Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

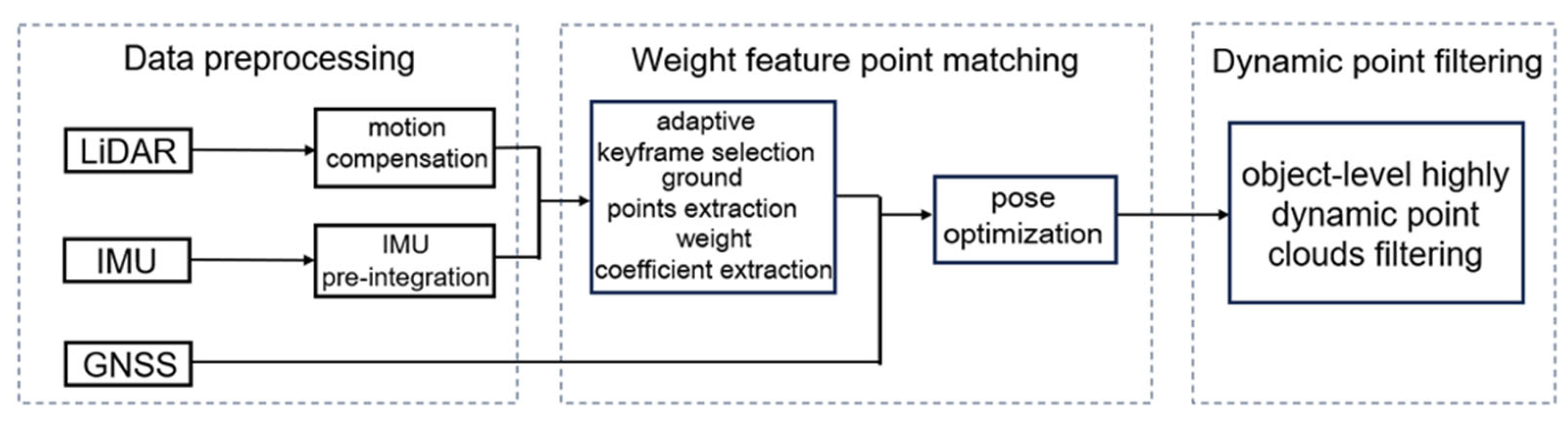

2. Algorithm Framework

3. Data Fusion for Weight Matching LiDAR-IMU-GNSS Odometry

3.1. IMU Pre-Integration

3.2. Ground Point Segmentation

3.3. Motion Compensation of LiDAR Point Clouds

3.4. Weight Feature Point Matching Method based on Geometric-Reflectance Intensity Similarity

4. Online Filtering Method for Highly Dynamic Point Clouds

