Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

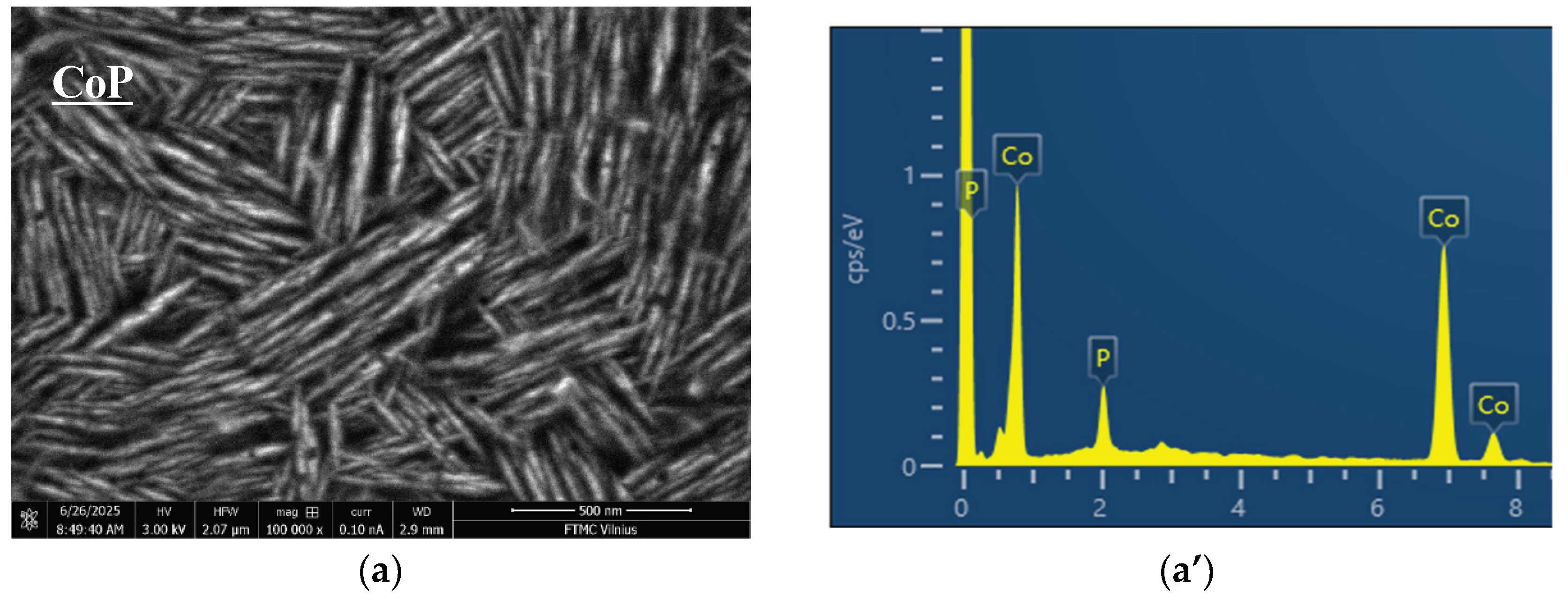

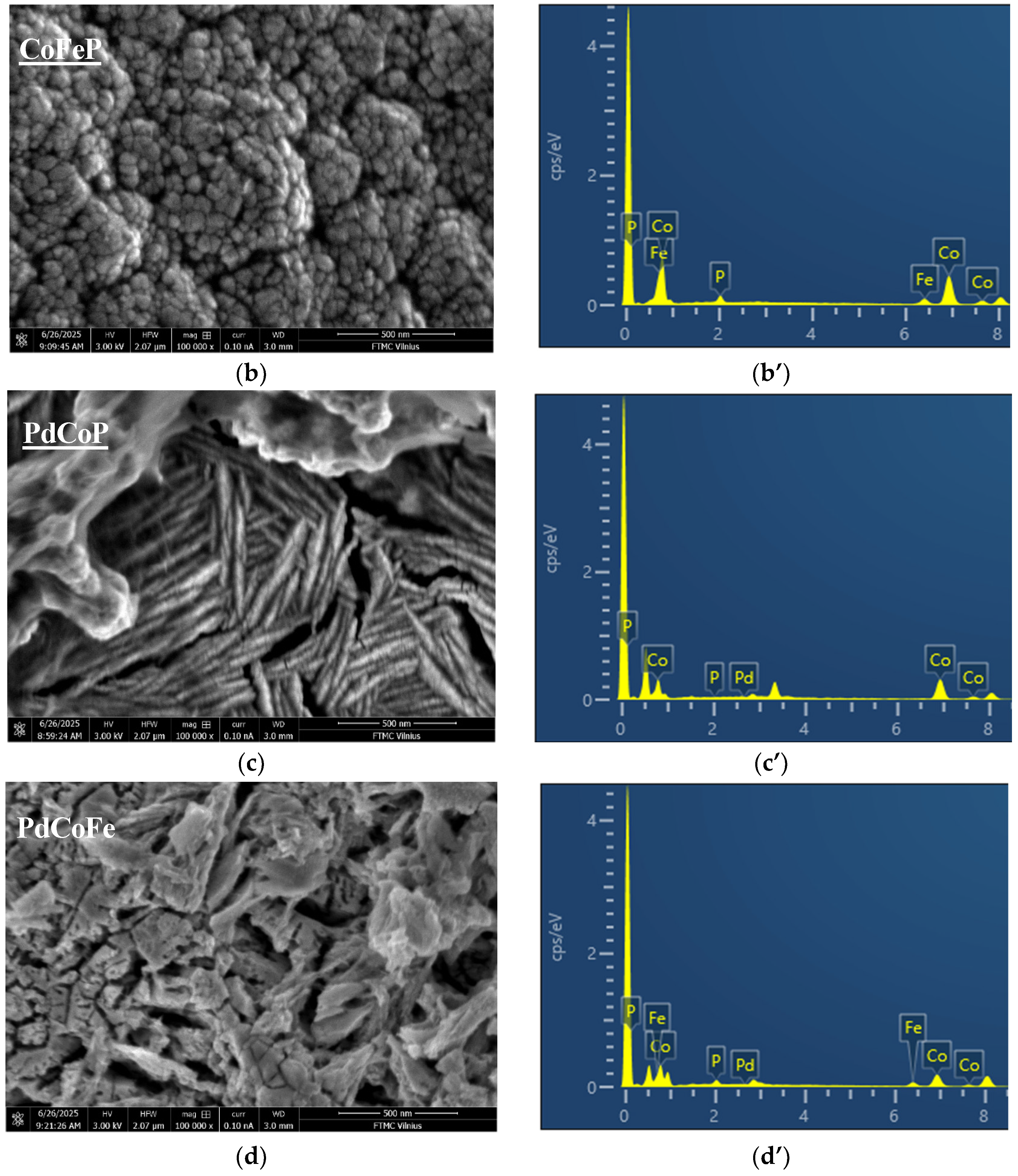

2.1. Coatings, Microstructure and Morphology Studies

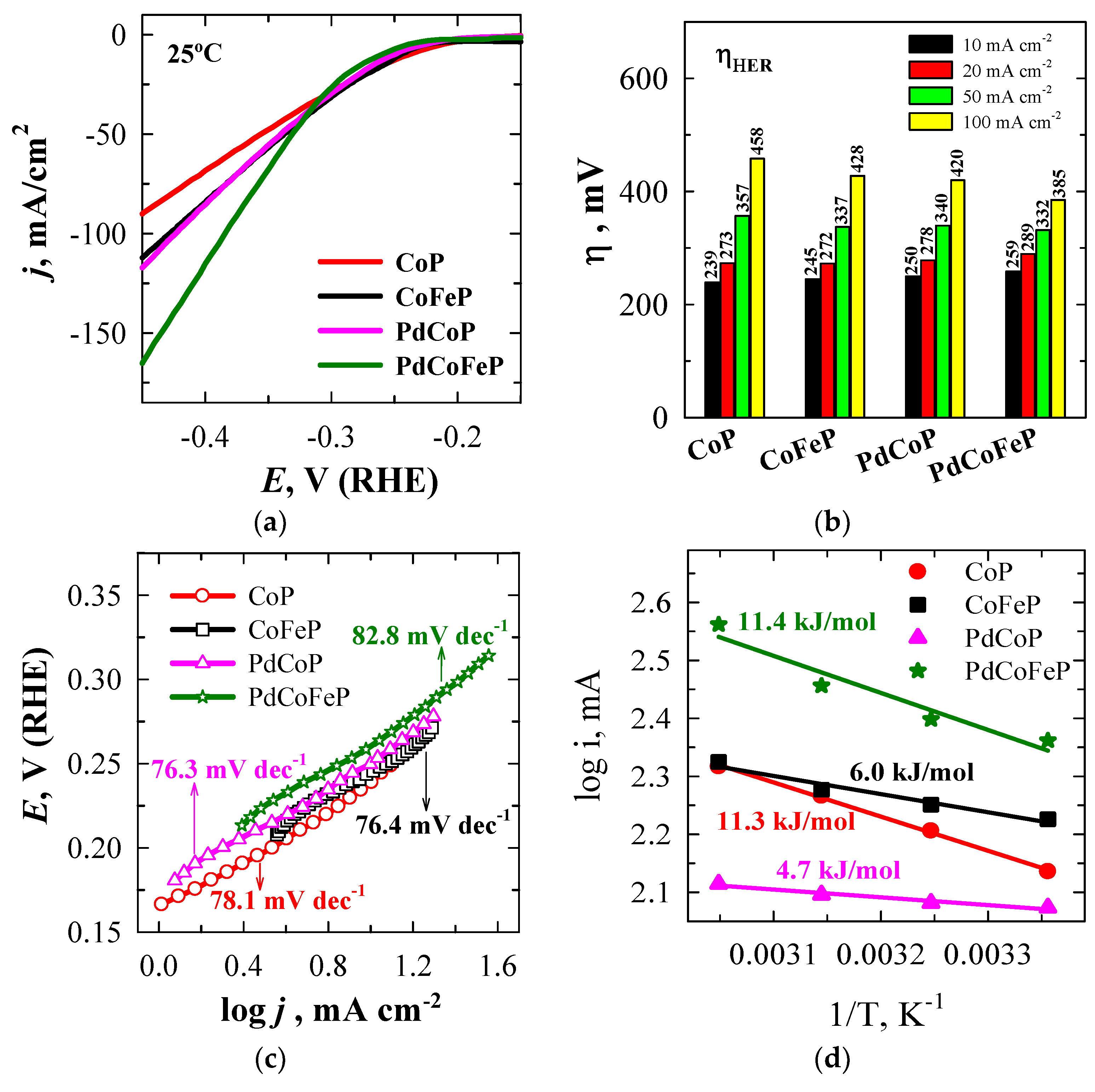

2.2. Electrocatalytic Activity Towards HER

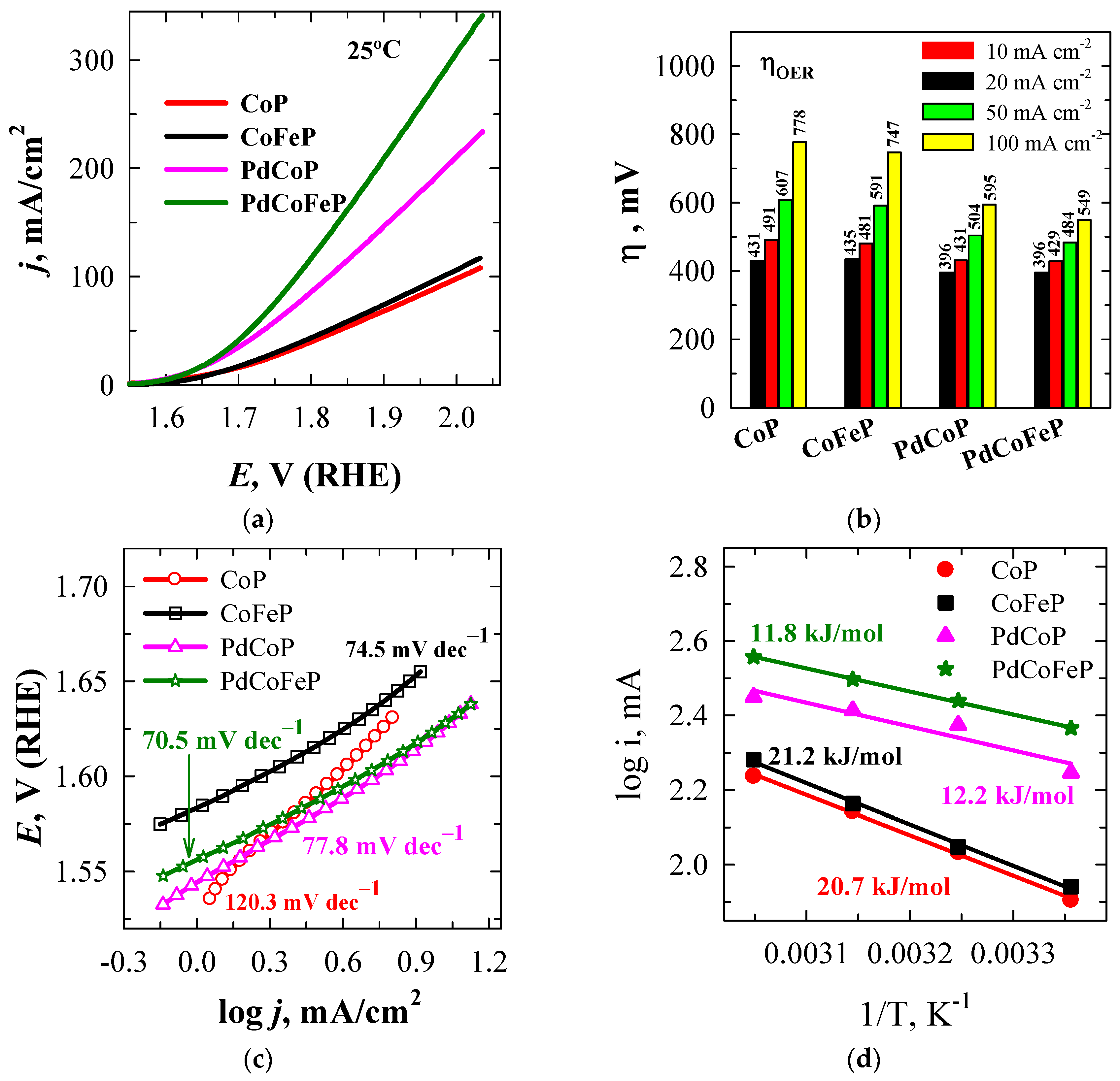

2.3. Electrocatalytic Activity Towards OER

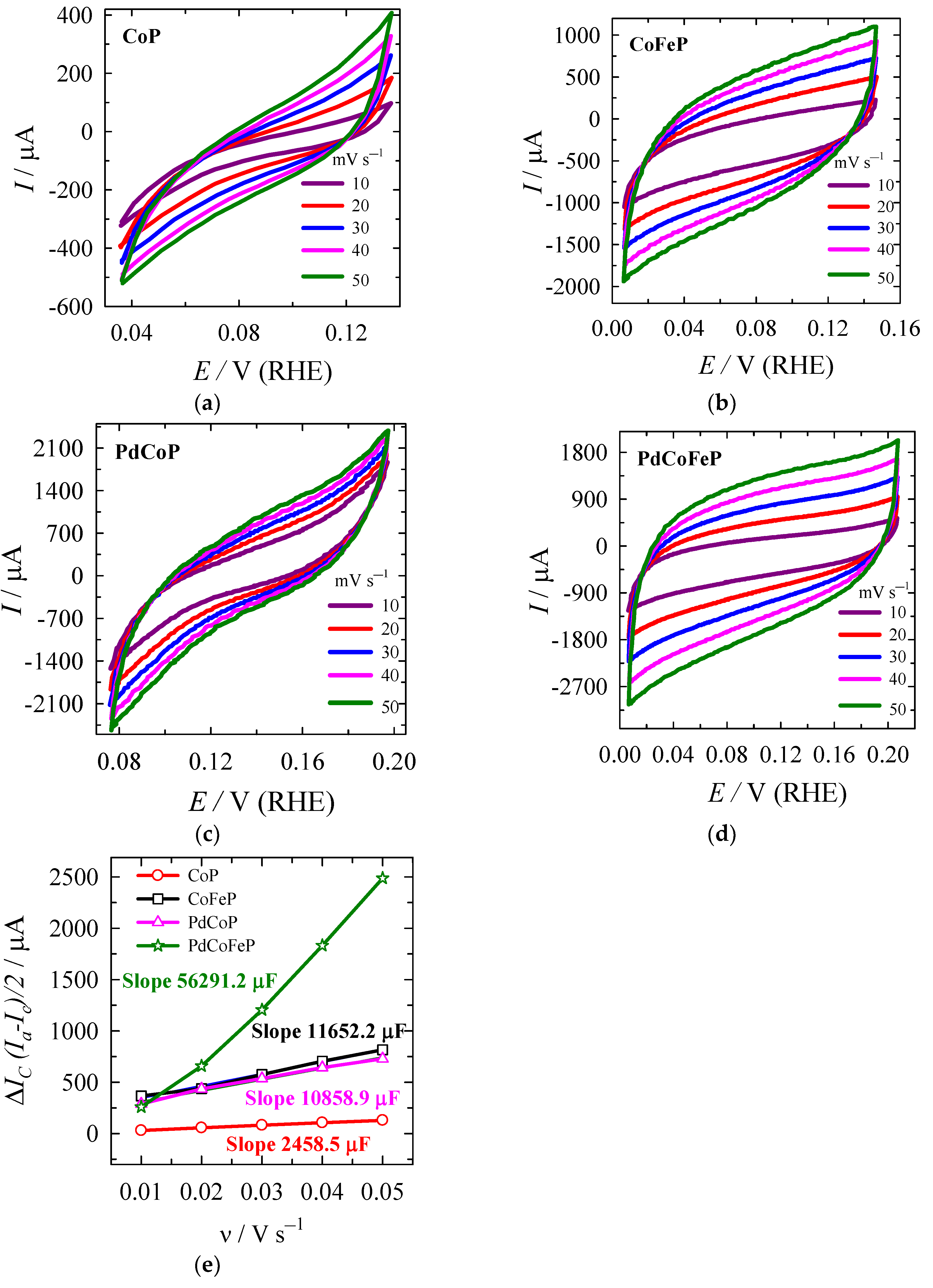

2.4. Determination of Electrochemically Active Surface Areas

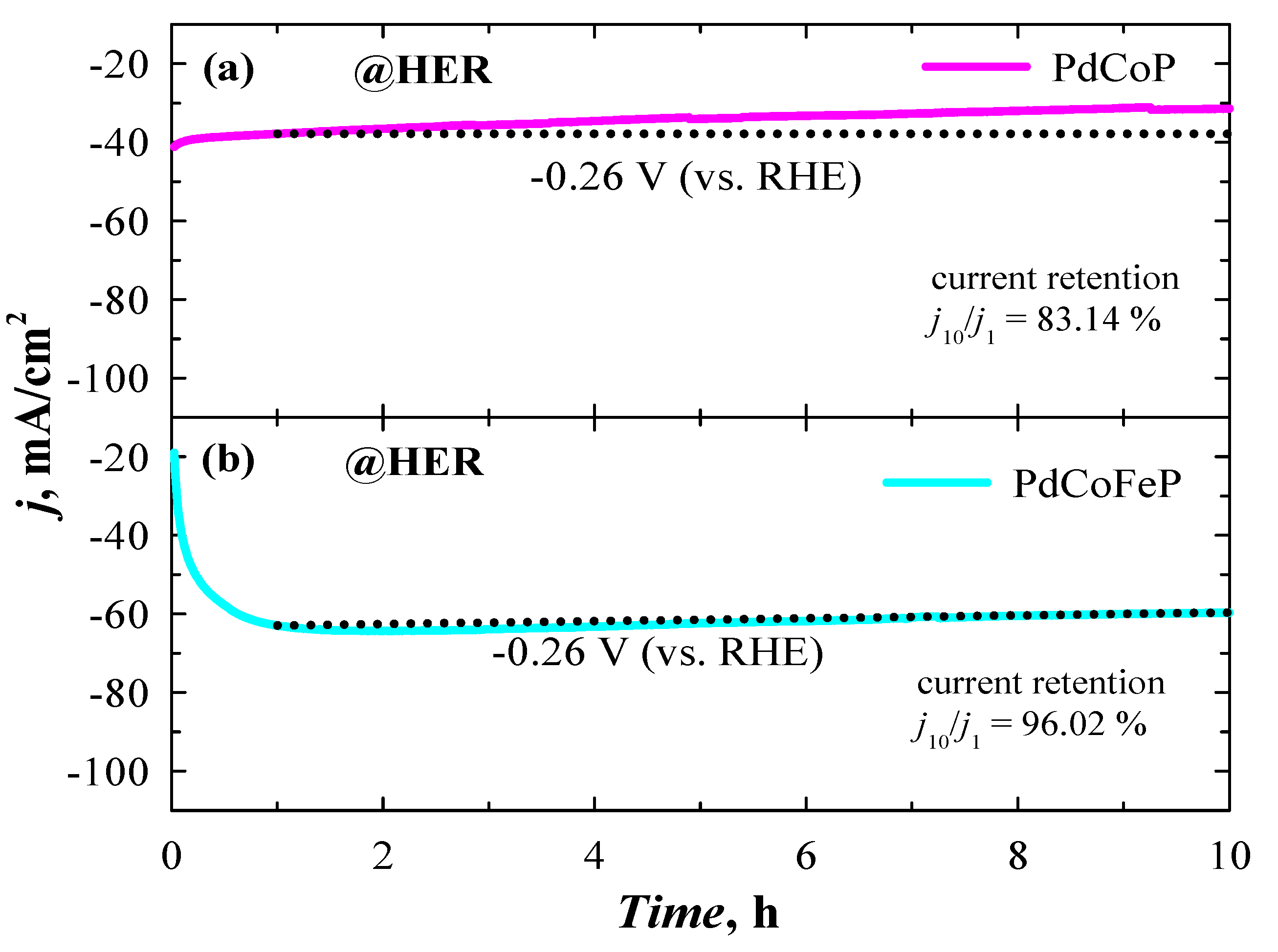

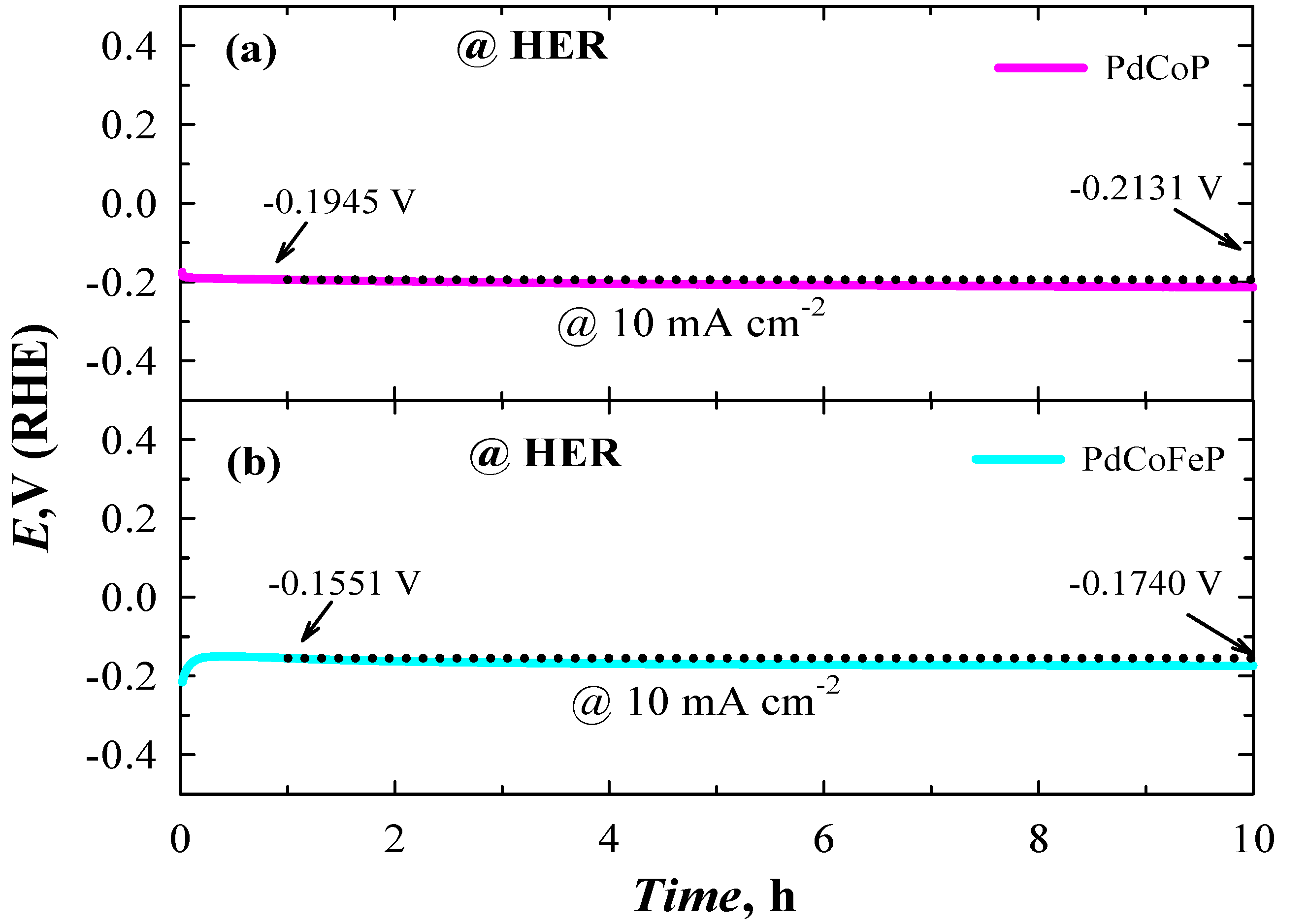

2.5. Investigation of Stability of Catalysts

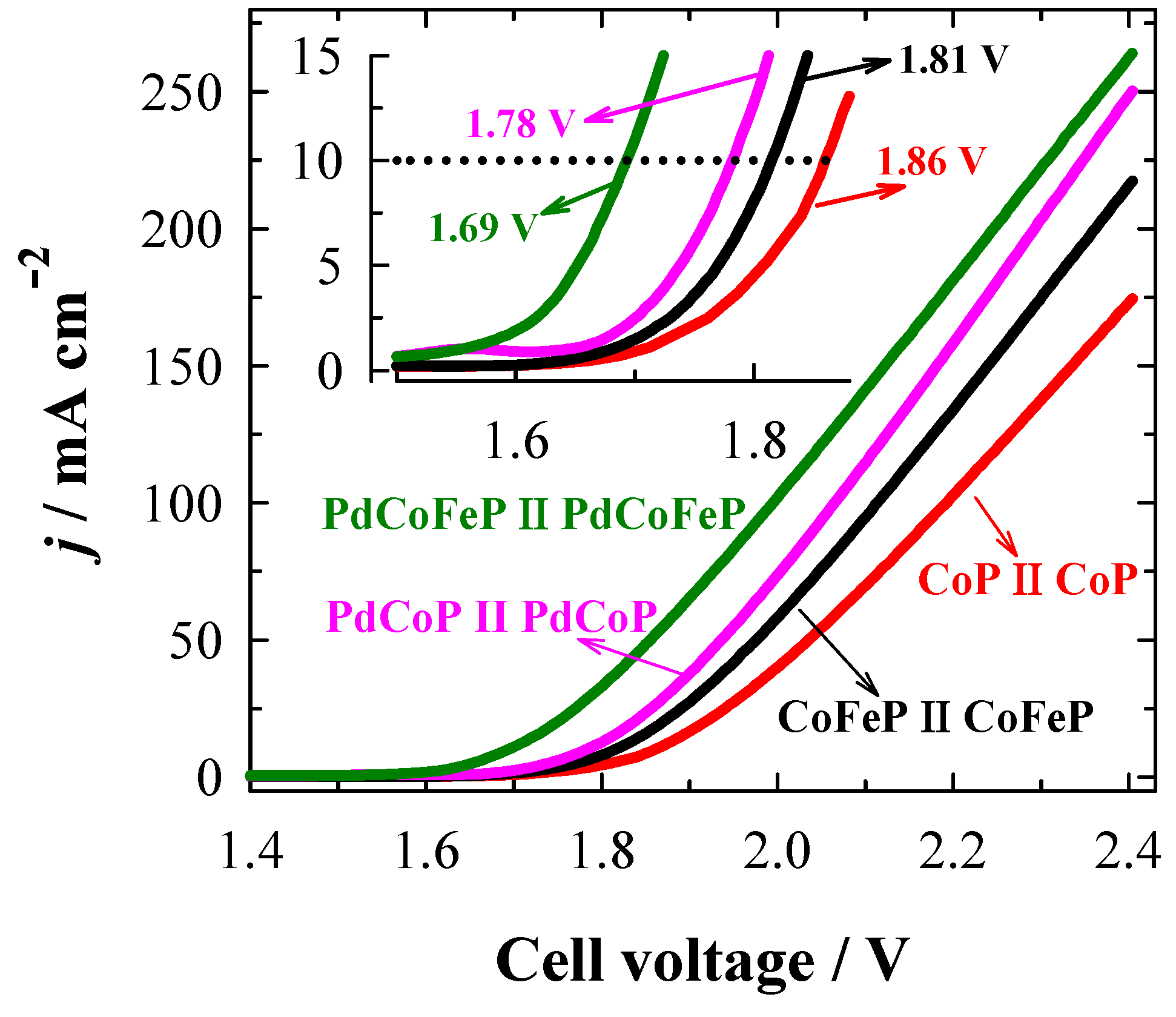

2.6. Investigation of Overall Water Splitting

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Reagents

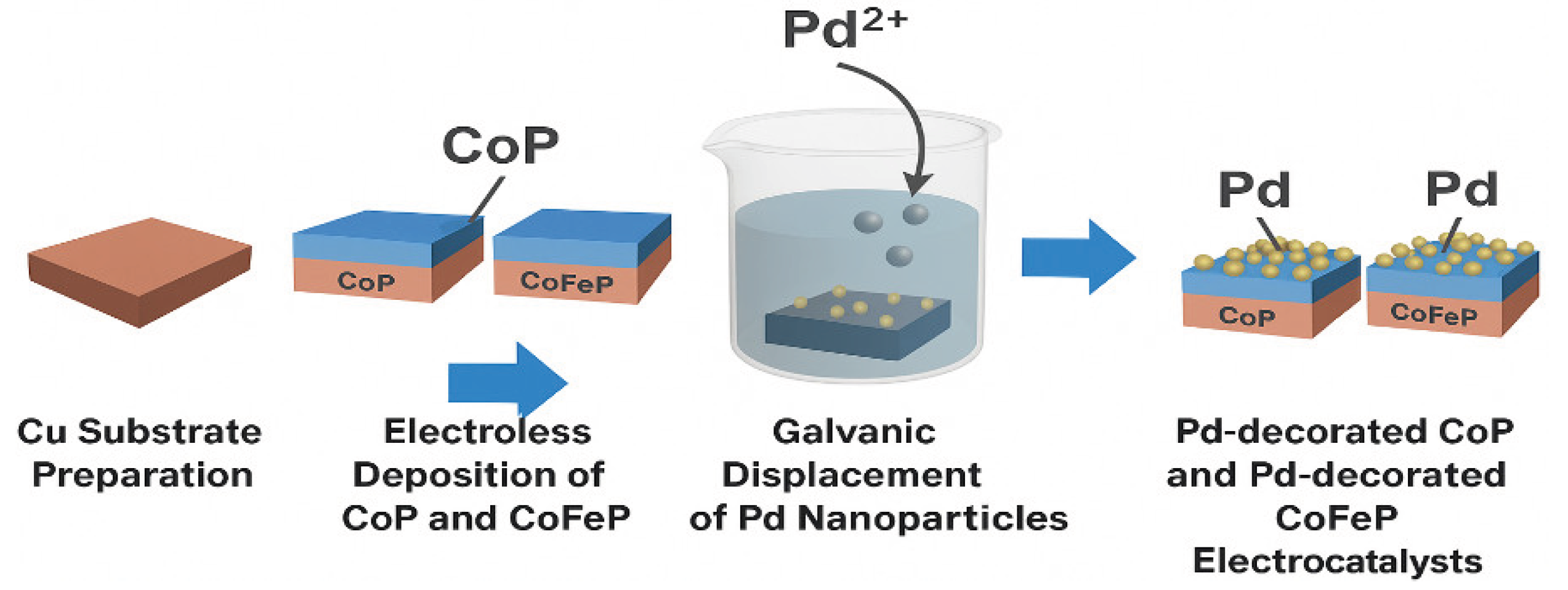

3.2. Preparation of Catalysts

3.3. Characterization of Catalysts

3.4. Evaluation of Catalysts Activity for HER and OER

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Wei, Z.; Dong, C.L.; Ma, J.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Filling the oxygen vacancies in Co3O4 with phosphorus: an ultra-efficient electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, W.; Liu, Q.; Xing, Z.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Recent progress in cobalt-based heterogeneous catalysts for electrochemical water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; He, P.; Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; He, M.; Jia, L.; et al. Facile one-step fabrication of bimetallic Co–Ni–P hollow nanospheres anchored on reduced graphene oxide as highly efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 24140–24150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilavachi, P.A.; Chatzipanagi, A.I.; Spyropoulou, A.I. Evaluation of hydrogen production methods using the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 5294–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Oh, S.; Cho, E.; Kwon, H. 3D porous cobalt–iron–phosphorus bifunctional electrocatalyst for the oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Engineer. 2018, 6, 6305–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balat, M. Potential importance of hydrogen as a future solution to environmental and transportation problems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4013–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7 Wang, S.; He, P.; Jia, L.; He, M.; Zhang, T.; Dong, F.