1. Introduction

Soil is a fundamental component of terrestrial ecosystems, supporting a wide array of ecological functions essential for environmental stability and human well-being [

1]. It acts not only as a medium for plant growth and food production but also as a dynamic interface for nutrient cycling, water regulation, carbon sequestration, and pollutant filtration. Central to these processes are diverse and metabolically active microbial communities that inhabit soil matrices, and these microorganisms play indispensable roles in maintaining soil structure, fertility, and resilience by driving fundamental biogeochemical cycles [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, microbial diversity and functional capacity are central to soil health and environmental sustainability [

5,

6].

One of the most pressing threats to soil ecosystems is contamination with organic and inorganic pollutants. The intensification of anthropogenic activities like industrial operations has led to the widespread accumulation of organic pollutants in soils, particularly in regions with a legacy of intensive industrial activity. This contamination poses significant threats to microbial diversity, disrupts ecological processes, and undermines the long-term sustainability of soil ecosystems[

7,

8]. In China, the transition toward greener industries and the ongoing restructuring of heavily polluting sectors have resulted in the decommissioning and relocation of numerous high-emission chemical and pharmaceutical enterprises [

9,

10]. While this shift represents a positive step toward environmental protection, it has also left behind a legacy of contaminated soils at former industrial sites. In such settings, microbial communities play a critical role in natural attenuation, the self-purifying capacity of soils through intrinsic biological, chemical, and physical processes. Monitored natural attenuation (MNA) has emerged as a promising alternative for managing such sites. MNA relies on natural physical, chemical, and biological processes, that are primarily driven by indigenous microbial activity, to degrade, transform, or stabilize contaminants in situ [

11,

12]. Due to its low cost, minimal environmental disturbance, and compatibility with long-term risk management strategies, leveraging microbial communities for in situ bioremediation has garnered increasing attention in environmental management and ecological engineering [

13].

Despite growing interest, our understanding of the ecological dynamics underpinning microbial-mediated pollutant degradation remains incomplete. In particular, the relationships among contaminant types, soil physicochemical properties, and the composition and functionality of indigenous microbial communities under long-term contamination conditions are not well defined [

14,

15]. Questions remain regarding the spatial heterogeneity of microbial responses to contamination gradients, the persistence and activity of key functional guilds (e.g., dechlorinators), and the resilience of microbial networks in degraded environments. These gaps hinder our ability to predict the natural attenuation potential of contaminated sites and to design effective, low-impact remediation strategies.

Specifically, for sites historically contaminated with chlorinated organic compounds, such as dichloromethane (DCM) and 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA), natural attenuation relies heavily on the presence and activity of specialized microbial taxa capable of reductive dechlorination [

16,

17]. However, the abundance, diversity, and metabolic potential of these functional microbial groups are often poorly characterized in situ. Moreover, the interplay between microbial degradation pathways and environmental variables (e.g., pH, redox potential, organic matter content) remains insufficiently understood, limiting the ability to predict attenuation potential and optimize site management strategies [

18].

To address these challenges, the present study focuses on a decommissioned pharmaceutical-chemical site located in northern Jiangsu Province, China. According to a comprehensive site assessment conducted in 2024, the primary soil pollutants are chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons, with concentrations of DCM and 1,2-DCA exceeding the threshold values for Category II land use, as defined by the Chinese Soil Environmental Quality Standard (GB36600-2018) [

19]. Given the lack of immediate redevelopment plans, this site provides a unique opportunity to investigate the natural attenuation potential under minimal human disturbance. This study integrates high-resolution soil physicochemical characterization with microbial community profiling across contamination gradients. Special emphasis is placed on the identification and ecological roles of reductive dechlorinating microbial taxa, aiming to (i) assess the effects of contamination on soil microbial diversity and structure; (ii) evaluate the distribution and activity of key dechlorinating microbial groups; and (iii) explore how soil properties influence microbial-mediated attenuation processes. Our findings will provide mechanistic insights into how organic pollutants shape soil microbial communities and their functional capacities. These results will support the development of science-based strategies for long-term monitoring and management of contaminated sites using MNA approaches.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Description of the Study Site

This study was conducted at a decommissioned pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturing facility located in the northern region of Jiangsu Province, China (34°28'57"N, 119°45'46"E). The facility is situated within a designated chemical industrial park and occupies a total area of approximately 30,077 m². Historical production activities at the site included the synthesis and processing of organic solvents and intermediates, resulting in long-term pollutant accumulation in the surrounding soils. According to a comprehensive soil contamination assessment report conducted in 2024, a total of 93 soil survey points were evaluated. Of these, three locations exceeded the screening thresholds for Class II land use as defined by the Chinese Soil Environmental Quality Standard GB36600-2018 [

19]. The primary pollutants responsible for the exceedance were dichloromethane and 1,2-dichloroethane, with the maximum exceedance factor reaching 82.64 times above the standard screening value. These findings indicate the presence of localized hotspots of severe organic contamination, which may pose ecological and human health risks.

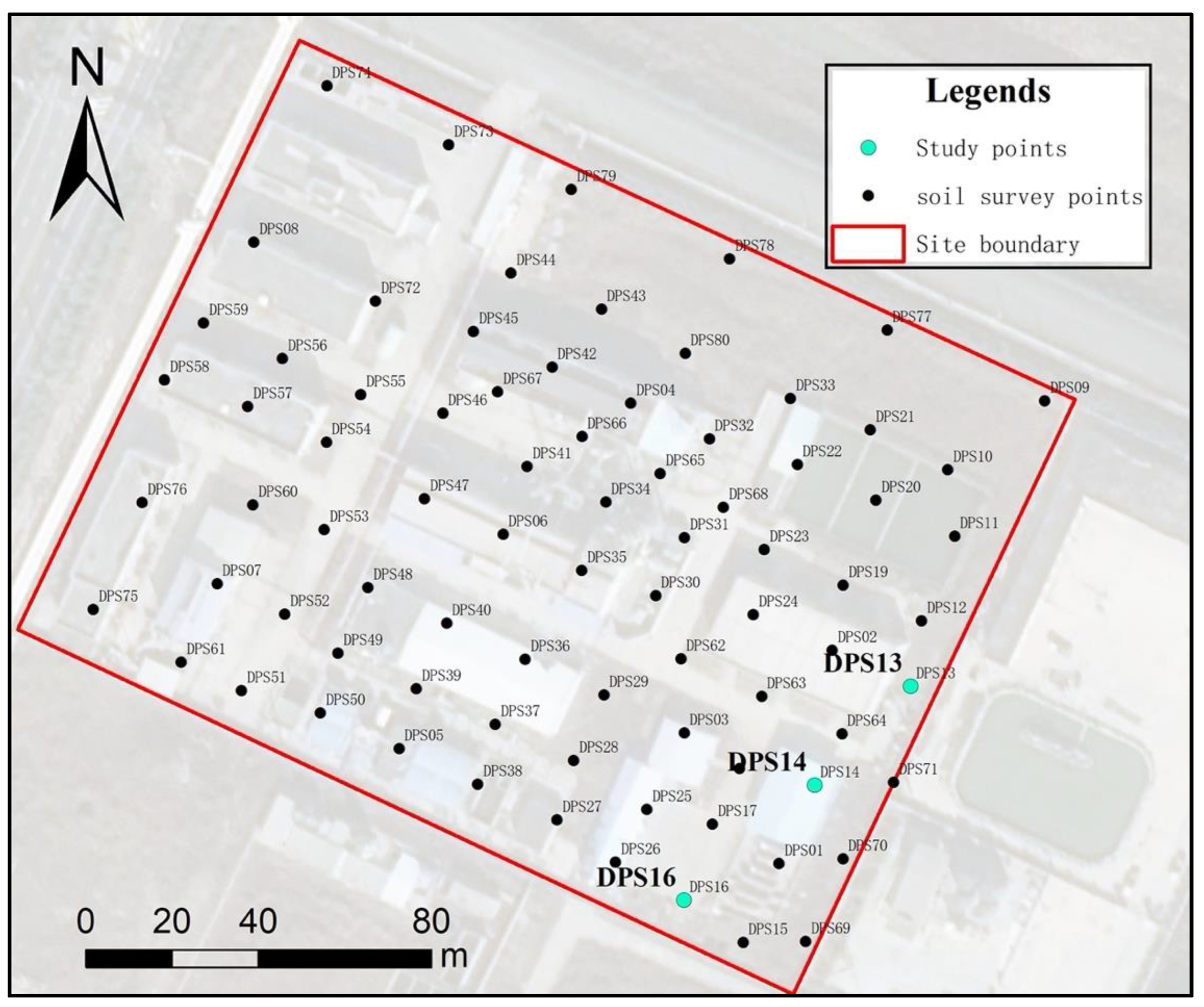

The distribution of sampling points across the site is shown in

Figure 1, covering areas of differing contamination severity and providing the basis for evaluating the physicochemical characteristics, pollutant profiles, and microbial community dynamics under long-term pollution stress.

2.2. Soil Sampling and Pretreatment

Soil sampling was conducted in May 2024, with sampling locations selected based on contamination patterns reported in the 2024 soil pollution assessment of the study site. Three representative sampling sites, DPS13, DPS14, and DPS16, were chosen to represent zones with varying pollutant concentrations. Subsurface soil cores were collected using a Geoprobe® 7822DT direct push drilling rig [

20], which enabled extraction of continuous, undisturbed core samples up to a depth of 3.0 meters. The rig operates through a combination of static pressure and percussion to insert a coring system, with cores preserved in transparent, sealed polycarbonate liners. Upon retrieval, the liners were opened under sterile conditions, and soil subsamples (>5 g) were taken at 0.2 m (vadose zone) and 2.2 m (saturated zone) for microbial DNA analysis. These samples were placed into sterile polyethylene bags and transported to the laboratory under cold conditions using insulated containers with dry ice to preserve microbial integrity.

Additional soil subsamples were collected from 0–0.5 m and 2.0–2.5 m depth intervals for determination of soil physicochemical properties, including pH, soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), and cation exchange capacity (CEC). These samples were stored in 400 mL amber glass bottles and delivered to the laboratory in 4 °C insulated containers to minimize alteration prior to analysis.

