Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biplot for Continuous, Binary or Nominal Data

2.1. Linear biplot for continuous data

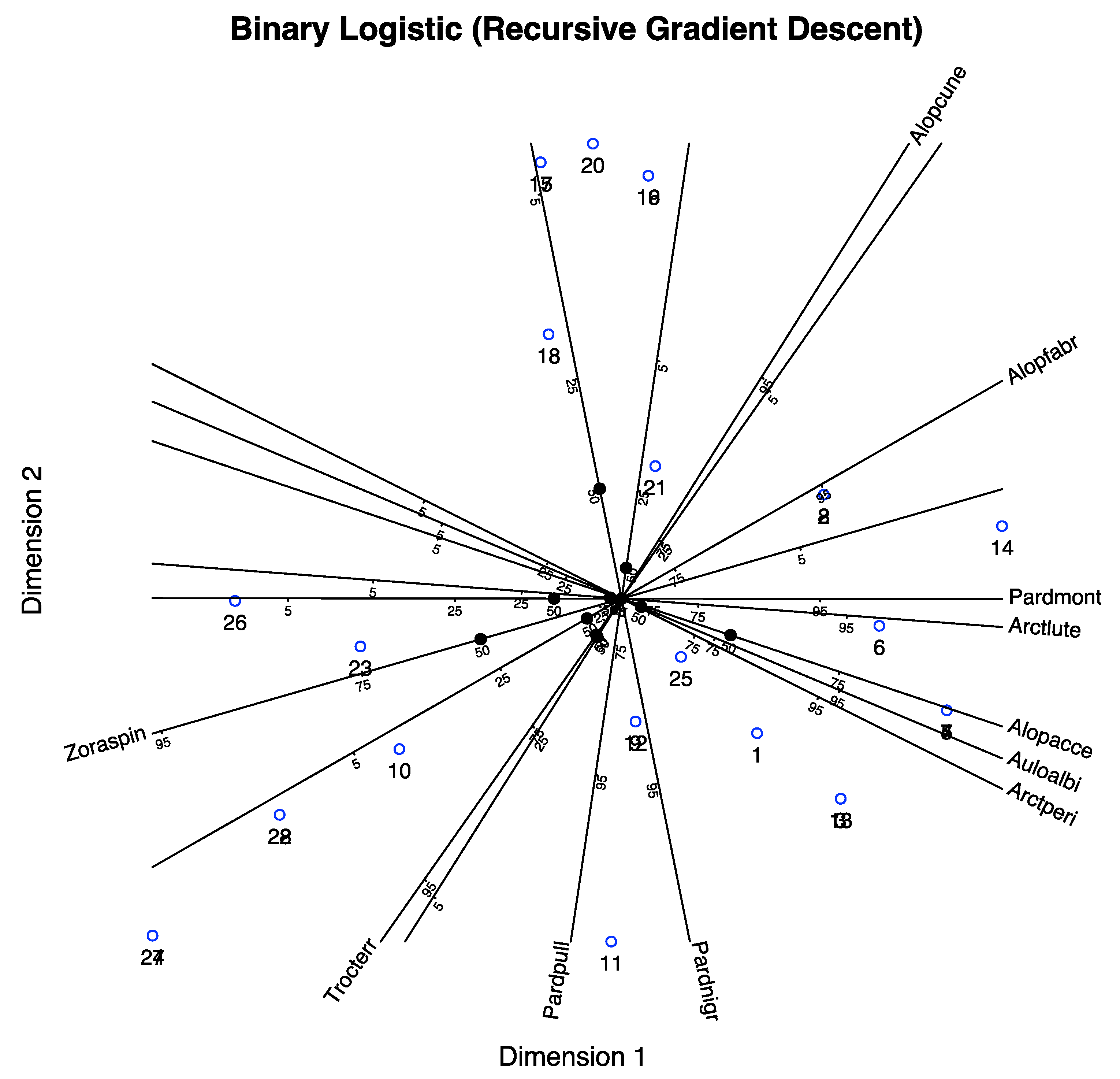

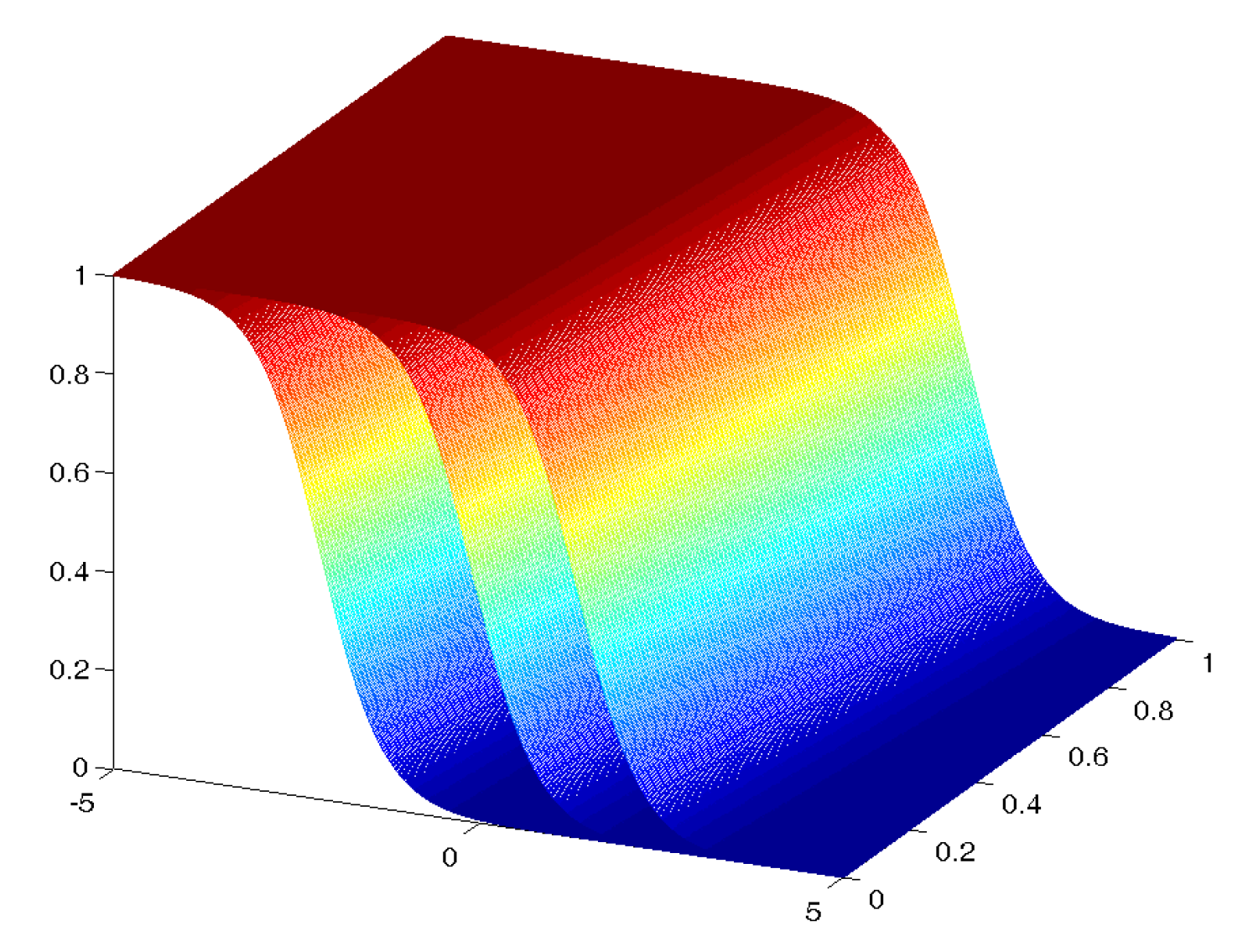

2.2. Logistic Biplot for Binary data

2.2.1. Formulation and Geometry

2.2.2. Parameter Estimation

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm to calculate the Components for Binary Data |

