Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ball Milling

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Disussion

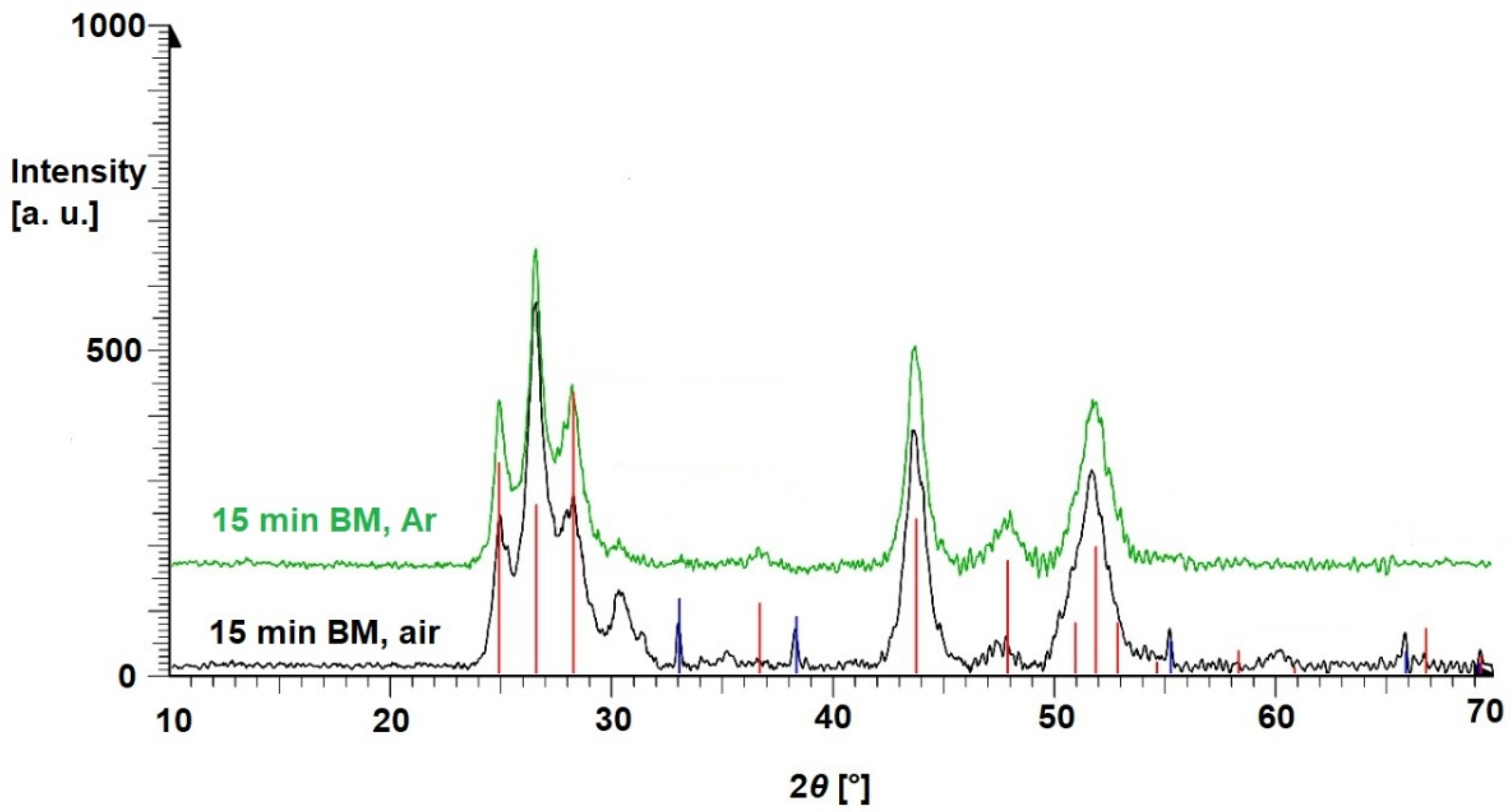

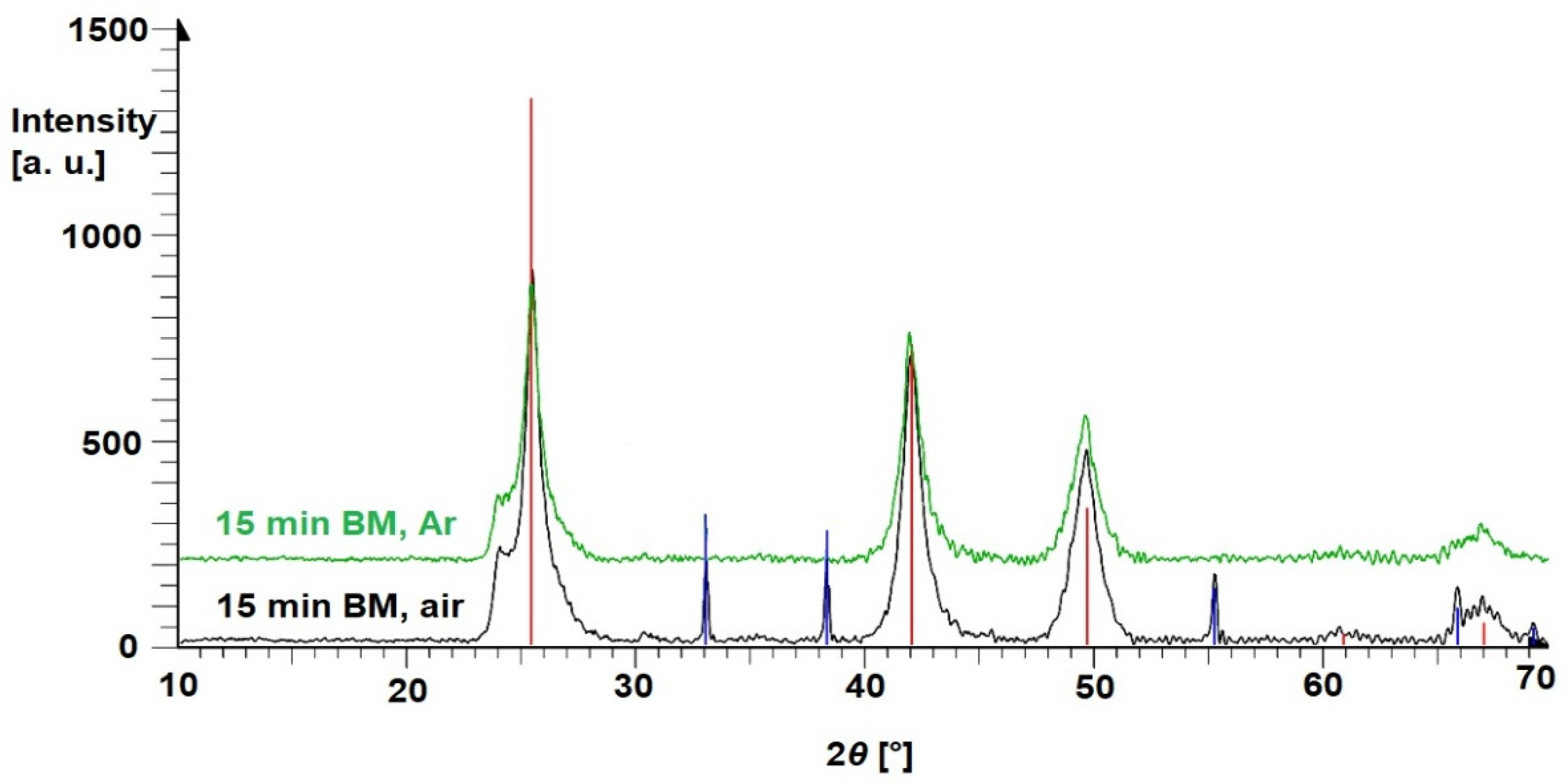

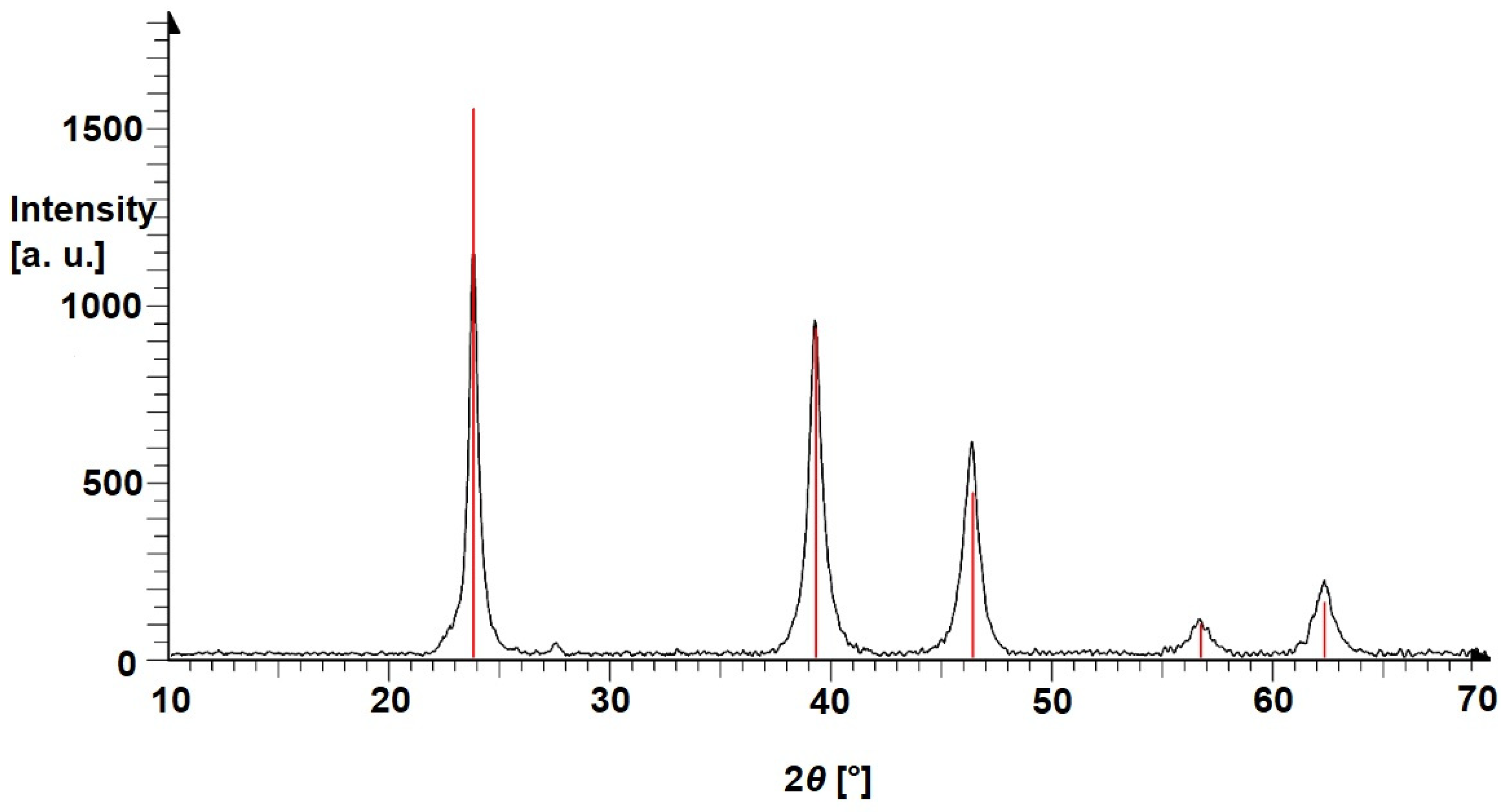

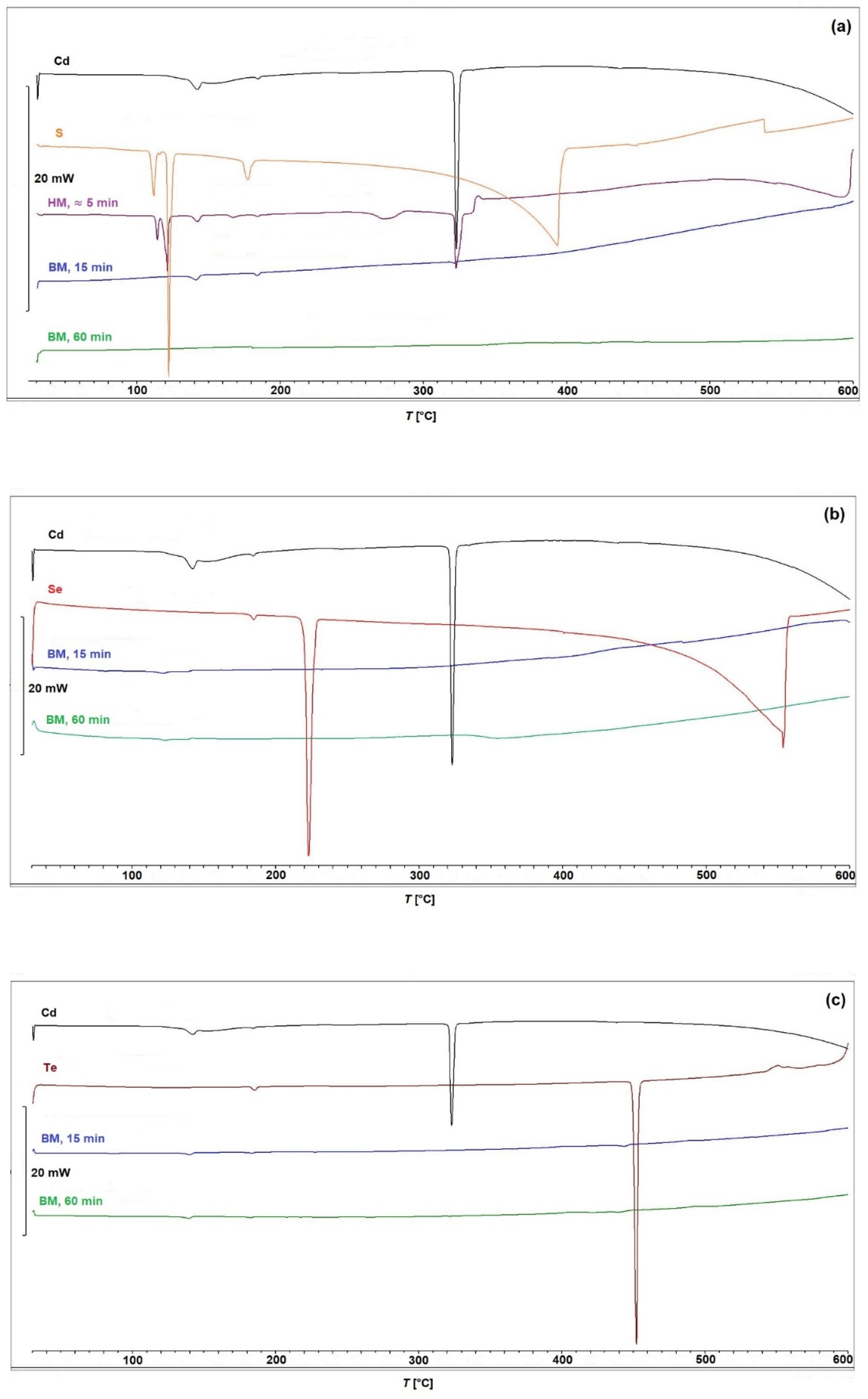

