Background

The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) plays a critical role in supporting the survival of preterm infants through advanced medical interventions and technology designed to support physiological processes (Séassau et al., 2023). However, despite its lifesaving benefits, the NICU environment can be highly stressful for both infants and their parents (Shaw et al., 2023). Parents often experience elevated levels of anxiety and emotional distress due to the uncertainty of their infant’s condition, compounded by the unfamiliar and clinical nature of the NICU setting (Séassau et al., 2023; Voulgaridou et al., 2023).

Preterm birth interrupts the natural developmental process, removing the infant from the protective intrauterine environment and the physiological regulation typically provided by the mother (Givrad et al., 2020). This early separation can disrupt the development of the parent-infant bond and interfere with co-regulation mechanisms vital for emotional and neurological development (Naeem et al., 2022; Zanta et al., 2023).

Parental education is an important potential intervention strategy to mitigate these challenges (Springer et al., 2023). Increasing parents’ understanding of preterm infant behaviour helps them interpret their infant’s cues, respond more effectively, and reduce feelings of helplessness and anxiety (Kim & Kim, 2022; Quiñones-Preciado et al., 2023; Séassau et al., 2023). Knowledge about developmental needs, stress signals, and caregiving techniques, such as appropriate positioning, comfort strategies, and recognising signs of overstimulation, can foster emotional resilience, counter feelings of isolation, support realistic expectations, and empower parents to respond in a nurturing and active manner (Givrad et al., 2020; Hendricks, 2021; Kristiawati et al., 2020; Möller et al., 2019; Polizzi et al., 2021; Séassau et al., 2023).

Parental education not only benefits parents but may also have a positive impact on their infants (Baker & McGrath, 2011; Jiang et al., 2014; Loewenstein et al., 2021; Mosher, 2017). Informed and engaged parents are more likely to adopt and sustain positive caregiving behaviours, including kangaroo care and responsive interactions. These practices are crucial for the healthy emotional and neurological development of the infant (Arzani et al., 2023; Carozza & Leong, 2021; Miller & Commons, 2010). They also enhance bonding (Jiang et al., 2014; Melançon et al., 2020), improve sleep regulation and quality (Campbell--Yeo et al., 2015; Norholt, 2020) and support overall brain development in preterm infants (Arzani et al., 2023; Norholt, 2020). With knowledge about infant behaviour and development, parents are better equipped to implement care techniques that support co-regulation, contributing to their infant’s physical and neurological growth (Bastani et al., 2024).

Evidence-based parenting educational programmes grounded in family-centred care (FCC) have demonstrated positive outcomes for both infants and parents (Pineda et al., 2017). Notable examples include the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) program (Melnyk et al., 2006) and the Alberta Family Integrated Care (FICare) psychoeducational intervention (Benzies et al., 2020). Building on this foundation, the NeuroSense PremmieEd Parenting Educational Programme was developed in South Africa. This programme draws on global literature and qualitative data from mothers of preterm infants within a selected context of the South African public healthcare sector, to support contextual relevance.

The study was conducted at two public-sector, referral hospitals located in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District of South Africa’s North West province, a semi-urban region where residents often move between rural and urban areas to access healthcare services, making use of public and private providers. The selected hospitals provide similar services with hospital A’s neonatal unit comprising 8 NICU beds, 9 high-care beds and 28 low-care beds, admitting an average of 66 neonates per month (University of the Witwatersrand, 2023). Hospital B is a regional hospital with 6 NICU beds, 10 high care and 4 low care (kangaroo-mother-care) beds. Both units provide care for very low birthweight preterm infants (from 24 weeks’ gestation), late preterm infants, and high-risk full-term neonates.

This manuscript presents the pilot implementation of the NeuroSense PremmieEd Parenting Educational Programme in tertiary-level NICUs in the North West province of South Africa. The larger study aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the programme. This paper reports on the preliminary impact of the educational programme on parental knowledge and stress using a sequential cohort design.

Study Aim

This study aimed to pilot a contextually relevant parenting educational programme to enhance parental understanding of preterm infant behaviour, strengthen parents’ capacity to interpret and respond sensitively to infant cues, and reduce parental stress during NICU admission.

Methods

Design

Informed by the frameworks of Kleberg et al. (2007) and Browne and Talmi (2005), the study employed a sequential cohort design comprising three arms: standard care, booklet-only, and full intervention.

Recruitment of Participants

Following ethical approval, a research assistant approached mothers with NICU babies that were stable and older than 24 hours. The assistant explained the study, provided an information brochure and a copy of the informed consent document, and addressed any questions. Mothers who agreed to participate signed informed consent and completed the biographical and other assessment questionnaires, as soon as possible after enrolment.

Inclusion Criteria

Mothers were eligible if the infant(s) were inborn, singleton or multiple, born before 37 weeks gestation (≤36 weeks, 6 days) and expected to remain in the NICU for at least seven days. Mothers were enrolled at least 24 hours postnatally. No fathers were actively involved in these units and were therefore not involved in this pilot. In cases of infant death, mothers could choose to remain enrolled or withdraw from the study. Eligible mothers were 18 years or older, provided written informed consent, and were proficient in at least one of the local languages: English, Setswana, or Afrikaans.

Exclusion Criteria

Teen mothers under 18 years of age were excluded due to their unique parenting needs. Infants with major malformations or conditions that required surgery were also excluded. Additionally, parents with a history of drug addiction, psychosis, or severe mental illness (self-reported) were not eligible.

