Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

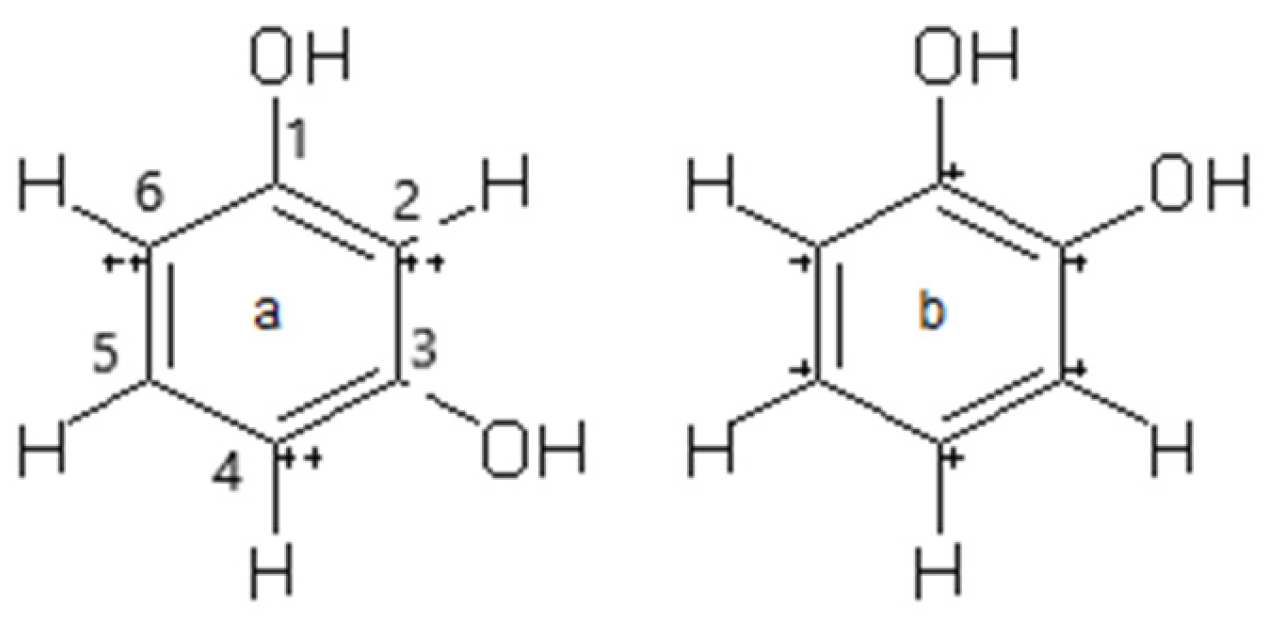

2. Phenolic Compounds in Grapevines: Structure, Reactivity, and Role in Plant Development

3. Evolution of Phenolic Compounds During Grape Ripening

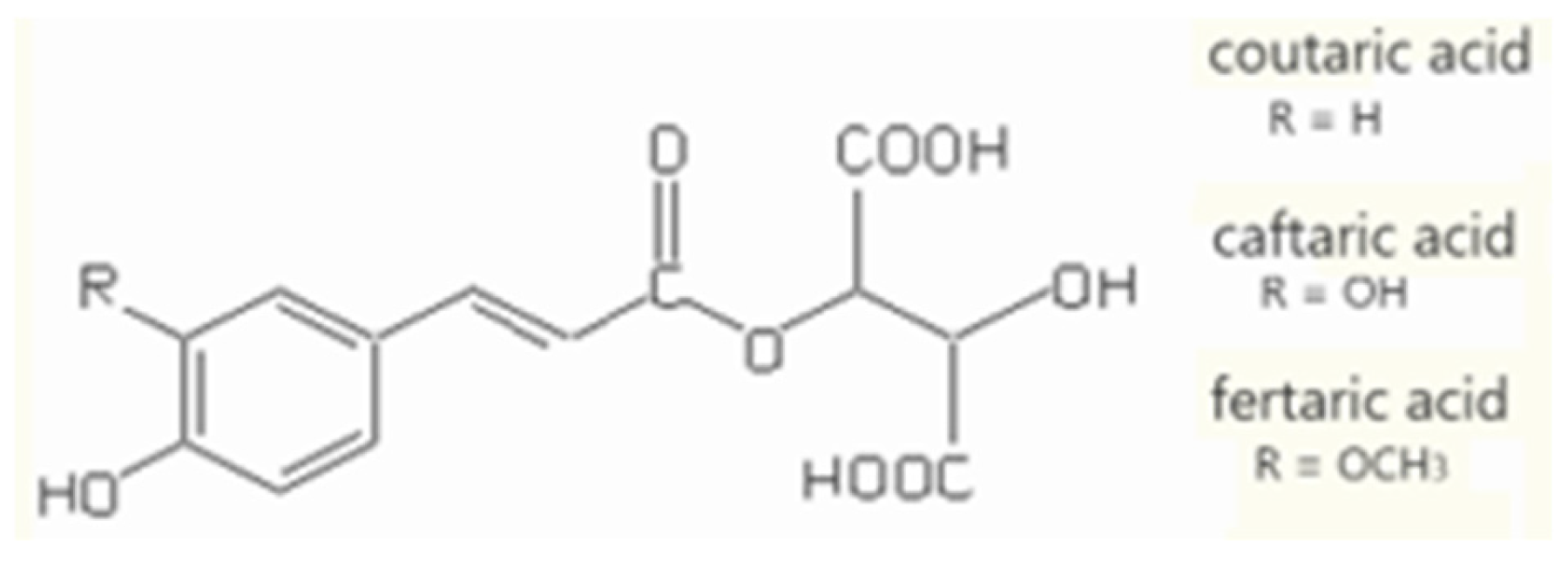

3.1. Non-Flavonoid Phenolics

3.2. Flavonoid Phenolics

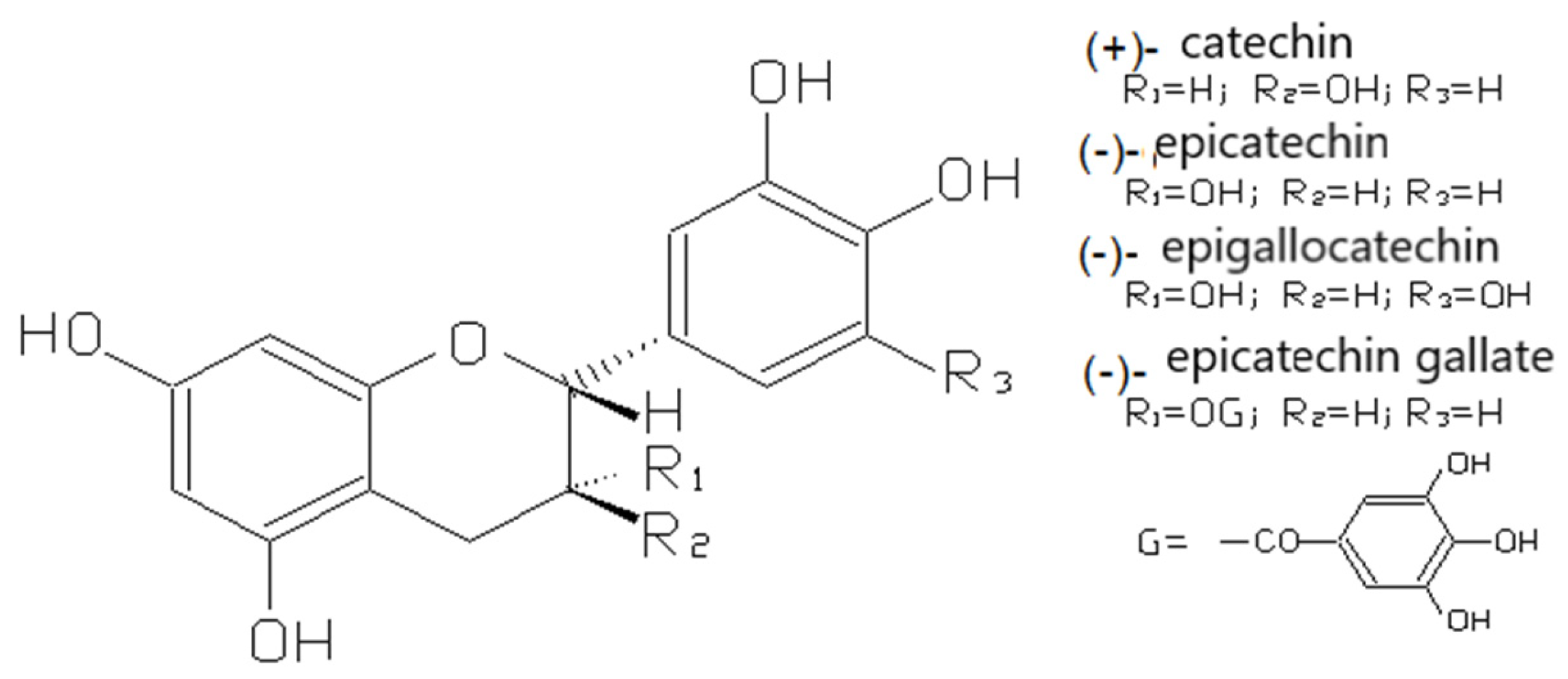

3.2.1. Flavan-3-ols

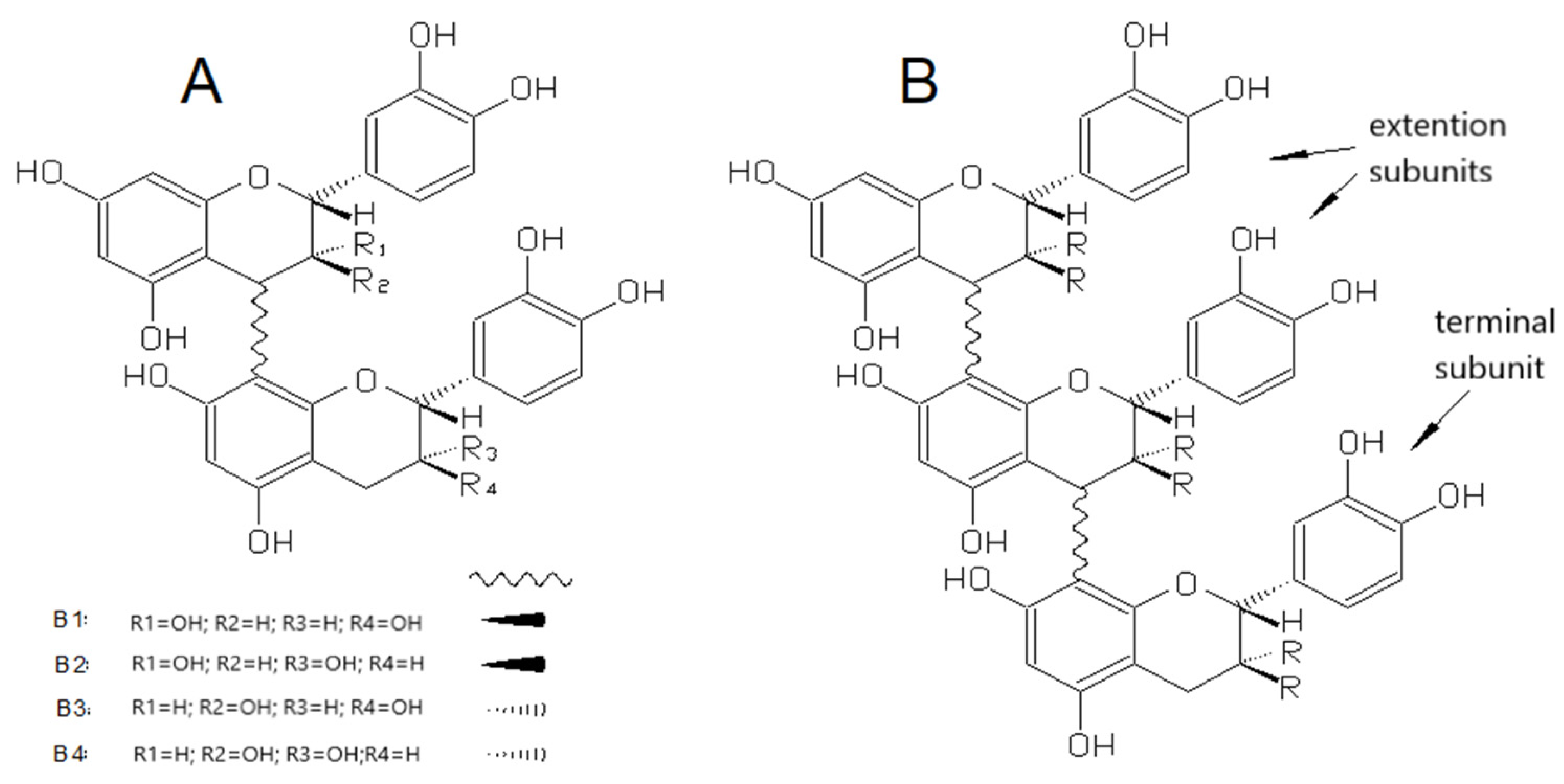

3.2.2. Proanthocyanidins

3.2.3. Flavonols

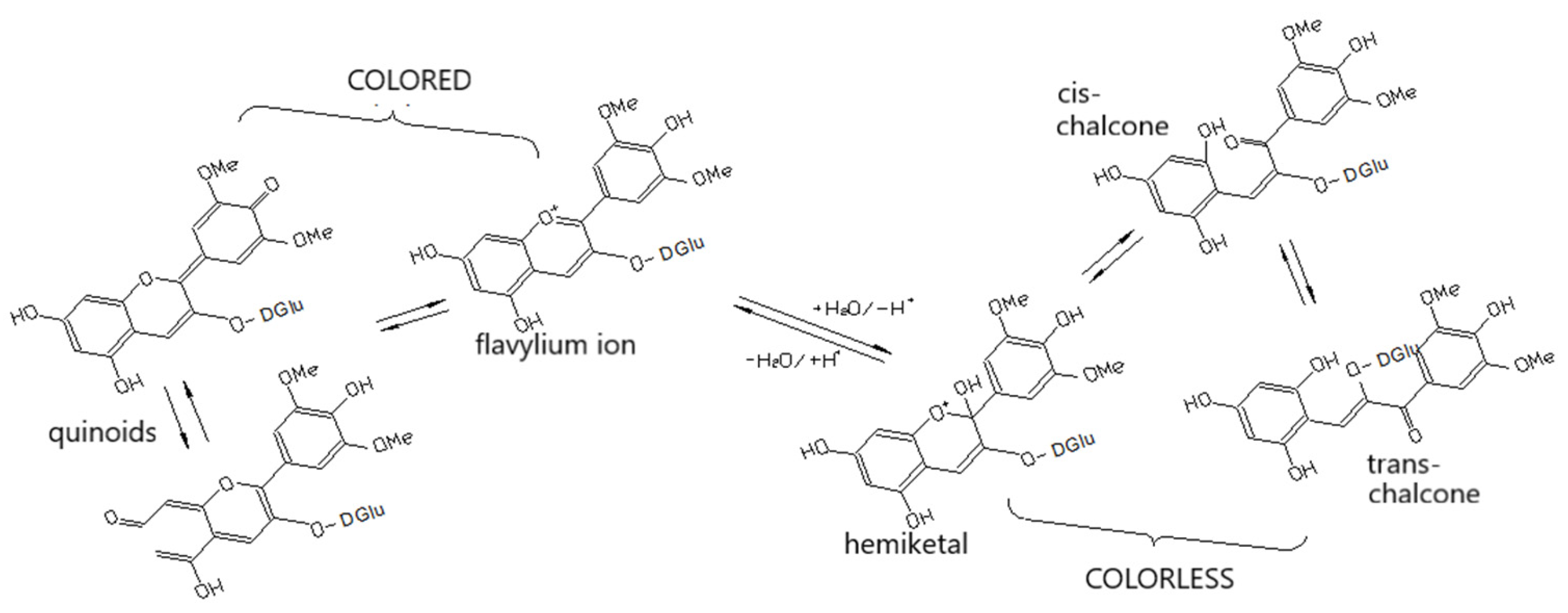

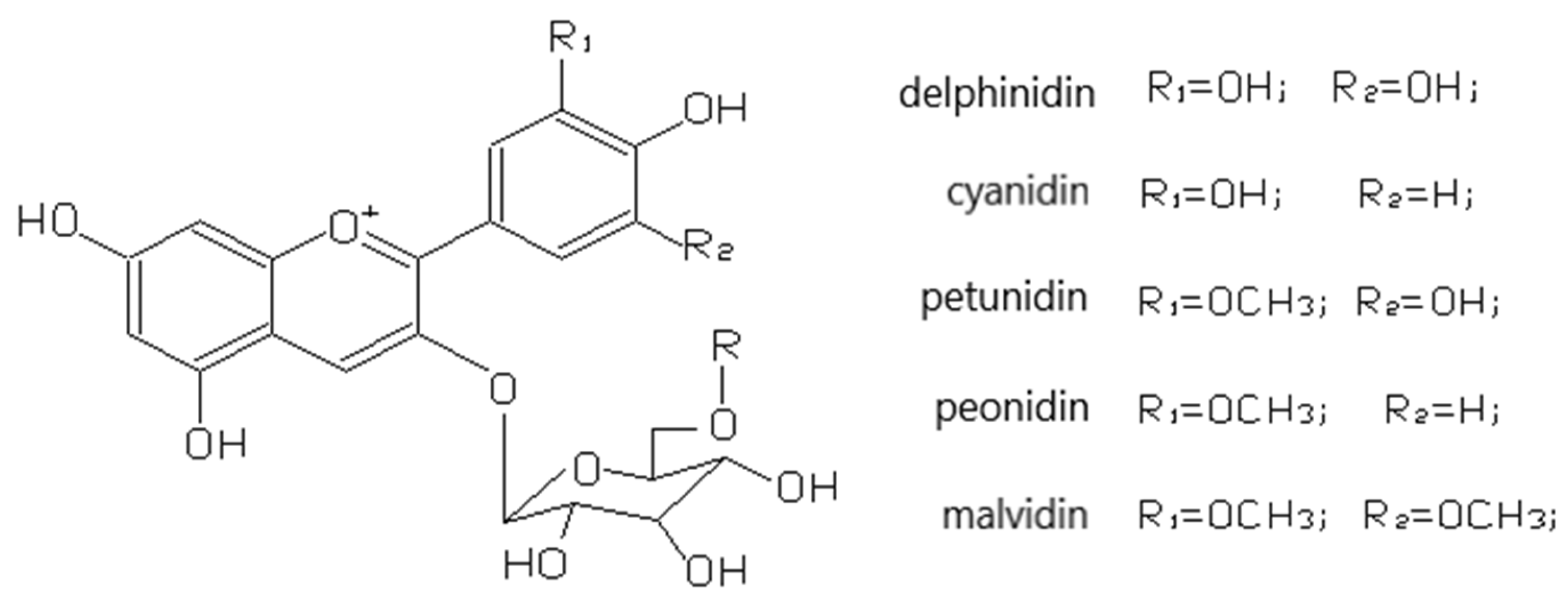

