Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

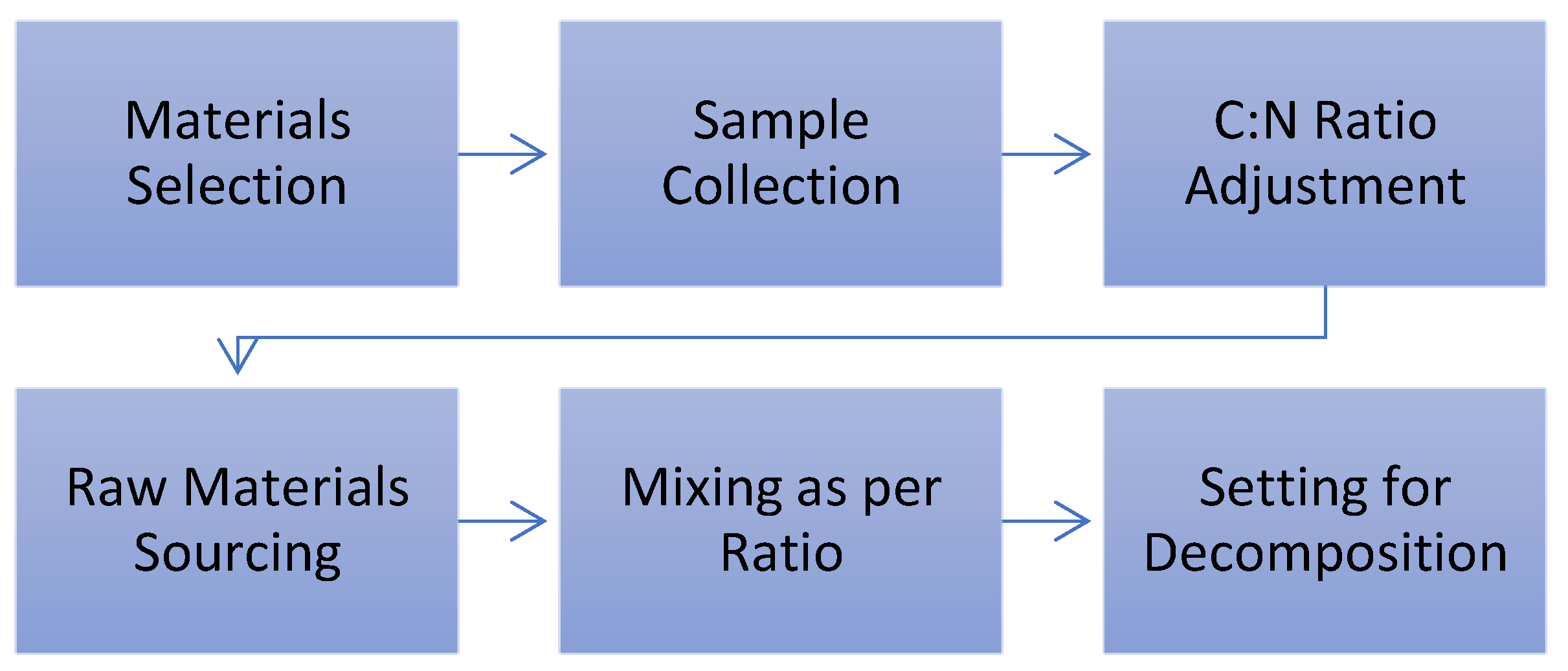

2. Materials and Methods

