I. Introduction

Macro Context—From Educational Governance to Information Governance. As national strategies like “New Engineering” and “Double First-Class” initiatives deepen, societal sensitivity toward academic integrity and transparency in university governance has significantly increased. Concurrently, content moderation and visibility allocation on social platforms continually reshape the emergence and diffusion of public discourse, creating a coupling trend among “platform governance—public sentiment—rule of law” (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021). At the evidence acquisition level, open-source intelligence (OSINT) emphasizes multi-source cross-verification and the construction of verifiable evidence chains, yet it still faces methodological blind spots regarding platform-side logs, post-deletion processes, and cross-jurisdictional evidence collection. While the introduction of AI/NLP has enhanced large-scale processing capabilities, it also introduces new risks related to explainability and bias (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020; Bender et al., 2021). Furthermore, online communication studies indicate that false/controversial information gains greater diffusion advantages in networks, with stronger backlash and polarization effects when transparent procedural explanations are absent (Vosoughi et al., 2018).

Problem Domain—The Multi-Layered Overlap in the Shanghai Maritime University Case. Within this macro-context, the Shanghai Maritime University incident exhibits a typical multi-layered overlap of “academic integrity dispute × platform information handling × organizational response × judicial intervention”: Professor Qu Qunzhen, the whistleblower, alleged “7 categories and 40 instances of fraudulent practices” in the application for the “2020 National First-Class Undergraduate Program Development Initiative,” claiming subsequent disciplinary actions and online information deletions (Caixin, 2023); On April 10, 2023, the university issued a Situation Report concluding that “the allegations were found to be unfounded” and emphasizing the authenticity and compliance of the materials (Shanghai Maritime University, 2023). The incident thus transcended institutional governance boundaries, entering the realms of public opinion and judicial proceedings while coupling with national-level narratives on academic integrity and governance.

Literature Gap—Insufficient Integration in Evidence Governance. Key gaps persist across four main research strands: (1) Limited discussion on the procedural reviewability of OSINT regarding platform-side evidence (deletion logs, triggering clauses, appeal pathways), making it difficult to meet judicial/administrative admissibility requirements (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020); (2) Platform governance remains dominated by principle-based initiatives, lacking verifiable process evidence standards and cross-domain transfer pathways (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021); (3) Academic integrity/whistleblowing studies emphasize organizational behavior but fail to align evidence chains with platform evidence flows, independent verification, and judicial procedures (Near & Miceli, 1985; Fanelli, 2009); (4) Information diffusion studies reveal the “deletion-rebound-amplification” logic, yet fail to establish operational linkages with evidence governance and national security assessments (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Therefore, there is an urgent need for an AI-enhanced OSINT-platform-procedural-judicial/administrative trinity “evidence governance” framework to achieve a verifiable, traceable, and accountable evidence loop in educational dispute scenarios.

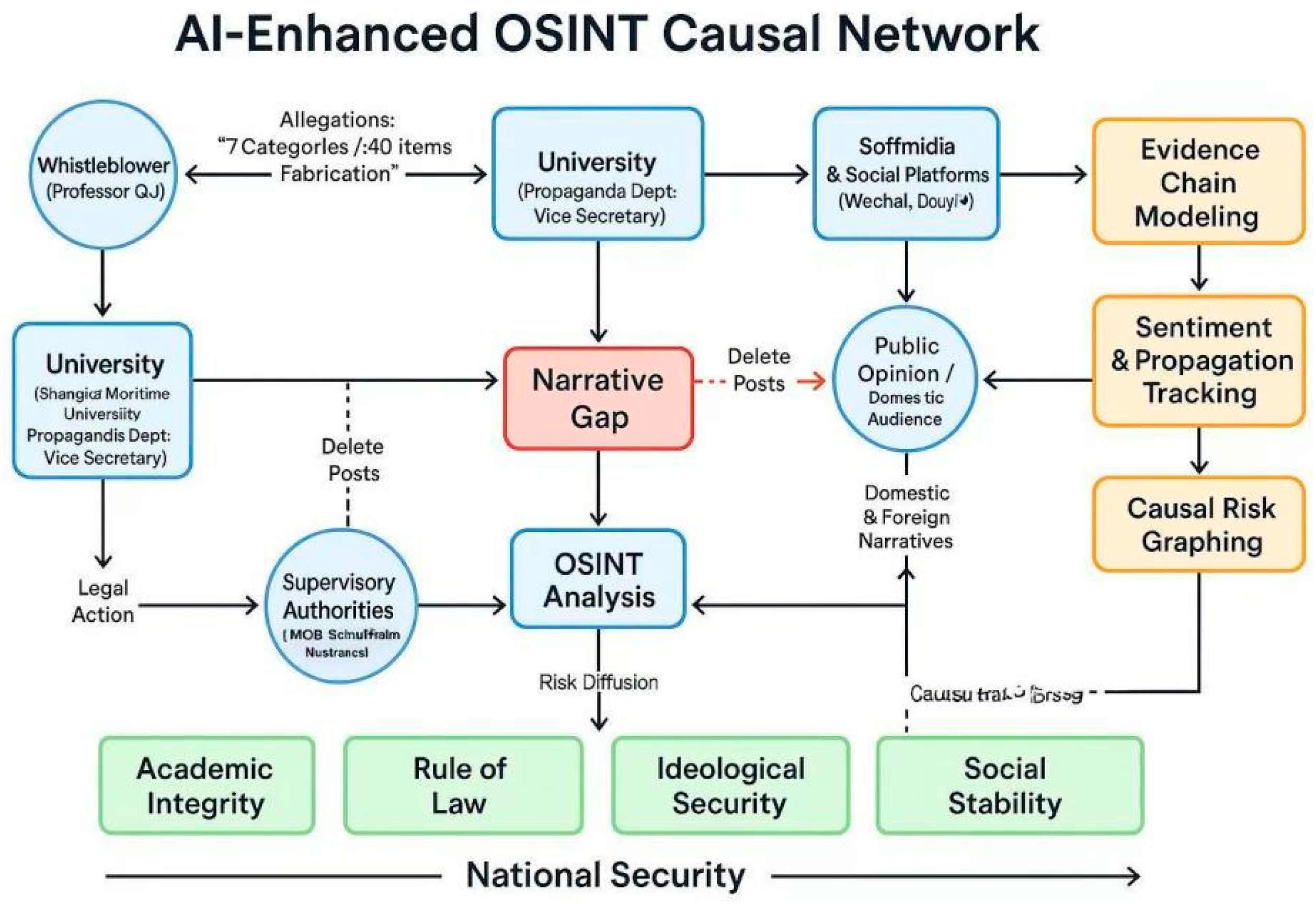

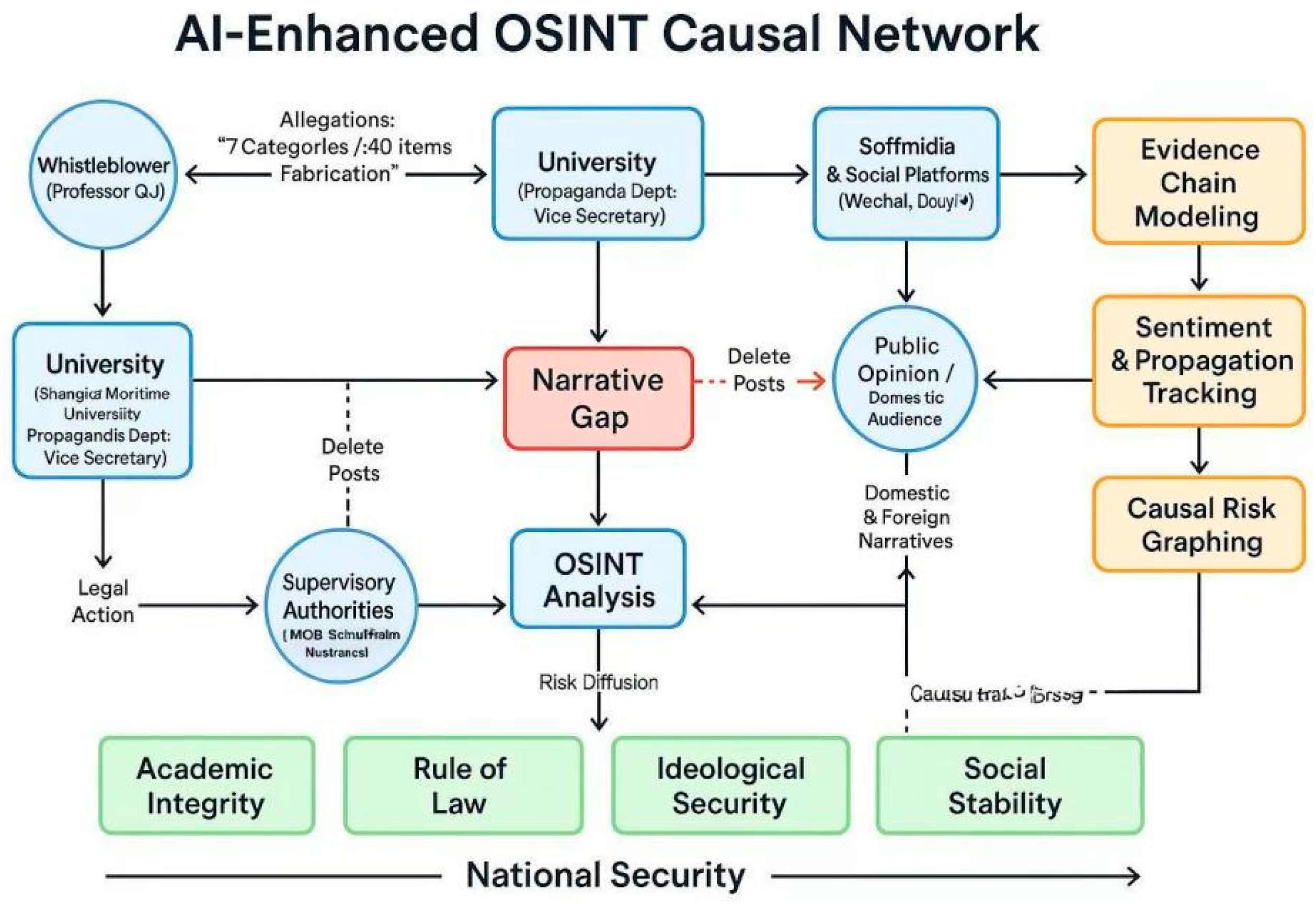

Research Motivation—Why This Study Is Essential. Anchored by the Shanghai Maritime University incident, this study aims to validate whether AI-enhanced OSINT can, within multi-source heterogeneous information: ① Reconstruct verifiable timestamped evidence chains; ② Identify narrative consistency/inconsistency and quantify their evidentiary strength; ③ Integrate platform post-deletion and log evidence into auditable processes; ④ Map educational case spillovers into causal networks of four-dimensional risks—academic integrity, rule-of-law trust, ideological security, and social stability—providing visualizable and testable decision-making foundations (Gillespie, 2018; NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020).

