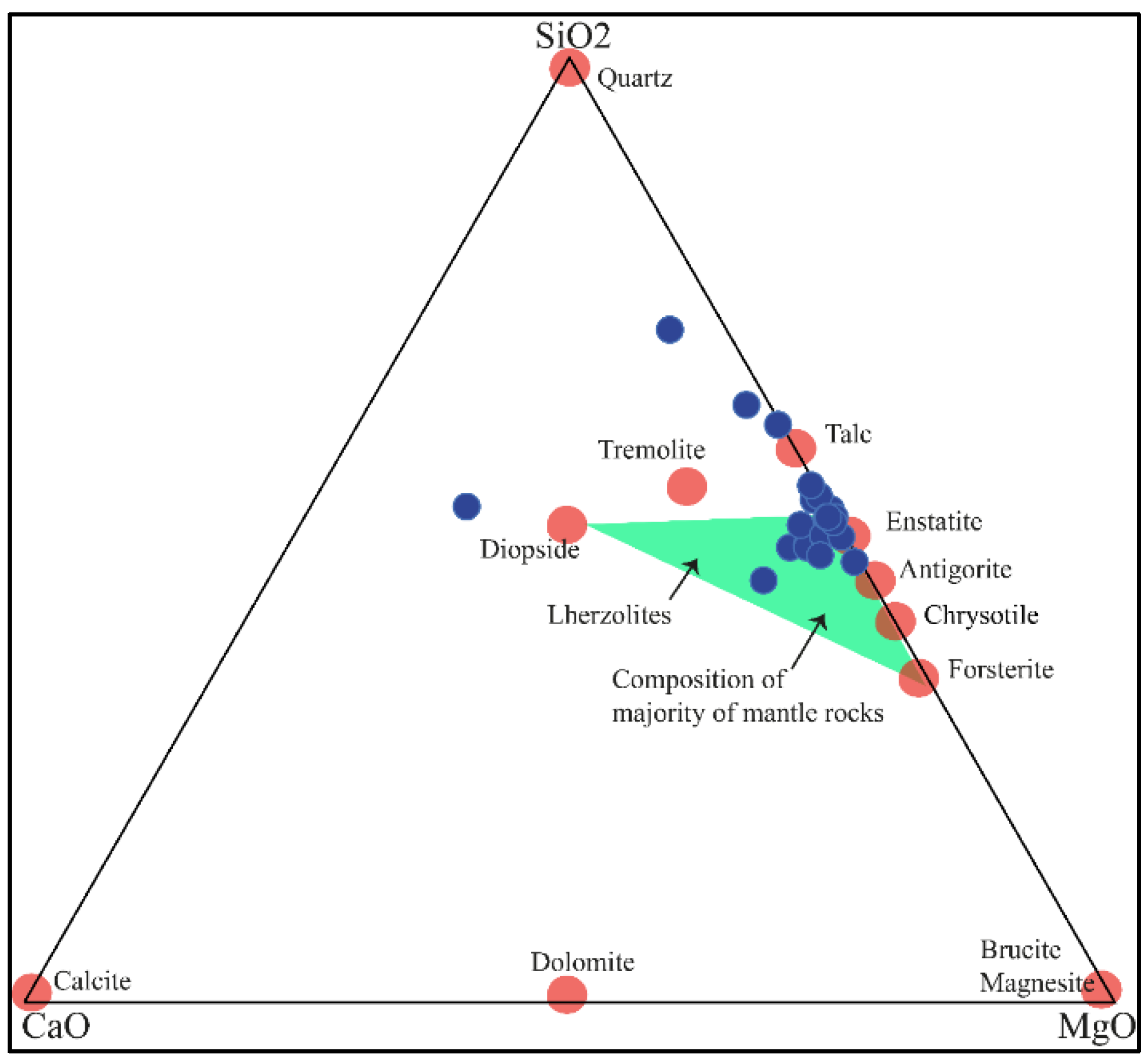

Bucher & Frey (1994) [

95] introduced a chemical graphic projection (CMS–HC system) from H2O and CO2 onto SiO

2–CaO– MgO plane (

Figure 16). The composition of the mantle rocks with anhydrous mineralogy OL +OPX + CPX is restricted to the shaded area defined by forsterite (Fo: Olivine), enstatite (En: OPX), and diopside (Di: CPX). The analyzed serpentinites falling mainly on the Fo-En join are harzburgite (depleted mantle peridotites) with some samples in Fo-En-Di; they are Wehrlite-lherzolite.

5.2. Tectonic Setting

Aumento & Loubat (1971) [

88] proposed two diagrams to discriminate between the various types of ultramafic fields, namely low-high temperature Alpine ultramafic rocks, oceanic serpentinites, and layered intrusions, based on the amounts of major oxides of SiO

2–MgO and Al

2O

3–CaO. It appears that the studied serpentinites in Bou Azzer fall in the low and high-temperature Alpine field and are close to the oceanic Mid-Atlantic ridge field, with many samples which plot within the layered intrusions field (

Figure 10 and

Figure 17).

