Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Quantify early-age reaction kinetics (setting time, heat evolution) to identify potential retardation from iron-rich slag addition.

- Characterize total porosity and pore-size distribution to evaluate the impact of iron oxides on microstructural development.

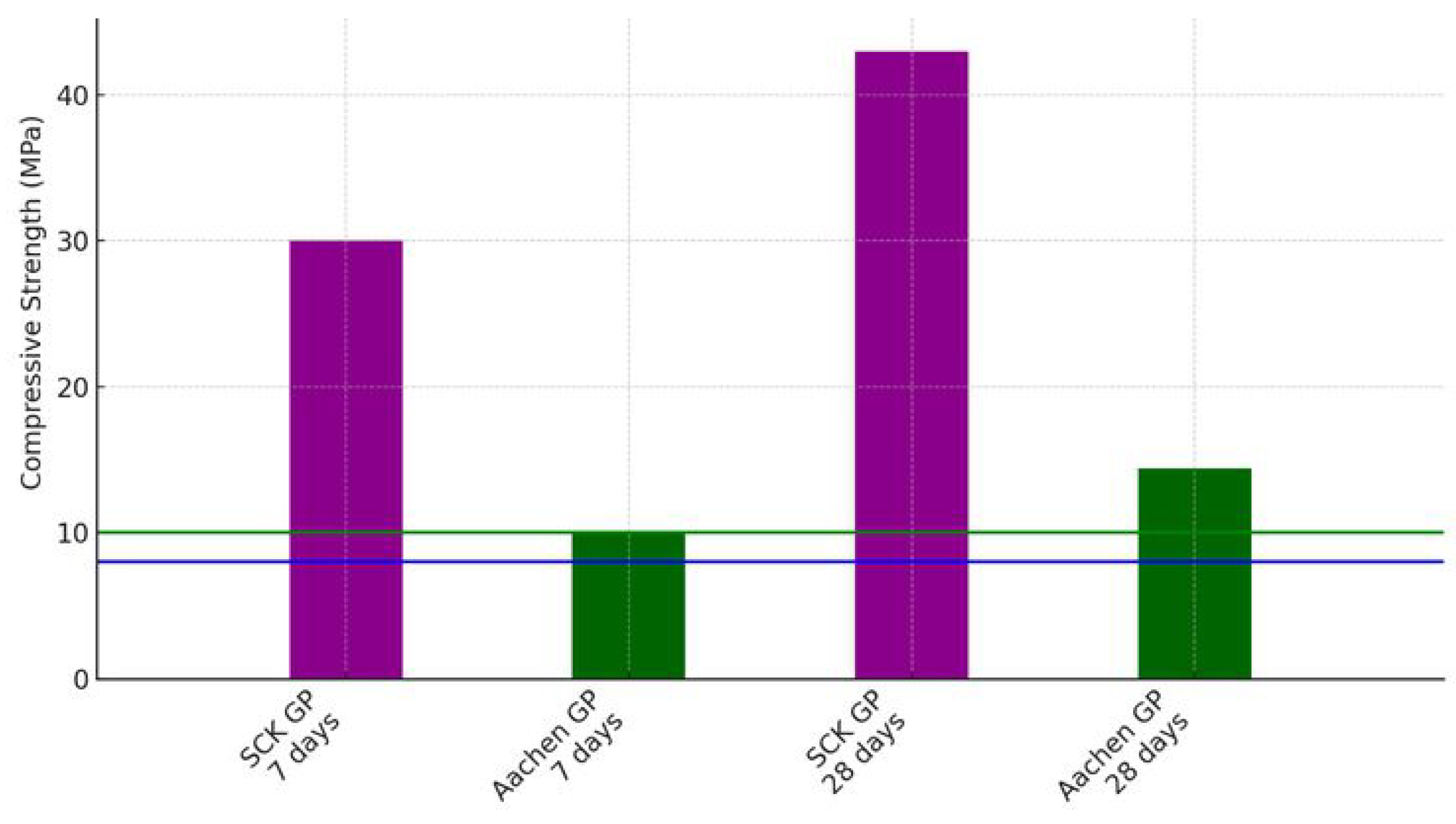

- Assess permeability and mechanical properties (7- and 28-day compressive strength) relative to regulatory standards.

- Compare results against a conventional blast furnace slag-only AAM reference (SCK GP).

2. Methodology

Materials and Experimental Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

- Prismatic molds (40 × 40 × 160 mm) for flexural strength testing.

- Cubic molds (40 × 40 × 40 mm) for compressive strength, water-accessible porosity, and microstructural analysis.

- Cylindrical molds (25 × 97 mm) for water permeability testing.

2.2. Curing Conditions

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.3.1. Fresh-State Behavior: Workability, Viscosity, and Setting Time

- Reference SCK GP (100 wt.% BFS)

- Aachen GP (50 wt.% iron-rich slag : 50 wt.% BFS)

- Modified Aachen GP (75 wt.% iron-rich slag : 25 wt.% BFS)

