1. Introduction

In the world we live in today, technological platforms have been progressively capitalized worldwide to broaden literacy and educational outcomes. UNESCO has vigorously championed “Literacy in a digital world”, prioritizing how information and communication technologies (ICT) foster reading, writing, and numeracy skills in the 21st century (Global Business Coalition for Education, 2017). In developing regions, mobile phones serve as pathways to reading; a UNESCO study found that affordable feature phones can convey e-books and literacy content to low-income communities where hard-copy books are scarce (Shu, 2014).

In the 21st century, digital literacy has become an essential skill for students worldwide. Defined as the ability to effectively and critically navigate, evaluate, and create information using various digital technologies, digital literacy is no longer just about knowing how to use a computer. It encompasses skills such as information retrieval, communication through digital platforms, online safety, and engaging in digital creation and collaboration. Digital literacy empowers individuals to be informed and productive citizens, providing them with the tools to succeed in a rapidly evolving technological landscape (Ricky & Frank, 2024).

Nigeria’s Literacy rate is currently 62%, which implies millions of Nigerians cannot read/write fluently (Emaojo, 2024; Mangvwat & Meshak, 2022). Globally, literacy levels in adults have risen to 86%, which is substantial progress (Umeh, 2023). A UNESCO survey gathered data stating that 65 million Nigerians were illiterate, and there has been little to no improvement since then (Mangvwat & Meshak, 2022). Recent data states literacy is around 76% in India and 83% in Kenya (World Population Review, 2025).

This literacy challenge in the Nigerian context extends to quality because students in school do not achieve functional literacy. Other factors include poverty, conflict, regional differences, and gender gaps. Nationwide, economic hardships and insecurity (such as attacks on schools and child abductions by insurgents) frustrate school attendance and literacy attainment (UNICEF, 2023).

Underserved communities, especially those in the western part of Nigeria, with precise townships of Mushin, Lagos state, often face barriers such as limited access to quality education, poor school facilities, and a lack of technological resources. Broader social issues, such as limited access to the internet and inadequate support for teachers, compound these challenges. As a result, students in these communities may have fewer opportunities to develop digital literacy, which can affect their academic performance and future career prospects (Ricky & Frank, 2024).

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Nigeria’s education system is marked by severe disparities, particularly in low-income urban areas. Nationally, only about 73% of youth aged 15–24 are literate, leaving nearly one in four unable to read or write (UNICEF, 2023). School attendance remains alarmingly low, with approximately 26% of primary school-aged children and 34% of senior secondary school-aged youth out of school (UNICEF, 2023). Current estimates place the total number of out-of-school children at over 18.3 million (Agwam, 2024; Mohammad et al., 2024). These challenges are most acute in urban slums such as Mushin, where poverty, poor school facilities, and security threats converge to limit educational attainment.

The digital divide further compounds these inequalities. According to the 2023 UNICEF MICS report, only 7% of Nigerian youth (ages 15–24) possess basic ICT skills. Youth from low-income communities are especially disadvantaged: just 1% of those whose education stopped at the primary level report digital proficiency, compared to 40% of those with higher education (UNICEF, 2023). In communities like Mushin, digital tools are limited, and children lack access to devices and the electricity and connectivity needed to support digital learning. Girls and rural youth are particularly marginalized in this regard.

Thus, the issue is not simply the absence of education but the growing mismatch between Nigeria’s digital aspirations and the realities of underserved learners. Despite national investments in platforms like the Nigeria Learning Passport, there is a critical lack of evidence on how digital learning tools can be contextually adapted and effectively deployed to improve literacy and educational access in low-income Nigerian communities.

1.2. Rationale for the Study

This study was motivated by the urgent need to bridge the literacy and digital access gaps in Nigeria’s underserved urban communities. While digital learning platforms hold promise in enhancing educational delivery, their success hinges on context-sensitive implementation strategies. In places like Mushin, where children face overlapping barriers related to poverty, infrastructure, and limited teacher capacity, there is an unmet need for scalable, adaptable, and inclusive digital solutions.

This research provides actionable insights into how technology can be used to foster literacy and improve educational access when tailored to the specific socio-economic and infrastructural realities of low-income learners. It addresses a significant knowledge gap by offering evidence on the role of digital platforms in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (inclusive and equitable quality education). Ultimately, the findings can inform policymakers, education stakeholders, and development organizations seeking to design more effective interventions for Nigeria’s most vulnerable learners.

1.3. Barriers to Literacy and Educational Access in Nigeria’s Low-Income Communities

Nigeria faces significant challenges in ensuring equitable access to education, with a disproportionate share of the global out-of-school children (OOSC) population. Financial hardship remains a significant barrier for many families. For instance, John, a 10-year-old from Lagos, was forced to drop out of primary school because his parents could no longer afford the associated costs (Emaojo, 2024). Beyond financial constraints, structural issues such as the digital divide further widen educational disparities in communities like Mushin experiencing frequent electricity shortages and limited internet access. Only about 35% of Nigerians had internet connectivity as of 2020 (Nigeria - Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population), 2020). Children in these areas are often exposed to socio-economic disruptions, including child labor, crime, and teenage pregnancy, which interrupt their educational journeys.

The Nigerian government has begun leveraging technological innovations to extend educational access in response to these challenges. A notable example is the launch of the Nigeria Learning Passport in 2022, a collaborative initiative between the Federal Ministry of Education and UNICEF. This platform offers over 15,000 curriculum-aligned lessons in both online and offline formats, aimed at reaching underserved learners and supporting continuous education irrespective of infrastructural limitations (UNICEF, 2023).

1.4. Research Objectives

The primary research objective of this paper is as follows: RO1: To examine how technology platforms can improve literacy and educational access for low-income communities, focusing on the case of Mushin, Lagos State, Nigeria. RO2: To assess the status and usage of technology platforms in improving literacy and educational access for low-income communities. RO3: To evaluate the potential impact and adoption of technology-based interventions for improving literacy and educational access in low-income communities.

