1. Introduction

In practical geotechnical engineering, clay deposits rarely consist of a homogeneous material with a uniform overconsolidation ratio (OCR). Instead, they often contain strata exhibiting variations in OCR [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, geotechnical analyses should adopt a robust constitutive model capable to rigorously predicts the mechanical response of both normally consolidated (NC) and overconsolidated (OC) clays over a wide range of OCRs formulated within a unified theoretical framework.

The original Cam clay (OCC) [

9] and modified Cam clay (MCC) [

10] models were the first two models originally developed to describe the behavior of normally consolidated (NC) clays based on the critical state soil mechanic (CSSM). It is evident that in subsequent research, numerous modifications of the MCC have been proposed to enhance its applicability to geomaterials [e.g., 11–22]. For OC clays, the yield function (f) of the Modified Cam Clay model often overestimates the peak strength of heavily overconsolidated materials on the dry side of the critical state [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, it is commonly revised to better capture the OC behavior. A key feature in reformulations is the incorporation of the Hvorslev envelope [

28] into the yield function, resulting the familiar bullet- or teardrop-shaped yield surfaces. Embedding the Hvorslev envelope within the yield function of MCC not only improves the accuracy of peak-strength predictions for moderated to heavily overconsolidated clay but also ensures smooth variation of the surface gradient across the full range of stress ratios.

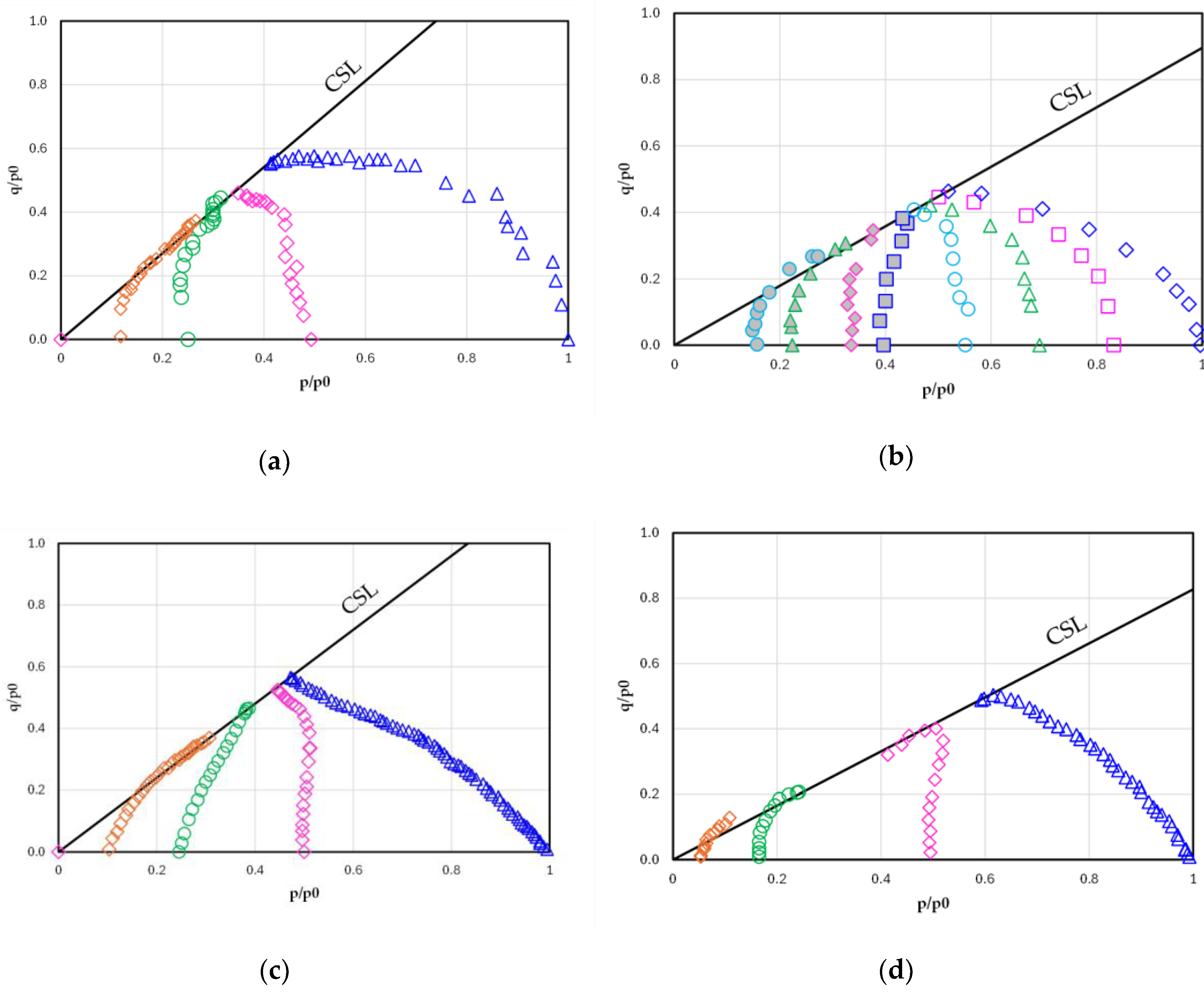

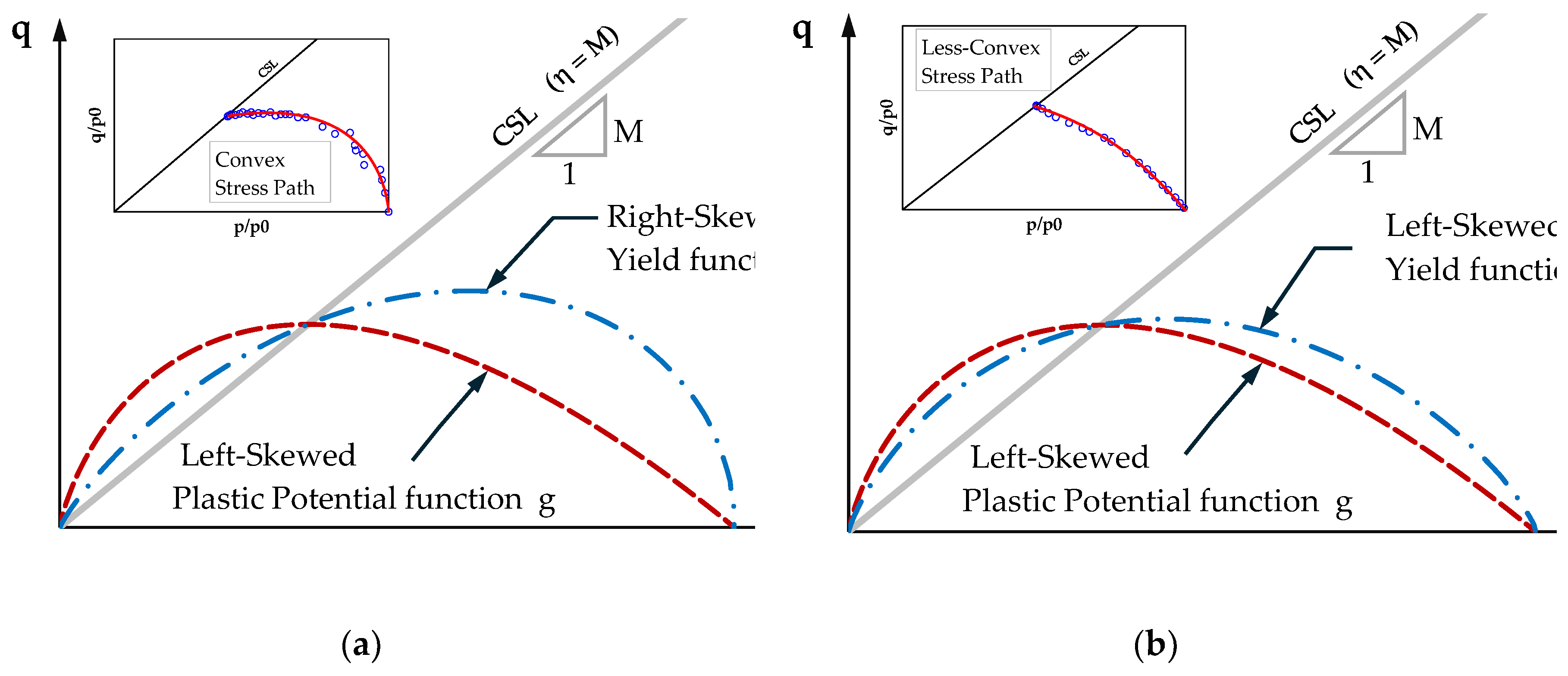

On the wet side of the bullet/teardrop yield surface, the formulation generally remains similar to the Modified Cam Clay (MCC) model. This portion of the surface provides a convex stress path for normally consolidated (NC) clay (as illustrated in

Figures 1a–b) and performs well for clays that exhibit relatively low plastic deformation under low stress ratios, η = q/p (hereafter referred to as LPLS). However, certain clays deviate from this behavior: while the models may predict responses reasonably well for overconsolidated (OC) clays with OCR > 1, they often fail to reproduce NC behavior with comparable fidelity. This limitation diminishes their practical applicability in geotechnical analysis, as inadequate representation of even a single clay stratum can compromise the reliability of the overall boundary-value solution. Such clays frequently follow nearly linear stress paths in the p–q plane, rather than the curved trajectories shown in

Figures 1c–d, reflecting the onset of substantial plastic straining from the very early stages of loading—even under low stress ratios (denoted as HPLS in this study).

In addition, in modeling normally consolidated (NC) clay, it is generally assumed that no plastic strain develops inside the yield surface. However, for overconsolidated (OC) clays, plastic strains may occur even within the yield surface. To capture this behavior, a bounding surface plasticity framework was introduced for OC clays (e.g., Ref#) with the adaptation of a non-associated flow rule, in which the yield function differs from the plastic potential function (f ≠ g). Although the exact form of g is not explicitly known, it can be evaluated based on the principle of stress dilatancy D, defined as the ratio of plastic volumetric strain to plastic deviatoric strain, given by D= (∂g/∂p) / (∂g/∂q). It should be noted that, when applying D in constitutive formulations, a paradox arises because D is often assumed to equal (∂f/∂p)/(∂f/∂q) instead of (∂g/∂p)/(∂g/∂q) [e.g., 29-31]. Therefore, to eliminate this paradox in models employing the bounding surface plasticity framework, an appropriate specification of the plastic potential function g is required.

The primary objective of this study is to develop a constitutive model capable of capturing the behavior of both normally consolidated (NC) and overconsolidated (OC) clays, with particular emphasis on NC clays that exhibit both low- and high-plastic deformation under low stress paths. To this end, two key aspects are introduced: (1) the formulation of an appropriate yield function that facilitates such modeling, and (2) the adoption of a suitable plastic potential function that eliminates the paradox from the model formulation.

