1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of progressive optic neuropathies characterized by retinal ganglion cell loss and optic nerve damage, and it represents one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide [

1,

2]. In Japan, glaucoma accounts for approximately 40% of newly certified cases of visual disability [

3]. At present, reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only evidence-based approach to slowing or preventing disease progression [

2,

4].

Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCPC) has traditionally been reserved for refractory glaucoma cases with poor visual potential, as continuous-wave diode CPC was associated with severe complications such as persistent ocular hypotony and phthisis bulbi [

5].

Micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (MP-TSCPC) is a newer technique that delivers an 810-nm diode infrared laser in an on–off duty cycle mode (31.3% duty cycle), which minimizes collateral tissue damage [

6]. Since its introduction in 2015, the CYCLO G6 laser has been widely used, and numerous studies have demonstrated its efficacy and safety [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In April 2024, the VITRA 810 was introduced in Japan. Unlike the CYCLO G6, the VITRA 810 was originally developed as a multicolor retinal photocoagulation system, with the addition of a micropulse transscleral glaucoma module. However, reports on its clinical outcomes remain limited. Although the mechanism of IOP reduction by MP-TSCPC is not yet fully understood, previous animal studies have suggested that the procedure may increase uveoscleral outflow by inducing structural changes in the ciliary body, while others have proposed an effect on aqueous humor production or alterations in ciliary body microcirculation [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Moreover, anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) enables in vivo detection of ciliochoroidal effusion (CE), which has recently been reported after MP-TSCPC and may contribute to enhanced uveoscleral outflow [

30]. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the short-term outcomes of MP-TSCPC using the VITRA 810 in Japanese patients, with particular attention to the presence of CE as detected by AS-OCT.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study included 37 eyes from 34 consecutive patients with glaucoma who underwent MP-TSCPC using the VITRA 810 between March 2024 and March 2025 at Otsuka Eye Clinic, Oita, Japan. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Otsuka Eye Clinic. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before surgery.

Surgical Technique

Sub-Tenon’s anesthesia with 2% lidocaine was administered, and the VITRA 810 equipped with a transscleral glaucoma probe was applied to the superior and inferior hemispheres while avoiding the 3- and 9-o’clock positions. Laser settings consisted of a power of 2000–2500 mW and a maximum duration of 80 seconds per hemisphere, with a duty cycle of 31.3%. The probe was moved in a continuous sweeping manner during irradiation. Postoperatively, topical gatifloxacin (0.3%) and betamethasone (0.1%) were instilled four times daily for at least one week. Glaucoma medications prescribed before surgery were generally maintained throughout the follow-up period to allow evaluation of the surgical effect of MP-TSCPC itself.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

All patients underwent baseline screening, which included slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fundus examination, refraction testing, IOP measurement (iCare; M.E Technica, Tokyo, Japan), and BCVA assessment using a Landolt C chart. Refraction was measured with an autorefractor/keratometer (ARK-530A; Nidek, Tokyo, Japan). BCVA values were converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR). Postoperatively, all patients were evaluated at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. The glaucoma medication score was calculated by assigning one point for each single-agent medication and two points for each fixed-combination preparation. At each postoperative visit, IOP, medication score, and complications were assessed. Endothelial cell density was measured at 1 month using a specular microscope (CE530; Nidek, Tokyo, Japan). The presence of CE was evaluated at 1 week and 1 month postoperatively using AS-OCT (CASIA2, TOMEY, Aichi, Japan) at the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-o’clock meridians. Preoperative visual field testing was performed with the Humphrey Field Analyzer (Carl Zeiss Mediated, Dublin, CA, USA) using the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA)-Standard 24-2 protocol. Patients graded ocular pain using a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS). The primary outcome was the change in IOP from baseline. Secondary outcomes included changes in glaucoma medication score, the incidence of postoperative complications, the presence of CE, and surgical success. Surgical success was defined as an IOP between 6 and 21 mmHg or a reduction of at least 20% from baseline without additional glaucoma surgery. Failure was defined as an IOP less than 6 mmHg, greater than 21 mmHg despite maximal therapy, or the need for reoperation.

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 14. Paired t-tests were used to compare pre- and postoperative values, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for comparisons between CE-positive and CE-negative groups, and logistic regression for predictors of CE. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the cumulative probability of surgical success, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 37 eyes from 34 patients were analyzed. The baseline preoperative characteristics of the patients are summarized in

