Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

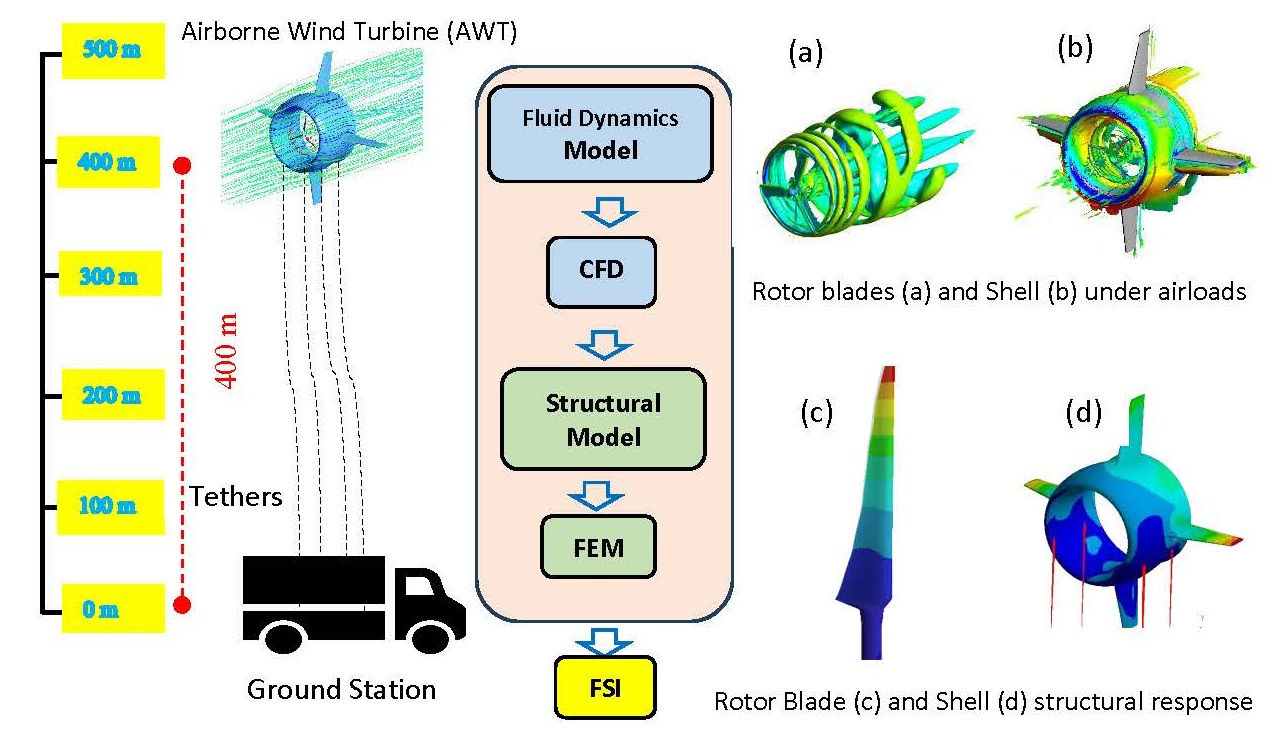

1. Introduction

2. Bat Energy System

3. One-Way FSI Analysis

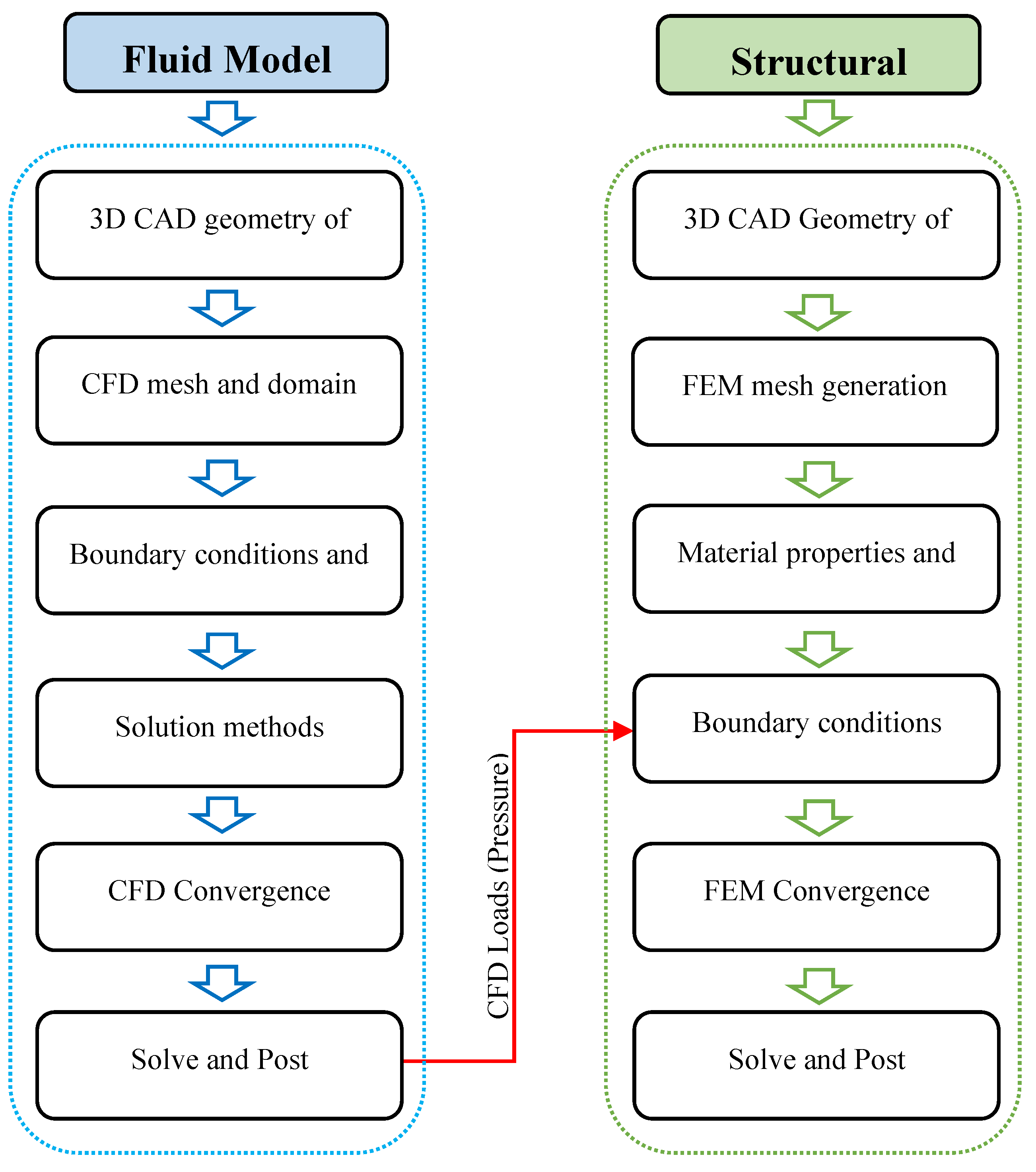

3.1. Fluid Model

3.2. Structural Model

4. Method of Solution

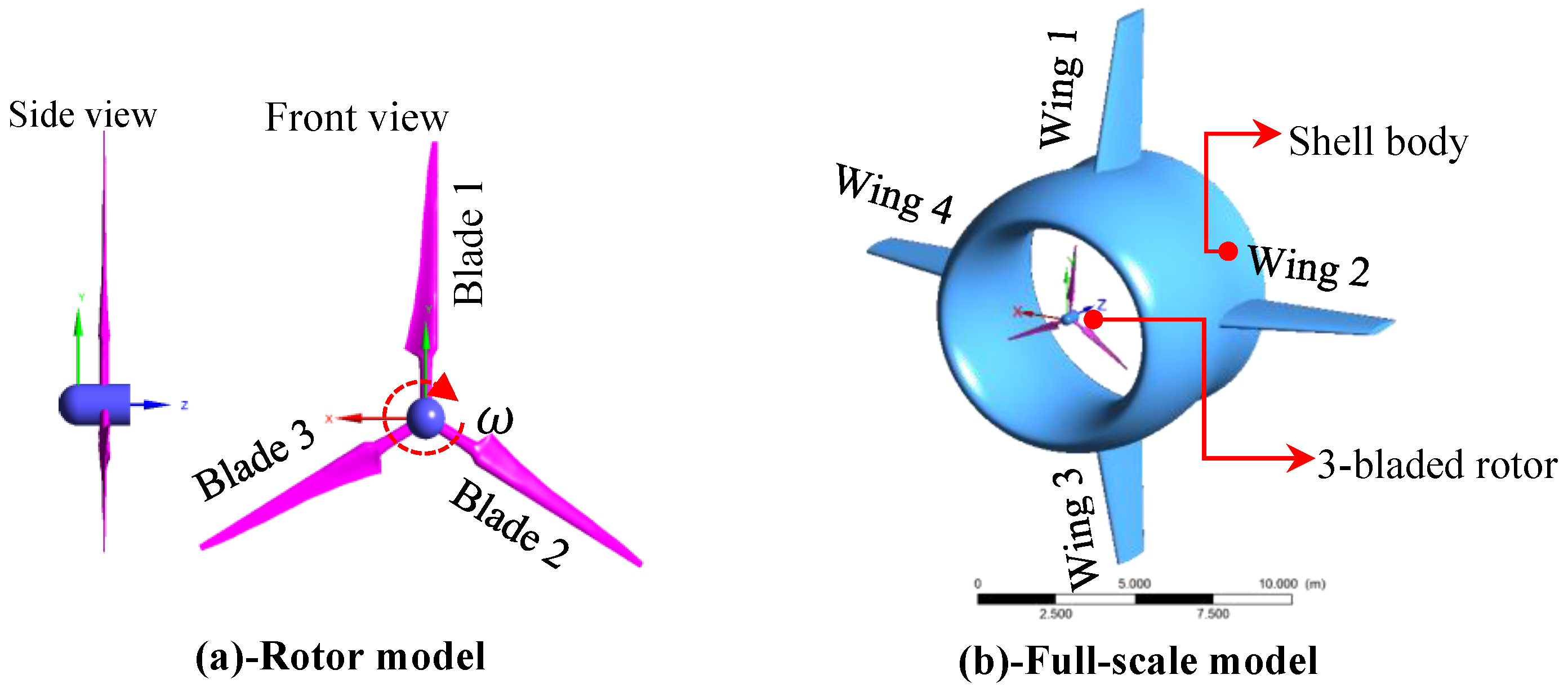

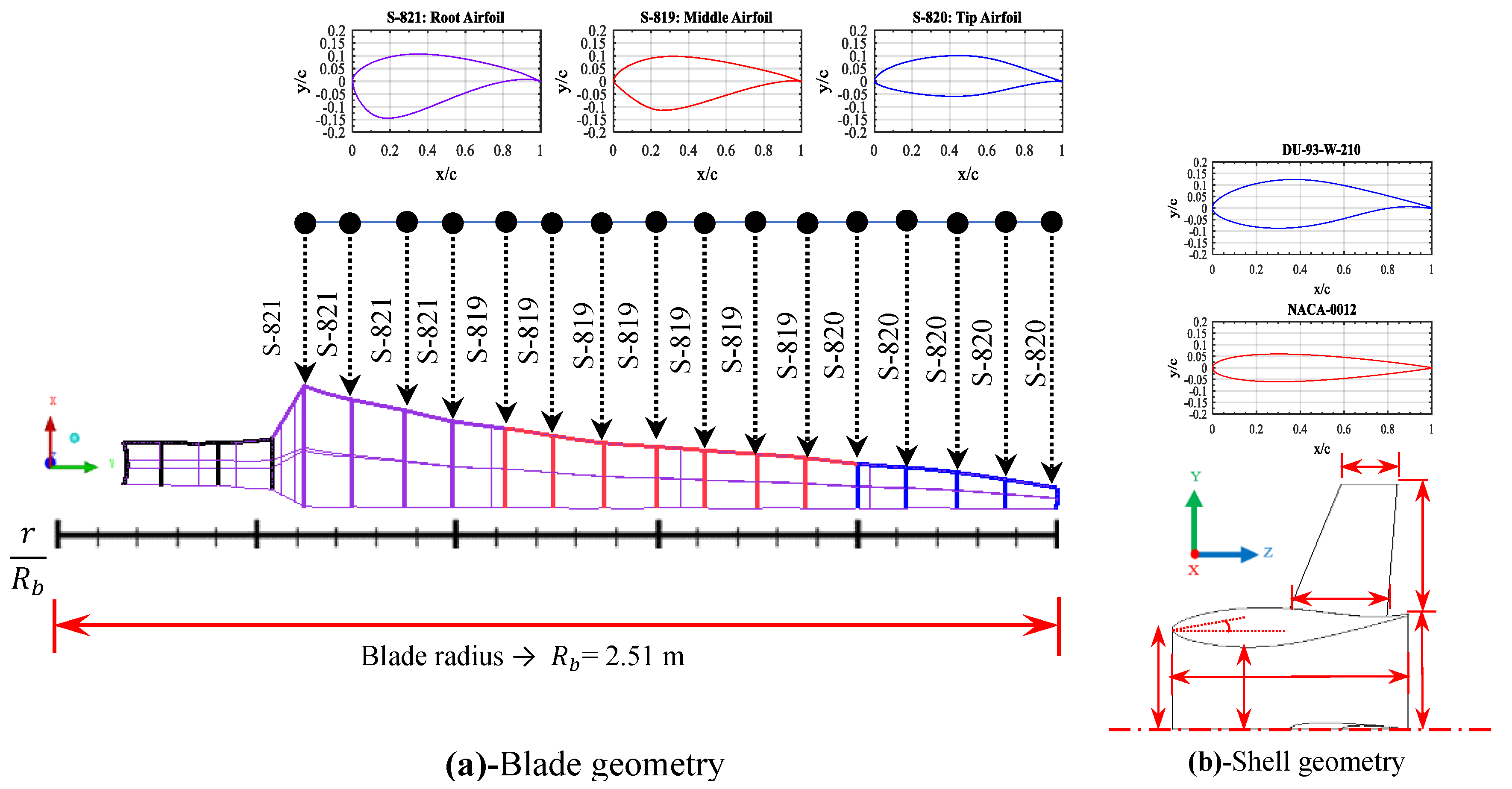

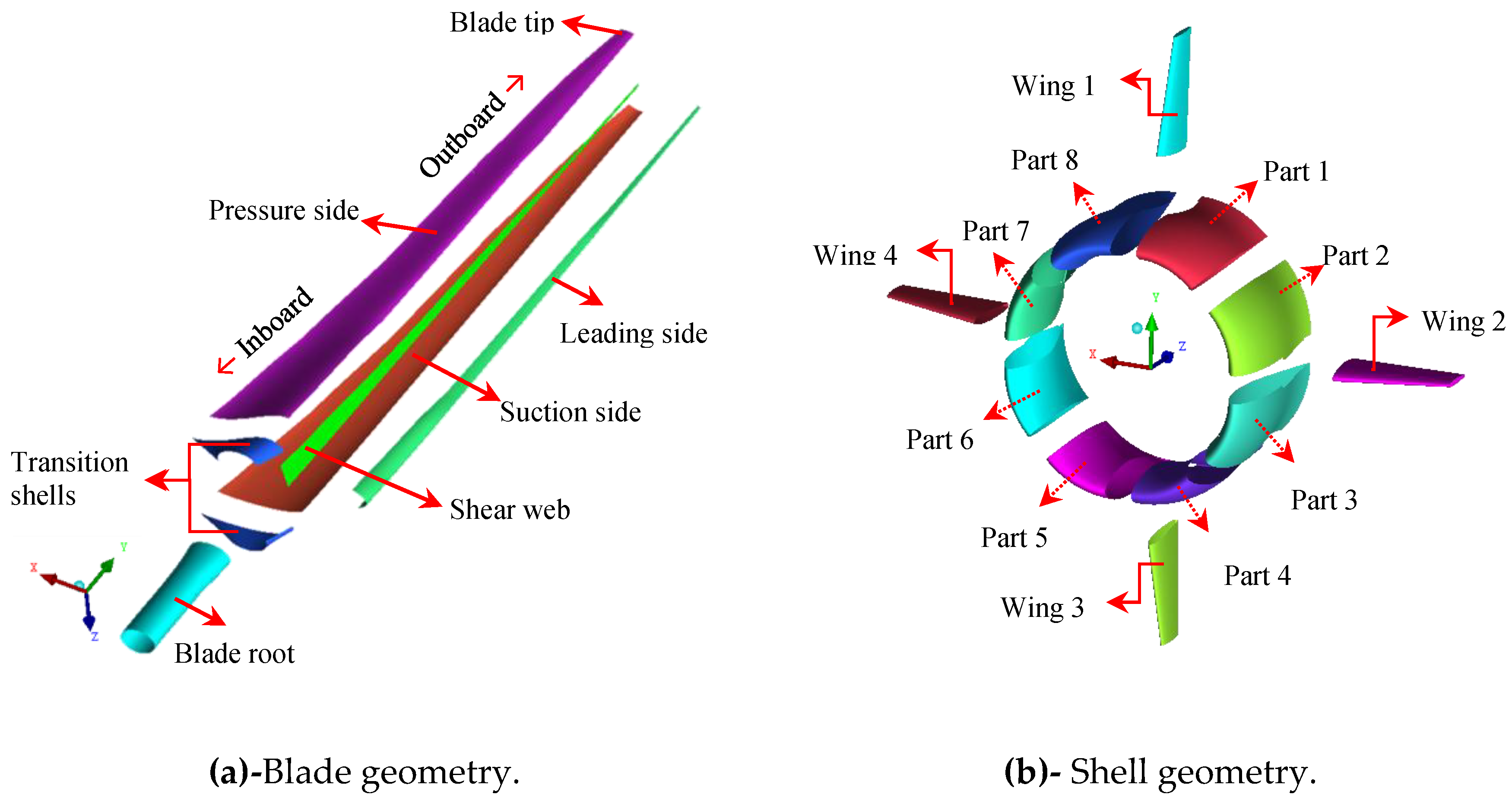

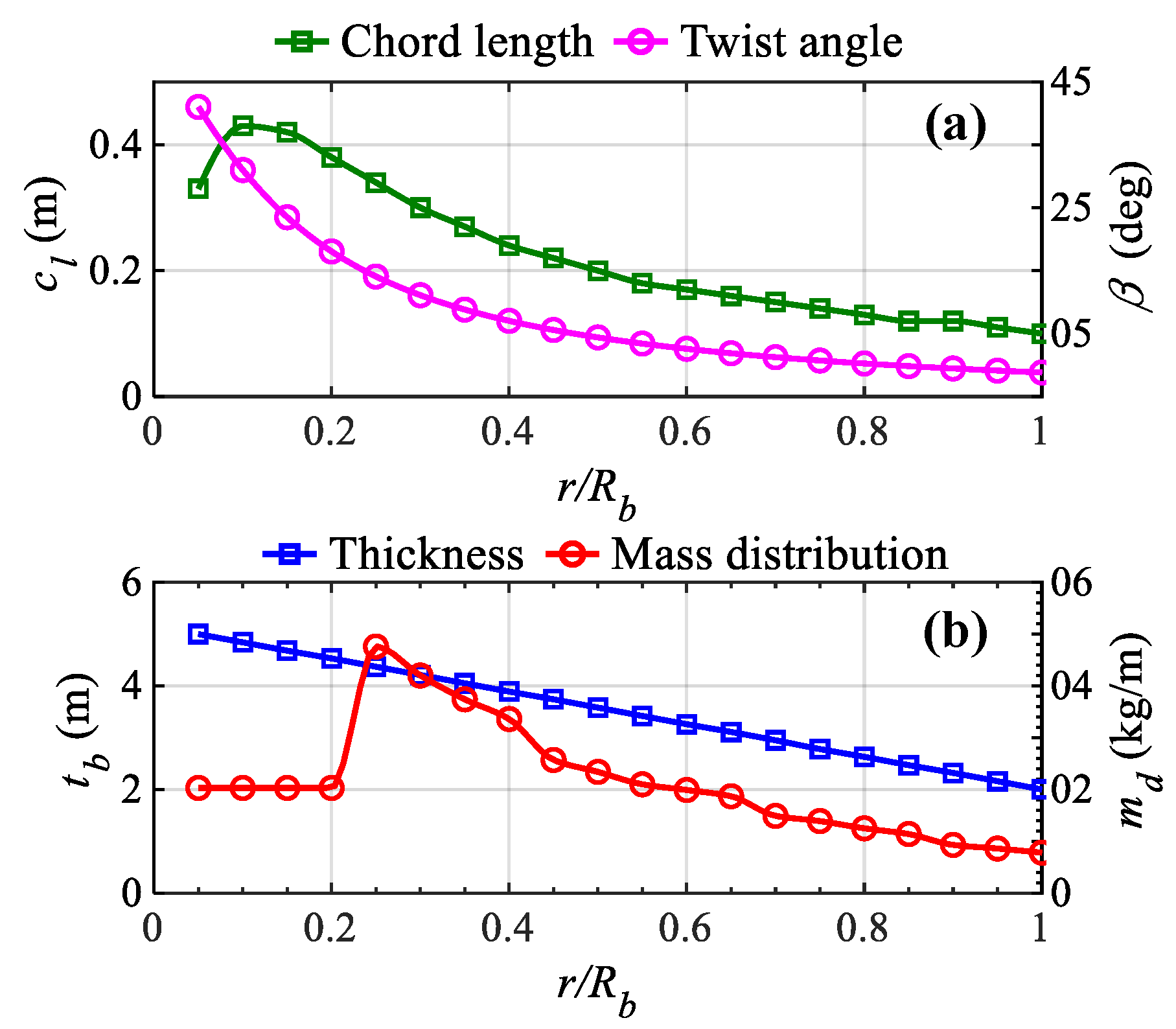

4.1. Geometric Models

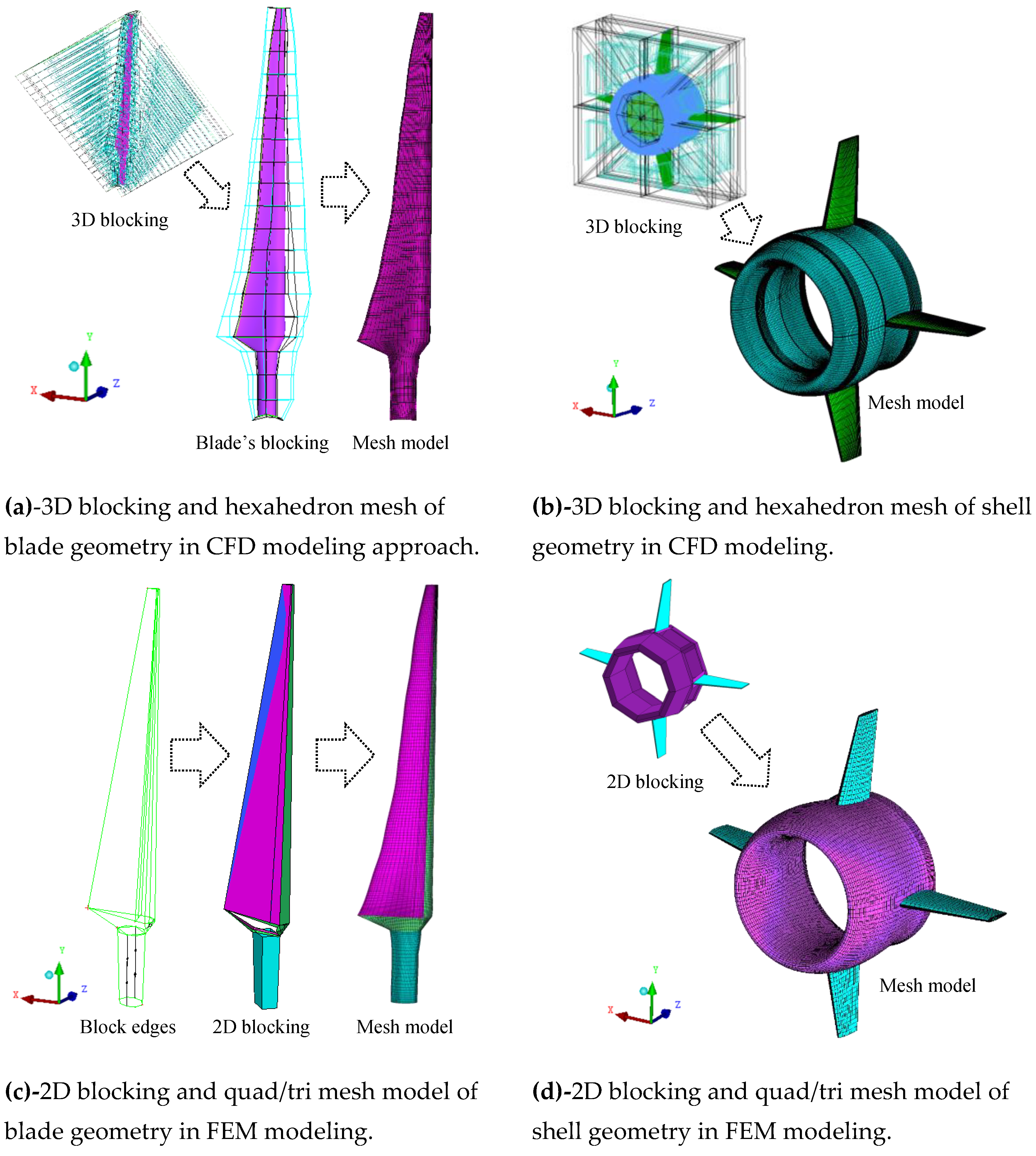

4.2. Mesh Models

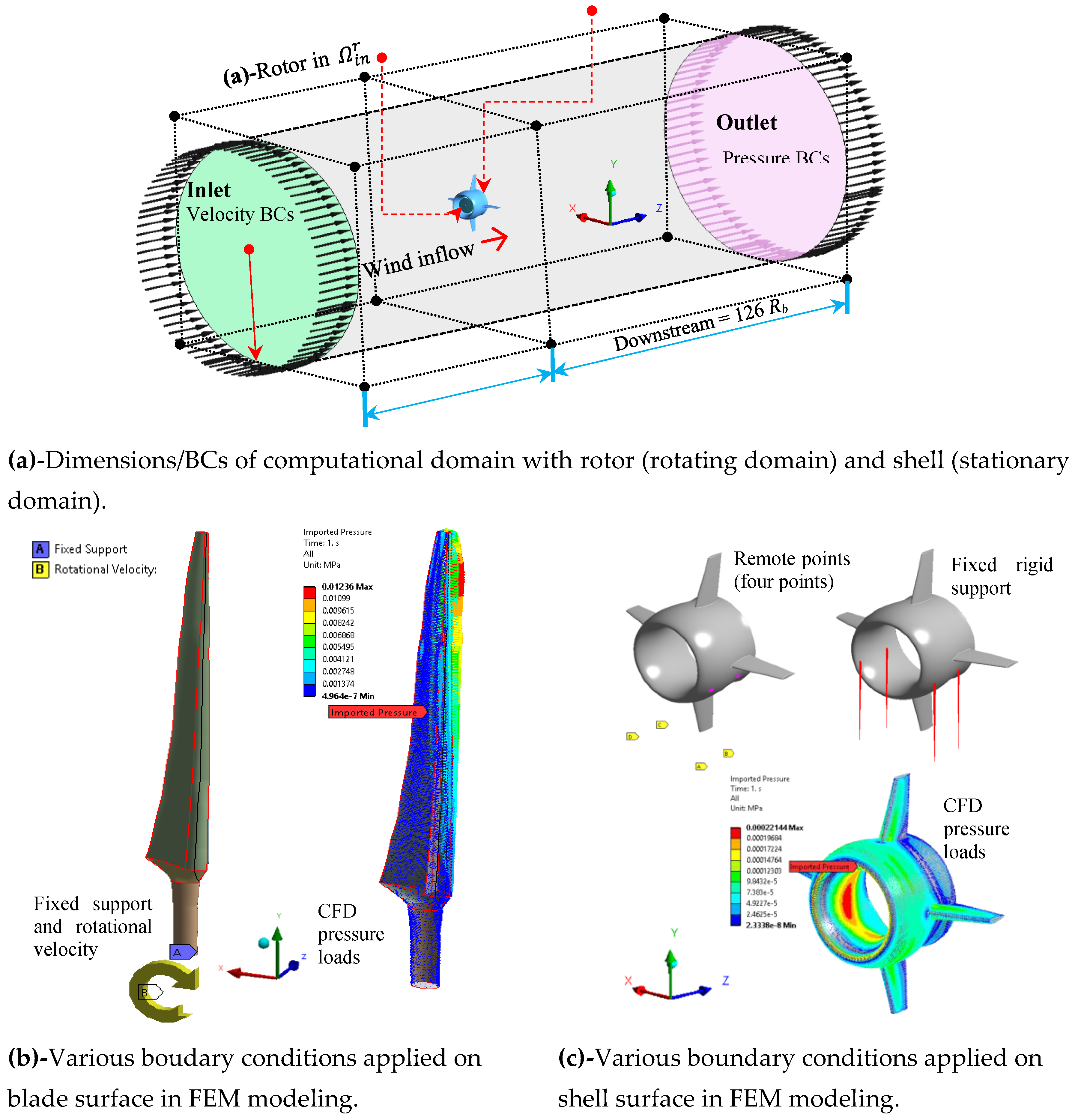

4.3. Boundary Conditions (BCs) and Domains

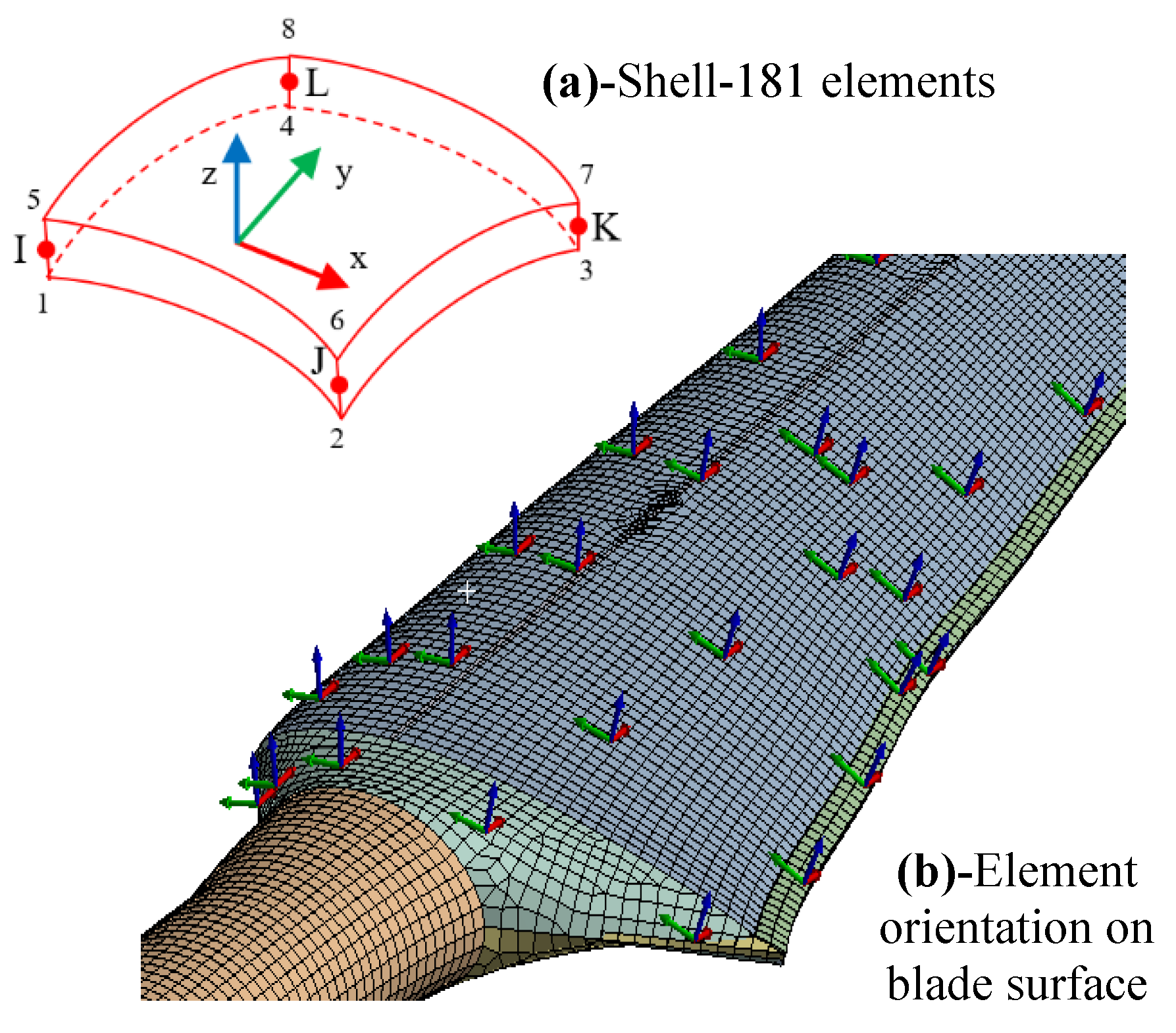

4.4. Shell Elements and Material Distribution

4.5. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

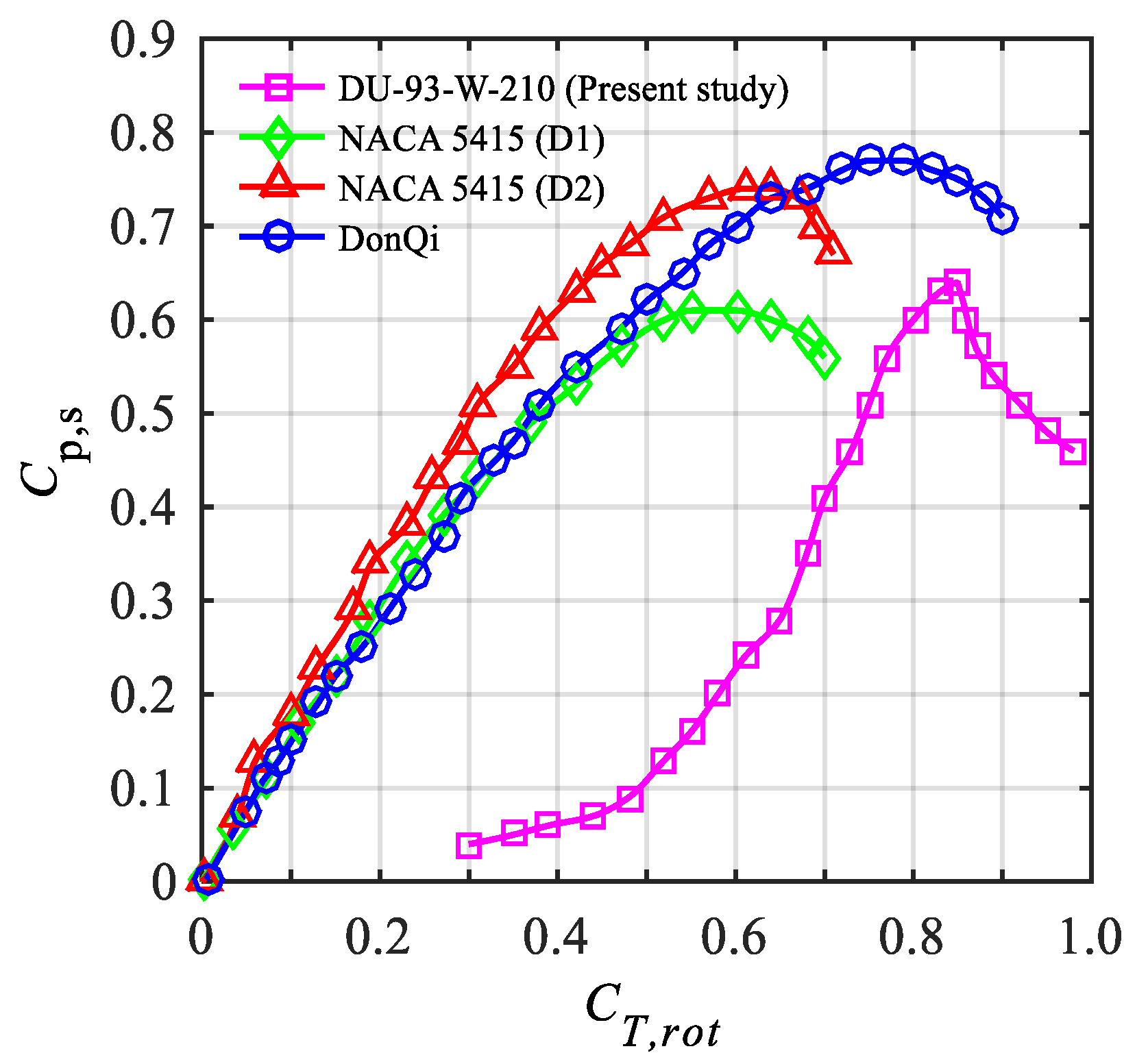

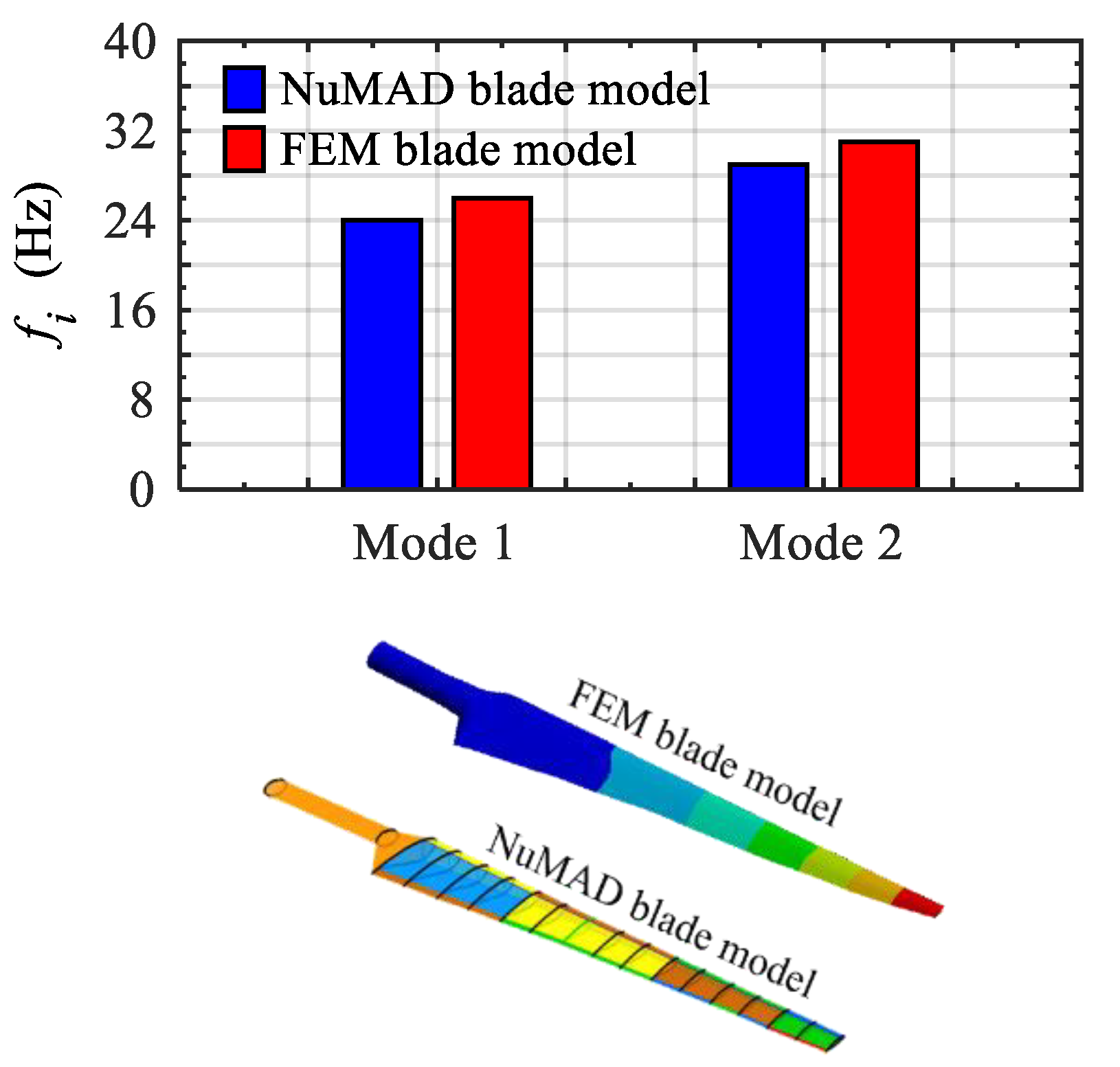

5.1. Model Validation

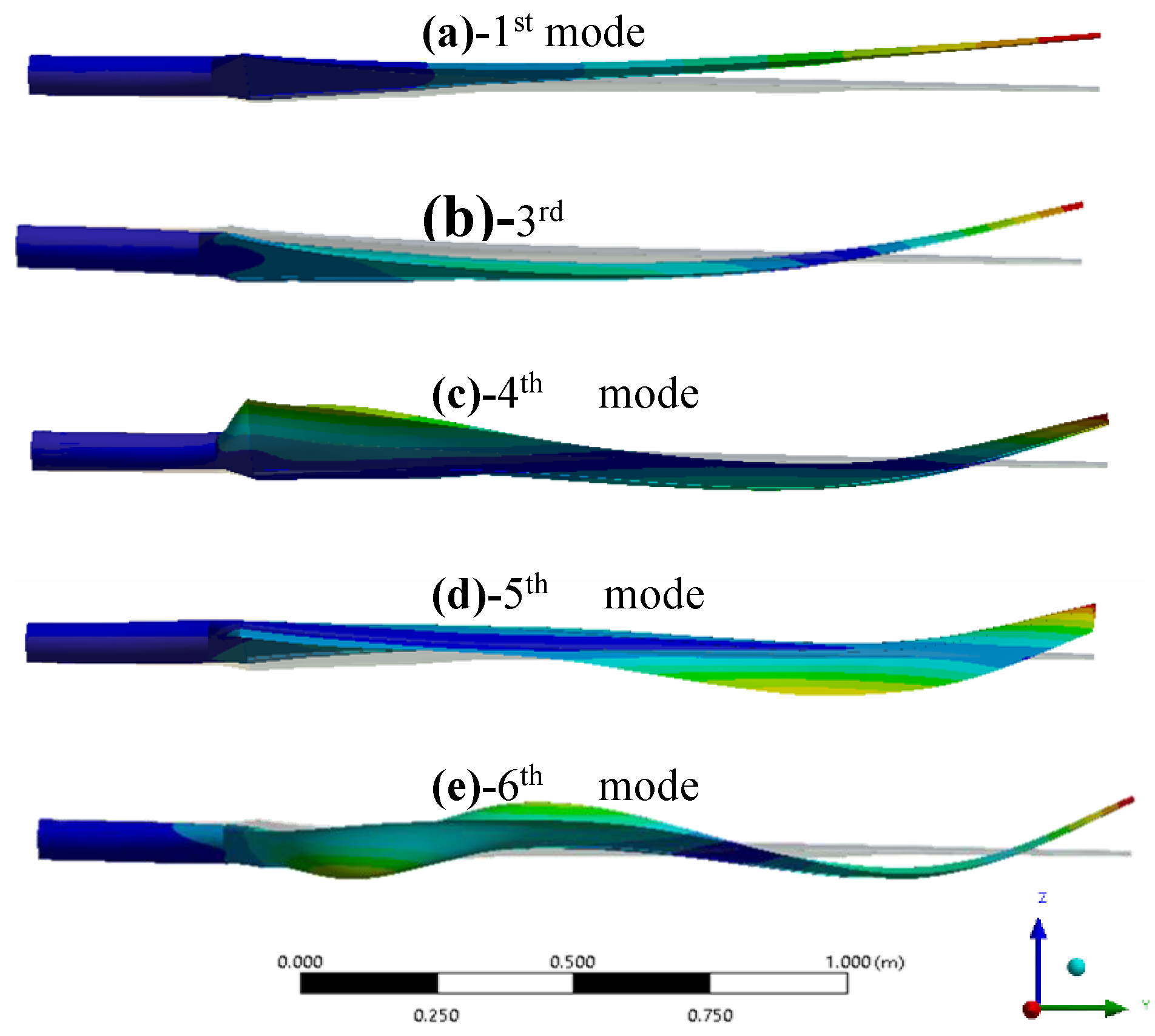

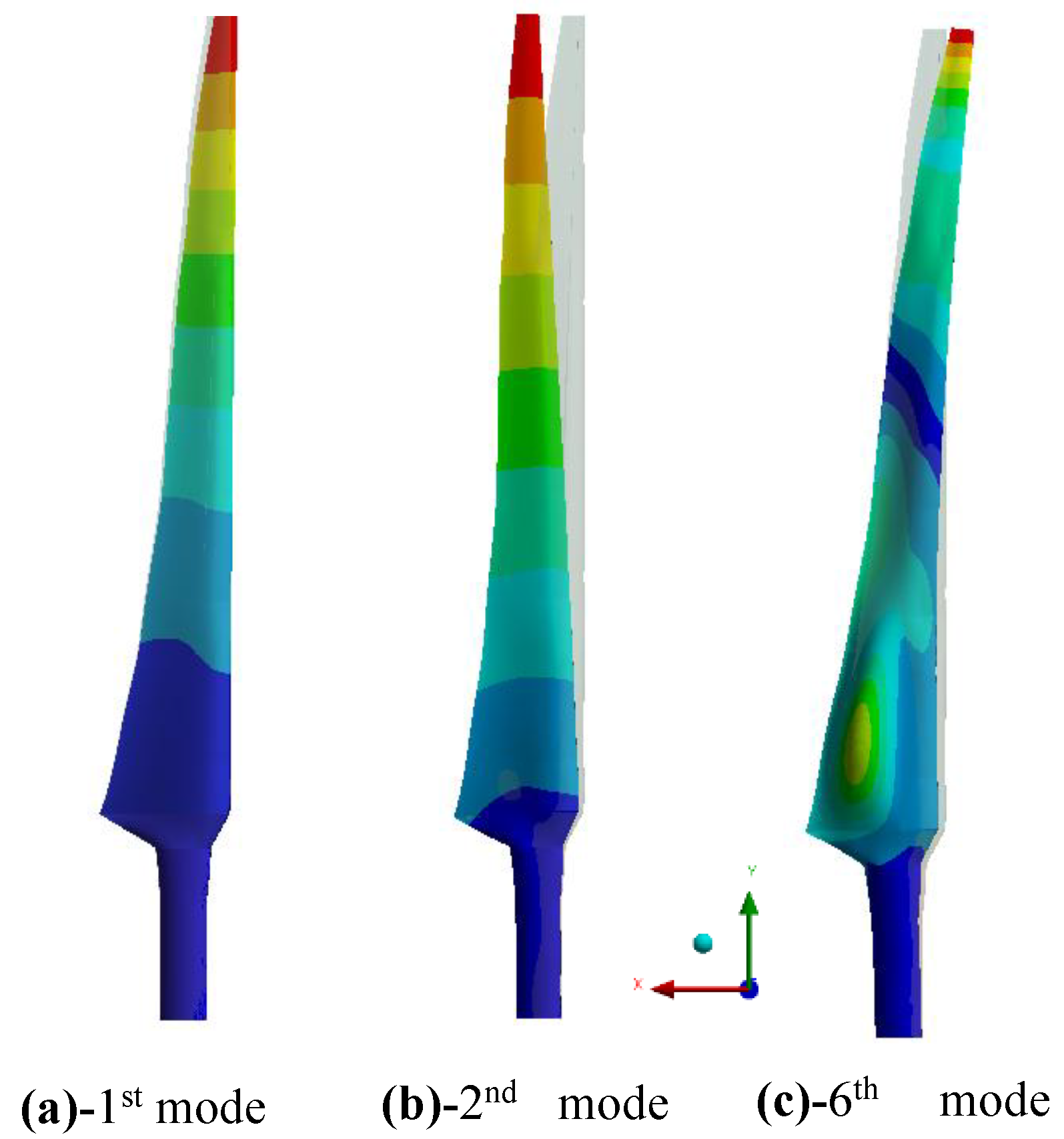

5.2. Mode Shapes of Blade