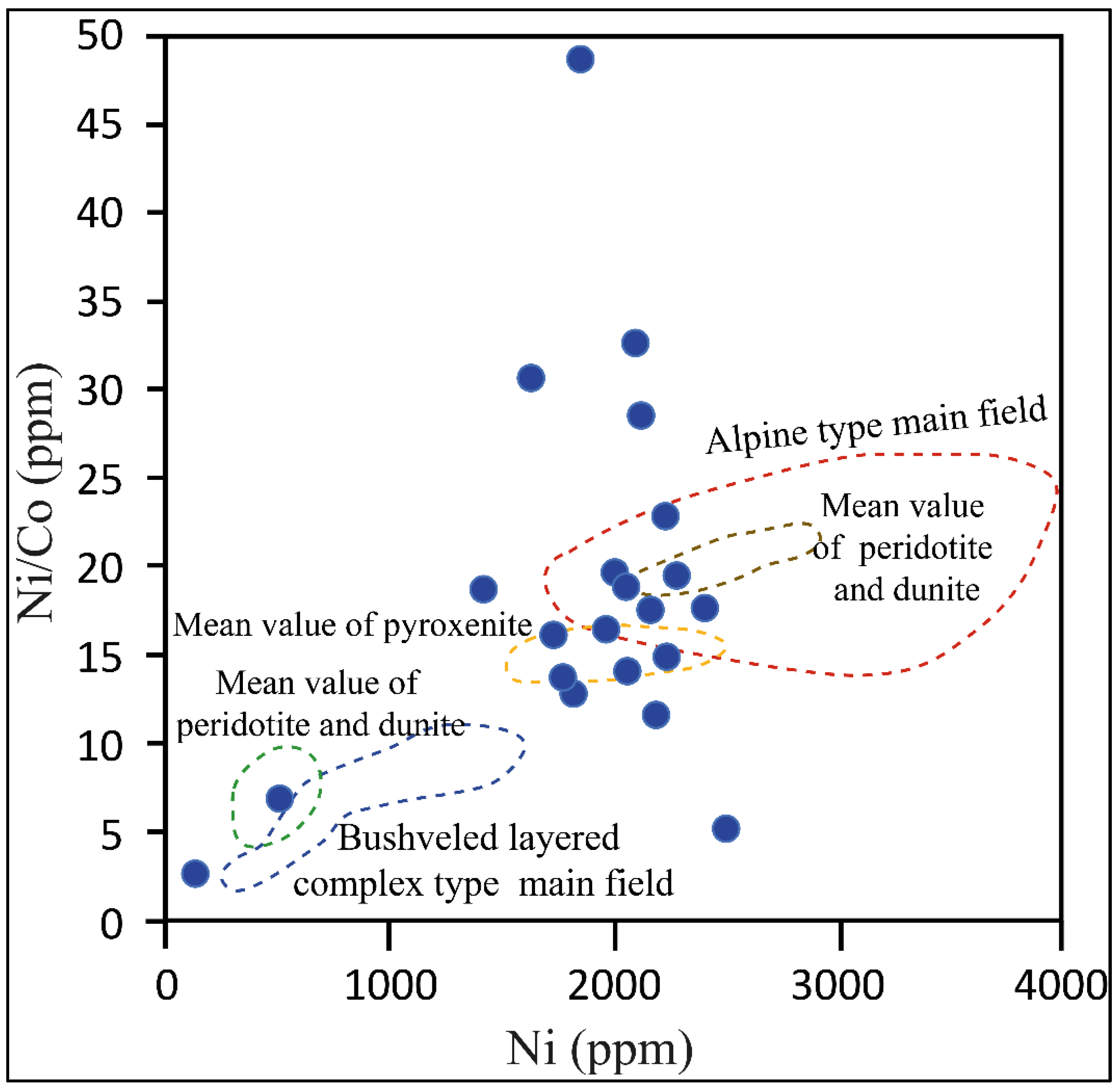

Gülaçar and Delaloye (1976) [

96] proposed plotting Ni/Co versus Ni (

Figure 18). It is clear from the figure that the majority of serpentinites have high Ni/Co ratios and plot within the Alpine type (dunite-peridotite) and layered intrusions fields. The ultramafic rocks, which are generated from the early phases of magma production by partial melting of the mantle, have a high Ni/Co ratio [

97].

The Bou Azzer ultramafic suite is characterised by the prevalence of depleted major element harzburgite and dunite with some relatively major element-fertile lherzolites, which are, however, depleted in incompatible trace elements. This geochemical fingerprint is consistent with mantle domains described in the southern French Massif Central [

90,

91]. It is commonly assumed that such lherzolites are the result of low-degree partial melting of a fertile peridotitic mantle, bearing a resemblance to the depleted MORB-source mantle (DMM) composition. In this particular context, the hypothesis is proposed that the Bou Azzer lherzolites constitute a mantle section that underwent a limited degree of melting and extraction before being redeployed within the Neoproterozoic oceanic lithosphere. Nevertheless, an alternative but no less credible explanation may be postulated involving the refertilization of harzburgitic protoliths that had previously experienced depletion. However, experimental and field evidence demonstrates that percolation of basaltic or MORB-like melts through refractory peridotites can reintroduce major-element components (in particular cpx-forming elements), producing lherzolitic assemblages whilst preserving a residual trace-element depletion [

93].

The present study supports the melt-rock interaction model proposed by Lenoir et al. (2000) and Puziewicz et al. (2020) [

90,

94], who demonstrated that the lherzolites from the French Massif Central were produced by MORB-like melt refertilization of previously depleted lithospheric mantle.

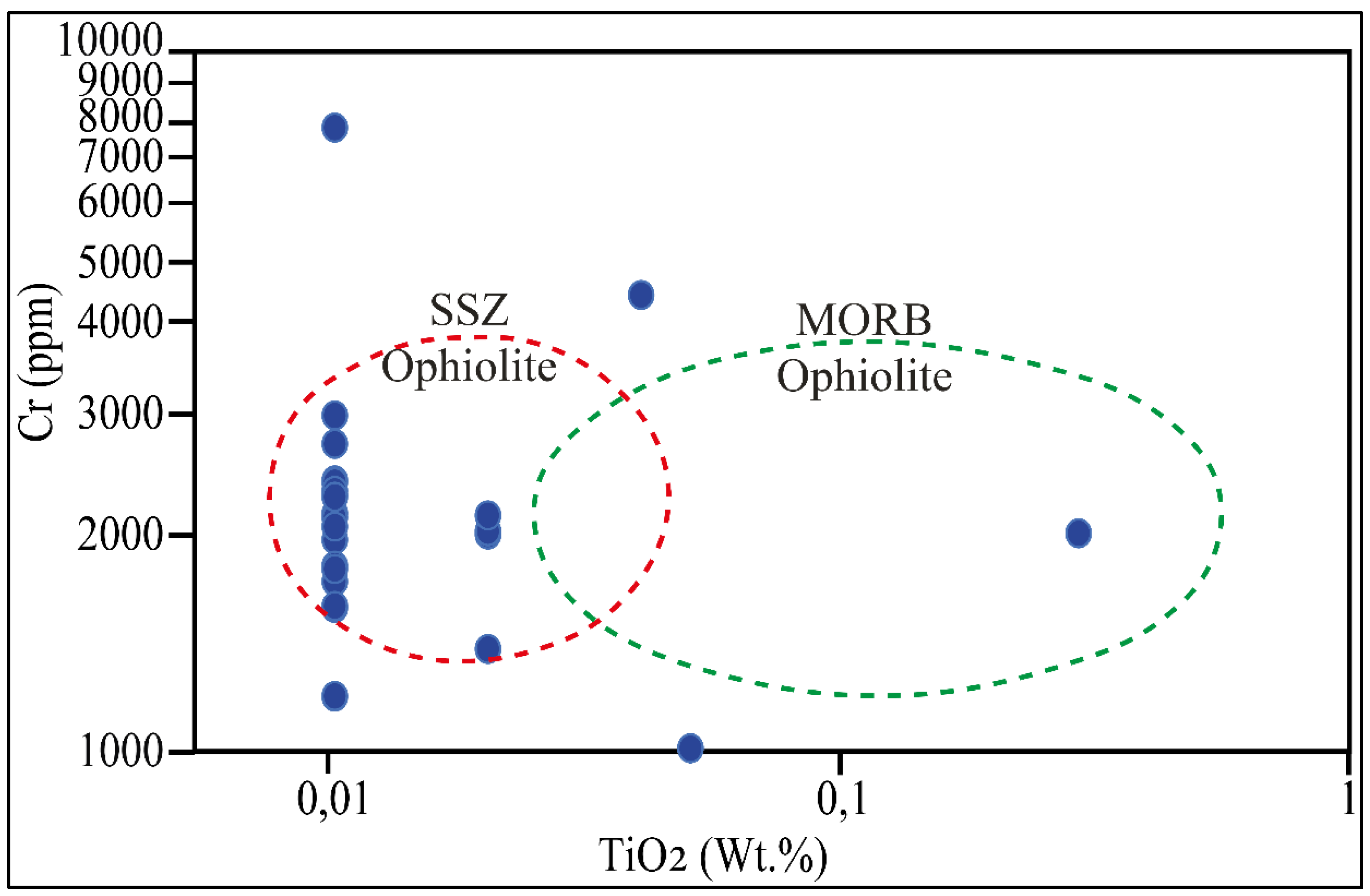

Pearce et al. (1984) [

99] proposed a graphic to distinguish supra-subduction zone ophiolites (SSZ) from Mid-Ocean Ridge basalt (MORB) ophiolites based on Cr vs TiO2 concentration (

Figure 19). The majority of the analyzed samples are SSZ ophiolites, implying that the investigated serpentinite is represented by an ophiolitic mantle sequence pushed across the continental margin during the collision stage. The Pan-African ophiolites are considered as SSZ ophiolites or back-arc basin [

