1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a strategic priority in logistics and supply chain management (SCM), reshaping organizational strategies and competitiveness worldwide [

1,

2]. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework emphasizes the integration of environmental, social, and economic dimensions to achieve long-term performance [

3]. Within this paradigm, green logistics practices (GLPs)—including eco-efficient transportation, energy-saving warehousing, packaging optimization, and reverse logistics—have emerged as critical levers for reducing environmental impacts while improving operational efficiency [

4,

5].

Globally, the logistics sector contributes nearly 11% of total greenhouse gas emissions and accounts for approximately 8% of global GDP [

6]. These figures highlight the urgency of adopting sustainable logistics practices and have prompted both policymakers and organizations to accelerate the transition toward greener operations. While the environmental dimension has been extensively investigated in developed economies, the social dimension of sustainability—covering employee well-being, workplace safety, gender equality, and stakeholder engagement—has received comparatively less empirical attention [

7,

8]. Yet recent evidence demonstrates that social performance (SP) can enhance employee retention, stimulate innovation, and build trust with supply chain partners, thereby strengthening organizational competitiveness [

9].

Despite these global developments, empirical research remains concentrated in Europe, North America, and East Asia, leaving emerging economies underrepresented in sustainability-oriented logistics studies [

10,

11]. Morocco presents a particularly relevant case to address this gap. As a strategic Euro-Mediterranean hub, the country ranks third in Africa on the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index [

12] and has invested heavily in infrastructure modernization through initiatives such as the Plan National de la Logistique and the Green Logistics Strategy [

13]. Logistics activities account for approximately 8.7% of Morocco’s GDP and are projected to expand steadily due to intensifying EU–Morocco trade flows and evolving sustainability requirements [

14]. Moroccan logistics service providers (LSPs), however, face mounting pressures from the European Green Deal [

15], global buyers, and domestic regulations to align with international sustainability standards.

Yet limited empirical evidence exists on how Moroccan LSPs adopt GLPs and SP practices, and how these dimensions jointly influence organizational performance (OP). Addressing this gap, the present study examines the interplay between GLPs, SP, and OP within Morocco’s logistics sector. Specifically, it aims to:

Assess the direct effect of GLPs on OP.

Evaluate the impact of SP on OP.

Investigate whether SP mediates the relationship between GLPs and OP, highlighting potential complementarities.

Grounded in the Triple Bottom Line framework [

3] and informed by the Resource-Based View (RBV) [

16], this study employs a quantitative research design based on survey data collected from 210 managers and professionals in Moroccan logistics firms. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), the findings reveal that both GLPs and SP are significant drivers of OP, with SP playing a pivotal mediating role.

By providing rare, context-specific evidence from Morocco, this research contributes to the literature on sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies. It also offers practical insights for LSPs and policymakers seeking to integrate environmental and social sustainability dimensions into competitive strategies.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Sustainability in logistics and supply chain management (SCM) has emerged as a central research theme, driven by increasing regulatory pressures, stakeholder expectations, and global environmental challenges [

1,

2]. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework conceptualizes sustainability as the integration of environmental, social, and economic dimensions to achieve long-term value creation [

3]. Within this paradigm, green logistics practices (GLPs) and social performance (SP) have been identified as critical drivers of organizational performance (OP), particularly in logistics-intensive sectors [

4,

5,

7,

8].

2.1. Green Logistics Practices and Organizational Performance

GLPs involve strategies designed to minimize the ecological footprint of logistics operations while improving efficiency and competitiveness [

4,

5]. They encompass eco-efficient transportation, packaging optimization, reverse logistics, circular economy initiatives, and energy-efficient warehousing. Empirical evidence shows that GLPs can enhance OP by reducing operational costs, improving service quality, and strengthening market positioning [

17,

18,

19].

However, recent research highlights that the magnitude of GLPs’ impact on OP remains heterogeneous across contexts. Kamewor et al. [

26], through a bibliometric and systematic review of 45 studies published between 2011 and 2024, reveal that differences in conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement explain much of this variation. Their findings distinguish three main perspectives for measuring GLPs:

Multi-dimensional approaches integrating environmental, social, and economic indicators.

