1. Introduction

Human milk is an irreplaceable source of nutrition, is essential for the infant’s growth and development right after birth and for early life stages survival [

1,

2]. Its composition improves the immunological, neurological, and gastrointestinal development and maturation. Human milk composition is dynamic and influenced by several factors, including genetics, gestational and infant's age, circadian rhythm, geographical location, maternal nutrition, and lactation stage [

3].

Regarding the lactation stage, colostrum is the first fluid secreted during the first days postpartum (1–7 days), is rich in bioactive factors, such as immunoglobulins, lactoferrin, antibodies, growth factors, and immune cells, and exhibits a higher protein content [

4]. Transitional milk, produced between 7 and 14 days, represents an intermediate stage in which immune-modulating components decrease while energy-yielding nutrients gradually increase, and production ramps up to meet the nutritional needs of the infant [

1,

5]. Mature milk is secreted from the third week onwards, characterized by a more stable composition, and it provides a balance of nutrients, including fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals, to support the infant's growth and development [

1,

4].

Previous research has shown that compositional shifts are not limited to macronutrients and bioactive factors but extend to small molecules that comprise the metabolomic profile of human milk. The current studies focus on mature milk compared to colostrum [

6], or transition milk with mature milk [

7]. Additionally, another study compares the metabolite profile differences in milk stages between women with diabetes mellitus and those from healthy women [

8].

However, the existing evidence is necessary to identify the human milk metabolite profile at different stages in the Mexican population, because geographical location is a key factor that shapes human milk metabolome. This study aims to characterize and compare the metabolite profiles of colostrum, transitional, and mature milk using an untargeted GC-MS approach. Additionally, it explores potential correlations between the identified metabolites and maternal nutritional factors. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of human milk composition throughout lactation, supporting optimal infant nutrition.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This was a longitudinal, prospective, and observational study to assess whether the metabolite profiles differ between colostrum transition milk and mature milk. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Commission for Scientific Research of Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in Mexico City (Approval # R-2021-785-096). All participants provided written informed consent after the procedures were explained to them.

2.2. Study Population

The study included human milk samples from 113 Mexican women who practiced exclusive breastfeeding. Eligible participants were women aged 18 to 35 years who were primiparous, had delivered a single full-term infant (≥37 weeks of gestation), and practiced exclusive breastfeeding during the first month postpartum. Additional inclusion criteria required no history of smoking, alcohol consumption, or substance abuse during pregnancy or lactation. All participants provided written informed consent before to enrollment.

2.3. Sample Collection and Data Acquisition

Three home visits were scheduled on postpartum days 5–7, 8–15, and 16–28 to collect human milk samples representing distinct lactation stages: colostrum, transition milk, and mature milk, respectively. Not all participants provided samples at all time points. Some missed the first or second visit, while others could not be contacted for the third visit.

Milk expression was performed in the morning (between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m.) for 20–25 minutes to ensure complete breast emptying. A Medela® electric breast pump (Lactina Select model, Switzerland) was used, with glass collection cups, tubing, and bottles previously sterilized with ethylene oxide.

To facilitate milk ejection, gentle breast massage was applied during expression, which was conducted simultaneously on both breasts. The expressed milk was homogenized, and an 8 mL aliquot was transferred into a sterile 15 mL conical tube. The remaining milk was returned to the mother for infant feeding. Samples were transported on ice in a Thermoflask® container (Massachusetts, USA) and stored at −80 °C until further processing.

During each visit, a trained nutritionist administered a standardized questionnaire to collect demographic and anthropometric data, including maternal age, height, pre-pregnancy body weight, and infant sex. At the third visit, maternal body weight and total fat mass were measured using a bioimpedance scale (BC-585F, TANITA®, IL, USA).

