1. Introduction

In recent years, disaster events have been occurring frequently on a global scale, presenting obvious characteristics of multi-hazard coupling. Disasters such as the forest fires in Australia that lasted for months, the accelerated melting of Antarctic glaciers, the large-scale influenza outbreak in the United States, the severe locust plague in East Africa, and the extreme cold wave in Canada have occurred one after another, and these sudden-onset disasters have posed a serious challenge to the safe operation of mega-cities. At the same time, despite the continuous improvement of public health conditions, the situation of prevention and control of sudden-onset infectious diseases remains severe due to environmental changes, population movement and other factors. From SARS, avian influenza to the COVID-19 epidemic, public health emergencies have frequently impacted the normal operation order of society (Zhang et al., 2022; Habibi et al., 2023). Especially during the COVID-19 epidemic, the composite disaster scenario formed by the superposition of a single disaster and an epidemic exposed the inadequacy of the traditional emergency medical rescue model in terms of resource deployment and facility layout (Remko et al., 2020).

Under the multi-hazard coupling scenario, the optimal allocation of emergency medical resources faces unprecedented challenges. Studies have shown that scientific and reasonable medical facility layout and resource deployment strategies can significantly improve rescue efficiency and reduce casualties (Karmaker et al., 2021). However, most of the existing studies focus on single disaster scenarios, ignoring the optimization of emergency medical resources under the coupling of natural disasters and public health events(Liu et al., 2019). In particular, how to construct an efficient hybrid rescue model has become a critical issue to be solved when considering multiple constraints such as dynamic changes in the affected area, uncertainty in the distribution of the injured, and limited medical resources (Govindan et al., 2019). Therefore, for the problem of emergency medical resource optimization under multi-hazard coupling scenarios, this paper proposes a decision-making method that integrates mixed integer programming and heuristic algorithms. By constructing a mixed integer programming (MIP) model that considers time cost and resource constraints, the multilevel decision-making problem of medical resource allocation, location of rescue facilities and casualty transportation is systematically solved. Considering the complexity of the model solution, a hybrid heuristic algorithm of particle swarm optimization (PSO) and variable neighborhood search (VNS) is innovatively designed, which is able to effectively respond to the solution needs of problems of different scales.

This study not only expands the theoretical approach of optimal allocation of emergency resources in uncertain environments, but also provides an operational decision support tool for practical rescue work. The introduction of this decision support tool, especially in the context of multi-hazard coupling, provides a more efficient hybrid rescue model for emergency rescue, which is able to realize rapid resource deployment and facility construction at the early stage of a disaster, thus improving the rescue response efficiency and reducing the casualties and losses after the disaster. This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related research progress;

Section 3 describes the background and characteristics of the problem; Section 4 constructs the mathematical model and performs linearization;

Section 5 details the design of the algorithm for PSO and VNS;

Section 6 verifies the validity of the model and algorithm through numerical experiments; and

Section 7 sums up the conclusions of the study and looks ahead to the direction of future research.

2. Literature Review

In the emergency medical rescue system, the scientific siting of medical facilities and the optimal allocation of resources are the key factors to guarantee the timeliness of rescue in uncertain situations (Boonmee et al., 2017). In recent years, with the intensification of the phenomenon of multi-hazard coupling, how to realize hybrid allocation of medical resources (e.g., fixed facility and mobile unit synergy, air-land transportation, etc.) in the dynamically evolving disaster chain has become a focus of academic attention. This section presents a short literature review covering two research areas: (i) the scientific siting problem of medical facilities, and (ii) the optimization problem of emergency medical resources.

2.1. Scientific Siting of Medical Facilities

The siting problem of medical facilities directly affects the distribution efficiency of emergency supplies and the speed of post-disaster response. Existing studies mainly focus on site selection-distribution co-optimization. Wan et al. (2023) proposed a bipolar emergency medical material distribution model, which not only optimizes the transportation time cost but also establishes a coupled relationship between distribution center site selection and transportation path planning by integrating hierarchical analysis and genetic algorithm. Similarly, Chang et al. (2023) developed a rescue point distribution model based on a dynamic road network with an improved genetic algorithm that provides a new method for real-time responsiveness assessment for medical facility siting. In terms of medical facility network planning, Lai et al. (2021) bi-objective stochastic optimization model innovatively incorporates the siting of transfer points and medical supply distribution centers (MSDCs) into a unified framework, whereas Moadab et al. (2023) systematically constructed a long-term siting decision system for medical centers, shelters, and supply facilities in a metropolitan area.Voigt et al. (2024) further considered the problem of locating temporary medical facilities in disaster scenarios, and their integer planning model provides a theoretical basis for the resilient layout of emergency medical facilities.

It is worth noting that the spatial configuration of emergency units also affects the effectiveness of medical facility location, and the multi-objective heuristic approach proposed by Fadaki et al. (2022) provides decision support for the rational layout of 24-hour emergency units, while the two-way distribution model developed by Deng et al. (2023) based on the proximity principle validates the spatial accessibility criterion for medical facility location from the perspective of end-of-pipe distribution. However, there are still obvious limitations in the existing studies.First, most siting models fail to adequately consider the differentiated needs under multi-hazard scenarios; second, the assumption of homogenization of transportation modes restricts the practical applicability of siting scenarios; and lastly, there is a gap in the research on synergistic optimization of facility siting with multi-modal transportation resources. These limitations point to innovative directions for future research on healthcare facility siting, especially the resilient siting strategy under multi-hazard coupling scenarios, which needs to be explored in depth.

2.2. Optimization of Emergency Medical Resources

In recent years, research on emergency medical resource optimization has made significant progress in responding to sudden disasters. In terms of resource allocation model construction, the dual standard model (DSM) combined with genetic algorithm (GA) developed by Nosrati-Abarghooee et al. (2023) provides an innovative solution to solve the problem of reliable service allocation under the limited conditions of medical rescue vehicles. These studies have significantly improved the reliability of emergency medical services by optimizing vehicle resource allocation. In terms of uncertainty handling, the mixed integer planning (MIP) model constructed by Ghasemi et al. (2019) for earthquake disasters innovatively integrates five key uncertainties such as the affected area, medical facilities, and temporary centers, etc. Yılmaz et al. (2023) further adopt a stochastic demand modeling approach to ensure the coverage level of the emergency medical facilities through risk metrics, which provide a resource optimization provides a quantitative basis. In the study of disaster pre-positioning strategies, the two-stage stochastic mixed integer planning (SMIP) model proposed by Shahparvari et al. (2022) is not only applicable to disaster response such as hurricanes, but also makes emergency medical resource allocation more scientific and reasonable through the introduction of service quality constraints. The study of Enayati et al. (2021) expands the optimization method of material allocation in the recovery phase of a disaster.

2.3. Research Gap

In a multi-hazard coupling situation, optimizing the allocation of emergency medical resources is the key to guaranteeing the timeliness of rescue and improving the emergency response capability. Scientific siting of medical facilities and rational allocation of resources play a crucial role in post-disaster rescue. The current limited urban emergency medical rescue reserves require us to establish an efficient material distribution system to meet the challenges of various sudden disasters. However, although the traditional three-tier supply chain network is suitable for regional material dispatching (Wang et al., 2022), it often faces many difficulties such as surging data demand and high computational complexity when facing extreme situations such as large-scale epidemics (Jahani et al., 2022). Studies have shown that the direct distribution model of “distribution center-disaster site” can better adapt to the needs of large-scale emergency management, and can rapidly build an emergency supply chain network in cross-city collaboration to efficiently respond to the government’s unified scheduling (Zheng et al., 2021). This model relies on a complete supply chain, including suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and end-users (Helo & Hao et al., 2022), and needs to be combined with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence to enhance its resilience and ensure its efficient operation in disaster situations. Drawing on the findings of power network outage analysis (Toorajipour et al., 2021) and human resource optimization (Tirkolaee et al., 2023), the construction of an intelligent healthcare distribution system has become an important breakthrough to enhance emergency response capabilities. In this context, there has been some progress in research on scientific siting of medical facilities and optimal allocation of resources, but most of the studies seldom consider the linkage between pre-disaster prevention and post-disaster relief, and ignore the effects of multiple factors such as time cost, rescue penalty cost, limited resources, dual capacity constraints, and disaster uncertainty in multi-hazard coupling scenarios. As shown in Table 1. Comparison of this paper with related literature., despite the progress of existing studies, current research still faces several challenges. First, most models do not adequately consider resource shortages under extreme disaster scenarios; second, there are relatively few cross-regional and multi-hazard synergistic optimization studies; and finally, the real-time dynamic adjustment mechanism has not yet been improved. These challenges point out the direction for future research in the field of emergency medical resource optimization, especially in the application of intelligent algorithms and multi-objective collaborative optimization, which have important research value. Especially under the coupling of multiple disasters, how to efficiently integrate emergency medical resources and guarantee the timeliness of rescue is still a difficult problem to be solved. In this process, the introduction of hybrid rescue model will provide a new perspective and method for the optimization of emergency medical resources, especially in resource deployment, dynamic optimization and timeliness guarantee under multi-hazards and multi-contexts.

Table 1.

Comparison of this paper with related literature.

Table 1.

