Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

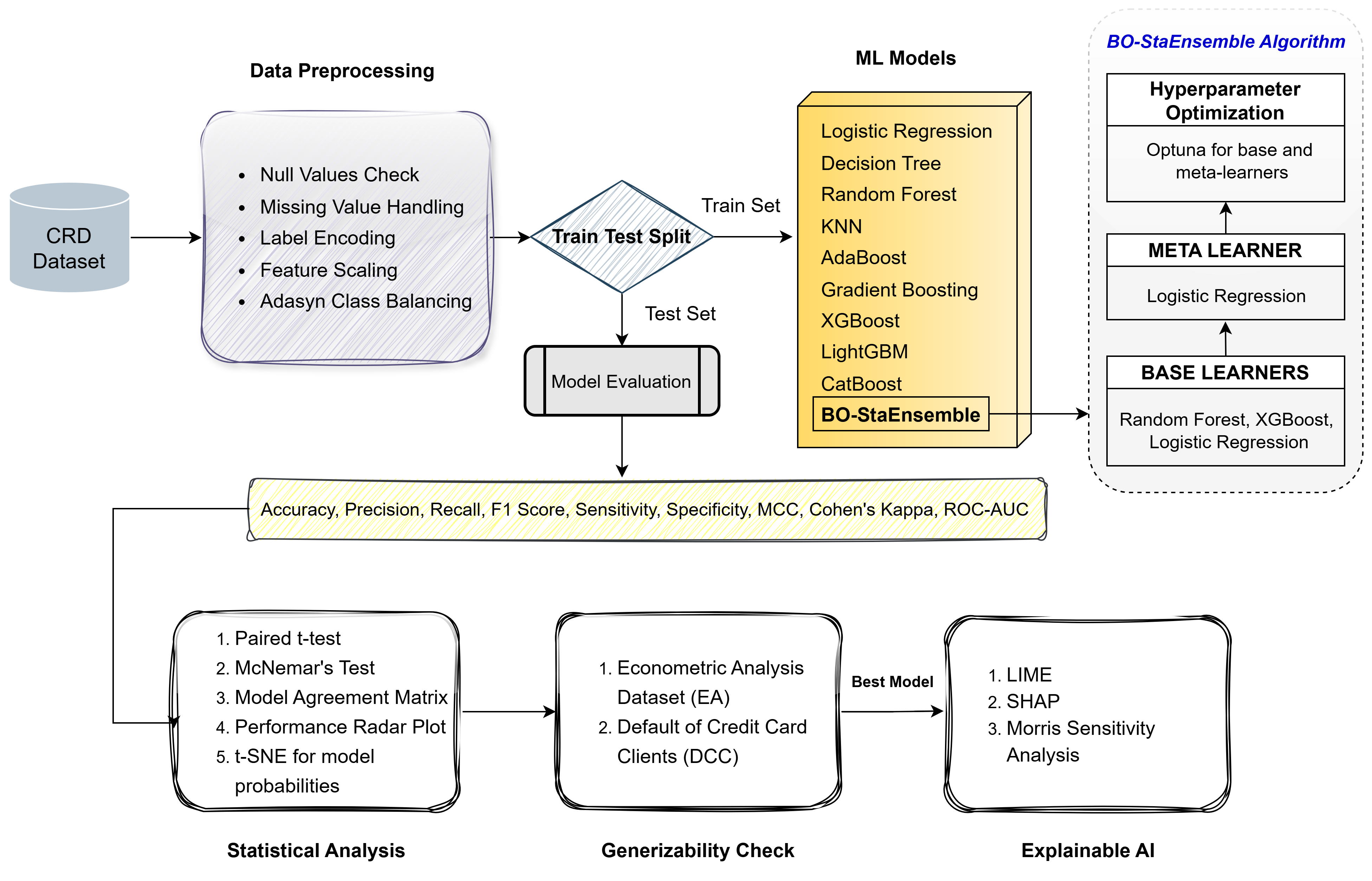

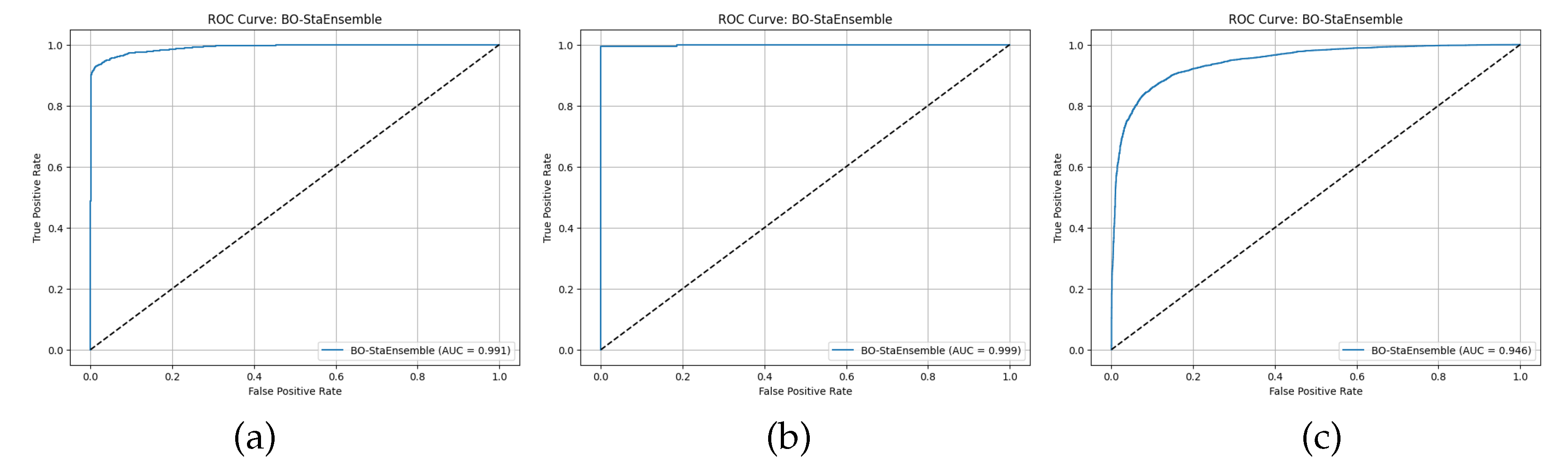

- We introduce a novel stacking framework in which both the base classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost, Logistic Regression) and the meta-learner are jointly hyperparameter-tuned via Optuna, yielding AUCs of 0.998 (CRD), 0.999 (EA), and 0.974 (DCC) and consistently outperforming all individual and untuned ensemble baselines.

- Unlike prior work confined to a single dataset, our BO-StaEnsemble is rigorously evaluated on three famous credit-credit scoring datasets - CRD (Credit Risk Dataset), EA (Econometric Analysis) and DCC (Default of Credit card Clients), demonstrating robustness and generalizability across varied economic and demographic contexts.

