1. Introduction

Delirium is a neurocognitive disorder marked by an abrupt onset and acute change in cognition, attention, and consciousness, potentially leading to brain failure [

1]. The term "delirium" originates from the Latin word "delirare," meaning "to go out of the furrow" or stray from a straight route, leading to confusion [

2]. In older individuals, delirium is a severe and prevalent issue, increasing the risk of mortality, prolonged hospital stays, falls, and functional decline [

3]. Delirium affects approximately 14% of individuals over 85, and within a year of diagnosis, it is linked to a 40% mortality rate in hospitalized persons [

4]. Research on delirium in older adults is limited, with high under-recognition rates, leading to increased morbidity and mortality [

5,

6]. Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is the most widely used [

7].

Delirium is divided into three subtypes based on psychomotor activity: hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed [

8]. Risk factors include advanced age, cognitive impairment, multiple health conditions, frailty, sensory deprivation, and prior delirium. Causes include substance use, nutritional deficiencies, infections, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances [

8,

9]. Diagnosis is typically made by experts such as geriatricians, ICU specialists, and liaison psychiatrists.

Despite the potential for prevention and treatment, early recognition of delirium is difficult due to a lack of information and awareness [

10]. Medical professionals unfamiliar with patients and not using formal screening methods further hinder detection [

11]. Family caregivers are often better equipped to notice changes in behavior and cognition through their close relationships, providing vital information for accurate diagnosis. However, many lack the knowledge needed to help prevent and manage delirium using non-pharmacological strategies. Research on delirium education for older adults has shown a decrease in its prevalence and improved caregiver understanding [

12] Despite lacking formal training and support, family caregivers play a critical role in elder care. Their close interaction with elderly relatives makes them well-positioned to detect early signs of delirium [

13,

14]. Many tools are developed for caregivers to detect delirium. These include the Family Confusion Assessment Method (FAM-CAM), Sour Seven, and Informant Assessment of Geriatric Delirium (I-AgeD), the Single Question in Delirium (SQiD) and single Screening Question-Delirium (SSQ-Delirium) [

15,

16]. However, the mentioned tools have limitations. For example, the FAM-CAM is not intended to be an independent diagnostic instrument and should be used with expert clinical evaluations to confirm delirium. The Sour Seven has low sensitivity (60%), which may lead to underdiagnosis of delirium. As a yes/no questionnaire, it cannot identify detailed aspects and the severity of the symptoms. There is also variability in ratings between caregivers and nurses, affecting the results' consistency [

16]. I-AgeD has a disadvantage in that the performance can vary depending on the setting and requires familiarity with the patient's baseline state. Finally, both SQiD and SSQ-Delirium have low reliability and generally require follow-up. More importantly, no online version of these tools is considered suitable for the current life of caregivers. To close this gap, developing a web-based delirium detection tool specifically designed for family caregivers of older adults is essential. A web-based tool for delirium detection could empower caregivers, improving early detection and management while reducing healthcare system burdens [

17,

18]. The objective of the present study was to develop a web-based tool for delirium detection tailored to family caregivers. The web-based tool should demonstrate validity and feasibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