2. Formulations of the Constitutive Model

2.1. Yield and Plastic Potential Functions

As mentioned earlier, the yield surface in the MCC model is known to overestimate the shear strength on the dry side, which reduces the predictive accuracy of the model. To correct this limitation, the bullet/teardrop-shaped yield surfaces are often introduced. In this study, the proposed model to be applicable to clays exhibiting both low and high plasticity under low stress ratios η, the yield function must be sufficiently versatile. Specifically, under low stress ratios, it should allow a right-skewed teardrop form which is suitable for low-plasticity overconsolidated (OC) clays, as well as a left-skewed teardrop form which is more appropriate for high-plasticity OC clays. The proposed yield function is presented in Equation 1 which contain additional model parameter (

), and effect of the corresponding variation of parameter

to yield function is depicted in

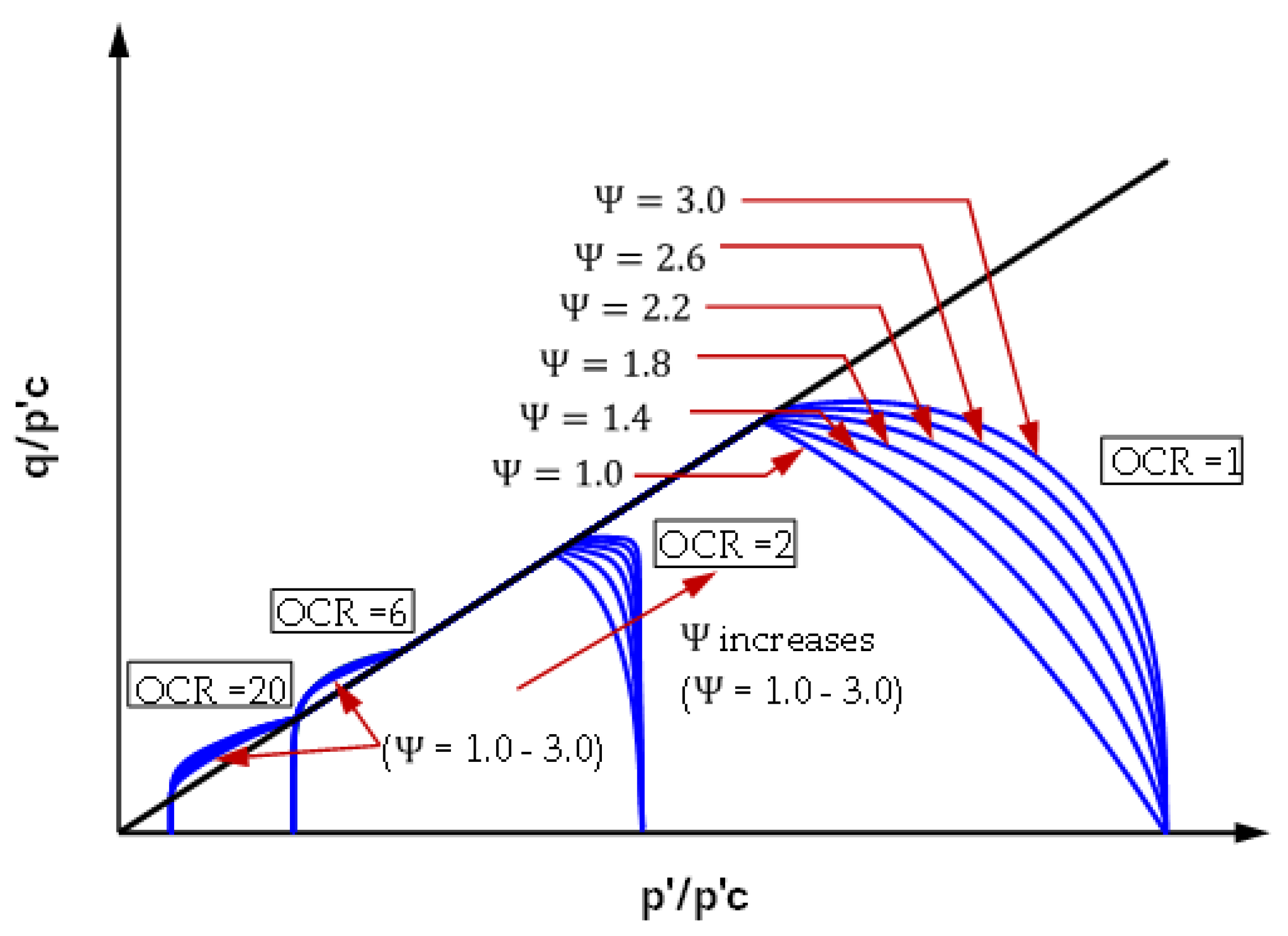

Figure 2.

A general form of the yield function, once plastic strain develops beyond zero after loading has commenced, incorporates a hardening parameter H, which is defined as a function of plastic strain as follows:

and

As shown in

Figure 2, a left-skewed teardrop form can be reproduced with

=1.0, whereas a right-skewed teardrop form is obtained with

=2.0. In practice, the parameter

may be varied within the range of 1.0–2.0 to best capture the stress path in the p–q space for both normally consolidated (NC) and overconsolidated (OC) clays. It should also be noted that values of

greater than 2.0 are permissible; such values accentuate the height of the teardrop shape on the right-hand side, which is consistent with the behavior of lower-plasticity clays under low stress ratios.

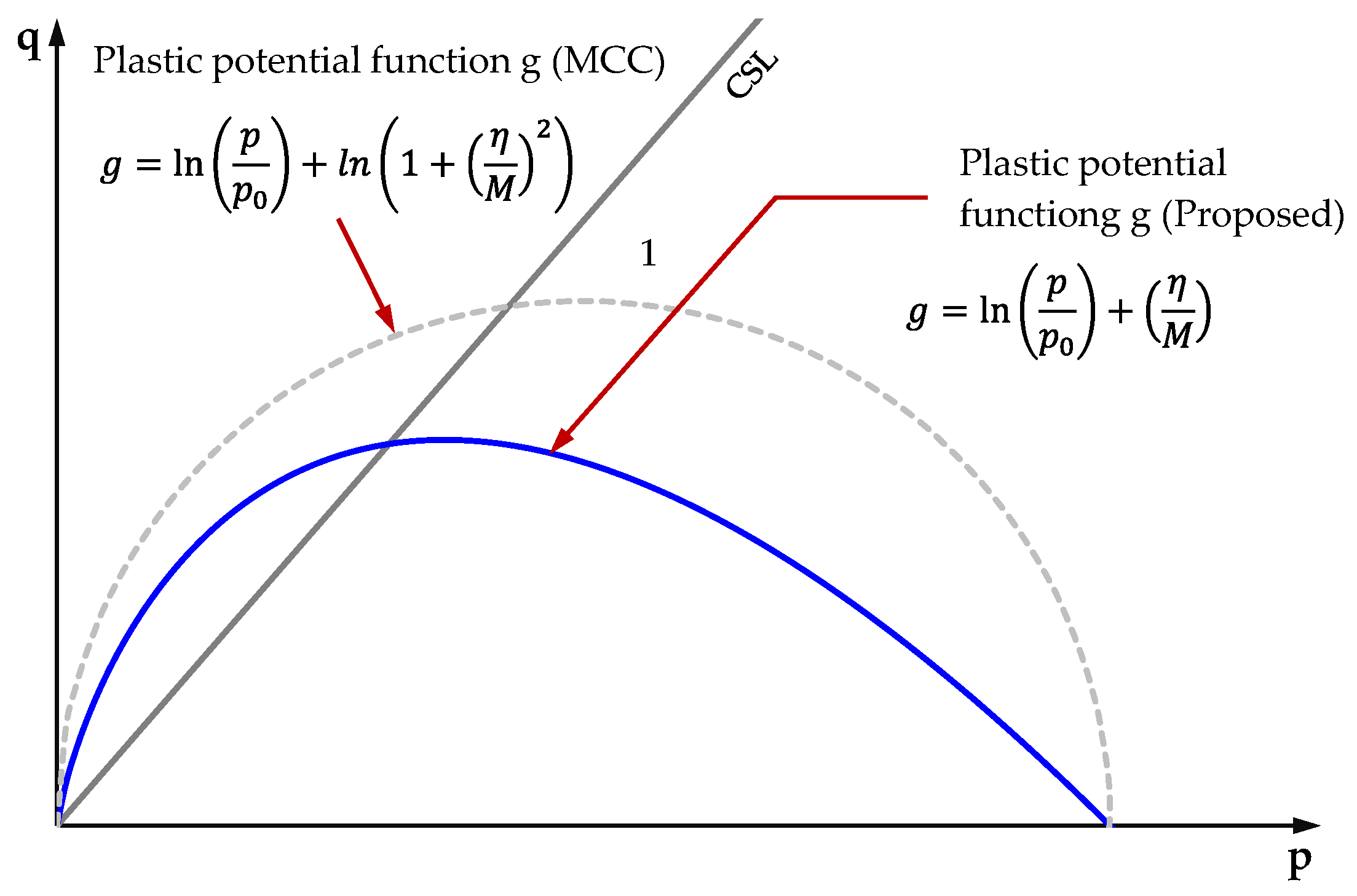

In the study of [

32], the shape of the plastic potential surface g was found to resemble the left-skewed teardrop form of without a specific equation. Motivated by this observation, this study adopted a closed-form expression of the yield function of the original Cam clay (OCC) [

9] as the plastic potential function g, represented as a left-skewed teardrop similar to [

32], as expressed in Equation 4.

Figure 3.

Plastic potential function g of the proposed model compared with that of the MCC [

10] model.

Figure 3.

Plastic potential function g of the proposed model compared with that of the MCC [

10] model.

In the proposed model, the yield function f and the plastic potential function g are formulated to operate in tandem, thereby enhancing the predictive capability for both normally consolidated (NC) and overconsolidated (OC) clays, encompassing low- and high-plasticity soils under low stress ratios. The framework can be categorized into two representative forms, as illustrated in

Figure 4. In

Figure 4a, f exhibits a right-skewed curve while g adopts a left-skewed curve, a combination that is particularly suited to modeling low-plasticity clays under low stress ratios (LPLS). Conversely,

Figure 4b presents a pair of left-skewed surfaces for both f and g, which proves more appropriate for capturing the behavior of high-plasticity clays at low stress levels (HPLS).

2.2. Dilatancy Equation

An important advantage of employing stress dilatancy is that it enables the simulation of both volumetric and deviatoric plastic strains, even when the plastic potential function is not explicitly defined. In the classical bounding-surface plasticity framework, the plastic potential function g is not readily obtained in closed form. Accordingly, the literature commonly adopts the stress-dilatancy relation—defined as the ratio of the volumetric to the deviatoric plastic strain increments—which can be identified more straightforwardly from experiments. This ratio, referred to as stress dilatancy, is typically expressed as shown in Equation 5.

For OC clays, the most widely adopted expression of D is the second-order dilatancy formulation of the Modified Cam-Clay (MCC) type [e.g., 29,33-35]. Although higher-order stress dilatancy relations have also been proposed to capture the behavior of both normally consolidated (NC) and OC clays [30-31], closer examination reveals that, for stress ratios η not exceeding the critical state stress ratio M (approximately 1.3–1.4), a first-order or linear dilatancy relation provides satisfactory predictions and yields results comparable to the second-order formulation. Moreover, as highlighted in [

30], although a high-order dilatancy expression was proposed, the parameter values adopted in practice often reduce the equation to, or make it nearly equivalent to, a linear approximation. This observation is supported by

Figure 5, which presents the relationship between D and η for Fujinomori Clay and Lower Cromer till. The results confirm that, within the practical range of η, a linear approximation D-η remains appropriate. In addition, opting for such a simplified linear form facilitates practical implementation while maintaining predictive adequacy.

In the proposed model, an explicit expression for g is formulated, as shown in Equation 4, thereby eliminating the paradox entirely. The expressions for ∂g/∂P and ∂g/∂Q can be derived as presented in Equations 6–7.

Substituting Equation 6 and Equation 7 into Equation 5 yields:

It is evident that the expression for D in Equation 8 is linear, which is consistent with the experimental data for Fujinomori clay [

36] and Lower Chrome till [

37] presented in

Figure 5. Accordingly, the plastic potential function is shown to be in agreement with the experimental results without introducing any paradox within the model.

