Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pesticide Classes and Environmental Persistence

| Pesticide class | Representative compounds | Average soil half-life (DT₅₀) | Persistence category | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates | Chlorpyrifos, Parathion |

30-60 days | Moderate | [27,44] |

| Carbamates | Carbofuran, Aldicarb |

10-50 days | Low to Moderate | [23,45] |

| Pyrethroids | Cypermethrin, Permethrin |

30-100 days (up to years in anaerobic conditions) | Moderate to High | [29,30,46] |

| Neonicotinoids | Imidacloprid, Acetamiprid |

40-150 days (dry conditions longer) | Moderate | [31,32,33,47,48] |

| Triazines | Atrazine, Simazine |

60-100 days | Moderate | [34,49] |

| Organochlorines | DDT, Chlordane | 2-15 years | High | [3,12] |

| Others (e.g., Glyphosate) | Glyphosate | 3-5 days (variable) | Low | [35,36] |

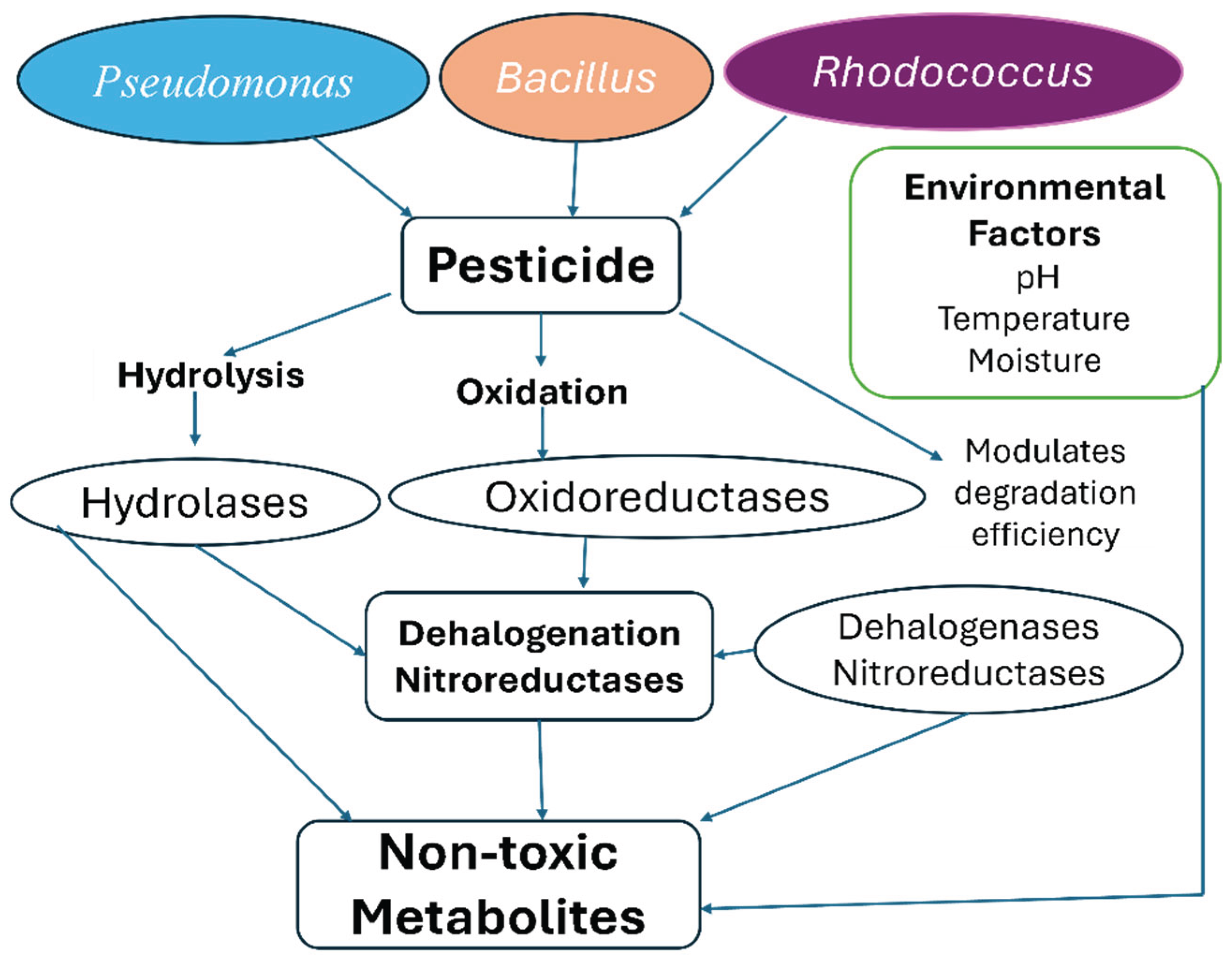

3. Bacterial Taxa Involved in Pesticide Degradation

4. Enzymatic and Genetic Mechanisms of Degradation

| Enzyme class | Pesticide type | Mechanism | Bacterial examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotriesterases / Organophosphorus hydrolases (PTE/OPH) | Organophosphates (e.g., chlorpyrifos, diazinon, methyl parathion) | Hydrolysis of P-O bonds |