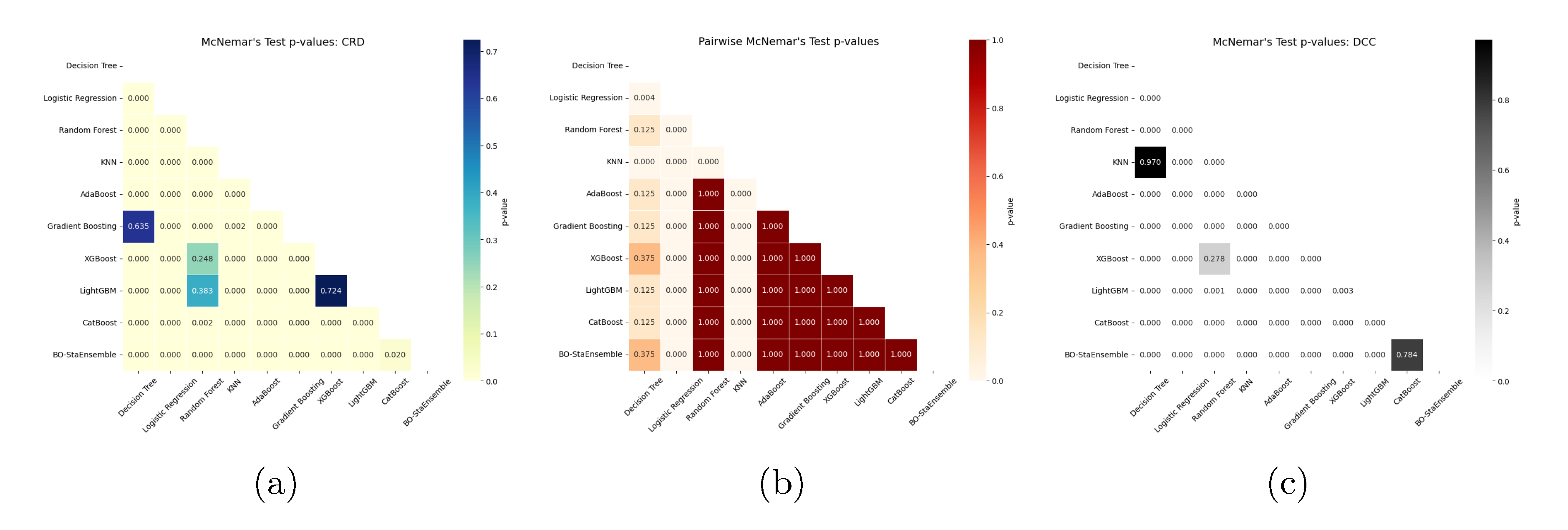

- We embed paired t-tests and McNemar’s tests directly into the evaluation pipeline to assess whether observed performance differences are statistically significant, ensuring that reported gains reflect true model improvements rather than random variation.