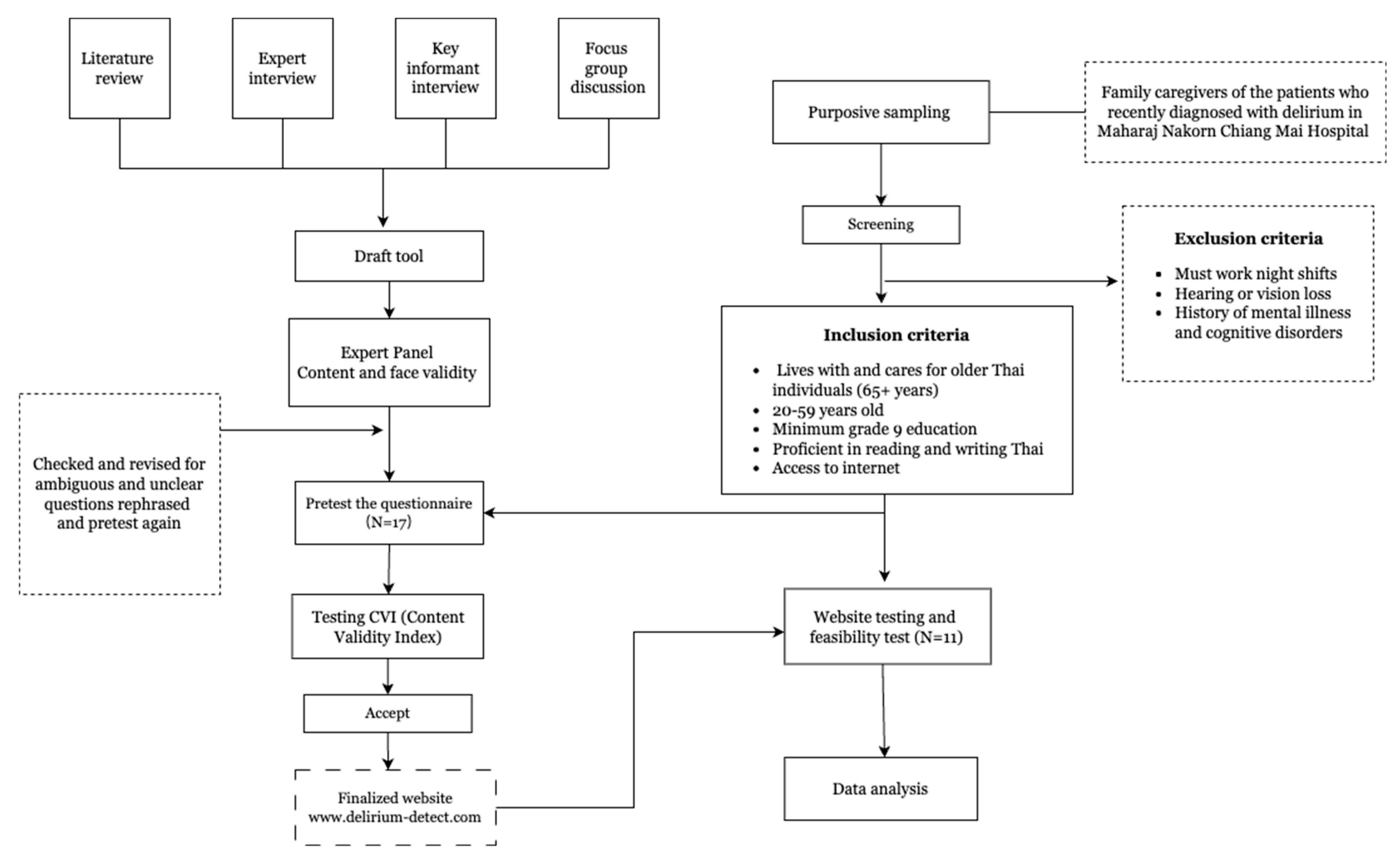

This study employed a research and development design to create a web-based tool for family caregivers to detect delirium in older adults. The initial phase involved designing and developing the

delirium-detetct.com. The process followed a structured sequence as outlined in the framework in

Figure 1.

A review of existing literature on delirium revealed that over 60% of cases go undetected in hospitals, especially in intensive care units, due to knowledge gaps [

19]. Early detection using reliable tools could reduce adverse outcomes and patient falls [

20]. Family caregivers often experience emotional distress from observing delirium symptoms, which could be mitigated with educational programs [

21,

22]. Web-based tools were highlighted for their potential to improve delirium knowledge and detection [

10,

16,

23].

- 2.

Expert Interviews:

Geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, nurses, and occupational therapists were interviewed to identify key delirium symptoms and assessment domains, contributing to relevant questionnaire items.

- 3.

Key Informant Interviews:

Family caregivers and experienced nurses were interviewed to gather insights on user needs and tool usability.

- 4.

Focus Group Discussions:

Ten participants, including family caregivers, nurses, and healthcare professionals, discussed the tool's interface, features, and cultural relevance.

A draft tool featuring a symptom checklist, care tips, and a downloadable daily screening questionnaire was created.

2.2. Tool Development

The core of the delirium-detect is a 22-item questionnaire assessing key delirium symptoms, including cognitive function, consciousness, perceptual and emotional disturbances, psychomotor and behavioral issues, and temporal aspects.

Originally based on the Sour Seven and DSM-5, the questionnaire used yes/no questions to identify symptoms but couldn't assess severity or symptom duration. To overcome this, it was redesigned with multiple-choice questions, including prompts to capture symptom frequency and calculate a delirium severity score.

Natural, simple language was used to help participants choose the best options reflecting their observations. Participants were instructed to base their answers on the period since they first noticed changes in the patient.

Each of the 22 items is evaluated for frequency, duration, and onset. Frequency is scored from "Often" (3 points) to "No change" (0 points), and similar scales are applied for duration and onset, with "Not Sure" options excluded from scoring.

Table 1.

Symptom-related questions, frequency answers, and scoring.

Table 1.

Symptom-related questions, frequency answers, and scoring.

| Symptom-Related Questions |

Often (3) |

Sometimes (2) |

Rarely (1) |

No Change (0) |

Not Sure |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 2.