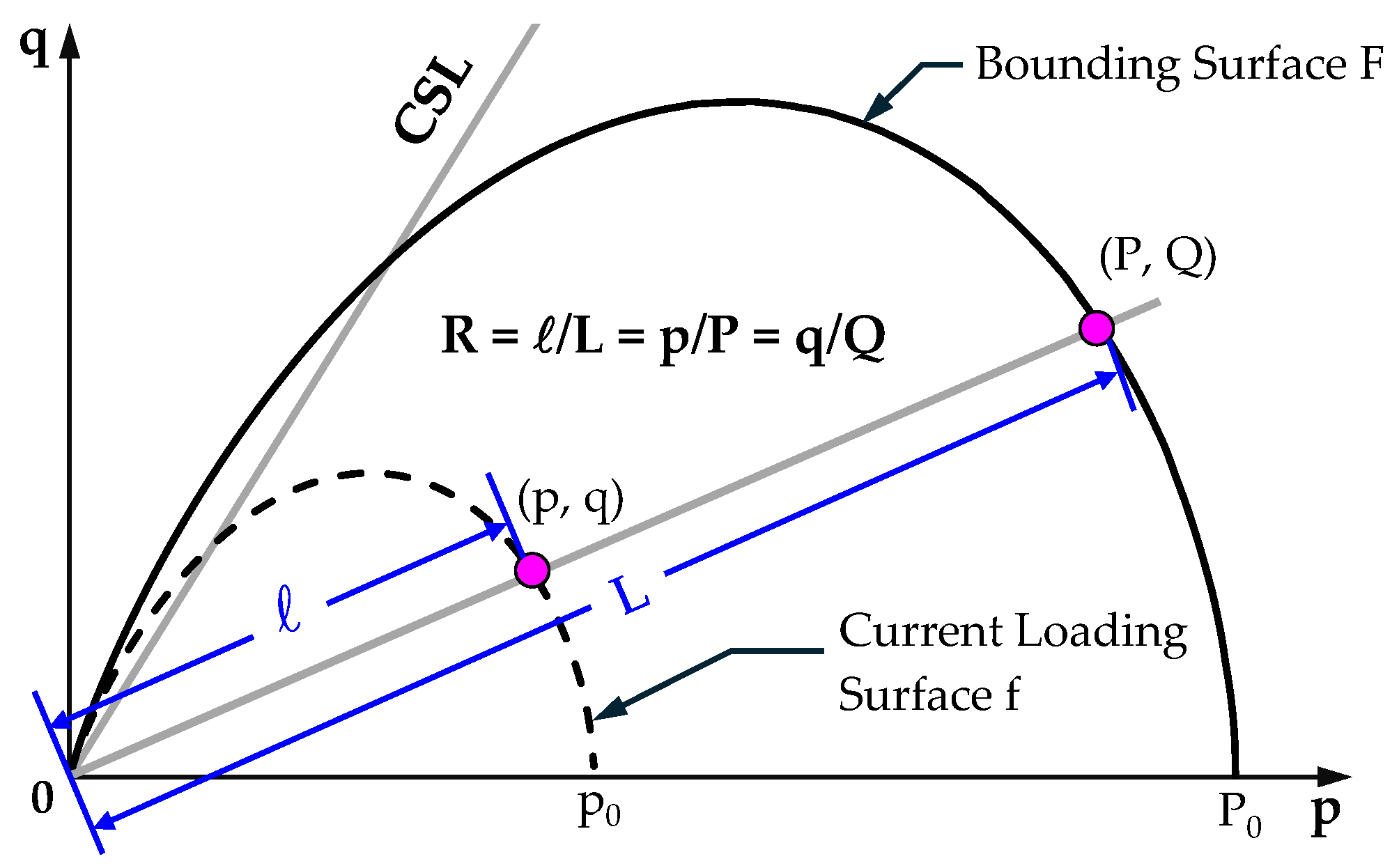

2.3. Bounding Surface

Once the yield surface has been properly defined, the bounding surface can be established by employing the principle of a smooth transition from the OC state to the NC state. Hence, the shape of the bounding surface is identical to that of the yield surface defined in Equation 1. The bounding surface employed in this model is expressed as follow:

where

is the model parameter controlling the shape of the bounding surface. The distinctive feature of this formulation is that the bounding surface can take a left-skewed form (

=1) or a right-skewed form (

=2). In general,

=1.0 is appropriate for soils whose stress paths for NC clay on the p–q plane is nearly linear, corresponding to high plastic deformation under low stress ratios (HPLS). By contrast, values of

in the range of approximately 1.2–1.4 are suitable for soils exhibiting low plastic deformation under low stress ratios (LPLS). The equations required for elastoplastic computations

,

and

are presented in Equations 10-12, respectively.

Another fundamental aspect in modeling overconsolidated (OC) clays is the application of the mapping rule. In general, the mapping rule establishes a correspondence between the stress state located at the current stress point—commonly referred to as the loading surface—and the stress state defined on the bounding surface. This linkage facilitates a smooth transition from the OC state to the normally consolidated (NC) state through the spacing ratio

, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Typically, both surfaces are assumed to share a similar shape, with the current loading surface being smaller in size and nested within the bounding surface.

2.4. Hardening Law and Plastic Modulus

Although, for the OC state, the stress of clay lies on a portion of the unloading–reloading line on e-log(p) plane with a slope equal to κ, where conventional calculations give only purely elastic strains though a constant κ/(1+e0). However, in the bounding surface plasticity framework, it is common to introduce an alternative approach to enable OC clays to develop plastic strains in addition to elastic strains. Specifically, it assumes that the stress point lies on the isotropic compression line which has a slope of λ. This conceptual framework not only allows the model to capture plastic strains in OC clays but also provides a rational basis for employing the parameter Cp=(λ–κ)/(1+e0) in the hardening law. Accordingly, the isotropic hardening law can be consistently applied to both the NC and OC states within a unified framework. The hardening law employed in this model is expressed as follows:

where e0 and

are the initial void ratio, volumetric plastic strain increment, respectively. From Equation 13, for a single sub-step computation,

can be determined as

For the plastic modulus Kp which is employed together with the proportional constant

to determine the change of the hardening parameter in consistency condition which expressed as

. By substituting this relation into Equation 3 and rearranging, the expression for Kp can be obtained as presented in Equation 14.

Upon closer examination Equation 14, using stress point (P, Q) is highly restricted to OCR=1, because P and Q are located on the bounding surface. To allow Kp valid for OCR>1—i.e., for stress states on the loading surface that is nested within the bounding surface—it is therefore necessary to revise Kp so it remains applicable to both normally and overconsolidated clays.

A key mechanism enabling plastic strain for stress points located inside the bounding surface via Kp is that Kp must be a positive number at the critical state. However, as given by Equation 14, Kp vanishes at the critical state which is a condition appropriate for normally consolidated clay but unsuitable for overconsolidated clay. To address this, Dafalias and Herrmann (1986) [

38] proposed the concept of a virtual peak stress ratio, Mk, to replace M in Equation 14, thereby providing a smoother and more accurate description of OC behavior. The expression for Mk is shown in Equation 15.

where M is the stress ratio at the critical state, R is the spacing ratio, and n is a positive parameter. Since the spacing ratio R equals 1 when the stress state lies on the bounding surface, Mk becomes identical to M, but takes values greater than M when the stress point lies inside the bounding surface. Consequently, for cases with OCR>1, the stress–strain response may exhibit a peak at a stress ratio exceeding M.

The parameter n in Equation 15 is introduced to adjust the virtual stress ratio Mk, and consequently the plastic modulus Kp. When OCR=1, the parameter n has no effect because the spacing ratio R equals unity. Although many models employ a constant value for n. However, for OCR>1, a value of n should lead to a different value of both Mk and Kp. Intuitively, this suggests that n may not be a constant but rather a quantity related to the soil’s overconsolidation history, since its influence on model responses varies with OCR. In [

29] a power-law regression for n-OCR has been proposed. Nevertheless, this equation may be compatible only with specific constitutive models, depending on the mapping rule adopted. In this study, a new n–OCR relationship is proposed as presented in Equation 16.

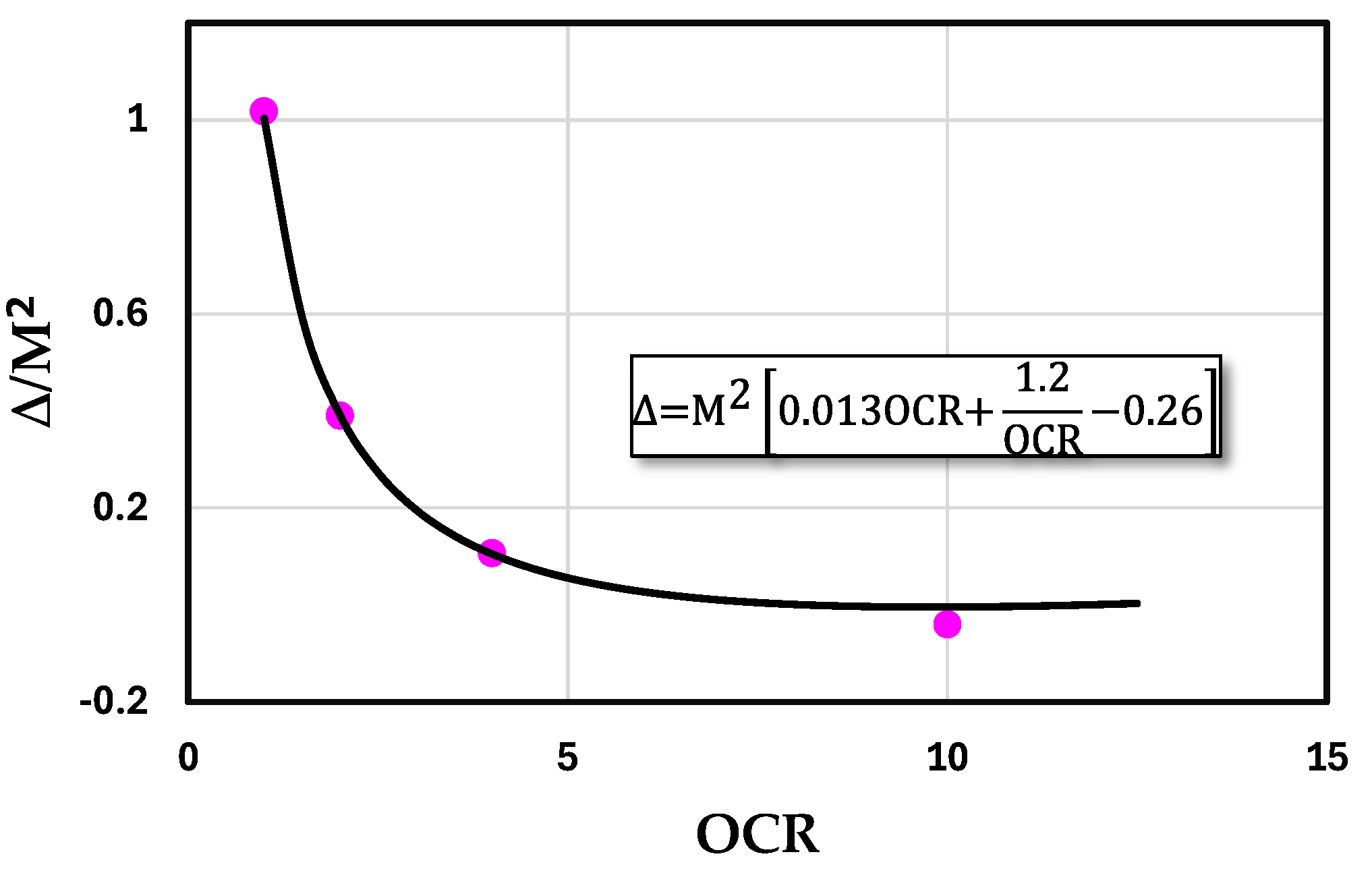

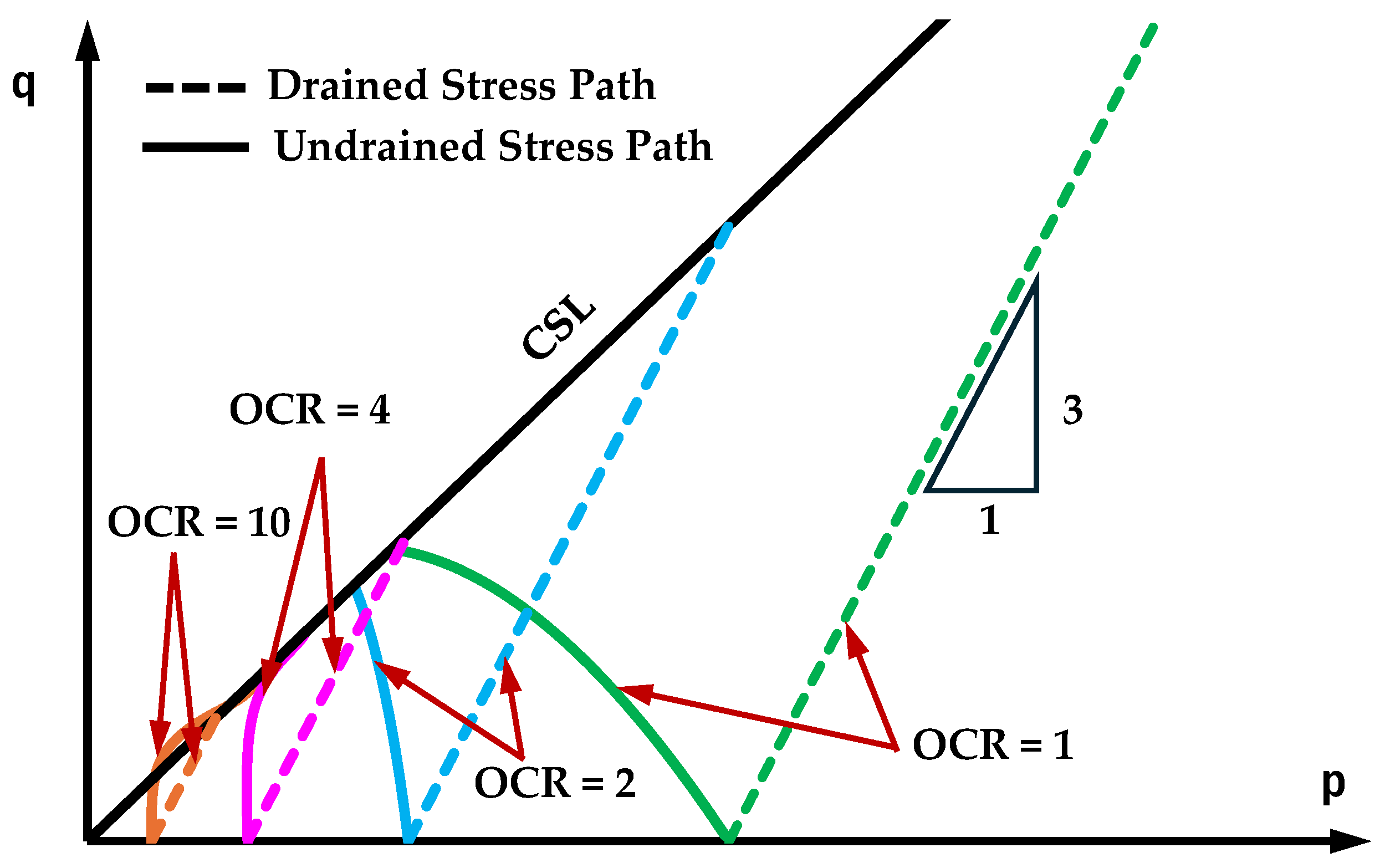

Another crucial issue in considering the parameter n is whether it should take the same value for both undrained and drained loading conditions. It is well known that the drained shear strength is generally higher than the undrained shear strength due to the pore pressure that develops during undrained loading. However, the difference between drained and undrained shear strength (Δ) decreases with increasing OCR.