Comparison of this paper with related literature.

| Reference |

Major factors in the model |

Problem Type |

Decision |

Model Type |

Multi Period |

Multi Objective |

| Cost |

Time |

Risk |

Resources |

L/A |

R |

In |

C |

UC |

|

Chang et al.(2023)

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

MILP |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Peng et al.(2023)

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

MILP |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Liu et al. (2019)

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

LP |

|

✓ |

|

Deng et al.,(2023)

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

BLPM |

|

✓ |

|

Enayati et al.,(2021)

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

MILP |

✓ |

|

|

Wang et al. (2022)

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

MILP |

✓ |

✓ |

| Alshurideh(2022) |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

BLPM |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Hao et al., (2022)

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

MILP |

|

|

| Toorajipour(2021) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

LP |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Shahparvari et al., 2022

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

MINLP |

✓ |

|

|

Tirkolaee et al., (2023)

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

FMO |

✓ |

✓ |

| This study |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

MILP |

✓ |

|

Aiming at these problems, this paper constructs a mixed integer programming (MIP) model aiming at minimizing the distribution cost on the basis of previous studies. The objective function of the model aims to minimize the distribution cost, covering the transportation time cost of rescuing the injured and the penalty cost of waiting for treatment. In order to solve the problem of reasonable distribution of emergency medical resources, the model integrates the scientific siting of temporary aid stations and emergency medical facilities, optimizes the allocation of medical resources, and makes accurate decisions on key issues such as the transportation of the injured. Further, the model ensures that the rescue tasks can be efficiently executed under multiple disaster scenarios by reasonably constraining the requirements of timeliness of post-disaster rescue and the finiteness of medical resources. In the treatment of uncertain demand, this paper adopts a scenario-based stochastic planning approach to consider the more random demand fluctuations in multi-disasters, which improves the adaptability of the model to complex disaster scenarios. In order to solve this complex model effectively, this paper combines particle swarm optimization (PSO) and variable neighborhood search (VNS) algorithms, and improves the solution efficiency and solution quality through the joint application of multiple algorithms. This study provides a theoretical basis for the hybrid rescue model of emergency medical resources and a new perspective for optimization decision-making in future disaster rescue.

3. Background to the Issue

Taking the 2022 Luding 6.8 magnitude earthquake in Sichuan, China, and the superimposed Xin Guan epidemic prevention and control event as a typical example, the coupling effect of the compound disaster significantly exacerbated the operational pressure on the emergency medical system. The earthquake caused the collapse of buildings, resulting in a large number of open trauma injuries, while epidemic control measures limited the movement of people and centralized treatment. This “natural disaster-epidemic” pattern of double impact reveals a common challenge for modern emergency response systems in complex and changing environments (Ahmad et al., 2023). The difficulty of responding to global health crises is increasing, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that with climate change and virus mutation, the probability of the world experiencing a “natural disaster + infectious disease” compound crisis will increase by 37% in the next five years, which requires that the emergency healthcare resource allocation model not only has the ability to respond to the aftermath of disasters, but also needs to have the ability to respond to multiple types of disasters. This requires that the emergency medical resource allocation model not only has the ability to respond to disasters, but also has the ability to respond to multiple disasters. Therefore, a rapid and effective medical resource allocation and rescue model is especially critical after a disaster.

In the context of such disasters, the construction of a three-level gradient medical network becomes a key path to reduce mortality. Specifically:

(1) Basic temporary relief stations (such as the tent hospitals set up after the Sichuan earthquake in China) need to undertake the functions of initial screening of injuries, isolation of infections, and emergency treatment, etc. Their locations should take into account a number of factors, such as road accessibility, division of infected areas, and the availability of regional medical resources;

(2) The designated hospitals are responsible for receiving seriously injured patients who need surgery, but need to reserve 20%-30% of beds to cope with potential outbreaks;

(3) In the event that the scale of casualties reaches 10,000 people (e.g., Wenchuan Earthquake) or in the event of mass infections, then modularly constructed square-cabin hospitals (e.g., Wuhan Vulcan Mountain Hospital in China) should be activated. The standard configuration of these square-cabin hospitals should include special facilities for epidemic prevention, such as negative pressure wards and mobile CT, in order to cope with the complex situation of compound disasters.

It is important to note that the competition for resources among the tertiary nodes will create a dynamic game. Constraints such as the drug inventory of the temporary aid station, the number of ECMO equipment in the hospital, and the bed turnover rate of the square-bay hospital collectively form a complex multidimensional decision space (Zheng et al., 2022; Tippong et al., 2022). This complex system faces multifaceted modeling challenges: first, multilevel network coupling. The affected point H can simultaneously transfer the injured to multiple temporary stations, which in turn transfer the lightly injured to hospital K, while the seriously injured need to be sent directly to the square cabin hospital J. Such a “1→N→M” topology results in an exponential growth of decision variables, which increases the complexity of resource allocation and optimization decisions. Second, the transportation paradox under epidemic prevention constraints. For example, in the Luding earthquake in China, helicopters can quickly transfer the injured, but may trigger the risk of cross-infection; negative pressure ambulances are safe, but have limited capacity, so it is necessary to balance the timeliness and safety through a multi-objective optimization model to ensure that the transport efficiency and the safety of epidemic prevention are taken into account. Third, uncertainty quantification. To address this challenge, we innovatively construct a hybrid FTA-AHP evaluation framework. Seventy-eight congestion risk factors (including epidemic-specific factors such as nucleic acid testing delays) were identified through fault tree analysis (FTA), and the weights of the factors were calculated using fuzzy hierarchical analysis (AHP), thus outputting a dynamically-adjusted diversionary prioritization index for the disaster area. These breakthrough optimization methods provide a new theoretical basis and practical path for solving the emergency decision-making dilemma in “black swan events”.

In summary, the hybrid rescue model of emergency medical resources in composite disaster environments, especially in multi-hazard coupling scenarios, faces high complexity and uncertainty. Through innovative multi-objective optimization and uncertainty quantification methods, the rescue efficiency and rationality of resource allocation can be effectively enhanced, thus minimizing the losses caused by disasters. These studies not only provide scientific decision support for future emergency rescue in similar disasters, but also provide a new research direction for the optimization of the emergency management system.