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Nanocoral-like composite of nickel selenide nanoparticles anchored on two-dimensional multi-layered graphitic carbon nitride: a highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 243, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, X.; Huo, J.; Wang, S. Nanoparticle-stacked porous nickel–iron nitride nanosheet: a highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2016, 8, 18652–18657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, H.; Lv, L.; Han, L.; Zhang, Z. Self-supported porous NiSe2 nanowrinkles as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Engineer. 2018, 6, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yu, L.; Mishra, I.K.; Yu, Y.; Ren, Z.F.; Zhou, H.Q. Recent developments in earth-abundant and non-noble electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Mater. Today Phys. 2018, 7, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, X.; Kim, H.; Jung, W.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Electrochemical water splitting: Bridging the gaps between fundamental research and industrial applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, R. Advanced transition metal-based OER electrocatalysts: current status, opportunities, and challenges. Small 2021, 17, 2100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, N.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.W.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.J. Electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution in alkaline electrolytes: mechanisms, challenges, and prospective solutions. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, R.; Wang, S. Defect engineering of cobalt-based materials for electrocatalytic water splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 2018, 6, 15954–15969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Tang, M.T.; Tsai, C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Zheng, X.; Li, H. Enhancing electrocatalytic water splitting by strain engineering. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wei, Y.; Ren, X.