2. Materials and Methods

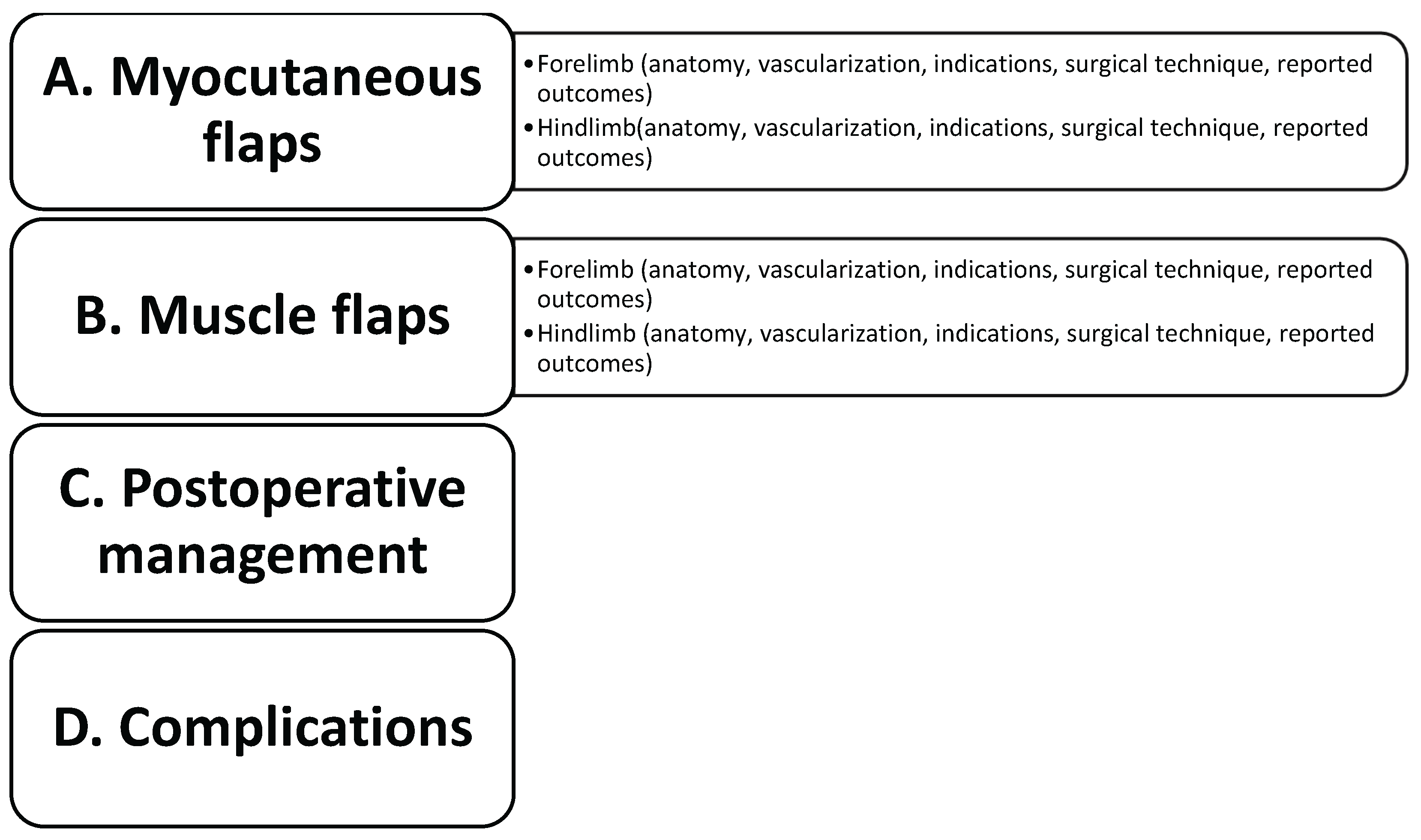

A literature search was conducted for manuscripts relating to the myocutaneous and muscle flap techniques used in the reconstruction of limb defects in dogs and cats from 1977 to 2025. NCBI-PubMed, Web of Science, and SciVerse Scopus were used exhaustively as databases. For all three databases, the search strings included the following terms: [(dog OR dogs OR cat OR cats) AND (myocutaneous flap OR muscle flap OR composite flap) AND (hindlimb OR forelimb) AND (defect OR reconstruction)]. Excluded were single editorials, proceedings, meeting abstracts and articles not written in English. The results are organized into a narrative review with different sections depending on the type of flap (myocutaneous or muscle), the site of the defects (forelimb or hindlimb), the postoperative management and the complications (

Scheme 1).

A.Myocutaneous flaps

Forelimbs

Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap

Anatomy

The latissimus dorsi is a broad, flat, triangular muscle that covers the dorsal aspect of the lateral thoracic wall. It is the largest skeletal muscle in the canine body, aside from the cutaneous trunci, and plays a role in shoulder flexion [

12,

37]. The muscle originates from the thoracolumbar fascia attached to the spinous processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae and from muscular connections to the last two or three ribs [

12,

40]. The muscle fibers converge towards the shoulder, with the cranial edge of the muscle located beneath the trapezius thoracic muscle, covering the caudal edge of the scapula. The upper end of the muscle extends over the dorsal border of the deep pectoral muscle, terminating medially in an aponeurosis of the triceps muscle [

12].

Vascularization

The latissimus dorsi is classified as a Type V muscle, possessing one dominant vascular pedicle and several secondary segmental pedicles [

45,

46]. The primary blood supply is the thoracodorsal artery and vein, while segmental vascular branches arise from the posterior intercostal arteries [

12,

40]. The ventral portion of the muscle receives additional supply from branches of the thoracodorsal artery, including dorsal and lateral thoracic arteries. These vessels also supply the overlying cutaneous trunci and skin. The dorsal portion of the muscle and the cutaneous trunci are vascularized by segmental intercostal branches [

12,

40].

Indications

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap incorporates the skin, subcutaneous tissue, cutaneous trunci, and latissimus dorsi muscle, resulting in a flap of considerable thickness and vascular reliability [

40,

47]. Although bulkier and less flexible than the cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap or thoracodorsal axial flap, it has a wide arc of rotation and sufficient length to reach various sites along the forelimb, depending on the animal’s conformation [

12]. Its favorable anatomical location, ease of elevation, versatility, and robust blood supply make it a practical and effective option for reconstructing complex soft tissue defects [

37,

46,

48,

49].

