Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

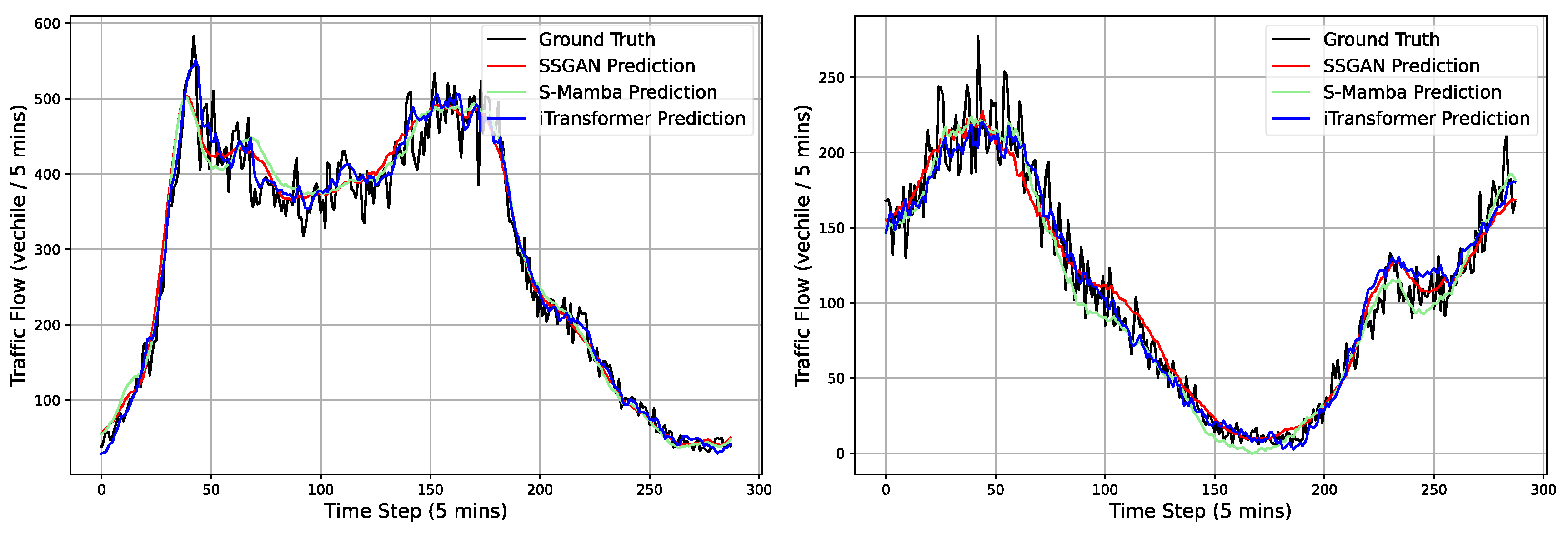

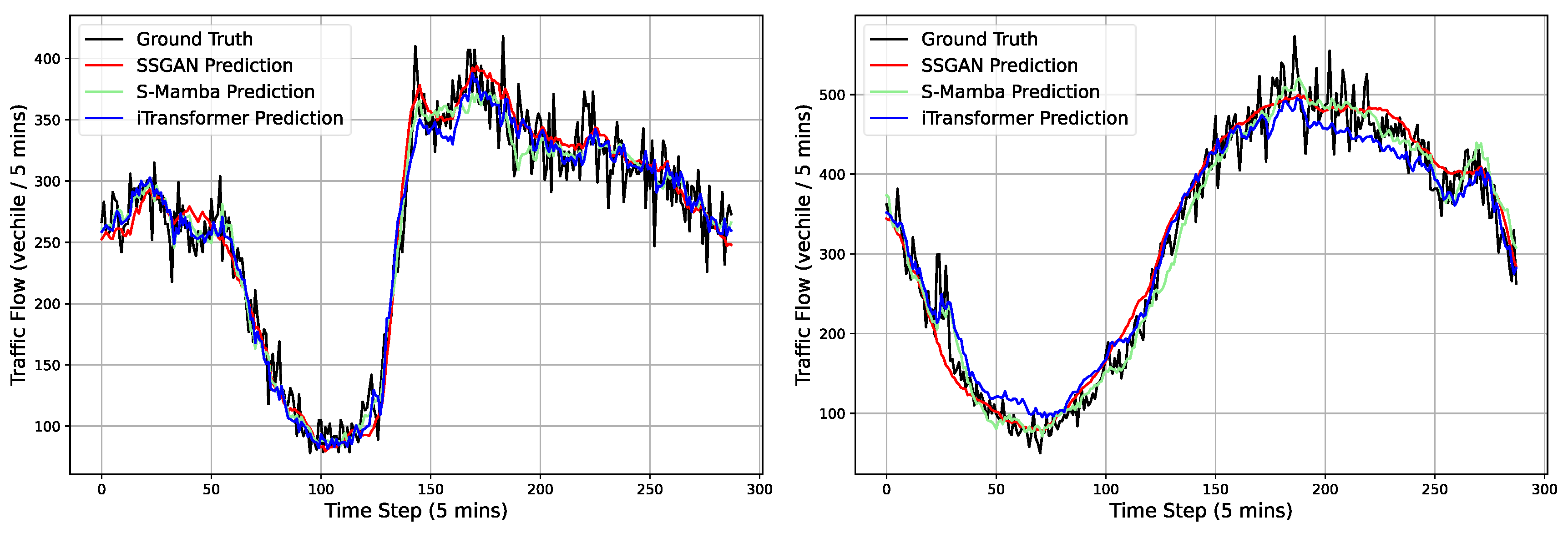

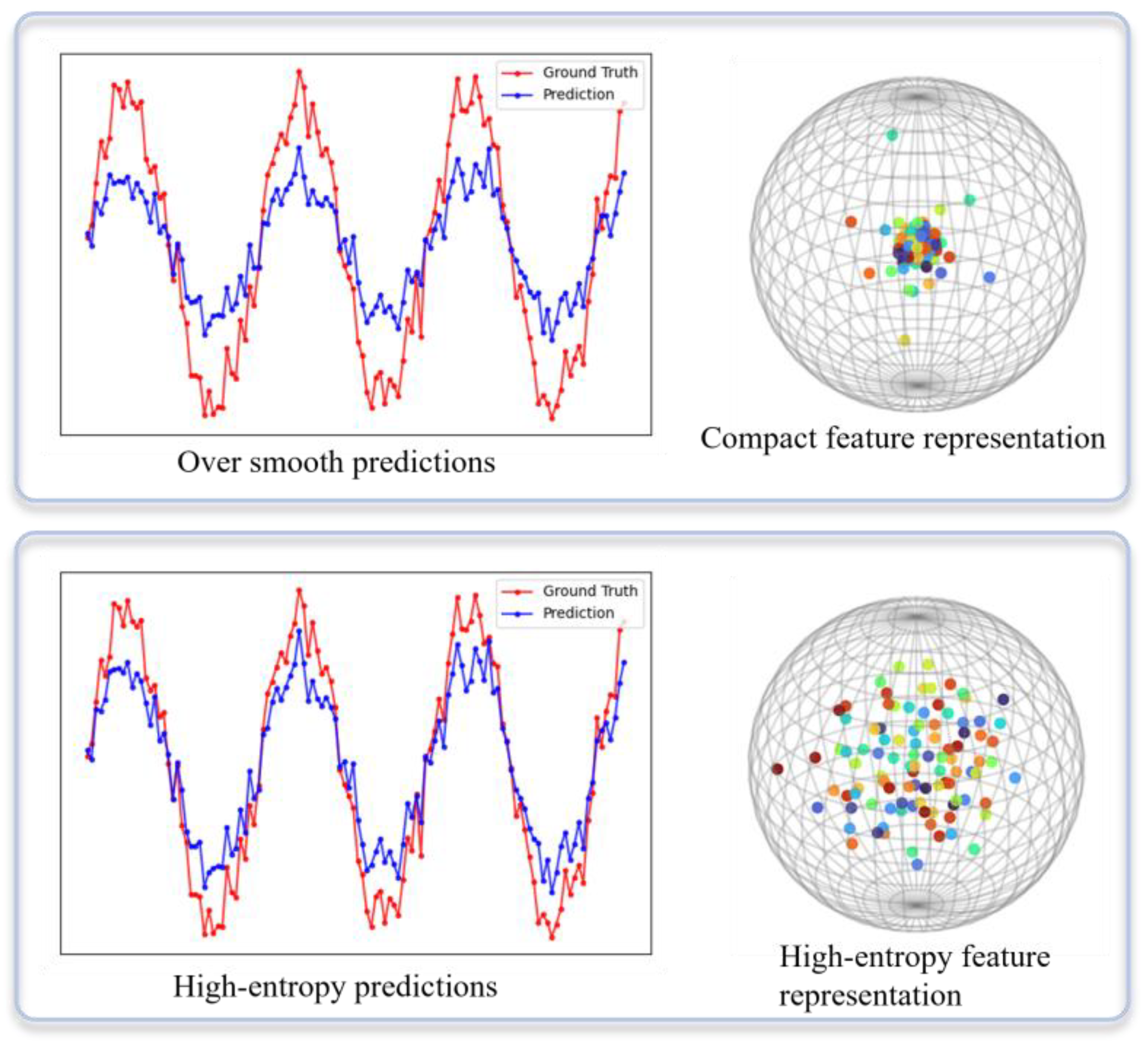

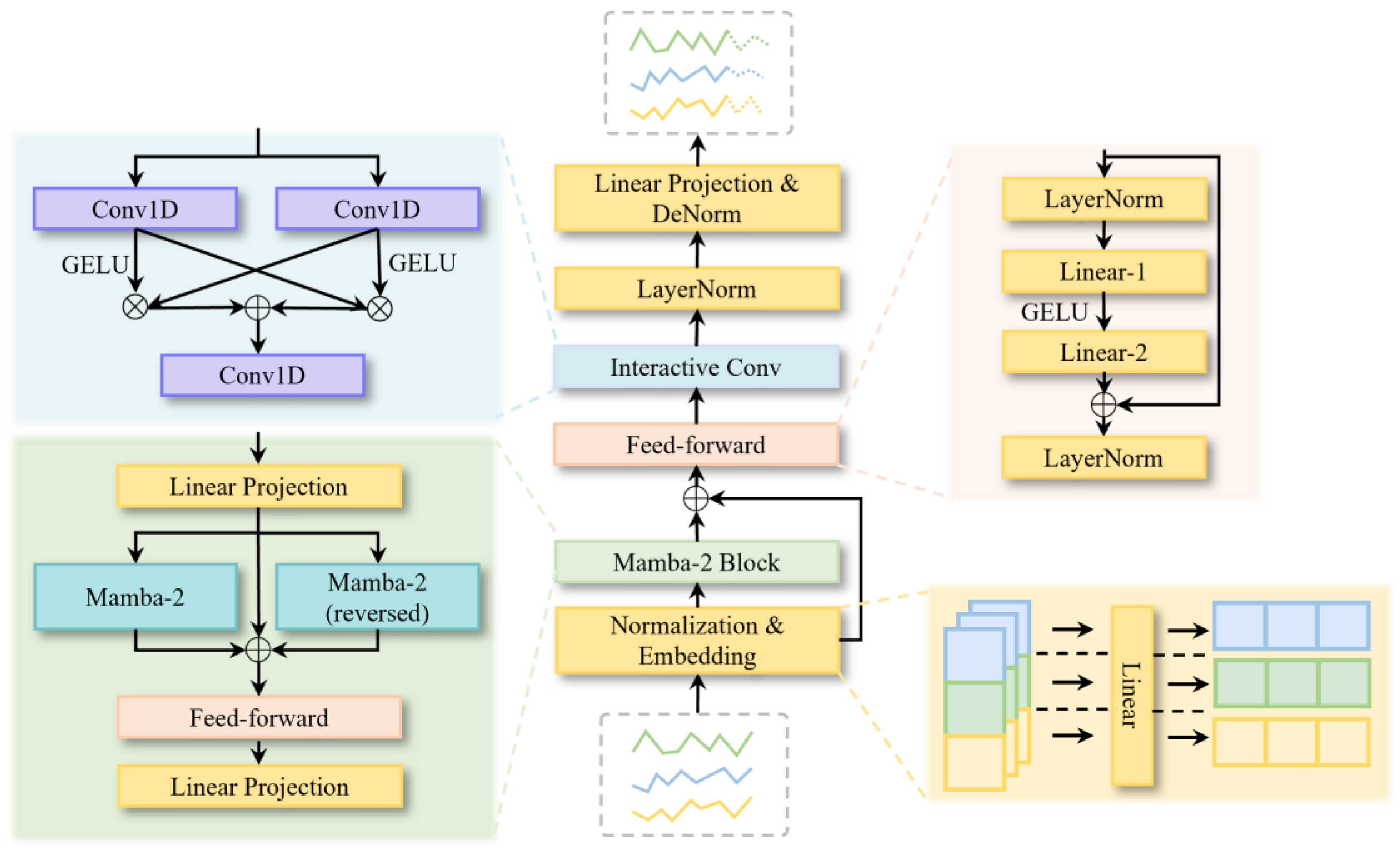

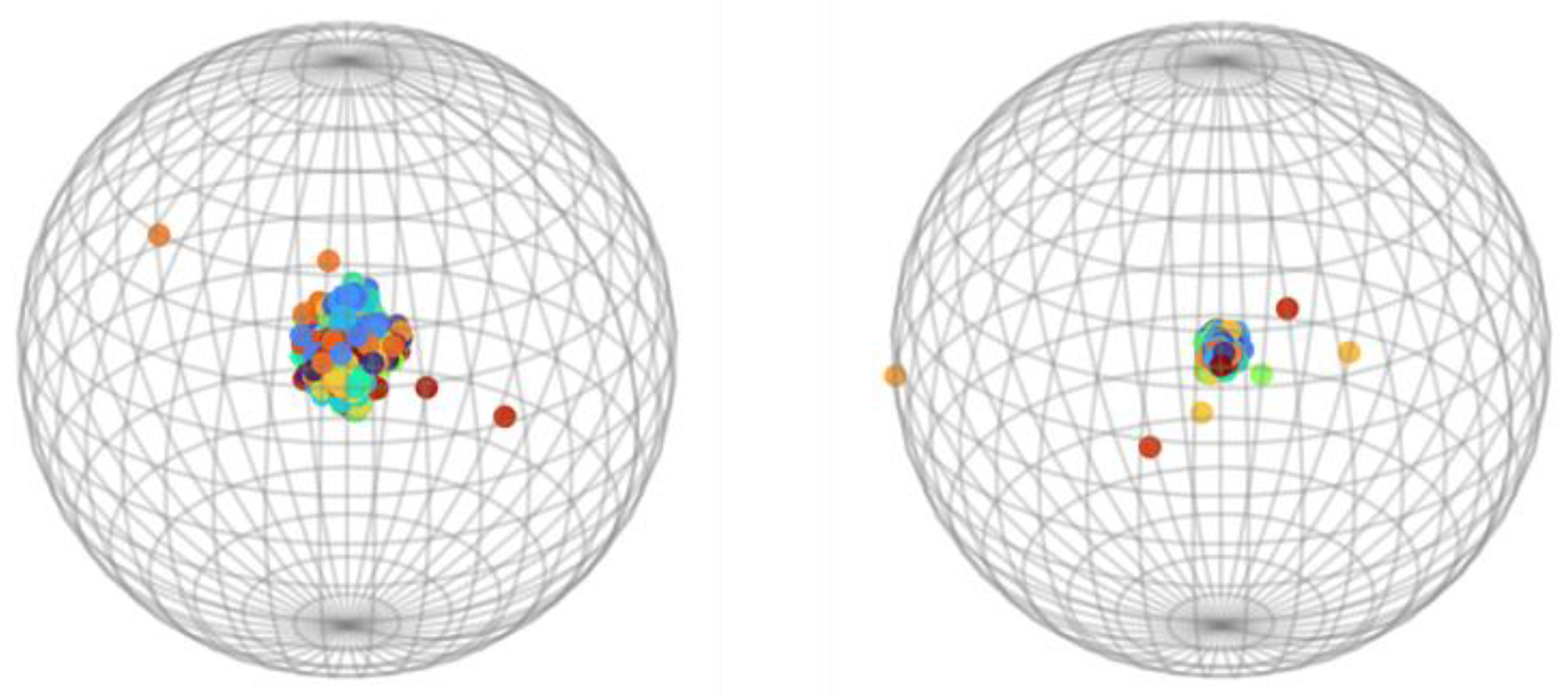

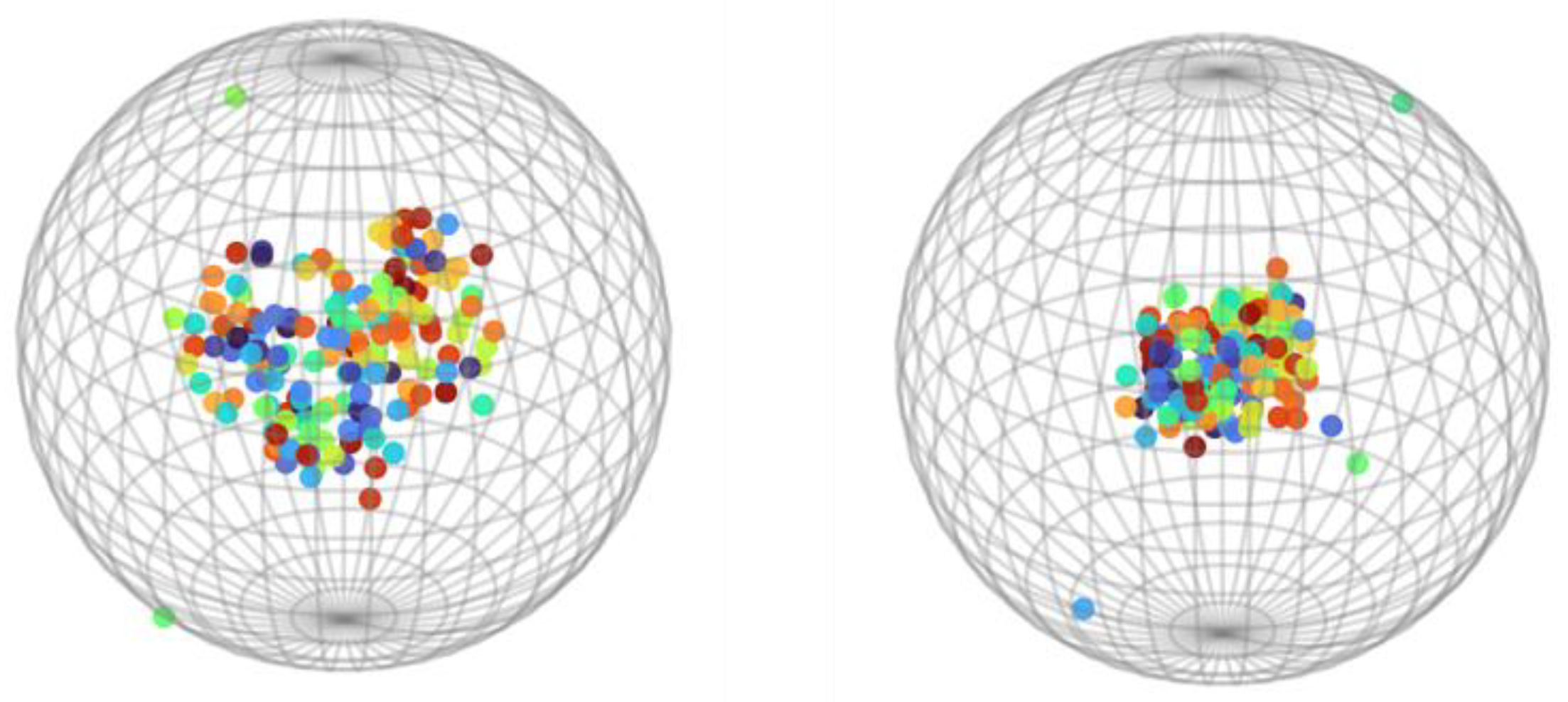

Long-sequence traffic flow forecasting plays a crucial role in intelligent transportation systems. However, existing Transformer-based approaches face a quadratic complexity bottleneck in computation and are prone to over-smoothing in deep architectures. This results in overly averaged predictions that fail to capture the peaks and troughs of traffic flow. To address these issues, we propose a State-Space Generative Adversarial Network (SSGAN) with a state-space generator and a multi-scale convolutional discriminator. Specifically, a bidirectional Mamba-2 model is designed as the generator to leverage the linear complexity and efficient forecasting capability of state-space models for long-sequence modeling. Meanwhile, the discriminator incorporates a multi-scale convolutional structure to extract traffic features from the frequency domain, thereby capturing flow patterns across different scales, alleviating the over-smoothing issue, and enhancing discriminative ability. Through adversarial training, the model is able to better approximate the true distribution of traffic flow. Experiments conducted on four real-world public traffic flow datasets demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms baselines in both forecasting accuracy and computational efficiency.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel adversarial learning framework for long-sequence traffic flow forecasting that integrates state-space modeling with multi-scale convolution.

- We design a bidirectional dual state-space generator that maintains linear complexity while enhancing long-sequence forecasting performance.

