1. Introduction

Restoration of teeth is essential for a healthy oral cavity in particular and overall health of an individual in general. This restoration can be either direct in the form of fillings or indirect restorations such as crowns and bridges, inlays, onlays, posts, core build up, veneers and so on. Indirect restorations require a good cement to bond them firmly with the tooth surface. Over last few decades adhesive cements has evolved greatly and there has been tremendous achievement in improving the biomechanical properties of these cements. Various cements are used for cementation such as zinc phosphate, zinc-oxide eugenol, zinc polycarboxylate, glass ionomer cement and the latest is resin cement. They were first introduced in dentistry in 1970s and since then have undergone a lot of changes and today different types of resin cements are available.

Generally, resin cements consist of an organic resin matrix, inorganic filler particles and these two are held together and bonded by a coupling agent [

1]. Silane bonds between the functional groups (eg- hydroxyl, methoxy) of inorganic filler particles as well as unsaturated organic groups (methacrylate group) of organic resin matrix [

2,

3]. Stronger the bond between the resin matrix and the filler particles better will be the cement. A weak bond is often due to hydrolysis of the coupling agent [

4] therefore a hydrophobic coupling agent is preferred [

5]. Resin cements are preferred because they are biocompatible [

6], have better aesthetics and adhesion [

7], good marginal adaptation [

8], better mechanical and physical properties (flexural strength and elastic modulus) compared to other cements [

9], low solubility [

10,

11], superior bond strength [

12] and long lasting . Like other luting cements, resin cements too have their own shortcomings. Some of the problems with resin cements are polymerization shrinkage, staining, post-operative sensitivity, microleakage, staining, fracture etc. They are used for cementation of full-cast metal crowns, ceramic crowns, zirconia crowns and bridges, indirect composite restorations, traditional metal–ceramic prosthesis, metal and glass fibre-post, core build-up, implant-supported crowns and bridges, and ceramic veneers [

13]. A successful restoration is dependent not only on the tooth preparation and the restoration design but also on the adhesive cement used. A restoration with good tooth preparation and correct design might also fail if the resin cement being used fails, which could be due to reasons such as polymerization shrinkage[

14,

15], micro-fracture of resin cement [

16], plastic deformation of resin cement [

17,

18], incomplete polymerization of resin cement[

19,

20] and hydrolysis of coupling agent [

21].

Failures of restoration can be broadly categorized as cohesive, adhesive and mixed failures. Cohesive failures are because of failures related to resin cements. Hence it is very important to understand the chemistry of the resin cements in order to predict their interaction with the tooth structure and the restoration and understand their bonding mechanism to further improvise their adhesive property [

22]. The most common analysing methods in doing so are scanning electron microscopy along with energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). SEM use is indicated in investigating the surface morphology, topography and irregularities of materials such as minerals, alloys, ceramics, polymers, glasses, powders, etc. [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. SEM is a unique method of gathering information a material’s surface by means of high-resolution images. It also creates a three-dimensional image by combining targeted beam of ions and scanning electron based analysis technique. A focused beam of electrons is used to scan the surface of a specimen and generate images at a much greater resolution compared to optical microscopy [

29]. In this technique, fine powder of the sample is coated most commonly with gold. Palladium can also be used. This coating is ultrathin and is deposited using low vacuum sputter or by high vacuum evaporation [

30]. This prevents artefacts of the images. The artefacts could be formed in non-conducting samples which gets charged when exposed to electron beam so the coating converts the sample into conducting one. According to Saghiri et al [

31], there are 2 functions of these coatings. Firstly to enhance signal and surface resolution especially for samples with low atomic numbers and secondly, resolution is improved due to enhanced emission of backscattering and secondary electrons near the surface as a result a much clear image of surface is obtained. EDX on the other hand is a qualitative and quantitative X-ray micro analytical technique used in chemical analysis to understand the elemental composition and quantitative components of samples [

32]. It utilizes characteristic X-rays emitted by the sample during SEM imaging [

33]

. It is quick, accurate and does analysis on micron scale without destructive effects. FTIR helps in studying the chemical structure, bond strength of the specimens and is an accurate, fast and convenient approach of quantitative analysis. It works by scanning the sample and exploring chemical properties by means of infrared light. It works on the principle of absorption of IR radiation as most of the organic and inorganic components are active in IR range so when the rays are absorbed the photon from lower energy orbit moves to the higher energy orbit, resulting in vibration of the molecular bond [

34]. It generates a spectrum of infrared absorption that produces sample’s profile which is similar to the exclusive fingerprint of the molecule [

35].

Another important aspect of good cement is its inorganic component which provides strength to the cement in withstanding against active functional forces and prevents its failure. Traditionally, fillers like silica, quartz, fine glass particles, hydroxyapatite crystals etc. have been used for a long time but the search for new fillers, which could perform better than previous fillers and also overcome their shortcomings, is underway. Off late, zirconia and diamond nanoparticles as fillers have been of great interest among research professionals and clinicians due their excellent biomechanical properties. Studies have shown promising results with nanozirconia use in resin cement [

36,

37,

38]. Similarly, nanodiamond has been tested with PMMA denture base resin and polymer composites and has significantly improved its mechanical properties [

39,

40,

41].

In order to have a long lasting and successful restoration the understanding of the adhesive cements, its chemical nature, its interaction with the teeth and the restorations and its behavioural changes upon addition of inorganic filler particles is of great importance.

2. Materials and Methods

The materials used in this study were RelyX U200 dual-cure resin cement (3M ESPE), zirconia oxide nanoparticles (Vedayukt India Pvt Ltd), diamond nanoparticles (Vedayukt India Pvt Ltd) and 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate coupling agent (Tokyo Chemical Industry (India) Pvt Ltd). Three groups were prepared using these materials. The groups were as follows. Group 1: Commercial dual-cure resin cement, group 2: 10% Nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement, group 3: 10% Nanodiamond modified dual-cure resin cement. Nanozirconia and nanodiamond, each were added 10% volume to commercially available dual-cure resin cement RelyX U200. The volume was measured by using graduated test tube.

Group 1- 11g of 100% RelyX U200 dual-cure resin cement was used as the control group. The base and catalyst were measured in small increments in equal quantities using digital weighing machine (Precision balance, LWL Germany, Model: LB-210S) and mixed manually over the glass slab to obtain a uniform mix.

Group 2- 10% nanozirconia particles were mixed with coupling agent on a glass slab. This mixture was then added to base paste of commercial dual-cure resin cement (RelyX U200) taken on another glass slab. This base paste and the catalyst paste were then measured in small increments in equal quantity using digital weighing machine (Precision balance, LWL Germany, Model: LB-210S) and were mixed well on the glass slab and loaded in the moulds, avoiding air bubbles and voids formation.

Group 3- Commercially available dual-cure resin cement (RelyX U200) was taken 90% by volume which is equivalent to 1067mg and 10% by volume nanodiamiond was measured using a graduated test tube. Similar process as that of group 2 preparation was followed to prepare group 3 using 10% nanodiamond particles by volume and the samples were stored at room temperature.

Analysis by SEM-EDX technique-

After the initial set of all the groups, samples were d crushed with pestle and mortar into fine powder and incubated at 37⁰C and 100% humidity for 24 hours in an incubator. The fine powder of the samples was coated with gold metal. After this process, samples are examined under an electron microscope at 1000x, 5000x, 10,000x and 50000x magnifications followed by EDS analysis ((SEM-EDS, Quanta FEG 450 USM).

