1. Introduction

The coffee industry has become an important driver of economic development in various regions of the world, mainly due to the high consumption of its products, the low cost of raw materials, and the standardization of production costs [

1,

2,

3]. The International Coffee Organization (ICO) reports that South America grows more than 45% of the coffee traded worldwide, positioning Brazil as the largest producer and consumer globally [

4]. In terms of production by country, Brazil is reported to generate a total of 65.9 million bags (60 kg) annually. At the South American level, Ecuador is among the top 5 producers, with a production of close to 0.5 million 60 kg bags. In addition, in 2024, global consumption was reported to be approximately 177 million 60 kg bags, showing an increase in the consumption rate of around 2.2% compared to the previous year [

4].

Despite the constant growth of this industry, there is evidence of high waste generation and poor implementation of efficient and sustainable treatment technologies. [

5] report out that approximately 70% of this waste is discharged directly without any treatment, affecting the sustainability of natural resources. Specifically, [

6] established that wastewater from the coffee industry has a high pollution potential due to its high organic load, color, and pH [

7], which deepens its impact on the water bodies into which it is discharged. The characteristics of this wastewater have been evaluated by several authors, highlighting the presence of non-biodegradable pollutants and chemical oxygen demand (COD) concentrations in the range of 13 and 29.5 g L

-1 [

8,

9,

10]. In countries such as Ecuador, it has been reported that, on average, wastewater from the coffee industry has a COD of 7500 mg L

-1 [

11]; however, it has been observed that although this country is among the top five coffee producers in the region and has several coffee processing industries, adequate treatment for the decontamination and recovery of this waste is not carried out, which affects the economic and environmental sustainability of these industries.

There is evidence demonstrating the possibility of applying anaerobic digestion (AD) as an effective treatment for various types of industrial wastewater [

12,

13]. Studies conducted by [

14,

15,

16] converge on the idea of implementing AD as a sustainable alternative in industrial wastewater management and the generation of value-added products such as biogas. In this regard, [

17] achieved a 93% removal of COD from industrial coffee wastewater and a yield of 0.33 m

3 CH

4 kg

-1COD through two-stage upflow reactors. For their part, [

18] evaluated methane production from brewing and coffee industry waste and reported efficiencies of 0.75 m

3 CH

4 kg

-1 of total volatile solids.

Although AD technology has advantages in wastewater treatment, its implementation in industry depends on large-scale economic feasibility. In this regard, it is necessary to evaluate profitability using models that assess technical aspects based on biophysical sustainability indicators and economic parameters such as the payback period (PB), net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and total investment cost [

19]. Each of these parameters provides results for the analysis of a novel alternative for wastewater treatment that can be implemented in countries with high industrial coffee activity. Therefore, the objective of this research is to evaluate the technical and economic feasibility of redesigning a real coffee processing wastewater treatment plant that incorporates the AD process as an operation for the elimination of organic load and the revaluation of waste. Based on these results, the coffee processing industry will have at its disposal a comparative analysis between conventional treatment (aerobic digestion) and a redesign of the treatment plant through the implementation of AD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

As part of this research, a technological proposal was developed for the anaerobic treatment of wastewater from the coffee industry, along with a technical, economic, and environmental assessment. A coffee production industry located in the province of Guayas, Ecuador, was taken as a case study. The company produces 4,913.6 tons of instant coffee per year and generates an average of 210 m3 d-1 of wastewater.