2.3.2. Mechanical Performance: Flexural and Compressive Strength Testing

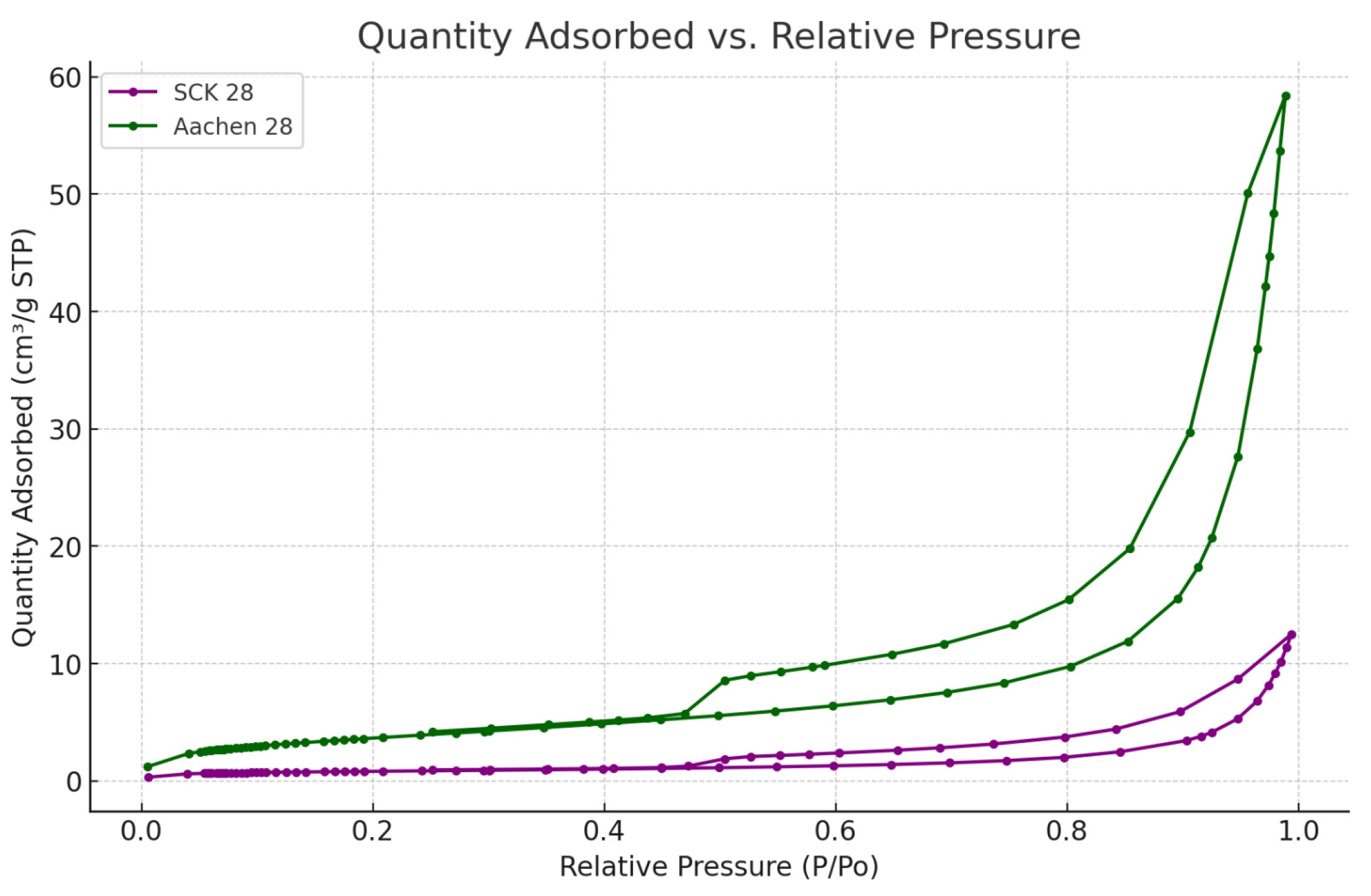

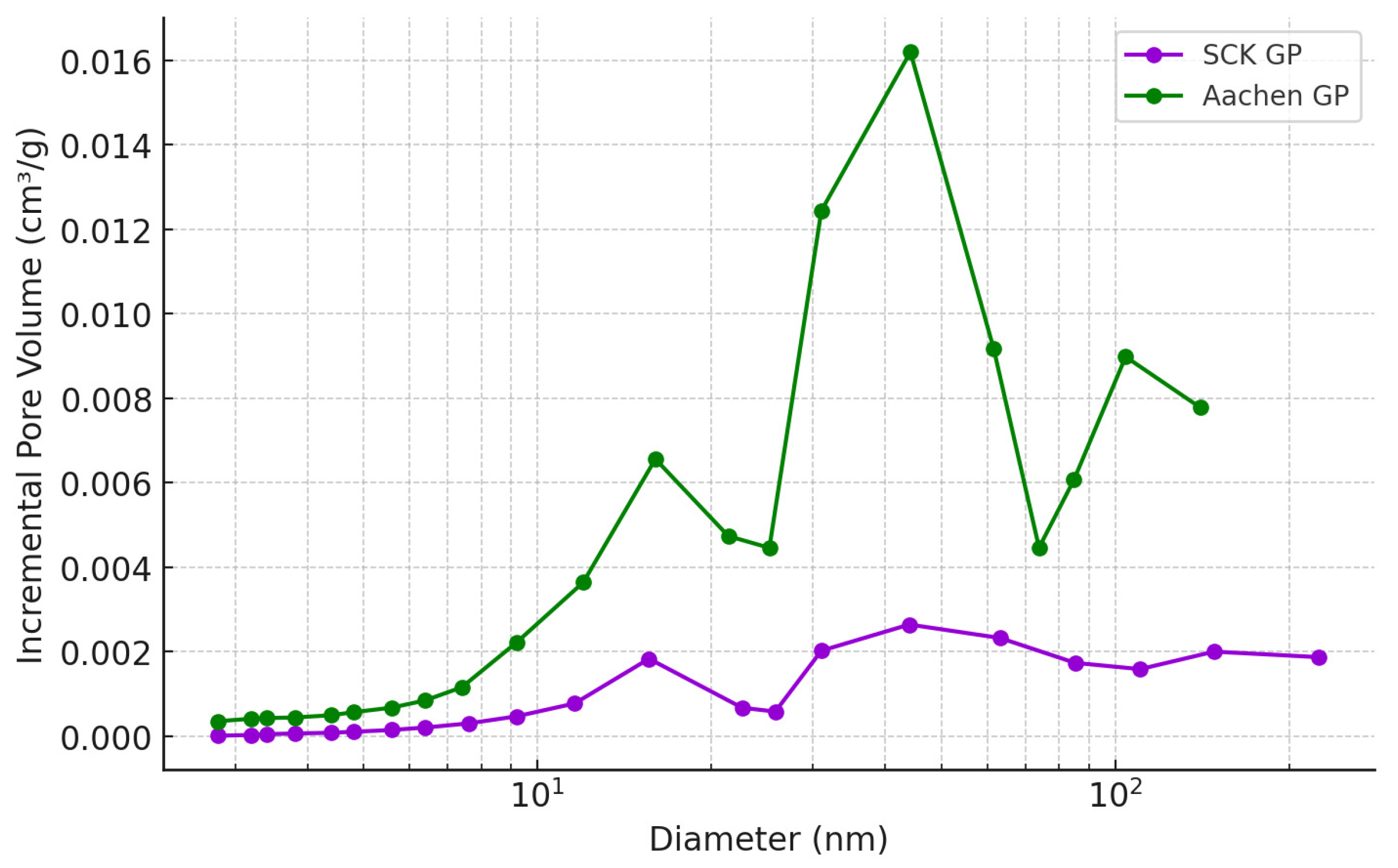

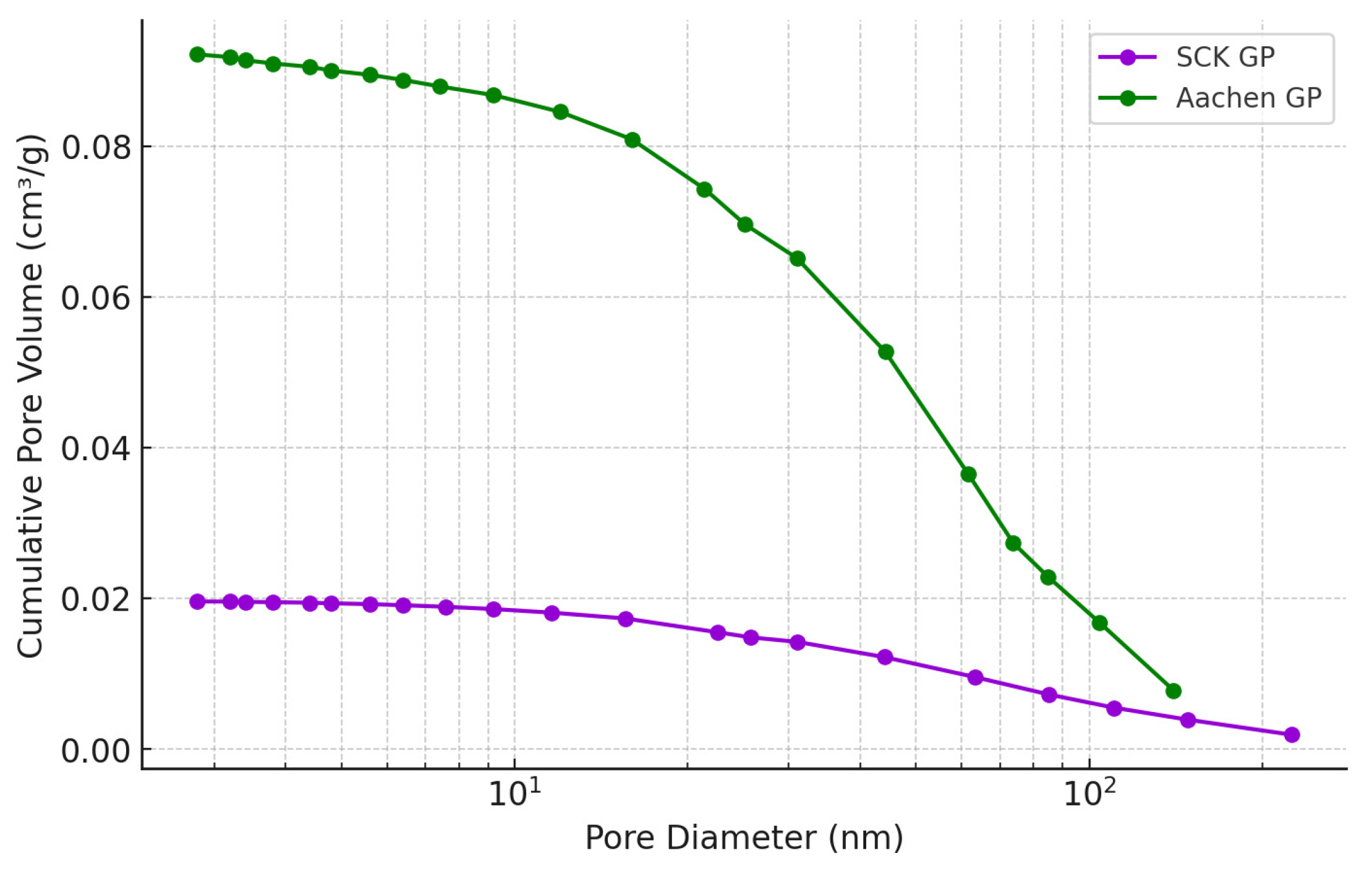

2.3.3. Porous Structure Analysis: Water-Accessible Porosity (WAP), Water Permeability (WP), and Nitrogen Adsorption (N2-Ads)