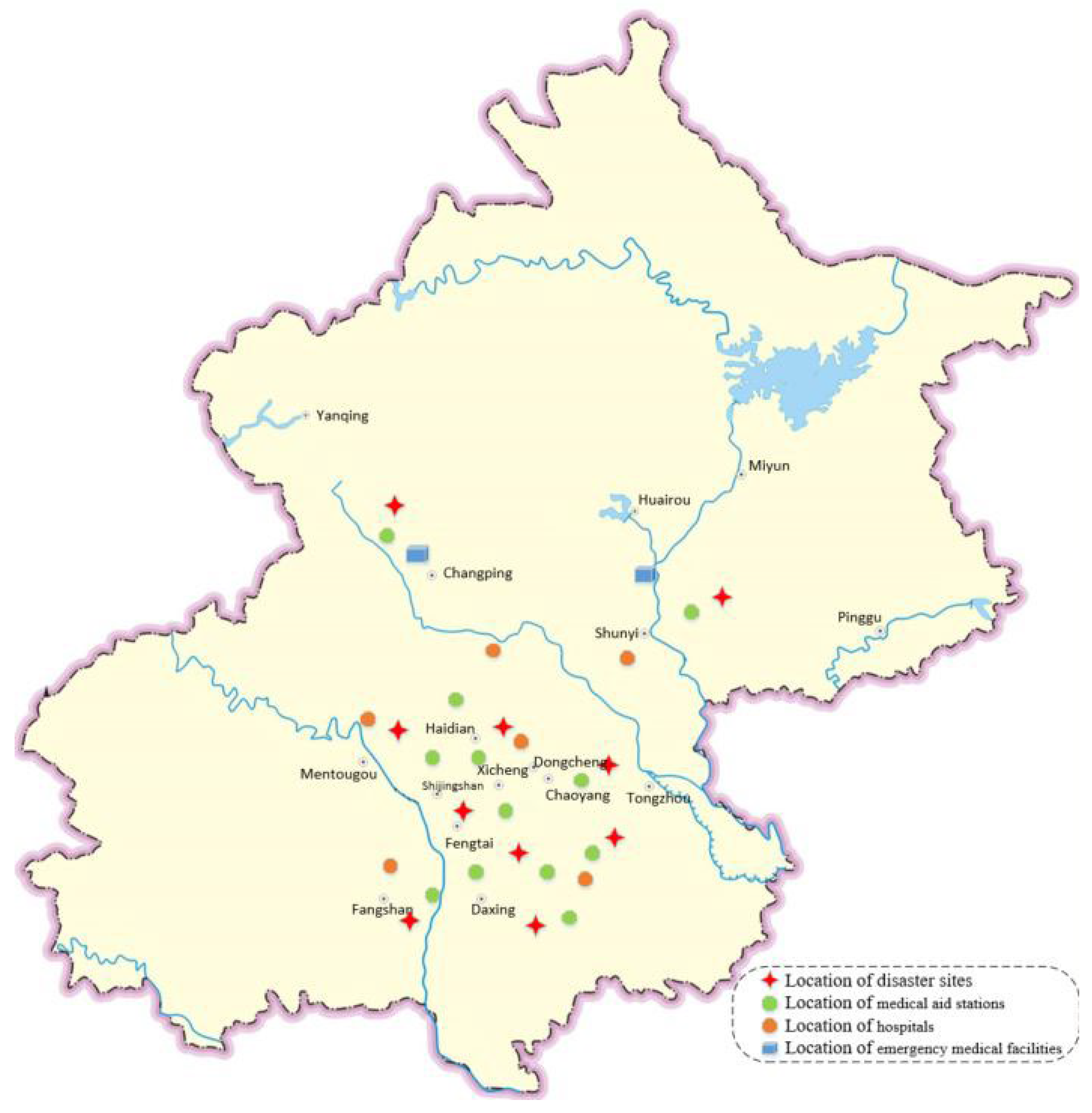

Figure 1. Candidate location of emergency medical facilities in Beijing.depicts the frequently affected areas, hospitals, temporary relief stations and candidate locations for emergency medical facilities. As can be seen from the figure, emergency medical facilities are mainly concentrated in the peripheral areas of the city, while the affected areas are widely distributed and scattered. If the injured are sent to hospitals directly from the affected areas, this will not only lead to a significant decrease in the timeliness of rescue, but also may lead to excessive strain on hospital resources and insufficient medical capacity. Therefore, under such circumstances, the most effective rescue model is to first send the injured in the affected area to the temporary relief station, through the initial screening and emergency treatment, and then according to the assessment of their injuries, decide whether to transfer to the nearest hospital for further treatment. Such a model can avoid over-concentration of hospital resources and enhance the overall effectiveness of medical rescue while ensuring the timeliness of rescue. However, it is important to note that the path of treatment for the injured not only depends on the distance and transportation conditions, but is also closely related to the severity of the injuries. In some cases, if the injury is more serious and geographically reasonable, the casualty can be sent directly from the affected area to a closer hospital, avoiding the delay of resource transfer in the middle of the journey. Therefore, the uncertainty of the injured in the affected area, the uncertainty of road transportation and other factors make the problem more complex, especially in the context of multi-hazard coupling. The decision-making process under such multiple uncertainty scenarios actually involves a complex siting and scheduling problem, in which not only the optimality of resource allocation needs to be considered, but also the balance between the rescue timeframe and resource use needs to be evaluated under uncertainty conditions. As a result, this problem is a typical NP-hard problem and needs to be solved in a dynamic and complex post-disaster environment. In multi-hazard coupling scenarios, such as the intertwining of earthquake and epidemic, the traditional single-emergency medical rescue model is no longer able to meet the demand for rapid, precise, and efficient resource deployment. Therefore, how to formulate an optimal medical resource deployment plan in the complex disaster context, combining multiple factors such as geography, transportation, and classification of the injured, has become a key issue to be solved in the field of emergency management.

Figure 1.

Candidate location of emergency medical facilities in Beijing.

Figure 1.

Candidate location of emergency medical facilities in Beijing.

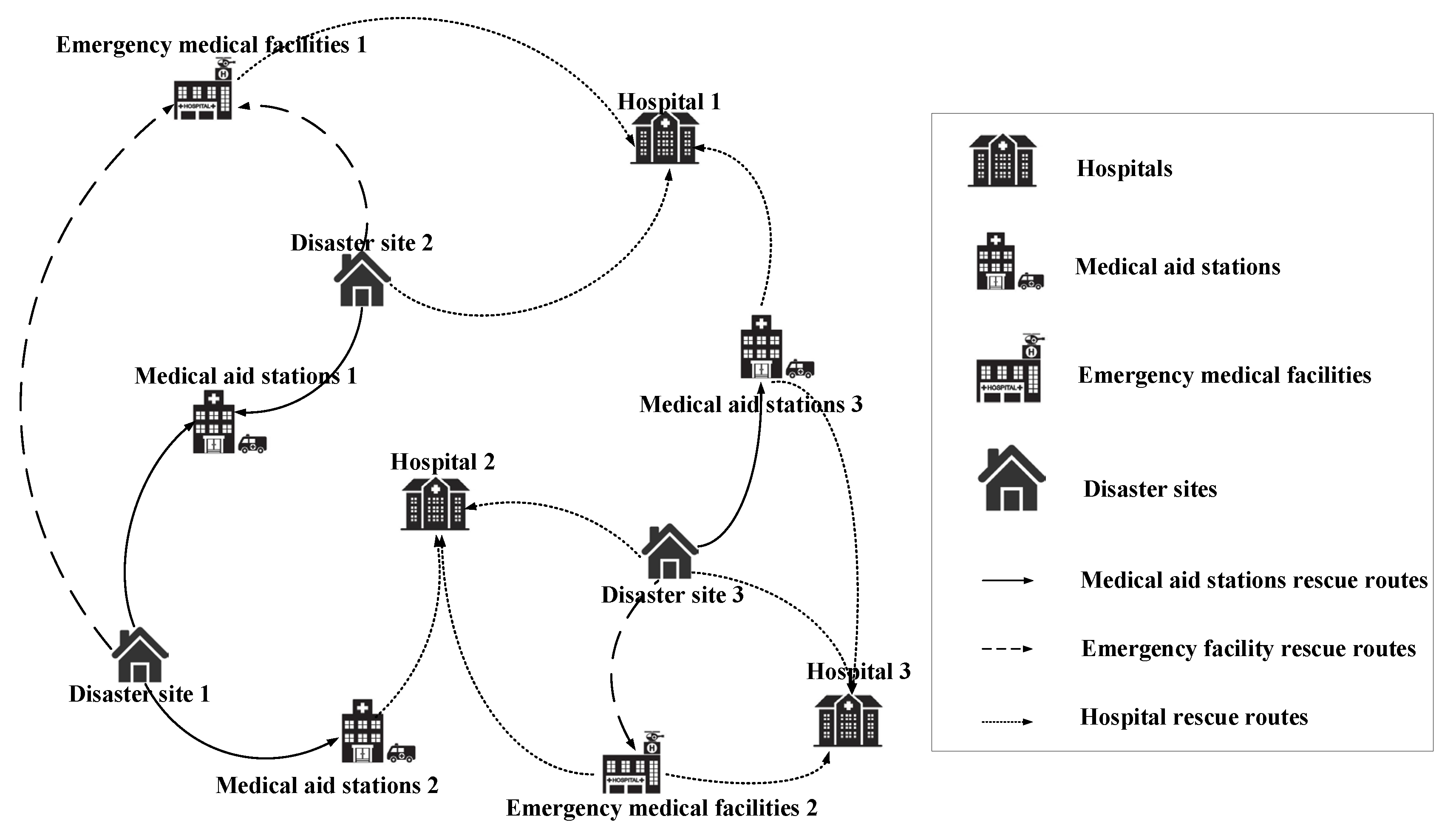

As an example, Figure 2. Network between affected areas, temporary emergency relief stations, emergency relief facilities, hospitals.shows a scenario of the transportation process of the injured in an emergency medical network, if there are three affected areas, three hospitals, three temporary relief stations and two emergency medical facilities. Depending on the location of the regions, people with different levels of injuries can be transported through the affected regions to the temporary relief stations, or directly to the hospitals or emergency medical facilities. Among them, after being rescued at the temporary relief stations, depending on the condition of the injured, they can also be transferred to hospitals or emergency medical facilities. Through scientific and reasonable medical resource allocation and transportation of the injured, the treatment rate of the injured can be greatly improved and the losses caused by the disaster can be reduced. In summary, this paper studies an integration problem for emergency medical rescue. The next section gives a mixed integer planning model, which takes into account the uncertainty of the disaster, the uncertainty of the material demand in the disaster area and the uncertainty of the injured.

Figure 2.

Network between affected areas, temporary emergency relief stations, emergency relief facilities, hospitals.

Figure 2.

Network between affected areas, temporary emergency relief stations, emergency relief facilities, hospitals.

4. Model Description

4.1. Model Parameters

4.1.1. Sets

Index of candidate temporary rescue station.

Set of candidate temporary rescue stations.

Index of candidate emergency medical facility.

Set of candidate emergency medical facilities.

Index of hospital.

Set of hospitals.

Index of disaster area.

Set of disaster areas.

Index of scenario.

Set of scenarios.

Index of wounded type.

Set of wounded types.

Index of temporary rescue station size.

Set of temporary rescue station sizes.

Index of emergency medical facility size.

Set of e emergency medical facilities sizes.

4.1.2. Parameters

Probability of occurrence of disaster scenario.

Distance from disaster areato temporary rescue station.

Distance from temporary rescue stationto emergency medical facility.

Distance from temporary rescue stationto hospital.

The degree of injury of the wounded acceptable to hospital.

The degree of injury of the wounded acceptable to medical facility.

The degree of injury of the wounded type.

The speed of the vehicle.

The capacity of hospitalto accommodate the wounded.

Hospital overload capacity factor.

Maximum storage capacity of temporary rescue stationof size.

Minimum storage capacity of temporary rescue stationof size.

Maximum storage capacity of medical facilityof size.

Minimum storage capacity of medical facilityof size.

The number of wounded typein the disaster areaunder scenario.

Cost coefficient of penalty for the number of people exceeds the capacity of the hospital.

A sufficiently large positive number artificially set by user for model use.

4.1.3. Decision Variables

Binary, equals to 1 if temporary rescue stationof sizeis established.

Binary, equals to 1 if medical facilityof sizeis established.

Binary, equals to 1 if wounded typetransport from disaster areato temporary rescue stationin scenario.

Binary, equals to 1 if wounded typetransport from temporary rescue stationto medical facilityin scenario.

Binary, equals to 1 if wounded typetransport from temporary rescue stationto hospitalin scenario.

Float, quantity of wounded typetransport from disaster areato temporary rescue stationin scenario.

Float, quantity of wounded typetransport from temporary rescue stationto medical facilityin scenario.

Float, quantity of wounded typetransport from temporary rescue stationto hospitalin scenario.

