Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. e-Learning Lesson Uptake

3.2. Demographics

| Variables | Responses, n (%) |

|

Arrived at lesson through (N = 621) McMaster Optimal Aging Portal e-newsletter links from friends healthcare professional recommendation other websites search engine links on social media |

496 (79.8) 36 (5.8) 35 (5.6) 14 (2.3) 12 (1.9) 8 (1.3) |

|

Gender (N = 619) Female Male Prefer not to say Other |

528 (85.4) 85 (13.8) 4 (0.7) 1 (0.2) |

|

Age (N = 610) ≥ 75 years old 65-74 years old 55-64 years old 45-54 years old 35-44 years old 25-34 years old 18-24 years old |

216 (35.4) 222 (36.4) 99 (16.2) 35 (5.7) 22 (3.6) 12 (2.0) 4 (0.7) |

3.3. Quantitative Analysis

3.4. Qualitative Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Research

4.2. Alignment with Clinical Guidelines and Implications for Practice

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IAM4all-SF | Information Assessment Method for patients and consumers short form version |

| IAM4all | Information Assessment Method for patients and consumers |

| NPS | Net Promoter Score |

Information Assessment Method For All – Short Form (IAM4all-SF)

- I found this lesson relevant. (single select)

- 2.

- I understood the information in this lesson. (single select)

- 3.

- I plan to use what I’ve learned in this lesson. (single select)

- 4.

- I think I will benefit from what I’ve learned in this lesson. (single select)

- 5.

- Is there anything else you would like to tell us about your experience of this lesson or suggestions to improve it? Feel free to comment further on any of your responses if you wish. For example, tell us more about how you will use this lesson or how you expect to benefit. (open text)

- 6.

- Please tell us a bit about yourself. What is your age? (single select)

- 75+

- 65-74

- 55-64

- 45-54

- 35-44

- 25-34

- 18-24

- Under 18

- 7.

- What is your gender? (single select)

- Female

- Male

- Non-binary

- Prefer not to say

- Not listed (please specify) __________

References

- De Lange, E.; Verhaak, P.F.M.; Van Der Meer, K. Prevalence, Presentation and Prognosis of Delirium in Older People in the Population, at Home and in Long Term Care: A Review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013, 28, 127–134. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, L.; Chi, J. Delirium Prevalence in Geriatric Emergency Department Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Emerg Med 2022, 59, 121–128. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Tong, T.; Chignell, M.; Tierney, M.C.; Goldstein, J.; Eagles, D.; Perry, J.J.; McRae, A.; Lang, E.; Hefferon, D.; et al. Prevalence, Management and Outcomes of Unrecognized Delirium in a National Sample of 1,493 Older Emergency Department Patients: How Many Were Sent Home and What Happened to Them? Age Ageing 2022, 51, 16. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira J. e Silva, L.; Berning, M.J.; Stanich, J.A.; Gerberi, D.J.; Murad, M.H.; Han, J.H.; Bellolio, F. Risk Factors for Delirium in Older Adults in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2021, 78, 549–565. [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, N.A.; Fitzgerald, J.; Adamis, D.; Molloy, D.W.; Meagher, D.; Timmons, S. Predictors of Delirium Development in Older Medical Inpatients: Readily Identifiable Factors at Admission. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 64, 775–785. [CrossRef]

- Vasilevskis, E.E.; Han, J.H.; Hughes, C.G.; Ely, E.W. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Delirium across Hospital Settings. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2012, 26, 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Gibb, K.; Seeley, A.; Quinn, T.; Siddiqi, N.; Shenkin, S.; Rockwood, K.; Davis, D. The Consistent Burden in Published Estimates of Delirium Occurrence in Medical Inpatients over Four Decades: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 352–360. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.; Mauch, M.; Seeger, Y.; Burckhardt, M. Experiences of Relatives of Patients with Delirium Due to an Acute Health Event - A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Applied Nursing Research 2023, 73, 151722. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Fick, D.M. Family Caregiver’s Experience of Caring for an Older Adult with Delirium: A Systematic Review. Int J Older People Nurs 2020, 15, e12321. [CrossRef]

- Chuen, V.L.; Chan, A.C.H.; Ma, J.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Chau, V. The Frequency and Quality of Delirium Documentation in Discharge Summaries. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.T.; Tobar, C.; Beddings, C.I.; Vallejo, G.; Fuentes, P. Preventing Delirium in an Acute Hospital Using a Non-Pharmacological Intervention. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 629–634. [CrossRef]

- Rosgen, B.K.; Krewulak, K.D.; Davidson, J.E.; Ely, E.W.; Stelfox, H.T.; Fiest, K.M. Associations between Caregiver-Detected Delirium and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in Family Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.T.; Dhesi, J.K.; Partridge, J.S.L. Distress in Delirium: Causes, Assessment and Management. Eur Geriatr Med 2020, 11, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.K.; Gugliucci, M.R. Delirium and the Family Caregiver: The Need for Evidence-Based Education Interventions. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 345–352. [CrossRef]