Clinically, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps are employed to manage extensive thoracic wall and forelimb defects in dogs [

12,

40]. For example, this flap has been used to reconstruct ventral thoracic wall defects following resection of rib chondrosarcomas by elevating and rotating the flap cranioventrally and securing it to the pectoral, external abdominal oblique, and remaining serratus ventralis muscles [

10,

36,

40].

The flap can be surgically split into two independent myocutaneous branches, each with its own vascular supply, enabling separate or simultaneous use. Experimental applications of the split latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap in dogs include reconstruction of complex cervical and mandibular defects. One skin paddle was used to replace a resected segment of cervical esophagus, while the other reconstructed the overlying cervical skin. Another application involved oral floor reconstruction and simultaneous labial coverage [

50].

In human medicine, the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap has a long-standing history of use, initially introduced for breast reconstruction to enhance volume and eliminate implant requirements [

51,

52]. It has been applied in pharyngeal and esophageal reconstruction [

53], as well as for extensive soft tissue defects of the upper and lower extremities, including the ankle and foot, by extending the flap through the inclusion of additional muscle while preserving donor site function [

52]. Combination of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap with iliac bone flaps has been reported for managing chronic osteomyelitis of the lower extremities [

54], and with artificial dermis and split-thickness skin grafts for treating large degloving injuries [

55]. More recent human studies have highlighted the flap’s efficacy in shoulder and back reconstruction, emphasizing minimal donor site morbidity and accelerated healing [

56]. Furthermore, its application in dynamic muscle transfer—either unilaterally or bilaterally—can restore motor function when combined with neurovascular anastomoses [

50]. A muscle-sparing version of the flap, preserving nerve integrity and donor site appearance, has also been described [

57].

Surgical technique

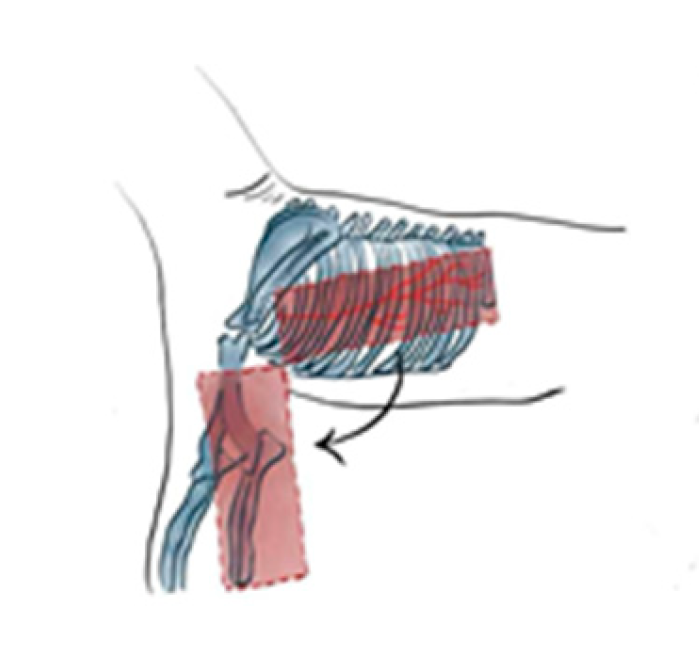

In dogs, creation of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap involves identifying anatomic landmarks including the ventral border of the acromion, the caudal border of the triceps muscle, the head of the last rib, and the distal third of the humerus (

Figure 1) [

37,

40]. The patient is placed in lateral recumbency with the forelimb extended perpendicularly to the trunk. The flap is outlined on the skin using a sterile marker. The dorsal border is drawn from a point caudal to the triceps, just below the acromion, extending caudally to the level of the last rib. The ventral border is drawn from the axillary skin fold near the lower edge of the triceps and follows a line parallel to the dorsal border, terminating at the 13th rib. The caudodorsal edge is then completed by joining the dorsal and ventral lines (

Figure 2).

The flap is initiated by incising along the ventral skin line and elevating the underlying latissimus dorsi muscle. The flap is dissected with the muscle width corresponding to the overlying skin. Segmental lateral intercostal vessels are ligated and divided, taking care to preserve the thoracodorsal artery and vein (

Figure 3). The flap is elevated and transposed to the recipient site while maintaining pedicle integrity (

Figure 4). Penrose drains or closed suction drains may be placed to minimize dead space beneath the flap or at the donor site [

12,

36,

40].

Reported Outcomes

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap has been successfully used in dogs for reconstruction of thoracic wall defects following resection of chondrosarcoma yielding a satisfactory cosmetic and functional outcome. Reported complications are generally minor including superficial skin necrosis and wound dehiscence [

36].

Cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap

Anatomy

The cutaneous trunci is a thin, sheet-like muscle originating from the pectoralis profundus and extending across the dorsal, lateral, and ventral abdominal wall. It arises caudally from the gluteal region, with fibers coursing cranially and ventrally, terminating in the axillary region where it merges closely with the latissimus dorsi and the caudal border of the deep pectoral muscle [

12,

37]. Functionally, the cutaneous trunci is responsible for the twitch reflex in response to tactile stimuli, serving as a protective mechanism against irritants along the trunk.

Vascularization

The blood supply to the cutaneous trunci muscle and its overlying skin is derived from muscular branches and short direct cutaneous arteries. These include two to four direct cutaneous branches of the thoracodorsal artery located just caudal to the border of the triceps muscle [

12,

37,

40]. The muscle maintains a close anatomical and functional relationship with the skin’s subdermal plexus, making it ideally suited for flap elevation. During surgical dissection, preserving this relationship by undermining beneath the panniculus layer is essential to maintain vascular integrity [

12].

Indications

Compared to the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap the cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap, is thinner, more flexible, and more elastic, making it particularly suitable for coverage of defects on the forelimb, especially up to the level of the elbow in dogs [

10,

40,

58].

Surgical technique

The cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap is planned and marked similarly to the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. A skin incision is made along the outlined borders, ensuring dissection does not extend beyond the subcutaneous plane between the latissimus dorsi and cutaneous trunci muscles (

Figure 5). The cutaneous trunci is carefully elevated by separating it from the loose underlying subcutaneous tissue [

12,

40]. Flap elevation is generally simpler and less invasive than that of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap [

37].