4.2. Mathematical Model

(1) The cost of transportation time to rescue the wounded

(2) The cost of waiting penalty time to rescue the wounded

The objective function of this model is the minimization of the total cost, which includes Cost of transport time to rescue the wounded and Waiting time penalty cost to rescue the wounded. This model also considers uncertainty by introducing scenarios of multiple disasters. Constraints (2) ensure that at most one temporary rescue station can be established at any candidate point. Constraints (3) ensure that at most one emergency medical facility can be established at any candidate point. Constraints (4) indicates that all the wounded in the affected area were transported to the temporary rescue station. Constraints (5) guarantee that the number of wounded transported from the disaster area to the temporary rescue station meets its capacity. Constraints (6) guarantee that the number of wounded transported from the disaster area to the emergency medical facility meets its capacity. Constraints (7) describe that the number of wounded transported from the temporary rescue station to the hospital is less than or equal to its overload capacity. Constraints (8) (9) state that the rescue capabilities of hospitals and emergency medical facilities should be consistent with the type and degree of injury of the wounded. Constraints (10) require that the sum of the wounded transported to the temporary rescue station should be greater than or equal to the sum of the number transported to the hospital and emergency facilities. Constraints (11) ensure that if there are wounded at the candidate point, a temporary rescue station must be established. Constraints (12) state that if there are wounded at the candidate point, an emergency medical facility must be established. Constraints (13)(14) guarantee that there is a change in the transportation of wounded, and there must be someone to rescue. Constraints (15)-(19) define decision variables.

5. Solution Approaches

The model proposed in this paper is a mixed integer programming model containing three groups of binary variables. The model has been verified by a solver (CPLEX) in a small-scale instance. In the large-scale instance, CPLEX cannot find the feasible solution in reasonable time, which makes it lose the practical application value. Therefore, two heuristic algorithms, particle swarm optimization (PSO) and variable neighborhood search (VNS), were designed respectively to solve the problem according to the characteristics of the model. We reduce the solution time while ensuring the solution quality.

5.1. PSO Based Solution Method

Since its proposal, PSO has been widely studied in the field of operations research (L. Zhen et al., 2016).PSO is a population intelligent search algorithm that simulates the process of bird foraging. Each particle will share information with other particles, making all particles in the population move towards the optimal solution. In each iteration, particles update their position and velocity information based on the individual historical optimal solution and the group global optimal solution. The algorithm can be adapted to a variety of scenarios and has a fast convergence rate.The PSO algorithm is widely used in the study of optimization problems, such as the drone delivery problem (Meng et al., 2024), the site selection problem (Yin et al., 2024) and the vehicle path problem (wang et al., 2023).

5.1.1. Solution Representation and Velocity Updating Strategy

Of all the decision variables,

can determined the location of temporary rescue station, while the value of

depends on

. When the candidate temporary rescue station

is established, it is possible for the resource demand of the disaster area to be met by temporary rescue station

. Structurally,

is significantly more important than

. For the rest of decision variable, The changes of its value will directly react in the objective value. Decision variables

,

and

are three groups of integer variables, which respectively represent the optimal transport volume between the disaster area and the temporary rescue station, the optimal transport volume between the disaster area and the emergency medical facility, as well as the optimal transport volume between the disaster area and the hospital. After determining the values of

, the remaining decision variables can be obtained more easily. Thus, the value we set for the particle will contain the location information for

. The particle can be defined as

and

, while the velocity can be defined as

and

. Before start iterating, the initial particles are randomly generated under specified conditions which meets all the constraints. The initial individual optimal value and the global optimal value are the minimum fitness values calculated according to the initial particle. Each particle represents a search direction, and its search trajectory is determined by the current position and velocity of the particle. The position and velocity of the particle are updated as follows (20)-(23):

In the formula for particle velocity update, c1 and c2 are social learning factors which can determine the particle velocity combine with the individual optimal position of the particle and the global optimal position of the particle swarm. r1 and r2 are random generated range from zero to one. w denote inertia weight.

5.1.2. Improved PSO Algorithm

Particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm uses fewer parameters and can get good solution in a short time. However, the basic PSO algorithm is more suitable for searching continuous variables while binary variables exist in this paper. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the particle swarm optimization algorithm according to the characteristics of the problem and adjust the search strategy of the solution to make it more suitable for the model in this paper.

1) We change the discrete variable into continuous variable with a value range from 0 to 1. The corresponding variable in PSO is . The value of equals 1 if the value of is greater than 0.5, while equals 0 if the value of is less than 0.5.

2) At the beginning of the basic PSO algorithm, the search usually reaches the boundary at a very fast speed, and the subsequent search results rely on random oscillations. As a result, the algorithm is easy to fall into the local optimum due to limited improvement in the later iteration. Through the simulation experiment, it is found that the results obtained by setting the inertia weight as the dynamic change according to the number of iterations are much better than those obtained by fixed inertia weight. Therefore, we associate

with the number of iterations and adjust the value according to the number of iterations. PSO has a strong global optimization ability when the value of inertia weight

is large, while PSO has a strong local optimization ability when the value of

is small. The formula is defined as follows (24).

In the equation, represents the current number of iterations, and represents the maximum inertia weight and the minimum inertia weight respectively.

5.1.3. General Procedure of PSO

According to the discussion about the algorithm principle, velocity update formula and the definition of parameters, the steps of PSO are as follows:

Step 1: Customize a class of particle whose data member contains variables used to store position, variables used to store velocity and variables used to store fitness value;

Step 2: Initialize a population of 50 particles. Here numParticle = 50, every particle is a custom class;

Step 3: Parameter conversion and evaluate the fitness of each particle, which is solved by commercial software CPLEX. We first fix the variable according to the position of particle. Then the original model can be solved by CPLEX in a very short time;

Step 4: Calculate the initial weight w, and assign the fitness to particle_pbest and particle_gbest;

Step 5: While (pso_index<max iterations) do.

Step 5.1: Update the new position and the new velocity of each particle by using (26)-(29) and make sure the boundary is not exceeded;

Step 5.2: Evaluate the fitness value of each particle

Step 5.3: Compare the fitness value with the personal optimal value of the particle. If it is better than the historical personal optimal value, update the personal optimal value and record the position information of the particle;

Step 5.4: Compare the personal optimal value of each particle with the global optimal value. If it is better than the historical global optimal value, update the global value and record the position information.

Step 6: Output the result of the best efficient solution.

|

Algorithm 1: Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

|

| Require: |

n, numParticle, max_gen,c1,c2,r1,r2 //n is the number of iteration; numParticle is the number of particles; max_gen is the maximum number of iterations; c1 and c2 are the acceleration weights; r1 and r2 are learning factors; |

| Result: |

The objective value |

| 1: |

Define particle_gbest, particle_pbest[numParticle], particle_temp[numParticle],

// each particle is a class which contains 5 data members, the position(alp, zet) and the velocity of particle(v_alp, v_zet) and the fitness; particle_gbest is used to store the best position of the whole swarm; particle_pbest is used to store the best position of a single particle; particle_temp is used to store current position of a single particle

|

| 2: |

Initialize the swarm |

| 3: |

For all nnumParticle

|

| 4: |

Evaluate fitness of particle_temp[n] by solving model

|

| 5: |

particle_pbest ← particle_temp[n]

|

| 6: |

If particle_pbest[n].fitness < particle_gbest[n].fitness

|

| 7: |

particle_gbest ← particle_pbest[n]

|

| 8: |

End if

|

| 9: |

End for |

| 10: |

pso_index←1 |

| 11: |

While(pso_index<max_gen) |

| 12: |

For all nnumParticle

|

| 13: |

particle_temp[n].v_alp←wn*particle_temp[n].v_alp+c1*r1*(particle_pbest[n].alp-particle_temp[n].alp)+c2*r2*(particle_gbest.alp–particle_temp[n].alp)

|

| 14: |

particle_temp[n].v_zet←wn*particle_temp[n].v_zet+c1*r1*(particle_pbest[n].zet-particle_temp[n].zet)+c2*r2*(particle_gbest.zet–particle_temp[n].zet)

|

| 15: |

If particle_temp[n].alp < alpmin

|

| 16: |

particle_temp[n].alp = alpmin

|

| 17: |

Else if particle_temp[n].alp > alpmax

|

| 18: |

particle_temp[n].alp = alpmax

|

| 19: |

End if

|

| 20: |

If particle_temp[n].zet < zetmin

|

| 21: |

particle_temp[n].zet = zetmin

|

| 22: |

Else if particle_temp[n].zet > zetmax

|

| 23: |

particle_temp[n].zet = zetmax

|

| 24: |

End if

|

| 25: |

Evaluate fitness of particle_temp[n] by solving model

|

| 26: |

If particle_temp[n].fitness < particle_pbest[n].fitness

|

| 27: |

particle_pbest[n] ← particle_temp

|

| 28: |

End if

|

| 29: |

If particle_temp[n].fitness < particle_gbest.fitness

|

| 30: |

particle_gbest ← particle_temp

|

| 31: |

End if

|

| 32: |

End for

|

| 33: |

pso_index++

|

| 34: |

End while |

| 35: |

Return the objective value |

5.2. VNS Based Solution Method

Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) is an improved local search algorithm. It achieves the balance of centrality and sparsity by alternately searching different neighborhood structures. During the search process, the algorithm does not follow a fixed pattern, which can effectively jump out of the local optimum and greatly improve the quality of the solution. The main process of the algorithm is to generate the initial solution and find the optimal solution through neighborhood transformation. If a better solution cannot be found in a neighborhood, then the search jumps out of the current neighborhood and into the next neighborhood. If a better solution is found in a neighborhood, the search returns to the first neighborhood structure. The algorithm will continue this iterative process until the quality of the solution can no longer be improved. As a heuristic algorithm, VNS is widely used to solve mixed-integer programming models such as classical combinatorial optimization problems (Lamb, 2012), routing issue(Wei et al., 2020), and vehicle path problems (Sadati and Catay, 2021).

5.2.1. Solution Representation

According to the analysis in

Section 5.1.1,

is the main decision variables in the model proposed in this paper. Therefore, we use VNS to conduct a neighborhood search for these two decision variables. When a new neighborhood solution is generated, the business solver CPLEX is called to solve the model and determine whether the value of the objective function has improved. If a better solution is found, the algorithm will jump out of the current neighborhood and go back to the first neighborhood to start the search again. When the optimal solution cannot be found within an iteration, shaking the optimal solution and move into next iteration.