Analysis by FTIR technique-

For FTIR analysis, same powder form sample was made into KBr pellet in a 1:10 ratio using samples and potassium bromide. The pellet was further analysed for chemical composition.

Test.

3. Results

Group 1

Figure 1.

group 1 image at 10000x.

Figure 1.

group 1 image at 10000x.

Table 1.

Analysis of group 2 at 10000x SEM magnification.

Table 1.

Analysis of group 2 at 10000x SEM magnification.

| |

Element

Number |

Element

Symbol |

Element

Name |

Atomic

Conc. |

Weight

Conc. |

| |

6 |

C |

Carbon |

33.511 |

22.200 |

| |

8 |

O |

Oxygen |

41.310 |

36.047 |

| |

13 |

Al |

Aluminum |

4.773 |

7.100 |

| |

14 |

Si |

Silicon |

14.780 |

22.900 |

| |

38 |

Sr |

Strontium |

1.614 |

7.800 |

| |

40 |

Zr |

Zirconium |

4.012 |

3.953 |

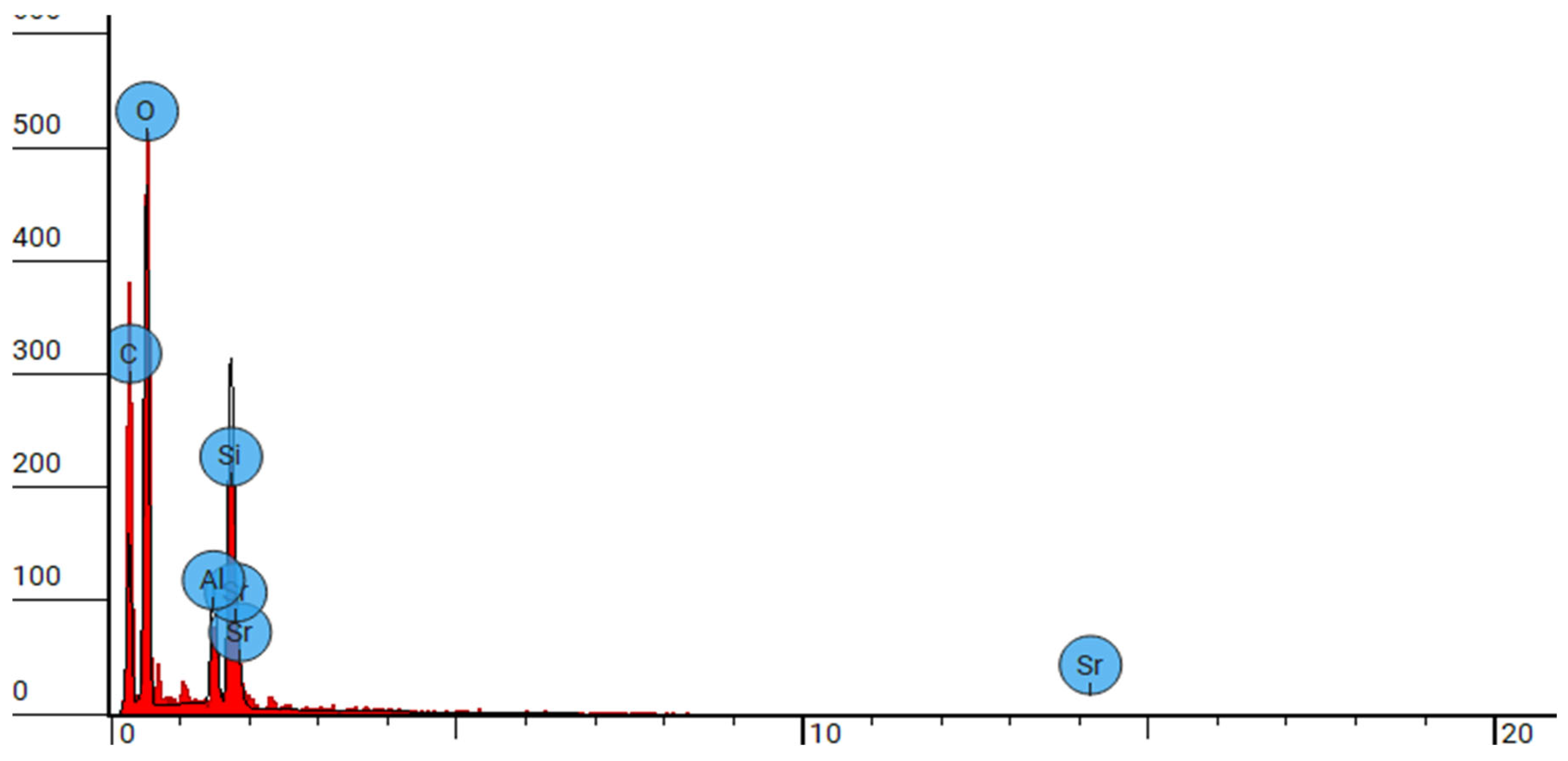

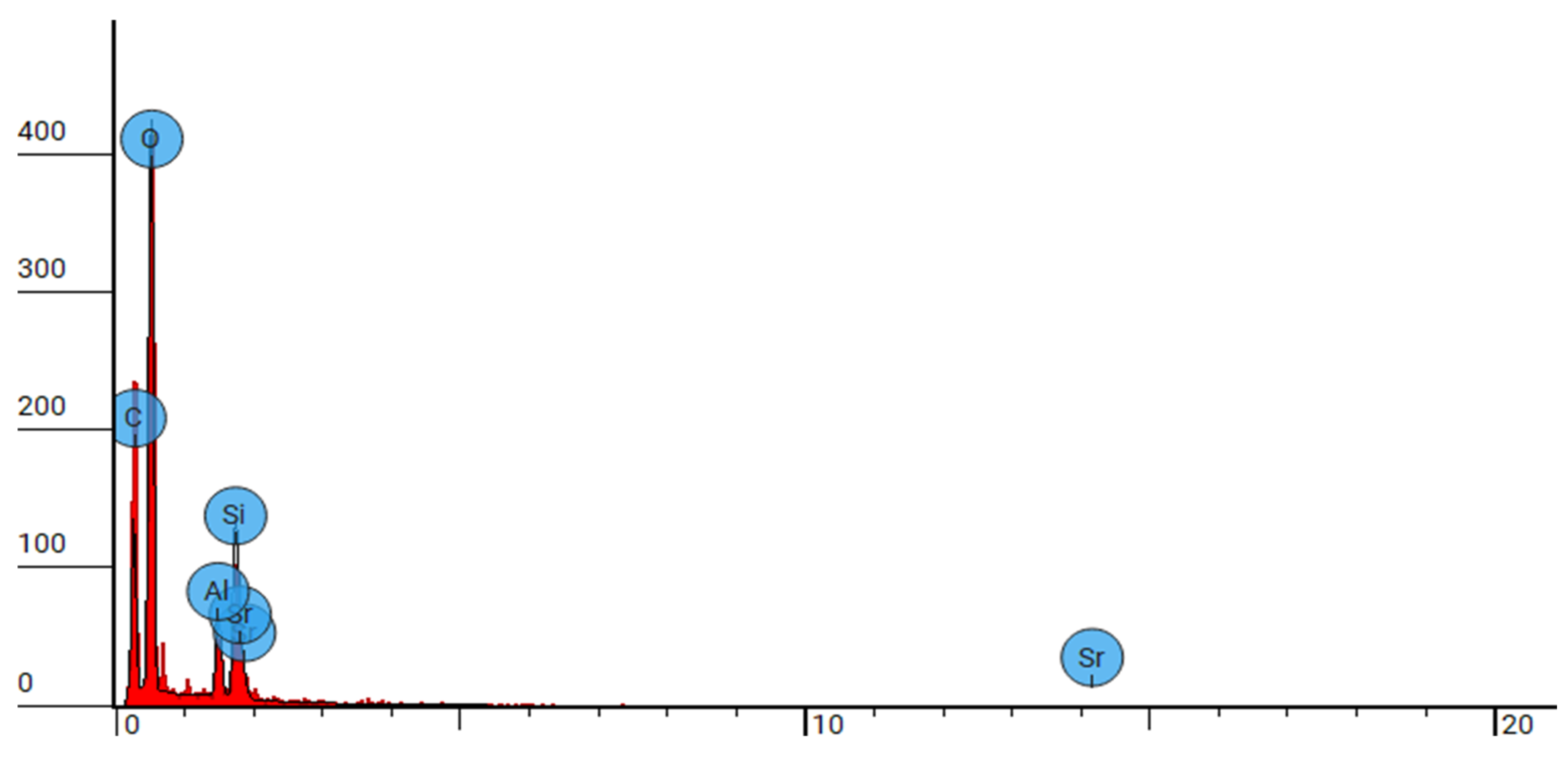

Figure 2.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 2 at 10000x.

Figure 2.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 2 at 10000x.

Group 2

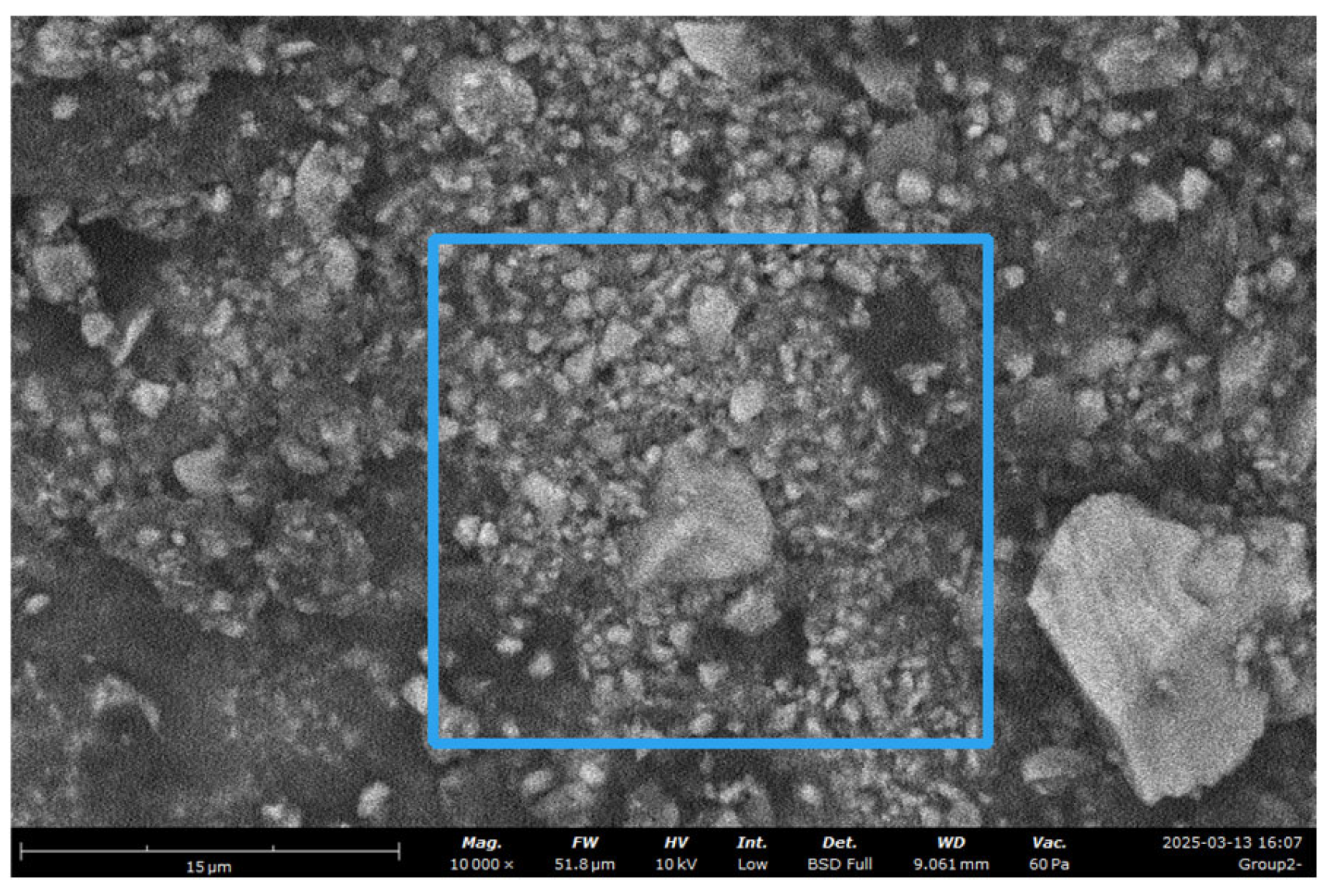

Figure 3.

group 2 image at 10000x.

Figure 3.

group 2 image at 10000x.

FW: 52 μm, Mode: 10 kV - Low, WD: 9.1 mm, Detector: BSD Full, Time: 3/13/25 4:07 PM

Table 2.

Analysis of group 2 at 10000x SEM magnification.

Table 2.

Analysis of group 2 at 10000x SEM magnification.