2.4. Profile of Human Milk Metabolites

To identify the human milk metabolites profile, an untargeted GC-MS (gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) technique was performed as described by Páez-Franco et al., (2021) [

9]. Human milk samples were thawed and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. The fat was removed with a disposable bacteriological loop, and the serum was collected in sterile 1.5 mL tubes. Thirty microliters (30 µL) of human milk serum were derivatized using a methoximation followed by silylation method for subsequent metabolomic analysis in a GC/MS system (Agilent 5977A/7890B, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an automatic autosampler (G4513A, Agilent) and run under the following conditions: splitless column flow 1 mL/min, inlet temperature 200 °C, Electronic Ionization (EI) source temperature 200 °C, and interface temperature 250 °C. A column HP5ms (30 m × 250 µm × 0.25 µm, Agilent) with helium 99.9999% as a mobile phase was employed. The method consisted of a 1-minute hold at 60 °C with an increased ramp of 10 °C/min to 325 °C, with a final held time of 10 minutes.

The obtained chromatogram files were transformed to .mzdata files using the Agilent Chemstation software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The feature detection, spectral deconvolution, and peak alignment were realized using the Mzmine2 software v.54; the parameters used were retention time range, 5.5–27.5 min; m/z range, 50–500; m/z tolerance, 0.5; noise level, 1 × 103; and peak duration range, 0.01–0.2 min. Once the filtered data were obtained, the metabolite identification was carried out by comparing the spectral results with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) 2.0 spectral library; only results with a probability greater than 70% and a matching score above 700 were considered valid, while values falling below this threshold were labeled as unknown and excluded from the analysis.

2.5. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

Initially, a statistical analysis was conducted using a single milk sample per participant, randomly selected from the cohort of 113 women (colostrum, n = 42; transition milk, n = 36; mature milk, n = 34). This approach was used to avoid data pseudo-replication, as not all participants provided samples for all three lactation stages. Then, another analysis was performed on a subset of paired samples from 21 women who provided three milk samples (colostrum, n = 21; transition milk, n = 21; mature milk, n = 21).

Data processing and statistical evaluation were performed using MetaboAnalyst version 6.0 (except when stated otherwise). Missing values were imputed with one-fifth of the minimum positive value detected for each metabolite, based on the assumption that undetected values likely fell below the detection threshold. Repeatability for each metabolite was evaluated using quality control (QC) samples prepared by pooling equal aliquots from all analyzed samples. Metabolites with a relative standard deviation (RSD = SD/mean) greater than 30% in QC samples were excluded, resulting in a final set of 23 metabolites. Data normalization was conducted by sum normalization, followed by log10 transformation and autoscaling (mean-centering and division by the standard deviation).

Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was applied to enhance class discrimination between milk types. For the dataset with paired samples, a multilevel PLS-DA was performed, using subject ID to control for within-subject variation (from the mixOmics package in R). Model performance was assessed through 5-fold cross-validation. The parameters R2 (explained variance) and Q2 (predictive ability) were used to evaluate model quality. Additionally, a 100-permutation test was conducted to validate the robustness of the models. Metabolites contributing most to group discrimination were identified based on variable importance in projection (VIP) scores, with a threshold of VIP ≥ 1.0. For the second dataset with paired samples per participant, the Friedman test using subject as a blocking factor was used to assess differences between milk types. Metabolites with p < 0.1 were further evaluated using post-hoc pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Features

One hundred and thirteen human milk samples of women who breastfed exclusively were included in this study. The samples corresponded to colostrum (

n = 42), transition (

n = 36), and mature milk (

n = 35). The main anthropometric and demographic characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Identified Metabolites

Using an untargeted metabolomics approach, 23 different metabolites were found in human milk serum samples. The identified metabolites belonged to four main groups, amino acids and derivatives (Alanine, Aspartate, Creatinine, Glutamic acid, Glycine, Leucine, Proline, Serine, Threonine and Valine), sugars and derivatives (Glyceric acid, Glycerol, Glycerol phosphate, Inositol and Rhamnose), fatty acids and derivatives (11,14-Eicosadecanoic acid, Decanoic acid, Dodecanoic acid, Hexadecanoic acid, Oleic acid and Tetradecanoic acid), and energetic metabolites (Alpha-ketoglutarate and Lactic acid).