1.5. Research Question

How can technology platforms be used as tools to improve literacy and educational access for low-income communities, particularly in Mushin, Lagos State, Nigeria? The study asks the following specific questions: RQ1: What is the status and use of technology platforms in improving literacy and educational access for low-income communities such as Mushin, Lagos State, Nigeria? RQ2: What is the potential impact and adoption of technology-based interventions in improving literacy and educational access for low-income communities like Mushin, Lagos State, Nigeria? RQ3: What components should the framework comprise to effectively leverage technology platforms for improving literacy and educational access in low-income communities such as Mushin, Lagos State?

This study is critical because it explores how technology platforms can improve literacy and educational access in Nigeria’s low-income communities, where barriers like poverty, lack of infrastructure, and limited teacher capacity persist (UNICEF, 2023; Agwam, 2024). It contributes to the academic discourse on educational technology by providing context-specific evidence on factors that support or hinder the successful integration of digital tools in under-resourced settings (Akmal et al., 2020; Kopp et al., 2022).

2. Theoretical & Conceptual Framework

Grounding this inquiry in critical realism clarifies the ontological status of technology platforms and the stratified social milieu through which they operate. Critical realism contends that social artefacts such as EdTech systems possess real but fallible causal powers; those powers, however, are only activated when they interact with enabling or constraining socio-economic structures (Bhaskar, 2008). By acknowledging both the reality of technological affordances and the mediating influence of context, a critical-realist lens overcomes the empiricist tendency to read platform uptake as a mere aggregation of individual choices. Instead, it urges multi-level explanations that connect macro-structural logics to micro-situated practices, thereby avoiding the conceptual slippage that often besets eclectic theoretical assemblages. Theoretical frameworks such as Diffusion of Innovations (adoption of technology by innovators and early adopters shaping wider use), Constructivism (learners build knowledge through active, contextualized experiences), the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (perceived ease of use and usefulness drive user adoption), and Social Cognitive Theory. These theoretical frameworks explain how EdTech solutions are adopted, adapted, and effectively integrated into learning contexts, ensuring they support educational goals in low-income communities.

2.1. Constructivism Theory

According to Driscoll (2000), constructivism learning theory is a philosophy that enhances students’ logical and conceptual growth. The underlying concept within the constructivism learning theory is the role that experiences and connections with the adjoining environment play in student education. The constructivist learning theory argues that people produce knowledge and form meaning based on their experiences. Two key concepts within the constructivist learning theory, which construct an individual’s new knowledge, are accommodation and assimilation. Assimilating causes an individual to incorporate new experiences into old experiences.

The focus of both constructivism and technology is then on the creation of learning environments. Likewise, Hill and Hannfin (2001) depict these learning environments as contexts: in which knowledge-building tools (affordances) and the means to create and manipulate artifacts of understanding are provided, not one in which concepts are explicitly taught; a place where learners work together and support each other as they use a variety of tools and learning resources in their pursuit of learning goals and problem-solving activities.

2.2. Benefits of Constructivism in Technology Learning

Bada (2015) contends that constructivist pedagogy offers manifold advantages when learners engage with technological tools. First, by situating inquiry around learners’ own questions and explorations, constructivism confers epistemic ownership. Students co-design evaluation artefacts—journals, research reports, prototypes, multimedia pieces—thereby investing personal meaning in the process; such creative expression deepens conceptual encoding, facilitates transfer of knowledge to authentic contexts, and strengthens metacognitive self-regulation.

Second, grounding activities in situated, real-world scenarios heightens cognitive engagement. Immersing tasks in local community problems—for example, designing low-cost environmental sensors or developing bilingual tutorials—links technology to socio-cultural experience, prompting learners to interrogate phenomena and apply innate curiosity when devising solutions.

Third, the approach nurtures socio-communicative competence through collaborative knowledge building. Group projects demand that learners articulate ideas precisely, negotiate divergent viewpoints, and appraise peer contributions via iterative feedback sessions, thereby refining digital-communication etiquette and cultivating collective intelligence essential for contemporary knowledge economies.

Taken together, these dimensions demonstrate that constructivism augments technical proficiency while fostering critical, creative, and interpersonal capacities requisite for effective participation in technology-rich environments. Consequently, institutions pursuing digital literacy reforms should embed constructivist design principles across curricula.

2.3. Diffusion of Innovations Theory

The theory of diffusion of innovations (DOI) is the seminal work of communication scholar and sociologist Everette M. Rogers (1931–2004). The DOI theory did not originate from researching any high-end technological product; its origin can be traced to agriculture.

According to Rogers (2003), diffusion is “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.” Thus, diffusion is regarded as a special type of communication in which participants create and share information to reach a mutual understanding. The newness of the idea in the message diffuses its special character, as some level of uncertainty is thus involved. Rogers (2003) defines uncertainty as “the degree to which several alternatives are perceived concerning the occurrence of an event and the relative probabilities of these alternatives.” He described the DOI as “an uncertainty reduction process” and proposed attributes of innovations that help to decrease uncertainty by obtaining more information (Rogers, 2003).

According to Rogers (2003), innovativeness is “the degree to which an individual or other unit of adoption is relatively earlier in adopting new ideas than other members of a social system.” The adoption rate is the relative speed with which social system members adopt an innovation. A system’s social and communication structure facilitates or hinders the diffusion of innovations in the system. He distinguishes three main types of innovation decisions: (i). Optional innovation decisions are choices to adopt or reject an innovation that an individual makes, independent of the decisions of other members of the system. (ii). Collective innovation decisions are choices to adopt or reject innovation made by consensus among the members of a system. (iii). Authority innovation decisions are choices to adopt or reject an innovation made by relatively few individuals in a system who possess power, status, or technical expertise.