5.3. Aerodynamic Forces and Augmentation

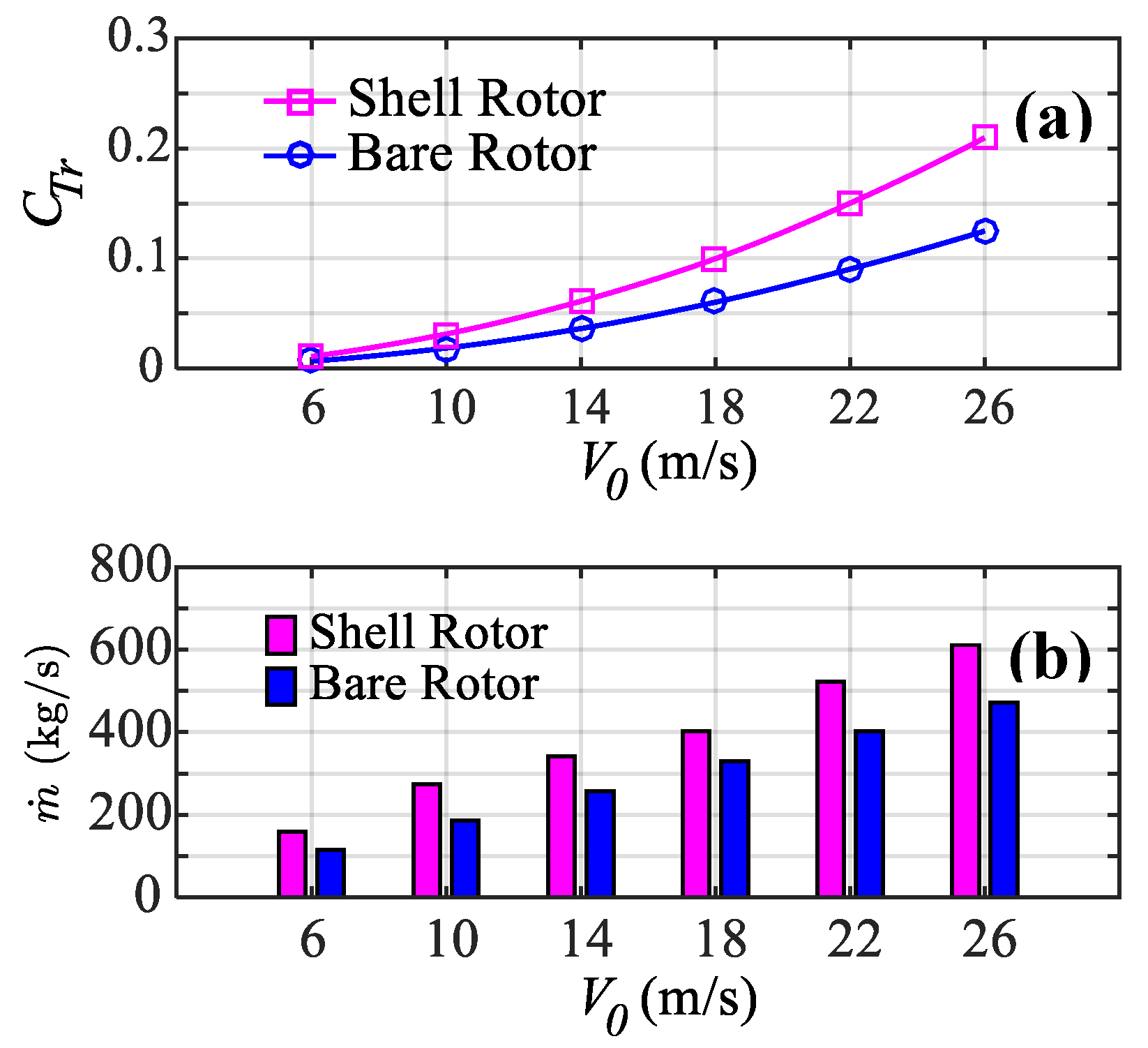

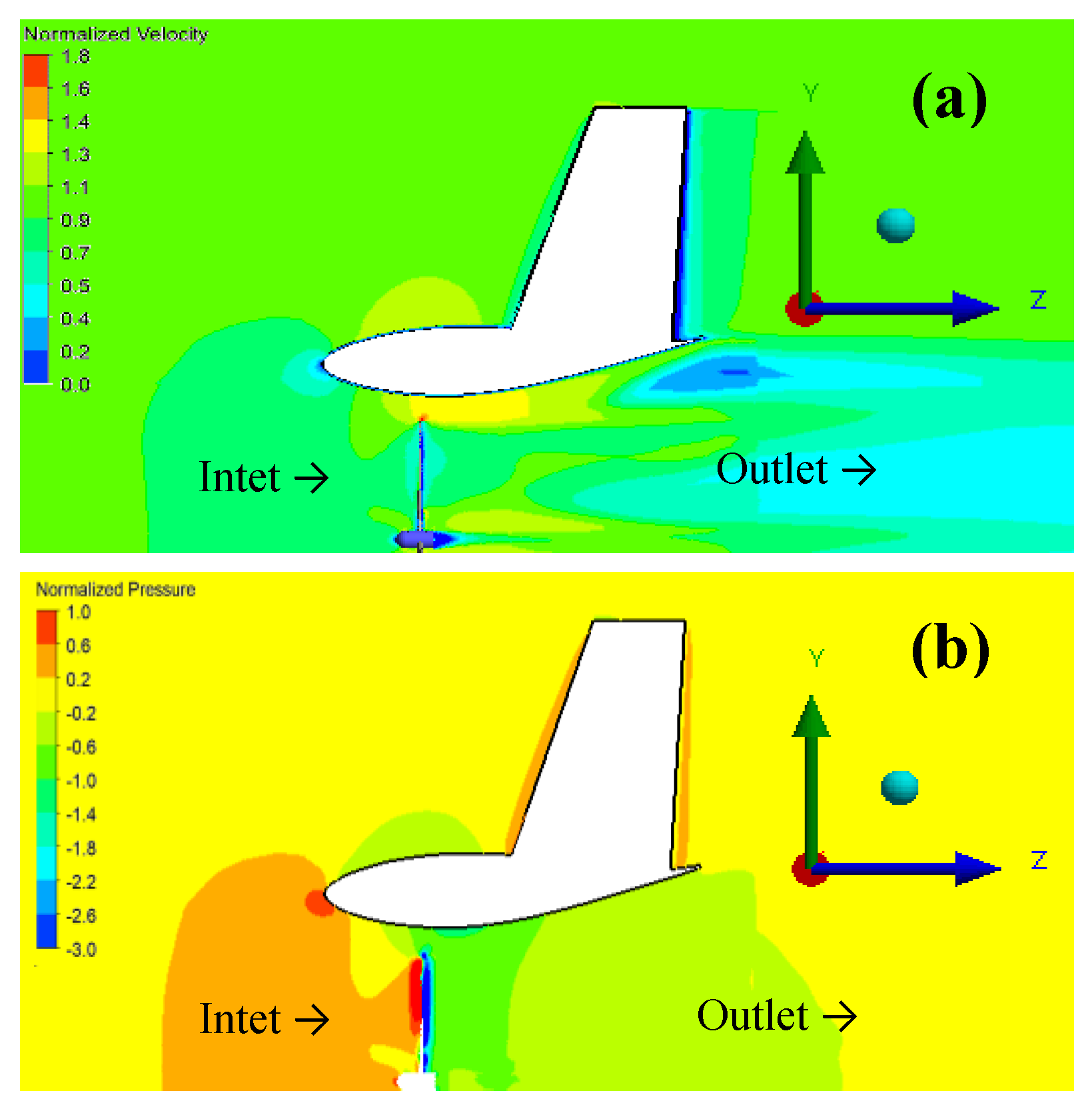

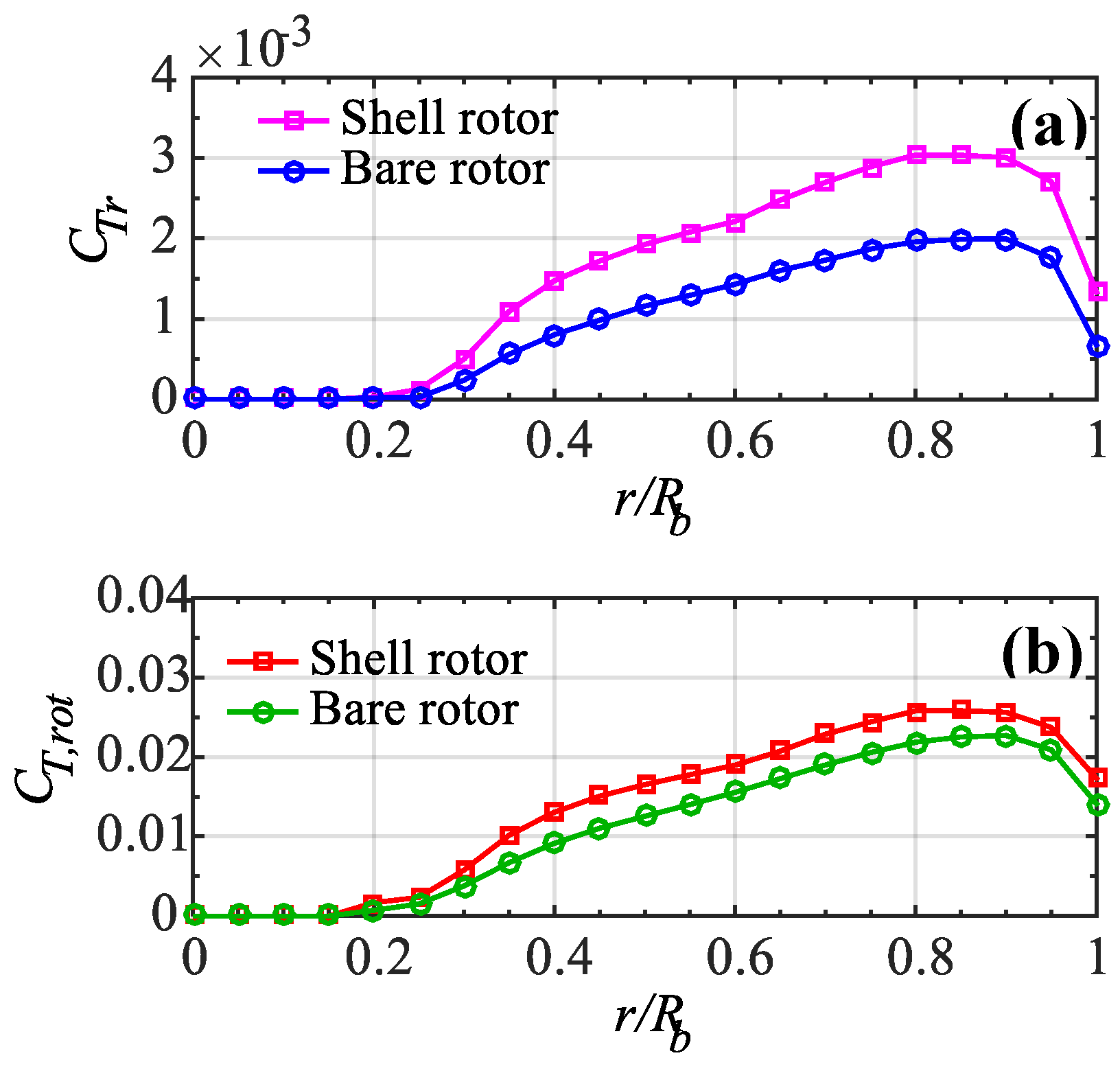

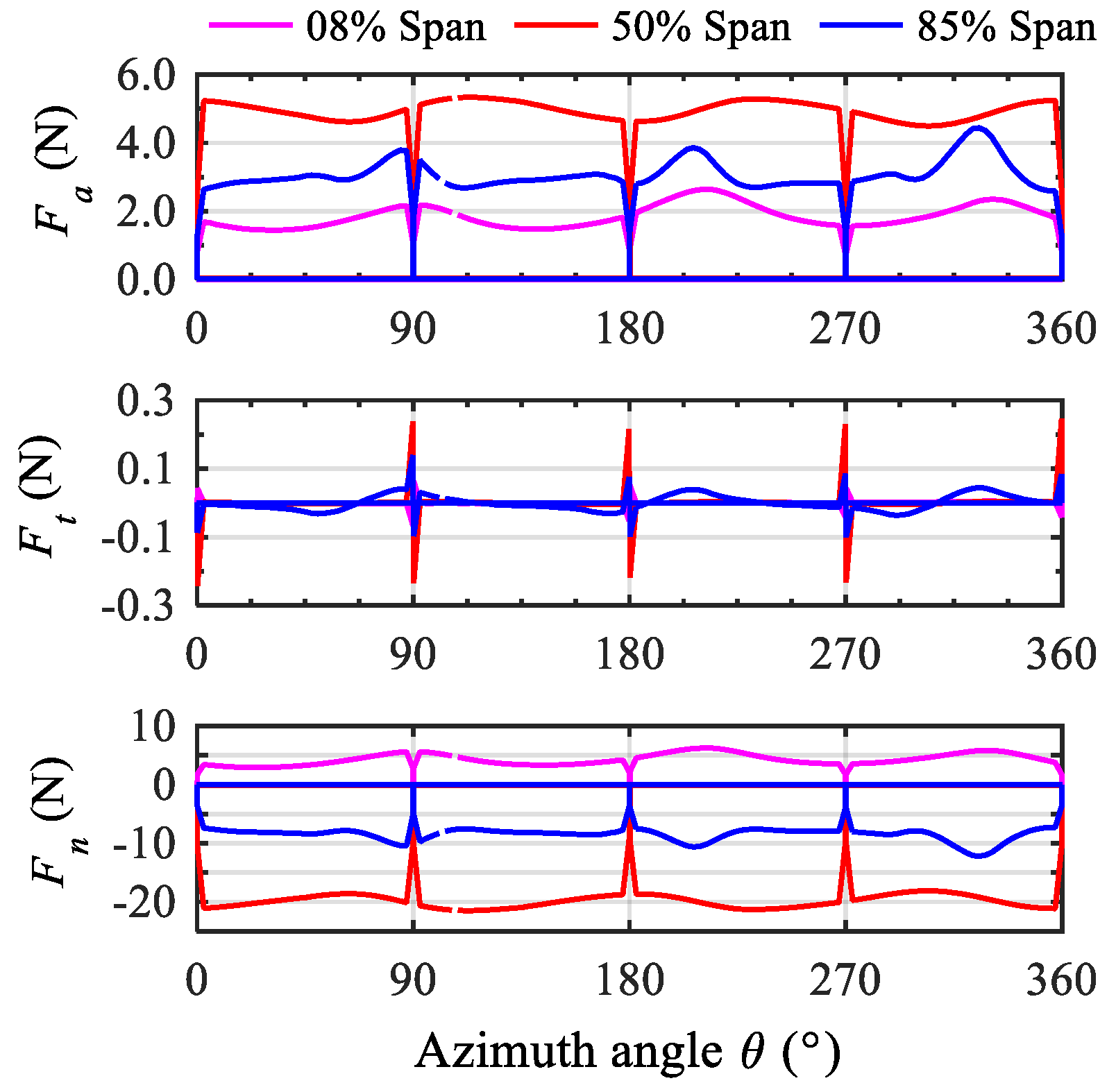

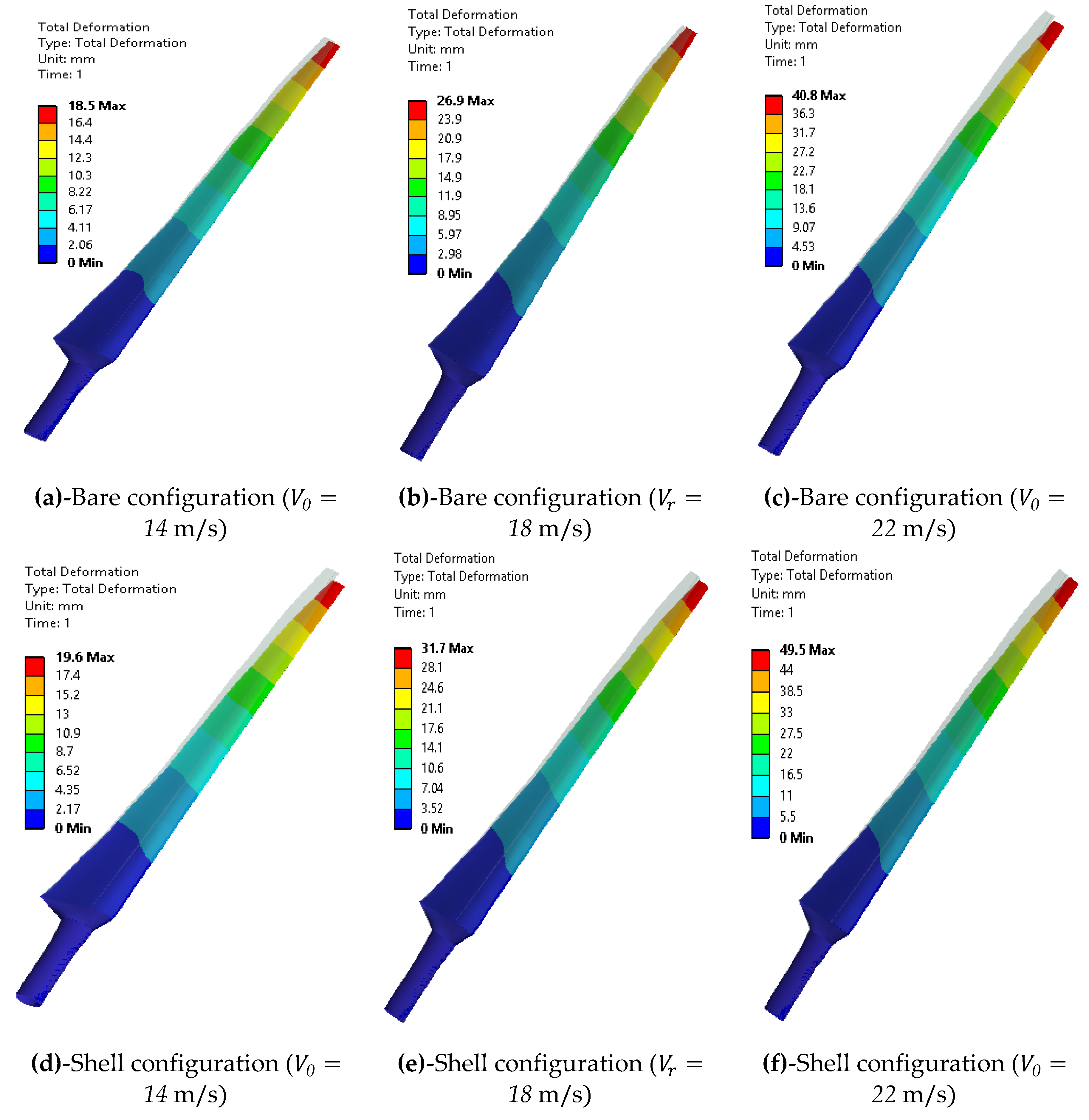

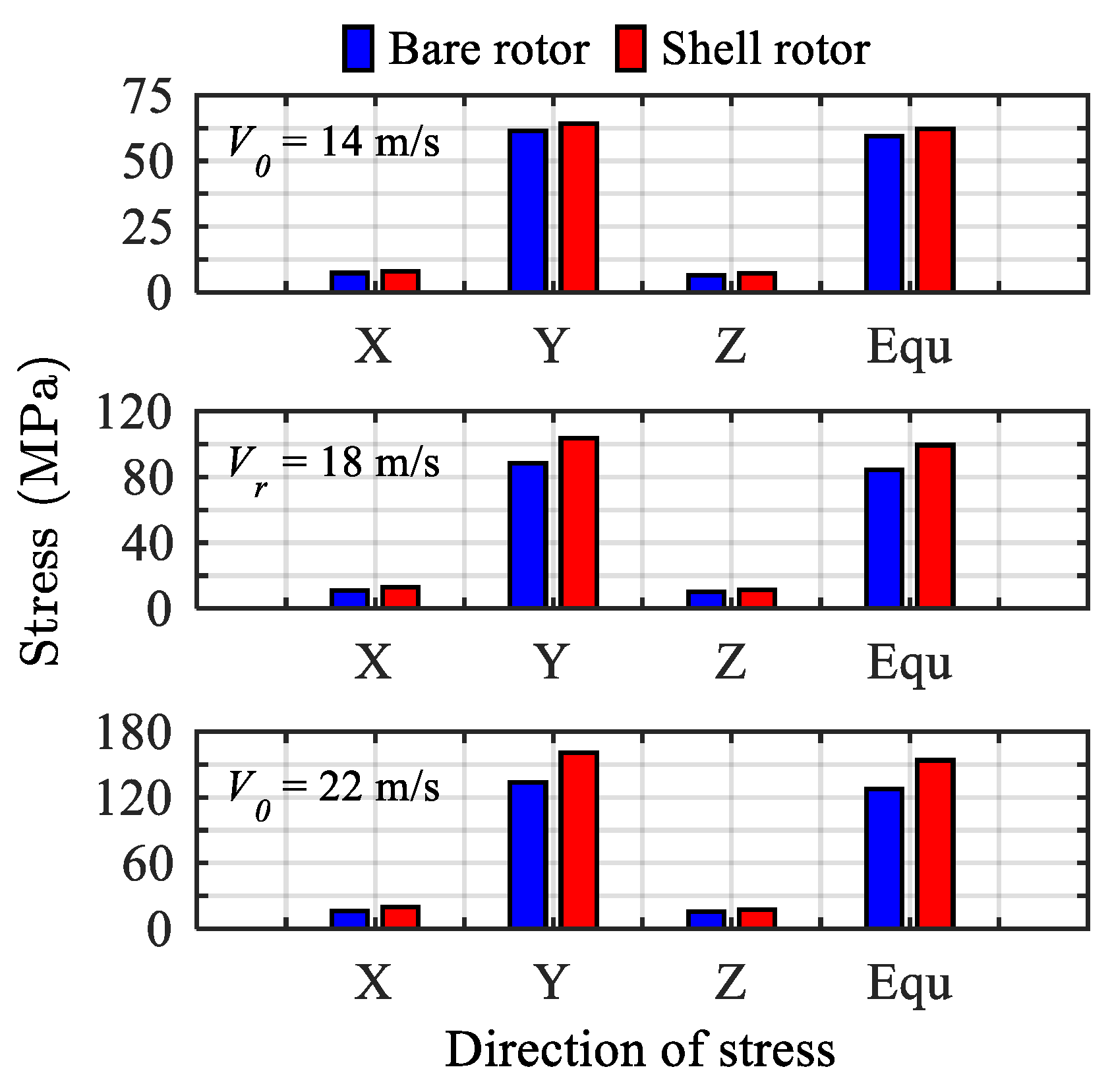

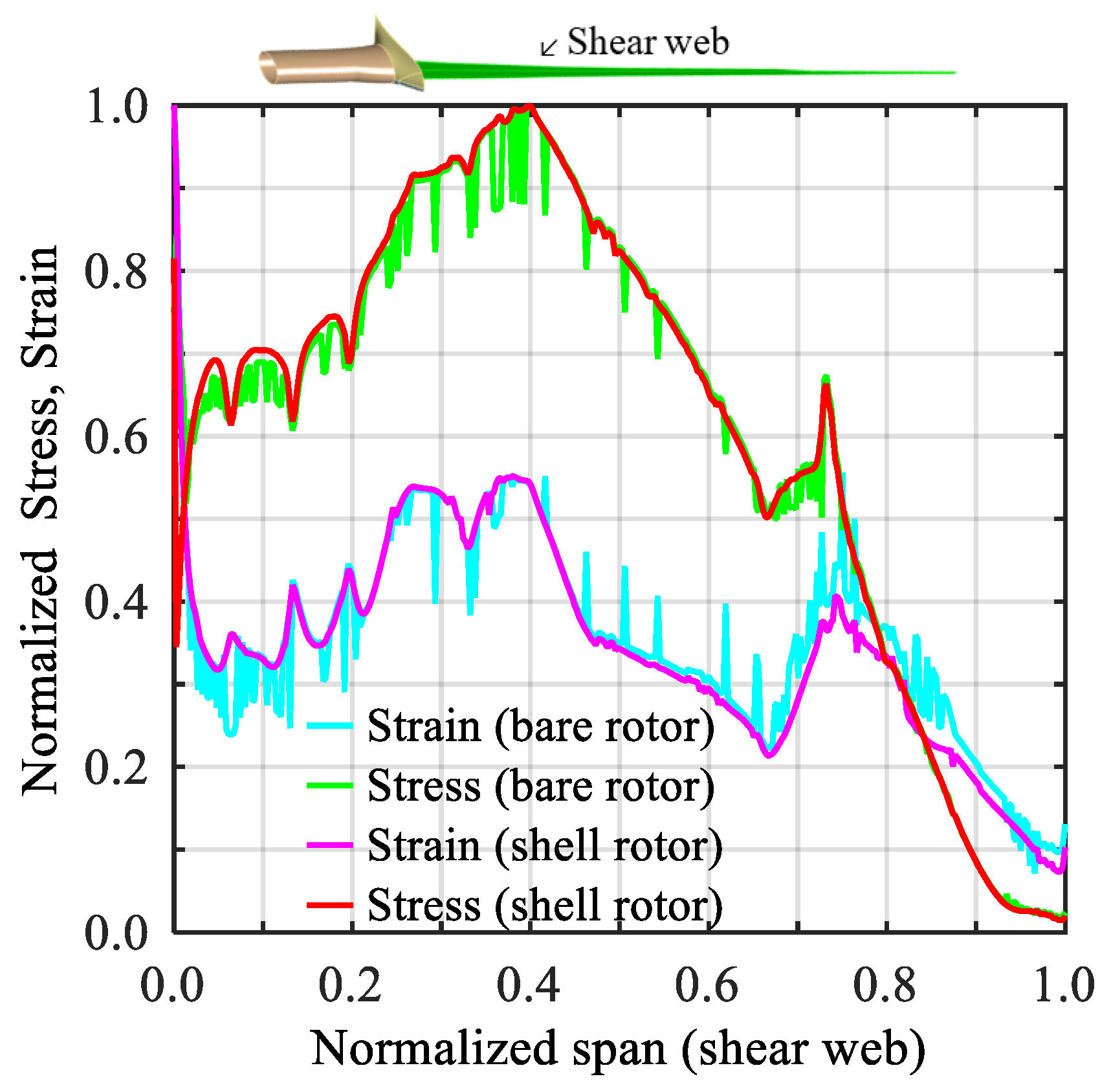

5.4. Aeroelastic Structural Responses

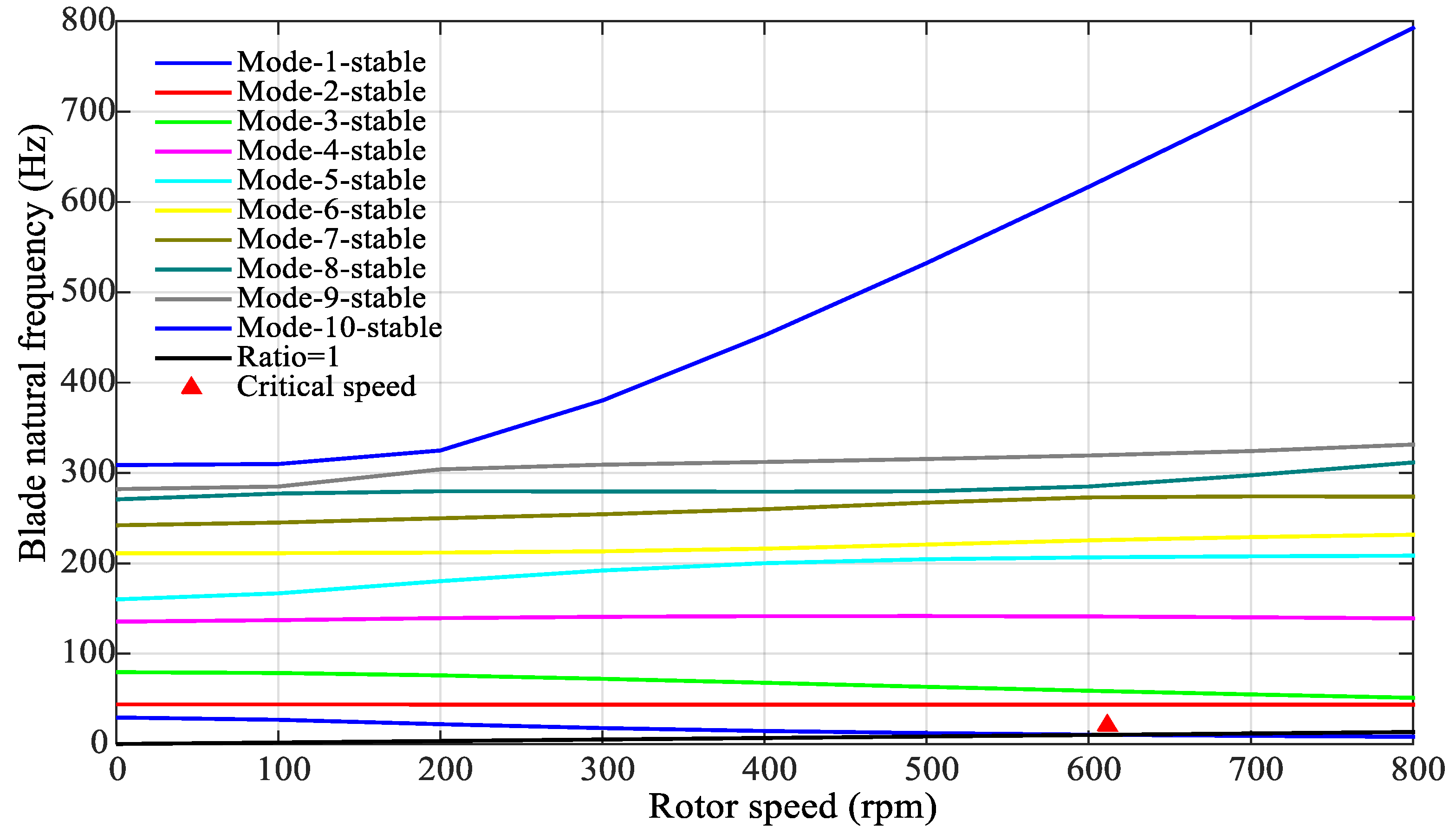

5.5. Operational Stability

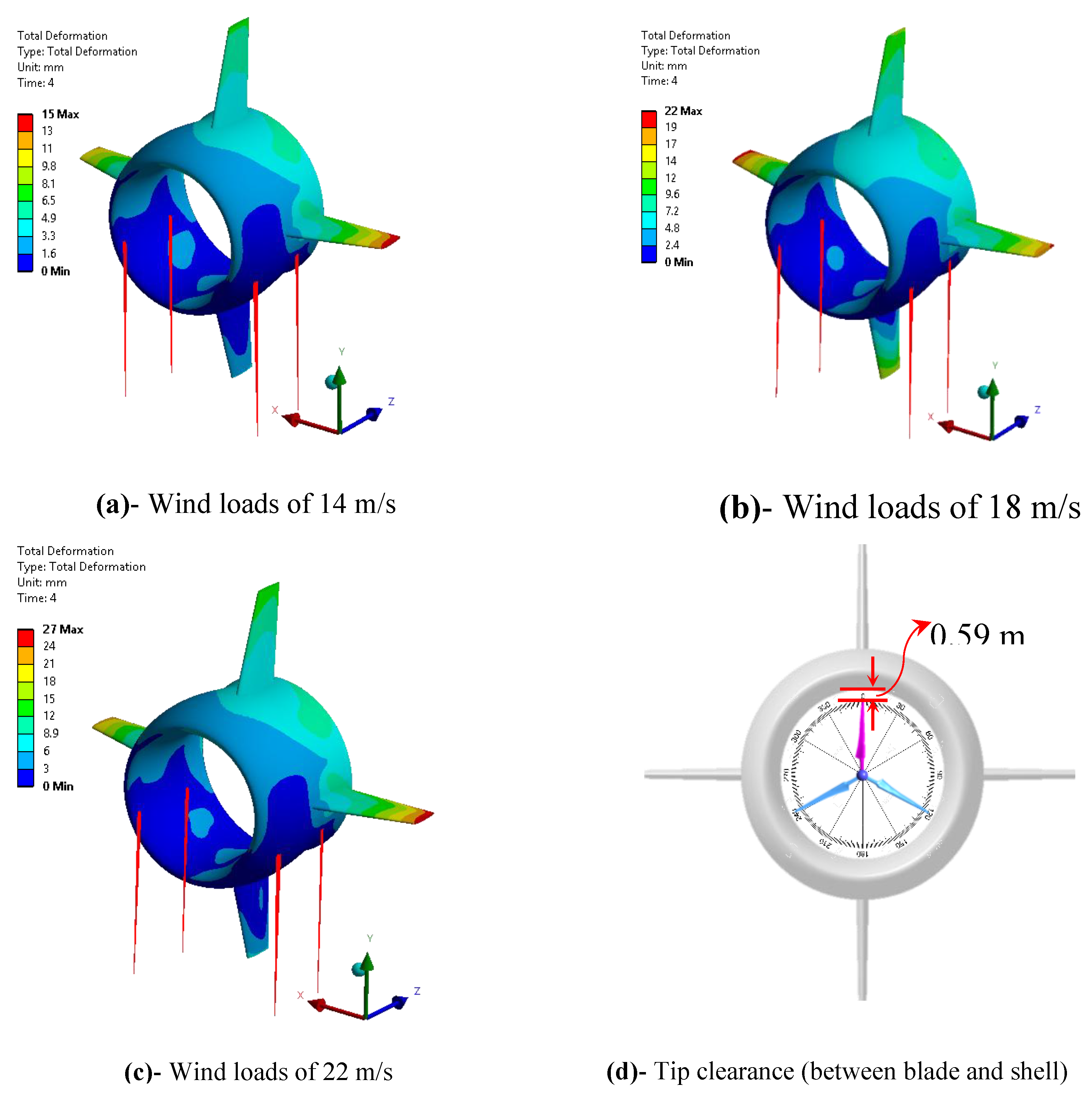

5.6. Deformation of Shell

6. Conclusions

- The augmentation effects of the shell around the rotor yielded a substantial gain of 66% in generated torque as compared to the bare rotor. Conversely, the impact of the shell exerted a higher aerodynamic force on the rotor blades in the shell configuration. Thus, a trade-off between performance enhancement and the structural integrity of AWT is mandatory while operating at a high altitude.