According to the basic framework, the key issue to solve the model include: i) initialization: how to give a good feasible solution including the alternative points, size of the size and the proportion of direct shipments from suppliers to disaster area by air; ii) neighborhood structure: how to set suitable neighborhood structure which can find optimal solution in a very short time; iii) shaking procedure: how to avoid falling into local optimization. iv) variable neighborhood descent: the framework of the neighborhood search.

5.2.2. Initial Solution

First, we calculated the total demand for all kinds of resources at all disaster areas. According to the total demand, we selected the smallest size among all temporary rescue stations that could meet the demand, and the location of the temporary rescue station was randomly selected from the alternative temporary rescue stations. This makes it possible to determine the value of . For , we want it to be as small as possible due to the high cost of air transportation, so its initial value is randomly selected as a decimal less than 0.5. In the neighborhood search, the neighborhood structure related to temporary rescue station location will be executed first. Then the neighborhood structure of will be conducted to ensure that the potential optimal solution will not be missed during the search for solutions.

5.2.3. Neighborhood Structures

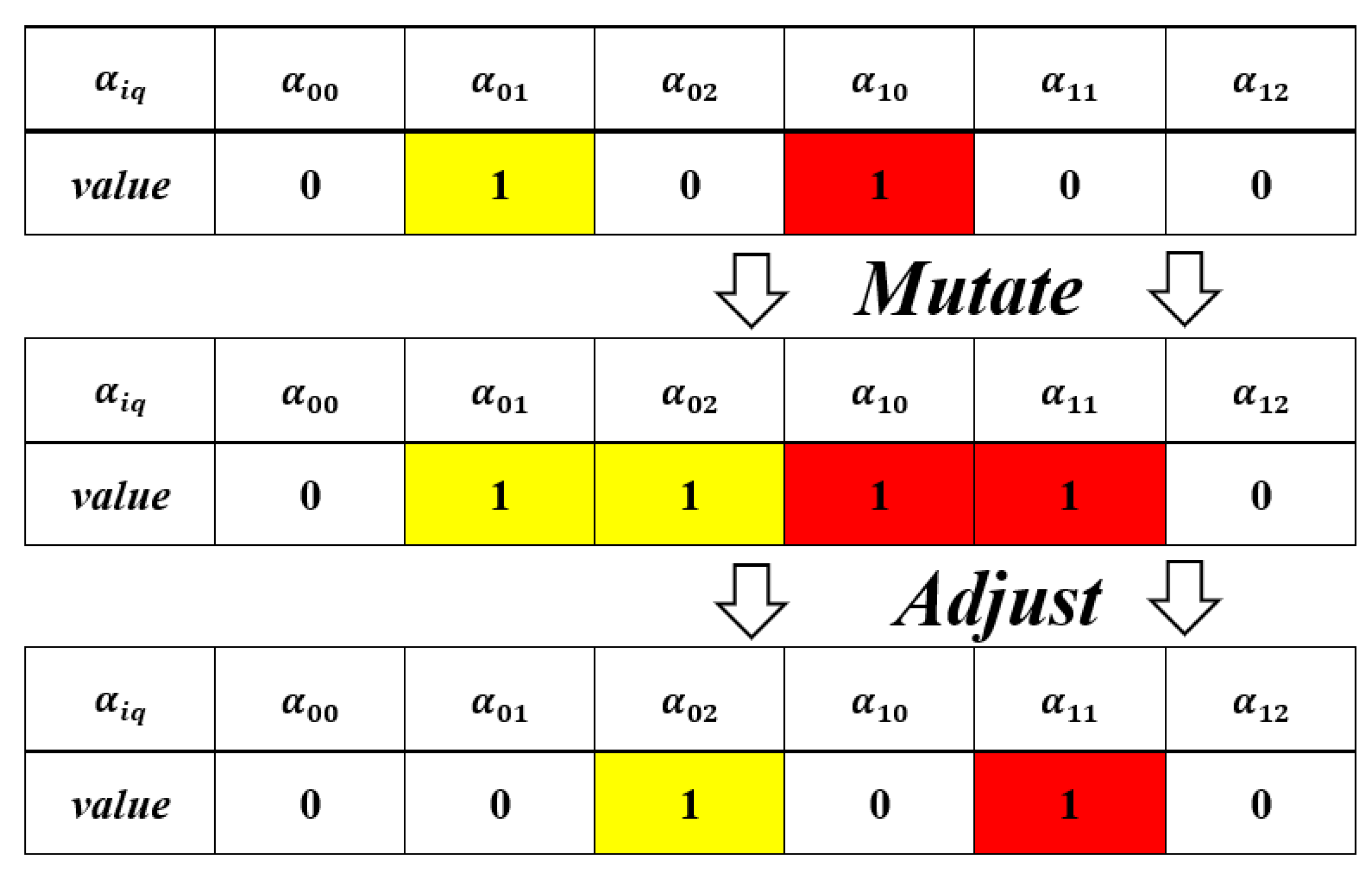

The mixed integer programming model proposed in this paper contains both binary variables and float variables. We had to design specific neighborhood structure to help VNS search the float variables. For the neighborhood structure of decision variable , we can encode it according to its dimension. The temporary rescue station is established only when equals 1. The neighborhood can be generated through mutation and exchange, but then it is necessary to determine whether the location of the temporary rescue station meets constraint (2). Although there may be some error, it is within the acceptable range.

1) Neighborhood structure 1: mutation

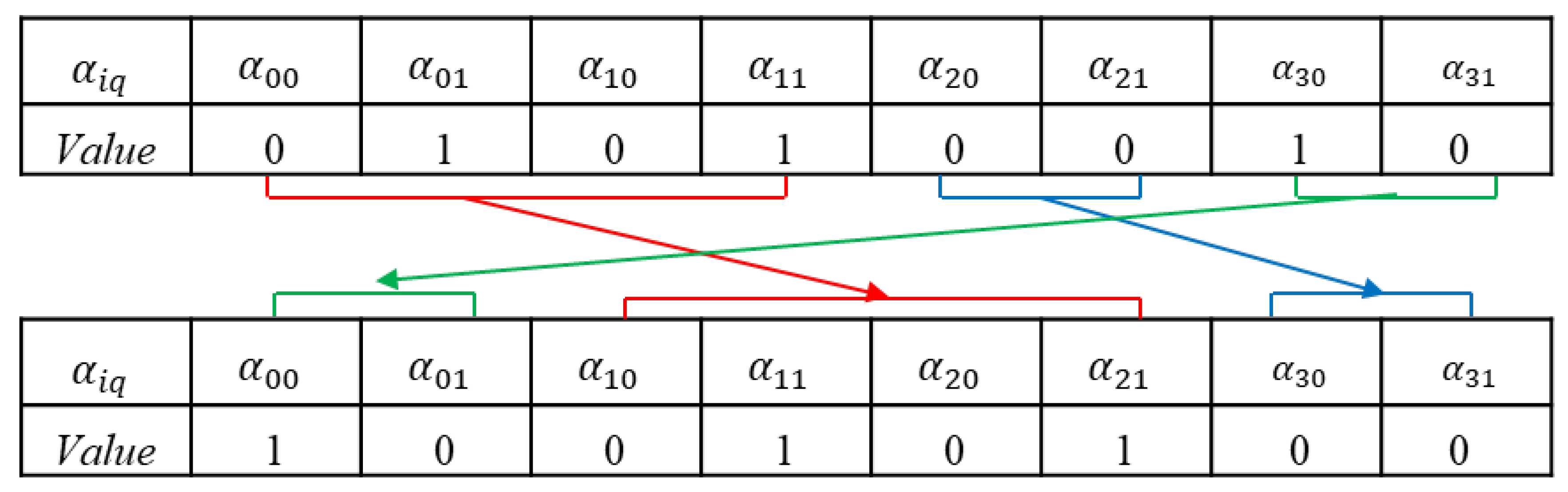

Select a randomly and change its value, it will change to 1 if its original value is 0, and to 0 if it is 1. The feasibility is than judgement. If a certain size of the temporary rescue station is selected, but another temporary rescue station is already established at the same point. In this case, the corresponding code of current temporary rescue stations should be set to 0, and the corresponding code of the newly generated temporary rescue station should be set to 1. In other words, we must ensure that each alternative point can only build one temporary rescue station. The process is shown in Figure 3. Neighborhood structure: mutation. After each mutation, the neighborhood solution needs to be adjusted according to the constraint.

Figure 3.

Neighborhood structure: mutation.

Figure 3.

Neighborhood structure: mutation.