Figure 7 depicts the typical paired stress paths for drained and undrained conditions across various OCR values, clearly demonstrating that the shear strength difference is OCR-dependent. Moreover,

Figure 7 also reveals that the critical state stress ratio M exerts an additional influence on Δ; specifically, larger values of M correspond to greater values of Δ. Hence, the relationship can be expressed as Δ = f(OCR, M).

In this study, the relationship among Δ, OCR, and M is presented in

Figure 4 and expressed in Equation 17. From Equation 17, it can be observed that Δ is more precisely defined as Δ = f(OCR, M

2). Accordingly, it may be inferred that the parameter M

2 plays a key role in differentiating the value of n between drained and undrained cases. The specific expression for n under drained loading is provided in Equation 18.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the disparity between drained and undrained shear strengths at the critical state for various OCR values.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the disparity between drained and undrained shear strengths at the critical state for various OCR values.

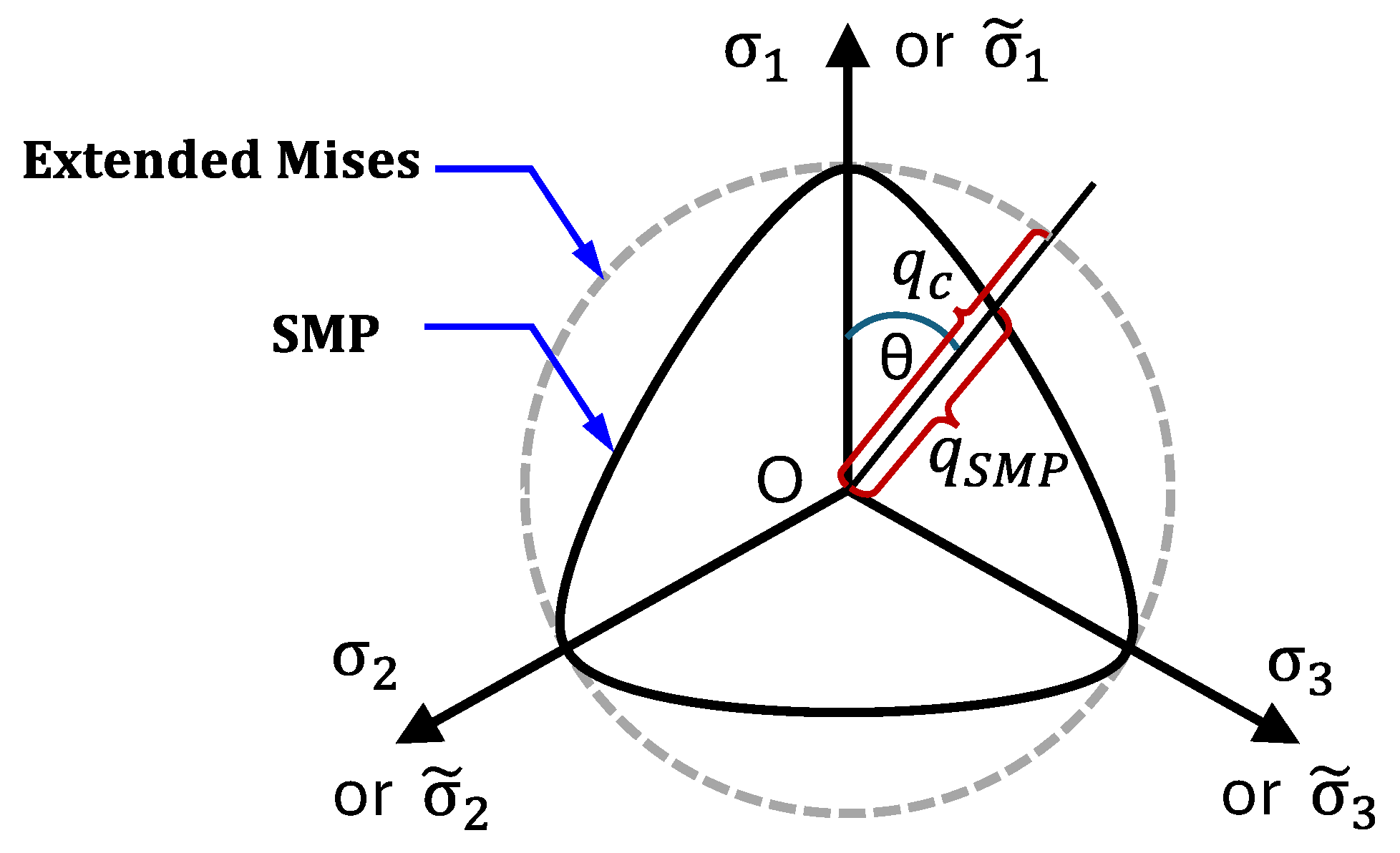

3. Elastoplastic Constitutive Relations

The constitutive models employing the stress p and q implicitly adopt the Extended Mises failure criterion, which forms a circular failure envelope on the π-plane and typically leads to an overestimation of shear strength. This limitation can be eliminated by employing the SMP failure criterion [

13] as shown in

Figure 9. The present model also adopts this approach by employing a transformed stress formulation to integrate the SMP criterion to the proposed model. A brief description of the transformed stress and the SMP criterion is provided prior to presenting the governing equations of the proposed model.

3.1. Transformed Stress Tensor

A transformed stress tensor

is employed instead of the ordinary stress tensor

in the analyses to improve shear strength prediction by introducing the SMP criterion [

13]. Once the

is given, the

can be calculated as follows:

where

is the Kronecker’s delta,

and

are the mean stress and deviatoric stress tensor calculated from the ordinary stress tensor, respectively,

and

are the mean stress and deviatoric stress tensor calculated from the transformed stress tensor, respectively, which can be written as

and

are the radius of the circular cone and the Extended Mises cone which can be calculated using

where

,

and

are the first, second, and third stress invariants, respectively.

3.2. Stress–strain Modelling for Elastoplastic Constitutive Model

The total strain increment

is decomposed into elastic

and plastic

components as follows:

In the calculation of

, it can be computed by applying the consistency condition (dF = 0) conjunction with application of chain rule, as shown in Equation 17.

Thus,

It is worth noting that

in Equation 24 is highly beneficial for conducting drained analyses, since the pore pressure is zero and the input data can therefore be directly expressed in terms of the stress increments dP and dQ. In contrast, for undrained analyses, the input for the computation (especially in the numerical analyses) must be given in terms of strain increments with the condition of

=0. The corresponding calculations can then be carried out as follows.

Where

and the elastic bulk and shear modulus can be expressed in term of the initial void ratio e0, the Poisson’s ratio

and the slope of unloading-reloading line in e-ln(p) plane (

as

The elastic and plastic strain increment can be written as follows:

thus,

where h(

)=1 for

>0, and h(

)=0 when

<0. The stress-strain relationship can be calculated as

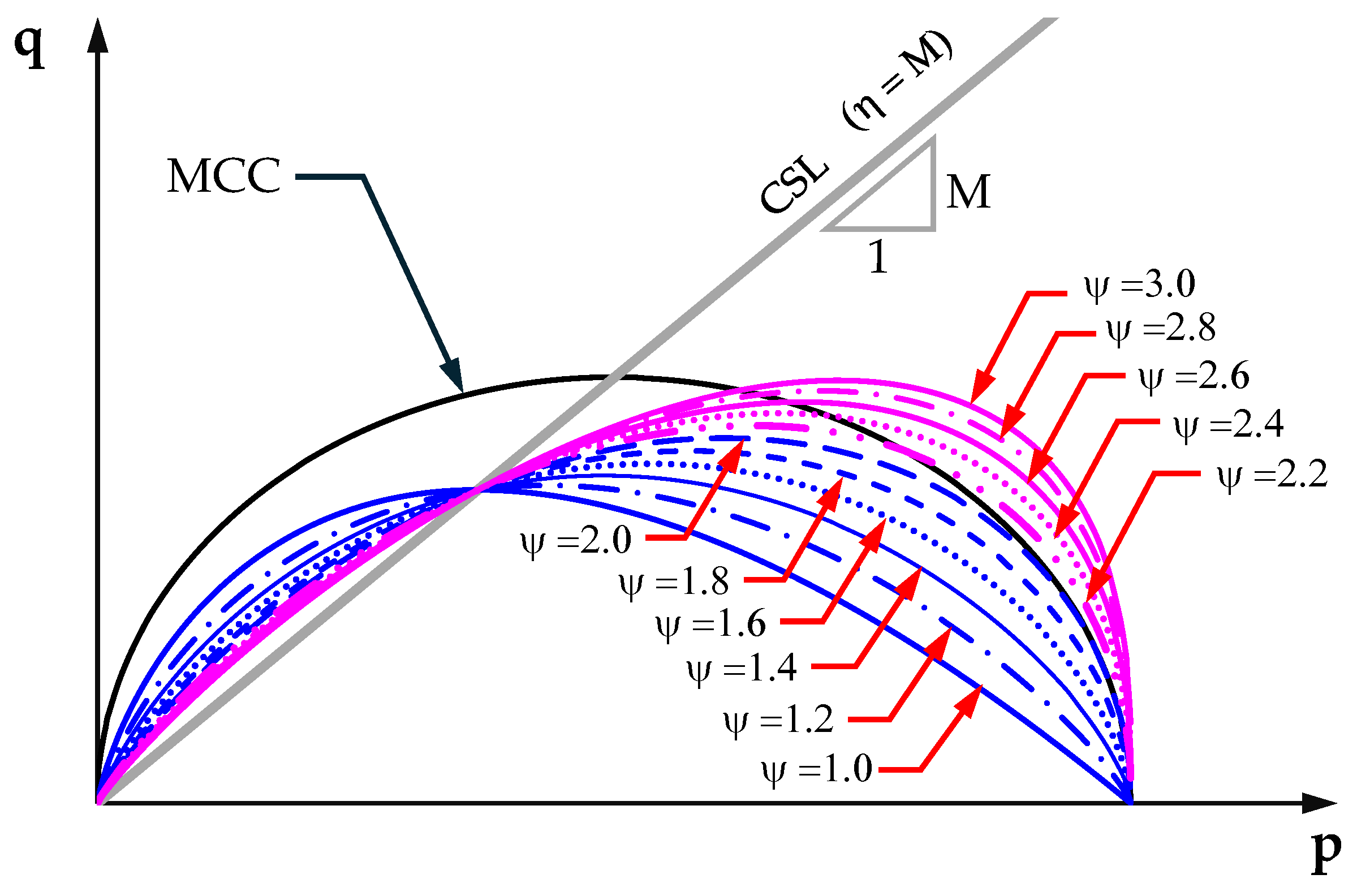

Before presenting a comparison between the analytical results of the proposed model and the experimental data in the following section, the final part of this section illustrates the variation of the model’s predictions, with particular emphasis on the influence of the parameter Ψ. This parameter constitutes a key factor enabling the model to reproduce clay behavior as either HPLS or LPLS across different OCR values.

Figure 10 depicts the normalized stress paths (p′/p′c – q/p′c) for OCR values of 1, 2, 6, and 20 conjunctions with Ψ in the range of 1.0–3.0. It can be observed that Ψ effectively captures the characteristic responses of HPLS and LPLS for normally consolidated clays (OCR = 1) as well as for slightly to moderately overconsolidated clays (OCR ≈ 2). However, in the case of heavily overconsolidated clays, the results converge, showing little distinction across different Ψ values. This outcome is consistent with the aforementioned aim of this study.

on normalized stress path p’/p’c - q/p’c for various OCR.