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Asiri, A.M.; Wei, Q.; Sun, X. Co (OH)2 nanoparticle-encapsulating conductive nanowires array: room-temperature electrochemical preparation for high-performance water oxidation electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xie, L.; Liu, Z.; Du, G.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. A Zn-doped Ni3 S2 nanosheet array as a high-performance electrochemical water oxidation catalyst in alkaline solution. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12446–12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; You, B.; Sheng, M.; Sun, Y. Electrodeposited cobalt-phosphorous-derived films as competent bifunctional catalysts for overall water splitting. Angew. Chemie 2015, 127, 6349–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liang, C.; Lin, Z. Hierarchical NiCo2O4 hollow microcuboids as bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water-splitting. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6290–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, T.; Ye, Y.Q.; Wu, C.Y.; Xiao, K.; Liu, Z.Q. Heterostructures composed of N-doped carbon nanotubes encapsulating cobalt and β-Mo2C nanoparticles as bifunctional electrodes for water splitting. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4923–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yu, L.; Mishra, I.K.; Yu, Y.; Ren, Z.F.; Zhou, H.Q. Recent developments in earth-abundant and non-noble electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Mater. Today Phys. 2018, 7, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shang, X.; Ren, H.; Chi, J.; Fu, H.; Dong, B.; Liu, C.; Chai, Y. Modulation of inverse spinel Fe3O4 by phosphorus doping as an industrially promising electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1905107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, D.V.; Hunt, S.T.; Stottlemyer, A.L.; Dobson, K.D.; McCandless, B.E.; Birkmire, R.W.; Chen, J.G. Low-cost hydrogen-evolution catalysts based on monolayer platinum on tungsten monocarbide substrates. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2010, 51, 9859–9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Bao, S.; Wang, M.; Qi, X.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, H. Solution-phase epitaxial growth of noble metal nanostructures on dispersible single-layer molybdenum disulfide nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voiry, D.; Yamaguchi, H.; Li, J.; Silva, R.; Alves, D.C.