1. Introduction

The Roman architectural legacy is significant in many ways and continues to demand in-depth research from experts in various disciplines. Like other building types and in various parts of the Roman Empire, North African Roman residential architecture has mostly been studied from a material and physical point of view (building techniques, archaeological findings, etc.). However, the sensory perspective based on living experience within the Roman built heritage has only recently begun to attract the attention of academics of various backgrounds in the northern provinces, as seen in the works of PLATTS, H. (2022) [

1]and Betts (2017)[

2]. These authors investigated multisensorial experiences within ancient Roman structures in order to reconstitute the authentic “smellscape” and the “soundscape” and other senses of place. These experiences inspired us to extend our investigation of antique Roman architecture in the southern provinces of the empire with a particular focus on the daylight ambience. We highlight light because of its central role in Roman architectural design and its enduring capacity to shape spatial perception [

3].

Addressing this gap, in Roman African province could yield more stimulating results and deepen our understanding of how environmental and cultural contexts influenced sensory experiences across different regions of the Roman Empire. The study of sensorial layers of the past within built heritage enables the exploration of authentic lived experiences. These can be integrated into museum exhibitions to offer immersive and vivid encounters with heritage[

4]. From the academic perspective, sensorial aspects such as light, temperature, odour, and sound are stimuli that can be measured, simulated, and then examined [

5].The results will provide more information about an aspect of Roman built heritage that is less well known within the academic field. This should serve as more accessible knowledge of the luminous ambience of indoor Roman residential architecture.

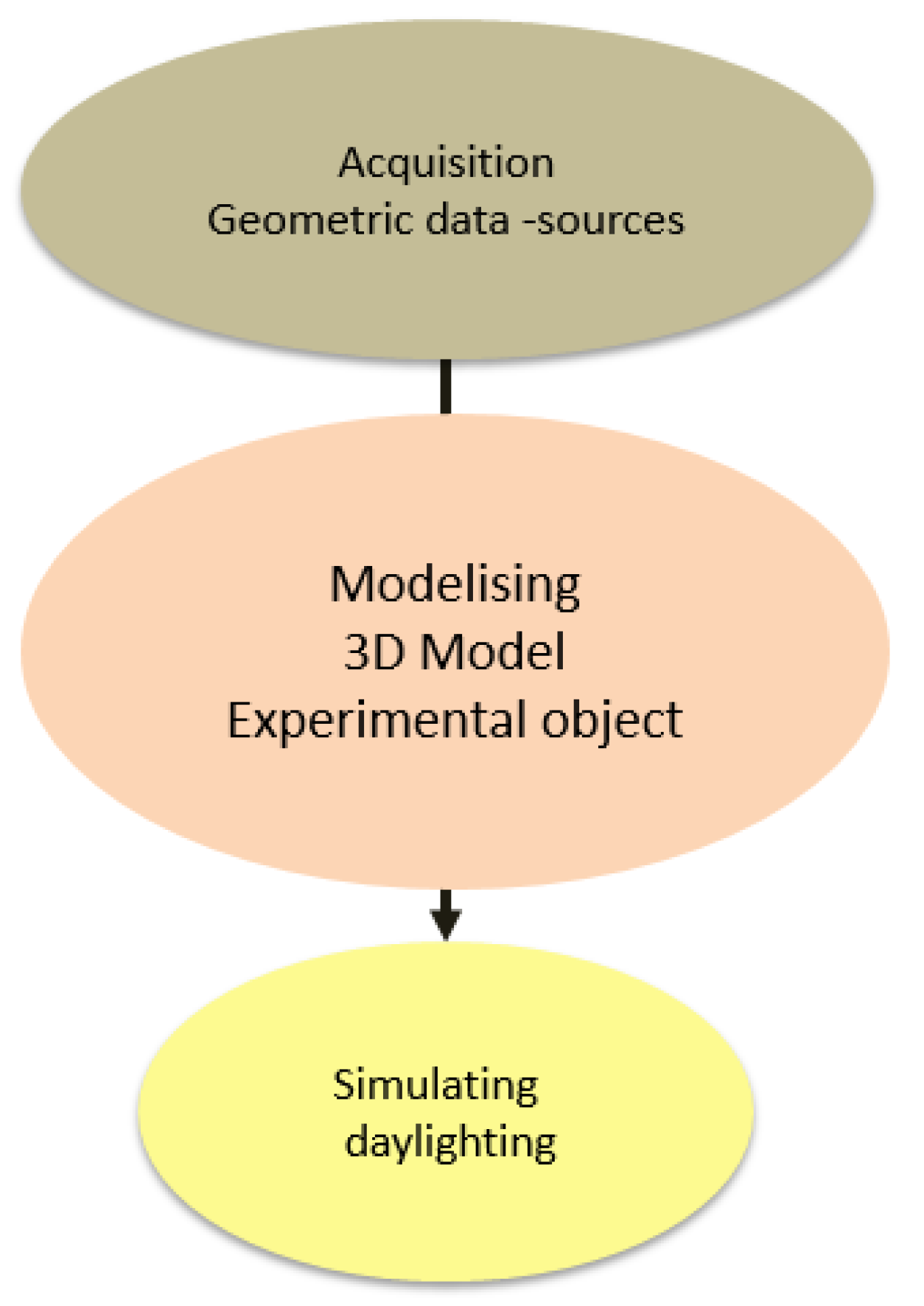

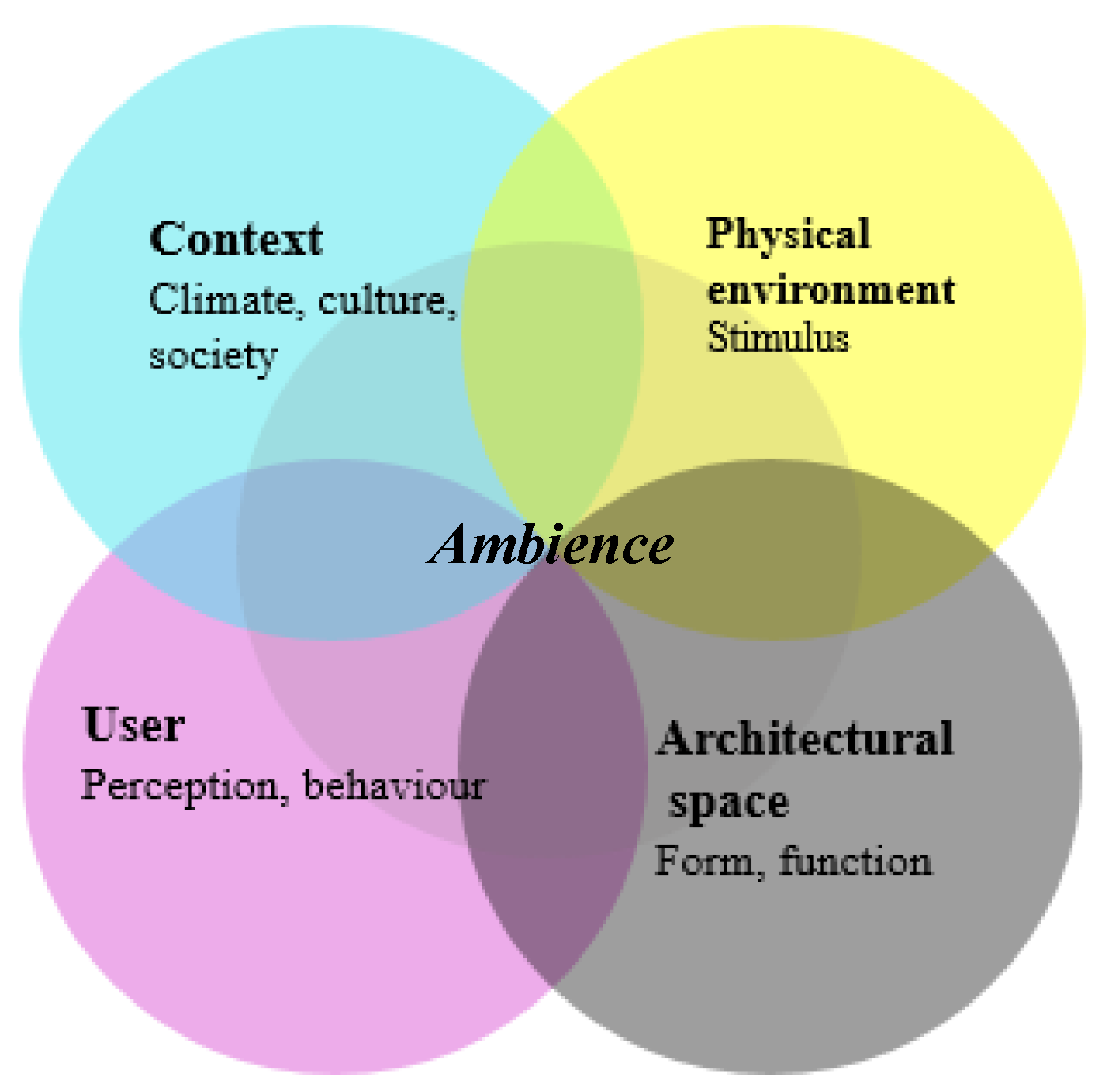

The structure of this study follows an ambience-oriented conceptual model[

6] that guides the analysis and interpretation of sensory dimensions within reconstructed architectural space, focusing particularly on the daytime lighting component.

Due to the multifaceted nature of the concept of ambience, a multidisciplinary approach is essential. The diversity of sources and the variety of targeted outcomes demand the use of specific research techniques. The content analysis is employed to exploit textual and iconographic materials, while digital tools are used for virtual reconstruction and physical environmental simulation.

Given the heterogeneous nature of these data types, they must be expressed and structured in a way that allows for their integration and cross-analysis, enabling meaningful discussion and interpretation of the resulting outcomes.

The ambiences within built heritage

Ambience emphasizes the living experience within a space and associates the physical signals emitted by a place’s various components with users’ senses, mainly based on perceptual and behavioral conduct, while considering the users’ characteristics and their context[

6].

A conceptual model of “ambience” was previously constructed in order to encompass the various and interrelated dimensions shaping it in urban and/or architectural spaces. It is composed of the four following main components [

6](

Figure 1)

- -

The Context: This includes the cultural, social, and climatic factors that enclose the architectural space. The context provides the broader environmental and societal background against which the space is experienced.

- -

The Architectural Space: This component focuses on the architectural characteristics, specifically the form and function of the space. Proportions and materials play a crucial role in shaping its ambience.

- -

The User: This component focuses on the human experience, considering the perceptions, behaviours, daily habits, and interactions of the users within the architectural space.

- -

The Physical Environment: This relates to the sensory stimulus present in the space, including heat, air, light, sounds, and odours.

At the present time, contemporary heritage studies increasingly emphasize the need to preserve the “heritage ambience” — a concept that encompasses the authentic sensory and experiential aspects of historical sites, which are often altered by the demands of modernity and urban development [

4]. Similarly, the concept of “heritage ambience” involves a holistic approach that recognizes the “spirit of place,” which is shaped by a complex interplay of material and immaterial elements related to the previously cited conceptual model’s components. These elements served to investigate several heritage ambiences during various historical eras and geographical contexts.

As revealed by these previous research works, when operationalizing the conceptual model of heritage ambience, the major problem faced is the current inexistence of ancient users who could express their sensory experiences as they lived in historical buildings, especially in very old ones, as in our case study[

4].

Indeed, it is very rare to find buildings that retain their ancestral lived experiences. Thus, collective memory, travel narratives, novels, and iconographic and cinematographic sources, such as paintings, mosaics, and even films, constitute the sources from which it may be possible to uncover the sensory experiences of the past.

Furthermore, historical buildings and monuments are often subject to natural evolution, and their ambiences change as well. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct monographic research on these buildings to define the conformational characteristics under study. Moreover, the disappearance of significant fragments of buildings and their current state as ruins require their virtual reconstruction, both in terms of their conformational and ambient aspects. Digital reconstruction is one of the most reliable methods for achieving this [

4]

2. Heritage and Virtual Reconstruction

Over the last few decades, virtual reconstruction has gradually become a major tool in the field of heritage conservation. It plays an important role not only in preserving cultural heritage but also in its promotion through media, cultural activities, and tourism [

7]This is mostly due to its ability to create immersive and interactive experiences, helping people to engage more deeply with historical sites.

A good example is the reconstruction of the Roman burg at Saalburg in Germany, where the visitors are able to understand the space by exploring its physical features, historical background, and the memories linking it with real historic objects, events, sounds, clothes, and odors, such as lively culinary and tasting experiences. This helps establish a long-term emotional connection with the place.

In some cases, these reconstructions also touch on spiritual or even mystical dimensions, sometimes referred to as “hauntings”, as in the work of [

8].

Another interesting application of virtual reconstruction is in the study of buildings that no longer exist. This approach allows researchers to analyse them in an experimental way, considering different aspects such as architecture, environment, and atmosphere. For example, Asma, A. (2018) carried out a study focusing on the restitution of lighting and thermal conditions in a modernist housing estate designed for extreme desert climates. To explore the design intentions behind these homes, she created virtual models, which were then used to run simulations. These tests helped to better understand how the houses performed, especially in terms of indoor lighting and thermal comfort [

9]

In addition to environmental analysis, several studies have looked into how people perceived space within Roman domestic architecture. Simon Ellis (2007), for instance, virtually reconstructed the interior of a Roman dining room (in the Oil Mill House) to study its night lighting environment[

3]. In a similar way, Campanaro and Landeschi (2022) examined how people experience a virtually reconstructed Pompeian house, focusing on how it feels to move through and observe the space. The team used a mixed-methods approach combining the analysis of real user experience and virtual reality through the creation of an immersive environment[

10].

The virtual reconstruction of architectural heritages of the past not only involves the reconstruction of a silent historical object but also makes possible the study of the sensations provoked by the arrangement of its spaces, its volumes and furnishings, and its uses and rituals of life, without missing the environmental conditions of its situation.

Virtual reconstruction is considered a promising technology in the heritage sector. However, in many scenarios, virtual reconstructions outside of the disciplines related to the study of architectural heritage have been carried out spectacularly, revealing significant flaws in terms of scientific rigor.

For this reason, virtual intervention in built heritage must be based on a well-defined historical and methodological approach. Indeed, there are no clear and universally accepted rules governing virtual intervention in heritage. This leads to the obvious conclusion that these critical criteria should be based on the principles guiding all scientific work: observing and analyzing data, generating hypotheses that explain these observations, and, finally, verifying the validity of the hypotheses raised[

11].

3. Methodology

This research work is conducted within the framework of the previously presented conceptual model of ambience mentioned above and its four constituting components: (1) context, (2) architectural conformation, (3) the user, and (4) the physical environment. We begin with the contextual dimension, wherein we define the specific characteristics of the southern provinces. This includes an examination of geographical and climatic conditions, natural and cultural features, locally available materials, and traditional construction practices.

Given the vast territorial extent of the African province, our investigation is focused on the city of Timgad, which provides an exceptionally well-preserved and comprehensive example of Roman urban planning [

12]. Our study centers on the residential domain, and we have selected the House of the Raised Flower Beds as our case study. This dwelling is particularly relevant as it embodies the African adaptation of the Roman peristyle house—a typology integral to regional architectural identity.

We next address the second component of the conceptual model of ambience—architectural configuration—in which we utilize the virtual reconstruction technique by means of digital tools to develop a three-dimensional experimental model through the use of Archicad Graphisoft (2023). The work began with an in situ examination and architectural survey.

The unique existing documentation of the house was provided by a French architect of historic monuments, Albert Ballu. It provided literary descriptions, ancient photographs, and drawn essays of the restitution [

13]. The outcome is a 3D reconstruction that not only visualizes the house but also provides a better understanding of its design and generated atmosphere.

Subsequently, we addressed what we consider the most vital element in the conceptual model of ambience: the users of the space, along with their habits and perceptual experiences.

In the absence of contemporary users, we proposed a figure of a hypothetical visitor. A virtual, predictive scenario was developed, drawing upon ancient Roman rituals and practices documented in the historical literature.