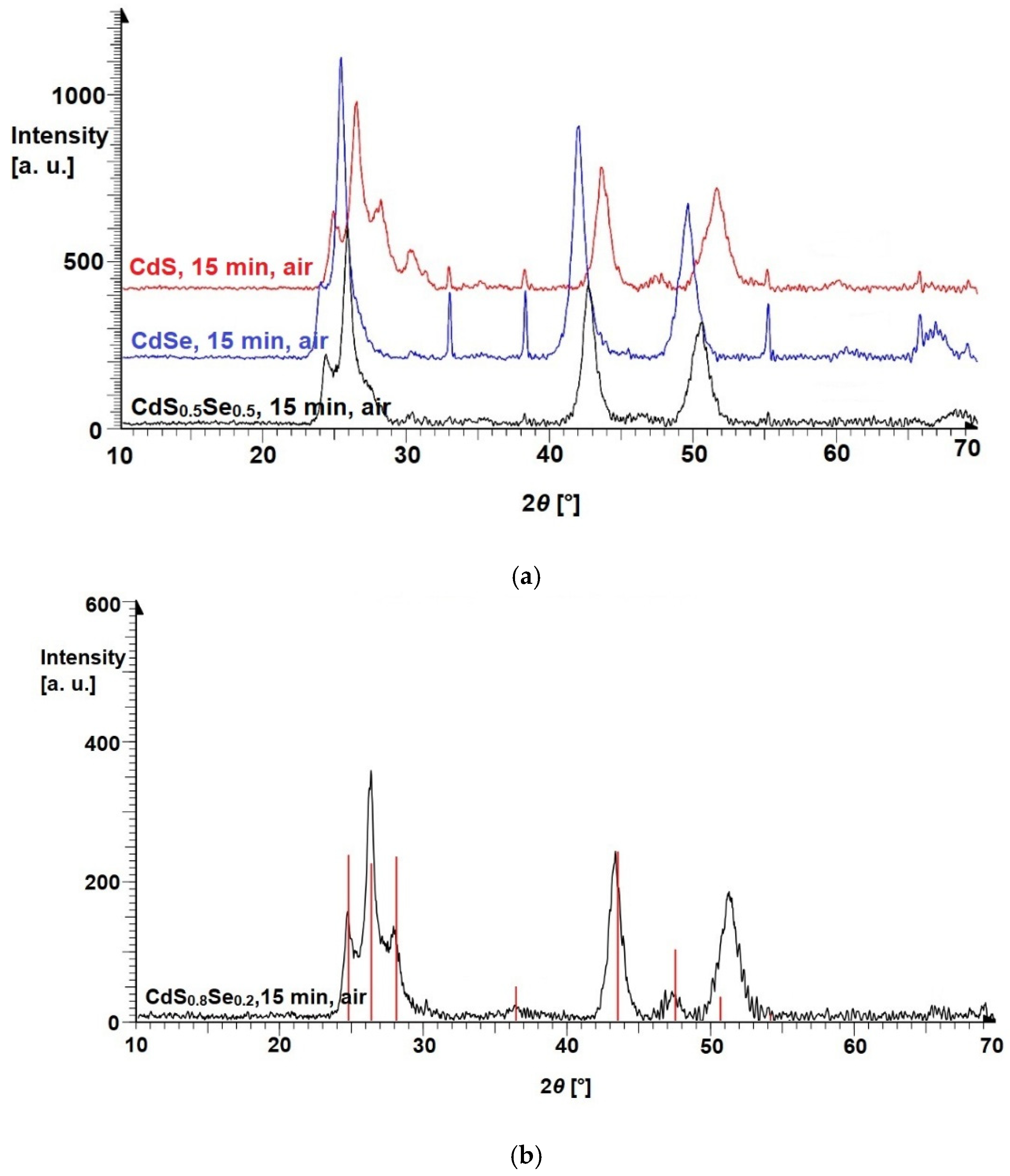

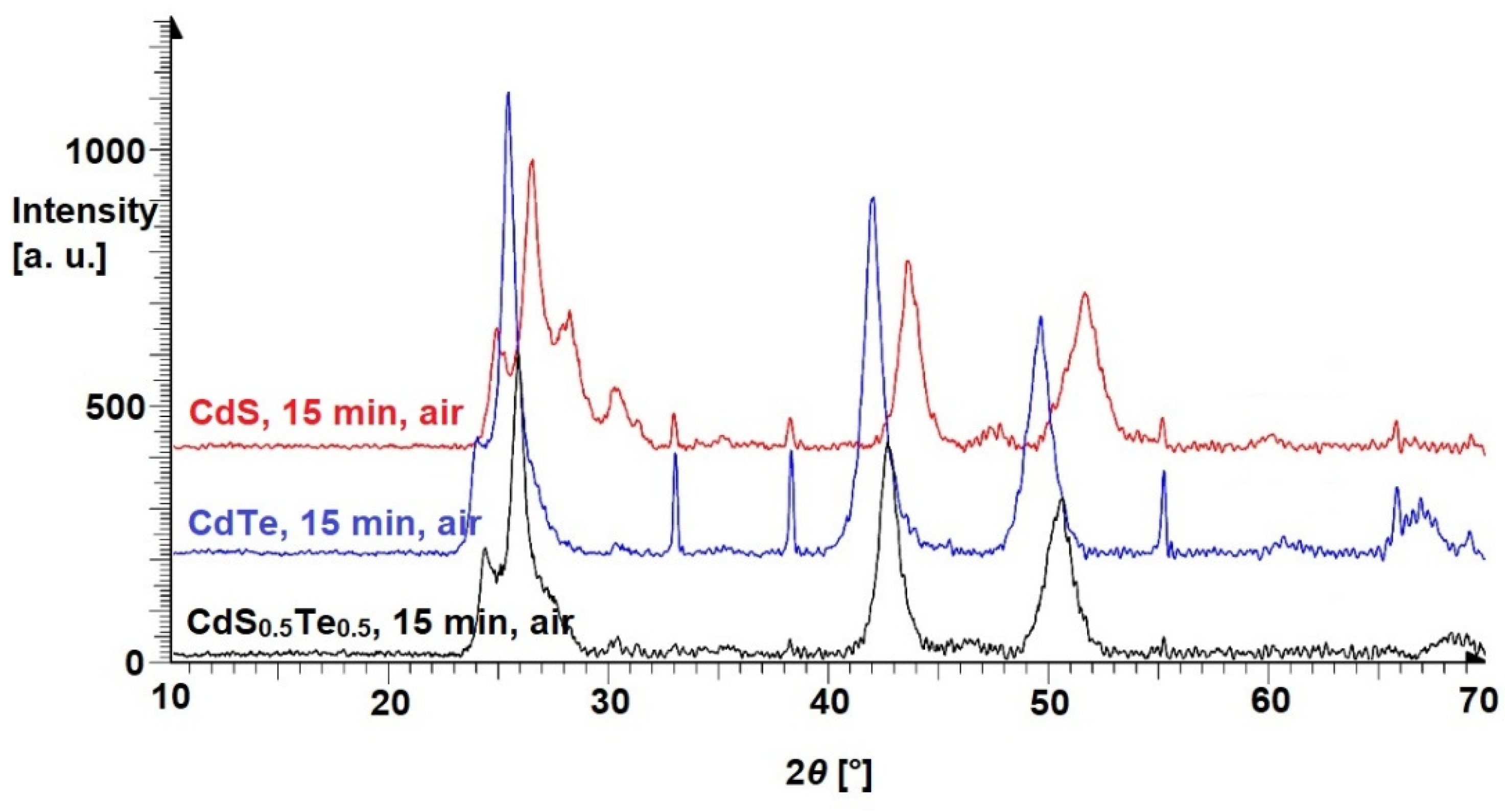

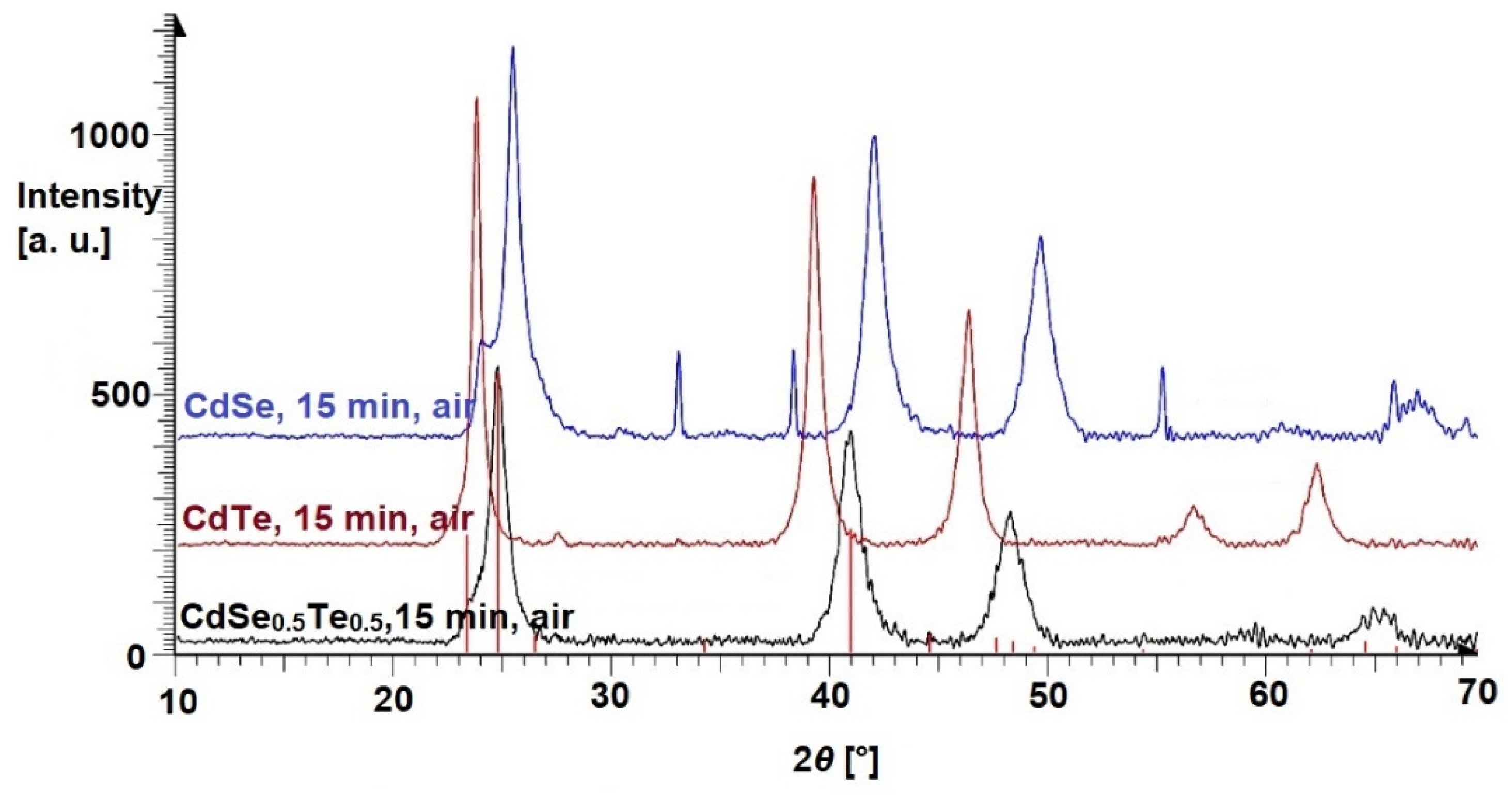