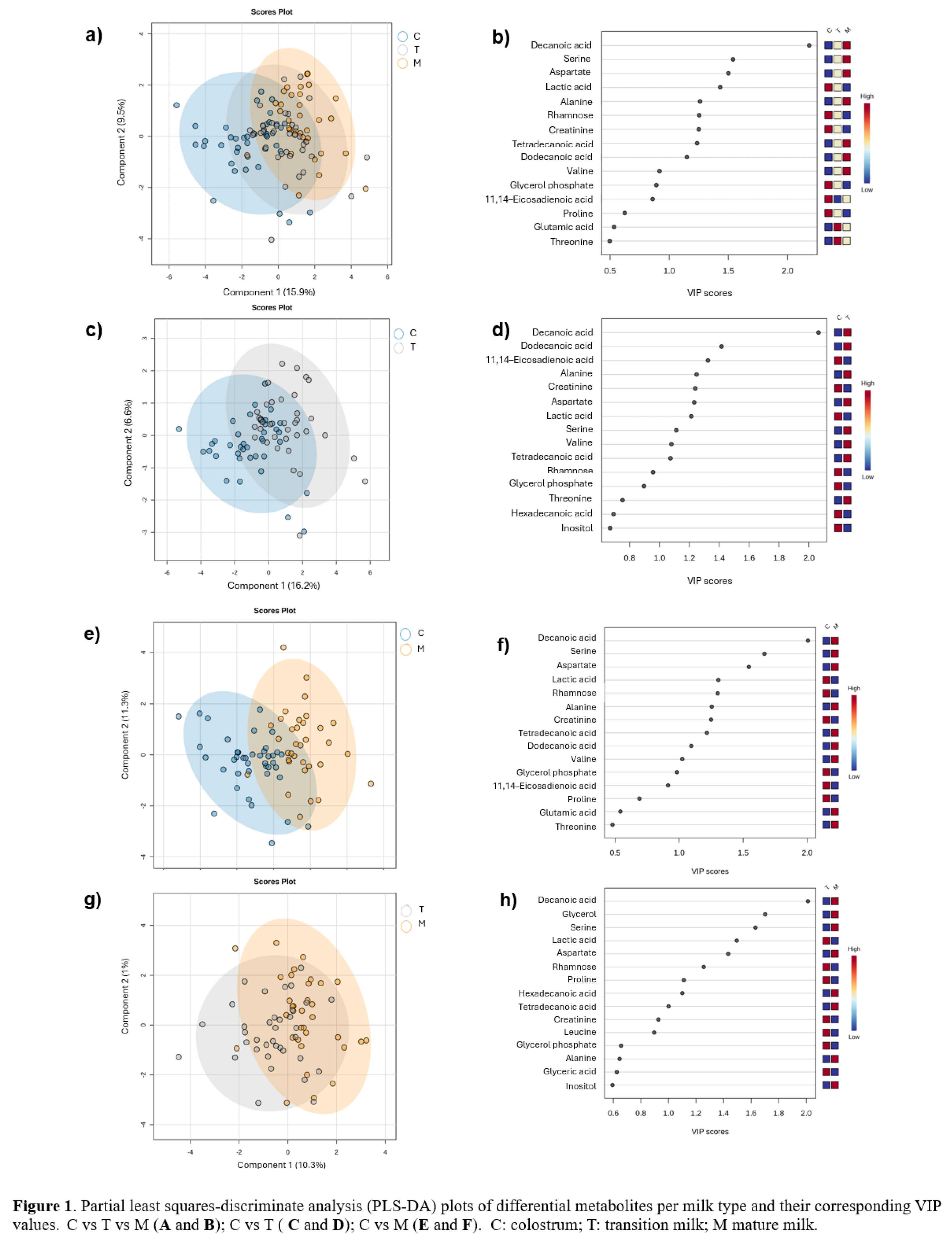

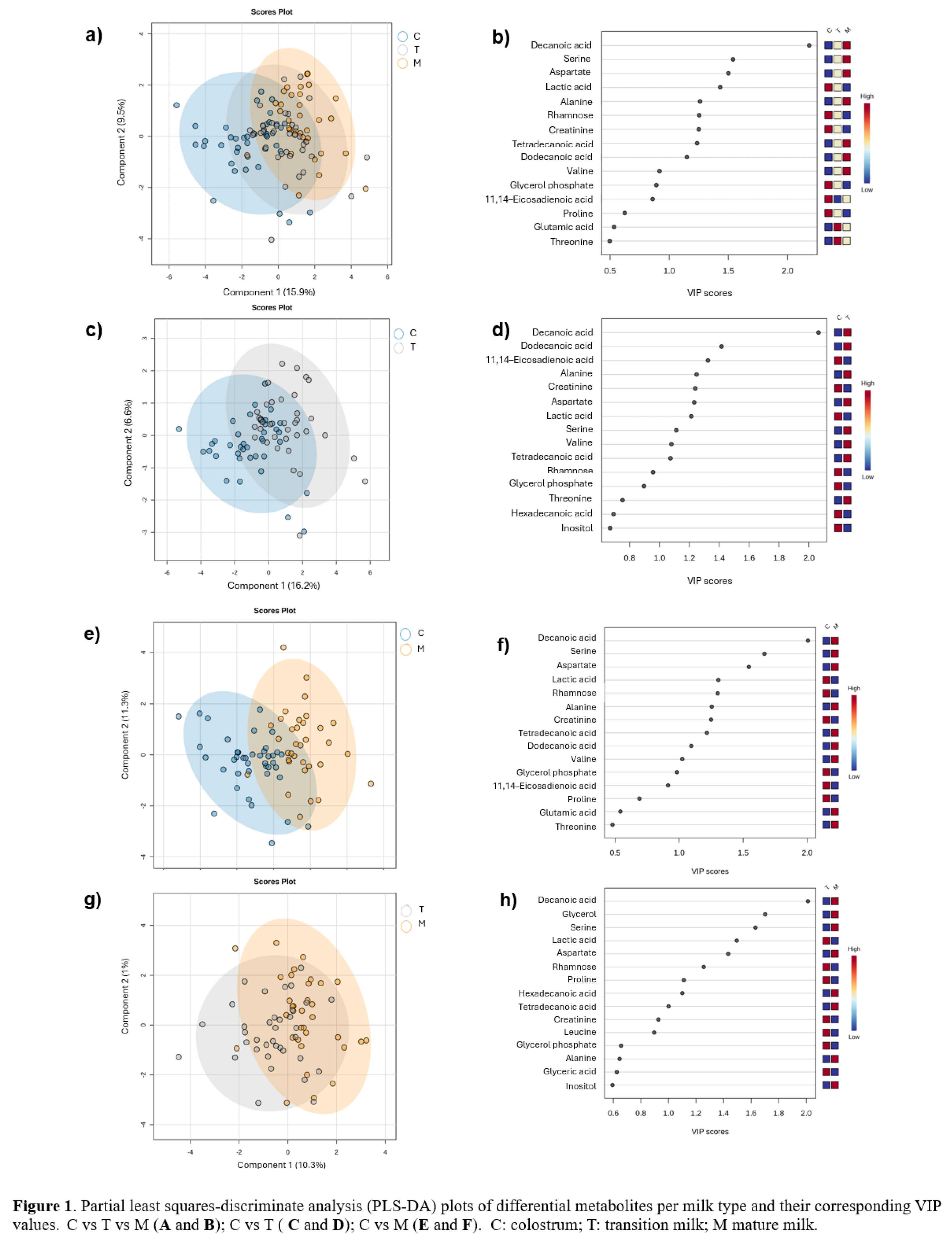

3.3. Differences in Metabolite Profiles per Milk Type

A supervised multivariate partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was performed to categorize the samples according to the milk type. The robustness of the model classification was assessed trough a cross validation and permutation analysis for the following comparisons: colostrum versus transition milk versus mature milk (C vs T vs M) (Figure 1a); colostrum versus transition milk (C vs T) (Figure 1c); colostrum versus mature milk (C vs M) (Figure 1e) and transition milk versus mature milk (T vs M) (Figure 1g), obtaining adequate prediction parameters, except for the T vs M group indicating a less variation in the metabolites profile in this types of milk, due to the predicted accuracy is less than 0 (

Table 2). The variable importance to the Projection (VIP) metabolites relevant to each milk type is depicted, respectively in Figure 1b, d, f, and h. It was observed that VIP values belonged to fatty acids, amino acids, sugars, and derivatives.