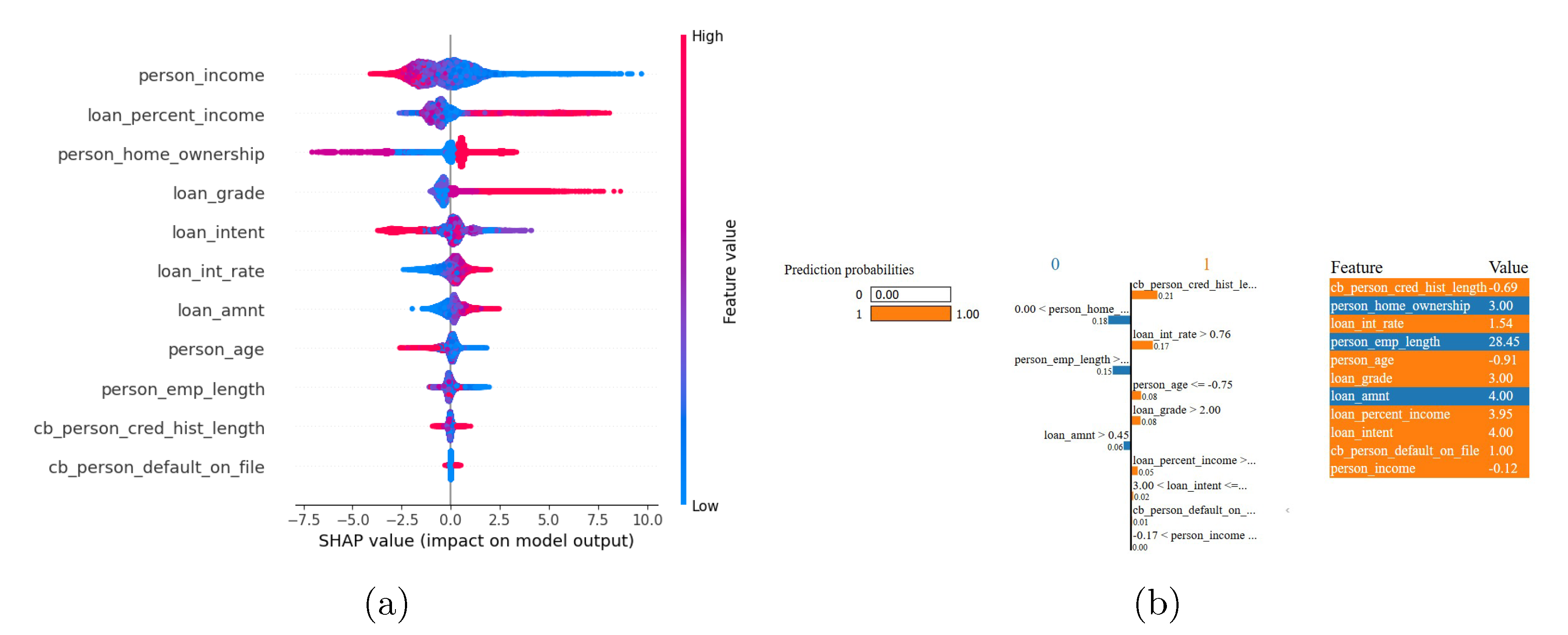

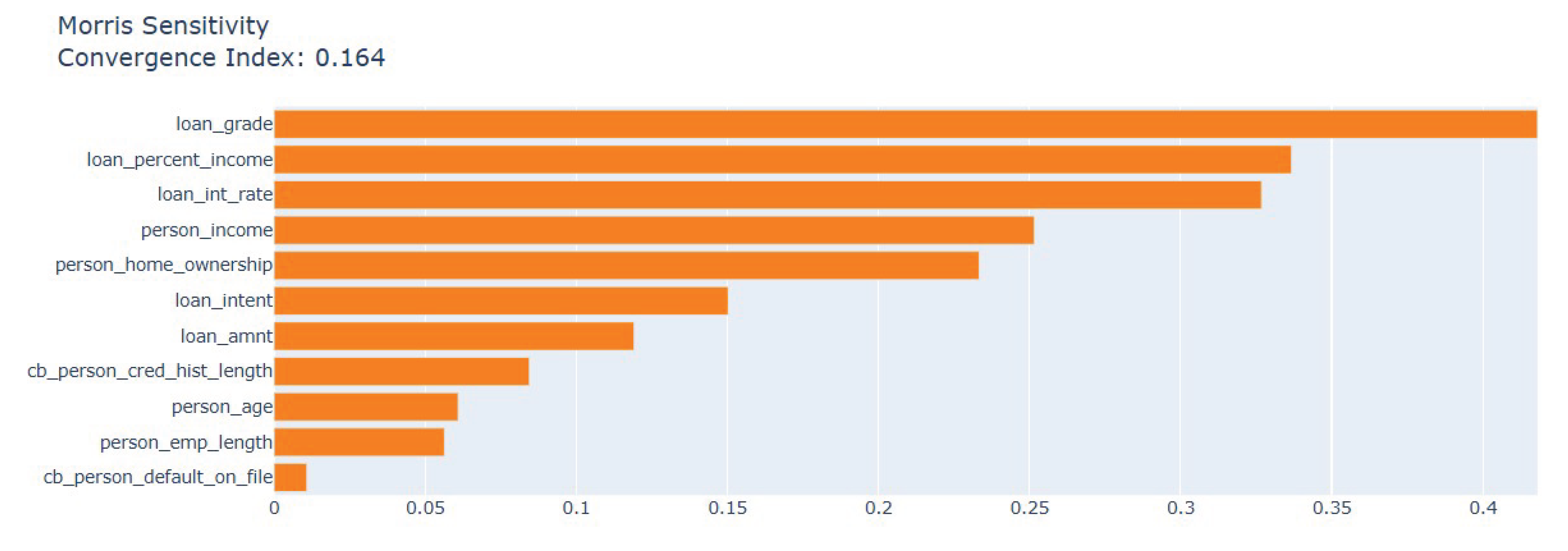

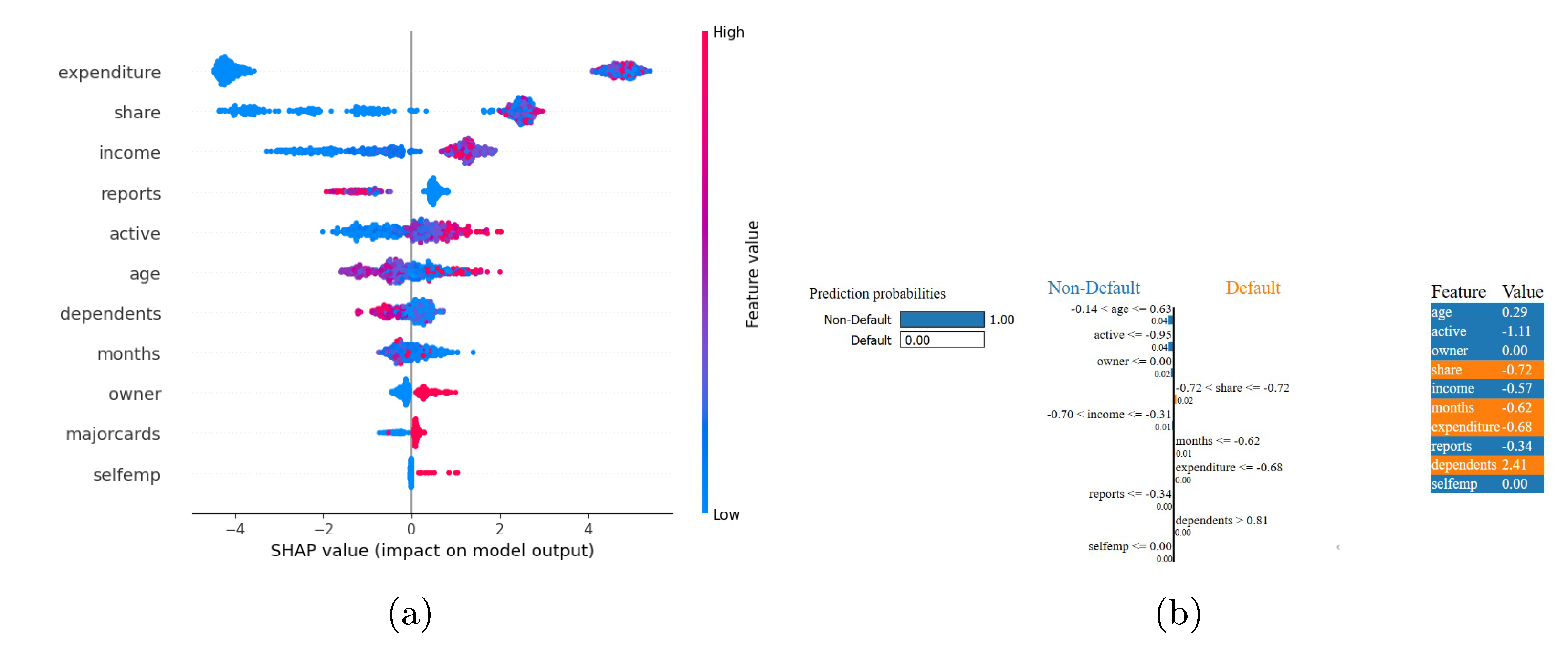

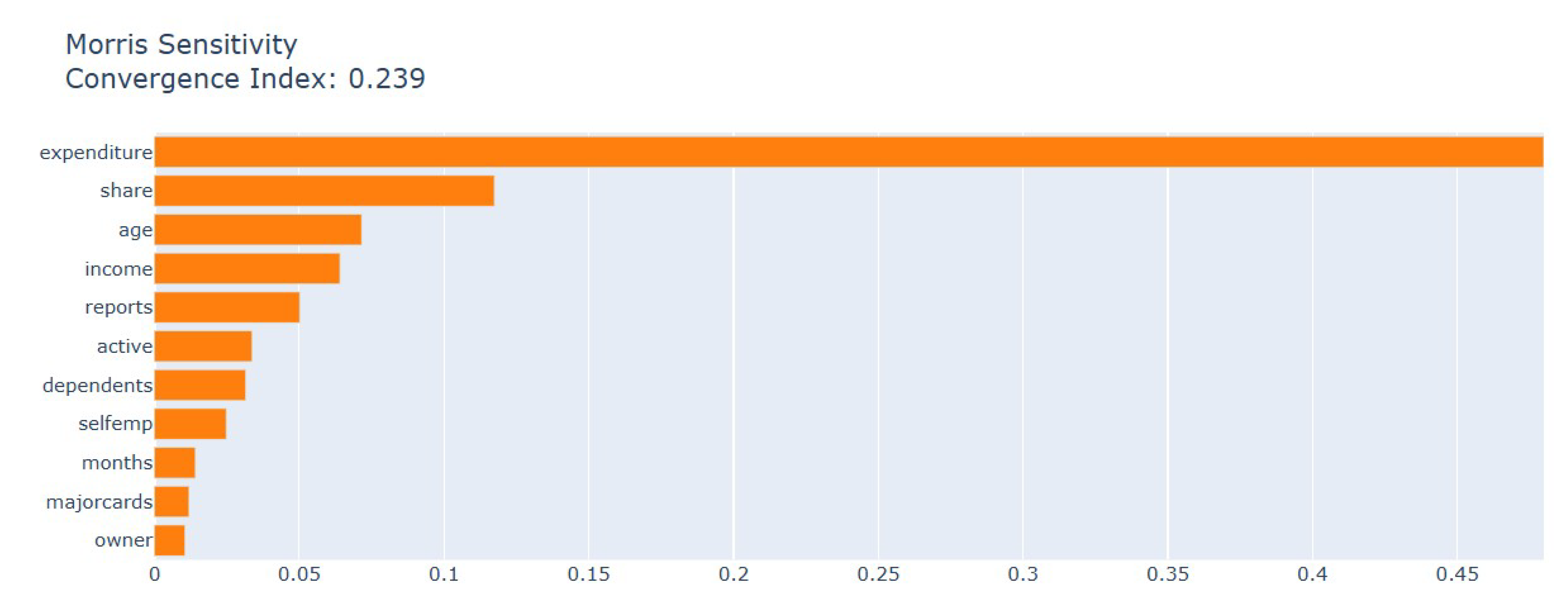

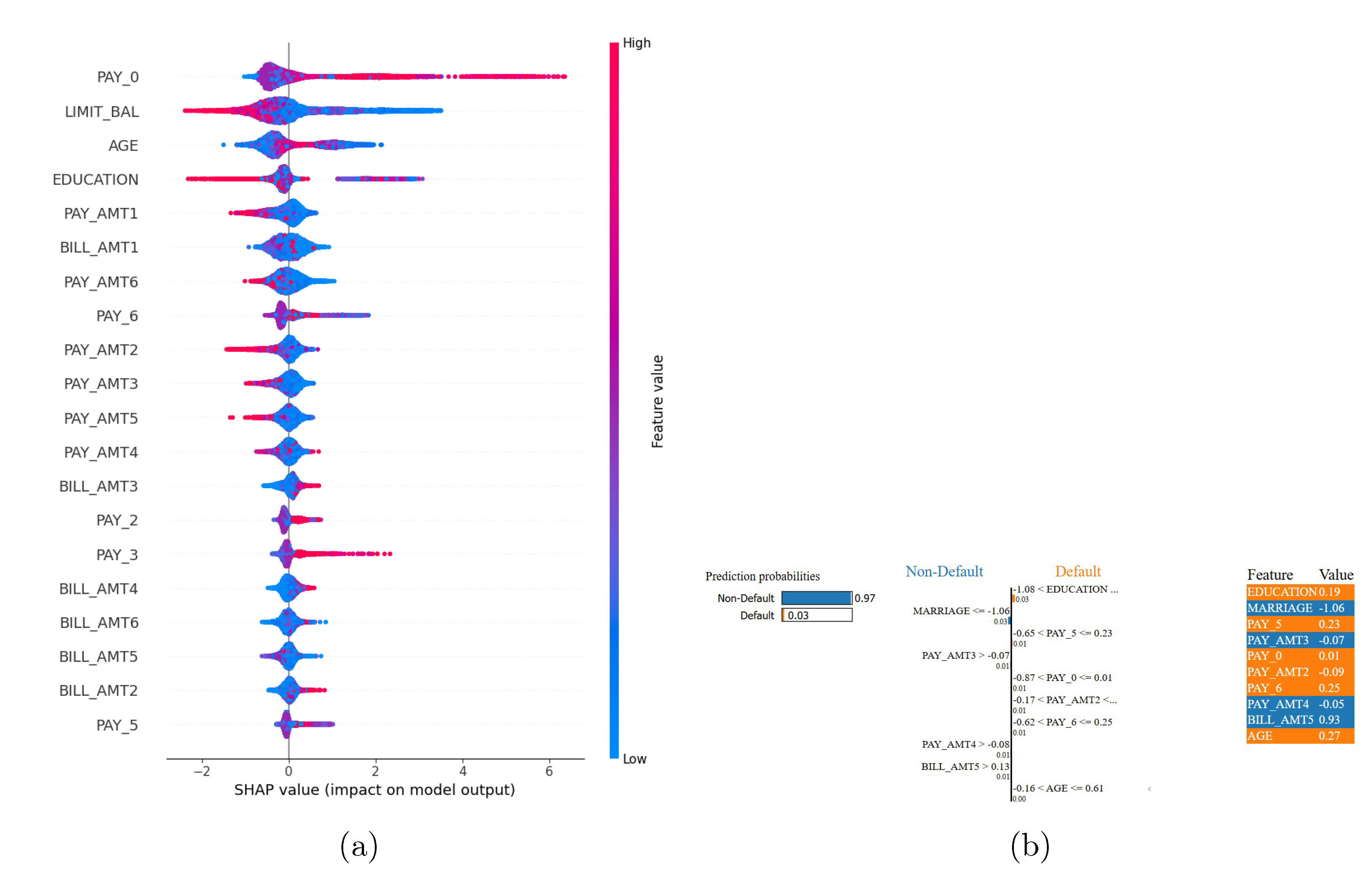

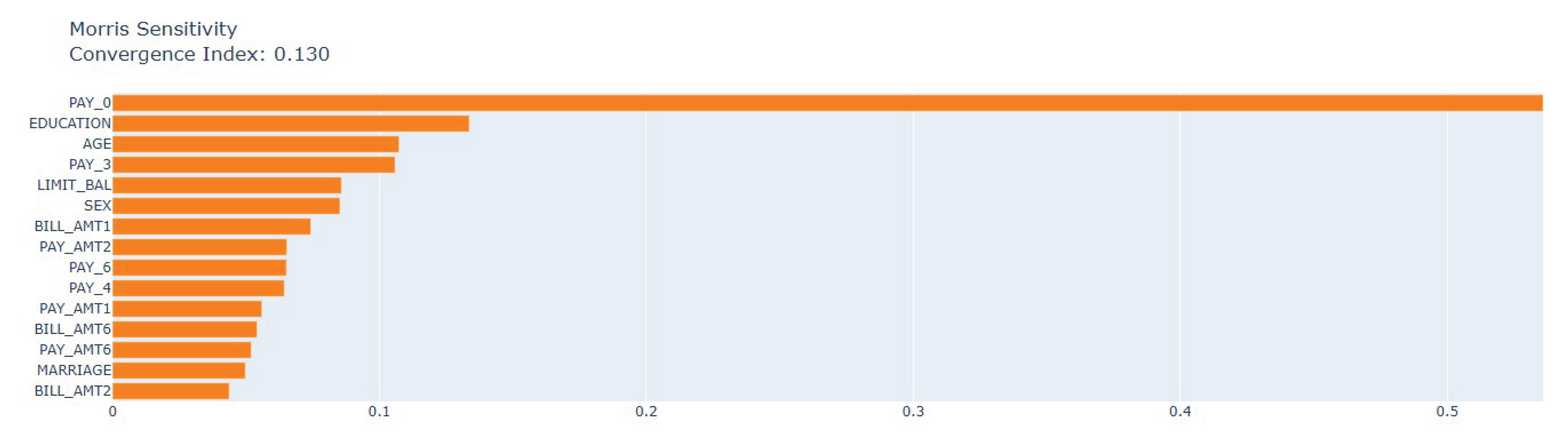

- By combining model-agnostic techniques—LIME for local decision explanations, SHAP for global and per-instance importance, and Morris Sensitivity Analysis for feature interaction effects—we deliver fine-grained, transparent insights into the drivers of creditworthiness decisions.

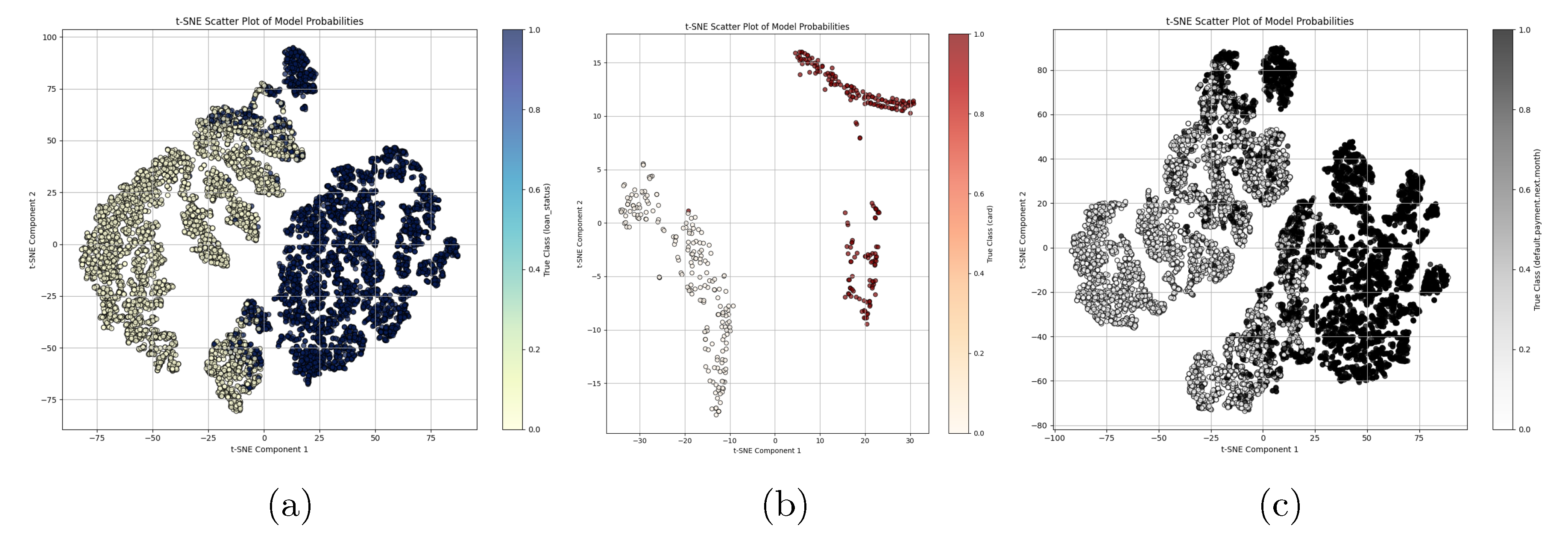

- We used t-SNE to project high-dimensional model outputs into a two-dimensional space, clearly separating default vs. non-default clusters and illustrating how the ensemble synthesizes base-learner predictions into coherent, interpretable decision boundaries.