| |

Element

Number |

Element

Symbol |

Element

Name |

Atomic

Conc. |

Weight

Conc. |

| |

6 |

C |

Carbon |

33.511 |

22.200 |

| |

8 |

O |

Oxygen |

41.310 |

36.047 |

| |

13 |

Al |

Aluminum |

4.773 |

7.100 |

| |

14 |

Si |

Silicon |

14.780 |

22.900 |

| |

38 |

Sr |

Strontium |

1.614 |

7.800 |

| |

40 |

Zr |

Zirconium |

4.012 |

3.953 |

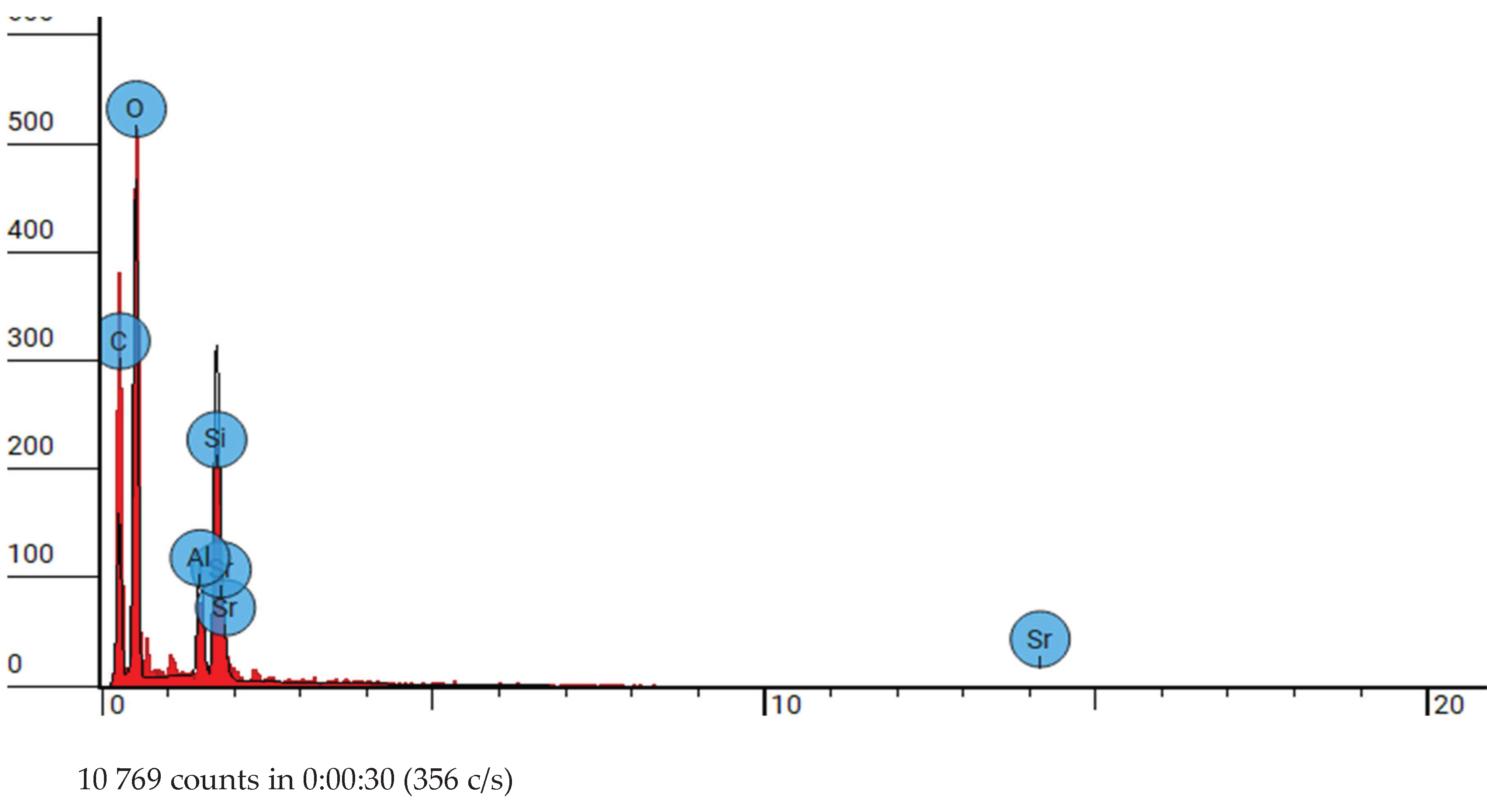

Figure 4.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 2 at 10000x.

Figure 4.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 2 at 10000x.

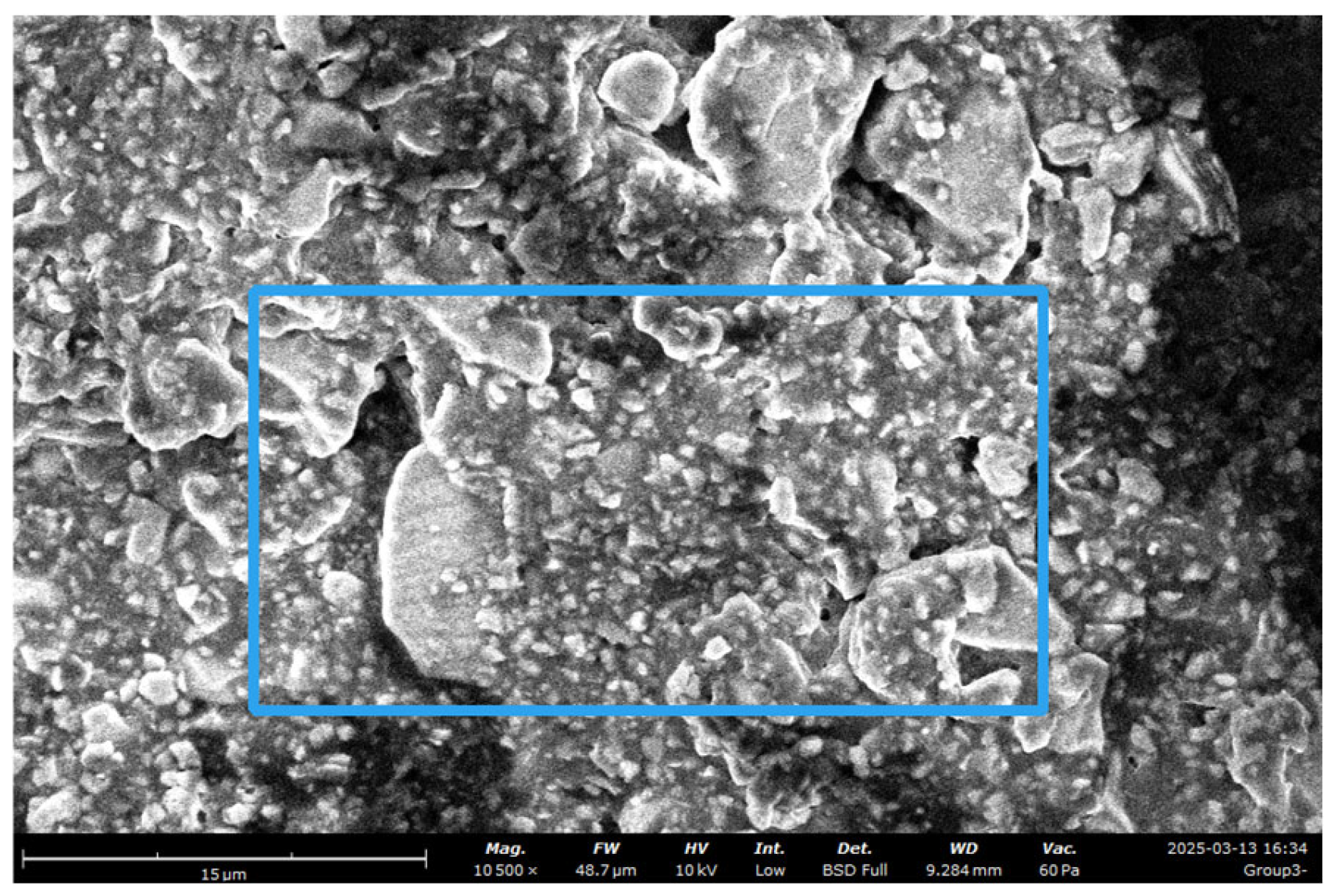

Group 3

Figure 5.

Group 3 image at 10000x.

Figure 5.

Group 3 image at 10000x.

Table 3.

Analysis of group 3 at 10000x SEM magnification.

Table 3.

Analysis of group 3 at 10000x SEM magnification.

| |

Element

Number |

Element

Symbol |

Element

Name |

Atomic

Conc. |

Weight

Conc. |

| |

6 |

C |

Carbon |

31.654 |

22.178 |

| |

8 |

O |

Oxygen |

54.263 |

50.649 |

| |

13 |

Al |

Aluminum |

3.810 |

5.994 |

| |

14 |

Si |

Silicon |

9.023 |

14.785 |

| |

38 |

Sr |

Strontium |

1.251 |

6.394 |

Figure 6.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 1 at 5000x.

Figure 6.

SEM-EDX analysis of group 1 at 5000x.