Bi-dimensional approaches focusing primarily on environmental and economic outcomes.

Uni-dimensional approaches considering only environmental aspects.

Additionally, Kamewor et al. [

26] apply the Antecedent–Decision–Outcome (ADO) framework to identify 14 internal and external drivers of GLP adoption, including top management commitment, institutional pressures, technological readiness, stakeholder demands, financial capacity, and environmental regulations. The framework also links GLPs to five outcome categories: business performance, supply chain sustainability, supply chain performance, logistics performance, and environmental performance.

Despite these positive associations, the bibliometric evidence shows that 91% of studies use cross-sectional quantitative designs, limiting causal inferences and leaving room for deeper investigation in emerging economies [

26]. In Morocco, where logistics infrastructure and regulatory frameworks are still evolving [

12,

13], the role of GLPs in driving OP remains underexplored and has only recently begun to be addressed in empirical research [

27].

H1. Green logistics practices positively influence the organizational performance of logistics firms in Morocco.

In line with Zhu and Sarkis [

4] and Hasanspahić et al. [

5], we operationalize Green Logistics Practices (GLPs) through five dimensions:

GLP1: packaging optimization,

GLP2: energy-efficient warehousing,

GLP3: reverse logistics practices,

GLP4: transportation route optimization, and

GLP5: use of recyclable/eco-friendly packaging materials.

These practices reflect both efficiency and environmental responsibility, which prior studies have associated with cost reduction and competitiveness.

2.2. Social Performance and Organizational Performance

The social dimension of sustainability focuses on a firm’s responsibilities toward employees, local communities, and broader stakeholders. SP involves workplace safety, employee training, gender equality, diversity management, and stakeholder engagement [

7,

8]. Studies demonstrate that SP enhances OP by improving employee retention, fostering innovation, and building trust with global supply chain partners [

9,

17].

Baah et al. [

8] show that socially responsible practices improve both environmental reputation and financial performance, underscoring SP’s strategic value. Moreover, recent studies emphasize that in emerging economies, SP is increasingly viewed as a compliance-driven necessity rather than a voluntary initiative, as global buyers impose strict social and environmental requirements [

10,

14].

For Moroccan logistics service providers (LSPs), integrating SP practices has become vital to maintaining competitiveness within Euro-Mediterranean trade corridors, where alignment with international standards increasingly determines access to global markets [

15,

20].

H2. Social performance positively influences the organizational performance of logistics firms in Morocco.

Social Performance (SP) is conceptualized following Mani et al. [

7] and Baah et al. [

8] through four indicators:

SP1: workplace safety and employee health,

SP2: employee training and development,

SP3: promotion of gender equality in logistics operations, and

SP4: engagement with local communities and stakeholders.

These elements capture the firm’s ability to meet social sustainability expectations, which the literature links to innovation, trust, and competitive advantage.

2.3. Integrating Environmental and Social Dimensions

While GLPs and SP have often been studied independently, an integrated approach offers synergistic benefits. GLPs reduce environmental impacts and improve operational efficiency, while SP fosters employee engagement and stakeholder legitimacy, accelerating sustainability transitions [

24,

25].

The bibliometric review by Kamewor et al. [

26] identifies a critical research gap: few studies examine how GLPs and SP jointly influence OP, despite increasing calls for integrated ESG strategies. This gap is especially relevant for Morocco, where regulatory pressures such as the European Green Deal [

15] and national sustainability initiatives [

13] push firms toward holistic sustainability frameworks. Addressing this gap can improve firms’ competitiveness and compliance in Euro-Mediterranean logistics chains [

20].

H3. The joint implementation of green logistics practices and social performance positively influences the organizational performance of logistics firms in Morocco.

Organizational Performance (OP), adapted from Rao and Holt [

19] and Green et al. [

20], is reflected in four items:

OP1: improved customer satisfaction,

OP2: higher operational efficiency,

OP3: enhanced logistics performance relative to competitors, and

OP4: improved financial performance.