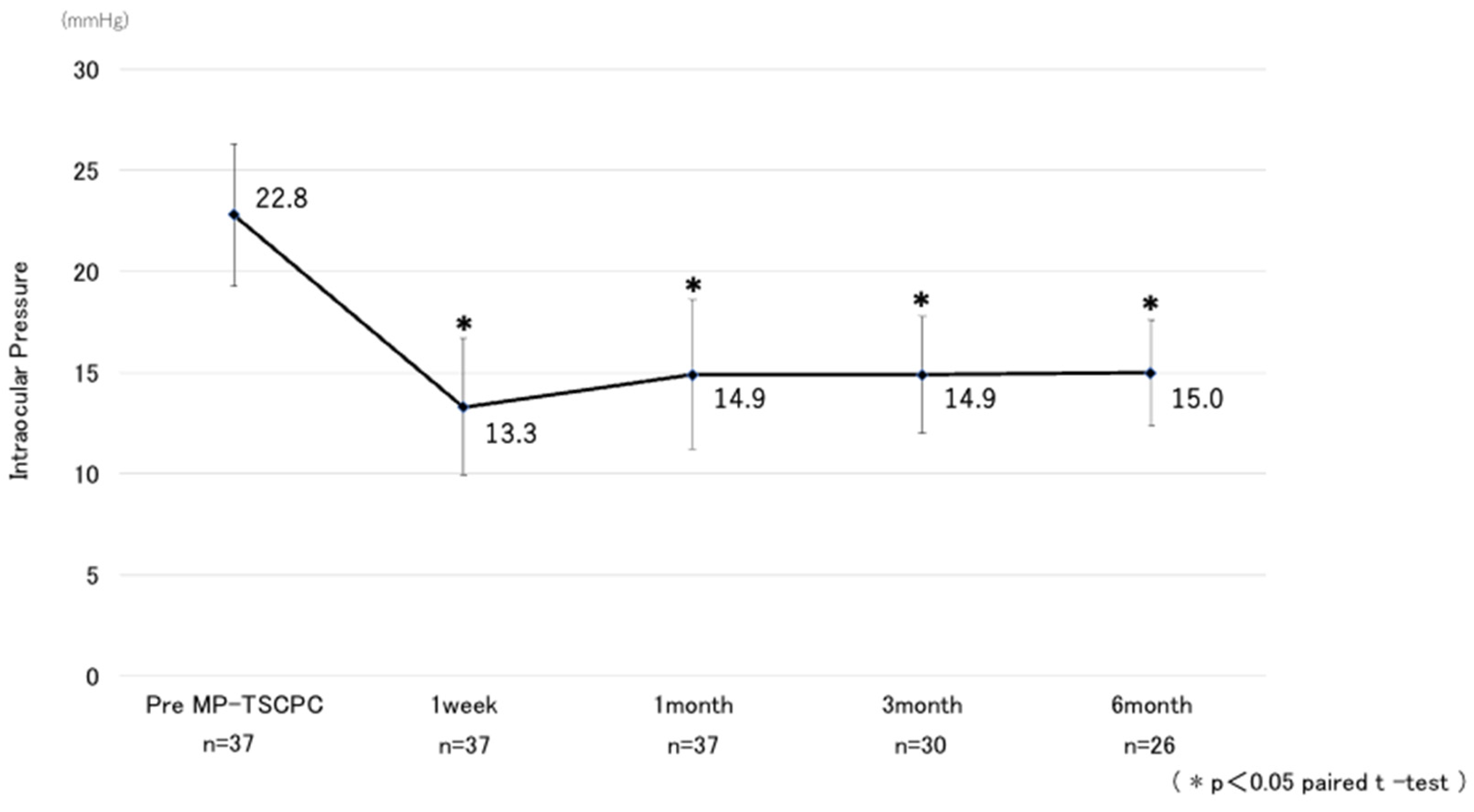

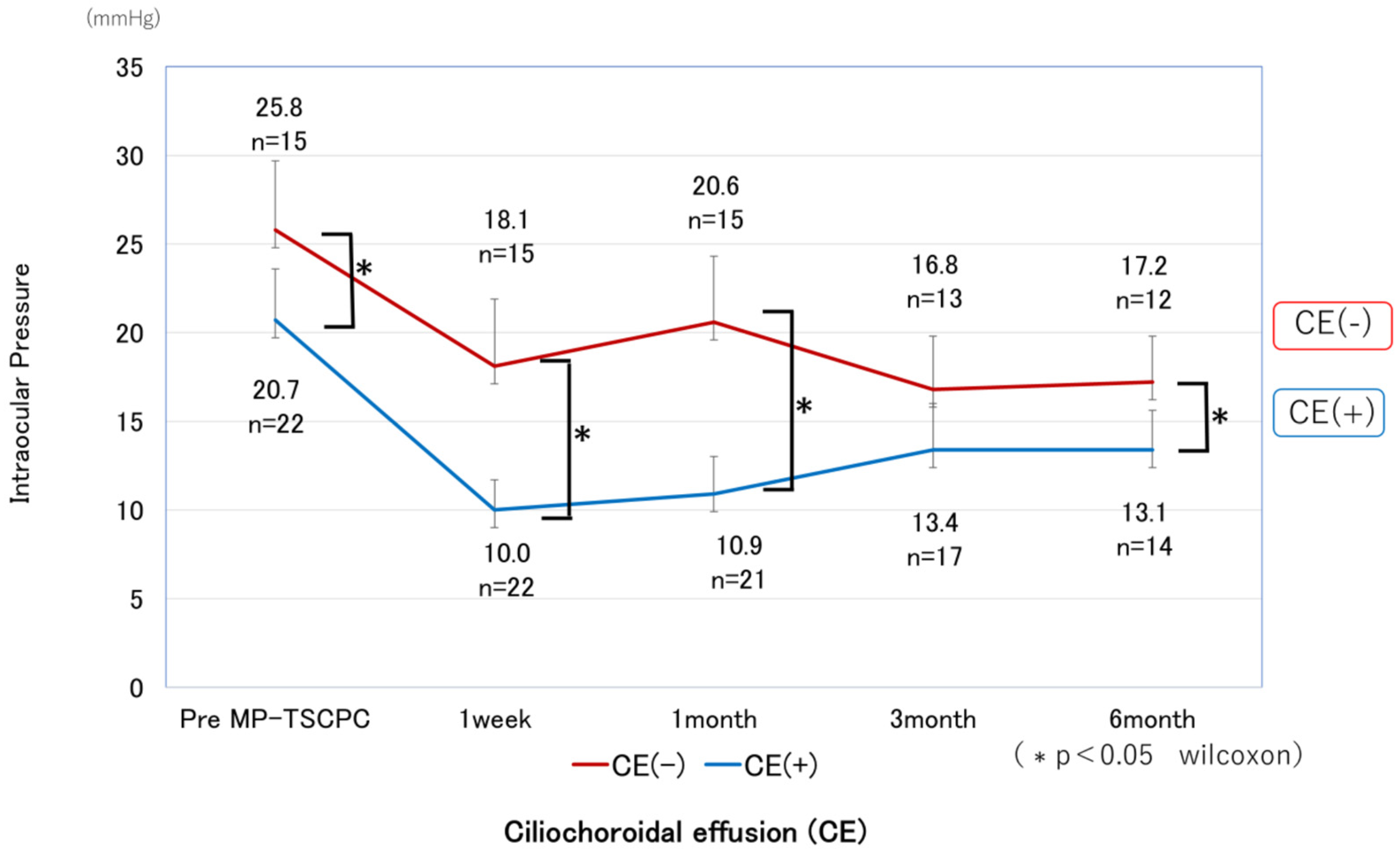

Table 1. The mean preoperative IOP was 22.8 ± 7.1 mmHg and decreased significantly at all postoperative time points, measuring 13.3 ± 6.8 mmHg at one week, 14.9 ± 7.4 mmHg at one month, 14.9 ± 5.8 mmHg at three months, and 15.0 ± 5.2 mmHg at six months, with all reductions significant compared with baseline (p < 0.05) (