Pseudomonas Roseomonas, Sphingobium, Bacillus, Arthrobacter |

[10,78,79,88,89] |

| Carboxylesterases / Esterases | Carbamates, Pyrethroids |

Ester hydrolysis, Ring opening |

Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, Acinetobacter, Stenotrophomonas |

[21,29,46,56] |

| Nitroreductases | Neonicotinoids, Diphenyl ethers, Nitroaromatic |

Nitroreduction, Demethylation, Nitroreduction |

Bacillus, Rhodococcus Arthrobacter, Enterobacter, Klebsiella |

[39,80,81] |

| Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases/ Other Monooxygenases |

Neonicotinoids, Organochlorines, Pyrethroids, Fungicides |

Oxidative degradation (hydroxylation, dealkylation, N-oxidation) |

Sphingomonas, Alcaligenes, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Streptomyces |

[90,91,92,93] |

| Amidases/Hydrolases | Carbamates, Triazines |

Amide bond cleavage |

Arthrobacter, Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Variovorax, Paenarthrobacter |

[23,45,52,94] |

| Oxidases (e.g., Laccases, Peroxidases, Multicopper oxidases) |

Recalcitrant Pesticides, Aromatics, Dyes |

Oxidation of aromatic rings, radical-mediated reactions |

Pseudomonas, Ochrobactrum, Bacillus, Azospirillum, Streptomyces |

[83,84,95,96,97] |

5. Environmental Factors Affecting Degradation

6. Bioremediation Strategies

6.1. Natural Attenuation

| Environmental Factor | Effect on Degradation | Optimal Range | Negative Impact Examples | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Influences sorption and enzyme activity | Neutral (6-7) | Acidic soils slow pyrethroid breakdown | [35,49,98] |

| Temperature | Affects enzyme kinetics and microbial metabolism | 25-30°C | Low temps (<10°C) reduce rates | [99,102] |

| Moisture | Enhances microbial growth and substrate diffusion | Field capacity (60-80%) | Drought inhibits activity | [82,76] |

| Organic Matter | Increases sequestration but aids adaptation | High content | Low OM reduces bioavailability | [37,98,101] |

| Aeration/Oxygen | Promotes aerobic degradation | Well-aerated soils | Anaerobic conditions prolong persistence | [29,30,35] |

6.2. Bioaugmentation

6.3. Synthetic Microbial Consortia

6.4. Field-Scale Applications

| Strategy | Description | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitation | Examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Attenuation | Relies on indigenous microbes for passive degradation | Hydrolysis and oxidation by native enzymes | Cost-effective, minimal ecological disruption | Slow rates, incomplete mineralization (varies with soil conditions) | Chlorpyrifos and endosulfan attenuation | [13,108,110,111,112] |

| Bioaugmentation | Introduces specific degraders to accelerate processes, using isolates or carrier materials | Esterase-mediated hydrolysis, nitroreduction | Targets specific contaminants, accelerates degradation | Strain survival, competition with natives, cost of inoculation | Bacillus sp. for chlorpyrifos, Rhodococcus pyridinivorans Y6 for pyrethroids | [57,60,114,115] |

| Synthetic Microbial Consortia | Engineered combinations of strains for synergistic degradation, regulated by quorum sensing | Complementary enzymatic pathways (e.g., esterases, oxidases) via quorum sensing | Synergistic efficiency, adaptable to multi-contaminants | Complex engineering, regulatory hurdles (e.g., safety assessments) | Pseudomonas and Bacillus consortia | [15,77,82,117,118,122,123] |

| Field-Scale Applications | Large-scale deployment of consortia and amendments | Enhanced degradation with biochar and consortia | Scalable, high efficiency | Requires monitoring, site-specific | Biobeds for chlorpyrifos; biochar for atrazine & Chlorpyrifos |

[147,132,148] |

7. Methodology

8. Advances in Omics Technologies and Synthetic Biology

9. Regulatory and Practical Considerations

10. Implications for Sustainable Agriculture

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated Protein 9 |

| DDT: | Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane |

| DT50: | Disappearance Time 50, or half-life |

| FAO: | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GMOs: | Genetically Modified Organisms |

| AI: | Artificial Intelligence |

| SDGs: | Sustainable Development Goals |

| PTE/OPH | Phosphotriesterases/Organophosphorus Hydrolases |

| UNEP: | United Nations Environment Programme |

References

- Aktar, W.; Sengupta, D.; Chowdhury, A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2009, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO, “The State of Food and Agriculture 2023: Revealing the true cost of food to transform agrifood systems,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc7724en.

- Huynh, T.; Laidlaw, W.; Singh, B.; Gregory, D.; Baker, A. Effects of phytoextraction on heavy metal concentrations and pH of pore-water of biosolids determined using an in situ sampling technique. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; et al. Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Batchelor, W.D.; Wu, D.; Zhen, X.; Ju, H. Future climate change impacts on wheat grain yield and protein in the North China Region. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 902, 166147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P.; Maipas, S.; Kotampasi, C.; Stamatis, P.; Hens, L. Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Front. Public Heal. 2016, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, C.; Sirohi, U.; Srivastav, A.L.; Rani, L. Strategies for mitigation of pesticides from the environment through alternative approaches: A review of recent developments and future prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, W.; Hassine, A.I.H.; Bouaziz, A.; Bartegi, A.; Thomas, O.; Roig, B. Effect of Endocrine Disruptor Pesticides: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2011, 8, 2265–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Rajamohan, N.; Saravanan, R. Microbial degradation of recalcitrant pesticides: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3209–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Walker, A. Microbial degradation of organophosphorus compounds. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 428–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, N. V. Kumar, N. Sharma, and S. Kumar, “Advances in microbial bioremediation of pesticides: A global perspective,” Biodegradation, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 1–25, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Ortiz-Hernández, E. M. L. Ortiz-Hernández, E. Sánchez-Salinas, E. Dantán-González, and M. L. Castrejón-Godínez, “Pesticide biodegradation: Mechanisms, genetics and strategies to enhance the process BT - Biodegradation - Life of Science,” 2013, pp. 251–287. [CrossRef]