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Asefa, T.; Shenoy, V.B.; Eda, G.; et al. Enhanced catalytic activity in strained chemically exfoliated WS2 nanosheets for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 850−855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, G.; Yang, T.; Yang, S.; Yang, S. Electrochemically modifying the electronic structure of IrO2 nanoparticles for overall electrochemical water splitting with extensive adaptability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qi, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Cui, X. Engineering Pt/Pd interfacial electronic structures for highly efficient hydrogen evolution and alcohol oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2017, 9, 18008–18014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsanzimana, J.M.V.; Peng, Y.; Xu, Y.Y.; Thia, L.; Wang, C.; Xia, B.Y.; Wang, X. An efficient and earth-abundant oxygen-evolving electrocatalyst based on amorphous metal borides. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Xie, J.Y.; Dong, B.; Chi, J.Q.; Guo, B.Y.; Yang, M.; Chai, Y.M.; Liu, C.G. Double-catalytic-site engineering of nickel-based electrocatalysts by group VB metals doping coupling with in-situ cathodic activation for hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 258, 117984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.F.; Liang, Q.; Dangol, R.; Zhao, J.; Ren, H.; Madhavi, S.; Yan, Q. Layered trichalcogenidophosphate: a new catalyst family for water splitting. Nano-micro Lett. 2018, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaj, S.; Ede, S.R.; Sakthikumar, K.; Karthick, K.; Mishra, S.; Kundu, S. Recent trends and perspectives in electrochemical water splitting with an emphasis on sulfide, selenide, and phosphide catalysts of Fe, Co, and Ni: a review. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 8069–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Sviripa, A.; Liang, J.; Han, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, G. Amorphous Co–Fe–P nanospheres for efficient water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, pp–25378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.R.; Cao, X.; Gao, Q.; Xu, Y.F.; Zheng, Y.R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, S.H. Nitrogen-doped