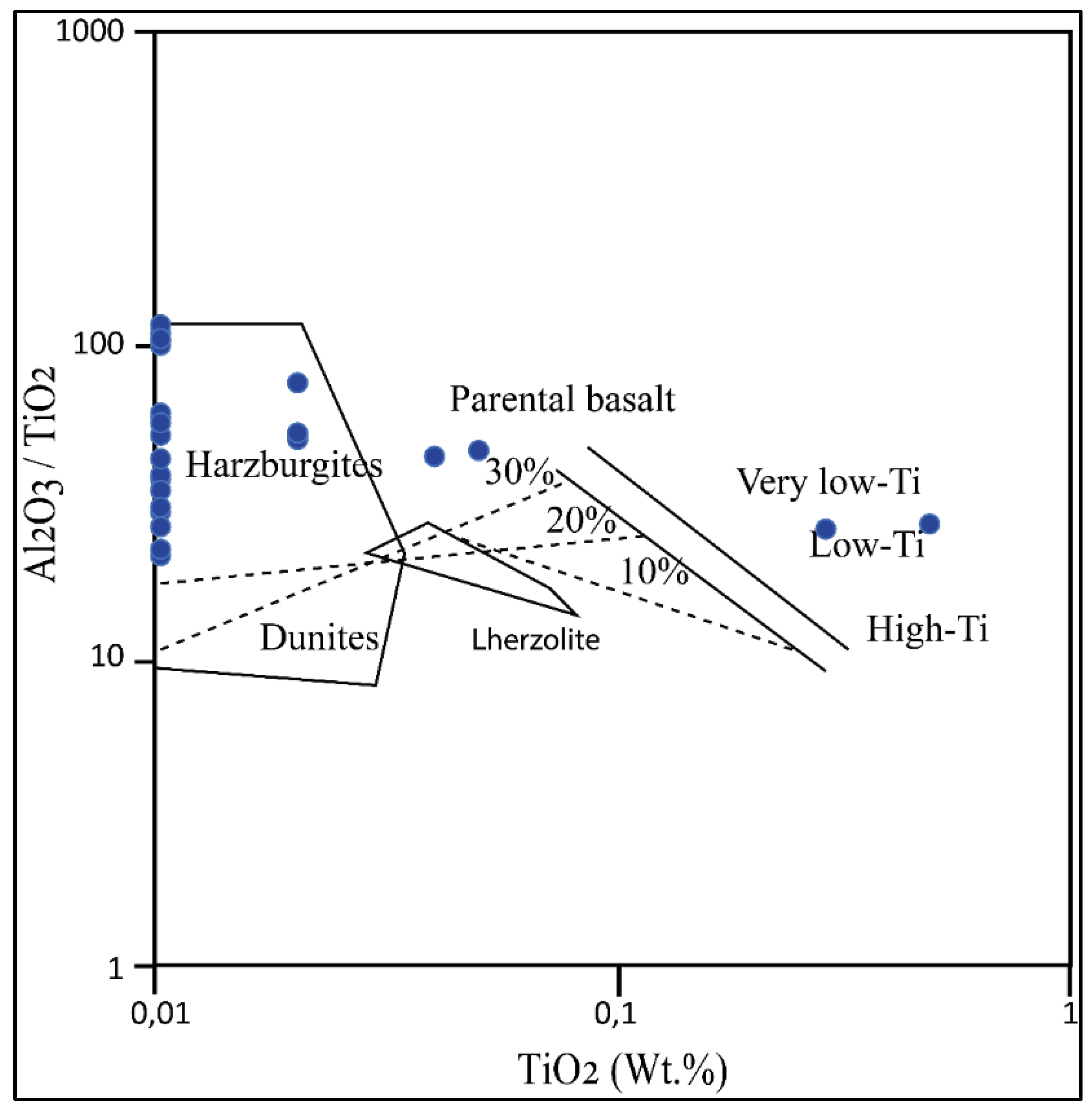

100]. Beccaluva et al. (1983) [

101] proposed a discrimination diagram for various basic and ultramafic rocks based on the Al2O3/TiO2 and TiO2 concentrations, where Al and Ti are thought to remain essentially stationary during the alteration processes [

102].

It is believed that the harzburgite foliate represents the mantle the molten fractions were almost completely extracted. [

103,

104,

105,

106]. Minor inhomogeneities can be seen as the form of foliated or non-foliated patches of dunite and lherzolite, pyroxenite veins, and gabbroic veins. Mixed patches of tectonite plagioclase lherzolite and lherzolite appear to be intimately connected with and genetically connected to this residual harzburgite in some ophiolites. The plagioclase lherzolite, which represents possible primary mantle material [

107], commonly displays evidence of an incomplete extraction process in which basaltic liquid was being removed. Such liquids have crystallized as gabbroic (ol plag -cpx-J-opx) assemblage pods or schlieren in a host of lherzolite or plagioclase lherzolite. [

108]. In garnet lherzolites as clinopyroxene garnet peridotites, incomplete separation and in-situ crystallization of a generated basalt extract were also observed. [

103,

109].

In the Bou Azzer context, it is therefore hypothesised that these lherzolites may record a two-stage mantle evolution. The initial phase of this process was characterised by partial melting, which resulted in a residue that was harzburgitic to dunite-like in composition. This residue was subsequently subjected to refertilisation via the percolation of basaltic melts during the generation of oceanic crust, a process that occurred within a supra-subduction zone setting.

The analyzed samples were plotted on the proposed diagram (

Figure 20), except for some samples that plot near the parental basalt boundary with partial melting ranges ranging from 10% to 30%. It is important to note that the studied serpentinites were derived from ultramafic rocks (tectonic mantle sequence).

This interpretation is consistent with the geodynamic model conceptualized for Bou Azzer, in which mantle rocks were tectonically emplaced during the obduction of an oceanic lithospheric slab. The geochemistry and mineralogy of the Bou Azzer peridotites are indicative of significant melt-rock interaction and fluid flux, which have been identified as the key processes in the evolution of this particular section of mantle rock. This assertion is supported by the observed spatial association with dunites and chromitites, as well as the documented record of late-stage hydration and serpentinization. The integrated model that has been devised to explain the geochemistry and mineralogy of the Bou Azzer peridotites situates them within the general context of supra-subduction zone ophiolites. In this framework, mantle refertilization, melt channeling, and fluid-assisted metasomatism are key features that exert control on the composition and mineralogy of these ophiolite bodies.

