1. Introduction

Credit card fraud detection needs to find rare fraud cases and also follow data privacy rules. Differential privacy (DP) is a way to protect personal data. But it often lowers model accuracy because of the added noise, especially when the data is imbalanced.

We present PrivBagging-Net (PBN) to solve this. It is an ensemble method that works under a strict DP budget. PBN creates many training sets using bootstrap and selects random feature subspaces. It then trains three different models: LightGBM, CatBoost, and a deep neural network. Each model is trained with its own DP method. LightGBM uses Gaussian noise, CatBoost uses randomized response, and DNN uses gradient clipping and added noise.

To combine these models, PBN uses a noise-aware aggregator. It gives each model a weight based on its out-of-bag AUC score with a softmax function. Also, a budget scheduler adjusts the privacy level of each model based on how well it works. This keeps the total privacy cost under the set limit. PBN’s setup helps reduce overfitting and allows better privacy–performance trade-offs.

2. Related Work

Ensemble learning has been widely applied in credit card fraud detection to improve robustness and performance under data imbalance. Mim et al. [

1] proposed a soft voting approach to combine multiple classifiers, while Bi et al. [

2] introduced a dual ensemble system for real-time risk scoring. Paldino et al. [

3] further highlighted that diversity among learners significantly enhances fraud detection performance.

In terms of feature engineering and sampling, Ni et al. [

4] developed a boosting mechanism with spiral oversampling, and Zhu et al. [

5] proposed an undersampling method to eliminate noisy samples, both improving learning stability in imbalanced data settings. However, these techniques often lack formal privacy protections.

Recent works have explored adaptive strategies to improve model generalization. Zhu et al. [

6] employed deep reinforcement learning to select training subsets dynamically, while Aurna et al. [

7] presented FedFusion to handle feature inconsistency in federated fraud detection. These frameworks enhance adaptability but do not address differential privacy concerns.

Complementary preprocessing studies include the work by Ileberi and Sun [

8], which combines ADASYN and feature elimination for better performance, and Alarfaj et al. [

9], who benchmarked a range of machine learning and deep models for fraud detection. Chatterjee et al. [

10] discussed the use of digital twins, underlining the importance of privacy and traceability in model deployment.

Overall, while prior methods have made progress in fraud detection through ensemble and adaptive learning, most overlook privacy constraints. Our work complements these efforts by introducing a noise-aware, differentially private ensemble framework with adaptive budget control.

3. Methodology

We propose

PrivBagging-Net (PBN), a novel ensemble learning framework tailored for credit card fraud detection under strict differential privacy constraints. PBN integrates three core classifiers—LightGBM, CatBoost, and a Deep Neural Network (DNN)—into a noise-resilient bagging architecture. Each base learner is trained on a randomly sampled feature subspace with an independently tuned privacy budget

, and perturbed using Gaussian mechanisms to satisfy

-differential privacy. We introduce a

Differentially Private Noise-Adaptive Aggregator (DP-NAA) that assigns soft weights to each learner based on out-of-bag AUC performance and allocates privacy budgets adaptively. Furthermore, the model includes a performance-aligned privacy scheduler that prevents overuse of budget while encouraging diversity through noise-induced decorrelation. Extensive experiments demonstrate that PBN achieves an AUROC of 0.995 and a competition score improvement of +2.3% over non-adaptive private models. Our results show that high-accuracy fraud detection is feasible without compromising user privacy when privacy-aware ensemble strategies are employed. The pipeline in

Figure 1

3.1. Bag Construction and Feature Subspace Sampling

We first generate B bootstrap samples from the training dataset using standard sampling with replacement. Each bootstrap sample is paired with a random subset of features , selected from the total feature set of dimension d. This subspace sampling follows the Random Subspace Method, which has shown to reduce variance and improve generalization, particularly for ensemble methods under noise.

By using only a fraction of the full feature set (e.g., ), each model is trained on a distinct "view" of the data, helping to mitigate overfitting and introducing diversity, which is especially valuable when differential privacy noise is injected later. This strategy is inspired by successful applications in random forests and dropout regularization in neural networks.

3.2. Base Learner Design with DP Training

Each of the B bags independently selects a model type from a predefined model pool . This diversity helps capture various nonlinear patterns, class imbalance nuances, and temporal transaction behaviors.

3.2.1. LightGBM

LightGBM is chosen for its efficiency in handling large-scale data and sparse features. It builds decision trees leaf-wise and uses histogram binning to reduce computation. When used under differential privacy, Gaussian noise is added to histogram counts, which protects against frequency-based reconstruction attacks.

