The present study examines volunteering within formal organizations. Distinctions in types of volunteering arise according to the domains in which voluntary activities are undertaken. The following types of volunteering have been analysed:

Beyond the typologies of volunteering, this study also examines its nature, distinguishing between transformative and welfare-oriented forms, and explores whether these two approaches differ in their perspectives on the state’s role within the third sector. Transformative volunteering aims to address social, environmental, or other causes by fostering sustainable, long-term change through altering the structural conditions that generate problems. In contrast, welfare-oriented volunteering focuses on mitigating the immediate consequences of social issues without necessarily challenging their root causes or advocating for policy reforms. While transformative volunteering is closely connected to political demands and the expectation of state involvement in problem-solving, the state itself adopts varying approaches to social assistance, which are shaped by different welfare state models. Thus, four models of the welfare state can be identified:

Considering the variations among welfare state models and their differing interpretations of responsibility for social assistance, we examine whether volunteers’ perceptions of the state’s role in welfare provision vary according to the nature of their volunteering. Specifically, it explores whether engagement in transformative, as opposed to welfare-oriented, volunteering aligns with particular conceptions of the welfare state and social assistance. The relationship between the state, the market, and the third sector is inherently political, shaping, enabling, or constraining the expansion and development of third-sector organizations. One of the central aims of this study is to investigate the ideology of volunteering, offering both a descriptive account of its ideological dimensions and a multivariate analysis to illuminate the links between forms of volunteering and political orientations.

4.2. Results

All variables, with the exception of

Type, were included in the analysis. The variable

Type was subsequently projected onto the plot to explore potential associations with the other variables. Factor extraction was conducted using the

principal components method, and the resulting factors were subjected to

Varimax rotation. The first two factors have been selected.

Table 4 contains the variance explained by each factor.

Both factors together explain a

of the variability. The factor matrix is shown in

table 5.

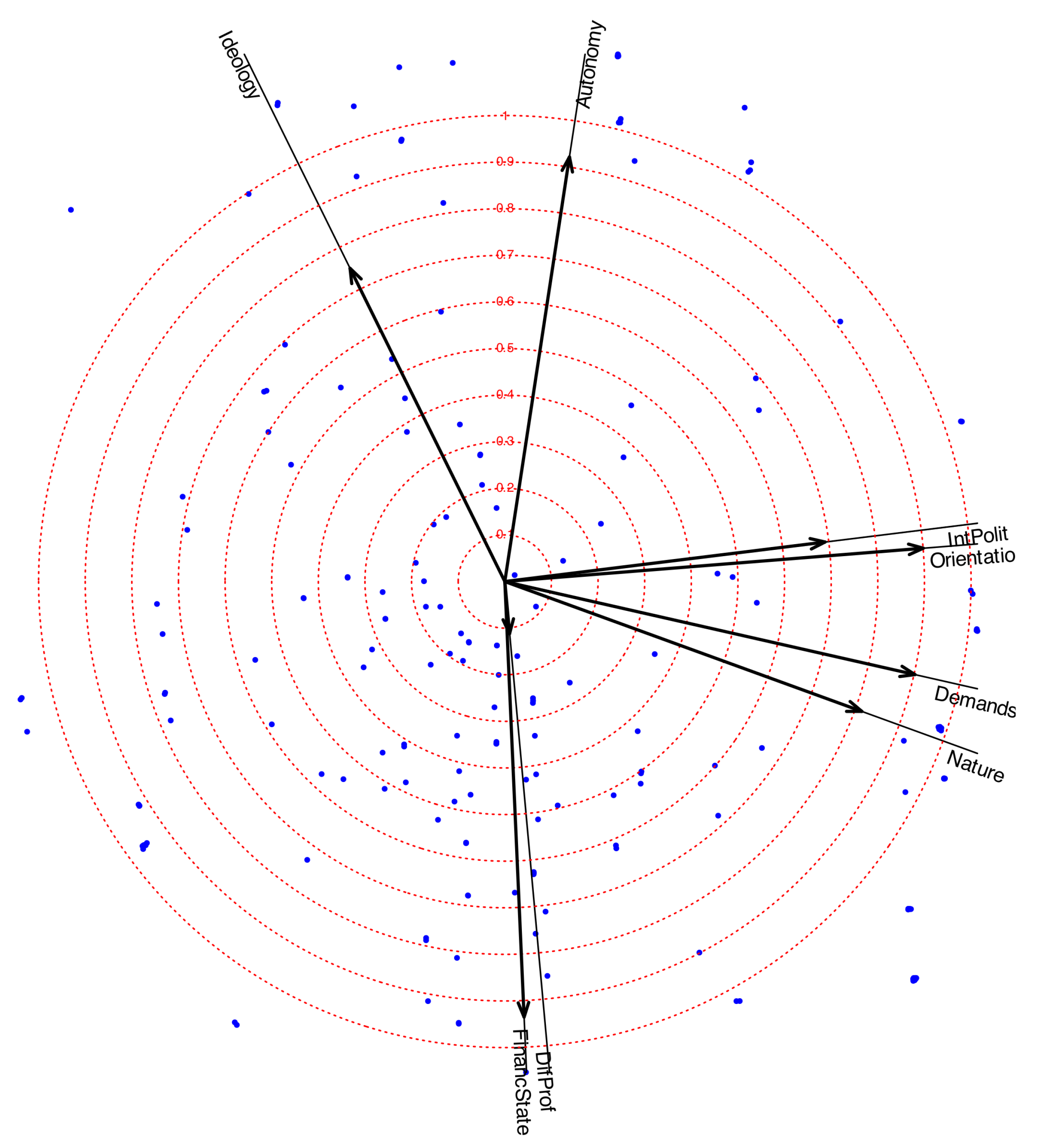

The first factor loaded positively on Interest in Politics, Organizational Orientation, Organizational Nature, and Political Demands, indicating that these variables are strongly interrelated. The second factor showed positive loadings for Ideology and Autonomy, and a negative loading for State Support of the Organization. This pattern suggests that Ideology and Autonomy are positively associated with each other, and both are negatively associated with State Support.

All communalities were relatively high, except for Different Profiles, which exhibited little association with the first two factors.