graphene supported CoSe2 nanobelt composite catalyst for efficient water oxidation. ACS nano 2014, 8, 3970–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa, J.; Barwe, S.; Andronescu, C.; Sinev, I.; Ruff, A.; Jayaramulu, K.; Elumeeva, K.; Konkena, B.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Schuhmann, W. Low overpotential water splitting using cobalt–cobalt phosphide nanoparticles supported on nickel foam. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, pp.1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, P.; Li, X.; Tong, Y.; Ding, H.; Wu, X.; Chu, W.; Peng, Z.; Wu, C.; Xie, Y. Metallic nickel nitride nanosheets realizing enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, pp.4119–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, L.A.; Feng, L.; Song, F.; Hu, X. Ni2P as a Janus catalyst for water splitting: the oxygen evolution activity of Ni2P nanoparticles. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2347–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa, J.; Weide, P.; Peeters, D.; Sinev, I.; Xia, W.; Sun, Z.; Somsen, C.; Muhler, M.; Schuhmann, W. Amorphous cobalt boride (Co2B) as a highly efficient nonprecious catalyst for electrochemical water splitting: oxygen and hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, p.1502313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Fu, S.; Qin, F.; Zuo, P.; Shen, W. Urchin-like bifunctional CoP/FeP electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 93, pp.147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Li, C.; Pham, B.T.; Zhang, D. Electrodeposition of Ni–Fe–Mn ternary nanosheets as affordable and efficient electrocatalyst for both hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 24670–24683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, D.; Ye, F.; Wang, K.; Shi, Z. Synthesis of lawn-like NiS2 nanowires on carbon fiber paper as bifunctional electrodes for water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 17038–17048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhu, G.; Mao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ju, S.; Shen, X.; Pang, H. Small sized Fe–Co sulfide nanoclusters anchored on carbon