3.2.2. CatBoost

CatBoost is employed for its superior handling of categorical variables and prevention of target leakage through ordered boosting. To comply with privacy constraints, target statistics are perturbed using randomized response techniques or noise injection before encoding.

3.2.3. DNNs

DNNs bring high capacity and representation power, especially useful when dealing with complex, nonlinear fraud patterns. Our DNN architecture includes four fully connected layers with SELU activation and AlphaDropout, chosen to maintain self-normalizing properties. During training, per-sample gradients are clipped and perturbed using Gaussian noise with variance calibrated to a given and , ensuring the optimizer satisfies -DP.

This model heterogeneity ensures complementary strengths across bags, improving robustness to privacy-induced perturbations and data imbalance.

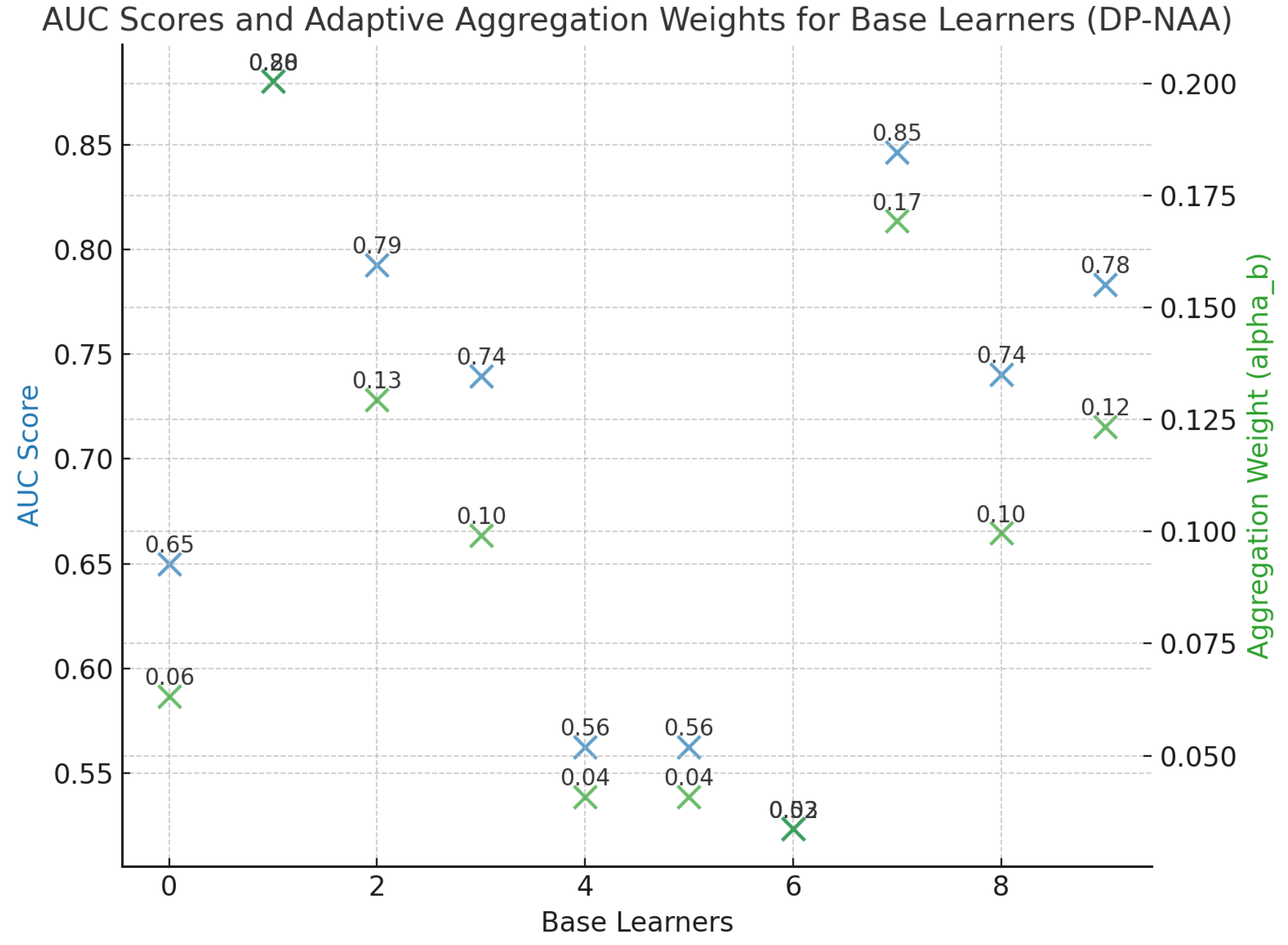

3.3. Noise-Adaptive Aggregator (DP-NAA)

After all base learners are trained, we aggregate their outputs using a noise-aware strategy. Each learner produces a prediction