Reported Outcomes

While clinical reports are limited, an experimental study in dogs has demonstrated favorable outcomes in terms of flap survival. Ease of elevation and mobility allows extension of the flap to the carpus. Complications such as partial flap necrosis, seroma formation and dehiscence are reported with no apparent influence on flap survival [

37].

Trapezius myocutaneous flap

Anatomy

The trapezius muscle is a thin, triangular muscle divided into cervical and thoracic portions. The cervical portion is partially covered by the cleidocervicalis muscle while the thoracic portion by the latissimus dorsi muscle. It originates from the median raphe of the neck and the supraspinous ligament, spanning from the third cervical vertebra to the ninth thoracic vertebra, and inserts on the scapular spine. Functionally, the trapezius muscle assists in elevating and abducting the forelimb [

40,

59].

Vascularization

The cervical portion of the trapezius muscle receives its vascular supply from the prescapular branch of the superficial cervical artery [

60].

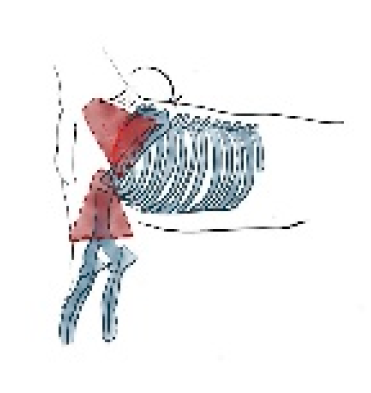

Indications

The trapezius myocutaneous flap has been used successfully in dogs to reconstruct defects involving the cervical region, cranial thorax, and proximal third of the forelimb (

Figure 6) [

40,

61]. In human reconstructive surgery, its use was first described for head and neck defect reconstruction following oncologic resection [

62].

Surgical technique

A curved incision is performed starting from the distal third of the scapular spine, arching cranially and dorsally toward the midline and terminating 5cm caudal to the wing of the atlas. A second incision, curving ventrally, is made between these points raising a triangular section of the overlying skin (

Figure 7). The cervical part of the trapezius muscle is carefully dissected, starting dorsally and progressing ventrally, while remaining in close proximity to the cleidocervicalis and omotransversarius muscles to preserve the prescapular vascular pedicle (

Figure 8), which emerges ventrally at the junction of these muscles [

61,

63].

The trapezius muscle is transected approximately 5 mm from its scapular spine insertion (

Figure 9). The accessory nerve is identified and transected caudodorsally at the point where it exits the trapezius. Branches of the prescapular vascular pedicle that lie proximal to the cutaneous and muscular supply are ligated and divided up to the origin of the acromial branch of the superficial cervical artery [

61,

63]. Incorporating bone into the flap may enhance adaptability and has been suggested for osteogenic purposes, rather than structural support [

40,

60].

Reported Outcomes

Clinical reports indicate that the free trapezius myocutaneous flap has been successfully used in dogs by using microvascular techniques. It has been applied for covering defects of tibia, tarsus and metatarsus with good functional long-term outcomes. Reported complications have been minor including infection and donor site seroma formation [

61,

63].

Hindlimbs

Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap

Anatomy

The semitendinosus is a long, fusiform muscle located on the caudal aspect of the thigh. It originates from the ischial tuberosity and inserts onto the medial tibia and, via the crural fascia, to the calcaneal tuberosity [

40].

Vascularization

Classified as a Type III muscle in dogs and cats, it possesses two dominant vascular pedicles: a proximal supply from the caudal gluteal artery and a distal supply from the distal caudal femoral artery [

31,

64,

65]. These two pedicles are capable of supporting the muscle independently [

41,

42,

65].

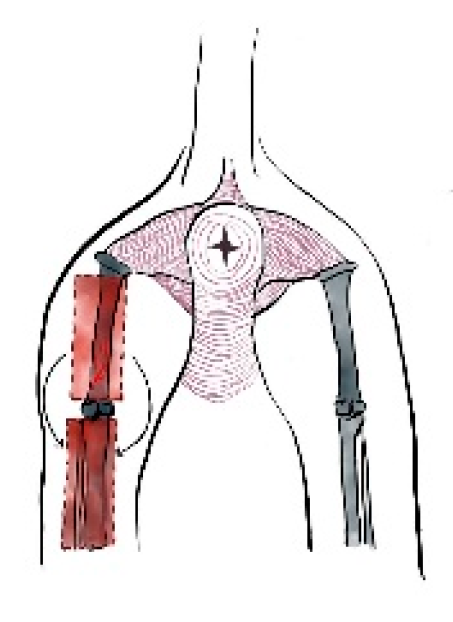

Indications

The semitendinosus myocutaneous flap has been successfully used in dogs and cats for reconstruction of distal hindlimb skin defects and tibial fractures (

Figure 10) [

6,

30,

41].

Surgical technique

The patient is placed in sternal recumbency with the affected hindlimb suspended from the surgical table. A transverse skin incision is made approximately 2–3 cm cranial to the ischial tuberosity, followed by two vertical incisions extending distally to the caudal stifle (

Figure 11). Subcutaneous tissues are dissected to expose the origins of the semitendinosus and semimembranosus muscles. The gluteal artery and vein are ligated at their entry into the proximal part of the semitendinosus. The muscle is detached from its origin on the ischial tuberosity using sharp dissection and periosteal elevation. The semitendinosus muscle, along with its overlying skin, is then mobilized distally by blunt dissection, preserving the distal vascular pedicle (

Figure 12). Without detaching the distal insertion, the flap is rotated laterally or medially to cover the tibial defects (

Figure 13). The muscle is sutured to the wound bed, and the overlying skin is closed routinely.

To create a split semitendinosus myocutaneous flap, a standard flap is first prepared as described above. Then, the muscle is longitudinally divided beginning at its origin on the ischial tuberosity and extending distally to just above the insertion of the distal vascular pedicle. The lateral or medial portion of the muscle is then rotated to the defect while preserving both pedicles. This technique increases flap versatility and minimizes donor site morbidity [

30].

Reported Outcomes

Clinical reports suggest generally favorable outcomes, although distal skin necrosis can occur, especially in feline cases, due to microcirculatory compromise [

6,

41]. Functional limb outcomes are usually preserved, with mild transient lameness in some cases [

42,

66].