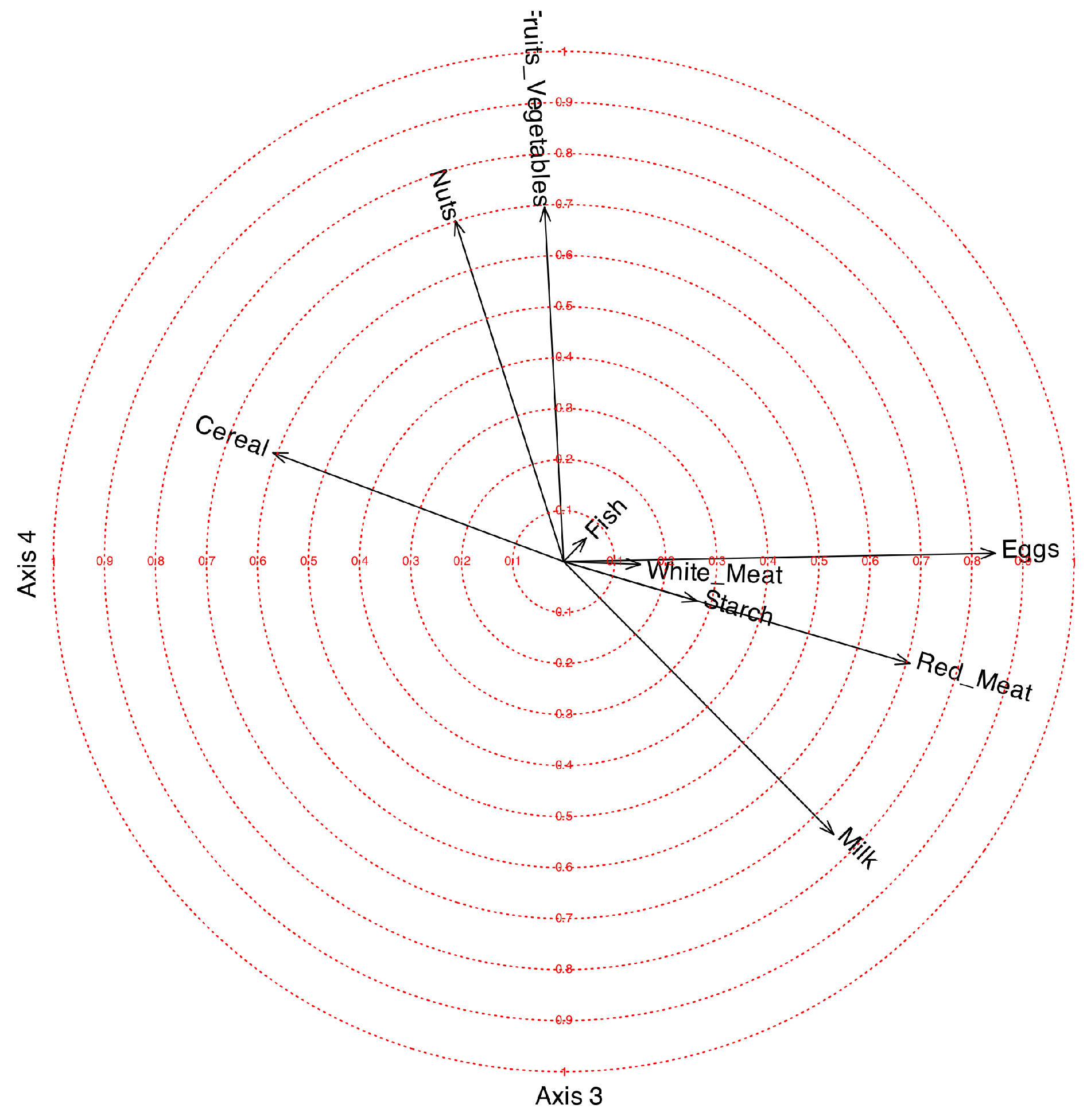

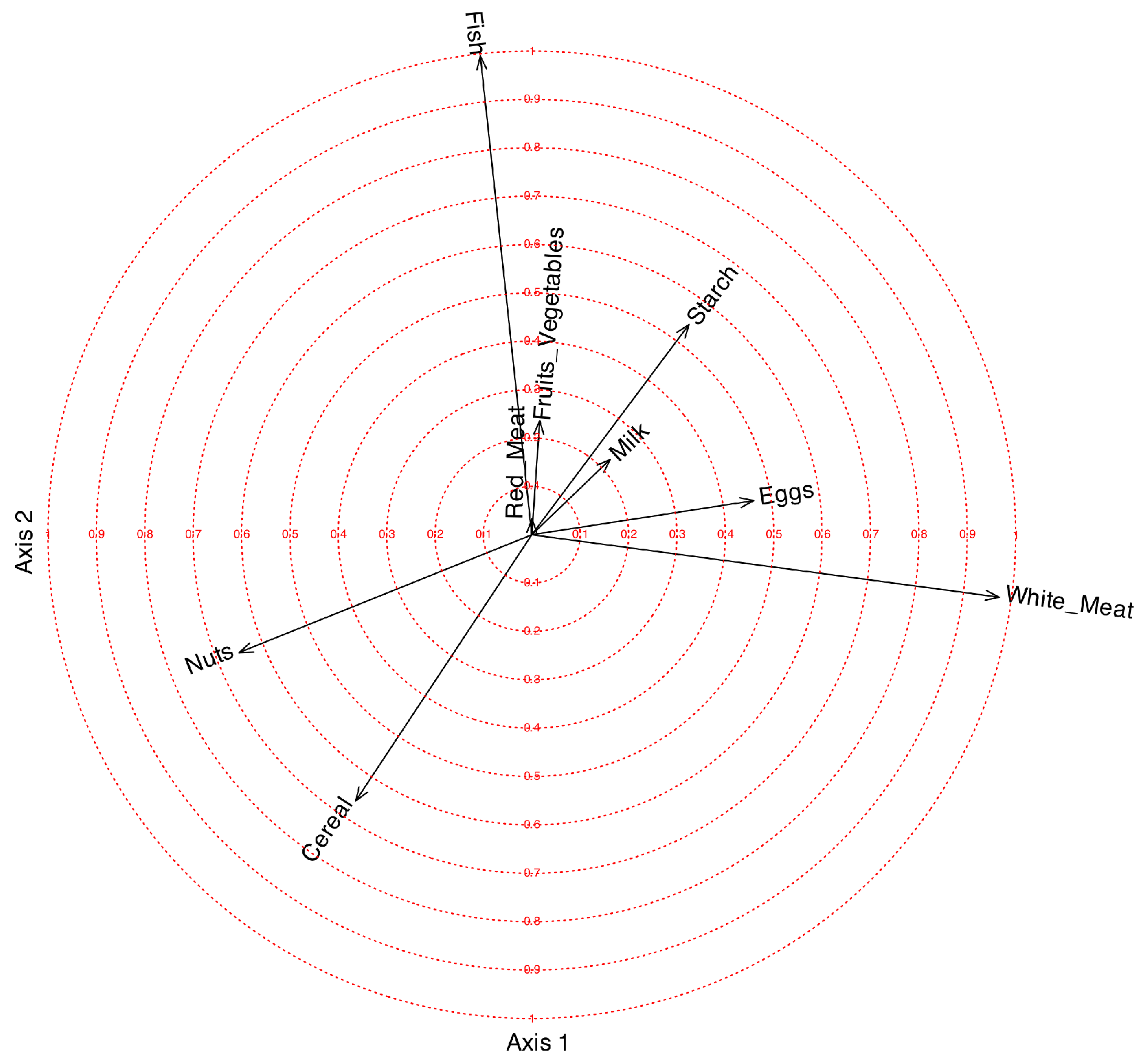

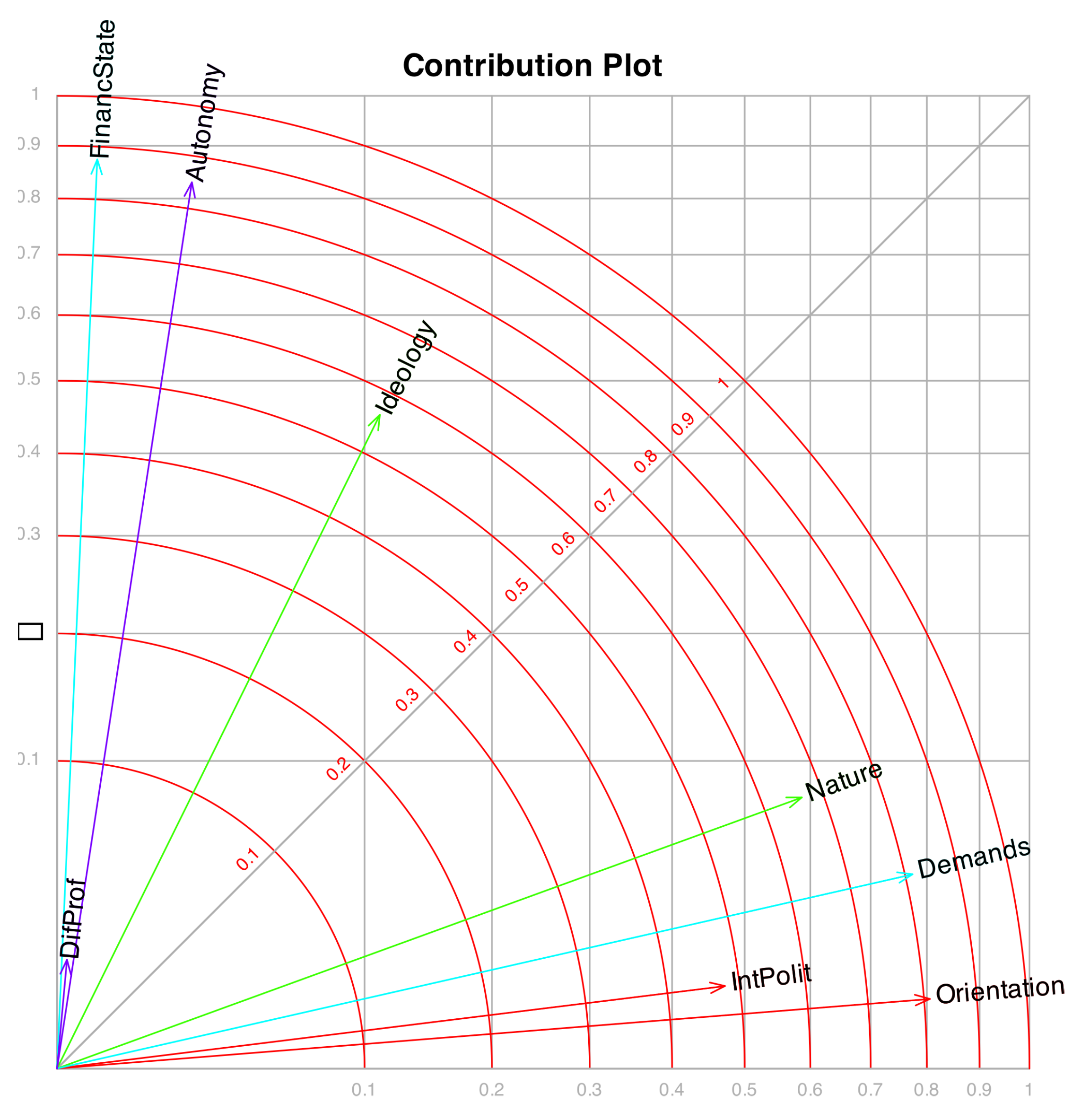

The factor biplot with correlation circles is presented in

Figure 7. As noted earlier,

Interest in Politics,

Organizational Orientation,

Organizational Nature, and

Political Demands are strongly and positively correlated. This cluster of variables shows little association with

Ideology,

Autonomy, or

State Support of the Organization. Thus, the choice of an organization with political demands or a transformative nature appears to be more closely linked to political interest than to ideological orientation.

On the other hand, Ideology and Autonomy are positively associated, while both are negatively related to State Support. This indicates that individuals on the left of the political spectrum tend to believe that organizations should be both autonomous and supported by the state, whereas those on the right favor autonomy but oppose state financing.

