Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Patient Characteristics

The Purposes and Calculation of Prognostic Markers

Lymphocyte-Related Inflammation Markers (NLR, PLR, LMR, CLR, SII, SIRI)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TC | Testicular cancer | |

| NSGCT | Nonseminomatous germ cell carcinoma | |

| PFT | Pulmonary function test | |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage | |

| DLCO | Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity | |

| NLR | Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | |

| PLR | Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | |

| LMR | Lymphocyte/monocyte ratio | |

| CLR | CRP/lymphocyte ratio | |

| SII | Systemic immune inflammation score | |

| SIRI | Systemic inflammation response index | |

| mGCT | Mixed germ cell tumor | |

| mOS | Median overall survival | |

| GCSF | Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor | |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity | |

| TLC | Total lung capacity | |

| BEP | Bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin | |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute | |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals | |

| TLA | Three letter acronym | |

| LD | Linear dichroism | |

References

- Ozkan M.; Dweik R.A.; Ahmad M. Drug-induced lung disease. Cleve clin j med. 2001; 68, 782-785, 789-795. https://doi:10.3949/ccjm.68.9.782.

- Nebeker J.R.; Barach P.; Samore M.H. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician's guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting. Ann intern med. 2004; 140, 795-801. [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann K.P.; Richter-Simonsen H.; Kulejewski M.; Ikogho R.; Zecha H.; Anheuser P.; Pichlmeier U.; Isbarn H. Testicular Germ-Cell Tumours: A Descriptive Analysis of Clinical Characteristics at First Presentation. Urol int. 2018; 100, 09-419. [CrossRef]

- Shah Y.B.; Goldberg H.; Hu B.; Daneshmand S.; Chandrasekar T. Metastatic Testicular Cancer Patterns and Predictors: A Contemporary Population-based SEER Analysis. Urology. 2023; 180, 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Haugnes H.S.; Aass N.; Fosså S.D.; Dahl O.; Brydøy M.; Aasebø U.; Wilsgaard T.; Bremnes R.M. Pulmonary function in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J clin oncol. 2009; 27, 2779-2786. [CrossRef]

- Lauritsen J.; Kier M.G.; Mortensen M.S.; Bandak M.; Gupta R.; Holm N.V.; Agerbaek M.; Daugaard G. Germ Cell Cancer and Multiple Relapses: Toxicity and survival. j clin oncol. 2015; 33, 3116-3123. [CrossRef]

- Vahid B.; Marik P.E. Pulmonary complications of novel antineoplastic agents for solid tumors. Chest. 2008; 133, 528-538. [CrossRef]

- Limper A.H. Chemotherapy-induced lung disease. Clin chest med. 2004; 25, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Possick J.D. Pulmonary Toxicities from Checkpoint Immunotherapy for Malignancy. Clin Chest Med. 2017; 38, 223-232. [CrossRef]

- Sleijfer S. Bleomycin-induced pneumonitis. Chest. 2001; 120, 617-624. [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmi R.; Kramer M.R.; Rizel S.; Sulkes A.; Gelmon K.; Granot T.; Neiman V.; Stemmer S.M. Decline in pulmonary function in patients with breast cancer receiving dose-dense chemotherapy: A prospective study. Ann oncol. 2009; 20, 437-440. [CrossRef]

- Camus P.; Bonniaud P.; Fanton A.; Camus C.; Baudaun N.; Foucher P. Drug-induced and iatrogenic infiltrative lung disease. Clin chest med. 2004; 25, 479-519. https://doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2004.05.006.

- Schrier D.J.; Phan S.H.; McGarry B.M. The effects of the nude (nu/nu) mutation on bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. A biochemical evaluation. Am rev respir dis. 1983; 127, 614-617. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka R.; Hayashi H.; Uesato M.; Hayano K.; Murakami K.; Toyozumi T.; Matsumoto Y.; Kurata Y.; Nakano A.; Takahashi Y.; Arasawa T.; Matsubara H. Inflammatory and Nutritional Indices as Prognostic Markers in Elderly Patients With Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2023; 43, 5261-5267. [CrossRef]

- Ruan G.T.; Xie H.L.; Yuan K.T.; Lin S.Q.; Zhang H.Y.; Liu C.A.; Shi J.Y.; Ge Y.Z.; Song M.M.; Hu C.L.; Zhang X.W.; Liu X.Y.; Yang M.; Wang K.H.; Zheng X.; Chen Y.; Hu W.; Cong M.H.; Zhu L.C.; Deng L.; Shi H.P.; Prognostic value of systemic inflammation and for patients with colorectal cancer cachexia. J cachexia sarcopenia muscle. 2023; 14, 2813-2823. [CrossRef]