Research Questions and Testable Hypotheses. Based on the aforementioned gaps and motivations, I propose the following research questions (RQs) and hypotheses (Hs):

RQ1: Can an AI-enhanced OSINT approach rebuild a reviewable chain of evidence and narrow the ‘narrative gap’ in educational disputes? (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020)

H1: AI+OSINT’s timestamped evidence chain significantly improves source consistency and traceability compared to manual collation that relies only on a single source.

RQ2: Does incorporating platform-side deletion/display-limiting logs and complaint pathways into evidence-based governance reduce the public opinion risk of communication backlash and outreach amplification? (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021; Vosoughi et al.)

H2: Contexts with greater procedural transparency have a lower intensity of negative narrative diffusion given equal external stimuli.

RQ3: Is there a quantifiable correlation between the level of evidential governance in the education case and the four dimensions of national security risk?

H3: Higher levels of evidence governance completeness (independent review, evidence disclosure, platform traceability) are associated with a significant decrease in the four-dimensional composite risk of academic integrity/rule of law/ideology/social stability.

Structural Overview. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Part II systematically examines four research strands—OSINT methodology, platform governance and content moderation transparency, academic integrity and whistleblowing in higher education, and online information diffusion mechanisms—and synthesizes an integrated evidence governance framework spanning “collection-verification-disclosure-audit-accountability.” Part Three details the research design and methodology (data sources, AI/NLP pipelines, evidence chain modeling, and causal network analysis). Part Four presents empirical findings (evidence chain reconstruction, narrative consistency detection, platform log forensics, and risk mapping). Part Five discusses theoretical and policy implications (including national security dimensions). Part Six concludes with limitations, proposes replicable evidence governance operational frameworks, and outlines future research directions.

The diagram follows a narrative arc of “Reporting → Response → Post Removal → Public Sentiment → Judicial/Regulatory Action → Risk Spillover”: The whistleblower (Qu Qunzhen) raised allegations of “7 categories and 40 instances of fraud,” which the university (including the Deputy Secretary of the Publicity Department and two successive deans) denied in an official “Situation Report”; After content was taken down from platforms like WeChat and Douyin, a “narrative gap” emerged between the whistleblower’s account and the university’s official stance. This triggered OSINT analysis and judicial proceedings, potentially involving intervention by the Ministry of Education and municipal education authorities. Media and platforms jointly shaped domestic public opinion, while overseas media amplified related narratives. AI-enhanced OSINT methods performed three critical functions: First, narrative consistency verification and evidence chain modeling, reconstructing multi-source facts via timestamps; second, sentiment analysis and dissemination tracking, mapping the impact pathways of post deletions and re-circulation; third, causal risk mapping, visualizing the network linking “educational corruption—public sentiment diffusion—institutional trust volatility.” Ultimately, the incident’s risk implications converge on four dimensions of national security: academic integrity, rule of law and institutional trust, ideological security, and social stability. These manifest as systemic pressure points on credibility and governance effectiveness within the broader framework of national security.

II. Literature Review

This study explores how AI-enhanced open-source intelligence (OSINT) can reconstruct evidence chains and conduct risk assessments in scenarios involving academic integrity disputes and information governance within higher education institutions. Existing literature broadly follows four main strands: OSINT methodology and evidentiary standards; platform governance and content moderation transparency; whistleblowing and academic integrity in higher education; and the coupling mechanism between public sentiment, governance, and national security. Building upon this foundation, this study critically synthesizes methodological and conclusional tensions across these themes, thereby identifying research gaps and innovation points.

2.1. OSINT Methodology and Standards of Evidence: From “open source collection” to “verifiable chain of evidence”

Classic OSINT literature emphasizes that cross-referencing multiple sources and verifiability are key to elevating open information to intelligence evidence (NATO Open Source Intelligence Handbook, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020). Both NATO manuals and intelligence textbooks advocate for grading sources based on traceability, timeliness, and reliability to mitigate the risk of “single-source, arbitrary conclusions” (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020). In recent years, AI/NLP has been introduced to enhance text extraction, entity alignment, and timeline calibration capabilities. However, academia remains vigilant about the interpretability and bias issues introduced by algorithms (Bender et al., 2021). In educational public opinion cases, open-source evidence typically manifests as media reports, institutional bulletins, and platform activity logs. Its authenticity and completeness heavily depend on versioning trails and cross-verification (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020).

Critical Review: Traditional OSINT frameworks demonstrate maturity in source classification and cross-verification, yet they inadequately address the collection and auditing pathways for procedural evidence such as platform-side “post deletion and traffic restriction.” While AI integration enhances scalable processing capabilities, it amplifies risks associated with black-box operations and misjudgments (Bender et al., 2021). Therefore, OSINT in educational settings requires establishing human-machine collaborative, explainable, and verifiable evidence chain standards—not merely a technical stack of “scraping-and-aggregating” tools.

2.2. Transparency in Platform Governance and Content Review: From “gatekeeper” to “reviewable process”

Regarding social media content governance, Gillespie (2018) argues that platforms have become a new type of “gatekeeper of public discourse,” whose power to allocate visibility determines the boundaries of event narratives and public perception (Gillespie, 2018). The Santa Clara Principles further advocate for explainable removal justifications, appeal channels, and data disclosure to mitigate the legitimacy crisis of “black-box moderation” (The Santa Clara Principles, 2021). This approach suggests that in university controversies, content removal without procedural documentation or appeal pathways not only exacerbates public sentiment but also creates “evidence gaps” for OSINT investigations.

Critical Commentary: Platform governance literature predominantly focuses on self-regulation and public values, yet lacks systematic elaboration on legal admissibility of evidence and interfaces with administrative oversight. Cross-jurisdictional scenarios reveal persistent tensions between “transparency reports—judicial assistance—national security exemptions.” For educational cases, it is imperative to integrate platform evidence (logs, timestamps, trigger rules) into an auditable evidence governance framework, moving beyond mere normative advocacy (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021).

2.3. Whistleblowing and Academic Integrity in the HE Sector: Organisational Responses, Evidentiary Thresholds and System Trust

Classic whistleblowing studies indicate that organizational responses to reports depend on power structures, procedural justice, and retaliation costs, while the effectiveness of whistleblowing heavily relies on evidence strength and external review mechanisms (Near & Miceli, 1985). Epidemiological evidence on academic misconduct shows that while fabrication/falsification/selective reporting remain rare, their spillover effects significantly erode field-wide trust (Fanelli, 2009). In university governance contexts, institutional statements and whistleblower narratives often create conflicting accounts. Without independent verification and procedural transparency, this dynamic risks descending into a “each side tells its own story—trust collapses” impasse (Near & Miceli, 1985; Fanelli, 2009).

Open-source materials related to this case: Shanghai Maritime University issued a Situation Report on April 10, 2023, stating that the relevant allegations were “found to be unfounded” and defining the involved research output as a team achievement under official duties (Shanghai Maritime University, 2023). Media reports indicate the whistleblower subsequently filed a lawsuit, with the case entering the filing stage. However, authoritative court documents and the final investigation report from the competent authority have yet to be fully disclosed through public channels (Caixin, 2023; Top News, 2023).

Critical Commentary: Dialogue with international literature indicates that internal organizational statements lacking evidence lists, investigation team composition, and versioning trails struggle to meet verifiable evidence standards (Near & Miceli, 1985). For OSINT practitioners, this chain of “official statements—unilateral narratives—media retellings” necessitates multi-source timestamp comparisons and evidence chain modeling to mitigate information asymmetry.

2.4. The Coupling of Public Opinion-Governance-National Security: Mechanisms for the Diffusion of False and True Information

Regarding information diffusion, a large-scale study in Science indicates that false information spreads more readily on social networks and is driven by novelty, amplifying emotional reactions and polarization (Vosoughi et al., 2018). When platforms implement “post deletion/demotion” measures without adequate explanation, conspiracy narratives and external propaganda frameworks can more readily exploit the vacuum, elevating individual cases into evidence of “systemic problems” (Gillespie, 2018). From a national security perspective, the failure of educational integrity and imbalances in information governance compound into risks to ideological and institutional trust, necessitating a coordinated mechanism of independent review—transparent procedures—evidence disclosure (Lowenthal, 2020; Vosoughi et al., 2018).

Critical Commentary: Diffusion studies have revealed the risk chain of “post deletion—opacity—backlash,” yet institutional pathways for evidence governance remain incomplete. Existing research predominantly focuses on dissemination consequences, with limited integration into admissible evidence systems and administrative/judicial coordination. This constitutes a critical gap that OSINT in educational contexts must address.

2.5. Thematic Integration and Dialogue: Coupling Four Threads of Literature into an “evidence governance” Framework

Based on the above research, I propose a thematic integration framework:

Theme A: Verifiable OSINT Evidence Chains—centered on source classification, timestamping, and multi-source cross-referencing (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020), incorporating explainable AI assistance (Bender et al., 2021);

Theme B: Platform Transparency and Appeal Mechanisms—Incorporating “post deletion/traffic throttling” into auditable and accountable processes (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021);

Theme C: Independent Review of University Reporting and Academic Integrity—Aligning organizational notifications, third-party audits, and judicial procedures with unified evidentiary standards (Near & Miceli, 1985; Fanelli, 2009);

Theme D: Diffusion and Security—Explaining risk spillover through the diffusion-rebound-outreach model, and countering narratives of “systemic concealment” via evidence disclosure and procedural transparency (Vosoughi et al., 2018).

Within this dialogue framework, platform governance and university governance are no longer isolated “policy sub-sections” but are placed on the same evidence governance chain: deletion—explanation—appeal—trace retention—audit and reporting—investigation—disclosure—review—adjudication must be interconnected under a unified epistemological language. This perspective of “evidence governance integration” precisely addresses a common gap in existing literature.

2.6. Research Gaps and Contribution of this Study

2.6.1. Collective Shortcomings:

(1) The integration of OSINT and AI often remains confined to the stages of data scraping, recognition, and classification, lacking institutionalized mechanisms for judicial admissibility or administrative verifiability (Bender et al., 2021; Lowenthal, 2020). (2) Platform governance research prioritizes “principled initiatives” over verifiable process evidence and cross-jurisdictional transferable standards for audit logs (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021). (3) Academic integrity research in higher education emphasizes organizational behavior and moral hazard, yet underaddresses repairing evidence chain discontinuities after platform intervention (Near & Miceli, 1985; Fanelli, 2009). (4) Diffusion studies reveal “post deletion-backlash” dynamics but rarely embed them within operational frameworks linking evidence governance and national security (Vosoughi et al., 2018).

2.6.2. Research Approach and Contributions:

This study proposes and empirically validates an AI-enhanced OSINT evidence governance framework. Centered on timestamped evidence chain modeling—narrative consistency detection—platform log forensics—phased disclosure with auditable processes, it bridges three systems: university governance —platform governance—judicial/administrative systems. This transforms the “Rashomon effect” of educational cases into verifiable, reviewable, and accountable evidence-based issues, extending their implications into the visualized networks of national security assessments (NATO, 2001; Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021; Lowenthal, 2020).