Spatial disorientation |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

- 3.

Disorientation towards individuals |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 4.

Inattentiveness during interactions |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 5.

Comprehension and response accuracy |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 6.

Maintaining topic relevance |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 7.

Nocturnal behavior changes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 8.

Daytime sleep pattern alterations |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 9.

Mood fluctuations |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 10.

Indications of apathy |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 11.

Slowed cognitive processes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 12.

Variability in alertness levels |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 13.

Reduced spontaneity |

X |

X |

X |

|

N/A |

- 14.

Coherence in verbal expression |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 15.

Hallucinations or illusions |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 16.

Memory impairments |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 17.

Difficulty organizing thoughts/tasks |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 18.

Recall of surroundings |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 19.

Adherence to instructions |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

- 22.

Fluctuations in awareness and behavior |

X |

X |

|

X |

N/A |

| |

- 20.

alic>25. Duration of Observed Symptoms

|

Last 24

hours (4)

|

Few days (3) |

One week ago (2) |

Less than 1 month (1) |

More than 1 month (0) |

Not Sure |

| Responses |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

- 21.

Onset of Symptoms |

Sudden change (4) |

Changes in 1 day (3) |

Days or weeks (2) |

Months (1) |

Not Sure |

|

| Responses |

X |

X |

X |

X |

N/A |

|

2.3. Validation and Testing

A panel of geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, nurses, and occupational therapists validated the content of the "delirium-detect." Their feedback refined the tool, emphasizing delirium symptoms' acute onset and fluctuating nature. The Content Validity Index (CVI) scored a perfect 1.00 for all items [

24]. During the development of the delirium detection tool, including the questionnaire and internet interface, the expert panel assessed face validity, improving readability and comprehension. A pretest with 17 participants from February to June 2024 prompted further refinements. A subsequent pilot test with 11 participants evaluated the tool's practical usability.

2.4. Participants

Participants were recruited from Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital using purposive sampling. They were family caregivers of older adults recently diagnosed with delirium and hospitalized. The initial target was 30 participants; however, 17 joined the pretest from February 27 to June 26, with 11 completing the final pilot test. Participants accessed the tool via a website link and completed a satisfaction and feasibility survey afterward.

Inclusion Criteria: Caregivers living with older Thai individuals aged 65 and above, aged 20-59 years, with at least a grade 9 education, able to read and write Thai, and having internet access.

Exclusion Criteria: Individuals working night shifts, those with hearing or vision impairments affecting symptom assessment, and those with a history of mental illness or cognitive disorders.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic data collected included gender, education level, family income, marital status, and caregiver relationship. After using the tool, the feasibility analysis focused on overall satisfaction, including the questionnaire, time spent, and website usability. Satisfaction survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics (percentage, mean, standard deviation). Participants' responses to delirium detection questions were presented as percentages aligned with DSM-5 criteria. Total delirium detection scores reported anonymously, were compared to the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) algorithms [

25].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Analysis

In this research project to improve delirium detection for family caregivers, the pretest phase involved 17 participants, of whom 11 completed the final pilot test. Demographic analysis revealed insights into the caregiver population’s diverse backgrounds and experiences.

As shown in

Table 2, 82% of participants were female, reflecting the prevalence of women in caregiving roles. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 59 years, with most between 30 and 40. Among the participants, 45% were married, and 55% were single. Additionally, 36% were sons or daughters, 55% were grandsons or granddaughters, and the rest were siblings or others.