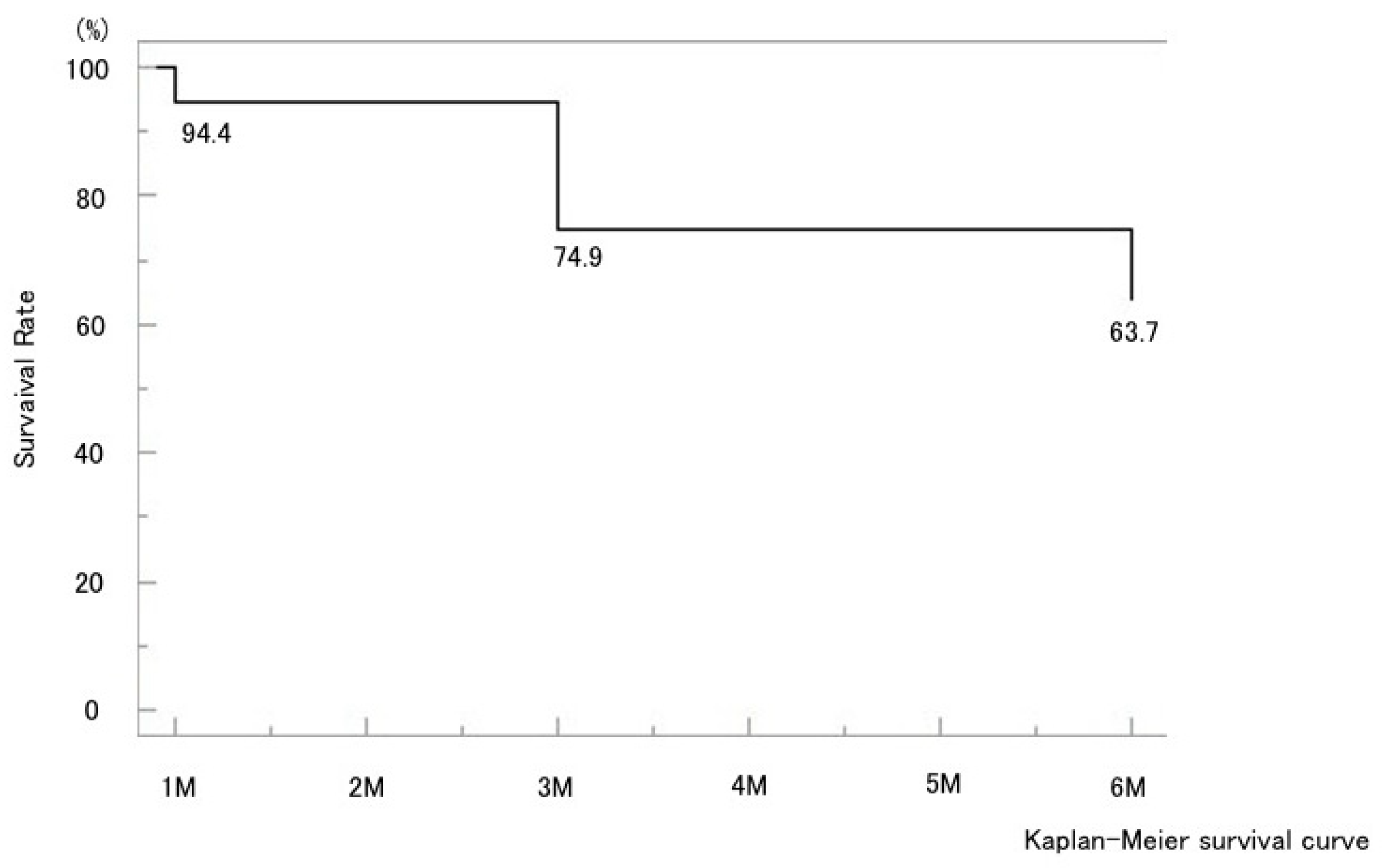

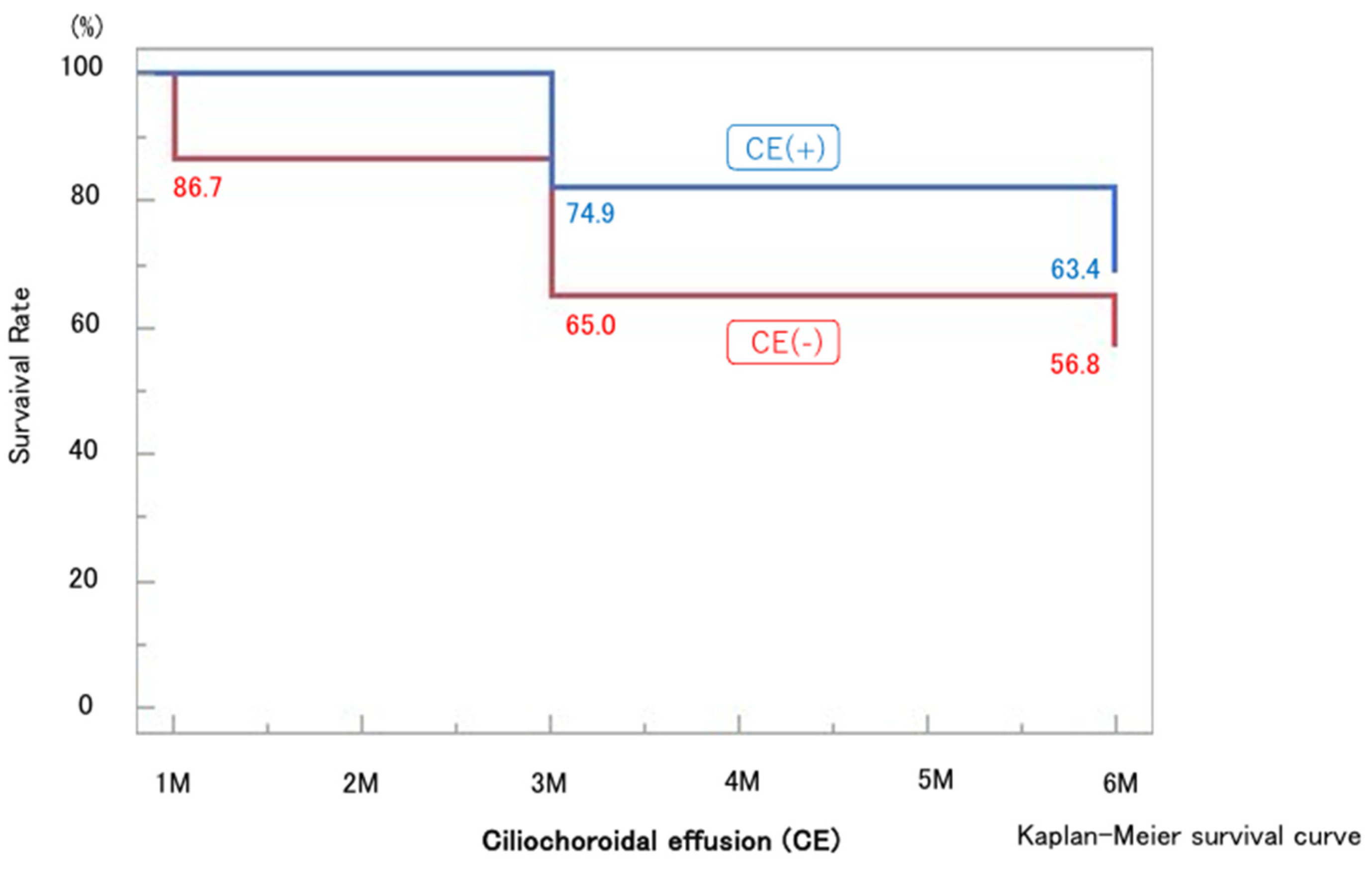

Figure 1). The mean IOP reduction rate at six months was 34.2%. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated a cumulative probability of surgical success of 63.7% at six months (

