1. Introduction

Within forest ecosystems, the interaction between host plants and phytophagous insects remains a central theme in forest protection research.

Juniperus przewalskii Komarov, an endemic alpine conifer on the northeastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [

1], exhibits a geographically restricted distribution confined to high-altitude mountains (2,600 ~ 4,300 m) ranging from the northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to the western edge of the Loess Plateau [

2]. This species adapts to extreme drought and low-temperature environments through traits such as a deep root system, scaly leaf structure, and the accumulation of secondary metabolites (e.g., flavonoids) [

3,

4]. It serves as a dominant constructive species within the montane forest-steppe ecotone [

5,

6]. Its cones provide the exclusive reproductive substrate for the juniper seed pest,

Megastigmus sabinae Xu et He (Hymenoptera: Torymidae), establishing a highly specialized parasitic relationship. This interaction system offers an ideal model for investigating plant-insect interaction and deciphering the spatiotemporal dynamics of host plant defenses versus insect counter-adaptations [

7]. Recent studies demonstrate that plants employ secondary metabolites as a key strategy in constructing chemical defense systems against seed and cone pests [

8,

9], while insects develop detoxification mechanisms, often involving metabolic plasticity, to overcome these plant defenses [

10]. However, our understanding of high-altitude juniper-pest systems remains limited. Specifically, the spatiotemporal coupling between dynamic defense strategies during cone development and insect counter-defense mechanisms remains unclear, as does the interaction between the dynamics of secondary metabolites in high-altitude Cupressaceae plants and the diverse enzyme activities of their insect pests.

Megastigmus sabinae and

Juniperus przewalskii exhibit a highly specific synergistic developmental relationship. Adults oviposit into healthy cones, and the larval stage, comprising five instars, extends from late August of the current year to late June of the following year. The majority of larvae overwinter predominantly as 2nd instar (with a minority overwintering as 1st or 3rd instars) [

11]. Larvae from the 1st to 4th instars bore into the endosperm, their development synchronizes with that of the host cones, culminating in the pupal stage, coinciding with the complete depletion of endosperm nutrients, resulting in hollow and abortion of cones [

12]. This protracted developmental period and synchrony render the larvae entirely dependent on cone resources throughout their development. However, it also exacerbates seed abortion in

J. przewalskii due to the barrier to natural regeneration. Current research primarily focuses on the biological characteristics and control techniques of

M. sabinae [

13]. Nevertheless, the physiological adaptation mechanisms underlying its interaction with the host plant remain unclear.

Plant secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids, coumarins, and steroidal compounds, play crucial roles in defending against feeding by herbivorous insects. Flavonoids exert insecticidal effects by inducing cytotoxicity or forming complexes with various enzymes, thereby impairing insect behavior and growth [

14,

15].

Picea spp. defend against

Pissodes strobi larvae by activating terpene-rich oleoresin chemical defenses and increasing the abundance of stone cells [

16]. This synergistic physical and chemical defense mechanism is prevalent in conifer cone defense mechanisms. However, systematic investigation into the temporal dynamics of secondary metabolites in Cupressaceae plants, particularly their correspondence with insect stages, remains lacking.

Research on insect adaptation strategies to plant defenses shows a multidimensional trend. Biochemically, insects rely on detoxifying enzyme systems, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450), glutathione S-transferases (GST), and carboxylesterases (CarE), to degrade plant antiherbivore chemical defenses [

17,

18]. Physiologically, they dynamically regulate digestive enzymes to cope with host nutrient limitations, enhancing physiological plasticity [

19]. From a genetic evolutionary perspective, certain oligophagous groups develop specific adaptation mechanisms through key gene mutations—for instance, oligophagous species within the noctuid genus

Spodoptera cannot feed on Poaceae plants containing the toxin DIMBOA (2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one) due to mutations of UGT genes (UDP-glycosyltransferases) [

20]. However, current research predominantly focuses on polyphagous Lepidoptera species [

20,

21,

22], with a paucity of systematic analysis on defense mechanisms in oligophagous Hymenoptera species. For example,

M. sabinae larvae complete their entire larval stage within the cones of

J. przewalskii, likely evolving unique physiological adaptation mechanisms and detoxification metabolic pathways. The molecular basis and ecological significance of these adaptations warrant further exploration.