Sample Size

The sample goal of 30 participants (10 in each group) per hospital was pre-determined based on previous comparable studies (Browne & Talmi, 2005; Kleberg et al., 2007). Kleberg and colleagues in their study enrolled 10 mothers each in the control and experimental groups comparing mothers’ attitudes and apprehension of their maternal role, perception of their infant and the neonatal care when receiving the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) intervention versus no intervention (a pilot study). Browne and Talmi (2005), on the other hand, included 84 high-risk mother-infant dyads which were randomly assigned to two intervention and one control groups (full randomised controlled trial). In their study, they examined how family-based interventions in the NICU change parental knowledge and behaviours and decrease stress. We recruited 20 participants (10 per hospital) in each of the three arms (n = 60) to determine feasibility.

Procedures and Data Collection

Measures

Demographics and Clinical Descriptive Data

Biographical data were collected from the mothers, through self-administered questionnaires. Parental variables included marital status, parity, gravidity, age, ethnicity, pregnancy and birth history, type of delivery, and educational level (see

Table 1: Biographical ). Infant characteristics included gestational age, birth weight and size, head circumference at birth, APGAR, and gender (Kleberg et al., 2007).

The Knowledge of Preterm Infant Behaviour Scale (KPIB) (Browne & Talmi, 2005) uses 36 multiple-choice questions to elicit parents’ knowledge of their preterm infant in two domains of infant behaviour: 1) knowledge of infant reflexes, physical responses to stimuli, motor activity, sleep-wake states and social interaction, and 2) parental knowledge regarding optimal interaction times and how to help develop self-regulatory mechanisms in the infant (Browne & Talmi, 2005). Measure construction and validation was described by Brown (1990). Additionally, Browne and Talmi (2005) state a split-half reliability using the Spearman Brown formula of 0.88, with odd and even items correlating at 0.79. A total score was calculated for each participant, and the pre-test and post-test scores were compared to determine if knowledge changed overall. The averages for each group were compared.