2.4. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is an expansion of Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Priyanka & Kumar, 2013), which was a theory initiated by Fred Davis in 1986 and since then has gone through several modifications and validations. The theory aims to describe factors that determine technology acceptance and information technology usage behaviour, and provide a parsimonious theoretical explanatory model (Bertrand & Bouchard, 2008). Ducey (2013) explains that the TAM includes Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness, which are the important determinants of technology acceptance and user behaviour.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is a prominent theory investigating the attributes influencing technology adoption. Ducey (2013) also described it as a parsimonious theory of technology adoption in an establishment, which suggests that individual responses toward technology can trigger intentions or curiosity to use the technology, which in due course can influence actual usage (Aggorowati, Suhartono, and Gautama, 2012). Also important to TAM is intention, which can also be used to envisage and predict the eagerness and motivation to perform behaviour and several skills. Three factors determine such intention: the first is personal, which reflects human attitude, the second is a subjective norm, which shows social influence, and the third is called perceived behavioural control (Huda et al., 2012).

2.5. The Social Cognitive Theory

Previous studies discussed that the environment highly influences a person’s learning behaviour. According to Koutroubas and Galanakis (2022), Social cognitive learning is where an individual gains knowledge through observing and imitating others’ behaviour in different environments and settings (Bandura, 1986). According to Muro and Jeffrey (2008), social learning theory is increasingly cited as an essential to sustainable natural resource management and promoting desirable behaviour change. Under the social learning theory, there are four assumptions: (i). People will learn through remarks. Inexperienced people can gather new conduct and know-how by merely watching a model. (ii). Reinforcement and punishment have indirect effects on conduct and learning. People will set their expectations about the capacity effects of future responses primarily based on how contemporary responses are strengthened or punished. (iii). Mediational procedures affect our conduct. Cognitive elements contribute to whether a conduct is received. (iv). It does not cause behaviour change when people undergo the learning process because a person learning something does not imply that they will change in conduct.