- Morillo, E.; Villaverde, J. Advanced technologies for the remediation of pesticide-contaminated soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 586, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, Y. W. Zhang, Y. Huang, P. Bhatt, and S. Chen, “Omics-driven advances in microbial bioremediation of pesticides,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., vol. 81, p. 102932, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rayu, S.; Nielsen, U.N.; Nazaries, L.; Singh, B.K. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Novel Chlorpyrifos and 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol-degrading Bacteria from Sugarcane Farm Soils. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Chennappa, N. G. Chennappa, N. Udaykumar, M. Vidya, H. Nagaraja, Y. S. Amaresh, and M. Y. Sreenivasa, “Azotobacter—A Natural Resource for Bioremediation of Toxic Pesticides in Soil Ecosystems,” New Futur. Dev. Microb. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Microb. Biotechnol. Agro-environmental Sustain., pp. 267–279, Jan. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Arbeli and C. L. Fuentes, “Microbial Degradation of Pesticides in Tropical Soils,” pp. 251–274, 2010. [CrossRef]

- UNEP, “Global Chemicals Outlook II: From Legacies to Innovative Solutions,” United Nations Environment Programme, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.unep.

- S. Rayu, U. N. Nielsen, L. Nazaries, and B. K. Singh, “Isolation and characterization of novel microbes for bioremediation of pesticides,” Environ. Chem., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 387–400, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Arias, L.A.; Garzón, A.; Ayarza, A.; Aux, S.; Bojacá, C.R. Environmental fate of pesticides in open field and greenhouse tomato production regions from Colombia. Environ. Adv. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S. Characterization of the role of esterases in the biodegradation of organophosphate, carbamate, and pyrethroid pesticides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, K.; Canonica, S.; Wackett, L.P.; Elsner, M. Evaluating Pesticide Degradation in the Environment: Blind Spots and Emerging Opportunities. Science 2013, 341, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, H.; Kaur, S.; Phale, P.S. Conserved Metabolic and Evolutionary Themes in Microbial Degradation of Carbamate Pesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdeni, N.L.; Adeniji, A.O.; Okoh, A.I.; Okoh, O.O. Analytical Evaluation of Carbamate and Organophosphate Pesticides in Human and Environmental Matrices: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 26. R. Arya, R. 26. R. Arya, R. Kumar, N. K. Mishra, and A. K. Sharma, “Microbial Flora and Biodegradation of Pesticides: Trends, Scope, and Relevance,” Adv. Environ. Biotechnol., pp. 20 May; 17. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaushik, G.; Dar, M.A.; Nimesh, S.; López-Chuken, U.J.; Villarreal-Chiu, J.F. Microbial Degradation of Organophosphate Pesticides: A Review. Pedosphere 2018, 28, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Gautam et al., “The function of microbial enzymes in breaking down soil contaminated with pesticides: a review,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 9, no. 5, p. 101883, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cycoń, M.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Pyrethroid-Degrading Microorganisms and Their Potential for the Bioremediation of Contaminated Soils: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amweg, E.L.; Weston, D.P.; Ureda, N.M. Use and toxicity of pyrethroid pesticides in the Central Valley, California, USA. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005, 24, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonmatin, J.-M.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Krupke, C.; Liess, M.; Long, E.; Marzaro, M.; Mitchell, E.A.D.; et al. Environmental fate and exposure; neonicotinoids and fipronil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon-Delso, N.; Amaralrogers, V.; Belzunces, L.P.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Chagnon, M.; Downs, C.; Furlan, L.; Gibbons, D.W.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; et al. Systemic insecticides (neonicotinoids and fipronil): trends, uses, mode of action and metabolites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D. REVIEW: An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graymore, M.; Stagnitti, F.; Allinson, G. Impacts of atrazine in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2001, 26, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borggaard, O.K.; Gimsing, A.L. Fate of glyphosate in soil and the possibility of leaching to ground and surface waters: a review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 64, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.; Powles, S.B. Glyphosate: a once-in-a-century herbicide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G.; Atreya, K.; Scheepers, P.T.; Geissen, V. Concentration and distribution of pesticide residues in soil: Non-dietary human health risk assessment. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Insights Into the Microbial Degradation and Biochemical Mechanisms of Neonicotinoids. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Insights Into the Microbial Degradation and Biochemical Mechanisms of Neonicotinoids. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Katagi et al., “Soil carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation: Role of bioremediation,” African J. Microbiol. Res., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 643–654, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fenet, H.; Beltran, E.; Gadji, B.; Cooper, J.F.; Coste, C.M. Fate of a Phenylpyrazole in Vegetation and Soil under Tropical Field Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapute, P.; Kaliwal, B. Biodegradation of propiconazole by newly isolated Burkholderia sp. strain BBK_9. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Zhong, J.; Chen, S.-F.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Guo, P.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, K.; Chen, S. Microbial degradation as a powerful weapon in the removal of sulfonylurea herbicides. Environ. Res. 2023, 235, 116570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. D. Racke, “Environmental fate of chlorpyrifos,” Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., vol. 131, pp. 1–150, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Pang, S.