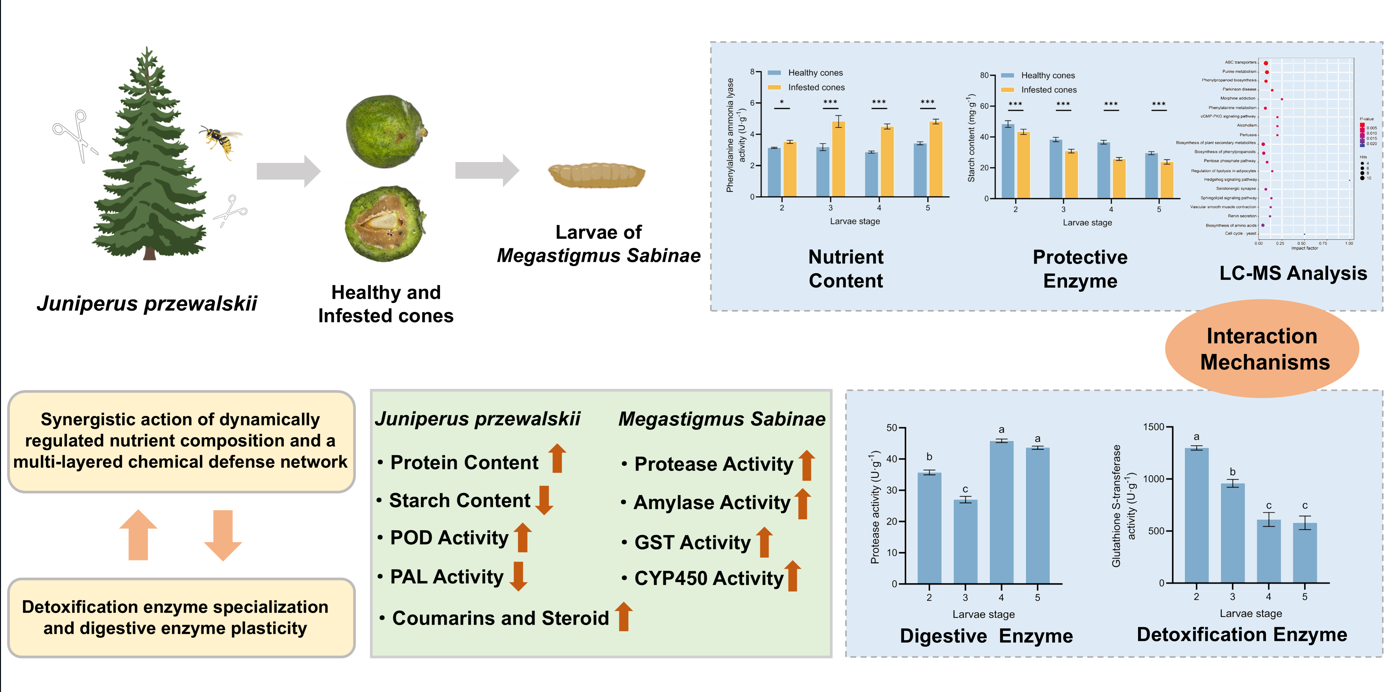

Based on this background, our study for the first time establishes a multi-level interaction system between a typical high-altitude tree species (J. przewalskii) and its oligophagous pest (M. sabinae), integrating nutrient content analysis, metabolomic analysis, and multi-category enzyme activity profiling. Primarily, we analyzed dynamic nutrient content and protective enzyme activities in cones following parasitism by M. sabinae larvae. Subsequently, based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) technology, we analyzed differential secondary metabolites in infested cones in response to larvae feeding. Finally, we determined the digestive and detoxifying enzyme activities of larvae during their synergistic development within the cones. This study aims to address the following scientific questions: (1) How do infested cones establish multi-layered defense through nutrient content remodeling, responsive regulation of protective enzyme activities, and temporal accumulation of secondary metabolites? (2) How do larvae achieve metabolic adaptation through dynamic modulation of digestive and detoxifying enzymes? (3) What are the quantitative coupling relationships between cone defense strategies and larval adaptation mechanisms? This work lays the foundation for elucidating the physiological adaptation strategies underpinning nutritional and chemical defense interactions formed during the long-term coevolutionary process between J. przewalskii and M. sabinae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Material and Host Plant Cones

Mature cones of J. przewalskii were collected from the forest stand in Toutan, Sunan Yugur Autonomous County, Zhangye City, Gansu Province (altitude: 2,920 m; 38°32′N, 100°14′E). Megastigmus sabinae insects were collected on six dates: August 25, 2021(i.e., egg stage); December 18, 2021(i.e., 1st instar); April 5, 2022(i.e., 2nd instar); May 10, 2022(i.e., 3rd instar); June 12, 2022(i.e., 4th instar) and July 3, 2022(i.e., 5th instar). For each collection, 1,000 cones were collected, transported to the laboratory, longitudinally bisected, and examined to distinguish healthy cones from infested cones. Both cone material and larvae from each stage were immediately frozen and stored at -80°C for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Nutrient Contents Analysis in Juniperus przewalskii Cones

2.2.1. Protein Content

Protein content in healthy and infested J. przewalskii cones across developmental stages was quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beijing Bairuiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experimental group included three biological replicates. Finally, using the function formula of the standard curve to calculate the protein concentration of each sample.

2.2.2. Starch Content

Starch content in healthy and infested

J. przewalskii cone tissues across developmental stages was quantified using the Plant Starch Content Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experimental group included three biological replicates. Starch content was calculated using the following formula:

Where C standard refers to the concentration of the Standard Solution, V sample is the total volume of the sample, N is the dilution factor of the supernate, and W is the fresh weight of the sample.

2.2.3. Crude Fat Content

Crude fat content of

J.przewalskii cone was determined by Soxhlet extractor method, which was invented by German scientist Franz Ritter von Soxhlet in 1879. First, about 1 g of healthy or infested cone was weighed and placed on the filter paper, wrapped, and fixed with cotton thread before marking. Then, the filter paper was put into the extraction bag, and the various parts of the instrument were assembled. Two-thirds of petroleum ether was added to the receiver, and heated under the condition of 60 ~ 75 ℃ water bath, so that the petroleum ether was continuously refluxed and extracted 8 times h

-1 for 6 ~ 8 h. Next, the receiving bottle was taken off, and the petroleum ether was recovered. When the residual petroleum ether in the receiving bottle was left only 1 ~ 2 mL, it was evaporated in a water bath, and then dried in an oven at 105 ± 5 ℃ for 2 h, until the drying device was cooled and weighed. Each experimental group included three biological replicates. Finally, crude fat contents of each sample were calculated by the formula following:

Where m1 refers to the quality of the receiving bottle and crude fat, m0 is the quality of the receiving bottle, and m2 is the quality of each sample.

2.3. Protective Enzyme Activity Analysis in Juniperus przewalskii Cone

2.3.1. Peroxidase Activity

Peroxidase activity in healthy and infested

J. przewalskii cone tissues across stages was quantified using the Peroxidase Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experimental group included three biological replicates. Peroxidase activity was calculated using the following formula, the activity of an enzyme was shown as U per g of fresh weight:

Where VRS refers to the total volume of the reaction system, V Sample quality is the quality of the sample; T is the response time (i.e., 20 min), W is the fresh weight of the tissue, VS is the total volume of the sample.