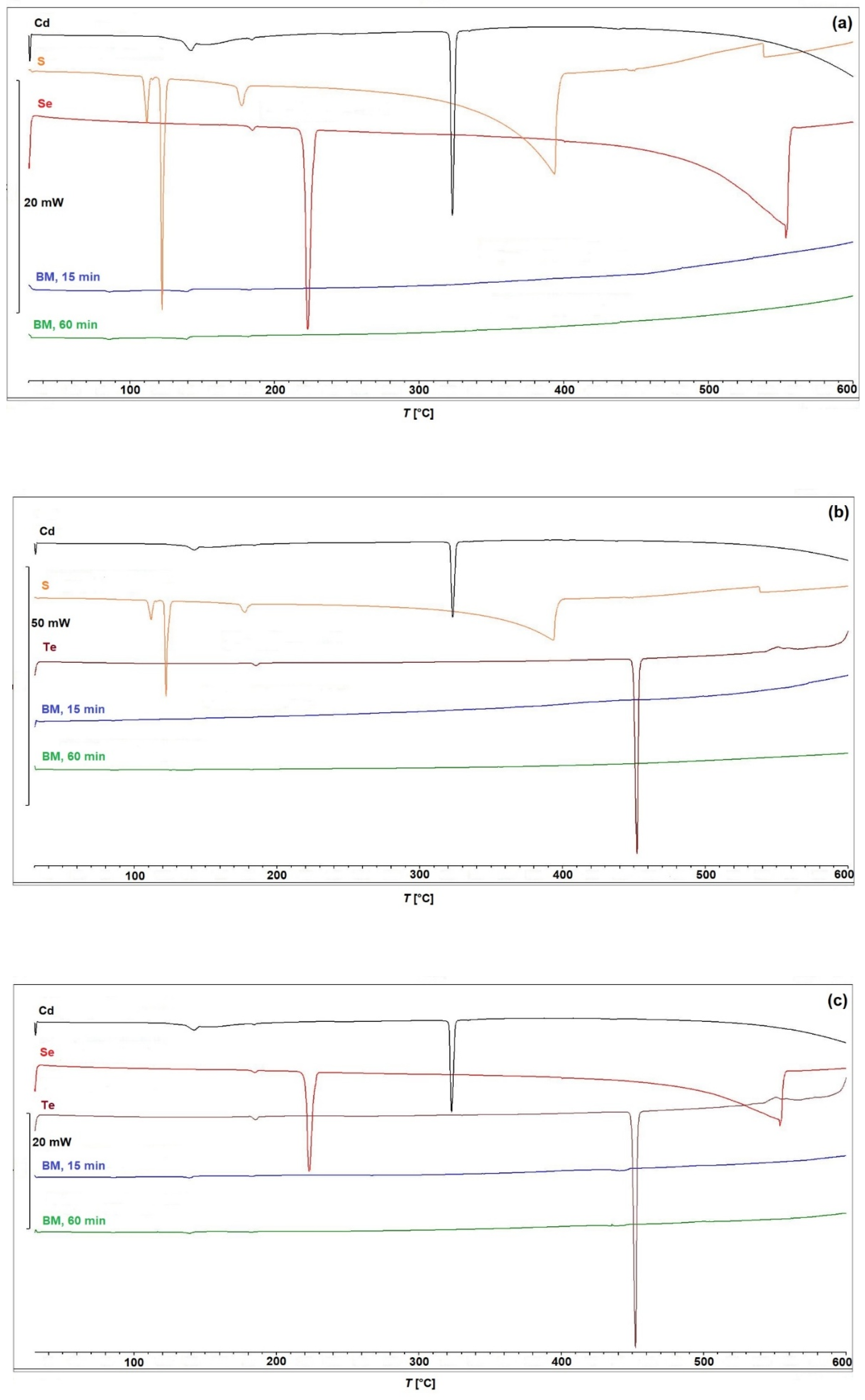

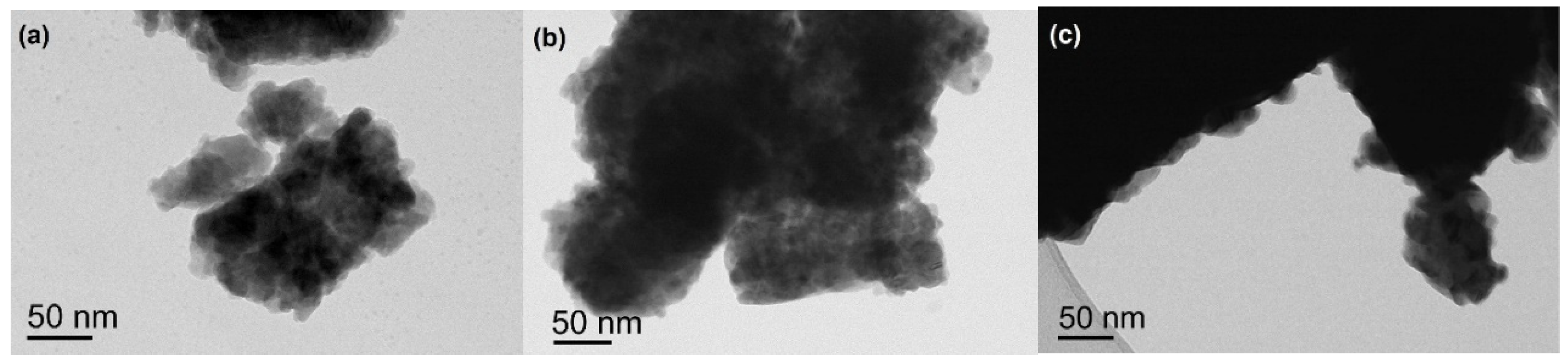

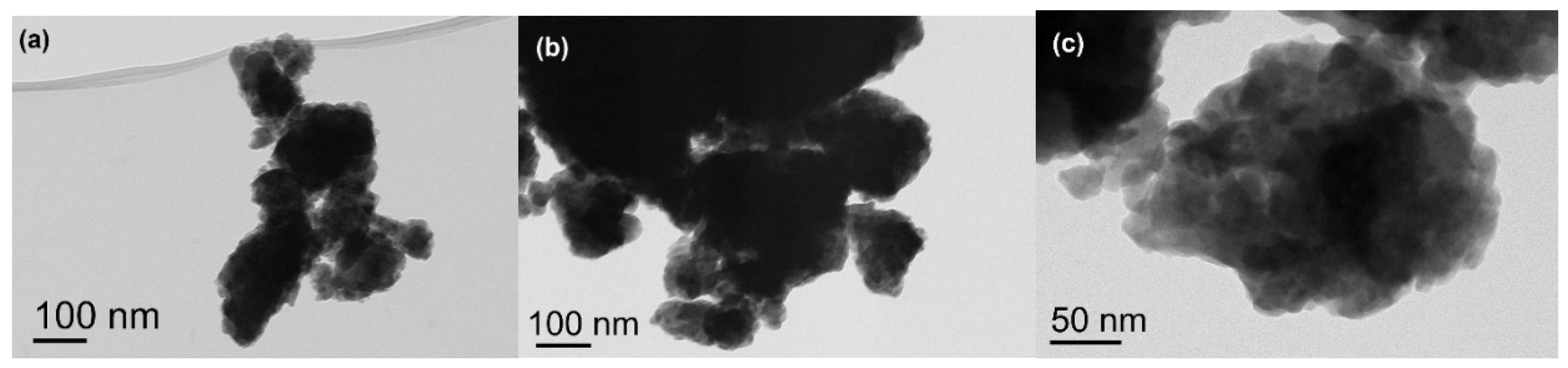

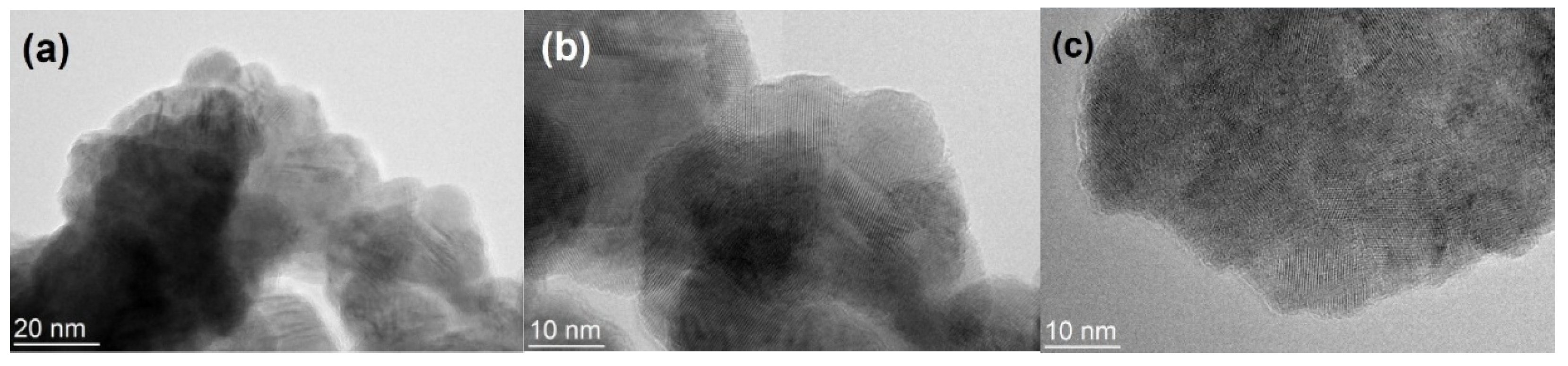