3.2.4. Anthocyanins

4. Phenolic Compounds and Wine Quality

4.1. Pigmentation and Co-Pigmentation

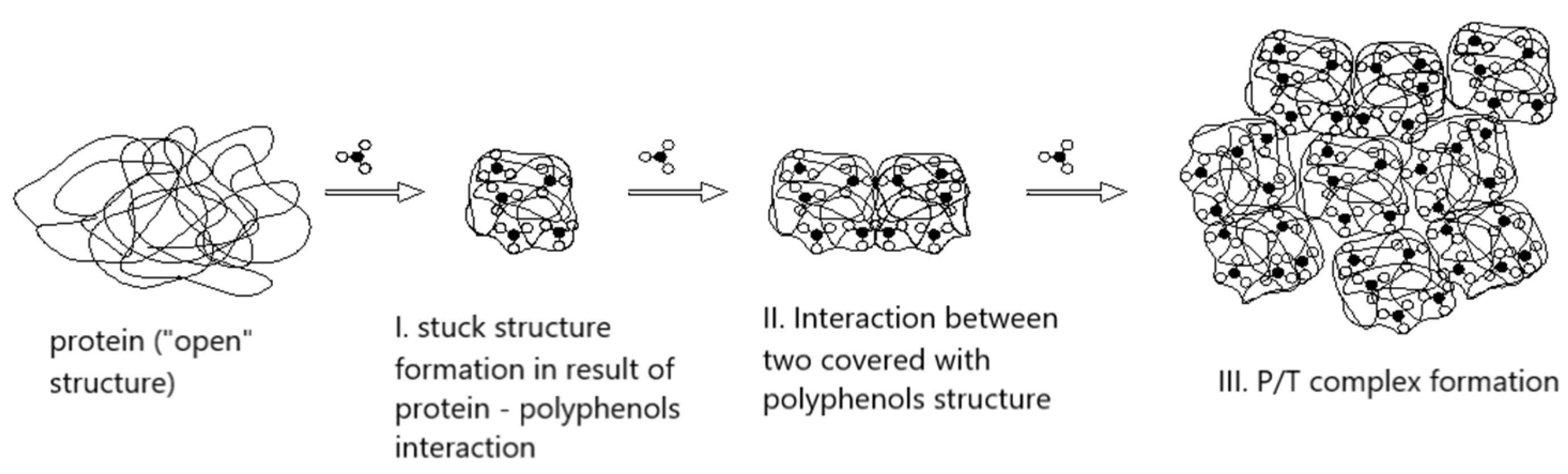

4.2. Influence of the Phenolic Compounds on the Wine Taste

5. Extractability of Grape Phenolic Compounds

- Sulfur dioxide additions [128]

6. Methods for Phenolic Compounds Determination

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. A Comprehensive Review on the Biological, Agricultural and Pharmaceutical Properties of Secondary Metabolites Based-Plant Origin. International Journal of Molecular Science 2023, 24, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N. , Anmol A., Kumar S., Wani A., Bakshi M., Dhiman Z.. Exploring phenolic compounds as natural stress alleviators in plants—a comprehensive review. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2024, 133, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherne, S.A.; O’Brein, N.M. Dietary flavonols: chemistry, food content and metabolism. Nutrition 2002, 18, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism and nutritional significance. Nutrition Reviews. 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbrone, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Advances in flavonoids research since 1992. Phytochemistry. 2000, 55, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, K.; Prenzle, P.D.; Tucker, G.; Swatsitang, P.; Glover, W. ; Phenolic compounds and their role in oxidative processes in fruits. Food Chemistry. 1999, 66, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz L.; Zeiger E.; Stress Physiology, Plant Phisiology. 3th ed.Sinauer Associates Publisher, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 2003, pp.591.