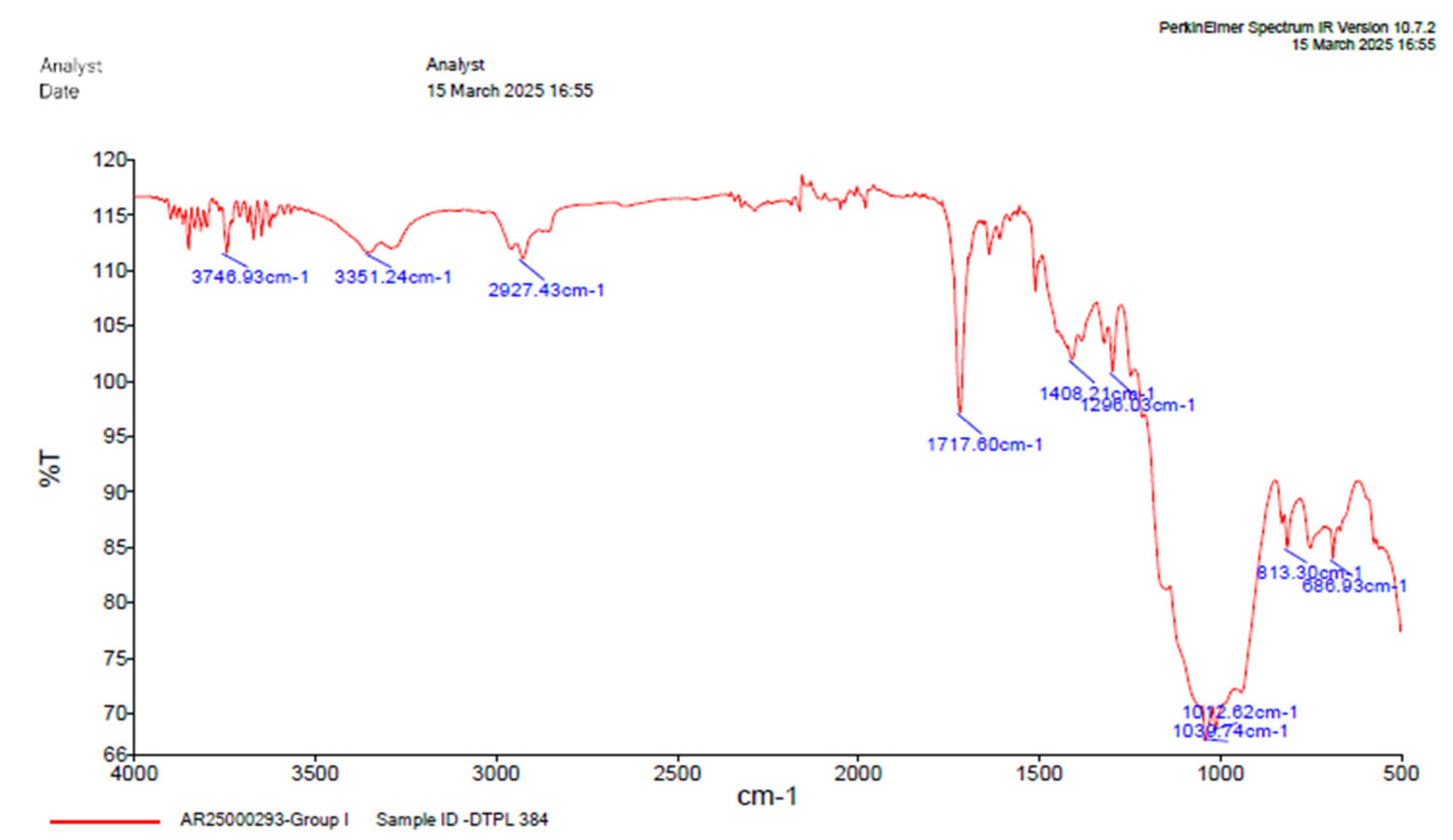

Figure 7.

FTIR analysis of group 1.

Figure 7.

FTIR analysis of group 1.

Table 4.

Table depicting absorption range.

Table 4.

Table depicting absorption range.