Yet, the notion of a generic ‘virtual user.’ Presents a significant methodological issue. we fully acknowledge that lived experience is inherently subjective. It is actually impacted by many factors such as identity, status, gender, and occupation. variables that are difficult to reconstruct in a complete and interactive way. To move beyond this constraint and provide an analytical rigor, our study shifts its framework from speculating on individual, subjective feelings to analyzing the objective architectural framework that structured such experiences.

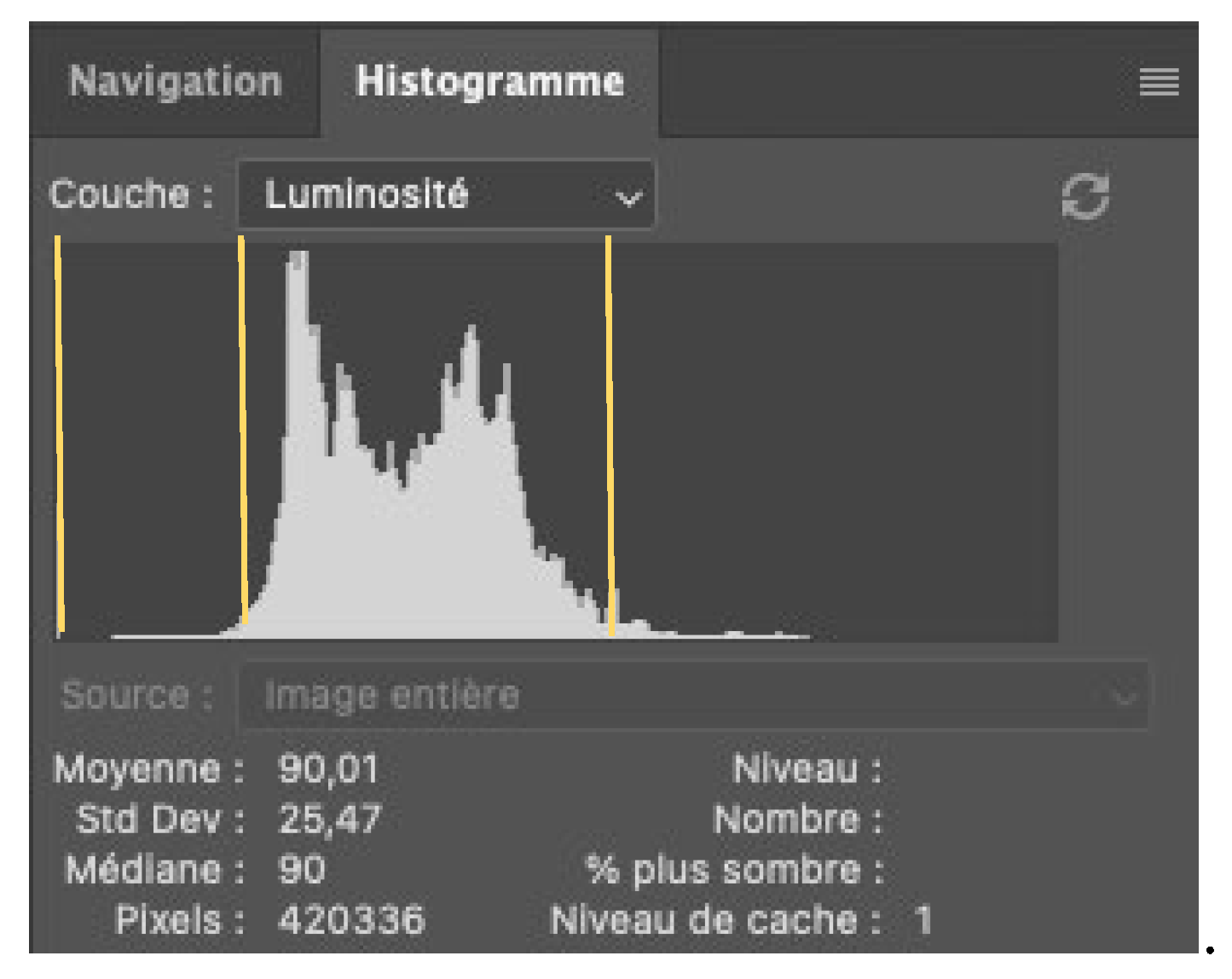

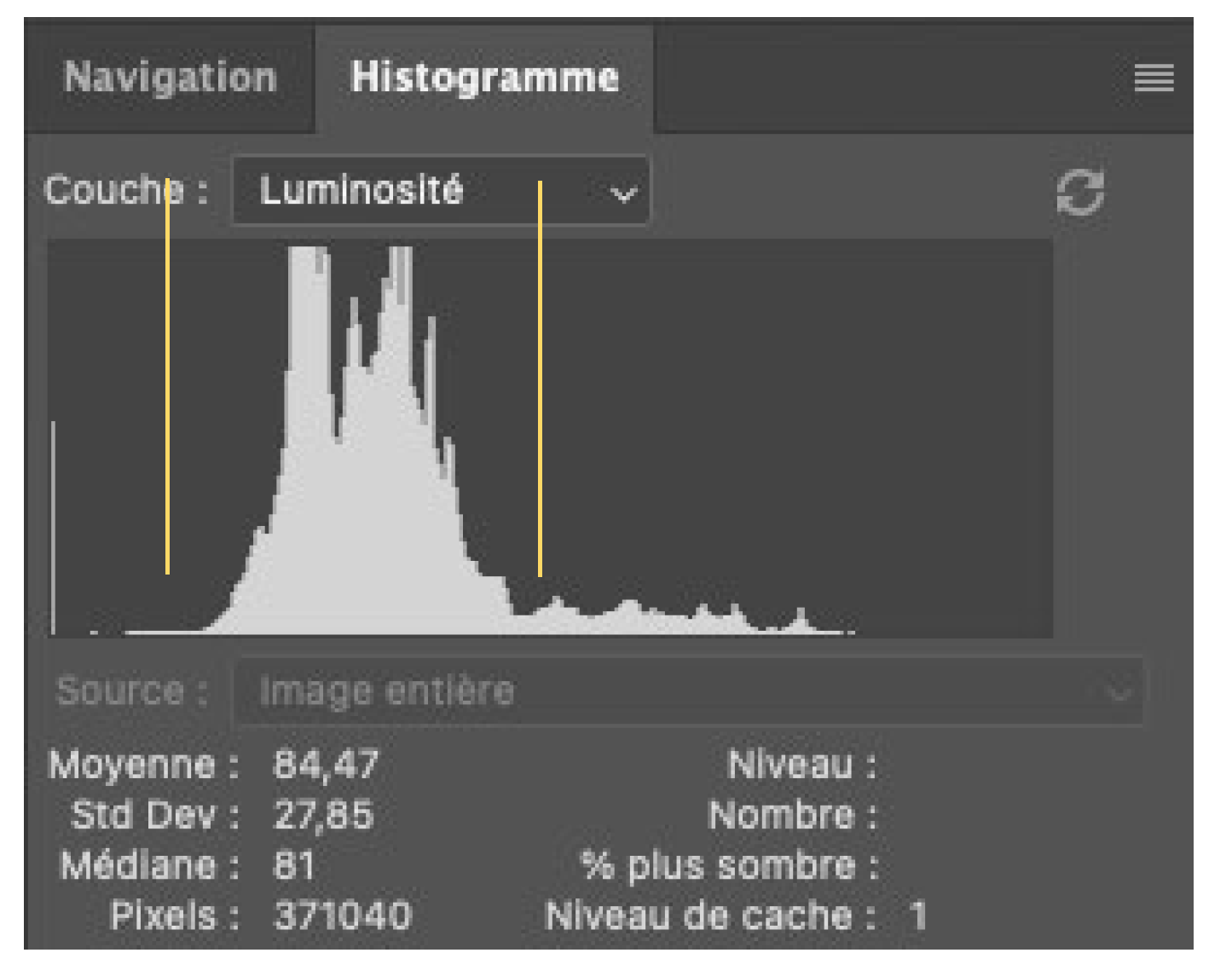

Finally, the physical environment to be examined is daylight. This is examined and visualized based on rendered images of the 3D reconstructed model by using the ray-tracing engine integrated in the software (Archicad, 2023). Daylight is qualified in images primarily by analyzing their contrast and brightness through histograms. We used a method developed by Demers to discuss lighting ambiences in architecture[

14] and combined the results with the user experience.

Given the state of deterioration of the remains and the poor documentation of this house, we were not able to find all of the evidence necessary for a reconstruction with a high level of accuracy. Notably, the wall coverings, the location and size of the windows, the floor mosaics, and the vegetation of the flower beds could attest to the originality of the house. Nevertheless, we had to adopt an analogical and interpretative method based on comparable houses in the same context or even in other regions of the empire when necessary.

Another important limitation concerns the reflectivity of materials, especially mosaics and wall plastering. Although a large variety of textures and reflectivity can be demonstrated by rendering software, there remains a recognized lack of scientific observation regarding the reflective properties of Roman surfaces. It is currently unclear to what extent Roman mosaic floors and wall surfaces were polished to enhance their shine or the intensity of their colors[

3]. In light of this uncertainty, we chose to work on white model renderings, which allow the visualization of volumes and geometries with light topologies and shades.

Content analysis was employed as a valuable research technique at all stages. First, it allowed us to extract rich descriptions of sensory experiences, spatial behaviors, and representative figures from various sources, including literary texts, paintings or frescoes, and mosaics.

Beyond that, it provides a meaningful point of reference, helping us compare our virtual results with historical depictions and assess how closely our model aligns with what might have been the lived reality of the time.

3.1. Domestic Sensory Environment Through Literary Texts and Iconography « Overview »

Whatever the results of a digital reconstruction may be, they need to be discussed and interpreted with respect to real perceptive experiences through literary texts and iconographic traces (mosaics, paintings, and sculptures). The study of sensory perception within Roman domestic environments is a complex and multifaceted domain that requires extensive and multidisciplinary research[

1]. In this overview, we aim to demonstrate how Roman literary sources have informed us about aspects of ambience and sensorial experiences within household interiors by drawing on select textual examples.

Literary sources serve a dual and significant function. First, they enable the construction of mental images of Roman houses, especially concerning their spatial and physical characteristics. Bergmann (1995), for instance, highlighted this interpretive potential when visualizing Pliny’s villas through his texts, referencing authors such as Vitruvius, Varro, Pliny, and Columella, whose writings support the reconstruction and reimagining of lost architectural structures, including the Villa of Pliny[

15].

Secondly, textual sources allow us to access representations of sensory experience as they were perceived and described in specific spatial and temporal contexts. Roman texts frequently refer to sensory stimuli—light, sound, color, and odor—depicting how these elements shaped lived experiences within domestic settings.

For example, In the North African context, Apuleius of Madaura, in Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass) [

16], offers further valuable sensory descriptions. In one passage (p.53), he describes the oppressive outdoor heat and the house as a place of cool refuge. On page 63, he portrays a luxurious interior: “

What she now saw was a park... a palace had been built, not by human hands but by a divine craftsman... coffering of the ceiling was of citron-wood and ivory... the walls were covered in embossed silver... the floors divided up into different kinds of pictures in mosaic of precious stones... even the doors radiated brilliance.”

Such descriptions provide a rich narrative on textures, light, materiality, and human sensory experiences about domestic architecture . The semantic analysis of these textual fragments offers the possibility of quantifying the frequency and diversity of references to sensory stimuli[

17]. These data can be cross-referenced with archaeological and digital reconstruction findings to develop a more nuanced picture of domestic ambience in Roman antiquity.

3.2. Iconographic Sources

Iconographic sources, such as mosaics and frescoes, further enrich this reconstruction. These visual materials are no longer regarded as mere decoration but as substantial elements with representational and symbolic significance; they often depict scenes from daily life, material culture, rituals, and even sensory phenomena[

18].

For example, the Mosaic of the Overturned Basket, preserved in the Sousse Museum (Tunisia), portrays a part of the Salutatio ritual involving the offering of gifts (xenia ).

The imagery evokes several indicators about the ambience, olfactory and tactile stimuli—the smell of fish, the texture of wicker baskets, and the freshness of water.

Figure 2.

Mosaic of the overturned basket, the museum of Sousse Tunisia, photograph author.

Figure 2.

Mosaic of the overturned basket, the museum of Sousse Tunisia, photograph author.

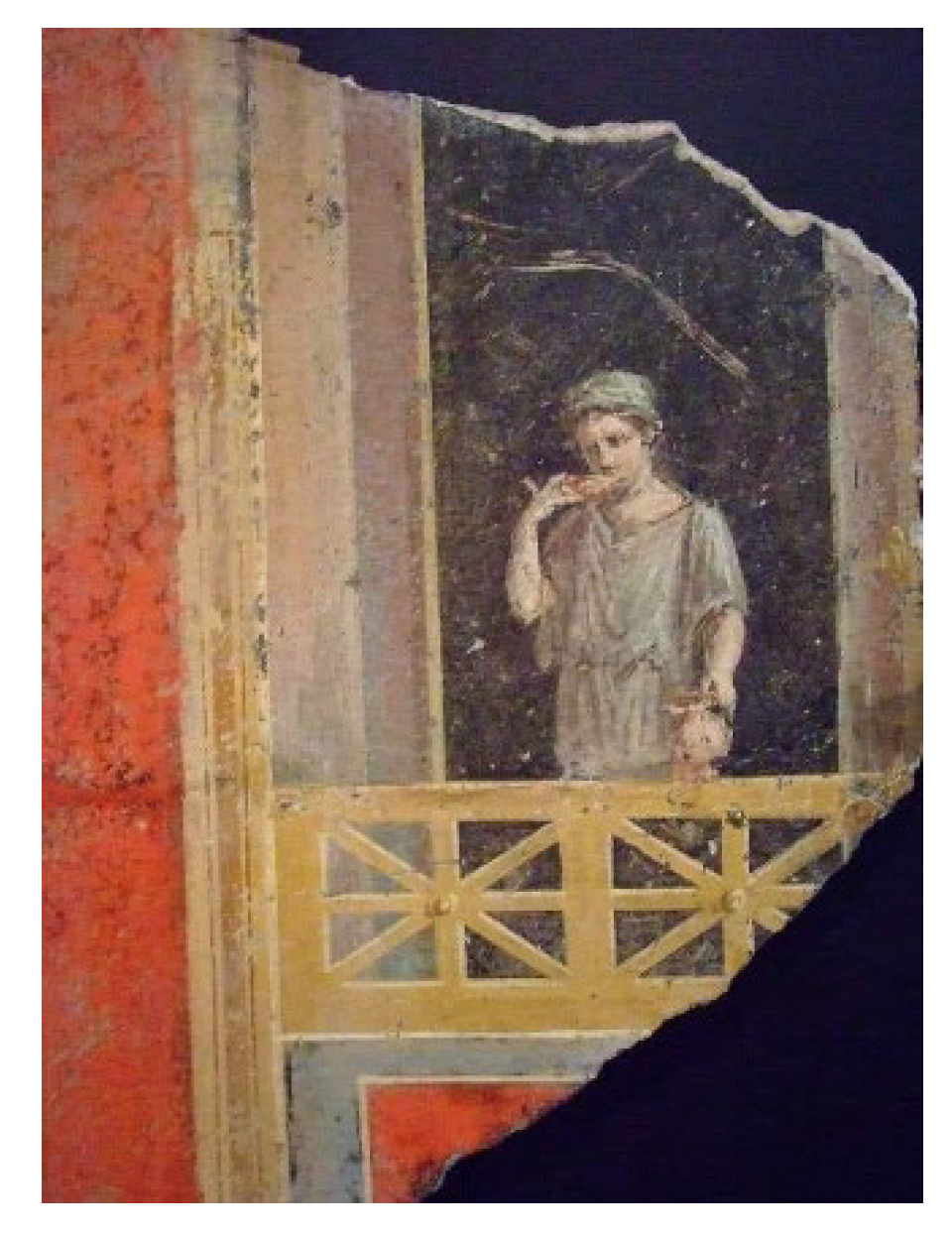

The second iconographic support is paintings. Pompeii encompasses the most preserved ones. Paintings are generally found in situ, covering the walls of houses. They reveal much evidence about the physical and sensorial components of a house. For example, the fragment appearing in

Figure 6 shows a female standing on a balcony, contemplating exterior views, while the interior space seems relatively gloomy and insufficiently lit.