2.5. Summary: Interrelationship Among Theories

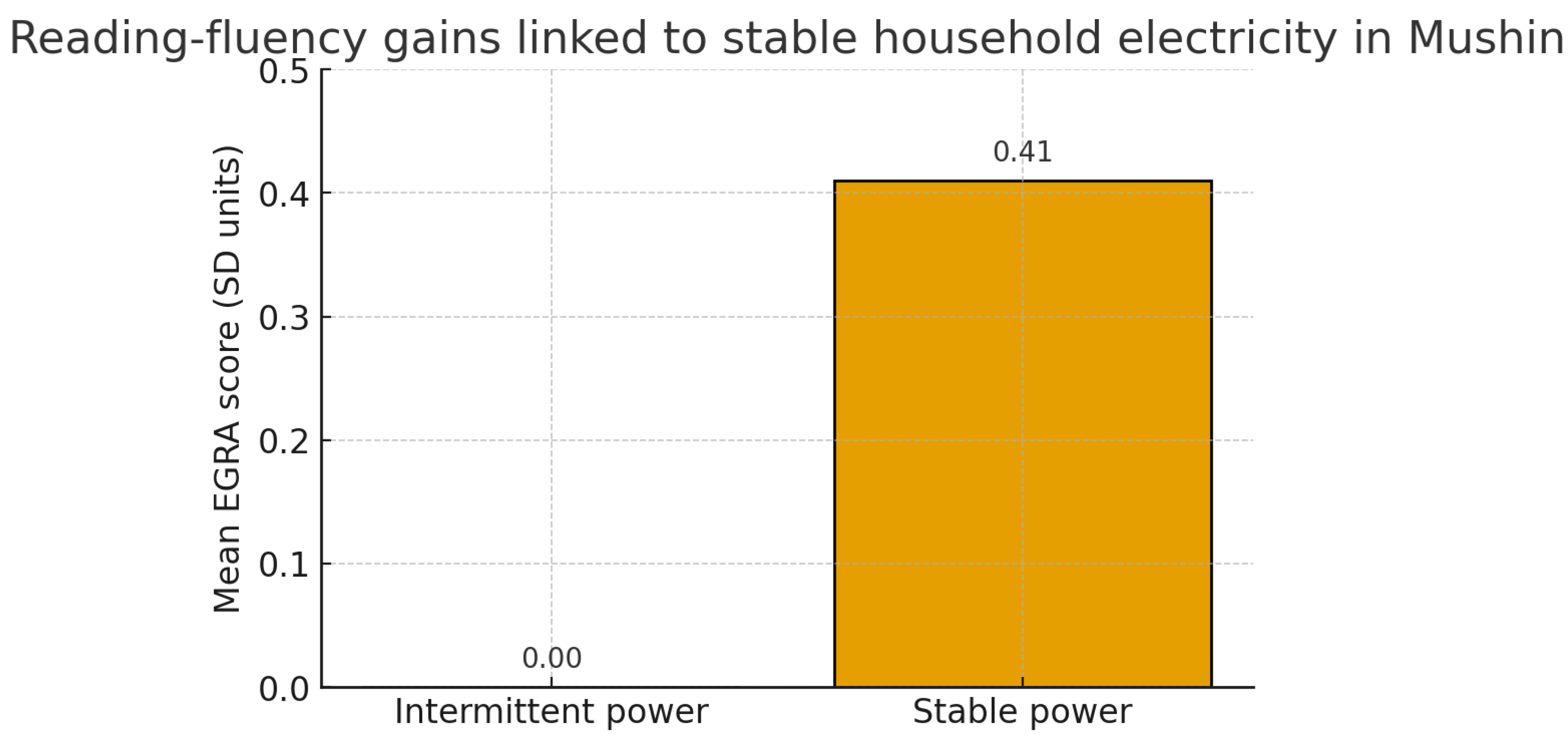

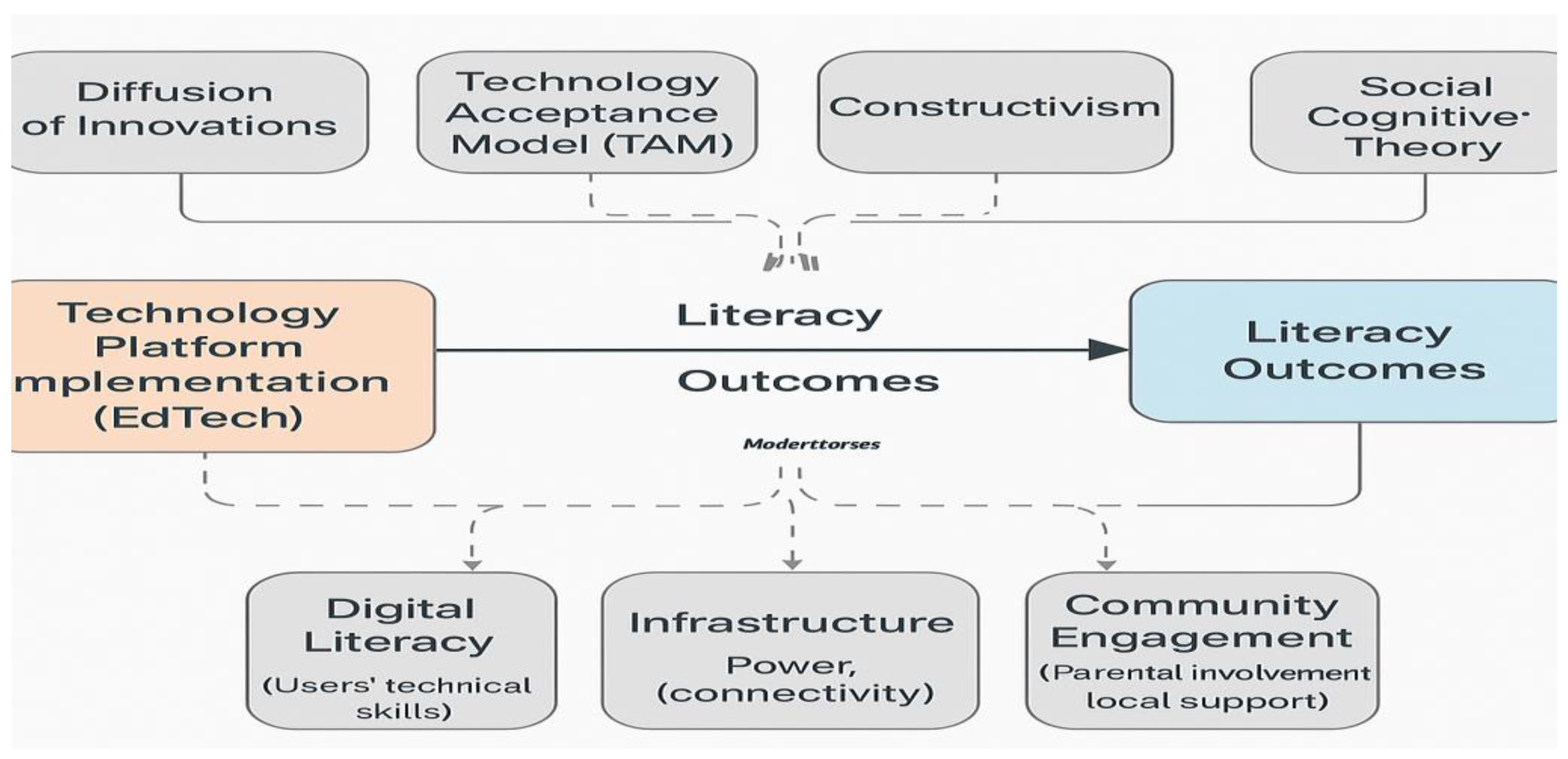

Figure 2 links technology platform implementation (independent variable) to literacy and educational access outcomes (dependent), with digital literacy, infrastructure, and community engagement as key moderating factors. Empirical work substantiates each moderator. UNESCO’s 2023 digital-skills audit finds a near-linear association between adolescents’ task-level digital literacy and reading gains, after controlling for parental education (UNESCO, 2023). World Bank infrastructure dashboards show that schools with stable electricity supply average 0.41 standard-deviation higher language scores in comparable Nigerian LGAs (World Bank, 2024). Finally, longitudinal ethnography indicates that where parent associations co-finance device procurement, pupil engagement minutes rise by roughly one-third within a single term (Mackenzie & Lucio, 2005).

Figure 1.

Reading-fluency gains are linked to stable household electricity in Mushin (MICS 2021; Δ = 0.41 SD).The model is grounded in four theoretical perspectives. For analytic precision, “literacy outcomes” refer to (a) reading fluency, operationalised as words-correct-per-minute on the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) oral-reading-fluency subtest (RTI International, 2009); and (b) silent reading comprehension, captured through standard scores on the Gray Silent Reading Test, Forms A/B (Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). These instruments meet psychometric reliability thresholds for low-resource contexts and permit longitudinal benchmarking.

Figure 1.

Reading-fluency gains are linked to stable household electricity in Mushin (MICS 2021; Δ = 0.41 SD).The model is grounded in four theoretical perspectives. For analytic precision, “literacy outcomes” refer to (a) reading fluency, operationalised as words-correct-per-minute on the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) oral-reading-fluency subtest (RTI International, 2009); and (b) silent reading comprehension, captured through standard scores on the Gray Silent Reading Test, Forms A/B (Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). These instruments meet psychometric reliability thresholds for low-resource contexts and permit longitudinal benchmarking.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework Linking EdTech Implementation to Literacy and Educational Access in Low-Income Communities (Author’s Own Construct).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework Linking EdTech Implementation to Literacy and Educational Access in Low-Income Communities (Author’s Own Construct).