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Z.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Insights into the microbial degradation and biochemical mechanisms of carbamates. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Huang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. New insights into the microbial degradation and catalytic mechanism of synthetic pyrethroids. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. S. Fuentes, A. M. S. Fuentes, A. Alvarez, and J. M. Saez, “Actinobacteria in pesticide bioremediation: A focus on Streptomyces,” Microb. Ecol., vol. 87, no. 1, p. 45, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, G.; Iyapparaja, M. Systematic approaches to machine learning models for predicting pesticide toxicity. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Estévez, M.; López-Periago, E.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Mejuto, J.-C.; García-Río, L. The mobility and degradation of pesticides in soils and the pollution of groundwater resources. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 123, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, R.; Zuo, Z.; Che, Y.; Yu, H.; Song, C.; Yang, C. Metabolic Engineering of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for Complete Mineralization of Methyl Parathion and γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Gong, T.; Che, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, P.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, C.; Song, C.; Yang, C. Engineering Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for simultaneous degradation of organophosphates and pyrethroids and its application in bioremediation of soil. Biodegradation 2015, 26, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, L.C.; Rosendahl, C.; Johnson, G.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Wackett, L.P. Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 Metabolizes Diverse s -Triazine Ring Compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5973–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Kawashima, F.; Takagi, K.; Kataoka, R.; Kotake, M.; Kiyota, H.; Yamazaki, K.; Sakakibara, F.; Okada, S. Isolation of endosulfan sulfate-degrading Rhodococcus koreensis strain S1-1 from endosulfan contaminated soil and identification of a novel metabolite, endosulfan diol monosulfate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, K.; Agrawal, N.; Farooq, M.; Misra, R.; Hans, R. Endosulfan degradation by a Rhodococcus strain isolated from earthworm gut. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 64, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbaum, R.T.; Allan, D.L.; Wackett, L.P. Isolation and Characterization of a Pseudomonas sp. That Mineralizes the s-Triazine Herbicide Atrazine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1451–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Hu, K.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, A.; Yao, K.; Liu, S. Current insights into the microbial degradation for pyrethroids: strain safety, biochemical pathway, and genetic engineering. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, S.-F.; Chen, W.-J.; Zhu, X.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Efficient biodegradation of multiple pyrethroid pesticides by Rhodococcus pyridinivorans strain Y6 and its degradation mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Cai, B. Isolation and characterization of atrazine-degrading Arthrobacter sp. AD26 and use of this strain in bioremediation of contaminated soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 1226–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cheng, M.; Lu, L.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X. A nitroreductase DnrA catalyzes the biotransformation of several diphenyl ether herbicides in Bacillus sp. Za. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5269–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Ahmad, M.; Kanwal, A.; Butt, Z.A.; Khan, Q.F.; Raza, S.A.; Qayyum, H.; Wahid, A. Biodegradation of chlorpyrifos using isolates from contaminated agricultural soil, its kinetic studies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Lu, Q.; Yi, X.; Zhong, G.; Liu, J. Synergistic Degradation of Pyrethroids by the Quorum Sensing-Regulated Carboxylesterase of Bacillus subtilis BSF01. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, V.P.; Sawant, I.S.; Banerjee, K.; Wadkar, P.N.; Sawant, S.D. Enhanced Dissipation of Triazole and Multiclass Pesticide Residues on Grapes after Foliar Application of Grapevine-Associated Bacillus Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 10736–10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, H.W.; Bhatt, P. Microbial adaptation and impact into the pesticide’s degradation. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. M. N. Bilal, M.; Ashraf, S.S. H. M. N. Bilal, M.; Ashraf, S.S.; Iqbal, “Laccase-Mediated Bioremediation of Dye-Based Hazardous Pollutants,” in Methods for Bioremediation of Water and Wastewater Pollution, A. M. Inamuddin; Ahamed, M.I.; Lichtfouse, E.; Asiri, Ed., Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Jia, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, L.; Wu, Y.; Ruan, H.; Chen, J. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes loaded with IR780 conjugated MoS2-nanosheet for dual-mode photodynamic/photothermal inactivation of drug-resistant bacteria. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalle, S.; Bhende, R.S.; Bokade, P.; Bajaj, A.; Dafale, N.A. Emerging microbial remediation methods for rejuvenation of pesticide-contaminated sites. Total. Environ. Microbiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, N.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, S. Bioremediation using Novosphingobium strain DY4 for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-contaminated soil and impact on microbial community structure. Biodegradation 2015, 26, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. N. Fatemeh Amani Ali akabar safari sinegani, Firouz ibrahami, “Biodegradation of Chlorpyrifos and Diazinon Organophosphates by Two Bacteria Isolated from Contaminated Agricultural Soils,” Biol. J. Microorg., vol. 7, no. 28, pp. 27–39, 2017.