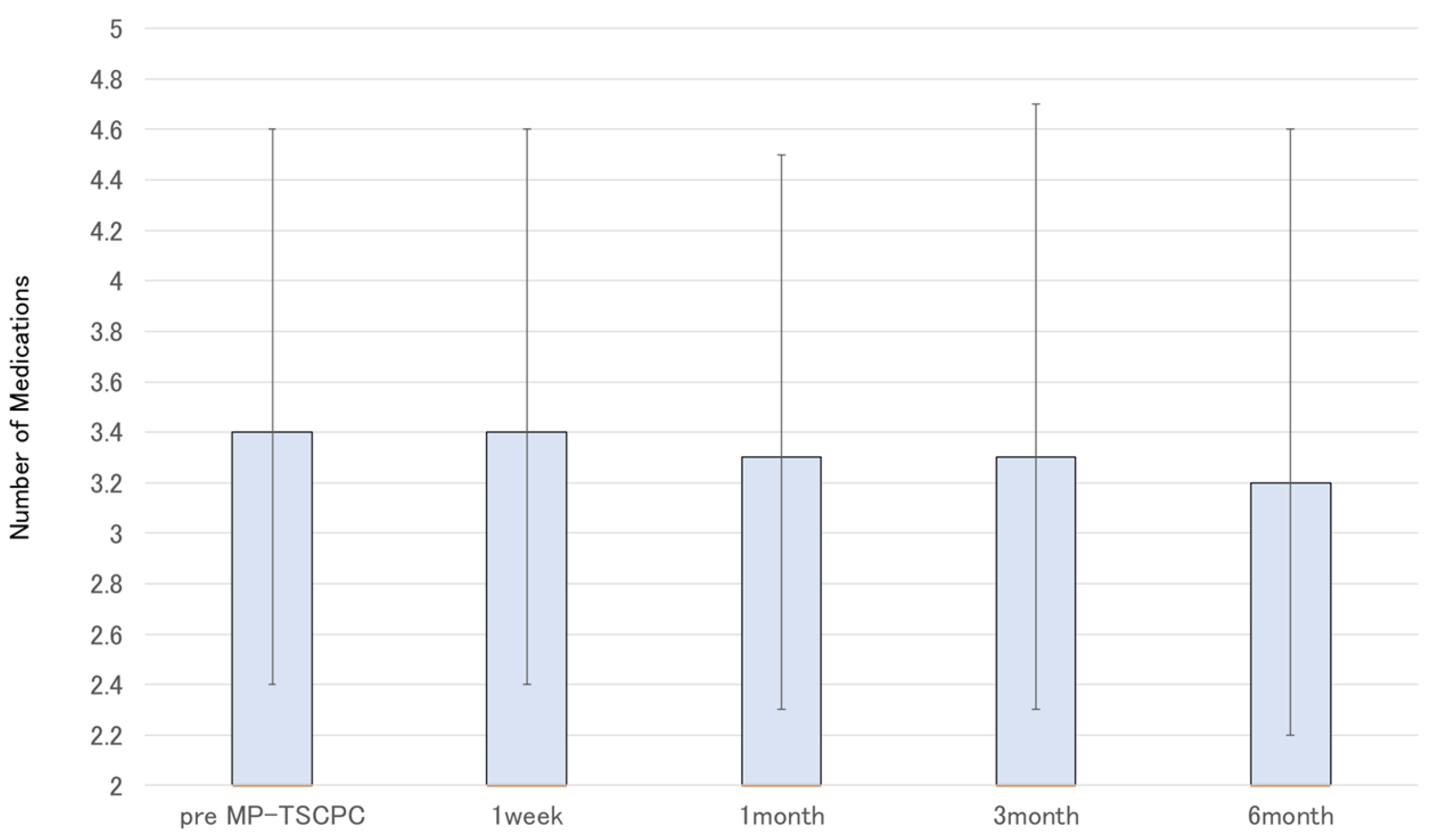

Figure 2). The glaucoma medication score decreased slightly by six months but without statistical significance (

Figure 3).