- Nøst T.H.; Alcala K.; Urbarova I.; Byrne K.S.; Guida F.; Sandanger T.M.; Johansson M. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur j epidemiol. 2021; 36, 841-848. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S.; Cheng T. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann med. 2024; 56, 2337729. [CrossRef]

- Blumenschein G.R. Jr.; Gatzemeier U.; Fossella F.; Stewart D.J.; Cupit L.; Cihon F.; O'Leary J.; Reck M. Phase II, multicenter, uncontrolled trial of single-agent sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J clin oncol. 2009; 27, 4274-4280. [CrossRef]

- Nicolls M.R.; Terada L.S.; Tuder R.M.; Prindiville S.A.; Schwarz M.I. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage with underlying pulmonary capillaritis in the retinoic acid syndrome. Am j respir crit care med. 1998; 158, 1302-1305. [CrossRef]

- Lee C.; Gianos M.; Klaustermeyer W.B. Diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity reactions related to common cancer chemotherapy agents. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009; 102, 179-187. [CrossRef]

- Meadors M.; Floyd J.; Perry M.C. Pulmonary toxicity of chemotherapy. Semin oncol. 2006; 33, 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Jules-Elysee K.; White D.A. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity. Clin chest med. 1990; 11, 1-20.

- O'Sullivan J.M.; Huddart R.A.; Norman A.R.; Nicholls J.; Dearnaley D.P.; Horwich A. Predicting the risk of bleomycin lung toxicity in patients with germ-cell tumours. Ann oncol. 2003; 14, 91-96. [CrossRef]

- Lazo J.S.; Merrill W.W.; Pham E.T.; Lynch T.J.; McCallister J.D.; Ingbar D.H. Bleomycin hydrolase activity in pulmonary cells. J pharmacol exp ther. 1984; 231, 583-588.

- Martin W.G.; Ristow K.M.; Habermann T.M.; Colgan J.P.; Witzig T.E.; Ansell S.M. Bleomycin pulmonary toxicity has a negative impact on the outcome of patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma. J clin oncol. 2005; 23, 7614-7620. [CrossRef]

- Stamatoullas A.; Brice P.; Bouabdallah R.; Mareschal S.; Camus V.; Rahal I.; Franchi P.; Lanic H.; Tilly H. Outcome of patients older than 60 years with classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with front line ABVD chemotherapy: frequent pulmonary events suggest limiting the use of bleomycin in the elderly. Br j haematol. 2015; 170-184. [CrossRef]

- Fosså S.D.; Kaye S.B.; Mead G.M.; Cullen M.; de Wit R.; Bodrogi I.; van Groeningen C.J.; De Mulder P.H.; Stenning S.; Lallemand E.; De Prijck L.; Collette L. Filgrastim during combination chemotherapy of patients with poor-prognosis metastatic germ cell malignancy. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Genito-Urinary Group, and the Medical Research Council Testicular Cancer Working Party, Cambridge, United Kingdom. j clin oncol. 1998; 16, 716-724. [CrossRef]

- Saxman S.B.; Nichols C.R.; Einhorn L.H. Pulmonary toxicity in patients with advanced-stage germ cell tumors receiving bleomycin with and without granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Chest. 1997; 111, 657-660. [CrossRef]

- Evens A.M.; Cilley J.; Ortiz T.; Gounder M.; Hou N.; Rademaker A.; Miyata S.; Catsaros K.; Augustyniak C.; Bennett C.L.; Tallman M.S.; Variakojis D.; Winter J.N.; Gordon L.I. G-CSF is not necessary to maintain over 99% dose-intensity with ABVD in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma: low toxicity and excellent outcomes in a 10-year analysis. Br j haematol. 2007; 137, 545-552. [CrossRef]

- Nichols C.R.; Catalano P.J.; Crawford E.D.; Vogelzang N.J.; Einhorn L.H.; Loehrer P.J. Randomized comparison of cisplatin and etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in treatment of advanced disseminated germ cell tumors: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J clin oncol. 1998; 16, 1287-1293. [CrossRef]

- Lauritsen J.; Kier M.G.; Bandak M.; Mortensen M.S.; Thomsen F.B.; Mortensen J.; Daugaard G. Pulmonary Function in Patients With Germ Cell Cancer Treated With Bleomycin, Etoposide, and Cisplatin. J clin oncol. 2016; 34, 1492-1499. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary U.B.; Haldas J.R. Long-term complications of chemotherapy for germ cell tumours. Drugs. 2003; 63, 1565-1577. [CrossRef]