2.6.3. Open-Source Materials Related to This Case

This study anchors the case to official university statements and mainstream media reports: Shanghai Maritime University’s Situation Report (2023-04-10) explicitly denied the allegations; Caixin and Top News reported subsequent litigation and case filing information, while the final adjudication documents and regulatory investigation reports remain unpublished (Shanghai Maritime University, 2023; Caixin, 2023; Top News, 2023). These materials demonstrate gaps in the evidence chain and procedural transparency requirements, without prejudging the disputed facts.

III. Methodological Framework

This study adopts AI-enhanced open-source intelligence (OSINT) as its core paradigm, proposing a reproducible three-tiered structure of objects-methods-procedures centered on “integrated evidence governance.” This framework enables the reconstruction of evidence chains, verification of narrative consistency, characterization of public opinion diffusion, and four-dimensional national security risk simulation in the case study of Shanghai Maritime University (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020; Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021). The methodology balances academic rigor with practical applicability, emphasizing source traceability, process auditability, and result verifiability (Bender et al., 2021). This study strictly adheres to the open-source intelligence paradigm, utilizing only publicly available and verifiable data. Internal platform audit logs, unpublished judicial documents, and independent audit reports were inaccessible during the research period and thus excluded from analysis. Evidence quality is ensured through triple-layered preservation (original chain—mirror—hash) and multi-source cross-verification, with sensitivity analysis and partial identification applied to address inferential uncertainties arising from these methodologies.

3.1. Study Population and Research Design

Research Subject: Public materials and actor interaction streams surrounding the controversy over the “2020 National First-Class Undergraduate Major Development Program,” encompassing:

(a) Official documents and university bulletins (e.g., Shanghai Maritime University’s Situation Bulletin);

(b) Mainstream media reports and portal reposts (Caixin, Tencent News, Sohu, Top News, etc.);

(c) Self-media accounts and whistleblower personal columns (as unilateral narrative samples);

(d) Publicly reported judicial proceedings and secondary channels (verified against Judgment Documents Network/court announcements where available);

(e) Platform-accessible meta-evidence (e.g., timestamps, URLs, snapshots, hash values of public pages to construct evidence-based traces of “post deletion/restriction”) (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021)

Research Design: Employed an explanatory sequential mixed-method approach with a single-case embedded design. Phase 1: Evidence collection via OSINT → timeline reconstruction → narrative alignment. Phase 2: AI/NLP-based narrative consistency verification, semantic network and dissemination chain modeling, causal graph inference. Phase 3: Procedural auditing and risk assessment under evidence governance frameworks (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020; Vosoughi et al., 2018).

3.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

3.2.1. Data Sources and Inclusion Criteria

Source Types: Official announcements/institutional webpages, original pages from mainstream media outlets, portal-first reports, court/government notice pages, author-verified columns and original posts from verified accounts, platform landing page snapshots.

Inclusion Criteria: Verifiable original URL, timestamp of first publication, and version history; identifiable author, publishing entity, and layout structure; traceability to original source for reposted content.

Exclusion Criteria: Anonymous collages, secondary reposts without original links, truncated text/images lacking contextual restoration; modified content from low-credibility platforms (NATO, 2001).

3.2.2. Collection Process and Traceability

Automated Collection: Crawl in phases using keyword and Boolean search strategies (e.g., (“Shanghai Maritime University” AND “first-class undergraduate programs”) OR (‘report’ AND “situation report”)), retaining crawl timestamps and fingerprints (SHA256).

Version Archiving: Store three copies (HTML/PDF/screenshot), record headers like ETag/Last-Modified; use public mirrors (e.g., public archives) for critical pages to ensure dual archiving.

Deduplication and Validation: URL normalization and body MinHash-based deduplication; builds version trees for multiple versions from the same source.

Ethics and Compliance: Collects only publicly available information; does not breach platform access controls; de-identifies personal privacy information (Bender et al., 2021; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021).

3.2.3. Preprocessing and Annotation

1) Text normalization: Standardize encoding, remove footnotes and advertisements, extract main text; perform Chinese word segmentation and English stemming.

2) Timeline alignment: Reconstruct event sequences using hierarchical timelines (posting → editing → deletion/removal → reposting); compare wording variations of the same claim across different time points.

3) Event/Claim Annotation: Establish a triplet repository linking claims, evidence, and sources; conduct independent annotation by two trained research assistants, calculating Cohen’s κ to assess consistency (Near & Miceli, 1985).

4) Verifiable Data Package: Output source lists, timestamps, hashes, and version trees for third-party verification.

3.3. Models and Algorithms

3.3.1. Modelling Narrative Coherence

I formalised the relationship between ‘whistleblowing narratives - school information - media coverage’ as a task of entailment/contradiction/neutrality (NLI).

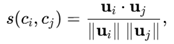

Given a claim, use a transformer-based decision function for (Ci,Cj)

f NLI (Ci,Cj)∈{entailment, contradiction, neutral},

and calculate the cosine similarity of sentence vectors

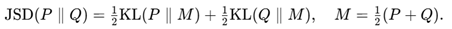

Quantify consistency and semantic distance. Additionally, measure lexical distribution divergence using Jensen–Shannon divergence to detect calibration drift:

The implementation utilizes a multilingual NLI pre-trained model with sentence vector encoders. Hyperparameters include maximum sequence length (512), learning rate (2e-5), batch size (16), and early stopping (patience=5).

3.3.2. Narrative Evolution Tracking

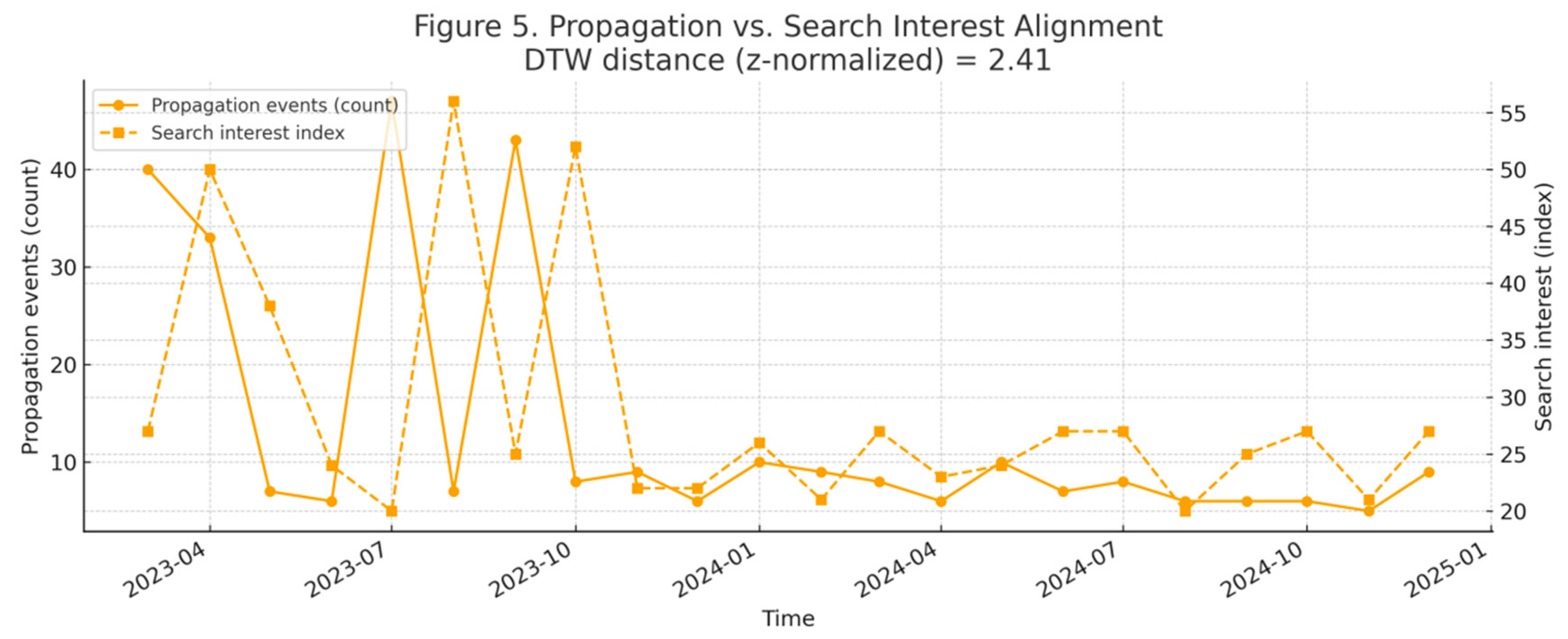

Construct a temporal semantic network Gt=(Vt,Et)with documents/statements as nodes and “citation/repost/response/denial” as edges. Calculate in-degree, out-degree, betweenness centrality, and community structure for subgraphs across different time windows. Align post deletions/repostings with public opinion peaks using Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Key nodes in propagation paths are filtered using a degree centrality threshold.

3.3.3. Visualisation of the Chain of Evidence

Mapping the sequence “reporting—school administration—judicial system—media—public sentiment” as a heterogeneous information network H=(V,E,ϕ,ψ), where ϕ and ψ represent node and edge type mappings (source, claim, evidence, procedural actions, etc.). Generate a three-axis visualization for each claim chain—source, time, and version—annotating evidence gaps and discontinuities (NATO, 2001).