These dimensions align with the TBL framework by capturing the broader economic impact of sustainability initiatives.

3. Methodology:

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to examine the relationships between green logistics practices (GLPs), social performance (SP), and organizational performance (OP) in Moroccan logistics service providers (LSPs). A structured questionnaire was developed based on validated scales from prior studies [

4,

7,

8,

17]. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed as an analytical method. PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for exploratory studies in emerging contexts, for theory development, and when working with complex models and relatively small to medium sample sizes [

28].

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The target population consisted of professionals and managers working in LSPs operating in Morocco, including firms engaged in freight forwarding, warehousing, distribution, and multimodal transport.

Sampling technique: A purposive sampling approach was adopted to ensure respondents had relevant managerial or decision-making responsibilities. The sample included managers, directors, and operations staff, ensuring representation of different hierarchical levels. Firms of varying sizes were included, from small operators to large multinational subsidiaries, reflecting the diversity of Morocco’s logistics sector.

Data collection: A structured online questionnaire was distributed between January and March 2025 through professional networks, industry associations, and LinkedIn groups related to Moroccan logistics.

Sample size: The target population consisted of Moroccan LSPs operating in transport, warehousing, freight forwarding, and supply chain services. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed between January and March 2025 through professional associations, industry networks, and direct contacts. After data screening, 210 valid responses were retained, yielding a response rate of 70%. While this rate is comparable to prior logistics and sustainability studies, the 30% non-response rate introduces the potential for bias. Following Armstrong and Overton [29], early and late respondents were compared on key demographic variables, with no significant differences observed. This suggests that non-response bias is unlikely to have materially affected the results, although the possibility cannot be fully excluded.

Sample Adequacy: Following the 10-times rule [

21], a minimum of 30 observations was required (based on the highest number of predictors pointing to a latent construct, which is three in this study). With N = 210, the sample size far exceeded this threshold, ensuring adequate statistical power.

Respondent Profile: Participants included: Logistics managers (42%), Operations officers (27%), Supply chain analysts (18%) and Administrative staff (13%). This diversity offers a multi-perspective view of sustainability practices across Moroccan logistics firms.

3.3. Measurement of Constructs

To operationalize the constructs, we adopted measurement items from prior validated studies. Green Logistics Practices (GLPs) were adapted from Zhu and Sarkis [

4] and Hasanspahić et al. [

17]. Social Performance (SP) was measured following Mani et al. [

7] and Baah et al. [

8]. Organizational Performance (OP) was drawn from Rao and Holt [

18] and Green et al. [

19]. For clarity,

Table 1 presents the constructs, their corresponding measurement codes (GLP1–5, SP1–4, OP1–4), and example items. A five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree was applied.

Before full deployment, a pilot test was conducted with 20 logistics professionals to ensure content clarity and contextual relevance. Minor adjustments were made based on expert feedback.

3.5. Data Screening and Preparation

Prior to the analysis, the dataset underwent comprehensive screening:

Tests of skewness and kurtosis confirmed deviations from normality, further justifying the choice of PLS-SEM over CB-SEM.

3.6. Data Analysis Strategy

The study followed the two-step PLS-SEM procedure recommended by Hair et al. [

28].

Data analysis was performed using SmartPLS4. The PLS algorithm was used to estimate path coefficients, loadings, and reliability measures.

The measurement model was evaluated through indicator reliability, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios). The structural model was assessed using path coefficients, effect sizes (f2), predictive relevance (Q2), R2 values, and model fit indices such as SRMR.:

Step 1 — Measurement Model Evaluation

Indicator reliability: Outer loadings > 0.70.

Internal consistency reliability: Cronbach’s α and Composite Reliability (CR) ≥ 0.70.

Convergent validity: Average Variance Extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.50.

Discriminant validity: Assessed via Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios (< 0.85).

Step 2 — Structural Model Evaluation

Bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples was conducted to assess the significance of path coefficients, indirect effects, and mediation analysis.

Explained variance (R2): Evaluated for endogenous constructs.