2.3.4. Morphological and Microstructural Analysis: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

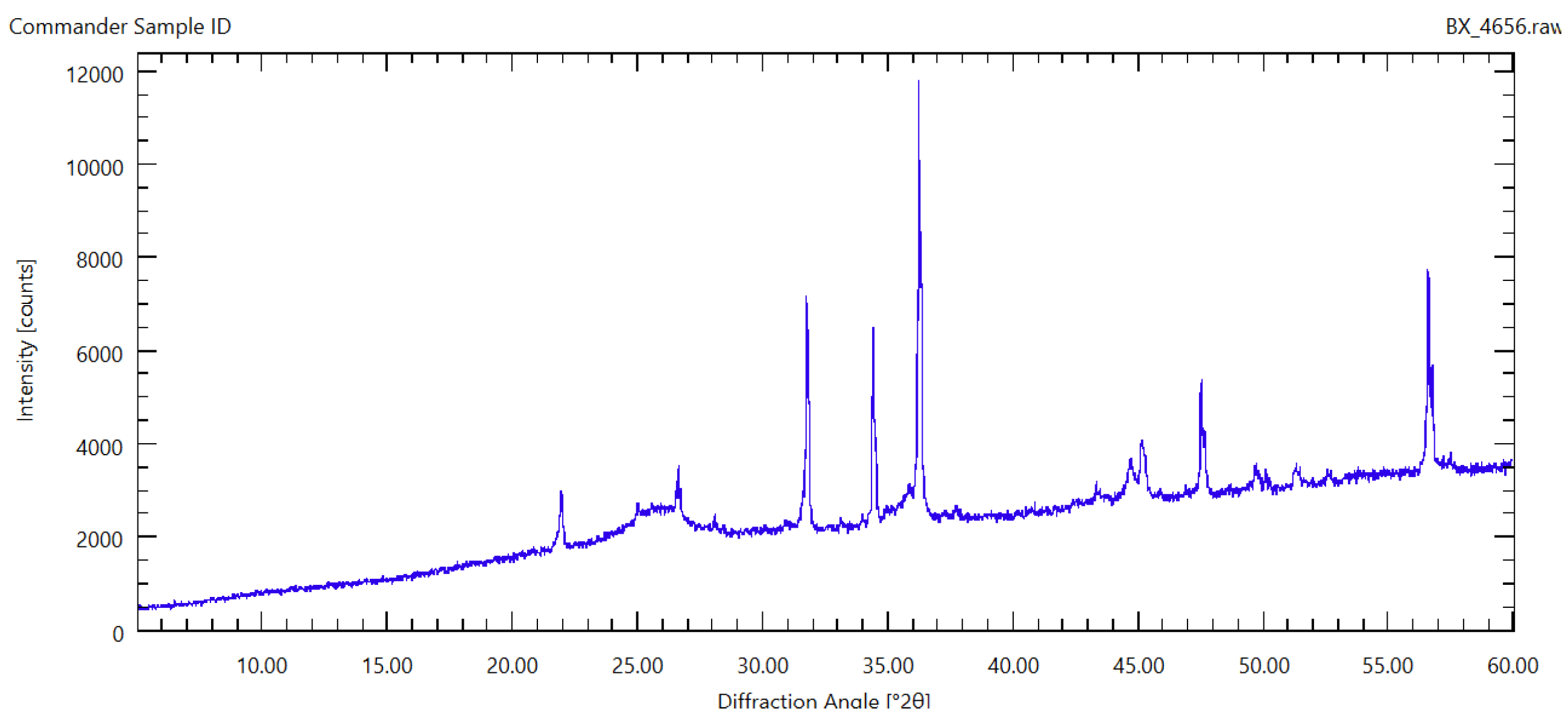

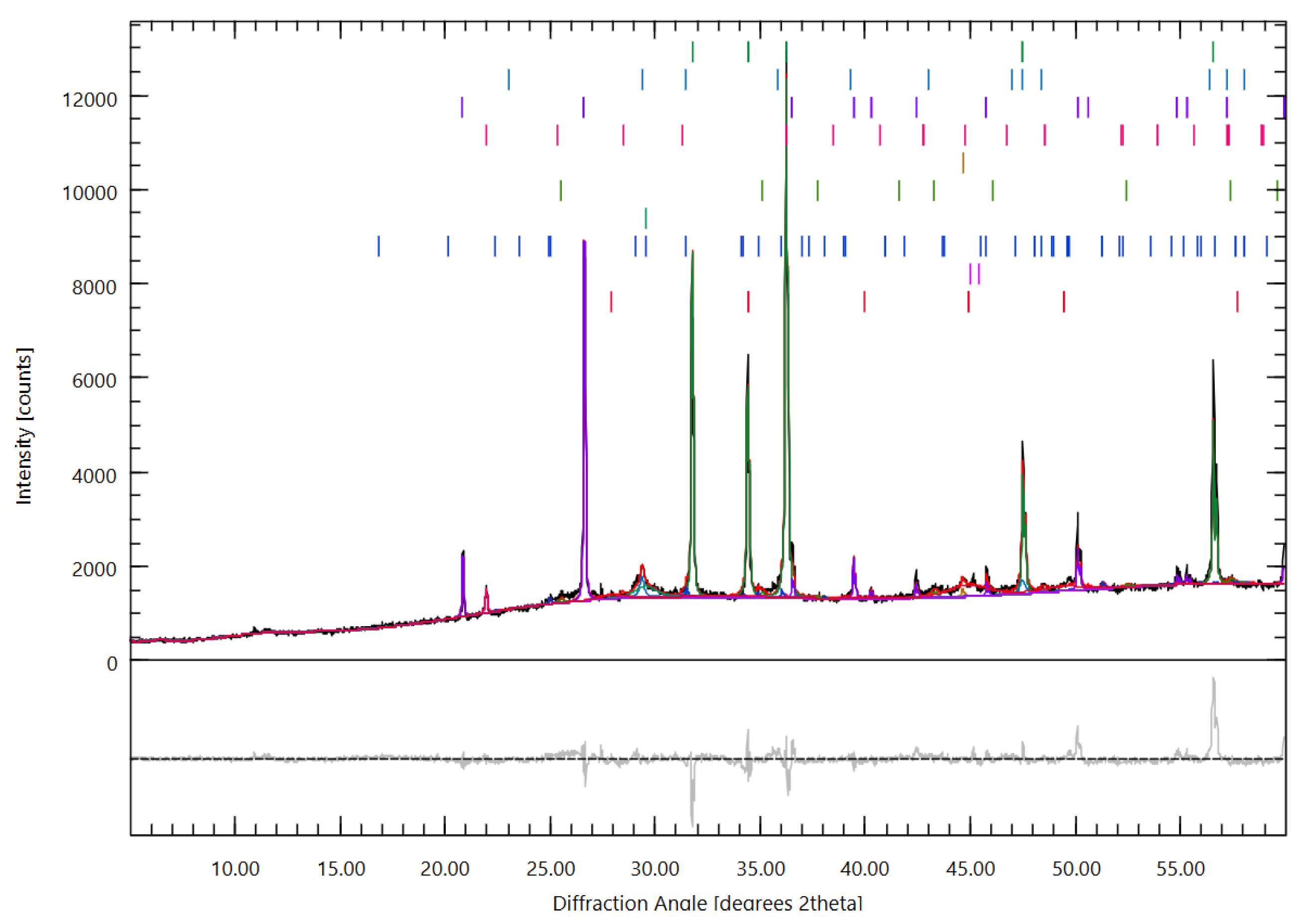

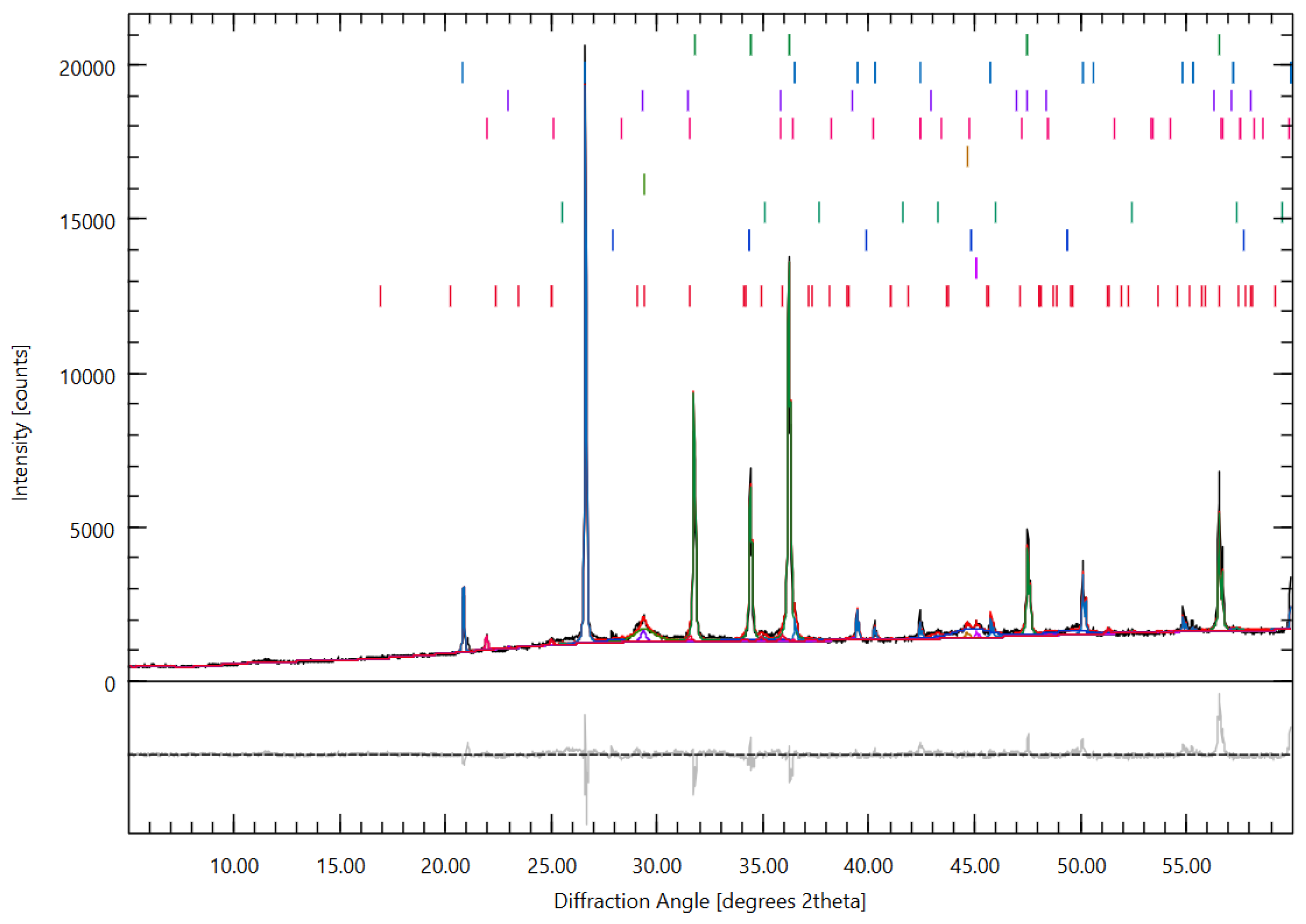

- Raw iron-rich slag powder (to establish baseline mineralogy)

