3. Results

From 16 transcripts, a total of 297 significant statements were found. The examples of significant statements and their formulated meanings are listed below (see

Table 3).

The formulated meanings were then clustered into 6 Themes and 17 sub-themes (see

Table 4).

Theme 1: That is life. Focusing on the attitudes toward WFC, most participants mentioned that the conflict between work demands and family needs is just a “part of life” and it is a “life experience” that everyone has to go through. For example, participant 4 (P4) said, “all of these [different types of WFC] are life experiences, […] it is just a very common phenomenon, I think the experience of conflict [between work and family] has actually become normalised.” On the contrary, some participants think that WFC is considered a problem that affects their lives; however, compared to other difficulties in life, it was just a minor problem that is not worth mentioning. P16 stated, “It is a problem, just not a big deal. I mean, a simple example, your work and family are actually like a scale, it is not possible to balance it easily.”

It appeared that because of such a standpoint toward WFC (i.e., just a life experience or just a minor problem in life), most of the participants tended to turn a blind eye when the WFC happened. P8 remarked, “Life goes on. So, you cry about it, then just keep moving forward.” And P1 also reported as follows:

Just don’t think about it and ignore it; it is common in every household. Maybe everyone will deal with it differently, but for me, I would just act as if nothing happened. Give it a couple of days, and everything will be okay again.

Theme 2: Part of the culture. In this theme, interviewees described the Chinese culture and beliefs associated with WFC. All the participants showed a very strong sense of family and thought that work is for the family. A strong sense of family was evident during P6’s interview; he stated,

I think if you have to stop your work because you have to provide care for your family members, I actually don’t think it is a conflict; it is just a thing that you must do for your family, it is a responsibility.

Similar responses were found during the interview with P11; he said, “Actually, things like my job are not that important if you compare them to my family. It is not even worth mentioning.” And during P3’s interview, she stated, “You can find another job, but you only have one family, so their health or other family issues are definitely more important.”

Work is for the family was endorsed by most of the participants. Work was described as a way to make money so that he/she can provide a better life for their family. P12 said, “It is a good-paying job. So even though [being a nurse] is very stressful […] still, I am willing to sacrifice because the income can give my child, or the family a better future.”

Additionally, Chinese families seem to have a more supportive and united relationship, which might ease the WFC experience from different aspects. For example, elderly parents would take care of their adult children’s or grandchildren’s daily lives and/or financially support their adult children. For example, P7, who is living with his son and husband, said,

When I need to buy a house [parents will give us money]; […] or if I have a business trip, or my husband has a business trip and I have to work, then they (parents) will come to help us [to take care of the child].

P4, who is 48 years old and living with his wife and two children, stated, “They (elderly parents) will cook for us and take care of the children for us.” When the researcher asked, “What is your thought about your parents still helping you out instead of you taking care of them?” later during the interview, he stated, “Nothing, it is good. I mean, that is the case in our Chinese families. Parents are always the providers; I think it is just a common phenomenon.”

Except for the help from elderly parents, Chinese males seem to enjoy support from female spouses, but such support seems to be one-sided. “She understands I have to work” and “She understands I am tired” were mentioned by some married male participants during the interviews. However, P12, who is a married female participant, said, “Because my husband does nothing [at home], I mean my husband, he can’t share [the housework] with me, so I feel like I have more things to do.” In other words, the male seems to receive more support and understanding from his wife, which might ease the WFC; however, on the other side, the female appears to have more WFC because of family responsibility.

It seems that such one-sided support was due to the influence of the traditional gender role; the inequality in gender roles was endorsed by most of the participants, especially among the married participants or the participants who were still living with their parents. Participants described this gender role as part of the “society”, “culture”, and “tradition”. P8, a woman with two children, said, “the society, I mean even right now, […], people still think that women should stay at home and be the caregiver; this [traditional] thought is deeply ingrained in belief.” And P14, a husband with two children, said, “the domestic chore should be done by the wife, that’s just part of our culture.”