3.2. Participants' Response to the Tool

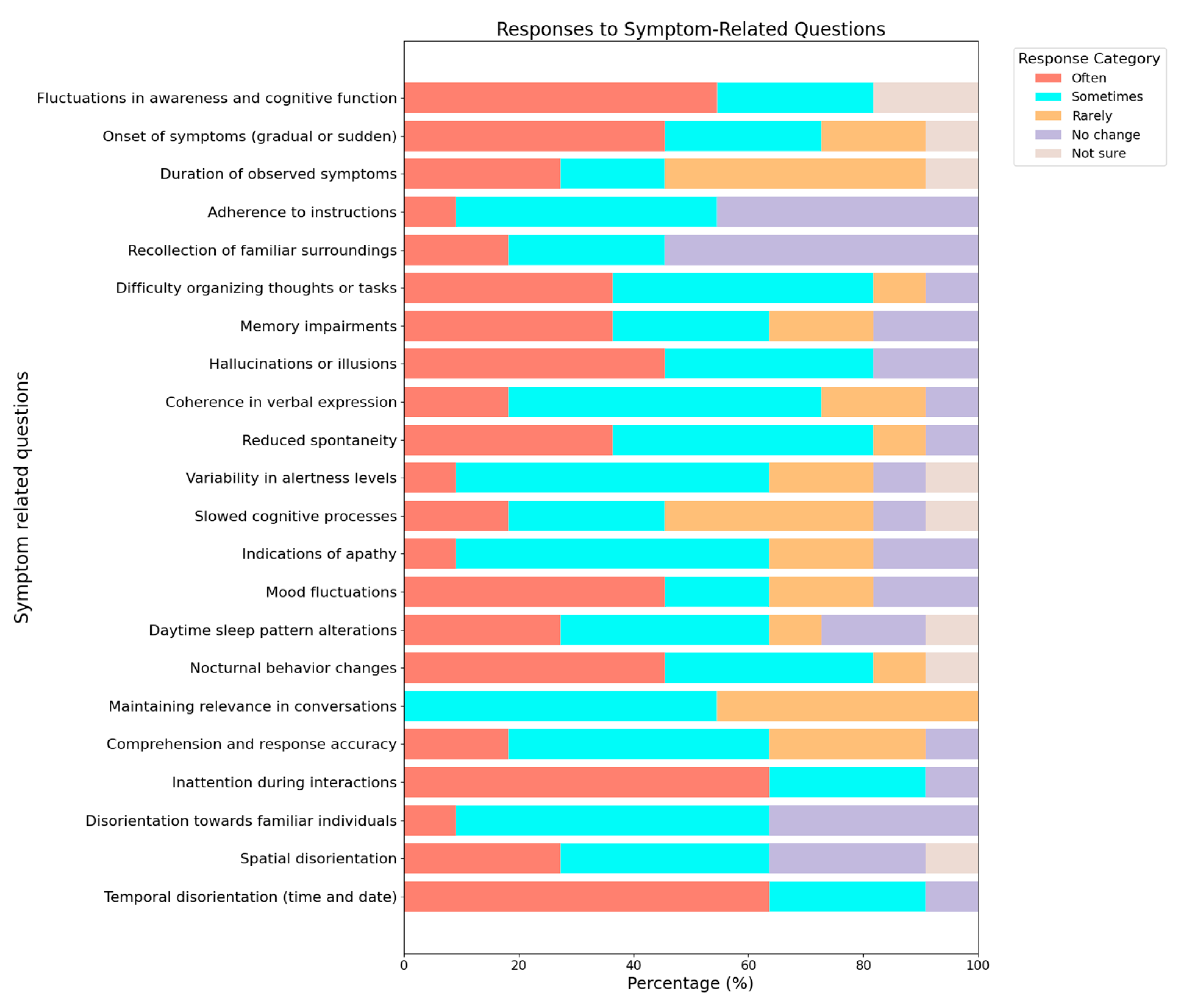

Participants' responses to the delirium detection questionnaire revealed significant insights into the prevalence and nature of various delirium-related symptoms (

Figure 2).

These insights are crucial for refining the delirium detection tool to address common challenges. By focusing on symptoms like disorientation, inattention, sleep disturbances, mood fluctuations, and cognitive difficulties, the tool can better support family caregivers, enhancing their ability to manage delirium and improve care quality for their loved ones.