B. Muscle flaps

Forelimbs

Flexor carpi ulnaris muscle flap

Anatomy

The flexor carpi ulnaris muscle in dogs comprises two anatomically and functionally distinct heads: the ulnar head and the humeral head, both of which insert on the accessory carpal bone via separate tendons [

67]. The ulnar head continues distally as a flat tendon located laterally and palmarly to the superficial digital flexor, covering the humeral head, and terminates at the apex of the accessory carpal bone. The tendon of the humeral head is positioned deeper and medially. Functionally, the flexor carpi ulnaris serves as both a flexor and abductor of the forepaw and plays an antigravity role, particularly during weight-bearing and stabilization of the carpus [

59,

68].

Vascularization

The proximal portion of the muscle receives blood from the recurrent ulnar, ulnar, and deep antebrachial arteries [

40,

69]. A distinct feature of this muscle is that, unlike other antebrachial muscles, it is also supplied by a pedicle from the caudal interosseous artery, which enters the distal aspect of the humeral head near its insertion on the accessory carpal bone [

69,

70]. These vessels form intramuscular anastomoses with branches of the ulnar and deep antebrachial arteries, contributing to a robust and redundant vascular supply.

Indications

The humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle is suitable for coverage of antebrachial, carpal, and metacarpal defects in dogs (

Figure 14). It is sufficiently large, easily accessible, relatively superficial, and expendable without causing major functional loss [

40,

69]. In human medicine, similar applications have been described for soft tissue defects around the elbow, wrist, and hand [

67,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

Surgical technique

To create a flexor carpi ulnaris muscle flap in dogs, the patient is positioned in lateral recumbency. A skin incision is made along the caudolateral surface of the antebrachium, extending from just distal to the elbow joint to approximately 1–2 cm beyond the accessory carpal bone to expose the underlying musculature. The antebrachial and carpal fascia are incised to reveal the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The antebrachial and carpal fascia are incised, and the humeral head is identified between the caudal ulnar head of the flexor carpi ulnaris and the laterally positioned ulnaris lateralis. In order to fully reveal the humeral head, the distal tendon of the ulnar head is severed. The fascial connections of the humeral head are dissected, and an incision is made at the junction of the proximal and middle third of the muscle (

Figure 15). A bridge incision is then made from the muscle flap site to the recipient wound bed. The muscle is rotated into the wound, either medially or laterally, and sutured to the surrounding tissues (

Figure 16). If the wound is not immediately closed with a skin flap or graft, the muscle surface is protected with a moist, non-adherent dressing until further closure or granulation occurs [

40,

69].

Reported Outcomes

The flexor carpi ulnaris flap has been successfully used in small- to medium-sized dogs with good healing and no significant loss of limb function. Its limited arc of rotation and flap length restrict it to distal forelimb reconstructions [

69].

Hindlimbs

Caudal sartorius muscle flap

Anatomy

The sartorius is a long, strap-like muscle that lies superficially along the medial aspect of the thigh. In dogs, it consists of two distinct bellies, cranial and caudal, each with separate innervation and vascularization. In contrast, cats possess a single-bellied, flat sartorius muscle that extends over the craniomedial thigh, with a comparable origin and insertion to that of the canine sartorius [

40,

76,

77,

78]. The caudal belly of the sartorius originates from the bony ridge located between the cranial and caudal ventral iliac spines and courses distally over the medial surface of the vastus medialis and stifle joint. Distally, it forms an aponeurosis that merges with that of the gracilis muscle [

12]. Functionally, the caudal sartorius contributes to hip flexion and medial rotation of the femur; however, it is considered non-essential due to functional redundancy with other muscles [

76].

Vascularization

The sartorius is classified as a type IV muscle based on its vascularization, receiving multiple segmental pedicles [

31,

79]. The caudal belly is primarily perfused by a pedicle arising from the saphenous artery and medial saphenous vein, typically located at the distal third of the muscle belly [

12]. This vascular pattern supports the use of the muscle as an island flap, provided that pedicle integrity is maintained during elevation [

80].

Indications

The caudal sartorius muscle flap has been utilized both for coverage of soft tissue defects involving the distal tibia and metatarsal regions [

12,

40,

76]. When the saphenous vessels are mobilized sufficiently, the flap can extend as far as the tarsocrural joint and proximal metatarsal bones, making it particularly useful for wounds in areas where local tissue is limited or compromised (

Figure 17) [

78] The sartorius muscle demonstrates many characteristics of an ideal flap donor: it is superficial, elongated, well-vascularized, and expendable [

80]. In human reconstructive surgery, prefabricated distally based sartorius flaps have been employed for soft tissue coverage around the knee joint [

81]. More recently, the sartorius muscle flap has been proposed as an alternative to the lateral gastrocnemius flap for reconstruction of lateral thigh defects following distal femoral resection due to bone tumors [

82].

Surgical technique

A skin incision is made along the medial aspect of the thigh, following the course of the caudal sartorius muscle. The subcutaneous tissue is dissected to expose the muscle, which is then transected approximately 4 cm distal to its iliac origin. The saphenous artery and medial saphenous vein are carefully isolated and double-ligated near their confluence with the femoral vessels. Care must be taken to preserve the saphenous vasculature as it runs along the medial aspect of the tibia and adjacent to the muscle’s caudal border (

Figure 18). The muscle’s insertion on the cranial tibia can be transected to allow full mobilization of the flap; the resulting island muscle flap is pedicled on the saphenous vessels. The muscle flap or the island muscle flap is then rotated to the defect and sutured into position. If necessary, the vascular pedicle may be further mobilized by extending the incision and dissecting around the vessel to increase the arc of rotation [

12,

40,

76,

83].

Reported Outcomes

Clinical reports suggest that caudal sartorius flaps offer consistent perfusion and successful coverage of distal hindlimb wounds. Few complications have been documented, and donor site morbidity is minimal. These flaps have also been employed for pelvic or abdominal wall reconstructions with good functional results [

83,

84].

Cranial sartorius muscle flap

Anatomy

The cranial sartorius is a long, flat, strap-like muscle that originates from the iliac crest and lumbodorsal fascia. It courses distally along the medial aspect of the thigh and inserts into the medial femoral fascia just proximal to the patella [

12,

84]. Functionally, the cranial sartorius contributes to hip flexion and the advancement and adduction of the thigh. However, its role is considered non-essential due to the presence of several synergistic muscles capable of performing similar actions [

84].