2.3.2. Phenylalamine Ammonia Lyase Activity

Phenylalanine ammonia lyase activity in healthy and infested

J. przewalskii cone tissues across stages was quantified using the Phenylalamine ammonia lyase Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experimental group included three biological replicates. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase activity was calculated using the following formula, the activity of an enzyme was shown as U per g of fresh weight:

Where W refers to the weight of the sample, VCE is the total volume of the crude extract, VS is the loading amount of the crude extract during determination, VRS is the total volume of the reaction system, T is the response time, △A=A determination − A blank.

2.4. LC-MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics and Differential Metabolite Screening in Juniperus przewalskii Cones

Metabolites in healthy and infested J. przewalskii cone seeds were analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS; Thermo Scientific Q Exactive HF-X) in two batches due to prolonged intervals between larval stages. Cones collected on December 18, 2021 (i.e., 2nd instar), April 5, 2022 (i.e., 3rd instar), and May 10, 2022 (i.e., 4th instar) were longitudinally dissected to separate healthy and infested seeds. Samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized, with specific procedures as follows. Briefly, 0.1 g of the J. przewalskii tissue is weighed and transferred into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube. Methanol containing L-2-chlorophenylalanine (4 mg kg-1; pre-cooled to −20°C) (Merck KGaA; Germany) was added for 30s vortex oscillation. After fully mixing, add 100 mg of glass beads to each centrifuge tube, then place them all in the tissue grinder (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; United States) and grind for 90 s at 60 Hz. Subsequently, ultrasonic treatment was performed at room temperature for 15 min, and centrifuged at 4 °C and 12000 rpm for 10 min, the supernate was filtered with a 0.22 μm membrane and detected by LC-MS, with three replicates performed.

In addition, some of the extracted samples to be tested were mixed into quality control (QC) samples to evaluate the stability and repeatability of the experimental method, and the QC inspection was performed on more than 10 experimental samples. The samples were eluted and determined by reference to the method of Want

et al. [

23].

Raw LC-MS data were converted to mzXML format using ProteoWizard version 3.0.8789 and processed via XCMS for peak alignment and normalization. Metabolites were annotated using the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, v5.0,

https://hmdb.ca), MassBank (v2023.12,

https://massbank.eu), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, Release 107.0,

https://www.kegg.jp), and LipidMaps (2024Q1 update,

https://www.lipidmaps.org), accessed on March 20, 2023. Only metabolites with QC showing relative standard deviation (RSD) < 30% across technical replicates and detection rates > 80% in biological samples were retained. Subsequently, differential metabolites between healthy and infested cones were identified based on statistical significance (

p-value), fold change, and the Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score. Metabolites with a

p-value < 0.05 and a VIP score > 1 were considered statistically significant.

2.5. Detoxication Enzyme Activity Analysis in Megastigmus Sabinae Larvae

First, prepare the tissue homogenate of the larvae. Every 10 larvae of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th instars in each treatment were divided into a group, with 5 replicates in each group. Then, the pre-cooled sample was homogenized in a homogenizer, and the supernatant was taken for subsequent determination. In this study, the activities of cytochrome P450 (CYP450), glutathione S-transferase (GST) and carboxylesterase (CarE) were determined to measure the detoxication enzyme activity in the larvae of M. Sabinae. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used in the determination, and the specific steps are taken as the example of the determination of GST activity.

The Insect Glutathione S-transferase ELISA Kit (Jingmei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to determine the GST activity in the larvae of M. Sabinae. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, samples, standard and Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) detection antibody were added to the micropores pre-covered with GST antibody, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and fully cleaned. Subsequently, under the action of TMB, the samples were first converted to blue with the catalyst of peroxidase, and last turned yellow, the color was shaded with the GST activity in the samples. Finally, the stopping solution was added, and the absorbance (OD value) was determined by a microplate reader at 450 nm. The linear regression curve was drawn with the standard concentration as the abscissa and the OD value as the ordinate, and the concentration of each sample was quantified according to the curvilinear equation.

2.6. Digestive Enzyme Activity Analysis in Megastigmus Sabinae Larvae

The protease activity, amylase activity and lipase activity of the larvae were determined to measure the digestive enzyme activity in this study, also based on the ELISA. The specific procedures were the same as the detoxication enzyme activity determination method above.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) was employed to analyze the differences in nutrient contents of J. przewalskii cones and the activities of protective enzymes. For the detoxication and digestive enzyme activities of M. sabinae larvae, a two-way analysis of variance (Two-way ANOVA) was applied. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons among different treatments to determine significant differences at the P < 0.05 level. Figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

The interaction between phytophagous insects and their host plants represents a central theme in ecological interaction research [

9]. Herbivory activates complex defense response networks in host plants [

9], while insects counter these defenses through adaptive adjustments in developmental strategies and detoxification metabolic systems [

24]. This study focuses on the unique interaction system between

Megastigmus sabinae larvae and

Juniperus przewalskii cones. Elucidating their multi-layered interaction mechanisms and physiological adaptation strategies provides novel insights into plant-insect co-defensive and adaptive evolutionary processes within high-altitude ecosystems.