- Delgado-Vargas, F.; Jimenez-Aparcio, A.R.; Paredes-Lopez, O. Natural pigments: carotenoids, anthocyanins and betalains—characteristics, biosynthesis, processing and stability. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2000, 40, 173–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinzing, F.C.; Carle, R. ; Functional properties of anthocyanins and betalains in plants, food, and in human nutrition. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songs, J.; Smart, R.; Wang, H.; Dambergs, B.; Sparrow, A.; Qian, M.C. Effect of grape bunch sunlight exposure and UV radiation on phenolics and volatile composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot noir wine. Food Chemistry. 2015, 173, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Zaya, J.; Trousdale, E.; Salgues, M. Caftaric acid in grapes and conversion into a reaction product during processing. Vitis. 1984, 23, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Zaya, J.; Trousdale, E. Compositional changes in ripening grapes: cafftaric and coutaric acids. Vitis. 1986, 25, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Goulao, L. , Fernandes J., Lopes P., Amancio S. Tacking the cell wall of the grape berry. The Biochemistry of the Grape Berry. 2012, 172–193. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, M. Chlorogenic acids and other cinamates—nature, occurrence, dietary burden, absorption and metabolism. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2000, 80, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šikuten, I. , Štambuk P. , Andabaka Ž., Tomaz I., Markovic Z., Stupic D.,Maletic E., Kontic J., Preiner D. Grapevine as a rich source of polyphenolic compounds. Molecules. 2020, 25, 5604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buiarelli, F.; Coccioli, F.; Merolle, M.; Jasionawska, R.; Terracciano, A. Identification of hydroxycinnamic acid-tartaric acid esters in wine by HPLC—tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry. 2010, 123, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitic, M.; Obradovic, M.; Grabovac, Z.; Pavlovic, A. Antioxidant Capacities and phenolic levels of different varieties of Serbian white wines. Molecules 2010, 15, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darias-Martin, J.; Martin-Luis, B.; Carrilo-Lopez, M.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; Diaz-Romero, C.; Boulton, R. Effect of caffeic acid on the color of red wine. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002, 50, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrean, M.; Jeandet, P.; Breuil, A.; Levite, D.; Debord, S.; Bessis, R. Assay of resveratrol and derivative stilbenes in wines by direct injection high performance liquid chromatography. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2000, 51, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haygarov, V.; Yoncheva, T.; Dimitrov, D. Study of resveratrol content in grapes and wine of the varieties Storgozia, Kaylashki Rubin, Trapezitsa, Rubin, Bouquet and Pinot noir. Journal of Mountain Agriculture on the Balkans. 2017, 20, 300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Tintunen, S.; Lehtonen, P. Distinguishing organic wines from normal wines on the basis of concentration of phenolic compounds and spectral data. European Food Research Technology. 2001, 212, 90–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Laureano, O. Evolution of catechins and oligomeric procyanidins during grape maturation of Castelão francês and Touriga Francesa. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, N.; Marques, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Machado, J.; De Freitas, V. Proanthocyanidin composition of red Vitis Vinifera varieties from the Douro valley during ripening: influence of cultivation altitude. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagas, M. , Gomez-Cordoves C., Bartolome B., Laureano Ol, Ricardo da Silva J. Monomeric, oligomeric, and polymeric flavan-3-ol composition of wines and grapes from Vitis vinifera L. cv. Graciano, Tempranillo and Cabernet Sauvignon. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003, 51, 6475–6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Pinto, T.; Leandro, M.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Spranger, M. Transfer of catechins and proanthocyanidins from solid parts of the grape cluster into wine. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1999, 50, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Troup, G.; Pilbrow, J.; Hutton, D.; Hewitt, D.; Humter, C.; Ristic, R.; Iland, P.; Jones, G. Development of seed polyphenols in berries from vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2000, 6, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. , Hayasaka Y.; Vidal S.; Waters E.; Jones E. Composition of grape skin proanthocyanidins at different stage of berry development. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001, 49, 5348–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blancquaert, E.; Oberholster, A.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Deloire, A. Grape flavonoid evolution and composition under altered light and temperature conditions in Cabernet Sauvignone (Vitis vinifere L.). Front Plant Science. 2019, 8, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Freitas, V.; Glories, Y.; Monique, A. Development changes of procyanidins in grape of red Vitis vinifera varieties and their composition in respective wines. American Journal of Viticulture and Enology. 2000, 51, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Matthews, M.; Waterhouse, A. Changes in grape seed polyphenols during fruit ripening. Phytochemistry. 2000, 55, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Laureano, O. Evolution of proanthocyanidins in bunch stems during berry development (Vitis vinifera L.). Vitis. 2001, 40, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, H.; Andary, C.; Kraeva, E.; Carbonneau, A.; Deloire, A. Influence of pre- and postveraison water deficit on synthesis and concentration of skin phenolic compounds during berry growth of vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2002, 53, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Rigaud, J.; Cheynier, V.; Cheminat, A.; Moutounet, M. Procyanidin dimers and trimers from grape seeds. Phytochemistry. 1991, 30, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Gonzalez, G. , Grosskorf E., Sadgrove N., Simmonds M. Chemical diversity of flavan-3-ols in grape seeds: modulating factors and quality requirements. Plants 2022, 11, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur, C.; Rigaud, J.; Cheynier, V.; Moutonet, M. Oligomeric and polymeric procyanidins from grape seeds. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souquet, J.; Cheynier, V.; Brossaud, F.; Moutounet, M. Polymeric procyanidins from grape skin. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. , Ahmedna. Functional component of grape pomace: their composition, biological properties and potential applications. Food Science and Technologies 2013, 48, 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas, V.; Glories, Y. Concentration and compositional changes of procyanidins in grape seeds and skins of white vitis vinifera varieties. Journal of the Scienceof Food and Agriculture. 1998, 79, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obreque-Slier, E.; Pena-Neira, A.; Lopez-Solis, R.; Zamora-Marin, F.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Laureno, O. Comparative study of the phenolic composition of seeds and skins from Carmenere and Cabernet Sauvignon grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) during ripening. Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010, 58, 3591–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbertson, J.; Kennedy, J.; Adams, D. Tannin in skins and seeds of Cabernet sauvignon, Syrah and Pinot noir berries during ripening. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2002, 53, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, N.; Mitev, P.; Galabova, M.; Tagareva, S. Phenolic compounds extractability from Melnik 55 grape solid parts during grape maturity. Bio Web of Conference. 2023, 58, 01016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.; Claus, A.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Polyphenol screening of pomace from red and white grape varieties (Vitis vinifera) by HPLC-DAD-MS/MS. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004, 52, 4360–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Cardner, P.; O’Neil, J.; Crawford, S.; Morecroft, I.; McPhail, D.; Lister, C.; Matthews, D.; Maclean, M.; Lean, M.; Duthie, G.; Croizier, A. Relationshipamong antioxidant activity, vasodilation capacity and phenolic content of red wines. , Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000, 48, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin, P.; Zou, H.; Waterhouse, A. A cyclic voltammetry method suitable for characterizing antioxidant properties of wine and wine phenolics. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001, 49, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.; Waterhouse, A.; Teissedre, P. Principal phenolic phitochemicals in selected California wines and their antioxidant activity in inhibiting oxidation of human low-density lipoproteins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1995, 43, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Larrauri, C.; Saura-Calixto, F. Free radical scavenging capacity and inhibition of lipid oxidation of wines, grape juices and related polyphenolic constituents. Food Research International 1999, 32, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Orgiu, F.; Frigerio, G.; Regazzoni, L.; Sousa, L.; Bavaresco, L.; Bosso, A.; Aldini, G.; Restani, P. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of different grape (Vitis vinifera L.) varieties. BIO Web of Conference. 2019, 12, 04005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoeva, R.; Yankova, I.; Enchev, B.; Karsheva, M.; Ivanova, E.; Iliev, I. Poluphenols of grape pomace from local Bulgarian variety Mavrud. Antioxidant and antitumor effect against breast cancer., Journal of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy. 2022, 57, 508–521. [Google Scholar]

- He, F. , Mu L., Yan G.L., Liang N., Pan Q., Wang J., Reeves M., Duan C. Biosynthesis of anthocyanins and their regulation in colored grapes. Molecules. 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbrone, J.; Williams, C. Anthocyanidins and other flavonoids. Natural Products Report. 2004, 4, 539–573. [Google Scholar]