Vascularization

The cranial sartorius muscle receives its vascular supply primarily from a 3 cm long branch of the superficial circumflex iliac artery, which courses along the caudal margin of the muscle. Before entering the proximal third of the muscle, this artery bifurcates into ascending and descending branches, which provide segmental blood flow to the muscle belly [

85].

Indications

The cranial sartorius muscle flap has been used in dogs for the reconstruction of trochanteric pressure ulcers and abdominal wall defects (

Figure 19) [

84,

85,

86]. Additionally, it may be useful in femoral and inguinal hernia repair or prepubic tendon reconstruction [

12,

84]. In both dogs and cats, the sartorius flap has been successfully utilized for abdominal wall reconstruction, including in combination with other muscle flaps [

78,

83]. In human medicine, the cranial sartorius flap compared to the rectus femoris flap, is easier to dissect and mobilize, and its arc of rotation and superficial location make it well-suited for coverage of the greater trochanter region [

12,

85].

Surgical technique

A curved skin incision is made beginning at the greater trochanter, extending cranially toward the ventral border of the iliac wing, and then continuing distally along the craniomedial surface of the thigh to the level of the stifle joint. The skin over the greater trochanter is elevated to expose the cranial sartorius muscle. The proximal portion of the muscle is isolated using blunt dissection, and its origin is elevated from the ilium. Caution is required to preserve the primary vascular pedicle, which enters the muscle along its caudal border at the junction between the proximal and middle thirds. The muscle is transected within its distal third (

Figure 20), and the descending intramuscular branch of the primary pedicle is ligated at the transection site. The remaining muscle belly is carefully dissected free from surrounding areolar tissue, and the vascular pedicle is traced proximally toward the superficial circumflex iliac artery. Small branches of the ascending vascular supply to the tensor fasciae latae muscle are ligated and divided to improve pedicle mobility. The flap is then transposed over the debrided greater trochanteric region, using either rotational transposition or inversion, depending on the desired arc of coverage (

Figure 21). If necessary, a submuscular tunnel is created beneath the cranial portion of the tensor fasciae latae muscle to pass the sartorius muscle and its pedicle through to the defect. The muscle’s edge is then sutured to the adjacent fascia [

85].

Reported Outcomes

Clinical application of the cranial sartorius flap has demonstrated effective wound coverage with minimal functional impact. It provides reliable perfusion for covering the greater trochanter, and its versatility allows it to be considered for a range of abdominal and pelvic reconstructions. No major complications have been reported in the literature [

83,

84,

85].

Semitendinosus muscle flap

Indications

The semitendinosus muscle flap has been applied in various reconstructive procedures in dogs and cats. Its reliable vascular anatomy, robust size, and arc of rotation make it well-suited for both orthopedic and soft tissue reconstructions. In dogs, the semitendinosus muscle flap has been used for Achilles tendon repair [

42], the management of perineal conditions, including external anal sphincter incompetence, perineal hernia, imperforate anus, and retrovaginal fistula [

85,

87,

88] and for rectal wall repair or reinforcement in both a dog and a cat [

89].

A split semitendinosus muscle flap has been utilized to reinforce the pelvic diaphragm in ventral perineal hernia repairs in dogs [

90], and the technique has also been reported in a cat with a similar condition [

91]. More recently, a bifurcated semitendinosus muscle flap has been developed for the treatment of fecal incontinence in dogs, showing promising clinical results [

92].

Surgical technique

The patient is positioned in lateral or sternal recumbency, depending on the indication and surgical approach.

For Achilles tendon reconstruction, a skin incision is made along the caudolateral aspect of the limb, beginning 2–3 cm proximal to the ischial tuberosity and extending distally to the calcaneus. Subcutaneous tissues are dissected to expose the semitendinosus muscle and its surrounding fascia. The caudal gluteal artery and vein are identified and ligated at their entry point into the proximal muscle. The lateral half of the semitendinosus is detached from its origin on the ischial tuberosity using sharp and blunt dissection, then dissected distally to the level of the caudal femoral artery. The resulting flap is rotated 180° distally and secured to the Achilles tendon remnant or calcaneus as part of the tendon repair procedure [

42].

In patients undergoing perineal hernia repair, the surgical approach varies depending on whether the procedure is combined with internal obturator muscle transposition. If so, the skin incision is extended from the ventral aspect of the contralateral ischiatic tuberosity. If performed alone, the incision begins approximately 3 cm lateral to the tail base, extending ventrally across the perineal midline to the opposite ischiatic tuberosity. It is then continued distally along the contralateral caudal thigh to the popliteal region. The semitendinosus muscle may be: a) transected at midbelly and rotated beneath the anus to support the pelvic diaphragm [

91], or, longitudinally split into medial and lateral halves, with both the proximal and distal vascular pedicles preserved. The medial portion is transected distally and rotated beneath the anus to the contralateral perineum [

90]. The flap is secured to surrounding anatomical structures, including the coccygeus muscle, sacrotuberous ligament, external anal sphincter, internal obturator, ischiourethralis, and bulbospongiosus muscles, as well as the fascia of the ischiatic tuberosity to ensure adequate pelvic floor reconstruction and long-term support [

90].

Reported Outcomes

Generally effective, although distal skin necrosis can occur, especially in feline cases, due to microcirculatory compromise [

6,

41]. Functional limb outcomes are usually preserved, with mild transient lameness in some cases [

42].

C. Postoperative managementof myocutaneous and muscle flaps

Appropriate postoperative care is vital to ensure the success of muscle and myocutaneous flap procedures in dogs and cats. Optimal outcomes depend on a combination of pain management, infection control, wound care, and activity restriction to support flap viability and tissue integration. The surgical site should be monitored at least twice daily for signs of dehiscence, necrosis, infection, or seroma formation. Rectal temperature is also monitored regularly during hospitalization to detect systemic infection [

63,

75].

Analgesia

Effective pain control is essential in the immediate and early postoperative period and a multimodal approach combining opioids, non-opioid analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s), gabapentinoids and peripheral or neuraxial local anaesthetics acting on different sites of the pain pathway. For the first 24-48 hours a combination of locoregional anaesthesia and constant rate infusion of drugs is preferred [

36,

66,

87,

90]. The degree and duration of the postoperative pain management is based on the type of surgery and on the patient’s pain score according to current recommendations [

6,

30].