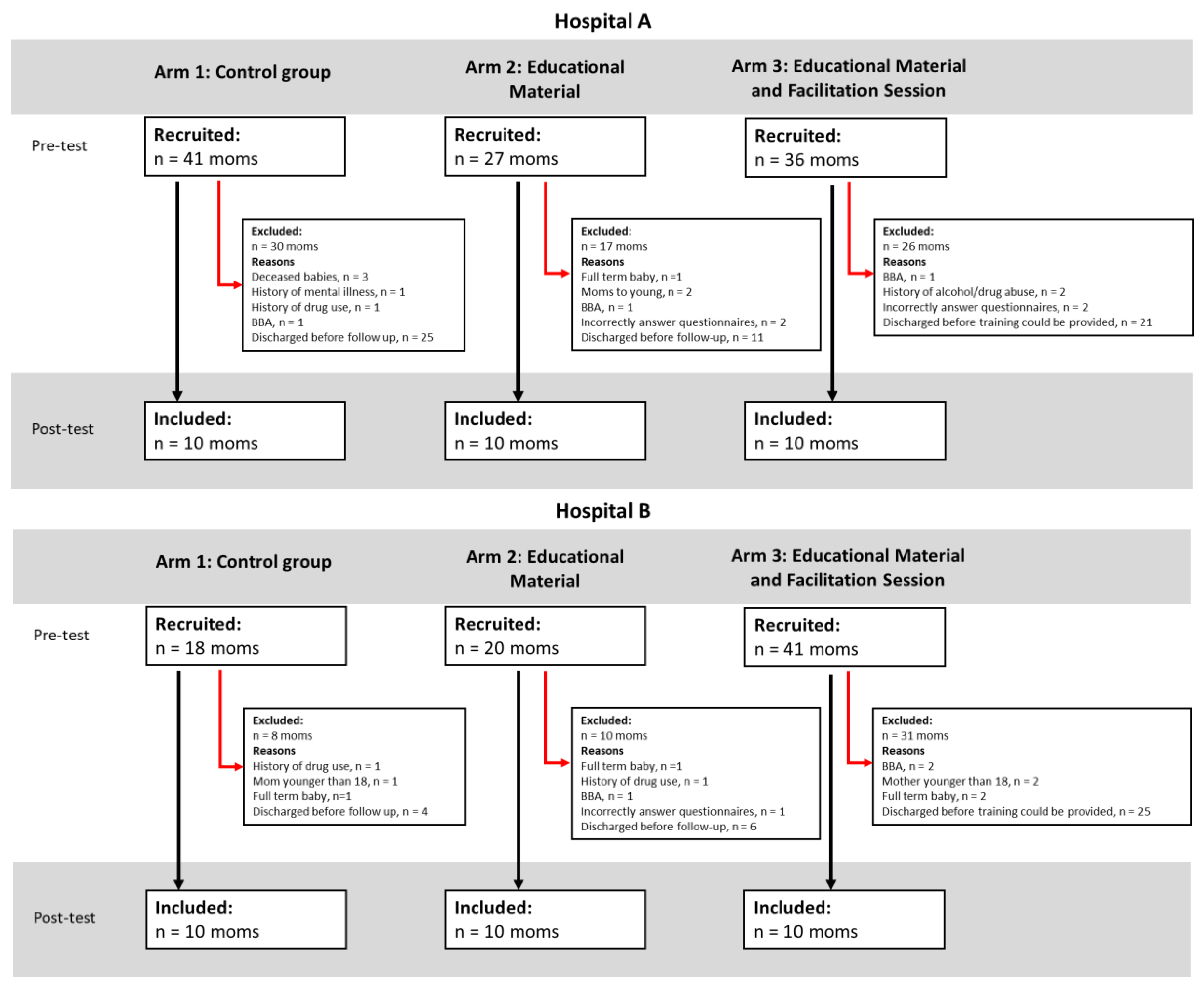

The Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PSS:NICU) (Miles et al., 1993) is a self-report questionnaire, which measures parental stress following preterm birth and the subsequent admission of the neonate to the NICU. Parents indicate how stressful they experience situations using a five-point Likert scale with ratings of 1 = not at all stressful (the experience did not cause you to feel upset, tense, or anxious), 2 = a little stressful, 3 = moderately stressful, 4 = very stressful, and 5 = extremely stressful. ‘Not applicable’ could be selected for items that parents had not experienced. The PSS:NICU includes 34 items and consists of three subscales: ‘Sights and Sound’ consisting of 5 items, ‘Parental Role Alteration’ with 14 items and ‘Looks and Behave’ of the child with 15 items (Miles et al., 1993). The scale demonstrated high test-retest reliability, where correlations ranged from 0.69 and 0.87 for subscales and the total scale, respectively. Excellent psychometric properties were shown by Ionio and colleagues (Ionio et al., 2019; Ionio et al., 2016), with Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients of mothers and fathers ranging from 0.93 to 0.98. The recruitment in this study is presented using CONSORT diagrams (see: CONSORT diagrams of recruitment).

Arm Assignment

A total of 60 mothers participated in the study. Participants were sequentially recruited into three study arms, beginning with Arm 1 (n = 20), followed by Arm 2 (n = 20), and finally Arm 3 (n = 20), with 10 mothers per arm per hospital. All participants completed a biographical questionnaire along with the KPIB and PSS:NICU tools at baseline (pre-test) and again one week later (post-test).

Arm 1: Control (Standard Care)

The control arm (n = 20) received the unit’s standard care, which typically involved incidental education or bedside guidance from staff, depending on availability. Mothers visited during scheduled feeding times and participated in basic caregiving tasks such as nappy changes, breastmilk expression, or breastfeeding, if appropriate, but did not necessarily remain with their infants between feedings. Although the physical environment remained unchanged, some elements of neurodevelopmental support (e.g., comfort during handling, kangaroo care) may have occurred spontaneously but were not promoted or restricted by the study protocol.

Arm 2: Educational Booklet

Following completion of the control arm, the second arm (n = 20) was enrolled. In addition to standard care, mothers received an educational booklet in English or Setswana (based on their preference) immediately after enrolment and completion of the biographical questionnaire and the initial measures of KPIB and PSS:NICU. The mothers had the booklet with them for at least one week before the follow-up measures were taken.

Arm 3: Booklet and In-Person Session

The final arm (n = 20) received both the educational booklet (following the pre-test measures) and a 60-minute in-person training session, led by a healthcare professional with neurodevelopmental expertise. Sessions were delivered in small groups of 2 to 4 mothers within one week of enrolment.

Data Analysis

Data were initially collected using hard copy questionnaires and captured on an Excel spreadsheet for descriptive statistical analysis. Each participant was assigned a unique identifier to facilitate matched comparisons between pre-test and post-test responses.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic data and to assess changes in knowledge and stress scores within each arm over time, as well as between the three arms. A mixed-design ANOVA (version 30) was conducted with Time (Pre, Post) as the within-subjects factor and Group (Arm 1, Arm 2 and Arm 3) as the between-subjects factor.

Ethical Considerations

The study received ethics approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (UCT-647/2021), followed by approvals from the North West Province provincial and hospital managements.

Results

Biographical data covering the characteristics of the participant and infant were self-reported and are summarised in

Table 1. A total of 60 mothers participated in the study, 30 from Hospital A and 30 from Hospital B, with 10 in each of the arms (see

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b). This was a pilot study where the sample size did not make it meaningful to conduct comparative statistics. Some mothers did withdraw during the study; reasons included infant deaths and changing infant condition, while others, particularly one mother who lost a twin, continued.

Mothers in our study where homogenous across groups with the majority of mothers having completed secondary school, 22 in Hospital A and 23 in Hospital B. A small number had post-secondary education (certificates, diplomas or degrees), with slightly higher representation in Hospital A. One participant in Hospital B had only primary school education, and one mother in each hospital did not report their education level.

Across both sites, most participants identified as single. In Hospital A, 29 out of 30 mothers were single, with only one married participant in Arm 3. In Hospital B, 24 out of 30 mothers were single, five were married (primarily in Arms 1 and 2), and one mother in Arm 1 was separated. Maternal age ranged from 18 to 45 years in Hospital A and 20 to 43 years in Hospital B. The mean maternal age in Hospital A (M = 30.3, SD = 7.0) and Hospital B (M = 29.7, SD = 6.9) were similar. Arm 3 in Hospital B had the youngest mean age (26.4 years), while Arm 2 in Hospital B had the highest (31.5 years).

Mothers in both hospitals reported a similar number of pregnancies on average (M = 3.0, SD = 1.7) in Hospital A and (M = 2.7, SD = 0.9) in Hospital B. The number of pregnancies ranged from 1 to 8 or 9. Ethnically, the majority of participants identified as African. In Hospital A, all mothers were African, while in Hospital B, 28 were African, with one mother identifying as Coloured and one as White. Language preference was not reported, but 47 participants requested English informed consent forms, 13 Setswana and none requested Afrikaans.

Regarding pregnancy history, 19 mothers in Hospital A reported no complications compared to 13 in Hospital B. High blood pressure was the most frequently reported complication in both hospitals, five mothers in Hospital A and seven in Hospital B. Foetal distress was reported by three mothers at Hospital A and 4 mothers at Hospital B, while bleeding was only mentioned in Hospital A, and a wider range of “other” complications (e.g., unspecified issues) was reported in Hospital B. One mother in each hospital did not report pregnancy history.