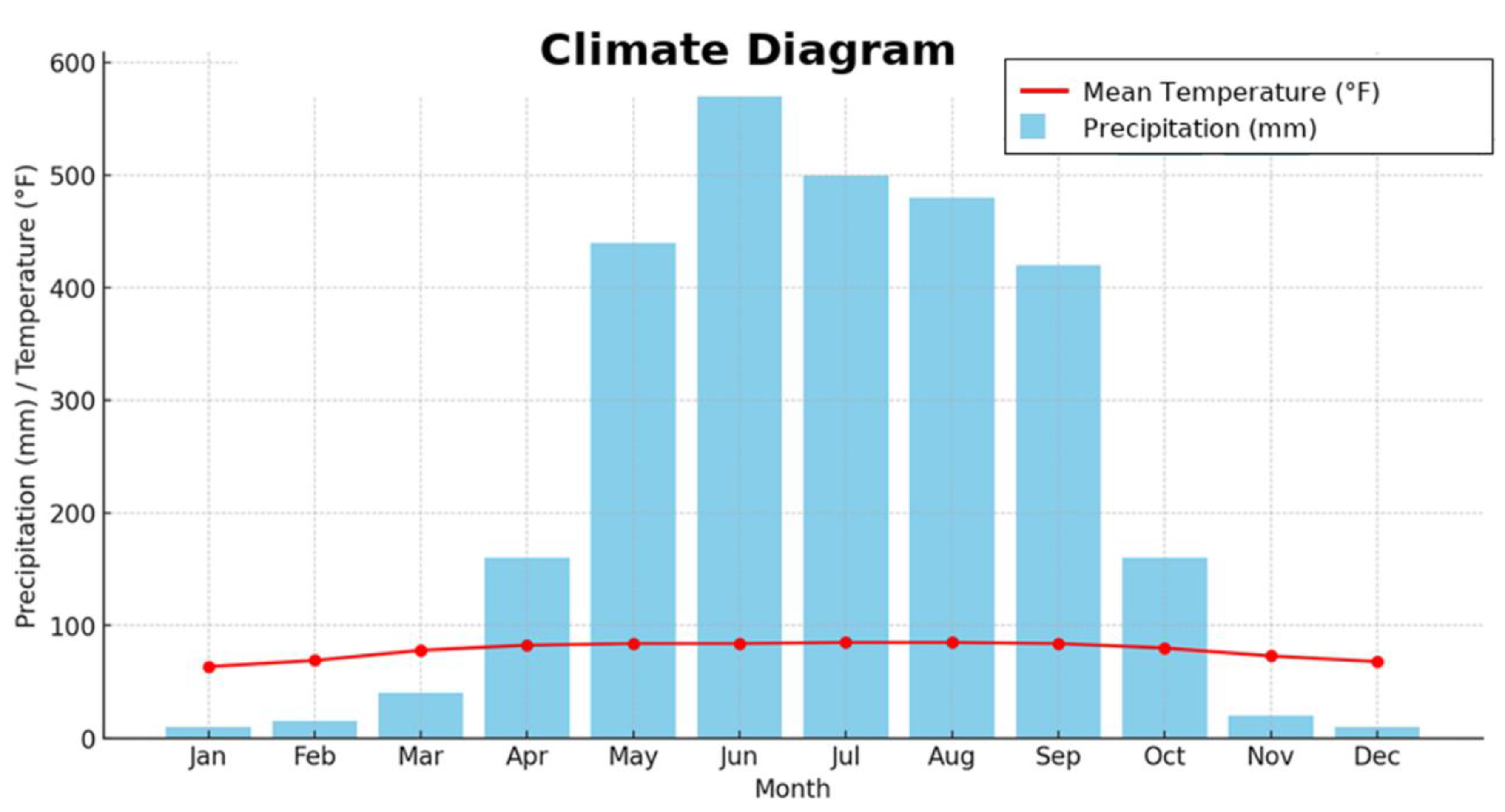

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Materials Used for Composting