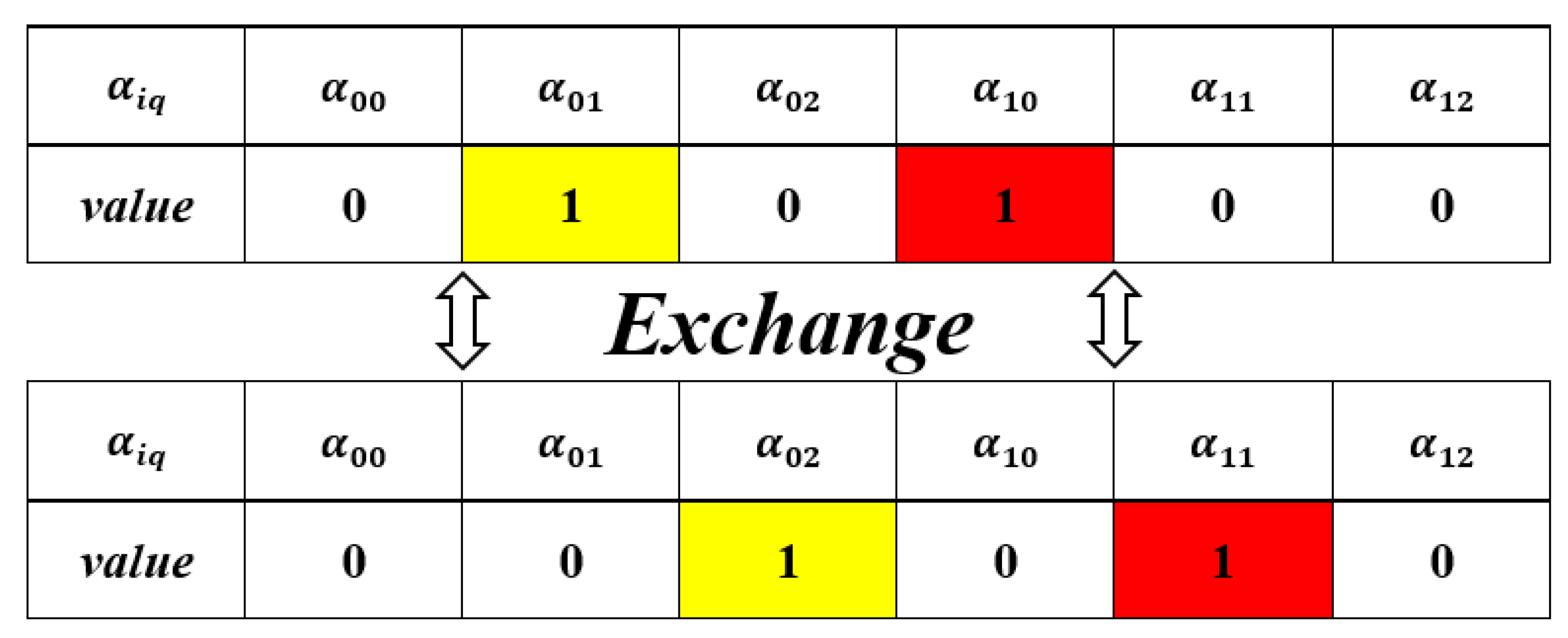

2) Neighborhood structure 2: exchange

The process of exchange is shown in Figure 4. Neighborhood structure: exchange.. First, two are randomly selected, which can be chosen from the same temporary rescue station of two different sizes or from two different temporary rescue stations of any size. After exchanging the value of two points, we must judge whether it is feasible. If two different sizes of the same temporary rescue station are both selected, the value of original needs to be set to 0.

Figure 4.

Neighborhood structure: exchange.

Figure 4.

Neighborhood structure: exchange.

The variable neighborhood descent is a framework of the algorithm, which searches in the neighborhood structures. The algorithm will completely explore one neighborhood structure and then go to the next neighborhood structure when no better solution can be found. The flow of the VND is shown in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2: Variable Neighborhood Descent (VND)

|

| Require: |

best_solution, temp_solution, l←1, //best_solution is the optimal solution and temp_solution is the current solution, l is used to record the neighborhood structure |

| 1: |

temp_solution←best_solution |

| 2: |

While(true) |

| 3: |

switch(l)

|

| 4: |

case 1:

|

| |

neighborhood_one(temp_solution)

|

| 5: |

If(temp_solution.fitness<best_solution.fitness)

|

| 6: |

best_solution←temp_solution;

|

| 7: |

l = 0;

|

| 8: |

End if

|

| 9: |

break;

|

| 10: |

case 2:

|

| 11: |

neighborhood_two(temp_solution)

|

| 12: |

If(temp_solution.fitness<best_solution.fitness)

|

| 13: |

best_solution←temp_solution;

|

| 14: |

l = 0;

|

| 15: |

End if

|

| 16: |

break;

|

| 17: |

case 3:

|

| 18: |

neighborhood_three(temp_solution)

|

| 19: |

If(temp_solution.fitness<best_solution.fitness)

|

| 20: |

best_solution←temp_solution;

|

| 21: |

l = 0;

|

| 22: |

End if

|

| 23: |

break;

|

| 24: |

case 4:

|

| 25: |

neighborhood_four(temp_solution)

|

| 26: |

If(temp_solution.fitness<best_solution.fitness)

|

| 27: |

best_solution←temp_solution;

|

| 28: |

l = 0;

|

| 29: |

End if

|

| 30: |

break;

|

| 31: |

default;

|

| 32: |

return;

|

| 33: |

l++;

|

| 34: |

End while |

5.2.5. Shaking Procedure

After each iteration of VNS, a shaking procedure need to be performed before moving into a new iteration. The aim is to avoid the algorithm falling into the local optimal situation and search the global optimal solution as much as possible. The easiest way to do this is to randomly generate a set of initial solutions and continue through an iteration. However, this method is not the optimal choice, and the randomly generated solutions may not meet the constraints, and additional neighborhood searches are needed to get the better solution.

More precisely, the way we deal with it is to block the optimal solution obtained in the previous round according to the candidate temporary rescue station. A set of solutions that meet the constraints but are completely different from the current optimal solution are then obtained by exchanging them by blocks. The specific exchange process can be seen in Figure 5. Shaking procedure.. The new solution must be a feasible solution that meets the constraints since the size of the temporary rescue station is the same, but the value of the objective function will be different. Searching for a feasible solution can quickly finish, which is obviously better than the randomly generated initial solution.

Figure 5.

Shaking procedure.

Figure 5.

Shaking procedure.

5.2.6. Variable Neighborhood Search

Based on the description about initial solution, neighborhood structure and shaking procedure, we further give the algorithm flow of VNS:

Step 1: Generate initial solution according to the rule, and assign the initial solution to the best_solution;

Step 2: While(iteration<max_gen)

Step 2.1: Assigns the best_solution to the current_solution;

Step 2.2: Generate new feasible solution by shaking procedure;

Step 2.3: Traverse the neighborhood structure to search for solutions under the framework of VND. Each time an improved solution is found, the search continues with the first operator. Assign the optimal solution to current_solution;

Step 2.4: Update the best_solution if the current_solution is better than the best_solution, set the number of iteration to 0;

Step 2.5: iteration++;

Step 3: Output best_solution.

|

Algorithm 3: Variable Neighborhood Search(VNS)

|

| Require: |

max_gen, current_solution, best_solution, iteration=0, max_gen=10

//max_gen is the maximum number of iterations, best_solution is the optimal solution and current_solution is current solution

|

| Result: |

Objective value |

| 1: |

best_solution←Initial solution |

| 2: |

While (iteration<max_gen) |

| 3: |

current_solution←best_solution

|

| 4: |

shaking(current_solution)

|

| 5: |

Variable neighborhood descent(current_solution)

|

| 6: |

If(current_solution.fitness < best_solution.fitness)

|

| 7: |

best_solution←current_solution

|

| 8: |

iteration = 0;

|

| 9: |

End if

|

| 10: |

Iteration++;

|

| 11: |

End while |

6. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we evaluate the solution quality and execution efficiency of the two heuristic algorithms through numerical experiments and compare the performance of the commercial software CPLEX with our algorithms under different sizes of arithmetic cases. All experiments are performed on a Windows 10 computer with 16GB of RAM and an i3-12100F processor. This study also compiles all codes using C# (VS2022) and solves the mixed integer programming model using CPLEX (version 12.7).

6.1. Generation of Test Instances

Numerical examples of small, medium and large scale are designed to validate the performance of proposed algorithms. And each scale contains several groups of examples which can avoid accidental results. All the data is generated based on practical situation. We assume that the population in a disaster area ranges from 150,000 to 500,000, which is a normal population size of a county in China. For the rest data, determine the means of transportation and corresponding medical facilities through the type of wounded.

6.2. Performance of Two Heuristics

The results of small-scale and medium-scale examples are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Where represents the value of the objective function and represents the calculation time. The in the table is used to represent the degree of error between the solution obtained by the algorithm and the exact solution obtained by CPLEX, and its calculation formula is 。The subscript , , represent CPLEX, PSO and VNS respectively. Based on the results of test, we set the number of particles is 50 and two learning factors c1 and c2 as , for PSO. Both algorithms will not stop iterating until the max iteration is reached or no more optimal solution can be searched.

Table 2.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in small-scale problems.

Table 2.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in small-scale problems.

| Cases ID |

CPLEX |

PSO |

Comparison |

VNS |

Comparison |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A4-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-1 |