4. Context of the Study

As a first step, the object of the study −the residential architecture−, is defined within the context of the North African Roman provinces. This setting illustrates a distinctive context shaped by both environmental conditions and local cultural traditions through the ‘fusion of Roman, Carthaginian and indigenous influences’[

19]. One of the most representative cities in this context is the city of Timgad. It is located in the northeast of present-day Algeria, on the northern slopes of the Aurès Mountains. It was founded at the end of the first century CE by Emperor Trajan as a military colony intended to house veterans of Roman legions.

Figure 7.

The situation of Timgad in the African Province,from Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons by-sa-

3.0 de, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118060035.

Figure 7.

The situation of Timgad in the African Province,from Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons by-sa-

3.0 de, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118060035.

Strategically situated at the edge of the Sahara Desert and near the intersection of several major trade routes, Timgad quickly developed into a significant center of commerce and culture. The original city covered an area of approximately 11 hectares (27 acres) and featured key civic structures, such as a forum with a curia, an imperial temple, and a basilica.

Between the second and fourth centuries, the city expanded beyond its original orthogonal layout. This period of growth saw the addition of new temples, public baths, and an enlarged civic center that included luxurious residences, a library, and a new market area.

Timgad was laid out according to a strict orthogonal plan resembling a chessboard, oriented along a north–south axis[

12].

Figure 8.

The plan of the antique Roman Timgad city, Batna Algeria, From [

20]

©British institute of Lybian and Northern African studies.

Figure 8.

The plan of the antique Roman Timgad city, Batna Algeria, From [

20]

©British institute of Lybian and Northern African studies.

Cagnat (1909) emphasized Timgad’s significance as a case study for the diversity and evolution of Roman domestic architecture in North Africa[

21].

The building materials used in Timgad were extracted from nearby quarries, and they included brick, rubble, a variety of marbles, limestone, and notably, ashlar stone, which appeared in three main types:

-Sandstone, quarried locally, was used for general construction, secondary street paving, and wall surfaces of residential and monumental buildings.

-White limestone was employed in finely carved architectural elements such as capitals, bases, cornices, column shafts, friezes, and honorary inscriptions.

-Blue limestone, a particularly hard variety, was used primarily to pave the forum, major monuments, and the principal roads.

Two roofing systems were prevalent: timber structures supporting terra-cotta tiles, remnants of which have been found on-site, and vaulted ceilings covered with terraces composed of coarse mosaic tiles[

22].

At a second stage, the litterature review related to the Roman domestic architecture revealed that such kind of structures showed a wide typological variety, including domus, villas, and insulae in the context of the North African Roman province [

23]. In this study, we focus on the urban domus within the city walls, particularly the residences of the elite. These houses are more robust in construction and status and have been comparatively better preserved than the modest dwellings built for the lower classes, making them more accessible to scholarly interpretation[

24]

A number of studies have analyzed Romano-African domestic architecture based on archaeological evidence. Gsell (1920), for instance, highlighted the influence of Hellenistic models on North African Roman houses, noting the replacement of the atrium with an open-air peristyle [

25]. Rebuffat (1969) further asserted that the term “atrium” was rarely applicable in Roman Africa, being reserved for references to impluvium/compluvium arrangements, and that it was functionally and spatially supplanted by the peristyle or porticoed courtyard[

23].

Ellis (1994) reaffirmed the widespread presence of essential Roman domestic features—specifically, “a peristyle and a reception room opposite the entrance”—throughout the Empire by the end of the first century CE[

26]. Carucci (2007) offered a spatial analysis of North African houses that further supports the thesis that Romano-African domestic layouts were influenced by Greek architectural traditions, particularly in the centrality of the peristyle [

27]. This observation aligns with Vitruvius’s prescriptions for dwellings in southern climates[

28]. The peristyle remained the core organizational feature of the house—a space through which the owner’s public life unfolded and social status was articulated[

29]. Environmental and cultural factors of the context significantly influenced residential design, resulting in a fusion of Roman architectural principles with local African building practices.

5. Case Study: The House of the Raised Flower Beds in Timgad

The house of the Raised Flower Beds is located in Timgad’s main central district; its main elevation faces north and slightly to the west. It is restricted to the north by the Decumanus, to the south by the basilica, to the west by the public restrooms (Latrina), and to the east by a cardo and the eastern marketplace.

Figure 9.

Location of the house of the raised flower beds n° 11, reproduced by Author from [

20] ©British institute of Lybian and Northern African studies, photograph by Author.

Figure 9.

Location of the house of the raised flower beds n° 11, reproduced by Author from [

20] ©British institute of Lybian and Northern African studies, photograph by Author.

The historical sources indicate that its construction dates from the Good Era (“la bonne époque”), implying a period of high architectural quality [

21]. There is no precise date mentioning the construction of the house, which is located at the northeastern corner of the buildings forming the forum and its annexes in Timgad; therefore, its construction date can be linked to the construction of the forum, as well as the founding of the city of Timgad.

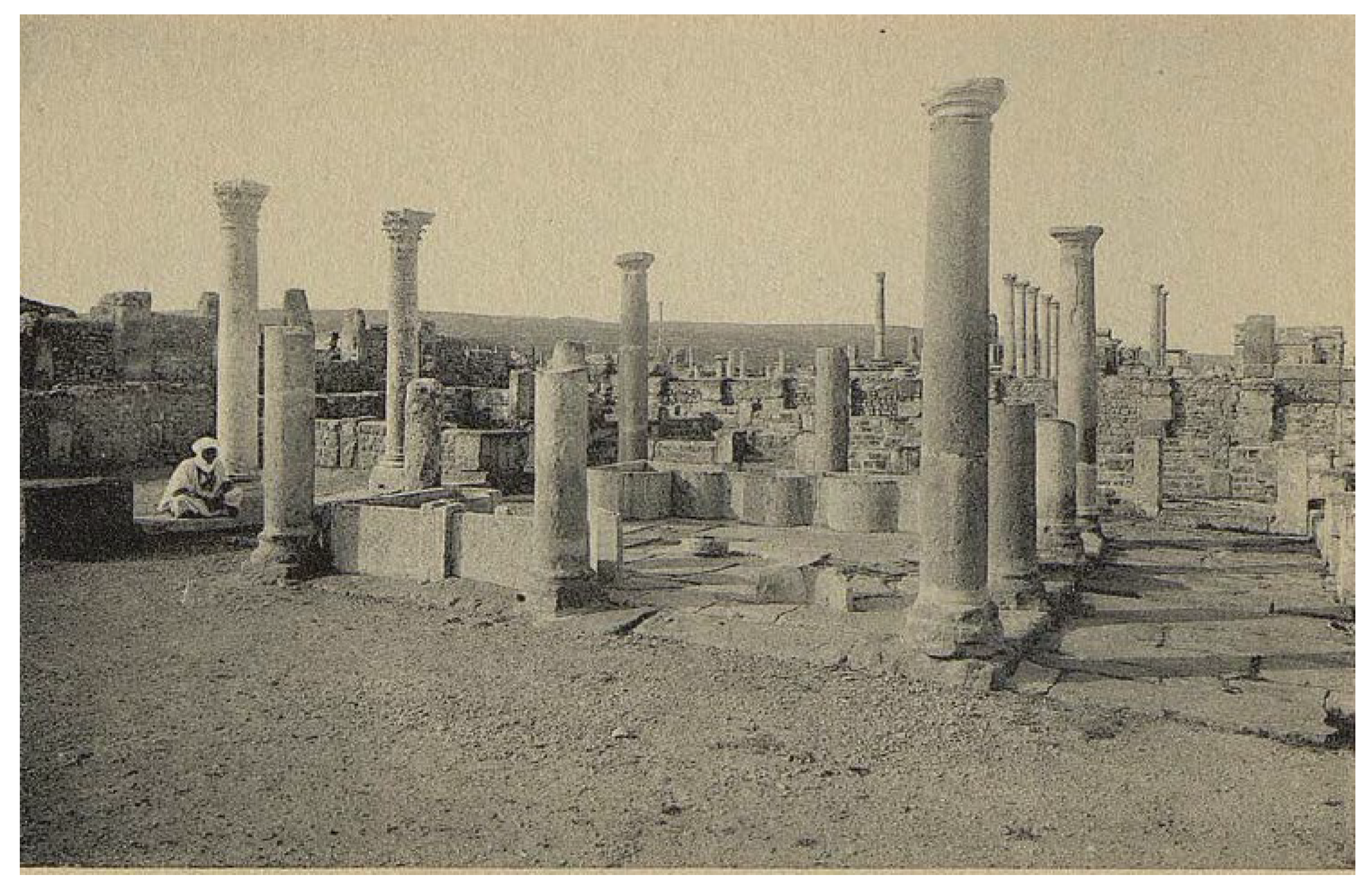

Excavations at this site were conducted in 1892 by Albert Ballu. At the time of discovery, the remains of the house were in a severely deteriorated condition, with only the stone uprights—once integral to the original masonry—still standing.

Initially referred to as the “House of the Forum” due to its proximity to the forum[

30], the residence was later renamed “La Maison aux Jardinières” by Ballu himself, in reference to the elegant planters that adorn the central courtyard—elements that, remarkably, retain their original form to this day.

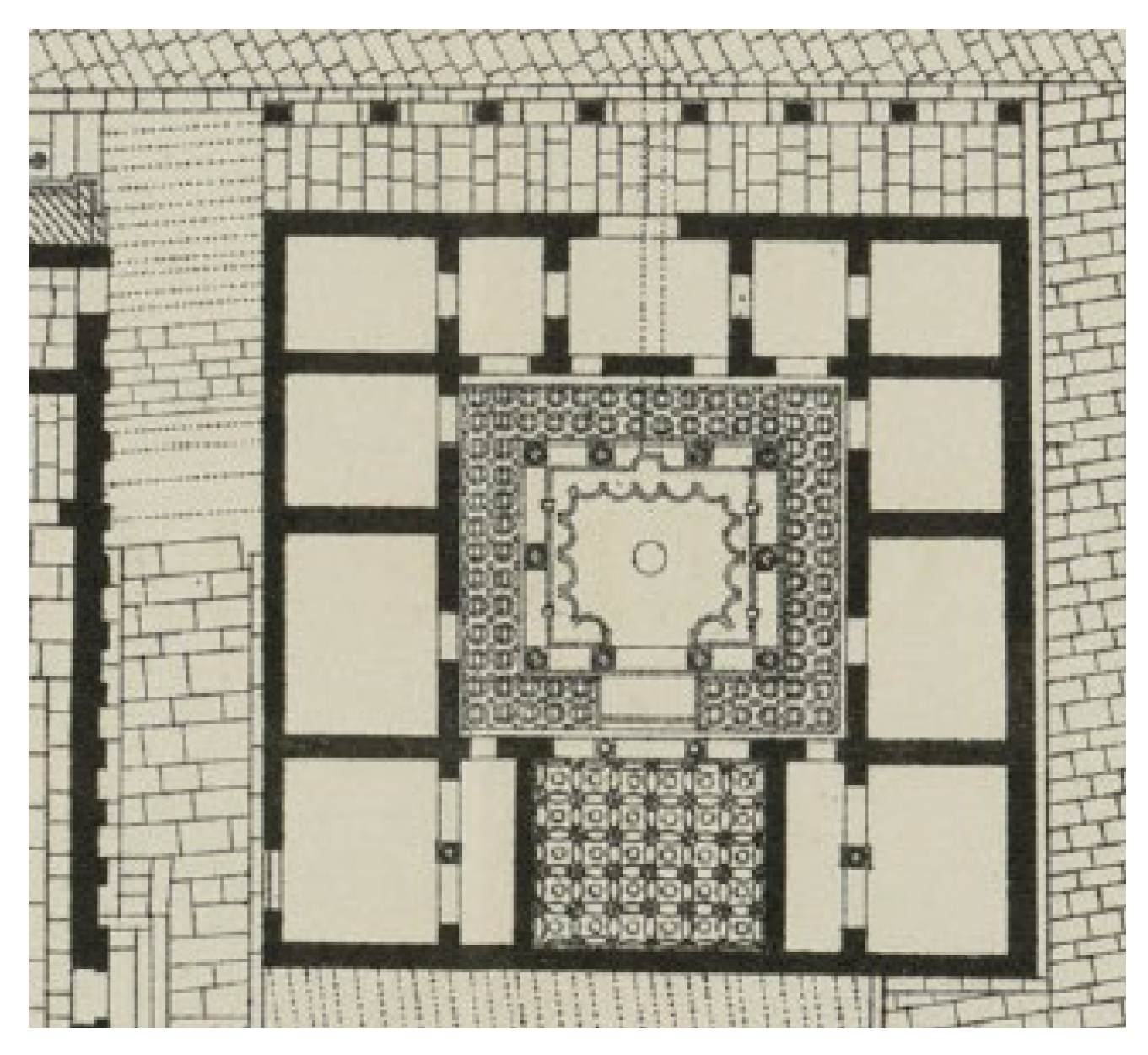

Figure 10.

Ballu’s drawings, before anastylosis works reproduced by Author from[

31]© cc creative commons digitized by universitat bibliothek Heidelberg.

Figure 10.

Ballu’s drawings, before anastylosis works reproduced by Author from[

31]© cc creative commons digitized by universitat bibliothek Heidelberg.

5.1. Previous knowledge related to the House ...

The House of ... was mainly investigated by the French archeologist Albert Ballu during the French colonial era. The data extracted from his studies allows to: i) enhance our knowledge about this house’s conformation, ii) collect the required components for its virtual restitution, and then iii) founding the identification and charcaterization of the ambiences prevailing inside.

Albert Ballu described the house as having a nearly square plan, with the rooms organized around a central peristyle composed of ten columns. Ballu indicated the presence of two-faced masks, which were expected to be fixed at the top of the corner columns of the courtyard, contributing to the decorative scheme. At the center of the peristyle, a well was also located, indicative of domestic utility.

Opposite the main entrance lies a large reception room—identified as the Tablinum—which opens directly onto the peristyle. Flanking vestibules provide lateral access to an additional interior room, suggesting a deliberate spatial hierarchy within the layout.

Building materials were tailored to the structural and aesthetic requirements of each architectural element and built with the African opus. The columns, crafted from white limestone, are executed in the Corinthian order, reflecting both regional materiality and Roman stylistic preferences. According to Germain-Warot (1969), the mosaics were badly damaged. The floor is adorned with intricate mosaics. According to Germain-Warot (1969), the mosaic composition integrates geometric patterns with refined vegetal ornamentation, rendered in a restrained palette dominated by shades of yellow and brown [

32]. The works of Albert Ballu at the end of 19

th century were the unique and the last interventions in the house. He initiated anastylosis operations to restore fragments of the building’s elements, bringing the house to its current state.