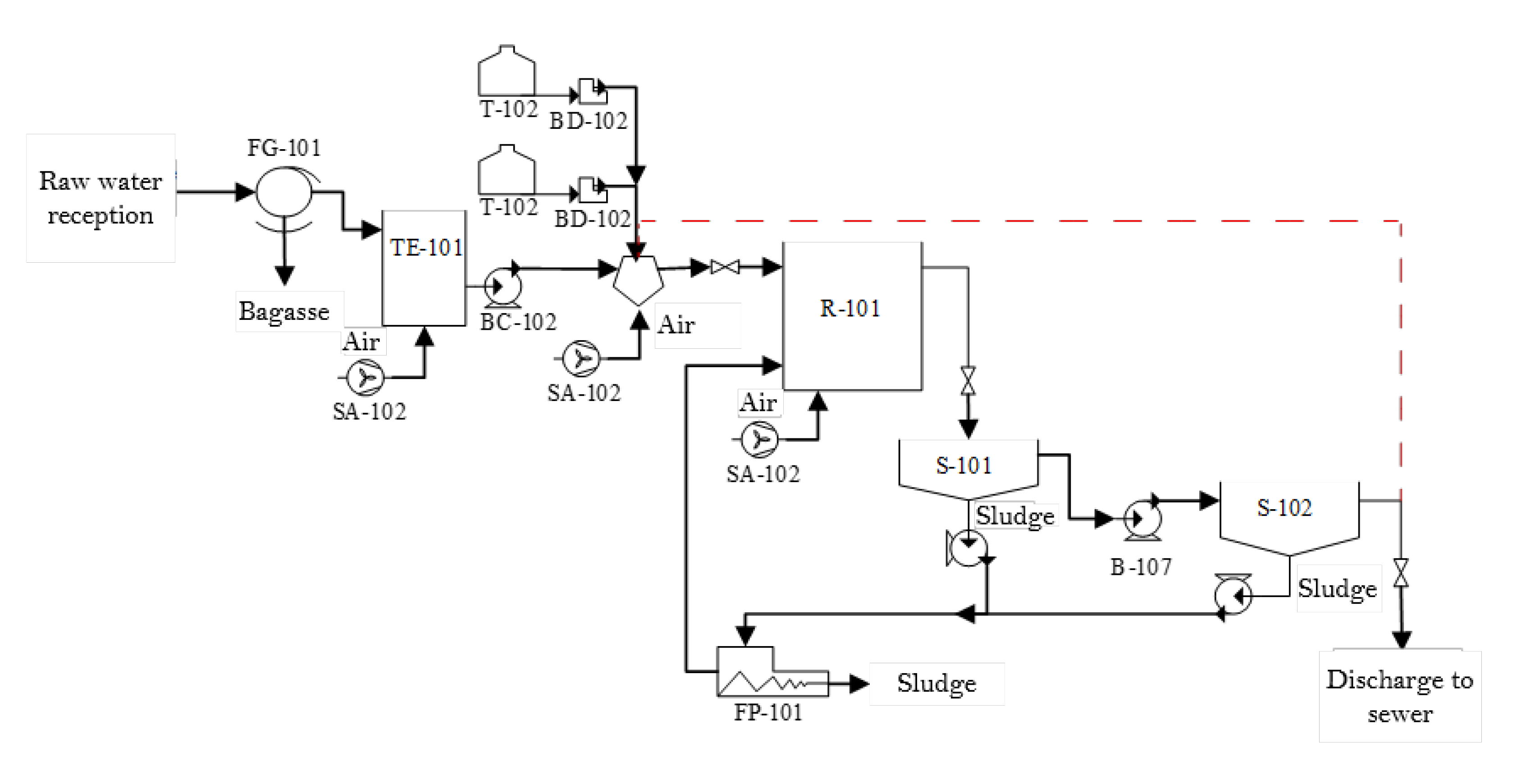

Figure 1 shows the current layout of the plant used by the industry for wastewater treatment, with its respective designation (

Table 1).

2.2. Experimental Study of the AD Process

2.2.1. Preparation of the Substrate and Inoculum

The experimental tests were carried out with simulated wastewater prepared in the laboratory. The purpose of this preparation was to homogenize the variable composition of wastewater from the instant coffee industry, thereby ensuring the reproducibility of the results obtained in the research. The simulated wastewater was prepared following the procedure reported by [

11,

20]. To stabilize the operation of the continuous reactors, a feed COD of 7500 mg L

-1 was used. Additionally, real samples of wastewater from the industry were taken. The samples were stored in sterile containers under refrigeration (4 °C) before their use in the experimental tests.

The inoculum was prepared using sludge from a tuna industry located in Manabí-Ecuador, which treats its wastewater using AD. The sludge was degassed and fed with wastewater from the coffee industry for 30 days. Subsequently, it was verified that the inoculum contained at least 50% volatile solids (VS) on a dry basis, in accordance with the techniques reported in previous studies [

18].