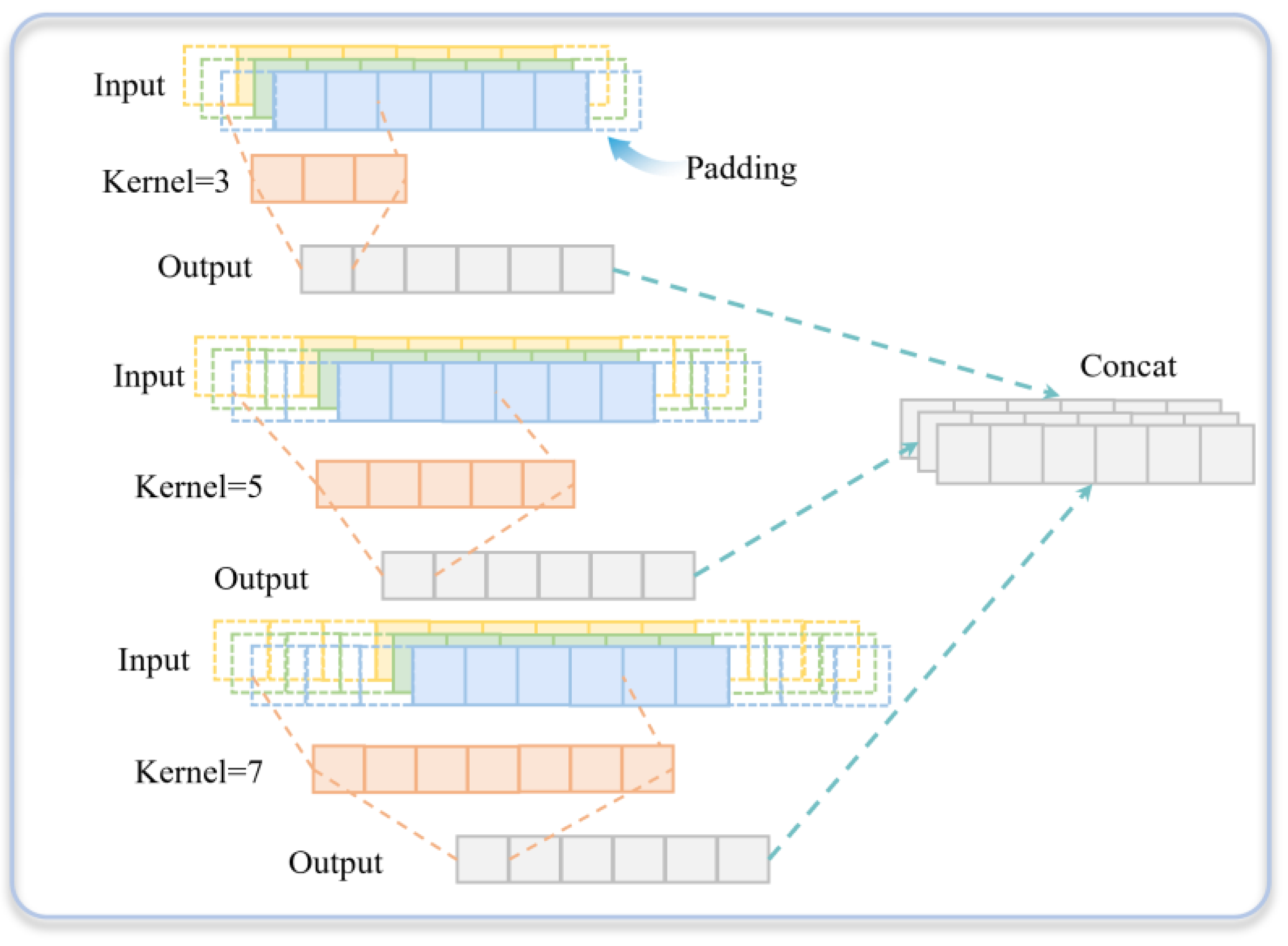

- We introduce a multi-scale convolutional structure in the discriminator, enabling joint extraction of traffic features from the frequency domain to effectively mitigate over-smoothing and improve discriminative capability.

2. Related Work

2.1. Transformer-Based Methods

2.2. Convolution-Based Methods

2.3. State Space Model-Based Methods

2.4. Generative Adversarial Network-Based Methods

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Traffic Flow Forecasting

3.2. State Space Models

3.3. Generative Adversarial Network

4. Methodology

4.1. Generator

4.2. Discriminator

5. Experiments

5.1. Datasets and Baselines

- Mamba-based model. S-Mamba is built upon the Mamba model and efficiently captures sequential dependencies through linear encoding and feed-forward networks [28].

- Transformer-based models. iTransformer applies attention mechanisms along the variable dimension by transposing the input, modeling multivariate correlations while leveraging feed-forward networks for nonlinear representation learning [10]. Crossformer employs a dimension-segment-wise embedding to preserve temporal and variable information and integrates a two-stage attention mechanism to simultaneously model cross-time and cross-dimension dependencies [8].

- Linear models. TiDE combines an MLP-based encoder–decoder architecture with nonlinear mapping and covariate handling to achieve high-accuracy long-term time series forecasting with fast inference [37]. RLinear efficiently captures periodic features using linear mapping, invertible normalization, and channel-independent mechanisms [38]. DLinear, with its simple linear structure, reveals the temporal information loss issue inherent in Transformer-based models for long-term forecasting [22].

- Convolution-based model. TimesNet transforms one-dimensional time series into a set of two-dimensional tensors based on multiple periodicities, decomposing complex temporal variations into intra-period and inter-period changes, which are then modeled efficiently using 2D convolution kernels [39].