3.3. Delirium Score for Participants’ Responses

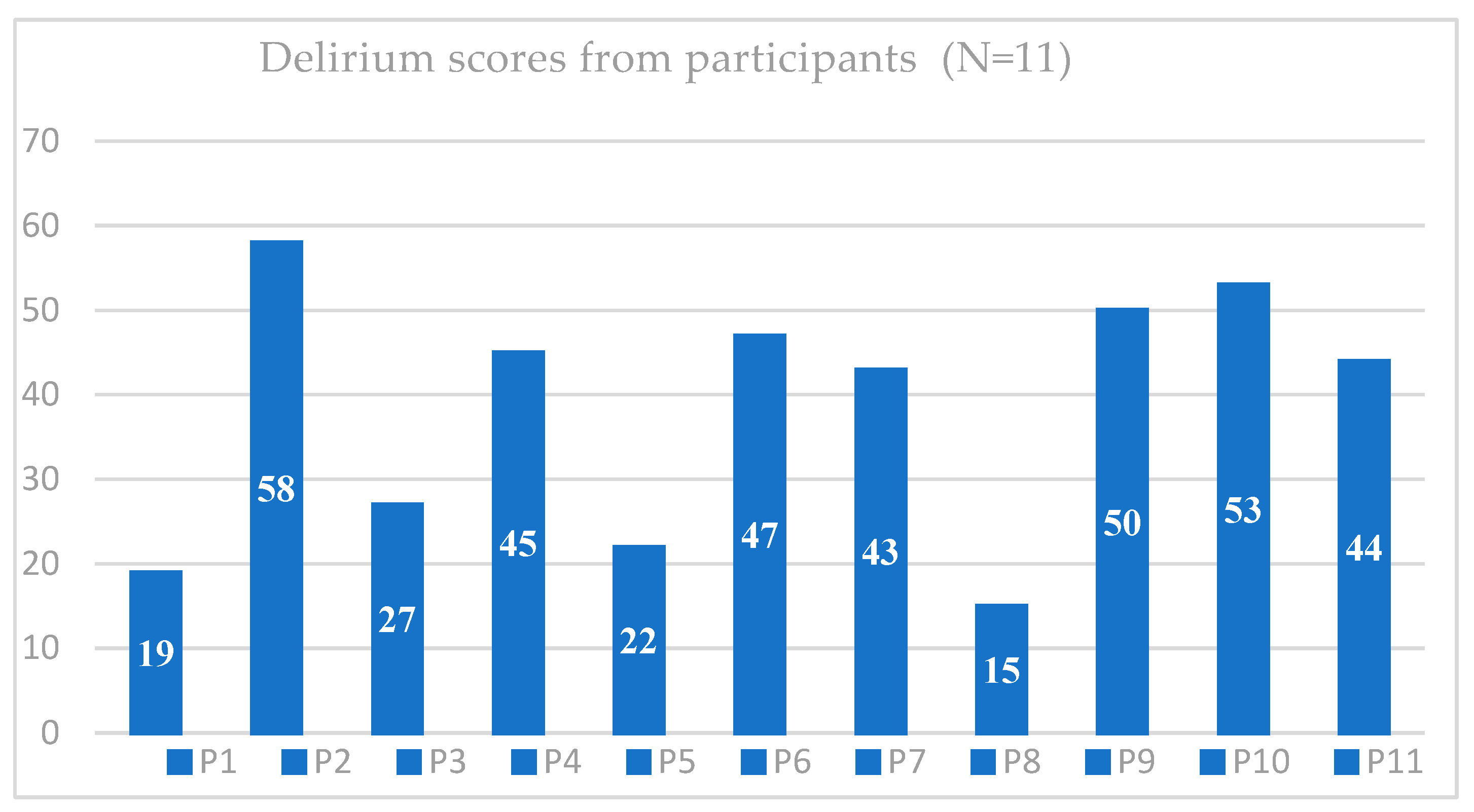

Table 3 shows that all 11 participants endorsed the DSM-5 criteria for delirium (criteria A, B, and C), consistently indicating disturbances in attention, awareness, acute onset, fluctuations, and cognitive disturbances. Some participants reported uncertainty or no change in certain items, highlighting areas with absent or less noticeable symptoms.

The endorsement of delirium symptoms by all participants indicated their presence per DSM-5 criteria, suggesting that the screening tool effectively captures essential diagnostic elements. The agreement between positive responses from the "delirium-detect" tool and clinician diagnoses confirmed its criterion validity.

Participants reporting no symptoms had scores ranging from 0 to 5. According to DSM-5, key delirium symptoms—disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognition—can be quantified. Scores of 6 to 10 indicate varying severity, while scores over seven on the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) confirm delirium with acute onset and symptom fluctuation.

Figure 3 shows total scores ranging from 21 to 58, reflecting varying severity levels. Higher scores (P2: 58, P10: 53, P9: 50) suggest severe symptoms, while lower scores (P8: 15, P1:19, P5: 22) indicate milder symptoms. The prevalence of disorientation, inattention, sleep disturbances, and mood fluctuations highlights the multifaceted nature of delirium, particularly noted by family caregivers. These results underscore the need for practical tools for early detection and management of delirium.

3.4. Feasibility of the Web-Based Tool

As

Table 4 listed, the tool received high satisfaction rates, with 54.5% "Liked" and 18.2% "Liked it a lot." Ease of use was reported as "Very easy" by 36.4% and "Easy" by another 36.4%. Understanding of the content was generally high, with most participants reporting good comprehension. The average time spent on the tool was 9.09 minutes, with the questionnaire taking approximately 5 minutes to complete.