5. Algorithm Validation

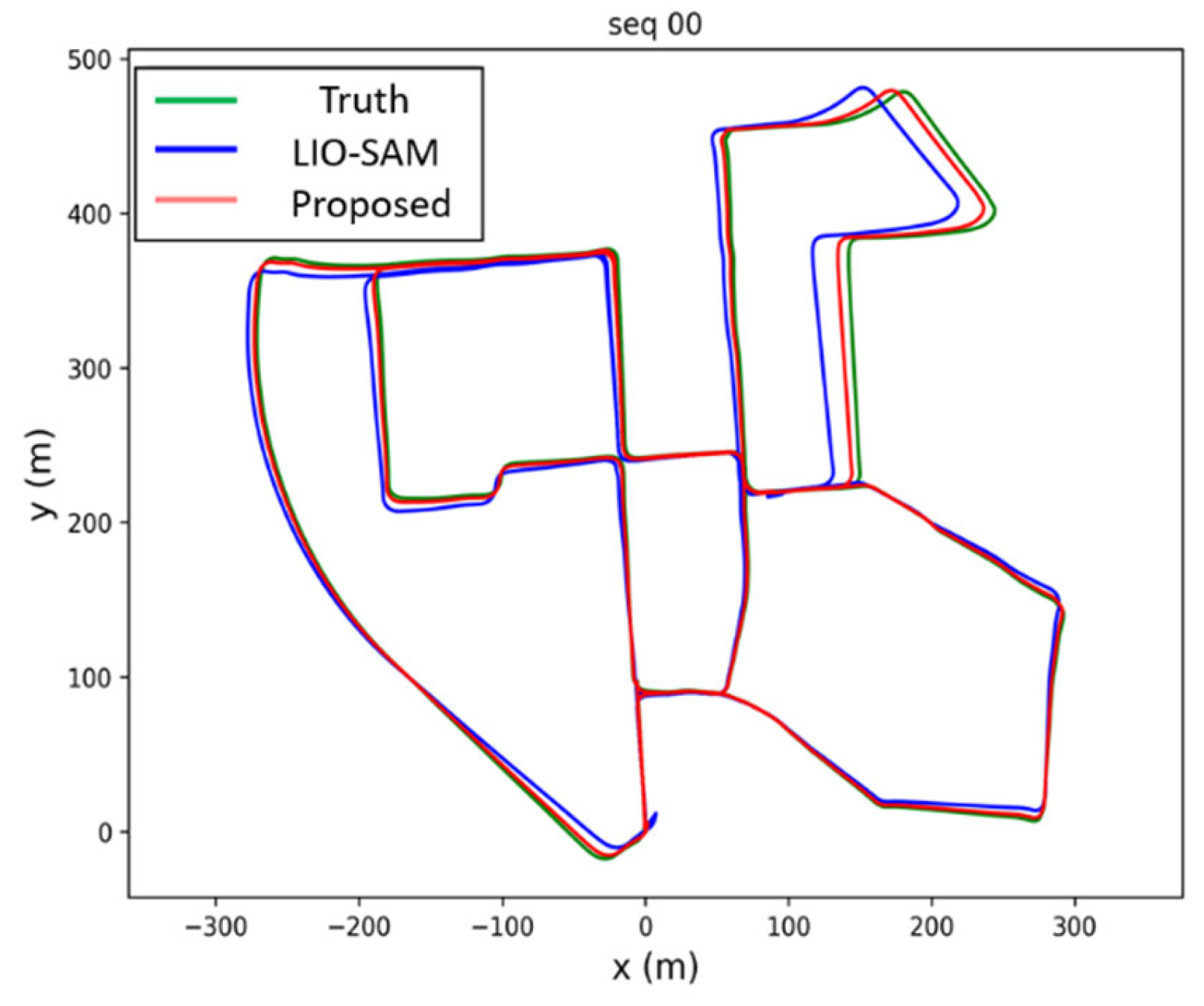

5.1. Accuracy of Proposed Odometry Systems

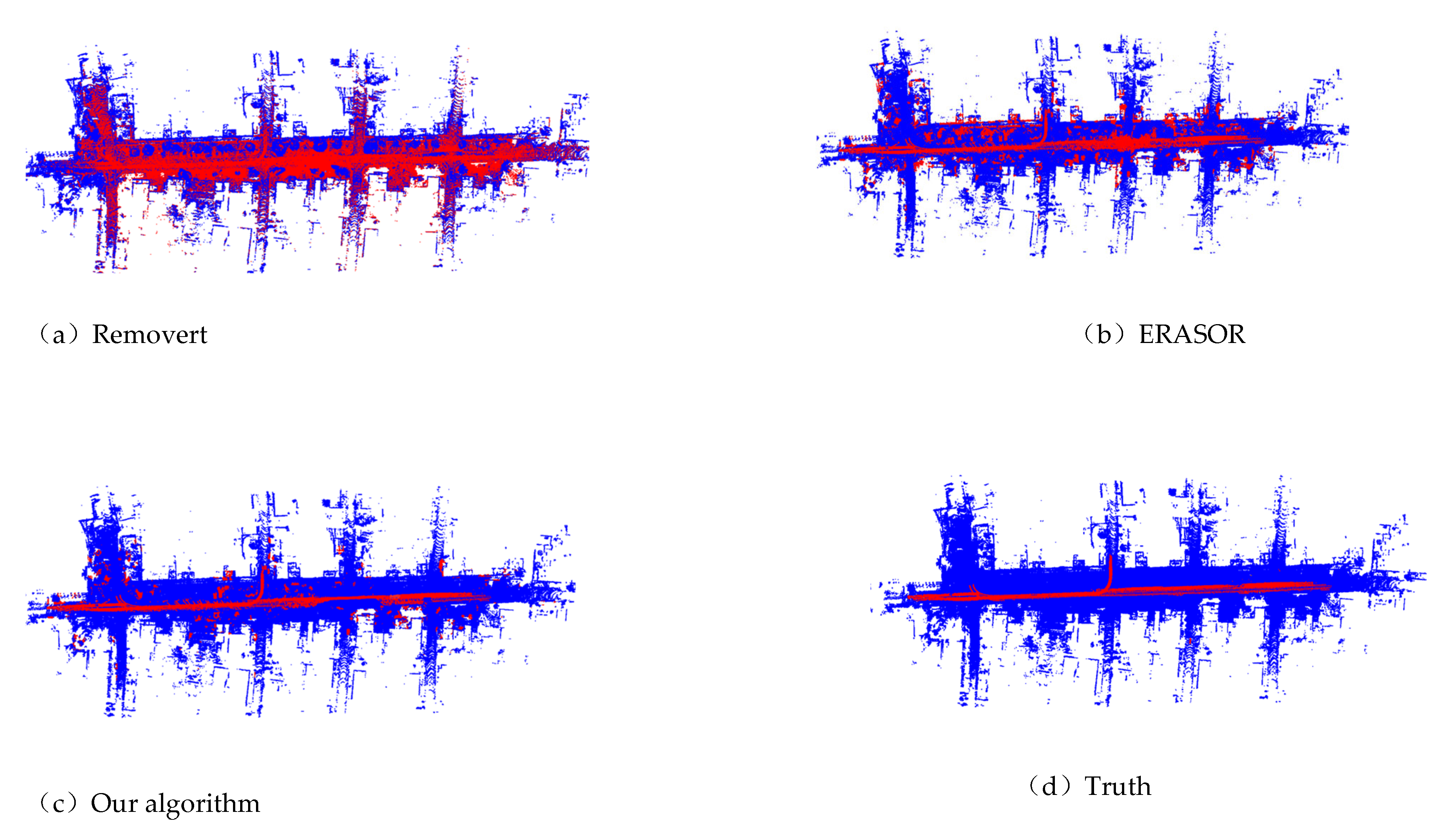

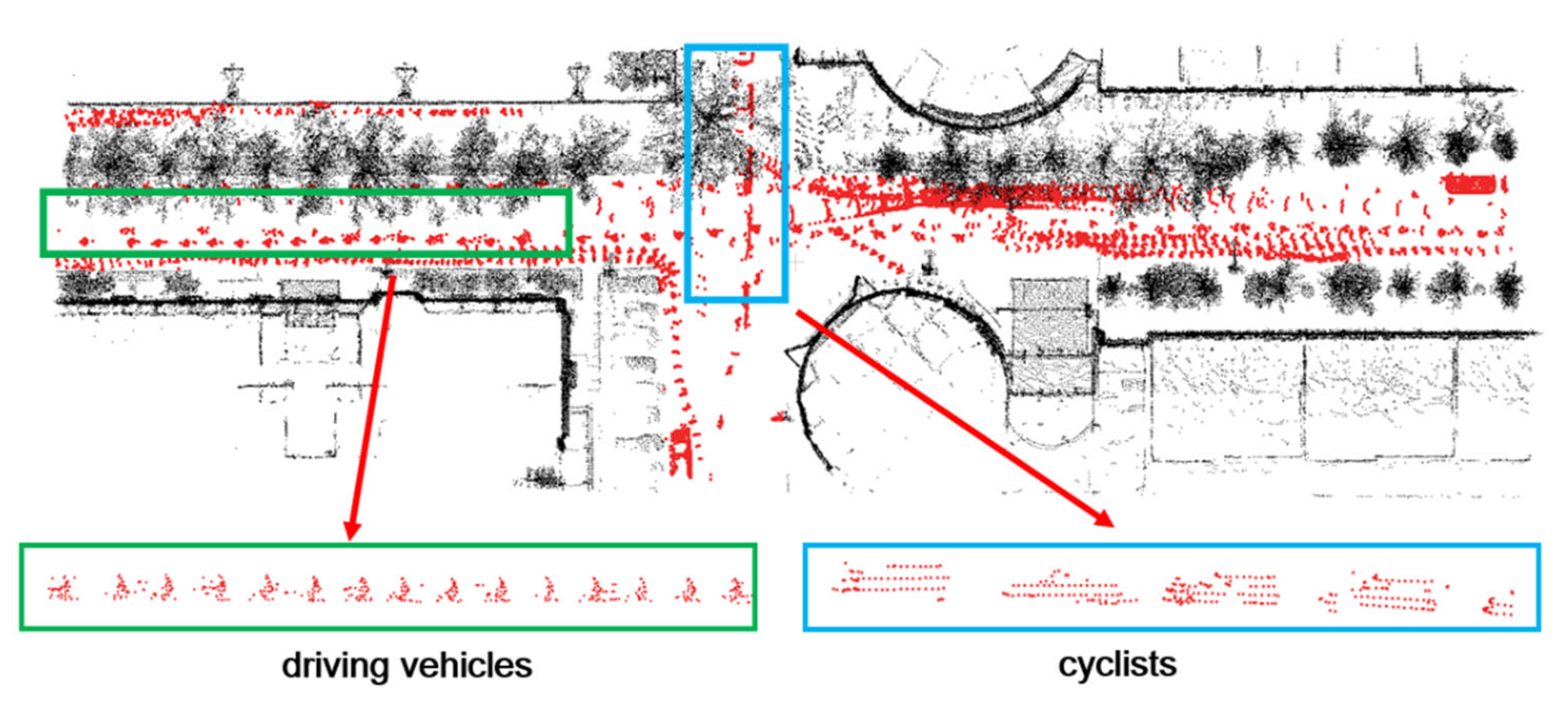

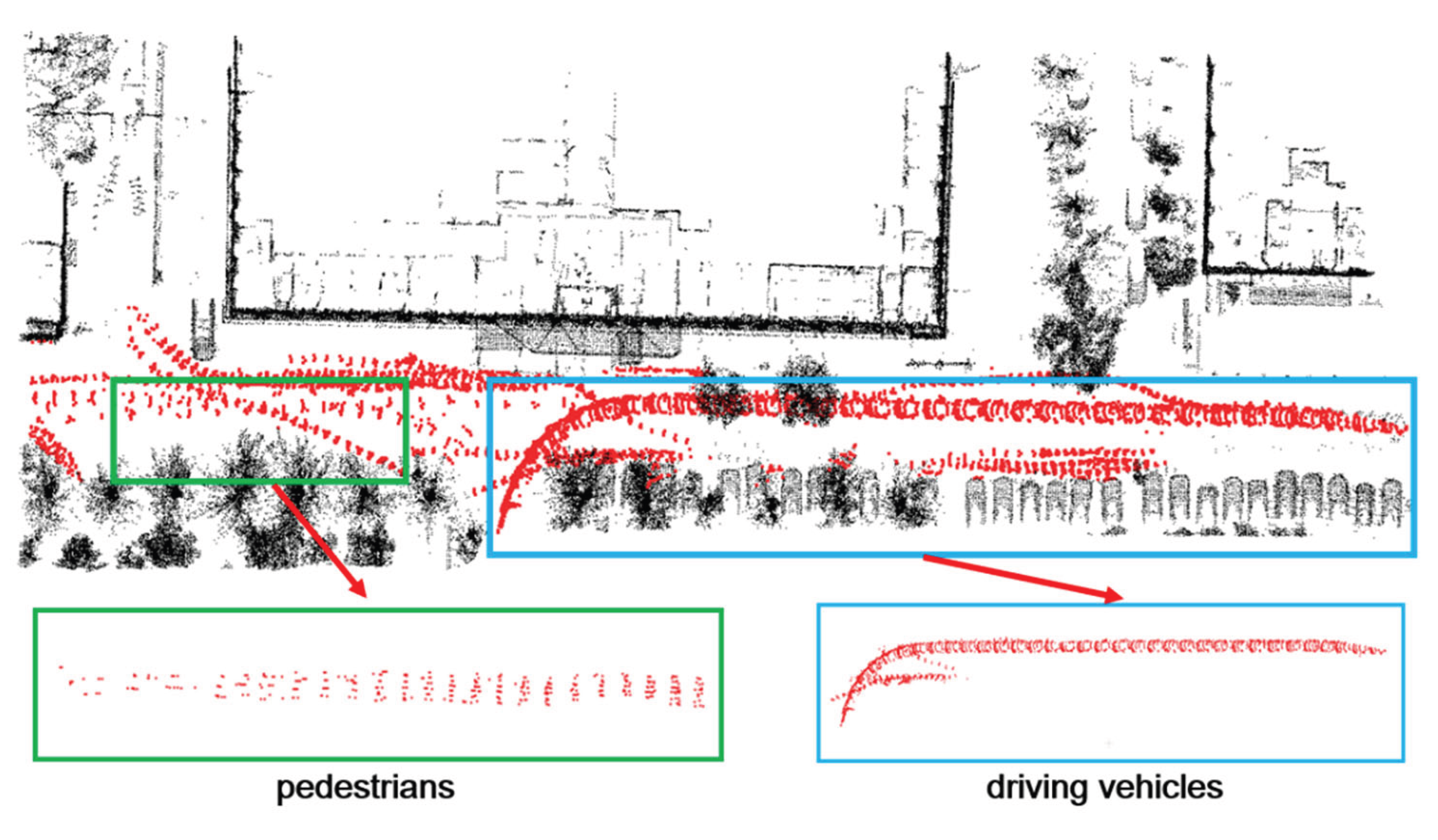

5.2. Comparison of Highly Dynamic Point Cloud Filtering Algorithm

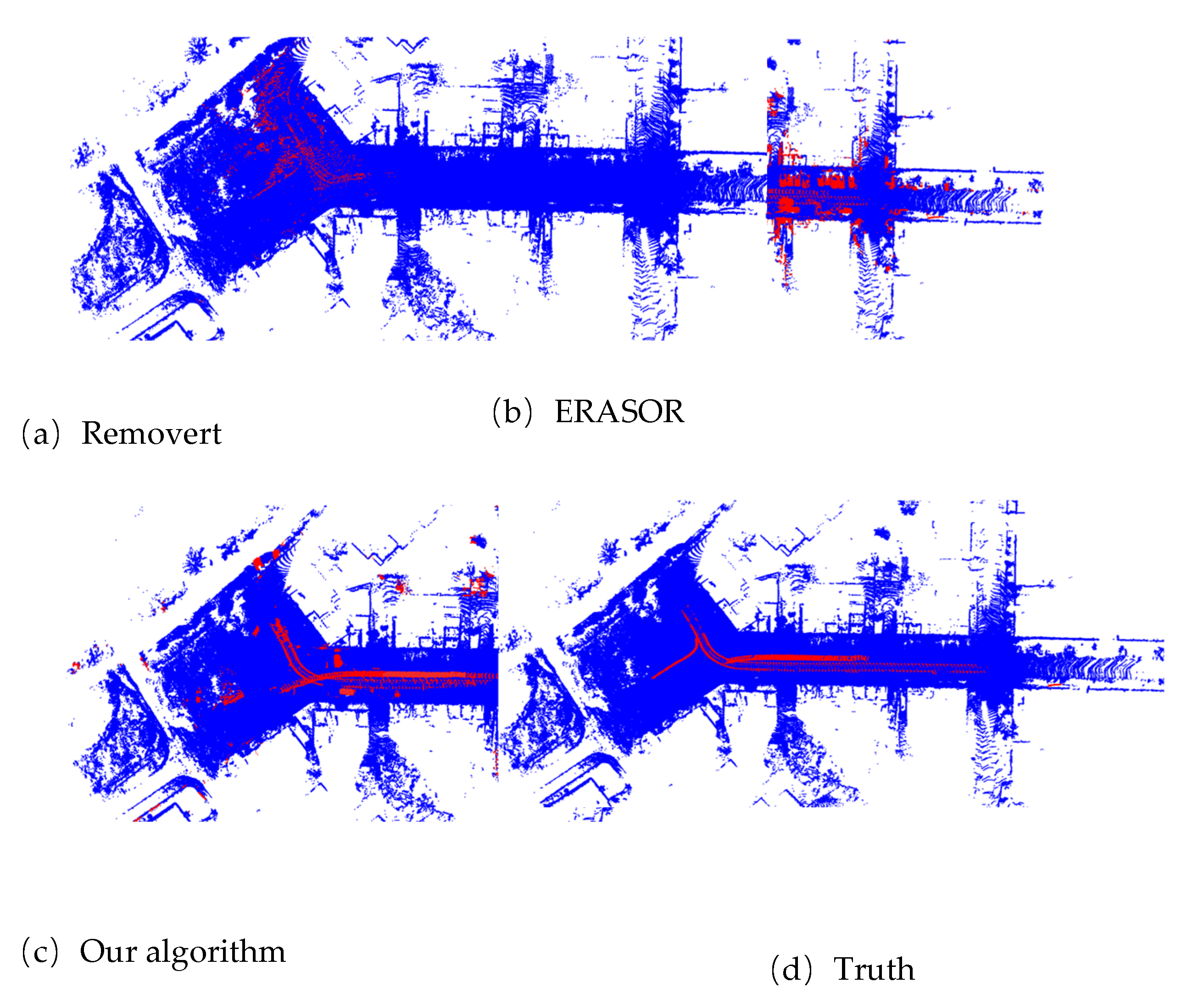

5.3. Online Filtering Experiment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faisal, A.