- The blade structure reinforced by a shear web showed larger tip deflections (18% increment) in shell configuration than that of the bare rotor under rated conditions. This implies that the maximum tip deflection (~ 32 mm) at a rated wind speed of , indicating that the blade is least vulnerable to experience a strike with the surrounding structure. The results further revealed that the tip deflection increased by an average of 47% corresponding to an increment of 4 m/s in the wind speed.

- The maximum stresses built in the orthotropic blade were examined to be 160 MPa, which are well below the material strength limits of the composite. Additionally, there was no discernible material failure observed during non-linear static structural analysis. The rotational speed of the rotor was found to be quite stable and reasonably safe at a rated condition of 446 rpm.

- The predicted result of the FEM of the shell also ensured the functional operability of the rotor within the design requirement by indicating a limited deformation (~ 22 mm) of the shell surface. Overall the one-way FSI analysis is the preferable choice to evaluate the aerodynamic loads and non-linear structural responses using a dedicated CFD module coupled with the FEM module.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| shell exit area [ | ||

| shell area at rotor plane [ | ||

| power coefficient of shell rotor | ||

| power coefficient | ||

| thrust coefficient of rotor | ||

| torque coefficient of rotor | ||

| Young’s modulus | ||

| thrust force | ||

| axial force | ||

| force of buoyancy | ||

| normal force | ||

| tangential force | ||

| shear modulus | ||

| number of blades | ||

| rates power | ||

| total generated power | ||

| blade radius | ||

| mechanical torque | ||

| rated wind speed | ||

| chord length | ||

| natural frequency | ||

| mass flow rate | ||

| mass per unit length | ||

| thickness of shell-181 element | ||

| inner rotating domain | ||

| outer stationary domain | ||

| equivalent strain | ||