4. Model Verifications

In this section, the results obtained from the proposed model are presented for both drained and undrained analyses. The results are compared against experimental data for four clays i.e., Boston Blue clay (OCR = 1, 2, 4 and 8), Lower Cromer till (OCR = 1, 2, 4 and 10), Kaolin clay (OCR = 1, 1.2, 1.45, 1.8, 2.5, 3, 4.5 and 6.5) and London clay (OCR = 1, 2, 6 and 20). Furthermore, for each of these clays, the experimental results are systematically compared with predictions from three constitutive models: (I) the proposed model, (II) the model introduced by Xu et al., 2024 [

30], and (III) the model developed by Chen and Yang, 2017 [

29]. The soil parameters used in the analyses for 3 models mentioned above are summarized in

Table 1.

4.1. Undrained Analysis

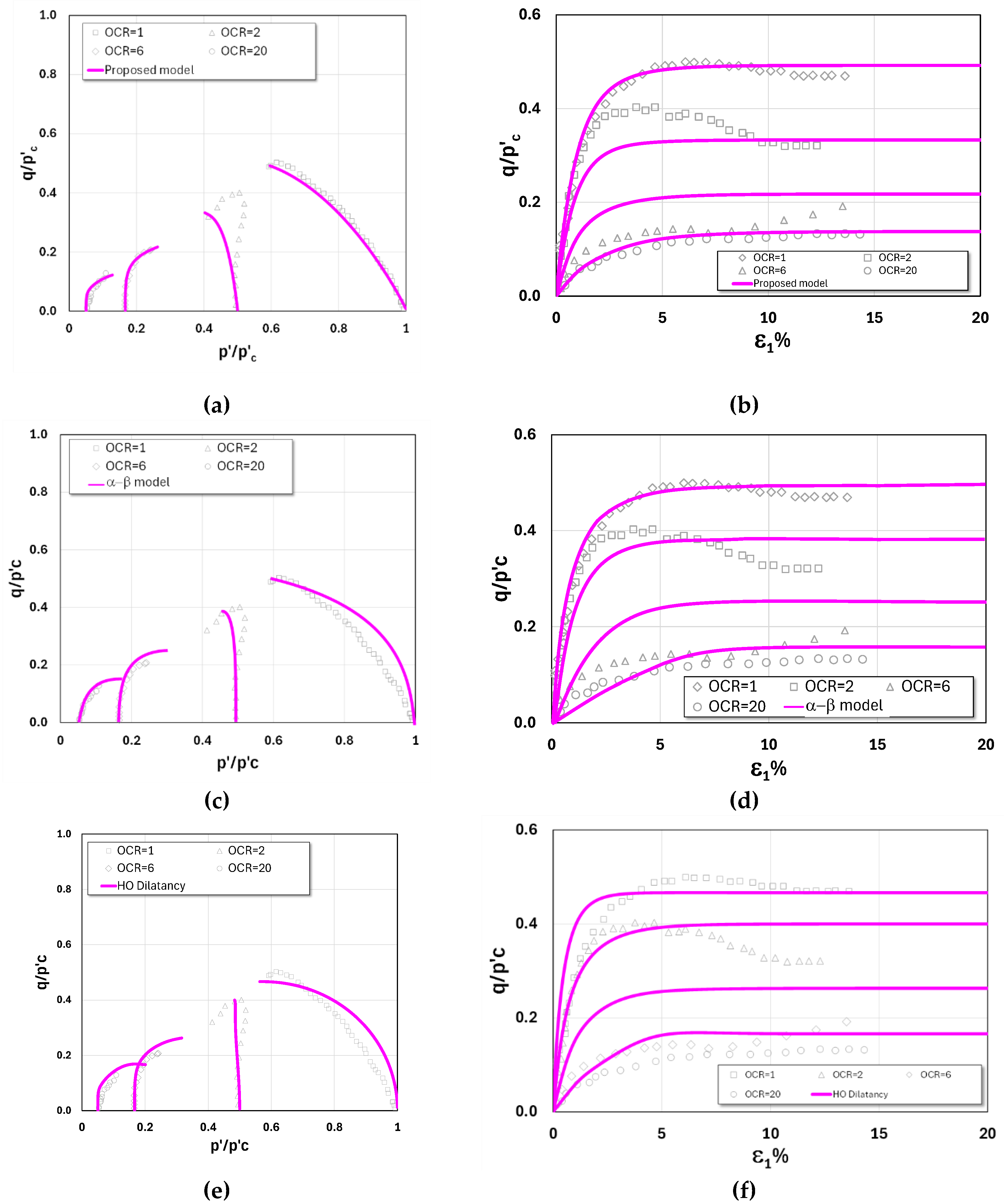

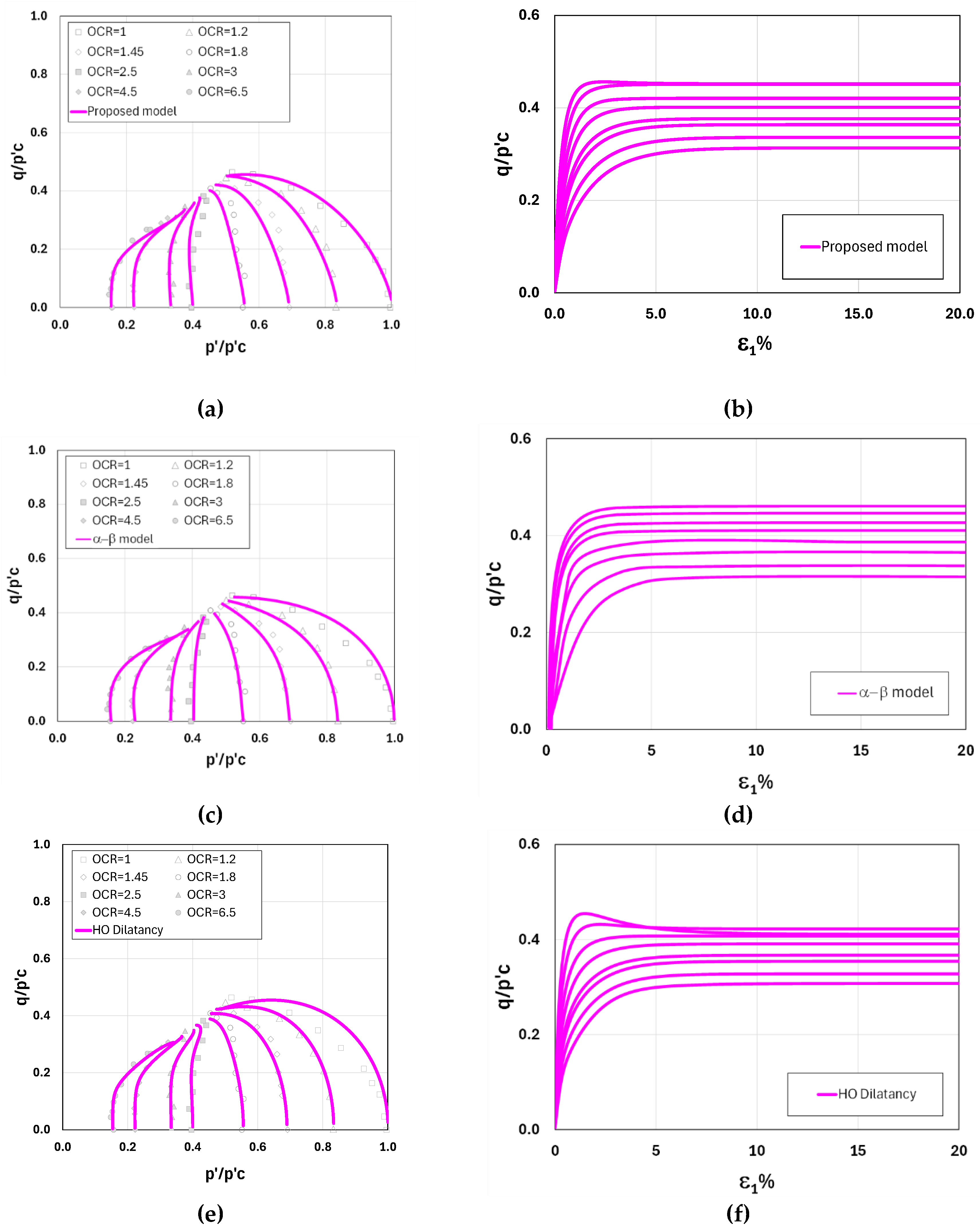

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present comparisons between the triaxial compression test results and the predictions of the three aforementioned models, shown separately for each model to highlight their differences. In particular, the proposed model demonstrates superior capability in modeling the high plasticity under low stress ratio (HPLS) behavior compared with the other models. The corresponding comparison for the undrained triaxial extension test is provided in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

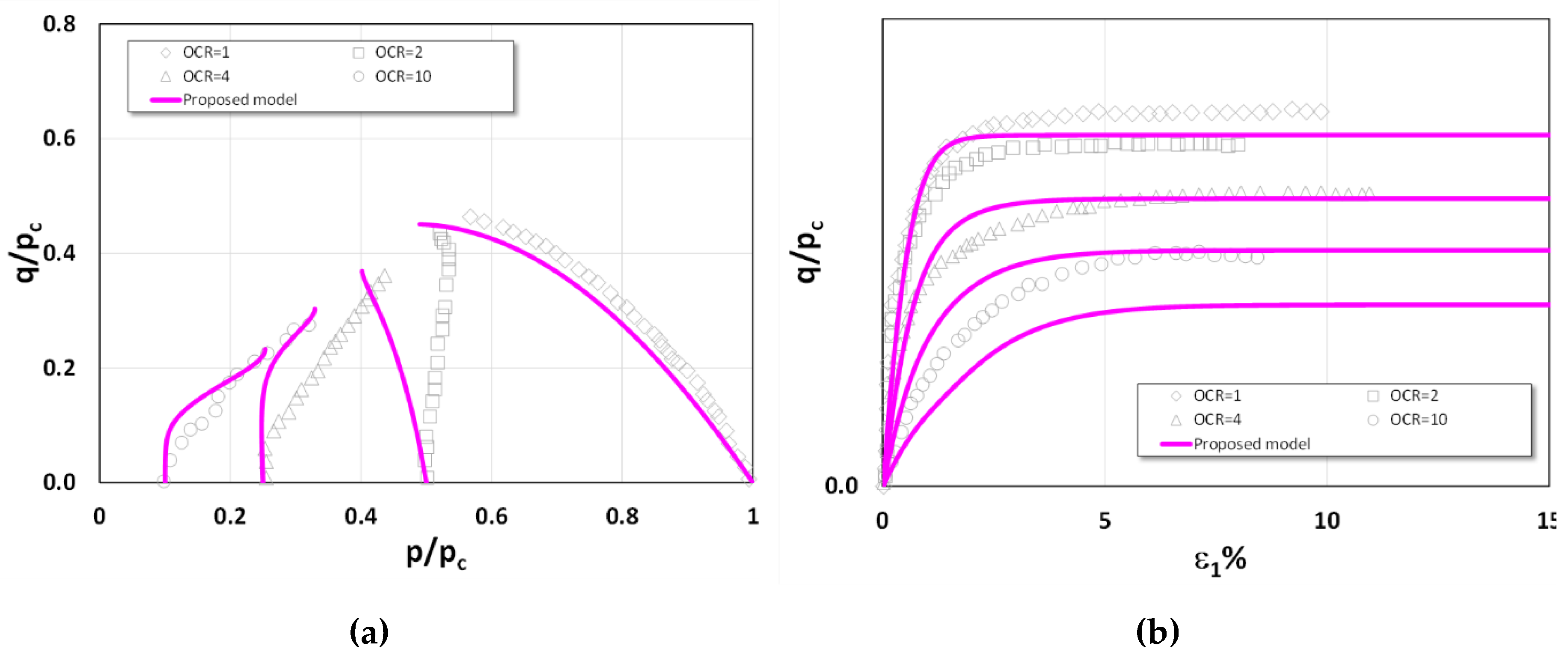

It is clearly evident from the triaxial compression test results of London clay and Lower Cromer Till, shown in

Figure 11, respectively. Both London clay and Lower Cromer till can be classified as exhibiting high plasticity under low stress levels (HPLS), as the stress paths for OCR = 1 display a pronounced inclination from the very onset of loading—a characteristic not commonly observed. Nevertheless, the proposed model provides predictions that align closely with the experimental results. By contrast, in both figures, the other two models of Xu et al. (2024) and Chen and Yang (2017) fail to capture this behavior adequately. Their predicted stress paths instead correspond to low plasticity under low stress levels (LPLS). In addition, it is observed that for both soils, all the models yield comparable predictions when OCR > 2.