Effect sizes (f2): Classified as small (≥ 0.02), medium (≥ 0.15), or large (≥ 0.35).

Predictive relevance (Q2): Positive Q2 values confirmed predictive power.

Model fit: Assessed via Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), with thresholds ≤ 0.08 indicating acceptable fit [

26].

4. Results

This section presents the results of the PLS-SEM analysis conducted using SmartPLS 4.0. Following the recommended two-step procedure [

26], we first assess the measurement model for reliability and validity before evaluating the structural model to test the study’s hypotheses.

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement model was assessed in terms of indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.1.1. Indicator Reliability and Internal Consistency

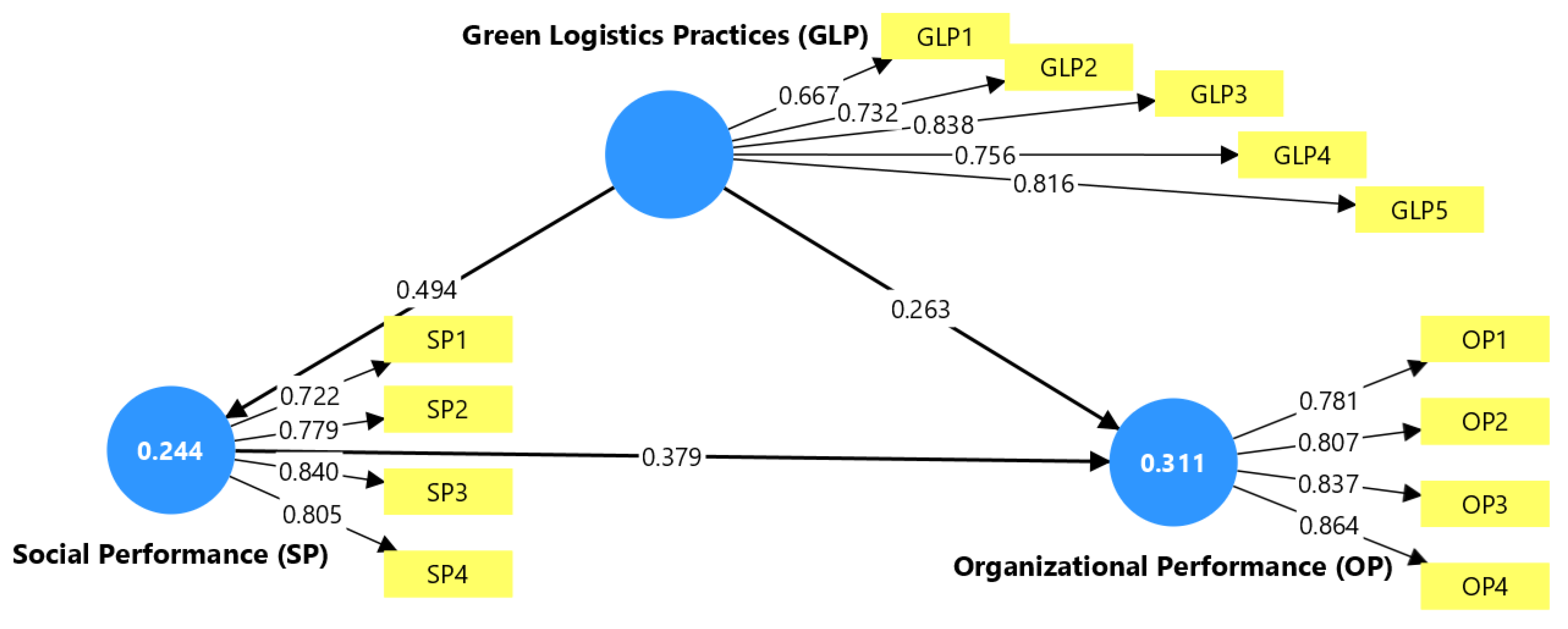

All item loadings exceeded the threshold of 0.70, except for GLP1 (0.667), which was retained due to its theoretical relevance [

4,

5]. Cronbach’s α and Composite Reliability (CR) for all constructs surpassed the recommended 0.70 benchmark, confirming reliability.