| rated tip speed ratio | ||

| Poisson’s ratio | ||

| air density at high altitudes | ||

| equivalent stress | ||

| altitude | ||

| wind speed | ||

| local radius | ||

| twist angle | ||

| azimuth rotation | ||

| tip speed ratio | ||

| density | ||

| angular speed | ||

| Stress | ||

| Young modulus | ||

| Strain | ||

| Cauchy stress tensor | ||

| Body force | ||

| Dispalcement | ||

| Shear modulus | ||

| Abbreviations | ||

| 2D | Two-dimensional | |

| 3D | Three-dimensional | |

| AWE | Airborne Wind Energy | |

| AWES | Airborne Wind Energy System | |

| AWT | Airborne Wind Turbine | |

| BAT | Buoyant Airborne Turbine | |

| BC | Boundary Condition | |

| BEM | Blade Element Momentum (model/theory) | |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics | |

| DAWT | Diffuser Augmented Wind Turbine | |

| DU | Delft University | |

| DWT | Ducted Wind Turbine | |

| FEM | Finite Element Method | |

| FoS | Factor of Safety | |

| FSI | Fluid–Structure Interaction | |

| FVM | Finite Volume Method | |

| HAWT | Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine | |

| NACA | National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics | |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory | |

| NuMAD | Numerical Manufacturing And Design | |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (equations) | |

| rpm | Revolutions per Minute | |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport | |

| TSR | Tip Speed Ratio | |

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbine | |

References

- Watson, S.; Moro, A.; Reis, V.; Baniotopoulos, C.; Barth, S.; Bartoli, G.; Bauer, F.; Boelman, E.; Bosse, D.; Cherubini, A.; et al. Future Emerging Technologies in the Wind Power Sector: A European Perspective. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 113, 109270. [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, A.; Papini, A.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. Airborne Wind Energy Systems: A Review of the Technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 1461–1476. [CrossRef]

- Bechtle, P.; Schelbergen, M.; Schmehl, R.; Zillmann, U.; Watson, S. Airborne Wind Energy Resource Analysis. Renew Energy 2019, 141, 1103–1116. [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.L.; Delle Monache, L.; Rife, D.L. Airborne Wind Energy: Optimal Locations and Variability. Renew Energy 2014, 64, 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.L.; Caldeira, K. Global Assessment of High-Altitude Wind Power. Energies (Basel) 2009, 2, 307–319. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.C.; Bhatti, T.S.; Kothari, D.P. On Some of the Design Aspects of Wind Energy Conversion Systems. Energy Convers Manag 2002, 43, 2175–2187. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin W. Glass US Patent for Lighter-Than-Aircraft for Energy Producing Turbines (Patent No. US 9000605 B2) 2015, 2, 22.