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

To minimize the risk of surgical site infection, cephalexin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid is commonly administered during the early postoperative period in both dogs and cats [

6,

36,

87]. Antibiotic therapy is often continued for 5–7 days, based on culture and sensitivity tests and depending on the extent of surgery and the presence of underlying contamination or infection. Although widely used, there are currently no published studies specifically addressing antibiotic protocols for reconstructive procedures involving the use of muscle or myocutaneous flaps on limbs in veterinary medicine.

Wound Protection and Monitoring

Use of an Elizabethan collar is recommended in all cases to prevent self-inflicted trauma to the surgical site. The collar should be maintained until the wound has fully healed, usually between 10 and 21 days postoperatively [

6,

86,

87]. In subdermal and axial pattern flaps the placement of drainage does not seem to affect complication rates [

93,

94]. In muscle and myocutaneous flaps there are not such studies. Therefore, the decision is based on the surgeon’s preference and on the individual case.

The wound is generally covered with a sterile bandage, which is changed daily during the first postoperative week and subsequently every other day until complete epithelialization or stable granulation tissue is present [

6,

42]. Bandaging provides wound protection and mechanical support for the flap.

Activity Restriction

Strict activity restriction is advised for 2–4 weeks following surgery, depending on the location and extent of the flap. Excessive movement can lead to flap tension, vascular compromise, or premature dehiscence. Cage rest or confinement to a small area is advised, particularly for limb and perineal reconstructions [

36,

42].

D. Complications

Complications related to the use of muscle and myocutaneous flaps in dogs and cats are primarily influenced by factors such as preoperative planning, surgical technique, and postoperative care. Errors during flap elevation and transposition, as well as inadequate tissue perfusion, are common causes of flap-related morbidity [

10,

29]. Additionally, underlying systemic disease and inadequate pain control may increase the risk of flap failure or delayed healing.

Complications are characterized as minor or major. Minor require minimal intervention and can heal by second intention whereas major require an additional surgery to achieve closure [

93,

94].

Commonly reported minor complications include dehiscence (6-50%), seroma (0-100%), oedema (20-75%), infection (40-100%) and delayed healing (20%) [

36,

66,

69,

76,

84,

85]. Wound dehiscence is often associated with excessive movement or skin tension [

36]. Seroma formation is typically managed conservatively with drainage [

85]. Soft tissue swelling and hemorrhage at the donor or recipient site is another potential complication [

66,

69,

76]. Surgical site infection might require extended antibiotic therapy [

76,

84]. Delayed wound healing, is often linked to ischemia, tension, or flap instability [

42].

The most frequently reported major complications are partial or full-thickness necrosis, particularly affecting the distal portion of the flap. In cats, full-thickness necrosis of the skin (79-86%) overlying the distal end of the semitendinosus myocutaneous flap has been observed when used for hindlimb full-thickness defects. This was attributed to perfusion deficits or microvascular compromise [

6,

30]. In dogs, skin necrosis distal to the muscle belly was also reported following application of the semitendinosus flap to reconstruct a complex open tibial fracture [

41].

Functional complications, though rare, have also been documented. Lameness has been reported in one study following cranial and caudal Sartorius muscle flaps’ transfer to the medial surface of the tibia [

76,

84]; in another study with semitendinosus flap use for Achilles tendon repair in 20% of the dogs [

41]; and finally in 18% of cases with perineal hernia [

66]. However, limb function returned quickly without the need for prolonged immobilization.

While these complications are noteworthy, most can be minimized through appropriate surgical planning, flap selection, tension-reducing techniques, and careful postoperative monitoring.

Conclusions

Myocutaneous and muscle flaps are valuable tools for the reconstruction of complex limb defects in dogs and cats. These flaps offer robust vascularity, enabling coverage of wounds involving bone, tendons, or infected tissue where skin grafts alone would fail. Among the flaps reviewed, the latissimus dorsi, cutaneous trunci, trapezius, sartorius, semitendinosus, and flexor carpi ulnaris flaps have demonstrated reliable outcomes with relatively low complication rates when proper surgical planning and postoperative care are applied.

Future Directions

Despite favorable clinical reports, current evidence remains limited to retrospective case series, experimental models, and a small number of prospective trials. Complications such as distal necrosis, dehiscence, seroma formation, and transient functional deficits have been reported inconsistently across studies. These are often attributable to tension at the recipient site, vascular compromise, or inadequate immobilization. Furthermore, most studies focus on immediate or short-term outcomes, with few assessing long-term limb function, quality of life, or flap durability.

To enhance clinical application and support evidence-based flap selection, further research is warranted in the areas of long-term outcome evaluation, quantitative perfusion studies to optimize flap design, and biomechanical assessment of reconstructed limbs.

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the sections.

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the sections.

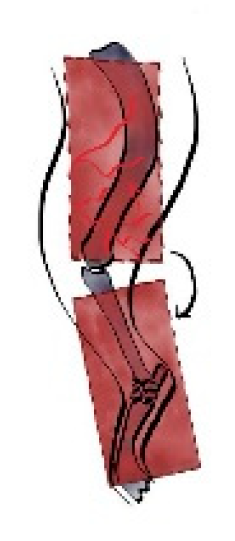

Figure 1.

Anatomic landmarks of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous; including the ventral border of the acromion, the caudal border of the triceps muscle, the head of the last rib, and the distal third of the humerus and arc of rotation to the forelimb.

Figure 1.

Anatomic landmarks of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous; including the ventral border of the acromion, the caudal border of the triceps muscle, the head of the last rib, and the distal third of the humerus and arc of rotation to the forelimb.