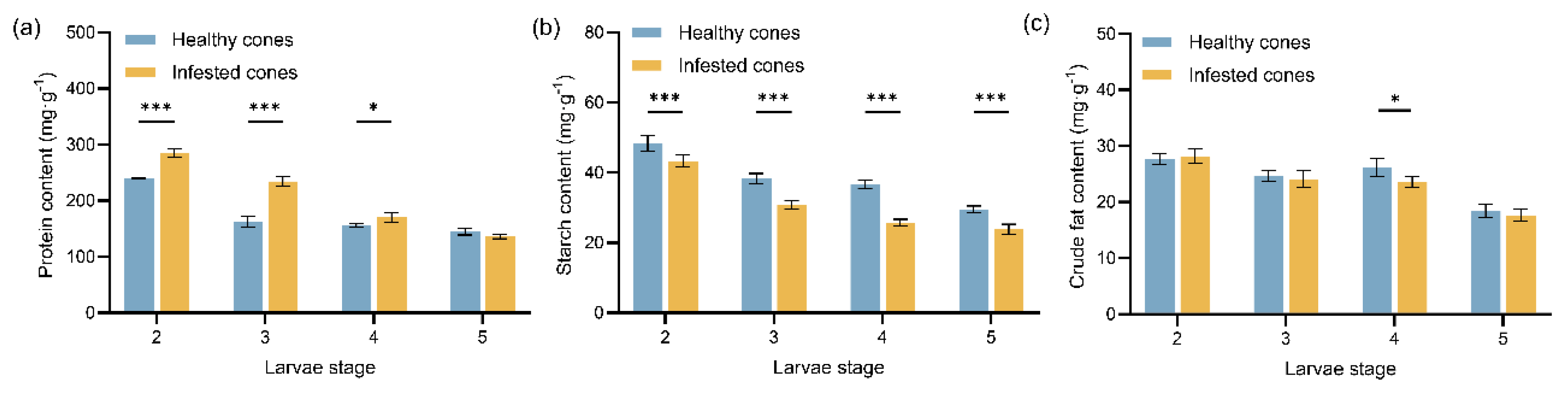

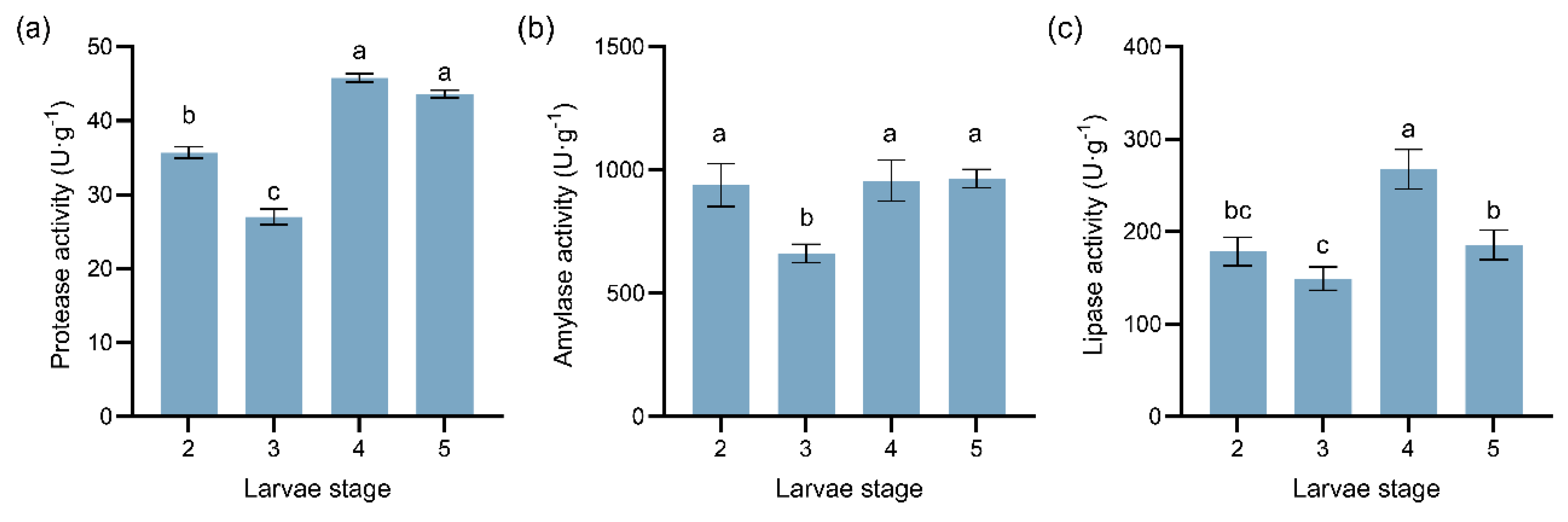

This study reveals, for the first time, that

J. przewalskii cones resist

M. sabinae larvae feeding through the synergistic action of dynamically regulated nutrient composition and a multi-layered chemical defense network. Concurrently, shifts in multiple enzyme activities in

M. sabinae larvae reflect their adaptive evolutionary responses to host plant defenses. Firstly, the protein content in infested cones was significantly higher than that in healthy cones, particularly during the early larvae instars (2nd~3rd). This likely results from

J. przewalskii inducing the synthesis and accumulation of specific proteins to interfere with larvae’s overwintering survival and post-diapause digestion. For instance, infested cones exhibited significantly higher levels of defensive protective enzymes (e.g., peroxidases, polyphenol oxidases). These enzymes likely inhibit insect digestive enzymes, reducing herbivore digestive efficiency (as evidenced by lower digestive enzyme activity in early instars) [

25], and increasing larval metabolic costs. Additionally,

J. przewalskii may produce protease inhibitors (PIs), and other defense-related proteins (e.g., pathogenesis-related proteins (PRs), chitinases) [

26,

27], further compromising larvae’s physiological processes. In response, larvae significantly downregulated protease activity, potentially to minimize these costs, demonstrating an adaptation to host defenses [

28]. Secondly, starch content decreased significantly in infested cones. This decline may reflect its conversion to soluble sugars to compensate for carbohydrate depletion following larval feeding, aligning with a “nutrient limitation” strategy [