2.3. Preparation of the Compost

2.4. Maturity Determination

2.5. Sample Analysis

3. Results

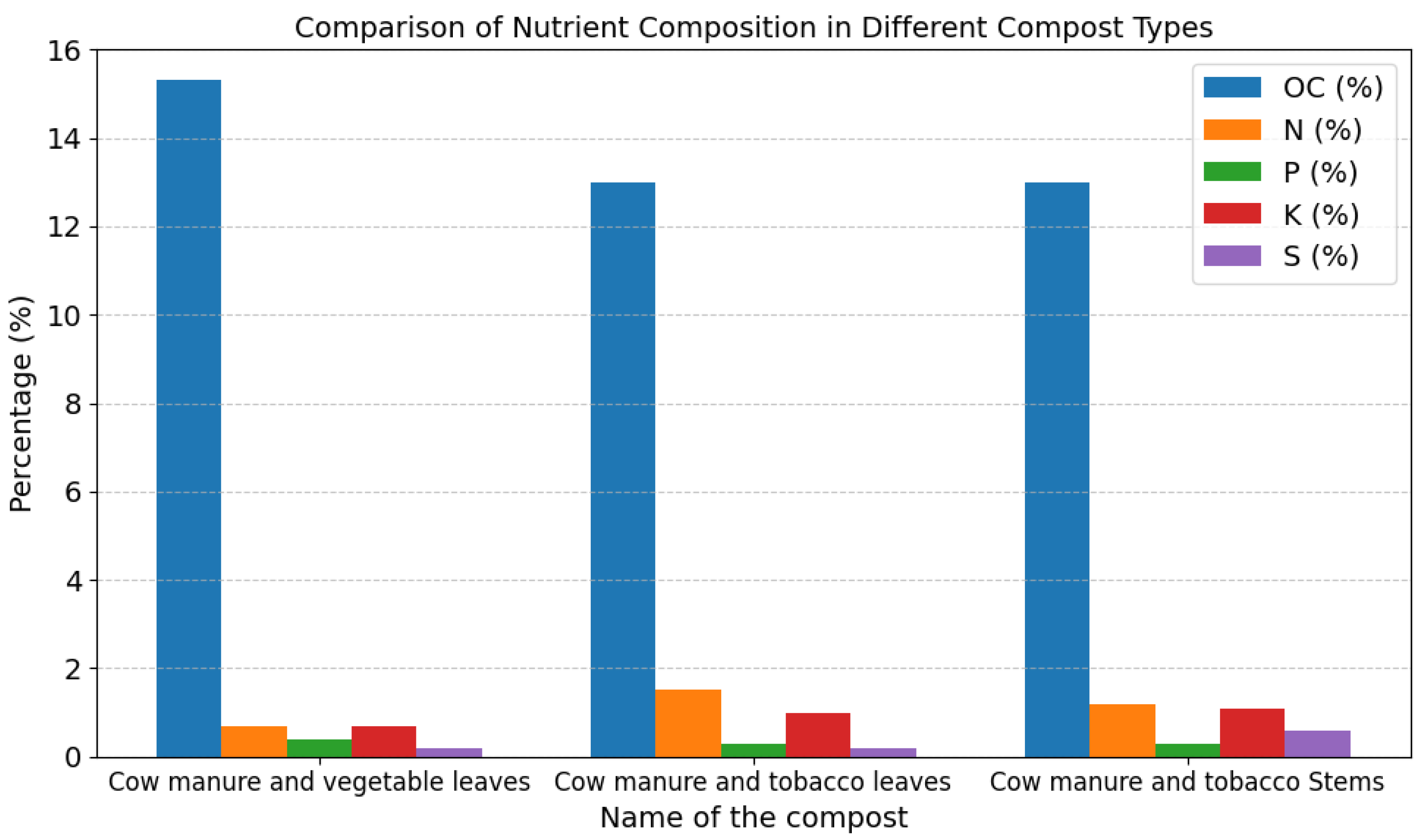

3.1. Nutrient Contents in Conventional Composts

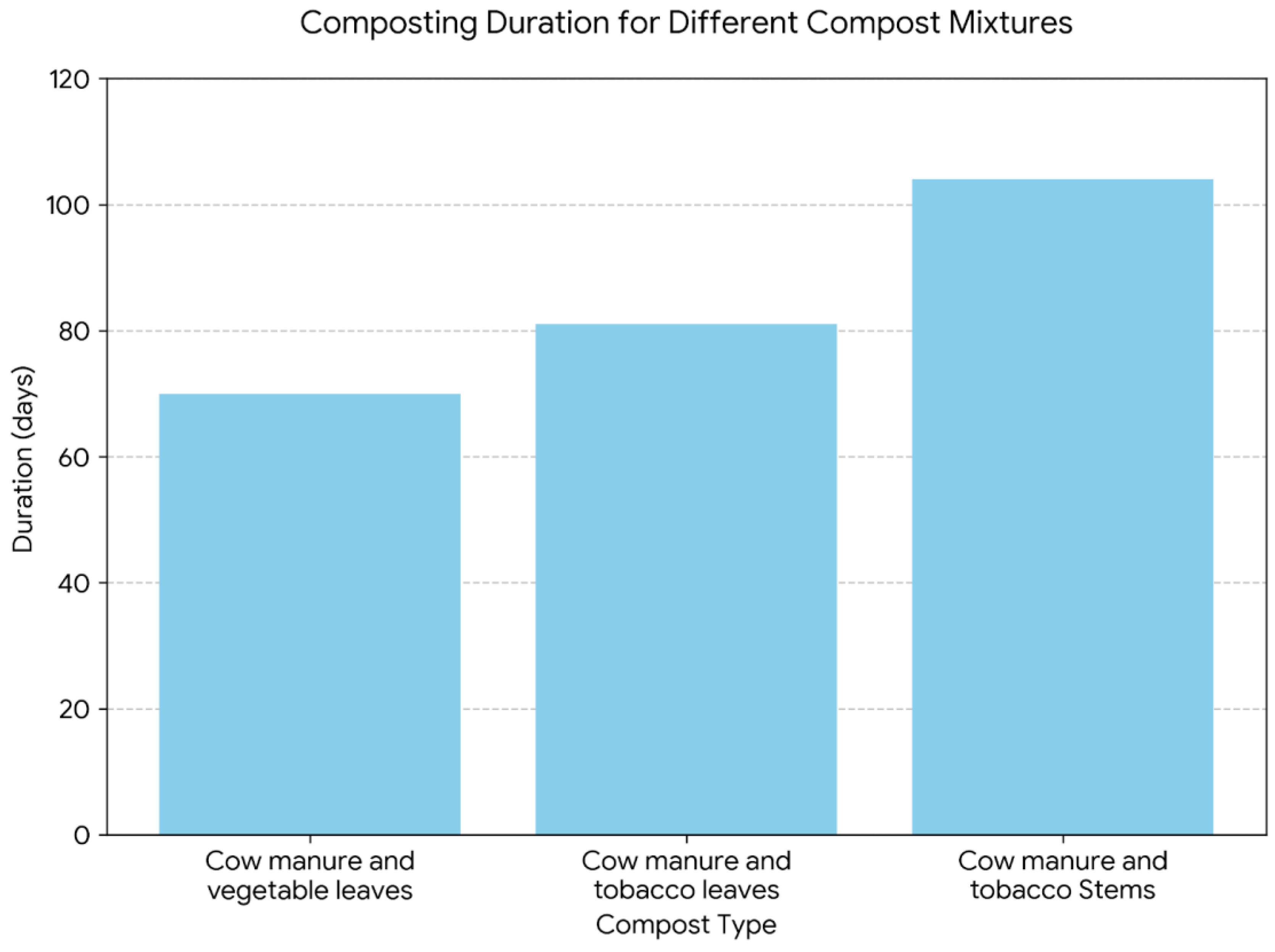

3.2. Duration of Composting

3.3. Nutrient Contents Available in Vermicomposts

| Name of the vermicompost | Organic Carbon (%) |

N (%) |

P (%) |

K (%) |

S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow manure, vegetable leaves, and earthworms | 45.36 | 2.503 | 1.288 | 1.210 | 0.401 |

| Cow manure, tobacco leaves, and earthworms | 40.81 | 2.232 | 1.222 | 1.281 | 0.521 |

| Cow manure, tobacco stems, and earthworms | 38.72 | 2.680 | 1.199 | 1.352 | 0.896 |