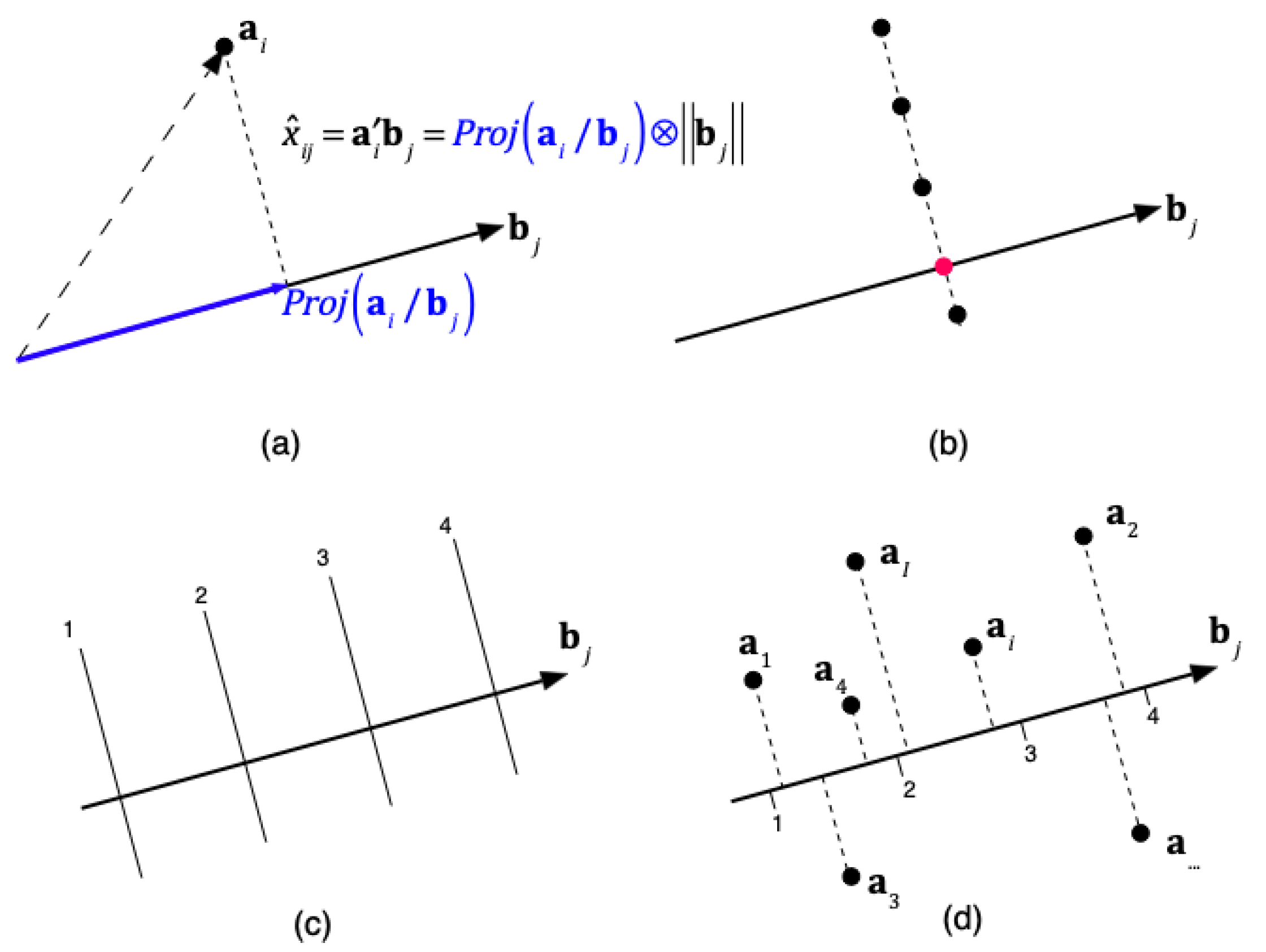

In the biplot, each point represents an individual. By projecting an individual onto the direction of a variable, one could, in principle, estimate the probabilities for each category. However, this is complex, as it would require separate probability scales along the same direction for each category. Our goal is not to predict exact probabilities, but to predict ordinal categories. For this purpose, it is sufficient to identify the points that separate the different category values.