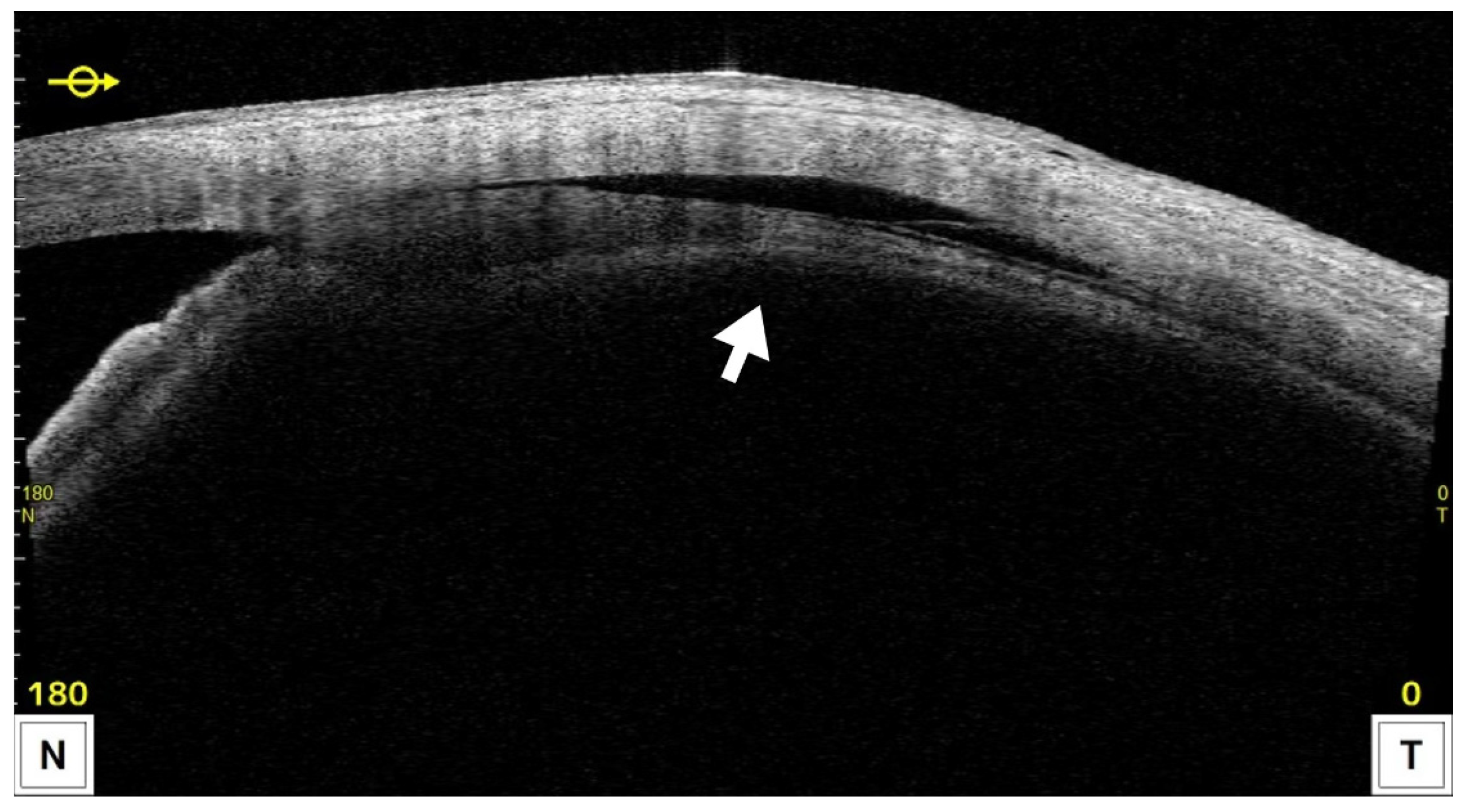

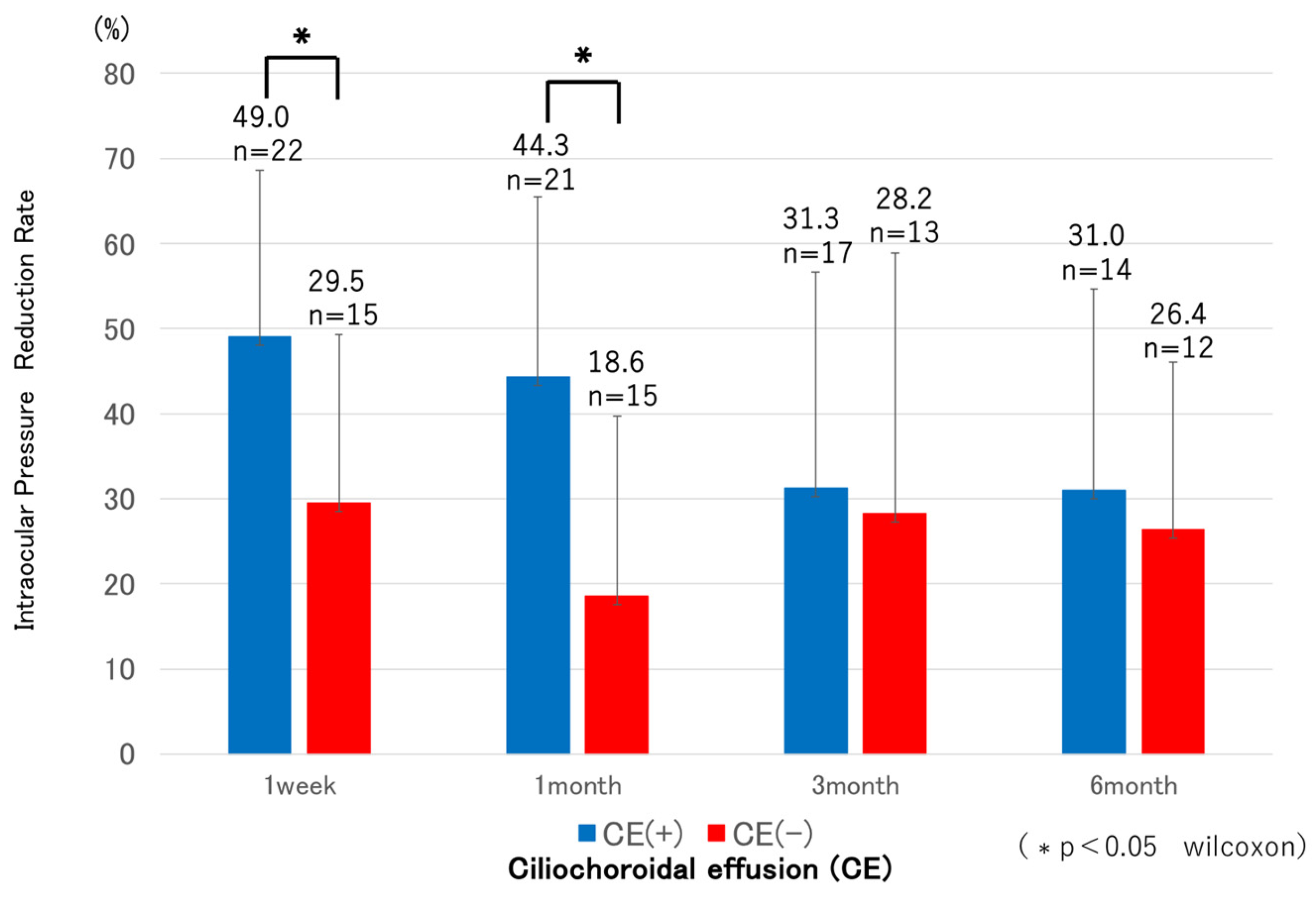

CE was detected by AS-OCT (

Figure 4) in 22 eyes (59.4%) at one week and resolved in all cases by 1 month postoperatively, except in the single eye that developed phthisis bulbi, after which IOP in the CE-positive group showed a tendency to increase. Both groups showed significant IOP reductions compared with preoperative levels at all postoperative time points (p < 0.05). In the CE(+) group, IOP decreased from 20.7 ± 5.8 mmHg preoperatively to 10.0–13.4 mmHg during follow-up, corresponding to reduction rates of 31–49%. In the CE(−) group, IOP decreased from 25.8 ± 7.8 mmHg to 16.8–20.6 mmHg, with reduction rates of 18–29%. Comparisons between groups revealed significantly lower IOP in the CE(+) group preoperatively, and at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months (

Figure 5), while the reduction rates were significantly greater in the CE(+) group at 1 week and 1 month (p < 0.05) (

Figure 6). The 6-month survival rate for all cases was 63.7% (

Figure 2). The 6-month survival rates were 63.4% in the CE(+) group and 56.8% in the CE(−) group, with no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.32) (

Figure 7). No statistically significant associations were found between the presence of CE and sex, age, glaucoma subtype, history of prior surgery, preoperative IOP, or preoperative visual field status (p > 0.05).