- Cured SCK GP and Aachen GP samples at 7 and 28 days

3. Results and Discussion

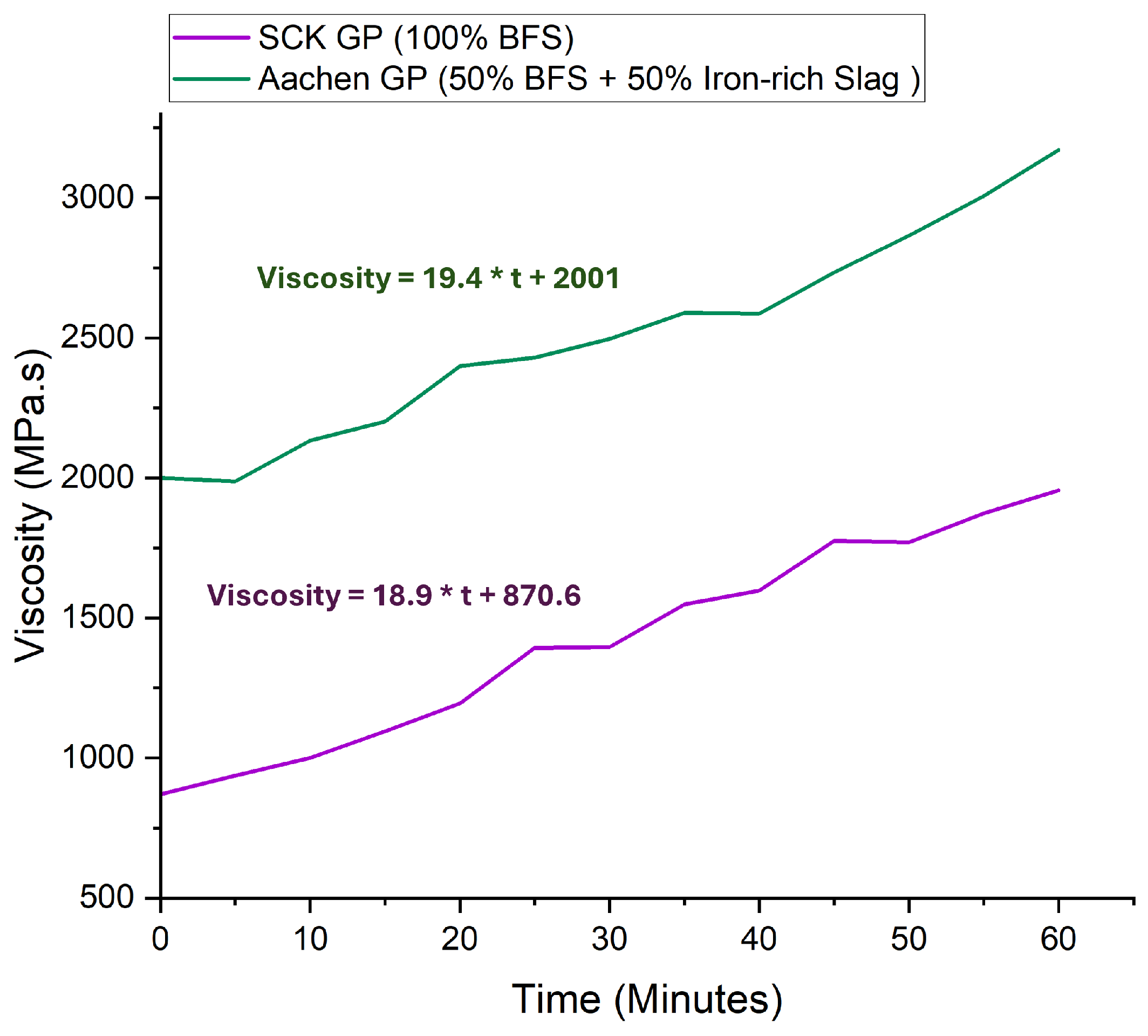

3.0.1. Workability, Viscosity, and Setting Time

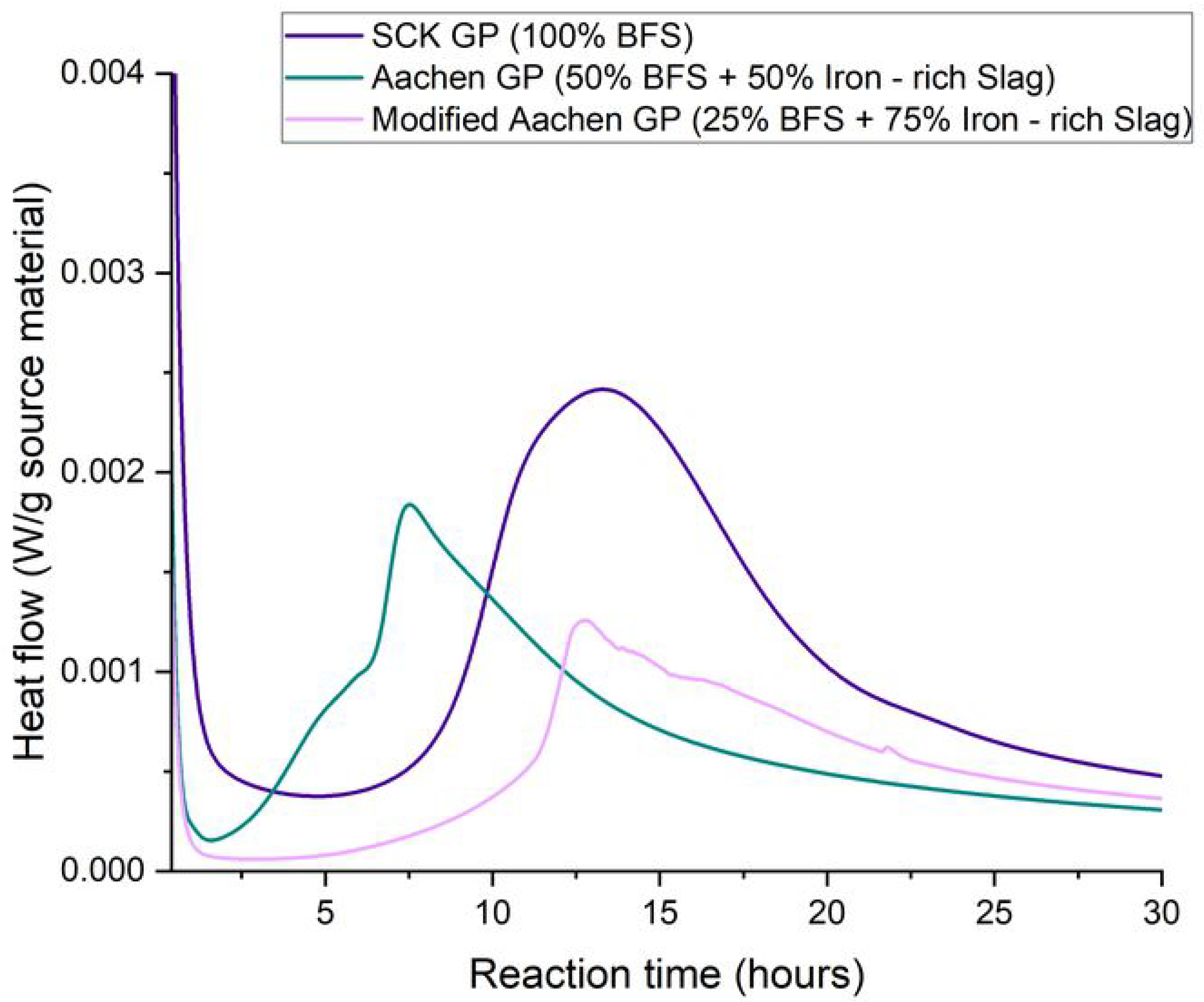

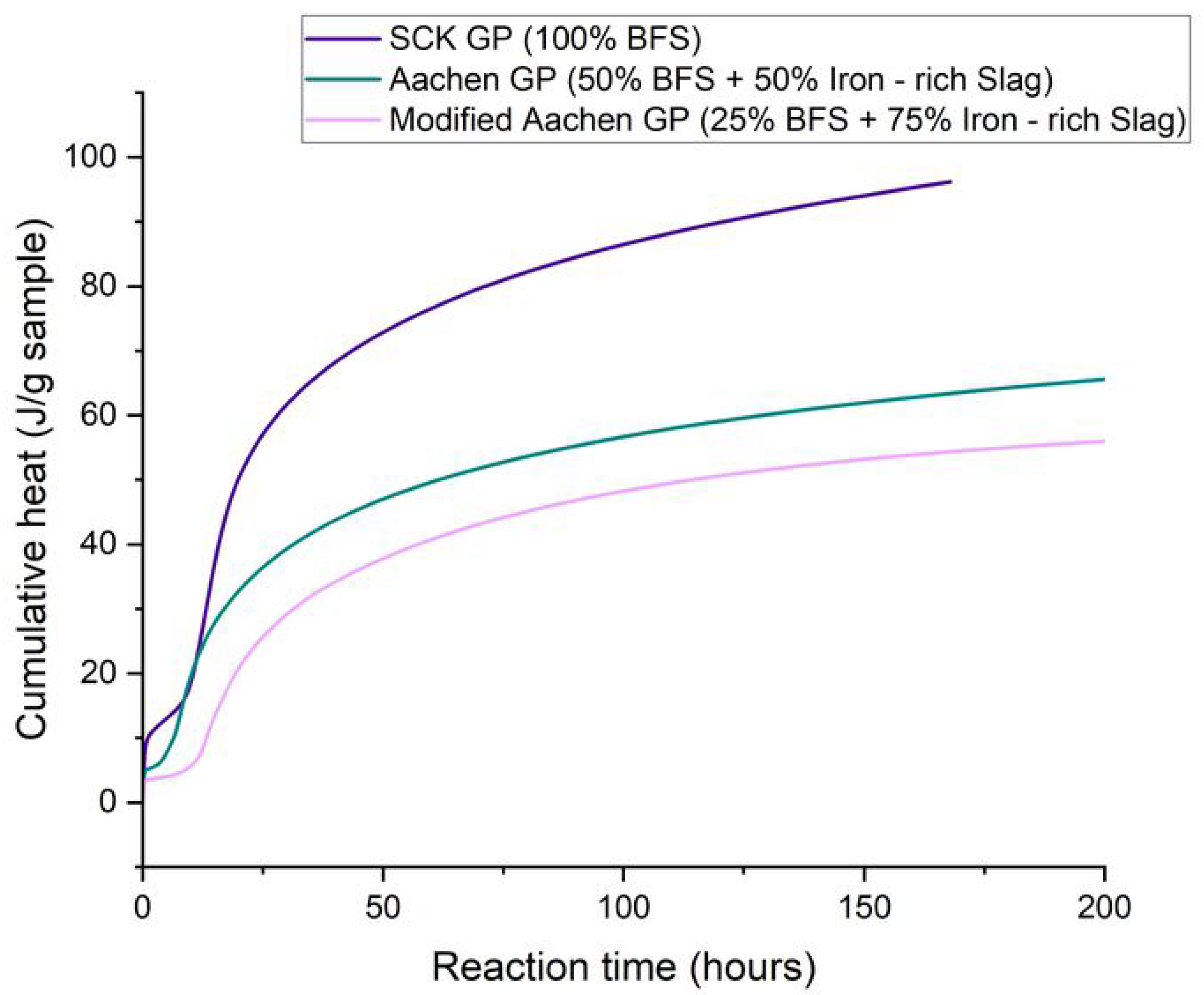

3.1. Reaction Kinetics: Isothermal Calorimetry

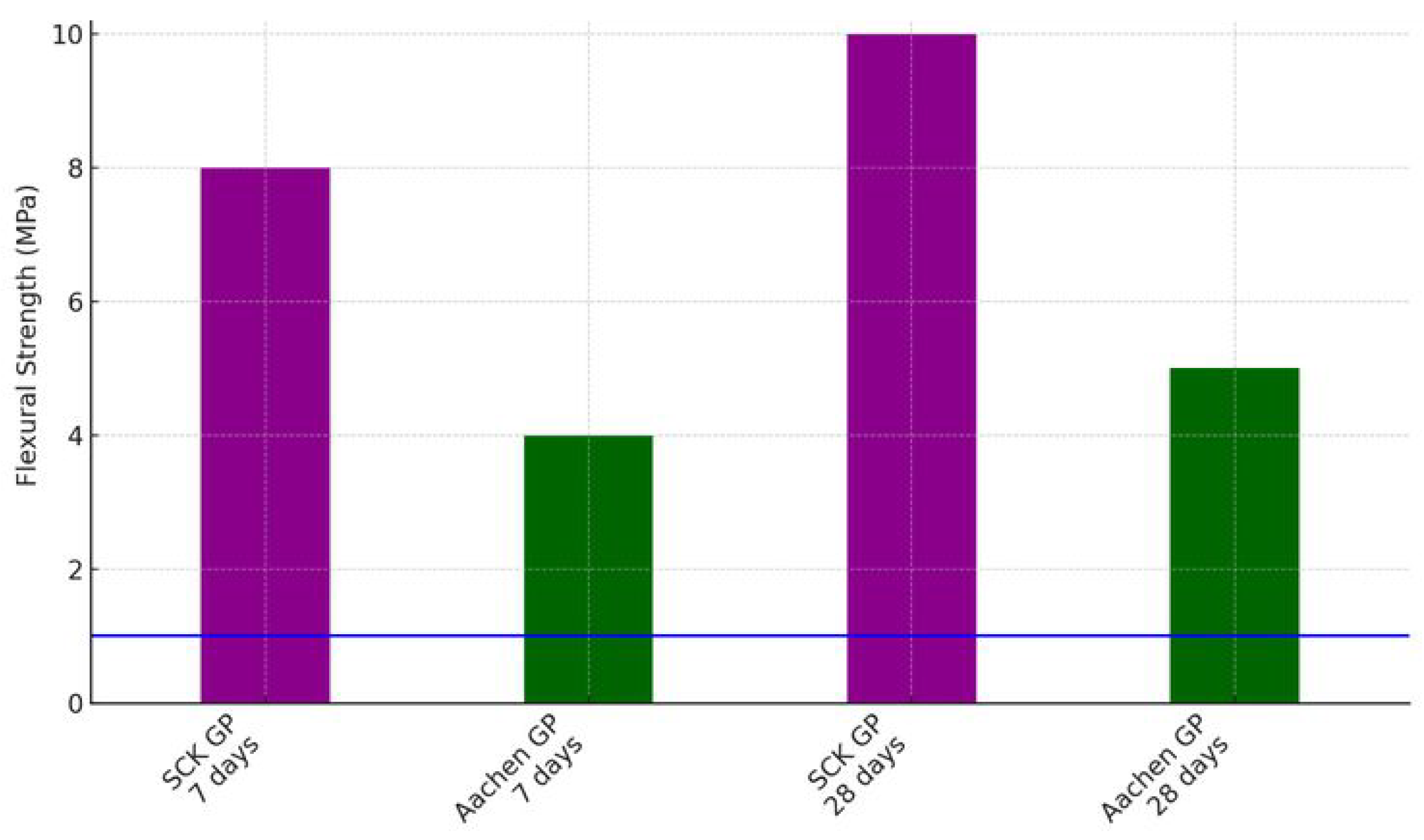

3.2. Flexural and Compressive Strength Testing

3.2.1. Water Absorption (WAP), Water Permeability (WP) and Nitrogen Adsorption (N-Ads)

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

- Unreacted Precursor Particles: Residual materials observed as bright angular inclusions; EDX indicated high Ca, Si, Al, and Mg with low Na content.

- Pore Networks: SCK GP exhibited smaller, more uniformly distributed pores, whereas Aachen GP displayed larger, irregular, and often interconnected pores, aligning with its initially higher porosity.

- AAM Gel Matrix: SCK GP developed a more homogeneous gel structure with Si/Al ratios typically between 1.5 and 3.0, while Aachen GP showed a heterogeneous gel matrix with visible variations in density and composition.