Emergency caesarean section was the most common mode of delivery in both hospitals, with 12 reported in Hospital A and 17 in Hospital B. Vaginal deliveries were more common in Hospital A (n = 15) than in Hospital B (n = 10). Planned caesarean deliveries were infrequent and evenly distributed across arms at both sites.

Singleton births were most common, reported by 25 mothers in Hospital A and 25 in Hospital B. Twin births occurred in each hospital (n = 5 in each), most frequently in Arms 2 and 3.

Infant Characteristics

A total of 68 preterm infants were included in the study, 34 from each site. At Hospital A, the infants were distributed across Arm 1 (n = 11), Arm 2 (n = 11) and Arm 3 (n = 12), while Hospital B included 11 infants in Arm 1, 12 in Arm 2 and 11 in Arm 3.

Gestational age in both hospitals ranged from 24 to 36 weeks. Hospital A had a wider range, with a minimum gestational age of 24 weeks, while Hospital B ranged from 26 to 36 weeks. The mean gestational age was similar in Hospital A (30.1 weeks, SD = 2.7) compared to Hospital B (30.4 weeks, SD = 2.6). Infants in Arm 3 of Hospital A had the highest average gestational age (31 weeks), while Arm 1 had the lowest (29.2 weeks). In Hospital B, Arm 2 had the highest average (32.6 weeks), while both Arm 1 and 3 had a lower means of 30.4 weeks.

Birth weights ranged from 705g to 2500g in Hospital A and from 730g to 2390g in Hospital B. The mean birth weight was higher in Hospital A (1402g, SD = 380) compared to Hospital B (1300g, SD = 428). Infants in Arm 3 of Hospital A had the highest average birth weight (1537g), while those in Arm 3 of Hospital B had the lowest (1185g).

Head circumference data were more complete in Hospital A than in Hospital B, which had a large number of missing values (n = 27). Among the available data, head circumference in Hospital A ranged from 23 to 37 cm, with a mean of 27.9 cm (SD = 3.0). In Hospital B, the mean head circumference for infants in Arm 2 was 31.5 cm (SD = 3.5). Data were not available for Arm 3 in Hospital B.

Apgar scores at one minute varied widely. In Hospital A, scores ranged from 2 to 9, with a mean of 6.9 (SD = 2.1), while in Hospital B, the scores ranged from 0 to 9, with a slightly higher mean of 7.4 (SD = 2.6). Notably, Hospital A had more missing data for Arm 3. At five minutes, Apgar scores improved overall, ranging from 6 to 10 in Hospital A (mean = 8.5, SD = 1.1) and from 0 to 10 in Hospital B (mean = 8.3, SD = 2.3). Again, data were missing for several infants, particularly in Hospital A (n = 10) as this was self-reported data which mothers did not seem to have accurate knowledge of.

Regarding infant sex, both hospitals had a relatively balanced distribution. In Hospital A, 14 infants were male and 20 were female, while in Hospital B, 16 were male and 18 were female. Each study arm had a relatively even distribution of male and female infants.

Table 2.

Biographical data of participants—comparative statistics between arms and hospitals (infants).

Table 2.

Biographical data of participants—comparative statistics between arms and hospitals (infants).

| Infants |

| |

Hospital A |

Hospital B |

| Variable |

Arm 1

(n = 11)

|

Arm 2

(n = 11)

|

Arm 3

(n = 12)

|

Total

(n = 34)

|

Arm 1

(n = 11)

|

Arm 2

(n = 12)

|

Arm 3

(n = 11)

|

Total

(n = 34)

|

| Gestational Age (weeks) |

| Min |

24 |

26 |

26 |

24 |

26 |

31 |

27 |

26 |

| Max |

33 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

36 |

35 |

36 |

| Mean |

29.2 |

30.1 |

31 |

30.1 |

30.4 |

32.556 |

30.4 |

31.069 |

| Standard Deviation |

2.486 |

2.85 |

2.582 |

2.657 |

2.591 |

1.740 |

2.875 |

2.590 |

| Birth weight (in grams) |

| Min |

950 |

705 |

1020 |

705 |

730 |

1060 |

760 |

730 |

| Max |

1690 |

2500 |

2500 |

2500 |

1700 |

2200 |

2390 |

2390 |

| Mean |

1275 |

1383 |

1537 |

1402 |

1224 |

1465 |

1185 |

1300 |

| Standard deviation |

210 |

470 |

393 |

380 |

311 |

323 |

599 |

428 |

| Head circumference (in cm) |

| Min |

23 |

23 |

24 |

23 |

23 |

29 |

- |

23 |

| Max |

29.5 |

37 |

33 |

37 |

30 |

34 |

- |

34 |

| Mean |

27.363 |

28.714 |

27.857 |

27.88 |

27.4 |

31.5 |

- |

28.571 |

| Standard Deviation |

1.9 |

4.31 |

3.338 |

2.981 |

2.702 |

3.536 |

- |

3.309 |

| Missing Values |

- |

4 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

10 |

11 |

27 |

| Apgar (1 min) |

| Min |

2 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| Max |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

| Mean |

6.556 |

6.75 |

7.667 |

6.913 |

7.454 |

7.5 |

7.143 |

7.4 |

| Standard Deviation |

2.79 |

1.91 |

1.033 |

2.109 |

2.77 |

2.28 |

3.237 |

2.608 |

| Missing Values |

1 |

3 |

5 |

9 |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

| Apgar (5 min) |

| Min |

6 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

| Max |

9 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

| Mean |

8.625 |

8.125 |

8.833 |

8.5 |

8.364 |

8.583 |

7.86 |

8.33 |

| Standard deviation |

1.06 |

1.46 |

0.753 |

1.144 |

1.689 |

2.065 |

3.485 |

2.279 |

| Missing values |

2 |

3 |

5 |

10 |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

| Sex |

| Male |

3 |

5 |

6 |

14 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

16 |

| Female |

8 |

6 |

6 |

20 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

18 |

KPIB Results

Knowledge scores measured with the KPIB tool showed a trend toward improvement across all groups. In Hospital A, pre-test scores ranged from 9.9 to 11.8, with post-test scores improving slightly, particularly in Arm 3. In Hospital B, pre-test scores ranged from 12.1 to 12.5, with modest gains observed post-intervention. However, the main effect of Time was not statistically significant (p = .176), and no significant group differences or interactions were detected. While changes were small, the upward trend suggests potential value in evaluating this intervention in a larger trial.

The Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PSS:NICU)

Parental stress levels measured using the PSS:NICU tool (out of 170) showed variability across groups at baseline, with the highest stress in Arm 1 of Hospital A (M = 128.7, 76%) and the lowest in Arm 1 of Hospital B (M = 88.3, 52%). Across all groups, stress increased significantly from pre- to post-test (F(1, 57) = 8.40, p = .005), although the effect size was small (Cohen’s d = 0.13). The magnitude of increase was smallest in Arm 3, suggesting a relative buffering effect, but differences between groups were not statistically significant. The overall rise in stress likely reflects the cumulative burden of prolonged NICU exposure, including infant health concerns, environmental stressors, and the demands of acquiring new caregiving knowledge and skills.

Table 3.

Summary of pre-test, post-test scores for KPIB and NICU: PSS.

Table 3.

Summary of pre-test, post-test scores for KPIB and NICU: PSS.

| |

Hospital A |

Hospital B |

Hospital A & B (pooled data) |

| Arm 1 |

Arm 2 |

Arm 3 |

Total |

Arm 1 |

Arm 2 |

Arm 3 |

Total |

Arm 1 |

Arm 2 |

Arm 3 |

Total |

| Pre-test KPIB |

| Average Score out of 36 |

11.7 |

11.8 |

9.9 |

11.1 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

12.1 |

12.4 |

12.1 |

12.15 |

11 |

11.7 |

| Average percentage |

33% |

33% |

28% |

31% |

35% |

35% |

34% |

34% |

33.61% |

33.5% |

30.56% |

32.64% |

| Post-test KPIB |

| Average Score out of 36 |

11.2 |

12.7 |

11.6 |

11.8 |

13.4 |

12.5 |

13.3 |

12.93 |

11.85 |

12.73 |

12.45 |

12.36 |

| Average percentage |

31% |

35% |

32% |

33% |

37% |

35% |

37% |

36% |

32.92% |

35.35% |

34.58% |

34.35% |

| Change between pre- and post-test (in %) |

-2% |

+2% |

+4% |

+2% |

+2% |

0% |

+3% |

+2% |

-0.69% |

+1.85% |

+4.02% |

+1.71% |

| Pre-test NICU:PSS |

| Average Score out of 170 |

128.7 |

112.6 |

99.1 |

113.5 |

88.3 |

101.9 |

104.2 |

98.13 |

108.50 |

107.25 |

101.65 |

105.81 |

| Average percentage |

76% |

66% |

58% |

67% |

52% |

60% |

61% |

58% |

63.82% |

63.09% |

59.79% |

62.24% |

| Post-test NICU:PSS |

| Average Score out of 170 |

119.9 |

121.5 |

105.3 |

115.6 |

113.6 |

130 |

110.6 |

118.07 |

116.75 |

125.75 |

107.95 |

116.84 |

| Average percentage |

71% |

71% |

62% |

68% |

67% |

76% |

65% |

69% |

68.68% |

73.97% |

63.5% |

68.73% |

| Change between pre- and post-test |

-4% |

+5% |

+4% |

+1% |

+15% |

+16% |

+4% |

+11% |

+4.86% |

+10.88% |

+3.71% |

+6.49% |

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated the feasibility of implementing a contextually relevant parenting education programme in public-sector NICUs in South Africa. A sequential cohort design was used in two comparable hospitals, each following the same three-arm structure. This approach minimised the risk of contamination between arms, which was critical given that all infants within each site were admitted to shared neonatal units (Nickolls et al., 2024).

Participants in this study reported elevated maternal stress, likely shaping both their experiences and their engagement with the intervention materials. The majority of participants were single mothers (n = 53), which may have contributed to higher stress due to reduced partner support. Although socioeconomic status was not directly assessed, recruitment from public-sector hospitals likely reflects a predominance of lower-income families.

Parental stress, as measured by the PSS:NICU, increased across the sample from pre- to post-test, regardless of whether parents received standard care or an educational intervention. Subscale analyses indicated that most increases were driven by perceptions of environmental stressors and infant condition, while stress related to the parental role remained relatively stable across arms. These findings highlight how emotional and physical demands in a high-intensity NICU setting may limit parents’ readiness to engage with educational content, consistent with prior research (Franck et al., 2023; Milgrom et al., 2019; Urizar et al., 2021).

Parental knowledge gains appeared greatest in Arm 3, where parents received both the educational booklet and a facilitated session, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. This trend aligns with previous research suggesting that facilitated interactive learning formats are more effective than passive information delivery in helping parents understand and interpret preterm infant behaviour (Browne & Talmi, 2005; Aboud et al., 2023; Kristensen et al., 2020). Although the absolute gains in knowledge were small in this study, over and above the limited sample size, this outcome may also reflect the limitations of a brief intervention delivered in a highly stressful NICU context. Learning under stress can be particularly challenging, as stress impairs memory and cognitive flexibility and may contribute to self-doubt or guilt (Ünal et al., 2023). The modest improvements observed are consistent with this dynamic and underscore the importance of considering emotional readiness when delivering NICU-based education.

Most births in this study were emergency caesarean sections, followed by vaginal and planned caesarean deliveries. Emergency births, often associated with maternal complications such as hypertension, may heighten maternal stress and reduce receptiveness to education (de Góes Salvetti et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2015). Although birth trauma was not formally assessed, it is likely a relevant factor influencing maternal emotional states and learning capacity (Black et al., 2015; Ndjomo et al., 2024).

Additional contributing factors to stress likely include infant instability, information overload, limited support at home, and financial constraints (Givrad et al., 2020; Roque et al., 2017). High PSS:NICU scores have been associated with very preterm birth, twin pregnancies, and older maternal age (Turner et al., 2015), which aligns with our sample: infants had a mean gestational age below 31 weeks, an average birthweight of 1400 g, although most were singletons but mothers averaged 30 years of age.

Several mothers reported limited access to clinical information during the pre-test phase, highlighting communication gaps within the NICU. Addressing these systemic challenges may be as critical as educational interventions for supporting parental confidence and mitigating stress.

Limitations, Challenges, and Considerations for Future Research

As a pilot study, our sample was not powered to assess whether outcomes were influenced by gestational age, infant health, maternal characteristics, or education level. Future research could stratify outcomes by gestational age or birth weight, exploring whether these factors influence parental knowledge uptake and stress. Although the majority of participants identified as Black African, they represented diverse ethno-cultural backgrounds, predominantly Setswana. This may limit the generalisability of findings for a broader regional population; particularly where cultural practices may shape parental perceptions and needs in the NICU.

Education levels ranged from secondary school to post-secondary education, with only four participants holding a degree. This supports the tailoring of educational content to secondary-level literacy for future interventions.

Some data were missing due to incomplete maternal recall, particularly for variables such as Apgar scores and head circumference measurements, where up to 25 values were missing in the combined sample. Access to infant medical records in future studies would help strengthen data completeness and accuracy. Analysis of neonatal profiles revealed that infants in Arm 1 were generally more clinically fragile in Hospital A, but the same for Arm 1 and 3 in Hospital B, with the lowest average gestational age (M = 29.2 weeks in Hospital A and 30.4 weeks in Hospital B) and lowest average birthweight (mean = 1275 g and 1185 g, respectively). Arm 2 showed the widest variation in gestational age (26–35 weeks) and birth weight (705–2500 g), suggesting greater heterogeneity in infant condition. Arm 3 was similar in neonatal characteristics overall, with the average gestational ages (31.0 and 30.4 weeks in Hospital A and B respectively) and average birthweight (1537 g and 1185 g, respectively).

These differences may have influenced maternal engagement and post-test follow-up feasibility. For example, infants in Arm 3 in Hospital A and Arm 2 in Hospital B were generally more stable and discharged earlier, limiting opportunities for post-intervention data collection. In contrast, the higher acuity (based on lower gestation and birthweight) of infants in Arm 1 may have contributed to increased maternal stress and reduced capacity for engagement during the intervention period. Understanding how infant clinical status affects parental readiness to participate in educational programmes is important for the design of future interventions.

Some anecdotal data were collected during the course of the study and may inform the planning of future studies. Recruitment and retention barriers were evident in our study. Although pre-test participation was high, post-test follow-up was hampered by early discharges, distance from the hospital, and financial or logistical constraints. Recruitment was also affected by social dynamics—on some days, a “leader mom” discouraged others from enrolling, underscoring the importance of individual-level engagement strategies in future trials.

Mothers faced systemic barriers such as transport issues and limited capacity to remain in the hospital after delivery. Mistrust in healthcare systems and the varying levels of health literacy also presented challenges. Building culturally appropriate, trust-based educational relationships is crucial for future success.

Although care was taken to simplify the language, many mothers struggled to articulate their observations and required assistance. The KPIB tool was time-consuming, sometimes leading to participant fatigue or dropout. Simplified or visual-based tools could enhance comprehension and completion. Incorporating infant clinical data directly from patient records would improve accuracy and reduce reliance on maternal recall. Both the KPIB and PSS: NICU tools were only available in English; however, translation services were available to mothers, which were only used for translation to Setswana.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

To refine and scale parenting educational interventions in the NICU, this pilot study highlights several key areas for development based on observed operational challenges and participant responses.

First, it is critical to stratify educational content by gestational age, maternal experience, and literacy levels. In our study, a standardised intervention was applied across all mothers, yet observed feedback and engagement levels suggested that first-time mothers, those with extremely preterm infants, and mothers with lower literacy levels engaged differently with the material. Tailoring content would allow for more targeted and meaningful learning, potentially improving both knowledge acquisition and confidence.

Second, the study was conducted in two hospitals serving semi-urban populations, but with some demographic and cultural homogeneity. For a broader applicability, future iterations should include more diverse cultural and socioeconomic groups. This is especially relevant in South Africa’s public healthcare sector, where linguistic, cultural, and resource disparities can influence how health information is received and acted upon.

The importance of tracking how parental knowledge and stress evolve over time became apparent during follow-up attempts post-discharge. Although some knowledge gains were observed immediately after the intervention, the sustainability of these gains and their long-term impact on maternal stress remain unclear. Ongoing measurement beyond the NICU stay would provide a clearer picture of the intervention’s effectiveness over time and support continuity of care into the home setting.

Additionally, the severity of the infant’s illness, as well as the length of stay, appeared to shape the amount of attention and emotional capacity mothers could devote to the intervention. For example, mothers of critically ill infants and mothers who have been in the NICU for longer periods often expressed higher levels of stress and exhaustion and struggled to fully engage with educational content. Future studies should explore illness severity and length of stay as a possible moderator of intervention effectiveness to help personalise delivery and timing.

Our experience with the current assessment tools also pointed to a need for refinement. Some mothers found the knowledge questionnaire dense or abstract, especially those with lower health literacy or less fluency in English. Furthermore, given the high and increasing maternal stress levels observed, future iterations of the intervention could expand components that support stress management and provide greater psychosocial support. More visually engaging, simplified, and culturally contextualised tools may improve the quality of data collected in the future. Additionally, the questionnaire could become a tool to help mothers understand the behaviours of their infants, rather than information that contributes to anxiety.

Lastly, the value of real-time embedded support became clear, especially in the intervention arm where structured sessions were delivered. Mothers frequently expressed appreciation for the relational and practical support they received during these sessions, an element absent from the booklet-only arm. Embedding such support into routine care, particularly in resource-constrained environments, could increase the accessibility and sustained impact of the intervention without requiring large-scale resource additions.

Together, these insights underline the importance of responsive, inclusive, and contextually grounded strategies for delivering parenting education in the NICU, especially within the constraints and realities of public-sector healthcare in middle-income countries.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that structured educational interventions, particularly those combined with facilitated sessions, have the potential to enhance maternal knowledge during the critical NICU period. Although parental stress increased across all groups over time, the facilitated intervention was associated with a smaller rise in stress, indicating its potential to support early parenting, promote infant development, and mitigate long-term parental anxiety. This study provides foundational insights into parenting education in a public South African NICU and emphasises the need for accessible, culturally relevant, and well-supported interventions. Future work should focus on scaling this approach, optimising delivery, and evaluating long-term outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in conceptualising the study, revising the manuscript, and interpreting the results. WL conceptualised the paper and prepared the manuscript. WL did the technical preparation. KD was responsible for study supervision and critical review. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The larger project in which this study is nested was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (UCT- 647/2021) on 10 November 2021, with subsequent renewal of ethical approval on 7 August 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The intervention materials (e.g., programme content, handouts, facilitator guidelines) are not publicly available due to copyright and ongoing development. However, they can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request for academic or implementation purposes.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

In the course of preparing this manuscript, the authors made use of ChatGPT and Jenni AI to enhance the coherence and grammatical accuracy of the text. Following the use of these tools, the authors conducted a thorough review and made necessary amendments, thereby assuming full responsibility for the final content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs Jessica Botha for her valuable input into the review, language editing and technical preparation of this article. We would also like to thank Ms Juleen Ras and Mrs Danita Kruger for their input in statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasinia, N.; Rad, Z.A.; Qalehsari, M.Q.; Gholinia, H.; Arzani, A. The effect of instructing mothers in attachment behaviors on short-term health outcomes of premature infants in NICU. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 2023, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, F.E.; Choden, K.; Tusiimi, M.; Gómez, R.; Hatch, R.; Dang, S.; Betancourt, T.S.; Dyenka, K.; Umulisa, G.; Omoeva, C. A tale of two programs for parents of young children: Independently-conducted case studies of workforce contributions to scale in Bhutan and Rwanda. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, K.; Haque, M.; Khatoon, S. Kangaroo Mother Care: A simple method to care for low-birth-weight infants in developing countries. Journal of Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College 2013, 5, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.J.; McGrath, J. Parent education: The cornerstone of excellent neonatal nursing care. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews 2011, 11, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, F.; Rajai, N.; Farsi, Z.; Als, H. The effects of kangaroo care on the sleep and wake states of preterm infants. Journal of Nursing Research 2017, 25, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.E.; Devereux, P.J.; Salvanes, K.G. Does grief transfer across generations? Bereavements during pregnancy and child outcomes. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2016, 8, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.; Staniszewska, S.; Newburn, M.; Jones, N.; Taylor, L. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open 2011, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.V.; Talmi, A. Family-based intervention to enhance infant–parent relationships in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2005, 30, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Yeo, M.L.; Disher, T.C.; Benoit, B.L.; Johnston, C.C. Understanding kangaroo care and its benefits to preterm infants. Pediatric Health Medicine and Therapeutics 2015, 6, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozza, S.; Leong, V. The role of affectionate caregiver touch in early neurodevelopment and parent–infant interactional synchrony. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. (3rd ed.). Sage.

- de Góes Salvetti, M.; Lauretti, L.G.; Muniz, R.C.; Dias, T.Y.S.F.; Gomes de Oliveira, A.A.D.; Gouveia, L.M.R. Characteristics of pregnant women at risk and relationship with type of delivery and complications. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 2021, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.S.; Gay, C.; Hoffmann, T.J.; Kriz, R.M.; Bisgaard, R.; Cormier, D.M.; Joe, P.; Lothe, B.; Sun, Y. Maternal mental health after infant discharge: A quasi-experimental clinical trial of family integrated care versus family-centered care for preterm infants in U.S. NICUs. BMC Pediatrics 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givrad, S.; Dowtin, L.L.; Scala, M.; Hall, S.L. Recognizing and mitigating infant distress in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Journal of Neonatal Nursing 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, M.R. How a frightened mother of a preterm newborn eventually flourished. Nursing for Women’s Health 2021, 25, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Warre, R.; Qiu, X.; O’Brien, K.; Lee, S.K. Parents as practitioners in preterm care. Early Human Development 2014, 90, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, A.R. Attachment- and relationship-based interventions during NICU hospitalization for families with preterm/low-birth weight infants: A systematic review of RCT data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, I.H.; Juul, S.; Kronborg, H. What are the effects of supporting early parenting by newborn behavioral observations (NBO)? A cluster randomised trial. BMC Psychology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiawati, K.; Rustina, Y.; Budi, I.B.; Hariyati Rr, T.S. How to prepare your preterm baby before discharge. Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health 2020, 49, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, K.; Barroso, J.; Phillips, S. The experiences of parent dyads in the neonatal intensive care unit: A qualitative description. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2021, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melançon, J.; Aita, M.; Belzile, S.; Lavallée, A. Clinical intervention involving parents in their preterm infant’s care to promote parental sensitivity: A case study. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 2020, 27, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, J.; Martin, P.R.; Newnham, C.; Holt, C.J.; Anderson, P.J.; Hunt, R.W.; Reece, J.; Ferretti, C.; Achenbach, T.; Gemmill, A.W. Behavioural and cognitive outcomes following an early stress-reduction intervention for very preterm and extremely preterm infants. Pediatric Research 2019, 86, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.M.; Commons, M.L. The benefits of attachment parenting for infants and children: A behavioral developmental view. Behavioral Development Bulletin 2010, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, E.L.; de Vente, W.; Rodenburg, R. Infant crying and the calming response: Parental versus mechanical soothing using swaddling, sound, and movement. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosher, S.L. Comprehensive NICU parental education: Beyond baby basics. Neonatal Network 2017, 36, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, N.; Zanca, R.M.; Weinstein, S.; Urquieta, A.; Sosa, A.; Yu, B.; Sullivan, R.M. The neurobiology of infant attachment-trauma and disruption of parent–infant interactions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2022, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjomo, G.; Njiengwe, E.; Moudze, B.; Guifo, O.; Blairy, S. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression in mothers after preterm delivery and the associated psychological processes. Research Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickolls, B.J.; Relton, C.; Hemkens, L.; Zwarenstein, M.; Eldridge, S.; McCall, S.J.; Griffin, X.L.; Sohanpal, R.; Verkooijen, H.M.; Maguire, J.L.; McCord, K.A. Randomised trials conducted using cohorts: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e075601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norholt, H. Revisiting the roots of attachment: A review of the biological and psychological effects of maternal skin-to-skin contact and carrying of full-term infants. Infant Behavior and Development 2020, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, R.; Bender, J.; Hall, B.; Shabosky, L.; Annecca, A.; Smith, J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Human Development 2018, 117, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, C.; Perricone, G.; Morales, M.R.; Burgio, S. A study of maternal competence in preterm birth condition, during the transition from hospital to home: An early intervention program’s proposal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Preciado, J.A.; Peña-García, Á.A.; Vallecilla-Zambrano, D.G.; Yama-Oviedo, J.A.; Hernández-Gutiérrez, N.L.; Ordoñez-Hernández, C.A. Strategies and educational needs of parents of premature infants in a third level hospital in Cali, Colombia. Interface 2023, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, U.M.; Rice, M.M.; Grobman, W.A.; Bailit, J.L.; Wapner, R.J.; Varner, M.W.; Thorp, J.M.; Leveno, K.J.; Caritis, S.N.; Prasad, M.; Tita, A.T.N.; Saade, G.R.; Sorokin, Y.; Rouse, D.J.; Blackwell, S.C.; Tolosa, J.E. Serious maternal complications after early preterm delivery (24–33 weeks’ gestation). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, A.T.F.; Lasiuk, G.C.; Radünz, V.; Hegadoren, K. Scoping Review of the Mental Health of Parents of Infants in the NICU. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 2017, 46, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séassau, A.; Munos, P.; Gire, C.; Tosello, B.; Carchon, I. Neonatal care unit interventions on preterm development. Children 2023, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.J.; Givrad, S.; Poe, C.; Loi, E.C.; Hoge, M.K.; Scala, M. Neurodevelopmental, mental health, and parenting issues in preterm infants. Children 2023, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, C.; Elleman, B.; Cooper, O. The effectiveness of parental education programs within neonatal intensive care units: A systematic review. Research Directs in Therapeutic Sciences 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H.; Stanners, M. The assessment of parental stress and support in the neonatal intensive care unit using the Parent Stress Scale—Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Women and Birth 2015, 28, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, N.; Küçükdağ, M.; Şengun, Z. Evaluation of stress levels in both parents of newborns hospitalized in the neonatal intensıve care unit. Mathews Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Witwatersrand. (2023). Admissions registers of hospital complex, prepared by nursing services manager. https://www.wits.ac.za/clinicalmed/departments/paediatrics-and-child-health/hospital-services/klerksdorp-hospital/.

- Urizar, G.G.; Nguyen, V.; Devera, J.; Saquillo, A.J.; Dunne, L.A.; Brayboy, C.; Dixon-Hamlett, A.; Clanton-Higgins, V.; Manning, G. Destined for greatness: A Family-based stress management intervention for African-American mothers and their children. Social Science & Medicine 2021, 280, 114058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaridou, A.; Paliouras, D.; Deftereos, S.; Skarentzos, K.; Tsergoula, E.; Miltsakaki, I.; Oikonomou, P.; Aggelidou, M.; Kambouri, K. Hospitalization in neonatal intensive care unit: Parental anxiety and satisfaction. The Pan African Medical Journal 2023, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO recommendations for care of the preterm or low birth weight infant. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068041.

- Zanta, N.C.; Assad, N.; Suchecki, D. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in maternal deprivation-induced behaviours relevant to psychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2023, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).