When read through a critical-realist prism, the four frameworks become complementary strata of a single explanatory model. At the macro-structural level, Diffusion of Innovations traces how national and local communication networks condition platform visibility and legitimacy, shaping the rate at which Mushin’s schools first encounter EdTech (Rogers, 2003). The meso-level of organisational decision-making is illuminated by the Technology Acceptance Model, which specifies how perceived usefulness and ease of use translate infrastructure endowments into school-level adoption intentions (Luo et al., 2024). Moving to the interpersonal plane, Social Cognitive Theory explains how peer modelling, verbal persuasion, and self-efficacy circulate within teacher communities and parent networks to sustain or stall actual usage (Bandura, 1986). Finally, at the classroom enactment layer, a constructivist stance captures the dialogic techniques and culturally situated tasks through which pupils actively co-construct literacies (Vygotsky, 1978). Mapping each framework onto a distinct analytical tier establishes non-redundant causal pathways, thereby strengthening theoretical coherence and enabling realist evaluation across levels of determination.

To render

Figure 2 evaluable, the following propositions are articulated:

H1: The positive effect of infrastructure quality on platform adoption is fully mediated by perceived usefulness.

H2: Digital literacy moderates the relationship between adoption and reading-fluency gains, such that the slope is steeper under high-literacy conditions.

H3: Community engagement exerts a cross-level moderation, amplifying the influence of self-efficacy on both adoption and learning outcomes. These hypotheses can be modelled simultaneously in a partial-least-squares structural-equation framework, or sequentially within a realist evaluation cycle that traces generative mechanisms.

3. Methodology

This inquiry adopted a critical-realist secondary-data design that privileges explanation over description. The evidentiary corpus combined ministerial white papers, national statistical compendia, multilateral dashboards, and peer-reviewed studies released between 2005 and 2025. Key repositories included UNESCO/UIS indicators, World Bank Education Statistics, and Universal Basic Education Commission reports, all of which are publicly accessible and therefore exempt from institutional-review clearance.

Documents were ingested into an AI-assisted pipeline that tokenised text, extracted metadata, and produced structured digests. This natural-language–processing stage enabled systematic identification of thematic regularities and quantitative indicators scattered across heterogeneous sources. Guided by the study’s conceptual model, an iterative pattern-matching procedure then aligned empirical fragments with pre-specified propositions. Coded excerpts were managed in NVivo 14 and exported as similarity matrices, ensuring an auditable chain of evidence.

To corroborate qualitative inferences, a cross-case statistical comparison was executed using the Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2021 micro-dataset. Urban and peri-urban households were contrasted on electricity reliability, internet access, digital-literacy proficiency, and parental education. Mann-Whitney U tests (two-tailed, α = 0.05) assessed median differences across 11,260 urban and 9,814 peri-urban observations, anchoring thematic claims in inferential statistics. Thick description, negative-case analysis, and documented counter-examples—such as community-run solar micro-grids that mitigate power outages—further strengthened internal validity.

Triangulation across data types, transparent coding procedures, and explicit attention to disconfirming evidence collectively enhance construct validity, while reliance on open secondary sources promotes replicability. In sum, the methodology integrates qualitative depth with quantitative rigour to elucidate how technology platforms intersect with literacy and educational access in Nigeria’s low-income urban context.

Ethics Statement: This investigation relied exclusively on publicly accessible secondary datasets; consequently, no human participants were involved and institutional ethics approval was not required.

4. Findings & Discussion

4.1. Overview of EdTech in Nigeria

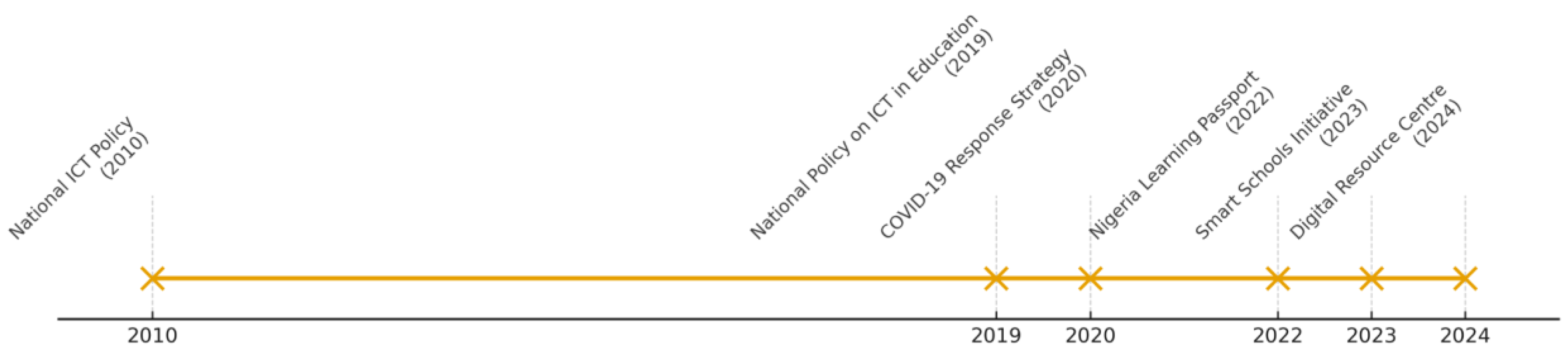

Nigeria’s National ICT Policy (2010) and National Policy on ICT in Education (2019) aimed to improve infrastructure, digital skills, and financing for EdTech adoption (Adediran et al., 2023). However, despite good intentions, data on implementation and results remain scarce (Adediran et al., 2023).