29]. Compared to healthy cones, the reduced starch content in infested cones coincided with larvae amylase activity being significantly higher than protease and lipase activity. This suggests larvae may upregulate amylase activity to enhance the utilization efficiency of cone starch, preferentially consuming readily metabolizable starch while significantly downregulating lipase activity to conserve energy reserves for overwintering. This strategy is highly consistent with the “carbon-prioritizing and lipid-conserving strategy” observed in gall-inducing insects during overwintering [

30]. Analogous adaptations are seen in oligophagous seed pests like

Callosobruchus maculatus and

Plodia interpunctella [

31,

32], indicating oligophagous insects may overcome host nutrient limitations through metabolic plasticity. For example,

Eriogyna pyretorum enhances trypsin activity when feeding on hosts low in soluble protein content to acquire more protein [

19,

33]. Thirdly, the decrease in crude fat content in infested cones, coupled with significantly elevated larvae lipase activity during the 4th instar and the enrichment of novel steroid derivatives during the 3rd~4th instar feeding period, suggests

J. przewalskii may interfere with insect lipid metabolism (e.g., potentially inhibiting juvenile hormone synthesis). This could reduce available lipid nutrients for larvae, thereby delaying larval development [

34]. This phenomenon also highlights the larvae’s adaptive feedback to such liposoluble toxins.

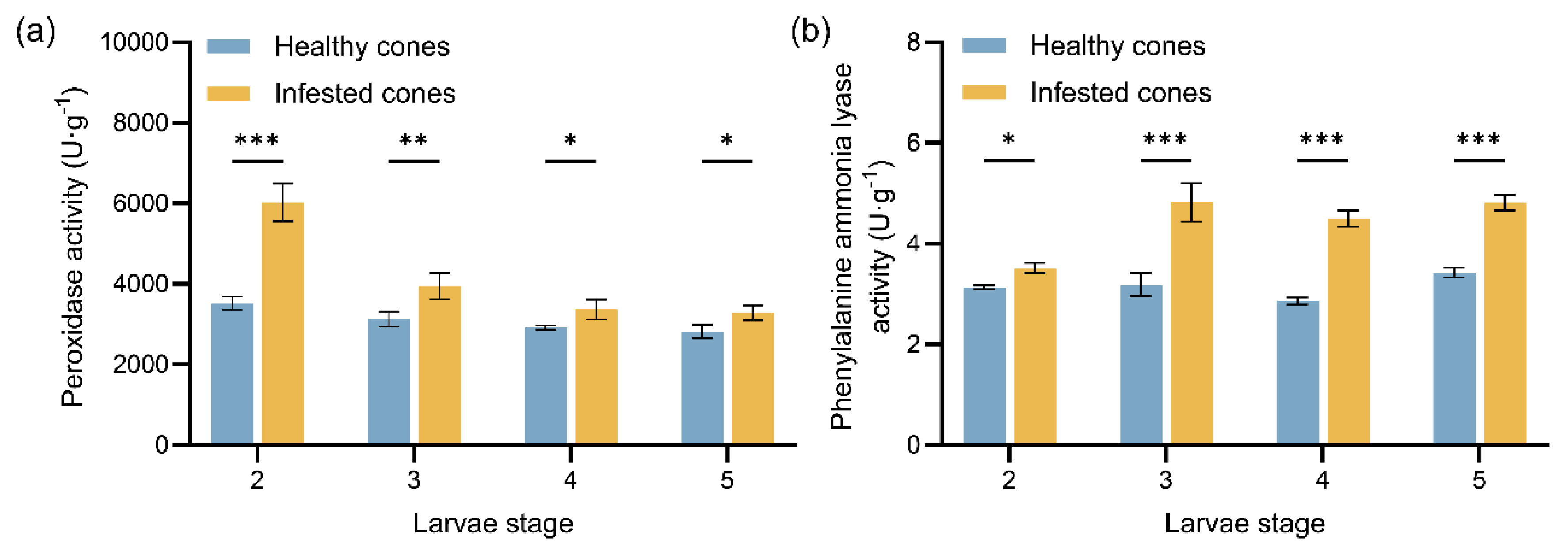

Furthermore, the temporal pattern of protective enzyme activity in cones indicates a “stage-specific division of labor” strategy. During the overwintering period (2nd instar), peroxidase (POD) activity was significantly elevated in infested cones. This likely serves to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulated prior to overwintering, induced by mechanical damage and insect saliva, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis [

35,

36]. Analogously,

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) feeding significantly induces enhanced POD activity in

Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper. As larval development progressed (3rd~5th instars), phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity significantly increased. This likely drives the sustained activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway [

37], promoting the accumulation of flavonoids and coumarins.