3.5. The Interface of the Website

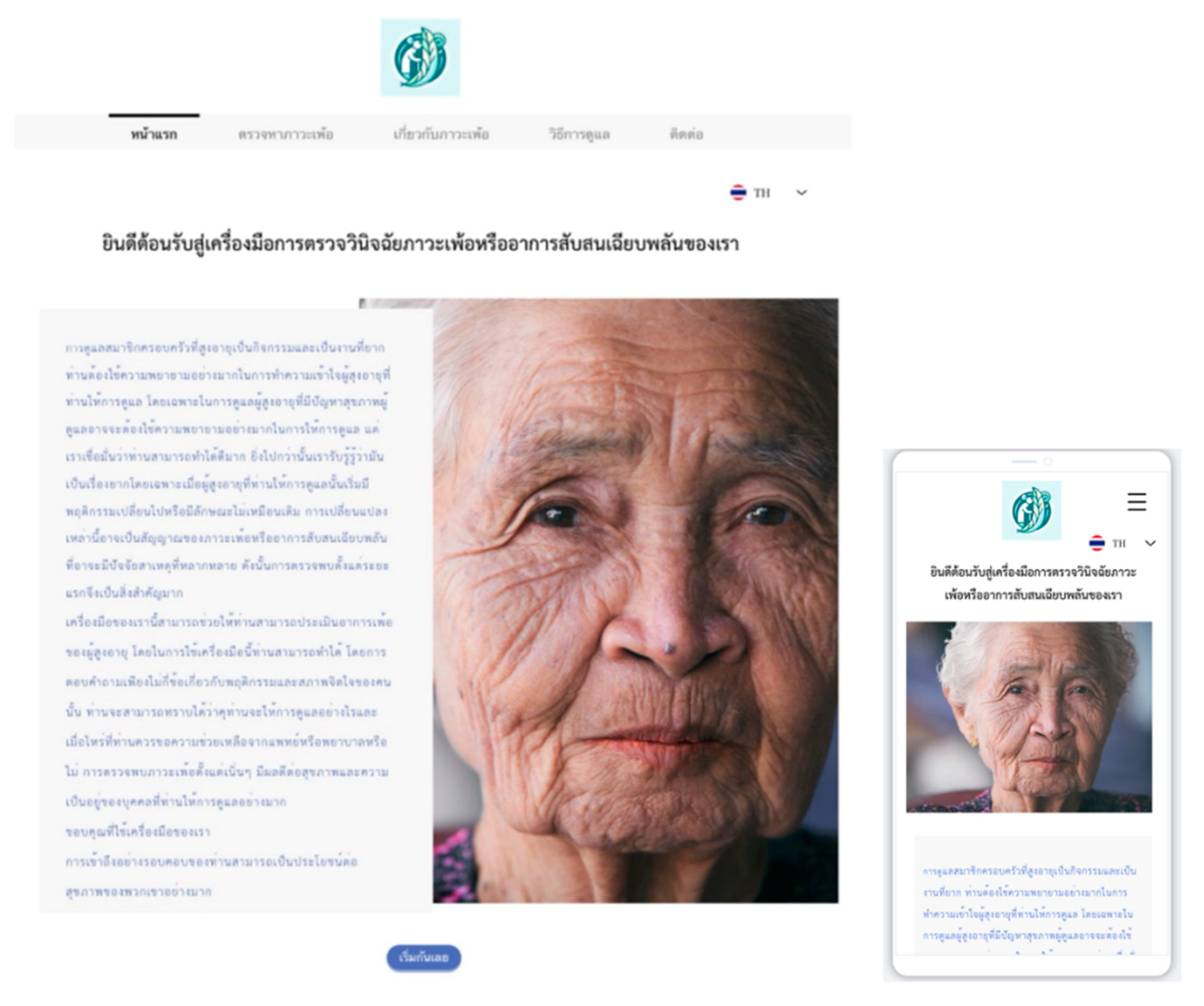

The "delirium-detect" interface features user-friendly tools for family caregivers:

Home Page: Introduces the tool and includes an uncomplicated menu.

Delirium Detection Questionnaire Page: Contains 22 multiple-choice questions with guided assessments, conditional navigation, progress indicators, and completion alerts.

Importance of Early Detection Page: Provides educational resources and a downloadable PDF questionnaire, emphasizing real-time monitoring.

Home Care Tips: Offers practical caregiving advice.

Contact Page: Lists contact information and outlines plans for future AI integration for online support.

Since its launch,

www.delirium-detect.com has attracted users from 15 countries, with 48% using mobile, 47% desktop, and 5% tablets. It supports two languages and features Google Translate, demonstrating high content validity and usability for family caregivers.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop and evaluate a web-based tool, 'Delirium-Detect,' designed for family caregivers to detect delirium in older adults. The tool's development involved comprehensive literature reviews, expert consultations, and pilot testing to ensure validity, usability, and effectiveness. The results indicated that 'Delirium-Detect' is a feasible, user-friendly, and effective tool for early detection of delirium symptoms. The demographic analysis of participants revealed a diverse caregiver population, highlighting the necessity for an adaptable and accessible tool. The gender distribution aligned with the known prevalence of women in caregiving roles, and the varied age, educational, and income levels underscored the tool's design to cater to a broad user base. Participants' responses to the delirium detection questionnaire provided significant insights into the prevalence and nature of delirium symptoms. High temporal disorientation, inattention, sleep pattern changes, alertness variability, mood fluctuations, and cognitive challenges were commonly reported. These findings are consistent with existing literature on delirium symptoms, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive and multifaceted assessment approach. The feasibility study demonstrated high satisfaction rates and ease of use, with most participants finding the tool easy to navigate and understand. The time-efficient design further supports its integration into daily caregiving routines. The website's global reach highlights its potential for widespread use, making it a valuable resource for caregivers worldwide.