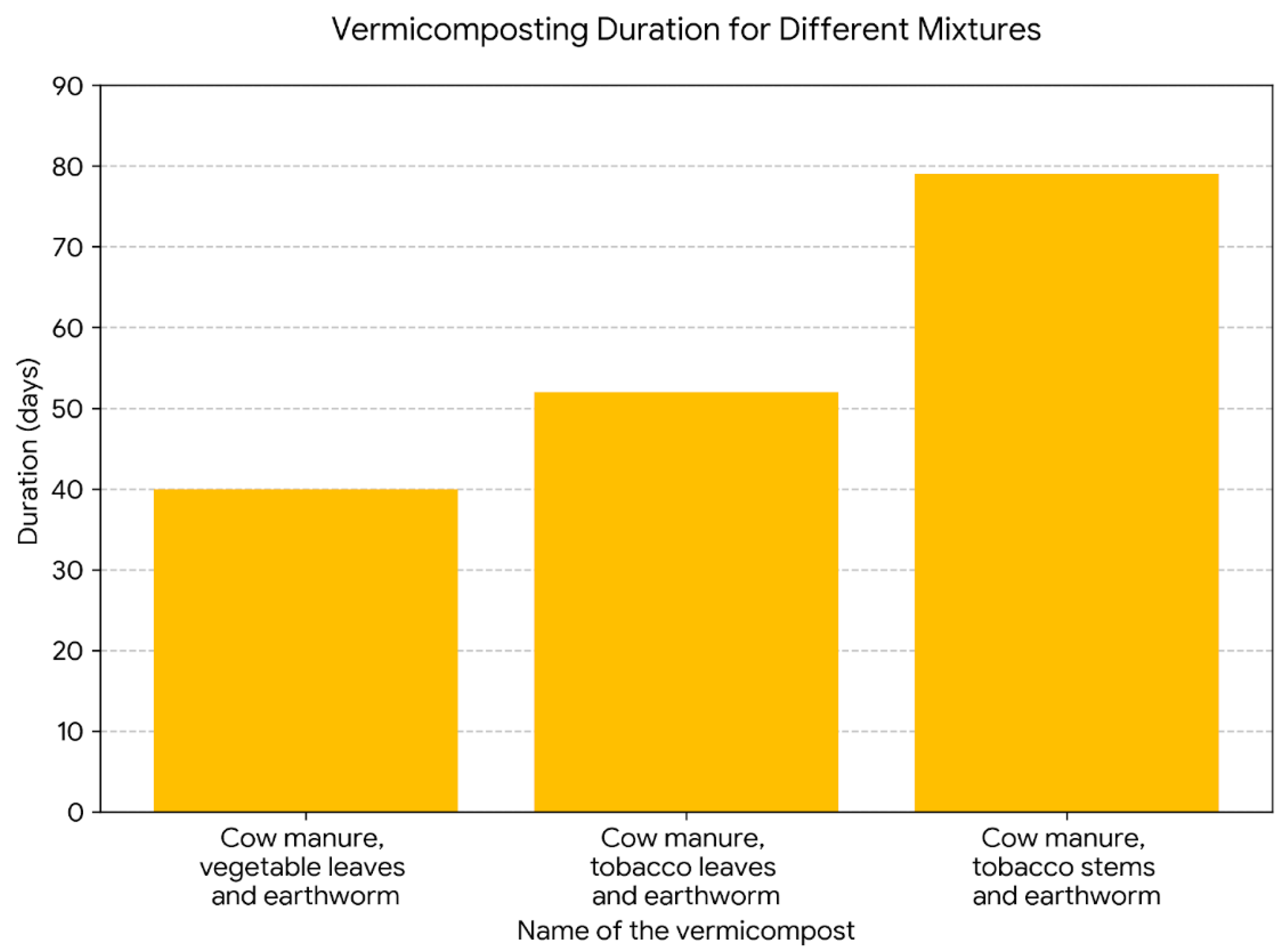

3.4. Duration of Vermicomposting

3.5. Comparison Between Conventional and Vermicomposts

4. Discussion

4.1. Tobacco Waste-Based Compost Performance

4.2. Tobacco Waste Composting Limitations

5. Conclusions

References

- Adediran, J. A., Mnkeni, P. N. S., Mafu, N. C., & Muyima, N. Y. O. (2004). Changes in chemical properties and temperature during the composting of tobacco waste with other organic materials, and effects of resulting composts on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and Spinach (Spinacea oleracea L.). Biological Agriculture and Horticulture, 22(2), 101–119. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S. (2012). Vermicompost, the story of organic gold: A review. Agricultural Sciences, 2012(07), 905–917. [CrossRef]

- Agriculture - Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics-Government of the People\’s Republic of Bangladesh. (n.d.). Retrieved August 8, 2025, from https://bbs.gov.bd/site/page/453af260-6aea-4331-b4a5-7b66fe63ba61/Agriculture.

- Akter, S., & Ahmed, F. (2024). Assessment of Flood Hazards and Vulnerabilities Using Esri Lulc and Fabdem Data: A Case Study of Lalmonirhat Sadar Upazilla, Bangladesh. [CrossRef]

- Altomare, C., Tringovska, I., Altomare, C., Tringovska Maritsa, I., & Lichtfouse, E. (2011). Beneficial Soil Microorganisms, an Ecological Alternative for Soil Fertility Management. 7, 161–214. [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M. S., Olanrewaju, O. S., Babalola, O. O., & Odeyemi, O. (2020). Waste Management through Composting: Challenges and Potentials. Sustainability 2020, Vol. 12, Page 4456, 12(11), 4456. [CrossRef]

- Banožić, M., Aladić, K., Jerković, I., & Jokić, S. (2021). Volatile organic compounds of tobacco leaves versus waste (scrap, dust, and midrib): extraction and optimization. Wiley Online Library, 101(5), 1822–1832. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. A., Singh, J., & Vig, A. P. (2016). Effect on Growth of Earthworm and Chemical Parameters During Vermicomposting of Pressmud Sludge Mixed with Cattle Dung Mixture. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 35, 425–434. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiya, Z. H. (1987). Organic matter status and organic recycling in Bangladesh soils. Resources and Conservation, 13(2–4), 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J. M., & Mulvaney, C. S. (1982). Nitrogen—Total. 595–624. [CrossRef]

- C/N Ratio - CORNELL Composting. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.compost.css.cornell.edu/calc/cn_ratio.html.