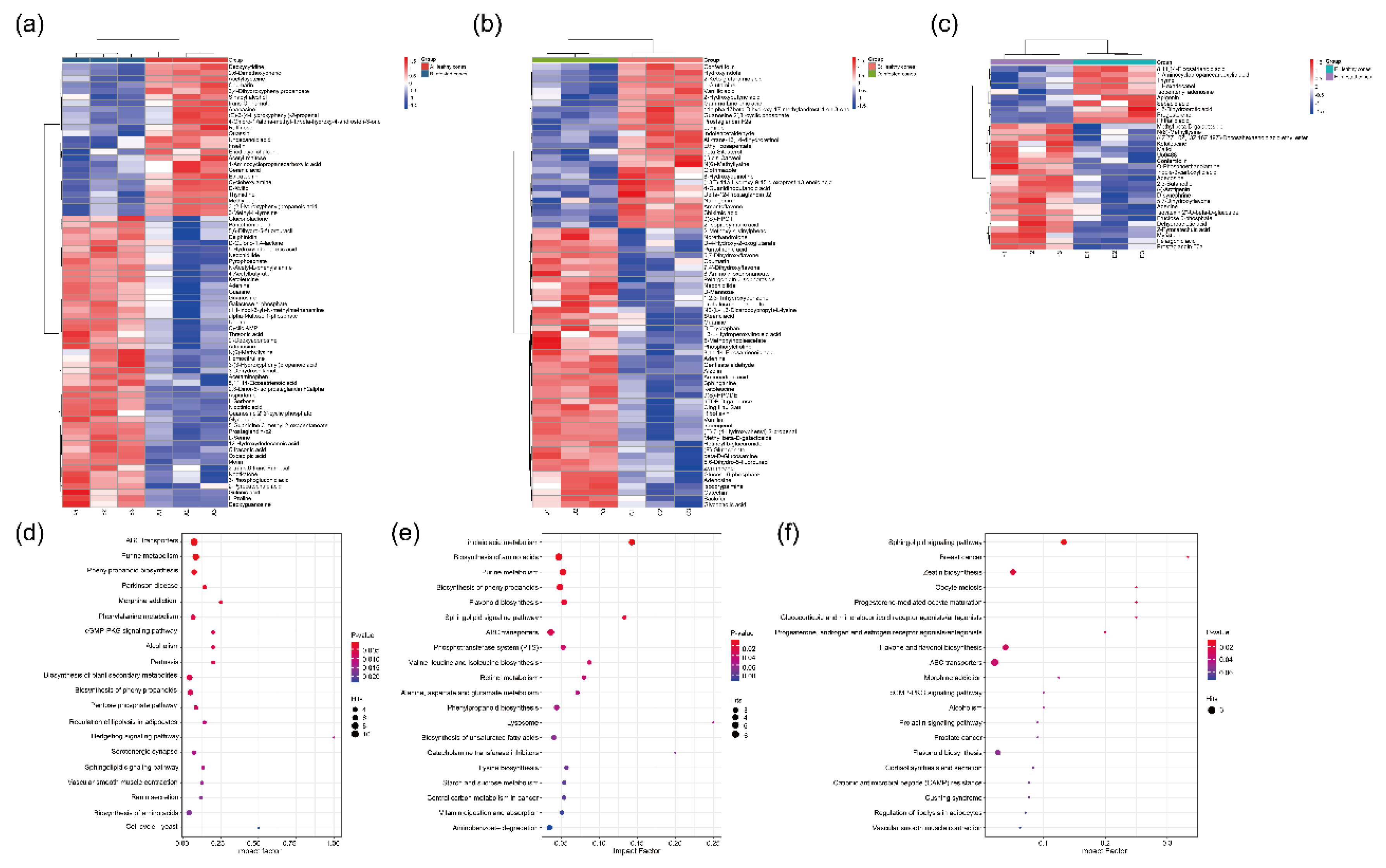

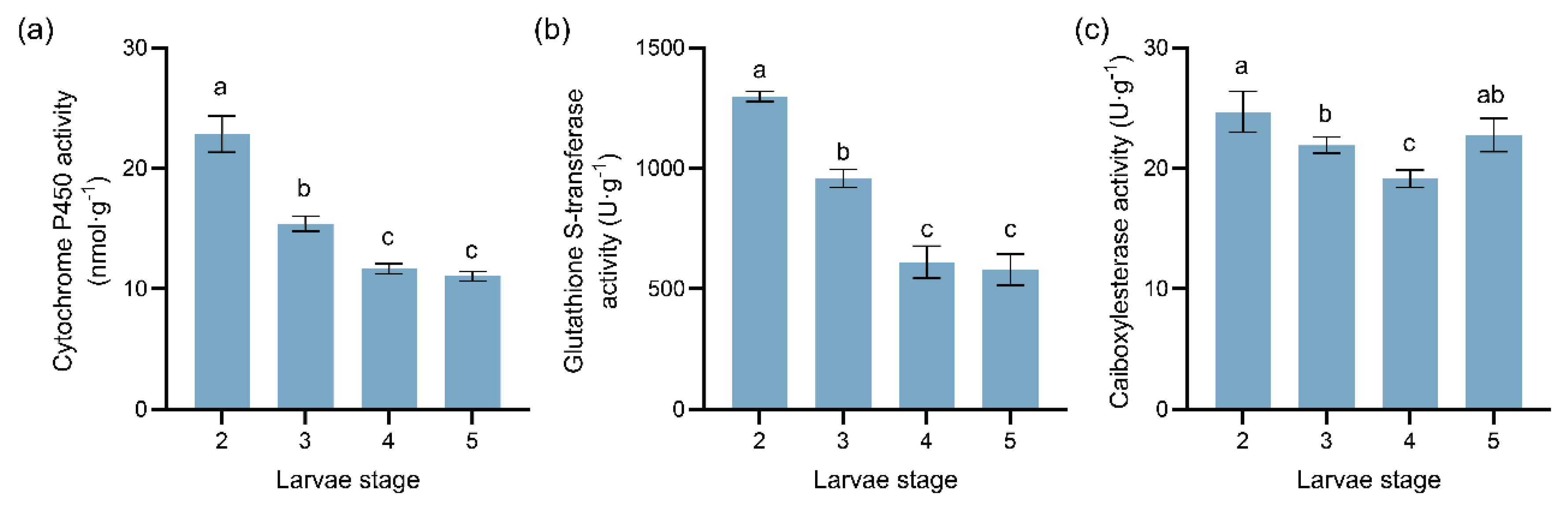

Detoxification enzyme activity data reveal a biphasic detoxification strategy in the larvae: the three major detoxification enzymes (CYP450, GST, CarE) exhibited peak activity during the early instar (2nd), followed by a significant decline as development advanced to later instars (4th~5th). This closely correlates with changes in secondary metabolites within infested cones: Early instar larvae (2nd) require elevated detoxification enzyme activity to counteract the host’s diverse array of secondary metabolites (e.g., coumarins and cinnamaldehyde derivatives). By the later instar (4th), larvae have largely adapted to the host cone environment, shifting focus towards accelerated growth and development. Concurrently, the variety of secondary metabolites upregulated by the host cones during the later larval stage was markedly reduced (25 types). The phenomenon of significantly higher digestive enzyme activities in later instar larvae (4th ~ 5th) compared to earlier instars (2nd~3rd) aligns with this adaptive shift. Additionally, winter low-temperature stress triggers a ROS burst and membrane lipid peroxidation within