4.1. Compared with Other Existing Web-Based Tools

Existing web-based delirium detection tools, such as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), DelApp, and the Electronic Delirium Assessment (e-DA), primarily target healthcare professionals and require clinical expertise, making them unsuitable for family caregivers without medical training. In contrast, "delirium-detect" offers a user-friendly interface with straightforward language, simplifying medical jargon and focusing on observable behaviors. This approach makes it accessible to non-professionals and fills a critical gap in delirium management within community settings.

4.2. Implications of the Research

The findings of this study have several important implications for the early detection and management of delirium in older adults. Delirium is often under-detected due to time-consuming assessments and ambiguity in diagnosing responsibilities. ”Delirium-detect” addresses these issues by enabling family caregivers to complete the questionnaire within approximately 5 minutes. This efficiency helps caregivers identify potential delirium symptoms early and receive timely alerts, allowing them to take proactive measures and seek professional help when necessary. Consequently, this tool enhances the early detection and management of delirium, improving outcomes for older adults.

4.3. Limitations and Further Development

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. The participant pool, consisting only of family caregivers of diagnosed delirium patients over 65, lacked representation from spouses, who constitute about 30% of caregivers. This absence may have influenced findings, as spouses and children have different caregiving experiences. Additionally, the age range of caregivers (20-59 years) excluded older caregivers, who were often reluctant to participate in online research due to hesitancy in engaging in online activities. Although the tool includes questions addressing acute onset and fluctuating symptoms—critical indicators of delirium—it does not yet assign weighted importance to these responses. This may limit the tool’s ability to differentiate between delirium and dementia, which often share overlapping symptoms.

Future development should focus on completing the website's interactive functions, such as adaptive questioning and providing scores and suggestions based on responses. Additionally, assigning weights to the questions about acute onset and fluctuating symptoms will improve the tool's ability to distinguish between delirium and dementia. This enhancement will increase the tool’s accuracy and offer more reliable feedback to caregivers. Expanding the tool's functionality to include interactive features and professional healthcare service links will empower caregivers and improve delirium management. Enhancing the tool and gathering more user data will improve health outcomes for older adults experiencing delirium.

Future research should aim to validate the tool’s effectiveness across more extensive and diverse populations. Additionally, the scoring criteria for a positive delirium screen should be established through rigorous validation.

Additionally, exploring the tool's impact on patient outcomes and caregiver burden over extended periods would provide valuable insights into its long-term benefits. Further development in this technological era should include integrating artificial intelligence to offer more personalized support and expanding language options to enhance global accessibility.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the development of a web-based tool, the delirium-detect, specifically designed for family caregivers in Thailand to detect delirium in older people. The tool, validated by experts and refined through pretesting and pilot testing, covers 22 delirium symptoms. It demonstrated high content and established criterion validity, with most symptoms endorsed by participants. User feedback highlighted high satisfaction and ease of use, with the tool being quick to complete. Future improvements will focus on refining less sensitive items, adding real-time monitoring and interactive features, and further validation with more extensive and diverse groups to ensure robustness and integration into healthcare systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.delirium-detect.com, the delirium detection questionnaires both in Thai and English.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.H., N.W., T.W., D.T., P.R., and J.T.; software, J.H., and T.W.; validation, J.H., N.W., T.W., D.T., P.R., and J.T.; formal analysis, J.H., and T.W.; investigation, J.H.; resources, N.W., T.W.; data curation, J.H., T.W., and N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H., T.W., and N.W; writing—review and editing, J.H., N.W., T.W., D.T, P.R., and J.T; visualization, J.H., T.W.; supervision, N.W.; project administration, N.W. and T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (study code, PSY-2566-0466 and date of approval, January 15th, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

According to the policy implemented during this study, the ethics committee does not permit the authors to share the data with other entities. The datasets used and/or analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the liaison psychiatry team of the Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oh, E.S.; Fong, T.G.; Hshieh, T.T.; Inouye, S.K. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.E.; Mart, M.F.; Cunningham, C.; Shehabi, Y.; Girard, T.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Ely, E.W. Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5; American psychiatric association Washington, DC: 2013; Volume 5.