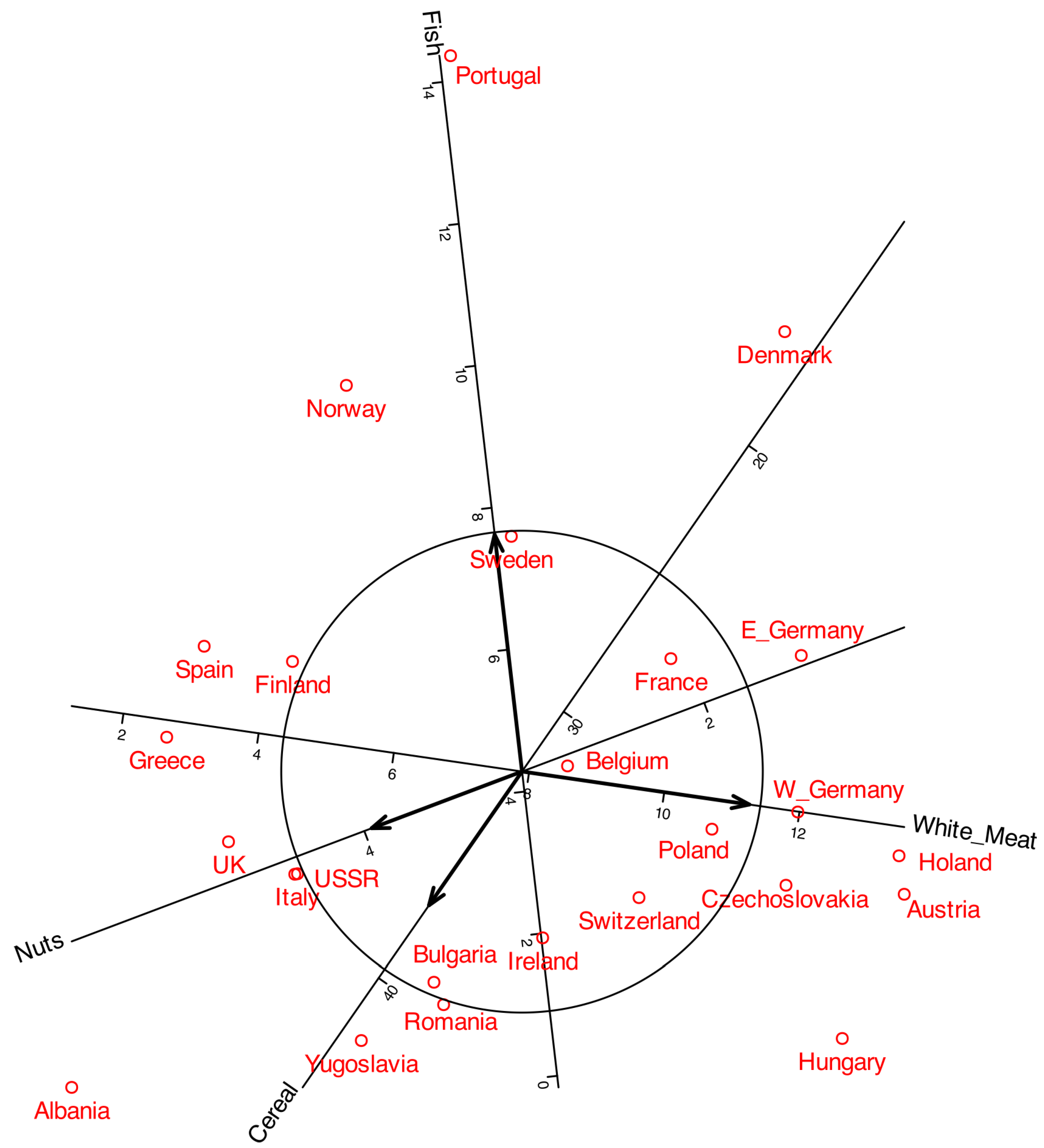

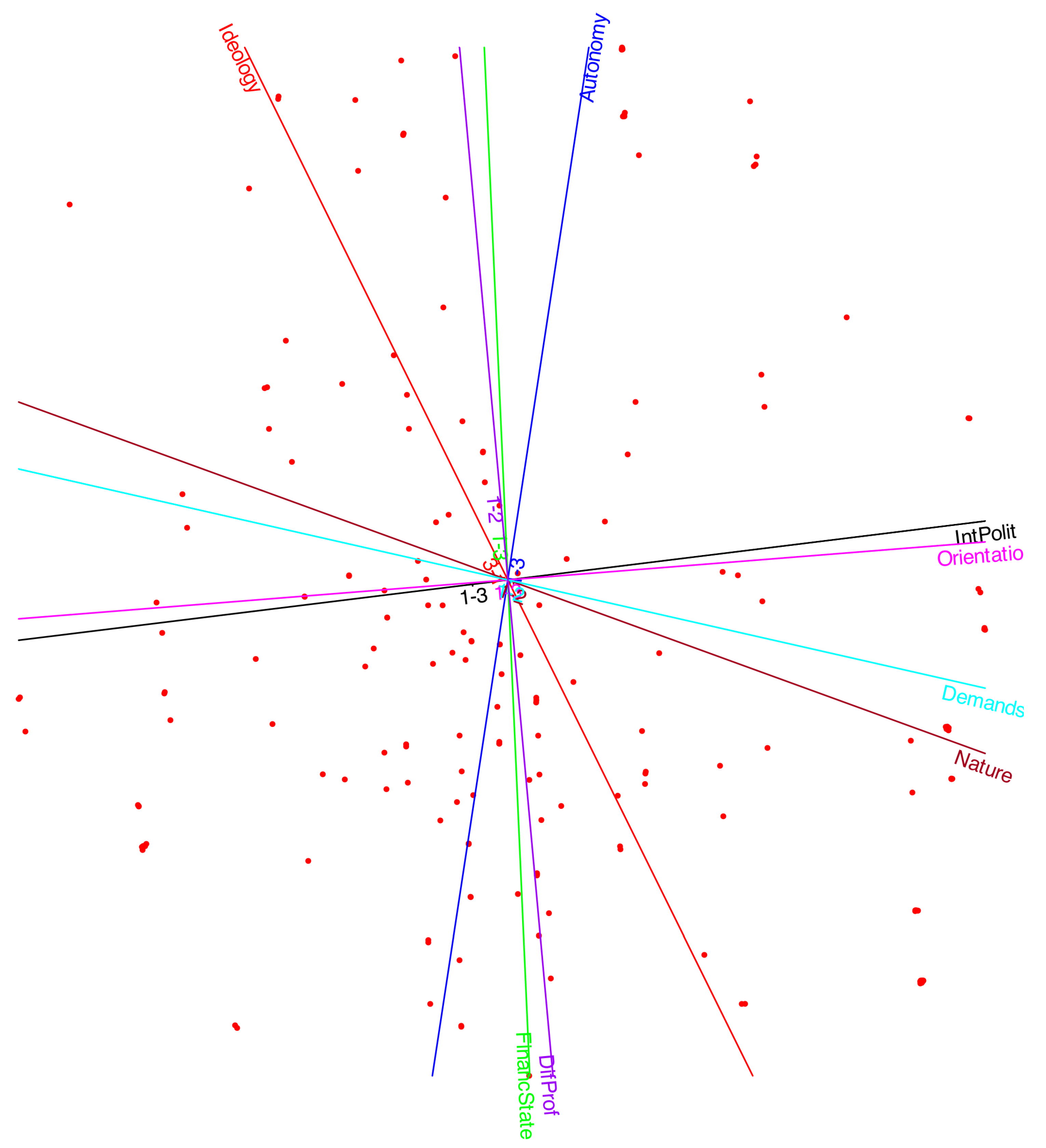

Together with the correlation biplot we can define a prediction biplot showing the the points that separate each prediction region as in

Figure 6. The prediction biplot is shown in

Figure 8.