- Barbara, A.M.; Dobbins, M.; Haynes, R.B.; Iorio, A.; Lavis, J.N.; Raina, P.; Levinson, A.J. The McMaster Optimal Aging Portal: Usability Evaluation of a Unique Evidence-Based Health Information Website. JMIR Hum Factors 2016, 3, e14. [CrossRef]

- Levinson, A. Understanding Delirium | McMaster Optimal Aging Portal Available online: https://www.mcmasteroptimalaging.org/e-learning/delirium (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Reichheld, F.F. The One Number You Need to Grow. Harv Bus Rev 2003, 81, 46–54.

- Pluye, P.; Granikov, V.; Bartlett, G.; Grad, R.M.; Tang, D.L.; Johnson-Lafleur, J.; Shulha, M.; Galvão, M.C.B.; Ricarte, I.L.M.; Stephenson, R.; et al. Development and Content Validation of the Information Assessment Method for Patients and Consumers. JMIR Res Protoc 2014, 3. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2). Pp. 77-101. ISSN 1478-0887 Available from: Http://Eprints.Uwe.Ac.Uk/11735. Qual Res Psychol 2006, 3. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Fetters, M.D.; Ivankova, N. V. Designing A Mixed Methods Study In Primary Care. The Annals of Family Medicine 2004, 2, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Neil-Sztramko, S.E.; Farran, R.; Watson, S.; Levinson, A.J.; Lavis, J.N.; Iorio, A.; Dobbins, M. If You Build It, Who Will Come? A Description of User Characteristics and Experiences With the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2017, 3. [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.F.; Ayers, S.; Pluye, P.; Grad, R.; Sztramko, R.; Marr, S.; Papaioannou, A.; Clark, S.; Gerantonis, P.; Levinson, A.J. Impact and Perceived Value of IGeriCare E-Learning Among Dementia Care Partners and Others: Pilot Evaluation Using the IAM4all Questionnaire. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e40357. [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Boaz, L.; Jermé, M. Educating Family Caregivers for Older Adults About Delirium: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016, 13, 232–240. [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Avery, J.S.; Boaz, L.; Oswald, D. Psychometric Properties of the Family Caregiver Delirium Knowledge Questionnaire. Res Gerontol Nurs 2015, 8, 198–207. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.P.; Tu, J.; Downie, S.; Heflin, M.T.; McDonald, S.R.; Yanamadala, M. Delirium Education for Geriatric Patients and Their Families: A Quality Improvement Initiative✰. Aging Health Res 2023, 3, 100123. [CrossRef]

- Alaujan, R.; Alhinti, S.; Alharbi, M.; Basakran, F.; Ahmed, M.; Almodaimegh, H. Delirium Knowledge, Risk Factors, and Attitude among General Public in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, a Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alshurtan, K.; Ali Alshammari, F.; Alshammari, A.B.; Alreheili, S.H.; Aljassar, S.; Alessa, J.A.; Al Yateem, H.A.; Almutairi, M.; Altamimi, A.F.; Altisan, H.A. Delirium Knowledge, Risk Factors, and Attitude Among the General Public in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Chu, F.; Tan, M.; Chi, N.C.; Ward, T.; Yuwen, W. Digital Health Interventions to Support Family Caregivers: An Updated Systematic Review. Digit Health 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Crone, C.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Ahmed, I.; Balas, M.C.; Boland, R.; Escobar, J.I.; Heinrich, T.; Jackson-Triche, M.; Levenson, J.L.; Mattison, M.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Delirium. Am J Psychiatry 2025, 182, 880–884. [CrossRef]