2.3. Assembly and Operation of Continuous Reactors

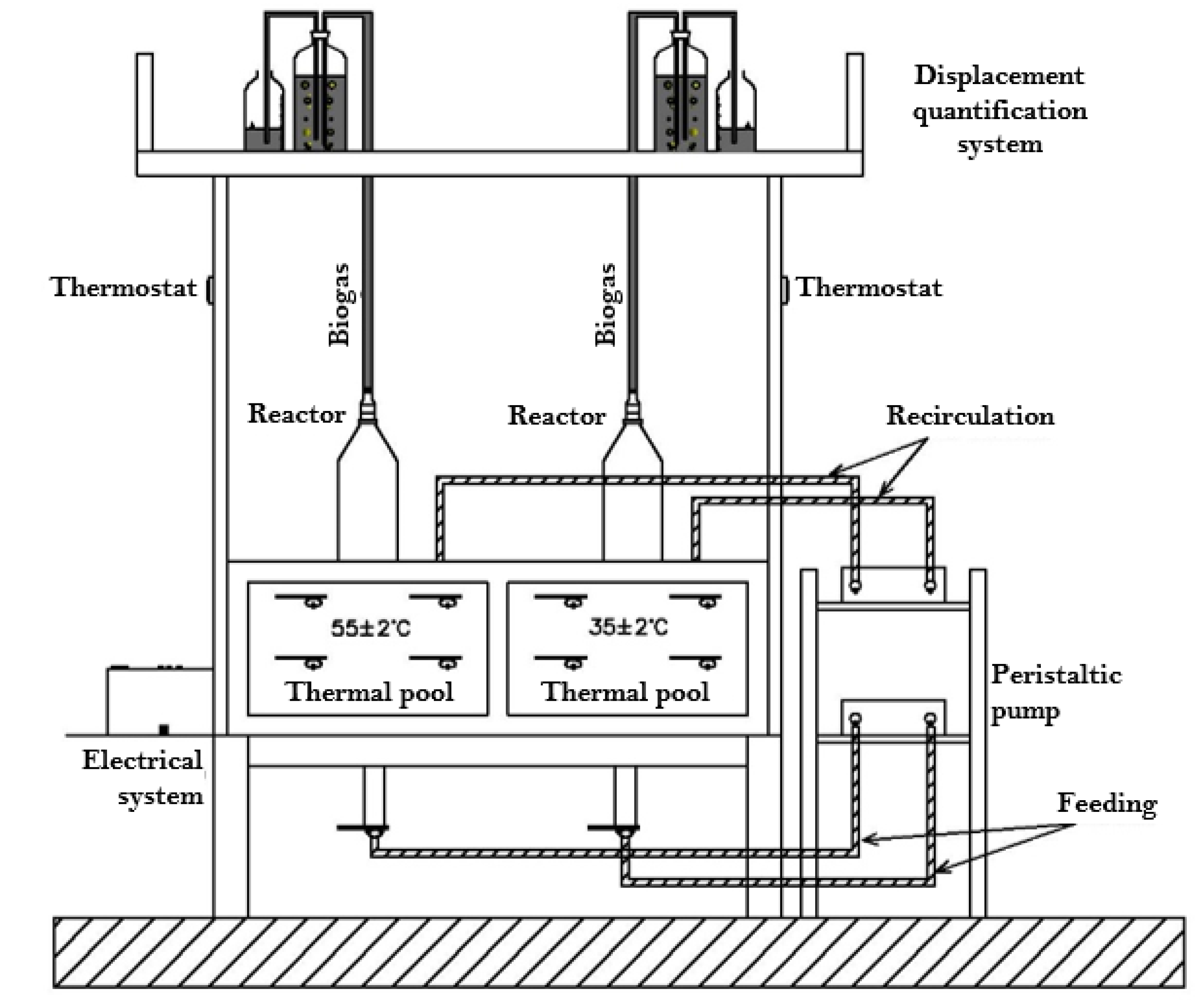

The experimental tests were carried out in upflow anaerobic filter (UAF) biological reactors at mesophilic (35 °C ±2 °C) and thermophilic (55 °C ±2 °C) temperatures (

Figure 2). The reactors were constructed from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes with a height of 0.7 m, an internal diameter of 0.12 m, an effective volume of 3 L, a corrugated plastic packing volume of 0.30 L, and an inoculum that occupied 40% of the total volume of the reactors. The reactors operated for 454 days. The reactors were started at a low organic load (0.75 kg COD m

-3d

-1) during the first 36 days. Subsequently, the organic loading rate (OLR) was progressively increased to 1.02, 1.32, 1.63, 2.23, and 2.63 kg COD m

-3 d

-1. This allowed the microorganisms involved in the AD reactions to avoid sudden changes in substrate loading and adapt until the desired OLR was reached.

The peristaltic pumps used for feeding, recirculation, and discharge during the experiment were DP4-4 CHANNEL JECOD pumps. The biogas generated was brought into contact with a 15% (w/v) NaOH solution, which allowed the displacement of the solution to be measured and thus the volume of CH

4 generated to be quantified (

Figure 2). The volume of methane was reported under standard temperature (0 °C) and pressure (101.3 kPa) conditions. In addition, collection bags were placed to store and subsequently characterize the biogas using Multitec

®®545 equipment.

Methane yield was obtained from the following equation, as reported by [

21] and [

22] in studies with similar reactors.

where:

Y CH4: Methane yield (NmL CH4 g-1COD).

V CH4: Volume of methane accumulated during digestion time under standardized conditions (N mL).

t: time (d).

g COD: Mass of chemical oxygen demand contributed by the substrate (g COD).

2.4. Analytical Tests for Process Control

The analytical tests carried out during the experimental study were performed according to standard methods for wastewater analysis [

23]. The parameters were evaluated depending on the requirements of each control point (inflow and outflow). All tests and analyses were performed in triplicate (

Table 2).

2.5. Kinetic Study

The kinetics of the AD process were calculated using the modified Stover-Kincannon model (Eq. 2) and Grau’s second-order multicomponent substrate elimination model (Eq. 3). The linearization of both models has been previously described in [

24] and [

25], respectively.

where:

dS/dt: substrate removal rate.

KB: saturation constant (kg m-3d-1).

Umax: maximum substrate utilization rate (kg m-3d-1).

V: reactor volume (m3).

Q: volumetric flow rate of wastewater (m3 d-1).

So: substrate concentration in the influent (kg m

-3).

where:

So: substrate concentration in the influent (kg m-3).

S: substrate concentration in the effluent (kg m-3).

HRT: hydraulic retention time (d).

a: ratio between So/ksXo.

b: dimensionless constant reflecting the impossibility of reaching zero for the substrate concentration at a given HRT.

2.6. Technical and Economic Evaluation and Sustainability of the Proposal

The economic analysis of the integrated process was carried out using the total investment cost (TIC), the total production cost, and the cash flow of a plant that undergoes a modification to its conventional scheme. This plant incorporates an AD operation for the treatment of wastewater from the soluble coffee industry. The unit costs for the preliminary design or initial cost estimate of the technological equipment were obtained from information available in industrial catalogs and websites of suppliers worldwide. The Hand method was applied to calculate the TIC, using the factors proposed for each piece of equipment according to Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook [

26]. The economic feasibility of the proposal was evaluated in United States Dollars (USD). Depreciation was considered linear over 10 years for the installed technological equipment, and a discount rate of 15% was used.

The AD process was scaled using the OLR method, which determines the required volume of each reactor, keeping the OLR obtained at the experimental scale constant [

27].

As indicators of economic feasibility, the sensitivity of the PB, NPV, and IRR was evaluated according to the equations proposed in the work of [

19]. Additionally, a proposal for biophysical sustainability indicators specific to the coffee industry was made, based on the parameters shown in

Table 3

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Wastewater

This study characterized wastewater from a coffee industry located in Guayas, Ecuador, as well as simulated wastewater prepared in the laboratory.

Table 4 shows the results of the physical, chemical, and biological characterization of both types of wastewater.

The physical and chemical parameters that characterize wastewater from the coffee industry show high variability [

28]. This is due to the use of different coffee varieties, the harvest season, and the technological alternatives employed [

29].

Table 4 shows the aforementioned difference, since in parameters such as COD and pH, simulated water offers ranges with less variability (and therefore greater stability) [

30]. In addition, [

10] report that the COD of wastewater from coffee processing is between 6420 and 8480 mg L

-1, which reflects an average COD similar to that of the simulated wastewater in this study. However, the pH of the simulated water differs from the reports of other studies, where the processed effluent has an acidic pH: 4.7-6 [

31] and 3.9-4.1 [

10]. It should be noted that the contaminant parameter of greatest interest in AD is COD, since it is related to the amount of substrate available to anaerobic microorganisms.