|

2.3. Logistic Biplot for Nominal data

3. Logistic Biplot for Ordinal Data

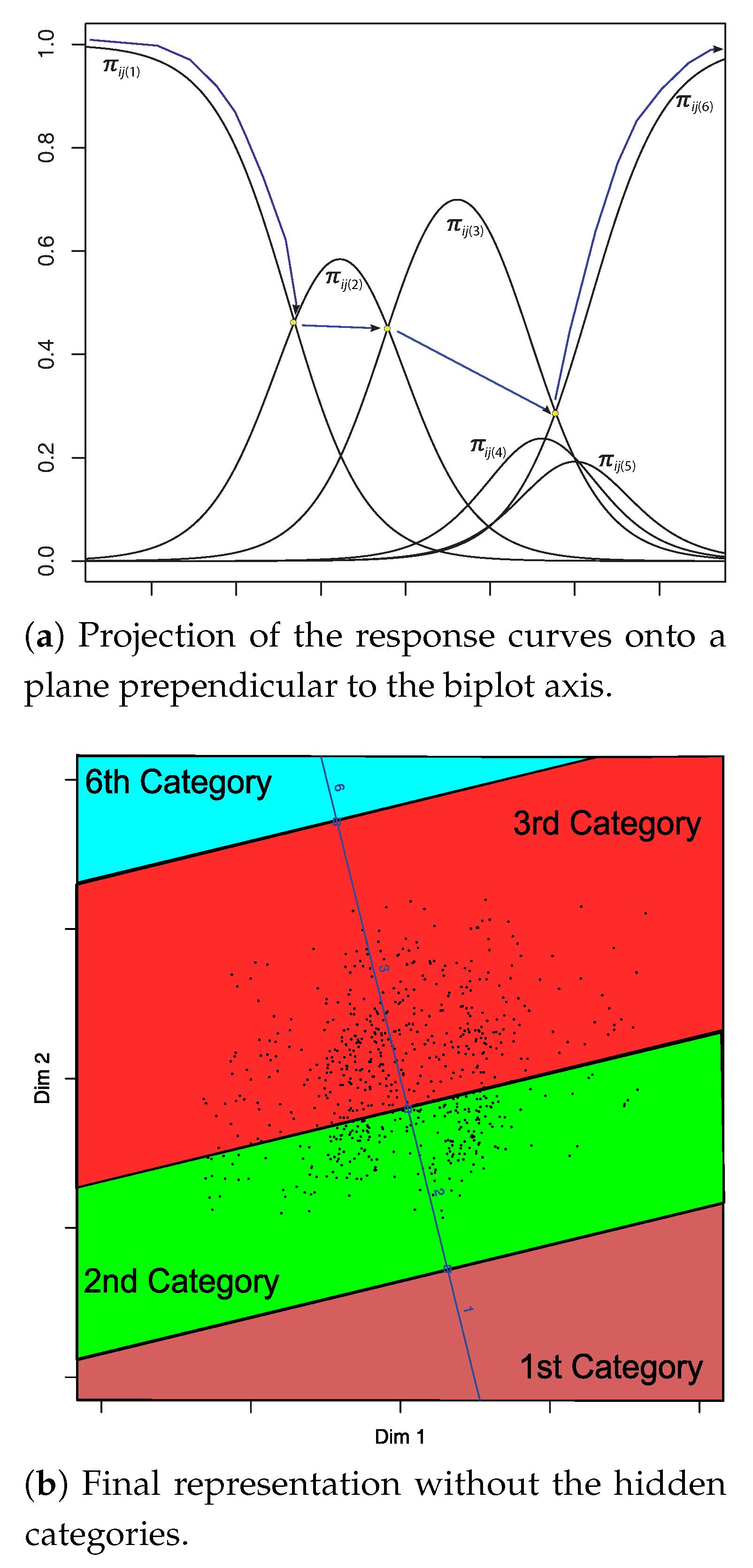

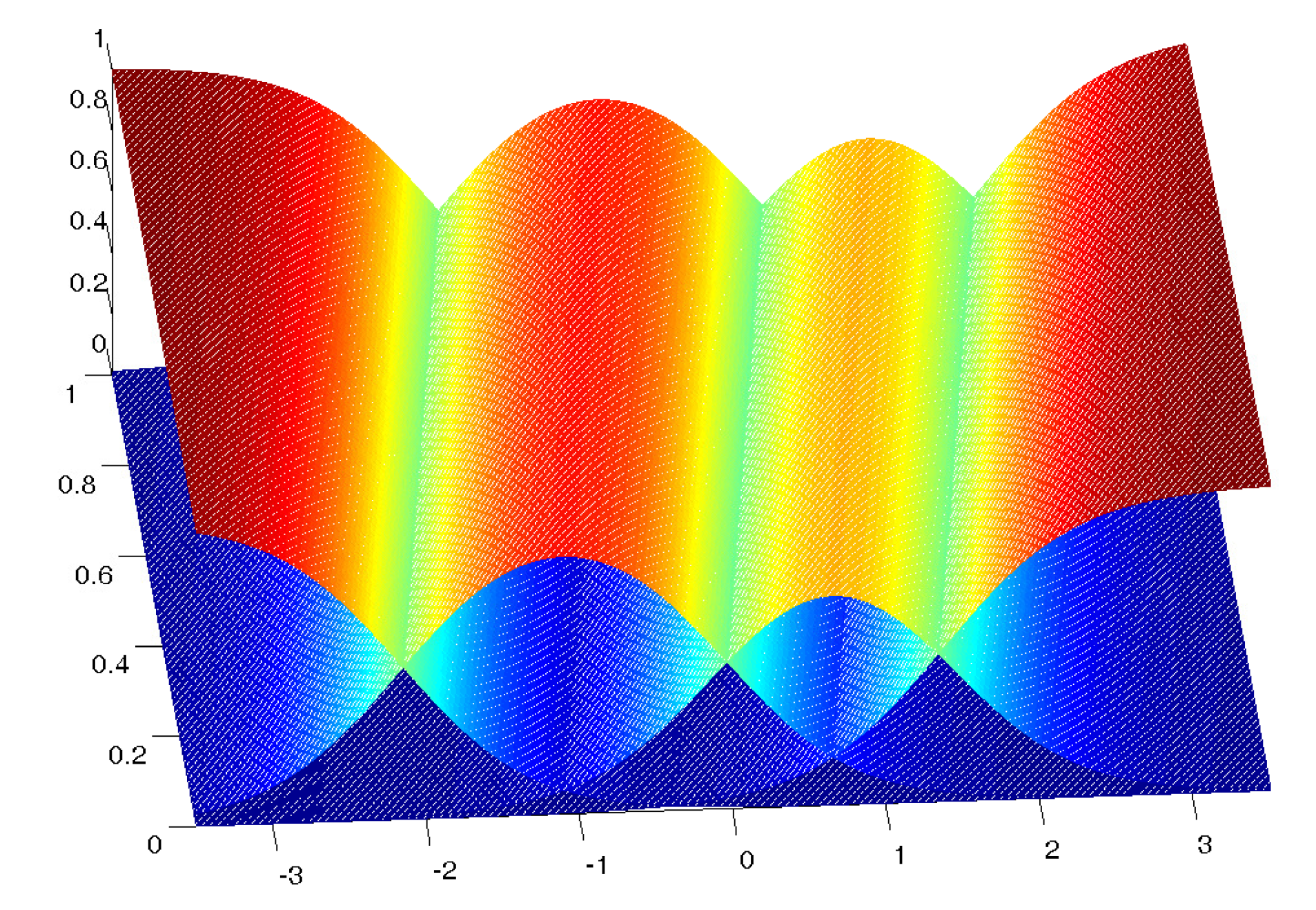

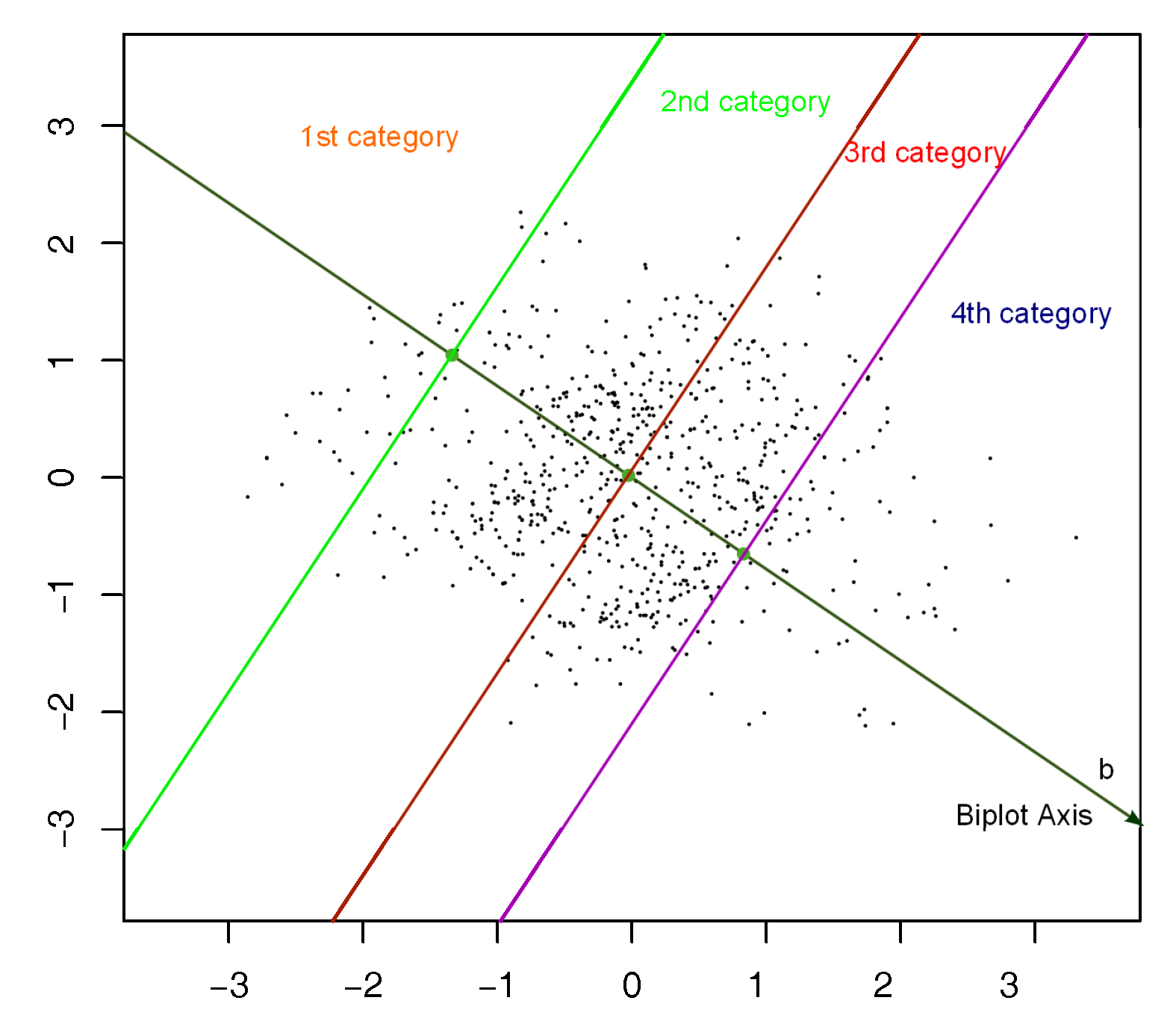

3.1. Formulation and Geometry

3.2. Obtaining the Biplot Representation

- 1-2

- 1-

- 1-

- l-

- l- with

- l-j with

- -

- Calculate the biplot axis with equation .

- Calculate the intersection points z and then of the biplot axis with the parallel lines used as boundaries of the prediction regions for each pair of categories, in the following order:

- If the values of z are ordered, there are not hidden categories and the calculations are finished.

-

If the values of z are not ordered we can do the following:

- (a)

- Calculate the z values for all the pairs of curves, and the probabilities for the two categories involved.

- (b)

- Compare each category with the following, the next to represent is the one with the highest probability at the intersection.

- (c)

- If the next category to represent is the process is finished. It not go back to the previous step, starting with the new category.

- Calculate the predicted category for a set of values for z. For example a sequence from -6 to 6 with small steps (0,01 or 0,01 for example). (The precision of the procedure can be changed with the step)

- Search for the z values in which the prediction changes from one category to another.

- Calculate the mean of the two z values obtained in the previous step and then the values. Those are the points we are searching for.