- Yoncheva, T.; Kostov, G.; Spasov, H. Content of total phenolic compounds, anthocyanins and spectral characteristics of Gamza red wines depending on the alcohol fermentation conditions. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science. 2023, 29, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- George, F.; Figueiredo, P.; Toki, K.; Tatsuzawa, F.; Saito, N.; Brouillard, R. Influence of trans-cis isomerization of coumaric acid substituents on colour variance and stabilization in anthocyanins. Phitochemistry. 2001, 57, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, G. , Hermosin-Gutierrez I., Piccardo D., Gomez-Alonso S., Gonzalez-Neves G.. Selectivity of pigments extraction from grapes and their partial retention in the pomace during red-winemaking. Food Chemistry. 2019, 277, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malien-Aubert, C.; Dangles, O.; Amiot, M. Color stability of commercial anthocyanin -based extracts in relation to the phenolic composition. Protective effect by intra- and intermolecular copigmentation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001, 49, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.; Mullen, W.; Landrault, N.; Teissedre, P.; Lean, M.; Crozier, A. Variation in the profile and content of anthocyanins in wines made from Cabernet sauvignon and hybrid grapes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002, 50, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G. Anthocyanins in grape and grape products. Critecal Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 1995, 35, 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.; Trousdale, E. Anthocyanin-tannin interaction expalaining differences in polymeric phenols between white and red wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1992, 43, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmeziane, F. , Cadot Y. , Djamai R., Djermoun L.Determination of major anthocyanin pigments and flavonols in red grape skin of some table grape varieties (Vitis vinifer sp.) by high-performance liquid chromatography—photodiode array detection (HPLC-DAD). Oeno One 2016, 50, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Cascales, I.; Ortega, A.; Lopez-Roca, J.; Fernandez, J.; Gomez-Plaza, E. ; Differences in anthocyanins extractability from grapes to wines according to variety. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2005, 56, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Matthews, M.; Waterhous, A. Effect of maturity and vine water status on grape skin and wine flavonoids. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2002, 53, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggero, J.; Coen, S.; Ragonnet, B. High performance liquid chromatography survey on changes in pigment content in ripening prapes of Syrah. An approach to anthocyanin metabolism. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1986, 37, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-San Jose, M.; Barron, L.; Diez, C. Evolution of anthocyanins during maturation of Tempranillo grape variety (Vitis vinifera) using polynominal regression models. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1990, 51, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Cosme, F.; Jordão, A.; Mendes-Faia, A. Anthocyanins profile and antioxidant activity from 24 grape varieties cultivated in two Portuguese wine region. Journal International des Science de la Vigne et du Vin. 2014, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorti, E. , Guidoni S., Ferrandino A., Novello V. Effect of different cluster sunlight exposure levels on ripening and anthocyanin accumulation in Nebbiolo grape. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2010, 61, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. , Song C., Falginella L., Castellarin S. Day temperature has a stronger effect than night temperature on anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in Merlot (Vitis vinifera L.) grape during ripening. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Moreno, A.; Perez-Alvarez, E.; Lopez-Urrea, R.; Paladinez-Quezada, D.; Moreno-Olivares, J.; Intrigliolo, D.; Gil-Munoz, R. Effect of deficit irrigation with saline water on wine color and polyphenolic composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Monastrell. Scientia Horticulturae. 2021, 283, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, S.; Nikolau, N.; Zioziou, E.; Kyraleou, M.; Kallithraka, S.; Kotseridis, Y.; Koundouras, S. Effect of post-veraison irrigation on the phenolic composition of Vitis vinifera L., cv. Xinomavaro grapes. Oeno One. International Viticulture and Enology Society. 2021, 55, 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, N.; Martinez-Luscher, J.; Porte, E.; Yu, R.; Kurtural, S. Impact of leaf removal and shoot thinning on cumulative daily light intensity and thermal time and their cascading effect of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) berry and wine chemistry in warm climates. Food Chemistry. 2021, 343, 128447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, C.; Little, D.; Glories, Y. First evidence of acetaldehyde-flavonol condensation products in red wine. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1997, 48, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T. The polymeric nature of wine pigments. Phytochemistry. 1971, 10, 2175–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T. Interactions of color composition in young red wines. Vitis. 1978, 17, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, T.; Evans, M. Evolution of red wines. An assessment of the role of acetaldehyde. Vitis. 1986, 25, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Caestellari, M.; Arfelli, G.; Riponi, C.; Amati, A. Evolution of phenolic compounds in red winemaking as affected by must oxidation. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1998, 49, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio Segade S,. Torchio F., Giacosa S., Aimonino D., Gay P., Lambri M., Dordoni R., Gerbi V., Rolle L. Impact os several pre-treatments on the extraction of phenolic compounds in winegrape varieties with different anthocyanin profiles and skin mechanical properties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 8437–8451. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokotsuka, K.; Singleton, V. Effects of seed tannins on enzymatic decolorization of wine pigment in the presence of oxidizable phenols. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Munoz, R. , Gomez-Plaza E., Martinez A., Lopez-Roca. Evolution of phenolic compounds during wine fermentation and post-fermentation: influence of grape temperature. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 1999, 12, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, K.; Boido, E.; Dellacassa, E.; Carrau, F. Yeast interaction with anthocyanins during red wine fermentation. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2005, 56, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, K. Die selection einer hefemutante zur verminderung der farstoffverluste wahreng der rotweingarung. Vitis. 1989, 28, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Escott, C. , Morata A., Zamora F., Loira I., Manuel del Fresno J., Saurez-Lepe J. Study of the interaction of anthocyanins with phenolic aldehydes in a model wine solution. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 15575–15581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, A. , Serratosa M., Merida J. Pyranoanthocyanin derived pigments in wine: Structure and formation during winemaking. Journal of Chemistry 2013, 2013, 713028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M.; Elias, R. Reaction of acetaldehyde with wine flavonoids in the presence of sulfur dioxide. Journal of the Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2016, 3, 8615–8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. , Cai Y., Haslam E. Polyphenol interactions. Anthocyanins: Copigmentation and colour changes in red wines. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1992, 59, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, S.; Stewart, R.; Norris, K. Co-pigmentation of anthocyanins in plant tissues and its effect on color. Phytochemistry. 1972, 11, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. , Yu Y., Chen Z., Wen Z., Wei F., Zheng Q., Wang C., Xiao X. Stability-increasing effects of anthocyanin glycosyl acylation. Food Chemistry 2017, 214, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Mazza, G. Copigmentation of simple and acylated anthocyanins with colorless phenolic compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1993, 41, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Brouillard, R. The mechanism of co-pigmentation of anthocyanins in aqueous solution. Phytochemistry. 1990, 29, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, R. The copigmentation of anthocyanins and its role in the color of red wine: A critical reviews. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabel, M.; Saucier, C.; Guerra, C.; Glorie, Y. Copigmentation in model wine solutions: Occurrence and relation to wine ageing. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1999, 50, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, E. In vino veritas. Oligomeric procyanidins and the ageing of red wines. Phytochemistry. 1980, 19, 2577–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Hrazdina, G. Structural properties of anthocyanins-flavonoid complex formation and its role in plant copor. Phytochemistry. 1981, 20, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranac, J.; Petranovic, N.; Dimitric-Marcovic, J. Spectrophotometric study of anthocyanin copigmentation reactions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1996, 44, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, J.; Petranovic, N.; Baranac, J. A spectrophotometric study of the copigmentation of malvin with caffeic and ferulic acid. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000, 48, 5530–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranac, J.; Petranovic, N.; Dimitric-Marcovic, J. Spectrophotometric study of anthocyanin copigmentation reactions 2 Malvin and the nonglycosidez flavone quercetin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1997, 45, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, D. , Harbertson J.; Kilmartin P.; Roginsky V.; Barsukova T.; Adams D.; Waterhouse A. Phenolics: A comparison of diverse analytical methods. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2004, 55, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, K.; Bisson, L.; Adams, D. A review of the effect of winemaking techniques on phenolic extraction in red wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2005, 56, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempereur, V.; Blateyron-Pic, L.; Labarde, B.; Saucier, C.; Kelebek, H.; Glories, Y. Groupe national de travail sur les tanins oenologiques: premier resultats. Review Frances DOenologique. 2002, 196, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Naves, A.; Spranger, M.; Zhao, Y.; Leandro, M.; Sun, B. Effect of addition of commercial grape seed tannins on phenolic composition, chromatic characteristics and antioxidant activity of red wine. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry. 2010, 58, 11775–11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Noble, A. Bitternes and astringencyof grape seed phenolics in a model wine solution. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1978, 29, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, S.; Francis, L.; Noble, A.; Kwiatowski, M.; Cheynier, V.; Waters, E. Taste and mouth-feel properties of different type of tannin-like polyphenolic compounds and anthocyanins in wine. Analitica Chimica Acta. 2004, 513, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossaud, F.; Cheynier, V.; Noble, A. Bitterness and astringency of grape and wine polyphenols. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2001, 7, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; June, H.; Nobble, A. Effects of viscosity on the bitterness and astringency of grape seed tannin. Food Quality and Preference. 1996, 7, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, H.; Gacon, K.; Schlich, P.; Noble, A. Bitterness and astringency of flavan-3-ol monomers, dimmers and trimers. Joutnal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1999, 79, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, N.; Lilley, T.; Haslam, E.; Williamson, M. Multiple interactions between polyphenols and a salivary proline-rich protein repeat result in complexation and precipitation. Biochemistry. 1997, 36, 5566–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, G.; Liao, H.; Murray, N.; Grimmer, H.; Warminski, E.; Williamson, M.; Lilley, T.; Haslam, E. Polyphenols astringency and prolin-rich proteins. Phytochemistry. 1994, 37, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarni-Manchado, P.; Gheynier, V.; Moutonet, M. Interaction of grape seed tannins with salivary proteins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999, 47, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. Nephelometric study of salivary protein-tannin aggregates. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2001, 82, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo-da-Silva, J.; Cheynier, V.; Souquet, J.M.; Moutonet, M.; Cabanis, J.C.; Bourzeix, M. Interaction of grape seed procyanidins with various proteins in relation to wine finning. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1991, 57, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury, G.; Sarni-Manchado, P.; Lefebvre, S.; Cheynier, V.; Moutonet, M. Influence of fining with different molecular weight gelatin on procyanidin composition and precipitation of wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jőbstl, E.; O’Connell, J.; Fairclough, P.; Williamson, M. Molecular model for astringency produced by polyphenol/protein interactions. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.; Butler, L. The scecificity of proanthocyanidin-protein interactions. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981, 259, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Hoff, J.; Armstrong, G.; Haff, L. Hydrophobic interaction in tannin-protein complex. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1980, 28, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, W.; Bishop, P.; Dunker, K.; Schanus, E.; Swanson, B. Interaction of synthetic proanthocyanidin dimmer and trimer with bovine serum albumin and purified bean globulin fraction G-1. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1987, 35, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, H.; Nakatsudo, F.; Murakani, K. Stoichometric studies of tannin-protein coprecipitation. Phytochemistry. 1996, 41, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarni-Manchado, P.; Deleris, A.; Avallone, A.; Cheynier, V.; Moutonet, M. Analysis and characterization of wine condensed tannins precipitated by proteins used as fining agent in Enology. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1999, 50, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokotsuka, K.; Singleton, V. Interactive precipitation between phenolic fractions and peptides in wine-like model solutions:turbidity, partical size and residual content as influenced by pH, temperature and peptide concentration. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1995, 46, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, T.; Uhlig, J.; Mehansho, H.; Putman, L.; Carlson, D.; Butler, L. Binding of condensed tannins to salivary prolin-rich glycoproteins: the role of carbohydrate. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1987, 35, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. Structural features of procyanidin interactions with salivary proteins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001, 49, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbertson, J.; Picciotto, E.; Adams, D. Measurement of pigments in grape berry extracts and wines using protein precipitation assay combined with bisulfite bleaching. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2003, 54, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Ricardo-Da-Silva, J.; Laureano, O. Tannin profiles of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Red grapes growing in Lisboa and from their monovaraietal wines. Food Chemistry. 2009, 112, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalasiri, P.; Olejar, K.; Harrison, R.; Hider, R.; Tian, B. Whole bunch fermentation and the use of grape stems: effect on phenolic and volatile aroma composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot noir wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2021, 28, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Robinson, S.; Walker, M. Grape and wine tannins: production, perfection, perception. Practical Winery and Vineyard 2007, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kovac, V.; Alonso, E.; Revilla, E. The effect of adding supplementary quantity of seeds during fermentation on the phenolic composition of wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1995, 46, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kennedy, J.; Devlin, C.; Redhead, M.; Rennaker, C. Effect of early seed removal during fermentation on proanthocyanidin extraction in red wine: A commercial production example. Food Chemistry. 2008, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorngate, J.; Singleton, V. Localization of procyanidins in grape seeds. American Journal of Enology and viticulture. 1994, 45, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillispie, E.; Miller, K.; McElrone, A.; Block, D.; Rippner, D. Red wine fermentation alters grape seed morphology and internal porosity. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2023, 74, 0740030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.; Kopp, T.; Reynolds, A.; Gliff, M. Influence of vinification treatments on aroma constituents and sensory descriptors of Pinot noir wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1997, 48, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.; Cliff, M.; Girard, B.; Kopp, T. Influence of fermentation temperature on composition and sensory properties of Semillion and Shiraz wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.; Bridle, P.; Bellworthy, S.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Reader, H.; Watkins, S. Effect of sulfur dioxide and must extraction on colour, phenolic composition and sensory quality of red table wine. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1998, 78, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, L.; Torchio, F.; Ferrandino, A.; Guidoni, S. Influence of wine-grape skin hardness on the kinetics of anthocyanin extraction. International Journal of Food Properties 2012, 15, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budić-Leto, I.; Lovric, T.; Pezo, I.; Kljusuric, J. Study of dynamics of polyphenol extraction during traditional and advanced maceration processes of the Babic grape variety. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 2005, 43, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Plaza, E.; Gil-Munoz, R.; Lopez-Roca, J.; Martinez-Cutillas, A.; Fernandez, J. Phenolic compounds and color stability of red wines: Effect of skin maceration time. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2001, 52, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.; Baters, R. Effect of skin fermentation time on the phenols, anthocyanins, ellagic acid sediment, and sensory characteristics of a red vitis rotundifolia wine. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1994, 45, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokotsuka, K.; Sato, M.; Ueno, N.; Singleton, V. Colour and sensory characteristics of Merlot red wines caused by prolonged pomace contact. Journal of Wine Research. 2001, 11, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudamore-Smith, P.; Hooper, R.; McLaren, E. Color and phenolic changes of Cabernet sauvignon wine made by simultaneous yeast/bacterial fermentation and extended pomace contact. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1990, 41, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, N.; Mitev, P.; Tagareva, S.; Kemilev, S. Influence of the process of cold maceration and non-Saccharomyces yeast application in red winemaking. Journal of Mountain Agriculture on the Balkans. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Girard, B.; Mazza, G.; Reynolds, A. Changes in anthocyanins and color characteristics of Pinot noir wines during different vinification processes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1997, 45, 2003–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N. , Liu A., Qi M., Zhang H., Huang Y., He F., Duan C., Pan Q. Enhancing the color and astringency of red wines through white grape seeds addition: repurposing wine production byproducts. Food Chemistry 2024, 23, 101700. [Google Scholar]