- Lower E.E.; Strohofer S.; Baughman R.P. Bleomycin causes alveolar macrophages from cigarette smokers to release hydrogen peroxide. Am j med sci. 1988; 295, 193-197. [CrossRef]

- Thomas T.S.; Luo S.; Reagan P.M.; Keller J.W.; Sanfilippo K.M.; Carson K.R. Advancing age and the risk of bleomycin pulmonary toxicity in a largely older cohort of patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin Lymphoma. J geriatr oncol. 2020; 11, 69-74. [CrossRef]

- Simpson A.B.; Paul J.; Graham J.; Kaye S.B. Fatal bleomycin pulmonary toxicity in the west of Scotland 1991-95: a review of patients with germ cell tumours. Br j cancer. 1998; 78, 1061-1066. [CrossRef]

- Uzel I.; Ozguroglu M.; Uzel B.; Kaynak K.; Demirhan O.; Akman C.; Oz F.; Yaman M. Delayed onset bleomycin-induced pneumonitis. Urology. 2005; 66, 195. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou I.; Efstathiou E.; Samakovli A.; Dafni U.; Moulopoulos L.A.; Papadimitriou C.; Lyberopoulos P.; Kastritis E.; Roussos C.; Dimopoulos M.A. A prospective study on lung toxicity in patients treated with gemcitabine and carboplatin: clinical, radiological and functional assessment. Ann oncol. 2004; 15, 1250-1255. [CrossRef]

- Rivera M.P.; Detterbeck F.C.; Socinski M.A.; Moore D.T.; Edelman M.J.; Jahan T.M.; Ansari R.H.; Luketich J.D.; Peng G.; Monberg M.; Obasaju C.K.; Gralla R.J. Impact of preoperative chemotherapy on pulmonary function tests in resectable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2009; 135, 1588-1595. [CrossRef]

- Buchler T.; Bomanji J.; Lee S.M. FDG-PET in bleomycin-induced pneumonitis following ABVD chemotherapy for Hodgkin's disease--a useful tool for monitoring pulmonary toxicity and disease activity. Haematologica. 2007; 92, 120-121. [CrossRef]

- von Rohr L.; Klaeser B.; Joerger M.; Kluckert T.; Cerny T.; Gillessen S. Increased pulmonary FDG uptake in bleomycin-associated pneumonitis. Onkologie. 2007; 30, 320-323. [CrossRef]

- Cleverley J.R.; Screaton N.J.; Hiorns M.P.; Flint J.D.; Müller N.L. Drug-induced lung disease: high-resolution CT and histological findings. Clin radiol. 2002; 57, 292-299. [CrossRef]

- Torrisi J.M.; Schwartz L.H.; Gollub M.J.; Ginsberg M.S.; Bosl G.J.; Hricak H. CT findings of chemotherapy-induced toxicity: what radiologists need to know about the clinical and radiologic manifestations of chemotherapy toxicity. Radiology. 2011; 258, 41-56. [CrossRef]

- Sikdar T.; MacVicar D.; Husband J.E. Pneumomediastinum complicating bleomycin related lung damage. Br j radiol. 1998; 71, 1202-1204. [CrossRef]

- Bossi G.; Cerveri I.; Volpini E.; Corsico A.; Baio A.; Corbella F.; Klersy C.; Arico M. Long-term pulmonary sequelae after treatment of childhood Hodgkin's disease. Ann oncol. 1997; 19-24.

- Fujimoto D.; Kato R.; Morimoto T.; Shimizu R.; Sato Y.; Kogo M.; Ito J.; Teraoka S.; Nagata K.; Nakagawa A.; Otsuka K.; Tomii K. Characteristics and Prognostic Impact of Pneumonitis during Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS one. 2016; 11, 0168465. [CrossRef]

- Watson R.A.; De La Peña H.; Tsakok M.T.; Joseph J.; Stoneham S.; Shamash J.; Joffe J.; Mazhar D.; Traill Z.; Ho L.P.; Brand S.; Protheroe A.S. Development of a best-practice clinical guideline for the use of bleomycin in the treatment of germ cell tumours in the UK. Br j cancer. 2018; 119, 1044-1051. [CrossRef]

- Comis R.L.; Kuppinger M.S.; Ginsberg S.J.; Crooke S.T.; Gilbert R.; Auchincloss J.H.; Prestayko A.W. Role of single-breath carbon monoxide-diffusing capacity in monitoring the pulmonary effects of bleomycin in germ cell tumor patients. Cancer res. 1979; 39, 5076-5080.