584915 |

7.5 |

584915 |

16.2 |

2.16 |

0.00% |

584915 |

18.7 |

2.49 |

0.00% |

| A4-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-2 |

604314 |

7.8 |

604314 |

17.5 |

2.24 |

0.00% |

604314 |

20.8 |

2.67 |

0.00% |

| A4-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-3 |

622280 |

8.2 |

622280 |

19.2 |

2.34 |

0.00% |

622280 |

22.6 |

2.76 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

603836 |

7.8 |

603836 |

17.6 |

2.25 |

0.00% |

603836 |

20.7 |

2.64 |

0.00% |

| A4-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-1 |

587795 |

13.1 |

587795 |

27.9 |

2.13 |

0.00% |

587795 |

24.8 |

1.89 |

0.00% |

| A4-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-2 |

555550 |

14.5 |

555550 |

29.4 |

2.03 |

0.00% |

555550 |

22.8 |

1.57 |

0.00% |

| A4-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-3 |

568258 |

12.9 |

568258 |

25.9 |

2.01 |

0.00% |

568258 |

23.2 |

1.80 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

570534 |

13.5 |

570534 |

27.7 |

2.06 |

0.00% |

570534 |

23.6 |

1.75 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-1 |

734355 |

12.5 |

734355 |

17.2 |

1.38 |

0.00% |

734355 |

15.1 |

1.21 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-2 |

714710 |

13.5 |

714710 |

18.5 |

1.37 |

0.00% |

714710 |

18.8 |

1.39 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-3 |

693315 |

14.1 |

693315 |

17.6 |

1.25 |

0.00% |

693315 |

16.2 |

1.15 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

714127 |

13.4 |

714127 |

17.8 |

1.33 |

0.00% |

714127 |

16.7 |

1.25 |

0.00% |

| A4-3-6-6-4-2-2-5-1 |

744445 |

28.8 |

744445 |

29.8 |

1.03 |

0.00% |

744445 |

26.2 |

0.91 |

0.00% |

| A4-3-6-6-4-2-2-5-2 |

708820 |

32.5 |

708820 |

30.5 |

0.94 |

0.00% |

708820 |

23.6 |

0.73 |

0.00% |

| A4-3-6-6-4-2-2-5-3 |

726788 |

31.5 |

726788 |

30.6 |

0.97 |

0.00% |

726788 |

22.8 |

0.72 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

726684 |

30.9 |

726684 |

30.3 |

0.98 |

0.00% |

726684 |

24.2 |

0.79 |

0.00% |

| A6-3-6-6-4-2-2-10-1 |

842566 |

29.1 |

842566 |

25.8 |

0.89 |

0.00% |

842566 |

27.4 |

0.94 |

0.00% |

| A6-3-6-6-4-2-2-10-2 |

802506 |

29.8 |

802506 |

28.6 |

0.96 |

0.00% |

802506 |

25.6 |

0.86 |

0.00% |

| A6-3-6-6-4-2-2-10-3 |

800090 |

30.7 |

800090 |

27.8 |

0.91 |

0.00% |

800090 |

26.0 |

0.85 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

815054 |

29.9 |

815054 |

27.4 |

0.92 |

0.00% |

815054 |

26.3 |

0.88 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-1 |

788898 |

45.4 |

788898 |

32.6 |

0.72 |

0.00% |

788898 |

34.5 |

0.76 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-2 |

737790 |

49.6 |

737790 |

34.5 |

0.70 |

0.00% |

737790 |

30.8 |

0.62 |

0.00% |

| A6-2-6-6-4-2-2-10-3 |

739632 |

48.5 |

739632 |

33.6 |

0.69 |

0.00% |

739632 |

35.6 |

0.73 |

0.00% |

| Avg. |

755440 |

47.8 |

755440 |

33.6 |

0.70 |

0.00% |

755440 |

33.6 |

0.70 |

0.00% |

In Table 2, we tested 6 groups of 18 small-scale examples and compared the solution and calculating time of three different methods. The case ID A4-2-4-4-4-2-2-5-1 means 4 alternative temporary rescue stations, 2 alternative emergency medical facilities, 4 hospitals, 4 disaster affected areas, 4 types of the wounded, 2 sizes of temporary rescue station, 2 sizes of medical facility and 5 scenarios of instance 1. The first method is use CPLEX to solve the model directly. Other two method is using PSO and VNS to search the optimal solution. As the results shown in Table 2, both heuristic algorithms can obtain the same solution. The average optimality gap is 0.0% for all 18 cases. In terms of time, CPLEX spends very short time when calculating small-scale examples. The solution time of CPLEX is less than 10 seconds when sets of examples have only 5 scenarios while the time of PSO and VNS is more than 10 seconds. But with the growing of instance scale, both algorithms perform better than CPLEX. In the cases of 6 alternative temporary rescue stations, 2 alternative emergency medical facilities, 6 hospitals and more than 10 scenarios, both PSO and VNS could complete the calculation in about 35 seconds, and VNS was slightly faster. But CPLEX takes twice as long to solve as the algorithm.

Table 3.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in medium-scale problems.

Table 3.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in medium-scale problems.

| Cases ID |

CPLEX |

PSO |

Comparison |

VNS |

Comparison |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A8-2-8-10-4-2-2-20-1 |

1077630 |

458.5 |

1079634 |

105.4 |

0.23 |

0.19% |

1081634 |

96 |

0.21 |

0.37% |

| A8-2-8-10-4-2-2-20-2 |

1045665 |

498.6 |

1055665 |

118.2 |

0.24 |

0.96% |

1047665 |

82.5 |

0.17 |

0.19% |

| A8-2-8-10-4-2-2-20-3 |

1004454 |

525.2 |

1012754 |

119.4 |

0.23 |

0.83% |

1005454 |

92.6 |

0.18 |

0.10% |

| Avg. |

1042583 |

494.1 |

1049351 |

114.3 |

0.23 |

0.66% |

1044918 |

90.4 |

0.18 |

0.22% |

| A8-4-8-15-4-2-2-20-1 |

1111434 |

926.5 |

1116434 |

136.5 |

0.15 |

0.45% |

1114634 |

108.2 |

0.12 |

0.29% |

| A8-4-8-15-4-2-2-20-2 |

1228565 |

896.9 |

1230565 |

158.6 |

0.18 |

0.16% |

1229995 |

112.5 |

0.13 |

0.12% |

| A8-4-8-15-4-2-2-20-3 |

1240855 |

883.8 |

1244455 |

165.8 |

0.19 |

0.29% |

1241155 |

115.9 |

0.13 |

0.02% |

| Avg. |

1193618 |

902.4 |

1197151 |

153.6 |

0.17 |

0.30% |

1195261 |

112.2 |

0.12 |

0.14% |

| A8-4-8-20-4-2-2-20-1 |

1409562 |

2620.2 |

1410885 |

345.3 |

0.13 |

0.09% |

1415620 |

172.4 |

0.07 |

0.43% |

| A8-4-8-20-4-2-2-20-2 |

1312520 |

2831.5 |

1317520 |

410.2 |

0.14 |

0.38% |

1319520 |

171.8 |

0.06 |

0.53% |

| A8-4-8-20-4-2-2-20-3 |

1325668 |

2450.6 |

1329256 |

478.8 |

0.20 |

0.27% |

1335668 |

160.2 |

0.07 |

0.75% |

| Avg. |

1349250 |

2634.1 |

1352553 |

411.4 |

0.16 |

0.25% |

1356936 |

168.1 |

0.06 |

0.57% |

Table 3 presents the results of medium-scale instances, we chose 10 scenarios in the three sets of examples and increase other parameters. It is not difficult to find that the solution time of two heuristic algorithms is significantly better than CPLEX at medium scale. Using CPLEX to find optimal solution of medium-scale problem is time consuming. In the first set of examples, the solution time of CPLEX was about 5 times that of PSO and 8 times that of VNS. In the remaining two sets of examples, the gap is further magnified due to the exponentially growth of CPLEX. In terms of solution quality, the algorithm can obtain the optimal solution consistent with CPLEX in most examples. Only a few examples fail to find the optimal solution, but the average gap is less than 1%. This conclusion proves that two heuristic algorithms we developed can effectively improve the solving efficiency of complex models and ensure the solution quality. In the comparison of the two algorithms, VNS is superior to PSO both in solution quality and solving time. This is also consistent with the results of other studies. The overall performance of VNS is better than PSO in the mixed integer programming model, especially when the model’s primary variable is binary. VNS show good behavior and needs less time on the location-allocation problem in supply chain.

Table 4.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in large-scale problems.

Table 4.

Comparison of two heuristics and CPLEX in large-scale problems.

| Cases ID |

CPLEX |

PSO |

VNS |

Comparison |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-30-1 |

- |

>7200 |

1552354 |

716.9 |

1495226 |

256.8 |

0.36 |

3.82% |

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-30-2 |

- |

>7200 |

1511435 |

537 |

1495035 |

288.7 |

0.35 |

1.10% |

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-30-3 |

- |

>7200 |

1624352 |

612.1 |

1606490 |

276.2 |

0.34 |

1.11% |

| Avg. |

- |

>7200 |

1562714 |

622 |

1532250 |

273.9 |

0.35 |

1.99% |

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-50-1 |

- |

>7200 |

1499535 |

923.8 |

1472636 |

584.6 |

0.63 |

1.83% |

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-50-2 |

- |

>7200 |

1446548 |

834.2 |

1392300 |

430.1 |

0.52 |

3.90% |

| A10-5-8-20-4-2-2-50-3 |

- |

>7200 |

1529066 |

1267 |

1499024 |

577.6 |

0.46 |

2.00% |

| Avg. |

- |

>7200 |

1491716 |

1008.3 |

1454653 |

530.8 |

0.54 |

2.55% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-30-1 |

- |

>7200 |

1773460 |

791.4 |

1693460 |

325.8 |

0.29 |

4.72% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-30-2 |

- |

>7200 |

1777342 |

494.1 |

1694352 |

297.3 |

0.48 |

4.90% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-30-3 |

- |

>7200 |

1806532 |

882.5 |

1778904 |

312.3 |

0.29 |

1.55% |

| Avg. |

- |

>7200 |

1785778 |

722.7 |

1722239 |

311.8 |

0.35 |

3.69% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-50-1 |

- |

>7200 |

1928654 |

2055.5 |

1908654 |

671.2 |

0.33 |

1.05% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-50-2 |

- |

>7200 |

1900541 |

1521.2 |

1883541 |

623.7 |

0.41 |

0.90% |

| A10-5-8-25-4-2-2-50-3 |

- |

>7200 |

1994455 |

2140.1 |

1908026 |

673.0 |

0.31 |

4.53% |

| Avg. |

- |

>7200 |

1941217 |

1905.6 |

1900074 |

656.0 |

0.35 |

2.17% |

6.3. Large-Scale Experiments

In order to further test the effectiveness of our proposed algorithms, we increase value of scenarios. Most of the variables in Table 4. have the same meaning as in Table 2 Only , which is the difference between the solutions of VNS and PSO, is calculated by equation (. It is obviously that the average calculating time increases as the scale of example increases. According to collected data in Table 4, CPLEX cannot find a feasible solution in 7200 seconds which makes it impossible to use in practice. Comparing the two algorithms, VNS can always find the same or better solution as PSO. The computation time of VNS increases linearly as the instance size growths, which is much better than CPLEX and PSO.