- Zimman, A.; Waterhouse, A. Incorporation of malvidiv-3-glucoside into high molecular weight polyphenols during fermentation and wine ageing. American Juornal of Enology and Viticulture. 2004, 55, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantz, K.; Singleton, V. Isolation and determination of polymeric polyphenols using Sephadex LH-20 and analysis of grape tissue extracts. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1990, 41, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, N.; Pinto, R.; Ruao, P.; De Freitas, V. Influence of the addition of grape seed procyanidins to Port wines in the resulting reactivity with human salivary proteins. Food Chemistry. 2004, 84, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Banuelos, G.; Buica, A.; Du Toit, W. Relationship between anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, and cell wall polysaccharides in grape and red wines. A current state-of-art review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2022, 62, 7743–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, J.; Vernhet, A.; Poncet-Legrand, C.; Cheynier, V.; Doco, T. Exploring the role of grape cell wall and yeast polysaccharides in the extraction and stabilization of anthocyanins and tannins in red wines. OENO One. 2024, 58, 7793. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, F. Role of commercial enzymes in wine production: a critical review of recent research. Journal of the Food Science and Technology. 2020, 58, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.; Rossi, J. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Nomura, N.; Patil, B.; Yoo, K. Measurement of total phenolic content in wine using an automatic Folin-Ciocalteu assay method. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2014, 49, 2364–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T.; Evans, M. Spectral evaluation of young red wines: Anthocyanin equilibria, total phenolics, free and molecular SO2, “chemical age”. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1977, 28, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, N.; Kosar, M.; Oz, A.; Mitchell, A. Advanced analytical methods for phenolics in fruits. Journal of Food Quality. 2018, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovsek, U.; Mattivi, F.; Waterhouse, A. Analysis of red wine phenolics: Comparison of HPLC and spectrophotometric methods. Vitis. 2001, 40, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Labarde, B.; Cheynier, V.; Brossaud, F.; Souquet, J.M.; Moutounet, M. Quantitative fractionation of grape proanthocyanidins according to their degree of polymerization. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999, 47, 2719–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souquet, J.M.; Labarde, B.; Le Guerneve, C.; Cheynie, V.; Moutounet, M. Phenolic composition of grape stems. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000, 48, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.; Rice, M.; Richard, N. Mecchanism of protein precipitation for two tannins, pentagalloyl glucose and epicatechin16 (4→8) catechin (procyanidin). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1998, 46, 2590–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, S.; Acena, L.; Guasch, J.; Mesters, M.; Busto, O. Quantification of phenolic compouds during red winemaking using FT-MIR spectroscopy and PLS-regression. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011, 59, 10795–10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolle, L.; Torchio, F.; Lorrain, B.; Giacosa, S.; Rio Segade, S.; Cagnasso, E.; Gerbi, V.; Teissedre, P. Rapis methods for the evaluation of total phenol content and extractability in intact grape seeds of Cabernet sauvignon: Instrumental mechanical properties and FT_NIR spectrum. Journal International des Science de la Vigne et du Vin. 2012, 46, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hernandez, C.; Salvo-Comino, C.; Martin-Pedrosa, F. ; Garcia-Cabezon, Rodriguez-Mendez M. Analysis of red wines using an electronic tongue and infrared spectroscopy. Correlations with phenolic content and color parameters. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2020, 118, 108785. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).