- Pascual R.S.; Mosher M.B.; Sikand R.S.; De Conti R.C.; Bouhuys A. Effects of bleomycin on pulmonary function in man. Am rev respir dis. 1973; 108, 211-217. [CrossRef]

- Villani F.; De Maria P.; Bonfante V.; Viviani S.; Laffranchi A.; Dell'oca I.; Dirusso A.; Zanini M. Late pulmonary toxicity after treatment for Hodgkin's disease. Anticancer res. 1997; 4739-4742.

- McKeage M.J.; Evans B.D.; Atkinson C.; Perez D.; Forgeson G.V.; Dady P.J. Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity is a poor predictor of clinically significant bleomycin lung. New Zealand Clinical Oncology Group. J clin oncol. 1990; 779-783. [CrossRef]

- Ng A.K.; Li S.; Neuberg D.; Chi R.; Fisher D.C.; Silver B.; Mauch P.M. A prospective study of pulmonary function in Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Ann oncol. 2008; 19, 1754-1758. [CrossRef]

- Shamash J.; Sarker S.J.; Huddart R.; Harland S.; Joffe J.K.; Mazhar D.; Birtle A.; White J.; Chowdhury K.; Wilson P.; Marshall M.R.; Vinnicombe S. A randomized phase III study of 72 h infusional versus bolus bleomycin in BEP (bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin) chemotherapy to treat IGCCCG good prognosis metastatic germ cell tumours (TE-3). Ann oncol. 2017; 28, 1333-1338. [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (median±SS) | 32.19±9.62 | 30.79 (15.73-65.33) |

| Age at Diagnosis | 15-29 years | 53 (44.92) |

| 30-39 years | 43 (36.44) | |

| 40-49 years | 15 (12.71) | |

| ≥ 50 years | 7 (5.93) | |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status | 0 | 112 (94.92) |

| 1 | 3 (2.54) | |

| 2 | 1 (0.85) | |

| 3 | 2 (1.69) | |

| Histopathology | Seminoma | 43 (36.44) |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 20 (16.95) | |

| Mixed germ cell carcinoma | 54 (45.76) | |

| Epididymal invasion | No | 112 (94.92) |

| Yes | 6 (5.08) | |

| Tunica albuginea invasion | No | 101 (85.59) |

| Yes | 17 (14.41) | |

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | No | 112 (94.92) |

| Yes | 6 (5.08) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | No | 52 (44.07) |

| Yes | 66 (55.93) | |

| Tumor localization | Right | 56 (47.46) |

| Left | 59 (50) | |

| Bilateral | 3 (2.54) | |

| Diagnostic symptom | Mass | 53 (44.92) |

| Swelling | 35 (29.66) | |

| Pain | 30 (25.42) | |

| Stage | Stage 1 | 69 (58.47) |

| Stage 2 | 29 (24.58) | |

| Stage 3 | 20 (16.95) | |

| Tumor size | 42.61±24.7 | 35 (6-120) |

| Radiotherapy | No | 113 (95.76) |

| Yes | 5 (4.24) | |

| Surgery | No | 4 (3.39) |

| Yes | 114 (96.61) | |

| Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection | No | 86 (72.88) |

| Yes | 32 (27.12) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | No | 19 (16.1) |