It appeared that women would have more family responsibilities, such as providing care for the children and taking on more housework. P2, who lives with his parents and girlfriend, stated, “[housework] basically is done by my mum and my girlfriend.” P5, who is married and still living with his elderly parents, also said, “In general, my mum does most of it (housework), then my wife will finish the rest, mainly take care of the child’s daily lives.”

Subsequently, men and women seem to get used to this gender role, which leads to women having more family responsibilities and being more willing to take on more family responsibilities, thereby letting their husbands or adult children focus on the work domain. For example, P1 stated, “Sometimes I got off work very late, around 1 AM or 2 AM, she (my wife) finished all the housework, she didn’t leave any things for me to do.” And P7, who is married and has a son named N, said, “I am quite busy [at work], then my husband hopes that I could spend more time at home to help N with his homework, but I might…, so I have to take some time off [from work].” And when the researcher asked her how she felt about having more family responsibilities later during the interview, she stated,

I feel like it is just part of my life, I already get used to it […] it is always me who takes care of his (the son’s) daily life […] I, I don’t seem to feel anything anymore, I just feel like it is just my responsibility.

As a sub-theme of the part of the culture, filial piety was endorsed by all participants in this study. All the participants believed that taking care of elderly parents is a way to fulfil their obligations as children. As P12 stated, “you, as the child, must take care of them (parents), not just financially support them, but also emotionally care about them.” Although most of the participants’ parents in this study are still relatively young and in good health, the thought of having to take care of their parents when they are older has negatively affected most of the participants to some degree. P11 stated,

[Having to take care of parents] is pressure, because right now, it’s not like I am doing very well at work, still not achieving my [occupational] goal; I mean, I am not rich enough, but my parents are getting older and older, so I just feel so much pressure.

P6 explained the reason why the thought of filial piety impacted him and what he was worried about; he said,

As they (elderly parents) get older, they may start to have some health issues; then the first [thing I am worried about] is the medical treatment [needs money], second is I have to provide care, which means I have to take some time off from work, and then my income will be affected.

Theme 3: Family first and work second. In this cluster, participants described the family-related factors/experiences associated with FIW. It appeared that due to the strong sense of family, most participants claimed that the only reason they would stop their work was the health of family members. Some participants said the only thing that stopped their work was their children’s health; for example, P1, who has a 2-year-old daughter, said, “My child was suddenly sick, then I [left my work and] went back home.” P7, who has a 12-year-old son, stated, “If he (my son) feels sick, I will definitely stop everything at work and take him to the hospital.” Some said the health of their elderly parents had stopped their work. For example, P6 stated, “My parents were both ill a while ago; I stopped my job to take care of them.” And P14 stated, “if parents are sick, then I will stop everything I am doing at work […] that’s it, that’s nothing to talk about, I can lose my job, but I can’t lose my parents.”

It appeared that due to the influence of societal/cultural norms, such as “I must take care of elderly parents by myself”, being the only child would exacerbate the negative impact of filial piety on FIW. Most participants often mentioned “because I am the only child” during the question regarding taking care of elderly parents. For example, P4 stated, “Because I am the only child, will I have the ability to take care of my parents by myself when they are old? [Every time I thought about that] I started to panic, and I started to worry.” And P12 said, “If you are an only child, you probably need to take care of 8 elderly parents. Your parents, your grandparents, your spouse’s parents, and your spouse’s grandparents.” It seems that the lack of sibling support might be the reason why being the only child would exacerbate FIW. This is evident in P16’s interview:

It’s very realistic; you have to deal with it yourself, or you have a sibling to handle it all together. It won’t be the same. I mean, at least, you won’t be so stressed [if you have a sibling]. If you have many siblings, things may be much easier; at least you can discuss [with your sibling] when something happens.

As a sub-theme of the family comes first and work second, having children was endorsed by all the parent participants. All the parent participants in this study claimed that as their children become older, they have more stress in both work and family domains due to parental expectations. P1, who has a 2-year-old daughter, said, “Because you have to know that the kindergarten charges at least 1,000 RMB per month, that’s an extra pressure, so I have to walk the extra mile.” Also, P7, who signed up for 3-4 after-school classes for her son to improve his school grade, reported as follows:

First, I have to take him to and from the after-school classes, so it costs my time; then it makes me a little bit anxious because I have to make sure he absorbs the knowledge, right? So, I have to make sure he does the homework, and I have to give him other assignments to improve his weaknesses. I have to examine his work, like discuss it with him and communicate with his teacher after class. All of these are like invisible pressure.