3.2. AD Process Yields

The UAF reactors were continuously monitored based on parameters such as pH and the VFA/Alc ratio, whose values remained within the appropriate ranges for the proper performance of the AD process. When comparing the behavior between mesophilic and thermophilic reactors, it was demonstrated that the mesophilic system had more stable operating periods. The average methane yield ranged from 200.5±45.8 NmL CH

4 g

-1CDO for the mesophilic reactor. This value represents 93.6% of the value obtained through mathematical modeling for the mesophilic conditions reported by [

11]. In addition, a COD removal efficiency of 64.1% was obtained. This demonstrated that the yields obtained in the present investigation exceed those reported in previous studies [

32] and are similar to those proposed by [

17].

3.3. Kinetic Study

The results of this study consolidate the proposal of the mesophilic regime for a wastewater treatment plant in the coffee industry. To consolidate this proposal, a kinetic analysis was performed. The models applied to the reactors are based on the substrate utilization rate, while observing the production of the main metabolite of the reaction [

33]. For the kinetic analysis, periods in which the HRT is repeated at least three times are selected. In this case, the HRT periods were repeated in the interval: 4-7.7. Both the modified Stover-Kincannon and second-order Grau models were adjusted with high correlation coefficients (R

2˃95%) for the mesophilic system and with lower coefficients for the thermophilic system (R

2<63%). [

34] also worked with these kinetic models and achieved a fit to Grau’s second-order multiple substrate removal model with an R

2 of 57.1% for brewery wastewater. [

35] evaluated wastewater from the tomato processing industry and fitted the data to the modified Stover-Kincannon model, reporting lower R

2 values (42%); thus demonstrating that AD of coffee wastewater in a continuous regime fits the modified Stover-Kincannon and Grau kinetic models, preferably at mesophilic temperatures.

Similarly, the modified Stover-Kincannon model yielded the following parameters: Umax: 17.9 g L

-1d

-1, KB: 27.9 g L

-1d

-1, and Umax: 1.15 g L

-1d

-1, KB: 1.03 g L

-1d

-1 for mesophilic and thermophilic systems, respectively. The Umax values reported in this study for mesophilic conditions coincide with those reported by [

36] for slaughterhouse wastewater.

It is evident that the behavior in thermophilic conditions is more linear, and the interpretation of this behavior is based on the greater inhibitory expression of compounds that may be present in wastewater from the coffee industry (e.g., tannins), which slows down the process and limits microbial activity. Finally, it can be confirmed that the best system for anaerobic treatment of wastewater from the coffee industry is based on a mesophilic regime, and the following parameters are set for the design of the anaerobic unit of the treatment plant in the industry: HRT = 7.3 d and OLR = 1.03 kg COD m3 d-1 for a YCH4: 206.7 NmL g-1COD.

3.4. Technological Proposal with the Redesign of the Treatment Plant

The technological process conventionally applied by the coffee industry’s wastewater treatment plant is characterized by effluent that often fails to comply with current regulations for discharge into water bodies.

Figure 1 shows a red line that is enabled on occasions when, even after undergoing the treatment process, the wastewater does not comply with regulations and is returned to the coagulation-flocculation unit.