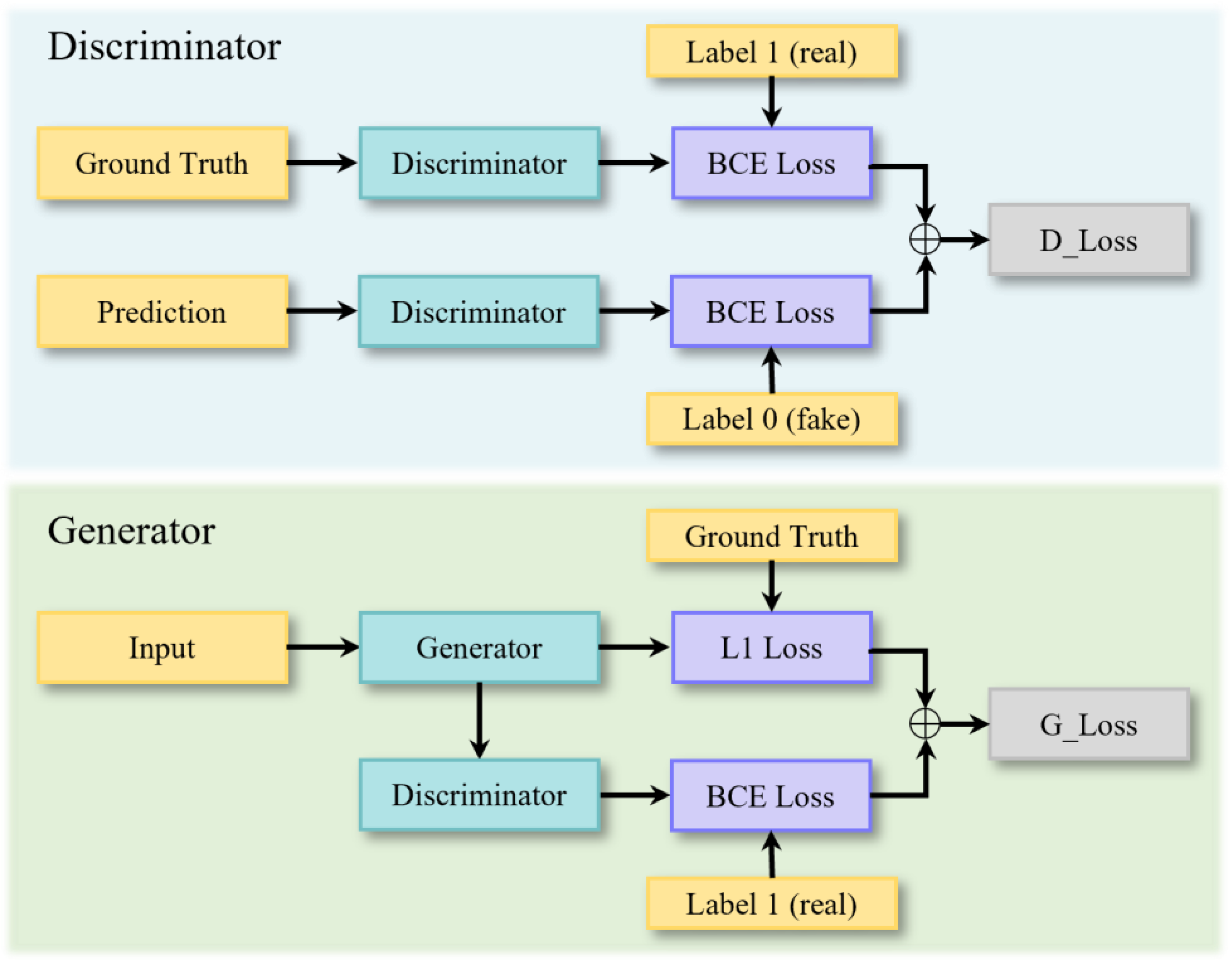

5.2. Forecasting Results

5.3. Hyperparameter Experiments

5.4. Ablation study

- Bidirectional Mamba-2 replaced with unidirectional: The bidirectional Mamba-2 module in the generator was replaced with a unidirectional structure to evaluate the contribution of bidirectional temporal dependency modeling to long-sequence prediction performance.

- Removal of the interactive convolution block: The interactive convolution block in the generator was removed to examine its role in feature fusion.

- Removal of the adversarial framework (generator-only): The discriminator in the GAN framework was completely removed, leaving only the generator for prediction, in order to analyze the importance of the adversarial mechanism in alleviating over-smoothing and improving the capture of fine-grained temporal patterns.

5.5. Model Efficiency

6. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, R.; Lin, W.; Ren, G.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y. Interaction-Aware Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Using Spatial-Temporal Dynamic Graph Neural Network. Knowledge-Based Systems 2025, 114187.

- Zhang, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Han, Y.; Liu, P.; Huang, W. A data-driven optimization-based approach for freeway traffic state estimation based on heterogeneous sensor data fusion. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2024, 189, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, R. Prescriptive analytics for freeway traffic state estimation by multi-source data fusion. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2025, 198, 104105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hua, X.; Yu, W.; Lin, W.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Q. Safety and efficiency-oriented adaptive strategy controls for connected and automated vehicles in unstable communication environment. Accident Analysis Prevention 2025, 220, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, P. A novel ranking method based on semi-SPO for battery swap** allocation optimization in a hybrid electric transit system. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2024, 188, 103611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A. N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR, 2022; pp. 27268-27286.

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Crossformer: Transformer utilizing cross-dimension dependency for multivariate time series forecasting. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Nie, Y.; Nguyen, N. H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A Time Series is Worth 64 Words: Long-term Forecasting with Transformers. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. iTransformer: Inverted Transformers Are Effective for Time Series Forecasting. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Luo, Q.; He, S.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. LSTTN: A long-short term transformer-based spatiotemporal neural network for traffic flow forecasting. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 293, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Long, B. A multi-channel spatial-temporal transformer model for traffic flow forecasting. Information Sciences 2024, 671, 120648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Hui, B.; Shao, Z.; Deng, L.; Liu, X.; ... Zheng, K. (2025, July). Efficient large-scale traffic forecasting with transformers: A spatial data management perspective. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 1 (pp. 307–317).

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Xu, H.; Gao, W.; ... Zhang, L. Soft: Softmax-free transformer with linear complexity. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 21297–21309.

- Gu, A.; Dao, T.; Ermon, S.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Hippo: Recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Gu, A. Transformers are ssms: Generalized models and efficient algorithms through structured state space duality. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.21060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, D.; Eldele, E.; Hu, Q. (2025, April). Hierarchical classification auxiliary network for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 39, No. 19, pp. 20743–20751).

- Goodfellow, I. J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; ... Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27.