And P12, who has two six-years-old daughters, stated,

I work like 10 hours, and then I finally get back home […] I barely have time to enjoy my dinner, my body and my mind are not ready yet, and then I have to help with my children’s homework; I just feel like I am a bit out of my depth.

The parental expectation was also linked with “good job” and “contribute to society” by most of the parent participants. For example, P7, who has a 12-year-old son, said, “I hope he can find a good but not stressful job, and of course, it is a good-paying job too. So that he can take care of himself and his own family.” And P14, who has two children, said, “I hope they can get into a good university; I hope they can have good grades in school, be useful, and contribute to society.”

Theme 4: No such thing as free lunch. In this theme, people described the relevant work-related factors affecting WIF. Because the job was viewed as a tool to improve family lives by most of the participants, a high level of work demands seemed to be more acceptable. However, it appeared that everything comes with a price, and work-related factors still harm participants’ family life. “Definitely” was often used by the participants when the researcher asked, “Does your job affect your family life?” For example, P13 said, “It (work) definitely impacted my family life to some degree; if you have a job, plus, you have family, then you definitely will be facing some problems.”

A sub-theme of no such thing as free lunch, money is the cure was endorsed by most of the participants. It appeared that income from work had a strong influence on the level of WFC. For example, P1, the main breadwinner of his family, stated, “Will it (WFC) get worse? It really depends on the money. To be honest, the biggest problem in my family right now is the money.” And P5 stated, “In my family, if I can really solve most of the financial problems, then I think 70,80 per cent [of WFC] will be fixed.”

As a sub-theme of no such thing as free lunch, the occupational difference was endorsed by most of the participants. It appeared that people in different occupations would experience different WFC and influence the level of WIF. For example, P7, who is a university English lecturer, said,

My job is relatively simple, [I] don’t have to go to university every day; you only be there when you have lectures, and you can leave after finishing the lecture; you don’t even need to be in contact with other colleagues […] when you don’t have to be in contact with others, you have fewer conflicts [at work].

It appeared that the working hours had affected the experience and the level of WIF. Some participants claimed that long working hours at work increased the incompatibility between work demands and family needs. For example, P3, who works from 9 AM to 9 PM, six working days per week, said,

My grandfather is sick and has to stay in the hospital right now. My mom is having a rough day; she really wants someone to take turns to take care of [my] grandfather with her, but [I] don’t have the time to do so.

P10, who owns a restaurant and has to work from 8 AM to 9 PM six days per week and also have to spend a half-day on Sunday at work, stated, “so it is tough for me to fulfil my family responsibilities; it is just impossible to do both, there is only so much time […], so it is impossible for me to handle the things at my family.”

In addition, the influence of flexible working hours on WIF was endorsed by some of the participants. Some participants claimed that flexible working hours have decreased the incompatibility between work demands and family needs. P13 said, “Because the work time of my job is quite flexible, it gives me more free time with my family.” Contrarily, some participants claimed that the inflexible working hours at work have increased their WIF. For example, P12, who is a nurse and follows a shift work schedule, stated,

I mean, sometimes, my children’s school would arrange things like parent-children activities, parent-teacher conferences, or sports meets, and I, as the parent, am required to attend. But because of my work shift, it is hard for me to change my shift and go to these events that I am supposed to attend.

Moreover, it appeared that a supportive work environment could help to ease the negative experience at work, hence decreasing WIF. For example, P13, who entered the workplace one year ago, said,

The heads of my department really care about you, helped me a lot, […] just like a master’s supervisor or PhD’s supervisor, they are like the supervisors, guide you and teach you step by step […] because of these bits of help, it made my work easier.