| GROUP 1 |

|---|

Absorption

(cm-1) |

Group |

Compound |

Comments |

| 3672.93 |

O-H stretching |

alcohol |

Medium bond, free |

| 3351.24 |

O-H stretching |

alcohol |

Strong, intermolecular bonded |

| 2927.43 |

C-H stretching |

alkane |

Medium |

| 1717.60 |

C=O stretching |

α, β, unsaturated ester |

Strong |

| 1637.69 |

C=C stretching |

Alkene |

Monosubstituted |

| 1509.77 |

N-O Stretching |

Nitro compound |

Strong |

| 1408.21 |

O-H bending |

Carboxylic acid |

Medium |

| 1296.03 |

C-O stretching |

Aromatic ecter |

Strong |

| 1039.74 |

S=O stretching |

Sulfoxide |

Strong |

| 1042.62 |

S=O stretching |

Sulfoxide |

Strong |

| 813.30 |

C=C stretching |

Alkene |

Medium, trisubstituted |

| 686.93 |

C-I stretching |

Halo compound |

Strong. |

| |

|

|

|

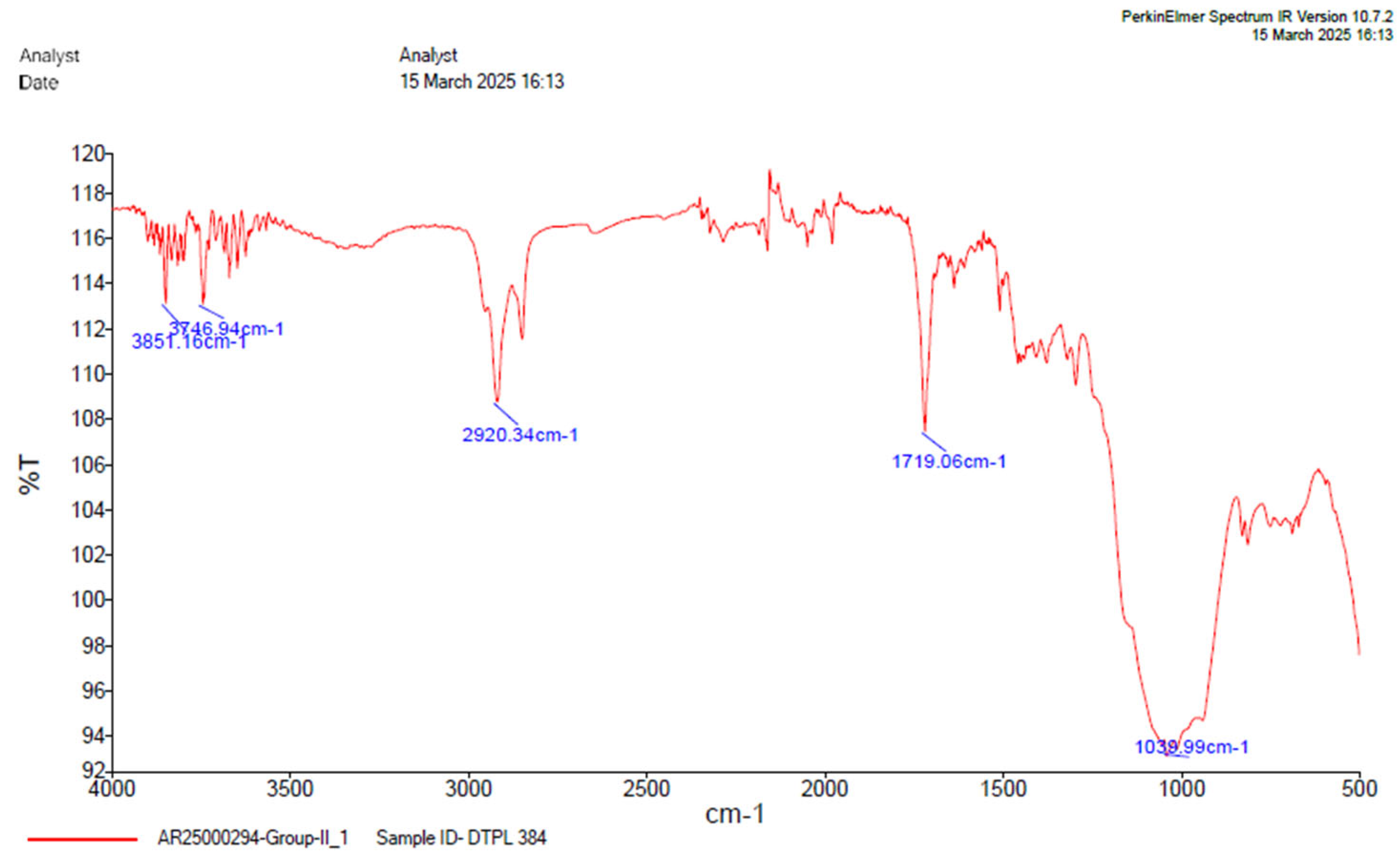

Group 2:

Figure 8.

FTIR analysis of group 2.

Figure 8.

FTIR analysis of group 2.

Table 5.

Table depicting absorption range.

Table 5.

Table depicting absorption range.

| GROUP 2 |

|---|

Absorption

(cm-1) |

Group |

Compound |

Comments |

| 3851.16 |

O-H stretching |

alcohol |

Medium bond, free |

| 3746.94 |

O-H stretching |

alcohol |

Medium bond, free |

| 2920.34 |

C-H stretching |

alkane |

Medium |

| 1719.06 |

C=O stretching |

α,β, unsaturated ester |

Strong |

| 1039.99 |

S=O stretching |

Sulfoxide |

Strong |

| |

|

|

|

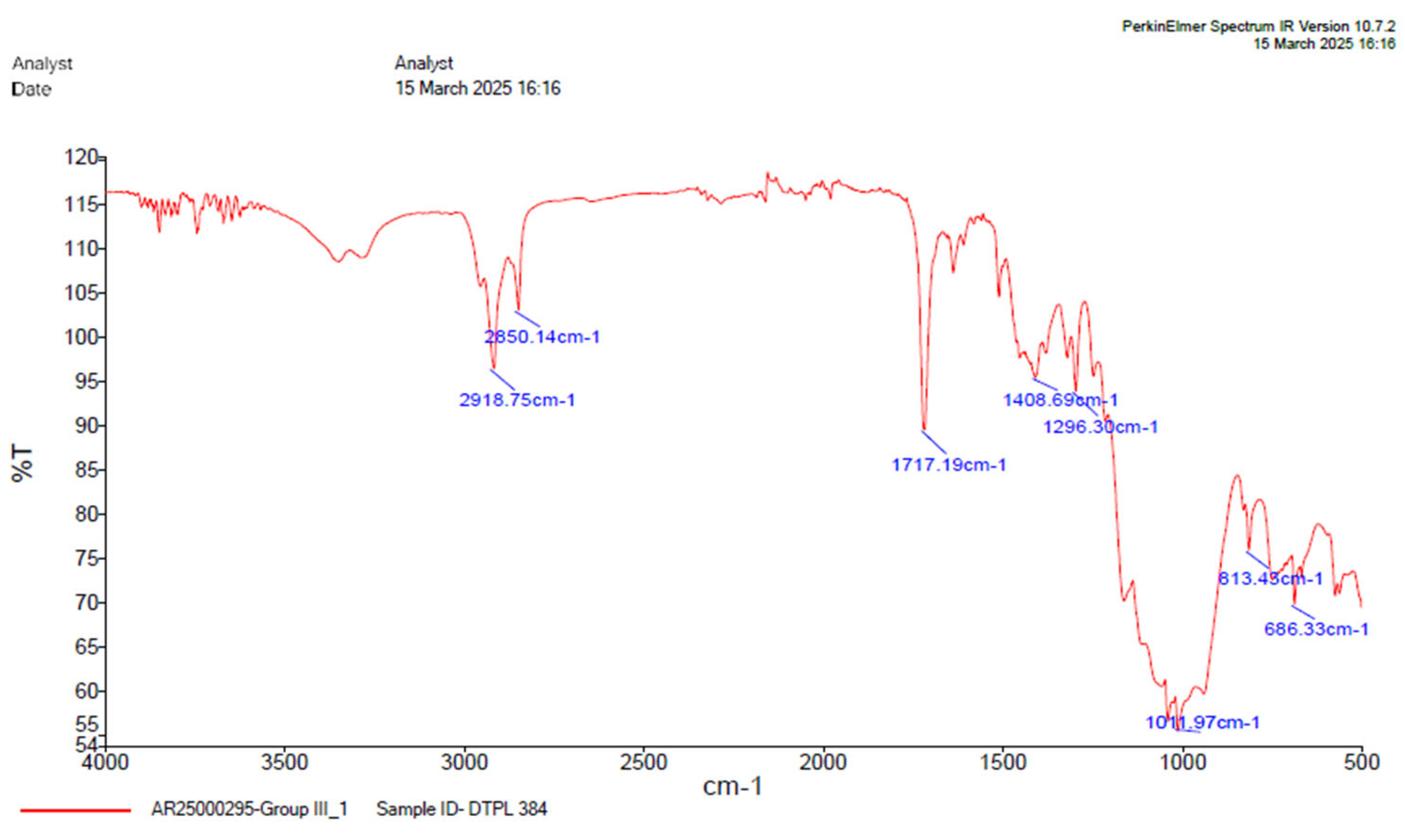

Group 3

Figure 9.

FTIR analysis of group 2.

Figure 9.

FTIR analysis of group 2.

Table 6.

Table depicting absorption range.

Table 6.

Table depicting absorption range.

| GROUP 3 |

|---|

Absorption

(cm-1) |

Group |

Compound |

Comments |

| 2918.75 |

C-H stretching |

alkane |

Medium |

| 1717.19 |

C=O stretching |

α,β, unsaturated ester |

Strong |

| 1408.69 |

O-H bending |

Carboxylic acid |

Medium |

| 1296.30 |

C-O stretching |

Aromatic ester |

Strong |

| 1011.97 |

S=O stretching |

Sulfoxide |

Strong |

| 813.43 |

C=C stretching |

Alkene |

Medium, trisubstituted |

| 686.32 |

C-I stretching |

Halo compound |

Strong. |

4. Discussion

SEM-EDX:

SEM images captured at varying magnifications provide a detailed depiction of the surface topography and microstructural features of dual-curable resin cement RelyX U200 and different groups of the same type, nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement and nanodiamond dual-cure resin cement, highlighting on its physical attributes and potential clinical applications. The SEM images of group 1-3 (DCRC and modified DCRC) depicted in Figures 1,3,5 unveil a heterogeneous surface topography characterized by the presence of diverse particle structures at magnifications of 1000x, 5000x, 10,000x, 50000x. Resin cement exhibits intricate morphological features, comprising a combination of splintered, heterogeneous and round shaped particles distributed in a size range of 1-10 µm. This amalgamation of particulate structures imparts DCRC with a unique surface texture, which could potentially influence its mechanical properties and bonding characteristics. [

36,

37].