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; et al. Understanding autonomous vehicles[J]. Journal of transport and land use 2019, 12, 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Wei, C.; Hu, J.; et al. RDP-LOAM: Remove-Dynamic-Points LiDAR Odometry and Mapping[C]//2023 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE, 2023: 211-216.

- Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Meng, S.; et al. A Survey on Occupancy Perception for Autonomous Driving: The Information Fusion Perspective[J]. 2024.

- Hu, J.; Mao, M.; Bao, H.; et al. CP-SLAM: Collaborative Neural Point-based SLAM System[J]. 2023.

- Pan, Y.; Zhong, X.; Wiesmann, L.; et al. PIN-SLAM: LiDAR SLAM Using a Point-Based Implicit Neural Representation for Achieving Global Map Consistency[J].IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2024.

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkuehler, T.; et al. 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering[J].ACM-Transactions on Graphics 2023, 42.

- Zhu, S.; Mou, L.; Li, D.; et al. VR-Robo: A Real-to-Sim-to-Real Framework for Visual Robot Navigation and Locomotion[J]. 2025.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Fu, M. Whole-body motion planning and tracking of a mobile robot with a gimbal RGB-D camera for outdoor 3D exploration[J].Journal of Field Robotics, 41:604[2025-09-08].

- Longo, A.; Chung, C.; Palieri, M.; et al. Pixels-to-Graph: Real-time Integration of Building Information Models and Scene Graphs for Semantic-Geometric Human-Robot Understanding[J]. 2025.

- Tourani, A.; Bavle, H.; Sanchez-Lopez, J.L.; et al. Visual SLAM: What are the Current Trends and What to Expect?[J]. 2022.

- Ye, K.; Dong, S.; Fan, Q.; et al. Multi-Robot Active Mapping via Neural Bipartite Graph Matching[J]. 2022.