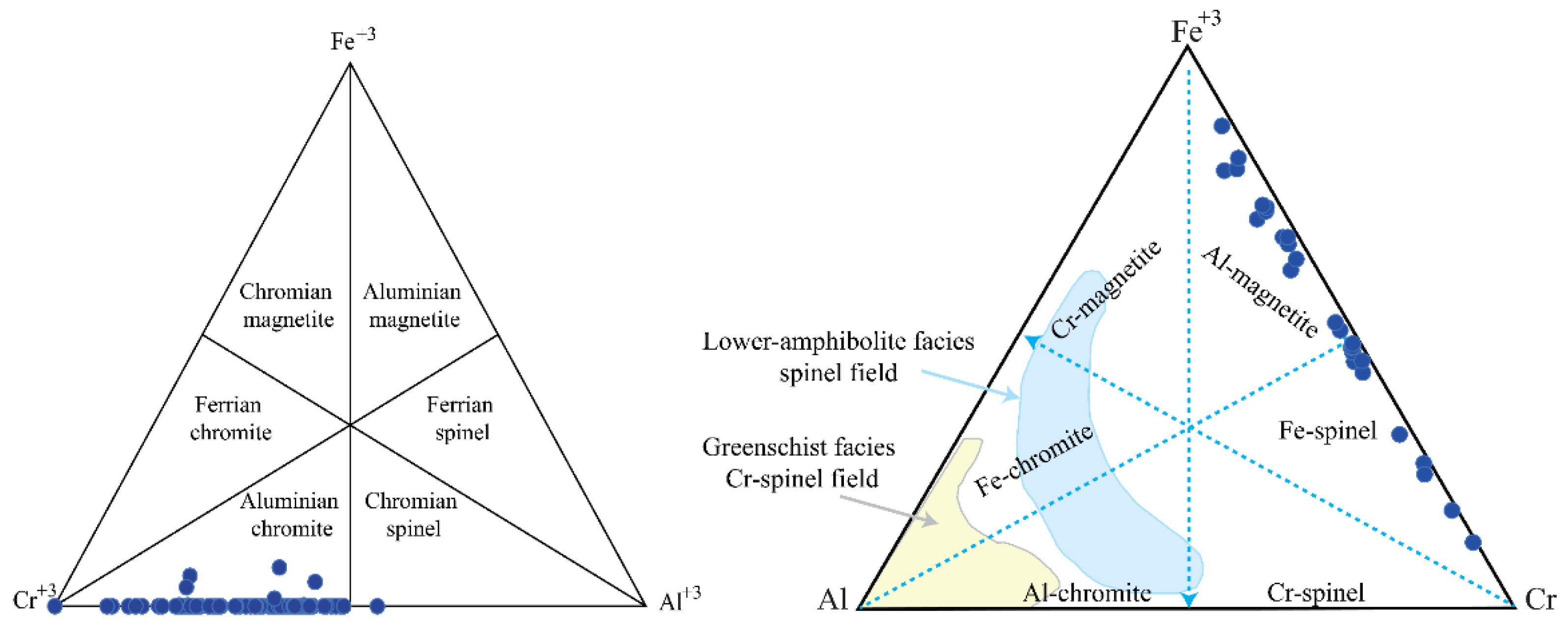

5.3. Chemistry of Chromite

Chromite is usually homogeneous and free of any exsolution. It can be found as isolated grains surrounded by silicate minerals or as chain-like aggregates. The individual chromite crystals are spherical or subhedral with jagged borders. There are also skeletal chromite crystals and fine chromite-silicate myrmikite intergrowths. In reflected light, chromite appears gray and has a poor reflectivity. Alternate chromite grains, on the other hand, have a pale gray tone with a faint-creamy or pale brownish tinge and a greater reflectivity than chromite. Some chromite samples have varying colors owing to the existence of small fissures that create a thin splinter reflection of incoming light. These fractures serve as paths for the transportation of hydrothermal fluids, which cause the transformation of the chromite grains. These fractures show as undulated or curved cracks with a fine-dendritic texture and a brecciaed appearance (

Figure 6).

The geological framework for the formation of ultramafic complexes is best understood using indicators such as the concentration of Cr, Al, and Ti in Cr spinel [

65,

110,

111]. Chromite and Cr-spinel are observed in all the Bou Azzer studied serpentinites. Microprobe analyses of chromite of Bou Azzer and its structural formulae are calculated from the major oxide contents, based on 32 oxygen (

Table 5). They are characterized by Cr

# = [Cr/(Cr+Al)] and Mg

# = [Mg/(Mg+Fe

2+)] of 0.5-0.676 and 0.43-0.77. The Cr-spinels have low 100*Fe

3+/(Fe

3++Cr+Al) = 0 in preserved core and sometimes = 23 in rims. TiO

2 is also low ≤ 0.18 wt.%. MnO ≤ 0.44 wt.% and NiO ≤0.21 wt.%.

The statistical treatment of the chromite compositions reveals a dominant trend of Cr-rich spinels with relatively low Fe and variable Al and Mg contents. The average Cr content (~1.7–1.9 apfu) indicates strong Cr-enrichment typical of chromite crystallized in a supra-subduction zone (SSZ) setting, where high degrees of partial melting favor Cr-spinel stability. Fe shows broad variability (0.2–0.8 apfu), reflecting both primary magmatic controls and possible subsolidus re-equilibration during serpentinization or metamorphism. Al values are relatively low to moderate (0.4–1.0 apfu), suggesting formation under depleted mantle conditions, whereas Mg remains consistently moderate (~0.3–0.5 apfu), indicating a restricted range of Mg–Fe exchange. Overall, the dataset indicates mantle wedge chromites that record high degrees of depletion and melt–rock interaction, consistent with SSZ ophiolitic settings, such as Bou Azzer.

The statistical treatment of the chromite compositions reveals a dominant trend of Cr-rich spinels with relatively low Fe and variable Al and Mg contents. The average Cr content (~1.7–1.9 apfu) indicates strong Cr-enrichment typical of chromite crystallized in a supra-subduction zone (SSZ) setting, where high degrees of partial melting favor Cr-spinel stability. Fe shows broad variability (0.2–0.8 apfu), reflecting both primary magmatic controls and possible subsolidus re-equilibration during serpentinization or metamorphism. All values are relatively low to moderate (0.4–1.0 apfu), suggesting formation under depleted mantle conditions, whereas Mg remains consistently moderate (~0.3–0.5 apfu), indicating a restricted range of Mg–Fe exchange. Overall, the dataset indicates mantle wedge chromites that record high degrees of depletion and melt–rock interaction, consistent with SSZ ophiolitic settings, such as Bou Azzer.