Then, a comparison analysis was conducted using only one distinct milk sample per woman. Within the class of amino acids and derivatives, alanine levels decreased throughout lactation; its proportion was significantly higher in colostrum compared to both transitional (p = 0.002) and mature milk (p < 0.001) (Figure 2a). Conversely, aspartate levels increased during lactation, with significantly higher proportions in transitional (p = 0.01) and mature milk (p < 0.001) compared to colostrum (Figure 2b). Creatinine levels decreased during lactation, with a higher proportion in colostrum relative to transitional (p = 0.01) and mature milk (p = 0.002) (Figure 2c). Also, proline levels decreased during lactation; the proportion was lower in mature milk compared to colostrum (p = 0.01) and transitional milk (p = 0.01) (Figure 2d). Serine levels increased during lactation, with significantly higher proportions in transitional (p = 0.05) and mature milk (p < 0.001) compared to colostrum (Figure 2e). Similarly, valine levels increased in mature milk (p = 0.002) compared to colostrum (Figure 2f).

Regarding sugars and derivatives, only rhamnose showed significant differences, with a higher proportion observed in colostrum compared to mature milk (p < 0.001) (Figure 2g).

In the class of fatty acids and derivatives, the proportion of decanoic acid increased during lactation, with significantly higher levels in transitional (p < 0.001) and mature milk (p < 0.001) compared to colostrum (Figure 2h). Similarly, dodecanoic acid levels increased over time, with higher proportions in transitional (p = 0.003) and mature milk (p = 0.001) than in colostrum (Figure 2i). Tetradecanoic acid showed significantly higher proportions in mature milk (p = 0.01) compared to colostrum (Figure 2j). In contrast, the proportion of 11,14-eicosadienoic acid was significantly higher in colostrum compared to mature milk (p = 0.01) (Figure 2k).

Finally, in the energetic metabolites class, only lactic acid decreased during lactation, showing significant differences in colostrum compared to transitional (p = 0.01) and mature milk (p < 0.001) (Figure 2l).

A second analysis was conducted on a subsample of women who provided milk samples at all three lactation stages (n = 21). Among the amino acids, aspartate (p = 0.003) and valine (p = 0.004) showed significant increases over time, with higher proportions observed in mature milk compared to colostrum (Figure 2A and B). Additionally, two amino acids exhibited borderline differences. Alanine showed a decreasing trend, with significantly higher proportions in colostrum compared to both transitional (p = 0.01) and mature milk (p = 0.004) (Figure 2C). Similarly, serine levels decreased during lactation, with higher proportions in colostrum relative to transitional (p = 0.04) and mature milk (p = 0.002) (Figure 2D).

In the fatty acids and derivatives group, a significant difference was observed only for 11,14-eicosadecadienoic acid, which decreased throughout lactation. Its proportion was significantly higher in colostrum compared to mature milk (p = 0.024) (Figure 2E).

In the second analysis, no significant differences were observed in the sugars and derivatives or energetic metabolites classes.

3.4. Correlations with Maternal Characteristics

Finally, it was evaluated whether correlations exist between the identified metabolites and the maternal anthropometric characteristics. The analysis revealed moderate negative significant correlations between amino acids such as aspartate, glycine, glutamic acid, leucine, and serine with maternal anthropometric characteristics, including pregestational body weight, and weight, BMI, and body fat on days 7, 15, and 30 postpartum (r2 = -0.18 to -0.28; p = < 0.05). In contrast, lactic acid showed positive significant correlations with all these maternal anthropometric parameters (r2 = 0.17 to 0.27; p = < 0.05) (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive characterization of the dynamic metabolite profile in human milk across distinct lactation stages, colostrum, transitional, and mature milk, using an untargeted metabolomics approach. The identified metabolites covered metabolic categories such as amino acids, sugars, fatty acids, and energetic intermediates. The multivariate analysis revealed distinct metabolic signatures associated with milk type, particularly between colostrum and mature milk, suggesting substantial biochemical modulation during lactation. These changes were predominantly driven by amino acids and fatty acids, which showed the most pronounced variation. Furthermore, several metabolites exhibited significant correlations with maternal anthropometric characteristics, indicating the potential link between maternal physiology and milk composition. Together, these findings highlight the metabolic complexity of human milk and provide insights into how its composition evolves to meet the changing nutritional and developmental needs of the infant.