On the contrary, an unsupportive environment would make the participant feel more work distress, ultimately leading to or increasing the level of WIF. For example, P4, who was recently promoted at work, reported as follows:

My team leader said he would take care of me; I mean he promised to guide me, but he had his own work too. So, most of the time, he just gave tasks to me; I had to figure them out by myself; I was always scared that I would mess it up because lots of the tasks were new to me, […] so I felt anxious all the time.

Theme 5: Emotional turmoil and strain. This theme focuses on the psychological/emotional aspects that are related to WFC. A sense of work distress was evident in all the participants. It appeared that work distress had led to the experience of WIF. Some participants described this work distress as the “emotion at work”. For example, P6 said, “I keep telling myself don’t bring back the emotion at work to my family. I mean, like the bad emotion at work, but I am just a human, so I couldn’t just let it stop.” On the other hand, work distress is also described as a “physical exhaustion”. Sentences like “I am so tired at work.” “My work makes me so tired,” And “I don’t want to do anything when I go back home from work.” were often said by the participants.

As a sub-theme of the emotional turmoil and strain, the display of anger was endorsed by some of the participants. It appeared that some participants, especially the young, unmarried participants, would tend to lose their temper at home easily and vent on their elderly parents, if they were overloaded at work or had ill feelings at work. “I get angry for no reason [at home]” or “I will get mad easily [at home]” were mentioned by some participants. In addition, it appeared that the female participants who are married and have children tended to vent to their children when they were overloaded in both work and family domains. For example, in P12’s statement, she said,

Sometimes I had a long day and was very tired. Then, when I got back home, I had to help with my children’s homework, […] sometimes I cursed, not cursed, I mean I yelled [at my children], [I would say:] ‘how could you still not understand? I have taught you so many times!’ with a tone of blame. […] I became angry easily when they didn’t know how to do their homework.

And P7, who has a 12-year-old son named N, said, “I became angry, I was mad, mad at N because I would think that he’s all grown up; why couldn’t he manage himself? I mean, why couldn’t he manage his time by himself?”

Additionally, the feeling of being an incompetent family member and the inappropriate behaviours toward family members have caused some participants to have guilty feelings. It appeared that some participants would feel guilty when they could not fulfil their family responsibilities due to work demands. For example, P10, who is living with her big sister, daughter, and mother and works over 66 hours per week, stated,

My child is still young; I wish that I could have more time to be with her; everyone would want to spend more time with their kid; but I just couldn’t do that [because of the work], […] [although] I asked my big sister to help me [to take care of my child], but you have to understand, this responsibility, I couldn’t just throw it all to my sister, right? After all, she is my baby girl!

And P15, whose parents are left-behind elderly, stated,

I feel guilty. I didn’t fulfil the obligation of being their child. All I did was give them money [when I went back to see them], and it was not even a lot of money, so I feel a little bit guilty.

Some participants felt guilty after venting on their family members due to the experience of WFC. For example, P11 mentioned that he feels guilty after he vents on his family members because of the stress at work; he said, “I actually feel very guilty [after I vent on my family members], but I couldn’t control it.” And a sense of guilt was also evident in P12’s statement; when the researcher asked her, “How do you feel about venting on your children because you are tired at work?” she responded,

I thought about it afterwards, and then I realised I shouldn’t act like that, […] it’s my fault, I should be gentler, no matter how tired I am, I should adjust my emotions before I help with their (the children) homework.

Theme 6: Struggle to balance. This theme focuses on the outcomes of WFC. Most of the participants in this study claimed that WFC had negative impacts on both their work domain and family lives. WFC is like a vicious cycle affecting participants’ work and family domains. This was evident in P4’s interview; she reported as follows:

There was a period of time when I had lots of tasks [at work]. I slept very late, I became moody, […] it is like a vicious cycle, I was in a bad mood because of the stress at work, then because of my mood, I didn’t want to eat or do other things [at home], then because of that, I was in bad health, then I was sick.

A similar explanation was provided by P12; she stated,

I [usually] get back home [from work] around 8 PM, […] I only have half an hour for my dinner, and I feel like my time is very tight every day. [After my dinner], then I have to spend some time with my kids and help with their homework. Usually, children should go to bed before 10 PM, but my kids won’t go to bed until 11 PM, […], so I couldn’t go to bed until at least midnight, […] if you don’t have enough sleep, you don’t have enough energy [at work].