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in time series: a survey. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2023; pp. 6778–6786. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023; Vol. 37, 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, M. A hybrid prediction method for realistic network traffic with temporal convolutional network and LSTM. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2021, 19, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldele, E.; Ragab, M.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M.; Li, X. Tslanet: Rethinking transformers for time series representation learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xie, D.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Duan, S. MDCNet: Long-term time series forecasting with mode decomposition and 2D convolution. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 299, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, S.; Ferreira, M. C.; Machado, J. J. M.; Tavares, J. M. R. Enhancing intelligent transportation systems with a more efficient model for long-term traffic predictions based on an attention mechanism and a residual temporal convolutional network. Neural Networks 2025, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yoon, H.; Kang, M. CASA: CNN Autoencoder-based Score Attention for Efficient Multivariate Long-term Time-series Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.02011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Kong, F.; Feng, S.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Is mamba effective for time series forecasting? Neurocomputing 2025, 619, 129178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, G.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, J.; Cao, Q. MGCN: Mamba-integrated spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for long-term traffic forecasting. Knowledge-Based Systems 2025, 309, 112875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Z. iTransMamba: A lightweight spatio-temporal network based on long-term traffic flow forecasting. Knowledge-Based Systems 2025, 317, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.; Mabrok, M.; Zorba, N. MCST-Mamba: Multivariate Mamba-Based Model for Traffic Prediction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.03927. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cao, J.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, G.; Li, Z.; ... Li, Q. ST-Camba: A decoupled-free spatiotemporal graph fusion state space model with linear complexity for efficient traffic forecasting. Information Fusion 2025, 103495.

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Shen, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, R.; Zhou, X.; ... Wu, Q. SATP-GAN: Self-attention based generative adversarial network for traffic flow prediction. Transportmetrica B: Transport Dynamics 2021, 9, 552-568.

- Khaled, A.; Elsir, A. M. T.; Shen, Y. TFGAN: Traffic forecasting using generative adversarial network with multi-graph convolutional network. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 249, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, Q.; Lin, W.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Ren, G. Estimation of Arterial Path Flow Considering Flow Distribution Consistency: A Data-Driven Semi-Supervised Method. Systems 2024, 12(11), 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Petty, K.; Skabardonis, A.; Varaiya, P.; Jia, Z. Freeway performance measurement system: mining loop detector data. Transportation research record 2001, 1748, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Kong, W.; Leach, A.; Mathur, S.; Sen, R.; Yu, R. Long-term forecasting with tide: Time-series dense encoder. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08424. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Qi, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z. Revisiting long-term time series forecasting: An investigation on linear mapping. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. TimesNet: Temporal 2D-Variation Modeling for General Time Series Analysis. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

| Dataset | Nodes | Time Steps | Dataset size | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEMS03 | 358 | 26209 | 6:2:2 | 5 min |

| PEMS04 | 307 | 16992 | 6:2:2 | 5 min |

| PEMS07 | 883 | 28224 | 6:2:2 | 5 min |

| PEMS08 | 170 | 17856 | 6:2:2 | 5 min |

| Models | SSGAN (ours) |

S-Mamba (2025) |

iTransformer (2024) |

RLinear (2023) |

Crossformer (2023) |

TiDE (2023) |

TimesNet (2023) |

DLinear (2023) |

|||||||||

| Metric | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | |

| PEMS03 | 12 | 0.072 | 0.174 | 0.065 | 0.169 | 0.071 | 0.174 | 0.126 | 0.236 | 0.090 | 0.203 | 0.178 | 0.305 | 0.085 | 0.192 | 0.122 | 0.243 |

| 24 | 0.086 | 0.191 | 0.087 | 0.196 | 0.093 | 0.201 | 0.246 | 0.334 | 0.121 | 0.240 | 0.257 | 0.371 | 0.118 | 0.223 | 0.201 | 0.317 | |

| 48 | 0.120 | 0.225 | 0.133 | 0.243 | 0.125 | 0.236 | 0.551 | 0.529 | 0.202 | 0.317 | 0.379 | 0.463 | 0.155 | 0.260 | 0.333 | 0.425 | |

| 96 | 0.147 | 0.248 | 0.201 | 0.305 | 0.164 | 0.275 | 1.057 | 0.787 | 0.262 | 0.367 | 0.490 | 0.539 | 0.228 | 0.317 | 0.457 | 0.515 | |

| Avg | 0.106 | 0.210 | 0.122 | 0.228 | 0.113 | 0.221 | 0.495 | 0.472 | 0.169 | 0.281 | 0.326 | 0.419 | 0.147 | 0.248 | 0.278 | 0.375 | |

| PEMS04 | 12 | 0.070 | 0.169 | 0.076 | 0.180 | 0.078 | 0.183 | 0.138 | 0.252 | 0.098 | 0.218 | 0.219 | 0.340 | 0.087 | 0.195 | 0.148 | 0.272 |

| 24 | 0.079 | 0.179 | 0.084 | 0.193 | 0.095 | 0.205 | 0.258 | 0.348 | 0.131 | 0.256 | 0.292 | 0.398 | 0.103 | 0.215 | 0.224 | 0.340 | |

| 48 | 0.091 | 0.193 | 0.115 | 0.224 | 0.120 | 0.233 | 0.572 | 0.544 | 0.205 | 0.326 | 0.409 | 0.478 | 0.136 | 0.250 | 0.355 | 0.437 | |

| 96 | 0.103 | 0.207 | 0.137 | 0.248 | 0.150 | 0.262 | 1.137 | 0.820 | 0.402 | 0.457 | 0.492 | 0.532 | 0.190 | 0.303 | 0.452 | 0.504 | |

| Avg | 0.086 | 0.187 | 0.103 | 0.211 | 0.111 | 0.221 | 0.526 | 0.491 | 0.209 | 0.314 | 0.353 | 0.437 | 0.129 | 0.241 | 0.295 | 0.388 | |

| PEMS07 | 12 | 0.068 | 0.152 | 0.063 | 0.159 | 0.067 | 0.165 | 0.118 | 0.235 | 0.094 | 0.200 | 0.173 | 0.304 | 0.082 | 0.181 | 0.115 | 0.242 |