- Ishag, A.E.S.A.; Abdelbagi, A.O.; Hammad, A.M.A.; Elsheikh, E.A.E.; Elsaid, O.E.; Hur, J.-H. Biodegradation of endosulfan and pendimethalin by three strains of bacteria isolated from pesticides-polluted soils in the Sudan. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2017, 60, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, N.M.E.J.; Ryngaert, A.; Bastiaens, L.; Verstraete, W.; Top, E.M.; Springael, D. Occurrence and Phylogenetic Diversity ofSphingomonasStrains in Soils Contaminated with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1944–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, J.; Hu, H.; Xu, P. A newly isolated strain of Stenotrophomonas sp. hydrolyzes acetamiprid, a synthetic insecticide. Process. Biochem. 2012, 47, 1820–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycoń, M.; Mrozik, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Bioaugmentation as a strategy for the remediation of pesticide-polluted soil: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 172, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Ganai, B.A. Deciphering the recent trends in pesticide bioremediation using genome editing and multi-omics approaches: a review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, G.P.; Ashokrao, D.M.; Arun, S.K. Microbial degradation of pesticide: A review. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 11, 992–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Gutiérrez, V.; Fuller, E.; Thomas, J.C.; Sinclair, C.J.; Johnson, S.; Helgason, T.; Moir, J.W. Genomic basis for pesticide degradation revealed by selection, isolation and characterisation of a library of metaldehyde-degrading strains from soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechesne, A.; Badawi, N.; Aamand, J.; Smets, B.F. Fine scale spatial variability of microbial pesticide degradation in soil: scales, controlling factors, and implications. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S. Characterization of the role of esterases in the biodegradation of organophosphate, carbamate, and pyrethroid pesticides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritis, A.; Bajpai, P. Continuous ethanol production from Jerusalem artichoke tubers. I. Use of free cells of Kluyveromyces marxianus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1982, 24, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashirova, T.; Salah-Tazdaït, R.; Tazdaït, D.; Masson, P. Applications of Microbial Organophosphate-Degrading Enzymes to Detoxification of Organophosphorous Compounds for Medical Countermeasures against Poisoning and Environmental Remediation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Dubey, S.K. Biodegradation of Neonicotinoids: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2023, 9, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S.C.; Miller, G.J.; Bornadel, A.; Dominguez, B. Realizing the Continuous Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Anilines Using an Immobilized Nitroreductase. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 8556–8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S. Development and Application of CRISPR/Cas in Microbial Biotechnology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Pandey, G.; Hartley, C.J.; Jackson, C.J.; Cheesman, M.J.; Taylor, M.C.; Pandey, R.; Khurana, J.L.; Teese, M.; Coppin, C.W.; et al. The enzymatic basis for pesticide bioremediation. Indian J. Microbiol. 2008, 48, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.; Barceló, D. Persistence of pesticides-based contaminants in the environment and their effective degradation using laccase-assisted biocatalytic systems. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 695, 133896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Jain, J. R. Jain, J. Saxena, and V. Sharma, “Synthetic biology approaches for enhancing microbial pesticide degradation,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 104, no. 11, pp. 4673–4685, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, J.S. Microbial-assisted remediation approach for neonicotinoids from polluted environment. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian-Dehkordi, J.; Rahimi, S.; Golzar-Ahmadi, M.; Singh, A.; Lopez, J.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Mijakovic, I. Synthetic biology tools for environmental protection. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 68, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, M.-Q.; Gao, J.-J.; Li, Z.-J.; Tian, Y.-S.; Peng, R.-H.; Yao, Q.-H. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia coli for Methyl Parathion Degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 679126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathi, A.; Pandey, A.; Sukumaran, R.K. Rapid degradation of the organophosphate pesticide – Chlorpyrifos by a novel strain of Pseudomonas nitroreducens AR-3. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-J.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Q.; Chen, S.-F.; Huang, Y.; Bhatt, K.; Liao, L.; Zhou, X. Pseudomonas aeruginosa based concurrent degradation of beta-cypermethrin and metabolite 3-phenoxybenzaldehyde, and its bioremediation efficacy in contaminated soils. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Guo, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, J. Microbial degradation mechanisms of the neonicotinoids acetamiprid and flonicamid and the associated toxicity assessments. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1500401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, P.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J. Neonicotinoid Insecticide-Degrading Bacteria and Their Application Potential in Contaminated Agricultural Soil Remediation. Agrochemicals 2024, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Tu, C.; Long, T.; Bu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jeyakumar, P.; Jiang, J.; Deng, S. Remediation technologies for neonicotinoids in contaminated environments: Current state and future prospects. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Lal, S.; Soni, S.K.; Maurya, S.K.; Shukla, P.K.; Chaudhary, P.; Bhattacherjee, A.K.; Garg, N. Mechanism and kinetics of chlorpyrifos co-metabolism by using environment restoring microbes isolated from rhizosphere of horticultural crops under subtropics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 891870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithyanathan, V.K.; Vaidyanathan, V.K.; Cabana, H. Laccase-Driven Transformation of High Priority Pesticides Without Redox Mediators: Towards Bioremediation of Contaminated Wastewaters. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 770435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Lu, Q.; Zhong, G.; Hu, M.; Yi, X. Biodegradation of Pyrethroids by a Hydrolyzing Carboxylesterase EstA from Bacillus cereus BCC01. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.S.; Jha, B. Pilot scale production of extracellular thermo-alkali stable laccase from Pseudomonas sp. S2 using agro waste and its application in organophosphorous pesticides degradation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 93, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Natasha; Naeem, M. A.; Niazi, N.K. A critical review of different factors governing the fate of pesticides in soil under biochar application. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 711, 134645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A.; Gosal, S.K. Effect of pesticide application on soil microorganisms. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2011, 57, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Gamage, L.K.H.; Thapa, V.R. Impact of Drought on Soil Microbial Communities. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. ; Anshumali Biogeochemical appraisal of carbon fractions and carbon stock in riparian soils of the Ganga River basin. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcour, I.; Spanoghe, P.; Uyttendaele, M. Literature review: Impact of climate change on pesticide use. Food Res. Int. 2015, 68, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, I.G.; Țopa, D.; Puiu, I.; Jităreanu, G. Biochar a Promising Strategy for Pesticide-Contaminated Soils. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, S.Y.A. Harnessing bacterial consortia for effective bioremediation: targeted removal of heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and persistent pollutants. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Sati, D.; Bhatt, P.; Samant, M. Microbial Interventions in Bioremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminants in Agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 824084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S.; Kumar, G.; Rene, E.R. Developments in biochar application for pesticide remediation: Current knowledge and future research directions. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P.; Bhatt, K.; Sharma, A.; Zhang, W.; Mishra, S.; Chen, S. Biotechnological basis of microbial consortia for the removal of pesticides from the environment. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. K. Jayasekara and R. R. Ratnayake, “The bioremediation of agricultural soils polluted with pesticides,” Microb. Syntrophy-mediated Eco-enterprising, pp. 15–39, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Thirumalesh, B.V.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Tripathi, M. Recent Strategies for Bioremediation of Emerging Pollutants: A Review for a Green and Sustainable Environment. Toxics 2022, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, C.M.; Chiampo, F. Bioremediation of Agricultural Soils Polluted with Pesticides: A Review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, S.; Zubillaga, M.; Montserrat, J.M. Natural attenuation and bioremediation of chlorpyrifos and endosulfan in periurban horticultural soils of Buenos Aires (Argentina) using microcosms assays. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 169, 104192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.R.M.; Cruz, V.H.; de Menezes, A.B.; Gadanhoto, B.P.; Moreira, B.R.d.A.; Mendes, C.R.; Mazzeo, D.E.C.; Dilarri, G.; Montagnolli, R.N. Microbial bioremediation of pesticides in agricultural soils: an integrative review on natural attenuation, bioaugmentation and biostimulation. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology 2022, 21, 851–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Gao, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, B. The boom era of emerging contaminants: A review of remediating agricultural soils by biochar. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 931, 172899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycoń, M.; Mrozik, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Bioaugmentation as a strategy for the remediation of pesticide-polluted soil: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 172, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.R.; Delabona, P.d.S. Strategies for bioremediation of pesticides: challenges and perspectives of the Brazilian scenario for global application – A review. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeeq, H.; Afsheen, N.; Rafique, S.; Arshad, A.; Intisar, M.; Hussain, A.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M. Genetically engineered microorganisms for environmental remediation. Chemosphere 2022, 310, 136751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villaverde, J.; Rubio-Bellido, M.; Lara-Moreno, A.; Merchan, F.; Morillo, E. Combined use of microbial consortia isolated from different agricultural soils and cyclodextrin as a bioremediation technique for herbicide contaminated soils. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Xu, M.; Ahamad, L.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, G.; Adeleke, B.S.; Verma, K.K.; Hu, D.-M.; Širić, I.; Kumar, P.; et al. Application of Synthetic Consortia for Improvement of Soil Fertility, Pollution Remediation, and Agricultural Productivity: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yan, W.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Construction of microbial consortia for microbial degradation of complex compounds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1051233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S. Development and Application of CRISPR/Cas in Microbial Biotechnology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.J.; Villa-Gomez, D.; Brown, R.; Clarke, W.; Schenk, P.M. A synthetic biology approach for the treatment of pollutants with microalgae. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1379301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Chen, K.; Cao, W.; Meng, L.; Yang, B.; Xu, M.; Xing, Y.; Li, P.; Freilich, S.; Chen, C.; et al. Engineering natural microbiomes toward enhanced bioremediation by microbiome modeling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Khan, M.S.; Singh, U.B. Pesticide-tolerant microbial consortia: Potential candidates for remediation/clean-up of pesticide-contaminated agricultural soil. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.A.; Dubey, A.; Raj, A.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, N.; Yadav, S. Emerging frontiers in microbe-mediated pesticide remediation: Unveiling role of omics and In silico approaches in engineered environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, L.; Yao, W.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, P. Genetic engineering of Pseudomonas chlororaphis Lzh-T5 to enhance production of trans-2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, C. Exploiting Quorum Sensing Interfering Strategies in Gram-Negative Bacteria for the Enhancement of Environmental Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussali-Galante, P.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Díaz-Soto, J.A.; Vargas-Orozco, Á.P.; Quiroz-Medina, H.M.; Tovar-Sánchez, E.; Rodríguez, A. Biobeds, a Microbial-Based Remediation System for the Effective Treatment of Pesticide Residues in Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.R.; Delabona, P.d.S. Strategies for bioremediation of pesticides: challenges and perspectives of the Brazilian scenario for global application – A review. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.d.P.; Torstensson, L.; Stenström, J. Biobeds for Environmental Protection from Pesticide Use—A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6206–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogg, P.; Boxall, A.B.; Walker, A.; A Jukes, A. Pesticide degradation in a ‘biobed’ composting substrate. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spliid, N.H.; Helweg, A.; Heinrichson, K. Leaching and degradation of 21 pesticides in a full-scale model biobed. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortella, G.; Rubilar, O.; Castillo, M.; Cea, M.; Mella-Herrera, R.; Diez, M. Chlorpyrifos degradation in a biomixture of biobed at different maturity stages. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.J.; Fitt, P.; Hiscock, K.M.; Lovett, A.A.; Gumm, L.; Dugdale, S.J.; Rambohul, J.; Williamson, A.; Noble, L.; Beamish, J.; et al. Assessing the effectiveness of a three-stage on-farm biobed in treating pesticide contaminated wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.d.A.; Gebler, L.; Niemeyer, J.C.; Itako, A.T. Destination of pesticide residues on biobeds: State of the art and future perspectives in Latin America. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Castillo, M.D.P.; Monaci, E.; Vischetti, C. Adaptation of the Biobed Composition for Chlorpyrifos Degradation to Southern Europe Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 55, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortella, G.; Rubilar, O.; Castillo, M.; Cea, M.; Mella-Herrera, R.; Diez, M. Chlorpyrifos degradation in a biomixture of biobed at different maturity stages. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yin, H.; Wei, X.; Dang, Z. Functional bacterial consortium responses to biochar and implications for BDE-47 transformation: Performance, metabolism, community assembly and microbial interaction. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sarkar, B.; Aralappanavar, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Basak, B.; Srivastava, P.; Marchut-Mikołajczyk, O.; Bhatnagar, A.; Semple, K.T.; Bolan, N. Biochar-microorganism interactions for organic pollutant remediation: Challenges and perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L.; Harindintwali, J.D.; Wang, F.