- Das, N., Touhidul Islam, M., Symum Islam, M., & M Adham, A. K. (2018). Response of dairy farm’s wastewater irrigation and fertilizer interactions to soil health for maize cultivation in Bangladesh. Asian-Australasian Journal of Bioscience and Biotechnology, 3(1), 33–39. [CrossRef]

- De Castro, F. U.; Aprile, A.; Benedetti, M.; Fanizzi, F. P., Ur Rehman, S., De Castro, F., Aprile, A., Benedetti, M., & Fanizzi, F. P. (2023). Vermicompost: Enhancing Plant Growth and Combating Abiotic and Biotic Stress. Agronomy 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1134, 13(4), 1134. [CrossRef]

- Degefa, K., Tullu, M., & Samuel, N. (2022). Nutrient status of composted and vermicomposted kitchen wastes. International Journal of Soil Science and Agronomy (IJSSA, 9(1), 250–254. www.advancedscholarsjournals.org.

- Di, H., Wang, R., Ren, X., Deng, J., Deng, X., & Bu, G. (2022). Co-composting of fresh tobacco leaves and soil: an exploration on the utilization of fresh tobacco waste in farmland. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(6), 8191–8204. [CrossRef]

- Doan, T. T., Henry-Des-Tureaux, T., Rumpel, C., Janeau, J. L., & Jouquet, P. (2015). Impact of compost, vermicompost, and biochar on soil fertility, maize yield, and soil erosion in Northern Vietnam: A three-year mesocosm experiment. Science of The Total Environment, 514, 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Golder, P. C., Sastry, R. K., & Srinivas, K. (2013). Research priorities in Bangladesh: analysis of crop production trends. SAARC Journal of Agriculture, 11(1), 53–70. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S., Dhull, S. K., & Kapoor, K. K. (2005). Chemical and biological changes during composting of different organic wastes and assessment of compost maturity. Bioresource Technology, 96(14), 1584–1591. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M., Parvin, M., of, S. R.-I. J., & 2015, undefined. (n.d.). Farmer’s profitability of tobacco cultivation at Rangpur district in the socio-economic context of Bangladesh: an empirical analysis. Researchgate.NetMM Hassan, MM Parvin, SI ResmiInternational Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 2015•researchgate.Net. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Md-Hassan-171/publication/274075851_Farmer’s_Profitability_of_Tobacco_Cultivation_at_Rangpur_District_in_the_Socio-Economic_Context_of_Bangladesh_An_Empirical_Analysis/links/5514f4370cf2eda0df34c42b/Farmers-Profitability-of-Tobacco-Cultivation-at-Rangpur-District-in-the-Socio-Economic-Context-of-Bangladesh-An-Empirical-Analysis.pdf.

- Hu, R. S., Wang, J., Li, H., Ni, H., Chen, Y. F., Zhang, Y. W., Xiang, S. P., & Li, H. H. (2015). Simultaneous extraction of nicotine and solanesol from waste tobacco materials by the column chromatographic extraction method and their separation and purification. Separation and Purification Technology, 146, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Di, Q., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, J., & Shi, X. (2019). Grafting alleviates potassium stress and improves growth in tobacco. BMC Plant Biology, 19(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ievinsh, G., Andersone-Ozola, U., & Zeipiņa, S. (2020). Comparison of the effects of compost and vermicompost soil amendments in organic production of four herb species. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture, 36(4), 267–282. [CrossRef]

- Islam, F. A. S. (2023). “The Samiul Turn”: An Inventive Roadway Design Where No Vehicles Have to Stop Even for a Second and There is No Need for Traffic Control. European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research, 8(3), 76–79. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S., Islam, T., Al, S. A., Hossain, M., Adham, A. K. M., Islam, D., & Rahman, M. M. (2017). Impacts of dairy farm’s wastewater irrigation on growth and yield attributes of maize. Fundamental and Applied Agriculture, 2(2), 247–255. https://www.f2ffoundation.org/faa/index.php/home/article/view/174.