| 24 | 0.076 | 0.167 | 0.081 | 0.183 | 0.088 | 0.190 | 0.242 | 0.341 | 0.139 | 0.247 | 0.271 | 0.383 | 0.101 | 0.204 | 0.210 | 0.329 | |

| 48 | 0.096 | 0.185 | 0.093 | 0.192 | 0.110 | 0.215 | 0.562 | 0.541 | 0.311 | 0.369 | 0.446 | 0.495 | 0.134 | 0.238 | 0.398 | 0.458 | |

| 96 | 0.122 | 0.203 | 0.117 | 0.217 | 0.139 | 0.245 | 1.096 | 0.795 | 0.396 | 0.442 | 0.628 | 0.577 | 0.181 | 0.279 | 0.594 | 0.553 | |

| Avg | 0.091 | 0.177 | 0.089 | 0.188 | 0.101 | 0.204 | 0.504 | 0.478 | 0.235 | 0.315 | 0.380 | 0.440 | 0.124 | 0.225 | 0.329 | 0.395 | |

| PEMS08 | 12 | 0.139 | 0.182 | 0.076 | 0.178 | 0.079 | 0.182 | 0.133 | 0.247 | 0.165 | 0.214 | 0.227 | 0.343 | 0.112 | 0.212 | 0.154 | 0.276 |

| 24 | 0.162 | 0.200 | 0.104 | 0.209 | 0.115 | 0.219 | 0.249 | 0.343 | 0.215 | 0.260 | 0.318 | 0.409 | 0.141 | 0.238 | 0.248 | 0.353 | |

| 48 | 0.189 | 0.218 | 0.167 | 0.228 | 0.186 | 0.235 | 0.569 | 0.544 | 0.315 | 0.355 | 0.497 | 0.510 | 0.198 | 0.283 | 0.440 | 0.470 | |

| 96 | 0.217 | 0.237 | 0.245 | 0.280 | 0.221 | 0.267 | 1.166 | 0.814 | 0.377 | 0.397 | 0.721 | 0.592 | 0.320 | 0.351 | 0.674 | 0.565 | |

| Avg | 0.177 | 0.209 | 0.148 | 0.224 | 0.150 | 0.226 | 0.529 | 0.487 | 0.268 | 0.307 | 0.441 | 0.464 | 0.193 | 0.271 | 0.379 | 0.416 | |

| 1st Count | 11 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Models | Horizon | PEMS03 | PEMS04 | PEMS07 | PEMS08 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | ||

| SSGAN | 12 | 0.072 | 0.174 | 0.070 | 0.169 | 0.068 | 0.152 | 0.139 | 0.182 |

| 24 | 0.086 | 0.191 | 0.079 | 0.179 | 0.076 | 0.167 | 0.162 | 0.200 | |

| 48 | 0.120 | 0.225 | 0.091 | 0.193 | 0.096 | 0.185 | 0.189 | 0.218 | |

| 96 | 0.147 | 0.248 | 0.103 | 0.207 | 0.122 | 0.203 | 0.217 | 0.237 | |

| Avg | 0.106 | 0.210 | 0.086 | 0.187 | 0.091 | 0.177 | 0.177 | 0.209 | |

| Bidirectional Mamba-2 replaced with unidirectional | 12 | 0.072 | 0.174 | 0.070 | 0.169 | 0.070 | 0.154 | 0.140 | 0.186 |

| 24 | 0.086 | 0.192 | 0.079 | 0.180 | 0.077 | 0.167 | 0.159 | 0.200 | |

| 48 | 0.117 | 0.223 | 0.093 | 0.196 | 0.099 | 0.191 | 0.190 | 0.220 | |

| 96 | 0.149 | 0.252 | 0.104 | 0.208 | 0.124 | 0.207 | 0.225 | 0.244 | |

| Avg | 0.106 | 0.210 | 0.087 | 0.188 | 0.093 | 0.180 | 0.179 | 0.213 | |

| Removal of the interactive convolution block | 12 | 0.071 | 0.173 | 0.070 | 0.169 | 0.064 | 0.153 | 0.129 | 0.184 |

| 24 | 0.087 | 0.194 | 0.078 | 0.179 | 0.078 | 0.169 | 0.162 | 0.202 | |

| 48 | 0.118 | 0.223 | 0.090 | 0.192 | 0.094 | 0.186 | 0.189 | 0.222 | |

| 96 | 0.160 | 0.256 | 0.102 | 0.207 | 0.126 | 0.208 | 0.214 | 0.241 | |

| Avg | 0.109 | 0.212 | 0.085 | 0.187 | 0.091 | 0.179 | 0.174 | 0.212 | |

| Removal of the adversarial framework | 12 | 0.074 | 0.176 | 0.070 | 0.169 | 0.071 | 0.154 | 0.133 | 0.182 |

| 24 | 0.085 | 0.190 | 0.080 | 0.180 | 0.079 | 0.167 | 0.162 | 0.201 | |

| 48 | 0.120 | 0.223 | 0.093 | 0.196 | 0.097 | 0.189 | 0.188 | 0.219 | |

| 96 | 0.152 | 0.252 | 0.104 | 0.207 | 0.121 | 0.203 | 0.227 | 0.245 | |

| Avg | 0.108 | 0.210 | 0.087 | 0.188 | 0.092 | 0.178 | 0.178 | 0.212 | |

| Model | MAE | MSE | Training speed (ms/iter) | Memory usage (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSGAN | 0.207 | 0.103 | 60 | 0.48 |

| S-Mamba | 0.248 | 0.137 | 486 | 8.75 |

| iTransformer | 0.262 | 0.150 | 161 | 6.07 |

| Crossformer | 0.457 | 0.402 | 543 | 41.07 |

| TimesNet | 0.303 | 0.190 | 1146 | 10.53 |

| DLinear | 0.504 | 0.452 | 92 | 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).