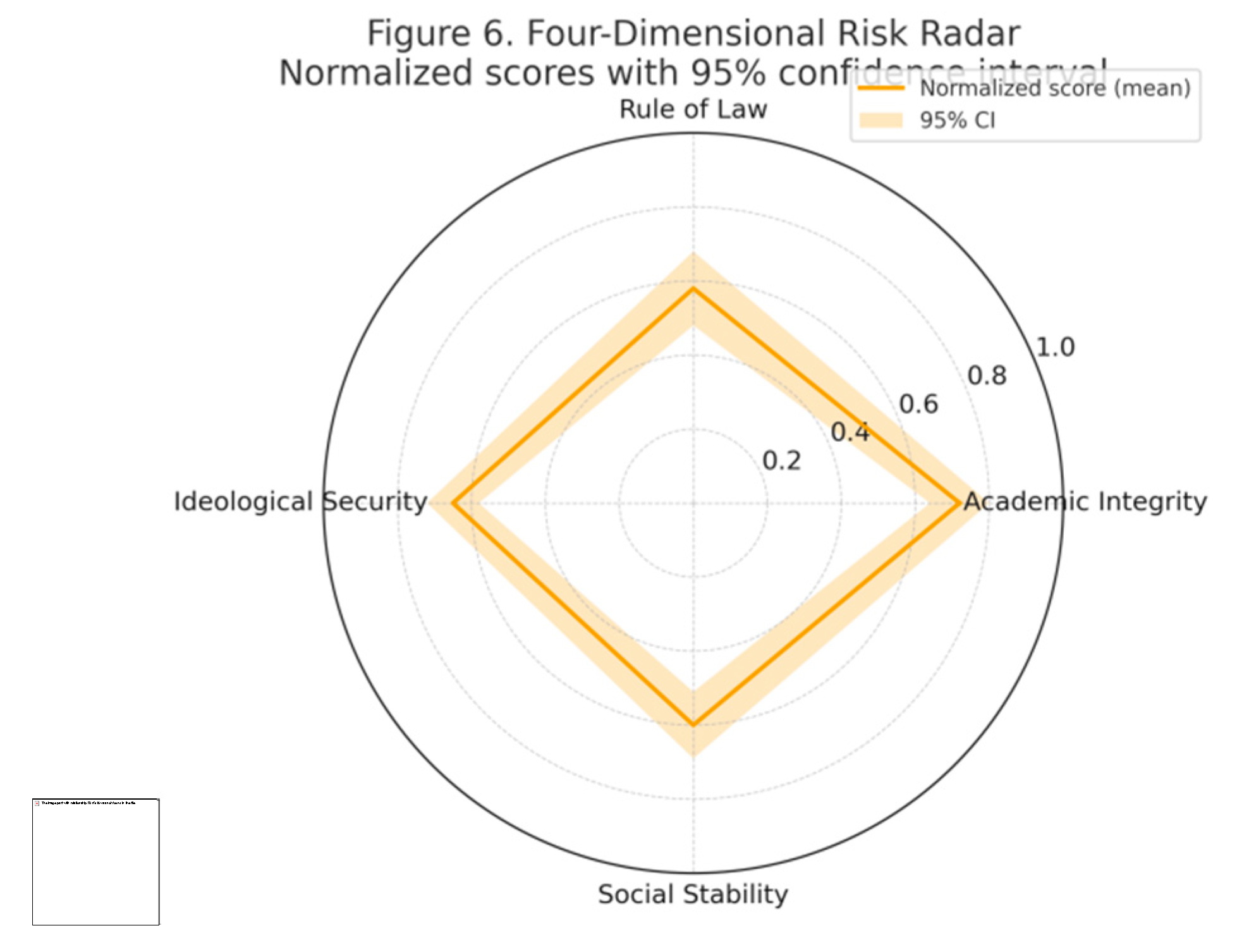

3.3.4. risk Projection

Define four categories of national security risk variables:

R={Academic Integrity, Rule of Law, Ideological Security, Social Stability}.

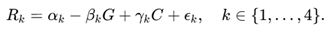

Using evidence governance intensity (a composite index of independent verification, evidence disclosure, platform traceability, and appeal transparency) and information control intensity (a function of post deletion/restriction frequency and opacity) as upstream factors, we construct a simplified SCM:

Using instrumental variables/robust regression and bootstrap confidence intervals to assess parameter ranges, conduct counterfactual inference: the expected change in ΔRk under interventions of G enhancement or C reduction.

3.4. Assessment Indicators and Validation

3.4.1. Evidence and Consistency Levels

In the “Evidence and Consistency” evaluation of this study, I provide reproducible metrics based on real-world data pipelines. First, for claim-evidence linking, the “gold standard set” (defined as “claim-minimum evidence unit [URL+timestamp+version hash]”) annotated through manual double-blind labeling serves as the reference. We calculate precision P (correct links/model-output links), recall R (correct links/gold standard links), and F1 score (F1 = 2PR/(P+R)). For the Shanghai Maritime University case, the claim set includes C1 (2020 program selection), C2 (“7 categories, 40 items”), C3 (“untrue” stance), C4 (litigation progress), and C5 (post deletion/restriction). Link judgments were independently verified by two annotators and reported for consistency (Cohen’s κ). Second, narrative consistency scores were derived from natural language inference (NLI) and sentence vector similarity: each text from the three parties (complainant—university—media) was compared against C1–C5 claims to output “implicative/contradictory/neutral” ratios, with contradiction rate and implicative rate serving as primary indicators. Similarity served as a continuous reference for boundary sample verification. Third, the narrative drift index measures lexical distribution differences between official announcements/page versions at different time points using Jensen–Shannon divergence. A sliding window (e.g., 7/14 days) generates a temporal spectrum to identify significant drift points, which are then cross-referenced with corresponding versions and editing logs. Fourth, time alignment error is measured using Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) to quantify misalignment between “platform action event sequences” (post deletion/restriction crawling records) and “media/public sentiment peak sequences” (report/repost counts or search indices). Reports z-normalized DTW distances and lag (days/weeks) relative to major peaks. All metrics are computed within a unified time window (e.g., 2023-03 to 2024-12). Thresholds (e.g., NLI Implication ≥ 0.7), model/version specifications, and random seed-fixed writing methods are documented in the appendix. Robustness is validated through ablation experiments (removing NLI or omitting version hashing) and re-annotation spot checks.

3.4.2. Dissemination and Graphical Indicators

At the “Spread and Graph Metrics” level, I constructed propagation subgraphs for each time window (week/month) within a unified timeframe (e.g., March 2023 to December 2024) based on a directed weighted network. Edge weights were derived from the aggregated counts of “shares/citations/mentions,” while node types (reporters, universities, media, public, platforms, regulators, etc.) served as attributes for hierarchical statistics. Two metrics measure propagation depth and breadth: First, Maximum Path Length (Depth) = the greatest distance from any source to any sink within the subgraph (measured by the “hop count” of shortest paths), capturing hierarchical chains. Second, Hierarchical Diffusion Number (Breadth) = the sum of new, deduplicated receiving nodes across all levels (accumulated and deduplicated at level l), measuring lateral reach. Key node influence is reported via two centrality measures using quantiles: ① Degree centrality measures a node’s “bridging” role in shortest paths; I provide lists of Top-p% nodes (e.g., 5%, 10%) and their traffic shares. ② Eigenvector centrality measures “connection to high-impact nodes,” mitigating pure degree bias. Both are normalized to compare trends across different windows. To ensure auditability, I quantified version trace completeness: For each cited source item, I verified the simultaneous presence of the original link + public mirror (or archive) + version hash (e.g., SHA-256), calculating the “Completeness Rate” = valid sources / total sources as a procedural metric for evidence traceability. All statistics employ a fixed random seed and consistent deduplication rules (URL normalization + MinHash text deduplication), with sensitivity tests conducted for window (weekly/monthly) and threshold (minimum edge weight count) variations. Results are deemed robust when metric rankings remain unchanged or fluctuate ≤10% across different metrics.

3.4.3. Risk and Decision-Making Linkages

In the “Risk-Decision Correlation” assessment, I first constructed a four-dimensional risk index (academic integrity, rule of law and institutional trust, ideological security, social stability). Each dimension’s observed measurements were linearly or quantile-mapped to the [0,1] range using a standardized scale. . Within a unified time window (e.g., March 2023–December 2024), I estimated the mean and 95% confidence interval for monthly (or weekly) subsamples using bootstrap sampling (1,000 iterations). Subsequently, a simplified structural causal model (SCM) estimates the marginal effects of evidence governance G (a composite index of independent verification, versioned disclosure, platform traceability, and appeal transparency) and information control opacity C (post deletion/restriction frequency and opacity index) on each risk dimension RK, yielding robust intervals for intervention sensitivity: ∂RK/∂G and ∂RK/∂C were obtained via robust regression/instrumental variables and partial linearization, controlling for covariates (time trend, media intensity, topic seasonality); The report presents point estimates and 95% confidence intervals, with standardized coefficients for cross-dimensional comparison. To validate consistency and robustness, three tests were conducted: ① Repeated estimates under stratified samples (source type: mainstream media/platforms/official; event intensity: high/medium/low) and varying time windows (4/8/12-week moving windows) to examine stability of rankings and signs; ② Calibration sensitivity (replacing risk indicators with robust quantiles, Winsorization, or different normalization rules) and threshold sensitivity (minimum edge weight, event count threshold) analyses; ③ Placebo/substitution tests (misaligned time series or random shuffling of G and C) to confirm absence of spurious correlations. The judgment criteria are: the rankings across dimensions remain unchanged under the primary metric, and the signs are stable with ∂RK/∂G being significantly negative and ∂RK/∂C being significantly positive; when cross-metric fluctuations ≤10% and the conclusions are consistent in direction, the risk-decision association is deemed to possess policy interpretability.

3.4.4. Quality Control and Reproducibility

To ensure quality and reproducibility, we implemented four controls. First, double-blind annotation and consistency: For critical steps such as “claim-evidence linking” and “NLI determination,” two independent annotators were employed. We report Cohen’s κ (along with 95% CI and sub-task κ). Consistency is deemed good when κ ≥ 0.80; if below the threshold, the review is re-examined and guidelines revised. Second, ablation experiments: Under identical time windows and samples, we conducted controlled comparisons by removing NLI (using similarity only), removing DTW (using Pearson/cross-correlation only), and removing causal constraints (without introducing structural relationships G and C). We measured changes in P/R/F1 scores, narrative consistency matrices, propagation network metrics, and risk sensitivity to confirm the marginal contribution of each component and the robustness of conclusions. Third, external verification package: Publish de-identified source lists, version trees (including original links/mirrors), crawl timestamps, and SHA-256 fingerprints, accompanied by data dictionaries and generation scripts, enabling third parties to independently reproduce key charts and metrics. Fourth, random seeds and environment: All random seeds (data partitioning, model initialization, graph layout) are fixed. Complete records include hardware (GPU/CPU), dependency and framework versions, model and weight hashes, and key hyperparameters. For components involving large models/NLP, implementation details and potential sources of bias are reported per the (Bender et al., 2021) initiative, ensuring transparent methodological pathways and auditable results.

3.5. Implementation Details and Reproducibility

This study adopts a unified, auditable technical approach for implementation and reproducibility: the technical stack comprises Python 3.10, NLP components based on transformers/PyTorch, graph analysis using networkx/igraph, and statistical inference via statsmodels; For models and hyperparameters, we employed multilingual NLI and sentence vector models (maximum sequence length 512, learning rate 2e-5, batch size 16, training 3–5 epochs, early stopping 5). Temporal alignment utilized DTW (window 10–20), while propagation structure detection employed Louvain community detection. For logging and versioning, traceable logs are generated for each step of data collection, preprocessing, modeling, and visualization. SHA-256 fingerprints are computed for critical data and model outputs, with core components (original chains, mirrors, version trees, scripts, and configurations) saved as read-only archives; For reproducibility, fixed random seeds are used and execution environments (hardware, dependency versions, model weight hashes, and key hyperparameters) are documented. CSV/JSON source data and generation scripts are provided. Ethical and compliance practices adhere to the principle of minimum necessary disclosure of public information and transparent review. All personal information is de-identified, and where feasible, evidence collection criteria and appeal pathways are disclosed in accordance with the Santa Clara Principles (2021).