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Chang, S.X.; Fu, Y.; He, C.; Muhoza, B.; Brahushi, F.; Bolan, N.; et al. Integrating Biochar, Bacteria, and Plants for Sustainable Remediation of Soils Contaminated with Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16546–16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameen, M.Z.; Naqvi, S.R.; Juchelková, D.; Khan, M.N.A. Harnessing the power of functionalized biochar: progress, challenges, and future perspectives in energy, water treatment, and environmental sustainability. Biochar 2024, 6, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.d.A.; Itako, A.T.; Gebler, L.; Júnior, J.B.T.; Pizzutti, I.R.; Fontana, M.E.; Janisch, B.D.; Niemeyer, J.C. Pine Litter and Vermicompost as Alternative Substrates for Biobeds: Efficiency in Pesticide Degradation. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodríguez, V.I.; Baltierra-Trejo, E.; Gómez-Cruz, R.; Adams, R.H. Microbial growth in biobeds for treatment of residual pesticide in banana plantations. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Xu, X.; Dang, Y.; Kong, A.; Wu, Y.; Liang, P.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Xu, P.; Yang, C. An engineered Pseudomonas putida can simultaneously degrade organophosphates, pyrethroids and carbamates. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 628-629, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Gong, T.; Che, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, P.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, C.; Song, C.; Yang, C. Engineering Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for simultaneous degradation of organophosphates and pyrethroids and its application in bioremediation of soil. Biodegradation 2015, 26, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Su, Z.; Ren, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Guo, X.; Liu, L. Combined Use of Biochar and Microbial Agents Can Promote Lignocellulosic Degradation Microbial Community Optimization during Composting of Submerged Plants. Fermentation 2024, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; He, L.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gustave, W.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Aquatic Systems: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Castillo, M.D.P.; Monaci, E.; Vischetti, C. Adaptation of the Biobed Composition for Chlorpyrifos Degradation to Southern Europe Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 55, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Yadav, R.; Pandey, V.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.; Shanker, K.; Khare, P. Effect of biochar on soil microbial community, dissipation and uptake of chlorpyrifos and atrazine. Biochar 2024, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.S.; Geed, S.; Vikrant, K.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, K.-H.; Kailasa, S.K.; Vithanage, M.; Chaturvedi, P.; Rai, B.N.; Singh, R.S. Progress in bioremediation of pesticide residues in the environment. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 26, 200446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, S.P.; Iqbal, H.M.; Tong, Y.W. Omics approaches in bioremediation of environmental contaminants: An integrated approach for environmental safety and sustainability. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Shukla, P. Alternative Strategies for Microbial Remediation of Pollutants via Synthetic Biology. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, X.K.; Hadibarata, T.; Kristanti, R.A.; Jusoh, M.N.H.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y. The function of microbial enzymes in breaking down soil contaminated with pesticides: a review. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, M.; Scott-Boyer, M.-P.; Bodein, A.; Périn, O.; Droit, A. Integration strategies of multi-omics data for machine learning analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3735–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, S.; Nathan, V.K.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Awasthi, M.K.; Pandey, A. Bioengineered microbes for soil health restoration: present status and future. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 12839–12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylott, E.L.; Bruce, N.C. How synthetic biology can help bioremediation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 58, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Jing, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Long-term effect of epigenetic modification in plant–microbe interactions: modification of DNA methylation induced by plant growth-promoting bacteria mediates promotion process. Microbiome 2022, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lensch, A.; Lindfors, H.A.; Duwenig, E.; Fleischmann, T.; Hjort, C.; Kärenlampi, S.O.; McMurtry, L.; Melton, E.-D.; Andersen, M.R.; Skinner, R.; et al. Safety aspects of microorganisms deliberately released into the environment. EFB Bioeconomy J. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. M. Kumar, C. N. M. Kumar, C. Muthukumaran, G. Sharmila, and B. Gurunathan, “Genetically Modified Organisms and Its Impact on the Enhancement of Bioremediation,” Energy, Environ. Sustain., pp. 53–76, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M. Microbial bioremediation as a robust process to mitigate pollutants of environmental concern. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, R.; Cumsille, A.; Piña-Gangas, P.; Rojas, C.; Arancibia, A.; Donghi, S.; Stuardo, C.; Cabrera, P.; Arancibia, G.; Cárdenas, F.; et al. Economic Evaluation of Bioremediation of Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Urban Soils in Chile. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’bRien, R.M.; Phelan, T.J.; Smith, N.M.; Smits, K.M. Remediation in developing countries: A review of previously implemented projects and analysis of stakeholder participation efforts. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 51, 1259–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Giri, J. P. N. K. Giri, J. P. N. Rai, and S. Mishra, “Microbial degradation of pesticides: Mechanisms and pathways,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 193, no. 5, p. 312, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fantke, P. Toward harmonizing global pesticide regulations for surface freshwaters in support of protecting human health. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael-Igolima, U.; Abbey, S.J.; Ifelebuegu, A.O. A systematic review on the effectiveness of remediation methods for oil contaminated soils. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, M. Phour, R. Kumar, and S. S. Sindhu, “Bioremediation of Pesticides: An Eco-Friendly Approach for Environment Sustainability,” Microorg. Sustain., vol. 25, pp. 23–84, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Bharucha, Z.P. Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1571–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, K.; Rahman, N.S.N.A. The Microbial Connection to Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2023, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. P. Choudhury, S. P. P. Choudhury, S. Saha, S. Ray, and R. Banerjee, “Environmental impact of pesticides and their mitigation strategies,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 6001–6018, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.M.; Verma, V.K.; Rawat, B.S.; Kaur, B.; Babu, N.; Sharma, A.; Dewali, S.; Yadav, M.; Kumari, R.; Singh, S.; et al. Current status of pesticide effects on environment, human health and it’s eco-friendly management as bioremediation: A comprehensive review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 962619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburn, E.D.; Yang, G.; Rillig, M.C.; Strickland, M.S. Evaluating the role of bacterial diversity in supporting soil ecosystem functions under anthropogenic stress. ISME Commun. 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial genus/Species | Pesticides Degraded | Mechanism/Notes | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas | Organophosphates, Pyrethroids, DDT, Phenolics |