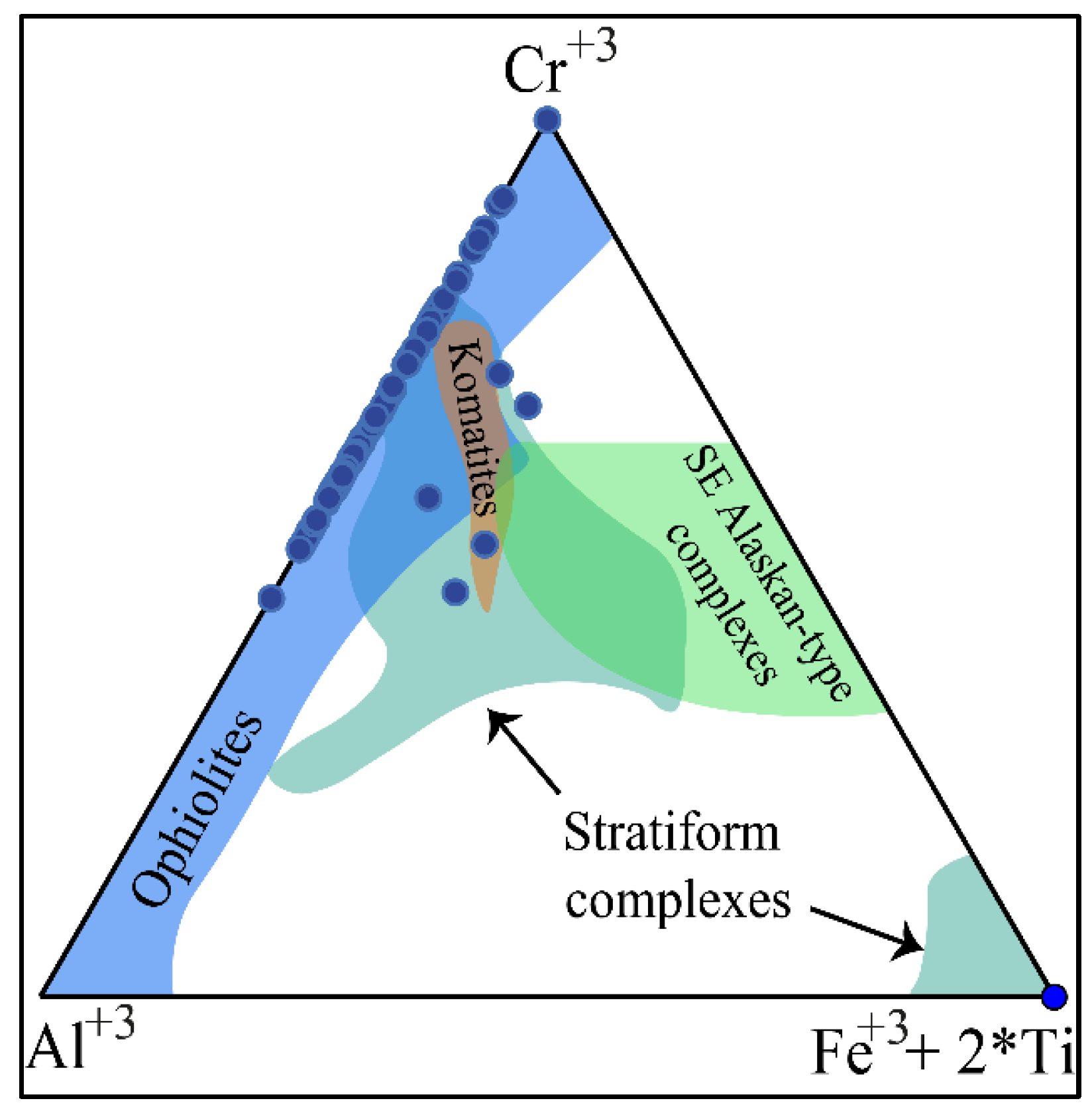

On the Fe

+3–Cr

+3–Al diagram (after Thayer, 1964 [

112]), the studied samples are from the aluminum chromite field (

Figure 21a).

Chromite cores that are constantly equilibrated with magnetite rims record metamorphic grade conditions [

113]. The relative proportions of chromite's trivalent ions (i.e., Cr

3+, Al

3+, and Fe

3+) are unchanged by metamorphism up to lower temperature amphibolite facies, showing that these elements' mobility was constrained under lower temperature amphibolite facies [

113]. As a result, chromite in lower temperature amphibolite facies retains its primary igneous chemistry and may be utilized to determine the metamorphic grade [

113]. So, they reflect magmatic composition not influenced by metamorphism [

113]. On the other hand, altered chromite rims have nearly pure magnetite compositions with restricted Cr-solubility (

Figure 21b), indicating magnetite development at < 500°C [

113,

114].

Figure 21.

Plot of chromites on a Cr–Fe3+–Al ternary diagram. (

a) Variation of Cr+3–Al+3–Fe+3 for Bou Azzer chromite (after Thayer, 1964)[

112]. (

b). Spinel data from the studied rocks compared with Sack & Ghiorso, (1991) [

114] spinel stability fields for chromite and magnetite (after Barnes 2000 [

113]).

Figure 21.

Plot of chromites on a Cr–Fe3+–Al ternary diagram. (

a) Variation of Cr+3–Al+3–Fe+3 for Bou Azzer chromite (after Thayer, 1964)[

112]. (

b). Spinel data from the studied rocks compared with Sack & Ghiorso, (1991) [

114] spinel stability fields for chromite and magnetite (after Barnes 2000 [

113]).

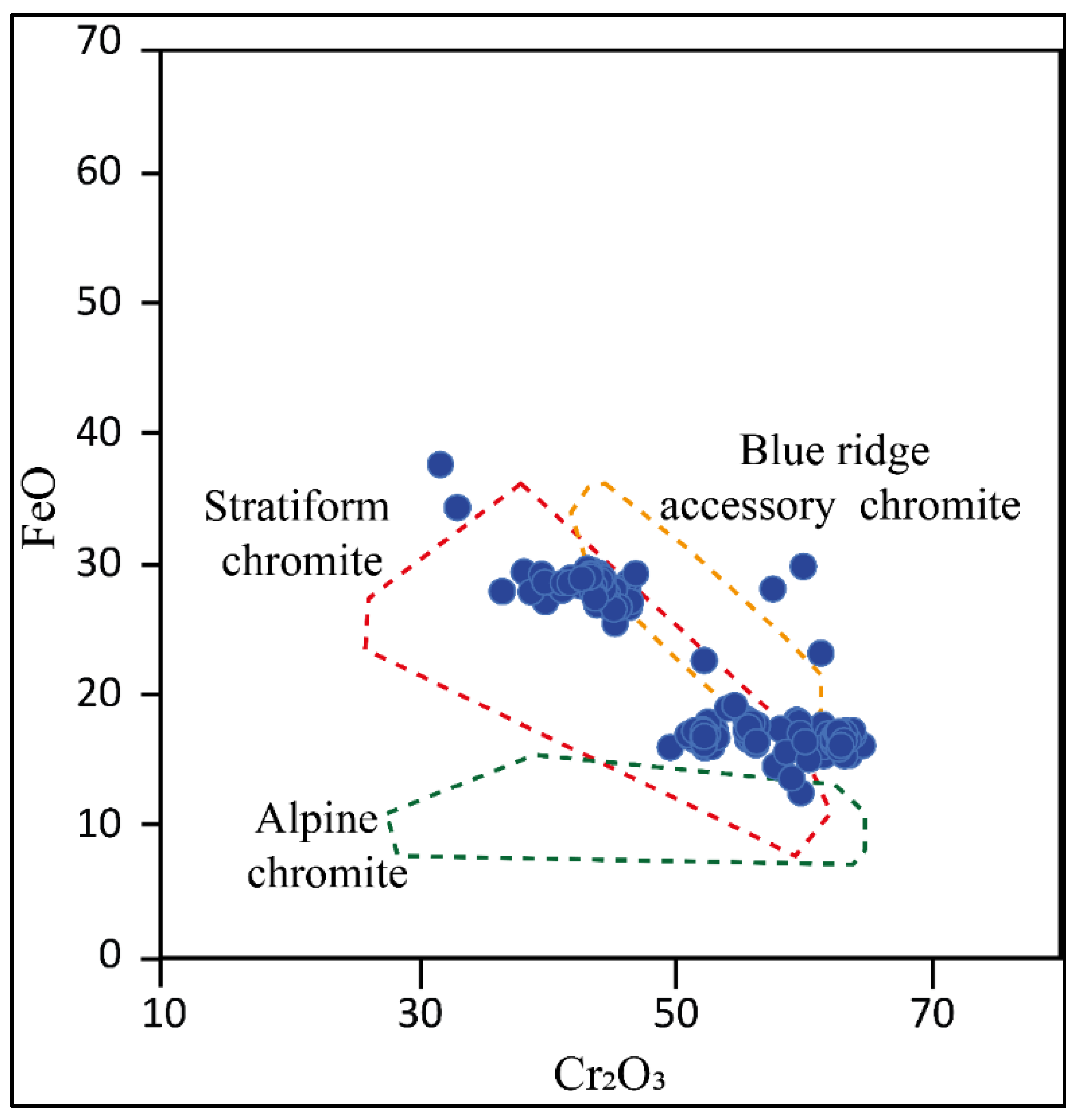

It is also found that the majority of the chromites analyzed plot in the Stratiform chromite and Alpine type fields, with few samples plotting in the Blue Ridge field (pieces of disrupted ophiolites), in the Cr

2O

3 and FeO diagram, after Thayer (1970) [

115] (

Figure 22).

Moreover, it is observed that all the analyzed chromite samples plot in the Alpine field and in the stratiform field. On the Cr

+3–Al–Fe

+3+ 2Ti diagram [

116] (

Figure 23).