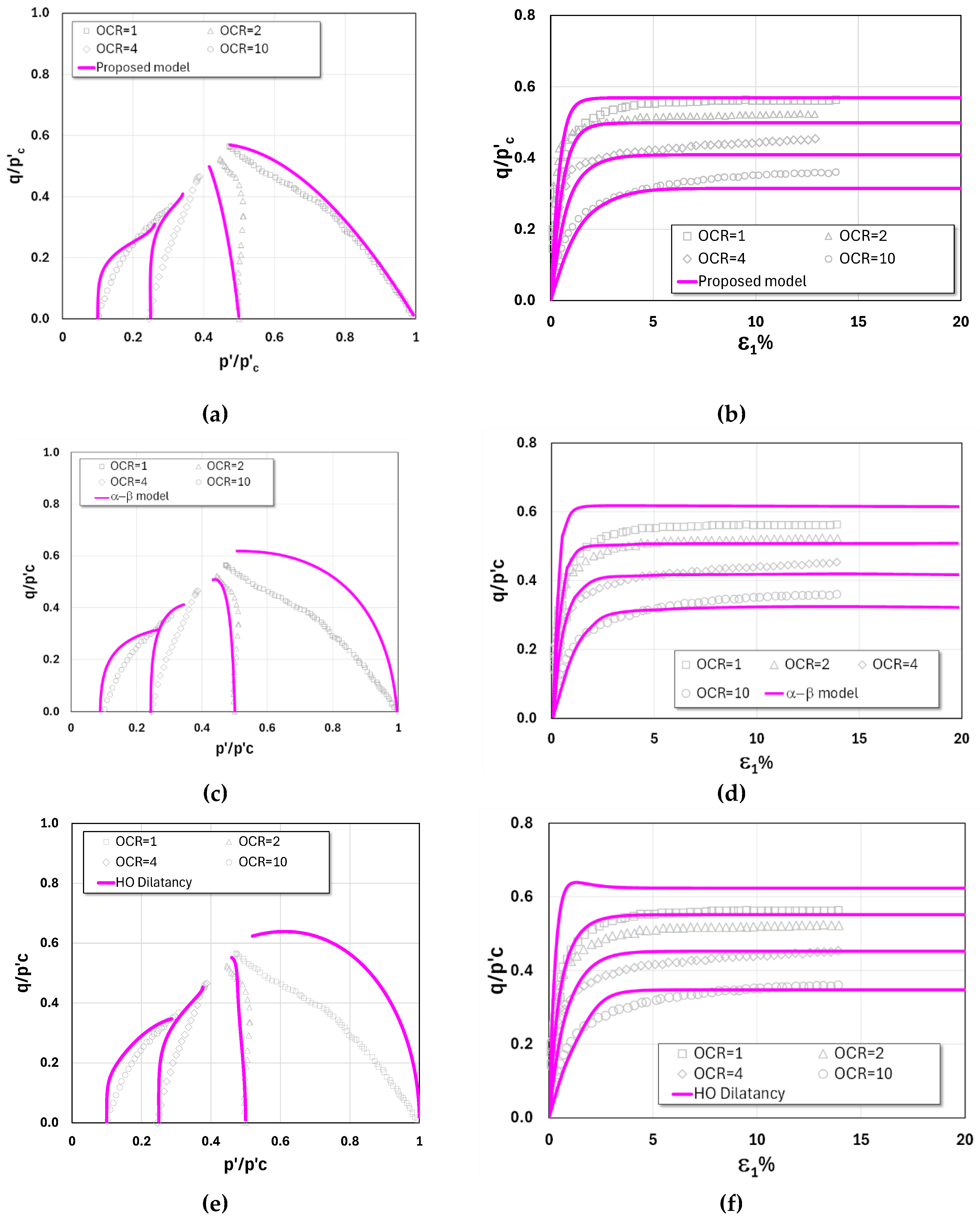

For the experimental results of Boston Blue Clay and Kaolin Clay, shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, respectively, the stress paths at OCR = 1 exhibit a pronounced curvature consistent with the bullet/teardrop-shaped yield surface in bounding surface models. This behavior is characteristic of clays classified as having low plasticity under low stress ratios (LPLS). In both figures, all three models successfully reproduce stress paths consistent with LPLS behavior. Among them, the proposed model and the model of Xu et al. 2024) demonstrate relatively high accuracy across all OCR values, whereas the model developed by Chen and Yang (2017) provides reasonable accuracy only for OCR > 1, while at OCR = 1 it tends to overestimate the response.

For the undrained triaxial extension tests on Lower Cromer Till shown in

Figure 15, the simulated stress paths are in good agreement with the experimental results, and the model also reproduces shear strengths comparable to the tests at OCR = 1, 2, 4, and 10. This is attributed to the use of the SMP failure criterion, which accurately captures the shear strength envelope, thereby reflecting the well-known fact that the undrained triaxial extension shear strength is lower than that under undrained triaxial compression. It should be noted that Lower Cromer till under undrained loading exhibits high-plasticity behavior at low stress ratios (HPLS) in both compression and extension, underscoring the existence of clays that truly fall into the HPLS category. By contrast, for the undrained triaxial extension tests on Kaolin clay (

Figure 16), the stress path exhibits low-plasticity behavior at low stress ratios (LPLS). In this case, the model underestimates the shear strength at OCR = 1 and 1.2 but provides close agreement with the experimental data at OCR = 6 and 10.

4.2. Drained Analysis

To further evaluate the predictive capability of the proposed model, three drained triaxial compression test results were selected for comparison. In addition to the Lower Cromer till, the parameters and test results of two other clays—Shanghai clay and Fujinomori clay—were also considered in the investigation, as summarized in

Table 2.