2.3. Sample Testing

Soil physicochemical properties were determined according to standard protocols outlined by Lu (1999) [

21]. Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil-to-water slurry using a calibrated pH meter. SMC was determined gravimetrically by drying soils at 105 °C, SOM was measured by potassium dichromate oxidation, and CEC was analyzed using the ammonium acetate method.

Microbial DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of each soil sample using the PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA purity and concentration were assessed via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

PCR amplification of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using primers and protocols described by [

22]. Amplicons were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads) by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.4. Sequence Processing

Raw sequencing data were processed using a quality-controlled bioinformatics pipeline. Reads were demultiplexed and quality-filtered using Trimmomatic, and paired-end reads were merged using FLASH v1.2.7. Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using USEARCH v11.0. Representative OTU sequences were taxonomically classified using the RDP Classifier v2.2 against the SILVA v138 database with a confidence threshold of 0.7. To account for differences in sequencing depth, all samples were rarefied to 48,689 reads per sample prior to downstream analyses. Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA893205.

2.5. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R v4.2.2. Soil physicochemical data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE), and one-way ANOVA was used to evaluate differences between sampling points (P < 0.05). Alpha diversity indices (Chao1 richness and Shannon diversity) were calculated from OTU tables, and pairwise t-tests were applied to compare diversity between soil depths.

Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess relationships between soil physicochemical parameters and both microbial α-diversity and the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria. Significant correlations were reported with corresponding P-values and R² values. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was used to visualize β-diversity, and Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was applied to test group differences in community structure. To explore environmental drivers of microbial community composition, Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was conducted. Differences in dechlorinating bacterial abundance across contamination categories were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

A co-occurrence network was constructed using Spearman correlation coefficients (r ≥ 0.8, P < 0.05) at the genus level. Key dechlorinating taxa (Desulfovibrio, Desulfobulbus, Desulfuromonas, Desulfitobacterium, Desulfomonile, and Dehalobacter) were included as hub nodes. The network was visualized using Gephi v0.10.1, providing insights into potential microbial interactions and functional associations relevant to pollutant degradation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties and Pollutant Distribution

The physicochemical characteristics of soil samples collected from 18 locations across the study site are summarized in

Table 1. Across all sampling points, soil pH values consistently fall within the alkaline range, ranging from 8.55 to 9.19. Notably, the highest pH (9.19) was observed in the surface soil at sampling point 13 (D13S, 0-0.5m), followed by the corresponding deep soil sample (D13D, 2-2.5m) with a pH of 8.91. This localized increase in alkalinity may be attributed to the accumulation of alkaline degradation byproducts resulting from microbial transformation of chlorinated hydrocarbons, particularly 1,2-dichloroethane (DCA), with elevated concentrations in this area. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies, where the microbial reductive dechlorination of CAHs produced alkaline intermediates such as acetate or bicarbonate, contributing to local pH elevation [

17,

23].

Soil moisture content (SMC) generally increases with depth across most sampling locations. This vertical trend may reflect reduced evapotranspiration and enhanced water retention at deeper strata, which can influence microbial activity and pollutant transport dynamics. Higher moisture content in deeper layers can also promote anaerobic conditions favorable for reductive dechlorination processes [

23]. Soil organic matter (SOM) content varied widely across these sites, ranging from 11.55 to 46.35 g/kg. While SOM tended to increase with depth at sampling points 13 (D13) and 14 (D14), the opposite trend was observed at point 16 (D16), where the surface soil exhibited higher SOM content (25.35 g/kg) compared to the deep soil (11.55 g/kg). These contrasting patterns may be influenced by historical waste discharge patterns, organic pollutant deposition, or differential microbial degradation activity at various depths. Elevated SOM in surface soils at D16 may also indicate accumulation of organic residues from pollutant degradation or past anthropogenic inputs [

24]. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) decreased with soil depth in most cases, except at sampling point 16. The divergent trend at D16 may be due to variations in clay mineral composition or the presence of cationic degradation intermediates that enhance exchange sites in deeper soil layers.

Analysis of pollutant concentrations (

Figure 1) revealed that composite contamination by chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons (CAHs: chloroform, chloromethane, chloroethene, dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloroethane), BTEX compounds (toluene, o-xylene), and chlorinated benzenes (CBs: chlorobenzene, 1,2-dichlorobenzene, 1,4-dichlorobenzene) is primarily concentrated at sampling points 13 (D13) and 16 (D16). In contrast, point 14 (D14) exhibited pollutant concentrations below detection limits in both shallow and deep soil layers. This spatial distribution suggests that historical contaminant discharge and operational activities were likely focused near points 13 and 16, resulting in the formation of localized pollution hotspots. The absence of detectable pollutants at D14 indicates spatial heterogeneity in contaminant deposition and possibly more efficient natural attenuation or less exposure to industrial discharge at this location.

These results highlight pronounced spatial variability in both soil physicochemical properties and contaminant distribution across the site. The co-occurrence of high pollutant concentrations with elevated SOM and pH at specific sampling points suggests potential hotspots of microbial transformation activity. Understanding these localized interactions between soil properties and contaminant fate is essential for assessing natural attenuation potential and informing risk-based site management strategies.

3.2. Microbial Community Composition and the Influence of Soil Physicochemical Properties on α-Diversity

To investigate microbial responses to long-term contamination, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing was performed on 18 soil samples collected from different contamination zones and depths. A total of 1,038,598 high-quality sequences were obtained, with an average read length of 376 bp. Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering at 97% sequence similarity yielded 10,890 OTUs, reflecting considerable taxonomic richness across the site.

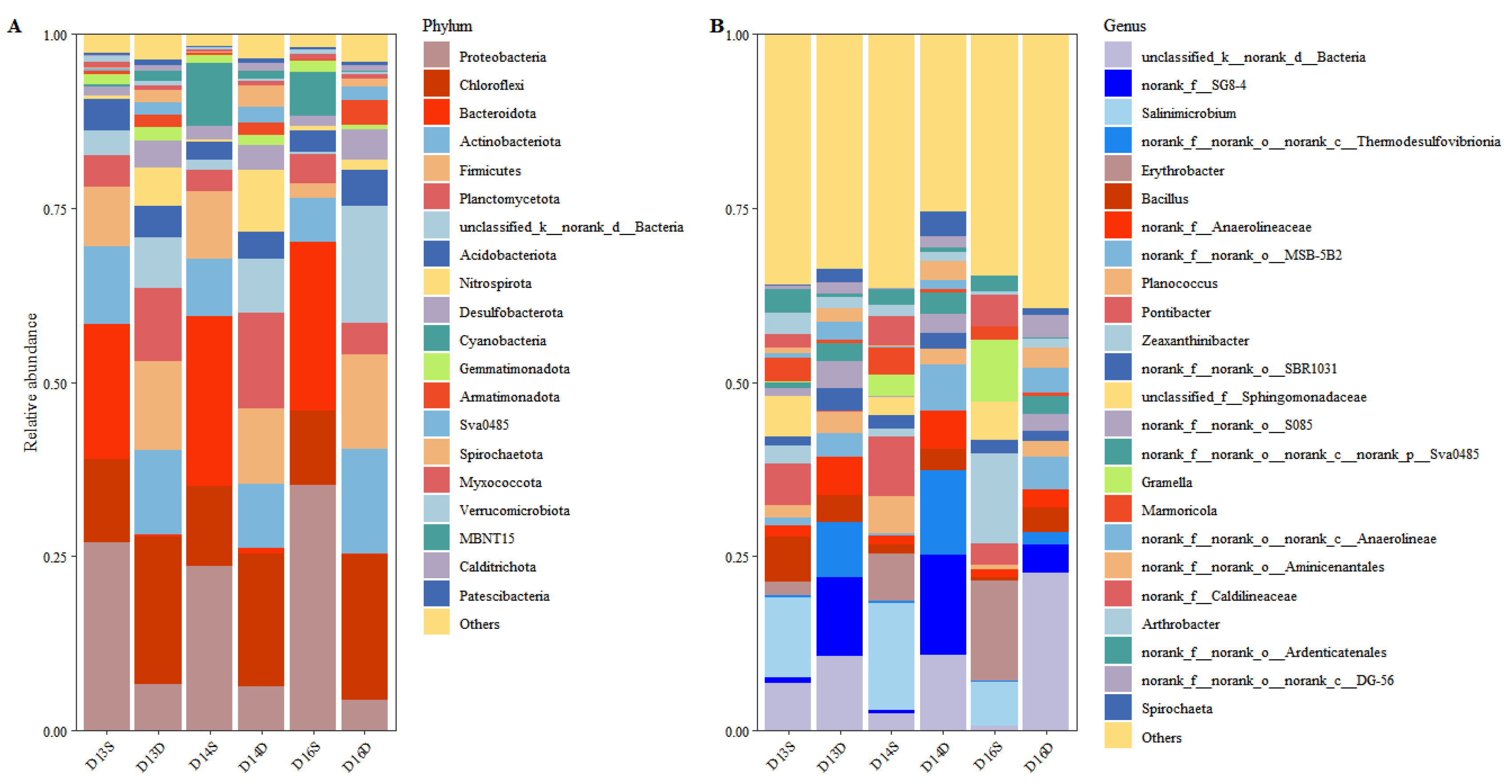

Phylum-level analysis revealed a broadly consistent bacterial community structure across all samples, with Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes, and Planctomycetota comprising the dominant phyla (

Figure 2A). These six groups accounted for over 50% of the total relative abundance, aligning with prior findings that high light their ecological importance in various soil environments, particularly under stress conditions[

25]. Among these, Proteobacteria was the most dominant phylum in surface soils, with relative abundances of 27.01%, 23.67%, and 35.18% at sampling points D13S, D14S, and D16S, respectively. Notably, its relative abundance was higher in contaminated zones (D13S and D16S) compared to the uncontaminated site (D14S), suggesting an adaptive advantage of Proteobacteria in hydrocarbon- or halogenated compound-rich environments. Members of Proteobacteria include known taxa involved in the degradation of chlorinated solvents and BTEX compounds [

26], indicating potential enrichment of functional degraders under contaminant pressure. In contrast, Firmicutes exhibited a declining trend in polluted areas, decreasing from 9.74% at D14S (non-contaminated) to 2.03% at D16S (heavily contaminated with dichloromethane and 1,2-dichloroethane). This suggests a possible sensitivity of Firmicutes to CAHs, consistent with previous studies indicating limited CAH tolerance in many Firmicutes taxa [

27]. In deep soils, Actinobacteriota showed a notable increase in relative abundance at polluted sites (12.04%) compared to non-contaminated zones (9.21%). This pattern suggests that Actinobacteriota may possess enhanced resistance mechanisms to oxidative and chemical stress, possibly via robust cell wall structures or stress-related gene[

28]. Their enrichment in deeper, pollutant-rich zones supports their potential role in long-term soil adaptation and persistence under chlorine stress.