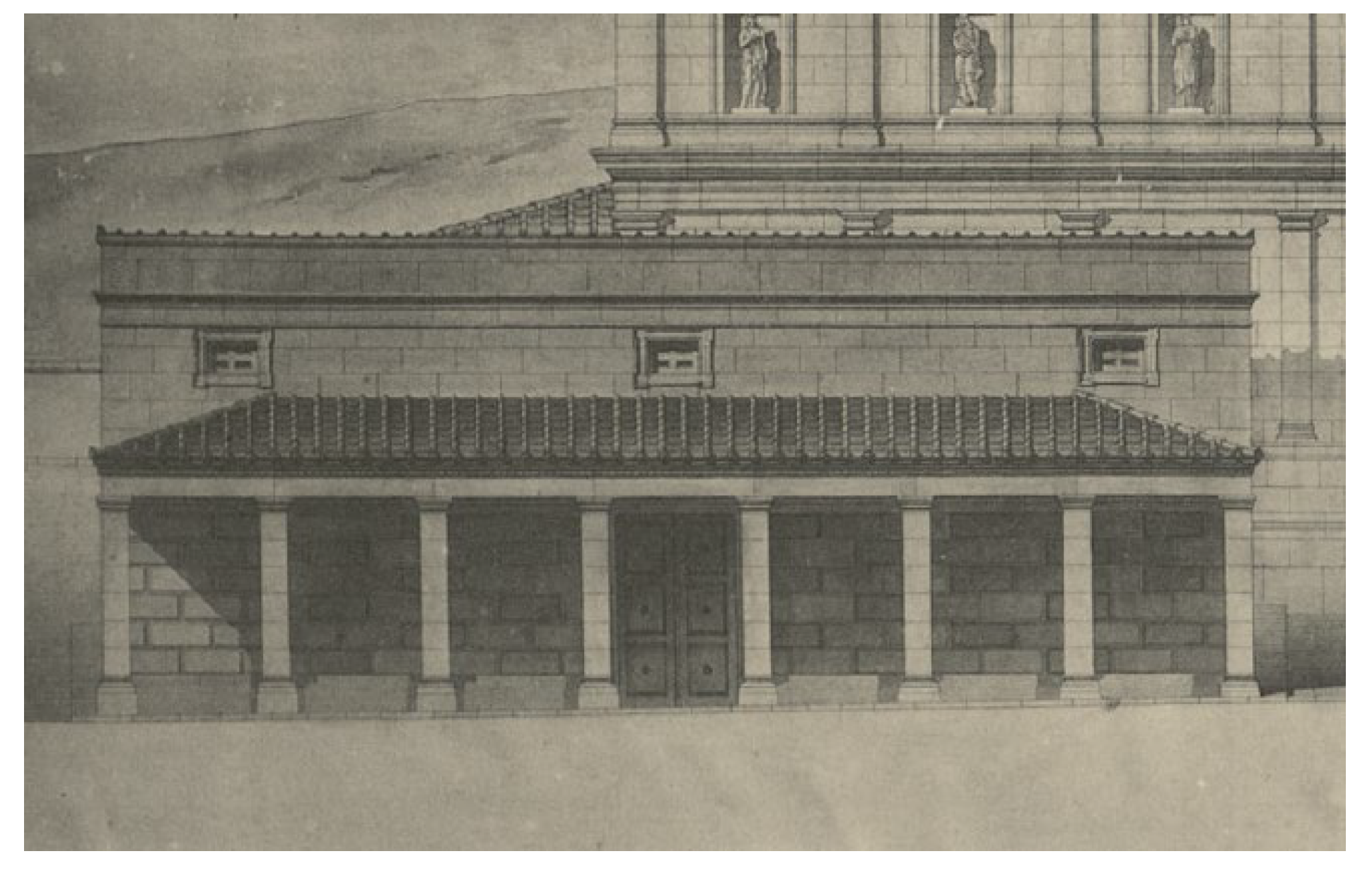

In addition, he developed a 2D graphical restitutions of the plan and main façade of the house.

Figure 11.

The plan’s restitution of the house of the Raised flower beds,[

13]© public domain.

Figure 11.

The plan’s restitution of the house of the Raised flower beds,[

13]© public domain.

Figure 12.

The graphic restitution of the main elevation of the house of raised flower beds[

13]©public domain.

Figure 12.

The graphic restitution of the main elevation of the house of raised flower beds[

13]©public domain.

Figure 13.

Photograph of the House of Raised Flower Beds,Author collection[

22] ©public domain

.

Figure 13.

Photograph of the House of Raised Flower Beds,Author collection[

22] ©public domain

.

Albert Ballu’s work for this house remains an essential starting point for our work, which uses the documentation of the initial state of the ruins during his excavations, in addition to the partial restoration of the house in a case study, as well as the graphic restitutions. Ballu’s work focused primarily on the physical preservation of the buildings, while our work is a continuation of this, using computerized virtual reconstruction tools.

6. The Virtual Reconstruction of the House of the Raised Flower Beds:

Our virtual reconstruction of the conformation of the house

of the Raised Flower Beds, developed with digital tools, adheres to the principles of the London Charter [

33]. The Charter’s emphasis is on respecting intellectual and technical transparency through the definition of the degree of reliability based on existing evidence. The absence of authentic tangible indications about the realistic shape of the house reduce inevitably the degree of reliability in our reconstruction. Nonetheless, the purpose of this research work is to produce the most hypothetically accurate virtual model possible of the house. One that enables the study of daylighting ambience as well as physical and sensory effects inside.

In addition , we examine ancient textual and iconographic sources relevant to Roman domestic architecture. In addition, an analogical interpretative approach is used to extract evidence from well-preserved houses in the North African context, such as the Maison Africa in Thysdrus and the hunting house of Bulla Regia (present Tunisia), and even in other provinces, especially Pompei, such as the house of the Vettii built in 60-79AD (Rodríguez-Moreno, 2020).

The Digital process

The architectural survey (Acquisition)

After the examination of the current state of the site and the analysis of available sources, we conducted an architectural survey to acquire geometric data. A campaign of measurements and photographs of what remains of the built environment was undertaken. The remaining built environment includes the basement of the load-bearing walls, which are 50 cm thick and made of cut stone rubble. The height is one meter at most. We identified eight Doric columns in a critical state of conservation surrounding magnificent built planters in the central courtyard, as well as two Corinthian columns at the entrance to the reception room.

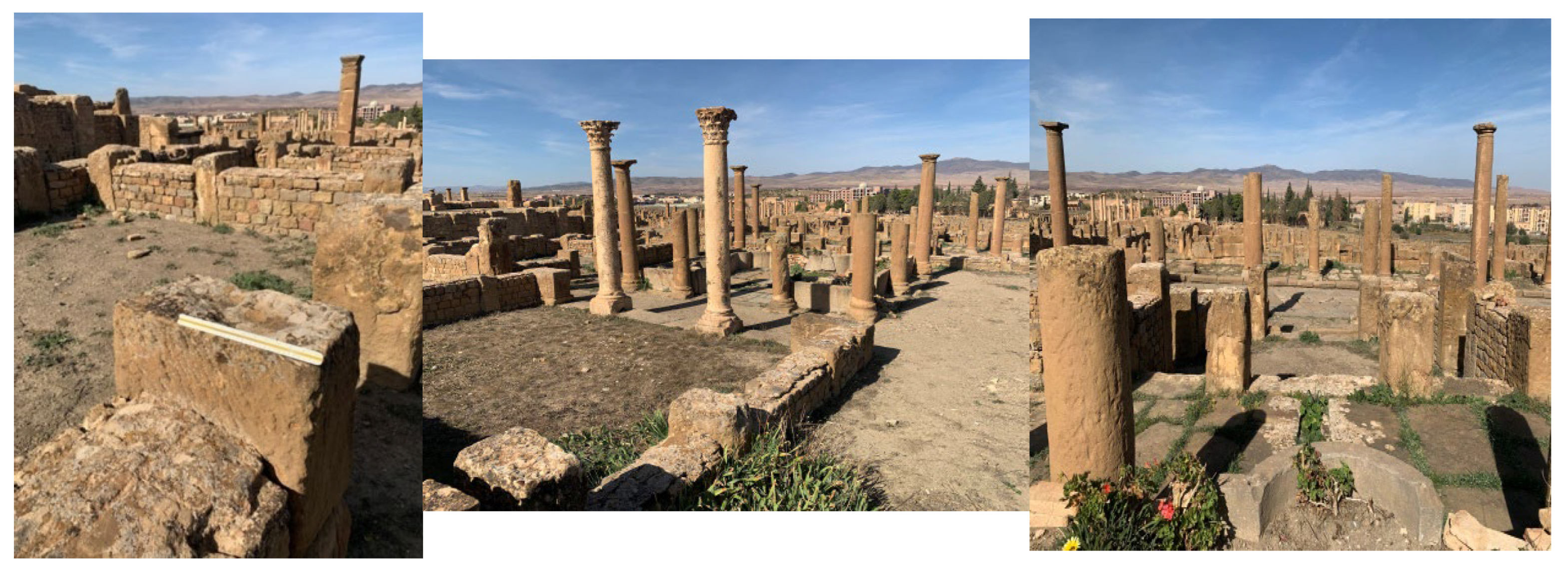

Figure 14.

Schema of digital process, source Author.

Figure 14.

Schema of digital process, source Author.

Figure 15.

Recent photographs of the remaining vestiges of the House of Raised Flower Beds, during architectural survey source Author.

Figure 15.

Recent photographs of the remaining vestiges of the House of Raised Flower Beds, during architectural survey source Author.

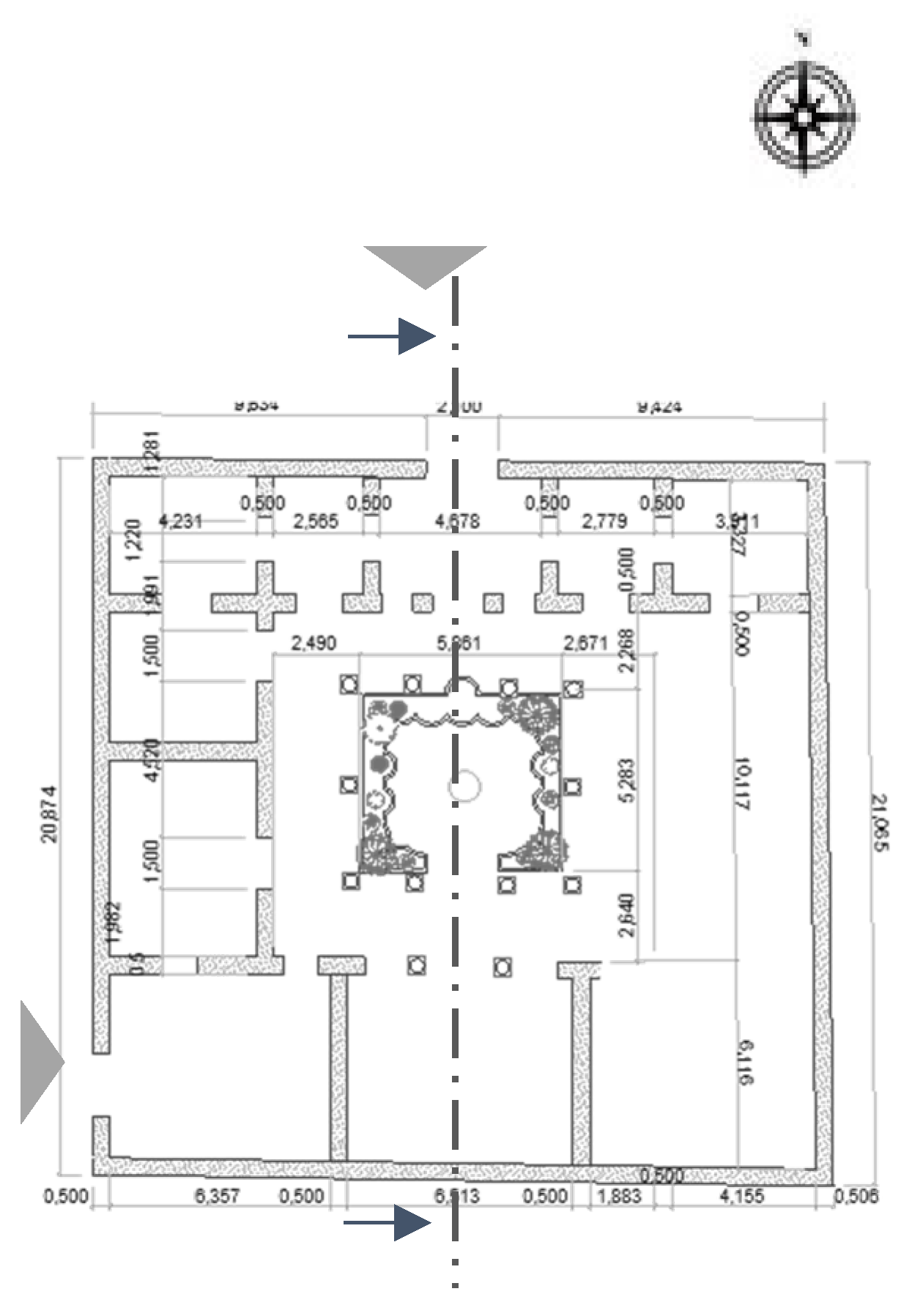

Figure 16.

Plan of the remaining vestiges, the house of planters Archicad,2023 by Author.

Figure 16.

Plan of the remaining vestiges, the house of planters Archicad,2023 by Author.

The house has two access doors; the principal one is located on the triumphal way (Decumanus), and the secondary one is from the west side to the forum.

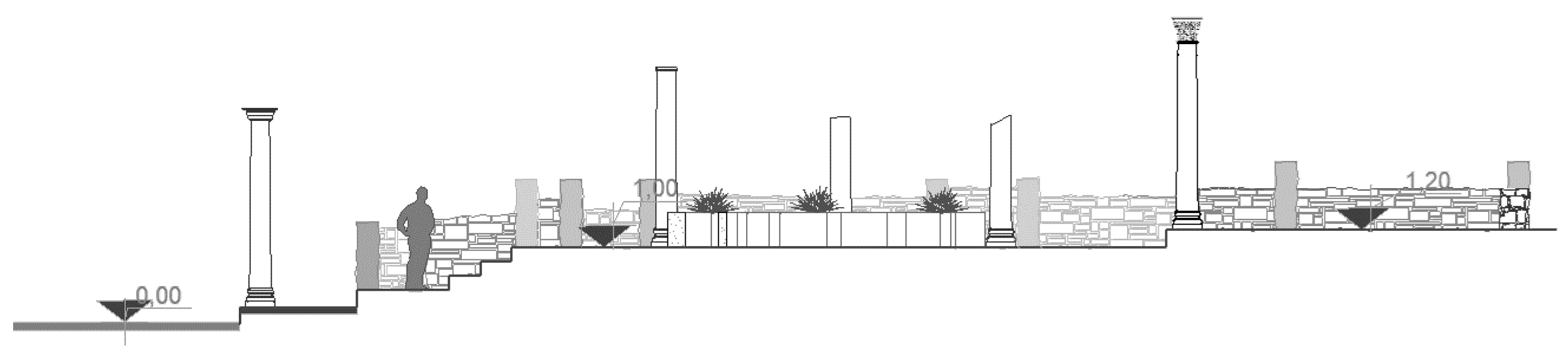

We realized a 2D plan of the survey, as well as an axial section through the main key living areas of the house (vestibule, peristyle, tablinum ).

Figure 17.

Section along the main axis of the house linking entrance peristyle and reception room, archicad.2023, By Author.

Figure 17.

Section along the main axis of the house linking entrance peristyle and reception room, archicad.2023, By Author.