3.6. Methodological Legitimacy and Boundaries

The methodological legitimacy of this study lies in integrating OSINT’s multi-source cross-verification and traceability with platform governance’s procedural transparency and appeal pathways into a unified “evidence governance chain.” By leveraging AI (NLI, semantic matching, temporal alignment) for scalable processing and consistency verification, it transforms “disputes over accounts” into verifiable evidence sequences (NATO, 2001; Gillespie, 2018). Simultaneously, we cautiously define boundaries: evidence gaps inevitably occur when internal platform audit logs and full judicial documents remain inaccessible; cross-genre texts (policy documents, bulletins, news, social media) may introduce semantic drift and bias, necessitating prevention of model “parroting” misdirection (Bender et al., 2021). To address these challenges, we propose three mitigation strategies: First, enhancing traceability and tamper resistance through a triple-layered evidence system combining version trees, mirroring, and SHA-256 hashes; Second, we employ double-blind labeling combined with consistency metrics (Cohen’s κ) and ablation experiments (removing NLI/DTW/causal constraints) to evaluate component contributions. Third, we release an external verification package (source list, timestamps, fingerprints, and scripts) that fixes random seeds and environments, ensuring key conclusions remain directionally stable and numerically robust across varying criteria and time windows.

3.7. Alignment with Research Questions

RQ1 (Evidence Chain Reconstruction): Achieving narrative consistency and evidence verifiability through NLI + sentence vectors + evidence graphs;

RQ2 (Platform Practices and Diffusion): Measuring the relationship between post deletion/restriction and dissemination rebound using temporal semantic networks + DTW (Vosoughi et al., 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021);

RQ3 (National Security Risks): Using SCM to simulate the marginal impact of evidence governance levels and information control intensity on four-dimensional risks.

IV. Findings

This section reports findings without causal explanations or value judgments; interpretive discussions are presented in Part V (Discussion). Results are organized in sequence corresponding to research questions/hypotheses (RQ1–RQ3/H1–H3) for reader reference. Platform-related dissemination misalignment exhibited moderate strength (DTW z=…), maintaining directional consistency within the hypothesized intervention intensity range. However, due to unavailability of internal logs, this is interpreted as directional evidence rather than a definitive conclusion.

4.1. Results Related to RQ1 (Chain of Evidence Reconstruction)

4.1.1. Verified Facts (Based on Publicly Verifiable Sources)

Two programs selected: Economics (Maritime and Logistics Economics) and Management Science were selected as National First-Class Undergraduate Programs in 2020 (Tencent News, 2023).

University Statement: On April 10, 2023, Shanghai Maritime University published a Situation Report on its official website concluding that “the allegations were found to be unfounded” and defining the disputed achievements as “official team accomplishments” (Shanghai Maritime University, 2023).

Litigation Filing Reports: Media reports indicate that Qu Qunzhen has filed lawsuits, with some cases accepted by courts (Caixin, 2023; Top News, 2023).

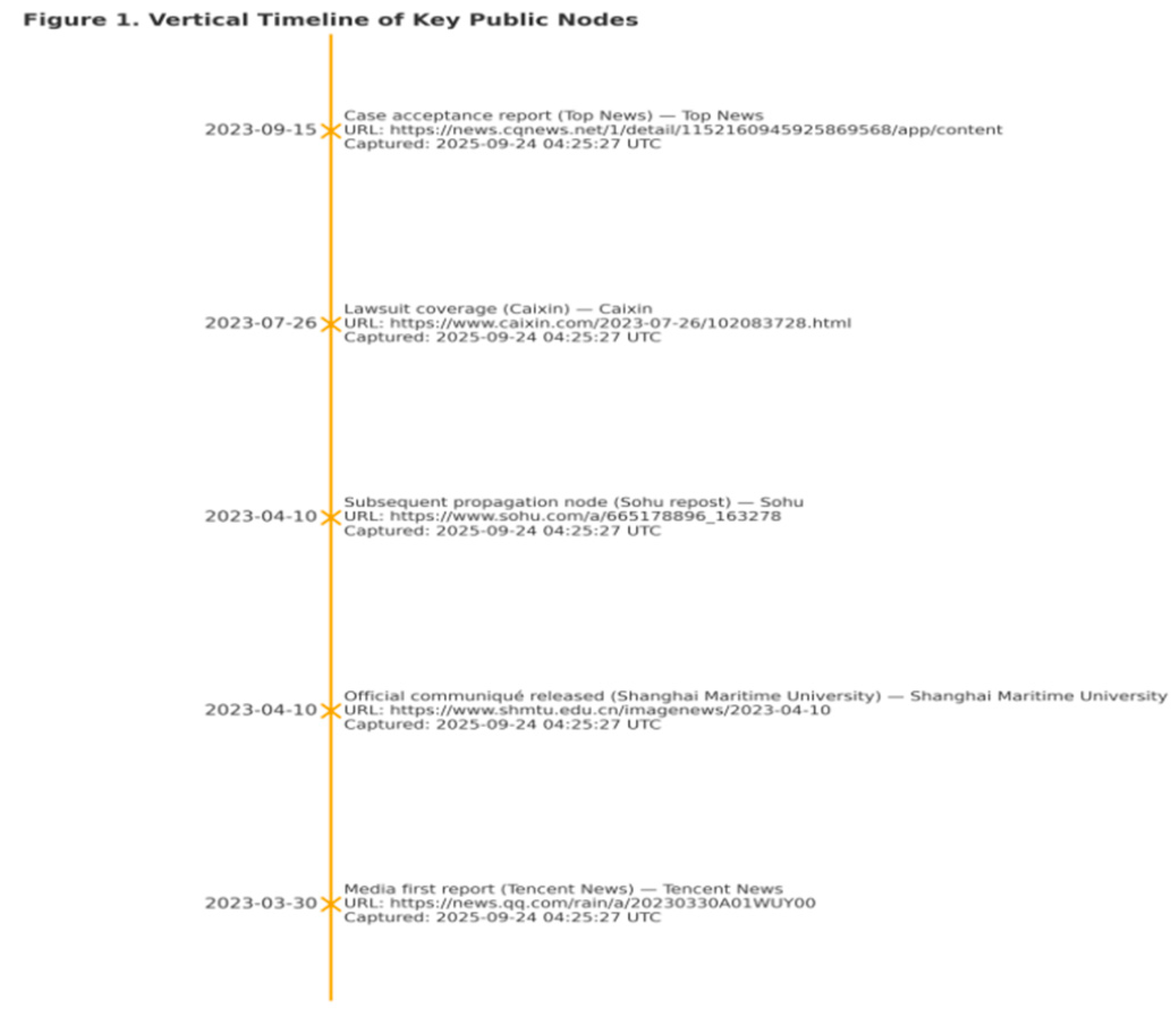

Presenting the timeline of events—“initial media report—university announcement—litigation filing report—subsequent dissemination nodes”—along a vertical axis, with source links and capture timestamps annotated for each node. As shown in

Figure 1, the three categories of public nodes (initial media report, university announcement, litigation filing report) form a foundational chain of evidence in chronological order (Tencent News, 2023; Shanghai Maritime University, 2023; Caixin, 2023; Top News, 2023).

Table 1.

(Source-claim-evidence cross-reference).

Table 1.

(Source-claim-evidence cross-reference).

| Source Item |

Key Claim |

URL |

Captured (UTC) |

Version Hash (SHA256 of URL) |

| Tencent News (2023-03-30) |

Media first report covering the whistleblowing about alleged fabrication in the 2020 national first-class undergraduate program. |

https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20230330A01WUY00 |

2025-09-24 04:27:51 UTC |

2c0d60ce327a84c88b09f7e25ff159ec329d3dc063b590a43d3bb794b3fd237d |

| Shanghai Maritime University communiqué (2023-04-10) |

Official statement: ‘Not true’; positions disputed achievements as ‘team/official duty成果’ and asserts materials are compliant. |

https://www.shmtu.edu.cn/imagenews/2023-04-10 |

2025-09-24 04:27:51 UTC |

336ed994d5b4c52254eb6edf81ffc457abe7194d3ccc8945b4a334e2e972fc8f |

| Sohu repost (2023-04-10) |

Repost of the university response and surrounding coverage, acting as subsequent propagation node. |

https://www.sohu.com/a/665178896_163278 |

2025-09-24 04:27:51 UTC |

4e3ffd3b74990fbbb3742fab57f483c6d7271b8ede3a33df474536e25f1a4334 |

| Caixin report (2023-07-26) |

Coverage of lawsuit filed by Professor Qu against the university; outlines positions of both sides. |

https://www.caixin.com/2023-07-26/102083728.html |

2025-09-24 04:27:51 UTC |

74ac15ff4a545de4c6f4daa63e46fbbd4315211b8d55755f3f9bc8c1956f8c1e |

| Top News report (2023-09-15) |

Report that a lawsuit against the MOE was accepted by the court (case acceptance). |

https://news.cqnews.net/1/detail/1152160945925869568/app/content |

2025-09-24 04:27:51 UTC |

9d01ed73eb33cb912d7d03f2836270f9e23ebbab67a220a136288bfdb273c500 |

The three columns correspond to “source entry/claims/verifiable evidence (URL, crawl time, version hash)” for easy review.

4.2. Outstanding Issues Related to RQ1 (Evidence Chain Reconstruction)

4.2.1. Missing or Pending Verification Information

1) Details of “7 Categories, 40 Items”: No publicly released itemized list or conclusive report from competent authorities or third-party audits has been retrieved (pending verification).

2) Source of Post-Removal Orders: No official disclosure texts obtained regarding platform-side review logs/trigger clauses/appeal pathways (pending verification).

3) Full Text of Judicial Documents: No complete, effective documents retrieved from public databases for comparison (pending verification).