Some participants claimed that they had to deny opportunities at work to fulfil their family needs. For example, P2, who is a small business owner and lives with his girlfriend and parents, said,

My girlfriend doesn’t want to live at my home with my parents when I am not there. So, let’s say I have a business trip; then I must go back home on the same day […] [can’t go on a business trip that takes more than one day] is not just a little bit depressing; it’s more like frustration and what a shame [I lost a potential business opportunity because I can’t go on the business trip].

In addition, P8, who is a single mom with two children, claimed that the conflict between family needs and work domain has caused her to lose the development opportunity at work; she said,

After you left your work [because of family needs] for a while, your company would not treat you the same [when you come back]. I mean, during the period of your leave, lots of opportunities they given to other people.

Last, most of the participants in this study claimed that the WFC has made them become lazy. It appeared that the overwhelming workload or the emotion at work/family affected the emotions and behaviours of the participant in another domain. For example, “Don’t want to do housework” was often mentioned by the married male participants. P1 said, “When I came back home [after work], I was so tired, I didn’t want to do anything.” In addition, P10, who is the main breadwinner of her family, said, “I will be affected by their (family members’) emotions; […] I would feel very depressed all day [if my family members told me they are in a bad mood], and it would affect my work performance.”

4. Discussion

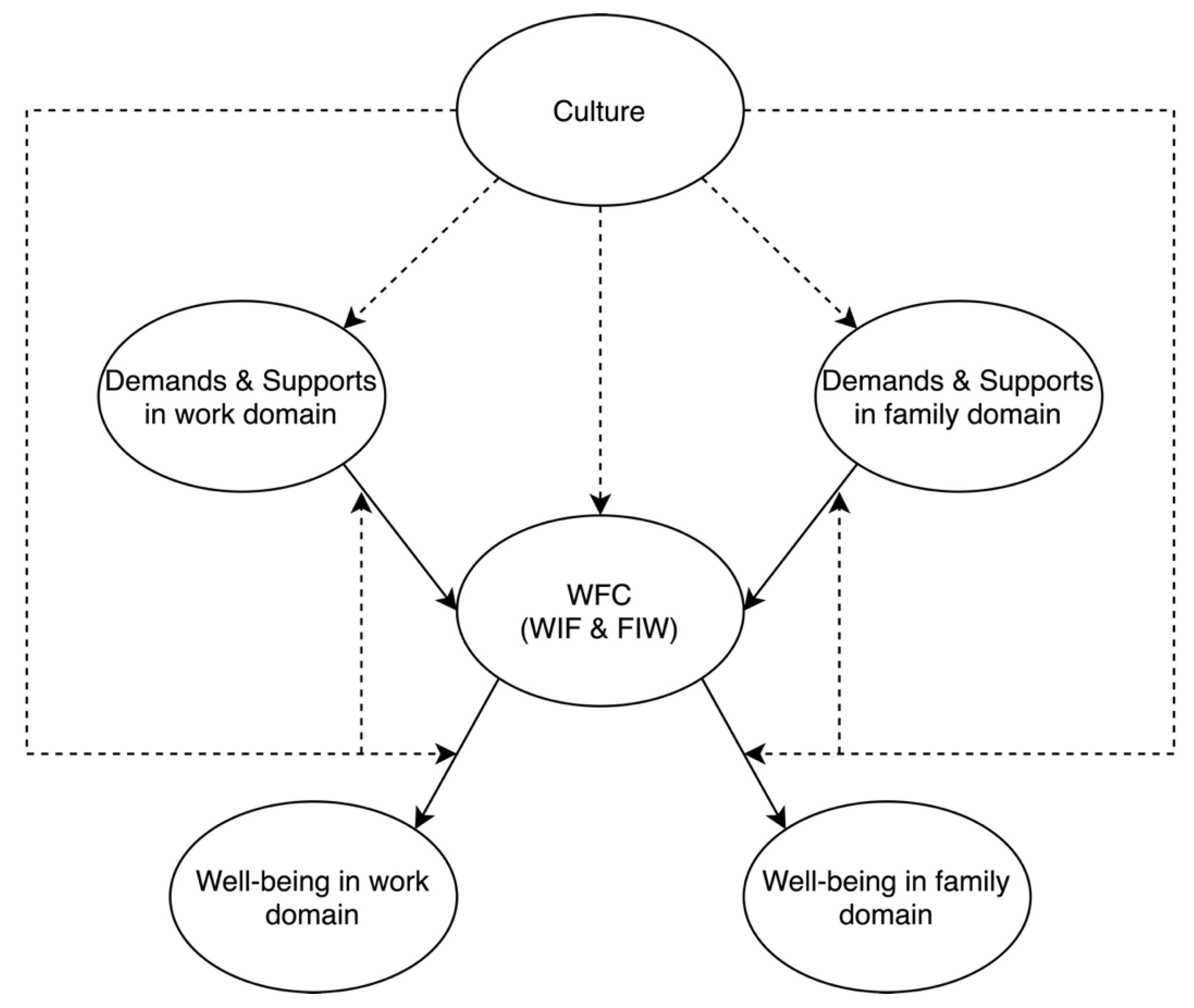

The present study explored the WFC phenomenon in China from the standpoint of Aycan’s (2008) cross-cultural perspective. The findings were consistent with Aycan’s (2008) cultural perspective; WFC is a relatively subjective phenomenon, and that culture would influence work and family-related support and demand, thereby affecting the experience of WFC (e.g., Lu & Cooper, 2015; Korabik et al., 2008; Shaffer et al., 2011). Some of the findings are similar to the previous Western findings (e.g., Choo et al., 2016; Innstrand et al., 2010; Roth & David, 2009; Cerrato & Cifre, 2018; Bakker et al., 2008; Korabik, 2015). I.e., the influence of occupational differences (i.e., long working hours and flexible working hours, supportive work environment) and gender roles on WFC, the psychological and emotional response to WFC (i.e., distress, anger, and guilt), and the decrease in work/family performance due to WFC.