The dynamic modulation observed in amino acid concentrations throughout lactation aligns with previous reports indicating higher levels of several amino acids in colostrum compared to mature milk [

7,

10,

11,

12]. In our study, creatinine, and proline showed a marked decline over time. Proline results are consistent with a previous study where concentration was higher in colostrum compared to transition or mature milk (

p < 0.05) [

12]. On the other hand, we observed an increase in alanine, aspartate, serine, and valine levels during lactation, suggesting a potential shift toward enhanced metabolic support and tissue synthesis in later stages of infant development [

12,

13]. It was previously reported that alanine concentration increases through lactation, showing a higher concentration at 3–5 weeks of lactation compared to the 1–2 weeks (

p < 0.05) [

7]. The early predominance of the amino acids we found may reflect their involvement in the initial establishment of the newborn’s nitrogen balance, immune modulation and such be linked to their role metabolism and protein synthesis, both critical during neonatal growth and gut development [

7,

12]. Also, this amino acids in human milk are crucial for infant growth, in previous studies were found negative correlation between proline and infant weight at 1 moth postpartum [

13], serine was positively correlated with weight gain at 6 weeks postpartum [

14], while valine was found in lower concentration in colostrum of women who delivered infants with intrauterine growth restriction or large for gestational age, compared to appropriate for gestational age infants [

15].

Concerning fatty acids, decanoic, dodecanoic, and tetradecanoic acids significantly increased from colostrum to mature milk, a pattern consistent with the increasing lipid requirements of the growing infant [

16,

17]. This was previously reported, dodecanoic and tetradecanoic acid increase significantly during lactation (R

2 = 10.0%,

p < 0.03) [

18]. In contrast, 11,14-eicosadienoic acid was more abundant in colostrum, these findings align with those reported in a previous study, where the concentration was higher in colostrum (p < 0.05) compared to transition and mature milk which may be associated with its putative anti-inflammatory or signaling roles during early postnatal adaptation [

18].

The decrease in lactic acid observed across lactation stages could also indicate reduced anaerobic metabolism or changes in microbial activity within the mammary gland or milk itself [

19]. These patterns underscore the regulated biochemical environment of human milk and its functional alignment with infant developmental trajectories. In a previous work, no differences in lactate concentrations were found in 1–2 weeks compared to 3–5 weeks of human milk [

7].

The observed moderate correlations between several amino acids and maternal anthropometric variables suggest that maternal nutritional and physiological status may influence the biosynthesis or transport of specific milk components. This is consistent with previous reports indicating that maternal body composition affects the metabolite profile in human milk [

13,

20,

21,

22].

Interestingly, lactic acid levels correlated negatively with the same maternal variables, suggesting a possible inverse association with maternal metabolic rate or inflammatory status. These findings highlight the importance of considering maternal phenotype when studying milk composition and suggest potential targets for nutritional interventions in lactating women.