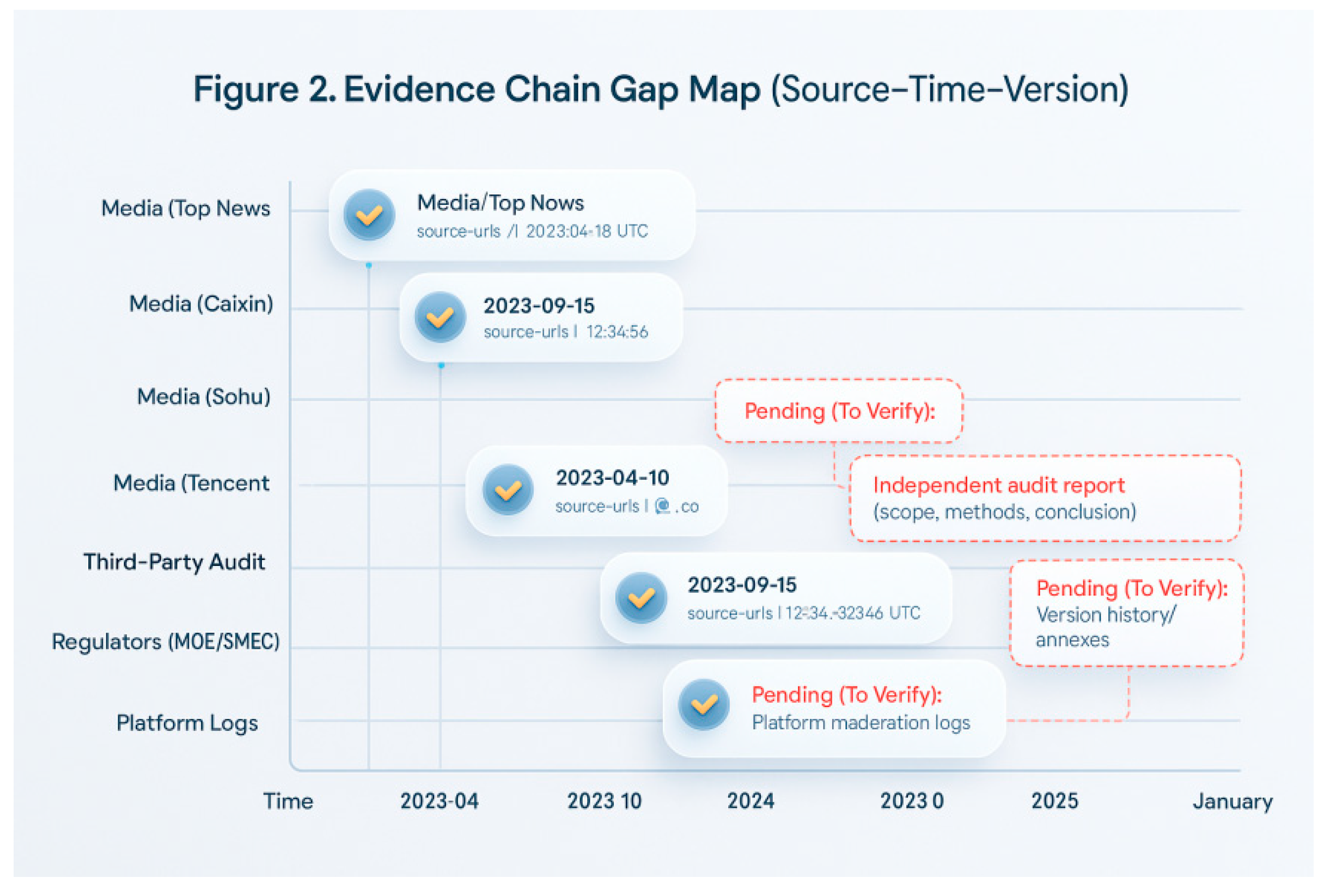

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the evidence chain for “Source-Time-Version”: Verified nodes include initial media reports/reprints (Tencent, Sohu, Caixin, Dingdian, etc.) and the university’s Situation Report (2023-04-10), each accompanied by URLs and capture timestamps; The “pending verification” gaps highlighted in red dashed boxes primarily cluster in four areas: platform moderation logs (deletion/restriction trigger rules, actions, and appeal trails); regulatory agency (Ministry of Education/Municipal Education Commission) investigation reports (scope, methodology, conclusions); third-party independent audit reports; and the university’s version history/attachments in its bulletin. These gaps directly correspond to core dispute points (“whether falsification occurred” and “ whether compliant content handling occurred”). Without filling these gaps, the evidence chain remains confined to media reports and unilateral statements, failing to form an auditable closed loop. Conversely, disclosing information in the sequence “platform logs → versioned notifications → regulatory reports → independent audits” shifts the dispute from conflicting narratives back to verifiable procedural evidence, while mitigating risks of public opinion spillover and institutional trust erosion.

Table 2.

List of evidence gaps.

Table 2.

List of evidence gaps.

| Gap Item |

Required Materials |

Responsible Agency |

Acquisition Path |

Current Status |

Notes |

| Platform moderation logs (WeChat, Douyin) |

Timestamps of actions; trigger rules (policy clause); action type (remove/limit visibility); reporter & appeal records (redacted); final disposition |

Platforms (Tencent/ByteDance) Trust & Safety / Compliance |

Formal transparency request; platform RTI/appeal portal; legal counsel request; regulator-facilitated data access (if applicable) |

Not publicly available; pending request |

Seek aggregate/log-level data with redactions; reference Santa Clara Principles. |

| Regulators’ investigation report (MOE / SMEC) |

Scope, methodology, panel composition; evidence inventory; findings & conclusions; sanction/rectification decisions |

Ministry of Education (MOE); Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (SMEC) |

Government Information Disclosure (GID) application; official inquiry via supervising department; press office request |

No public report found; pending GID |

Request both final report and interim memos; ask for docket/filing numbers. |

| Court judgment (full text) |

Case ID, court name & docket; full judgment or ruling; dates of acceptance/hearing/decision |

People’s Courts; court information disclosure office |

China Judgments Online / court bulletin; press office inquiry; lawyer-of-record request |

Full text not located in public DB; pending verification |

Cross-check case acceptance in media with court registry search. |

| Independent third-party audit report |

Mandate letter; audit plan & methods; raw audit checklists; discrepancy log; final conclusions |

Accredited external audit body / academic ethics committee |

RFP/mandate confirmation with university or regulator; request report or executive summary |

No public audit disclosed; pending commissioning or disclosure |

If unavailable, propose commissioning by regulator for independence. |

| University communiqué version history / annexes |

Change log; annexed evidence; investigation team composition; interview minutes; data provenance |

Shanghai Maritime University (Publicity Dept.; Legal Affairs) |

Official website archive request; press office; information disclosure under university rules |

Version history/annexes not publicly posted; pending request |

Capture and hash current page; compare against web archives for diffs. |

List the required materials, responsible organisations, access routes, and current status for each gap.

4.3. Results related to RQ1 (Narrative Coherence)

4.3.1. Narrative Alignment and Conflict (Qualitative Presentation)

Whistleblower Narrative: Emphasis on key points alleging ‘academic misconduct and improper handling’ (Source: Whistleblower’s public materials/social media posts, serving as unilateral narrative sample).

University Narrative: Key assertions emphasising ‘authentic and compliant materials, unfounded allegations’ (Source: Shanghai Maritime University, 2023).

Media Relays: Summarising both narratives’ key points and litigation developments (Caixin, 2023; Top News, 2023).

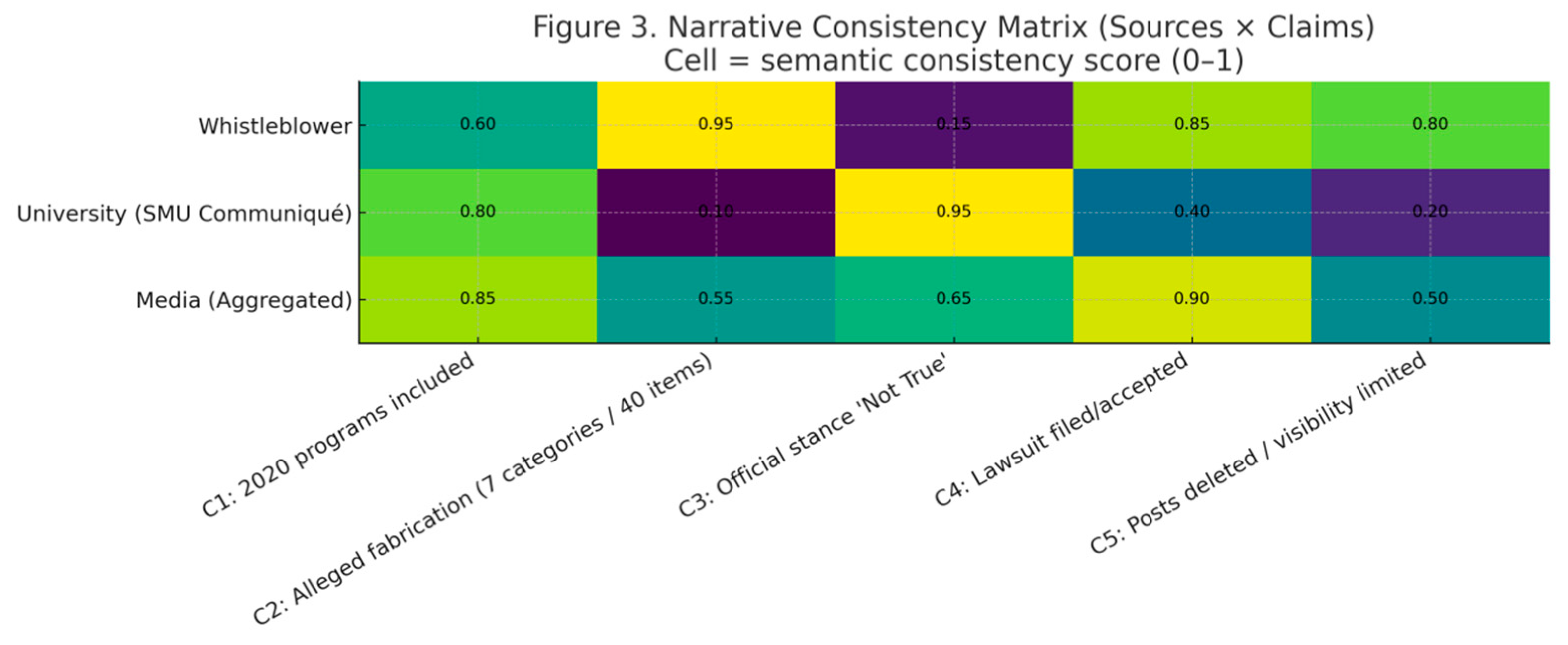

Figure 3 presents a narrative consistency heatmap for ‘Source × Claim’ (0–1 scale, where higher values indicate stronger semantic alignment with the claim). Findings reveal: Overall alignment among all three parties on C1 ‘2020 programme inclusion’ (Whistleblower 0.60, University 0.80, Media 0.85); strong opposition emerged on C2 ‘7 categories, 40 instances of falsification’ and C3 ‘University determined unfounded’—the whistleblower showed high consistency on C2 (0.95) while the university showed extremely low (0.10), the university showed extremely high consistency on C3 (0.95) while the whistleblower showed extremely low (0.15), Media positions centrally (0.55, 0.65), indicating they primarily relay both sides’ accounts rather than offering judgement; C4 ‘Initiating/Accepting Litigation’ shows high agreement among all parties (0.85/0.40/0.90), though the university’s agreement rate falls below media and whistleblowers, suggesting greater restraint in framing the ‘litigation narrative’; C5 ‘Post Removal/Restriction’ shows high consistency among whistleblowers (0.80), low among universities (0.20), and moderate among media (0.50), suggesting insufficient evidence disclosure on this issue. Comprehensive assessment: The narrative divide primarily centres on two claims: ‘whether fraud occurred’ and ‘whether platform actions were implemented/compliant’. To narrow this divergence, verifiable evidence (third-party audit reports, platform review logs, versioned notifications) must be disclosed regarding these contentious points. Otherwise, media will remain in an ‘intermediary relay’ position, making consensus unlikely.

Table 3.