The participants in this study described WFC as just a life experience or just a minor problem in life. This standpoint toward WFC has led most of the participants to underrate the negative impact of both types of WFC. However, this attitude towards WFC did not simply mean that WFC has no negative impact. The negative impacts of WFC on the work domain (e.g., decreased work performance), family lives (e.g., becoming lazy) and an individual’s well-being (e.g., guilt) were reported by most of the participants.

Instead, such an attitude has limited participants’ coping strategies with WFC, resulting in most participants choosing to use an avoidance coping strategy to cope with WFC (e.g., P1 said, “[…] give it a couple of days, and everything will be fine again”). Subsequently, the negative effect of WFC did not weaken. Adopting an avoidance coping strategy might be due to the influence of Taoism, which emphasises that the concept of good and bad is subjective; hence, there is no requirement to take extreme measures in order to eradicate what is considered bad, since nature will restore the balance without the need for action (Cheng et al., 2010).

Based on the descriptions of the interviewees, several Chinese cultural values seemed to influence the experience of WFC in China. The family collectivism orientation in China, such as strongly valuing the family and the duty of providing care for the family members (Lu & Cooper, 2015), created a strong sense of family that influences the work value of the interviewees, resulting in interviewees believing that work is one way to improve family wealth, instead of personal achievement. In addition, such a strong sense of family also influenced the participants’ decision-making. Most interviewees would rather give up their jobs when experiencing work-family dilemmas. These findings are similar to those found in Gui and Koropeckyj-Cox’s (2016) study, which argued that Chinese family values are somewhat in conflict with the development of society. Despite the development of society, such as globalisation, which has created more opportunities for employees, family collectivism orientation creates a strong sense of family obligation, forcing employees to pay more attention to the family domain and hindering them from pursuing greater personal achievement.

The family collectivist orientation also seemed to be mixed with other Chinese traditional values and contributed to the close and supportive relationship between parent and child and between husband and wife.