All indicator loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, except for GLP1 (0.667). Although slightly below the cut-off, GLP1 was retained due to its theoretical importance in capturing packaging optimization practices. Its indicator reliability (0.445) remained acceptable for exploratory research, and cross-loading analysis confirmed that GLP1 loaded higher on its intended construct than any other. To ensure robustness, the model was re-estimated excluding GLP1, and no substantive differences were observed in composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), or structural path coefficients. Consequently, GLP1 was retained in the final model.

All constructs demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.70, CR values above 0.70, and AVEs above 0.50 [

27]. Importantly, no measurement items were eliminated during the refinement process, confirming that the final structure reflects the original scales.

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity of constructs.

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity of constructs.

| Construct |

Item |

Outer Loading |

Cronbach’s α |

CR |

AVE |

| GLPs |

GLP1 |

0.667 |

0.822 |

0.875 |

0.584 |

| GLP2 |

0.732 |

|

|

|

| GLP3 |

0.838 |

|

|

|

| GLP4 |

0.756 |

|

|

|

| GLP5 |

0.816 |

|

|

|

| SP |

SP1 |

0.722 |

0.796 |

0.867 |

0.621 |

| SP2 |

0.779 |

|

|

|

| SP3 |

0.840 |

|

|

|

| SP4 |

0.805 |

|

|

|

| OP |

OP1 |

0.781 |

0.841 |

0.893 |

0.677 |

| OP2 |

0.807 |

|

|

|

| OP3 |

0.837 |

|

|

|

| OP4 |

0.864 |

|

|

|

4.1.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the HTMT ratio.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

| Construct |

GLPs |

SP |

OP |

| GLPs |

0.764 |

|

|

| SP |

0.494 |

0.788 |

|

| OP |

0.450 |

0.509 |

0.823 |

Convergent validity was established since all standardized loadings were above 0.60 and AVEs exceeded 0.50. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlations with other constructs, confirming discriminant validity.

Table 4 presents the HTMT values. All ratios were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, further supporting discriminant validity.

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

The structural model was assessed through path coefficients (β), t-values, p-values, effect sizes (f2), explained variance (R2), and predictive relevance (Q2).

4.2.1. Hypotheses Testing

Table 5.

Structural model results.

Table 5.

Structural model results.

| Hypothesis |

Path |

Β |

t-value |

p-value |

f2

|

Result |

| H1 |

GLPs → OP |

0.263 |

4.322 |

<0.001 |

0.076 |

Supported |

| H2 |

SP → OP |

0.379 |

6.366 |

<0.001 |

0.158 |

Supported |

| H3 |

GLPs → SP |

0.494 |

10.032 |

<0.001 |

0.322 |

Supported |

4.2.2. Explained Variance and Predictive Relevance

Table 6.

Coefficients of determination (R2) and predictive relevance (Q2).

Table 6.

Coefficients of determination (R2) and predictive relevance (Q2).

| Endogenous Construct |

R2

|

Q2

|

| SP |

0.244 |

0.096 |

| OP |

0.311 |

0.142 |

GLPs and SP jointly explain 31.1% of the variance in OP and 24.4% of the variance in SP.

Positive Q2 values indicate that the model has strong predictive relevance.

4.3. Mediation Analysis

The indirect effect of GLPs → SP → OP was tested using bootstrapping:

Indirect effect: β = 0.187, t = 5.65, p < 0.001.

Since the direct effect (GLPs → OP) remained significant, SP was found to partially mediate the relationship between GLPs and OP.

4.4. Procedural Remedies for Common Method Bias

Given the reliance on self-reported data, procedural remedies were applied to mitigate common method bias (CMB). These included ensuring respondent anonymity, assuring confidentiality, and randomizing item order in the questionnaire. Harman’s single-factor test showed that no single factor accounted for more than 50% of the variance.

To strengthen the analysis, we also calculated full collinearity variance inflation factors (VIFs) in SmartPLS, as recommended by Kock [

30]. All indicator VIFs ranged between 1.42 and 2.07, well below the conservative threshold of 3.3, suggesting that CMB is not a significant concern.