Vitruvius Alignment (Reference)

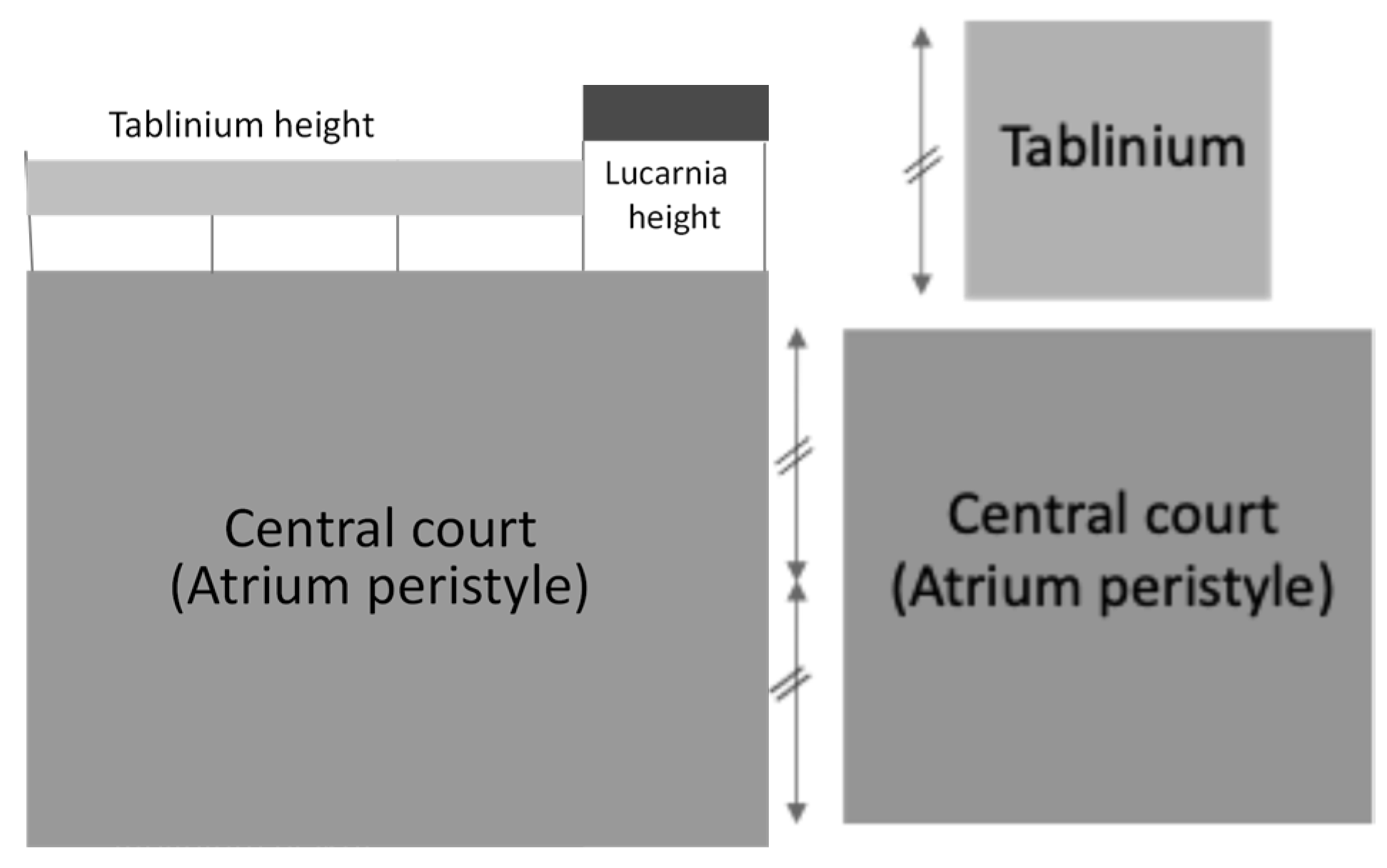

When examining the surveyed plan of the house we highlighted certain important factors:

- 1-

Spatial hierarchy, from the public space represented by the street, followed by the gallery, the vestibule, the central courtyard and finally the reception area.

- 2-

Then the use of symmetry;special attention was paid to proportional relations between the dimensions of the central courtyard and the reception room.

- 3-

Alignment with the principles articulated by Vitruvius in his architectural guide in the sixth book regarding proportional systems: “if the width of the atrium is equal to 40 feet, the width of the Tablinum should be half, and its height under the beams should be equal to its width plus one-eighth. One-third of the width is allocated for the roof height from the beams”[

34].

The adherence to Vitruvian proportions in the floor level enabled us to extrapolate certain missing elements further by extending the height of the walls beneath the roof and maintaining the prescribed height of the doors, as outlined in Vitruvius’s guide to the book of temples. This adherence serves as a foundational framework for the subsequent reconstruction of the entire house.

Figure 18.

Applying proportional prescriptions of Vitruvius ,Author.

Figure 18.

Applying proportional prescriptions of Vitruvius ,Author.

Wall Covering

We were not able to identify any traces of the original wall coverings or paintings within the studied house. This absence is not unusual in the North African context. Only fragmentary and isolated remains of wall paintings have occasionally been noted in other Romano-African houses, but these are rare and often disconnected from their original architectural context[

27]. This scarcity can likely be attributed to both the limited proficiency of excavations and documentation efforts and the deterioration of the upper sections of interior walls over time.

One notable example comes from the Maison d’Asinius Rufinus at Acholla, where fragments depicting actors, charioteers, and theatrical masks were recorded. However, these were described without sufficient contextual integration[

27].

Despite their fragmentary nature, such remnants invite broader reflection on the possible visual culture of Romano-African domestic interiors and the extent to which wall painting may have played a role in articulating status, taste, and cultural aspirations [

35]

In the absence of direct references for wall coverings in the peristyle, we pursued our analogical and interpretive approach rooted in comparative analysis.

Our guiding framework was drawn from well-documented examples of Pompeian domestic architecture, particularly that preserved in elite houses such as the House of the Vettii and the House of the Faun, which contain paintings of the fourth style ; this is known to be the artistic expression of the first century CE, and it extended beyond Pompei[

36], as it is considered to be the trend of paintings in elite houses of North Africa that time[

37]. For the first experience, we opted for the same color palette to approximate the luminous sensations. Regarding the flooring, we selected mosaic patterns that approximate those described by Albert Ballu and Suzanne Germain in[

32].

Once we finalized the 2D plan and the different levels of slabs and fixed the adherence to the proportions outlined by Vitruvius, we proceeded to determine the height of the walls under the roof, as prescribed in the guidelines.

According to Vitruvius, a wall measuring one and a half feet (50cm) in thickness is insufficient to bear the load of multiple floors. This led us to suggest the absence of an upper floor in the house under study.

The architecture of the house is classified under the Doric order, following the Doric capitals. The proportions of the columns are related to the dimensions of the human body. The height of the column is related to its thickness at the base, in which case the column can take on the proportions of a human: height = six times its feet in the Doric order. This principle is applied to fix the height of the peristyle in our case study.

However, for the two elegant columns with Corinthian capitals, standing at the entrance of the tablinum (the audience chamber), their height aligns with Vitruvius’s equation, in which Corinthian columns are sized according to the height of a slender maiden. The height is equal to eight times its feet. According to Vitruvius, the Corinthian order has never had a specific scheme for its cornices or any other decorative elements[

34].

Doors and Openings

Vitruvius emphasized the importance of lighting in his writings, advocating for the strategic placement of windows to ensure well-lit buildings. He advised leaving space for windows on all sides, allowing for clear views of the sky to illuminate the interiors. If obstructions such as upper stories or timber interfered with the view, he suggested placing openings higher up to introduce light effectively.

Windows were typically situated between beams supported by pilasters and columns. Vitruvius stressed the necessity of windows not only in common areas such as dining rooms but also in passages, whether level or inclined, and along staircases[

34]

The proportional principle that was applied to determine the dimensions of doors in houses was similarly applied to temple doors, dividing the height from floor to ceiling into three and a half parts, with two and a half parts forming the height of the door opening.

These patterned squares were used as fillers for apertures and as railings in ancient times. Stone, metal, and wood were all possible building materials for railings. High apertures with a lattice panel to reflect direct sunlight were common for openings, especially in monumental structures. The lattice was often made of stone, preferably marble, and the gaps were filled with a translucent substance, sometimes thin sheets of alabaster .

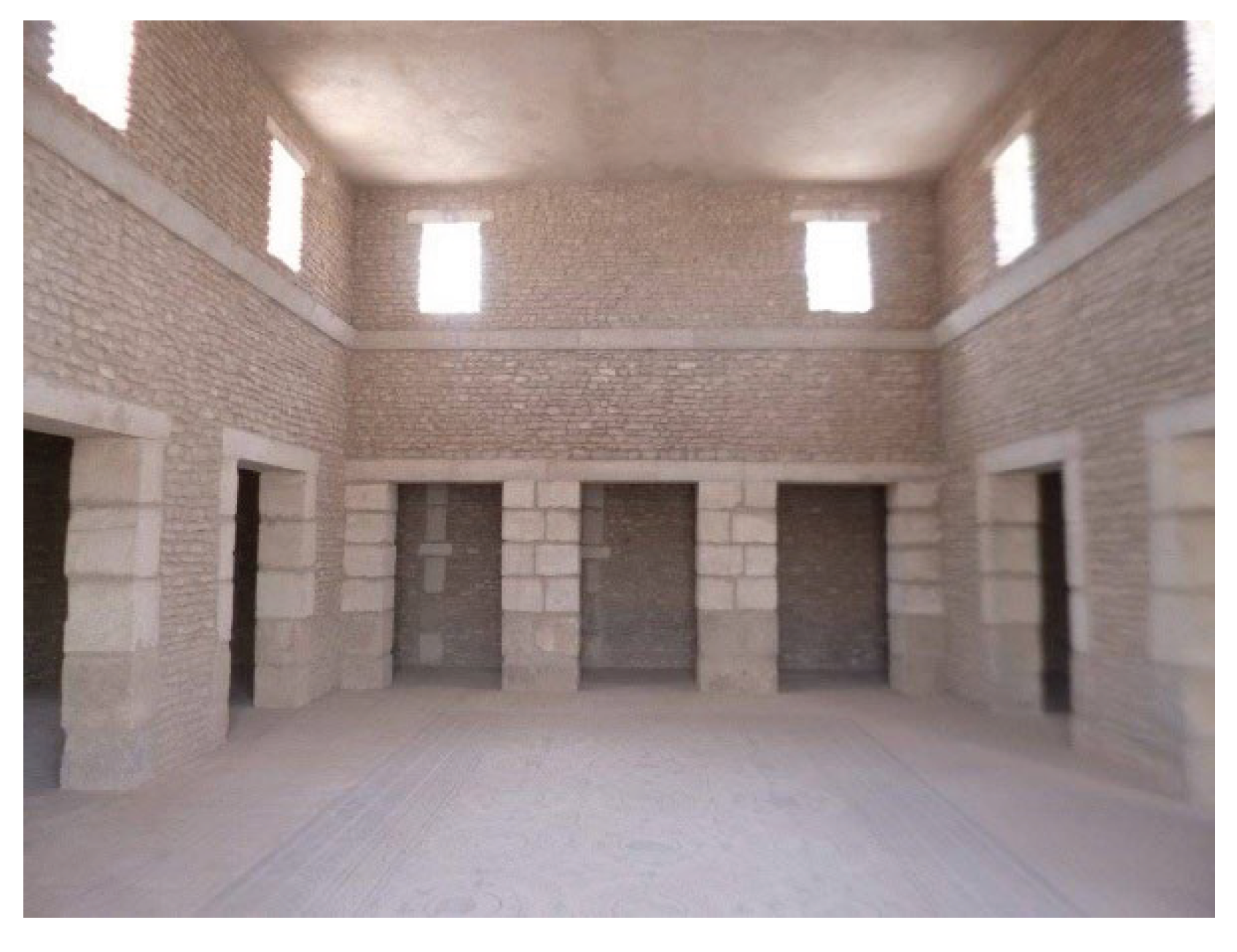

The high height was suitable for hot climates, where the air volume ensured coolness. It also made it possible to place the windows, which were usually not glazed, at a very high level; this avoided the annoyance of draughts. An example of a well-preserved house is Maison Africa, Thysdrus, ElDjem, in southern Tunisia.

Figure 20.

Interior from house of Africa, Thysdirus Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 20.

Interior from house of Africa, Thysdirus Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 21.

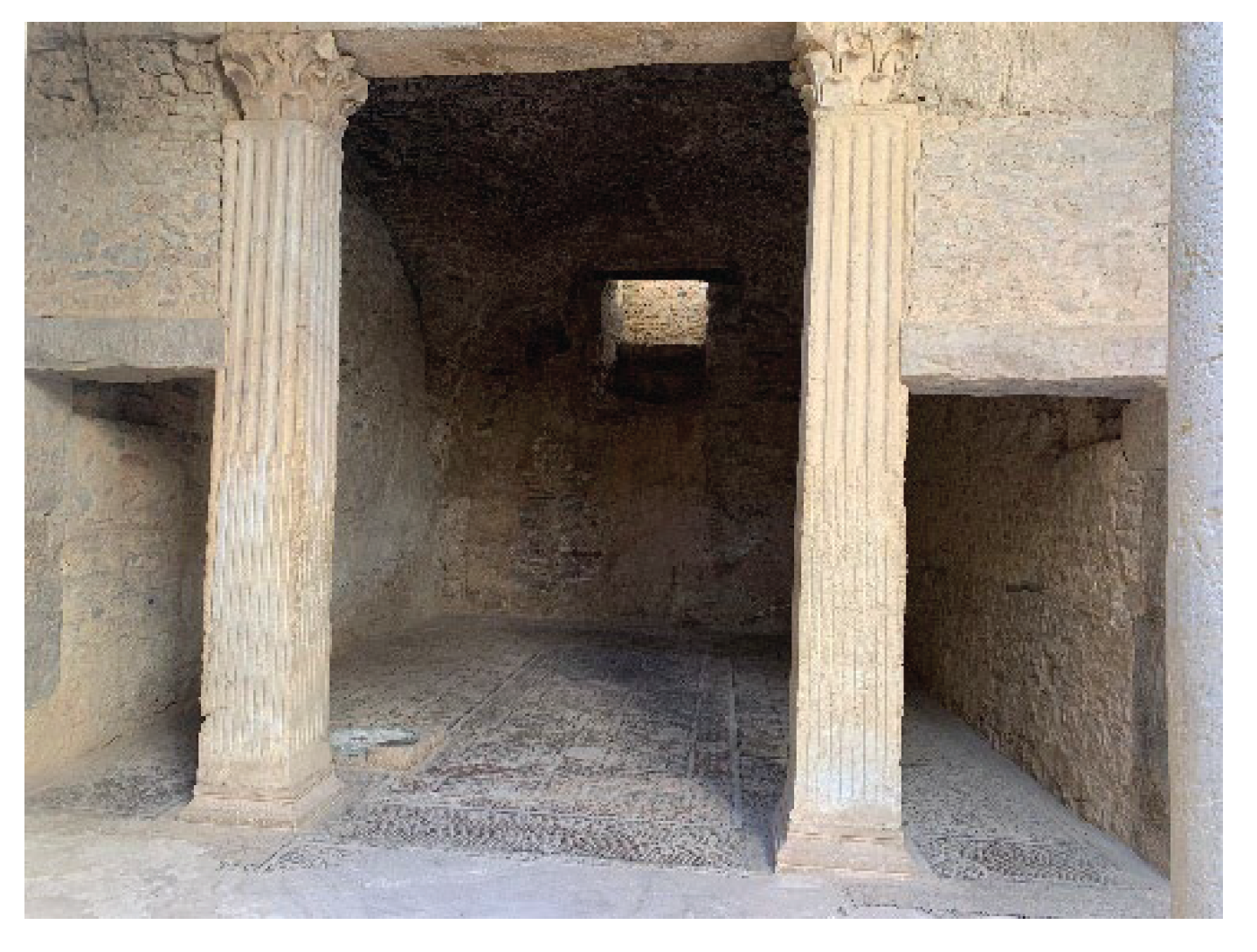

The Peristyle of the house of Africa, Thysdirus Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 21.

The Peristyle of the house of Africa, Thysdirus Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 22.

The entry of tablinumwith its tripartite opening, revealing the clerestory window, in the hunting house in Bulla Regia, Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 22.

The entry of tablinumwith its tripartite opening, revealing the clerestory window, in the hunting house in Bulla Regia, Tunisia, photograph Author.

The house under study was open to the peristyle for security and defensive reasons; the houses of Roman North Africa minimized street-facing apertures[

29]. However, the clerestory

1 windows could not be excludedbecause we found a well-preserved example of a tablinum in the hunting house at Bulla Regia. This is reminiscent of the ancient italic tablinum window in the center of the wall behind the seated patronus (owner) to enhance their appearance and social status[

27].

Roofing

Tiled roofs (tegulae and imbrices): These were likely the most widespread and predominant roofing system for most buildings in Timgad. In Roman North Africa, tiled roofs (tegulae and imbrices) were very frequent in towns and military sites[

38]. Given Timgad’s status as a Roman city and military colony, it would naturally follow this trend for residential, commercial, and other standard structures. These tiles would have been supported by timber frameworks, as wood was extensively used for roof beams and trusses in Roman construction[

39].

The Flower Beds (Planters):

The planters (plant containers) present the most characteristic element of the house, giving it its name. Their shape on the plan is perfectly preserved, shaped with terracotta bricks and bleu limestone. There is no evidence of authentic plants. Nevertheless, rose trees figured as commonly used; they were a recurring motif in the mosaics of North Africa, such as that of the, Viridarium (garden) House at Niches in Pupput and the Amphitrite House at Bulla Regia, which depicted roses or peacocks surrounded by “rose plants”(Carucci, 2007). Moreover, roses are the most commonly evoked in Apuleius’ texts, notably in his novel The Golden Ass[

16]. Therefore, rose trees will be used in our virtually reconstructed itinerary.