- Panitchote, A. , Tangvoraphonkchai, K., Suebsoh, N. et al.. Under-recognition of delirium in older adults by nurses in the intensive care unit setting. Aging Clin Exp Res 2015, 27, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praditsuwan, R., & Srinonprasert, V. . Unrecognized delirium is prevalent among older patients Admitted to general medical wards and Lead to higher mortality rate. J Med Assoc Thai, 2016, 99(8).

- Nahathai Wongpakaran, T.W.P.B., Manee Pinyopornpanish, Benchalak Maneeton, Peerasak Lerttrakarnnon3, Kasem Uttawichai3 and Surin Jiraniramai3. Diagnosing delirium in elderly Thai patients: Utilization of the CAM algorithm. BMC Family Practice 2011 2011, 12:65.

- Thom R., P.; Levy-Carrick, N.C.; Bui, M. , & Silbersweig, D.. Delirium. American Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi, E.S.; Greaves, D.; Boord, M.S.; Davis, D.; Knayfati, S.; Astley, J.M.; Sharman, R.L.S.; Goodwin, S.I.; Keage, H.A.D. How do predisposing factors differ between delirium motor subtypes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detroyer, E.; Dobbels, F.; Debonnaire, D.; Irving, K.; Teodorczuk, A.; Fick, D.M.; Joosten, E.; Milisen, K. The effect of an interactive delirium e-learning tool on healthcare workers' delirium recognition, knowledge and strain in caring for delirious patients: a pilot pre-test/post-test study. BMC Med Educ 2016, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Dawson, S. Evaluation of student nurses' perception of preparedness for oral medication administration in clinical practice: a collaborative study. Nurse Educ Today 2014, 34, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Boaz, L.; Jerme, M. Educating Family Caregivers for Older Adults About Delirium: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016, 13, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intaput, P.; Lawang, W.; Tassanatanachai, A.; Suksawat, S.; RachaneeSunsern. The Needs of Thai family caregivers and their readiness to provide care for people with psychosis: a qualitative approach. Health Research 2023, Volume 37, 326-332.

- Warin, H. , & Portawin, T. The Development of Caregivers’ Community Engagement-based Guidelines for Elderly People with Dementia. Social Work 2022, 30, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, G.W.; Xie, Q.; Tong, J.; Liu, L.Z.; Jiang, X.; Si, L. Early Intervention of Perioperative Delirium in Older Patients (>60 years) with Hip Fracture: A Randomized Controlled Study. Orthop Surg 2022, 14, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosgen, B.; Krewulak, K.; Demiantschuk, D.; Ely, E.W.; Davidson, J.E.; Stelfox, H.T.; Fiest, K.M. Validation of Caregiver-Centered Delirium Detection Tools: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018, 66, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.; Simões, M.; Fernandes, L. 2847–The role of family/caregivers in management of delirium. European Psychiatry 2013, 28, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Craswell, A.; Bail, K.; Compton, R.M.; Hughes, M.; Sorwar, G.; Baker, J.; Greenhill, J.; Shinners, L.; Nichols, B. A Toolkit for Delirium Identification and Promoting Partnerships Between Carers and Nurses: A Pilot Pre–Post Feasibility Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.H.; Chang, H.R.; Liu, M.F.; Chen, K.H.; Shen Hsiao, S.T.; Traynor, V. Recognizing Intensive Care Unit Delirium: Are Critical Care Nurses Ready? J Nurs Res 2022, 30, e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaa, C.A.; Akintade, B.F. Implementing Delirium Screening in an Intermediate Care Unit. J Dr Nurs Pract 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.M.; Gallagher, J.; Albuquerque, A.; Tabloski, P.; Lee, H.J.; Gleason, L.; Weiner, L.S.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Jones, R.N.; Inouye, S.K.; et al. Perspectives on the Delirium Experience and Its Burden: Common Themes Among Older Patients, Their Family Caregivers, and Nurses. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Bull, M.J.; Wesley Ely, E.; Davidson, J.E.; Stelfox, H.T.; Fiest, K.M. Effectiveness of an intensive care unit family education intervention on delirium knowledge: a pre-test post-test quasi-experimental study. Can J Anaesth 2020, 67, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs-Spanjers, K.R.; Hegge, H.H.; Jansen, C.J.; Hoogendoorn, E.; de Rooij, S.E. A Web-Based Serious Game on Delirium as an Educational Intervention for Medical Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2018, 6, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.K.; van Dyck, C.H.; Alessi, C.A.; Balkin, S.; Siegal, A.P.; Horwitz, R.I. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Annals of internal medicine 1990, 113, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).