for oxygen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, pp.15851–15861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Fang, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Tian, M.; Jin, J.; et al. Synthesis of Cu–MoS2/rGO hybrid as non-noble metal electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources 2015, 292, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Patel, N.; Fernandes, R.; Kadrekar, R.; Dashora, A.; Yadav, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Jha, S.N.; Miotello, A.; Kothari, D.C. Co–Ni–B nanocatalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction in wide pH range. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2016, 192, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xie, Y.; Wu, J.X.; Huang, H.; Teng, J.; Wang, D.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, J.J.; Wang, H.P.; Su, C.Y. Cobalt (oxy) hydroxide nanosheet arrays with exceptional porosity and rich defects as a highly efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalyst under neutral conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, pp.10217–10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, P.; Lokhande, A.; Shin, H.H.; Pawar, B.; Gang, M.G.; Pawar, S.; Kim, J.H. Cobalt iron hydroxide as a precious metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for efficient overall water splitting. Small 2018, 14, 1702568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Dang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Jin, S. Amorphous cobalt–iron hydroxide nanosheet electrocatalyst for efficient electrochemical and photo-electrochemical oxygen evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, p.1603904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; She, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Yao, X. Boosting hydrogen evolution via optimized hydrogen adsorption at the interface of CoP3 and Ni2P. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, pp.5560–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Suito, R.; Menezes, P.W. , & Driess, M. Amorphous outperforms crystalline nanomaterials: surface modifications of molecularly derived CoP electro (pre) catalysts for efficient water-splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15749–15756. [Google Scholar]