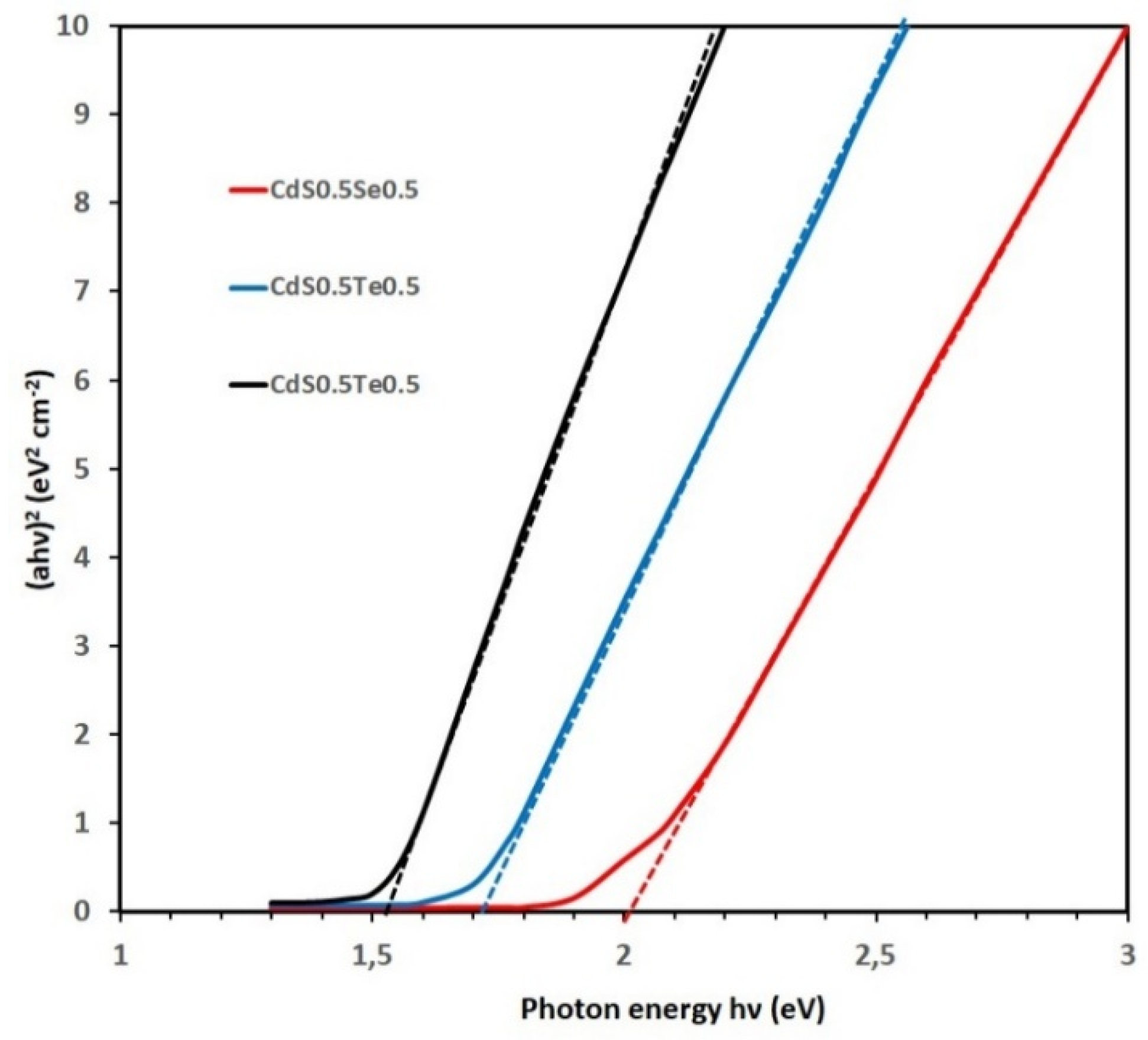

3.1. Binary Mixtures

3.2. Ternary Mixtures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| pXRD | Powder X-ray Diffraction |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| AAS | Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy |

References

- Maity, R.; Kundoo, S.; Chattopadhyay, K.K. Synthesis and Optical Characterization of CdS Nanowires by Chemical Route. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2006, 21, 644–647. [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.T; Hafeez, H.Y.; Mohammed, J.; Kafadi, A.D.G.; Ndikilar, C.E.; Suleiman, A.B. A review on the progress and prospect of CdS-based photocatalysts for hydrogen generation via photocatalytic water splitting. J. Alloy. Comp. Comm. 2024, 4, 100043. [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, N.H.S; Syed, J.A.S.; Azhar, R.; Adzis, N.S.; Halim, O.M.A.; Chang, Y.H.R.; Taylor, S.H.; Bailey, L.A.; Ab Rahim, M.H.; Ramli, M.Z.; Nawawi, W.I.; Ishak, M.A.M. Perspective on CdS-based S-scheme photocatalysts for efficient photocatalytic applications: Characterisation techniques and optimal semiconductor coupling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 165, 150929. [CrossRef]

- Mamiyev, Z.; Balayeva, N.O. Metal Sulfide Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation: A Review of Recent Advances. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1316. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Z.; Rong, H.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, H. Synthesis of CdSe and CdSe/ZnS Quantum Dots with Tunable Crystal Structure and Photoluminescent Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2969. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Ali, A.; Ul Haq, I.; Abdul Aziz, S.; Ali, Z.; Ahmad, I. The effect of potassium insertion on optoelectronic properties of cadmium chalcogenides, Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 122, 105466. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.A.; Oliva, A.I. A Double Energy Transition of Nanocrystalline CdxZn1-xS Films Deposited by Chemical Bath. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2015, 30, 785–792. [CrossRef]

- Aldakov, D.; Lefrançois, A.; Reiss, P. Ternary and quaternary metal chalcogenide nanocrystals: synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 3756-3776. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, F.; Al-Hartomy, O.; Wageh, S. Cadmium-Based Quantum Dots Alloyed Structures: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5877. [CrossRef]

- Moger, S.N.; Mahesha, M. G. Colour tunable co-evaporated CdSxSe1-x (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) ternary chalcogenide thin films for photodetector applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 120, 105288. [CrossRef]

- Diker, H.; Unluturk, S.S.; Ozcelik, S.; Varlikli, C. Improving the Stability of Ink-Jet Printed Red QLEDs By Optimizing The Device Fabrication Process. Nanofabrication 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Luan, C.; Chen, X.; Yu, K. Development of aqueous-phase CdSeS magic-size clusters at room temperature and quantum dots at elevated temperatures. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 10529–10535. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, H.; Gul, B.; Khan, M.S. Investigating the Optoelectronic and Thermoelectric Properties of CdTe Systems in Different Phases: A First-Principles Study. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 14742-14751. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, A.; Artegiani, E. CdTe-Based Thin Film Solar Cells: Past, Present and Future. Energies 2021, 14, 1684. [CrossRef]

- Bosio, A.; Rosa, G.; Romeo, N. Past, present and future of the thin film CdTe/CdS solar cells. Sol. Energy 2018, 175, 31-43. [CrossRef]

- Scarpulla, M.A.; McCandless, B.; Phillips, A.B.; Yan, Y.; Heben, M.J.; Wolden, C.; Xiong, G.; Metzger, W.K.; Mao, D.; Krasikov, D.; Sankin, I.; Grover, S.; Munshi, A.; Sampath, W.; Sites, J.R.; Bothwell, A.; Albin, D.; Reese, M.O.; Romeo, A.; Nardone, M.; Klie, R.; J. Walls, J.M.; Fiducia, T.; Abbas, A.; Hayes, S.M. CdTe-based thin film photovoltaics: Recent advances, current challenges and future prospects. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 255, 112289. [CrossRef]

- Sivasankar, S.M.; Amorim, C.d.O.; Cunha, A.F.d. Progress in Thin-Film Photovoltaics: A Review of Key Strategies to Enhance the Efficiency of CIGS, CdTe, and CZTSSe Solar Cells. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 143. [CrossRef]

- Jamaatisomarin, F.; Chen, R.; Hosseini-Zavareh, S.; Lei, S. Laser Scribing of Photovoltaic Solar Thin Films: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 94. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.H.; Cho, D.Y.; Oliynyk, A.O.; Silverman, J.R. Green Chemistry Applied to Transition Metal Chalcogenides through Synthesis, Design of Experiments, Life Cycle Assessment, and Machine Learning. Green Chemistry - New Perspectives. IntechOpen; 2022. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.104432.

- Ghasempour, A.; Dehghan, H.; Ataee, M.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Z.; Sedighi, M.; Guo, X.; Shahbazi, M.-A. Cadmium Sulfide Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, and Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 3857. [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.A.; Norton, K.; McNaughter, P.D.; Whitehead, G.; Vitorica-Yrezabal, I.; Alam, F.; Laws, K.; Lewis, D.J. Investigating the Effect of Steric Hindrance within CdS Single-Source Precursors on the Material Properties of AACVD and Spin-Coat-Deposited CdS Thin Films. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 8206–8216. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, G.; Tyagi, A.; Shah, A.Y. A comprehensive review on single source molecular precursors for nanometric group IV metal chalcogenides: Technologically important class of compound semiconductors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 504, 215665. [CrossRef]

- Dojer, B.; Pevec, A.; Breznik, K.; Jagličić, Z.; Gyergyek, S.; Kristl, M. Structural and thermal properties of new copper and nickel single-source precursors. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1194, 171-177. [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Ban, I.; Danč, A.; Danč, V.; Drofenik, M. A sonochemical method for the preparation of cadmium sulfide and cadmium selenide nanoparticles in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010, 17, 916-922. [CrossRef]

- Ban, I.; Kristl, M.; Danč, V.; Danč, A.; Drofenik, M. Preparation of cadmium telluride nanoparticles from aqueous solutions by sonochemical method. Mater. Lett. 2012, 67, 56-59. [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, B.; Paul, B.; Chang, C.-H. The synthesis of cadmium sulfide nanoplatelets using a novel continuous flow sonochemical reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 26, 452-460. [CrossRef]

- Denac, B.; Kristl, M.; Gyergyek, S.; Drofenik, M. Preparation and characterization of ternary cadmium chalcogenides. Chalcogenide Lett. 2013, 10, 87-98.