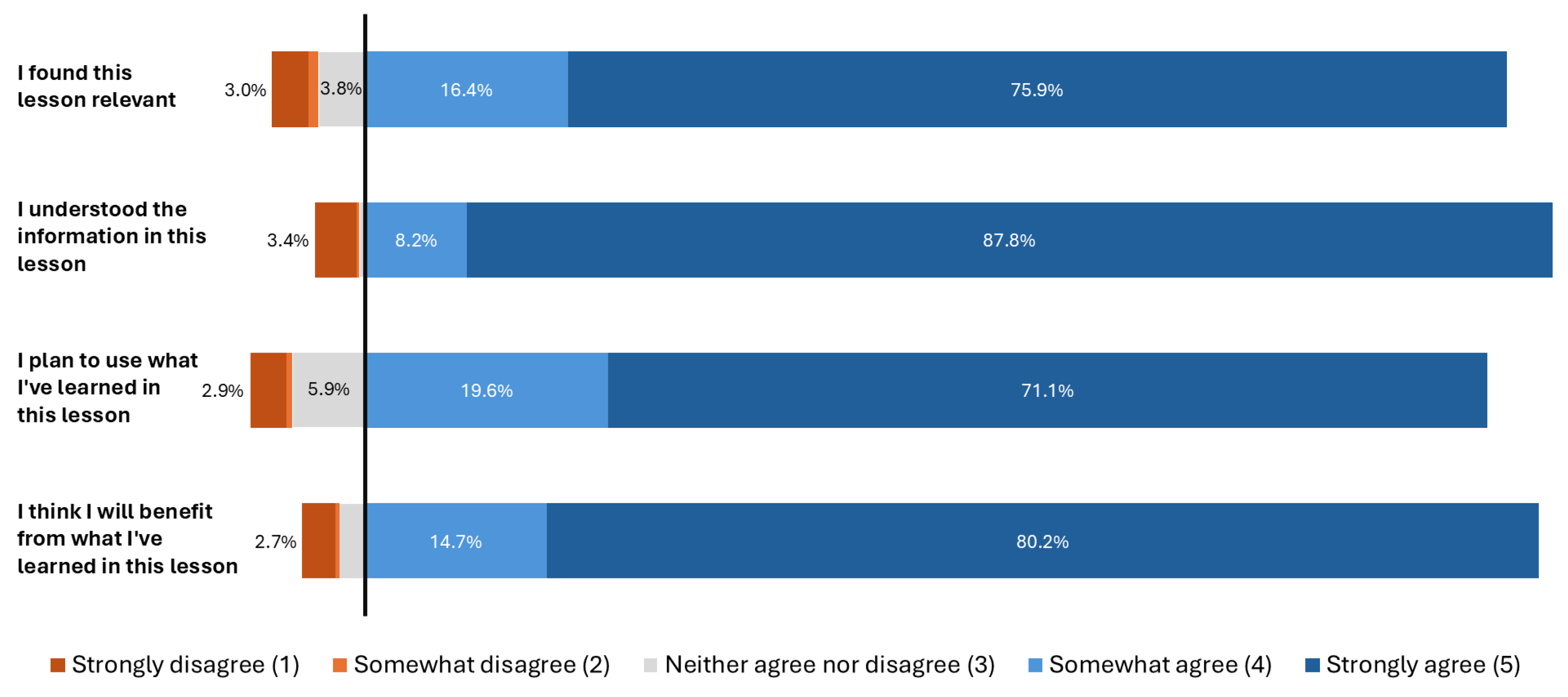

| Responses, n (%) | ||||||

| Strongly disagree (1) | Somewhat disagree (2) | Neither agree nor disagree (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Strongly agree (5) | Total | |

| I found this lesson relevant. | 19 (3.0) | 5 (0.8) | 24 (3.8) | 103 (16.4) | 476 (75.9) | 627 (100) |

| I understood the information in this lesson. | 21 (3.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 51 (8.2) | 548 (87.8) | 624 (100) |

| I plan to use what I've learned in this lesson. | 18 (2.9) | 3 (0.5) | 37 (5.9) | 123 (19.6) | 446 (71.1) | 627 (100) |

| I think I will benefit from what I've learned in this lesson. | 17 (2.7) | 2 (0.3) | 13 (2.1) | 92 (14.7) | 502 (80.2) | 626 (100) |

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mode | Frequency of the Mode (%) | Interquartile Range | |

| I found this lesson relevant. | 4.61 (0.85) | 5.0 | 5 | 476 (63.2) | 0 |

| I understood the information in this lesson. | 4.77 (0.78) | 5.0 | 5 | 548 (72.8) | 0 |

| I plan to use what I've learned in this lesson. | 4.56 (0.86) | 5.0 | 5 | 446 (59.2) | 1 |

| I think I will benefit from what I've learned in this lesson. | 4.69 (0.78) | 5.0 | 5 | 501 (66.5) | 0 |

| Themes | Subthemes |

| 1. Educational value of the lesson | a. Informative and educational b. Better understanding of delirium vs dementia c. Useful to better understanding of prior experiences with delirium d. Refresher/reinforcement of knowledge e. Clarity and organization of content |

| 2. Personal and professional relevance | a. Personal use: Intend to share lesson/knowledge dissemination b. Personal use: Awareness and proactive health management for others c. Personal use: Awareness and proactive health management for themselves d. Professional use: Awareness and proactive health management for patients/clients |

| 3. Suggestions for improvements | a. Technical issues/suggestions b. Formatting issues/suggestions c. Content expansion/suggestions |

| 4. Emotional and psychological impact | a. Relief, clarification and gratitude b. Anxiety, fear and sadness - induced by lesson content c. Anxiety, fear and sadness - induced by experience/recollection |

| 5. Healthcare system and professional support | a. Need for better professional support: General b. Lack of information in the healthcare and professional support system c. Lack of communication in the healthcare and professional support system d. Missed diagnosis/ignored brought up concerns e. This lesson as candidate for training professionals and patients |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).