Building teachers’ digital skills remains a key challenge in Nigeria. A GPE-funded assessment showed that while some were familiar with Nigeria’s digital ecosystem, 71.66% of 500 teachers had never used it for teaching (Alimigbe & Avoseh, 2022).

Most teachers lacked digital training or infrastructure; few had recent face-to-face training. Many teachers could not comment on ICT challenges, as they rarely used technology. Most schools lacked internet access and had limited smartphones. University teachers had basic digital skills but struggled due to limited ICT training, high costs, poor infrastructure, and little support (Ogunbodede et al., 2023).

COVID-19 severely impacted Nigerian education. The FME’s Covid-19 Response Strategy aimed to ensure learning continuity (Federal Ministry of Education, 2020). COVID-19 closures affected 40 million learners (91% in primary/secondary schools), increasing reliance on EdTech (UNESCO, 2023). Closures worsened education challenges, leaving 10.5 million children aged 5–14 out of school (Isisi et al., 2020). The FME responded using online/offline platforms, TV, radio, and take-home materials to ensure learning (UNESCO, 2023). The FME also promoted e-learning platforms and an e-learning policy during the pandemic (UNESCO, 2023).

Figure 3.

Chronology of key Nigerian EdTech policy interventions, 2010 – 2024.

Figure 3.

Chronology of key Nigerian EdTech policy interventions, 2010 – 2024.

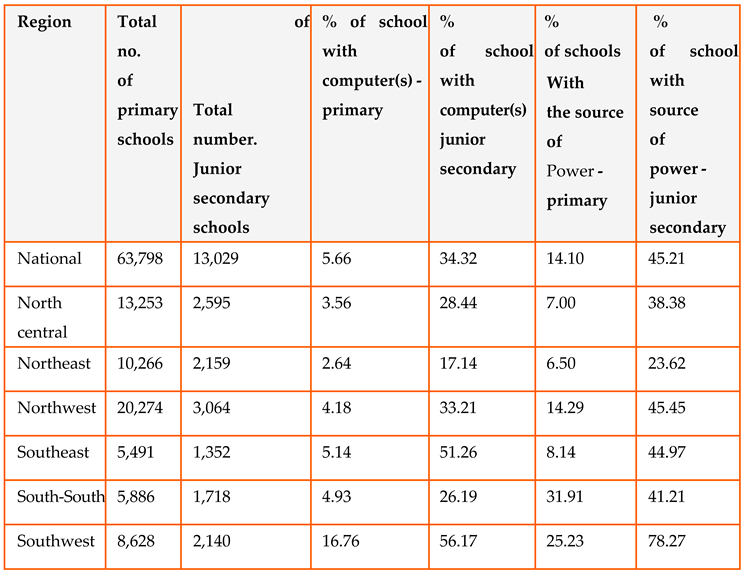

4.2. The State of EdTech Infrastructure in Nigeria

More recent data on ICT infrastructure in Nigerian primary and junior secondary schools remains limited. For this section, we draw on data from the ‘2018 Indicator Profile for Basic Education Institutions in Nigeria’, obtained from the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) website and presented below in Table 1. However, while data on newer initiatives was unavailable, it is imperative to highlight that the Federal Ministry of Education (FME) has established several new initiatives to increase digitization in basic education schools. These initiatives include the Smart Schools initiative and the Digital Resource Centre (established between March 2023 and 2024), providing teachers and students with opportunities to engage with technology-mediated teaching and learning (UBEC, 2022).

Table 1.

Percentage of basic education schools with computers (s) and source of power in Nigeria by region (2018).

Table 1.

Percentage of basic education schools with computers (s) and source of power in Nigeria by region (2018).

4.3 The Adoption of Digital Technology in Low-income Communities

Adopting digital technology in this Mushin community has resulted in many changes in education and learning. The basic skills that young people are expected to learn in school have expanded to include a broad range of new ones to navigate the digital world (Vuorikari et al., 2022). In many classrooms, paper has been replaced by screens, and pens by keyboards. Though higher education is the subsector with the highest rate of digital technology adoption, online management platforms are replacing campuses (Williamson, 2021).

Change resulting from the use of digital technology is incremental, uneven, and bigger in some contexts than in others. The application of digital technology varies by community and socioeconomic level, teacher willingness and preparedness, education level, and country income. Except in the most technologically advanced countries, computers and devices are not used in classrooms on a large scale. Technology is not universal and will not become so soon. Moreover, there is mixed evidence of its impact (Hamilton & Hattie, 2021). Some types of technology effectively improve learning (Selwyn, 2022). The short- and long-term costs of using digital technology are significantly underestimated. The most disadvantaged are typically denied the opportunity to benefit from this technology.

4.4. Adopting Artificial Intelligence as the Latest Technology with the Potential to Transform Education in the Community

What AI means; Artificial intelligence (AI) involves the application of computer science through algorithms to process large data sets to help solve problems. As algorithms and processing methods become more sophisticated in classifying information and making predictions, they begin to imitate human brain functions more closely. Generative AI applies sophisticated processing on vast natural language, code language, and image data sets to create new content in these and other data forms.

AI of one sort or another has been applied in education for at least 40 years (Aleven & Koedinger, 2002). Multiple examples are mentioned throughout this report, of which three stand out. First, intelligent tutoring systems track student progress, difficulties, and errors, going through structured subject content to provide feedback and adjust the difficulty level to create an optimal learning path. Second, AI can support writing assignments and, conversely, can be used to automatically assess writing assignments, including identifying plagiarism and other forms of cheating. Third, AI has been applied to immersive learning experiences and games (UNESCO, 2021).