- Shalabayev, Z.; Baláž, M.; Khan, N.; Nurlan, Y.; Augustyniak, A.; Daneu, N.; Tatykayev, B.; Dutková, E.; Burashev, G.; Casas-Luna, M.; et al. Sustainable Synthesis of Cadmium Sulfide, with Applicability in Photocatalysis, Hydrogen Production, and as an Antibacterial Agent, Using Two Mechanochemical Protocols. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1250. [CrossRef]

- Gancheva, M.; Iordanova, R.; Ivanov, P.; Yordanova, A. Effect of Ball Milling Speeds on the Phase Formation and Optical Properties of α-ZnMoO4 and ß-ZnMoO4 Nanoparticles. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 118. [CrossRef]

- Pagola, S. Outstanding Advantages, Current Drawbacks, and Significant Recent Developments in Mechanochemistry: A Perspective View. Crystals 2023, 13, 124. [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, N.; Volle, J.-N.; Porcheddu, A.; Virieux, D.; Garcia, F.; Colacino, E. Green metrics in mechanochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6680-6714. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N. Mechanochemistry: A Resurgent Force in Chemical Synthesis. Synlett 2024, 35, 2331-2345. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V., Stolar, T., Karadeniz, B.; Brekalo, I.; Užarević, K. Advancing mechanochemical synthesis by combining milling with different energy sources. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Dubadi, R.; Huang, S.D.; Jaroniec, M. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Nanoparticles for Potential Antimicrobial Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 1460. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.L.; Hömmerich, U.; Temple, D.; Wu, N.Q.; Zheng, J.G.; Loutts, G. Synthesis and optical characterization of CdTe nanocrystals prepared by ball milling process. Scr. Mater. 2003, 48,1469-1474. [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.E.M. Solid State Synthesis and Characterization of NiTe Nanocrystals. J. Nano Res. 2014, 29, 35-39. [CrossRef]

- Baláž, M.; Džunda, R.; Bureš, R.; Sopčák, T.; Csanádi, T. Mechanically induced self-propagating reactions (MSRs) to instantly prepare binary metal chalcogenides: assessing the influence of particle size, bulk modulus, reagents melting temperature difference and thermodynamic constants on the ignition time. RSC Mechanochem. 2024, 1, 94-105. [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Ban, I.; Gyergyek, S. Preparation of Nanosized Copper and Cadmium Chalcogenides by Mechanochemical Synthesis. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2013, 28, 1009–1013. [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Gyergyek, S.; Srt, N.; Ban, I. Mechanochemical Route for the Preparation of Nanosized Aluminum and Gallium Sulfide and Selenide. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1608–1612. [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Gyergyek, S.; Škapin, S.D.; Kristl, J. Solvent-Free Mechanochemical Synthesis and Characterization of Nickel Tellurides with Various Stoichiometries: NiTe, NiTe2 and Ni2Te3. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1959. [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Pascual-Martı́, M.C.; Aragó, E.; Chisvert, A.; March, J.G. Determination of selenium, zinc and cadmium in antidandruff shampoos by atomic spectrometry after microwave assisted sample digestion. Talanta 2000, 51, 1171-1177. [CrossRef]

- Souaya, E.R.; Elkholy, S.A.; Abd El-Rahman, A.M.M.; El-Shafie, M.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Abo-Shanab, Z.L. Partial substitution of asphalt pavement with modified sulfur. Egypt. J. Pet. 2015, 24, 483-491. [CrossRef]

- Triboulet, R. Fundamentals of the CdTe synthesis. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 371, 67-71. [CrossRef]

- Ban, I.; Markuš, S.; Gyergyek, S.; Drofenik, M.; Korenak, J.; Helix-Nielsen, C.; Petrinić, I. Synthesis of Poly-Sodium-Acrylate (PSA)-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Use in Forward Osmosis Draw Solutions. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1238. [CrossRef]

- Larichev, Y.V. Application of DLS for metal nanoparticle size determination in supported catalysts. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 2059–2066. [CrossRef]

- Praus, P.; Kozák, O.; Kočí, K.; Panáček, A.; Dvorský, R. CdS nanoparticles deposited on montmorillonite: Preparation, characterization and application for photoreduction of carbon dioxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 360, Issue 2, 574-579. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T.; Verma, L.; Khare, A. Variations in photovoltaic parameters of CdTe/CdS thin film solar cells by changing the substrate for the deposition of CdS window layer. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 867. [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M., Wang, X., Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Pan A. Controllable Vapor Growth of Large-Area Aligned CdSxSe1−x Nanowires for Visible Range Integratable Photodetectors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018, 10, 58. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, J.; Gupta, H.; Purohit, L.P. Ternary alloyed CdS1−xSex quantum dots on TiO2/ZnS electrodes for quantum dots-sensitized solar cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 880,160480. [CrossRef]

- Mezrag, F.; Bouarissa, N.; El-Houda Fares, N. The band gap bowing of CdSxTe1−x alloys beyond the virtual crystal approximation. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2020, 9, 1056–1059. [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.W. A review of the optical band gap of thin film CdSxTe1−x. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2006, 90, 1169-1175. [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.; Zoppi, G.; Bowen, L.; Shalvey, T.P.; Mariotti, S.; Durose, K.; Major, J.D. Incorporation of CdSe layers into CdTe thin film solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 180,196-204. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Ma, Z.; Li, L.; Tian, T.; Yan, Y.; Su, J.; Deng, J.; Xia, C. Aqueous synthesis of alloyed CdSexTe1-x colloidal quantum dots and their In-situ assembly within mesoporous TiO2 for solar cells. Sol. Energy 2020, 196, 513-520. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wei, S.-H. First-principles study of the band gap tuning and doping control in CdSexTe1−x alloy for high efficiency solar cell. Chinese Phys. B 2019, 28, 086106. [CrossRef]

- Hoa, N.M., Thi, L.A., Hung, L.X., Toan, L.D. Tunable excitonic dynamics and photoluminescence modulation in graded CdSe/CdSeS quantum dots for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 1539. [CrossRef]

- Kashuba, A.I.; Andriyevsky, B. Growth and crystal structure of CdTe1−xSex (x ≥ 0.75) thin films prepared by the method of high-frequency magnetron sputtering. Low Temp. Phys. 2024, 50, 29–33. [CrossRef]

| sample | CdS | CdSe | CdTe | CdS0.8Se0.2 | CdS0.5Se0.5 | CdS0.5Te0.5 | CdSe0.5Te0.5 |

| d [nm] | 11.1 | 11.2 | 16.9 | 13.7 | 11.6 | 10.4 | 10.3 |

| sample | CdS | CdSe | CdTe | CdS0.8Se0.2 | CdS0.5Se0.5 | CdS0.5Te0.5 | CdSe0.5Te0.5 |

| d(H) [nm] | 325.8 | 202.7 | 124.4 | 271.0 | 207.7 | 347.1 | 126.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).