After finalizing all of the elements of the architectural configuration, we proceeded to create a 3D model of the house. However, we chose to use a white-finished model that allowed us to determine the volumetry of the space and its proportions while ensuring scientific objectivity.

Figure 23.

Recent photograph of the remaining vestiges of the flower beds, photograph Author.

Figure 23.

Recent photograph of the remaining vestiges of the flower beds, photograph Author.

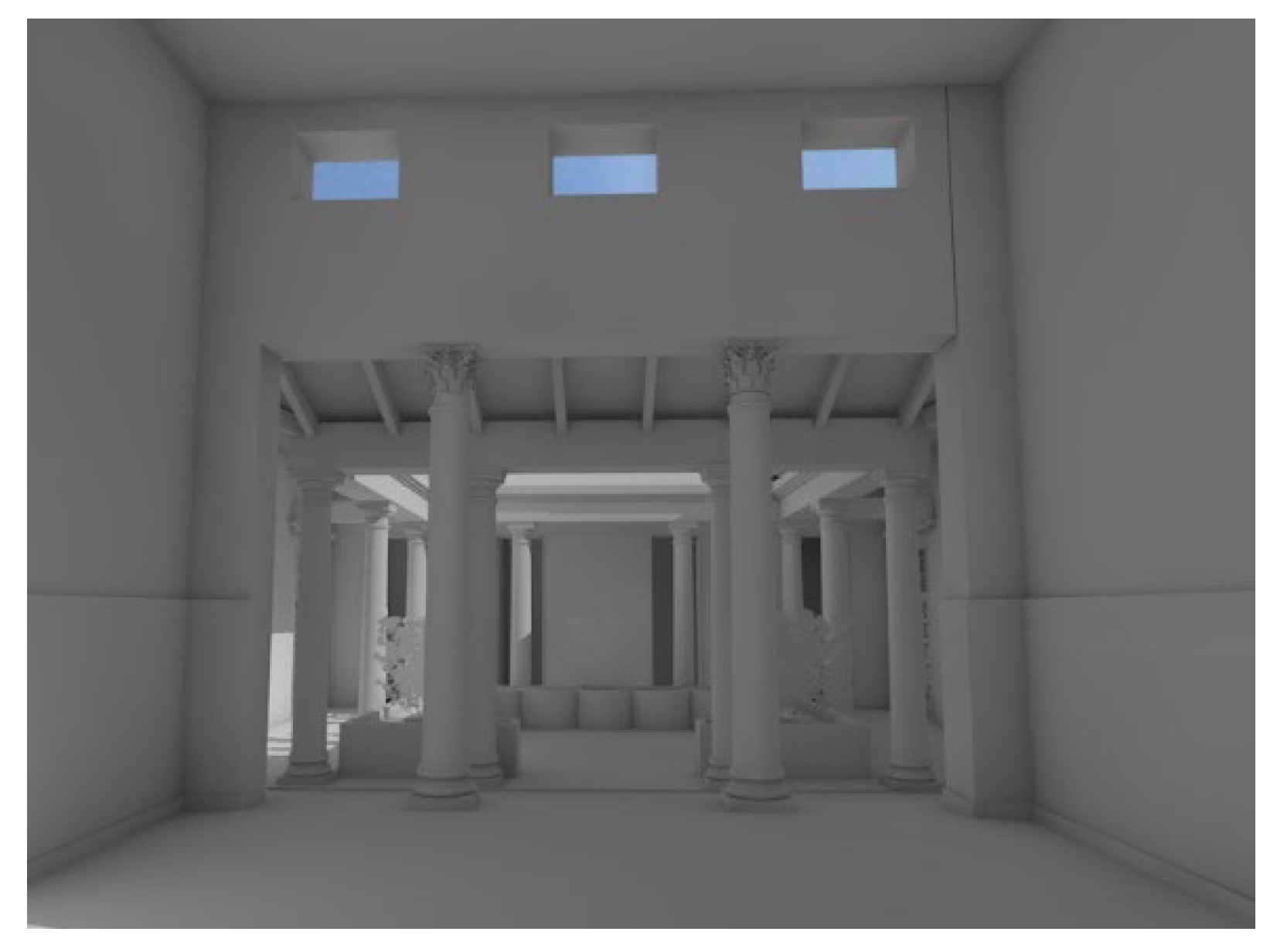

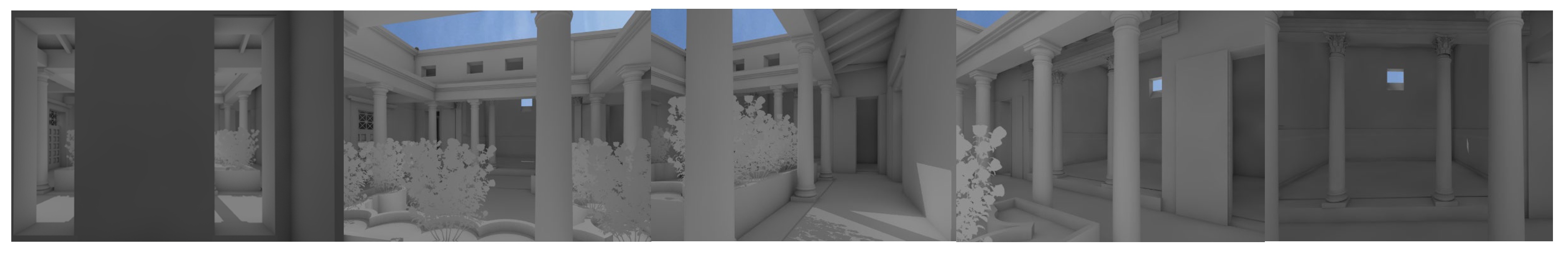

The Resulted 3D Model:

We were able to construct several variants of the 3D virtual model based on the development of hypotheses by following an iterative process that changed as the cited data and the construction requirements extracted from the historical review changed. Only the most recent findings are displayed in this article.

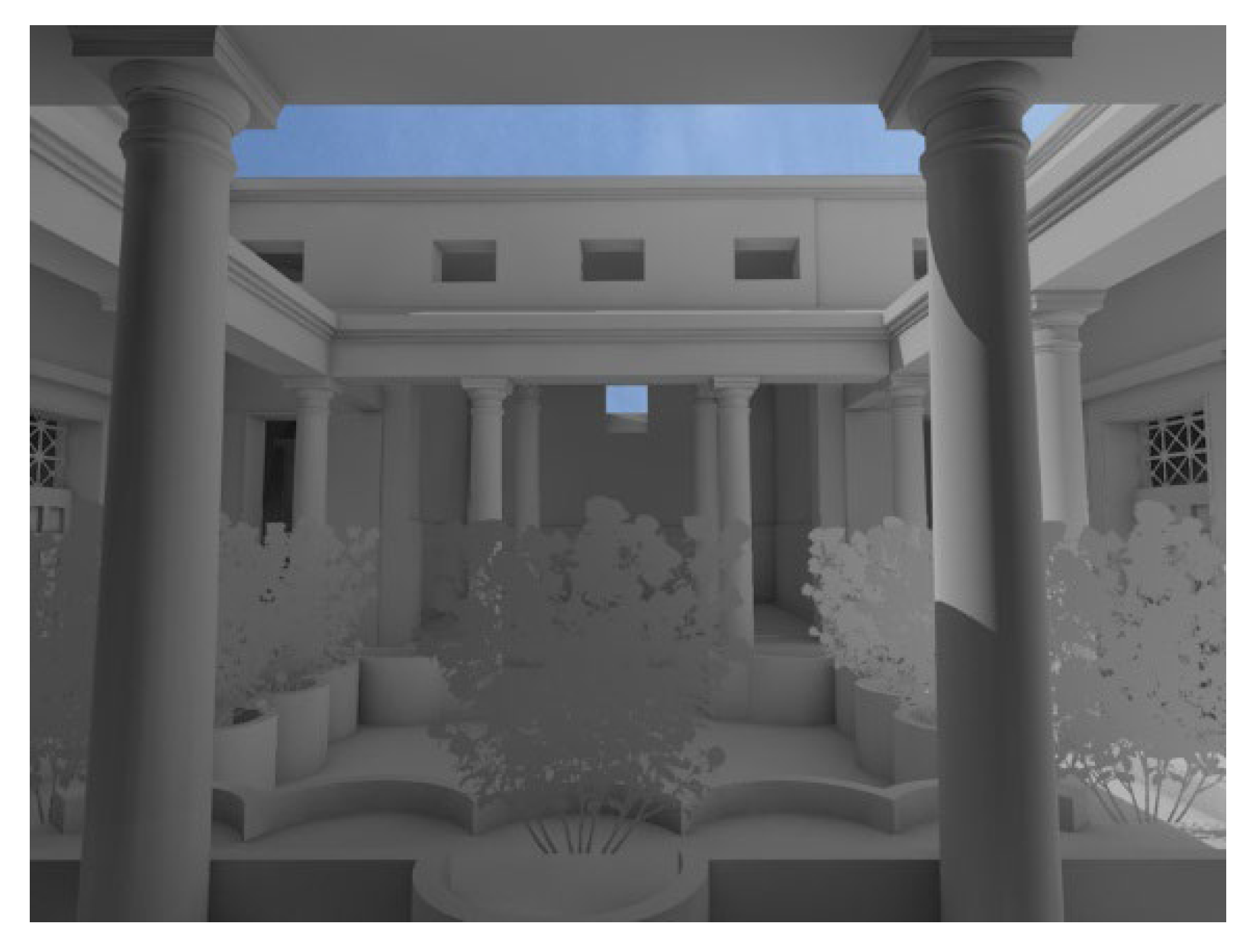

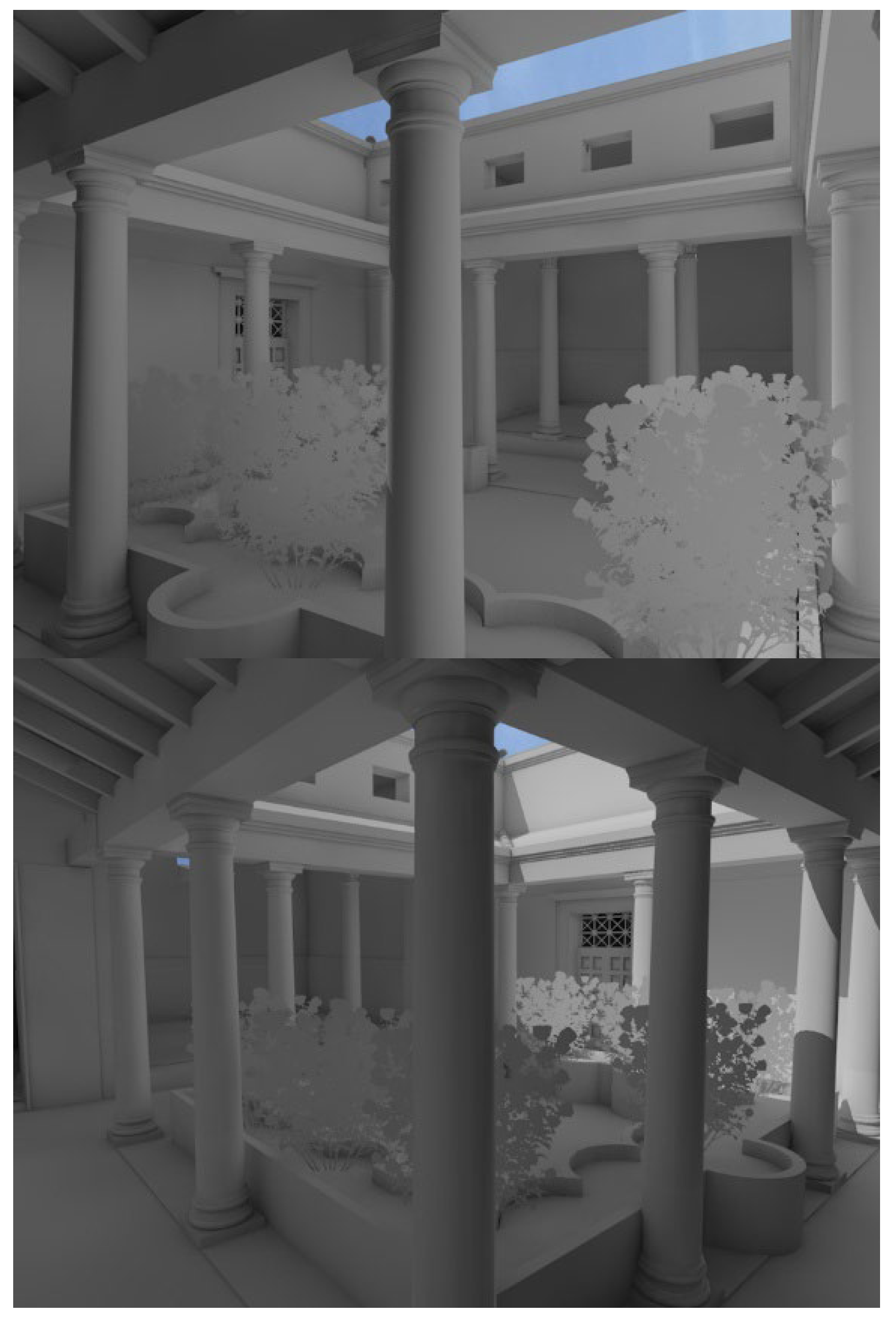

Figure 24.

A perspective on the peristyle towards the reception area (Tablinum), Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering, by Author.

Figure 24.

A perspective on the peristyle towards the reception area (Tablinum), Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering, by Author.

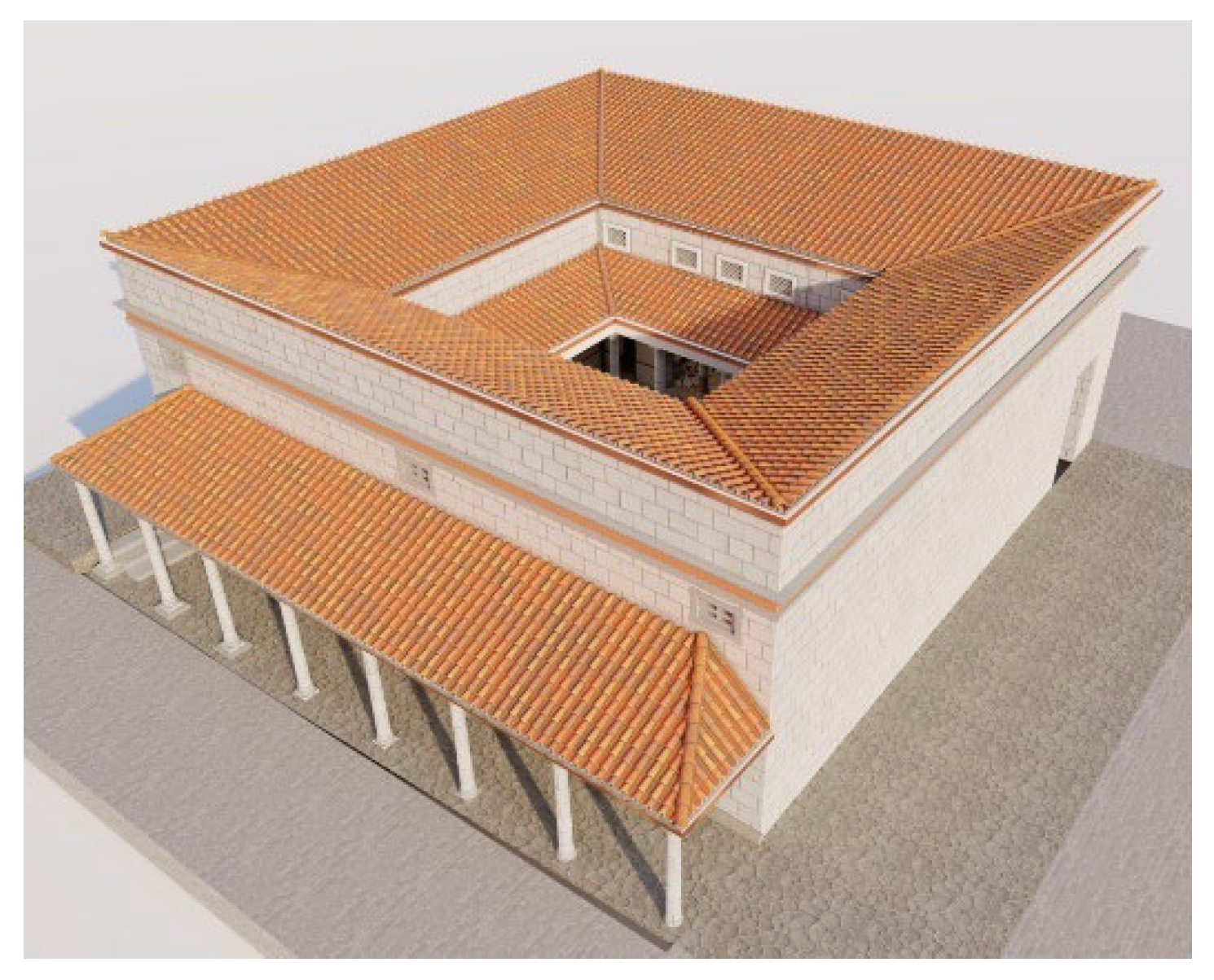

Figure 25.