Best-corrected visual acuity did not change significantly overall, although three eyes (8.1%) lost at least 0.3 logMAR units. Endothelial cell density remained stable at one month. Postoperative complications included mydriasis, anterior chamber inflammation, vitreous hemorrhage, cystoid macular edema, decreased visual acuity, and phthisis bulbi are summarized in

Table 2. The mean postoperative pain score on the VAS was 3.6 ± 3.3.

4. Discussion

To date, there have been few reports of MP-TSCPC using the VITRA 810, whereas most published studies have employed the CYCLO G6 system. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of MP-TSCPC with the VITRA 810 in Japanese patients, as well as the relationship between postoperative CE and IOP.

In all cases, the mean IOP decreased significantly from 22.8 ± 7.1 mmHg preoperatively to 15.0 ± 5.2 mmHg at 6 months postoperatively, corresponding to a mean reduction rate of 34.2%. Previous studies using the CYCLO G6 have reported IOP reductions of approximately 30–45% [

8,

9,

10,

11], which is consistent with our findings. The survival rate, defined as an IOP between 6 and 21 mmHg or a ≥20% reduction from baseline without reoperation, was 63.7% at 6 months. Prior reports using a similar definition [

9,

10,

12] described survival rates ranging from 45.5% to 83.3%, and our results fall within this range.