Table 8.

Full Collinearity VIFs for Common Method Bias Assessment.

Table 8.

Full Collinearity VIFs for Common Method Bias Assessment.

| Indicator |

VIF Value |

| GLP1 |

1.44 |

| GLP2 |

1.92 |

| GLP3 |

1.67 |

| GLP4 |

1.85 |

| GLP5 |

1.72 |

| SP1 |

1.42 |

| SP2 |

1.74 |

| SP3 |

1.58 |

| SP4 |

1.66 |

| OP1 |

1.61 |

| OP2 |

1.87 |

| OP3 |

2.07 |

| OP4 |

1.94 |

4.5. Visualization of the Structural Model

The results of the PLS-SEM analysis are illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents standardized path coefficients (β), outer loadings, and R

2 values.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of green logistics practices (GLPs) and social performance (SP) on the organizational performance (OP) of logistics service providers (LSPs) in Morocco, grounded in the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework [

3] and the Resource-Based View (RBV) [

16]. Using PLS-SEM, we examined the direct and indirect relationships among these constructs, providing empirical insights from an underexplored context within the Euro-Mediterranean logistics landscape.

5.1. Green Logistics Practices and Organizational Performance

The findings show that GLPs are positively associated with OP (β = 0.263, p < 0.001), supporting H1. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that eco-efficient transportation, energy-saving warehousing, and reverse logistics improve efficiency, cost control, and reputation [

4,

5,

17].

However, the effect size (f

2 = 0.076) suggests that the contribution of GLPs to OP is modest compared to findings from developed economies [

21,

22]. For example, Liu et al. [

21] found that Chinese firms achieved significant performance gains from GLPs, enabled by advanced infrastructure and strong regulatory enforcement. In Morocco, by contrast, limited logistics infrastructure, fragmented sustainability policies, and compliance-driven adoption appear to reduce the direct benefits of GLPs [

13,

14].

Robustness checks using HTMT ratios and SRMR confirmed the validity of the measurement and structural models, strengthening confidence in these results.

5.2. Social Performance as a Driver of Competitiveness

SP has a stronger association with OP than GLPs (β = 0.379, p < 0.001), supporting H2. This finding aligns with studies highlighting that workplace safety, employee well-being, diversity, and stakeholder engagement are critical for competitiveness [

7,

8,

9].

Baah et al. [

8] showed that socially responsible practices improve both environmental reputation and financial outcomes. In Morocco, SP practices are often driven by compliance requirements from international shippers and institutional actors [

14,

15]. Unlike in many Western contexts where SP may be voluntary, for Moroccan firms it is a strategic necessity. Companies that prioritize SP gain legitimacy and competitive advantage in Euro-Mediterranean trade corridors.

5.3. Complementarity Between Environmental and Social Sustainability

The analysis shows that GLPs significantly enhance SP (β = 0.494, p < 0.001) and that SP partially mediates the relationship between GLPs and OP (indirect effect = 0.187, VAF = 41.5%). This supports H3 and highlights the complementarity of the two dimensions.

These findings extend prior research [

24,

25] by showing that Moroccan firms achieve greater performance benefits when environmental initiatives are integrated with social strategies. Fragmented approaches, focusing only on one dimension, are less effective than holistic ESG adoption.

5.4. Theoretical Implications

This study advances the Triple Bottom Line framework [

3] by demonstrating that environmental and social sustainability practices reinforce each other in improving OP. It also contributes to the Resource-Based View (RBV) [

16], showing that GLPs and SP represent valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources that can strengthen competitiveness in emerging markets.

The results also support stakeholder theory [

24], indicating that legitimacy and long-term performance depend on effective engagement with employees, communities, and institutional actors. By incorporating social aspects alongside environmental practices, this study broadens the scope of sustainability research in logistics.