| Yes | 99 (83.9) | |

| Number of adjuvant cycles | 2.96±0.94 | 3 (1-6) |

| Pulmonary toxicity | No | 95 (80.51) |

| Yes | 23 (19.49) | |

| Decrease in DLCO in patients with pulmonary toxicity | ≤%10 | 7 (33.33) |

| >%10 | 14 (66.67) | |

| Use of GCSF in Patients Developing Pulmonary Toxicity | No | 10 (45.45) |

| Yes | 12 (54.55) | |

| Progression | No | 93 (78.81) |

| Yes | 25 (21.19) | |

| Living Situation | Alive | 107 (90.68) |

| Exitus | 11 (9.32) | |

| Median overall survival (mOS) | 159,86±4,34(min/max:151,346-168,364) | |

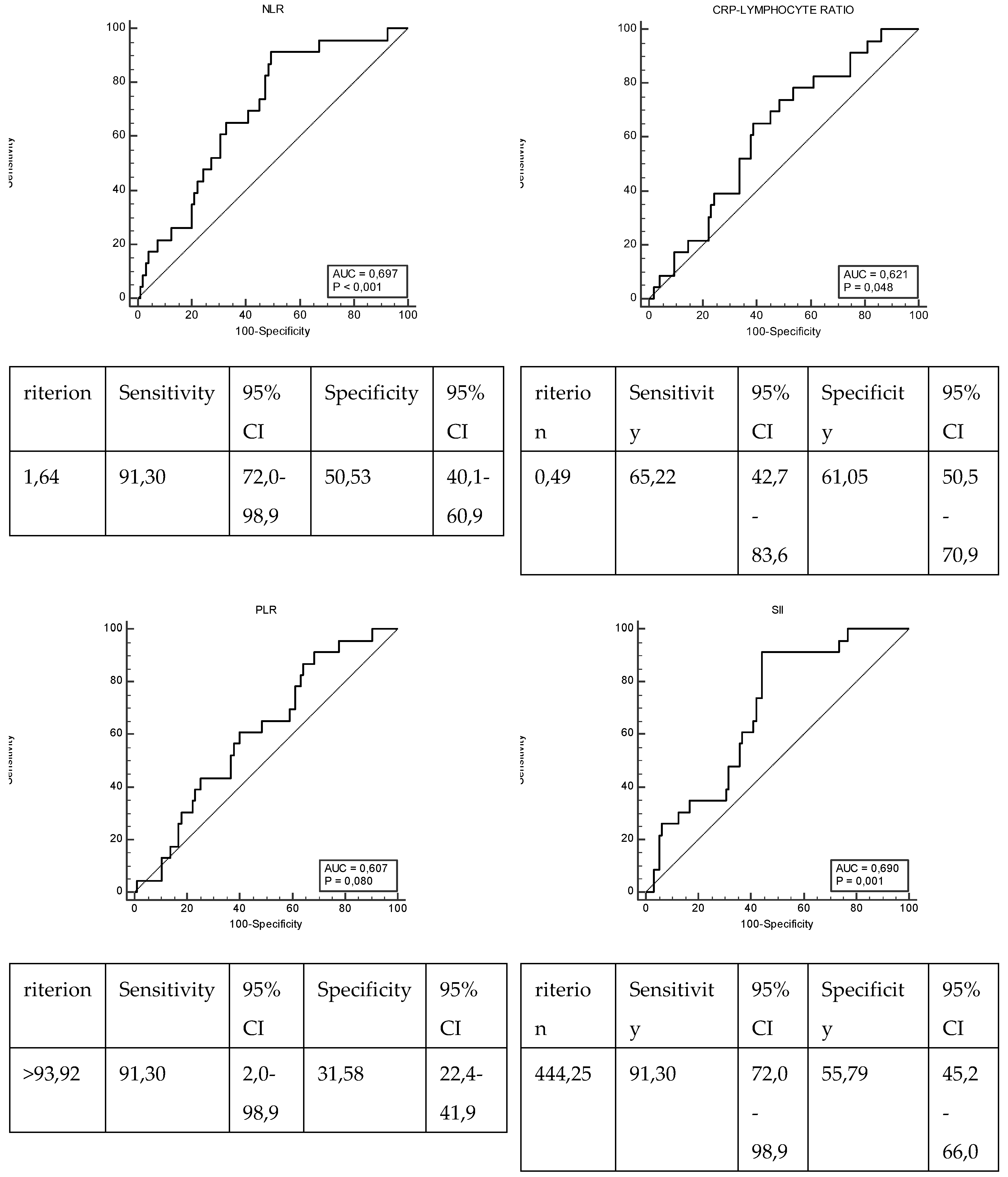

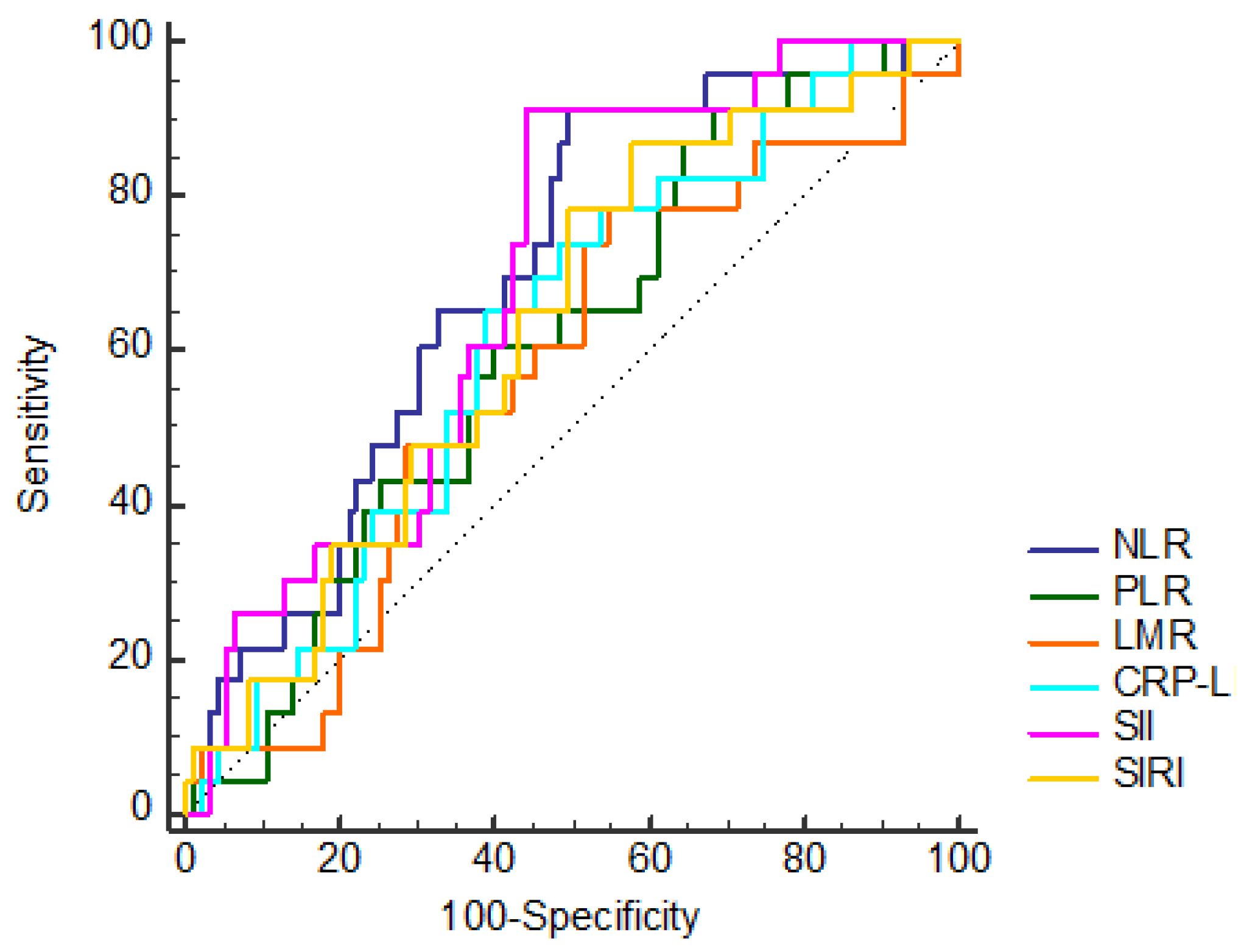

| NLR | ≤1.64 | 50 (42.37) |

| >1.64 | 68 (57.63) | |

| PLR | ≤93.92 | 32 (27.12) |

| >93.92 | 86 (72.88) | |

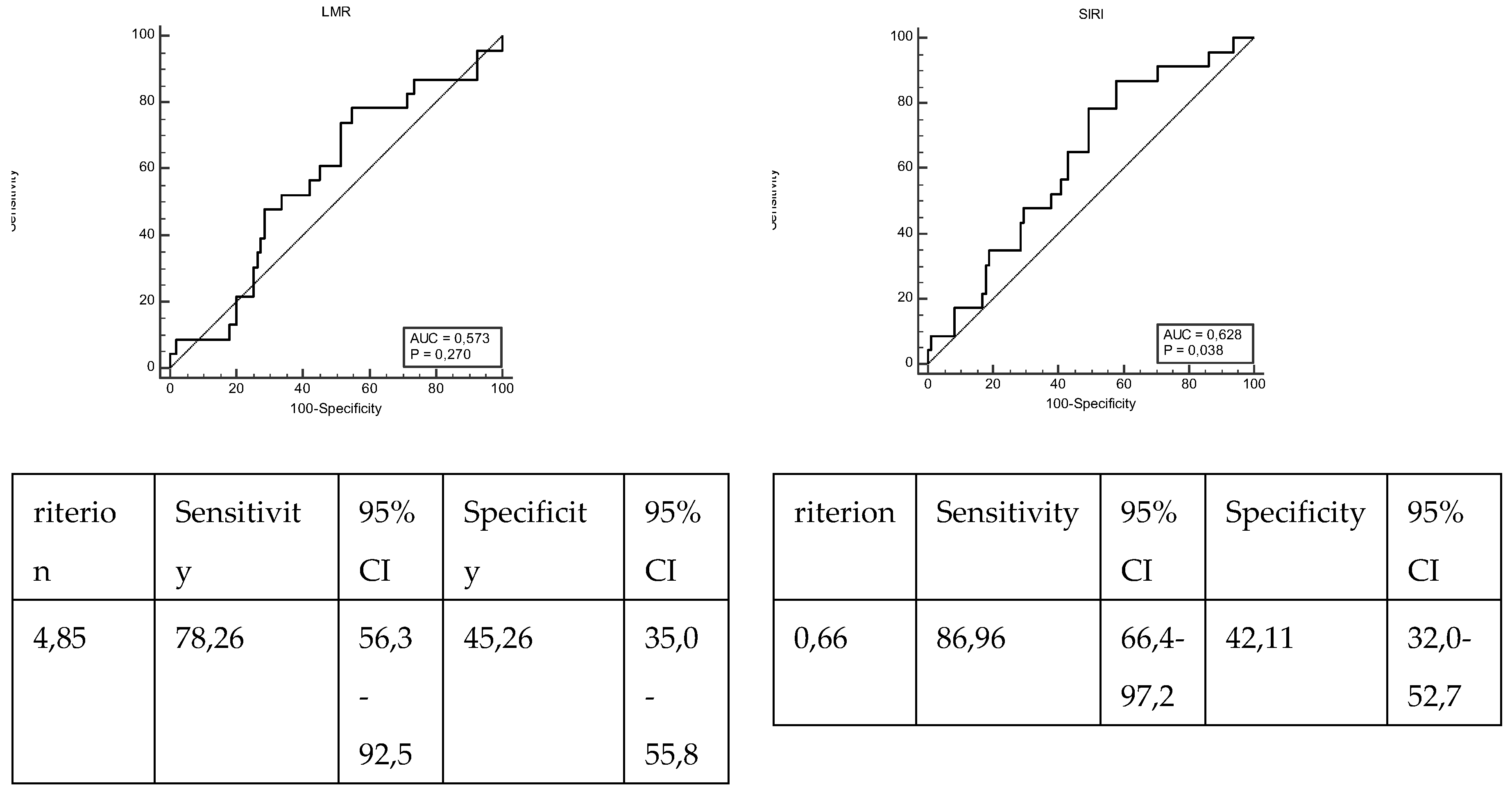

| LMR | ≤4.85 | 70 (59.32) |

| >4.85 | 48 (40.68) | |

| CLR | ≤0.49 | 66 (55.93) |

| >0.49 | 52 (44.07) | |

| SII | ≤444.25 | 55 (46.61) |

| >444.25 | 63 (53.39) | |

| SIRI | ≤0.66 | 43 (36.44) |

| >0.66 | 75 (63.56) | |

| Median Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) | 85.96±7.41 | 87 (73-105) |

| Median Carbon Monoxide Diffusion Capacity (DLCO) | 68.18±13.44 | 70 (34-88) |

| Variables | Pulmonary toxicity | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age at Diagnosis | 15-29 years | 43 (45,26) | 10 (43,48) | 0,880 |

| 30-39 years | 35 (36,84) | 8 (34,78) | ||

| 40-49 years | 12 (12,63) | 3 (13,04) | ||

| ≥ 50 years | 5 (5,26) | 2 (8,7) | ||

| Smoking History | No | 66 (69,47) | 10 (43,48) | 0,028* |

| Yes | 29 (30,53) | 13 (56,52) | ||

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status | 0 | 89 (93,68) | 23 (100) | 1,000 |

| 1 | 3 (3,16) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2 | 1 (1,05) | 0 (0) | ||

| 3 | 2 (2,11) | 0 (0) | ||

| Histopathology | Seminoma | 34 (35,79) | 9 (39,13) | 0,716 |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 15 (15,79) | 5 (21,74) | ||

| Mixed germ cell carcinoma | 45 (47,37) | 9 (39,13) | ||

| Epididymal invasion | No | 90 (94,74) | 22 (95,65) | 1,000 |

| Yes | 5 (5,26) | 1 (4,35) | ||

| Tunica albuginea invasion | No | 82 (86,32) | 19 (82,61) | 0,741 |

| Yes | 13 (13,68) | 4 (17,39) | ||

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | No | 89 (93,68) | 23 (100) | 0,596 |

| Yes | 6 (6,32) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | No | 43 (45,26) | 9 (39,13) | 0,646 |

| Yes | 52 (54,74) | 14 (60,87) | ||

| Tumor localization | Right | 46 (48,42) | 10 (43,48) | 0,818 |

| Left | 46 (48,42) | 13 (56,52) | ||

| Bilateral | 3 (3,16) | 0 (0) | ||

| Diagnostic symptom | Mass | 40 (42,11) | 13 (56,52) | 0,362 |

| Swelling | 31 (32,63) | 4 (17,39) | ||

| Pain | 24 (25,26) | 6 (26,09) | ||

| Stage | Stage 1 | 56 (58,95) | 13 (56,52) | 0,381 |

| Stage 2 | 25 (26,32) | 4 (17,39) | ||

| Stage 3 | 14 (14,74) | 6 (26,09) | ||

| Radiotherapy | No | 90 (94,74) | 23 (100) | 0,582 |

| Yes | 5 (5,26) | 0 (0) | ||

| Surgery | No | 4 (4,21) | 0 (0) | 1,000 |

| Yes | 91 (95,79) | 23 (100) | ||

| Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection | No | 69 (72,63) | 17 (73,91) | 1,000 |

| Yes | 26 (27,37) | 6 (26,09) | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | No | 15 (15,79) | 4 (17,39) | 1,000 |

| Yes | 80 (84,21) | 19 (82,61) | ||

| NLR | ≤1,64 | 48 (50,53) | 2 (8,7) | 0,001* |

| >1,64 | 47 (49,47) | 21 (91,3) | ||

| PLR | ≤93,92 | 30 (31,58) | 2 (8,7) | 0,035* |

| >93,92 | 65 (68,42) | 21 (91,3) | ||

| LMR | ≤4,85 | 52 (54,74) | 18 (78,26) | 0,057 |

| >4,85 | 43 (45,26) | 5 (21,74) | ||

| CLR | ≤0,49 | 58 (61,05) | 8 (34,78) | 0,034* |

| >0,49 | 37 (38,95) | 15 (65,22) | ||

| SII | ≤444,25 | 53 (55,79) | 2 (8,7) | 0,001* |

| >444,25 | 42 (44,21) | 21 (91,3) | ||

| SIRI | ≤0,66 | 40 (42,11) | 3 (13,04) | 0,014* |

| >0,66 | 55 (57,89) | 20 (86,96) | ||

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | p | OR(95%CI) | p | ||

| Age at Diagnosis | 15-29 years | 1 (reference) | 0,941 | ||

| 30-39 years | 0,983 (0,35-2,756) | 0,974 | |||

| 40-49 years | 1,075 (0,255-4,538) | 0,922 | |||

| ≥ 50 years | 1,72 (0,291-10,182) | 0,550 | |||

| Smoking History | Yes | 2,959 (1,164-7,52) | 0,023* | 5,23(1,536-17,814) | ,008* |

| Histopathology | Seminoma | 1 (reference) | 0,872 | ||

| Embryonal carcinoma | 1,259 (0,361-4,398) | 0,718 | |||

| Mixed germ cell carcinoma | 0,756 (0,271-2,107) | 0,592 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion | No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1,286 (0,508-3,259) | 0,596 | |||

| Tumor localization | Right | 1 (reference) | 0,855 | ||

| Left | 1,3(0,518-3,263) | 0,576 | |||

| Diagnostic symptom | Mass | 1 (reference) | 0,329 | ||

| Swelling | 0,397 (0,118-1,338) | 0,136 | |||

| Pain | 0,769 (0,258-2,292) | 0,638 | |||

| Stage | Stage 1 | 1 (reference) | 0,374 | ||

| Stage 2 | 0,689 (0,204-2,325) | 0,549 | |||

| Stage 3 | 1,846 (0,596-5,72) | 0,288 | |||

| Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection | No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 0,937 (0,333-2,635) | 0,901 | |||

| NLR | ≤1,64 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >1,64 | 10,723 (2,38-48,306) | 0,002* | 3,811 (0,389-37,314) | ,250 | |

| PLR | ≤93,92 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >93,92 | 4,846 (1,067-22,015) | 0,041* | 1,863 (0,296-11,727) | ,507 | |

| LMR | ≤4,85 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >4,85 | 0,336 (0,115-0,979) | 0,046* | 1,038 (0,215-5,016) | ,963 | |

| CLR | ≤0,49 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >0,49 | 2,939 (1,134-7,615) | 0,026* | 3,24 (0,995-10,547) | ,051 | |

| SII | ≤444,25 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >444,25 | 13,25 (2,939-59,731) | 0,001* | 8,011 (0,933-68,809) | ,058 | |

| SIRI | ≤0,66 | 1 (reference) | |||

| >0,66 | 4,848 (1,348-17,439) | 0,016* | 0,536 (0,061-4,671) | ,572 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).