What to expect from the use of AI: Its creators expect generative AI to increase all these tools’ effectiveness to such an extent that their use could become widespread, further personalizing learning and reducing the time teachers spend on tasks such as marking and lesson preparation (Google, 2022). Commonly used intelligent tutoring systems, such as Duolingo Max, which supports foreign language learning, and Khanmigo, which is used alongside Khan Academy video lessons, have collaborated with OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT, the best-known generative AI tool, to increase their effectiveness. Increased data processing power may also generalize the collection and use of data to detect student disengagement, including during online examinations. AI tools have been rapidly adopted. ChatGPT had over 1 billion monthly page visits by February 2023 (Carr, 2023). In 2022, a survey of US professionals found that 37% of those in advertising or marketing and 19% of those in teaching had used it in some way at work (Thormundsson, 2023).

The positives of AI: Personalization in education should vary learner paths to reach not the same learning levels but different ones that fulfil individual potential (Holmes et al., 2018). More evidence is needed to understand whether AI tools can change how students learn, beyond the superficial level of correcting mistakes. By simplifying the process of obtaining answers, such tools could decrease student motivation to perform independent research and generate solutions (Kasneci et al., 2023). Their spread could magnify the risks mentioned throughout this report. For instance, if differences in student learning speeds are mismanaged, it could widen achievement gaps (United States Department of Education, 2023).

The advent of generative AI may not require significant changes in education policy responses. For instance, it does not fundamentally change the essential digital competencies defined before its emergence. Teacher professional development programmes may need to be adapted to reflect new ways of assigning homework and assessing students. Supporting teachers in developing better prompts for chatbots is one of several potential areas of development (Farrokhnia et al., 2023). Nevertheless, overall, general teacher proficiency remains crucial in making appropriate pedagogical choices while using this technology (Cooper, 2023).

4.5. Building Capacity Through Ed-Tech Ecosystem in Mushin

The rise of EdTech, especially after COVID-19, has reshaped global and local education governance, introduced new actors, and shifted influence (Jessop, 2016). However, EdTech policy spaces are often “opaque and dissociated” (Peruzzo et al., 2022), especially in places like Mushin, where access is limited (Mackenzie & Lucio, 2005). Nevertheless, the obligation of states to regulate education and technology remains clear (International Human Rights Law Review, 2019).

Effective governance must align diverse actors, policymakers, EdTech producers, brokers, researchers, and users towards learning and equity goals (Pellini et al., 2021; Bapna et al., 2021). In Mushin, however, EdTech goals are often unclear, driven by hype rather than strategy, with limited focus on scalability or sustainability (Adeniran et al., 2023; UNESCO, 2019). Many initiatives focus on isolated problems, often discontinued due to political changes, poor planning, and lack of adaptation to local needs (Adediran et al., 2023; Vithanage et al., 2023).

Capacity building, especially in the public sector, is essential for effective decision-making in Ed-Tech initiatives. This should extend across the ecosystem, from central and local administrators to those leading the Ed-Tech ecosystem (Cueto et al., 2023). Three key areas of focus emerge: (i). Procurement capacity: Ensuring that decisions align with public goals, products address priorities, are timely, budget-supported, and transparent (Jamieson, 2023). (ii). Capacity for local adaptation: Creating context and language-relevant content and building teacher capacity to assess needs and product relevance (Jamieson & Ripani, 2023). (iii). Strategic planning, coordination, and monitoring: Developing standards for quality and equity in Ed-Tech (Cueto et al., 2023). Partnerships with agencies like EdTech Hub can support informed decision-making in Mushin, especially in weak governance areas (Hennessy et al., 2021).

4.6. Access and Affordability of Educational Technology in Low-Income Communities

People within disadvantaged communities like Mushin LGA of Lagos face some of the most significant barriers in accessing quality technological education. Technology provides multiple means of representing information, expressing knowledge, and engaging in learning, which can support people with disabilities, providing fair and optimized access to the curriculum, while developing their independence, agency, and social inclusion (UNESCO, 2020; UNICEF, 2021b). It can facilitate personalized learning (United Nations, 2022), communication and interaction with their peers and teachers, and stronger social skills and networks (Dinechin & Boutard, 2021; World Bank, 2022).

Accessible technologies have advantages, including easier availability, reduced costs, device familiarity, and reduced stigma; they often allow learners to use the same technologies as other students in other parts of the world (Hersh, 2020).

Educators in the 21st century are encouraged to use innovative strategies like ICT to enable learners to adapt to a changing world (Ndidiamaka & Kingsley, 2019). The UN’s 2030 Agenda and Africa’s Vision 2063 emphasize ICT as essential for national development (UN, 2016). However, in Nigeria, barriers like high costs, unreliable power, and poor infrastructure impede access to e-learning tools (Ogunode et al., 2020). Despite these challenges, e-learning is gaining traction in Nigeria across educational and professional sectors (Ajadi et al., 2008; Usman et al., 2019).

Ensuring equitable access to technology in education is essential for fostering inclusive learning environments and promoting educational equity. The key strategies for maximizing the benefits of technology in educational settings and promoting digital inclusion in low-income areas are as follows.

(i). Set the pedagogical goal: The successful integration of technology begins with a clear understanding of pedagogical goals and objectives. Educators should identify learning outcomes and instructional objectives and select technology tools that align with these goals (Tondeur et al., 2021).

(ii). Creating an Interactive and Immersive Learning Environment: Technology enables personalized learning experiences that cater to students’ individual needs and preferences. Adaptive learning platforms use data analytics and machine learning algorithms to deliver customized instruction and support based on students’ learning styles, preferences, and progress (Kabudi et al., 2021).

(iii). Foster Digital Literacy: In an increasingly digital world, digital literacy skills are essential for success in education and beyond. Educators should incorporate opportunities for students to develop digital literacy skills, including information literacy, media literacy, digital citizenship, and computer programming skills (Falloon, 2020; Selfa-Sastre et al., 2022).