A key strength of this study is the application of untargeted metabolomics on a relatively large and well-characterized cohort, allowing for a detailed temporal resolution of metabolite changes. Additionally, the inclusion of a subsample with longitudinal sampling across all three lactation stages adds robustness to the interpretation of trends. Also, a rigorous sample collection protocol was applied in each stage. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged; some external factors such as maternal diet, and genetic variability were not controlled and could influence the milk metabolome. Another limitation is the relatively small sample size in the longitudinal subset, which may reduce statistical power for detecting subtle changes. Future studies should integrate maternal dietary intake and metabolic biomarkers to disentangle the complex maternal-infant metabolic interface. Moreover, combining metabolomics with other omics approaches may provide a more holistic understanding of milk functionality and its role in shaping infant development.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a detailed characterization of the human milk metabolome across three distinct stages of lactation using an untargeted approach. Significant variations were observed in amino acids, fatty acids, and sugar derivatives over time. The composition of human milk evolved notably from colostrum to mature milk, reflecting the changing physiological and nutritional development of the infant. Additionally, correlations between specific metabolites and maternal anthropometric characteristics suggest that maternal physiology plays a role in shaping milk composition. These findings enhance our understanding of the dynamic nature of human milk and may inform strategies to optimize maternal nutrition and infant feeding practices. As a future perspective, we aim to investigate the impact of maternal diet on the human milk metabolome, as well as the influence of specific metabolites on infant growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.Z.-M., M.R.-C. and L.B.-C.; Data curation, I.C.Z.-M., M.C.C.-I. and L.B.-C.; Formal analysis, I.C.Z.-M., M.R.-C., M.C.C.-I. and H.S.-V.; Funding acquisition, L.B.-C.; Investigation, I.C.Z.-M., M.R.-C., M.C.C.-I., H.S.-V., J.C.P.-F., M.M.-M. and L.B.-C.; Methodology, I.C.Z.-M., C.E.L.-G., M.M.-M., J.M.D.-S., J.V.-M. and L.B.-C.; Project administration, L.B.-C.; Resources, M.R.-C. and L.B.-C.; Software, I.C.Z.-M., M.C.C.-I. and C.E.L.-G.; Validation, C.E.L.-G. and M.M.-M.; Writing – original draft, I.C.Z.-M., M.R.-C. and L.B.-C.; Writing – review & editing, I.C.Z.-M., M.R.-C., M.C.C.-I., H.S.-V., J.C.P.-F., C.E.L.-G., M.M.-M., J.M.D.-S., J.V.-M. and L.B.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded with a grant from Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, No. 09 B5 61 61 2800/2023/00468. The funding body did not participate in the design of the study or in the interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social Pediatric Hospital (R-2021-785-096), IMSS, in Mexico City, Mexico.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to, privacy, legal or ethical reasons. The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), México, for the grant for PhD studies awarded to Imelda Cecilia Zarzoza-Mendoza (774438), and Cristian Emmanuel Luna-Guzmán (1134898); and for master’ studies for Maricela Morales Marzana (1287893).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- Bardanzellu F, Peroni DG, Fanos V. Human breast milk: bioactive components, from stem cells to health outcomes. Curr Nut Rep. 2020;9(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Yi DY. Components of human breast milk: from macronutrient to microbiome and microRNA. Clin Exp Ped. 2020;63(8):301–9. [CrossRef]

- Ojo-Okunola A, Cacciatore S, Nicol MP, du Toit E. The determinants of the human milk metabolome and its role in infant health. Metab. 2020;10(2):77. [CrossRef]

- Czosnykowska-Łukacka M, Królak-Olejnik B, Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M. Breast milk macronutrient components in prolonged lactation. Nutr. 2018;10(12):1893. [CrossRef]

- Neville MC. Lactation in the human. Anim Front. 2023;13(3):71–7. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Chen J, Shen X, Abdlla R, Liu L, Yue X, et al. Metabolomics-based comparative study of breast colostrum and mature breast milk. Food Chem. 2022;384(1):132491. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen KO, Meng F, Lanfranchi E, Young JF, Stanton C, C. Anthony Ryan, et al. Dynamic changes in the human milk metabolome over 25 weeks of lactation. Front Nutr. 2022;9(14). [CrossRef]

- Wen L, Wu Y, Yang Y, Han T, Wang W, Fu H, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus changes the metabolomes of human colostrum, transition milk and mature milk. Med Sci Mon. 2019;25(16):6128–52. [CrossRef]

- Páez-Franco JC, Torres-Ruiz J, Sosa-Hernández VA, Cervantes-Díaz R, Romero-Ramírez S, Pérez-Fragoso A, et al. Metabolomics analysis reveals a modified amino acid metabolism that correlates with altered oxygen homeostasis in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1). 10.1038/s41598-021-85788-0.