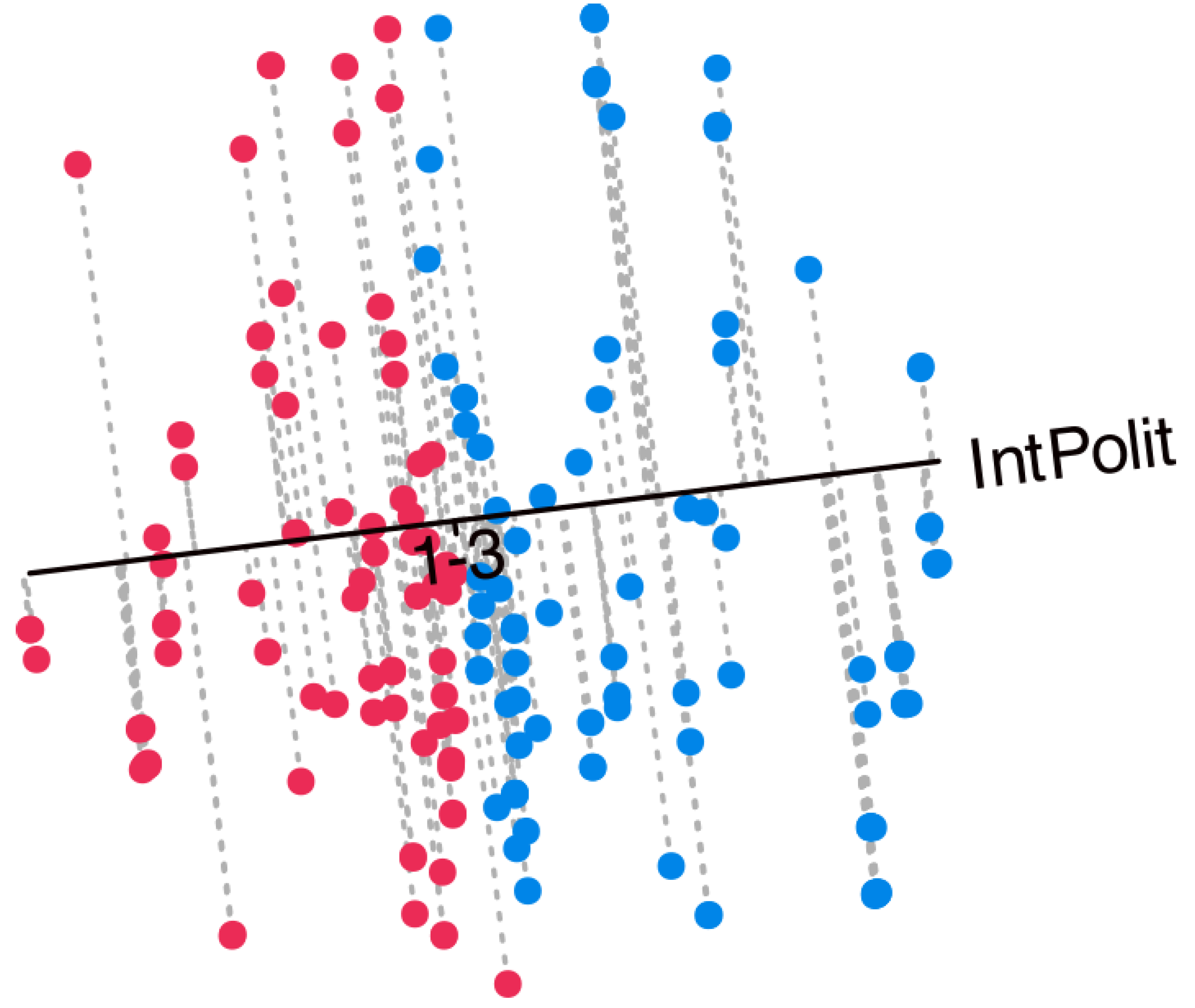

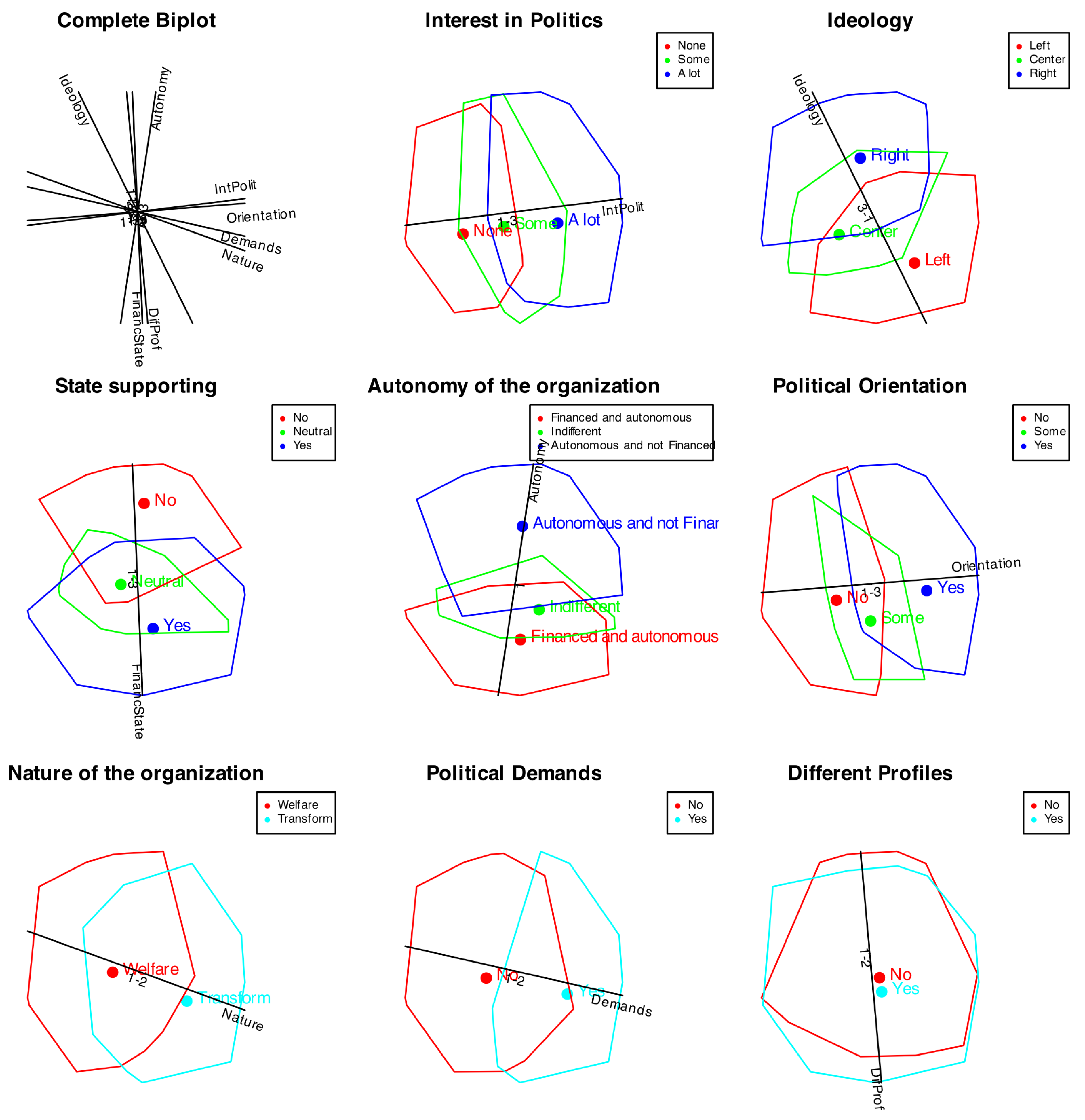

As previously discussed, the projection of individual points onto the variable axes allows for the prediction of the original categories by identifying the prediction region in which the projection falls.