- Hester, G.; Smith, C.; Day, P.; et al. The next generation of unmanned ground vehicles[J]. Measurement and Control 2012, 45, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; McDonald-Maier, K.; et al. Towards autonomous localization and mapping of AUVs: a survey[J]. International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems 2013, 1, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yan, L.; Xie, H.; et al. A novel lidar inertial odometry with moving object detection for dynamic scenes[C]//2022 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE, 2022: 356-361.

- Lu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Uchimura, K. SLAM estimation in dynamic outdoor environments: A review[C]//Intelligent Robotics and Applications: Second International Conference, ICIRA 2009, Singapore, December 16-18, 2009. Proceedings 2. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009: 255-267.

- Liu, W.; Sun, W.; Liu, Y. Dloam: Real-time and robust lidar slam system based on cnn in dynamic urban environments[J]. IEEE Open Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2021.

- Qian, C.; Xiang, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Rf-lio: Removal-first tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry in high dynamic environments[J]. arXiv:2206.09463, 2022.

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; et al. Lio-sam: Tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping[C]//2020 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE, 2020: 5135-5142.

- Pfreundschuh, P.; Hendrikx, H.F.C.; Reijgwart, V.; et al. Dynamic object aware lidar slam based on automatic generation of training data[C]//2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2021: 11641-11647.

- Schauer, J.; Nüchter, A. The peopleremover—removing dynamic objects from 3-d point cloud data by traversing a voxel occupancy grid[J]. IEEE robotics and automation letters 2018, 3, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Hwang, S.; Myung, H. ERASOR: Egocentric ratio of pseudo occupancy-based dynamic object removal for static 3D point cloud map building[J]. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2021, 6, 2272–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, A. Remove, then revert: Static point cloud map construction using multiresolution range images[C]//2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2020: 10758-10765.

- Behley, J.; Garbade, M.; Milioto, A.; et al. Semantickitti: A dataset for semantic scene understanding of lidar sequences[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2019: 9297-9307.

- Wen, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; et al. UrbanLoco: A full sensor suite dataset for mapping and localization in urban scenes[C]//2020 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2020: 2310-2316.

- Ramezani, M.; Wang, Y.; Camurri, M.; et al. The newer college dataset: Handheld lidar, inertial and vision with ground truth[C]//2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2020: 4353-4360.

- Park, S.; Wang, S.; Lim, H.; et al. Curved-voxel clustering for accurate segmentation of 3D LiDAR point clouds with real-time performance[C]//2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2019: 6459-6464.Author 1, A.B. (University, City, State, Country); Author 2, C. (Institute, City, State, Country). Personal communication, 2012.

| Dataset | LIO-SAM | FAST-LIO2 | Our method |

| 00 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 1.1 |

| 01 | 11.3 | 10.8 | 10.9 |

| 02 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 12.9 |

| 03 | - | - | - |

| 04 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| 05 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| 06 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 07 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| 08 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| 09 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 2.1 |

| 10 UrbanLoCo-CA-1 UrbanLoCo-CA-2 UrbanLoCo-HK-1 UrbanLoCo-HK-2 NCD-long-13 |

2.4 5.295 11.635 1.342 1.782 0.187 |

1.7 10.943 7.901 1.196 1.802 0.194 |

1.5 4.615 7.189 1.159 1.768 0.163 |

| NCD-long-14 | 0.195 | 0.212 | 0.185 |

| NCD-long-15 | 0.162 | 0.173 | 0.169 |

| datasets | method | PR | RR | F1 |

|

00 |

Removert ERASOR Our Algorithm |

86.8 93.9 98.7 |

90.6 97.0 98.5 |

0.88 0.95 0.98 |

|

01 |

Removert ERASOR Our Algorithm |

95.8 91.8 96.8 |

57.0 94.3 94.6 |

0.71 0.93 0.95 |

|

05 |

Removert ERASOR Our Algorithm |

86.9 88.7 97.5 |

87.8 98.2 96.3 |

0.87 0.93 0.96 |

|

07 |

Removert ERASOR Our Algorithm |

80.6 90.6 96.6 |

98.8 99.2 98.9 |

0.88 0.948 0.977 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).