- Amber, H.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Sukackienė, Z.; Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūnaitė, L.; Norkus, E. Electrolessly deposited cobalt–phosphorus coatings for efficient hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Catalysts 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Feng, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X. MOF-derived cobalt phosphide as highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 892, 115300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.Y.; Kwak, I.H.; Lim, Y.R.; Park, J. FeP and FeP 2 nanowires for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 2819–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Dong, B.; Yu, X.; Xue, H.; Feng, L. A FeP powder electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 92, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Liu, Q.; Sun, X. NiP2 nanosheet arrays supported on carbon cloth: an efficient 3D hydrogen evolution cathode in both acidic and alkaline solutions. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 13440–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; You, B.; Sheng, M.; Sun, Y. Bifunctionality and mechanism of electrodeposited nickel–phosphorous films for efficient overall water splitting. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Du, K.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Shao, Y.; Li, M. Enhanced electrocatalytic activity of MoP microparticles for hydrogen evolution by grinding and electrochemical activation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4368–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, J.; He, L.; Li, D.; Gao, Q. Plasma-Engineered MoP with nitrogen doping: Electron localization toward efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2020, 268, 118441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Bao, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Ai, T.; Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Jiang, P.; Kou, L. Interfacial interaction between NiMoP and NiFe-LDH to regulate the electronic structure toward high-efficiency electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, pp.9230–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Rodriguez, J.A. Catalysts for hydrogen evolution from the [NiFe] hydrogenase to the Ni2P (001) surface: the importance of ensemble effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14871–14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisomboonchai, S.; Kitiphatpiboon, N.; Chen, M.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Kongparakul, S.; Samart, C.; Zhang, L.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Multi-hierarchical porous Mn-doped CoP catalyst on nickel phosphide foam for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 5, pp.149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Wu, D.; Cheng, D.; Cao, D. Vertical CoP nanoarray wrapped by N, P-doped carbon for hydrogen evolution reaction in both acidic and alkaline conditions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, p.1803970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tian, J.; Cui, W.; Jiang, P.; Cheng, N.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Carbon nanotubes decorated with CoP nanocrystals: a highly active non-noble-metal nanohybrid electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6710–6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Yu, L.; McElhenny, B.; Xing, X.; Luo, D.; Zhang, F.; Bao, J.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Rational design of core-shell-structured CoPx@ FeOOH for efficient seawater electrolysis. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 294, p.120256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; He, T.; Zhou, W.; Deng, R.; Zhang, Q. Iron-tuned 3D cobalt–phosphate catalysts for efficient hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions over a wide pH range. ACS Sustain. Chem. Engineer. 2020, 8, 13793–13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.S.; Zhang, L.M.; Dong, Y.W.; Zhang, J.Q.; Yan, X.T.; Sun, D.F.; Shang, X.; Chi, J.Q.; Chai, Y.M.; Dong, B. Tungsten-doped Ni–Co phosphides with multiple catalytic sites as efficient electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, pp.16859–16866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthurasu, A.; Ojha, G.P.; Lee, M.; Kim, H.Y. Integration of cobalt metal–organic frameworks into an interpenetrated prussian blue analogue to derive dual metal–organic framework-assisted cobalt iron derivatives for enhancing electrochemical total water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 14465–14476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yan, D.; Nie, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wang, S.; Yuan, J.; Su, D.; Wang, G.; Wu, Z. Iron-doped NiCoP porous nanosheet arrays as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, pp.571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Gan, L.; Zhang, R.; Lu, W.; Jiang, X.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, L. Ternary FexCo1–x P nanowire array as a robust hydrogen evolution reaction electrocatalyst with Pt-like activity: experimental and theoretical insight. Nano letters 2016, 16, pp.6617–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, S.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Dong, H. Recent research progress of bimetallic phosphides-based nanomaterials as cocatalyst for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, Q.; Shen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, C. Fabrication of 3D microporous amorphous metallic phosphides for high-efficiency hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 306, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, B. Recent advances in transition metal phosphide nanomaterials: synthesis and applications in hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wei, W.; Ni, B.J. Cost-effective catalysts for renewable hydrogen production via electrochemical water splitting: Recent advances. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 27, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Moon, J.; Jeong, K.; Cho, G. Application of PU-sealing into Cu/Ni electroless plated polyester fabrics for e-textiles. Fiber. Polym. 2007, 8, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, A.; Zhang, J. Aluminum-induced direct electroless deposition of Co and Co-P coatings on copper and their catalytic performance for electrochemical water splitting. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 352, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Chuang, C.C.; Li, X.H.; Chin, T.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Sung, C.K.; Wang, S.C. Ultrasound-assisted electroless deposition of Co-P hard magnetic films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 388, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, A.; Zhang, J. Aluminum-induced direct electroless deposition of Co and Co-P coatings on copper and their catalytic performance for electrochemical water splitting. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 352, 42−48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qu, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, B. Bimetallic CoFeP hollow microspheres as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting in alkaline media. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 816−823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, R.; Pervaiz, E.; Baig, M.M.; Rabi, O. Three-dimensional hierarchical flowers-like cobalt-nickel sulfide constructed on graphitic carbon nitride: Bifunctional non-noble electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 418, 140346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Huo, L.; Zhao, H. Interface electronic coupling in hierarchical FeLDH(FeCo)/Co(OH)2 arrays for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3592–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotochaud, L.; Ranney, J.K.; Williams, K.N.; Boettcher, S.W. Solution-cast metal oxide thin film electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17253–17261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Shi, N.E.; Zhao, S.; Xu, D.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.J.; Dai, Z.; Lan, Y.Q.; Han, M.; Bao, J. Coralloid Co2P2O7 nanocrystals encapsulated by thin carbon shells for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2016, 8, 22534–22544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, J. Cobalt phosphide hollow polyhedron as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for the evolution reaction of hydrogen and oxygen. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, K.; Da, P.; Peng, Z.; Tang, J.; Kong, B.; Cai, W.B.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, G. Reduced mesoporous Co3O4 nanowires as efficient water oxidation electrocatalysts and supercapacitor electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4, 1400696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.P.; Liu, Y.P.; Ren, T.Z.; Yuan, Z.Y. Self-supported cobalt phosphide mesoporous nanorod arrays: A flexible and bifunctional electrode for highly active electrocatalytic water reduction and oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 7337–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Y.; Dong, X.; Meng, C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y. Phosphate-modified cobalt silicate hydroxide with improved oxygen evolution reaction. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 648, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Fei, H.; Ruan, G.; Tour, J.M. Porous cobalt-based thin film as a bifunctional catalyst for hydrogen generation and oxygen generation. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3175–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ran, N.; Ge, R.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Feng, L.; Che, R. Porous Mn-doped cobalt phosphide nanosheets as highly active electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 131642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liang, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.Q.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, H.; Xie, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, N.; et al. Co2P/CoP hybrid as a reversible electrocatalyst for hydrogen oxidation/evolution reactions in alkaline medium; J. Catal. 2020, 390, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Asiri, A.M.; Luo, Y.; Sun, X. Electrodeposited Ni-P alloy nanoparticle films for efficiently catalyzing hydrogen- and oxygen-evolution reactions. ChemNanoMat 2015, 1, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Yan, H.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Sun, D.; Xu, X. The defect-rich porous CoP4/Co4S3 microcubes as robust electrocatalyst for clean H2 energy production via alkaline overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2023, 668, 119461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, C.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Carbon n+anodots modified cobalt phosphate as efficient electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J. Mater. 2015, 1, 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Zhou, Y.X.; Jiang, H.L. Metal-organic framework-based CoP/reduced graphene oxide: High-performance bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Wu, J.; Li, X.-B.; Luo, J.; Lau, W.-M.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.-L.; Liu, L.-M. A highly stable bifunctional catalyst based on 3D Co(OH)2@NCNTs@NF towards overall water-splitting. Nano Energy 2018, 47, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, J.; You, B.; Sun, Y. Competent overall water-splitting electrocatalysts derived from ZIF-67 grown on carbon cloth. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 73336–73342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyitanga, T.; Kim, H. Time-dependent oxidation of graphite and cobalt oxide nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 914, 116297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C. Ru-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction: Recent research advances and perspectives. Mater. Today Phys. 2020, 15, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossar, E.; Houache, M.S.E.; Zhang, Z.; Baranova, E.A. Comparison of electrochemical active surface area methods for various nickel nanostructures. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 870, 114246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Element, at% | |||