A key contribution of this study lies in addressing a significant geographic gap in sustainability and logistics research. Existing studies on green logistics and social sustainability overwhelmingly focus on developed economies in Europe, North America, and East Asia, where institutional support and infrastructure are advanced [

21,

22]. By contrast, empirical evidence from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region remains scarce, despite its growing integration into global supply chains. Only a handful of studies have examined GLPs in emerging contexts, and even fewer have incorporated the social dimension alongside environmental practices [

26]. By focusing on Moroccan logistics service providers, this study provides novel insights into how sustainability is adopted in a fragmented institutional environment, thereby enriching both the Triple Bottom Line and Resource-Based View perspectives with evidence from an underrepresented region.

5.5. Practical Implications

From a managerial perspective, this study suggests that Moroccan LSPs should adopt integrated ESG strategies combining GLPs and SP initiatives to enhance OP. While investing in green technologies such as energy-efficient warehouses and low-carbon fleets remains essential, these environmental practices generate greater performance benefits when complemented by employee well-being programs, diversity policies, and stakeholder engagement initiatives.

From a policy standpoint, our findings underscore the importance of institutional support for sustainability adoption. Policymakers should:

These measures can accelerate Morocco’s transition toward integrated sustainability models, strengthening the global competitiveness of its logistics sector.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While research design ensures methodological rigor, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the purposive sampling strategy, though appropriate for targeting respondents with managerial responsibilities, may reduce the generalizability of the findings. To mitigate this concern, the sample included firms of different sizes (SMEs and multinationals) and subsectors (transport, warehousing, freight forwarding, and multimodal services), offering a heterogeneous perspective on Moroccan logistics.

Second, as with most survey-based studies, cross-sectional design restricts causal inference and raises potential concerns of reverse causality—that is, firms with stronger performance may be more likely to adopt green or social practices. Future research could address this limitation by employing longitudinal data to capture temporal dynamics and better establish causality.

Third, although measurement items were adapted from validated scales, contextual differences between Morocco and prior research settings may affect item interpretation. To minimize this risk, a pilot test with 20 professionals was conducted to ensure cultural and sectoral relevance. Fourth, regarding construct reliability, GLP1 showed a slightly lower loading but was retained due to its theoretical importance and acceptable reliability in exploratory research. Finally, while Harman’s single-factor test and full collinearity VIFs indicated that common method bias was not a serious concern, more advanced remedies (e.g., marker variable tests) could be adopted in future studies. Additionally, the possibility of endogeneity—for example, firms with higher performance being more likely to adopt GLPs or SP—cannot be fully excluded. Future longitudinal or instrumental-variable approaches could help address this issue.

Although this study provides valuable insights, it also opens several avenues for future research. First, longitudinal studies should investigate how the impact of GLPs and SP on organizational performance evolves over time. Second, cross-country comparative studies could examine differences in sustainability adoption between Morocco and other Euro-Mediterranean economies. Third, integrating the economic dimension of sustainability into the model would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the triple bottom line framework. Fourth, future work should explore the role of digital transformation (e.g., IoT, blockchain, AI) in enabling effective integration of GLPs and SP. Finally, even though Harman’s single-factor test and full collinearity VIFs indicated that CMB was not a serious concern, future studies could apply more advanced remedies such as marker variable techniques or latent method factors to further validate results.

Overall, this study demonstrates that the organizational performance of Moroccan LSPs is maximized when green logistics practices are integrated with social sustainability strategies. These findings advance sustainability research by highlighting the complementarity of environmental and social dimensions, addressing critical gaps in literature, and offering actionable insights for practitioners and policymakers navigating the sustainability transition.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between green logistics practices (GLPs), social performance (SP), and organizational performance (OP) among logistics service providers in Morocco. By focusing on an underexplored MENA context, the research contributes new empirical evidence to sustainability and logistics studies.

Beyond its managerial and policy implications, the main contribution of this research is to bring evidence from Morocco, a context largely absent from sustainability and logistics studies. By documenting how GLPs and SP interact to influence organizational performance in a MENA country, the study not only extends existing theories to a new setting but also responds to the call for greater inclusivity in global sustainability research.