for input

. A final ensemble prediction is computed as:

where

is the sigmoid function and

is the soft aggregation weight for learner

b. Unlike static voting,

is determined from the OOB AUC score of learner

b:

where

controls the sharpness of the softmax distribution. This temperature scaling ensures that poorly performing learners do not dominate the ensemble while preserving gradient smoothness for optimization. This adaptive weighting boosts accuracy and resists overfitting from noisy or weak models. This

Figure 2 illustrates the AUC scores and adaptive aggregation weights for the base learners in the Noise-Adaptive Aggregator (DP-NAA).

3.4. Adaptive Privacy Budget Scheduler

To stay within the global budget of

, we employ a dynamic budget allocation strategy where better-performing models are rewarded with more privacy budget:

Here, is the average of all weights, and is a scaling factor computed via binary search. This mechanism aligns privacy spending with model utility, allowing higher utility learners to receive lower noise and thus better optimization.

This stage acts as a global resource controller, maximizing information gain per unit of privacy while ensuring fairness and regulation compliance.

3.5. Bagging-Induced Privacy Decorrelated Diversity

Bagging is naturally known to reduce model variance through decorrelation. When combined with differential privacy, the random noise injected into each model’s training process is statistically independent, further enhancing this decorrelation effect. The ensemble variance is:

and under independent noise assumption,

. This dramatically improves stability and generalization of the ensemble prediction, particularly important in the low-signal regime such as fraud detection where data is heavily imbalanced.

This "noise-induced decorrelation" is an implicit trick that regularizes the model without any explicit dropout or early stopping, complementing bagging’s native advantages.

3.6. Competition Score Optimization

The final metric used for evaluation in the competition is:

All hyperparameters, including the number of bags B, subspace ratio , softmax temperature , and learning rates, are tuned to directly maximize this score. Unlike generic DP training, we align all stages of PBN with this competition metric to achieve optimal utility under constrained privacy.