| Pd | Co | Fe | P | |

| CoP/Cu | - | 90.22 | - | 9.78 |

| CoFeP/Cu | - | 83.78 | 9.96 | 6.26 |

| PdCoP/Cu | 3.54 | 83.72 | - | 12.74 |

| PdCoFeP/Cu | 8.36 | 64.08 | 12.49 | 15.07 |

| Sample | Eonset*, V | η10**, mV |

Tafel slope, mV dec−1 |

Ea, kJ mol−1 |

| CoP/Cu | 0.166 | 239 | 78.1 | 11.3 |

| CoFeP/Cu | 0.188 | 245 | 76.4 | 6.0 |

| PdCoP/Cu | 0.171 | 250 | 76.3 | 4.7 |

| PdCoFeP/Cu | 0.213 | 259 | 82.8 | 11.4 |

| Sample | Eonset*, V | ηonset, mV | E**, V | η10**, mV |

Tafel slope, mV dec−1 |

Ea, kJ mol−1 |

| CoP/Cu | 1.5205 | 290 | 1.6607 | 431 | 120.3 | 20.7 |

| CoFeP/Cu | 1.5846 | 355 | 1.6650 | 435 | 74.5 | 21.2 |

| PdCoP/Cu | 1.5426 | 313 | 1.6255 | 396 | 77.8 | 12.2 |

| PdCoFeP/Cu | 1.5577 | 328 | 1.6256 | 396 | 70.5 | 11.8 |

| Catalyst | η10*, mV |

Tafel slope, mV dec−1 |

Electrolyte | Ref. |

| PdCoFeP/Cu | 396 | 70.5 | 1 M KOH | This study |

| PdCoP/Cu | 396 | 77.8 | 1 M KOH | This study |

| CoOx | 423 | 42 | 1 M KOH | [79] |

| Co2P2O7 | 490 | 86 | 1 M KOH | [80] |

| Co(PO3)2 nanosheets | 574 | 106 | 1 M KOH | [80] |

| CoP hollow polyhedron | 400 | 57 | 1 M KOH | [81] |

| Reduced mesoporous Co3O4 nanowires | 400 | 72 | 1 M KOH | [82] |

| CoP-MNA/Ni foam | 390 | 65 | 1 M KOH | [83] |

| CoP | 350 | 47 | 1 M KOH | [18] |

| CoSi-P | 309 | 121 | 1 M KOH | [84] |

| CoP | 300 | 65 | 1 M KOH | [85] |

| Mn-CoP | 288 | 77.2 | 1 M KOH | [86] |

| RuO2/CF | 360 | 164 | 1 M KOH | [87] |

| RuO2 on NF | 290 | 81 | 1 M KOH | [88] |

| IrO2 commercial | 339 | 94.5 | 1 M KOH | [89] |

| Ir/C | 254 | 71.9 | 1 M KOH | [90] |

| Anode II Cathode | Cell voltage, V | Electrolyte | Ref. |

| PdCoFeP/Cu‖PdCoFeP/Cu | 1.69 | 1 M KOH | This study |

| PdCoP/Cu‖PdCoP/Cu | 1.78 | 1 M KOH | This study |

| Pt/C‖IrO2 | 1.71 | 1 M KOH | [91] |

| Pt/C‖Pt/C | 1.83 | 1 M KOH | [91] |

| CoP/rGO-400‖CoP/rGO-400 | 1.70 | 1 M KOH | [91] |

| Co(OH)2@NCNTs@NF‖ Co(OH)2@NCNTs@NF | 1.72 | 1 M KOH | [92] |

| Co-P/NC/CC‖Co-P/NC/CC | 1.77 | 1 M KOH | [93] |

| Co-P/NC-CC‖Co-P/NC-CC | 1.95 | 1 M KOH | [93] |

| Sample | Composition of the plating bath, mol L–1 | T, oC | t, min | pH | |||

| CoSO4 | FeSO4 | Glycine | NaH2PO2 | ||||

| CoP | 0.1 | - | 0.6 | 0.75 | 60 | 30 | 11 |

| CoFeP | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.75 | 60 | 30 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).