3.4. Microstructural and Phase Development

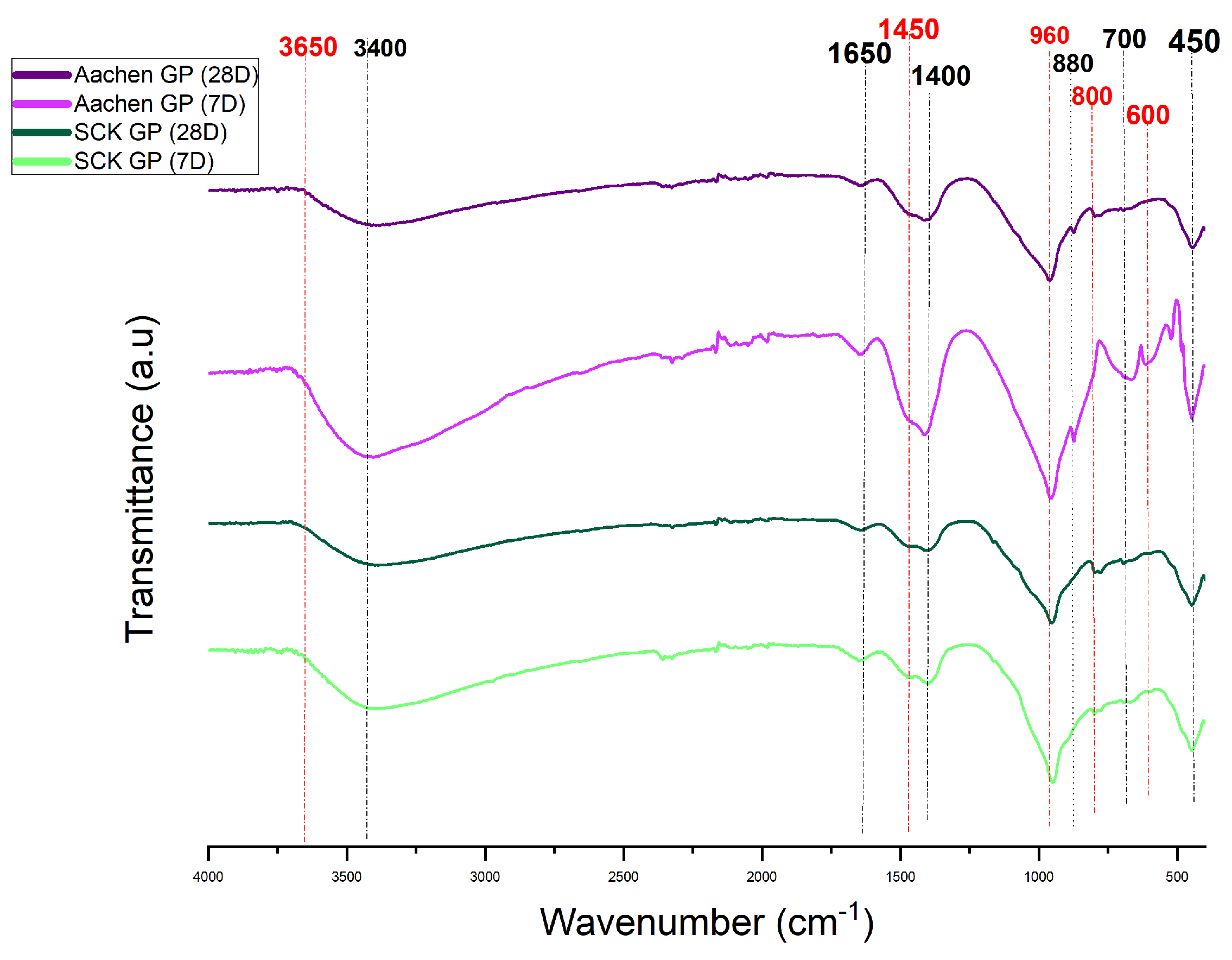

3.4.1. Gel Structure: Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) Analysis

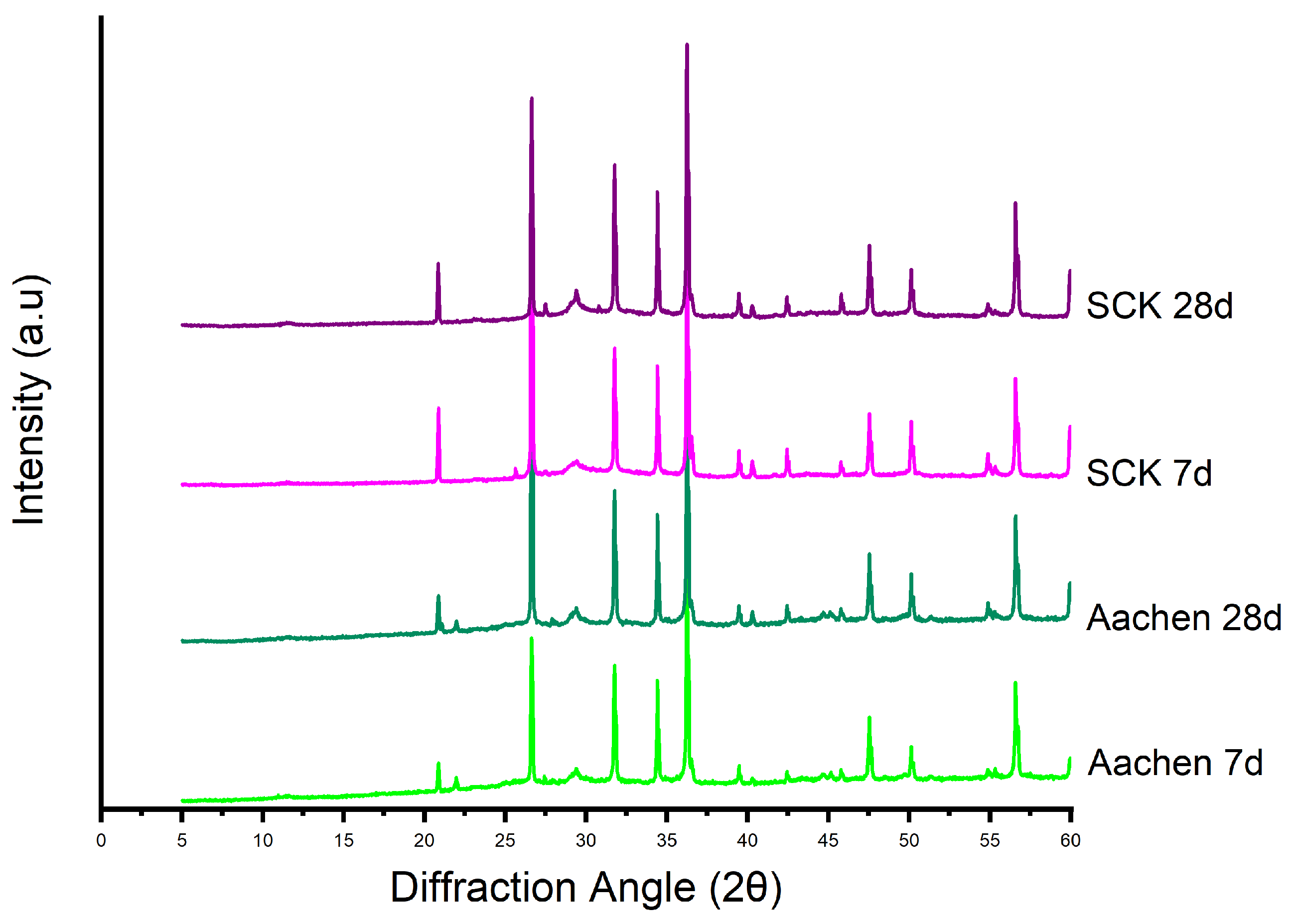

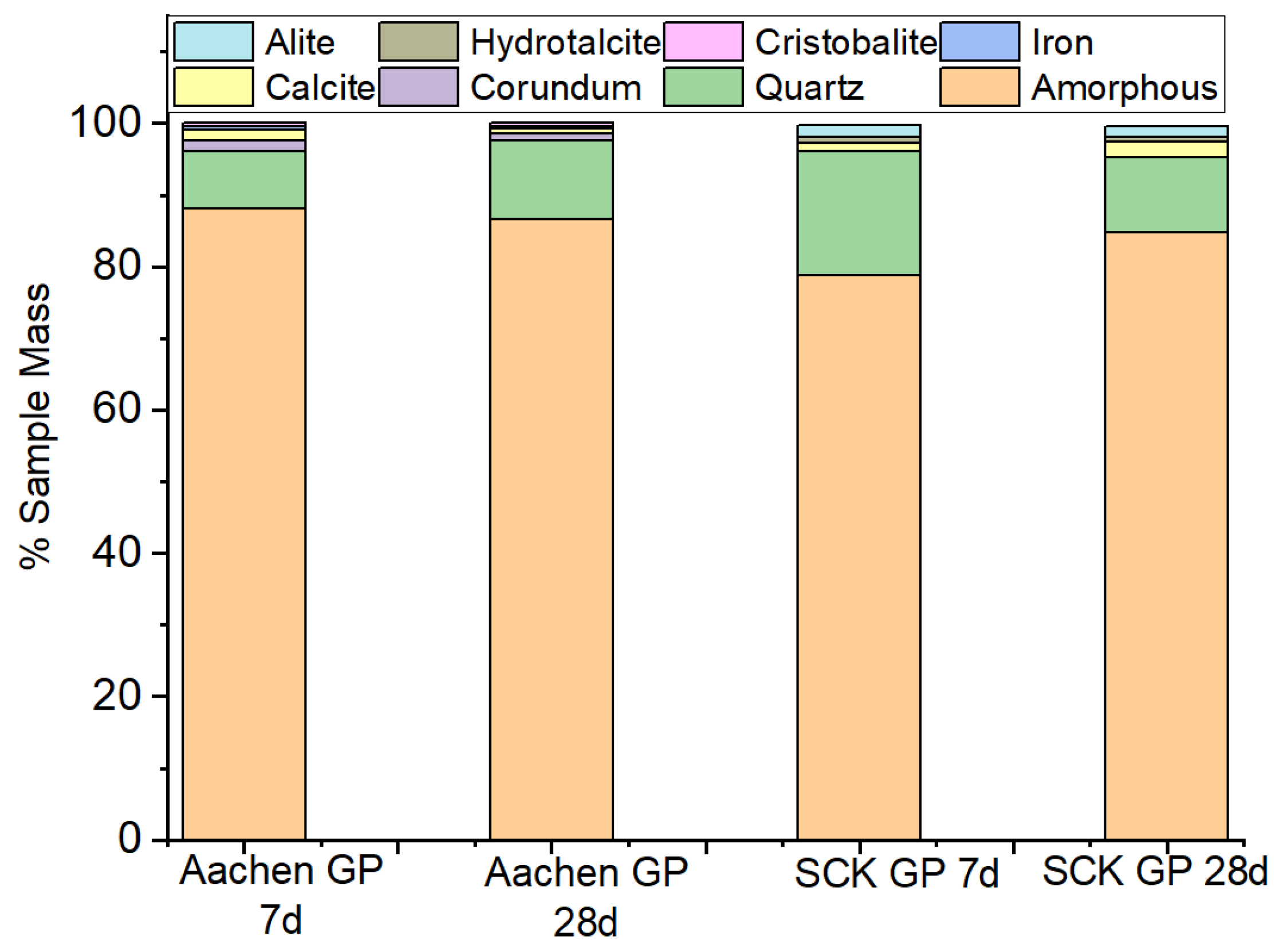

3.4.2. Phase Evolution and Crystalline Interference: X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

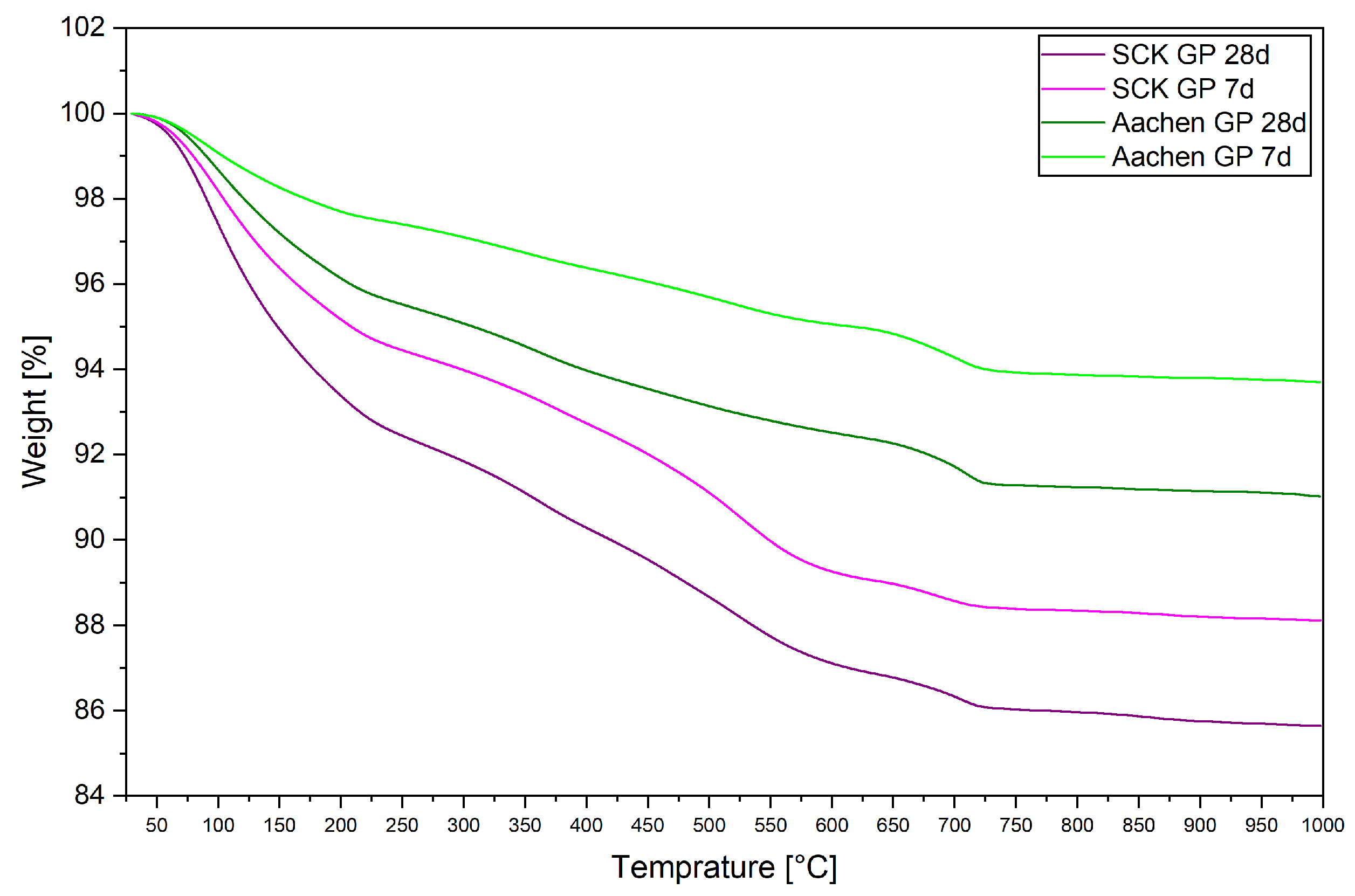

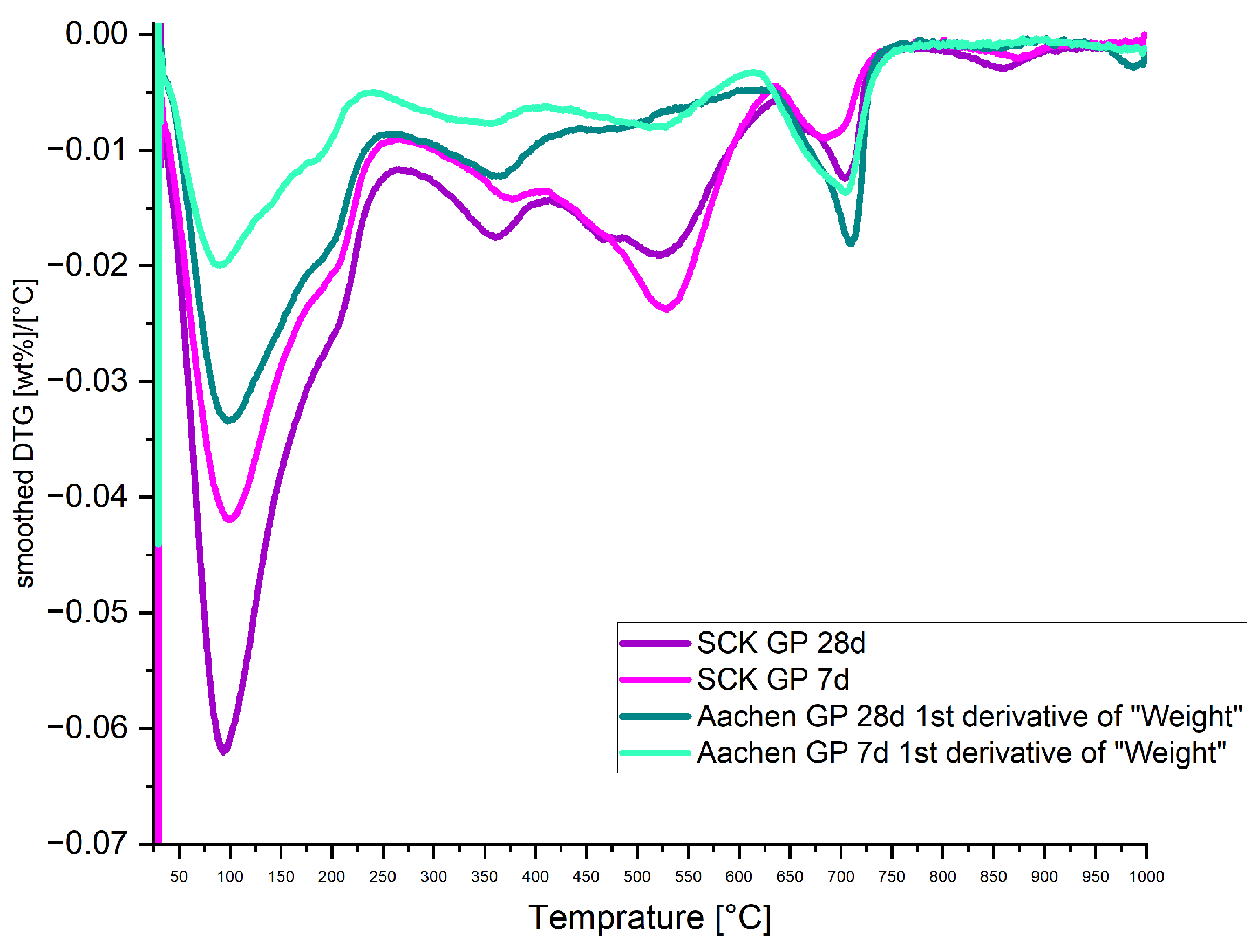