2. Related Works

2.1. Comparison of Classification Approaches for Credit Scoring

2.2. Feature Selection and Explainability

3. Methodology

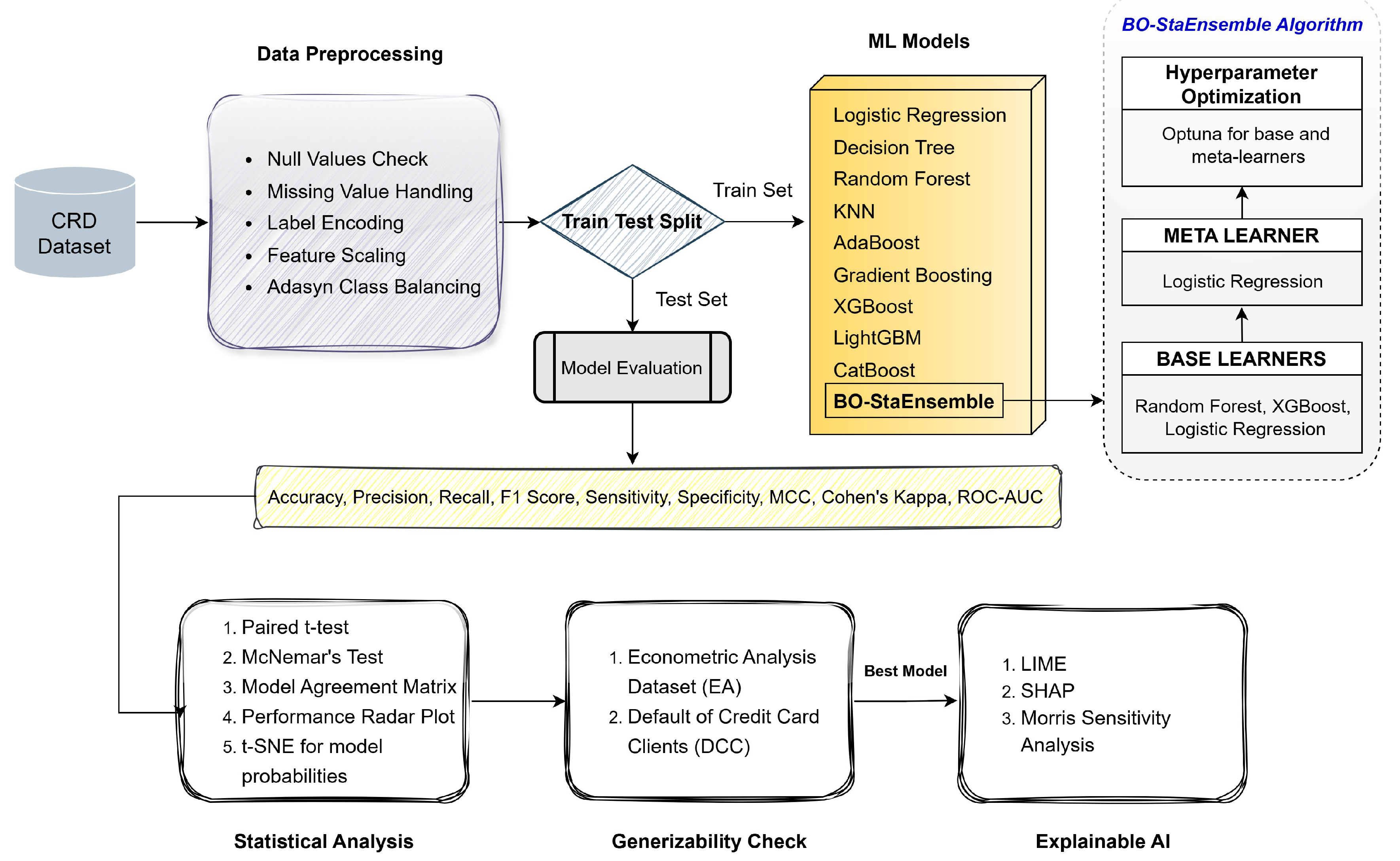

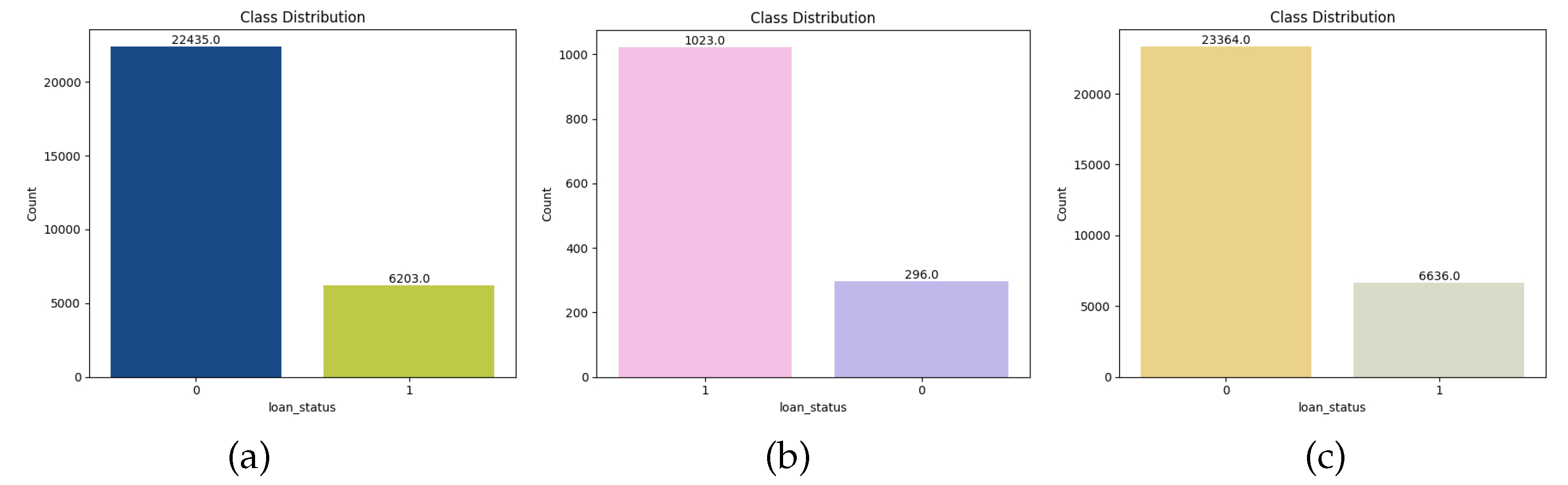

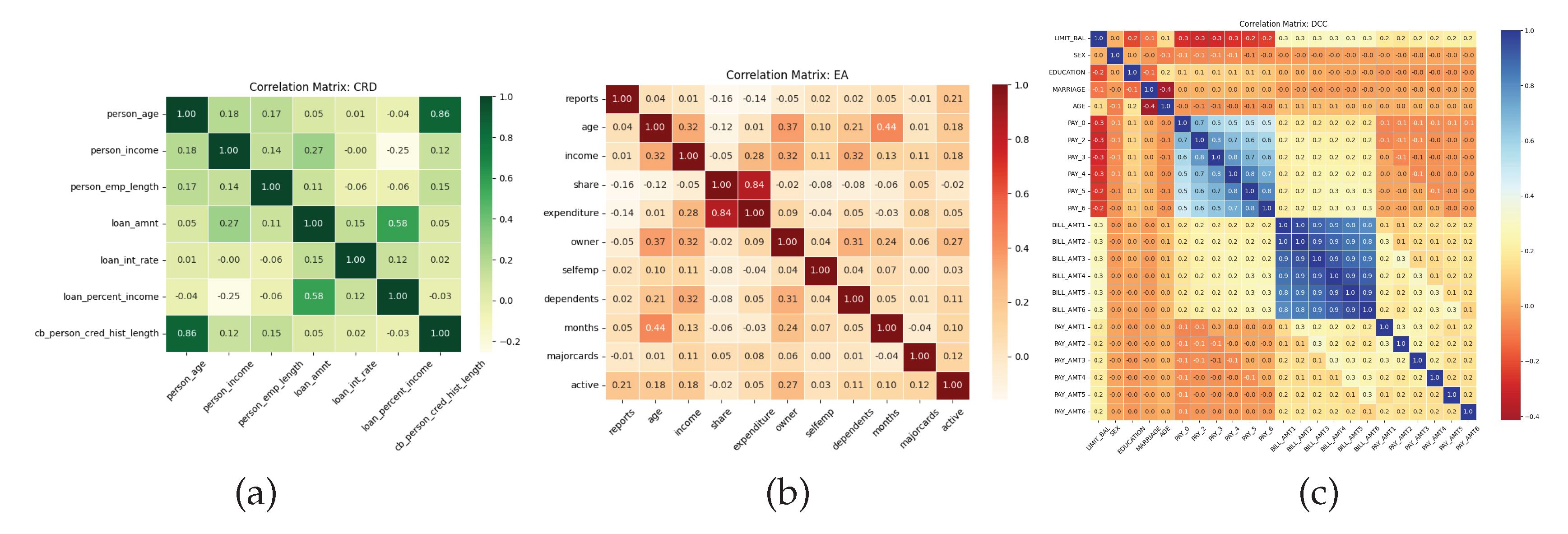

3.1. Dataset Details

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. Models Applied and Evaluation Criteria

3.4. Proposed BO-StaEnsemble Approach

| Algorithm 1:Pseudo code of proposed BO-StaEnsemble approach |

|

3.5. Statistical Analysis

3.6. Explainable AI

4. Results & Discussion

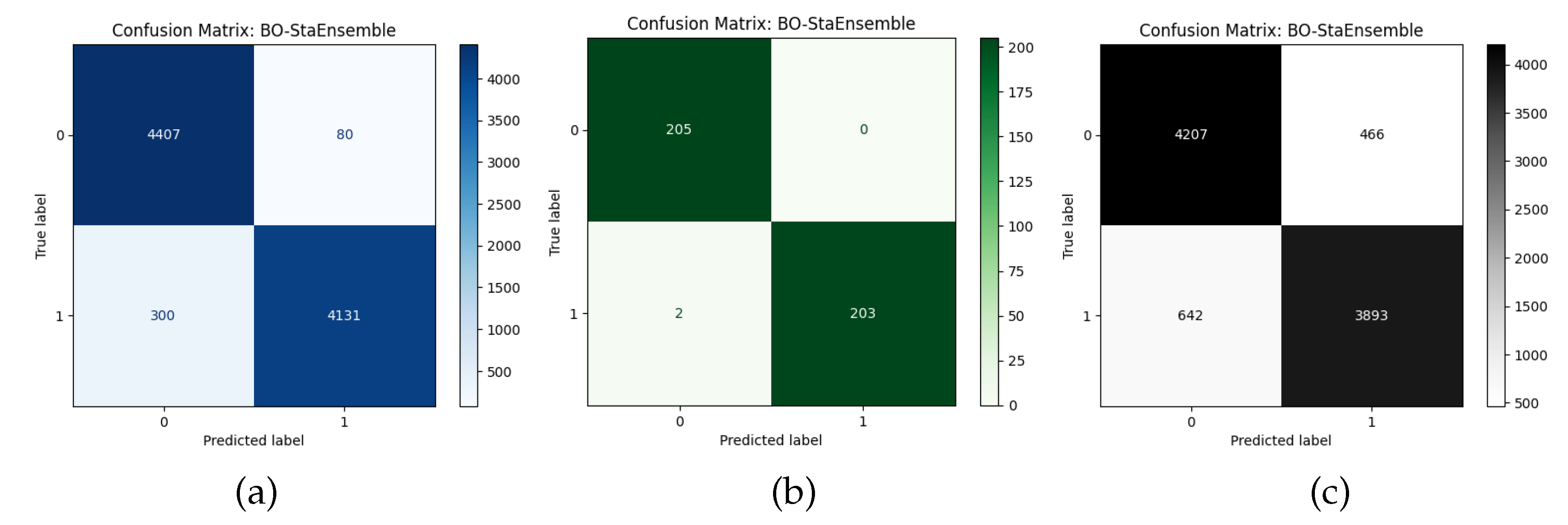

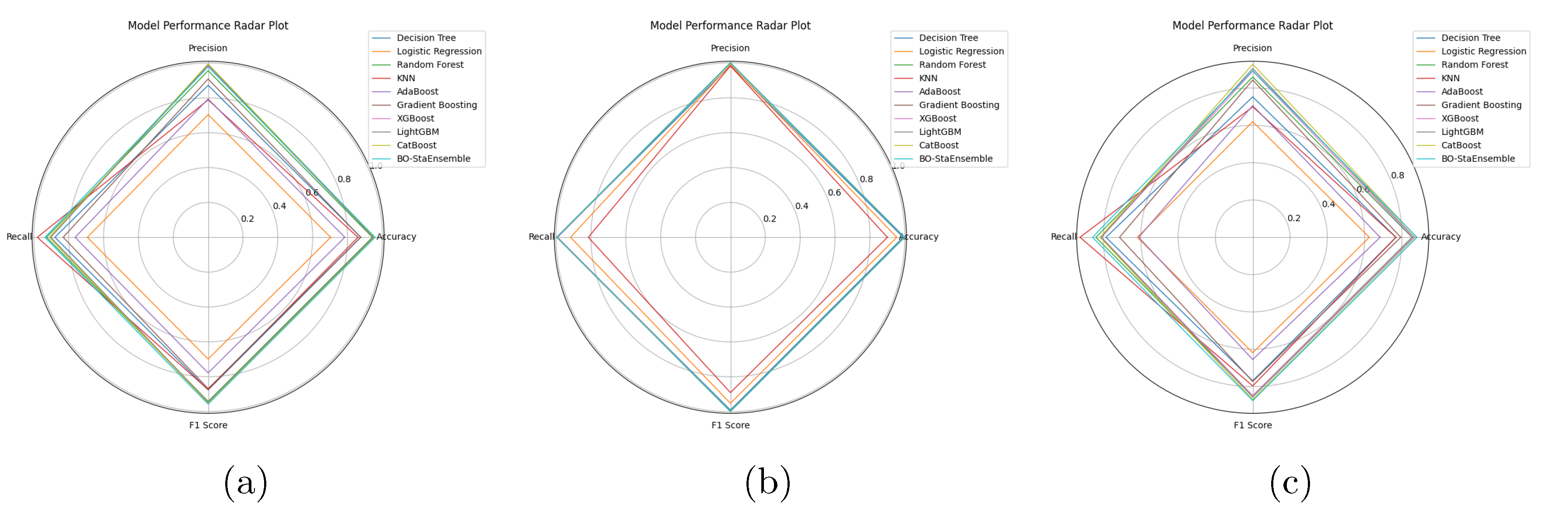

4.1. Robustness of BO-StaEnsemble Approach

4.2. Statistical Analysis with t-Test, McNemar’s Test and t-SNE

4.3. Transperancy of the Model

4.3.1. Credit Risk Dataset (CRD)

4.3.2. Econometric Analysis (EA) Dataset

4.3.3. Default of Credit Card Clients (DCC) Dataset

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. R. Islam. Credit default mining using combined machine learning and heuristic approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.01176, July 2, 2018. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.01176.

- C. Fung. Dancing in the dark: Private multi-party machine learning in an untrusted setting. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.09712, 2018. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.09712.

- C. Leong, B. C. Leong, B. Tan, X. Xiao, F. T. C. Tan, and Y. Sun. Nurturing a fintech ecosystem: The case of a youth microloan startup in China. International Journal of Information Management, 2017; 37, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. H. Fares, I. O. H. Fares, I. Butt, and S. H. M. Lee. Utilization of artificial intelligence in the banking sector: a systematic literature review. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 2023; 28, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lessmann, B. S. Lessmann, B. Baesens, H.-V. Seow, and L. C. Thomas. Benchmarking state-of-the-art classification algorithms for credit scoring: An update of research. European Journal of Operational Research, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Njuguna and K. Sowon. Poster: A scoping review of alternative credit scoring literature. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS), 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Coşkun and M. Turanli. Credit risk analysis using boosting methods. JAMSI, 19(1), 2023.

- Z. Qiu, Y. Z. Qiu, Y. Li, P. Ni, and G. Li. Credit risk scoring analysis based on machine learning models. In 2019 6th International Conference on Information Science and Control Engineering (ICISCE), pages 220–224. IEEE, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. E. De Lange, B. P. E. De Lange, B. Melsom, C. B. Vennerød, and S. Westgaard. Explainable AI for credit assessment in banks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 2022; 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Hayashi. Emerging trends in deep learning for credit scoring: A review. Electronics, 2022; 11, 3181. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Dumitrescu, S. E. I. Dumitrescu, S. Hué, C. Hurlin, and S. Tokpavi. Machine learning for credit scoring: Improving logistic regression with non-linear decision-tree effects. European Journal of Operational Research, 2022; 294, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Tyagi. Analyzing machine learning models for credit scoring with explainable AI and optimizing investment decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.09362, 2022. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.09362.

- A. Markov, Z. A. Markov, Z. Seleznyova, and V. Lapshin. Credit scoring methods: Latest trends and points to consider. The Journal of Finance and Data Science, 2022; 8, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. K. Roy and K. Shaw. A credit scoring model for SMEs using AHP and TOPSIS. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 2021; 28, 372–391. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, J. G. Wang, J. Ma, L. Huang, and K. Xu. A review of machine learning for credit scoring in financial risk management. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 2020; 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Crook, D. J. Crook, D. Edelman, and L. Thomas. Recent developments in consumer credit risk assessment. European Journal of Operational Research, 2007; 183, 1447–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. J. Hand and W. E. Henley. Modelling consumer credit risk. IMA Journal of Management Mathematics, 2001; 12, 139–155. [CrossRef]

- R. Anderson. The Handbook of Credit Scoring. Global Professional Publishing, 2007.

- L. C. Thomas. Consumer credit models: Pricing, profit and portfolios. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- E. I. Altman. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 1968; 23, 589–609. [CrossRef]

- A. Oualid, Y. A. Oualid, Y. Maleh, and L. Moumoun. Federated learning techniques applied to credit risk management: A systematic literature review. EDPACS, 2023; 68, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- N. Bussmann, P. N. Bussmann, P. Giudici, D. Marinelli, and J. Papenbrock. Explainable machine learning in credit risk management. Computational Economics, 2020; 56, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ala’raj, M. F. M. Ala’raj, M. F. Abbod, M. Majdalawieh, and L. Jum’a. A deep learning model for behavioural credit scoring in banks. Neural Computing and Applications, 2022; 34, 5839–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Abd Rabuh. Social networks in credit scoring: a machine learning approach. University of Portsmouth, 2023. URL: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/social-networks-in-credit-scoring-a-machine-learning-approach.

- Y. Zou and C. Gao. Extreme learning machine enhanced gradient boosting for credit scoring. Algorithms, 2022; 15, 149. [CrossRef]

- C. Serrano-Cinca and B. Gutiérrez Nieto. The use of profit scoring as an alternative to credit scoring systems in peer-to-peer (P2P) lending. Decision Support Systems, 2016; 89, 113–122. [CrossRef]

- R. Muñoz-Cancino, C. R. Muñoz-Cancino, C. Bravo, S. A. Ríos, and M. Graña. On the dynamics of credit history and social interaction features, and their impact on creditworthiness assessment performance. Expert Systems with Applications, 2023; 119599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. Smith and C. Henderson. Beyond thin credit files. Social Science Quarterly, 2017; 99, 24–42. [CrossRef]

- J. Nalić, G. J. Nalić, G. Martinović, and D. Žagar. New hybrid data mining model for credit scoring based on feature selection algorithm and ensemble classifiers. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 2020; 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Z. Lappas and A. N. Yannacopoulos. A machine learning approach combining expert knowledge with genetic algorithms in feature selection for credit risk assessment. Applied Soft Computing, 2021; 107391. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Trivedi. A study on credit scoring modeling with different feature selection and machine learning approaches. Technology in Society, 2020; 101413. [CrossRef]

- N. Arora and P. D. Kaur. A Bolasso based consistent feature selection enabled random forest classification algorithm: An application to credit risk assessment. Applied Soft Computing, 2020; 105936. [CrossRef]

- G. Kou, Y. G. Kou, Y. Xu, Y. Peng, F. Shen, C. Yang, K. S. Chang, and S. Kou. Bankruptcy prediction for SMEs using transactional data and two-stage multi objective feature selection. Decision Support Systems, 2021; 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. C. Thomas, D. B. L. C. Thomas, D. B. Edelman, and J. N. Crook. Credit Scoring and Its Applications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- M. S. Reza, M. I. M. S. Reza, M. I. Mahmud, I. A. Abeer, and N. Ahmed. Linear discriminant analysis in credit scoring: A transparent hybrid model approach. In 2024 27th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), pages 56–61. IEEE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Mahmud, M. S. M. I. Mahmud, M. S. Reza, and S. S. Khan. Optimizing stroke detection: An analysis of different feature selection approaches. In Companion of the 2024 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, pages 142–146. ACM, 2024.

- F. Elias, M. S. F. Elias, M. S. Reza, M. Z. Mahmud, S. Islam, and S. R. Alve. Machine learning meets transparency in osteoporosis risk assessment: A comparative study of ML and explainability analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.00410, arXiv:2505.00410, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Louzada, A. F. Louzada, A. Ara, and G. B. Fernandes. Classification methods applied to credit scoring: Systematic review and overall comparison. Survey of Operations Research and Management Science, 2016; 21, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- M. N. Khatun. What are the drivers influencing smallholder farmers access to formal credit system? Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Development Policy Review, 2019; 7, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Credit scoring approaches guidelines (final). Technical report, 2020. URL: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/935891585869698451-0130022020/original.

- D. Tripathi, D. R. D. Tripathi, D. R. Edla, A. Bablani, A. K. Shukla, and B. R. Reddy. Experimental analysis of machine learning methods for credit score classification. Progress in Artificial Intelligence, 2021; 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Řezáč and F. Řezáč. How to measure the quality of credit scoring models. Finance a úvěr: Czech Journal of Economics and Finance, 61(5):486–507, 2011. URL: https://is.muni.cz/do/econ/soubory/konference/vasicek/20667044/Rezac.pdf.

- Kaggle. Credit risk dataset, June 2020. URL: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/laotse/credit-risk-dataset.

- Kaggle. Credit card data from book “Econometric Analysis”, October 2017. URL: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dansbecker/aer-credit-card-data/data.

- UCI Machine Learning Repository. Default of credit card clients [dataset]. URL: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/default+of+credit+card+clients, n.d.

- Kaggle. Lending club loan data, June 2021. URL: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/adarshsng/lending-club-loan-data-csv.

- R. Sujatha, D. R. Sujatha, D. Kavitha, B. U. Maheswari, et al. Ensemble machine learning models for corporate credit risk prediction: A comparative study. SN Computer Science, 2025; 6, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Atif and M. Salmi. The most effective strategy for incorporating feature selection into credit risk assessment. SN Computer Science, 2023; 4, 96. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Dang and T. Ha. A comprehensive fraud detection for credit card transactions in federated averaging. SN Computer Science, 2024; 5, 578. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Total Instances | Percentage of Defaults | Num of Features | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Risk Dataset (CRD) | 32,581 | 21.82% | 11 | Kaggle [43] |

| Credit Card Data from ‘Econometric Analysis’ (EA) | 1,319 | 22.44% | 11 | Kaggle [44] |

| Default of credit card clients (DCC) | 30,000 | 22.12% | 23 | UCI [45] |

| Component | Hyperparameter | CRD | Econometric | DCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | n_estimators | 197 | 93 | 146 |

| max_depth | 16 | 11 | 14 | |

| min_samples_split | 9 | 5 | 5 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| max_features | sqrt | sqrt | sqrt | |

| XGBoost | n_estimators | 268 | 66 | 278 |

| max_depth | 17 | 6 | 20 | |

| learning_rate | 0.0777 | 0.0798 | 0.0562 | |

| subsample | 0.7569 | 0.7561 | 0.7343 | |

| colsample_bytree | 0.8033 | 0.8407 | 0.9077 | |

| gamma | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| reg_alpha | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | |

| Logistic Regression | C | 0.2870 | 0.0252 | 1.1999 |

| penalty | l2 | l2 | l2 | |

| solver | lbfgs | lbfgs | liblinear | |

| Meta-Learner (LR) | C | 0.5677 | 0.1931 | 0.1117 |

| fit_intercept | True | True | True | |

| Bayesian Optimization | Trials | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Acquisition Function | EI | EI | EI | |

| Initial Points | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | MCC | Cohen’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.8770 | 0.8820 | 0.8721 | 0.7540 | 0.7540 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.7031 | 0.6933 | 0.7127 | 0.4061 | 0.4061 |

| Random Forest | 0.9454 | 0.9318 | 0.9588 | 0.8911 | 0.8908 |

| K-Nearest Neighbour | 0.8597 | 0.9804 | 0.7406 | 0.7418 | 0.7199 |

| AdaBoost | 0.7840 | 0.7635 | 0.8043 | 0.5684 | 0.5679 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.8749 | 0.8319 | 0.9173 | 0.7522 | 0.7496 |

| XGBoost | 0.9484 | 0.9102 | 0.9862 | 0.8993 | 0.8968 |

| LightGBM | 0.9477 | 0.9030 | 0.9920 | 0.8990 | 0.8954 |

| CatBoost | 0.9534 | 0.9106 | 0.9955 | 0.9099 | 0.9067 |

| BO-StaEnsemble | 0.9600 | 0.9323 | 0.9822 | 0.9159 | 0.9147 |

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | MCC | Cohen’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.9878 | 0.9951 | 0.9805 | 0.9757 | 0.9756 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.9537 | 0.9171 | 0.9902 | 0.9098 | 0.9073 |

| Random Forest | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 1.0000 | 0.9951 | 0.9951 |

| K-Nearest Neighbour | 0.9000 | 0.8146 | 0.9854 | 0.8119 | 0.8000 |

| AdaBoost | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 1.0000 | 0.9951 | 0.9951 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 1.0000 | 0.9951 | 0.9951 |

| XGBoost | 0.9951 | 0.9902 | 1.0000 | 0.9903 | 0.9902 |

| LightGBM | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 1.0000 | 0.9951 | 0.9951 |

| CatBoost | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 1.0000 | 0.9951 | 0.9951 |

| BO-StaEnsemble | 1.0000 | 0.9902 | 1.0000 | 0.9903 | 0.9902 |

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | MCC | Cohen’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.7649 | 0.7837 | 0.7466 | 0.5305 | 0.5300 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.6249 | 0.6183 | 0.6313 | 0.2496 | 0.2496 |

| Random Forest | 0.8572 | 0.8430 | 0.8710 | 0.7144 | 0.7142 |

| K-Nearest Neighbour | 0.7674 | 0.9257 | 0.6137 | 0.5661 | 0.5369 |

| AdaBoost | 0.6831 | 0.6110 | 0.7530 | 0.3681 | 0.3648 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.7934 | 0.7138 | 0.8707 | 0.5927 | 0.5859 |

| XGBoost | 0.8576 | 0.8106 | 0.9033 | 0.7176 | 0.7148 |

| LightGBM | 0.8654 | 0.8123 | 0.9170 | 0.7342 | 0.7304 |

| CatBoost | 0.8788 | 0.8179 | 0.9379 | 0.7623 | 0.7571 |

| BO-StaEnsemble | 0.8800 | 0.8584 | 0.9003 | 0.7597 | 0.7591 |

| Dataset | Significant Improvements | Total Comparisons |

|---|---|---|

| CRD | 8/9 | 9 |

| ECA | 2/4 | 4 |

| DCC | 9/9 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).