Pain during MP-TSCPC was reported as 3.6 ± 3.3 on a 10-point visual analog scale. As MP-TSCPC is inherently associated with ocular discomfort, adequate anesthesia is essential. Retrobulbar or sub-Tenon’s anesthesia is frequently employed, but these methods can cause transient visual impairment; therefore, special caution is required when performing MP-TSCPC in the only seeing eye in an outpatient setting.

The most common postoperative complication was mydriasis, observed in 9 eyes (24.3%). This may result from injury to the terminal branches of the short ciliary nerves. Chen et al. reported an incidence of 3.3%, and Radhakrishnan et al. 11%, with particularly higher rates in Asian patients (odds ratio 13.07) [

9,

13]. Although most cases resolve spontaneously, some patients require pilocarpine therapy to alleviate photophobia. In this study, six patients were treated with 1% pilocarpine for symptomatic photophobia, which was discontinued after approximately one month when symptoms improved. Two eyes still exhibited incomplete recovery of pupil size at the final follow-up, though with a trend toward resolution.

Anterior chamber inflammation is a commonly reported complication, with incidences ranging from a few percent to 25% [

9,

14,

15]. We observed it in 24.3% of cases, supporting the use of postoperative anti-inflammatory eye drops. One case of hyphema occurred in an eye with a prior trabeculotomy, likely due to reflux bleeding following postoperative IOP reduction. CME, though uncommon (several to 5% of cases [

15,

16,

17]), developed in two eyes. In one patient with a history of uveitis, CME was likely triggered by postoperative inflammation and resolved promptly with sub-Tenon’s injection of triamcinolone acetonide.

Three eyes experienced a loss of more than 0.2 logMAR in visual acuity. Two of these had advanced central visual field defects preoperatively and exhibited further progression postoperatively. The remaining eye developed severe inflammation and persistent hypotony after MP-TSCPC, eventually progressing to phthisis bulbi at 4 months, with profound vision loss. Although cataract progression has been reported as a cause of visual decline after MP-TSCPC [

18], it was not observed in our study. Persistent hypotony and phthisis bulbi reported elsewhere have been attributed to excessive energy delivery or suboptimal surgical technique [

15]. In our case, although severe anterior segment inflammation was noted postoperatively, total delivered energy (125.2 J) was within the recommended range for the CYCLO G6 (P3 probe) [

19]. Because the VITRA 810 probe tip is narrower than that of the CYCLO G6, it is possible that improper angulation toward the cornea could result in unintended irradiation of the ciliary processes rather than the pars plana. Furthermore, given that eyes with darker pigmentation generally respond to lower laser energy [

20,

21,

22], the energy level used may have been excessive for this patient. Further studies are needed to establish optimal energy parameters for Asian populations when using the VITRA 810.

In this study, CE was assessed using AS-OCT (CASIA2) at 1 week and 1 month. CE was observed in 22 eyes (59.4%) at 1 week, and eyes in the CE-positive group exhibited significantly greater IOP reduction and reduction rates compared with CE-negative eyes at both 1 week and 1 month. CE had resolved by 1 month in all eyes except the one that developed phthisis bulbi, after which IOP in the CE-positive group demonstrated a trend toward increase.

The mechanisms of IOP reduction by MP-TSCPC are thought to be multifactorial, including subthreshold damage to pigmented and non-pigmented ciliary epithelium leading to reduced aqueous humor production [

23,

24,

25], pilocarpine-like contraction of the ciliary muscle enhancing trabecular outflow [

26,

27,

28], and extracellular matrix remodeling near the pars plana promoting uveoscleral outflow [

29,

30]. CE may indicate an enhancement of uveoscleral outflow, supported by pathological findings of widened ciliary muscle bundles and OCT evidence of increased choroidal thickness in human eyes [

27,

29]. Consistent with our findings, Chansangpetch et al. reported that CE-positive eyes had significantly greater IOP reduction at 1 month post-MP-TSCPC [

30].

This study has several limitations. It was retrospective in design, conducted at a single institution, with a relatively small sample size and short follow-up. Further studies with larger cohorts and longer-term follow-up are necessary.

5. Conclusions

MP-TSCPC using the VITRA 810 significantly reduced IOP in Japanese patients with glaucoma in the short term. Postoperative CE was frequently observed and associated with greater early IOP reduction, suggesting a possible mechanism of enhanced uveoscleral outflow. Although overall safety was acceptable, rare severe complications such as phthisis bulbi emphasize the importance of close monitoring. These results provide new evidence on the performance of the VITRA 810 in Japan, and larger, longer-term studies are required to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and T.K.; Methodology, S.H.; Formal Analysis, S.H.; Investigation, S.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, T.K.; Supervision, S.O. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Otsuka Eye Clinic.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Quigley, H.A. Glaucoma. Lancet 2011, 377, 1367–1377.

- Weinreb, R.N.; Aung, T.; Medeiros, F.A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–1911.

- Matoba, R.; Morimoto, N.; Kawasaki, R.; Fujiwara, M.; Kanenaga, K.; Yamashita, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Morizane, Y. A nationwide survey of newly certified visually impaired individuals in Japan for the fiscal year 2019: impact of the revision of criteria for visual impairment certification. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 67, 346–352. [CrossRef]

- The AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 130, 429–440.

- Bloom, P.A.; Tsai, J.C.; Sharma, K.; Miller, M.H.; Rice, N.S.; Hitchings, R.A.; Khaw, P.T. “Cyclodiode”. Transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in the treatment of advanced refractory glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1997, 104, 1508–1520.