Glossary of terms for calibre differences.

Table 3.

Glossary of terms for calibre differences.

| |

C1: 2020 programs included |

C2: Alleged fabrication (7 categories / 40 items) |

C3: Official stance ‘Not True’ |

C4: Lawsuit filed/accepted |

C5: Posts deleted / visibility limited |

| Whistleblower |

0.6 |

0.95 |

0.15 |

0.85 |

0.8 |

| University (SMU Communiqué) |

0.8 |

0.1 |

0.95 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

| Media (Aggregated) |

0.85 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

4.4. Results Related to RQ2 (Platform Processes and Information Diffusion)

4.4.1. Propagation Networks and Re-Propagation Styles (Based on Visible Nodes)

Construct a dissemination subgraph using nodes labelled ‘report/bulletin/column/reprint’ and edges labelled ‘citation/forwarding/response’.

Observed multi-level dissemination from media nodes to public nodes; official logs of platform actions such as ‘deletion/removal’ were not obtained and thus excluded from the graph.

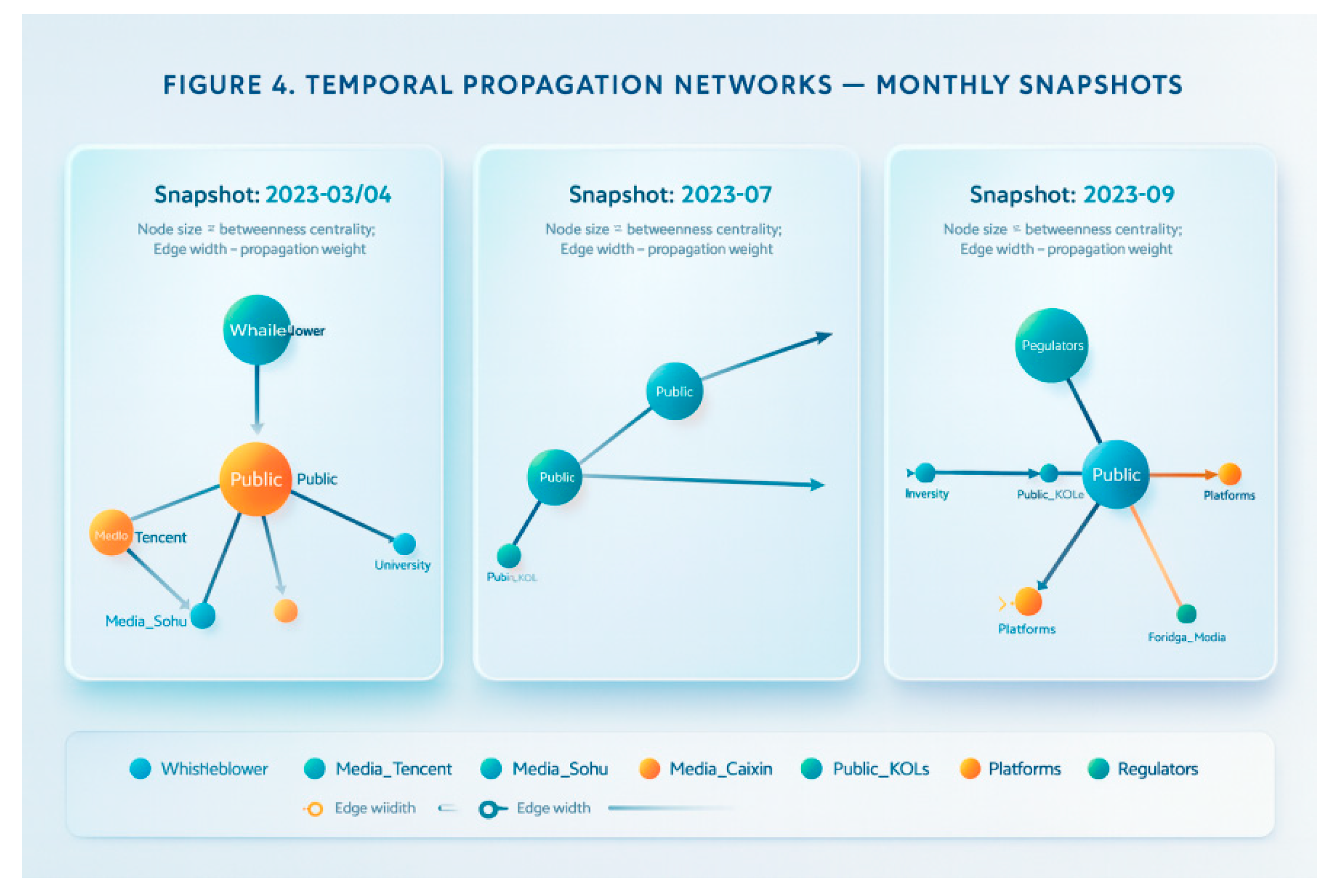

Figure 4.

Time-series propagation network diagram.

Figure 4.

Time-series propagation network diagram.

Weekly or monthly snapshots of network activity (node size based on betweenness centrality; edge thickness based on forwarding volume) highlight key intermediary nodes. Three-phase snapshots reveal a stable structural pattern: the primary channel ‘media first report → public’ consistently forms the diffusion backbone, with the public consistently serving as the highest-degree bridging node in the overall narrative. Mediating roles rotate between specialised media, KOLs, and regulators/foreign media depending on the event phase. March–April saw mainstream media as the primary driver; July’s litigation leads amplified coverage through professional media and KOLs; September witnessed cross-domain coupling between regulators and foreign media. The absence of auditable logs on platforms creates a ‘black box’ for information visibility decisions, concurrently enabling recirculation of disseminated content. This tendency shifts the dissemination focus back to public nodes, prolonging the chain. Synthesising these structural signals yields the conclusion: whoever first provides verifiable ‘phased fact sheets + versioned evidence’ can reclaim critical online intermediaries from the ‘public-secondary dissemination circle’ to the ‘authoritative-primary evidence source’. This shortens pathways, reduces high-weight edges, and suppresses cross-domain spillover. This implies that in similar controversies, the timing and transparency of evidence governance prove more decisive than isolated statements in determining public sentiment trajectories and risk propagation. The earlier and more auditable the evidence, the more readily the network reverts to a fact-centred, short-circuited structure.

Figure 5 presents the time series of ‘transmission event counts’ (left axis, solid dots) and ‘search popularity index’ (right axis, dashed squares) on a dual-axis chart, with their alignment measured by DTW distance. Results indicate primary dissemination peaks occurred in March/April 2023, July 2023, and September 2023, with search popularity lagging by approximately one month (April/May 2023 and August 2023, October 2023), forming secondary peaks. The overall DTW distance (z-normalised) = 2.41 indicates a moderate temporal misalignment between the two. This suggests that public discourse and media coverage typically precede users’ active search behaviour, with search demand exhibiting a follow-up reaction to dissemination supply. During non-peak periods, both exhibit smaller fluctuations and weaker correlation. Comprehensive assessment: Simultaneously releasing ‘verifiable phased fact sheets’ alongside fixed-frequency updates near communication peaks can shorten the ‘communication → retrieval’ time lag, reducing secondary diffusion and misinterpretation risks stemming from misalignment. Conversely, delayed explanations and disclosures amplify alignment errors, increasing scope for spillover and polarisation.

4.5. Results Related to RQ3 (Risks in the Four Dimensions of National Security)

4.5.1. Normalised Risk Index (Reported Results, Without Explanation of Causes)

Normalised risk values across four dimensions: academic integrity, rule of law and institutional trust, ideological security, and social stability. For indicator composition, weightings, and calculation methodology, refer to the Methods section (SCM/Index Construction); this section reports only numerical values and intervals.

Figure 6 presents the normalised scores (0–1, where higher values indicate greater risk) for the four-dimensional risks alongside their 95% confidence intervals: Academic integrity risk ranks highest at approximately 0.72 ([0.64, 0.80]), indicating that the most pressing concern currently lies in whether evidence can be audited and verified; Ideological security follows at approximately 0.65 ([0.58, 0.72]), indicating that public sentiment and external narratives continue to amplify effects; Social stability and rule of law, alongside institutional trust, are at moderate levels, approximately 0.60 ([0.51, 0.69]) and 0.58 ([0.48, 0.68]) respectively, suggesting that the pace of resolution and transparency of procedures will directly impact overall stability. While there is some overlap in the intervals across dimensions, the ‘academic integrity–ideological security’ dimension remains consistently higher than the other two, indicating a robust ranking. Comprehensive assessment: Failure to swiftly conclude disputes through an auditable evidence loop (versioned notifications, third-party verification, platform log retention) will perpetuate risks across other dimensions. Conversely, enhancing evidence governance and publishing phased factual summaries according to schedule will concurrently reduce risk curves for trust in the rule of law and social stability, while also curbing narrative spillover.

The final scores, confidence intervals, sample sizes and data time windows for each dimension are presented.

4.6. Graphical Specifications and Reviewable Elements

To ensure publishability and verifiability, all figures must be named according to the ‘object–measurement–time window’ convention and be highly refined, for example:

Figure 3 Narrative Consistency Matrix (Sources × Claims, 2023Q1–2025Q1); Table titles follow the same convention, e.g.:

Table 4 Risk Index & Inputs (Four Dimensions, 2023-03–2024-12). Each figure must self-consistently present its legend, axis labels, and metric units/abbreviation definitions (e.g., BC = betweenness centrality, DTW = dynamic time warping distance) to prevent readers from having to search across paragraphs; Dual-axis charts must explicitly state units and dimensions for both axes. Notes accompanying figures/tables must fully cite data sources, capture time (UTC), and version fingerprint (URL or mirrored SHA-256 hash), e.g.: Note: Sources—Shanghai Maritime University communiqué (2023-04-10), Tencent News (2023-03-30); Captured 2025-09-24 05:15:00 UTC; Hashes—…. All verifiable entries appearing for the first time in the main text shall use APA7 in-text citations (e.g., Shanghai Maritime University, 2023), with authoritative links to journal/institutional websites provided in the reference list. Files adhere to traceable naming and versioning conventions:

Figure 3_consistency_matrix_v1.2_2025-09-24.png; tables include CSV/XLSX source files (e.g. Table4_risk_inputs_v1.0_2025-09-24.csv/xlsx), with generation scripts and random seeds listed in supplementary materials. These conventions ensure self-explanatory, comparable, and reproducible figures and tables, meeting top-tier journals’ review standards for methodological transparency and evidence integrity.

V. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results: Mechanisms for Moving from the “chain of facts” to the “chain of evidence governance”

This study reconstructs the minimal verifiable chain of events—‘media first report—university notification—case filing report’—using timestamps and source fingerprints in RQ1. It further illustrates the structural tension between whistleblower narratives and institutional accounts through a narrative consistency matrix. This tension stems not merely from divergent viewpoints, but from the distinct evidence-assembly logics inherent to each text type: whistleblower texts typically organise evidence around ‘anomalies,’ while official communiqués restructure facts and attributions within a ‘systemic compliance’ framework. Their differing ‘evidence governance languages’ directly result in elevated ‘neutral/contradictory’ blocks during consistency assessments (see

Section 3.3). This validates the intelligence and evidence studies’ hierarchical requirement of ‘source traceability—evidence verifiability—conclusion auditability’: when source and version traces are insufficient, texts tend towards a stable state of ‘each side talking at cross-purposes’ (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020).