The supportive relationship between parent and child was mutual. On the positive side, a help-seeking coping strategy was spotted being used by most of the interviewees, especially those with children. Interviewees claimed that their elderly parents would take care of their daily lives and pay for the daily expenses. In addition, those who have children often ask their elderly parents to take care of their children when they are at work. Such support from elderly parents not only decreased the participants’ time needed for family responsibilities but also reduced their cost of living and eased the worries about family life, consequently decreasing family distress and therefore, minimising the risk of experiencing WFC (e.g., Lu et al., 2006; Byron, 2005; Direnzo et al., 2011).

On the negative side, the value of filial piety has created a sense of must to support and care for their elderly parents, which stressed the interviewees out. The participants often mentioned two factors regarding the stressful feeling of fulfilling filial piety: the time needed to provide care for their elderly parents and the worry about money. The time required to provide care for elderly parents might result in an unbalanced time allocation between family and work, thereby leading to FIW (e.g., Lu et al., 2006; Korabik et al., 2008). The worry about money can be seen as a lack of financial security. In other words, filial piety has caused the participants to worry about their financial ability to handle unexpected costs (e.g., subjective financial insecurity, such as worrying about medical expenses for elderly parents). Under the feeling of financial insecurity, people tend to feel like they have to focus on the work domain in order to increase their income, increasing the risk of experiencing WIF (Odle-Dusseau et al., 2018).

We noticed that the relationship with elderly parents seemed to influence the work/family factors that related to WFC, resulting in a difference between the findings of this study and previous Western findings. This seemed to give rise to unique situations affecting WFC. First, elderly parents’ support seemed to moderate the relationship between the number of children and WFC among the interviewees. Previous Western findings suggested that younger children would require more time to care, thereby increasing the time needed for child-rearing, which leads to an increase in WFC (Huffman et al., 2013). In this study, it seemed that because elderly parents would provide care for their grandchild, parent participants generally reported that they feel more WFC as their children grow up due to the cost of education and the time needed for help with children’s homework, and the feeling of distress when the children’s school grade did not meet parental expectations.

Second, many Western studies on the relationship between income and WFC focused on how income affects the available strategies to cope with FIW. For example, people who have high incomes can hire a nanny to take care of their children, decreasing the time needed for family responsibilities, and thereby reducing time-related FIW (Ciabattari, 2007). In contrast, instead of associating income with coping strategies, most interviewees associated income level with the future, such as worrying about the future of the family, and being afraid that if they cannot increase their income level, the experience of WFC would be exacerbated. In other words, income seemed associated with the strain-based WFC among the participants. This seems to be because elderly parents would provide daily and financial support to the interviewees. But at the same time, the thought of filial piety has created a feeling of financial insecurity. Such insecurity increases family strain, thereby leading to strain-based WFC (e.g., Lawrence et al., 2013; McGinnity & Russell, 2013).

Third, it seemed that the belief in filial piety exacerbated the experience of WFC among the interviewees with no siblings (i.e., the only child of the family). Most participants claimed that because they are the only child of the family, they feel more pressure regarding their ability to take care of elderly parents in the future. Due to the Westernised concept of “family” focusing on the parents and adult children, there is a dearth of Western studies investigating how being an only child would affect the experience of WFC. Only one Chinese study (Su & Xing, 2014) that we are aware of discussed the experience of being an only child, explaining that it increases the risk of having family overload. For example, an only child might need to spend more time and energy on caregiving responsibilities (e.g., eldercare) due to the lack of sibling support, thereby increasing WFC.

Moreover, traditional Chinese thoughts have influenced the relationship between husband and wife; gender inequality in household chores and childcare responsibility is still distinct in current Chinese society. This traditional gender role has affected the level of WFC differently for male and female participants. Based on interviewees’ descriptions, male participants generally reported a lower level of WFC, whereas female participants reported experiencing a greater WFC due to their higher level of family responsibilities. This finding of a gender difference in the experience of WFC is in line with findings from previous studies, which also identified greater WFC for females (e.g., Rehman & Roomi, 2012; El-Kassem, 2019).