- De Vries, V.A.; Pals, J.; Poelman, H.J.; Rostamzad, P.; Wolfs, R.C.W.; Ramdas, W.D. Efficacy and safety of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3447. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, H.; Honjo, M.; Okamoto, M.; Sugimoto, K.; Aihara, M. Potential mechanisms of intraocular pressure reduction by micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in rabbit eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 3. [CrossRef]

- Valle, I.T.; Bazarra, S.P.; Taboas, M.F.; Cid, S.R.; Diaz, M.D.A. Medium-term outcomes of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2022, 16, 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Yeh, P.H.; Yeh, C.T.; Su, W.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Chuang, L.H.; Shen, S.H.; Wu, W.C. Micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in a Taiwanese population: 2-year clinical outcomes and prognostic factors. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 1265–1273. [CrossRef]

- Vig, N.; Ameen, S.; Bloom, P.; Crawley, L.; Normando, E.; Porteous, A.; Ahmed, F. Micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation: initial results using a reduced energy protocol in refractory glaucoma. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 1073–1079. [CrossRef]

- Yelenskiy, A.; Gillette, T.B.; Arosemena, A.; Stern, A.G.; Garris, W.J.; Young, C.T.; Hoyt, M.; Worley, N.; Zurakowski, D.; Ayyala, R.S. Patients outcomes following micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation: intermediate-term results. J. Glaucoma 2018, 27, 920–925. [CrossRef]

- Chamard, C.; Bachouchi, A.; Daien, V.; Villain, M. Efficacy, safety, and retreatment benefit of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2021, 30, 781–788. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Wan, J.; Tran, B.; Thai, A.; Hernandez-Siman, J.; Chen, K.; Nguyen, N.; Pickering, T.D.; Tanaka, H.G.; Lieberman, M.; et al. Micropulse cyclophotocoagulation: A Multicenter study of efficacy, safety, and factors associated with increased risk of complications. J. Glaucoma 2020, 29, 1126–1131. [CrossRef]

- Issiaka, M.; Zrikem, K.; Mchachi, A.; Benhmidoune, L.; Rachid, R.; El Belhadji, M.; Youssoufou, S.A.S.; Amza, A. Micropulse diode laser therapy in refractory glaucoma. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2022, 3, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.L.; Moster, M.R.; Rahmatnejad, K.; Reynolds, M.; Horan, T.; Waisbourd, M. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2018, 27, 445–449. [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.J.Y.; Cecilia, A.M.; Lim, D.K.A.; Sng, C.C.A.; Loon, S.C.; Lun, K.W.X.; Chew, P.T.K.; Koh, V.T.C. Clinical efficacy and safety outcomes of micropulse transscleral diode cyclophotocoagulation in patients with advanced glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2021, 30, 257–265. [CrossRef]

- Kelada, M.; Normando, E.M.; Cordeiro, F.M.; Crawley, L.; Ahmed, F.; Ameen, S.; Vig, N.; Bloom, P. Cyclodiode versus micropulse transscleral laser treatment. Eye (Lond.) 2024, 38, 1477–1484. [CrossRef]

- Varikuti, V.N.V.; Shah, P.; Rai, O.; Chaves, A.C.; Miranda, A.; Lim, B.A.; Dorairaj, S.K.; Sieminski, S.F. Outcomes of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in eyes with good central vision. J. Glaucoma 2019, 28, 901–905. [CrossRef]

- Grippo, T.M.; de Crom, R.M.P.C.; Giovingo, M.; Töteberg-Harms, M.; Francis, B.A.; Jerkins, B.; Brubaker, J.W.; Radcliffe, N.; An, J.; Noecker, R. Evidence-based consensus guidelines series for micropulse transscleral laser therapy: dosimetry and patient selection. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 1837–1846. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.J.C.; Li, K.K.K.; Tang, S.W.K. Retrospective review on the outcome and safety of transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma in Chinese patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019, 39, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Pandav, S.S.; Jain, R.; Ansal, S.; Gupta, A. Lower energy levels adequate for effective transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in Asian eyes with refractory glaucoma. Eye (Lond.) 2008, 22, 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Cantor, L.B.; Nichols, D.A.; Katz, L.J.; Moster, M.R.; Poryzees, E.; Shields, J.A.; Spaeth, G.L. Neodymium-YAG transscleral cyclophotocoagulation. The role of pigmentation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989, 30, 1834–1837.

- Desmettre, T.J.; Mordon, S.R.; Buzawa, D.M.; Mainster, M.A. Micropulse and continuous wave diode retinal photocoagulation: visible and subvisible lesion parameters. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 709–712. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.J.; Mizukawa, A.; Okisaka, S. Mechanism of intraocular pressure decrease after contact transscleral continuouswave Nd: YAG laser cyclophotocoagulation. Ophthalmic Res. 1994, 26, 65–79. [CrossRef]

- Tsujisawa, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Uga, S.; Asakawa, K.; Kono, Y.; Mashimo, K.; Shoji, N. Morphological changes and potential mechanisms of intraocular pressure reduction after micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in rabbits. Ophthalmic Res. 2022, 65, 595–602. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.G.; Perirano-Bonomi, J.C.; Grippo, T.M. Micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation : a hypothesis for the ideal parameters. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2018, 7, 94–100.

- Johnstone, M.A. Microscope real-time video (MRTV), highresolution OCT (HR-OCT) & histopathology (HP) to assess how transscleral micropulse laser (TML) affects the sclera, ciliary body (CB), muscle (CM), secretory epithelium (CBSE), suprachoroidal space (SCS) & aqueous. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2825.

- Ahn, S.M.; Choi, M.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.Y. Changes after a month following micropulse cyclophotocoagulation in normal porcine eyes. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 11. [CrossRef]

- Barac, R.; Vuzitas, M.; Balta, F. Choroidal thickness increase after micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 62, 144–148.

- Chansangpetch, S.; Taechajongjintana, N.; Ratanawongphaibul, K.; Itthipanichpong, R.; Manassakarn, A.; Tantiseve, V.; Rojanapongpun, P.; Lin, S.C. Ciliochoroidal effusion and its association with the outcomes of micropulse transscleral laser therapy in glaucoma patiants: a pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16403. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).