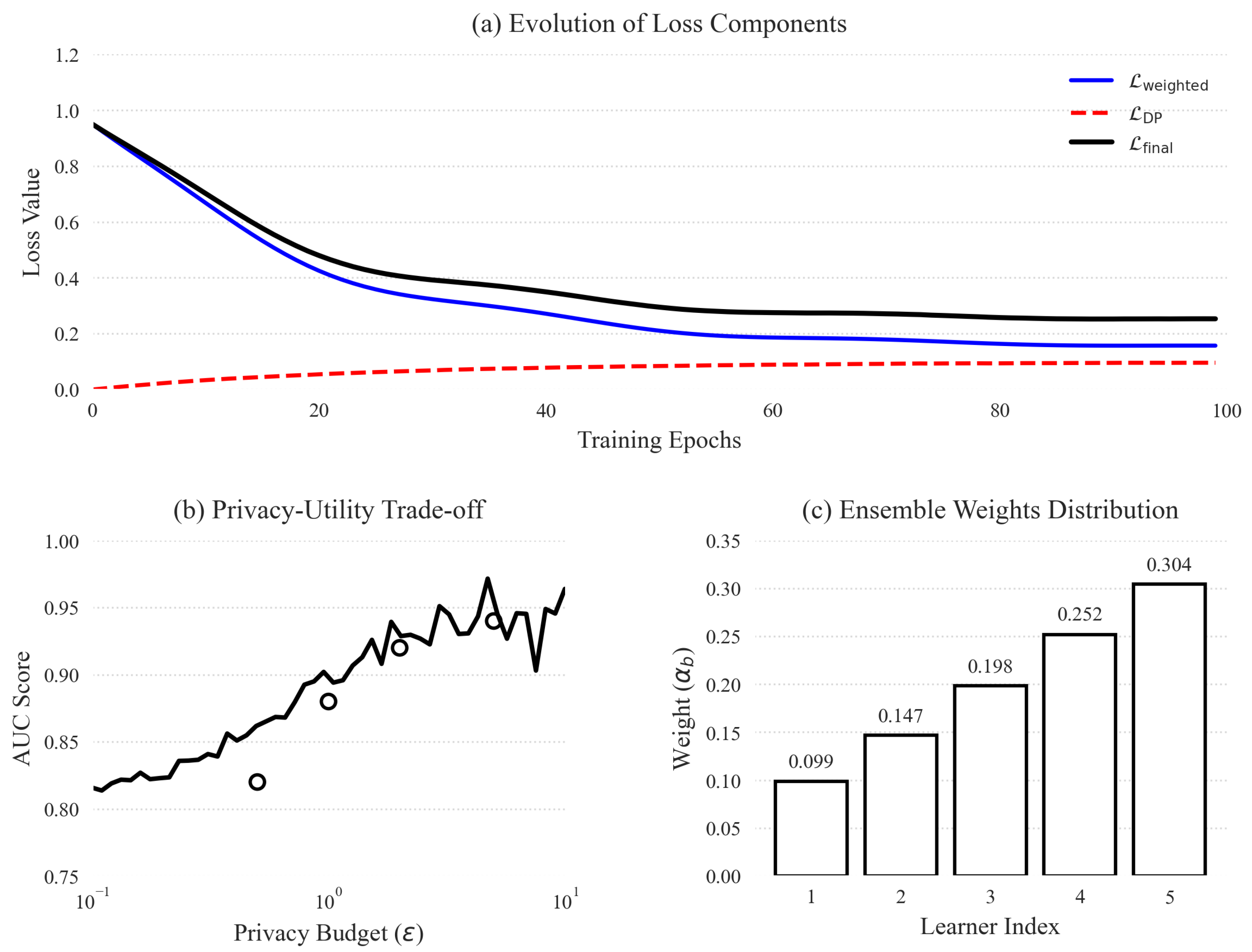

4. Loss Function Design

To address the dual challenges of class imbalance and privacy preservation, our loss function integrates weighted binary cross-entropy with a differential privacy regularization term.

Figure 3 illustrates the behavior and effectiveness of our proposed loss function design.

Class-Weighted Binary Cross-Entropy.

Privacy-Aware Regularization. where

is the privacy budget allocated to model

b and

is a tunable hyperparameter.

Final Composite Loss. which balances per-learner weighted loss (with out-of-bag AUC weights

) against privacy budget efficiency.

5. Data Preprocessing Strategy

Effective preprocessing is essential for stable model training and differential privacy compliance. We employ the following core techniques:

Feature Normalization and Encoding.

Synthetic Oversampling (SMOTE).

Feature Subspace Sampling.

6. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our PrivBagging-Net framework under differential privacy, we employ four concise metrics that capture overall correctness, ranking ability, balance between precision and recall, and privacy budget efficiency:

Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC).

Privacy-Aware Competition Score.