The findings reveal three key insights. First, GLPs are positively associated with OP, though the effect is modest in the Moroccan context. Second, SP demonstrates a stronger influence on OP, underscoring the importance of workplace well-being, diversity, and community engagement. Third, SP partially mediates the link between GLPs and OP, showing that environmental practices deliver greater benefits when complemented by social initiatives.

Theoretically, the study strengthens the understanding of sustainability by highlighting the complementarity between environmental and social practices. Practically, it suggests that managers should adopt integrated ESG strategies, while policymakers should provide incentives, standards, and training to accelerate sustainable logistics.

Despite its contributions, the study has limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, and its focus on Morocco limits generalizability. Future research should adopt longitudinal approaches, conduct cross-country comparisons, and integrate the economic dimension of sustainability.

Overall, this study demonstrates that sustainability in logistics requires the joint advancement of green and social practices. By investing in both, logistics firms in emerging markets can strengthen competitiveness, resilience, and legitimacy in global supply chains.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full Form |

| SCM |

Supply Chain Management |

| TBL |

Triple Bottom Line |

| GLPs |

Green Logistics Practices |

| SP |

Social Performance |

| OP |

Organizational Performance |

| LSPs |

Logistics Service Providers |

| RBV |

Resource-Based View |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| PLS-SEM |

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| CR |

Composite Reliability |

| AVE |

Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT |

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio |

| SRMR |

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| EU |

European Union |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| EU-GD |

European Green Deal |

| EE |

Emerging Economies |

| AMDL |

Agence Marocaine de Développement de la Logistique (Moroccan Agency for the Development of Logistics) |

References

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanspahić, N.; Kurtagić, S.M.; Zrnić, N. Green logistics in sustainable supply chains: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Freight Centre. GLEC Framework v3: Global Logistics Emissions Council Guidelines; Smart Freight Centre: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://smart-freight-centre-media.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/GLEC_FRAMEWORK_v3_UPDATED_04_12_24.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Mani, V.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. Social sustainability in the supply chain: Analysis of enablers. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Jin, Z.; Tang, L. Building resilience and performance in supply chains through sustainable logistics practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Jackson, G.; Matten, D. Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garti, M.O.; Arif, J.; Jawab, F.; Frichi, Y.; Benbrahim, F.Z. Factors impacting the sustainability of supply chains in Industry 5. 0: An exploratory qualitative study in Morocco. Logistics 2025, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourire, M.; Rouggani, K.; Bouayad Amine, N. Unveiling sustainable supply chain practices and their impact on corporate logistics performance: An exploratory analysis of companies listed on the Moroccan stock exchange. RMd Econ. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2025, 2, e202510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Connecting to Compete 2023: Trade Logistics in an Uncertain Global Economy (Logistics Performance Index); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://lpi.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Agence Marocaine de Développement de la Logistique (AMDL). Stratégie nationale de développement de la compétitivité logistique (2010–2015): Bilan et perspectives; AMDL: Rabat, Morocco, 2016; Available online: https://www.amdl.gov.ma (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- El Imrani, A.; Assabane, A. The impact of logistics capacities on the logistics performance of LSPs: Results of an empirical study. Acta Logistica 2023, 10, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication... The European Green Deal (COM(2019) 640 final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: A systematic literature review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 53, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drejeris, R.; Samuolaitis, D. Sustainable distribution logistics systems: Development and evaluation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Seuring, S. Linking capabilities to green operations strategies: The moderating role of corporate environmental proactivity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V. Integrating ESG practices into logistics operations: Implications for sustainability and competitiveness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6421. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Setyadi, A.; Akbar, Y.K.; Ariana, S.; Pawirosumarto, S. Examining the effect of green logistics and green human resource management on sustainable development organizations: The mediating role of sustainable production. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Modgil, S.; Acharya, P. Green supply chain management practices and their impact on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124597. [Google Scholar]

- Kasmi, M.; Ammi, A.; Bakkali, S. The emergence of sustainable development practices: An overview of green logistics in Morocco. Rev. Int. Chercheur 2024, 5, 19–46. Available online: https://www.revuechercheur.com/index.php/home/article/view/1018 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).