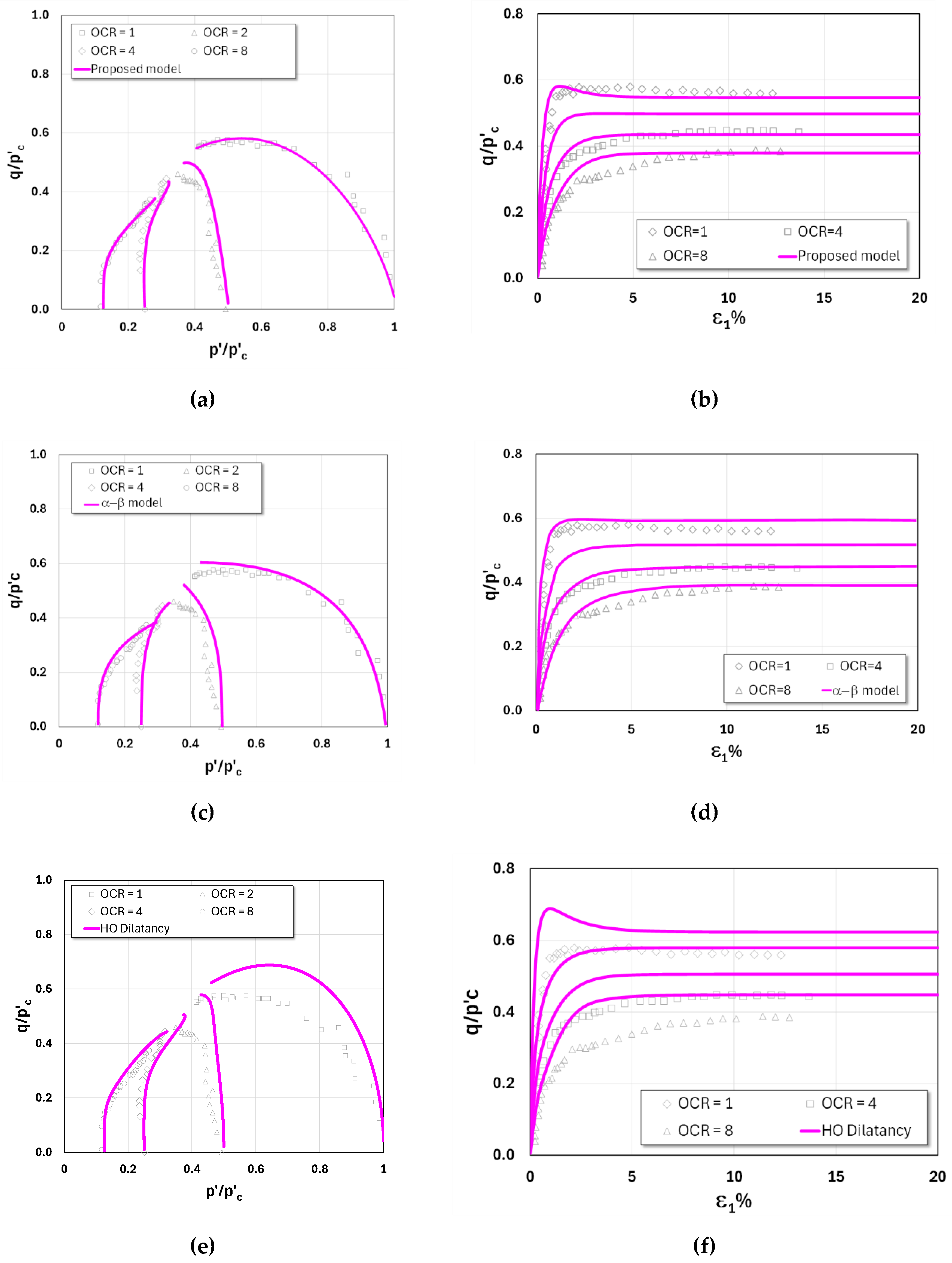

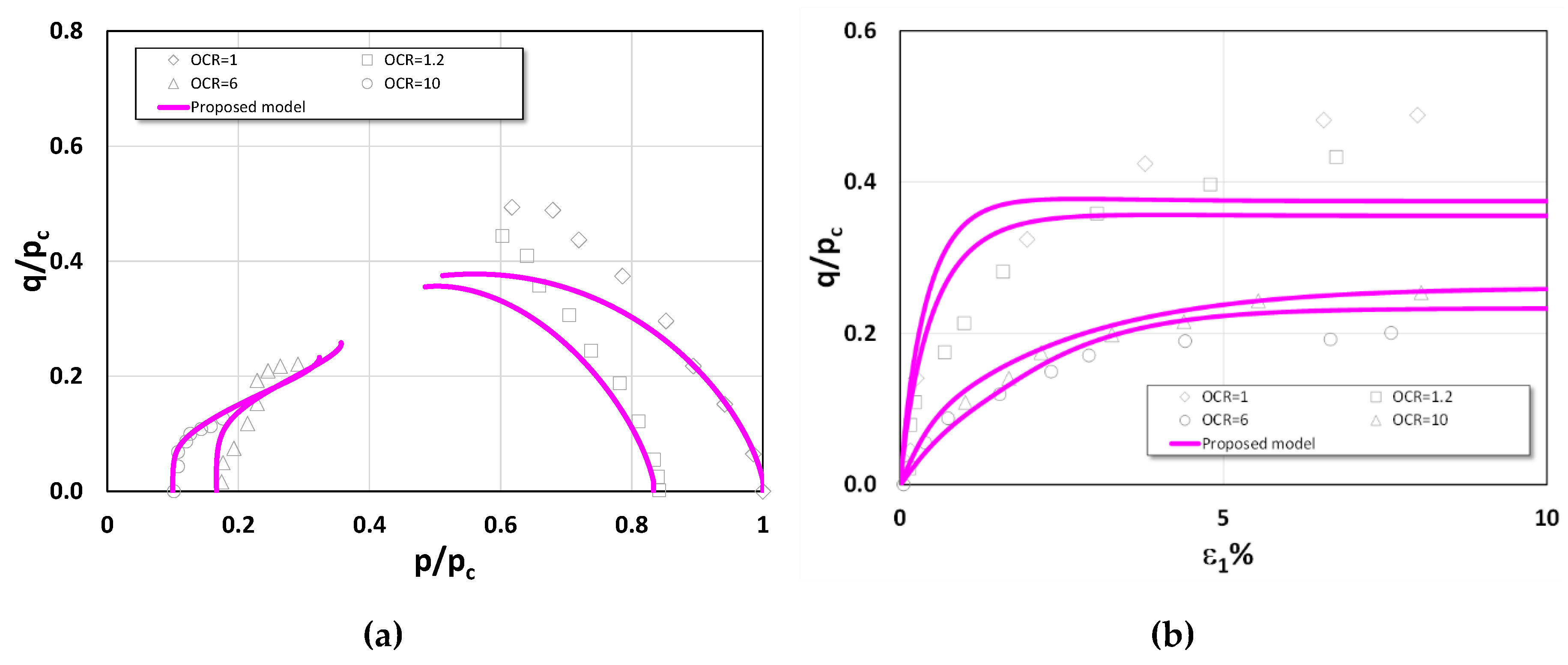

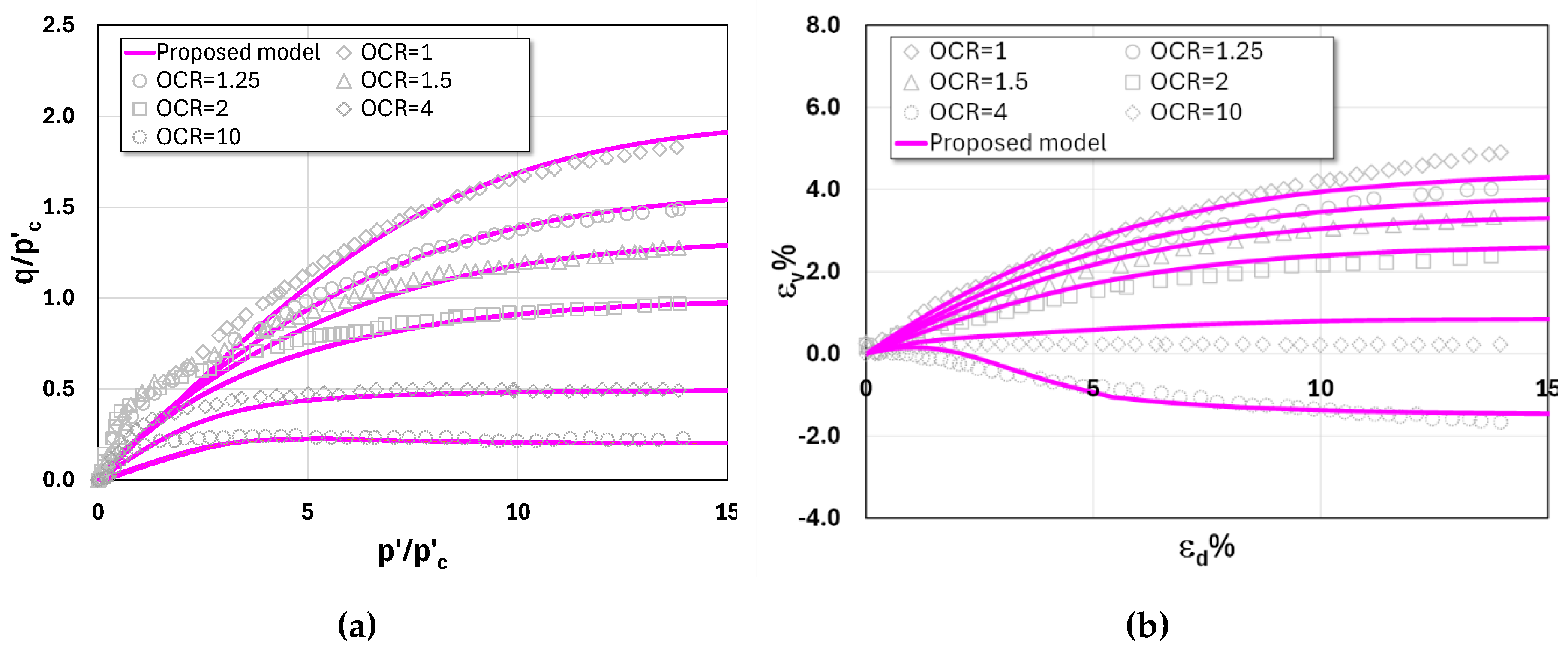

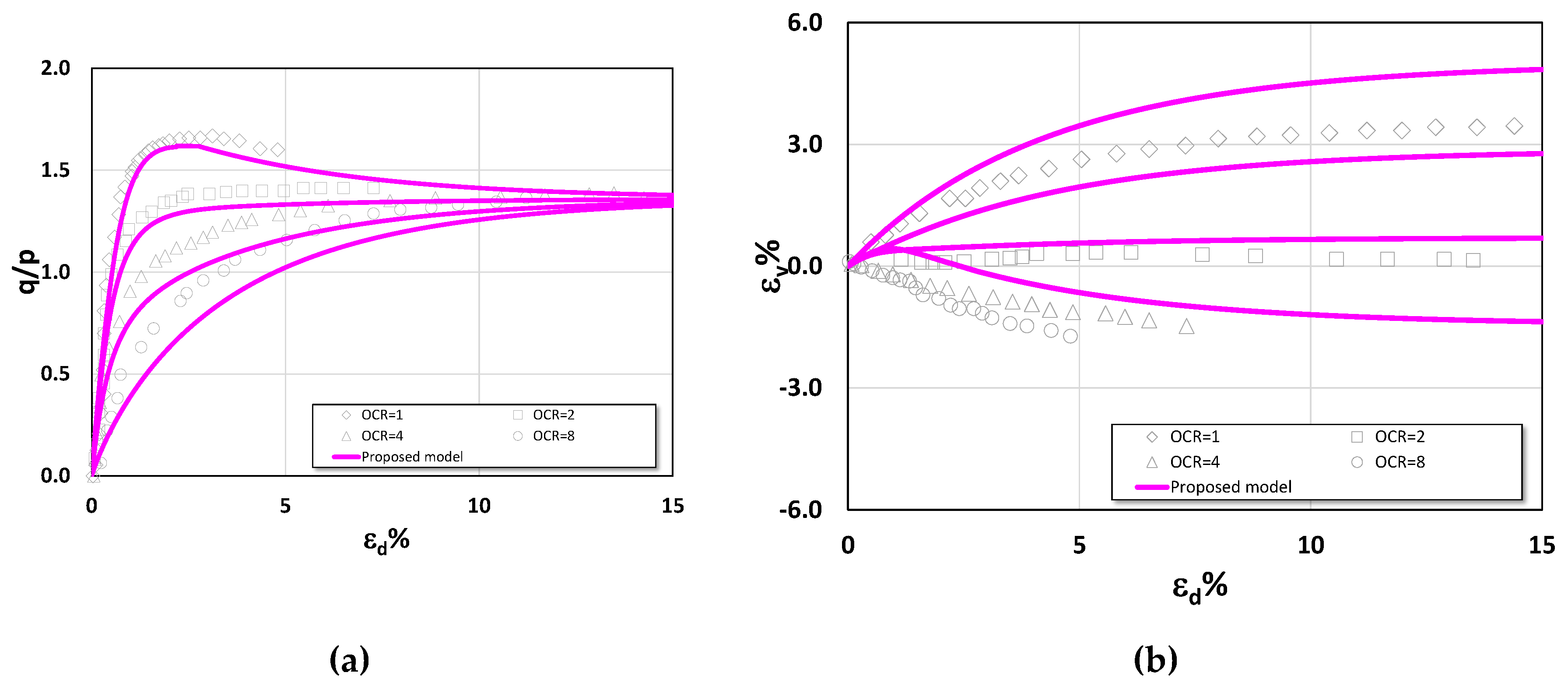

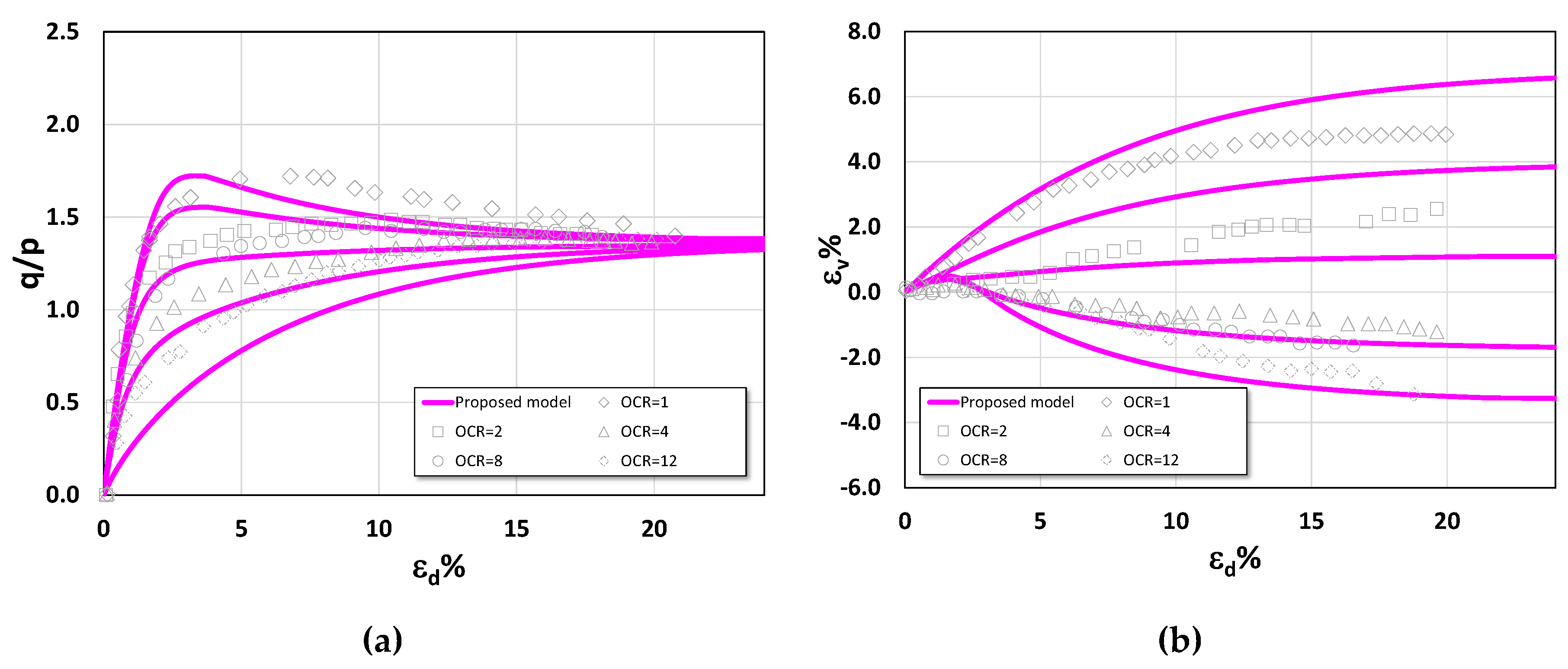

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 present the test results and corresponding model predictions for Lower Cromer till (OCR = 1, 1.25, 1.5, 2.0, 4.0, and 10), Fujinomori clay (OCR = 1, 2, 4, and 8), and Shanghai clay (OCR = 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12).

The comparisons in

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 show a close agreement between the experimental data and model predictions. For Lower Cromer till, the normalized stress–strain curves reveal contractive behavior at OCR = 1–4, characterized by curved stress paths without a distinct peak, along with residual shear strengths that vary systematically with OCR. In contrast, Shanghai clay exhibits contractive behavior without a peak at OCR = 1–4, but transitions to a contractive response followed by dilation at OCR = 8 and 10. Notably, for all OCR values, Shanghai clay develops essentially the same residual shear strength. Fujinomori clay demonstrates responses similar to Shanghai clay: contractive behavior without a peak at OCR = 1–4, followed by contractive behavior and subsequent dilation at OCR = 8, with residual shear strength remaining nearly constant across all OCR values. The proposed model successfully captures this behavior in close agreement with the experimental results.

5. Conclusions

This study advances a unified bounding-surface plasticity formulation that reproduces both high-plasticity and low-plasticity clay responses under low stress ratios across a wide range of OCRs. The model’s core ingredients—a teardrop yield surface governed by two shape parameters Ψ and , an explicit plastic potential function g that removes the long-standing dilatancy paradox, a linear stress-dilatancy relation D = M−η for practical calibration, a virtual peak ratio linked to OC behavior, and SMP-based strength correction via transformed stresses—work in tandem to deliver a coherent, implementation-friendly framework. Together, these elements provide a smooth NC↔OC transition, preserve numerical robustness, and avoid ad-hoc switching between distinct models when layered deposits mix HPLS and LPLS characteristics.

Verification against undrained triaxial compression data shows that the proposed model captures the atypically steep, near-linear NC stress paths of London Clay and Lower Cromer till (HPLS) where two recent alternatives misclassify the response as LPLS—while maintaining high fidelity for Boston Blue and Kaolin clays (LPLS). Drained comparisons further demonstrate correct reproduction of contractive responses at low OCR and the contractive-to-dilative transition at higher OCR (with appropriate residual strength trends) in Lower Cromer Till, Shanghai clay, and Fujinomori clay. These results collectively highlight that a single Ψ-controlled family of surfaces, coupled with an explicit plastic potential function and OCR-aware hardening, is sufficient to recover the salient features of both LPLS and HPLS clays without inflating parameter sets or resorting to higher-order dilatancy forms.