Results from EDS spectroscopy analysis of the dual-curable resin cement RelyX U200 and different groups of similar type, nanozirconia modified dual-cured resin cement and nanodiamond dual-cured resin cement showed a variety in composition and the added fillers. To delineate the restorations to improve mechanical properties, nanozirconia was added. The disadvantage of adding large percentages of radiopaque fillers is the chemical degradation caused by water immersion. It is important to balance the mechanical properties of DCRC with the incorporation of filler particles without affecting its physical properties.

Fillers were of varying sizes and SEM findings present diverse filler shapes. The modified cement contained range of spherical shape of fillers to clusters, loosely agglomerated. These particles increased the combined mechanical strength with high biocompatibility of modified DCRC[

33,

37,

43].

Elemental analysis conducted via SEM-EDS reveals the elemental composition of DCRC, confirming the presence of silica, oxygen, aluminium, Phosphorus, Strontium, zirconium and carbon as evidenced by the elemental peaks observed in the backscattered electron images

Figure 2,

Figure 4,

Figure 6. These elemental constituents play pivotal roles in dictating the physico-mechanical properties and clinical performance of DCRC, thereby underscoring their significance in dental material science. These congruent observations validate the robustness and reliability of SEM analysis as a tool for characterizing dental resin cements and elucidating their structural attributes. Moreover, the identification of splintered and round particles within dual-curable cement RelyX U200 and different groups of its type, nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement and nanodiamond dual-cure resin cement corroborates previous research findings, further consolidating our understanding of its microstructural architecture and surface characteristics [

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6]. These consistent observations underscore the reproducibility and inherent characteristics of dual-cure resin cement RelyX U200 and different groups of its kind, nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement and nanodiamond dual-cure resin cement, positioning it as a promising candidate for various clinical applications in restorative dentistry.[

30,

33,

43]

FTIR:

Resin cement used in restorative dentistry must be of good mechanical properties and should strongly bind the tooth and the restoration. It is desirable to know the composition, chemical structures and bond strength between different components of the resin cement, as they are placed close to the vital tissues. This is a vibrational technique used to understand the chemical ingredient and structure. Here photons move from lower energy state to higher state by absorbing energy in infra-red region resulting in vibrating movement of molecular bond [

38,

43].

The FTIR analysis conducted in this study offers a comprehensive understanding of dual-curing resin cement RelyX U200 and different groups of its type; nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement and nanodiamond dual-cure resin cement, generating ideas on their molecular structure and bond strength. Characteristic absorption bands corresponding to sulfoxide, alkane and hydroxyl groups were observed in the FTIR spectra of RelyX U200 and different groups of dual cure resin cement, nanozirconia modified dual curable resin cement and nanodiamond double curing resin cement, confirming its composition.[

36]

Comparison of the FTIR spectra between dual-cure resin cement RelyX U200 and nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement counterpart revealed notable shifts in absorption bands but under same band values indicating interactions between the DCRC components and nanozirconia particles. Particularly, the shifting of the OH stretching vibration from 3672.93cm-1 to 3851.16 cm-1 in the modified formulations suggests alterations in the hydrogen bonding environment, potentially enhancing material properties, [

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9]. The presence of free functional groups for bonding in certain modified groups highlights the versatility and potential applications of nanozirconia-modified DCRC in dental procedures.[

35,

36]

Comparison of the FTIR spectra between dual cure resin cement RelyX U200 and nanodiamond modified dual-cure resin cement counterpart revealed notable shifts in absorption bands indicating interactions between the DCRC components and nanodiamond particles with medium bonding. Particularly, the shifting of the OH stretching vibration from 3672.93cm-1 to C-H stretching vibration 2918.75 cm-1 in the modified formulations suggests alterations in the hydrogen bonding environment, potentially enhancing materials properties. The presence of free functional groups for bonding in certain modified groups highlights the versatility and potential applications of nanodiamond-modified DCRC in dental procedures [

35,

43].

Similarly, the absorption bands associated with C=C and S=O stretching vibrations in the 2000–1650 cm-1 range provide insights into the presence of aromatic ring structures within the DCRC. These functional groups contribute to the DCRC chemical reactivity and mechanical properties, influencing their suitability for dental applications. Moreover, the assignment of absorption peaks to a broader peak with an idealized formula provides valuable insights into the overall composition of the dual-cure resin cement RelyX U200 and different groups of dual-cure resin cement, nanozirconia modified dual-cure resin cement, nanodiamond dual cure resin cement.[

34,

43]

5. Conclusions

SEM-EDX findings presents varying shapes of nanoparticles distributed evenly in modified resin cements and in FTIR, molecules were seen distributed evenly with varying bond strength among molecules ranging from medium to strong.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; methodology, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; software, Saleem D. Makandar.; validation, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; formal analysis, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; investigation, Saleem D. Makandar.; resources, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; data curation, Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; writing—original draft preparation, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; writing—review and editing, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; visualization, Saleem D. Makandar. and Aaqil Arshad Hulikatti.; supervision, Saleem D. Makandar.; project administration, Saleem D. Makandar.; funding acquisition, Saleem D. Makandar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Universiti Sains Malaysia, Research University Individual (RUI) Grant Scheme (Grant Number: R502-KR-ARU001-0000001139-K134).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Universiti Sains Malaysia, Research University Individual (RUI) Grant Scheme (Grant Number: R502-KR-ARU001-0000001139-K134).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BisGMA |

bisphenol-A-ethoxy dimethacrylate |

| BisEMA |

bisphenol-A-ethoxy dimethacrylate |

| UDMA |

urethane dimethacrylate |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscope |

| EDS |

Energy-Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| DCRC |

Dual cure resin cement |

References

- Sümer, E.; Değer, Y. Contemporary Permanent Luting Agents Used in Dentistry: A Literature Review. Int Dent Res 2011, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletin, A.; Knežević, M.J.; Koprivica, D.Đ.; Veljović, T.; Puškar, T.; Milekić, B.; Ristić, I. Dental Resin-Based Luting Materials—Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeSage, B.P. Aesthetic Anterior Composite Restorations: A Guide to Direct Placement. Dent Clin North Am 2007, 51, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adwani, S.; Elsubeihi, E.; Zebari, A.; Aljanahi, M.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Elbishari, H. Effect of Different Silane Coupling Agents on the Bond Strength between Hydrogen Peroxide-Etched Epoxy-Based- Fiber-Reinforced Post and Composite Resin Core. Dent J 2023, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiranukoon, P.; Klaisiri, A.; Sriamporn, T.; Swasdison, S.; Thamrongananskul, N. Does Silane Application Affect Bond Strength Between Self-Adhesive Resin Cements and Feldspathic Porcelain? J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichristou, C.; Papachristou, E.; Vereroudakis, E.; Chatzinikolaidou, M.; About, I.; Koidis, P.; Bakopoulou, A. Biocompatibility Assessment of Resin-Based Cements on Vascularized Dentin/Pulp Tissue-Engineered Analogues. Dent Mater 2021, 37, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.M.; Cattani-Lorente, M.A.; Dupuis, V. Compomers: Between Glass-Ionomer Cements and Composites. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentritt, M.; Behr, M.; Lang, R.; Handel, G. Influence of Cement Type on the Marginal Adaptation of All-Ceramic MOD Inlays. Dent Mater 2004, 20, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, N.; Tam, L.E.; McComb, D. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Contemporary Dental Luting Agents. J Prosthet Dent 2003, 89, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.; Lott, J. A Clinically Focused Discussion of Luting Materials. Aust Dent J 2011, 56, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Sorption and Solubility Characteristics of Self-Adhesive Resin Cements. Dent Mater 2012, 28, e187–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, A.; Lauer, H.-C.; Sorensen, J.A. In Vitro Shear Bond Strength of Cementing Agents to Fixed Prosthodontic Restorative Materials. J Prosthet Dent 2004, 92, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heboyan, A.; Vardanyan, A.; Karobari, M.I.; Marya, A.; Avagyan, T.; Tebyaniyan, H.; Mustafa, M.; Rokaya, D.; Avetisyan, A. Dental Luting Cements: An Updated Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, S.A.; McCabe, J.F.; Walls, A.W.G. Polymerisation Shrinkage of Luting Agents for Crown and Bridge Cementation. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 2008, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spinell, T.; Schedle, A.; Watts, D.C. Polymerization Shrinkage Kinetics of Dimethacrylate Resin-Cements. Dent Mater 2009, 25, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libman, W.J.; Nicholls, J.I. Load Fatigue of Teeth Restored with Cast Posts and Cores and Complete Crowns. Int J Prosthodont 1995, 8, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hansson, O. Clinical Results with Resin-Bonded Prostheses and an Adhesive Cement. Quintessence Int 1994, 25, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 8183.