J. przewalskii, leading to the accumulation of lipid peroxidation end-products (e.g., MDA) in the cones [

38]. This may compel

M. sabinae larvae to preemptively activate glutathione-S-transferase (GST) during the prolonged overwintering period (~200 days in the 2nd instar) as an antioxidant defense system. This activation counters ROS generated during environmental exposure, preventing oxidative damage to cellular components [

28,

39]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate larval adaptation to

J. przewalskii ’s multi-layered defenses through enzyme specialization strategies.

Leveraging LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics, this study deciphered the multi-pathway coordinated defense network in infested

J. przewalskii cones. Analysis revealed that differentially abundant metabolites in infested cones were significantly enriched in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, providing molecular-level corroboration for the observed PAL activity enhancement [

37]. The sustained accumulation of flavonoids confers potent defensive functions. Flavonoid accumulation causes midgut damage in

Helicoverpa zea larvae and disrupts the expression of key genes essential for maintaining gut health [

40]. It also influences the oviposition behavior of

Papilio xuthus on citrus juvenile leaves [

41]. Coumarins, specifically enriched during the 2nd instar in this study, can stimulate plant defense responses by triggering ROS generation and activating immune-related genes and signaling pathways (e.g., the salicylic acid-dependent pathway). These compounds possess multifaceted anti-insect activities, including inhibiting various insect processes and hindering nucleic acid synthesis. This aligns with the high levels of detoxification enzymes like GST maintained in early instar larvae (2nd) [

42]. Such synchronized responses represent a key interactive mechanism ensuring synchronized development between the plant and insect. Furthermore, significant activation of the ABC transporter pathway unveils a spatial regulation mechanism in plant defense. For instance, transmembrane transport of secondary metabolites like terpenoids may be enhanced [

43]. The novel enrichment of steroid derivatives during the 3rd~4th instar feeding period further supports this hypothesis, potentially facilitating the targeted accumulation of toxins at larval feeding sites [

44]. Moreover, the abnormal activation of the retinol metabolism pathway suggests

J. przewalskii may implement defense by potentially disrupting insect molting hormone signaling [

45].

In summary, this study systematically deciphers the intricate and sophisticated physiological interaction mechanisms between J. przewalskii and its specialist herbivore, M. sabinae. Juniperus przewalskii employs a comprehensive defense strategy involving the dynamic modulation of cone nutrient composition, the temporal activation of protective enzymes, and the construction of a multi-layered chemical defense network. Conversely, M. sabinae larvae exhibit remarkable adaptive capabilities, effectively countering host-imposed nutritional constraints and chemical challenges through the precise regulation and strategic division of labor among digestive and detoxification enzymes. This tight coupling of plant defense and insect counter-defense across temporal and metabolic dimensions represents a core manifestation of their long-term coevolution within the high-altitude habitat. This study not only provides novel perspectives for understanding the interaction mechanisms between oligophagous insects and their specific hosts but also contributes significant physiological and molecular evidence to the theory of plant-insect coevolution in alpine ecosystems. However, it is important to note that this study was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, omitting the influence of complex field variables such as temperature fluctuations and natural enemy interactions. Future research will integrate field experiments to validate the ecological applicability of these findings and delve deeper into the functional differentiation of detoxification enzyme genes and the interference mechanism of the host retinol pathway on insect hormone signaling. These insights will furnish new evidence for the coevolutionary dynamics and bidirectional physiological adaptation mechanisms within plant-oligophagous pest systems in high-altitude ecosystems, laying a crucial foundation for developing ecologically sound pest management strategies based on host chemical defenses.

Figure 1.

Mean values (± standard error) of the three major nutrient contents in healthy and infested cones of Juniperus przewalskii at different larval stages: (a) Protein content; (b) Starch content; (c) Crude fat content. Asterisks specify that the values were significantly different: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Figure 1.

Mean values (± standard error) of the three major nutrient contents in healthy and infested cones of Juniperus przewalskii at different larval stages: (a) Protein content; (b) Starch content; (c) Crude fat content. Asterisks specify that the values were significantly different: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Figure 2.

Mean values (± standard error) of protective enzyme activities in healthy and infested cones of J. przewalskii at different larval stages: (a) Peroxidase (POD) enzyme activity; (b) Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) enzyme activity. Asterisks specify that the values were significantly different: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Figure 2.

Mean values (± standard error) of protective enzyme activities in healthy and infested cones of J. przewalskii at different larval stages: (a) Peroxidase (POD) enzyme activity; (b) Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) enzyme activity. Asterisks specify that the values were significantly different: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Figure 3.

Differential metabolites (DMs) between healthy and infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of different instars. Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) between healthy and infested cones: (a) 2nd instar; (b) 3rd instar; (c) 4th instar. The color represents the level of metabolite content; the redder the color, the higher the content, and the bluer the color, the lower the content. KEGG pathway analysis of DMs between healthy and infested cones: (d) 2nd instar; (e) 3rd instar; (f) 4th instar. The color of the dots represents the level of enrichment, with redder indicating a more significant enrichment. The size of the dots represents the number of DMs annotated to the pathway.

Figure 3.