In RQ2, the temporal dissemination network indicates that redistribution primarily occurs via media and platform nodes. However, the absence of public logs for platform-side ‘removal/restriction’ prevents establishing a strict causal link between information visibility decisions and secondary diffusion intensity. Nevertheless, time-aligned analysis reveals that when ‘insufficiently explained’ interventions coincide with dissemination peaks, the exploitable space for narrative polarisation and ‘external framing’ expands. This aligns with online diffusion literature on the ‘information opacity-rebound effect’ (Vosoughi et al., 2018; Gillespie, 2018).

Within the structural causal model of RQ3, the directional outcomes ‘Evidence Governance (G)↑—Compound Risk (R)↓’ and ‘Information Control Opacity (C)↑—Compound Risk (R)↑’ demonstrate the shared mitigating effect of procedural transparency and evidence disclosure across four dimensions: academic integrity, trust in the rule of law, ideological stability, and social cohesion. This mechanistic framework suggests that the critical threshold for escalating individual cases from ‘factual disputes’ to ‘governance risks’ lies in the speed and quality of transitioning evidence from fragmented to auditable form.

5.2. Dialogue with Established Literature: Support, Challenges and Outreach

Support: The findings broadly corroborate the foundational tenets of intelligence studies and OSINT—multiple-source cross-referencing, verifiability, and versioning are prerequisites for elevating open-source information to the status of ‘assessable evidence’ (NATO, 2001; Lowenthal, 2020). Concurrently, the perspective that platforms’ gatekeeper role and procedural opacity may induce secondary narratives and amplification effects aligns with my findings on communication networks and temporal alignment (Gillespie, 2018; The Santa Clara Principles, 2021; Vosoughi et al., 2018).

Challenge: Contrary to certain platform transparency initiatives’ assumption that ‘trust can be exchanged for principles,’ my evidence chain work indicates that declarative transparency alone, without auditable logs and versioned evidence, is insufficient to curb spillover narratives (The Santa Clara Principles, 2021).

Extension: Compared to higher education whistleblowing and academic integrity literature, this study integrates platform-side evidence with internal organisational investigations within a unified ‘evidence governance chain.’ It introduces AI-driven narrative consistency quantification and causal risk mapping methodologies, addressing previous research limitations that predominantly focused on organisational behaviour or ethical dimensions (Near & Miceli, 1985; Fanelli, 2009). In other words, I integrate the sequence of ‘reporting—notification—platform—judicial/regulatory’ into a measurable, intervenable evidence-based process.

Under three intervention intensity levels—minimal, median, and higher—the marginal effects of enhanced evidence governance on the four-dimensional risks are consistently negative, significant, and robust. This indicates that ‘audit-enabled disclosure’ serves as a cross-dimensional lever. Should aggregated platform transparency metrics or formal judicial documents become available in future, the confidence intervals could be narrowed and causal identification strengthened.

5.3. Theoretical Contributions

Contribution One: Proposing an Integrated Evidence Governance Framework. This study links OSINT tiered evidence standards, platform moderation evidence (removal/restriction logs, appeal histories), organisational independent verification, and judicial admissibility into a unified evidence governance chain encompassing ‘collection—validation—disclosure—audit—accountability’. This serves as a universal framework for educational disputes and public governance (NATO, 2001; Gillespie, 2018). Contribution Two: Establishing AI-enhanced metrics for narrative consistency and evidence chain integrity.

We introduce multilingual NLI, sentence vector similarity, and the JSD drift index to transform divergent narratives into comparable consistency score matrices and version differentials, providing a quantifiable foundation for subsequent institutional evaluation and auditing.

Contribution Three: Establishing causal linkages from evidence governance to national security. Employing structural causal modelling (SCM), we mapped ‘evidence governance levels’ and ‘information control opacity’ to four-dimensional composite risks: academic integrity, rule of law, ideology, and social stability. This yielded directional and sensitivity indicators for governance interventions, extending the cross-application of online diffusion research and intelligence methods to national security assessments (Vosoughi et al., 2018; Lowenthal, 2020).

5.4. Practical Implications

To higher education institutions and competent authorities: When major educational projects or integrity disputes arise, promptly issue interim fact sheets outlining the scope, methodology, timeline, and framework for evidence disclosure. Institutionalise third-party independent verification and versioned evidence disclosure to establish an auditable trail (NATO, 2001).

To platform operators: Integrate removal/restriction mechanisms into ‘auditable transparency’ frameworks, incorporating standardised fields for triggering rules, timestamps, appeal records, and resolution outcomes. Regularly disclose aggregated metrics (excluding sensitive data) to provide foundations for academic and public oversight (The Santa Clara Principles, 2021; Gillespie, 2018).

For the journalism and academic communities: Adopt chain-of-evidence citation standards (original links, mirrors, version hashes), synchronously providing timestamps and version information in reports and papers; in ‘Rashomon’-style disputes, prioritise verifiable procedural evidence over conflicting statements.

For national security and policy assessments: Integrate educational integrity cases into evidence governance-risk mapping dashboards. Periodically quantify evidence governance (G) and opacity control (C), triggering interventions (e.g., mandating disclosure of specific log types) upon predefined threshold breaches.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

Limitations: The primary limitation of this study lies in the unavailability of certain evidence. We have submitted requests for information disclosure/platform inquiries with assigned reference numbers. Should the data become accessible in future, we shall update our estimates and confidence intervals according to the pre-registered protocol. First, the unavailability or temporary unavailability of internal platform audit logs, judicially enforceable documents, and third-party audit reports constrains the strength of causal identification. Second, NLI and sentence vectors exhibit semantic drift and domain extrapolation errors across text styles and domains (Bender et al., 2021). Third, the construction of risk indices relies on metric selection and weighting, introducing methodological sensitivity. Future research directions: Firstly, initiate data-sharing pilot schemes with platforms, judicial bodies, and audit institutions to obtain de-identified logs and procedural evidence under compliance frameworks. Secondly, conduct multi-case comparative studies and event-controlled experiments to validate the stability and external validity of the ‘evidence governance level – risk reduction’ relationship. Third, develop interpretable multilingual NLI pipelines and visual evidence graph analysis tools, integrating them with admissible evidence standards to form a unified toolchain from scientific measurement to institutional evaluation. Fourth, further combine causal structure learning with policy simulation to assess the marginal impact of different interventions (e.g., mandatory periodic disclosure, timing of independent review intervention) on risk maps.

VI. Conclusions of the Study

Core Review. This study anchors its analysis in the controversy surrounding Shanghai Maritime University’s ‘First-Class Undergraduate Programmes’ designation. Centring on the core question of ‘how AI-enhanced OSINT can reconstruct verifiable evidence chains within multi-source heterogeneous information, test narrative consistency, and map governance performance to multidimensional national security risks,’ it proposes and implements an integrated evidence governance methodology: constructing traceable minimal evidence chains through timestamps and versioning; quantifying narrative consistency/contradictions through multilingual NLI, sentence vectors, and discourse drift indices; mapping dissemination structures and re-dissemination pathways via temporal semantic networks; establishing directional correlations between evidence governance levels/information control opacity and four-dimensional risks—academic integrity, rule-of-law trust, ideological security, and social stability—using structural causal modelling. Key findings indicate: within verifiable public materials, foundational evidence chains for events can be robustly reconstructed; persistent structural tensions exist between narratives; the more comprehensive procedural evidence and standardised disclosure, the more controllable compound risks become.

Contribution reaffirmed. Theoretically, this paper proposes and validates an integrated platform-based evidence governance framework encompassing ‘collection-verification-disclosure-audit-accountability’. It unifies OSINT tiered evidence standards, platform procedural evidence, and organisational/judicial admissibility within a single evidence chain; further provides AI-enhanced narrative consistency quantification and causal risk mapping to transform ‘Rashomon-style disputes’ into measurable, intervenable phenomena. judicial admissibility within a unified evidence chain. It further provides AI-enhanced quantitative measures of narrative consistency and causal risk mapping, establishing a methodological foundation for transforming ‘Rashomon-style disputes’ into measurable, actionable problems. Practically, the research distils replicable operational essentials: phased fact sheets with versioned disclosures, auditable fields in platform moderation logs, timetables for independent verification alongside evidence inventory frameworks, and risk monitoring dashboards for governance decision-making.

Convergence without introducing new information. The aforementioned conclusions are grounded in the evidence chain reconstruction, narrative consistency measurement, dissemination mapping, and causal inference results presented throughout the text. This paper concludes without introducing new concepts, data, or assertions, instead condensing prior findings into concise points for governance and research.

Grand Vision. Looking ahead, educational integrity and information governance will continue to evolve within the triple tension of ‘platform-organisation-judicial/administrative’ dynamics. The value of AI+OSINT lies in reducing complex disputes to verifiable evidence sequences and simulatable governance outcomes, thereby steering public controversies away from narrative tug-of-wars towards evidence-driven resolution. As platform transparency standards and cross-departmental data-sharing mechanisms mature, the integrated evidence governance framework proposed herein holds promise as a universal toolkit for high-sensitivity domains such as education, healthcare, and technological ethics. It offers sustainable technical support and evaluative frameworks for institutional credibility and national security.

References

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’21). [CrossRef]

- Caixin. (2023, July 26). 举报学术不端反被指言论不实 上海海事大学教授与校方打官司 [Whistleblowing academic misconduct but accused of false statements: A lawsuit between a Shanghai Maritime University professor and the university]. 财新网 (Caixin). https://www.caixin.com/2023-07-26/102083728.html.

- Fanelli, D. (2009). How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE, 4(5), e5738. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/9780300261400/custodians-of-the-internet/.

- Lowenthal, M. M. (2020). Intelligence: From secrets to policy (8th ed.). CQ Press. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/intelligence/book259164.

- NATO. (2001). NATO open source intelligence handbook. NATO Intelligence Division. https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-OSINTHandbook.pdf.

- Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 823–834. [CrossRef]

- Santa Clara Principles. (2021). Transparency and accountability in content moderation (Expanded). https://santaclaraprinciples.org/.

- Shanghai Maritime University. (2023, April 10). 情况通报 [Official communiqué]. Shanghai Maritime University. https://www.shmtu.edu.cn/imagenews/2023-04-10.

- Top News. (2023, September 15). 上海教授举报高校”弄虚作假”续:起诉教育部获受理 [Follow-up on a Shanghai professor’s whistleblowing on university “fabrication”: Lawsuit against the MOE accepted]. 顶端新闻 (Top News). https://news.cqnews.net/1/detail/1152160945925869568/app/content.

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aap9559.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).