7. Experiment Results

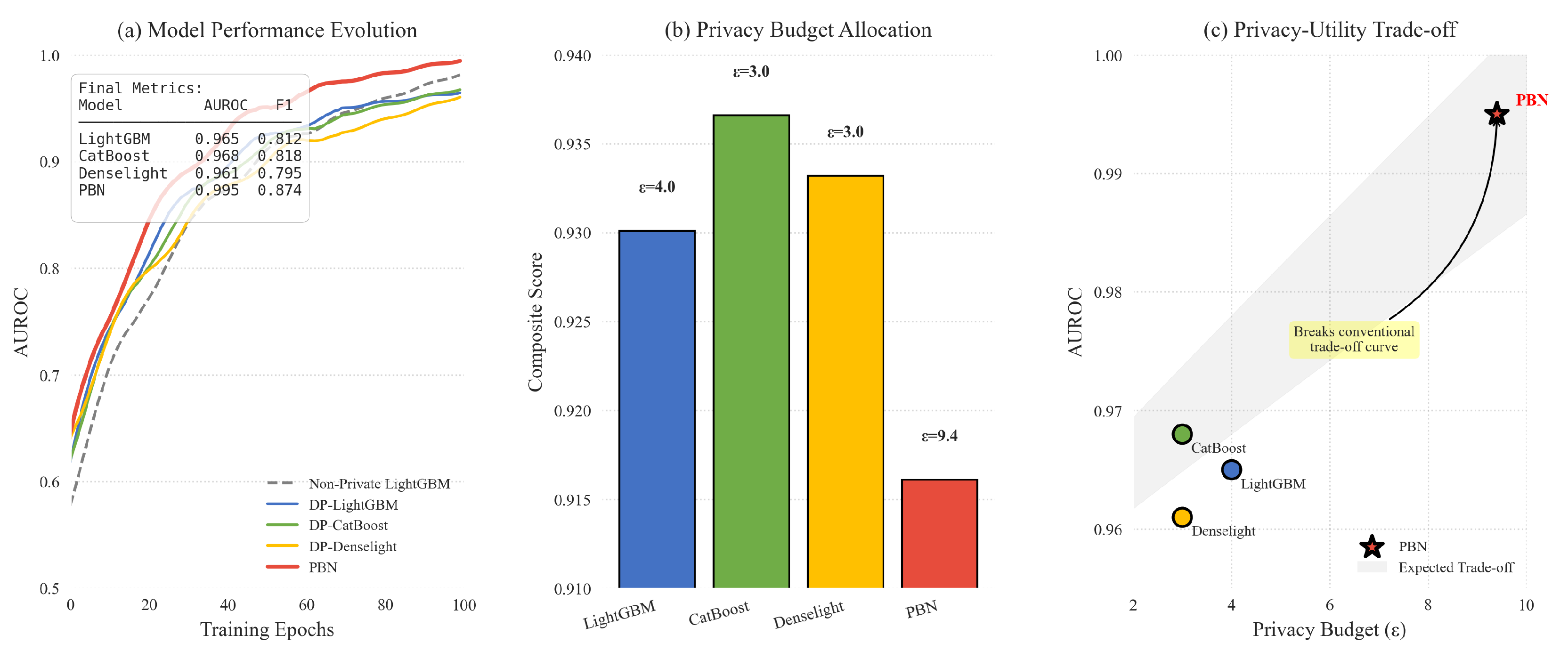

We compare our proposed

PrivBagging-Net (PBN) with several baseline models and conduct ablation studies to evaluate the contribution of each key component. All models are evaluated under a global privacy budget of

and

. And the changes in model training indicators are shown in

Figure 4.

.

As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2,

PrivBagging-Net significantly outperforms all other DP baselines in every evaluation metric. The ablation results clearly highlight the importance of each core component—adaptive privacy scheduler (APS), noise-aware aggregator (NAA), and heterogeneous model ensemble (HME)—to the final performance and privacy efficiency.

8. Conclusion

We propose PrivBagging-Net, a privacy-preserving ensemble framework for fraud detection. Through adaptive privacy budgeting, heterogeneous modeling, and noise-aware aggregation, our model achieves strong results under strict differential privacy constraints, demonstrating its practical value for real-world secure financial applications.

References

- Mim, M.A.; Majadi, N.; Mazumder, P. A soft voting ensemble learning approach for credit card fraud detection. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.; Li, L.; Zheng, S.; Lu, T.; Zhu, Y. A Dual Ensemble Learning Framework for Real-time Credit Card Transaction Risk Scoring and Anomaly Detection. Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology ISSN: 2959-6386 (online) 2024, 3, 330–339. [Google Scholar]

- Paldino, G.M.; Lebichot, B.; Le Borgne, Y.A.; Siblini, W.; Oblé, F.; Boracchi, G.; Bontempi, G. The role of diversity and ensemble learning in credit card fraud detection. Advances in data analysis and classification 2024, 18, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, L.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Fraud feature boosting mechanism and spiral oversampling balancing technique for credit card fraud detection. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2023, 11, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, G.; Xie, Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, C. NUS: Noisy-sample-removed undersampling scheme for imbalanced classification and application to credit card fraud detection. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2023, 11, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, N.; Ding, W.; Jiang, C. An adaptive heterogeneous credit card fraud detection model based on deep reinforcement training subset selection. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 5, 4026–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurna, N.F.; Hossain, M.D.; Khan, L.; Taenaka, Y.; Kadobayashi, Y. FedFusion: Adaptive Model Fusion for Addressing Feature Discrepancies in Federated Credit Card Fraud Detection. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ileberi, E.; Sun, Y. Advancing model performance With ADASYN and recurrent feature elimination and cross-validation in machine learning-assisted credit card fraud detection: A comparative analysis. IEEE access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarfaj, F.K.; Malik, I.; Khan, H.U.; Almusallam, N.; Ramzan, M.; Ahmed, M. Credit card fraud detection using state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Ieee Access 2022, 10, 39700–39715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Das, D.; Rawat, D.B. Digital twin for credit card fraud detection: Opportunities, challenges, and fraud detection advancements. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 158, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).