The analyzed samples also plot in the area of residual peridotite podiform chromitites close to the stratiform komatite field. They are associated with harzburgite-dunite, orthopyroxenite, and wehrlite. Allen (1975) considers the low TiO

2 value (up to 0.3 percent) and the absence of a substantial association between titanium and the other elements to be distinguishing characteristics of Alpine-type chromite deposits [

117]. The podiform chromite is characterized by its low TiO

2 (0.3 wt.%) and MnO (0.27 wt.%) concentration. The presence of podiform chromites in the serpentinites is related typically to SSZ ophiolites [

118].

Figure 23.

Studied chromite plotted on the Cr+3–Al+3–(Fe+3+ 2Ti) diagram (after Jan & Windley, 1990 [

119]).

Figure 23.

Studied chromite plotted on the Cr+3–Al+3–(Fe+3+ 2Ti) diagram (after Jan & Windley, 1990 [

119]).

6. Conclusions

The Bou Azzer serpentinites constitute prominent lenticular ultramafic bodies, which extend in a NW–SE direction across the Central Anti-Atlas. These are tectonically emplaced within a lithologic assemblage of schists, basic metavolcanics, and ophiolitic metagabbros. Field and geochemical investigations indicate that serpentinites are low-temperature Alpine-type ophiolites. They belong to the ophiolitic mantle sequence formed in SSZ ophiolites, which were thrust over the continental margins during the collisional stage of the back-arc environment. SSZ ophiolites can also occur in the early phases of arc splitting and are distinguished by significantly depleted, harzburgite mantle sequences featuring podiform chromite deposits and crystallization sequences that include olivine followed by pyroxene. The mineralogy of the ultamafic rocks is dominated by antigorite, with lesser lizardite and chrysotile, and subordinate phases including magnesite, talc, dolomite, chromite, and chlorite. The textures – mesh, bastite, and knit – are indicative of intense serpentinization subsequent to deformation of harzburgitic and dunitic protoliths. The presence of clinochrysotile veinlets cutting through other serpentinite minerals indicates that the minerals were crystallized in a static state at a late stage, under the influence of meteoric fluids. The transition from lizardite and chrysotile to antigorite marks the onset of greenschist facies metamorphism.

Geochemically, these serpentinites are derived from a depleted mantle source (harzburgite/dunite), consistent with fore-arc peridotites within a back-arc basin setting, with partial melting exceeding ~25% as inferred from chromite chemistry. The observed continuous evolution from depleted harzburgite through moderately modified lherzolite to slightly refertilized plagioclase–lherzolite reflects a similar petrogenetic pattern seen in SSZ ophiolites globally. Microprobe investigations of chromite reveal that it is of the aluminum chromite type. The podiform chromite has low TiO2 (0.3 content) and MnO (0.27% content), which are distinguishing properties of Alpine-type chromite deposits. The chromite, like ophiolitic podiform chromites, has a low Al concentration compared to Cr+3. Podiform chromites in serpentinites are typically related to SSZ ophiolites. The spatial and temporal relationship between talc deposits and magnesite veins, and sheared serpentinite zones is well-documented. Both phenomena are the result of CO2-rich metasomatism during or after major serpentinisation. The presence of chromite pods of podiform geometry, low Ti and Mn contents, and high Cr# (approximately 0.65–0.85) further reinforces the SSZ (supra-subduction zone) signature.

The preponderance of field, petrographic, mineral chemical, and geochemical evidence provides substantial support for the hypothesis that the Bou Azzer ultramafic units have their origin in a supra-subduction zone. Their evolution involved: The process under investigation may be summarized as follows: firstly, the extraction of basaltic melts from a refractory mantle; secondly, the infiltration of fluids and melts in an arc-back-arc environment; thirdly, the serpentinization, refertilization, and late-stage metasomatic alteration (including CO2 input); and fourthly, the tectonic emplacement during obduction onto the continental margin beneath West African Craton during Pharusian ocean closure, during Panafrican orogeny.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There has been no funding received for this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and investigation, A.W., R.R and M.B.M.; validation, A.W., S.N., A.S and AB.P.; formal analysis, A.W., M.B.M., and Y.A.; resources, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W.; writing—review and editing, A.W. M.B.M.; AB.P.; S.N.; Y.A; A.A.L.; A.S and I.A.; funding acquisition, A.W; A.S All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Managem Group (Morocco) through the Essential Economic Minerals program, which made this research possible. We also thank the Faculty of Sciences and Technology, University of Lorraine.

References

- Dilek, Y.; Furnes, H. Ophiolite genesis and global tectonics: Geochemical and tectonic fingerprinting of ancient oceanic lithosphere. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2011, 123, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A. Immobile Element Fingerprinting of Ophiolites. Elements 2014, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, M. Ophiolites precambriennes et gites arsenies de cobalt : Bou Azzer (Maroc), 1975.

- Bodinier, J.L.; Dupuy, C.; Dostal, J. Geochemistry of Precambrian ophiolites from Bou Azzer, Morocco. Contrib. to Mineral. Petrol. 1984, 87, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D.D.; Bloomer, S.H.; Saquaque, A.; Hefferan, K. Geochemistry and significance of metavolcanic rocks from the Bou Azzer-El Graara ophiolite (Morocco). Precambrian Res. 1991, 53, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admou, H.; Soulaimani, A.; Mrini, Z. Les ophiolites néoprotérozoïques du Maroc: témoins de la tectonique panafricaine dans l’Anti-Atlas. In Geology of Morocco: The Geology of the Maghreb Belts and Tethys Margins; Springer, 2013; pp. 277–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hefferan, K.; Soulaimani, A.; Samson, S.D.; Admou, H.; Inglis, J.; Saquaque, A.; Latifa, C.; Heywood, N. A reconsideration of Pan African orogenic cycle in the Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco. J. African Earth Sci. 2014, 98, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafik, A. Etude géochimique et métallogénique d’un système hydrothermal océanique fossile : Exemple des minéralisations cuprifères dans les ophiolites protérozoïques de l’Anti Atlas central (Maroc). Thèse d’état. Univ Cadi Ayyad. Marrakech. N° 314. p195.