Hydrolysis, Oxidation, genetically modified for phenolics; consortia synergy |

[10,50,51,52] |

| Rhodococcus | Endosulfan, Triazines, Chlorpyrifos |

Oxidative enzymes, Monooxygenases Ring Cleavage, Metabolite Formation |

[53,54,56,57] |

| Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 | Atrazine, S-Triazines |

Specialized hydrolytic pathways, Dechlorination |

[52,55,58] |

| Bacillus | Pyrethroids, Diphenyl Ethers, Carbamates |

Esterase Activity, Nitroreduction; ~85% triazoles; consortia enhance rates |

[57,59,60,61,62] |

| Burkholderia | Parathion, Carbofuran, Various Organochlorines |

Hydrolases, Oxidases, Broad-Spectrum Degradation; cometabolism with plants |

[9,11,63,64] |

| Flavobacterium | Organophosphates | Hydrolysis | [9,10,11] |

| Klebsiella | Neonicotinoids, Chlorpyrifos | Esterases | [39,65,66] |

| Novosphingobium | PAHs, Sulfonylureas, Neonicotinoids | Dioxygenases, Hydrolysis | [67] |

| Acinetobacter | Neonicotinoids, Diazinon, Organophosphates | Esterases, Hydrolysis; up to 80% diazinon removal in lab settings | [39,65,68] |

| Streptomyces | DDT,Endosulfan, Diflufenican Carbamates, Organophosphates |

Esterases, Cometablolic processes Actinobacterial Degradation |

[39,47,69] |

| Sphingomonas | Neonicotinoids, Sufonylureas | Oxidases, Hydrolysis, genetically modified for carbamates/organophosphates; biofilm enhances stability | [28,70] |

| Stenotrophomonas | Neonicotinoids, Sufonylureas | Hydrolysis, Cometabolism | [43,71] |

| Alcaligenes | Organochlorines | Reductive, Dechlorination | [72] |

| Achromobacter | Triazines | Hydrolysis, Ring Cleavage | [29,73] |

| Paracoccus | Pyrethroids | Ester Hydrolysis | [43,74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).