From an engineering standpoint, the proposed model yields substantial, concrete benefits: (i) a single, unified framework that reproduces both HPLS and LPLS behaviors without ad-hoc model switching; (ii) a smooth NC–OC transition governed by the shape parameters Ψ and , preserving behavioral continuity across OCRs; (iii) parameter parsimony and straightforward calibration from standard triaxial and oedometer data, reducing practitioner burden; (iv) faithful recovery of steep, near-linear NC stress paths (HPLS) as well as curved LPLS trajectories over OCR ≈ 1–20; (v) consistent capture of contractive responses and contractive-to-dilative transitions together with realistic residual-strength trends; and (vi) interpretability—key parameters tied to measurable indices and critical-state descriptors—facilitating quality control and communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and N.K.; methodology, T.C., N.P. and N.K.; software, T.C. and N.K.; validation, T.C., N.K. and A.K.; formal analysis, T.C. and N.K.; investigation, T.C. and N.P.; resources, T.C., S.I. and N.P.; data curation, T.C., N.P. S.I. and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., N.K., S.K., N.P. A.K. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, T.C., N.K., S.K., A.K. and S.S.; visualization, S.K., S.I. and S.S.; supervision, N.K., S.K. and A.K.; project administration, T.C., S.I. and S.S.; funding acquisition, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mahasarakham University.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Mahasarakham University. The support is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that they are no conflict of interest with respect to the publication of this paper.

References

- Bo, M.W.; Arulrajah, A.; Sukmak, P.; Horpibulsuk, S. Mineralogy and geotechnical properties of Singapore marine clay at Changi. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, M.W.; Arulrajah, A.; Leong, M.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Disfani, M.M. Evaluating the in-situ hydraulic conductivity of soft soil under land reclamation fills with the BAT Eng. Geol. 2014, 168, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Newson, T. Undrained capacity of circular shallow foundations on two-layer clays under combined VHMT loading. Wind Eng 2023, 46, 579–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, D.J.; Landon, M.E.; Poirier, S.E. Geology and engineering properties of sensitive Boston Blue Clay at Newbury, Massachusetts. AIMS Geosci 2019, 5, 412–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutenegger, A.J. Geotechnical Behavior of Overconsolidated Surficial Clay Crusts. Transp. Res. Rec. 1995, 1479, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mesri, G.; Ali, S. Undrained shear strength of a glacial clay overconsolidated by desiccation. Geotechnique 1999, 49, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.F. Interpretation of overconsolidation ratio from in situ tests in Recent clay deposits in Singapore and Malaysia. Can. Geotech. J. 1991, 28, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaiby, S.S.; Mayne, P.W. Analytical CPTU Solutions Applied to Boston Blue Clay. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2022, Charlotte, North Carolina, 20–23 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe, K.H.; Schofield, A.N.; Wroth, C.P. On the Yielding of Soils. Geotechnique 1963, 13, 211–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, K.H.; Burland, J.B. On the generalized stress–strain behaviour of ‘wet’ clay. In Engineering Plasticity; Heyman, J., Leckie, F.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968; pp. 535–609. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, N.; Murata, H.; Yasufuku, N. Stress-strain characteristics of sand in a particle-crushing region. Soils Found. 1984, 24, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.T.; Morgenstern, N.R.; Sego, D.C. A constitutive model for broken ice. Cold Reg Sci Technol 1900, 17, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, H.; Yao, Y.P.; Sun, D.A. The Cam-Clay Models Revised by the SMP Criterion. Soils Found. 1999, 39, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.P.; Sun, D.A.; Luo, T. A Critical state model for sands dependent on stress and density. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2004, 28, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.P.; Sun, D.A.; Matsuoka, H. A unified constitutive model for both clay and sand with hardening parameter independent on stress path. Comput. Geotech. 2008, 35, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebsuk, J.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Liu, M.D. A critical state model for overconsolidated structured clays. Comput. Geotech. 2011, 38, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.F.; Teh, C.I.; Chang, M.F. Undrained cavity expansion in modified Cam clay I: Theoretical analysis. Geotechnique 2001, 51, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, G.; Degago, S.A.; Nordal, S. Modeling creep and rate effects in structured anisotropic soft clays. Acta Geotech. 2010, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.Y.; Xu, Q.; Hicher, P.Y. A simple critical-state-based double-yield-surface model for clay behavior under complex loading. Acta Geotech. 2013, 8, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, P.A.M.N.; Vargas, E.A.; Moraes, A. Evaluation of the Modified Cam Clay model in basin and petroleum system modeling (BPSM) loading conditions. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 112, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.Y.; Liu, C.C.; Chin, C.K. Anisotropic viscoplastic modeling of rate-dependent behavior of clay. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2011, 35, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewhanam, N.; Chaimoon, K. A Simplified Silty Sand Model. Appl. Sci. 2023; 13, 8241. [Google Scholar]

- Gens, A.; Potts, D.M. Critical State Models in Computational Geomechanics. Eng. Comput. 1988, 5, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.P.; Hou, W.; Zhou, A.N. UH model: three-dimensional unified hardening model for overconsolidated clays. Geotechnique 2009, 59, 451–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, K.A.; Dasari, G.R.; Lo, K.W. Performance of a Three-Dimensional Hvorslev-Modified Cam Clay Model for Overconsolidated Clay. Int. J. Geomech. 2004, 4, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wan, Z. Modified UH Model: Constitutive Modeling of Overconsolidated Clays Based on a Parabolic Hvorslev Envelope. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2012, 138, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiampousi, A.; Zdravković, L.; Potts, D.M. A New Hvorslev Surface for Critical State Type Unsaturated and Saturated Constitutive Models. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 48, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvorslev, M.J. Über die Festigkeitseigenschaften Gestörter Bindiger Böden: With an Abstract in English; Danmarks Naturvidenskabelige Samfund: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1937; No. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.N.; Yang, Z.X. A family of improved yield surfaces and their application in modeling of isotropically over-consolidated clays. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 90, 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, K.; Pang, R. A bounding surface model for overconsolidated clays with unified plastic potential function in triaxial and general stress state. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 172, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yin, Z.Y. Dilatancy relation for overconsolidated clay. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 06016035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, B.; Taheri, E.; Eftakhari, M. Anisotropic bounding surface plasticity model for soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, C.X.; Liu, H.W.; Li, H.C. Constitutive modeling of normally and over-consolidated clay with a high-order yield function. Mathematics. 2022, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szypcio, Z.; Dołżyk-Szypcio, K. Stress-dilatancy behaviour of remoulded Fujinomori clay. Stud. Geotech. Mech. 2023, 45, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.M. Soil Behaviour and Critical State Soil Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, T.; Hinokio, M. A simple elastoplastic model for normally and over consolidated soils with unified material parameters. Soils Found. 2004, 44, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gens, A. Stress–strain and strength of a low plasticity clay. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College, University of London, London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dafalias, Y.F.; Herrmann, L.R. Bounding surface plasticity. II: Application to isotropic cohesive soils. J. Eng. Mech. 1986, 112, 1263–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparre, A. Advanced Laboratory Characterisation of London Clay. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, J.M.; Whittle, A.J.; Gens, A. Evaluation of a constitutive model for clays and sands: Part II–clay behaviour. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 2002, 26, 1123–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroth, C.P.; Loudon, P.A. The correlation of strains within a family of triaxial tests on overconsolidated samples of kaolin. In Proceedings of the Geotechnical Conference, Oslo, Norway; 1967; Volume 1, pp. 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.A.; Chen, B.; Zhou, K. Experimental study of compression and shear deformation characteristics of remolded Shanghai soft clay. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Stress paths of four clays, illustrating the characteristic features of low-plastic deformation under low stress ratios (LPLSR) in (a) and (b), and high-plastic deformation under low stress ratios (HPLSR) in (c) and (d): (a) Boston Blue Clay; (b) Kaolin Clay; (c) Lower Cromer till; (d) London Clay.

Figure 1.

Stress paths of four clays, illustrating the characteristic features of low-plastic deformation under low stress ratios (LPLSR) in (a) and (b), and high-plastic deformation under low stress ratios (HPLSR) in (c) and (d): (a) Boston Blue Clay; (b) Kaolin Clay; (c) Lower Cromer till; (d) London Clay.

Figure 2.

Yield function curves for different values of Ψ.

Figure 2.

Yield function curves for different values of Ψ.

Figure 4.

Yield function f and plastic potential function g pairs adopted in this study: (a) for LPLS; (b) for HPLS.

Figure 4.

Yield function f and plastic potential function g pairs adopted in this study: (a) for LPLS; (b) for HPLS.

Figure 5.

Stress ratio–dilatancy relationships from experiments: (

a) Fujinomori Clay [

36]; (

b) Lower Cromer till (LCT)[

37].

Figure 5.

Stress ratio–dilatancy relationships from experiments: (

a) Fujinomori Clay [

36]; (

b) Lower Cromer till (LCT)[

37].

Figure 6.

Definition of the spacing ratio R.

Figure 6.

Definition of the spacing ratio R.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the disparity between drained and undrained stress path and shear strengths at the critical state for various OCR values.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the disparity between drained and undrained stress path and shear strengths at the critical state for various OCR values.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the failure envelopes of the Extended Mises and SMP criteria on the π-plane.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the failure envelopes of the Extended Mises and SMP criteria on the π-plane.

Figure 10.

Effects of parameter

Figure 10.

Effects of parameter

Figure 11.

Test results vs model predictions of London clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 11.

Test results vs model predictions of London clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 12.

Test results vs model predictions of Lower Cromer till in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 12.

Test results vs model predictions of Lower Cromer till in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 13.

Test results vs model predictions of Boston Blue clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 13.

Test results vs model predictions of Boston Blue clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 14.

Test results vs model predictions of Kaolin clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 14.

Test results vs model predictions of Kaolin clay in undrained triaxial compression Test: (a-b) model I (proposed model); (c-d) model II; and (e-f) model III.

Figure 15.

Test results vs model predictions of Lower Cromer till in undrained triaxial extension Test: (a) normalized stress path (p/pc – q/pc); (b) stress-strain relations.

Figure 15.

Test results vs model predictions of Lower Cromer till in undrained triaxial extension Test: (a) normalized stress path (p/pc – q/pc); (b) stress-strain relations.

Figure 16.

Test results vs model predictions of Kaolin clay in undrained triaxial extension Test: (a) normalized stress path (p/pc – q/pc); (b) stress-strain relations.

Figure 16.

Test results vs model predictions of Kaolin clay in undrained triaxial extension Test: (a) normalized stress path (p/pc – q/pc); (b) stress-strain relations.

Figure 17.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Lower Cromer till for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Figure 17.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Lower Cromer till for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Figure 18.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Fujinomori clay for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Figure 18.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Fujinomori clay for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Figure 19.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Shanghai clay for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Figure 19.

Comparison between triaxial drained test results and model prediction of Shanghai clay for different OCRs: (a) normalized effective stress paths; (b) stress–strain behavior.

Table 1.

Soil parameters of the models used in the undrained analyses.

Table 1.

Soil parameters of the models used in the undrained analyses.

| Source of Clay |

Basic Parameters |

|

|

Extra Parameters |

| λ |

κ |

ν |

Mc |

e0 |

|

Ψ1

|

Ω1

|

χ2

|

β02

|

n2

|

α3

|

β3

|

| London clay [39] |

0.168 |

0.064 |

0.25 |

0.827 |

1.843 |

|

1.1 |

0.95 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

| Lower Comer till [37] |

0.063 |

0.018 |

0.30 |

1.200 |

0.747 |

|

1.0 |

1.05 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

| Boston blue clay [40] |

0.184 |

0.036 |

0.10 |

1.353 |

2.059 |

|

1.4 |

0.93 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

| Kaolin clay [41] |

0.260 |

0.050 |

0.20 |

0.896 |

2.957 |

|

1.5 |

1.17 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

Table 2.

Soil parameters of the proposed model for drained analyses.

Table 2.

Soil parameters of the proposed model for drained analyses.

| Source of Clay |

Basic Parameters |

|

Extra Parameters |

| λ |

κ |

ν |

Mc |

e0 |

|

Ψ |

Ω |

| Shanghai clay [42] |

0.113 |

0.021 |

0.30 |

1.360 |

1.354 |

|

1.4 |

1.1 |

| Fujinomori clay [36] |

0.089 |

0.020 |

0.20 |

1.360 |

1.230 |

|

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).