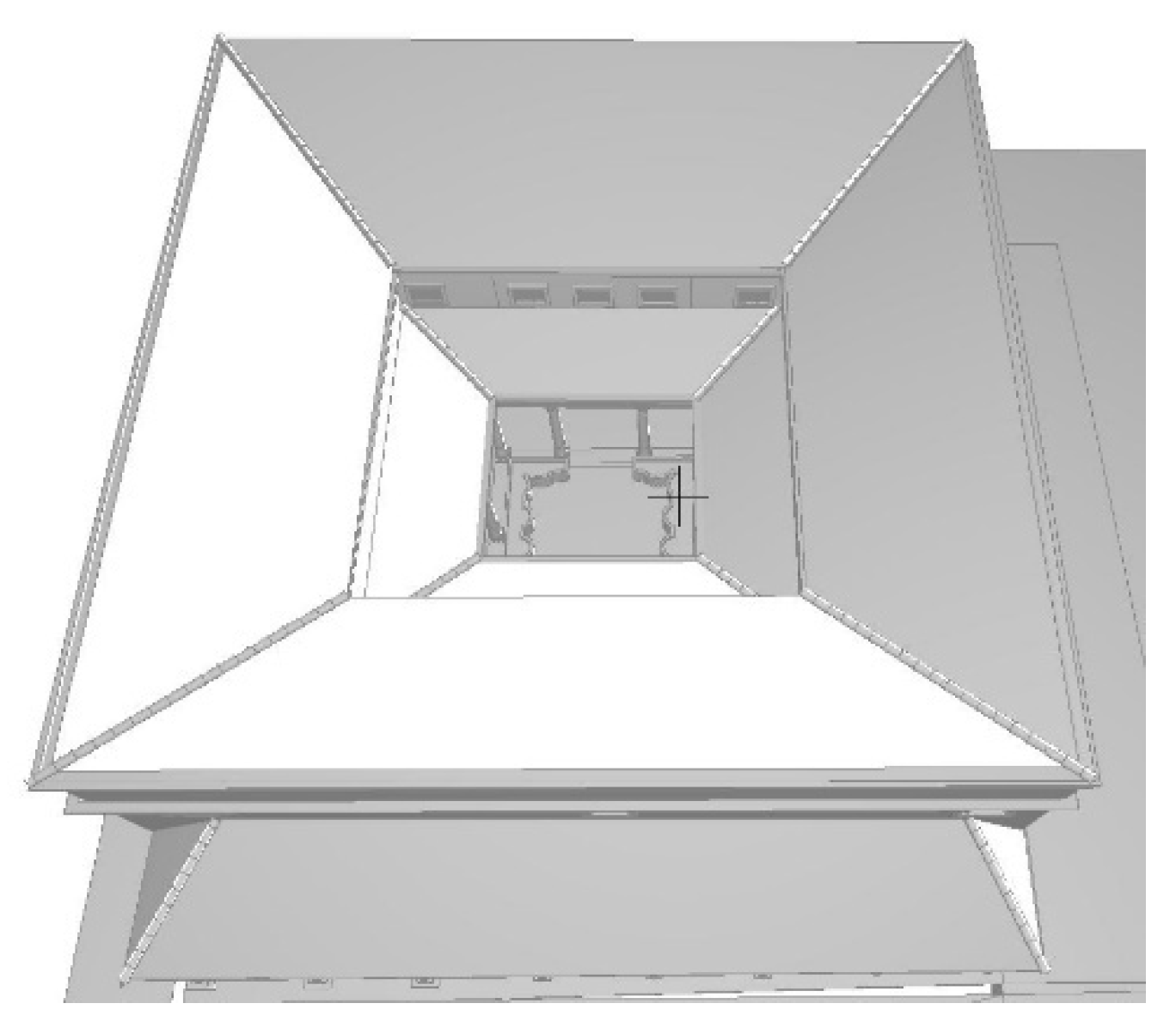

A bird’s eye view of the house, Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering, by Author.

Figure 25.

A bird’s eye view of the house, Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering, by Author.

Figure 26.

A perspective on the peristyle towards. The reception area (Tablinum) Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering in the morning, by Author.

Figure 26.

A perspective on the peristyle towards. The reception area (Tablinum) Archicad,2023 biased, GPU-accelerated path tracer rendering in the morning, by Author.

We concentrated on the primary living spaces (the tablinum and the peristyle). The restored model of the House of the Raised Flower Beds provides a clear view of its architectural features and interior design. The descriptions and evidence that had been gathered so far were materialized. Features that offered a thorough understanding of its geometric composition were noted. The house’s perfect cubic shape and central peristyle design are noteworthy features.

Figure 28.

A perspective from the reception areatowards the peristyle evening time, Archicad,2023biased, GPU-accelerated path tracerrendering in the evening, by Author.

Figure 28.

A perspective from the reception areatowards the peristyle evening time, Archicad,2023biased, GPU-accelerated path tracerrendering in the evening, by Author.

Figure 29.

Perspective vue displaying the volume of the house,Archicad,2023 rendering, By Author.

Figure 29.

Perspective vue displaying the volume of the house,Archicad,2023 rendering, By Author.

Figure 30.

3D projected section displaying main Volume and levels,Archicad,2023, rendered by Author.

Figure 30.

3D projected section displaying main Volume and levels,Archicad,2023, rendered by Author.

The resulting 3D model will serve as an experimental theatrical stage in which we intend to examine the location of daylight and direction of shadows through the path of a visitor to the master of the house. This is a historical social ritual known in Roman society that will be explained in the following section.

7. The User and Use of Space Inside the House of the Raised Flower Beds

The user of space constitutes the most vital component in the conceptual model of ambience. A review of social practices and daily rhythms within the Romano-African domestic sphere reveals that the house functioned not merely as a shelter but as a performative stage for enacting social hierarchy and patronage[

40]. Morning salutations, mid-day promenades, informal exchanges within the peristyle, and evening banquets in the triclinium revealed an affirmation of status and hospitality.

Simultaneously, the cubicula and private quarters offered isolation and intimacy, marking a spatial distinction between public persona and private life. The Roman domestic architecture highlights an adaptable nature through the multifunctionality of the peristyle, which accommodates both an elite display and everyday household activities, such as children’s play or servants’ chores[

40].

These evolving patterns of use directly contributed to the changing character of ambience in the house across the day and depending on the activity, also affecting users’ senses and perceptions.

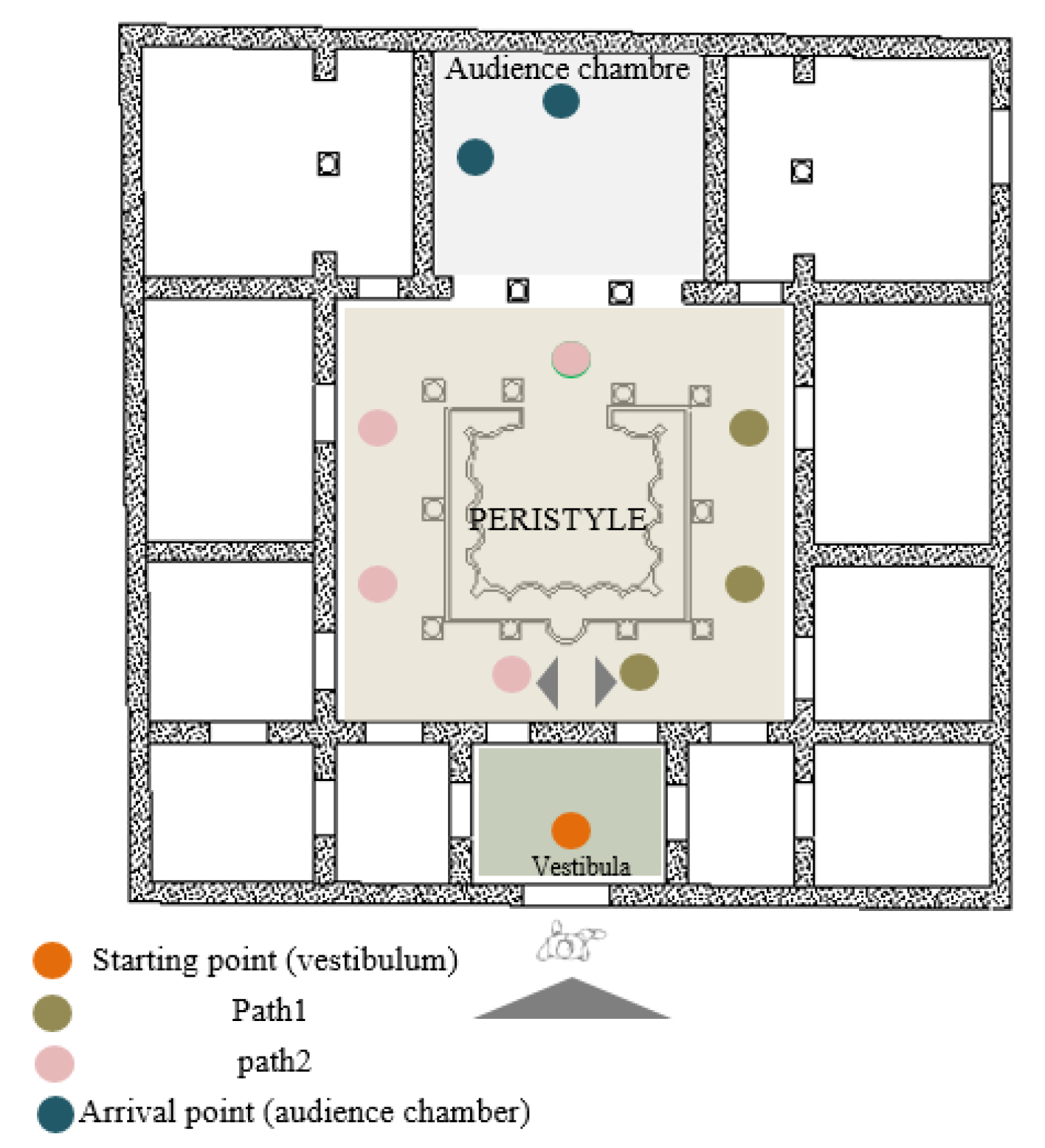

The scenario of a visitor, which includes clients or loyal associates, arriving at the residence of the master of the domicile, forms the core scenario considered within our virtual reconstruction. This was defined by the various visual sequences detected in the field of vision and how they are highlighted by light and shadows. To deepen our understanding of the visitor’s experience and capture their light perceptions, first, we should identify the ritual and its various stages by fixing the visitor’s itinerary from the exterior to the encounter with the master inside the house, including the precise temporality. This was achieved by conducting a literature review of this practice in Roman society and, notably, the African context.

The Ritual of Salutatio

A ritual known as “salutatio”, or salutation, was a familiar daily domestic practice [

41] in the houses of the dominant class. This code of etiquette, as elucidated by Pliny the Elder in [

42], finds its origins in the customs observed by the emperor, serving to uphold the intricate relationship of clientele between the dominus, or master, and his clients [

43].

The salutatio was a significant social custom in the urban houses of Roman senators and other elite members, and it constituted a formal visit of clients or loyal followers to their patronus.

The ritual is also documented in the writings of Apuleius (125-170AD), notably the Apologya, which describes participating in the Roman social life and attending the morning salutatio in Roman African houses[

27].

The Time of Visit

The salutatio started the first two hours of the day, and being one of the first visitors to enter the house was considered especially honorable. Inside the house, only privileged visitors were admitted to rooms around the atrium or even to the inner parts of the house, whereas salutators of lesser importance were greeted in the atrium only[

44]

Retracing the spaces that visitors typically passed through during the greeting ritual requires the definition of the stages of the visit. According to Perring’s studies on Roman houses in Brittany [

45] and those of [

27] in the African context, we note three main steps for undertaking salutatio. These are carried out over a carefully progressed path reflecting the social hierarchy within architectural spaces.

1- Gathering outside. 2-Entering and waiting in the vestibulum.

3-Meet the patronus in the audience chamber(Tablinum)

- 1-

Gathering outside:

In this step, the visitor is outside of the house with an overflow of clients gathered in the street early in the morning; this step emphasizes the patron’s social status and his importance. After being summoned, the visitor is instructed to enter to vestibulum, and the first step is taken with the right foot [

46](p. 124).

- 2-

Entering and waiting in the vestibulum(annexes):

There is a controlled entrance to the vestibulum that serves as the transitional area between the house’s exterior and interior. The vestibulum is constituted of annexes, which are additional spaces that go with it, such as the ianitori cella (porter space) and a storage (sportulas) room. This area is characterized by a bayonet plan to prevent direct views into the core of the house from the street or from the waiting area[

27]. The vestibulum is described to be richly decorated in Apuleius’ writings[

27]. Examples of vestibula documented in neighboring Roman towns are spacious and lavishly decorated, such as in the house of Castorius in Djemila. However, Carucci mentions another aspect, which is that vestibula surveyed in the North African context often show a moderate vestibule size, which aligns with the vestibule in our case study. The clients would have been placed close together in the vestibulum or would possibly have overflowed onto the street.

- 3-

Meeting the patronus in the audience chamber (Tablinum)

The tablinum is named the audience chamber in the North African context[

27], and it is supposed to be set at the end of the atrium’s axis opposite the entrance, ornamented with columns framing the door with an elegant tripartite opening, displaying the owner’s status; he must present himself, putting on his toga from a prominent place such as the tablinum, sometimes framed by architectural elements or lighting to accentuate his presence[

39]. However, specific movable furniture, such as chairs or tables, is not specifically mentioned in the sources for these spaces. It has been noted that Roman furniture was generally movable, and the use of spaces was flexible[

45]. The architectural design frequently included elements that had a similar function. The sources emphasize the existence of some ornamental fixtures, such as document shelves or water basins. For example, in the Asclepius building at Althiburos, the audience hall (tablinum) included rectangular basins with consoles on their edges that were probably used to support statues, improving the patron’s image and promoting occasional interactions[

27].

The privileged guests could proceed further to the triclinia, pinacotheca, and the other private chambers. We restricted the reconstructed visitor itinerary in our study to the audience chamber (tablinum).

Identification of possible perceived prospects

The stages of the ritual require the visitor to cross three main spaces in the house: entrance space (vestibulum) → peristyle → audience chamber (tablinum). Given the availability of two-door access from the vestibulum to the peristyle, we could not define from which one the visitor would have entered. For this reason, we used two possibilities. In this case, two itinerary paths were reconstructed in the direction of the audience chamber.

Figure 31.

Mapping visitor pathway, Author.

Figure 31.

Mapping visitor pathway, Author.

Figure 32.

Longitudinal section along the path, showing presumed prospect direction of the visitor when entering peristyle, (Archicad,2023) By Author.

Figure 32.

Longitudinal section along the path, showing presumed prospect direction of the visitor when entering peristyle, (Archicad,2023) By Author.

Figure 33.

Longitudinal section along the path, showing presumed prospect direction of the visitor in the audience chamber, (Archicad,2023) By Author.

Figure 33.

Longitudinal section along the path, showing presumed prospect direction of the visitor in the audience chamber, (Archicad,2023) By Author.

Upon arriving in the audience chamber (tablinum), the prospective direction is presumed to change to the direction of the peristyle: from the audience chamber (tablinum) to the peristyle.