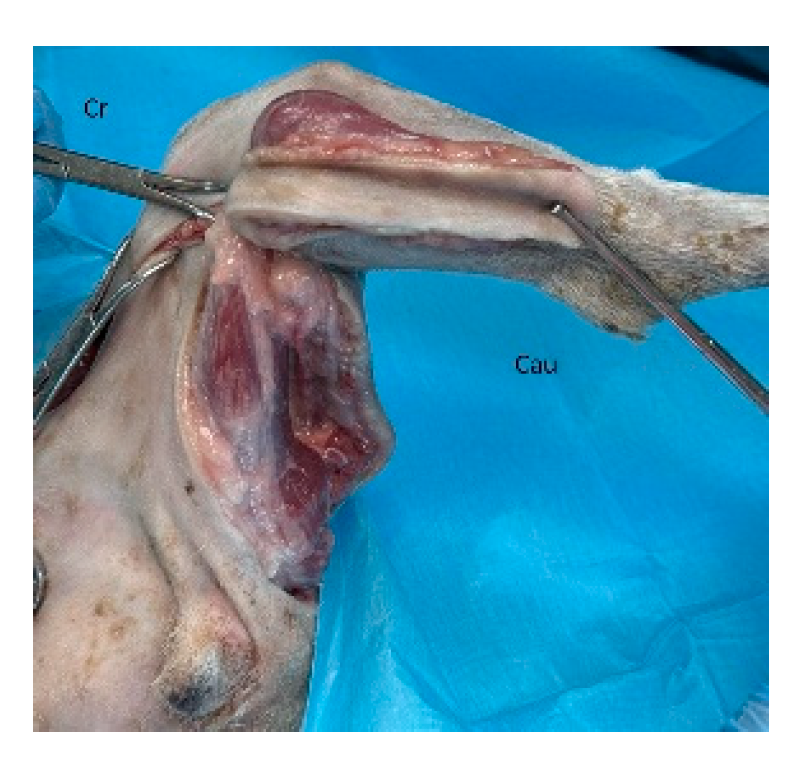

Figure 2.

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is outlined on the skin using a sterile marker. The dorsal border is drawn from a point caudal to the triceps, just below the acromion, extending caudally to the level of the last rib. The ventral border is drawn from the axillary skin fold near the lower edge of the triceps and follows a line parallel to the dorsal border, terminating at the 13th rib. The caudodorsal edge is then completed by joining the dorsal and ventral lines. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 2.

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is outlined on the skin using a sterile marker. The dorsal border is drawn from a point caudal to the triceps, just below the acromion, extending caudally to the level of the last rib. The ventral border is drawn from the axillary skin fold near the lower edge of the triceps and follows a line parallel to the dorsal border, terminating at the 13th rib. The caudodorsal edge is then completed by joining the dorsal and ventral lines. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

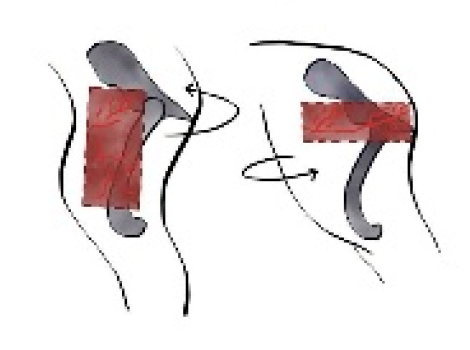

Figure 3.

The flap is dissected and elevated incorporating the latissimus dorsi muscle. Segmental lateral intercostal vessels are ligated and divided, taking care to preserve the thoracodorsal artery and vein (black arrow). Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 3.

The flap is dissected and elevated incorporating the latissimus dorsi muscle. Segmental lateral intercostal vessels are ligated and divided, taking care to preserve the thoracodorsal artery and vein (black arrow). Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

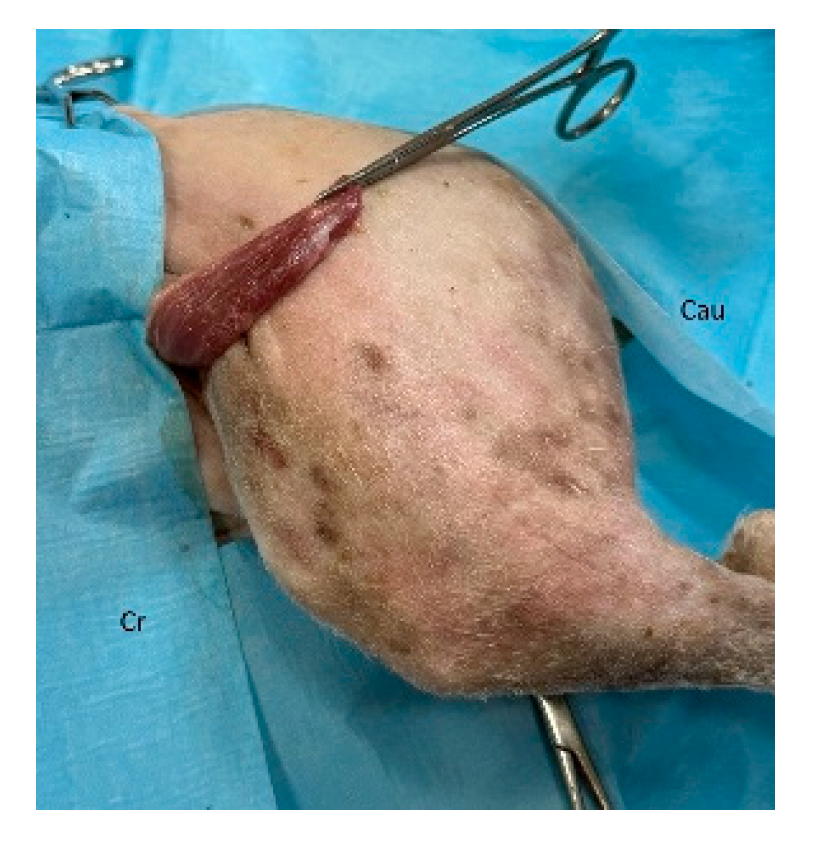

Figure 4.

The flap is elevated and transposed to the forelimb defect. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 4.

The flap is elevated and transposed to the forelimb defect. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 5.

The cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap is planned and marked similarly to the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. The cutaneous trunci flap is carefully elevated by separating it from the loose underlying subcutaneous tissues and transposed to the forelimb defect. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 5.

The cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap is planned and marked similarly to the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. The cutaneous trunci flap is carefully elevated by separating it from the loose underlying subcutaneous tissues and transposed to the forelimb defect. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 6.

Outline of the trapezius myocutaneous flap based on anatomic landmarks: 2 cm ventral to the dorsal midline (dorsal, caudal, and cranioventral borders), 2 cm caudal to the scapular spine, and a line between the acromion and transverse process of the third cervical vertebra. The arc of the flap’s rotation to the forelimb is shown.

Figure 6.

Outline of the trapezius myocutaneous flap based on anatomic landmarks: 2 cm ventral to the dorsal midline (dorsal, caudal, and cranioventral borders), 2 cm caudal to the scapular spine, and a line between the acromion and transverse process of the third cervical vertebra. The arc of the flap’s rotation to the forelimb is shown.

Figure 7.