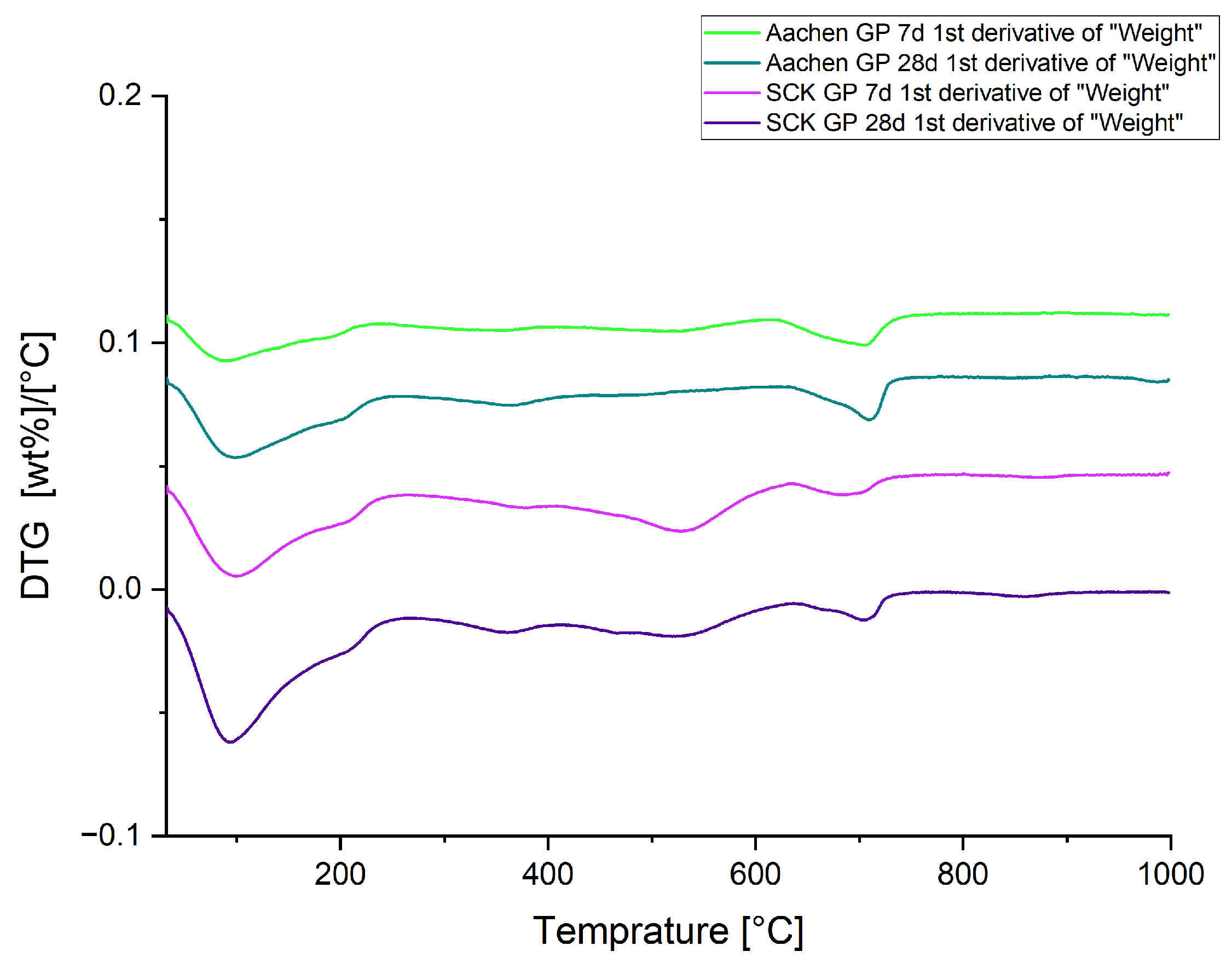

3.5. Thermal Stability and Gel Hydration: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI Use

References

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Status and Trends in Spent Fuel and Radioactive Waste Management. Technical Report NW-T-1.14 (Rev. 1), International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria, 2022. Available from IAEA Publications.