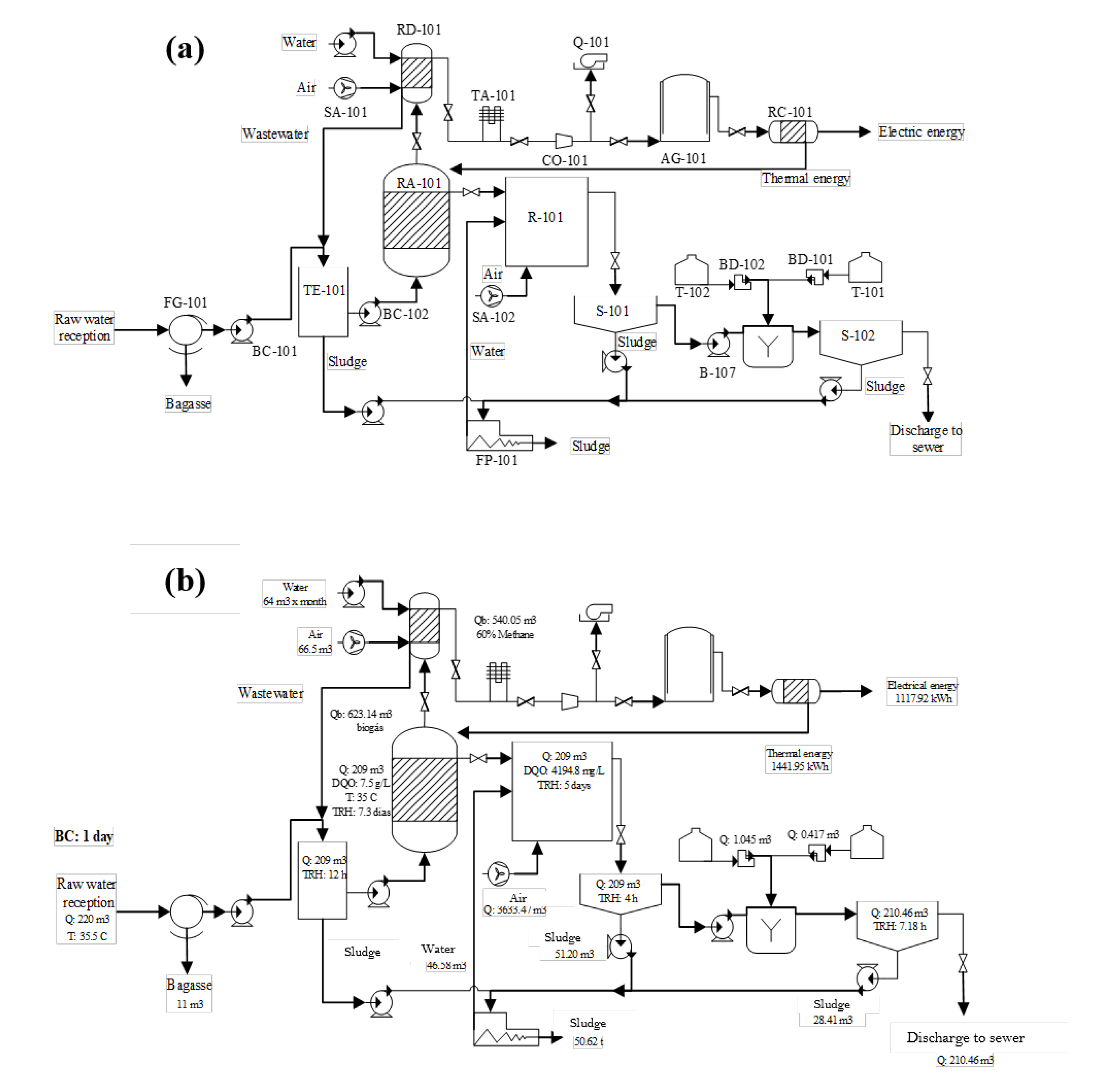

As a result of this work, the incorporation of an anaerobic unit (RA-101) is proposed as a pre-treatment to the aerobic reactor. Similarly, a modification is suggested at the point where the coagulation-flocculation stage is applied, and the redesigned system is shown in

Figure 3. Taking into account the operational parameters established in the previous sections for the design and sizing of the anaerobic process, the material balance of the redesigned technological proposal is shown in section b of

Figure 3.

3.5. Economic Evaluation of the Technological Proposal

The Hand method was used to calculate the total investment cost of the processing plant, reporting a TIC of USD 467,392.51. Research such as that by [

37] has compared the investment cost in different operating scenarios for AD of agro-industrial waste, reflecting an investment ranging from USD 555,117 to USD 635,396. Consequently, the IRR proposed in this research is lower than that reported in other case studies, which may be related to the installed capacity of the treatment plants, since the studies mentioned [

37,

38] were carried out in plants with a higher feed flow.

On the other hand,

Table 5 shows the items considered as income for the treatment plant for each year of operation.

As shown in the table above, the revenue from sales of the comprehensive anaerobic treatment of wastewater from coffee production takes into account the sale of electricity generated from methane and the sale of solid digestate (biofertilizer). The prices for each of these are $0.17 per kWh and $1.15 per m3, respectively.

The production costs associated with the treatment of this industrial wastewater amount to USD 142,692.77 per year. An analysis of this information shows that the range of investment that would be generated in the treatment plant does not meet economic expectations, as production costs are higher than the profits obtained from the sale of usable products (USD 86,216.29 per year). This economic trend has also been reported in other studies, in which production costs exceed the income that could potentially be generated by implementing AD as a stage in the treatment process. For example, [

37] report an annual production cost (USD 49,424) that exceeds the annual income from the sale of electricity (USD 22,893) and solid digestate (USD 12,096). In fact, [

39] and [

40] report that among the main factors that can affect the feasibility and economic sustainability of these treatment plants are high production and investment costs. For this reason, it is essential to propose price stabilization for the main product of this industry (soluble coffee), which would make the proposal in this study profitable.

In recent years, the price of a bag of industrialized coffee (60 kg bags) has varied between USD 150 and USD 192, meaning that this product is subject to high price fluctuations on the international market. There is a trend of instability in the prices of industrialized coffee, which means that the income received by soluble coffee processing industries varies constantly and, as a result, the profitability of these companies undergoes periodic variations. Therefore, it is possible to make this technological proposal profitable based on the potential gains that can be obtained by ensuring that the price of soluble coffee remains above USD 170.6.

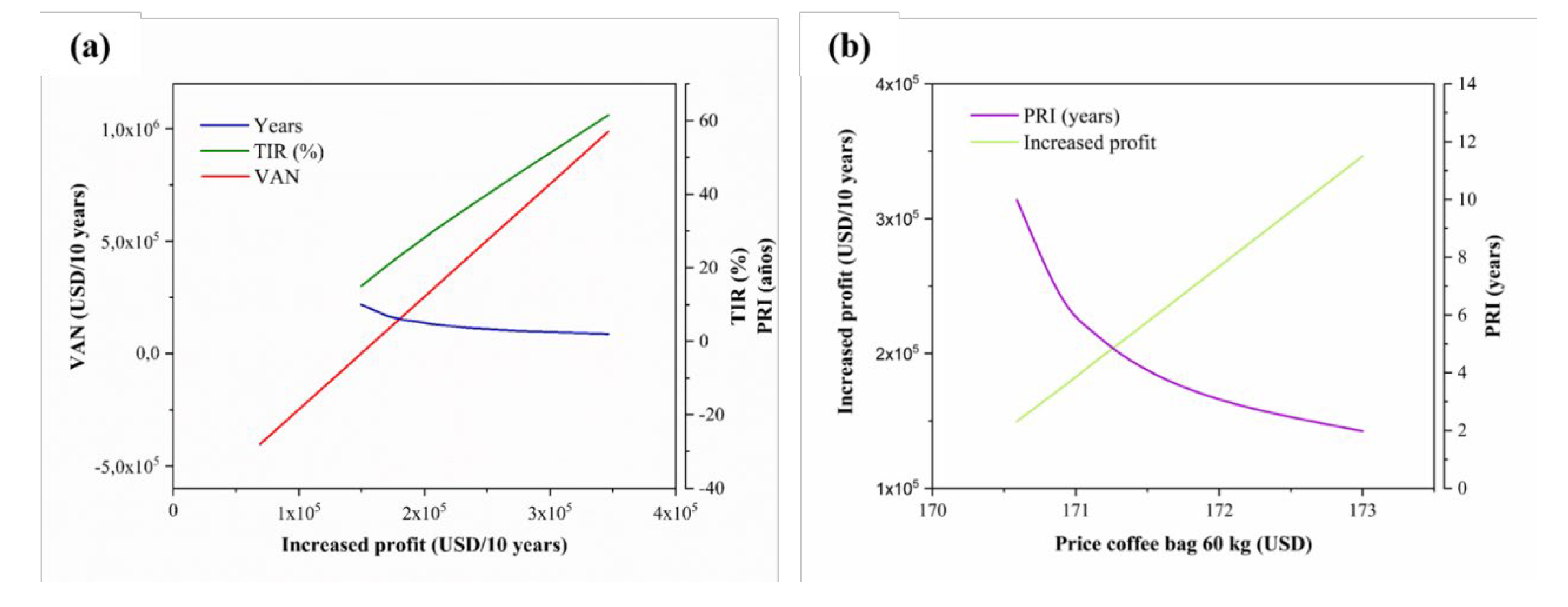

Based on the increase in profits that would be generated for the industry evaluated at USD 170.6 per 60 kg bag, a positive NPV is obtained after 10 years of investment project planning. Higher increases in profits can lead to a faster return on investment. Taking this into account, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of the increase in profit from the sale of soluble coffee on the main economic indicators. These results are shown in

Figure 4.

The behavior of the NPV, IRR, and PB indicators with the increase in profits is as expected (

Figure 4a). As profits increase, both the NPV and IRR increase in value. Conversely, PB decreases with increasing dividends, tending to show little variability with respect to the given price of a 60 kg bag of coffee (Figure 5b). By analyzing the curve (Figure 5b), it is possible to determine the price at which the inflection point is reached, beyond which PB variability is minimal. The inflection point corresponds to a price of

$171.11 per 60 kg bag, which leads to an NPV of

$212,469.35, an IRR of 26.1%, and a PB of 5.47 years.

When comparing these results with similar research, [

38] also informed by favorable economic indicators, with an NPV (USD 600,603) and an IRR (23%) very close to those obtained in the present study, although [

38] used anaerobic co-digestion with a combination of substrates with high nutrient content. Similarly, [

41] concluded that in an AD plant designed for the treatment of agricultural waste, the investment was recovered after the fourth year of operation, reporting a relatively lower PB than that obtained in this research.

3.6. Biophysical Indicators of Sustainability for the Proposal

In accordance with the general characteristics of the coffee production plant where the proposal to implement AD was made, the biophysical indicators indicated in the materials and methods section were developed.

Table 6 shows the values of the parameters that were considered in the technological proposal based on the implementation of AD.

In accordance with the above, each of the biophysical sustainability indicators for this soluble coffee production plant was calculated.

Table 7 shows the results of the biophysical indicator system. As can be seen in

Table 7, these indicators were chosen based on the contributions that the redesign of the treatment plant makes to the sustainability of the coffee industry. In all cases, when sustainability indicators are applied to the coffee industry without anaerobic wastewater treatment, the value of each indicator is zero, as it does not represent any of the benefits that anaerobic treatment brings to the overall sustainability of the company.

It has been observed that AD contributes significantly to the technical, economic, and environmental sustainability of the coffee industry. First, it generates a quantity of energy, both electrical and thermal, that can result in savings for the industry, since it would reduce the energy bill required to operate the plant without the need to consume external energy sources. It has been confirmed that the electrical energy that can be generated from biogas is 1.67 times greater than that consumed in the proposed facility, so there is no additional cost for this item.

Furthermore, the application of AD allows the effluent generated in the treatment plant to comply with the technical specifications of Ecuador’s environmental regulations, which is not currently the case, and consequently generates economic and legal problems. This is because one of the solutions that these industries have used consists of diluting the effluent with water to comply with the discharge limits according to environmental standards, which is completely untechnical. This aspect is fundamental, since the footprint of industrial activities is altering the composition of water bodies and hindering the operation of water and wastewater treatment systems, which, in accordance with target 6.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals, aim to optimize quality and reduce water scarcity [

42,

43].

Another important indicator for business sustainability is the impact that implementing an AD stage in wastewater treatment has on air quality. This technological proposal would prevent the emission of 17.93 tons of CO

2 per day. This is based on the high CO

2 load generated in conventional treatment processes [

44]. The amount of CO

2 that does not enter the atmosphere is a vital element in the production of low-carbon footprint soluble coffee, giving anaerobic treatment competitive advantages [

45,

46].

Additionally, the implementation of the evaluated technological proposal has a potential socio-economic impact, as it would increase the visibility of coffee-producing industries with international certifications and promote a sustainable Ecuadorian coffee economy.

4. Conclusions

AD was shown to be a technically and environmentally viable alternative for treating wastewater generated in the coffee industry. Tests in UAF reactors showed that the mesophilic regime has greater operational stability and significant methane yields (200.5 NmL CH4 g-1COD), with a COD removal of 64.1%. Likewise, the data fitted favorably to the modified Stover-Kincannon and Grau kinetic models (R2>95%). Optimal operating parameters were established for the redesign of the coffee wastewater treatment plant, such that the implementation of AD in the conventional aerobic digestion-based process results in a reduction of 17.93 tCO2 d-1, thus reinforcing its contribution to environmental sustainability.

The inclusion of biophysical sustainability indicators showed that the anaerobic system generates a favorable energy balance, producing 1.67 times more electrical energy than the plant consumes. Similarly, 1117.9 kWh d-1 and 1441.9 kWh d-1 of electrical and thermal energy were achieved from biogas, in addition to the use of solid digestate as a biofertilizer. These results confirm the contribution of the proposed technology to both emissions reduction and energy efficiency in the coffee sector.