A curved incision is performed starting from the distal third of the scapular spine, arching cranially and dorsally toward the midline and terminating 5cm caudal to the wing of the atlas. A second incision, curving ventrally, is made between these points raising a triangular section of the skin. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 7.

A curved incision is performed starting from the distal third of the scapular spine, arching cranially and dorsally toward the midline and terminating 5cm caudal to the wing of the atlas. A second incision, curving ventrally, is made between these points raising a triangular section of the skin. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 8.

The cervical part of the trapezius is dissected and its attachments are incised. The incised trapezius is dissected from the cleidocervicalis and omotransversarius muscles, preserving the prescapular branch of the superficial cervical vascular pedicle (black arrow) from which the trapezius muscle receives its vascular supply. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 8.

The cervical part of the trapezius is dissected and its attachments are incised. The incised trapezius is dissected from the cleidocervicalis and omotransversarius muscles, preserving the prescapular branch of the superficial cervical vascular pedicle (black arrow) from which the trapezius muscle receives its vascular supply. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 9.

The trapezius myocutaneous flap has been rotated to cover a defect involving the proximal third of the forelimb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 9.

The trapezius myocutaneous flap has been rotated to cover a defect involving the proximal third of the forelimb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 10.

Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap and its arc of rotation to the hindlimb.

Figure 10.

Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap and its arc of rotation to the hindlimb.

Figure 11.

A transverse skin incision is made 2–3 cm cranial to the ischial tuberosity, followed by two vertical incisions extending distally to the caudal stifle. Left hindlimb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 11.

A transverse skin incision is made 2–3 cm cranial to the ischial tuberosity, followed by two vertical incisions extending distally to the caudal stifle. Left hindlimb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 12.

The semitendinosus myocutaneous flap is detached from its origin on the ischial tuberosity and mobilized distally, preserving the distal vascular pedicle (black arrow). Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 12.

The semitendinosus myocutaneous flap is detached from its origin on the ischial tuberosity and mobilized distally, preserving the distal vascular pedicle (black arrow). Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 13.

The flap is rotated laterally or medially to cover the tibial defects. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 13.

The flap is rotated laterally or medially to cover the tibial defects. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 14.

Flexor carpi ulnaris muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 14.

Flexor carpi ulnaris muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 15.

A skin incision is made along the caudolateral surface of the antebrachium. The fascial connections of the humeral head of the muscle are dissected, and an incision is made at the junction of the proximal and middle third of the muscle. A vascular pedicle from the caudal interosseous artery enters the distal end of the humeral head near the accessory carpal bone (black arrow). Left front limb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 15.

A skin incision is made along the caudolateral surface of the antebrachium. The fascial connections of the humeral head of the muscle are dissected, and an incision is made at the junction of the proximal and middle third of the muscle. A vascular pedicle from the caudal interosseous artery enters the distal end of the humeral head near the accessory carpal bone (black arrow). Left front limb. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 16.

The muscle is rotated medially or laterally to cover the defect. Left front limb, lateral surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 16.

The muscle is rotated medially or laterally to cover the defect. Left front limb, lateral surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 17.

Caudal sartorius muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 17.

Caudal sartorius muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 18.

A skin incision is made along the medial aspect of the thigh. The caudal sartorius muscle is transected approximately 4 cm distal to its iliac origin. The saphenous artery and medial saphenous vein are ligated near their confluence with the femoral vessels. Care must be taken to preserve the saphenous vasculature as it runs along the medial aspect of the tibia and adjacent to the muscle’s caudal border (black arrow). The flap can extend to the distal tibia, the tarsocrural joint and the proximal metatarsal bones. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 18.

A skin incision is made along the medial aspect of the thigh. The caudal sartorius muscle is transected approximately 4 cm distal to its iliac origin. The saphenous artery and medial saphenous vein are ligated near their confluence with the femoral vessels. Care must be taken to preserve the saphenous vasculature as it runs along the medial aspect of the tibia and adjacent to the muscle’s caudal border (black arrow). The flap can extend to the distal tibia, the tarsocrural joint and the proximal metatarsal bones. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 19.

Cranial sartorius muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 19.

Cranial sartorius muscle flap and its arc of rotation.

Figure 20.

A skin incision is made along the medial aspect of the thigh. The muscle is exposed, isolated and transected distally at its insertion on the tibia. It is elevated to its vascular pedicle, which enters the proximal and middle third of the muscle caudally, and rotated to adjacent defects. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 20.

A skin incision is made along the medial aspect of the thigh. The muscle is exposed, isolated and transected distally at its insertion on the tibia. It is elevated to its vascular pedicle, which enters the proximal and middle third of the muscle caudally, and rotated to adjacent defects. Left hindlimb, medial surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 21.

For defects of the greater trochanteric region the flap is transposed, using either rotational transposition or inversion, depending on the desired arc of coverage. Left hindlimb, lateral surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Figure 21.

For defects of the greater trochanteric region the flap is transposed, using either rotational transposition or inversion, depending on the desired arc of coverage. Left hindlimb, lateral surface. Cr: cranial, Cau: caudal.

Table 1.

Flap type, Arc of Rotation, and Indications.

Table 1.

Flap type, Arc of Rotation, and Indications.

| Flap Type |

Transposition/Arc of Rotation |

Indications |

| Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous |

Wide arc; cranioventral rotation to thorax/forelimb |

Thoracic wall defects, large forelimb wounds |

| Cutaneous trunci myocutaneous |

Moderate arc; rotated to elbow/antebrachial region |

Forelimb defects up to elbow |

| Trapezius myocutaneous |

Rotated to cervical/thoracic regions |

Neck, upper thorax, proximal forelimb defects |

| Semitendinosus myocutaneous (limb reconstruction) |

Wide arc of rotation 150–180° medially, laterally or distally |

Distal hindlimb wounds, tibial/metatarsal defects, Achilles tendon rupture repair, Perineal hernia, fecal incontinence, rectal wall repair |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris muscle |

Distally rotated to carpus/metacarpus |

Antebrachial, carpal, and metacarpal soft tissue defects |

| Caudal sartorius muscle |

Distally rotated to tibia/metatarsus |

Distal tibial wounds, metatarsal defects, osteomyelitis |

| Cranial sartorius muscle |

Simple rotation or inversion over trochanter |

Trochanteric ulcers, abdominal wall reconstruction, femoral hernia |