- Ojovan, M.I.; Steinmetz, H.J. Approaches to Disposal of Nuclear Waste. Energies 2022, 15, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic Polymeric New Materials. Journal of Thermal Analysis 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, T.B.; Duguma, A.B.; Bekele, A.M.; Huang, W.; Abegaz, F. Recent Advances in Alternative Cementitious Materials for Nuclear Waste Immobilization: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymer Technology: The Current State of the Art. Journal of Materials Science 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. International Journal of Mineral Processing 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, E. Industrially interesting approaches to “low-CO2” cements. Cement and Concrete Research 2004, 34, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwe, E.; Khatiwada, D.; Gasparatos, A. Life cycle assessment of a cement plant in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2021, 2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, S.; Wiedmann, T.; Castel, A.; de Burgh, J. Hybrid life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from cement, concrete and geopolymer concrete in Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 152, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, B.; Williams, R.; Lay, J.; van Riessen, A.; Corder, G. Costs and carbon emissions for geopolymer pastes in comparison to ordinary Portland cement. Journal of Cleaner Production 2011, 19, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Alkali-activated Materials: State-of-the-Art Report. RILEM Technical Committee 224-AAM 2014, pp. 1–388. [CrossRef]

- Komnitsas, K.; Zaharaki, D. Geopolymerisation: A Review and Prospects for the Minerals Industry. Minerals Engineering 2007, 20, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, B.; Ke, X.; Hussein, O.; Bernal, S.; Provis, J. Incorporation of strontium and calcium in geopolymer gels. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2019, 382, 121015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alouani, S.e.a. Application of geopolymers for treatment of water contaminated with organic and inorganic pollutants: State-of-the-art review. Journal OF Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.e.a. Performance study of ion exchange resins solidification using metakaolin-based geopolymer binder. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2020, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girke, N.; Steinmetz, H.; Bukaemsky, A.; Bosbach, D.; Hermann, E.; Griebel, I. Cementation of Nuclear Graphite using Geopolymers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the NUWCEM 2011, Avignon, France, October 2011; pp. 11–14.

- Frederickx, L.; Mukiza, E.; Phung, Q.T. Leaching of a Cs- and Sr-Rich Waste Stream Immobilized in Alkali-Activated Matrices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.; Palomo, A.; Fernández-Jiménez, A. Alkali activation of fly ashes. Part 1: Effect of curing conditions on the carbonation of the reaction products. Fuel 2005, 84, 2048–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemougna, P.N.; MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Rahier, H.; Melo, U.F.C. The role of iron in the formation of inorganic polymers (geopolymers) from volcanic ash: A 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy study. Journal of Materials Science 2013, 48, 5280–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.L.; Kriven, W.M. Formation of an Iron-based Inorganic Polymer (Geopolymer). Journal of Ceramic Engineering and Science Proceedings 2009, 30, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.; Rose, V.; Provis, J. The fate of iron in blast furnace slag particles during alkali-activation. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2014, 146, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Lothenbach, B.; Geng, G.; Grolimund, D.; Sanchez, D.F.; Fakra, S.C.; Dähn, R.; Wehrli, B.; Wieland, E. Iron Speciation in Blast Furnace Slag Cements. Cement and Concrete Research 2021, 140, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemougna, P.N.; Wang, K.t.; Tang, Q.; Cui, X.m. Study on the Development of Inorganic Polymers from Red Mud and Slag System: Application in Mortar and Lightweight Materials. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 156, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Rostovsky, I.; Nugteren, H. Geopolymer Materials Based on Natural Zeolite. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2017, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomar, V.; Yliniemi, J.; Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Illikainen, M. An overview of the utilisation of Fe-rich residues in alkali-activated binders: Mechanical properties and state of iron. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 330, 129900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisei, S.; Pontikes, Y.; Angelopoulos, G.N.; Snellings, R.; Dierckx, P.; Vandewalle, L. Synthesis of inorganic polymers made of fayalite slag and fly ash and their properties as construction materials. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 205–206, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komnitsas, K.; Zaharaki, D.; Perdikatsis, V. Effect of synthesis parameters on the compressive strength of low-calcium ferronickel slag inorganic polymers. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 161, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacops, E.; Phung, Q.T.; Frederickx, L.; De Schutter, G.; Verhoef, E.; Maes, N. Diffusive Transport of Dissolved Gases in Potential Concretes for Nuclear Waste Disposal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10007–10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, Q.T.; Maes, N.; Jacques, D.; De Schutter, G.; Ye, G. Study of the Time-dependent Behaviour of the Concrete Buffer of a Radioactive Waste Disposal. Construction and Building Materials 2016, pp. 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Phung, Q.T.; Maes, N.; Jacques, D.; Bruneel, E.; Van Driessche, I.; Ye, G.; De Schutter, G. Effect of Limestone Fillers on Microstructure and Permeability Due to Carbonation of Cement Pastes Under Controlled CO2 Pressure Conditions. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 82, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döbelin, N.; Kleeberg, R. Profex: a graphical user interface for the Rietveld refinement program BGMN. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2015, 48, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beersaerts, G.; Vananroye, A.; Sakellariou, D.; Clasen, C.; Pontikes, Y. Rheology of an alkali-activated Fe-rich slag suspension. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2021, 561, 120747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONDRAF/NIRAS. Waste Plan for the Long-term Management of Conditioned High-level and/or Long-lived Radioactive Waste and Overview of Related Issues. Technical Report NIROND 2011-02 E, Belgian Agency for Radioactive Waste and Enriched Fissile Materials, Avenue des Combattants 107 A, 1470 Genappe, Belgium, 2011.

- Commission on Storage of High-Level Radioactive Waste. Final Report: Responsibility for the Future - Nuclear Waste Management in Germany. Technical report, Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, Germany, 2024.

- Nikolov, A. Alkali-activated geopolymers based on iron-rich slag from copper industry. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2020, Vol. 951, p. 012006. [CrossRef]

- Adediran, A.; Yliniemi, J.; Lemougna, P.N.; Perumal, P.; Illikainen, M. Recycling high volume Fe-rich fayalite slag in blended alkali-activated materials: Effect of ladle and blast furnace slags on the fresh and hardened state properties. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 63, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adediran, A.; Yliniemi, J.; Moukannaa, S.; Ramteke, D.; Perumal, P.; Illikainen, M. Enhancing the thermal stability of alkali-activated Fe-rich fayalite slag-based mortars by incorporating ladle and blast furnace slags: Physical, mechanical and structural changes. Cement and Concrete Research 2023, 166, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemist, A.; ul Amin, N.; Ahmad, H.; Noor, S.; Sultana, S.; Huzaifa, U.; Ahmad, H.; Awwad, F.; Ismail, E. Synthesis and characterization of novel iron-modified geopolymer cement from laterite clay as low energy material. AIP Advances 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomar, V.; Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Illikainen, M. High-temperature performance of slag-based Fe-rich alkali-activated materials. Cement and Concrete Research 2022, 161, 106960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Titorenkova, R.; Velinov, N.; Delcheva, Z. Characterization of a novel geopolymer based on acid-activated fayalite slag from local copper industry. Bulgarian Chemical Communications 2019, 50, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mohebbi, A.; Allahverdi, A. Thermal analysis of alkali-activated materials: A review on gel structures and stability. Thermochimica Acta 2020, 689, 178649. [Google Scholar]

| Chemical Component | BFS (wt.%) | Iron-Rich Slag (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|

| CaO | 39.58 | 0.9 |

| SiO2 | 35.37 | 59.4 |

| MgO | 8.66 | 0.7 |

| Al2O3 | 12.29 | 7.6 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.37 | 24.6 |

| MnO / Mn2O3 | 0.54 | 1.8 |

| K2O | 0.59 | 2.5 |

| TiO2 | – | 0.3 |

| SO3 | 0.09 | 0.9 |

| Na2O | 0.27 | – |

| Na2O equivalent | 0.66 | – |

| Cr | 0.02 | – |

| Cl− | – | – |

| Glass content | 100 | – |

| (CaO + MgO + SiO2) | 83.60 | – |

| (CaO + MgO)/SiO2 | 1.36 | – |

| Component | SCK GP (g) | Aachen GP (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Blast furnace slag | 465.5 | 236.0 |

| Iron-rich slag | – | 236.0 |

| NaOH solution | 55.6 | 60.0 |

| Sodium disilicate | 15.2 | – |

| Additional water | 183.8 | 188.0 |

| Fine sand ( mm) | 280.0 | 280.0 |

| Water-to-binder ratio | 0.45 | 0.475 |

| WAP 7 d (%) | WAP 28 d (%) | WP (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aachen GP | 37.4 (n = 2) | 38.4 (n = 2) | (n = 1) |

| SCK GP | 34.4 (n = 2) | 35.5 (n = 3) | (n = 1) |

| Sample | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Width (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aachen GP 7 d | 8.2 | 0.06 | 35 |

| Aachen GP 28 d | 12.4 | 0.09 | 32 |

| SCK GP 7 d | 4.1 | 0.02 | 33 |

| SCK GP 28 d | 6.8 | 0.02 | 31 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| ∼3400 | O–H stretching (physically bound water and hydroxyl groups) |

| 1650 | H–O–H bending (molecular water) |

| 1475 | C–O stretching (carbonate group; shifted from 1410 cm−1 at 7 days) |

| 960 | Si–O–T asymmetric stretching (aluminosilicate gel network) |

| 900–1000 | Broad Si–O–T envelope (incomplete or evolving network) |

| 880 | Si–O–T shoulder (delayed network polymerization; possible Fe substitution) |

| 790–650 | Si–O–Si and O–Si–O bending vibrations |

| 700 | Si–O–Si symmetric bending (framework deformation) |

| 670, 514 | Tentative Si–O–Fe linkages (Fe incorporation; overlapping with Al/Si modes in NaOH-activated systems) |

| 625–830 | Overlapping Si–O, Fe–O, and fayalite-type lattice vibrations |

| 560 | Fe–O stretching (possibly shifted from 550 cm−1; weak in NaOH-activated matrices) |

| 400–800 | Complex Fe- and Si-related overlapping bands (low polymerization, spectral broadening) |

| Sample | Curing Age | Bound Water (%) | Total Mass Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCK GP | 7 days | 7.9 | 11.2 |

| SCK GP | 28 days | 9.1 | 13.4 |

| Aachen GP | 7 days | 3.04 | 5.9 |

| Aachen GP | 28 days | 4.6 | 8.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).