Additionally, this gender inequality in family responsibilities seemed to mix with the strong sense of family, creating a one-sided supportive relationship between husband and wife (i.e., the wife has more family responsibilities and is more willing to take them on). This has the potential to enhance conflict with workplace culture (e.g., employees have to devote themselves to work fully), resulting in gender discrimination in the workplace, such as females having fewer hiring and promotion opportunities (Zhang et al., 2021). This might explain why P8, a single mother, would report that she felt that she had lost development opportunities due to family matters.

Furthermore, other traditional Chinese thoughts, such as honouring the family and making the family proud through personal achievement (Xu et al., 2005), seem to contribute to the strong parental expectations in China. Such an expectation was often associated with the children’s educational performance (e.g., good grades at school) and reflected increased demands on parents’ time. The parent participants reported that they had to spend extra hours (e.g., help with children’s homework) or money (e.g., after-school classes) to improve their children’s educational achievement. This finding helped to understand why interviewees would feel more WFC as their children grow up. The age of children appeared to be one of the factors contributing to the disparity in the relationship between WFC reported among the 16 interviewees in this study and the findings from previous Western research. Yet, more studies are needed to explore this little-studied issue.

4.1. Limitations and Future Study

This study has three limitations. First, the qualitative data of the present study were collected via online interview instead of a face-to-face interview, which can provide more information from the body language of the interviewee (Opdenakker, 2006). However, due to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the lockdown, a face-to-face interview was not an option, and an online interview was much safer for both the interviewer and interviewees. Second, the oldest participant (P15, 53 years old) in this study claimed that his age had changed his view on work (e.g., achievements, goals, etc.), and he now would not think about work when he is at home. And thereby, he is experiencing less WFC; in other words, age as a demographic variable might influence the level of WFC. However, due to the nature of phenomenology research (Creswell, 2013), some of the demographic variables (e.g., age) that might affect the experience of WFC were not considered in this study if they could not be clustered into a theme. Third, due to the nature of the qualitative study, the relationship between the WFC and its antecedent/consequence cannot be verified (Casares & White, 2018). However, the findings provided insight into how the Chinese culture has affected the experience of the WFC phenomenon among the sixteen participants. A quantitative study is encouraged to further verify the accuracy of the findings of the present study.

4.2. Contribution to WFC Literature

The findings of this study have several contributions to the existing WFC literature. First, this study provides deep insight into how Chinese employees experience WFC and has broadened the understanding of the WFC phenomenon in the Chinese cultural setting. And to the researcher’s knowledge, the present study is one of the first to use a phenomenological approach to researching WFC in China.

Second, most previous WFC studies were conducted in Western countries; this study explored the WFC phenomenon in China and described how people with a traditional Chinese cultural background experienced WFC. Although most of the findings are in line with previous Western studies, some differences between the Western countries and China in the experience of WFC were found; in addition, the findings suggested the relevant factors (e.g., the sense of guilt, being the only child, parental expectation, filial piety) that related to WFC in China, which provide a direction for the future WFC studies in China and in other Confucian heritage countries in Asia.

Lastly, the differences between the findings of the present study and the previous Western WFC findings have highlighted the necessity of further investigating WFC in different cultural settings and that selecting Western-developed WFC theories or findings should be cautious, since they might not be suitable for different cultural backgrounds.

4.3. Implications of the Present Study

The findings of this study indicated that due to the increased prevalence of the experience of the WFC phenomenon in China, participants started to normalise the WFC phenomenon and ignore its negative consequences. Although participants generally received a certain degree of support from their elderly parents because of the influence of traditional Chinese culture, which has helped to ease the WFC. However, such support seemed to be only at a material and physical level. Wallace (2005) pointed out that emotional support can improve individuals’ well-being and might decrease the WFC’s negative psychological impact. Thus, in addition to seeking material or physical support from family members, individuals should also seek emotional support from family members and/or supervisor/co-worker through communication; on the other hand, family members and colleagues could show emotional support through listening to and empathising with the individual when they are experiencing distress events, such as WFC (e.g., Greene & Burleson, 2008; Mathieu et al., 2019).