- Hansen, M.O.L.; Sørensen, J.N.; Voutsinas, S.; Sørensen, N.; Madsen, H.A. State of the Art in Wind Turbine Aerodynamics and Aeroelasticity. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2006, 42, 285–330. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Kim, M.H. Effect of Rotor Tip Clearance on the Aerodynamic Performance of an Aerofoil-Based Ducted Wind Turbine. Energy Convers Manag 2019, 201, 112186. [CrossRef]

- Khamlaj, T.A.; Rumpfkeil, M.P. Analysis and Optimization of Ducted Wind Turbines. Energy 2018, 162, 1234–1252. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yoshida, S. An Extension of the Generalized Actuator Disc Theory for Aerodynamic Analysis of the Diffuser-Augmented Wind Turbines. Energy 2015, 93, 1852–1859. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.O.L.; Sørensen, N.N.; Flay, R.G.J. Effect of Placing a Diffuser around a Wind Turbine. Wind Energy 2000, 3, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; El Damatty, A.A.; Dai, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Lu, W. Parametric Study of the Quasi-Static Response of Wind Turbines in Downburst Conditions Using a Numerical Model. Eng Struct 2022, 250, 113440. [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.J.; Chen, P.W.; Wang, W.C. Aerodynamic Design and Analysis of a 10 KW Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine for Tainan, Taiwan. Clean Technol Environ Policy 2016, 18, 1151–1166. [CrossRef]

- Aranake, A.C.; Lakshminarayan, V.K.; Duraisamy, K. Computational Analysis of Shrouded Wind Turbine Configurations Using a 3-Dimensional RANS Solver. Renew Energy 2015, 75, 818–832. [CrossRef]

- Dighe, V. V.; de Oliveira, G.; Avallone, F.; van Bussel, G.J.W. Characterization of Aerodynamic Performance of Ducted Wind Turbines: A Numerical Study. Wind Energy 2019, 22, 1655–1666. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.A.H.; Kosasih, B. Flow Analysis of Shrouded Small Wind Turbine with a Simple Frustum Diffuser with Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2014, 125, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Kim, M.H. Aerodynamic Performance Analysis of an Airborne Wind Turbine System with NREL Phase IV Rotor. Energy Convers Manag 2017, 134, 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Kim, M.H. Aerodynamic Analysis of an Airborne Wind Turbine with Three Different Aerofoil-Based Buoyant Shells Using Steady RANS Simulations. Energy Convers Manag 2018, 177, 233–248. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.S.; Kim, M. Quantifying Impacts of Shell Augmentation on Power Output of Airborne Wind Energy System at Elevated Heights. Energy 2022, 239, 121839. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; De Risi, R.; Sextos, A. Finite Element Modeling Optimization of Wind Turbine Blades from an Earthquake Engineering Perspective. Eng Struct 2020, 222, 111105. [CrossRef]

- Santo, G.; Peeters, M.; Van Paepegem, W.; Degroote, J. Effect of Rotor–Tower Interaction, Tilt Angle, and Yaw Misalignment on the Aeroelasticity of a Large Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine with Composite Blades. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 1578–1595. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Quant, R.; Kolios, A. Fluid Structure Interaction Modelling of Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine Blades Based on CFD and FEA. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2016, 158, 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Huque, Z.; Kommalapati, R.; Han, S.E. Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis of NREL Phase VI Wind Turbine: Aerodynamic Force Evaluation and Structural Analysis Using FSI Analysis. Renew Energy 2017, 113, 512–531. [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Piquee, J.; Bucher, P.; Bletzinger, K.U.; Breitsamter, C.; Wüchner, R. Numerical Analysis of an Elasto-Flexible Membrane Blade Using Steady-State Fluid–Structure Interaction Simulations. J Fluids Struct 2021, 106, 103355. [CrossRef]

- Marzec, Ł.; Buliński, Z.; Krysiński, T. Fluid Structure Interaction Analysis of the Operating Savonius Wind Turbine. Renew Energy 2021, 164, 272–284. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.N.; Jaworski, J.W. Strongly-Coupled Aeroelastic Free-Vortex Wake Framework for Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Rotors. Part 2: Application. Renew Energy 2020, 149, 1018–1031. [CrossRef]

- Nejadkhaki, H.K.; Sohrabi, A.; Purandare, T.P.; Battaglia, F.; Hall, J.F. A Variable Twist Blade for Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines: Modeling and Analysis. Energy Convers Manag 2021, 248, 114771. [CrossRef]

- Keprate, A.; Bagalkot, N.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Sen, S. Reliability Analysis of 15MW Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Rotor Blades Using Fluid-Structure Interaction Simulation and Adaptive Kriging Model. Ocean Engineering 2023, 288, 116138. [CrossRef]

- Marzec, L.; Buliński, Z.; Krysiński, T.; Tumidajski, J. Structural Optimisation of H-Rotor Wind Turbine Blade Based on One-Way Fluid Structure Interaction Approach. Renew Energy 2023, 216, 118957. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, G. Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis of Wind Turbine Aerodynamic Loads and Aeroelastic Responses Considering Blade and Tower Flexibility. Eng Struct 2024, 301, 117289. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.S.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.C. A General FSI Framework for an Effective Stress Analysis on Composite Wind Turbine Blades. Ocean Engineering 2024, 291, 116412. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wan, D. Aeroelastic Analysis of Wind Turbine under Diverse Inflow Conditions. Ocean Engineering 2024, 307, 118235. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Bashir, M.; Iglesias, G.; Miao, W.; Yue, M.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, C. Investigation of Aero-Hydro-Elastic-Mooring Behavior of a H-Type Floating Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Using Coupled CFD-FEM Method. Appl Energy 2024, 372, 123816. [CrossRef]

- Alves Ribeiro, J.; Alves Ribeiro, B.; Pimenta, F.; M.O. Tavares, S.; Zhang, J.; Ahmed, F. Offshore Wind Turbine Tower Design and Optimization: A Review and AI-Driven Future Directions. Appl Energy 2025, 397, 126294. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, Q.; Iglesias, G.; Li, C. Advanced Multi-Physics Modeling of Floating Offshore Wind Turbines for Aerodynamic Design and Load Management. Energy Convers Manag 2025, 346, 120437. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, P.; Thomas, M.; Seibi, A.C.; Shekaramiz, M.; Masoum, M.A.S. Fluid-Structure Interaction and Life Prediction of Small-Scale Damaged Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Blades. Results in Engineering 2024, 23, 102388. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, J.; Tan, A.C.C. Deep Learning Enhanced Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis for Composite Tidal Turbine Blades. Energy 2024, 296, 131216. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Cheng, L.; Hu, G.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; et al. A Variable Twist Blade for Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines: Modeling and Analysis. Ocean Engineering 2024, 301, 114771. [CrossRef]

- Hermes, A.; Zahle, F.; Riva, R.; Madsen, J.; Bergami, L.; Skovby, C. High Fidelity Aeroelastic Stability Analysis of Operating Wind Turbines. Renew Energy 2025, 253, 123424. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Kim, M.H. Airborne Wind Turbine Shell Behavior Prediction under Various Wind Conditions Using Strongly Coupled Fluid Structure Interaction Formulation. Energy Convers Manag 2016, 120, 217–228. [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.G.; Xiao, Q.; Allsop, S.; Incecik, A.; Peyrard, C. A Numerical Structural Analysis of Ducted, High-Solidity, Fibre-Composite Tidal Turbine Rotor Configurations in Real Flow Conditions. Ocean Engineering 2021, 233, 109087. [CrossRef]

- Jokar, H.; Vatankhah, R.; Mahzoon, M. Nonlinear Vibration Analysis of Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Blades Using a Modified Pseudo Arc-Length Continuation Method. Eng Struct 2021, 247, 113103. [CrossRef]

- Kampitsis, A.; Kapasakalis, K.; Via-Estrem, L. An Integrated FEA-CFD Simulation of Offshore Wind Turbines with Vibration Control Systems. Eng Struct 2022, 254, 113859. [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, M.; Nuzzo, I.; Caterino, N.; Georgakis, C.T. A Friction-Based Passive Control Technique to Mitigate Wind Induced Structural Demand to Wind Turbines. Eng Struct 2021, 232, 111744. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.S.; Kim, M. Design and Performance Analysis of an Airborne Wind Turbine for High-Altitude Energy Harvesting. Energy 2021, 230, 120829. [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, J.-F. Fluid–Structure Interaction; John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2015; ISBN 9781119952275.

- ANSYS CFX- User Guide, Release 16.1 2015.

- Patankar, S. V. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow, Series in Computational Methods in Mechanics and Thermal Sciences; 1980; ISBN 978-0891165224 0.

- H K Versteeg and W Malalasekera An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics; Pearson Education Limited, 2007; ISBN 9780131274983.

- Menter, F.R. Zonal Two Equation K-ω, Turbulence Models for Aerodynamic Flows. In Proceedings of the 24th Fluid Dynamics Conference, July 6-9, 1993, Orlando, Florida, AIAA-93-2906; 1993.

- Rezaeiha, A.; Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B. On the Accuracy of Turbulence Models for CFD Simulations of Vertical Axis Wind Turbines. Energy 2019, 180, 838–857. [CrossRef]

- 1 2015.

- Akhtar S. Khan, S.H. General Principles. In Continuum Theory of Plasticity; 1995; p. 440.

- Liu, J. min; Lu, C. jing; Xue, L. ping Investigation of Airship Aeroelasticity Using Fluid-Structure Interaction. Journal of Hydrodynamics 2008, 20, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa, A.J.; Gil, A.; Quintero, P.; Cremades, A. On the Effects of Orthotropic Materials in Flutter Protection of Wind Turbine Flexible Blades. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2022, 227, 105055. [CrossRef]

- Eslami, H.; Jayasinghe, L.B.; Waldmann, D. Nonlinear Three-Dimensional Anisotropic Material Model for Failure Analysis of Timber. Eng Fail Anal 2021, 130, 105764. [CrossRef]

- Tangier, J.L.; Somers, D.M. NREL Airfoil Families for HAWTs; 1995;

- Hansen, M.O.L. Sources of Loads on a Wind Turbine. In Aerodynamics of Wind Turbines Aerodynamics; Earthscan, 2015; pp. 139–146 ISBN 9781844074389.

- Bontempo, R.; Manna, M. Performance Analysis of Open and Ducted Wind Turbines. Appl Energy 2014, 136, 405–416. [CrossRef]

- Bontempo, R.; Manna, M. Effects of the Duct Thrust on the Performance of Ducted Wind Turbines. Energy 2016, 99, 274–287. [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Resor, B. Numerical Manufacturing and Design Tool (NuMAD V2. 0) for Wind Turbine Blades: User’s Guide; 2012;

- Bir, G.S. User’s Guide to PreComp (Pre-Processor for Computing Composite Blade Properties); 2005;

- Bir, G.S. User’s Guide to BModes (Software for Computing Rotating Beam Coupled Modes); 2007;

- Pagnini, L.C.; Piccardo, G. Modal Properties of a Vertical Axis Wind Turbine in Operating and Parked Conditions. Eng Struct 2021, 242, 112587. [CrossRef]

| Rotor specification | Shell specifications | ||||||

| Description | Parameter | Value | Units | Description | Parameter | Value | Units |

| Rated power output | 30 | kW | Payload (rotor + shell) | 75 | kg | ||

| Power coefficient | 0.48 | – | Generator + drivetrain | 120 | kg | ||

| Blade radius | 2.51 | m | Helium gas weight | 35 | kg | ||

| Rated TSR | 6.5 | – | Factor of safety | 1.2 | – | ||

| Wind speed (rated) | 18 | m/s | Total downward force | 2.70 | kN | ||

| Air density (400 m) | 1.179 | kg/m3 | Shell volume | 155 | m3 | ||

| Generator efficiency | 92 | % | Gravitational force | 9.81 | m/s2 | ||

| Material | ρ | Ex | Ey | Ez | Gxy | Gyz | Gxz | νxy | νyz | νxz |

| Units | (Kg/m3) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Blade’s material | 1500 | 110 | 7.60 | 7.60 | 5.45 | 2.95 | 2.95 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| Shell’s material | 1440 | 124 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.36 | - | - |

| CFD mesh results of rotor blades | |||||

| Total mesh elements → | 12 million | 15 million | 17 million | 20 million | % diff |

| Parameter (units)↓ | mesh 1 | mesh 2 | mesh 3 | mesh 4 | |

| Mechanical torque (Nm) | 533 | 548 | 567 | 572 | 0.88 |

| Single iteration time (s) | 145 | 188 | 224 | 249 | 10.57 |

| CFD mesh results of shell | |||||

| Total mesh elements → | 07 million | 08 million | 09 million | 10 million | % diff |

| Parameter (units)↓ | mesh 1 | mesh 2 | mesh 3 | mesh 4 | |

| Axial force (N) | 668 | 677 | 685 | 691 | 0.87 |

| Single iteration time (s) | 331 | 343 | 350 | 368 | 5.01 |

| Mesh elements → | 22,973 | 36,626 | 74,404 | 1,67,065 | % diff |

| Natural frequency (units) mode ↓ | mesh 1 | mesh 2 | mesh 3 | mesh 4 | |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 1 | 30.50 | 30.54 | 29.36 | 29.55 | 0.63 |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 2 | 45.81 | 45.84 | 43.93 | 44.18 | 0.58 |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 3 | 79.43 | 79.49 | 79.52 | 79.83 | 0.39 |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 4 | 134.57 | 134.61 | 135.41 | 135.64 | 0.16 |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 5 | 160.17 | 160.24 | 160.05 | 160.37 | 0.19 |

| Natural frequency (Hz) mode 6 | 208.42 | 208.54 | 211.06 | 211.54 | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).