There is also the possibility of sitting to the side of the patronus and looking to the front wall.

So far, we have determined the architectural conformance and the potential uses for the area. The next step is to examine the perceived light at the time of the visit using the anticipated path.

8. The Luminous Environment of the House

Daylighting was a crucial factor in the daily life of Roman society. Most activities began at sunrise and concluded before sunset[

3].

In a Roman house, daylight was introduced through several features, such as sky openings in the atrium and peristyle, as well as through windows and doors.

In the North African context, most houses were dominated by the peristyle layout. These were the primary means of allowing air and light into the surrounding rooms.

Vitruvius placed significant emphasis on the importance of lighting in buildings in his writings. He indicated that windows should be positioned to allow a clear view of the sky from all sides. It is recommended that windows be installed in the spaces between beams supported by pilasters and columns. Vitruvius stressed that windows are essential not only in dining rooms and common areas but also in hallways, both level and inclined, as well as on staircases[

34].

Natural light plays a crucial role in creating a theatrical appearance for the building and enhancing the presentation of its interior spaces. It interacts dynamically with architectural elements, casting shadows and highlighting specific areas, which draws attention to the decorations and accentuates the textures of surfaces. It amplifies the richness of materials and affects the quality of the atmosphere during the day [

35]

Figure 34.

A view of the sky from the underground reception room of the hunting house in Bullaregia, Tunisia, photograph Author.

Figure 34.

A view of the sky from the underground reception room of the hunting house in Bullaregia, Tunisia, photograph Author.

Following the predicted Visitor Path, we integrated a solar trajectory simulation into the reconstructed model to investigate how daylight affected the visitors’ experience in the House of the Planters. After the virtual model was finished, the software’s ray-tracing module was used to accurately determine the solar path by entering the site’s geographic coordinates, as well as the predicted date and time of the visit, making it possible to calculate the corresponding solar azimuth and altitude.

The existence of two adjacent doors to enter the peristyle from the vestibulum, a design mentioned by Vitruvius when designing theatres, facilitated and organized the spectators’ flow. We presume that access was from the right door, and the exit was from the left one. According to a spiritual parody in the Aeneid, one leaves hell through a door other than the entrance (Aeneid, VI, 898). This parody is mentioned in the texts of Petronius[

46].

The generated images of the predefined prospective sequences of the visit are presented in succession from the vestibulum (waiting area) to the audience chamber (tablinum). These views are constituted and conceived as ”clichés” according to the itinerary of a visitor. along the visitor’s itinerary. They are intended to represent the sequential sensory experience of a moving occupant,focusing on the key visual and luminous events they would encounter(

Figure 35).

The second sequence of images, display the visitor prospect when leaving the audience chamber towards the exit door.

Figure 36

Now, we analyze the perceived topology of light; we minimize the level of details to focus on lighting qualities (C. M. H. Demers, 1997) according to brightness and contrast levels by using the Adobe Photoshop© software. First, we segmented the brightness levels of the rendered image with the command “Isohélie”; after that, we generated a histogram ofluminosity.

Figure 37.

Isohelic image (entering path); segmentation of brightness levels (Adobe Photoshop,2022, by the author).

Figure 37.

Isohelic image (entering path); segmentation of brightness levels (Adobe Photoshop,2022, by the author).

Figure 38.

Histogram of luminosity of the entering path image sequences, Adobe photoshop,2022.

Figure 38.

Histogram of luminosity of the entering path image sequences, Adobe photoshop,2022.

The histogram displays three main ranges of luminosity (brightness/contrast); the first range is characterized by low levels of luminosity (0-85), the second one shows high levels of luminosity (171-255), and the third one examines mid-levels (86-171). The mean brightness (90.01) is relatively low, with moderate contrast (25.47), and the image appears to be underexposed to direct lights.

Figure 39.

Isohelie image (exit path), brightness levels segmentation adobe photoshop,2022. by Author.

Figure 39.

Isohelie image (exit path), brightness levels segmentation adobe photoshop,2022. by Author.

The second histogram is almost identical to the first, revealing three main ranges of luminosity (brightness/contrast); the first range is characterized by low levels of luminosity, the second one shows high levels of luminosity, and the third one shows mid-levels. The mean brightness of 84.47 indicates a shady ambience dominating the image.

Figure 40.

Isohelic image(entry path); brightness level segmentation (Adobe Photoshop,2022,by the author).

Figure 40.

Isohelic image(entry path); brightness level segmentation (Adobe Photoshop,2022,by the author).

9. Discussion

Overlaying the image analysis using Photoshop and the images rendered with ray-tracing programs provides a preliminary reading. The living spaces are underexposed to direct light. The overlit point is at the sky opening of the peristyle. Then, the light gradually proliferates to the surrounding rooms, passing through the porticos.

The examined path represents the honorific route typically used for clients and dignitaries (salutators)[

40].

The first space to be crossed (the vestibulum) has a dark atmosphere. Darker spaces are deeper ones[

47]; they evoke ambiguity and attention, also creating a moment of spatial compression. This ambience correlates with the first range of luminosity in the histogram in

Figure 36. Suddenly, the visitor (salutator) emerges into the inviting, luminous peristyle. The visitor is surrounded by colonnades and luxurious greenery. The area is both open and controlled by the obscure surrounding spaces. This stage of the itinerary aligns with the second range displayed in the histogram. The audience chamber (tablinum) is positioned at the end of the peristyle’s axis opposite the entrance, ornamented with elegant Corinthian columns; this displays a shadowy atmosphere, as presented in the third range of the histogram. The gloomy aspect of the interiors is revealed in the iconographic sources (painting) mentioned previously in the present paper, such as the painting of a maiden on a balcony in

Figure 6.

The examination of the ray-tracing images and histogram of the rendered images revealed a clear disparity in luminosity levels; the highest ones are displayed in the peristyle, characteristic of open courtyards, while the audience chamber (tablinum) and the spaces surrounding the peristyle exhibited significantly lower values. This created a reserved and obscure atmosphere.

The natural light ambience evokes a succession of impressions and reactions in the visitor. From the narrow, dimly lit vestibule (entrance space) to the luminous, expansive peristyle, a sensory contrast could have been created.

This contrast does not appear to be random, but rather could reflect functional and sociocultural considerations specific to Roman residential architecture. The high levels of luminosity in the peristyle seem to have served to accentuate the master’s visual surveillance of arriving visitors in order to establish a spatial hierarchy and a sense of mystery while preserving the privacy and security of the interior residential spaces.

The luminous spaces encourage movement and interaction, while darker spaces inspire more prudence and rest. There is clear evidence of human adaptation to feebly lit spaces and brightness ranges. This differentiation in lighting is consistent with historical accounts that domestic spaces were conceived as an intermediary between public and private spaces.

Another fact that should be revealed is that shady ambiences could be linked to thermal regulation and climatic adaptation; the modulation of light through architectural features such as porticos and trees in planters would have moderated solar gain and enhanced well-being indoors. This hypothesis could be developed in future extended research works.

Conclusions

Our approach in this work allowed us to examine the immaterial aspect felt in the House of Raised Flower Beds, of which only vestiges remain, by combining archaeology, architectural analysis, and digital tools. The conceptual model of ambience used, as well as the working logic, allowed us to study (decompose) the components of the ambience within the architectural space and then recompose them to generate the desired ambience by highlighting the possible interactivities between the components. The content analysis of excavation archives, as well as literature texts and iconography (mosaics and paintings), revealed much evidence on the culture and the lived experience, which allowed us to understand, compare, and interpret the results.

Digital means allowed for a non-destructive digital intervention. This enabled us to construct a hypothetical architectural configuration of the house. The latter, served as a geometrically neutral model to test invariant architectural phenomena (light zoning, brightness and shadows).the various luminous zones in the same space are objectively identified and locatedwithin rendered images.Drawing on the analytical study of social context and iconic sources, we approached how these changing configurations of daylight and shadow might affect the visitor’s movement and perception of the space.

The results of this study are still hypothetical and subject to revision as further scientific developpement emerge in this field of knowledge. Nevertheless, given the considerable lack of data commonly prevailing for the case of North African heritage contexts, the simulations we have produced constitute an objective basis for future analysis (tests) and reconsideration. By focusing on the sensory heritage and the lived experience (vécu), our research work attempts to fill this gap in addition to set up the links between the architectural shape and the spirit of such lost places.

References

- PLATTS, H. , 12 Experiencing Sense, Place and Space in. Housing in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Material and Textual Approaches, 2022: p. 381.

- Betts, E. , Senses of the empire: Multisensory approaches to Roman culture2017: Taylor & Francis.

- Ellis, S. , Shedding light on late Roman housing, in Housing in late antiquity-volume 3.22007, Brill. p. 283-302.

- Belakehal, A. Ambiances patrimoniales. Problèmes et méthodes. in Ambiances in action/Ambiances en acte (s)-International Congress on Ambiances, Montreal 2012. 2012. International Ambiances Network.

- Amphoux, P. , et al., La notion d’ambiance, 1998, IREC (Institut de Recherche sur l’Environnement Construit); Ecole ….

- Belakehal, A. , De la notion d’ambiance. 2013.

- Vital, R. , Incorporation of cultural elements into architectural historical reconstructions through virtual reality2006: University of California at Los Angeles.

- Dogan, E. and M.H. Kan, Bringing heritage sites to life for visitors: towards a conceptual framework for immersive experience. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), 2020. 8(1): p. 76-99.

- Asma Achraf, Z. , Architecture moderne à Biskra, étude monographique et ambiantale d’un projet d’habitat moderne inédit, in Departement of architecture2018, Mohamed KHIDER university: BISKRA.

- Campanaro, D.M. and G. Landeschi, Re-viewing Pompeian domestic space through combined virtual reality-based eye tracking and 3D GIS. Antiquity, 2022. 96(386): p. 479-486.

- Rodríguez-Moreno, C. Analysis and Graphic Recreation of the House of Venus in Volubilis (Morocco). Architecture from Archeology. in Graphical Heritage: Volume 3-Mapping, Cartography and Innovation in Education. 2020. Springer.

- Wilson, A. , Urban Production in the Roman World: The View from North Africa. Papers of the British School at Rome, 2002. 70: p. 231-273.

- Ballu, A. , Théâtre et forum de Timgad (antique Thamugadi), état actuel et restauration: par Albert Ballu1902: E. Leroux.

- Demers, C. and M. Arch. A classification of daylighting qualities based on contrast and brightness analysis. in PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOLAR CONFERENCE. 2007. AMERICAN SOLAR ENERGY SOCIETY; AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, B. , Visualizing Pliny’s villas-REINHARD FÖRTSCH, ARCHÄOLOGISCHER KOMMENTAR ZU DEN VILLENBRIEFEN DES JÜNGEREN PLINIUS (Philip von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein, 1993). ISBN 3-8053-1317-9. 202 pp., 86 plates.-PIERRE DE LA RUFFINIÈRE DU PREY, THE VILLAS OF PLINY FROM ANTIQUITY TO POSTERITY (University of Chicago Press, 1994). ISBN 0-226-17300-3. 377 pp., 198 figs., 48 color pls. Journal of Roman archaeology, 1995. 8: p. 406-420.

- KENNEY, E.J. , APULEIUS The Golden Ass or Metamorphoses, 2016, Penguin Group.

- ZIDELMAL, N. , Les Ambiances de La Maison Kabyle Traditionnelle, les révélations des textes et des formes, 2012, Université Mohamed Khider-Biskra.

- Métraux, G.P. , Ancient Housing:” Oikos” and” Domus” in Greece and Rome. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 1999: p. 392-405.

- FINKELPEARL, E., B. LEE, and L. GRAVERINI, Apuleius and Africa. New York: Routledge. Flaig, E.(2007),’Gladiatorial Games: Ritual and Political Consensus’, Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2014. 66: p. 83-92.

- Blas de Roblès, J.-M., P. Kenrick, and C. Sintes, Classical antiquities of Algeria: A selective guide. 2019.

- Cagnat, R. , Carthage, TimgadTébessa et les villes antiques de l’Afrique du Nord, H.L. LIBRAIRIE RENOUARD, Editor 1909.

- Ballu, A. , Les ruines de Timgad, antique Thamugadi: sept années de découvertes (1903-1910). Vol. 3. 1911: Neurdein frères.

- Rebuffat, R. , Maisons à péristyle d’Afrique du Nord: répertoire de plans publiés. Mélanges de l’École française de Rome, 1969. 81(2): p. 659-724.

- Thébert, Y. , Vie privée et architecture domestique en Afrique romaine. Histoire de la vie privée, 1985. 1: p. 301-397.

- Gsell, S. , Histoire ancienne de l’Afrique du Nord. Vol. 4. 1920: Hachette.

- Ellis, S. , Lighting in late Roman houses. Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal, 1995(1994).

- Carucci, M. , The Romano-African Domus: studies in space, decoration, and function, 2007, University of Nottingham.

- Perrault, C. , Les dix livres d’architecture de Vitruve: corrigez et traduits nouvellement en françois, avec des notes & des figures2012: Editorial MAXTOR.

- Gros, P. , L’habitat des classes dirigeantes dans la Tunisie antique (à propos d’un livre récent). Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2006. 150(1): p. 535-552.

- Boeswillwald, É., R. Cagnat, and A. Ballu, Timgad: une cité africaine sous l’empire romain1905: E. Leroux.

- Ballu, A. , Les ruines de Timgad (antique Thamugadi). Vol. 1. 1897: Leroux.

- Germain-Warot, S. , Les mosaïques de Timgad. Étude descriptive et analytique. Vol. 2. 1969: Persée-Portail des revues scientifiques en SHS.

- Bentkowska-Kafel, A. and H. Denard, The London charter for the computer-based visualisation of cultural heritage

(Version 2.1, February 2009), in Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage2016, Routledge. p. 99-104.

- Morgan, M.H. and H.L. Warren, Vitruvius: the ten books on architecture1914.

- Carrié, J.-P. , Lumière et autoreprésentation dans l’habitat rural des élites occidentales à la fin de l’Antiquité., in Les marqueurs archéologiques du pouvoir, É.d.l. Sorbonne, Editor 2012, O. Brunet & C.- Édouard Sauvin.

- Engelmann, W. , Pompeji in leben und kunst, 1908.

- Wilson, R.J.A. , Roman Villas in North Africa, in The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin: Late Republic to Late Antiquity, A. Marzano and G.P.R. Métraux, Editors. 2018, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. p. 266-307.

- Rebuffat, R. , L’habitat en Maurétanie Tingitane. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2006. 150(1): p. 567-611.

- Yegül, F. , Roman Architecture and Urbanism. From the Origins to Late Antiquity. Revista CICSA online, Serie Nouă, 2020(VI): p. 151-156.

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. , The Social Structure of the Roman House1. Papers of the British School at Rome, 1988. 56: p. 43-97.

- Degand, M. The salutatio, a social ritual within the Roman house. Approach to the public/private distinction in the domus in the light of E. Goffman’s ritual notion. in Public and Private in the Roman House and Society Conference. 2013.

- Lepper, F. , The Letters of Pliny. A Historical and Social Commentary, 1970, JSTOR.

- Borges, M.E. , La mosaïque de seuil en Afrique romaine Typologie et interprétation. Al-Sabîl : Revue d’Histoire, d’Archéologie et d’Architecture Maghrébines 2020. N°9: p. 34.

- Goldbeck, F. and P. Arena, “ Salutationes” in republican and imperial Rome: development, functions and usurpations of the ritual2010: Harrassowitz.

- Perring, D. , Houses in Roman Britain: a study in architecture and urban society1999: University of Leicester (United Kingdom).

- Nodot, F. , PETRONE LATIN, ET FRANCAIS, TRADUCTION ENTIERE, SUIVANT LE MANUSCRIT TROUVE’ A BELLEGRADE en 1688., 1713, University of Libraries 1817 ARTES SCIENTIA VERUTAS. p. 584.

- Haar, T. , Depth Perception in Daylight-an approach to depth perception throughthe illumination of diffuse daylight, 2015.

Notes

| 1 |

Clerestory windows are mentioned by Vitruvius in his ten books, windows designed to bring light

from a higher level, plus they provide a view to the sky. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).