- Wafik, A.; Saquaque, A.; El Boukhari, A. Les chromitites podiformes et les mineraux de fe-cu-ni-co associes a l’ophiolite de bou azzer-el graara (anti-atlas central, Maroc). Ofioliti 2001, 26, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafik, A.; Zoheir, B.; Benchekroun, F.; Benaouda, R.; Ben Massoude, M.; Atif, Y.; Beiranvand Pour, A.; Niroomand, S.; El Arbaoui, A.; Karfal, A.; et al. Multistage Gold-Polymetallic Mineralization in the Bou Azzer District, Anti-Atlas, Morocco: Insights from Ore Microscopic, Geochemical, and Fluid Inclusion Studies. Geofluids 2024, 2024 AR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafik, A.; Visalli, R.; Punturo, R.; Conte, A.M.; Guglietta, D.; Ben Massoude, M.; El Aouad, N.; Mabika, N.N.; Cirrincione, R. Neoproterozoic serpentinites from the Bou Azzer ophiolite, Central Anti-Atlas (Morocco): geodynamic evolution and mantle processes beneath the West African Craton boundaries. Ital. J. Geosci. 2025, 144, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquaque, A.; Admou, H.; Karson, J.; Hefferan, K.; Reuber, I. Precambrian accretionary tectonics in the Bou Azzer-El Graara region, Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Geology 1989, 17, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, M. The Late Proterozoic Ophiolites of Bou Azzer (Morocco): Evidence for Pan-African Plate Tectonics. Dev. Precambrian Geol. 1981, 4, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, R. L’ophiolite de Bou-Azzer (Anti-Atlas, Maroc), Structures, Pétrographie, Géochimie, et Contexte de mise en place. Université Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- AHMED, A.; ARAI, S.; ABDELAZIZ, Y.; RAHIMI, A. Spinel composition as a petrogenetic indicator of the mantle section in the Neoproterozoic Bou Azzer ophiolite, Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Precambrian Res. 2005, 138, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, M.; Lancelot, J.R. Interprétation géodynamique du domaine pan-africain (Précambrien terminal) de l’Anti-Atlas (Maroc) à partir de données géologiques et géochronologiques. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1980, 17, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, F.; Godard, M.; Guillot, S.; Hattori, K. Geochemistry of subduction zone serpentinites: A review. Lithos 2013, 178, 96–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, N.G.; Klein, F.; Seewald, J.S.; Sylva, S.P. Experimental study of carbonate formation in oceanic peridotite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 199, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionov, D.A.; Hofmann, A.W. NbTa-rich mantle amphiboles and micas: Implications for subduction-related metasomatic trace element fractionations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1995, 131, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouteau, G.; Scaillet, B.; Pichavant, M.; Maury, R. Evidence for mantle metasomatism by hydrous silicic melts derived from subducted oceanic crust. Nature 2001, 410, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIU, Y. Bulk-rock Major and Trace Element Compositions of Abyssal Peridotites: Implications for Mantle Melting, Melt Extraction and Post-melting Processes Beneath Mid-Ocean Ridges. J. Petrol. 2004, 45, 2423–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, Y.; Morishita, T. Melt migration and upper mantle evolution during incipient arc construction: Jurassic Eastern Mirdita ophiolite, Albania. Isl. Arc 2009, 18, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, İ.; Ersoy, E.Y.; Karslı, O.; Dilek, Y.; Sadıklar, M.B.; Ottley, C.J.; Tiepolo, M.; Meisel, T. Coexistence of abyssal and ultra-depleted SSZ type mantle peridotites in a Neo-Tethyan Ophiolite in SW Turkey: Constraints from mineral composition, whole-rock geochemistry (major–trace–REE–PGE), and Re–Os isotope systematics. Lithos 2012, 132–133, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J. Trace element modeling of aqueous fluid - peridotite interaction in the mantle wedge of subduction zones. Contrib. to Mineral. Petrol. 1998, 132, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Parkinson, I.J. Trace element models for mantle melting: application to volcanic arc petrogenesis. Geol. Soc. London, Spec. Publ. 1993, 76, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Fekkak, A.; Ennih, N.; Errami, E.; Loughlin, S.C.; Gresse, P.G.; Chevallier, L.P.; Liégeois, J.-P. A new lithostratigraphic framework for the Anti-Atlas Orogen, Morocco. J. African Earth Sci. 2004, 39, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennih, N.; Liégeois, J.P. The Moroccan Anti-Atlas: The West African craton passive margin with limited Pan-African activity. Implications for the northern limit of the craton. Precambrian Res. 2001, 112, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbey, P.; Oberli, F.; Burg, J.P.; Nachit, H.; Pons, J.; Meier, M. The Paleoproterozoic in western Anti-Atlas (Morocco): a clarification. J. African Earth Sci 39 2004, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubert, G. Histoire géologique du Précambrien de l’Anti-Atlas. Notes Mem. 1963, 162. 352 p. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, M. Proterozoic oceanic crust at Bou Azzer. Nature 1976, 261, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollard, H.; Choubert, G.; Bronner, G.; Marchand, J.; Sougy, J. Carte géologique du Maroc, échelle: 1/1.000.000. Notes Mémoires du Serv. Géologique du Maroc 1985. 260 p. [Google Scholar]

- Gasquet, D.; Levresse, G.; Cheilletz, A.; Azizi-Samir, M.R.; Mouttaqi, A. Contribution to a geodynamic reconstruction of the Anti-Atlas (Morocco) during Pan-African times with the emphasis on inversion tectonics and metallogenic activity at the Precambrian-Cambrian transition. Precambrian Res. 2005, 140, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuduri, J.; Chauvet, A.; Barbanson, L.; Bourdier, J.-L.; Labriki, M.; Ennaciri, A.; Badra, L.; Dubois, M.; Ennaciri-Leloix, C.; Sizaret, S.; et al. The Jbel Saghro Au(–Ag, Cu) and Ag–Hg Metallogenetic Province: Product of a Long-Lived Ediacaran Tectono-Magmatic Evolution in the Moroccan Anti-Atlas. Minerals 2018, 8, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, M.; Caritg, S.; Helg, U.; Robert-Charrue, C.; Soulaimani, A. Tectonics of the Anti-Atlas of Morocco. Comptes Rendus - Geosci. 2006, 338, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missenard, Y.; Zeyen, H.; Frizon de Lamotte, D.; Leturmy, P.; Petit, C.; Sébrier, M.; Saddiqi, O. Crustal versus asthenospheric origin of relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauer, N. Géochimie isotopique du strontium des milieux sédimentaires. Application à la géochronologie de la couverture du craton ouest-africain. Sci. Géologiques, Bull. mémoires 1976, 45, 227. [Google Scholar]