At the genus level, notable heterogeneity was observed among dominant taxa across sampling points (

Figure 2B). The most frequently detected genera included

Salinimicrobium,

Erythrobacter, norank_f_SG8-4, and norank_c_Thermodesulfovibrionia. The presence of multiple unclassified and norank genera highlights the potential involvement of previously uncharacterized microbial lineages in pollutant transformation processes, warranting further investigation using metagenomic or culture-based approaches.

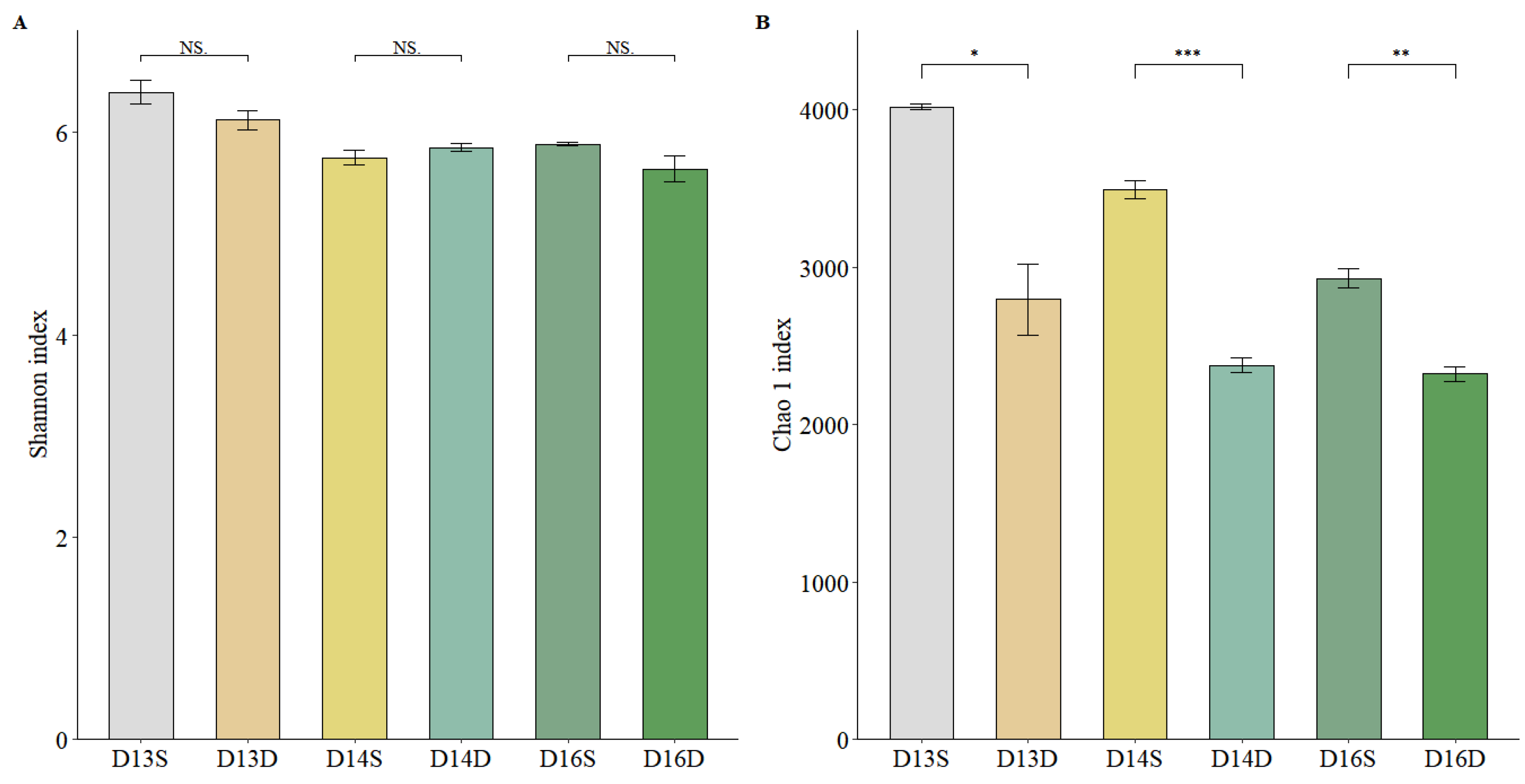

Microbial α-diversity was assessed using both the Chao1 richness index and Shannon diversity index (

Figure 3). Overall, both indices demonstrated a significant decline with increasing soil depth, suggesting reduced taxonomic richness and evenness in deeper layers. The highest richness and diversity were observed in the surface soil at sampling point D13S, a heavily polluted area, whereas the lowest values were recorded in the deep soil at point D16D. These results imply that pollutant-induced selection pressure may not uniformly reduce diversity; instead, shallow contaminated soils may harbor diverse microbial consortia enriched with specialized functional taxa capable of surviving or metabolizing the pollutants. This finding supports the hypothesis that pollutant exposure can act as a selective force, enriching for specialized, functionally redundant taxa and potentially promoting microbial niche differentiation[

29]. Conversely, deeper layers may experience greater anoxia, nutrient limitation, and pollutant persistence, limiting microbial colonization and activity.

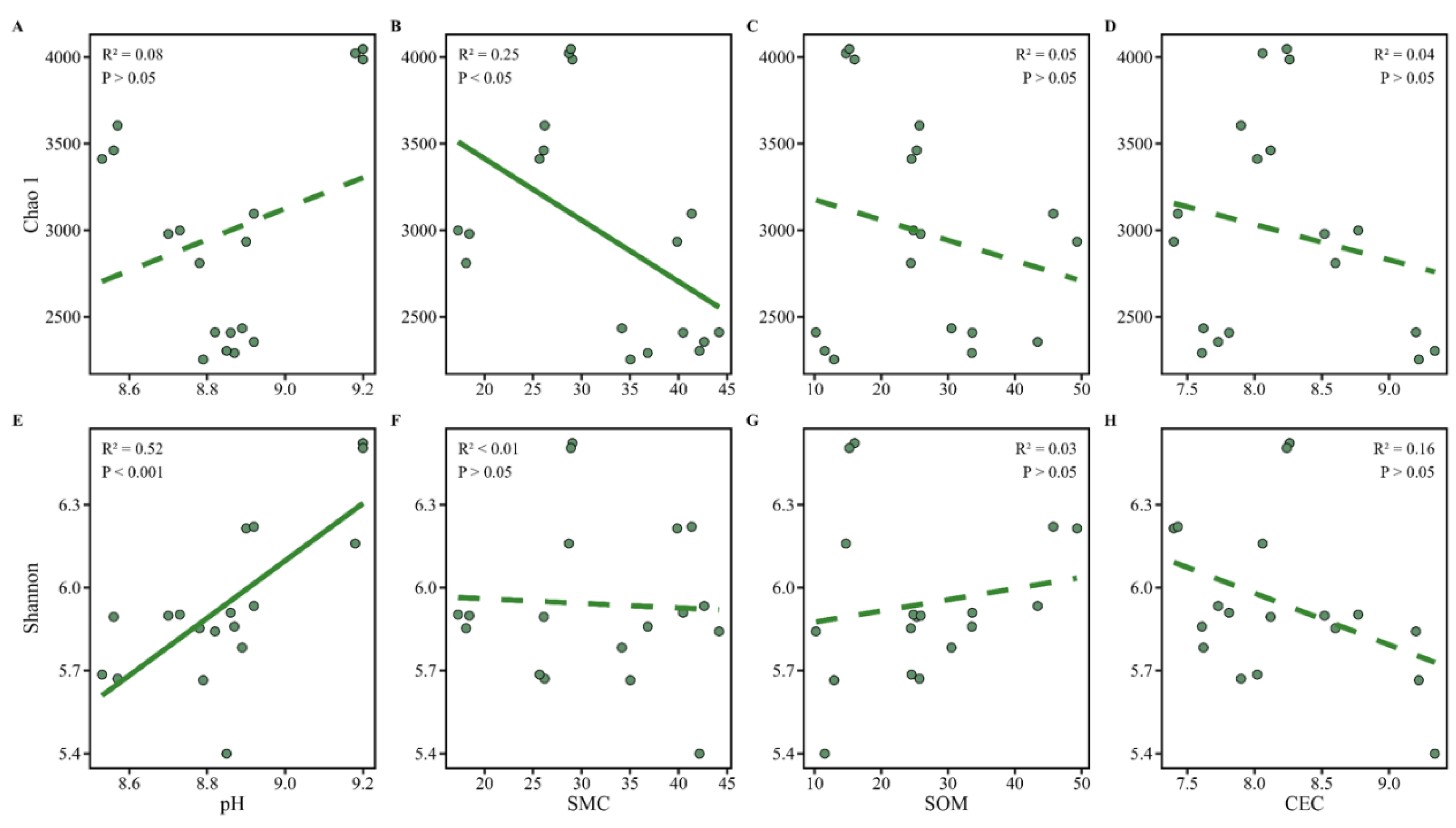

To explore environmental drivers of diversity, correlation analyses were conducted between α-diversity indices and soil physicochemical parameters (

Figure 4). The Shannon diversity index was positively correlated with soil pH, suggesting that moderately alkaline conditions may support greater microbial evenness. This aligns with broader evidence that neutral to mildly alkaline pH promotes microbial growth and community stability[

30]. On the other hand, soil moisture content (SMC) was negatively correlated with the Chao1 richness index, implying that elevated moisture levels (common in deeper soils) may create oxygen-limited environments that constrain aerobic microbial diversity and reduce overall taxonomic richness. Interestingly, SOM and CEC showed no significant correlation with microbial α-diversity, although CEC displayed a weak negative trend. This contrasts with some previous reports linking higher SOM and CEC to greater microbial abundance[

31], suggesting that in this highly contaminated context, pollutant toxicity and redox conditions may override the beneficial effects of organic matter on microbial colonization.

3.3. Impact of Soil Physicochemical Properties on Microbial Community Structure

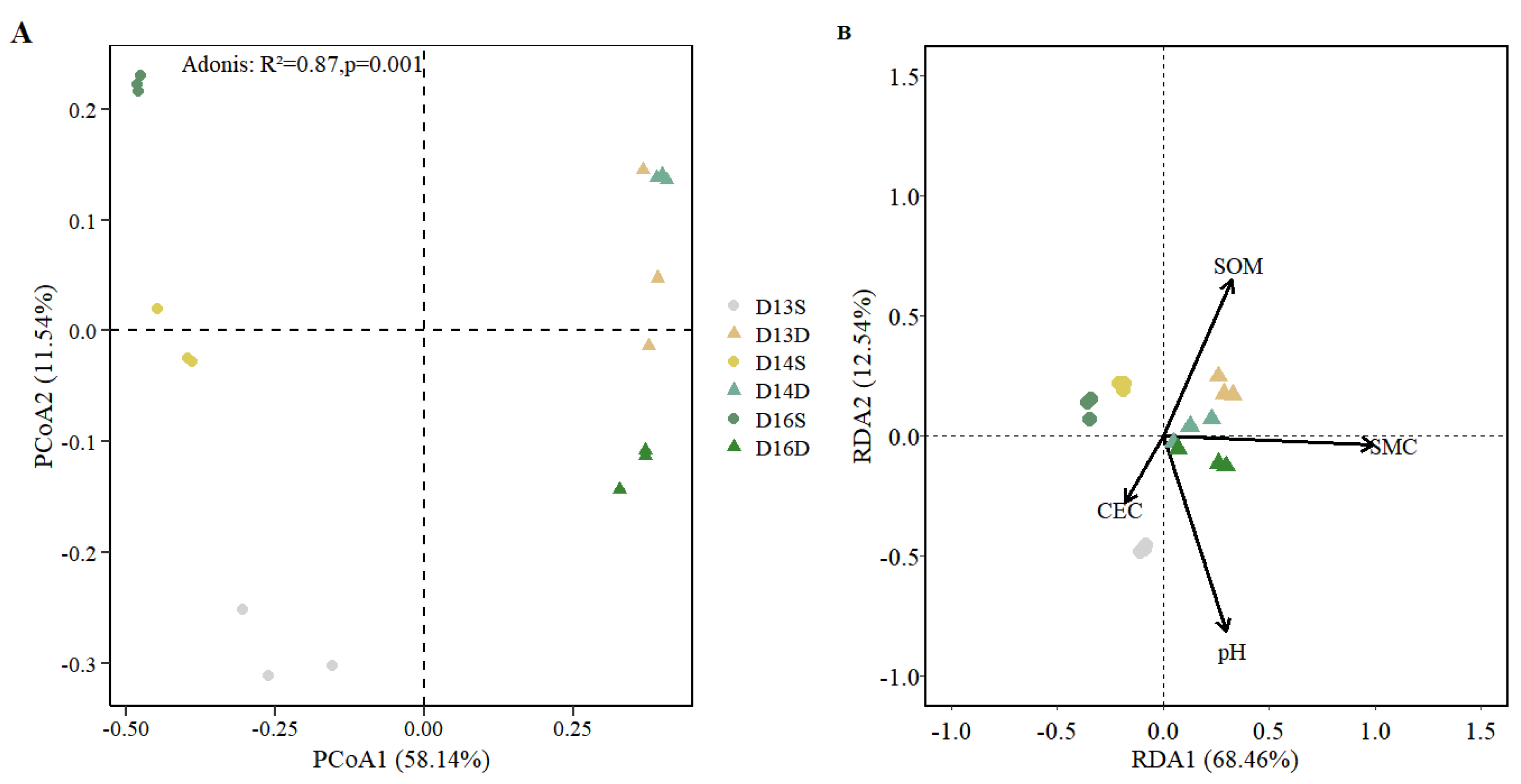

The spatial variations in microbial communities and their relationship with environmental factors were further investigate via principal coordinates analysis (PCoA, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities) (

Figure 5A). The first two axes, PCoA1 and PCoA2, explained 58.14% and 11.54% of the total variance in bacterial community composition, respectively. The clustering pattern showed clear separation among sampling sites, reflecting distinct microbial assemblages associated with different contamination zones and soil layers. Adonis (PERMANOVA) test confirmed that these differences in microbial community structure across sampling sites were statistically significant (

R² = 0.87,

P = 0.001), indicating that local environmental factors (particularly pollutant type and concentration) played a dominant role in shaping microbial community composition. Prior studies showed that hydrocarbon contamination exerts strong selective pressure on soil microbial communities, often leading to distinct community profiles in highly contaminated versus uncontaminated zones[

29,

32].

A notable pattern emerged when comparing microbial communities between surface and deep soils, with the two groups clearly separated in ordination space. This vertical stratification suggests that long-term exposure to CAHs, BTEX compounds, and CBs has altered microbial community structure with depth. sURFACE soils, which are more directly exposed to historical surface contamination and potentially more aerobic, tend to harbor functionally distinct microbial consortia compared to deeper, often more anaerobic environments [

33]. This vertical differentiation may also reflect both historical pollutant input patterns and depth-related gradients in redox conditions, moisture, and organic matter availability.

To further elucidate the environmental drivers of community composition, a redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted (

Figure 5B). The RDA revealed strong correlations between microbial community structure and several key soil physicochemical parameters, particularly soil moisture content, SOM, and pH. Soil moisture content emerged as the most influential factor, significantly affecting bacterial community structure, especially in deep soils (

P = 0.001). High moisture content at depth may create more reducing conditions, favoring anaerobic or facultatively anaerobic taxa involved in reductive degradation of chlorinated compounds [

23,

24]. In contrast, CEC showed a negative correlation with moisture content and was particularly influential in shaping microbial communities in surface soils at sampling site 13, where 1,2-dichloroethane concentrations were highest. High CEC in this zone may reflect the accumulation of exchangeable cations or charged degradation intermediates, which could influence microbial niche dynamics and stress adaptation [

34]. The co-variation of CEC and microbial community structure at heavily contaminated sites underscores the complex interactions between contaminant chemistry, soil matrix properties, and microbial ecological responses. Collectively, these findings suggest that both contamination profile and intrinsic soil properties jointly regulate microbial community assembly across contaminated zones. Depth-dependent environmental gradients and pollutant-specific selective pressures contribute to the spatial heterogeneity observed in microbial structure, highlighting the importance of integrated chemical-ecological assessments in evaluating natural attenuation potential.

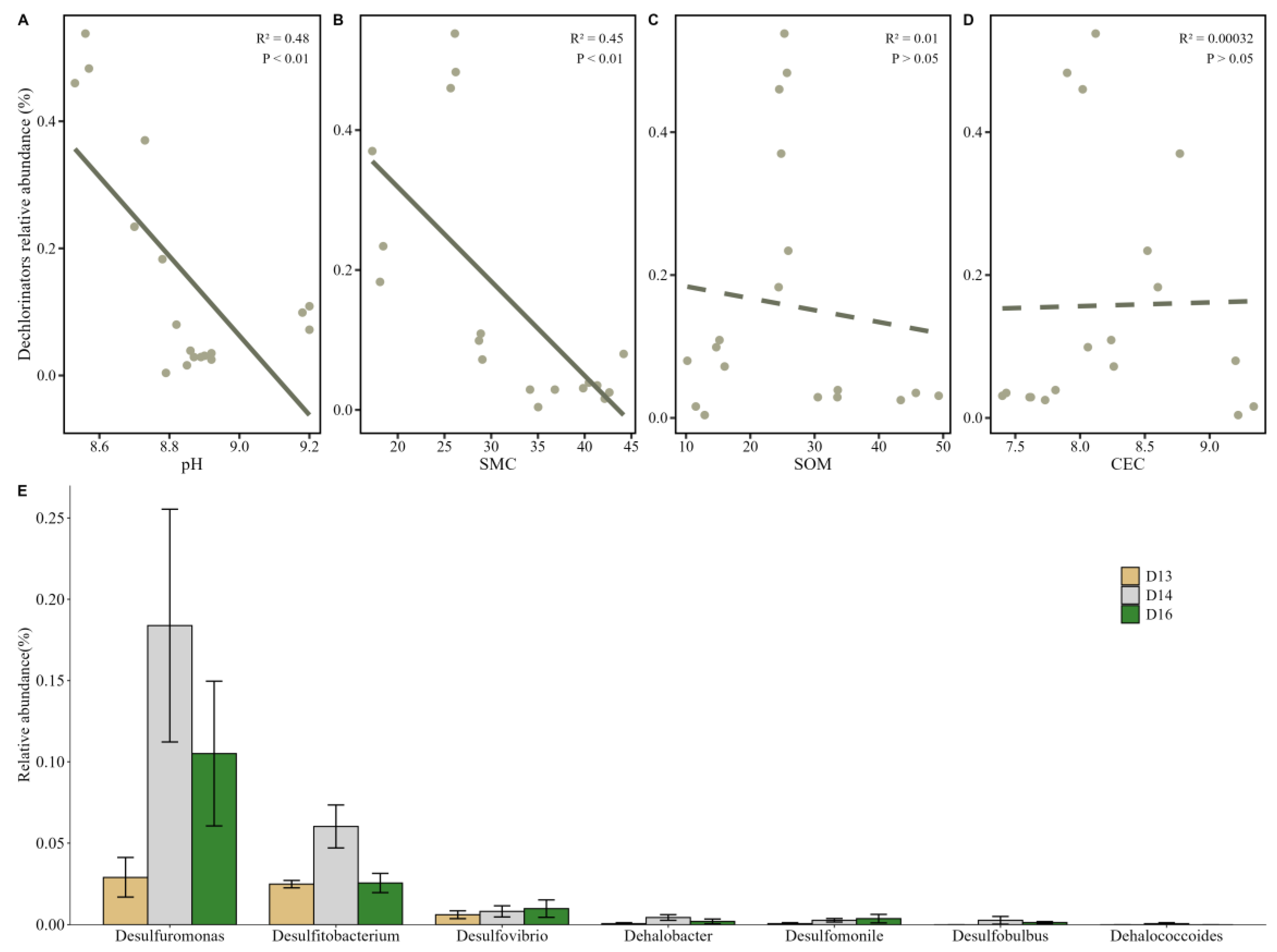

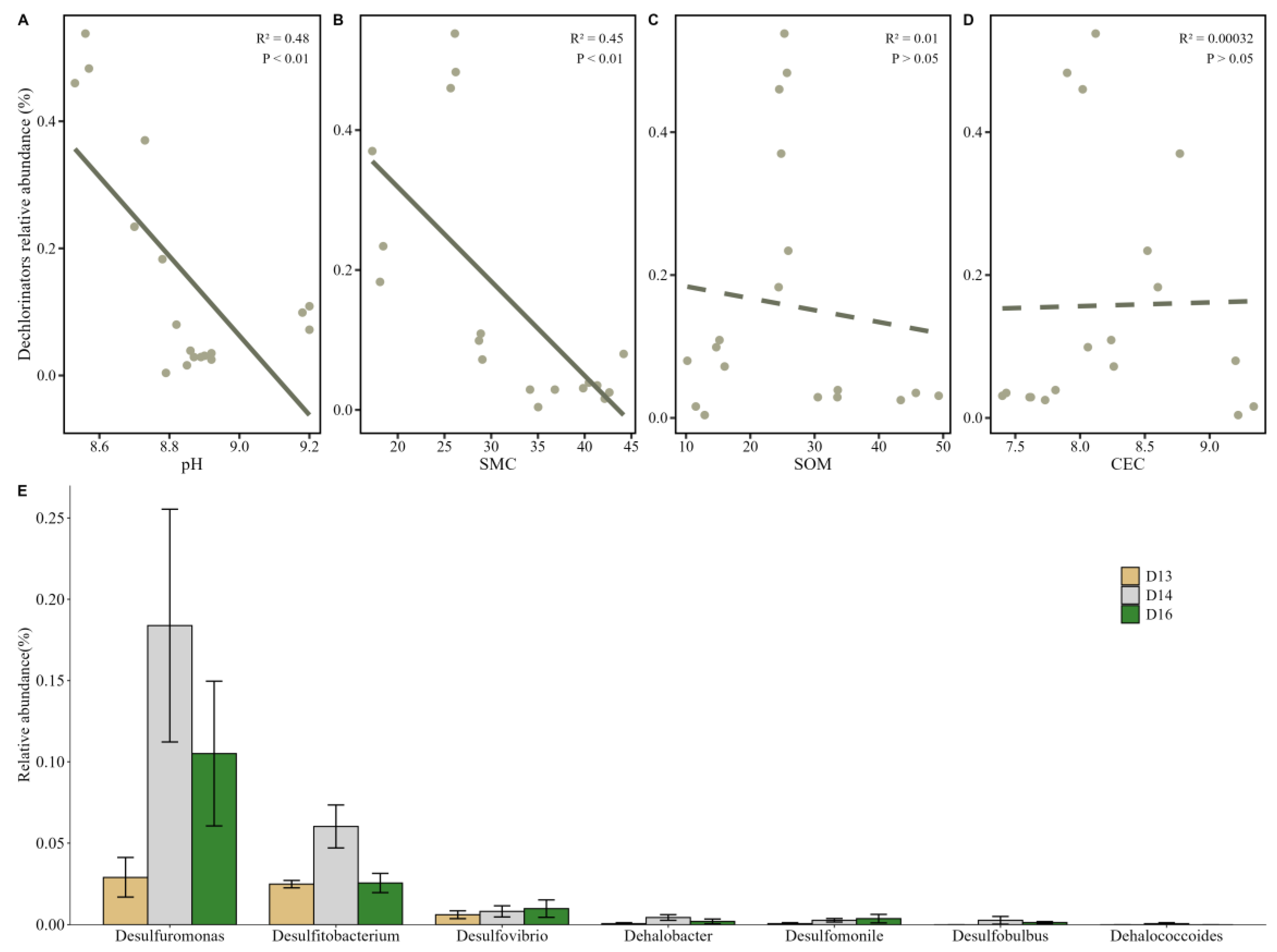

3.4. Impact of Soil Physicochemical Properties on Dechlorinating Bacteria

For assessing the distribution and ecological responses of key organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB), the relative abundance of known dechlorinating taxa was analyzed across sampling sites (

Figure 6E). Although the overall abundance of dechlorinating bacteria remained low (0–0.18%), several important taxa were consistently detected, including

Desulfuromonas and

Desulfitobacterium. These genera dominated both surface and deep soil layers and are well-known for their ability to perform reductive dechlorination under anaerobic conditions [

35], playing a pivotal role in the natural attenuation of chlorinated pollutants. Interestingly, the highest relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria was observed at sampling point 14, a site with pollutant concentrations below detection limits. In contrast, sites with severe contamination, such as sampling point 13 (1,2-dichloroethane: 418 mg/kg) and point 16 (dichloromethane: 598 mg/kg; 1,2-dichloroethane: 278 mg/kg; toluene: 191 mg/kg), exhibited substantially lower abundances of dechlorinators. These results suggest that extremely high pollutant concentrations may exert toxic effects on microbial populations, inhibiting the growth, metabolism, or viability of sensitive dechlorinating taxa [

36,

37]. Toxicity at highly contaminated sites may be further amplified by adverse environmental conditions (e.g., oxygen limitation, accumulation of toxic intermediates, or high redox potential) that suppress microbial respiration and enzymatic activity required for dehalorespiration [

38]. Notably, Dehalococcoides, a strictly anaerobic genus capable of complete dechlorination of highly chlorinated solvents, was detected only at sampling point 14, further reinforcing the idea that favorable, less toxic conditions are essential for the persistence of highly specialized dechlorinators. Other taxa such as

Desulfobulbus were observed at sampling points 14 and 16, while

Desulfovibrio and

Desulfomonile were selectively enriched in more contaminated zones. These genera have been previously associated with versatile metabolic capabilities, including the use of alternative electron donors or acceptors and the capacity to tolerate complex contaminant mixtures [

15]. For example,

Desulfomonile has been reported to degrade both chlorinated solvents and aromatic hydrocarbons, suggesting possible niche overlap in sites co-contaminated with CAHs and BTEX compounds [

37].

Linear regression analysis revealed significant negative correlations between the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria and both soil pH (

P < 0.01) (

Figure 6A) and soil moisture content (

P < 0.001) (

Figure 6B), while no significant relationships were observed with SOM or CEC (

Figure 6C & 6D). The negative association with pH suggests that alkaline conditions may inhibit dehalorespiration activity, which is typically favored in neutral to mildly acidic environments [

39]. Meanwhile, high moisture content, particularly in deeper soils, may create highly reducing or anoxic microenvironments unfavorable to certain facultative anaerobic dechlorinators or may limit substrate diffusion and microbial mobility.

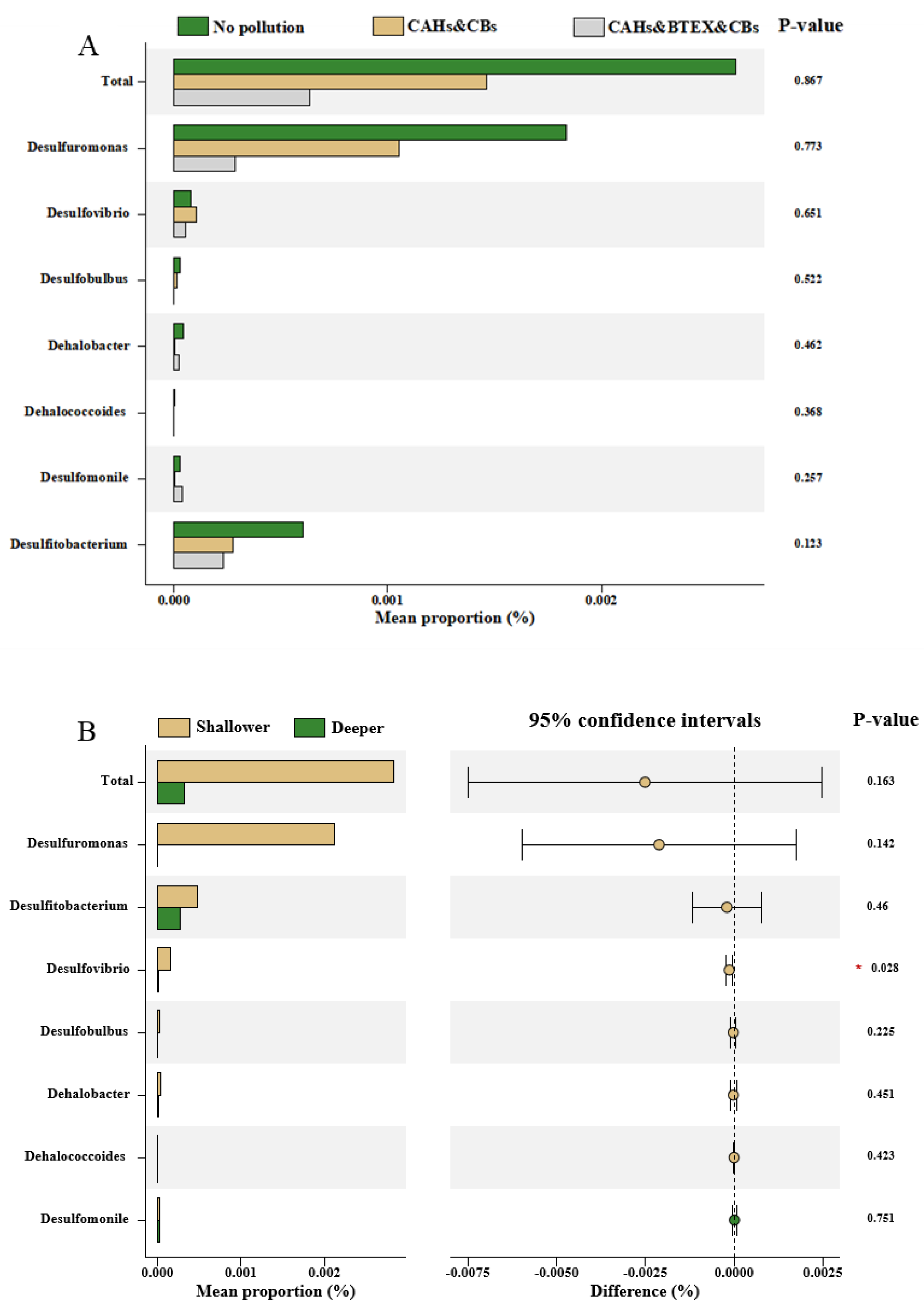

To further explore community-level trends, sampling points were grouped by contaminant profiles into three categories: CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite contamination (D13S and D16D), BTEX–CBs contamination (D13D and D16S), and non-contaminated group (D14S and D14D). The Kruskal–Wallis test (

Figure 7A) demonstrated that the highest cumulative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria occurred in the non-contaminated group, particularly for

Desulfuromonas,

Desulfitobacterium,

Dehalobacter,

Desulfobulbus, and

Dehalococcoides. In contrast,

Desulfovibrio showed its highest abundance in the CAHs–CBs composite zone, while

Desulfomonile peaked in the CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite area, suggesting a selective tolerance or adaptation to different pollutant mixtures. These results imply that contamination composition, not just pollutant concentration, plays a key role in shaping the community of OHRB. The presence of microbial taxa capable of utilizing both chlorinated compounds and aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g.,

Desulfomonile and

Desulfovibrio) indicates potential synergistic biodegradation mechanisms in co-contaminated zones. Previous studies suggest that some BTEX compounds may serve as alternative electron donors, enhancing the metabolic activity of organohalide-respiring bacteria and thereby indirectly promoting CBs degradation [

15,

38]. This co-metabolic potential supports the ecological feasibility of natural attenuation even in complex, multi-contaminant scenarios.

3.5. Impact of Spatial Factors on Dechlorinating Bacteria

The vertical distribution of dechlorinating bacteria across soil profiles revealed pronounced spatial heterogeneity (

Figure 7B). Notably, the total relative abundance of dechlorinating taxa was 7.86 times higher in surface soils compared to deep soils. Dominant genera included

Desulfuromonas,

Desulfitobacterium, and

Desulfovibrio. Interestingly,

Desulfobulbus was exclusively detected in surface layers, while

Dehalococcoides was found only in deep soils. This stratified pattern suggests that soil depth plays a critical role in structuring dechlorinating bacterial communities, likely due to its influence on redox conditions and contaminant bioavailability. The general trend of decreasing abundance with depth for most dechlorinating taxa (except Desulfomonile) can be attributed to depth-dependent physicochemical gradients, such as oxygen limitation, moisture content, and electron donor/acceptor availability. While dechlorinators are typically obligate or facultative anaerobes, surface soils may support more transitional redox zones, providing a broader spectrum of microhabitats for diverse dehalorespiring bacteria [

15].

Dehalococcoides mccartyi, for example, is known to persist in deeper subsurface environments under strict anaerobic conditions and to increase in abundance in deeper aquifers or soil layers where sustained reducing conditions are present [

40]. On the other hand, surface soils, often enriched with organic carbon and subject to variable aeration, may harbor a wider range of electron donors and support higher microbial diversity, including fermenters and syntrophs that can supply metabolic intermediates to dechlorinators.

The subsurface environment is inherently complex, characterized by overlapping redox zones and physical heterogeneity [

41]. These spatial features promote niche differentiation and microbial stratification, which in turn influence the spatial dynamics of natural attenuation. Therefore, understanding depth-resolved microbial composition is essential for evaluating the distribution of dechlorinating potential across contamination profiles [

42,

43].

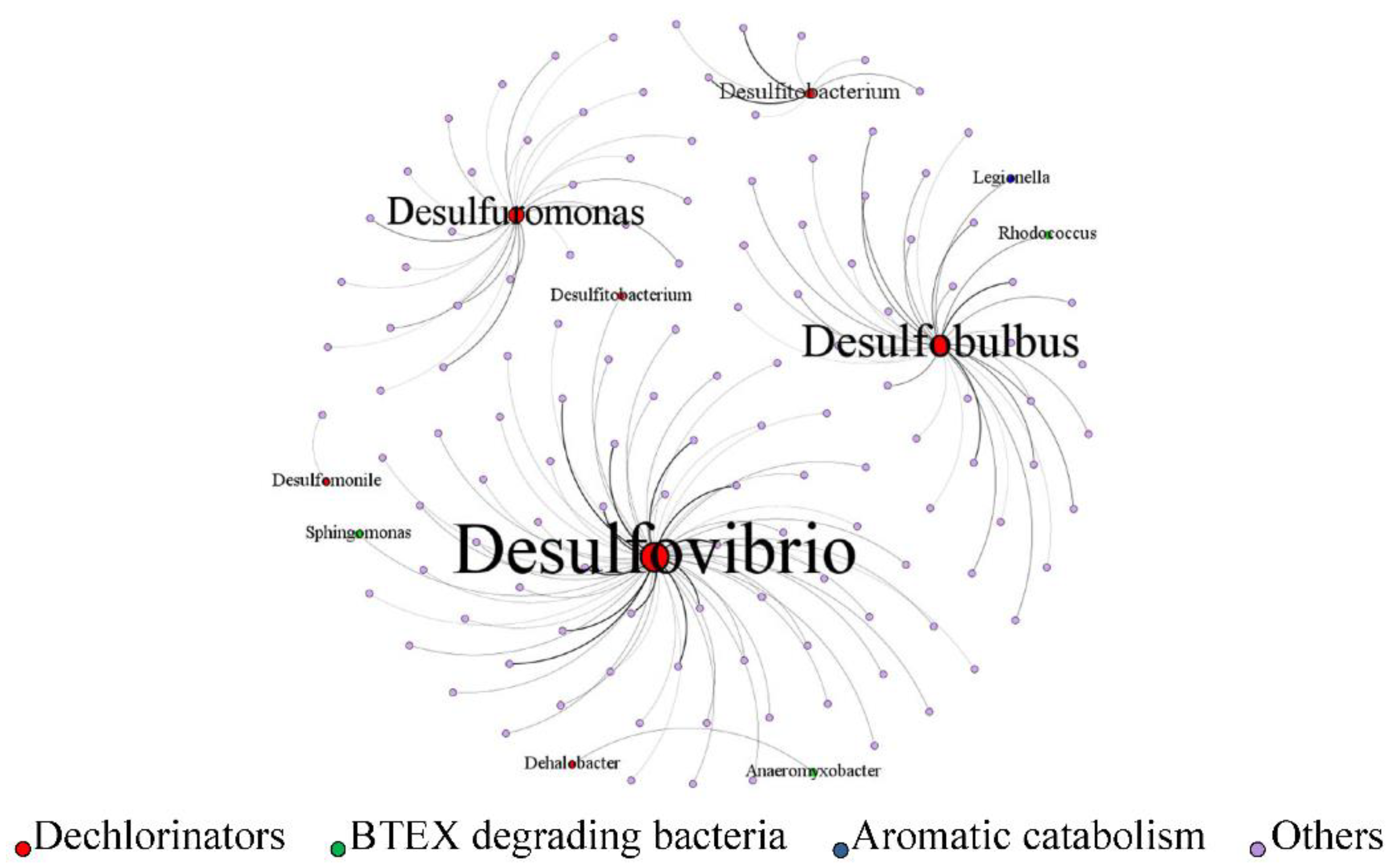

3.6. Interactions Among Key Microbial Species During Natural Attenuation

Co-occurrence network analysis was performed to investigate potential microbial interactions that facilitate pollutant degradation, with a focus on the relationships between dechlorinating bacteria and other functional microbial groups (

Figure 8). The results revealed strong positive correlations between bacteria groups that were involved in dichlorination, BTEX degradation and aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism, and prominent genera included

Sphingomonas,

Rhodococcus,

Anaeromyxobacter (hydrocarbon-degrading capabilities), and

Legionella (associated with the metabolism of aromatic intermediates). Based on the network structure and previous literature, we propose a cooperative microbial interaction model that facilitates composite pollutant degradation. Bacteria involved in BTEX degradation can efficiently metabolize monoaromatic hydrocarbons under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, producing short-chain fatty acids (e.g., acetate, muconate, lactate) as byproducts [

44]. These organic acids can serve as direct electron donors for dechlorinating bacteria, thereby stimulating reductive dechlorination activity [

45]. Moreover, fermentative bacteria may further metabolize long-chain fatty acids or complex organics, generating hydrogen (H₂), a key electron donor required for energy metabolism in several obligate dehalorespiring bacteria such as

Dehalococcoides and

Desulfitobacterium [

46]. This trophic interdependence suggests that BTEX-degrading and fermentative microbes enhance the metabolic activity and proliferation of dechlorinators, particularly in redox-stratified environments.

The underground environment’s spatial heterogeneity, including gradients of oxygen, redox potential, and organic matter, supports the coexistence of functionally distinct microbial guilds [

41,

42]. The observed mutualistic interactions between BTEX degraders, fermenters, and dechlorinators imply a synergistic microbial network capable of sustaining composite pollutant attenuation. This network-driven functionality is essential for the co-removal of structurally diverse pollutants like CAHs, BTEX, and CBs, and supports the feasibility of natural attenuation as an ecologically viable remediation strategy at this contaminated site.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the microbial ecological responses and natural attenuation potential at a decommissioned pharmaceutical-chemical site heavily contaminated with dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloroethane, and toluene. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing revealed that bacterial community composition varied significantly across contamination gradients and soil depths, shaped primarily by soil pH, moisture content, and pollutant type. Statistical analyses showed that soil pH and moisture were key environmental factors negatively affecting the abundance of dechlorinating bacteria, including Desulfuromonas, Desulfitobacterium, and Desulfovibrio, across all sampling sites. Spatial distribution patterns further indicated that dechlorinating taxa were more prevalent in surface soils, where transitional redox conditions may support greater microbial activity. Our results also suggest the presence of cooperative metabolic interactions. These interactions point to the feasibility of co-degradation of BTEX and chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons (CAHs) under natural attenuation conditions. However, the overall low abundance of dechlorinating taxa suggests that the intrinsic bioremediation potential is limited. These findings provide critical insights into microbial constraints and ecological dynamics at organically contaminated sites and highlight the need for enhanced remediation strategies. Future efforts should consider bioaugmentation or biostimulation approaches to increase the abundance and activity of dechlorinators, thereby improving the efficiency and sustainability of site remediation.

Author Contributions

X.G.: methodology, writing-original draft, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, project administration and funding acquisition. Q.L.: methodology, writing-original draft, data curation, formal analysis and validation. Y.C.: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing, supervision. Y.X.: data curation, formal analysis. T.M.: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing, project administration, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42307059).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eldridge, D.J.; Cui, H.; Ding, J.; Berdugo, M.; Sáez-Sandino, T.; Duran, J.; Gaitan, J.; Blanco-Pastor, J.L.; Rodríguez, A.; Plaza, C. Urban greenspaces and nearby natural areas support similar levels of soil ecosystem services. npj Urban Sustainability 2024, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Gaitan, J.J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C.D.; Singh, B.K. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Radosevich, M.; Debruyn, J.M.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Mcdearis, R.; Zhuang, J. Incorporating viruses into soil ecology: A new dimension to understand biogeochemical cycling. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2024, 54, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.K.; Selladurai, R.; Coumar, M.V.; Dotaniya, M.; Kundu, S.; Patra, A.K.; Saha, J.K.; Selladurai, R.; Coumar, M.V.; Dotaniya, M. Soil and its role in the ecosystem. Soil pollution-an emerging threat to agriculture, 2017; 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nizamani, M.M.; Hughes, A.C.; Qureshi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Tarafder, E.; Das, D.; Acharya, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.-G. Microbial biodiversity and plant functional trait interactions in multifunctional ecosystems. Applied Soil Ecology 2024, 201, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, D.; Ge, T.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X. Unveiling the top-down control of soil viruses over microbial communities and soil organic carbon cycling: A review. 2024.

- Gupta, A.; Singh, U.B.; Sahu, P.K.; Paul, S.; Kumar, A.; Malviya, D.; Singh, S.; Kuppusamy, P.; Singh, P.; Paul, D. Linking soil microbial diversity to modern agriculture practices: a review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trellu, C.; Pechaud, Y.; Oturan, N.; Mousset, E.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Huguenot, D.; Oturan, M.A. Remediation of soils contaminated by hydrophobic organic compounds: How to recover extracting agents from soil washing solutions? Journal of hazardous materials 2021, 404, 124137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Geng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Sun, L.; Xue, B.; Fujita, T. Reconsidering brownfield redevelopment strategy in China’s old industrial zone: a health risk assessment of heavy metal contamination. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22, 2765–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ruth, M. Relocation or reallocation: Impacts of differentiated energy saving regulation on manufacturing industries in China. Ecological Economics 2015, 110, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, Y.; Komai, T. A case study of natural attenuation of chlorinated solvents under unstable groundwater conditions in Takahata, Japan. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology 2019, 102, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.L.; DeSutter, T.M.; Casey, F.X. Natural degradation of low-level petroleum hydrocarbon contamination under crop management. Journal of soils and sediments 2019, 19, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, U.; Ahmad, H.; Shafqat, H.; Babar, M.; Munir, H.M.S.; Sagir, M.; Arif, M.; Hassan, A.; Rachmadona, N.; Rajendran, S. Remediation techniques for elimination of heavy metal pollutants from soil: A review. Environmental research 2022, 214, 113918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Ju, F.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Mulla, S.I.; Sun, Q.; Bürgmann, H.; Yu, C.P. Strong impact of anthropogenic contamination on the co-occurrence patterns of a riverine microbial community. Environmental microbiology 2017, 19, 4993–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, M.; Deng, S.; Long, T.; Sun, L.; Yu, R. Field study of microbial community structure and dechlorination activity in a multi-solvents co-contaminated site undergoing natural attenuation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 423, 127010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declercq, I.; Cappuyns, V.; Duclos, Y. Monitored natural attenuation (MNA) of contaminated soils: state of the art in Europe—a critical evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 426, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, C.; Chien, H.; Surampalli, R.; Chien, C.; Chen, C. Assessing of natural attenuation and intrinsic bioremediation rates at a petroleum-hydrocarbon spill site: Laboratory and field studies. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2010, 136, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, N.B.; Maphosa, F.; Morillo, J.A.; Abu Al-Soud, W.; Langenhoff, A.A.; Grotenhuis, T.; Rijnaarts, H.H.; Smidt, H. Impact of long-term diesel contamination on soil microbial community structure. Applied and environmental microbiology 2013, 79, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEE. Soil environmental quality Risk control standard for soil contamination of development land (for Trial Implementation). 2018, GB36600-2018(In Chinese, 15P.;A14.

- Osterman, G.; Knight, R. Measurement of vadose zone water content with direct-push nuclear magnetic resonance logging. Environmental Research Communications 2025, 7, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Soil and agro-chemistry analytical methods [M]. 1999(In Chinese).

- Tang, L.; Zhao, X.; Ling, W.W. Distribution of bound-PAH residues and their correlations with the bacterial community at different depths of soil from an abandoned chemical plant site. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 453, 131328.131321–131328.131312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.J.; Löffler, F.E.; Tiedje, J.M. Microbial community changes associated with a shift from reductive dechlorination of PCE to reductive dechlorination of cis-DCE and VC. Environmental science & technology 2000, 34, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Tao, S.; Wang, X. Interactions between organic pollutants and carbon nanomaterials and the associated impact on microbial availability and degradation in soil: a review. Environmental Science: Nano 2020, 7, 2486–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Oliverio, A.M.; Brewer, T.E.; Benavent-Gonzalez, A.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K.; Fierer, N. A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil. Science 2018, 359, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, G. Bacterial communities in oil contaminated soils: biogeography and co-occurrence patterns. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2016, 98, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ward, O.P. Biodegradation and bioremediation; Springer Science & Business Media: 2004; Volume 2.

- Goodfellow, M.; Williams, S.T. Ecology of Actinomycetes. Annual Review of Microbiology 1984, 37, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermon, L.; Hellal, J.; Denonfoux, J.; Vuilleumier, S.; Imfeld, G.; Urien, C.; Ferreira, S.; Joulian, C. Functional genes and bacterial communities during organohalide respiration of chloroethenes in microcosms of multi-contaminated groundwater. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.C.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. The ISME journal 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Applied and environmental microbiology 2009, 75, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Hu, T.; Lv, R.; Wu, Y.; Chang, F.; Jia, F.a.; Gu, J. Succession of microbial communities and synergetic effects during bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil enhanced by chemical oxidation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 410, 124869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Lin, Y.; Huo, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, E.; Chen, W.; Wei, G. Microbial communities in riparian soils of a settling pond for mine drainage treatment. Water Research 2016, 96, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonangelo, J.A.; Culman, S.; Zhang, H. Comparative analysis and prediction of cation exchange capacity via summation: influence of biochar type and nutrient ratios. Frontiers in Soil Science 2024, 4, 1371777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, L.; Szewzyk, U.; Wecke, J.; Görisch, H. Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes. Nature 2000, 408, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, H.; Mou, L.; Ru, J.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, S. Long-term and high-concentration heavy-metal contamination strongly influences the microbiome and functional genes in Yellow River sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637, 1400–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Yang, M.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Ding, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. A new insight into the influencing factors of natural attenuation of chlorinated hydrocarbons contaminated groundwater: A long-term field study of a retired pesticide site. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 439, 129595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, D.; Yang, L.; Wei, J.; Kong, L.; Xie, W.; Ding, D.; Fan, T.; Deng, S. Natural attenuation of BTEX and chlorobenzenes in a formerly contaminated pesticide site in China: Examining kinetics, mechanisms, and isotopes analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, F.E.; Yan, J.; Ritalahti, K.M.; Adrian, L.; Edwards, E.A.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Müller, J.A.; Fullerton, H.; Zinder, S.H.; Spormann, A.M. Dehalococcoides mccartyi gen. nov., sp. nov., obligately organohalide-respiring anaerobic bacteria relevant to halogen cycling and bioremediation, belong to a novel bacterial class, Dehalococcoidia classis nov., order Dehalococcoidales ord. nov. and family Dehalococcoidaceae fam. nov., within the phylum Chloroflexi. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2013, 63, 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Němeček, J.; Dolinová, I.; Macháčková, J.; Špánek, R.; Ševců, A.; Lederer, T.; Černík, M. Stratification of chlorinated ethenes natural attenuation in an alluvial aquifer assessed by hydrochemical and biomolecular tools. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häggblom, M.M.; Bossert, I.D. Microbial processes and environmental applications. In Microbial processes and environmental applications.; Springer: 2003.