7. Conclusions

This paper explores the feasibility of introducing a hybrid rescue model by studying the optimal allocation of emergency medical resources in multi-hazard coupling under uncertainty, aiming to enhance the government’s ability to respond to sudden-onset natural disasters. In disaster rescue, rational medical facility siting and resource allocation is the key to improving rescue efficiency, which can ensure that the injured receive effective treatment in the first time and minimize the casualties caused by resource shortage. On the contrary, irrational planning not only increases the burden on the government, but also may lead to delays in rescue operations, thus exacerbating the consequences of disasters. Therefore, optimizing the allocation of emergency medical resources, especially in the uncertain scenario of multi-hazard coupling, has become a core topic to enhance the efficiency of emergency rescue. In this study, a multi-hazard coupling scenario is constructed using simulation methods, and based on this, we investigate how to effectively coordinate and allocate emergency medical resources and facilities through a hybrid rescue model under uncertainty. Through this framework, the study examines the impact of different disaster situations and resource demand changes on emergency response in the event of a disaster, thus providing theoretical support and practical guidance for rational resource allocation and rescue model optimization.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) In the model design, we assume that temporary relief stations, emergency medical facilities and hospitals can meet the resource demands of different casualties in the disaster area. The diversity of types of injured people and the upper and lower limits of the establishment of each type of facilities make the problem more close to reality and can truly reflect the constraints in resource allocation. Scarcity of resources will give rise to severe penalties, and this paper comprehensively considers this factor and proposes a more comprehensive and realistic research framework.

(2) This paper introduces an uncertain scenario to simulate the emergency response under different levels of disasters, taking into account the dynamic changes in the proportion of people affected by disasters, the capacity of hospitals, and the demand for resources in the disaster area. By analyzing the optimal solutions under different scenarios, the results demonstrate the robustness of the proposed model, which is able to provide effective emergency response strategies in most disaster scenarios.

(3) Although the proposed model is able to simulate complex disaster scenarios in a more comprehensive way, the complexity of the model itself makes it difficult to perform accurate computation for large-scale instances by traditional solvers (e.g., CPLEX). Therefore, we propose two heuristic algorithms with a view to improving the computational efficiency.

(4) Based on the numerical analysis results, we summarize the rules for siting temporary rescue stations and emergency medical facilities, and point out the performance of the algorithms for different scale instances. It is shown that the proposed two algorithms are able to obtain the same solution as CPLEX in small-scale instances, although the computation time is slightly longer; in medium-scale instances, the two algorithms are able to find the optimal solution in most cases and the computation time is shorter. Even in the case of failing to find the global optimal solution, the solution error is less than 0.5%. For large-scale instances, the proposed algorithm shows a clear advantage and is able to find a feasible solution in a shorter time, whereas CPLEX is unable to obtain a feasible solution in 7200 seconds.

In the comparison of the two algorithms, the VNS algorithm outperforms the PSO algorithm in most cases, especially when dealing with larger scale instances. This result demonstrates the potential of the proposed algorithm in optimizing the allocation of emergency medical resources. Nevertheless, there are still some limitations of the research in this paper. First, the data in the examples are randomly generated according to a uniform distribution, which may differ from the actual disaster distribution. Second, only two heuristic algorithms were tested in this paper, and although better results were achieved, the acquisition of the global optimal solution is still not fully guaranteed. In future research, attempts can be made to design more accurate algorithms to further optimize the quality of the solution. In addition, this paper did not consider the relationship between the mode of casualty transportation and the type of casualty, and future research can further expand on this basis by considering the time cost and resource allocation problems in the transportation process. In conclusion, this study provides an effective theoretical framework and algorithmic support for the optimal allocation of emergency medical resources, which helps to improve the government’s rescue efficiency in responding to natural disasters, especially in the emergency response under multi-hazard coupling and uncertainty scenarios, which is of significant application value and theoretical significance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author Contributions

Bochen Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Supervision. Changping He: Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Yuhan Guo: Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Project of China (Grant numbers 22YJC630128).

References

- Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, S.; Zaindin, M. Sustainable production and waste management policies for COVID-19 medical equipment under uncertainty: a case study analysis. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonmee, C.; Arimura, M.; Asada, T.. Facility location optimization model for emergency humanitarian logistics. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2017, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, S.; ¨Ozaltın, O.Y. Optimal influenza vaccine distribution with equity. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283(2), 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaki, M.; Abareshi, A.; Far, S.M.; Lee, P.T.W. Multi-period vaccine allocation model in a pandemic: a case study of COVID-19 in Australia. Trans. Res. Part e:Logistics and Trans. Review 2022, 161, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Khalili-Damghani, K.; Hafezolkotob, A.; Raissi, S.. Uncertain multi-objective multi-commodity multi-period multi-vehicle location-allocation model for earthquake evacuation planning. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2019, 350, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Nasr, A.K.; Mostafazadeh, P.; Mina, H. Medical waste management during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: a mathematical programming model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Abbasi, A.; Chakrabortty, R.K. Designing an efficient vaccine supply chain network using a two-phase optimization approach: a case study of COVID-19 vaccine. Int. J. Systems Science: Operations and Logistics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helo, P.; Hao, Y. ArtificialIntelligenceinOper-ations Management and Supply Chain Management: AnExploratory Case Study. Production Planning & Control 2022, 33(16), 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, H.; Chaleshtori, A.E.; Khaksar, S.M.S.; Aghaie, A.; Sheu, J.B. COVID-19 vaccine distribution planning using a congested queuing system—a real casefrom Australia. Trans. Res. Part e: Logistics and Trans. Review 2022, 163, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, C.L.; Ahmed, T.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, S.M.; Moktadir, M.A.; Kabir, G. Improving supply chain sustainability in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in anemerging economy: exploring drivers using an integrated model. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 26, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Lu, X.; Yu, X.; Zhu, N. Multi-period integrated planning for vaccination station location and medical professional assignment under uncertainty. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.D. Variable neighbourhood structures for cycle location problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 223, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z. H.. Distributionally robust optimization of an emergency medical service station location and sizing problem with joint chance constraints. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2019, 119(JAN.), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L. Modeling of yard congestion and optimization of yard template in container ports. Transp. Res. Part B 2016, 90, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, D. The multi-visit drone-assisted pickup and delivery problem with time windows. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 314(2), 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moadab, A.; Kordi, G.; Paydar, M.M.; Divsalar, A.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Designing a sustainable-resilient-responsive supply chain network consideringuncertainty in the COVID-19 era. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati-Abarghooee, S.; Sheikhalishahi, M.; Nasiri, M.M.; Gholami-Zanjani, S.M. Designing reverse logistics network for healthcare waste management considering epidemic disruptions under uncertainty. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 142, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remko, van H. Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain – closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. Int.J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40(4), 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadati, M.E.H.; Catay, B. A hybrid variable neighborhood search approach for the multi-depogreen vehicle routing problem. Transport. Res. E-Log 2021, 149(4), 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahparvari, S.; Hassanizadeh, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Kiani, B.; Lau, K.H.; Chhetri, P.; Abbasi, B. A decision support system for prioritised COVID-19 two-dosage vaccination allocation and distribution. Trans. Res. Part e: Logistics and Trans. Review 2022, 159, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippong, D.; Petrovic, S.; Akbari, V. A review of applications of operational research in healthcare coordination in disaster management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Goli, A.; Mardani, A. A novel two-echelon hierarchical location-allocation-routing optimization for green energy-efficient logistics systems. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 324(1–2), 795–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toorajipour, R.; Sohrabpour, V.; Nazarpour, A.; Oghazi, P. Oghazi, andM.; Fischl. ArtificialIntelligenceinSupplyChainMan-agement: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Busi-ness Research 2021, 122, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, S. A review and ranking of operators in adaptive large neighborhood search for vehicle routing problems. European J. Oper. Res. Advance online publication 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Fang, S. C.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Z. A Joint Model of Location, Inventory andThird-Party Logistics Provider in Supply Chain Network Design. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2022, 174, 108809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhen, L.; Qu, X. EMS location-allocation problem under uncertainties. Transport Res E-Log 2023, 168, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Ye, C.Ye,andD.; Peng. Multi-period Dynamic Multi-Objective Emergency Material Distribution Model Under Uncertain Demand. EngineeringApplications of Arti-ficial Intelligence 2023, 117, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qiu, H.; Wang, D.; Duan, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, T. An integrated location-routing problem with post-disaster relief distribution. Computers&Industrial Engineering 2020, 147, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, T.C.E. Two-stage recoverable robust optimization for an integrated locationcallocation and evacuation planning problem. Transp. Res. B 2024, 182, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, ¨O.F.; Yeni, F.B.; Gürsoy Yılmaz, B.; ¨Ozçelik, G. An optimization-based methodology equipped with lean tools to strengthen medical supply chain resilience during a pandemic: a case study from Turkey. Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics and Trans. Review 2023, 173, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Wen, X. On the mass COVID-19 vaccination scheduling problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 141, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Fu, X.; Wang, K. Seaport adaptation to climate change disasters: Subsidy policy vs. adaptation sharing under minimum requirement. Transport Res E-Log 2021, 155(10), 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chen, X.; Dong, K. Joint investment on resilience of cross-country transport infrastructure. Transport. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2022, 166(12), 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |