1. Introduction

As one of the world’s important oil crops, rapeseed (

Brassica napus L.) holds a pivotal position in the edible oil and feed markets. China is the world’s largest producer of rapeseed, accounting for nearly 40% of the global market share. In 2023, China’s total rapeseed production was 16.3174 million tons (CNBS, 2023). In recent years, the rapeseed planting area in Xinjiang, China has steadily increased. Xinjiang is located in the hinterland of the Eurasian continent, with a wide range and large area of land desertification, with a total area of 74.6821 million hectares of desertified land [

1].Soil desertification and drought stress have led to a reduction of approximately 3.5 million tons in cereal crop yields in Xinjiang, with a yield loss rate of about 8% [

2]. In the past three years, there has been a shortage of forage in the southern region of Xinjiang, and at the same time, the low forage production in the area has led to an imbalance between supply and demand. With the frequent occurrence of extreme weather, there is an urgent need to adopt soil improvement and agronomic measures to mitigate the adverse effects of the environment on crop yield [

3,

4].

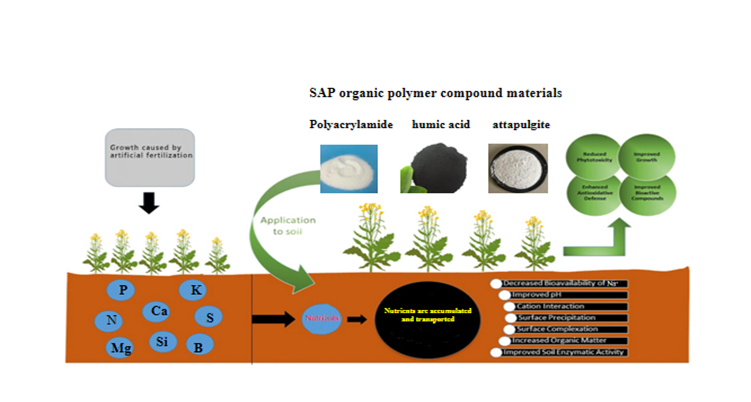

Organic inorganic composite soil conditioners and nutrients are effective measures to enhance crop response to abiotic stress[

5,

6]. Compared with starch and potassium soil amendments, SAP is more effective in alleviating crop growth under adverse conditions and has economic and environmental advantages[

7]. SAP is a high molecular weight polymer with low cross-linking density, insolubility in water, high water swelling ability, and strong water suction. It is widely used as an improver in cereal field crops[

8]. The polymer chain structure of SAP is beneficial for improving the adhesion between easily dispersed particles (1-100nm), promoting the formation of water stable aggregate structures, and improving crop water absorption and utilization efficiency[

9]. In addition, research on the application of SAP in arid areas has found that it can promote the formation of larger aggregate structures in soil, increase soil moisture content, improve pH, electrical conductivity, and soil bulk density, alleviate the negative effects of drought or salt stress on crop growth, increase crop yield, and achieve better results when combined with organic fertilizers[

10,

11]. However, there is a significant difference in its yield increasing effect, which is related to the time SAP is applied to soil, the strength of crop nutrient requirements, as well as microbial and climatic conditions[

12]. The lack of feed raw materials in arid areas is one of the main problems in the development of animal husbandry[

13], and there is an urgent need to find an efficient, low consumption, and sustainable way to supply forage. The emergence of oilseed rape and its supporting planting and utilization technology provides a feasible solution to alleviate the shortage of feed raw materials. The application of compound SAP to improve the growth of oilseed rape under drought stress in the arid northwest region is still unclear.

At present, the main research on improving desertified land in Xinjiang is mostly focused on building new efficient water-saving irrigation projects, establishing sand fixation and compaction projects, and establishing farmland protective forest networks[

14,

15,

16]. There are relatively few studies exploring the comprehensive benefits of crop yield and quality from the perspective of soil improvement. The synergistic mechanism between soil ecosystem, root nutrient absorption and transport, and crop growth is crucial for crop growth[

17,

18,

19]. Microbial activity, changes in soil physicochemical properties, and nutrient accumulation in soil ecosystems can directly reflect the practical application significance of composite SAP for crop growth[

20,

21,

22]. In addition, the comprehensive evaluation based on multiple indicators can scientifically reveal the effect of composite SAP, avoid the bias of human evaluation, and provide scientific reference for objectively analyzing the impact of composite SAP on the growth of oilseed rape in desertified land.

Therefore, we conducted a field experiment on sand fed rapeseed in Hotan, Xinjiang, China to evaluate the effects of applying organic-inorganic composite improved conditioners on the nutrients of various organs, leaf photosynthesis, enzyme activity, and yield and quality of rapeseed fed in desertified land. The aim of this study is to investigate whether organic-inorganic composite amendments reduce drought stress and increase feed rapeseed yield? Secondly, clarify the changes in key indicators of SAP’s effectiveness in improving desertified soil in arid areas. At the same time, the optimal planting plan for oilseed rape in arid and desertified areas using composite SAP to alleviate abiotic stress was proposed. The research results will contribute to the application of composite SAP in arid areas to improve desertified land, enhance the growth of oilseed rape in arid areas, and ensure the feasibility of increasing yield. This will provide new insights for growers to use amendments rationally to improve the growth of oilseed rape in arid areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

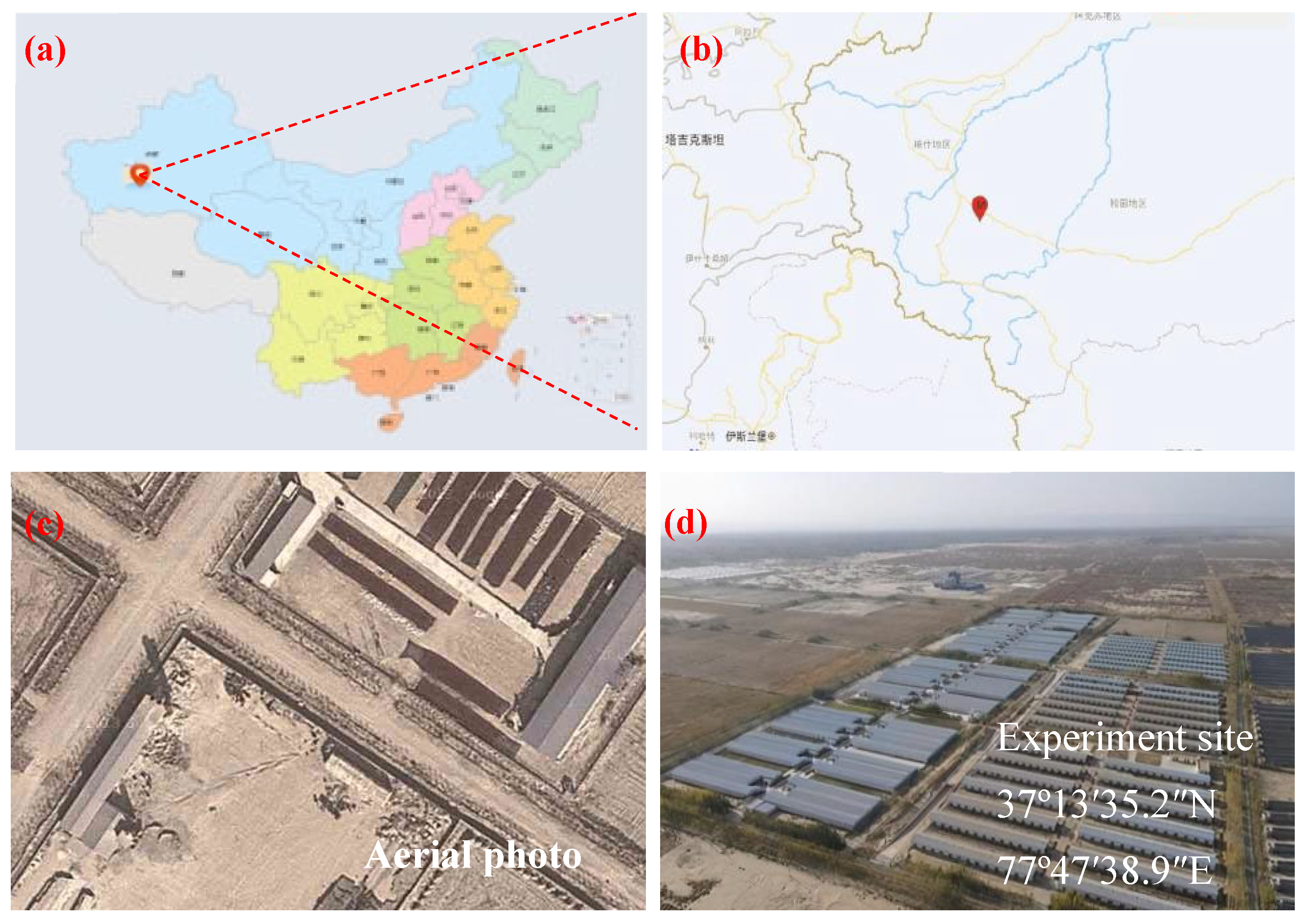

The field experiment was conducted at Pishan Farm in Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China (N37°13′35.2″, E77°47′38.9″) (

Figure 1a, b). The soil type of the experimental site is desertified soil (

Figure 1c, d). Before the experiment began, topsoil (0-20cm) was collected and its basic properties were measured (

Table 1). The climate in this region is a warm temperate arid desert climate in the northern hemisphere, with an average temperature of 11.9℃, an annual sunshine of 2466.8 hours, a frost free period of 190-205 days, an annual average precipitation of 48.2 mm, and an annual average evaporation of 2450 mm.

2.2. Experimental Design

The rapeseed variety selected for this experiment is “Huayouza 62”. In order to verify the optimal application rate of organic-inorganic compound improved conditioner in the field, we first conducted a field experiment in April 2021 using organic fertilizer (18t·hm-2)+chemical fertilizer (N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2)+SAP, namely organic fertilizer+chemical fertilizer+0%SAP(CK), organic fertilizer+chemical fertilizer+0.25%SAP(1.5t·hm-2), organic fertilizer+chemical fertilizer+0.5%SAP(3t·hm-2),and organic fertilizer+chemical fertilizer+1%SAP (6t·hm-2). According to the comprehensive analysis of the first harvest, 1%SAP (6t·hm-2) showed the most significant improvement in soil water and fertilizer retention capacity, alleviation of soil salt damage, and increase in soil microbial diversity index and abundance compared to other treatments (p<0.05).

We found that organic fertilizer (18t·hm

-2)+chemical fertilizer (N:180kg·hm

-2, P:120kg·hm

-2, K:105kg·hm

-2)+1% SAP (6t·hm

-2) had the best effect, and subsequent field trials of different organic-inorganic composite conditioners will be conducted at this dosage. The later experiment adopts a split zone design, with irrigation treatment (flood irrigation) as the main zone and the addition of organic-inorganic composite soil conditioners as the secondary zone. The specific application amount is shown in

Table 2. After thoroughly mixing organic fertilizer, chemical fertilizer, and amendments, a one-time application was carried out on August 10, 2021. A rotary tiller was used to plow the land to a depth of 5-10cm. After the field was leveled, rapeseed seeds were sown on August 15, resulting in 18 plots through 6 treatments and three repetitions. Rapeseed is sown in sandy plots with a width of 6m and a length of 10m. Each plot is planted with a plant spacing of 20cm and a row spacing of 50cm, and a protective embankment with a width of 0.45m is set up. Relevant indicators are measured on the 15th, 30th, 45th, and 60th days after emergence.

On the day after sowing, all communities were irrigated with the same amount of water (45mm) to promote seed germination and emergence. According to local production practices, irrigation is not carried out from the emergence of rapeseed to the rapid growth period (0-45 days). Irrigation treatment will be implemented starting from the rapid growth period of leaves (after 45 days) (irrigation will be carried out during the seedling stage, budding stage, flowering stage, and silique ripening stage throughout the entire growth period, with a total irrigation amount of 4000 m3/hm2), until three weeks before harvest. We followed local sand planting practices for other field management measures.

2.3. Determination of Plant Nutrient Content

On the 15th, 30th, 45th, and 60th day after emergence, three rapeseed plants with fully unfolded leaves were selected for each plot. The total nitrogen content of plants (roots, stems, leaves) was evaluated using the Kjeldahl nitrogen determination method, the total phosphorus content was determined using the vanadium molybdenum yellow colorimetric method, and the K

+and Na

+content of plants was analyzed using flame photometry. According to the method proposed by Hou et al. (2018)[

25], the total nitrogen content (TN) was evaluated and calculated using formula (1); The total phosphorus content was analyzed according to the method of Hou et al. (2018)[

25], using a spectrophotometer UV-1900i (Shimadzu (China) Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) to measure the absorbance of the solution at a wavelength of 440nm. Then, the total phosphorus content was calculated based on the absorbance value and the standard curve, and the total phosphorus content (TP) was calculated using formula (2); The content of K

+and Na

+in plants was determined using the method described by Liu et al. (2015)[

26], and the K

+and Na

+content was calculated using formula (3).

In the formula, V is the volume of standard acid consumed for titration of the sample (mL); V

0 is the standard acid volume consumed for titration blank (mL);c: Standard acid concentration (

mol/L); α is the division multiple (total constant volume of boiling solution/volume absorbed during measurement); 14.01 is the molar mass of nitrogen (

g/mol); M is the dry weight mass of the sample (g).

In the formula, ρ represents the phosphorus concentration (μg/mL) of the test colorimetric solution obtained from the standard curve; V represents the constant volume of color reaction (mL), and ts is the division multiple (total constant volume of digestion solution/volume of digestion solution absorbed during color development); M is the mass of the plant sample (g); 10

-4 is the coefficient that converts μg to g and adjusts it to a percentage (10

-6 × 100=10

-4).

Among them, V represents the total volume of the sample solution (mL), such as the constant volume of the extraction solution; M represents the dry weight mass of the plant sample (g), which needs to be dried at 105℃and weighed; 10-4: Unit conversion coefficient (because1μ g/g=10-4%).

2.4. Determination of Chlorophyll Content

To investigate the long-term physiological response of oilseed rape to organic-inorganic composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ, 5 samples were randomly selected from each plot. Chlorophyll pigments were extracted from frozen mature leaf samples at absorption wavelengths of 665, 649, and 453nm, and analyzed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer UV-1900i (Shimadzu (China) Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) according to the method of Mahdavinia et al. (2004)[

27].

2.5. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

The SOD activity was evaluated according to the method of Geng et al. (2016)[

29], based on the ability of SOD to inhibit NBT photochemical reduction at 560 nm. The POD activity was analyzed according to the method of Geng et al. (2016)[

29], based on the ability of POD to oxidize orthomethoxyphenol to 4-orthomethoxyphenol with hydrogen peroxide at 470 nm.

2.6. Determination of Dry Matter Accumulation

Randomly select 5 plants from each community, and blanch their roots, stems, and leaves in a drying oven DHG-9030A (Jing Hong Laboratory Instrument Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) at 105 ℃ for 30 minutes. Then, reduce the temperature to 85 ℃ and dry until constant weight is achieved. According to the method of Li et al. (2013)[

30], dry matter accumulation (DMA) was evaluated.

2.7. Yield, Quality, and Net Revenue (NR)

During the harvest period of two crops, select 3m2 of rapeseed from each plot, separate the grain parts separately, weigh them, and calculate the total yield using formula (4). Measure the content of crude protein (CP), crude ether extract (CEE), and crude fiber (CF) in the stems and leaves of the previously retrieved plants. CP is directly calculated based on formula (5). CEE was determined using Soxhlet extraction method, while CF was analyzed using filter bag differential method according to the methods of Barberán et al. (2015)[

33].

Net income (USD ha

-1) is calculated using formulas (6, 7) based on total revenue (TR), agronomic costs (AC), and other costs (OC).

In the formula, NR represents net income; TR stands for Total Revenue (TR, USD ha-1), which can be calculated by multiplying the yield of two crops (TY, t ha-1) by the current year’s selling price (Tprice, USD t-1). AC stands for agricultural cost (USD ha-1). OC represents other costs.

2.8. Model Description and Application

Entropy Weight Method (EWM) is an objective assignment method used to reduce bias caused by subjective assignment and determine the weights of indicators. TOPSIS is a multi-objective decision-making method that can identify the best solution from comparative studies of multiple options and objectives Wu et al. (2016)[

34]. In this study, EWM combined with TOPSIS (EWM-TOPSIS) was used to evaluate the optimal application treatment, which balanced the comprehensive benefits among TY, Quality, TCC, and NR under six treatments.

Firstly, based on the method described by Prober et al. (2015)[

35], a raw data matrix (X) was established for 6 treatments (x

i, i=1,2,3,..., n) and 4 evaluation metrics (x

j, j=1,2,3,..., m). Then, EWM was used to determine the weights of these indicators based on formula (8-12) . It is worth noting that our four evaluation indicators are all positive indicators (the larger the value, the better), and there is no need to perform inverse processing before calculating the weights.

In the formula, xij represents the value of the j-th evaluation index processed in the i-th step; Bij is the ratio of the i-th evaluation objective under the j index; Ej is the entropy value of the j index; Wj is the weight of indicator j.

Secondly, according to formula (13-16), normalize the normalized data and obtain the normalization matrix. The weighted matrix was obtained by multiplying the normalization matrix with the weights of each evaluation indicator. Determine the positive and negative ideal solutions (the Z

+and Z

-) using a weighted matrix.

Finally, based on formulas (17, 18), the Euclidean distance (the D

+and D

-) and the relative closeness (Ci) of each indicator to the positive and negative ideal solutions were determined using positive and negative ideal solutions. The higher the Ci value, the better the effect. Therefore, each treatment is sorted according to the size of the Ci value .

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Before analyzing the data, Shapiro Wilk and Levene tests were performed on the collected data using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). When the test results met p>0.05, it was considered that the data met the requirements of variance homogeneity and full distribution, and subsequent analysis of variance could be conducted. In this study, SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used to perform a two factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with fixed factors of days after emergence and treatment with conditioning agents, and harvesting as a random factor. Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare the significant differences between treatments (p<0.05). In addition, the statistical data was visualized by Origin 2024 (Originlab, USA).

3. Results

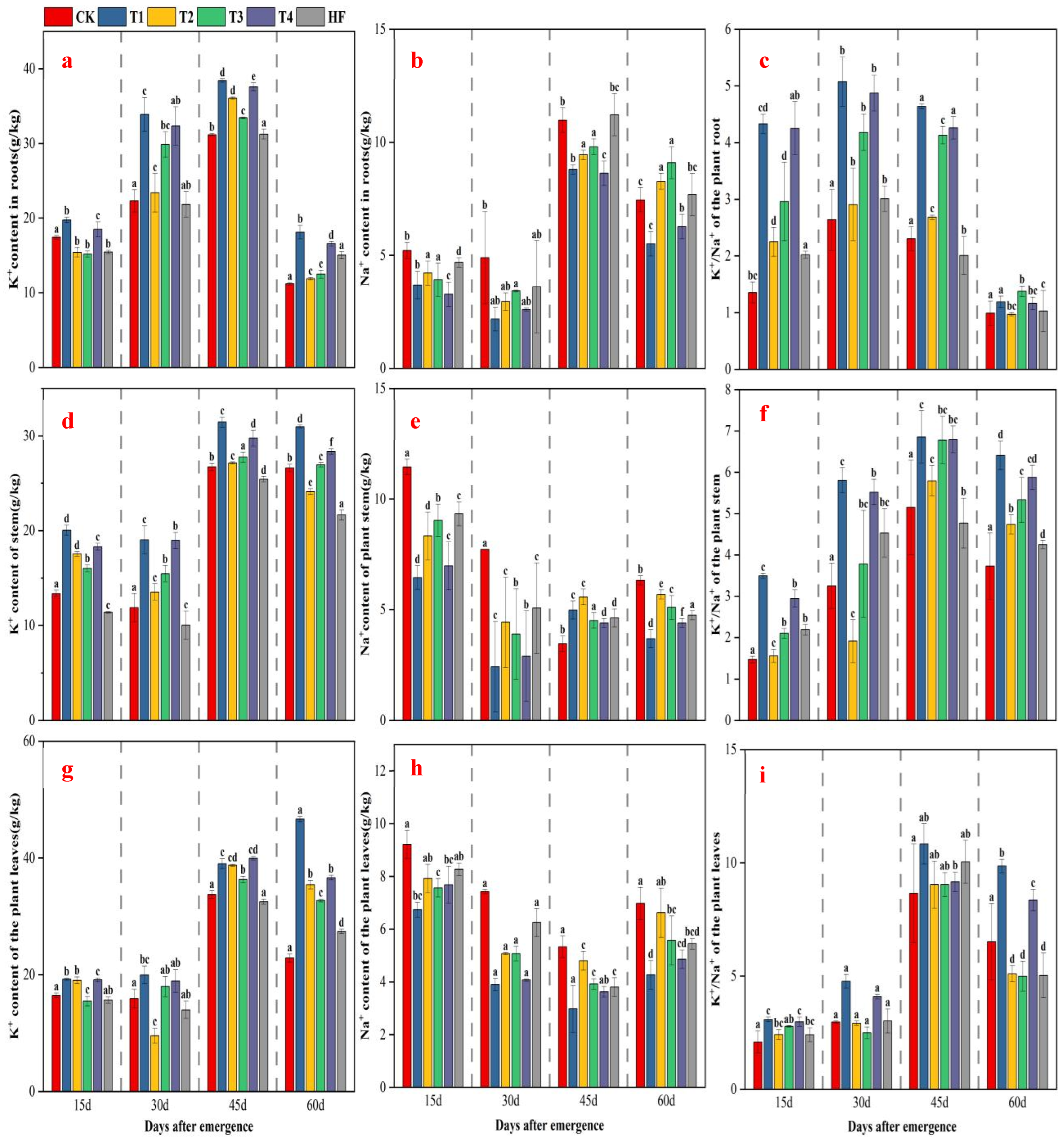

3.1. Root K+, Na+ Content and K+/Na + Ratio

The application of organic-inorganic composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ soil improvement and conditioning agents all increased the root K

+content and K

+/Na

+, while reducing the Na

+content. The K

+content increased most significantly at 60 days in T1 (SAP) and T4 (PⅠ+PⅡ), with increases of 57.14% and 63.09%, respectively (

p<0.05) (

Figure 2a). The Na+content showed a decreasing trend in T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments. Among them, T1 (SAP) showed the most significant effect (

p<0.05), with a maximum reduction of 60.16% at 30 days, while the Na

+content decreased relatively steadily in other treatments (

Figure 2b). Although K

+/Na

+showed an overall increase (

Figure 2c), T1 (SAP) showed the most significant difference in increase compared to other treatments (

p<0.05), indicating that SAP had a more advantageous effect within 60 days compared to other treatments.

3.2. Stem K+, Na+ Content and K+/Na+ Ratio

The K

+content in the stem significantly increased by 114.12% at 30 days in T1 (SAP) (

Figure 2d), with the most significant effect (

p<0.05). Therefore, K

+/Na

+increased significantly by 468.15% at 30 days in T1 (

p<0.05). Although T2 (PⅠ), T3 (PⅡ), and T4 (PⅠ+PⅡ) showed an increase (

Figure 2f), their overall effect was weaker than SAP treatment. Meanwhile, each treatment reduced the Na

+content in the stem within 60 days (

Figure 2e), indicating that the organic-inorganic composite conditioning agent has a significant effect on reducing soil Na

+content.

3.3. Leaf K+, Na+ Content and K+/Na+ Ratio

The K

+content in leaves increased by 6.99%, 49.56%, 45.29%, and 49.21%, respectively, within 60 days of SAP application (

Figure 2g). Therefore, K

+/Na

+increased by 48.45%, 138.69%, 12.75%, and 145.49%, respectively, within 60 days of T1 application (

Figure 2i). At the same time, although there was a significant increase in K

+content and K

+/Na

+after PⅠ, PⅡ, and their combined application, the SAP effect was significantly better than its single and combined application effects (

p<0.05). In addition, the Na+content in the leaves (

Figure 2h) showed a significant decrease within 60 days (

p<0.05).

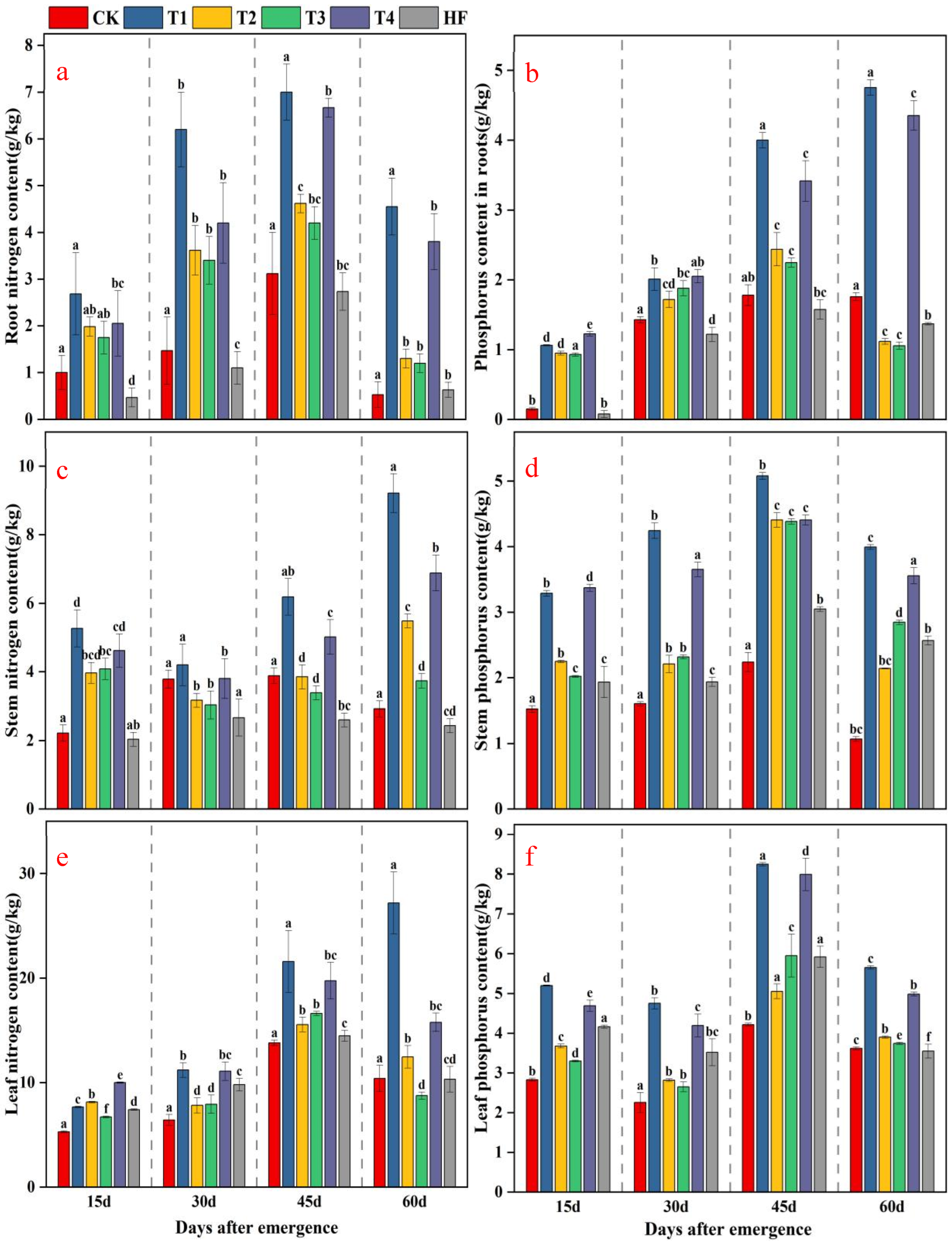

3.4. Root Nutrient Content

The overall nitrogen and phosphorus content in the roots showed an increasing trend. At 60 days, nitrogen content increased by 268.18% and 254.55% in T1 and T4 treatments (

Figure 3a), while phosphorus content increased by 30.30% and 30.09% in T1 and T4 treatments (

Figure 3b). However, the nitrogen and phosphorus content of T2 and T3 treatments showed a relative decrease within 60 days. After applying composite SAP, the nitrogen and phosphorus content in the roots significantly increased (

p<0.05), and was higher than the treatments of composite PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ. In addition, the combined application of PⅠ+PⅡ was also more effective than its single use. The composite SAP has a significant improvement effect on the soil structure of desertified land. Compared with PⅠ and PⅡ, SAP has the most significant effect on soil and plant nutrients (

p<0.05).

3.5. Stem Nutrient Content

The nitrogen and phosphorus content of the stem increased significantly at 60 days, with the highest increase of 80.85% and 68.09% in T1 and T4 (

Figure 3c). At the same time, the phosphorus content increased significantly by 18.83% and 15.23% in T1 and T4 at 45 days, respectively (

Figure 3d), while the increase in nitrogen and phosphorus content was relatively stable in other treatments. After applying composite SAP, the nitrogen and phosphorus content in plant stems was significantly higher than that of composite PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ stems (

p<0.05), and composite SAP enhanced the mobility of phosphorus in the soil, significantly increasing the accumulation of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients in stems.

3.6. Nutrient Content of Leaves

The nitrogen and phosphorus content in the leaves showed an increasing trend within 60 days. Especially at 45 and 60 days, the increase was most significant. The nitrogen content of T1 and T4 treatments increased by 28.30% and 25.37% at 45 days, and by 103.23% and 87.90% at 60 days (

Figure 3e). At the same time, the phosphorus content of T1 and T4 increased by 30.68% and 29.39%, respectively, after 45 days; Increase by 19.65% and 19.30% at 60 days (

Figure 3f). After applying organic-inorganic composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ conditioners, the nitrogen and phosphorus content of leaves significantly increased. The application effect of PⅠ+PⅡ was better than that of PⅠ and PⅡ alone, but its overall effect was weaker than that of composite SAP, with the composite SAP having the most significant effect (

p<0.05).

3.7. Chlorophyll Content

The overall trend of chlorophyll content is increasing.

Figure 4 shows that the application of organic-inorganic composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ all increased the chlorophyll content of leaves, with the composite SAP treatment being the most optimal, followed by PⅠ+PⅡ treatment. SAP improved the Chl-a, Chl-b, Carotenoid content (CC), and TCC of leaves, achieving significant differences (

p<0.05) between SAP and PⅠ+PⅡ in most growth stages. In addition, increasing the total chlorophyll content (TCC) in leaves has a promoting effect on improving net photosynthetic rate (Pn) and transpiration rate (Tr), thereby increasing nutrient accumulation.

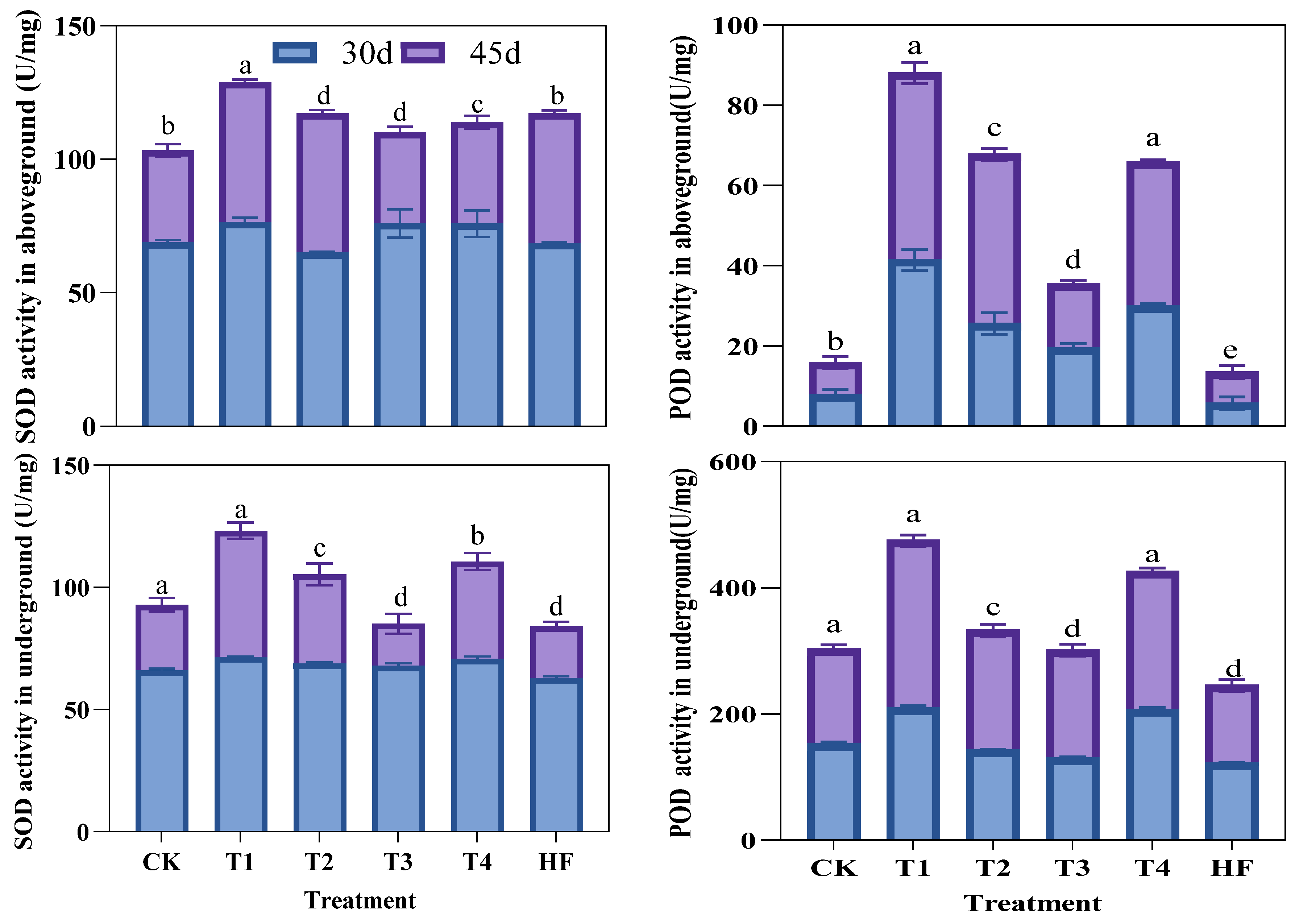

3.8. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

The results in

Figure 5 indicate that there were significant differences (

p<0.05) in SOD and POD levels between the aboveground and underground parts of crops at 30 and 45 days.The application of SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ all increased the activities of SOD and POD in the aboveground and underground parts of oilseed rape feed, with SAP showing the most significant effect (

p<0.05). The overall difference in SOD activity between aboveground and underground parts is relatively small, with an increase of 65.29% in SOD activity after 45 days of application of SAP in the underground part. However, there was a significant difference in POD activity between aboveground and underground parts (

p<0.05), with SAP application increasing POD activity by 161.56% and 161.58% at 30 and 45 days above ground, while SAP application increased POD activity in underground parts by 19.94% and 40.31%, respectively. Except for the overall good effect of PI+PII, the effects of PI and PII are average. In summary, the amendment can improve the nutrient availability and SOD and POD activities of desertified soil, which is beneficial for maintaining soil fertility and productivity, and has a positive effect on promoting crop yield.

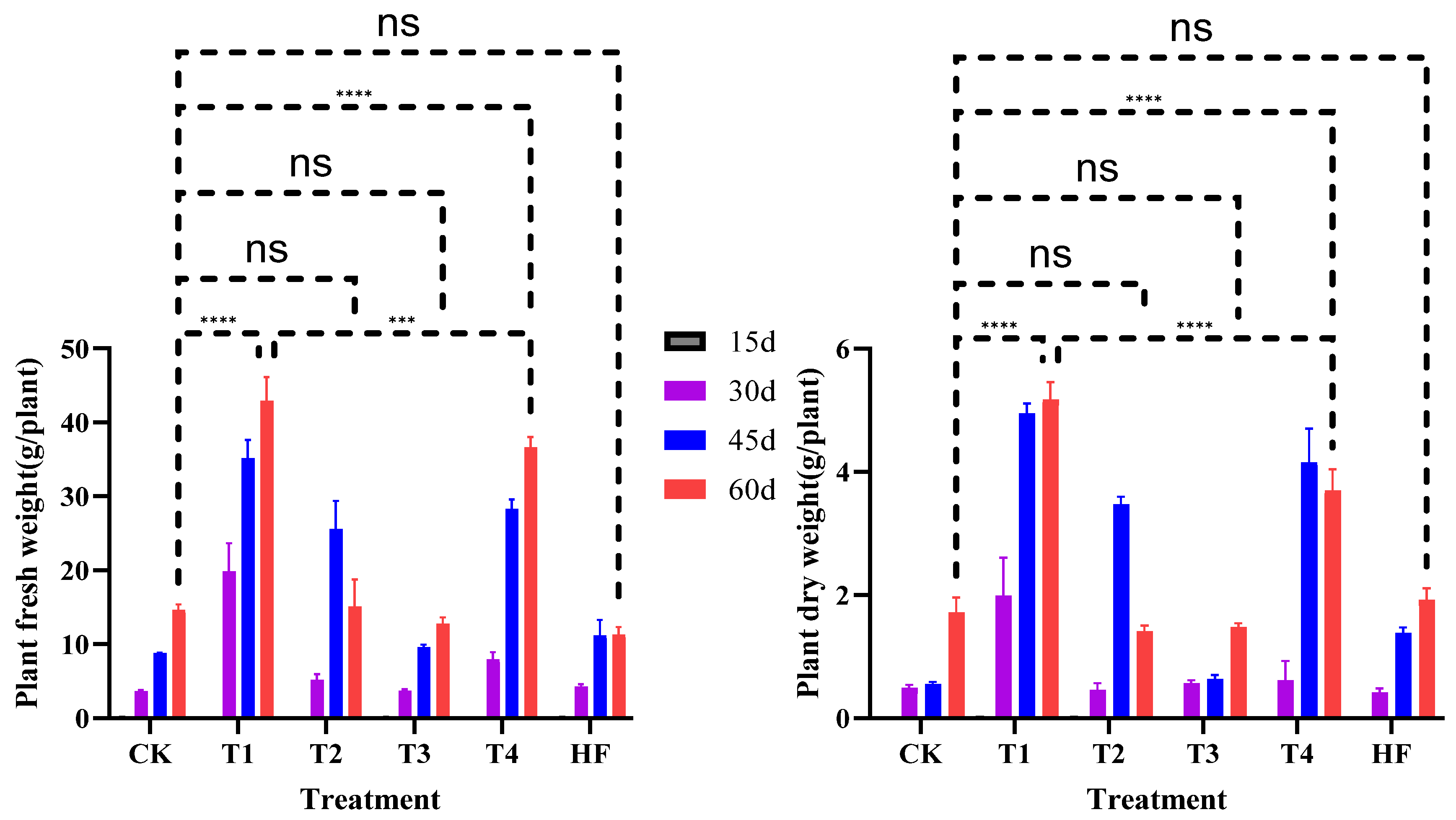

3.9. Changes in Dry and Fresh Substances

The application of composite SAP and PⅠ+PⅡ had a significant effect on the accumulation of dry and fresh matter (

p<0.0001). The results in

Figure 6 show that the fresh weight of T1 treatment increased by 366.27% at 30 days; T4 increased by 152.83% at 45 days. At the same time, its dry weight significantly increased by 376.8% at 30d, 45d, and 60d of T1; 258.21% and 196.56%; T4 significantly increased by 151.69% and 93.04% at 45 and 60 days (

p<0.0001). In addition, the use of composite SAP significantly improved the fresh and dry weight of plants compared to PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ. Composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ further increased the daily growth rate (DGR) of rapeseed feed by increasing soil nutrient content, thereby increasing the dry matter accumulation (DMA) during the harvest period, especially under composite SAP treatment, followed by PⅠ+PⅡ treatment.

3.10. Comprehensive Evaluation

According to

Table 3, the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR of rapeseed feed were comprehensively evaluated using the EWM model combined with the TOPSIS model (EWM-TOPSIS), and similar Ci and Rank were obtained in two growing seasons. Under different treatment conditions of the two crops, T1 (composite SAP) treatment had the highest Ci, which was recommended by the model, followed by T4 (composite PI+PII) treatment.

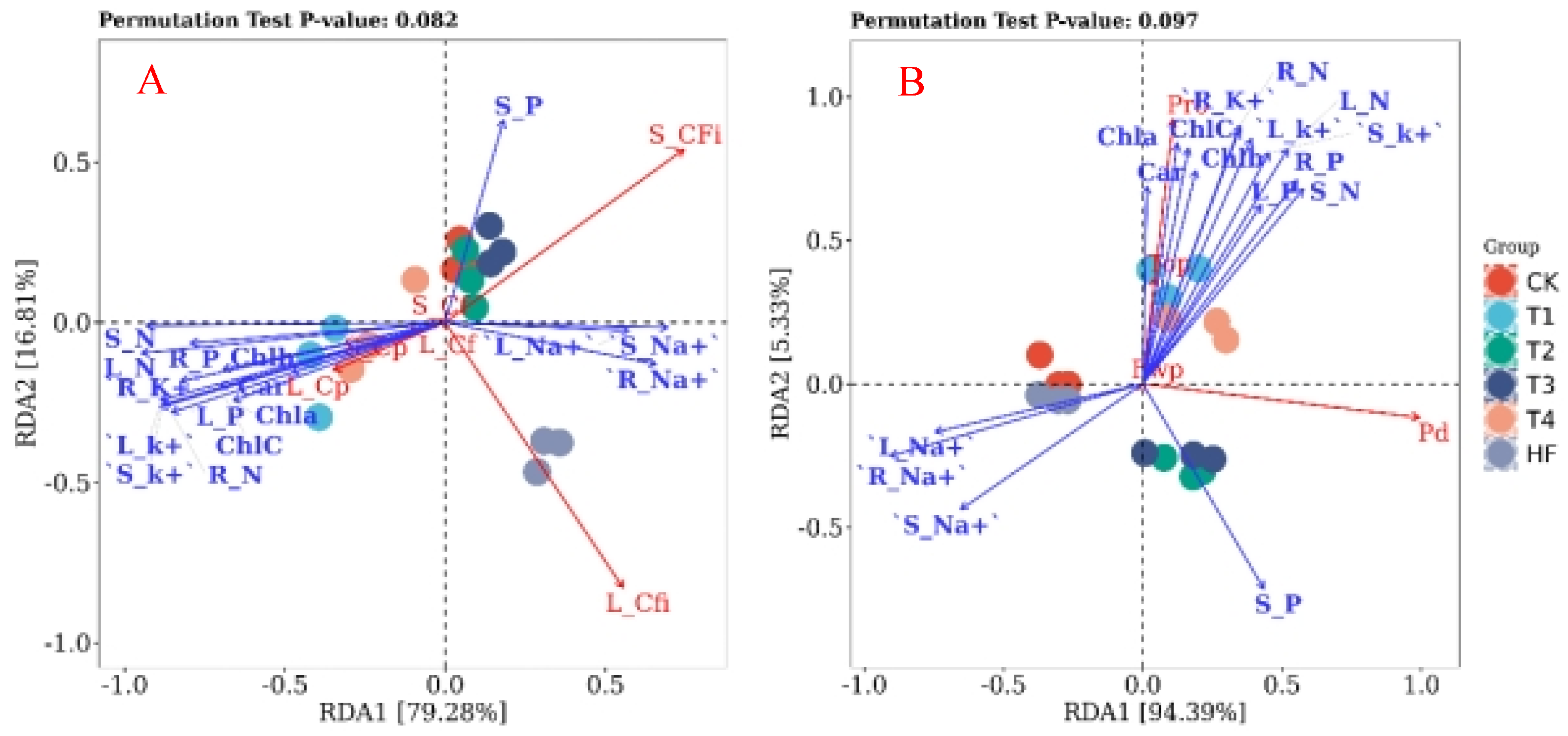

3.11. Redundancy Analysis of Production and Quality

To clarify the effects of each treatment on the nutrient content, chlorophyll, K

+, Na

+, yield components, and quality of feed rapeseed, redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted.

Figure 7A shows that leaf crude fiber is positively correlated with Na

+in roots, stems, and leaves, and negatively correlated with stem and leaf crude protein and fat; There is a positive correlation between stem fiber and stem phosphorus; The crude protein and fat in stems and leaves are positively correlated with root nitrogen and phosphorus, root K

+, stem nitrogen, stem K

+, leaf nitrogen and phosphorus, leaf K

+, Chl-a, Chl-b, TCC, and carotenoids. T1 and T4 are positively correlated with stem and leaf crude fat and stem and leaf crude protein, while HF treatment is positively correlated with leaf crude fiber. In summary, Na

+in roots, stems, and leaves restricts the formation of crude fat and crude protein. The use of organic-inorganic composite SAP and PⅠ+PⅡ treatment in desertified areas promotes the increase of nutrient, K

+, and chlorophyll content in feed rapeseed, thereby promoting the synthesis of crude protein and crude fat, which is beneficial for its quality improvement.

The results in

Figure 7B indicate that Na+in roots, stems, and leaves is positively correlated with CK and HF treatments; Stem phosphorus showed a positive correlation with T2 and T3 treatments; Yield and fresh weight per plant are positively correlated with root nitrogen, root phosphorus, root K

+, stem nitrogen, stem K

+, leaf nitrogen, leaf phosphorus, and leaf K

+; The T1 and T2 treatments are positively correlated with yield and fresh weight per plant. Therefore, applying organic-inorganic composite SAP and PⅠ+PⅡ treatment in desertified soil can increase the nutrient content of rapeseed feed, thereby promoting an increase in fresh weight per plant and correspondingly increasing its yield.

4. Discussion

4.1. Organic Inorganic Composite SAP Improves Soil Ecological Environment, Enhances Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Feed Rapeseed Leaves, and Improves Plant Growth

The organic-inorganic composite SAP improves soil nutrition by reducing soil salinization and increasing soil aggregate structure, thereby promoting the growth of oilseed rape as feed. Rapeseed feed subjected to desertification and drought stress not only clears accumulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) by upregulating leaf SOD and POD activities, but also increases osmotic potential through soil water and fertilizer retention to prevent excessive water loss in plants[

37,

38]. The application of composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ significantly improved soil physicochemical properties and increased SOD and POD activities in oilseed rape leaves and plant nutrient content under drought stress. Among them, the composite SAP had the most significant effect (

p<0.05), which may be related to the upregulation of drought resistant gene expression and enhanced cell stability by applying SAP and other amendments[

39,

40,

41], and the increase in related metabolic enzyme activity [

42,

43], thereby improving plant stress resistance and promoting growth under drought stress.

4.2. Application of Organic-Inorganic Composite SAP to Improve the Photosynthetic Capacity of Rapeseed Leaves in Feed, Increase Yield and Quality

The organic-inorganic composite SAP conditioner has a positive soil conditioning effect on the physiological characteristics of rapeseed feed. Compound SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ increased dry matter accumulation during harvest by increasing TCC in rapeseed leaves, with compound SAP being the most significant (

p<0.05). The increase in TCC in plant leaves may be related to the increase in leaf nutrients and photosynthetic enzyme activity after SAP application[

44,

45]. The increase in TCC enables plants to accumulate substances more efficiently and intensively[

46,

47], thereby increasing the yield of oilseed rape as feed. The improvement of TCC and LAI may be attributed to the deposition of nutrient elements around the leaf cell wall after the application of composite SAP, which protects the cell membrane and prevents a decrease in chlorophyll content[

48,

49]n the other hand, it may be due to an increase in enzyme activity related to chlorophyll synthesis, which in turn increases chlorophyll content[

50,

51]. Both improvements enable plant leaves to receive and capture more light energy for material production. As the growth period prolongs, compound SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ can significantly increase plant biomass, with compound SAP showing the most significant effect. Therefore, the application of composite SAP is more effective in increasing the yield of rapeseed feed compared to PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ. It should be noted that rapeseed feed is aimed at harvesting fresh grass feed, and its quality greatly affects the feeding effect of forage animals. Compound SAP can effectively improve the quality of forage by increasing crude protein while reducing crude fiber content[

52,

53]. The results showed that the application of composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ increased the crude protein content in the stem by 65.98% -70.10%, and decreased the crude fiber content by 22.21% -43.59%; The crude protein content in the leaves increased by 86.05% -86.85%, and the crude fiber decreased by 12.37% -18.86%, which is consistent with the actual growth of the plants[

54]. Among them, the compound SAP showed the best effect and significantly improved the quality of rapeseed feed.

4.3. Organic Inorganic Composite SAP Promotes Nutrient Absorption in Rapeseed Feed and Its Environmental Advantages

The mechanism by which roots acquire nutrient ions and subsequently transport and maintain the concentration in cell fluid determines the survival of plants in sandy areas [

55]. The organic-inorganic composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ conditioners improved the TN, TP, and TK of rapeseed feed, with the composite SAP showing the best effect. This may be related to the fact that composite SAP, PI, PII, and PI+PII enhance soil adsorption and gas exchange capacity, accelerate aboveground water consumption, and promote root extension to deeper soil layers[

56]. We found that SAP significantly increased the TY and NR of rapeseed feed by 148.32% and 197.62%, respectively. Applying composite SAP, PⅠ, PⅡ, and PⅠ+PⅡ avoids excessive economic losses by increasing crop TY. In addition, the main reason why composite SAP treatment did not improve NR more than PⅠ+PⅡ is that the effect of related polymer materials is limited. Therefore, in future research, materials with better effects than polyacrylamide, humic acid, and attapulgite should be sought to carry out research on their combined application with organic fertilizers and chemical fertilizers. More noteworthy is that SAP has the characteristics of being non-toxic to plants and the environment, highly absorbable, and rapidly transported in various organs of plants. It can also serve as a carrier to accurately deliver some growth regulators, osmotic regulators, and nutrients to plants[

57,

58], promote crop growth, and improve stress resistance to abiotic factors [

59]. Therefore, our research and development based on SAP as a new soil improvement regulator provides a feasible strategy for alleviating crop environmental stress.

4.4. Potential Advantages of Combining Organic-Inorganic Composite SAP with Practical Applications and Its Differences from Single Soil Conditioners

Most of the arid areas in Xinjiang, China use water-saving irrigation projects and other measures to alleviate drought stress [

3]. SAP, as a multifunctional soil improvement and conditioning agent, has shown significant potential for water conservation, yield increase, and soil improvement in practical applications [

60]. If the two are combined in actual planting, it can further improve the quality and upgrade of agriculture in arid areas of Xinjiang. In addition, this study shows that the use of organic-inorganic composite SAP has significant advantages over a single soil improvement agent, and the difference between it and a single soil improvement agent is obvious. This may be due to the fact that polymer composite materials can combine materials with different properties through physical or chemical methods, which can leverage the advantages of each component and compensate for the shortcomings of a single material[

61,

62]. At the same time, the combination of organic-inorganic compounds effectively achieved increased yield and improved quality of rapeseed feed. In the future, it is necessary to combine precision agriculture technology to further explore the value of organic-inorganic composite soil conditioners in sustainable agriculture.

5. Conclusions

Different organic-inorganic composite soil conditioners are used in desertified land to improve the soil structure, thereby enhancing the efficiency of plant water and fertilizer utilization and increasing its benefits on the yield and quality of rapeseed feed. Especially, the stress resistance effect is more significant after applying the composite conditioner of organic fertilizer+chemical fertilizer+1% SAP (6t·hm-2). The addition of organic-inorganic composite soil conditioners significantly reduced the harm of salinization and improved the physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant metabolism mechanisms in feed rapeseed compared to the use of organic-inorganic and HF treatments alone. The results indicate that, based on the local practice of planting sandy soil, the optimal ratio for combining organic fertilizer, chemical fertilizer,and SAP is organic fertilizer18t·hm-2+Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2,P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2)+SAP6t·hm-2. It can be recommended to improve the soil fertility and growth characteristics of rapeseed feed. In addition, a comprehensive evaluation of all treatments in the region (sandy soil) found that the application of composite SAP is a potential practice that can improve the growth, yield, and quality of oilseed rape in desertified and arid areas, and is environmentally friendly, achieving economic and environmental advantages.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript. H.W. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript;K.W. was responsible for conducting the experiments, writing, and also reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the special fund for Key Science & Technology Program in Xinjiang Province of China (No. 2022B02053-1), the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps guiding science and technology programme projects(2023ZD063) and the Science and Technology Program Project of the Eighth Division Shihezi City(2024BX03)and the Seventh Division Huyanghe City Science and Technology Plan Project (2025D07).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Pishan Farm in Xinjiang for providing climate data and to the staff of the farm for assisting in conducting field experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lili Deng Tao Jiang Binghui He, et al. Effects of polyacrylamide combined with several enhancers on soil nitrogen adsorption-desorption and migration release. Soil and Water Conservation Journal. 2009, 23, 120–124.

- Qianqian Wang. A Brief Analysis of Desertification in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Environmental Research and Monitoring. 2017, 1, 32–38.

- Yonghui Yang Jinli Ding Jisheng Wu, et al. Effects of super absorbent polymers on soil structure under different water conditions. Soil Bulletin. 2012, 43, 1065–1072.

- Ma Xin Wei Zhanmin Yu Jian, et al. Study on the long-term effect of water-retaining agent on soil properties. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage. 2013, 32, 117–120.

- Ji Xiaomin, Zhou Bin, Chi Wenze, et al. Effects of NSI-415 water retaining agent on physicochemical properties of chestnut soil and growth of Ulmus pumila. Xinjiang Agricultural Sciences 2008, S1, 172–174.

- De Tender, C.; et al. Dynamics in the strawberry rhizosphere microbiome in response to biochar and Botrytis cinereal leaf infection. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tender, C.; et al. Biological, physicochemical and plant health responses in lettuce and strawberry in soil or peat amended with biochar. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. Biochars effect on crop productivity and the dependence on experimental conditions—a meta-analysis of literature data. Plant Soil. 2013, 373, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, E.; Bouras, G.; Kalderis, D.; Diamadopoulos, E. Biochar production by sewage sludge pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2013, 101, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zwieten, L.; et al. Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility. Plant Soil. 2010, 327, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimmer, J.T.; Cusick, R.D.; Guest, J.S. Amplifying progress toward multiple development goals through resource recovery from sanitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10765–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koottatep, T.; Taweesan, A.; Kanabkaew, T.; Polprasert, C. Inconvenient truth: unsafely managed fecal sludge after achieving MDG for decades in Thailand. Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Development. 2021, 11, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Bijay-Singh; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: an increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Applied Sciences. 2021, 3, 518. [CrossRef]

- Rayne, N.; Aula, L. Livestock Manure and the Impacts on Soil Health: A Review. Soil Systems. 2020, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, K.; Ryals, R. Nutrient cycling in agroecosystems: Balancing food and environmental objectives. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 2017, 41, 761–798. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, E. Global meta-analysis of the relationship between soil organic matter and crop yields. SOIL. 2019, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poornima, R.; Suganya, K.; Sebastian, S.P. Biosolids towards Back–To–Earth alternative concept (BEA) for environmental sustainability: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2022, 29, 3246–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Sarkar, A.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Agricultural utilization of biosolids: A review on potential effects on soil and plant grown. Waste Management. 2017, 64, 1171–32. [Google Scholar]

- Linda, S. Integrating recent scientific advances to enhance non-sewered sanitation in urban areas. Nature Water. 2024, 2, 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Gwara, S.; Wale, E.; Odindo, A.; Buckley, C. Attitudes and Perceptions on the Agricultural Use of Human Excreta and Human Excreta Derived Materials: A Scoping Review. Agriculture. 2021, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.; Holm, R.; Parker, A. A Review of the Financial Value of Faecal Sludge Reuse in Low-Income Countries. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, D.W. A critical review of the conventional SOC to SOM conversion factor. Geoderma. 2010, 156, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, M.; Glaser, B.; Turrión, M.B. Storage of organic carbon and Black carbon in density fractions of calcareous soils under different land uses. Geoderma. 2010, 159, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveroen, M.E.; MacKinnon, M.D.; Fedorak, P.M. Polyacrylamide added as a nitrogen source stimulates methanogenesis in consortia from various wastewaters. Water Res. 2005, 39, 3333–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou Xianqing Li, et al. Superabsorbent polymers influence soil physical properties and increase potato tuber yield in a dry-farming region. Journal of Soil & Sediments. 2018, 18, 816–826.

- Liu, X.; Chan, Z. Application of potassium polyacrylate increases soil water status and improves growth of bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) under drought stress condition. Scientia horticulturae. 2015, 197, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinia, G.R.; Pourjavadi, A.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; et al. Modified chitosan Superabsorbent hydrogels from poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) grafted chitosan with salt-and pH-responsiveness properties. EUROPEAN POLYMER JOURNAL. 2004, 40, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauth, D.M.; Bouldin, J.L.; Green, V.S.; et al. Evaluation of a polyacrylamide soil additive to reduce agricultural-associated contamination. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2008, 81, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Ma, Q.; Chen, J.; et al. Effects of polymer coated urea and sulfur fertilization on yield, nitrogen use efficiency and leaf senescence of cotton. Field crops research. 2016, 187, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Wang, Z.H.; Stewart, B.A. Responses of Crop Plants to Ammonium and Nitrate N - ScienceDirect. Advances in Agronomy. 2013, 118, 205–397. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Investing in sustainable crop intensification: The case for improving soil health; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2008.

- 32JA; Van Veen, et al. Turnover of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus through the microbial biomass in soils incubated with 14-C-, 15N-and 32P-labelled bacterial cells. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1987, 19, 559–565. [CrossRef]

- Barberán, A.; Mcguire, K.L.; Wolf, J.A.; et al. Relating belowground microbial composition to the taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional trait distributions of trees in a tropical forest. Ecology Letters. 2015, 18, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zeng, G.; Liang, J.; et al. Responses of bacterial community and functional marker genes of nitrogen cycling to biochar, compost and combined amendments in soil. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2016, 100, 8583–8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prober, S.M.; Leff, J.W.; Bates, S.T.; et al. Plant diversity predicts beta but not alpha diversity of soil microbes across grasslands worldwide. Ecology Letters. 2015, 18, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liao, S.; et al. Effects of two slow-release nitrogen fertilizers and irrigation on yield, quality, and water-fertilizer productivity of greenhouse tomato. Agricultural water management. 2017, 186, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Motamedi, E.; Motesharezedeh, B.; et al. Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) composites reinforced with natural char nanoparticles toward environmentally benign slow-release urea fertilizers. Journal of environmental chemical engineering. 2020, 8, 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimi, T.E.; Chaib, M.; Raihane, M.; et al. Poly(ε-caprolactone)-g-Guar Gum and Poly(ε-caprolactone)-g-Halloysite Nanotubes as Coatings for Slow-Release DAP Fertilizer. Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; et al. Revegetated shrub species recruit different soil fungal assemblages in a desert ecosystem. Plant and soil. 2018, 435, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zuo, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. Responses of soil fungal community to the sandy grassland restoration in Horqin Sandy Land, northern China. Environmental monitoring and assessment. 2015, 188, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachshon, U. Soil degradation processes: it’s time to take our head out of the sand. Geosciences 2021, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.; Jean, L.P. SOIL - Building a Sustainable Citywide Sanitation Service; SOIL, 2019.

- Silva, R.; Canellas, L. Organic matter in the pest and plant disease control: a meta-analysis. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture. 2022, 9, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Carrard, N.; Jayathilake, N.; Willetts, J. Life-cycle costs of a resource-oriented sanitation system and implications for advancing a circular economy approach to sanitation. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 307, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudey, L. The cost of urban sanitation solutions: a literature review. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 2018, 8, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryals, R.; Hartman, M. D.; Parton, W. J.; DeLonge, M. S.; Silver, W. L. Long-term climate change mitigation potential with organic matter management on grasslands. Ecological Applications. 2015, 25, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawken, P. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming; Penguin Books Ltd.: London, 2017.

- Powlson, D.S.; Whitmore, A.P.; Goulding, K.W.T. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change: a critical re-examination to identify the true and the false. European Journal of Soil Science. 2011, 62, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Esray, S.A. Towards a recycling society: ecological sanitation -closing the loop to food security. Water Sci. Technol. 2001, 43, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, N.; Ronteltap, M.; Boincean, B.; Lens, P.N.L. Treatment of Source-Separated Human Feces via Lactic Acid Fermentation Combined with Thermophilic Composting. Compost Science & Utilization. 2017, 25, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bizuhoraho, T.; Kayiranga, A.; Manirakiza, N.; Mourad, K.A. The effect of land use systems on soil properties; A case study from Rwanda. Sustainable Agriculture Research. 2018, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.Y.L.; Van Zwieten, I.; Meszaros, A. Downie, and S. Joseph. Agronomic values of greenwaste biochar as a soil amendment. Soil Research. 2007, 45, 629–634. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Jacobsen, J. Plant nutrition and soil fertility. Nutrient Management Module. 2005, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, S.; et al. Impact of biochar and hydrochar addition on water retention and water repellency of sandy soil. Geoderma. 2013, 202, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Effects of biochar amendment on rapeseed and sweet potato yields and water stable aggregate in upland red soil. Catena. 2014, 123, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaz, K.; et al. Drought impact on Pb/Cd toxicity remediated by biochar in Brassica campestris. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Sciences. 2014, 14, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M.; Heidarzadeh, A. Fertilizer systems deployment and zeolite application on nutrients status and nitrogen use efficiency. J of Plant Nutrition. 2021, 44, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghbani-Arani, A.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M.; Mashhadi Akbar Boojar, M.; Mokhtassi Bidgoli, A. Towards improving the agronomic performance, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and pigments in fenugreek using zeolite and vermicompost under deficit water stress. Ind Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, K.K.; Misra, A.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Hati, K.M. Effect of integrated use of farmyard manure and chemical fertilizers on soil physical properties and productivity of soybean. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 110, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, C. Effects of long-term (23 years) mineral fertilizer and compost application on physical properties of fluvo-aquic soil in the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 156, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Chen, H.; Gong, Y.; Fan, M.; Yang, H.; Lai, R. Effects of 15 years of manure and inorganic fertilizers on soil organic carbon fractions in a wheat-maize system in the North China Plain. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 2012, 92, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhima, K.V.; Lithourgidis, A.S.; Vasilakoglou, I.B.; Dordas, C.A. Competition indices of common vetch and cereal intercrops in two seeding ratio. Field Crops Res. 2007, 100, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankou, C.; Lithourgidis, A.; Menexes, G.; Dordas, C. Importance of selection of cultivars in wheat-pea intercropping systems for high productivity. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The basic situation of the experimental area in Pishan County.

Figure 1.

The basic situation of the experimental area in Pishan County.

Figure 2.

Based on the treatment of different organic-inorganic composite modifiers, the overall trend of K+, Na+content, and K+/Na+ changes in the roots, stems, and leaves of oilseed rape at different emergence days is similar. Therefore, the combined results show that.

Figure 2.

Based on the treatment of different organic-inorganic composite modifiers, the overall trend of K+, Na+content, and K+/Na+ changes in the roots, stems, and leaves of oilseed rape at different emergence days is similar. Therefore, the combined results show that.

Figure 3.

The variation trend of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrient content in the roots, stems, and leaves of rapeseed feed at different emergence days.

Figure 3.

The variation trend of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrient content in the roots, stems, and leaves of rapeseed feed at different emergence days.

Figure 4.

Trend of chlorophyll content in rapeseed feed at different seedling emergence days.

Figure 4.

Trend of chlorophyll content in rapeseed feed at different seedling emergence days.

Figure 5.

SOD and POD enzyme activities in the aboveground and underground parts of rapeseed under different treatments.

Figure 5.

SOD and POD enzyme activities in the aboveground and underground parts of rapeseed under different treatments.

Figure 6.

The changes of fresh weight and dry matter accumulation of forage rape under the treatment of SAP, PI, PII and PI+PII were applied. Note:“∗∗∗∗”indicates extremely significant,that is p<0.0001.

Figure 6.

The changes of fresh weight and dry matter accumulation of forage rape under the treatment of SAP, PI, PII and PI+PII were applied. Note:“∗∗∗∗”indicates extremely significant,that is p<0.0001.

Figure 7.

(A) RDA analysis of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment, K+, Na+ and quality in different organs of rape.(B) RDA analysis of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment, K+, Na+ and output components in different organs of rape.

Figure 7.

(A) RDA analysis of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment, K+, Na+ and quality in different organs of rape.(B) RDA analysis of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment, K+, Na+ and output components in different organs of rape.

Table 1.

Soil properties of the experimental sites (0-20cm soil layer).

Table 1.

Soil properties of the experimental sites (0-20cm soil layer).

| Harvesting |

pH |

EC value

(ms/cm) |

K+content

(mg kg−1) |

Na+content

(mg kg−1) |

Organic Carbon

(OC)

(g kg−1) |

Alkali

hydrolyzable nitrogen content

(mg kg−1) |

Available phosphorus content

(g kg−1) |

| First cut |

9.31 |

1.54 |

22.13 |

45.21 |

3.17 |

3.13 |

10.26 |

| Second cut |

9.56 |

1.55 |

21.86 |

46.18 |

3.08 |

3.18 |

9.86 |

Table 2.

Application rates of organic-inorganic composite improved conditioning agents under different treatments.

Table 2.

Application rates of organic-inorganic composite improved conditioning agents under different treatments.

| Treatment |

Fertilization plan |

| CK |

Organic fertilizer18t·hm-2 +Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2) |

| T1 |

Organic fertilizer18t·hm-2+Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2) + SAP(6 t·hm-2) |

| T2 |

Organic fertilizer18t·hm-2+Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2) +PⅠ(6 t·hm-2) |

| T3 |

Organic fertilizer18t·hm-2+Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2,K:105kg·hm-2) +PⅡ(6 t·hm-2) |

| T4 |

Organic fertilizer18t·hm-2+Fertilizer(N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2, K:105kg·hm-2) +PⅠ+PⅡ(6t·hm-2) |

| HF |

N:180kg·hm-2, P:120kg·hm-2,K:105kg·hm-2

|

Table 3.

To objectively evaluate the improvement effect of different treatments based on the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR of oilseed rape harvested in two seasons, the entropy weight TOPSIS method was used to comprehensively evaluate the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR of oilseed rape harvested in two seasons.

Table 3.

To objectively evaluate the improvement effect of different treatments based on the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR of oilseed rape harvested in two seasons, the entropy weight TOPSIS method was used to comprehensively evaluate the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR of oilseed rape harvested in two seasons.

| Harvest |

Irrigation |

Spraying |

Weighted matrix |

Euclidean distances |

Relative closeness |

Rank |

| TY |

Quality |

TCC |

NR |

Di+

|

Di-

|

Ci

|

|

| First crop |

flood irrigation |

CK |

0.033 |

0.001 |

0.006 |

0.051 |

0.26 |

0.29 |

0.30 |

5 |

| T1 |

0.04 |

0.136 |

0.128 |

0.02 |

0.15 |

0.36 |

0.81 |

1 |

| T2 |

0.01 |

0.131 |

0.083 |

0.002 |

0.20 |

0.35 |

0.51 |

3 |

| T3 |

0.041 |

0.006 |

0.007 |

0.069 |

0.06 |

0.38 |

0.46 |

4 |

| T4 |

0.01 |

0.118 |

0.096 |

0.007 |

0.41 |

0.06 |

0.66 |

2 |

| HF |

0.03 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.31 |

0.22 |

0.28 |

6 |

| Second crop |

flood irrigation |

CK |

0.026 |

0.001 |

0.004 |

0.056 |

0.21 |

0.36 |

0.41 |

5 |

| T1 |

0.03 |

0.136 |

0.128 |

0.08 |

0.12 |

0.41 |

0.82 |

1 |

| T2 |

0.043 |

0.005 |

0.009 |

0.078 |

0.20 |

0.35 |

0.53 |

4 |

| T3 |

0.01 |

0.133 |

0.081 |

0.003 |

0.05 |

0.39 |

0.59 |

3 |

| T4 |

0.02 |

0.122 |

0.089 |

0.006 |

0.31 |

0.08 |

0.68 |

2 |

| HF |

0.02 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.36 |

0.21 |

0.26 |

6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).