- Arora, B.; Mohanty, B.P. Influence of spatial heterogeneity and hydrological perturbations on redox dynamics: a column study. Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 2017, 17, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Tscherko, D.; Bruce, K.; Stemmer, M.; Hobbs, P.; Bardgett, R.D.; Amelung, W. Structure and function of the soil microbial community in microhabitats of a heavy metal polluted soil. Biology and fertility of soils 2000, 32, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, A.; Icgen, B. Aerobic bacterial degraders with their relative pathways for efficient removal of individual BTEX compounds. CLEAN–Soil, Air, Water 2018, 46, 1800068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sung, Y.; Dollhopf, M.E.; Fathepure, B.Z.; Tiedje, J.M.; Löffler, F.E. Acetate versus hydrogen as direct electron donors to stimulate the microbial reductive dechlorination process at chloroethene-contaminated sites. Environmental science & technology 2002, 36, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar]

- Heimann, A.C.; Friis, A.K.; Scheutz, C.; Jakobsen, R. Dynamics of reductive TCE dechlorination in two distinct H 2 supply scenarios and at various temperatures. Biodegradation 2007, 18, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of soil sampling locations across the contaminated site. The layout of 18 soil sampling points used for physicochemical and microbial analyses was illustrated. Sampling locations span areas with varying degrees of contamination, including zones impacted by chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons (CAHs), BTEX compounds, and chlorinated benzenes (CBs), as well as relatively uncontaminated control areas. Both surface (0–0.5 m) and deep (2–2.5 m) soil layers were sampled at each location to capture vertical heterogeneity in pollutant distribution and microbial community structure. The map provides context for spatial comparisons of contaminant levels, soil properties, and microbial responses.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of soil sampling locations across the contaminated site. The layout of 18 soil sampling points used for physicochemical and microbial analyses was illustrated. Sampling locations span areas with varying degrees of contamination, including zones impacted by chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons (CAHs), BTEX compounds, and chlorinated benzenes (CBs), as well as relatively uncontaminated control areas. Both surface (0–0.5 m) and deep (2–2.5 m) soil layers were sampled at each location to capture vertical heterogeneity in pollutant distribution and microbial community structure. The map provides context for spatial comparisons of contaminant levels, soil properties, and microbial responses.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic composition of soil bacterial communities at different sampling points.(A) Relative abundance of dominant bacterial phyla across all soil samples, based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The top 20 phyla with the highest average relative abundances are shown, illustrating spatial variations in community composition associated with contamination levels and soil depth.(B) Relative abundance of dominant bacterial genera across all sampling sites. Genera with the highest contributions to community structure are presented, highlighting differences in microbial assemblages between polluted and non-polluted zones. Taxa labeled as “norank” or “unclassified” indicate unresolved or uncultured lineages, underscoring the complexity of the soil microbiome in contaminated environments.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic composition of soil bacterial communities at different sampling points.(A) Relative abundance of dominant bacterial phyla across all soil samples, based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The top 20 phyla with the highest average relative abundances are shown, illustrating spatial variations in community composition associated with contamination levels and soil depth.(B) Relative abundance of dominant bacterial genera across all sampling sites. Genera with the highest contributions to community structure are presented, highlighting differences in microbial assemblages between polluted and non-polluted zones. Taxa labeled as “norank” or “unclassified” indicate unresolved or uncultured lineages, underscoring the complexity of the soil microbiome in contaminated environments.

Figure 3.

Alpha diversity of soil microbial communities across different sampling points. Shannon diversity index (left) and Chao1 richness index (right) are used to assess microbial diversity and taxonomic richness, respectively, based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing data. Each bar represents the mean value for individual soil samples, including both shallow and deep layers. The results illustrate significant variations in microbial diversity and richness across contaminated and non-contaminated zones, as well as between soil depths. Higher diversity and richness were generally observed in surface soils, particularly in less-contaminated areas, suggesting that both contamination level and soil depth influence microbial community complexity. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Alpha diversity of soil microbial communities across different sampling points. Shannon diversity index (left) and Chao1 richness index (right) are used to assess microbial diversity and taxonomic richness, respectively, based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing data. Each bar represents the mean value for individual soil samples, including both shallow and deep layers. The results illustrate significant variations in microbial diversity and richness across contaminated and non-contaminated zones, as well as between soil depths. Higher diversity and richness were generally observed in surface soils, particularly in less-contaminated areas, suggesting that both contamination level and soil depth influence microbial community complexity. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Correlations between microbial α-diversity indices and soil physicochemical properties. The relationships between microbial α-diversity (measured by the Shannon diversity index and Chao1 richness) and key soil physicochemical parameters, i.e., pH, soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), and cation exchange capacity (CEC), were illustrated. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the strength and direction of correlations. Significant negative correlations were observed between dechlorinating bacterial abundance and both pH and SMC, while no significant relationships were found with SOM or CEC. These results suggest that pH and moisture are the primary environmental drivers shaping microbial diversity patterns in the contaminated soil environment.

Figure 4.

Correlations between microbial α-diversity indices and soil physicochemical properties. The relationships between microbial α-diversity (measured by the Shannon diversity index and Chao1 richness) and key soil physicochemical parameters, i.e., pH, soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), and cation exchange capacity (CEC), were illustrated. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the strength and direction of correlations. Significant negative correlations were observed between dechlorinating bacterial abundance and both pH and SMC, while no significant relationships were found with SOM or CEC. These results suggest that pH and moisture are the primary environmental drivers shaping microbial diversity patterns in the contaminated soil environment.

Figure 5.

Multivariate analysis of microbial community structure in relation to soil environmental factors. (A) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity showing the separation of microbial communities across different sampling points. Clear clustering is observed between surface and deep soil layers, reflecting compositional shifts associated with contamination levels and soil depth. (B) Redundancy Analysis (RDA) illustrating the influence of soil physicochemical properties, specifically soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), pH, and cation exchange capacity (CEC), on microbial community composition. Arrows represent environmental gradients, with the length and direction indicating their strength and correlation with microbial variation. The analysis highlights SMC and pH as the most significant factors shaping community structure, especially in deeper, more contaminated soils.

Figure 5.

Multivariate analysis of microbial community structure in relation to soil environmental factors. (A) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity showing the separation of microbial communities across different sampling points. Clear clustering is observed between surface and deep soil layers, reflecting compositional shifts associated with contamination levels and soil depth. (B) Redundancy Analysis (RDA) illustrating the influence of soil physicochemical properties, specifically soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), pH, and cation exchange capacity (CEC), on microbial community composition. Arrows represent environmental gradients, with the length and direction indicating their strength and correlation with microbial variation. The analysis highlights SMC and pH as the most significant factors shaping community structure, especially in deeper, more contaminated soils.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria and soil environmental factors. (A–D) Linear regression analyses showing the correlations between the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacterial taxa and key soil physicochemical properties: (A) pH, (B) soil moisture content (SMC), (C) soil organic matter (SOM), and (D) cation exchange capacity (CEC). Significant negative correlations were observed with pH and SMC, while no significant associations were found with SOM or CEC, suggesting that pH and moisture are critical regulators of dechlorinator abundance. (E) Comparison of the cumulative relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria across different monitoring zones categorized by contaminant composition: CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite pollution (D13S, D16D), BTEX–CBs co-contamination (D13D, D16S), and non-contaminated control group (D14S, D14D). Dechlorinator abundance was highest in the non-contaminated group, indicating pollutant stress may suppress functional bacterial populations critical for natural attenuation.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria and soil environmental factors. (A–D) Linear regression analyses showing the correlations between the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacterial taxa and key soil physicochemical properties: (A) pH, (B) soil moisture content (SMC), (C) soil organic matter (SOM), and (D) cation exchange capacity (CEC). Significant negative correlations were observed with pH and SMC, while no significant associations were found with SOM or CEC, suggesting that pH and moisture are critical regulators of dechlorinator abundance. (E) Comparison of the cumulative relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria across different monitoring zones categorized by contaminant composition: CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite pollution (D13S, D16D), BTEX–CBs co-contamination (D13D, D16S), and non-contaminated control group (D14S, D14D). Dechlorinator abundance was highest in the non-contaminated group, indicating pollutant stress may suppress functional bacterial populations critical for natural attenuation.

Figure 7.

Spatial variation in the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria across contamination types and soil depths. (A) Comparison of the cumulative relative abundance of dechlorinating bacterial genera among different pollution categories: CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite contamination (D13S, D16D), BTEX–CBs contamination (D13D, D16S), and non-contaminated control sites (D14S, D14D). (B) Comparison of dechlorinating bacterial abundance between shallow (0–0.5 m) and deep (2–2.5 m) soil layers. Overall, surface soils exhibited a 7.86-fold higher abundance of dechlorinators than deep soils, highlighting the influence of vertical environmental gradients (such as redox potential and organic substrate availability) on microbial functional group distribution.

Figure 7.

Spatial variation in the relative abundance of dechlorinating bacteria across contamination types and soil depths. (A) Comparison of the cumulative relative abundance of dechlorinating bacterial genera among different pollution categories: CAHs–BTEX–CBs composite contamination (D13S, D16D), BTEX–CBs contamination (D13D, D16S), and non-contaminated control sites (D14S, D14D). (B) Comparison of dechlorinating bacterial abundance between shallow (0–0.5 m) and deep (2–2.5 m) soil layers. Overall, surface soils exhibited a 7.86-fold higher abundance of dechlorinators than deep soils, highlighting the influence of vertical environmental gradients (such as redox potential and organic substrate availability) on microbial functional group distribution.

Figure 8.

The co-occurrence network of dechlorinators and other genera showed significantly positive correlations with dechlorinators.

Figure 8.

The co-occurrence network of dechlorinators and other genera showed significantly positive correlations with dechlorinators.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of soil at different point locations.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of soil at different point locations.

| |

D13 |

D14 |

D16 |

| Depth |

D13S |

D13D |

D14S |

D14D |

D16S |

D16D |

| pH |

9.19±0.01a |

8.91±0.01b |

8.55±0.01e |

8.87±0.01b |

8.74±0.02d |

8.82±0.02c |

| SMC (%) |

28.88±0.11b |

41.27±0.81a |

25.99±0.17b |

37.14±1.83a |

17.94±0.35c |

40.44±2.78a |

| SOM (g/kg) |

15.30±0.38d |

46.15±1.71a |

25.17±0.35c |

32.55±1.02b |

25.03±0.45c |

11.54±0.78e |

| CEC (cmol+/kg) |

8.19±0.06c |

7.52±0.10d |

8.01±0.06c |

7.68±0.07d |

8.63±0.07b |

9.26±0.04a |

| CAHs (mg/kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chloromethane |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.0075 |

0 |

| Chloroethene |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.292 |

0.0572 |

| Dichloromethane |

0.111 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

355 |

598 |

| Chloroform |

0.366 |

0.233 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.0794 |

| 1,2-dichloroethane |

418 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

278 |

140 |

| BTEX (mg/kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Toluene |

0.0229 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

191 |

| o-Xylene |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.101 |

| CB (mg/kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chlorobenzene |

0.123 |

0.0109 |

ND |

ND |

0.287 |

ND |

| 1,4-Dichlorobenzene |

0.326 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| 1,2-Dichlorobenzene |

0.414 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.108 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).