Figure 9 presents the projections onto the variable *Interest in Politics*, serving as an example of how to interpret the biplot. Along the axis, cut-off points separating the prediction regions are indicated. For this variable, which comprises three categories (1 = None, 2 = Some, 3 = A lot), two separation points would be expected: one between categories 1 and 2 ("1-2") and another between categories 2 and 3 ("2-3"). However, only a single point labeled "1-3" is observed. This indicates that the separation occurs exclusively between categories 1 and 3, with the intermediate category (2) remaining unrepresented and, therefore, never predicted. A similar pattern emerges for all variables with three categories, whereby the intermediate level is consistently absent from the predictions. Furthermore, the separation points across variables are located near the center of the plot and tend to overlap, leading to a mixed configuration.

Figure 9 also displays the individuals together with their projections onto the selected variable. Points in red correspond to predictions of category 1 (None), whereas points in blue correspond to predictions of category 3 (A lot). The intermediate category 2 (Some) is not represented and is therefore never predicted. When considering all variables jointly, the resulting biplot provides a comprehensive view that facilitates the interpretation of the main structural features of the data.

Along with the correlations, we can also display the contributions or qualities of representation, which indicate how much of the variance of each observed variable is explained by the factors. These contributions are usually computed as squared correlations, and they can also be understood geometrically as the squared cosines of the angles between the original variables and the latent factors. In addition, they may be interpreted as measures of the discriminant power of each variable. The sum of the contributions across two factors corresponds to the contribution of the plane defined by those factors.

Although the information may be redundant, given the previous representations, we can include it to compare with other techniques as, for example, Multiple Correspondence Analysis.

Figure 10 displays the contributions associated with the first two factors, where each variable is represented by a vector. The plot is scaled so that the projection of a vector onto an axis corresponds to its contribution to the respective factor, while the concentric circles indicate the contribution of the plane formed by the two factors.

Beyond correlations and contributions, additional measures associated with the prediction biplot may be employed. Given that equations

25 and

26 define an Ordinal Logistic Regression model, any conventional measure of model fit for this framework can be utilized as an indicator of goodness of fit for each variable. In particular, pseudo-

indices (such as those proposed by Cox-Snell, McFadden, or Nagelkerke), the proportion of correct classifications , and the Kappa coefficient assessing the agreement between observed and predicted values may be considered.

Table 6 shows those measures.

We observe that the pseudo

measures are reasonably high except for the variable

DifProf. A review of the interpretation of the coefficients can be found in [

12].

The percentages of correct classification are reasonably high.

Ordinarily, the points representing individual subjects are not directly examined, except perhaps when the focus is on specific characteristics of a given subject and their corresponding behavior. More commonly, the analysis is directed toward understanding how groups of individuals perform in relation to the variables.

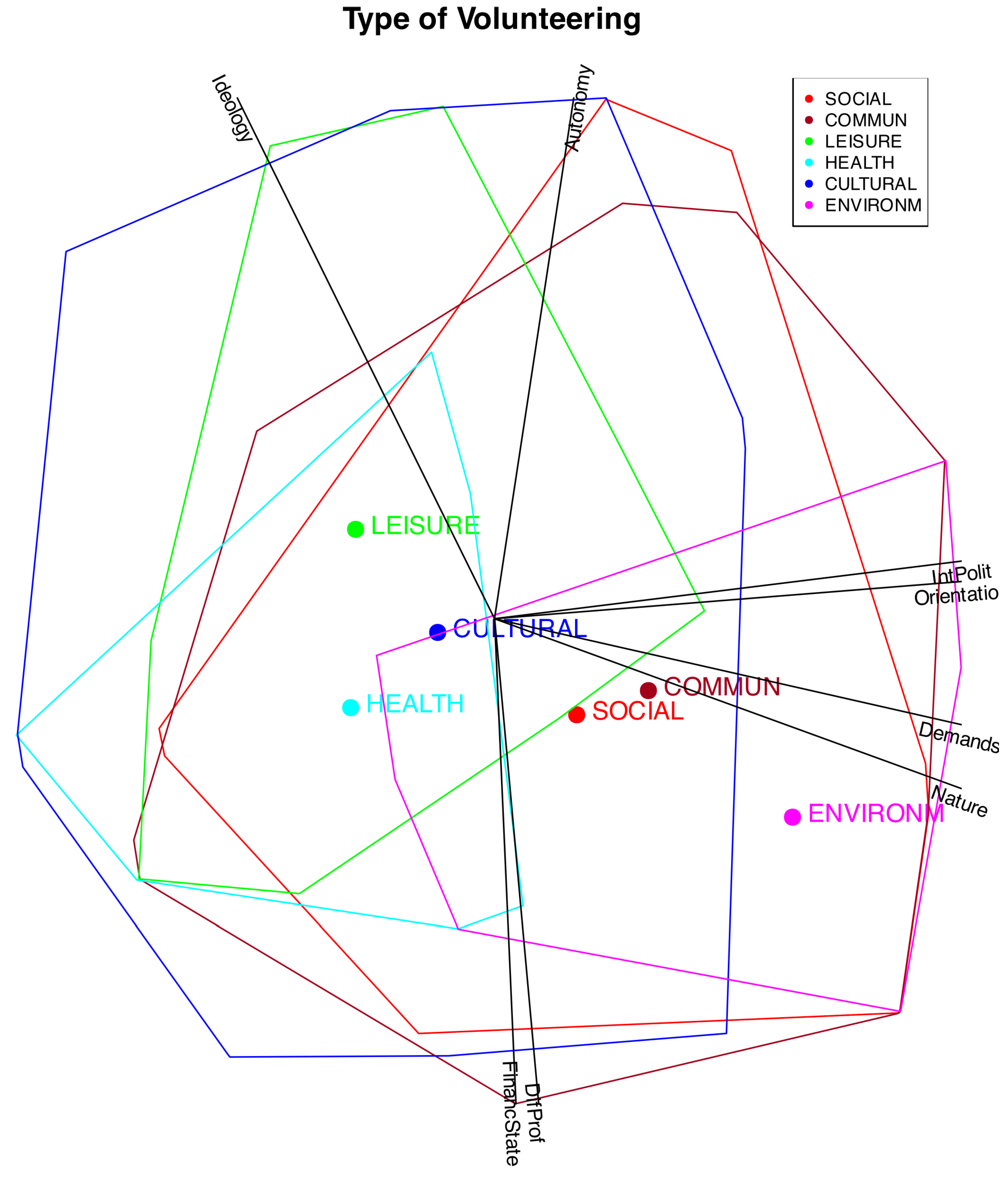

An effective strategy is to distinguish individuals from different groups or clusters by using color coding, enclosing them within convex hulls, or representing them through their group centroids. For instance,

Figure 11 illustrates convex hulls and centroids corresponding to various types of volunteering.