Differential metabolites (DMs) between healthy and infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of different instars. Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) between healthy and infested cones: (a) 2nd instar; (b) 3rd instar; (c) 4th instar. The color represents the level of metabolite content; the redder the color, the higher the content, and the bluer the color, the lower the content. KEGG pathway analysis of DMs between healthy and infested cones: (d) 2nd instar; (e) 3rd instar; (f) 4th instar. The color of the dots represents the level of enrichment, with redder indicating a more significant enrichment. The size of the dots represents the number of DMs annotated to the pathway.

Figure 4.

Dynamic changes in the activities of three digestive enzymes at different instars of Megastigmus sabinae larvae: (a) Protease activity, (b) Amylase activity, (c) Lipase activity. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences: P < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 4.

Dynamic changes in the activities of three digestive enzymes at different instars of Megastigmus sabinae larvae: (a) Protease activity, (b) Amylase activity, (c) Lipase activity. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences: P < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 5.

Dynamic changes in three detoxification enzyme activities at different instars of M. sabinae larvae: (a) Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) activity, (b) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity, (c) Carboxylesterase (CarE) activity. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences: P < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 5.

Dynamic changes in three detoxification enzyme activities at different instars of M. sabinae larvae: (a) Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) activity, (b) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity, (c) Carboxylesterase (CarE) activity. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences: P < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Table 1.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 2nd instar.

Table 1.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 2nd instar.

| Differential metabolite category |

Type(s) |

Cumulative values of

VIP scores |

| Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

9 |

14.24 |

| Organic oxygen compounds |

7 |

12.32 |

| Fatty acyl |

5 |

7.91 |

| Pregnenolone lipids |

4 |

5.88 |

| Pyrimidine nucleosides |

3 |

4.88 |

| Benzoylpropionic acid |

3 |

4.85 |

| Benzene and substituted derivatives |

3 |

4.61 |

| Phenols |

3 |

4.60 |

| Purine nucleosides |

3 |

4.49 |

| Flavonoids |

2 |

3.36 |

| Keto acid and derivatives |

1 |

3.34 |

| Hydroxyl acid and derivatives |

2 |

3.31 |

| Purine nucleotides |

2 |

3.18 |

| Imidazole pyrimidine |

2 |

2.83 |

| Pyridine and derivatives |

1 |

1.75 |

| Coumarin and derivatives |

1 |

1.65 |

| Organic nitrogen compounds |

1 |

1.58 |

| Lactone |

1 |

1.55 |

| Cinnamic acid and derivatives |

1 |

1.53 |

| Indole and derivatives |

1 |

1.53 |

| Alcohols and polyols |

1 |

1.51 |

| Non-metallic oxyanion compounds |

1 |

1.51 |

| Cinnamaldehyde |

1 |

1.42 |

| Sports Doping Drugs |

1 |

1.39 |

| Diazobenzene |

1 |

1.38 |

Table 2.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 3rd instar.

Table 2.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 3rd instar.

| Differential metabolite category |

Type(s) |

Cumulative values of

VIP scores |

| Fatty acyl |

10 |

17.11 |

| Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

7 |

11.93 |

| Flavonoids |

6 |

10.30 |

| Organic oxygenated compounds |

5 |

8.97 |

| Keto acid and derivatives |

3 |

5.21 |

| Phenol |

3 |

5.10 |

| Prealcohol lipids |

3 |

4.95 |

| Indole and derivatives |

3 |

4.85 |

| Purine nucleoside |

2 |

3.45 |

| Nitrogen-containing organic compounds |

2 |

3.41 |

| Imidazole pyrimidine |

2 |

3.35 |

| Benzene and derivatives |

2 |

3.29 |

| Steroids and derivatives |

2 |

3.22 |

| Cinnamaldehyde compounds |

1 |

1.85 |

| Alcohols and polyols |

1 |

1.82 |

| Endogenous Metabolites |

1 |

1.78 |

| Pteran dinitrogen heterocyclic compounds |

1 |

1.71 |

| Carbohydrate and its conjugates |

1 |

1.70 |

| Natural Products / Medicines |

1 |

1.70 |

| Dinitrogen heterocyclic compounds |

1 |

1.70 |

| Triphenyl compounds |

1 |

1.66 |

| Hydroxyl acid and derivatives |

1 |

1.66 |

| Lactone |

1 |

1.66 |

| Alkaloids |

1 |

1.66 |

| Precription drugs |

1 |

1.62 |

| Pyrimidine nucleoside |

1 |

1.61 |

| Coumarin and derivatives |

1 |

1.53 |

| Organic oxides |

1 |

1.51 |

Table 3.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 4th instar.

Table 3.

Types of differential metabolites (DMs) categories and cumulative values of VIP scores in infested Juniperus przewalskii cones herbivory by Megastigmus Sabinae larvae of the 4th instar.

| Differential metabolite category |

Type(s) |

Cumulative values of

VIP scores |

| Fatty acyl |

5 |

9.07 |

| Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

5 |

8.73 |

| Benzene and substituted derivatives |

3 |

5.80 |

| Organic oxygenated compounds |

3 |

5.45 |

| Flavonoids |

2 |

3.53 |

| Indole and derivatives |

1 |

1.99 |

| Steroids and steroid derivatives |

1 |

1.97 |

| Furan lignans |

1 |

1.93 |

| Organic phosphoric acid and derivatives |

1 |

1.88 |

| Pyran compounds |

1 |

1.78 |

| Sports doping drugs |

1 |

1.76 |

| Prealcohol lipids |

1 |

1.75 |

| Purine nucleoside |

1 |

1.73 |

| Benzo-dioxane |

1 |

1.68 |

| Imidazole pyrimidine |

1 |

1.66 |

| Keto acid and derivatives |

1 |

1.65 |