- Islam, S. M. S., Hossain, A., Hasan, M., Itoh, K., & Tuteja, N. (2023). Application of Trichoderma spp. as biostimulants to improve soil fertility for enhancing crop yield in wheat and other crops. Biostimulants in Alleviation of Metal Toxicity in Plants: Emerging Trends and Opportunities, 177–206. [CrossRef]

- Jokić, S., Gagić, T., Knez, Ž., Banožić, M., & Škerget, M. (2019). Separation of active compounds from tobacco waste using subcritical water extraction. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 153, 104593. [CrossRef]

- Karim, R., Nahar, N., Shirin, T., & Rahman, M. A. (2016). Study on tobacco cultivation and its impacts on health and environment at Kushtia, Bangladesh. J. Biosci. Agric. Res, 08(02), 746–753. [CrossRef]

- Kauser, H., & Khwairakpam, M. (2022). Organic waste management by a two-stage composting process to decrease the time required for vermicomposting. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 25, 102193. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. L., Wu, T. Y., Lim, P. N., & Shak, K. P. Y. (2015). The use of vermicompost in organic farming: Overview, effects on soil and economics. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 95(6), 1143–1156. [CrossRef]

- Manthos, G., & Tsigkou, K. (2025). Upscaling of tobacco processing waste management: A review and a proposed valorization approach towards the biorefinery concept. Journal of Environmental Management, 387, 125942. [CrossRef]

- Matharu, A. S., de Melo, E. M., & Houghton, J. A. (2016). Opportunity for high value-added chemicals from food supply chain wastes. Bioresource Technology, 215, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Mumba, P. P., & Phiri, R. (2008). Environmental impact assessment of tobacco waste disposal. Int. J. Environ. Res, 2(3), 225–230. https://www.sid.ir/EN/VEWSSID/J_pdf/108220080302.pdf.

- Nekliudov, A. D., Fedotov, G. N., & Ivankin, A. N. (2008). Intensification of composting processes by aerobic microorganisms: a review. Prikladnaia Biokhimiia i Mikrobiologiia, 44(1), 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B. T., Dinh, D. H., Hoang, N. B., Do, T. T., Milham, P., Thi Hoang, D., & Cao, S. T. (2022). Composted tobacco waste increases the yield and organoleptic quality of leaf mustard. Agrosystems, Geosciences and Environment, 5(3), e20283. [CrossRef]

- Novinscak, A., Surette, C., Allain, C., & Filion, M. (2008). Application of molecular technologies to monitor the microbial content of biosolids and composted biosolids. Water Science and Technology, 57(4), 471–477. [CrossRef]

- Odlare, M., Arthurson, V., Pell, M., Svensson, K., Nehrenheim, E., & Abubaker, J. (2011). Land application of organic waste – Effects on the soil ecosystem. Applied Energy, 88(6), 2210–2218. [CrossRef]

- Pang, F., Li, Q., Solanki, M. K., Wang, Z., Xing, Y. X., & Dong, D. F. (2024). Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15, 1383813. [CrossRef]

- Purwono, S., Murachman, B., Wintoko, J., Simanjuntak, B. A., Sejati, P. P., Permatasari, N. E., & Lidyawati, D. (2011). The Effect of Solvent for Extraction for Removing Nicotine on the Development of Charcoal Briquette from Waste of Tobacco Stem. Journal of Sustainable Energy & Environment, 2(1), 11–13. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JSEE/article/view/8818.

- Rahman, M. M., & Rahman, S. (2020) Adeyeye, Samuel Ayofemi Olalekan, Ton Duc Thang University, Vietnam. Original Research Article Rahman and Rahman. Asian Journal of Applied Chemistry Research, 5(3), 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Raman, G., Mohan, K. N., Manohar, V., & Sakthivel, N. (2014). Biodegradation of nicotine by a novel nicotine-degrading bacterium, Pseudomonas plecoglossicida TND35, and its new biotransformation intermediates. Biodegradation, 25(1), 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P., Embrandiri, A., Ibrahim, M. H., & Esa, N. (2011). Management of biomass residues generated from palm oil mill: Vermicomposting a sustainable option. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 55(4), 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Singh, J., Kandoria, A., Quadar, J., Bhat, S. A., Chowdhary, A. B., & Vig, A. P. (2020). Bioconversion of different organic waste into fortified vermicompost with the help of earthworm: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture, 9(4), 423–439. [CrossRef]

- Statista, 2023. Tobacco industry-statistics & facts.... - Google Scholar. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Statista%2C%202023.%20Tobacco%20industry-statistics%20%26%20facts.%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.statista.com%2Ftopics%2F1593%2Ftobacco%2F.