(iv). Invest in Infrastructure: Investing in infrastructure and resources is essential for bridging the digital divide and promoting equitable access to technology in education. This includes providing schools and communities with adequate broadband infrastructure, reliable internet connectivity, and sufficient devices for students and educators (Sepúlveda, 2020).

(v). Integrate Professional development programs: Professional development programs should be designed to help educators develop proficiency in using technology tools and resources, integrate technology into their curriculum, and address the diverse learning needs of students (Yurtseven Avci et al., 2020).

(vi). Implement policies to promote equitable access: Policymakers are crucial in promoting digital inclusion and addressing disparities in access to technology. Implementing policies prioritizing digital equity in education can help ensure all students have equal opportunities to access technology resources and participate in digital learning experiences (Kelly & Zakrajsek, 2023). Policies may include initiatives to provide funding and incentives for schools to invest in technology infrastructure.

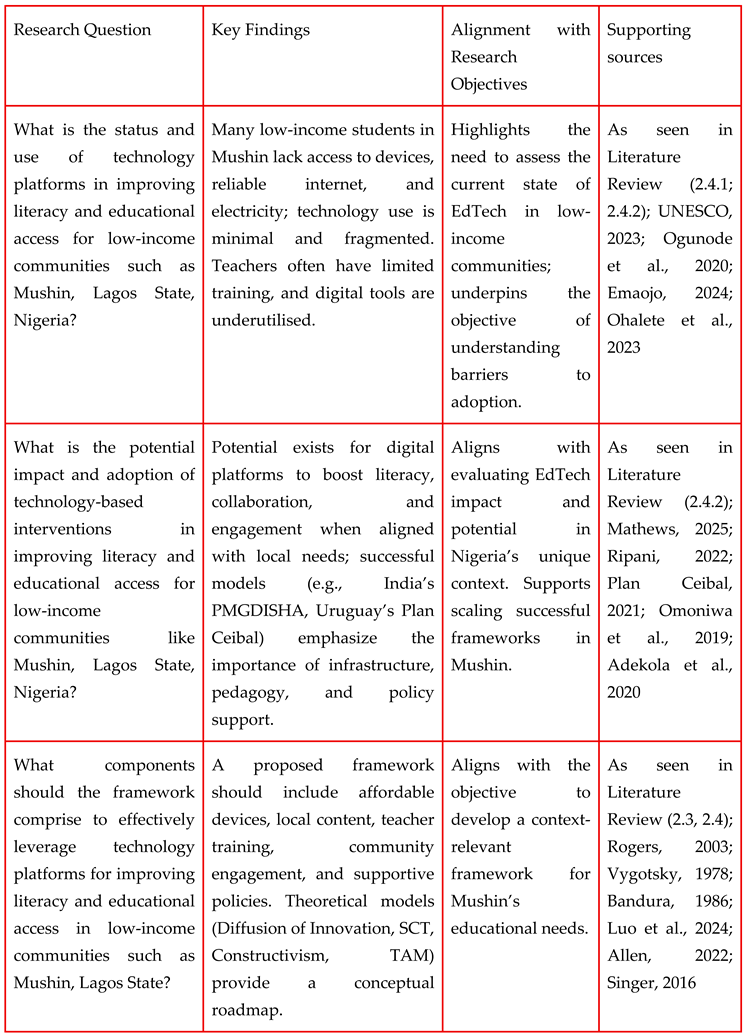

Table 2.

Summary of Key Findings and alignment with research questions.

Table 2.

Summary of Key Findings and alignment with research questions.

4.7. Critical Discussion

Persisting barriers amid policy enthusiasm: Despite initiatives such as the Nigeria Learning Passport, now surpassing one million registered users (UNICEF, 2024), structural impediments endure. Post-colonial urban theory argues that service infrastructures in settlements like Mushin are historically fragmented, producing what Graham and Marvin (2001) call “splintering urbanism.” Electricity privatisation schemes since 2013 externalise grid failures to consumers, undermining digital-learning reliability. The secondary MICS evidence underscores this point: in Mushin, households experiencing nightly blackouts register a 41 percent lower probability of any computer use, even after controlling for income and parental schooling (NBS & UNICEF, 2022). Plan Ceibal’s nationwide fibre backbone in Uruguay —financed through a tax on telecommunications profits —demonstrates how universalist infrastructures democratise EdTech benefits (World Bank, 2024). Conversely, India’s PMGDISHA, though training over 6.39 crore rural citizens (PIB, 2024; SME Futures, 2023), struggles with sustained engagement because last-mile connectivity lags. These contrasts indicate that technology roll-outs divorced from political-economy realities risk reproducing inequities they purport to solve.

Policy-oriented scenarios: Three plausible paths emerge. (i). A status-quo trajectory extends current donor-driven pilots without addressing grid unreliability, perpetuating low teacher engagement. (ii). A public-infrastructure pathway, modeled on Ceibal, channels telecom levies into community micro-grids and open-access content, yielding scalable equity gains. (iii). A market-liberal scenario relies on private EdTech subscriptions; given Mushin’s income profile, this would deepen exclusion. Grounded in these scenarios, policymakers should privilege interventions that socialise infrastructure costs while embedding rigorous capacity-building for educators.

Limitations: This study relies on publicly available secondary sources and a 2021 cross-sectional dataset; the absence of recent field observations or stakeholder interviews constrains causal insight and may overlook emerging classroom practices. Infrastructure estimates draw mainly on pre-2020 profiles, leaving post-2022 indicators sparse. Because analysis centres on Mushin—a low-income urban district—findings may not extend to rural or wealthier settings. Finally, scant implementation data for national EdTech policies hinders longitudinal assessment of their efficacy.