Finally, the economic analysis revealed that profitability depends on the stabilization of the price of soluble coffee above USD 171.11 per 60 kg bag, which represents a challenge in contexts of market volatility. In this regard, future research should focus on integrating co-digestion with other agro-industrial waste, optimizing the recovery of digestate, and applying economic incentives that promote low environmental impact technologies. These aspects are essential to consolidate the overall viability of AD as a pillar of sustainability in the coffee industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.C.M., and C.A.M.P.; methodology, R.A.C.M., C.A.M.P., J.M.R.D., and I.P.R.; formal analysis, C.A.M.P., M.D.S., and N.B.B.; investigation, R.A.C.M., C.A.M.P., and I.P.R.; resources, M.D.S., N.B.B., J.M.R.D., and I.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.C.M., and C.A.M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.D.S., N.B.B., J.M.R.D., and I.P.R.; visualization, R.A.C.M., C.A.M.P., M.D.S., and N.B.B.; supervision, J.M.R.D., and I.P.R.; project administration, J.M.R.D., and I.P.R.; funding acquisition, M.D.S., N.B.B., and J.M.R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Técnica de Manabí (UTM) for its support in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- da Cruz Correia, P.F.; Mendes dos Reis, J.G.; Amorim, P.S.; Costa, J.S. da; da Silva, M.T. Impacts of Brazilian Green Coffee Production and Its Logistical Corridors on the International Coffee Market. Logistics 2024, Vol. 8, Page 39 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G. V.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; do Prado, F.G.; Pagnoncelli, M.G.B.; Karp, S.G.; Soccol, C.R. Chemical Composition and Health Properties of Coffee and Coffee By-Products. Adv Food Nutr Res 2020, 91, 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittichotsatsawat, Y.; Tippayawong, N.; Tippayawong, K.Y. Prediction of Arabica Coffee Production Using Artificial Neural Network and Multiple Linear Regression Techniques. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICO Coffee Report and Outlook Available online:. Available online: https://icocoffee.org/documents/cy2023-24/Coffee_Report_and_Outlook_December_2023_ICO.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Bondam, A.F.; Diolinda da Silveira, D.; Pozzada dos Santos, J.; Hoffmann, J.F. Phenolic Compounds from Coffee By-Products: Extraction and Application in the Food and Pharmaceutical Industries. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 123, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.M.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Ismail, N. ‘Izzati; Hasan, H.A.; Othman, A.R. Phytoremediation of Real Coffee Industry Effluent through a Continuous Two-Stage Constructed Wetland System. Environ Technol Innov 2020, 17, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, S.; Agudelo-Escobar, L.M. Determination of Electrogenic Potential and Removal of Organic Matter from Industrial Coffee Wastewater Using a Native Community in a Non-Conventional Microbial Fuel Cell. Processes 2023, Vol. 11, Page 373 2023, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Escobar, L.M.; Cabrera, S.E.; Avignone Rossa, C. A Bioelectrochemical System for Waste Degradation and Energy Recovery From Industrial Coffee Wastewater. Frontiers in Chemical Engineering 2022, 4, 814987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.C.; Pinto, V.R.A.; Melo, L.F.; Rocha, S.J.S.S. da; Coimbra, J.S. New Sustainable Perspectives for “Coffee Wastewater” and Other by-Products: A Critical Review. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamurugan, M.; Doraisamy, P.; Maheswari, M. An Integrated Treatment System for Coffee Processing Wastewater Using Anaerobic and Aerobic Process. Ecol Eng 2010, 36, 1686–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova Mosquera, A.; Gómez-Salcedo, Y.; Riera, M.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M.; Pereda-Reyes, I.; Córdova Mosquera, A.; Gómez-Salcedo, Y.; Riera, M.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M.; Pereda-Reyes, I. Influencia de Los Procesos Oxidativos Avanzados En La Digestión Anaerobia de Aguas Residuales de La Industria Del Café. Centro Azúcar 2019, 46, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bułkowska, K.; Zielińska, M. Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion of Spent Coffee Grounds: A Review of Pretreatment Strategies for Sustainable Valorization. Energies 2025, Vol. 18, Page 4810 2025, 18, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, C.; Ma, G.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, D.; Li, Y.Y.; et al. Anaerobic Treatment of Nitrogenous Industrial Organic Wastewater by Carbon–Neutral Processes Integrated with Anaerobic Digestion and Partial Nitritation/Anammox: Critical Review of Current Advances and Future Directions. Bioresour Technol 2025, 415, 131648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. Enhancing Anaerobic Digestion of Pharmaceutical Industries Wastewater with the Composite Addition of Zero Valent Iron (ZVI) and Granular Activated Carbon (GAC). Bioresour Technol 2022, 346, 126566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X. The Promotion of Anaerobic Digestion Technology Upgrades in Waste Stream Treatment Plants for Circular Economy in the Context of “Dual Carbon”: Global Status, Development Trend, and Future Challenges. Water 2024, Vol. 16, Page 3718 2024, 16, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, T.; Pereda-Reyes, I.; Correia, G.T.; Pozzi, E.; Kwong, W.H.; Oliva-Merencio, D.; Zaiat, M.; Montalvo, S.; Huiliñir, C. Performance of EGSB Reactor Using Natural Zeolite as Support for Treatment of Synthetic Swine Wastewater. J Environ Chem Eng 2021, 9, 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.W.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Shin, H.S. Two-Stage UASB Reactor Converting Coffee Drink Manufacturing Wastewater to Hydrogen and Methane. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 7473–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.; Camargo, F.P.; Lourenço, V.A.; Sakamoto, I.K.; Maintinguer, S.I.; Silva, E.L.; Varesche, M.B.A. Optimized Conditions for Methane Production and Energy Valorization through Co-Digestion of Solid and Liquid Wastes from Coffee and Beer Industries Using Granular Sludge and Cattle Manure. J Environ Chem Eng 2023, 11, 111250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthos, G.; Zagklis, D.; Zafiri, C.; Kornaros, M. Techno-Economic Assessment of Anaerobic Digestion for Olive Oil Industry Effluents in Greece. Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1886 2024, 16, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.; Forster, C.F. A Study of the Operation of Mesophilic and Thermophilic Anaerobic Filters Treating a Synthetic Coffee Waste. Bioresour Technol 1993, 45, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, W.; Carnaje, N.P.; Cord-Ruwisch, R. Methane Conversion Efficiency as a Simple Control Parameter for an Anaerobic Digester at High Loading Rates. Water Science and Technology 2011, 64, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, S.; Bernet, N.; Buffière, P.; Roustan, M.; Moletta, R. Methane Yield as a Monitoring Parameter for the Start-up of Anaerobic Fixed Film Reactors. Water Res 2002, 36, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022.