- Purkiewicz A, Stasiewicz M, Nowakowski JJ, Pietrzak-Fiećko R. The influence of the lactation period and the type of milk on the content of amino acids and minerals in human milk and infant formulas. Foods. 2023;12(19):3674. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez C, Franco L, Regal P, Lamas A, Cepeda A, Fente C. Breast milk: a source of functional compounds with potential application in nutrition and therapy. Nutr. 2021;13(3):1026. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Adelman A, Rai D, Boettcher J, Lőnnerdal B. Amino acid profiles in term and preterm human milk through lactation: a systematic review. Nutr. 2013;5(12):4800–21. [CrossRef]

- Isganaitis E, Venditti S, Matthews TJ, Lerin C, Demerath EW, Fields DA. Maternal obesity and the human milk metabolome: associations with infant body composition and postnatal weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):111–20. [CrossRef]

- Sadelhoff van, Siziba LP, Buchenauer L, Mank M, Wiertsema SP, Hogenkamp A, et al. Free and total amino acids in human milk in relation to maternal and infant characteristics and infant health outcomes: the Ulm SPATZ health study. Nutr. 2021;13(6):2009–9. [CrossRef]

- Briana DD, Fotakis C, Kontogeorgou A, Gavrili S, Georgatzi S, Zoumpoulakis P, et al. Early human-milk metabolome in cases of intrauterine growth–restricted and macrosomic infants. JPN. 2020; 44(8):1510-1518. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei R, Wu Z, Hou Y, Bazer FW, Wu G. Amino acids and mammary gland development: nutritional implications for milk production and neonatal growth. J Ani Sci Bio. 2016;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed B, Freije A, Omran A, Mariangela Rondanelli, Marino M, Perna S. Human milk fatty acid composition and its effect on preterm infants’ growth velocity. Child. 2023;10(6):939–9. 10.3390/children10060939.

- George A, Gay M, Trengove R, Geddes D. Human milk lipidomics: current techniques and methodologies. Nutr. 2018;10(9):1169. [CrossRef]

- Lubetzky R, Zaidenberg-Israeli G, Mimouni FB, Dollberg S, Shimoni E, Ungar Y, et al. Human milk fatty acids profile changes during prolonged lactation: a cross-sectional study. IMAJ. 2012;14(1):7–10.

- Sánchez-Hernández S, Esteban-Muñoz A, Giménez-Martínez R, Aguilar-Cordero MJ, Miralles-Buraglia B, Olalla-Herrera M. A comparison of changes in the fatty acid profile of human milk of spanish lactating women during the first month of lactation using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. A comparison with infant formulas. Nutr. 2019;11(12):3055. [CrossRef]

- Lyons KE, Shea CO’, Grimaud G, Ryan CA, Dempsey E, Kelly AL, et al. The human milk microbiome aligns with lactation stage and not birth mode. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):5598. [CrossRef]

- Saben JL, Sims CR, Piccolo BD, Andres A. Maternal adiposity alters the human milk metabolome: associations between nonglucose monosaccharides and infant adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(5):1228–39. [CrossRef]

- Saben JL, Sims CR, Pack L, Lan R, Børsheim E, Andres A. Infant intakes of human milk branched chain amino acids are negatively associated with infant growth and influenced by maternal body mass index. Ped Ob. 2022;17(5):e12876.

- Zarzoza-Mendoza IC, Cervantes-Monroy E, Luna-Guzmán CE, Páez-Franco JC, Sánchez-Vidal H, Villa-Morales J, et al. Maternal obesity, age and infant sex influence the profiles of amino acids, energetic metabolites, sugars, and fatty acids in human milk. Eur J Nut. 2025;64(2):92. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Anthropometric and demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and demographic characteristics of the study population.

|

n = 113 |

| Age (y) |

29 (18, 37) |

| Height (cm) |

159.95 ± 5.82 |

| Body weight (kg) |

|

| Pre-pregnancy |

63 (40, 120) |

| Postpartum (D30) |

63.25 (40, 106) |

| Body weight gain during pregnancy |

10.03 ± 5.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

|

| Pre-pregnancy |

24.01 (18, 43) |

| Postpartum (D30) |

25.05 ± 4.02 |

| Total body fat mass (%) |

|

| Pospartum (D30) |

32.98 ± 6.86 |

Table 2.

Predictability values of partial least squares-discriminate analysis (PLS-DA).

Table 2.

Predictability values of partial least squares-discriminate analysis (PLS-DA).

| Measure |

C vs T vs M |

C vs T |

C vs M |

T vs M |

| R2 |

0.416 |

0.331 |

0.518 |

0.227 |

| Q2 |

0.318 |

0.201 |

0.422 |

-0.147 |

| Accuracy |

0.576 |

0.698 |

0.839 |

0.614 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).