- Sultana, M. M., Kibria, M. G., Jahiruddin, M., Abedin, Md. A., Sultana, M. M., Kibria, M. G., Jahiruddin, M., & Abedin, Md. A. (2020). Composting Constraints and Prospects in Bangladesh: A Review. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 8(9), 126–139. [CrossRef]

- Tarım, S., Dergisi, G. B., Ceritoğlu, M., Şahin, S., & Erman, M. (2018). Effects of Vermicompost on Plant Growth and Soil Structure. Selcuk Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences, 32(3), 607–615. [CrossRef]

- Tautges, N. E., Chiartas, J. L., Gaudin, A. C. M., O’Geen, A. T., Herrera, I., & Scow, K. M. (2019). Deep soil inventories reveal that the impacts of cover crops and compost on soil carbon sequestration differ in surface and subsurface soils. Global Change Biology, 25(11), 3753–3766. [CrossRef]

- Valverde, J. L., Curbelo, C., Mayo, O., & Molina, C. B. (2000). Pyrolysis Kinetics of Tobacco Dust. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 78(6), 921–924. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Chávez, T. E., Sáenz-Mata, J., Quezada-Rivera, J. J., Palacio-Rodríguez, R., Muro-Pérez, G., Servín-Prieto, A. J., Hernández-López, M., Preciado-Rangel, P., Salazar-Ramírez, M. T., Ontiveros-Chacón, J. C., & Peña, C. G.-D. la. (2025). Bacterial and Physicochemical Dynamics During the Vermicomposting of Bovine Manure: A Comparative Analysis of the Eisenia fetida Gut and Compost Matrix. Microbiology Research 2025, Vol. 16, Page 177, 16(8), 177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Kong, Y., Liu, Y., Li, D., Zhang, X., Yuan, J., & Li, G. (2020). Evolution of phytotoxicity during the active phase of co-composting of chicken manure, tobacco powder, and mushroom substrate. Waste Management, 114, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Chen, K., Mo, L., & Li, J. (2013). Pretreatment of papermaking-reconstituted tobacco slice wastewater by coagulation-flocculation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 130(2), 1092–1097. [CrossRef]

- White, K. E., Brennan, E. B., Cavigelli, M. A., & Smith, R. F. (2020). Winter cover crops increase readily decomposable soil carbon, but compost drives total soil carbon during eight years of intensive, organic vegetable production in California. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0228677. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. H., & Steinbergs, A. (1959). Soil sulphur fractions as chemical indices of available Sulphur in some Australian soils. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(3), 340–352. [CrossRef]

- World Weather Online. https://www.worldweatheronline.com/lalmonirhat-weather-averages/bd.aspx.

- Zahedi, S., & Khalifehzadeh, R. (2025). The spatial distribution of Topsoil Organic Carbon in vegetation types of Chehelgazi rangelands, Sanandaj County, Kurdistan province. Watershed Management Research. [CrossRef]

- Zapałowska, A., Jarecki, W., Skwiercz, A., & Malewski, T. (2025). Optimization of Compost and Peat Mixture Ratios for Production of Pepper Seedlings. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(2), 442. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J., Singh, D., & Chen, S. (2011). Thermal decomposition kinetics of wheat straw treated by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 65(3), 410–414. [CrossRef]

- Zielke, D., Liebe, R., TABAKFORSCHUNG, H. A.-B. ZUR, & 1997, undefined. (n.d.). The removal of stems from cut tobacco. Sciendo.ComD Zielke, R Liebe, HM AGBEITRAGE ZUR TABAKFORSCHUNG INTERNATIONAL, 1997•sciendo.Com. Retrieved August 8, 2025, from https://sciendo.com/2/v2/download/issue/CTTR/17/2.zip.

| Compost Type | Used Organic Materials | Average C/N ratio | Mixing ratio (by weight) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow manure and vegetable leaves | Cow manure | 17.5:1 | 4 | 70.2:4 |

| Vegetable leaves | 78.6:1 | 1 | 78.6:1 | |

| Cow manure and tobacco leaves | Cow manure | 17.5:1 | 4 | 70.2:4 |

| Tobacco leaves | 70.6:1 | 1 | 70.6:1 | |

| Cow manure and tobacco stems | Cow manure | 17.5:1 | 4 | 70.2:4 |

| Tobacco stems | 98.7:1 | 1 | 98.7:1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).