- Creugers, N.H.J.; Van ’T Hof, M.A. An Analysis of Clinical Studies on Resin-Bonded Bridges. J Dent Res 1991, 70, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, J.L.; Mitchem, J.C.; Condon, J.R.; Todd, R. Wear and Marginal Breakdown of Composites with Various Degrees of Cure. J Dent Res 1997, 76, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turssi, C.; Ferracane, J.; Vogel, K. Filler Features and Their Effects on Wear and Degree of Conversion of Particulate Dental Resin Composites. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4932–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihei, T.; Dabanoglu, A.; Teranaka, T.; Kurata, S.; Ohashi, K.; Kondo, Y.; Yoshino, N.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.-H. Three-Body-Wear Resistance of the Experimental Composites Containing Filler Treated with Hydrophobic Silane Coupling Agents. Dent Mater 2008, 24, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressano, D.; Salvador, M.V.; Oliveira, M.T.; Marchi, G.M.; Fronza, B.M.; Hadis, M.; Palin, W.M.; Lima, A.F. Chemistry of Novel and Contemporary Resin-Based Dental Adhesives. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2020, 110, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Yang, Z.H.; Fang, C.; Han, N.X.; Zhu, G.M.; Tang, J.N.; Xing, F. Evaluation of the Mechanical Performance Recovery of Self-Healing Cementitious Materials – Its Methods and Future Development: A Review. Constr Build Mater 2019, 212, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zhang, N.; Santos, R.M. Mineral Characterization Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): A Review of the Fundamentals, Advancements, and Research Directions. Appl Sci 2023, 13, 12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhong, F.; Zhang, F.; Ying, C.; Geng, G. Application of Scanning Electron Microscopy in Metal Material Detection. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021, 2002, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, F.; Meng, X. Surface Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Conventional and Self-Adhesive Resin Cements after Aqueous Aging. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikin, D.; Kohlhaas, K.; Dommett, G.; Stankovich, S.; Ruoff, R. Scanning Electron Microscopy Methods for Analysis of Polymer Nanocomposites. Microsc Microanal 2006, 12, 674–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihei, T.; Dabanoglu, A.; Teranaka, T.; Kurata, S.; Ohashi, K.; Kondo, Y.; Yoshino, N.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.-H. Three-Body-Wear Resistance of the Experimental Composites Containing Filler Treated with Hydrophobic Silane Coupling Agents. Dent Mater 2008, 24, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, B. Optical Microscopy and Electron Microscopy for the Morphological Evaluation of Tendons: A Mini Review. Orthop Surg 2020, 12, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradella, T.C.; Bottino, M.A. Scanning Electron Microscopy in Modern Dentistry Research. Braz Dent J 2012, 15, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghiri, M.A.; Asgar, K.; Lotfi, M.; Karamifar, K.; Saghiri, A.M.; Neelakantan, P.; Gutmann, J.L.; Sheibaninia, A. Back-Scattered and Secondary Electron Images of Scanning Electron Microscopy in Dentistry: A New Method for Surface Analysis. Acta Odontol Scand 2012, 70, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scimeca, M.; Bischetti, S.; Lamsira, H.K.; Bonfiglio, R.; Bonanno, E. Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) Microanalysis: A Powerful Tool in Biomedical Research and Diagnosis. Eur J Histochem 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelson, D.A. Energy Dispersive X-Ray Microanalysis. Methods Mol Biol 1998, 108, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Khan, S.B.; Khan, L.U.; Farooq, A.; Akhtar, K.; Asiri, A.M. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Application in Functional Groups and Nanomaterials Characterization. Handbook of Materials Characterization, 9295. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kelani, M.; Buthelezi, N. Advancements in Medical Research: Exploring Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy for Tissue, Cell, and Hair Sample Analysis. Skin Res and Technol 2024, 30, e13733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kemary, B.M.; El-Borady, O.M.; Abdel Gaber, S.A.; Beltagy, T.M. Role of nano-zirconia in the Mechanical Properties Improvement of Resin Cement Used for Tooth Fragment Reattachment. Polym Compos 2021, 42, 3307–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beketova, A.; Tzanakakis, E.-G.C.; Vouvoudi, E.; Anastasiadis, K.; Rigos, A.E.; Pandoleon, P.; Bikiaris, D.; Tzoutzas, I.G.; Kontonasaki, E. Zirconia Nanoparticles as Reinforcing Agents for Contemporary Dental Luting Cements: Physicochemical Properties and Shear Bond Strength to Monolithic Zirconia. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Hussain, A.; Rao, J.; Singh, K.; Avinashi, S.K.; Gautam, C. Structural, Mechanical and Biological Properties of PMMA-ZrO2 Nanocomposites for Denture Applications. Mater Chem Phys 2023, 295, 127089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriche, R.; Artigas-Arnaudas, J.; Chetwani, B.; Sánchez, M.; Campo, M.; Prolongo, M.G.; Rams, J.; Prolongo, S.G.; Ureña, A. Microhardness and Wear Behavior of Nanodiamond-reinforced Nanocomposites for Dental Applications. Polym Compos 2025, 46, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosthetic dental science Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia; Emam, A. -N.M. Influence of Nanodiamond Incorporation on The Impact Strength of Repaired Denture Base Acrylic Resin: An in Vitro Study. Ro J Stomatol. 2024, 70, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, S.M.; Gad, M.M.; Ellakany, P.; Al Ghamdi, M.A.; Khan, S.Q.; Akhtar, S.; Ali, M.S.; Al-Harbi, F.A. Flexural Properties, Impact Strength, and Hardness of Nanodiamond-Modified PMMA Denture Base Resin. Int J Biomater 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.D.C.A.; Limirio, P.H.J.O.; Novais, V.R.; Dechichi, P. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Application Chemical Characterization of Enamel, Dentin and Bone. Appl Spectrosc Rev 2018, 53, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batul, R.; Makandar, S.D.; Nawi, M.A.B.A.; Basheer, S.N.; Albar, N.H.; Assiry, A.A.; Luke, A.M.; Karobari, M.I. Comparative Evaluation of Microhardness,Water Sorption and Solubility of Biodentin and Nano-Zirconia-Modified Biodentin and FTIR Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).