- Kapdan, I.K. Kinetic Analysis of Dyestuff and COD Removal from Synthetic Wastewater in an Anaerobic Packed Column Reactor. Process Biochemistry 2005, 40, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, P.; Dohányos, M.; Chudoba, J. Kinetics of Multicomponent Substrate Removal by Activated Sludge. Water Res 1975, 9, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W. .; Southard, M.Z. Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg, D.J.; Teke, G.M.; Görgens, J.F.; van Rensburg, E. Predicting Commercial-Scale Anaerobic Digestion Using Biomethane Potential. Renew Energy 2024, 235, 121304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulsido, M.D.; Dinigu, F.B.; Berego, Y.S. Uncovering the Effect of Multiple Wet Coffee Processing Industries’ Effluents on River Water Quality Parameters. Environ Forensics 2025, 26, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenafi Hailemariam, F.; Velmurugan, P.; Selvaraj, S.K. Treatment of Wastewater from Coffee (Coffea Arebica) Industries Using Mixed Culture Pseudomonas Florescence and Escherichia Coli Bacteria. Mater Today Proc 2021, 46, 7396–7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novita, E. Biodegradability Simulation of Coffee Wastewater Using Instant Coffee. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2016, 9, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Mendoza, R.; Castillo-Rivera, M.F. Start-up of an Anaerobic Hybrid (UASB/Filter) Reactor Treating Wastewater from a Coffee Processing Plant. Anaerobe 1998, 4, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsdale, R.M.; Hawkes, F.R.; Hawkes, D.L. The Mesophilic and Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Coffee Waste Containing Coffee Grounds. Water Res 1996, 30, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchala, K.R.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.W. Anaerobic Digestion Modelling. Advances in Bioenergy 2017, 2, 69–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, S.C.; Okonkwo, P.C. Substrate Reduction Kinetics and Performance Evaluation of Fluidized-Bed Reactor for Treatment of Brewery Wastewater. Nigerian Journal of Technology 2016, 35, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumantri, I.; Budiyono, B.; Purwanto, P. Kinetic Study of Anaerobic Digestion of Ketchup Industry Wastewater in a Three-Stages Anaerobic Baffled Reactor (ABR). 2019. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Gasca, E.; López-López, A. Kinetics of Organic Matter Degradation in an Upflow Anaerobic Filter Using Slaughterhouse Wastewater. J Bioremed Biodegrad 2010, 1, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, G.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Shah, A.; et al. Reactor Performance and Economic Evaluation of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Dairy Manure with Corn Stover and Tomato Residues under Liquid, Hemi-Solid, and Solid State Conditions. Bioresour Technol 2018, 270, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.; Li, G. Anaerobic Digestion of Different Agricultural Wastes: A Techno-Economic Assessment. Bioresour Technol 2020, 315, 123836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainardis, M.; Flaibani, S.; Mazzolini, F.; Peressotti, A.; Goi, D. Techno-Economic Analysis of Anaerobic Digestion Implementation in Small Italian Breweries and Evaluation of Biochar and Granular Activated Carbon Addition Effect on Methane Yield. J Environ Chem Eng 2019, 7, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabil, M.R.; Laurent, J.; Casellas, M.; Dagot, C. Techno-Economic Evaluation of Thermal Treatment, Ozonation and Sonication for the Reduction of Wastewater Biomass Volume before Aerobic or Anaerobic Digestion. J Hazard Mater 2010, 174, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Castellucci, S.; Villarini, M.; Colantoni, A. An Economical Evaluation of Anaerobic Digestion Plants Fed with Organic Agro-Industrial Waste. Energies 2017, Vol. 10, Page 1165 2017, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unver, O.; Bhaduri, A.; Hoogeveen, J. Water-Use Efficiency and Productivity Improvements towards a Sustainable Pathway for Meeting Future Water Demand. Water Secur 2017, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanham, D.; Mekonnen, M.M. The Scarcity-Weighted Water Footprint Provides Unreliable Water Sustainability Scoring. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 756, 143992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safieddin Ardebili, S.M. Green Electricity Generation Potential from Biogas Produced by Anaerobic Digestion of Farm Animal Waste and Agriculture Residues in Iran. Renew Energy 2020, 154, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Zeng, C.; Lian, X.; Xia, Z.; Zou, J. Research on Methane-Rich Biogas Production Technology by Anaerobic Digestion Under Carbon Neutrality: A Review. Sustainability 2025, Vol. 17, Page 1425 2025, 17, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonov, I.; Chorukova, E.; Kabaivanova, L. Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion for Green Energy Production: A Review. Processes 2025, Vol. 13, Page 294 2025, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).