It can be observed that the different types are distributed along a gradient associated, on the one hand, with Ideology, and on the other, with Interest in Politics, Political Demands, Orientation of the Volunteering, and Nature of the Organization. In particular, the types Leisure, Health, and Cultural are linked to lower levels of political interest among volunteers, weaker political demands and orientations within organizations, and a stronger emphasis on welfare-oriented activities, and are also somewhat associated with a Right Ideology.

The other types?Social, Community, and Environmental?are associated with individuals who have a stronger interest in volunteer-related politics and with organizations that exhibit higher political demands, greater political orientation, and a transformative nature. Volunteers in these organizations, particularly in the environmental category, tend to align with left-leaning ideologies.

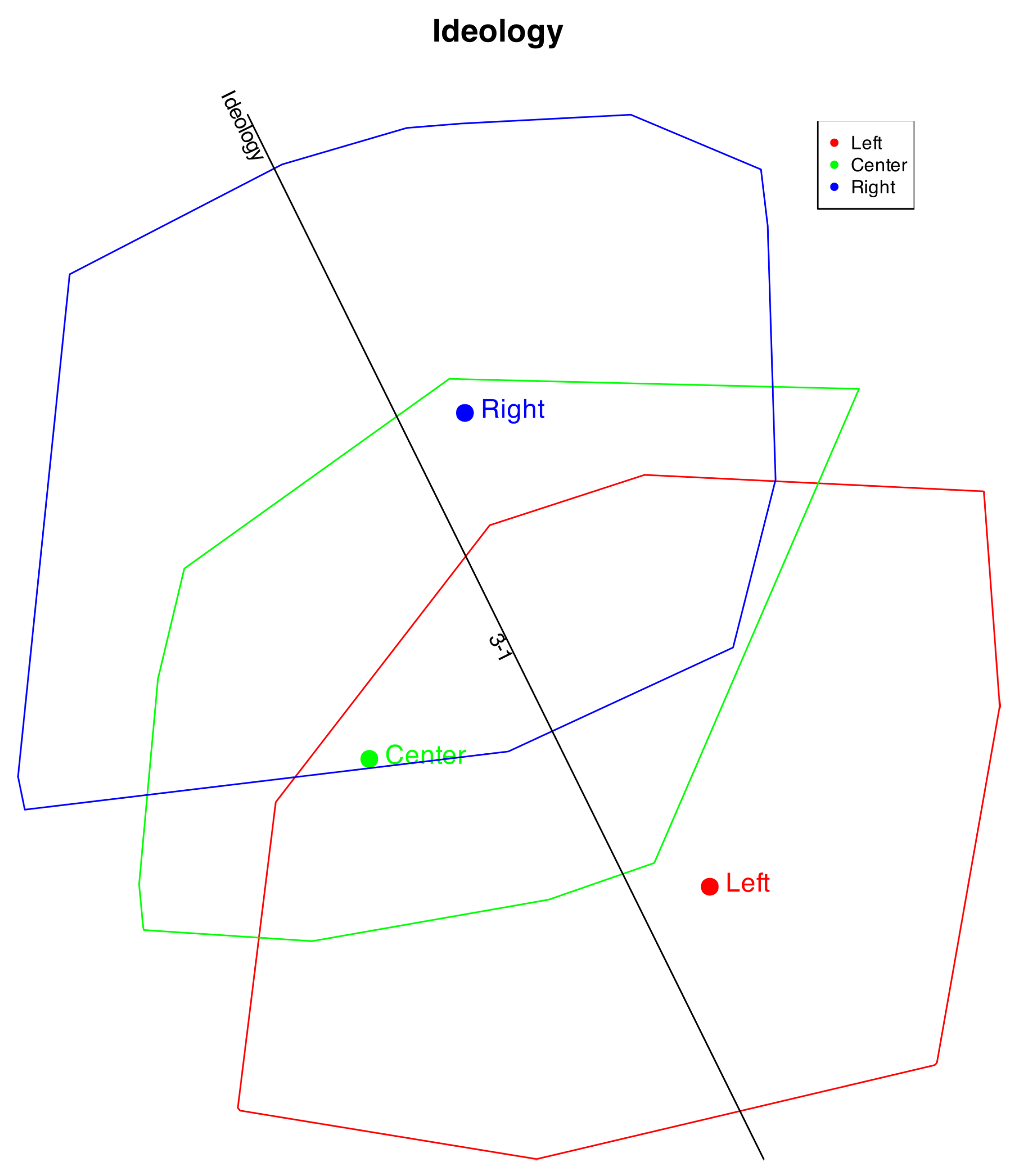

To check the performance of the method, we can add also cluters with the observed variables. For instance,

Figure 12 shows the clusters formed by ideology.

We observe that the ideological direction closely reflects the original data. The Left and Right positions are well distinguished, whereas the Center is not, likely because individuals identifying as Center sometimes hold opinions aligned with the Left and at other times with the Right. A similar pattern occurs with the middle categories in the other items.

In the prediction, category 2 is never identified; only categories 1 and 3 are predicted, as shown by the "1-3" mark. Individuals with Right or Left ideologies are mostly classified correctly, while those in the Center are split between the two extremes. Consequently, the overall classification accuracy is slightly lower. Overall, the respondents’ ideologies are well represented in the plot.

Figure 13 shows the clusters with all the variables.

We can see that all the variables, except profiles, are quite well represented in the plot. For all the cases with three categories the middle value is not well represented. For the variable profiles, we can see that both groups are mixed together, meaning that the factors do not discriminate among profiles.