- D’Lemos, R.S.; Inglis, J.D.; Samson, S.D. A newly discovered orogenic event in Morocco: Neoproterozoic ages for supposed Eburnean basement of the Bou Azzer inlier, Anti-Atlas Mountains. Precambrian Res. 2006, 147, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blein, O.; Baudin, T.; Chèvremont, P.; Soulaimani, A.; Admou, H.; Gasquet, P.; Cocherie, A.; Egal, E.; Youbi, N.; Razin, P.; et al. Geochronological constraints on the polycyclic magmatism in the Bou Azzer-El Graara inlier (central Anti-Atlas Morocco). J. African Earth Sci. 2014, 99, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouougri, E.H.; Lahna, A.A.; Tassinari, C.C.G.; Basei, M.A.S.; Youbi, N.; Admou, H.; Saquaque, A.; Boumehdi, M.A.; Maacha, L. Time constraints on Early Tonian Rifting and Cryogenian Arc terrane-continent convergence along the northern margin of the West African craton: Insights from SHRIMP and LA-ICP-MS zircon geochronology in the Pan-African Anti-Atlas belt (Morocco). Gondwana Res. 2020, 85, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodel, F.; Triantafyllou, A.; Berger, J.; Macouin, M.; Baele, J.M.; Mattielli, N.; Monnier, C.; Trindade, R.I.F.; Ducea, M.N.; Chatir, A.; et al. The Moroccan Anti-Atlas ophiolites: Timing and melting processes in an intra-oceanic arc-back-arc environment. Gondwana Res. 2020, 86, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekiout, B. Stratigraphie, pétrographie, géochimie et structure de l’ensemble arc/avant arc de la Boutonnière de Bou Azzer-El Graara (unité nord) Anti-Atlas Maroc. Thèse 3ème Cycle, Cadi Ayyad Univ. Marrakech, Morocco, 1991; 151p. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllou, A.; Berger, J.; Baele, J.M.; Bruguier, O.; Diot, H.; Ennih, N.; Monnier, C.; Plissart, G.; Vandycke, S.; Watlet, A. Intra-oceanic arc growth driven by magmatic and tectonic processes recorded in the Neoproterozoic Bougmane arc complex (Anti-Atlas, Morocco). Precambrian Res. 2018, 304, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, A.; Soulaimani, A.; Hoepffner, C.; Ouanaimi, H.; Baidder, L.; Rjimati, E.C.; Saddiqi, O. The South-Western Branch of the Variscan Belt: Evidence from Morocco. Tectonophysics 2010, 492, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.J.; Benziane, F.; Aleinikoff, J.N.; Harrison, R.W.; Yazidi, A.; Burton, W.C.; Quick, J.E.; Saadane, A. Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution of the Jebel Saghro and Bou Azzer-El Graara inliers, eastern and central Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Precambrian Res. 2012, 216–219, 23–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlan, H.A.; Arai, S.; Ahmed, A.H.; Ishida, Y.; Abdel-Aziz, Y.M.; Rahimi, A. Origin of magnetite veins in serpentinite from the Late Proterozoic Bou-Azzer ophiolite, Anti-Atlas, Morocco: An implication for mobility of iron during serpentinization. J. African Earth Sci. 2006, 46, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, J.D.; Samson, S.; D’Lemos, R.S.; Admou, H. Timing of regional greenschist facies deformation in the Bou Azzer Inlier, Anti-Atlas: U–Pb constraints from syn-tectonic intrusions. In Proceedings of the First meeting of IGCP 485, El Jadida, Morocco, 2003; pp. 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, S.D.; Inglis, J.D.; D’Lemos, R.S.; Admou, H.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Hefferan, K. Geochronological, geochemical, and Nd-Hf isotopic constraints on the origin of Neoproterozoic plagiogranites in the Tasriwine ophiolite, Anti-Atlas orogen, Morocco. Precambrian Res. 2004, 135, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hadi, H.; Simancas, J.F.; Martínez-Poyatos, D.; Azor, A.; Tahiri, A.; Montero, P.; Fanning, C.M.; Bea, F.; González-Lodeiro, F. Structural and geochronological constraints on the evolution of the Bou Azzer Neoproterozoic ophiolite (Anti-Atlas, Morocco). Precambrian Res. 2010, 182, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasquet, D.; Ennih, N.; Liégeois, J.P.; Soulaimani, A.; Michard, A. The pan-African belt. Lect. Notes Earth Sci. 2008, 116, 33–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulaimani, A.; Ouanaimi, H.; Saddiqi, O.; Baidder, L.; Michard, A. The Anti-Atlas Pan-African Belt (Morocco): Overview and pending questions. Comptes Rendus - Geosci. 2018, 350, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberthür, T.; Melcher, F.; Saumur, B. Precious and base metal mineralization associated with Neoproterozoic ophiolites in the Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Appl. Earth Sci. 2009, 118, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, I.J.; Pearce, J.A. Peridotites from the Izu-Bonin-Mariana forearc (ODP Leg 125): evidence for mantle melting and melt-mantle interaction in a supra-subduction zone setting. J. Petrol. 1998, 39, 1577–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Hékinian, R. Spreading-rate dependence of the extent of mantle melting beneath ocean ridges. Nature 1997, 385, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellebrand, E.; Snow, J.E.; Dick, H.J.B.; Hofmann, A.W. Coupled major and trace elements as indicators of the extent of melting in mid-ocean-ridge peridotites. Nature 2001, 410, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodolányi, J.; Pettke, T.; Spandler, C.; Kamber, B.S.; Gméling, K. Geochemistry of ocean floor and fore-arc serpentinites: Constraints on the ultramafic input to subduction zones. J. Petrol. 2012, 53, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafik, A.; Bhilisse, M.; Admou, H.; Maacha, L.; Elghorfi, M. The Podiform Chromite and Platinum Group Elements in the Neoproterozoic Ophiolite Bou Azzer (Inlier Bou Azzer - El Graara, central Anti-Atlas). Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, J.B. Serpentinization: a review. Lithos 1976, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, R.A.; Butt, B.C. Chrysotile asbestos at Woodsreef, New South Wales. Econ. Geol. 1981, 76, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanley, D.S. The origin of the chrysotile asbestos veins in southeastern Quebec. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1987, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanley, D.S. The origin of alpine peridotite-hosted, cross fiber, chrysotile asbestos deposits. Econ. Geol. 1988, 83, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanley, D.S. Fault-related phenomena associated with hydration and serpentine recrystallization during serpentinization. Can. Mineral. 1991, 29, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanley, D.S. Serpentinites : records of tectonic and petrological history /; Oxford University Press: New York, 1996; ISBN 0195082540. (acid-free). [Google Scholar]

- Bonatti, E.; Michael, P.J. Mantle peridotites from continental rifts to ocean basins to subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1989, 91, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F.; Sun, S.S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, T.N. CHROMIAN SPINEL AS A PETROGENETIC INDICATOR: PART 2. PETROLOGIC APPLICATIONS. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1967, 4, 71–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodinier, J.-L.; Godard, M. Orogenic, Ophiolitic, and Abyssal Peridotites. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 103–167. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.P. Petrogenesis of ultramafic rocks and implications for mantle evolution. J. Petrol. 2022, 63 AR-e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.-J.; Lightfoot, P.C. Formation of magmatic Ni-Cu-(PGE) sulfide deposits and processes affecting their copper and platinum group element contents. In Economic Geology, 100th Anniversary Volume; 2005; pp. 179–213. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, M.; Lagabrielle, Y.; Alard, O.; Harvey, J. Geochemistry of the highly depleted peridotites drilled at ODP Sites 1272 and 1274 (Fifteen-Twenty Fracture Zone, Mid-Atlantic Ridge): Implications for mantle dynamics beneath a slow spreading ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 267, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canil, D. Vanadium in peridotites, mantle redox and tectonic environments: Archean to present. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 195, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagé, P.; Bédard, J.H.; Tremblay, A. Geochemical variations in Neoarchaean volcanic rocks of the southern Superior Province, Canada: Implications for the evolution of Archaean oceanic crust and subduction processes. Precambrian Res. 2008, 167, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.L.; Bristow, J.W. Low-velocity shear zones in ultramafic rocks. Tectonophysics 1980, 64, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A. Role of sub-continental lithosphere in magma genesis at active continental margins. In Continental Basalts and Mantle Xenoliths; Shiva, 1983; pp. 230–249. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, R.G. Plate tectonic emplacement of upper mantle peridotites along continental edges. J. Geophys. Res. 1971, 76, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mével, C. Serpentinisation des péridotites abysales aux dorsales océaniques. Comptes Rendus - Geosci. 2003, 335, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashiro, A.; Shido, F.; Ewing, M. Composition and origin of serpentinites from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near 24° and 30° North Latitude. Contrib. to Mineral. Petrol. 1969, 23, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.G. What is an Ophiolite? In; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1977; pp. 1–7.

- Frey, F.A.; John Suen, C.; Stockman, H.W. The Ronda high temperature peridotite: Geochemistry and petrogenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1985, 49, 2469–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, N.J. Mineralogy and chemistry of the serpentine group minerals and the serpent~,nization process. Diss. Univ. California, Berkeley, Calif 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, M.; Jousselin, D.; Bodinier, J.L. Relationships between geochemistry and structure beneath a palaeo-spreading centre: A study of the mantle section in the Oman ophiolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2000, 180, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodinier, J.-L.; Godard, M. Orogenic, ophiolitic and abyssal peridotites. In Treatise on Geochemistry, Vol. 3 (The Mantle and Core); Elsevier, 2007; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Barker, P.F.; Edwards, S.J.; Parkinson, I.J.; Leat, P.T. Geochemistry and tectonic significance of peridotites from the South Sandwich arc–basin system, South Atlantic. Contrib. to Mineral. Petrol. 2000, 139, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R. Geological Criteria for Evaluating Seismicity. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1975, 86, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salters, V.J.M.; Stracke, A. Composition of the depleted mantle. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]