3.3. Parameter Estimation Based on an Alternated Gradient Descent Algorithm on the Cumulative Probabilities

| Algorithm 2 Algorithm to calculate the Components for Ordinal Data |

|

3.4. Factorization of the Polychoric Correlation Matrix

3.5. Goodness of Fit

4. An Empirical Study

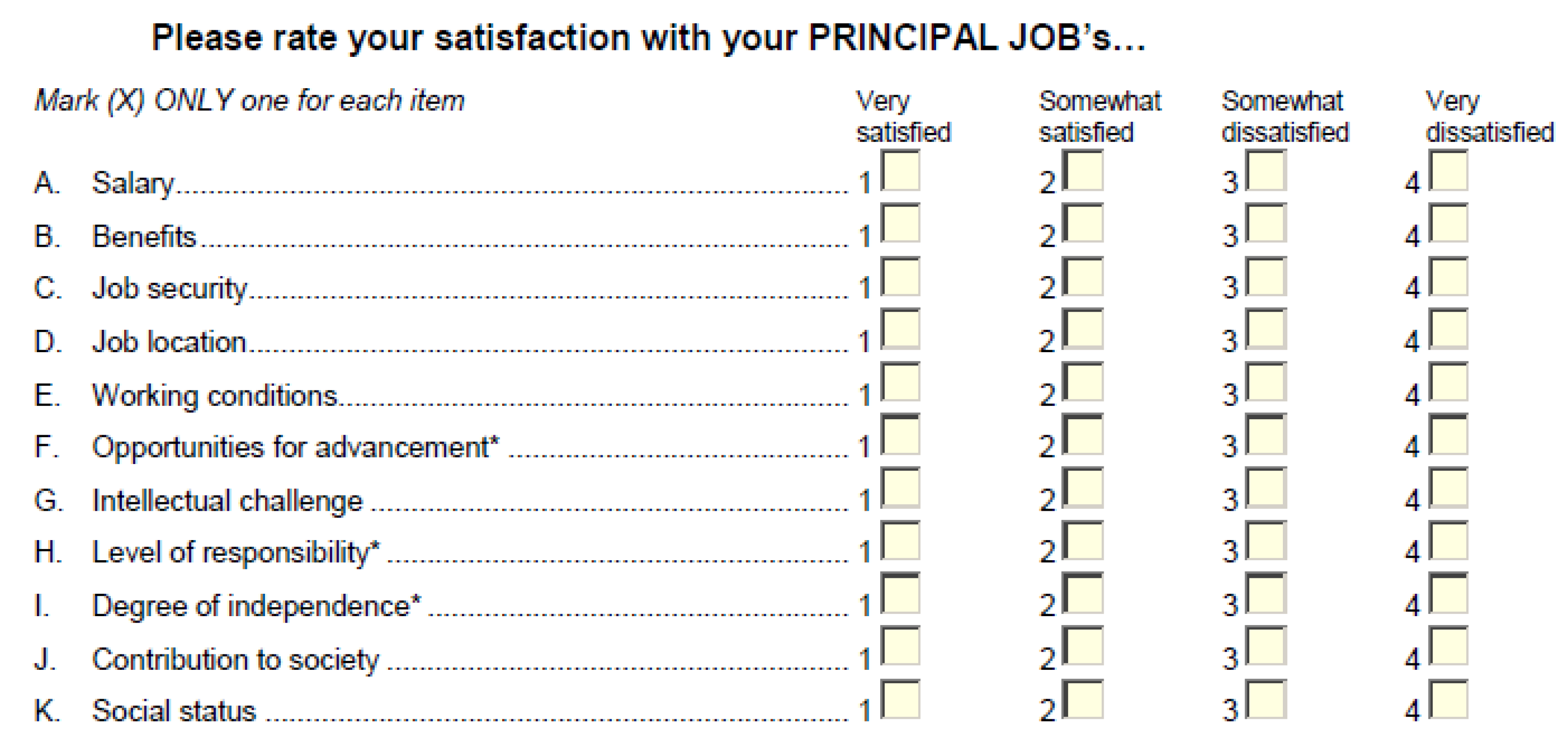

4.1. Dataset

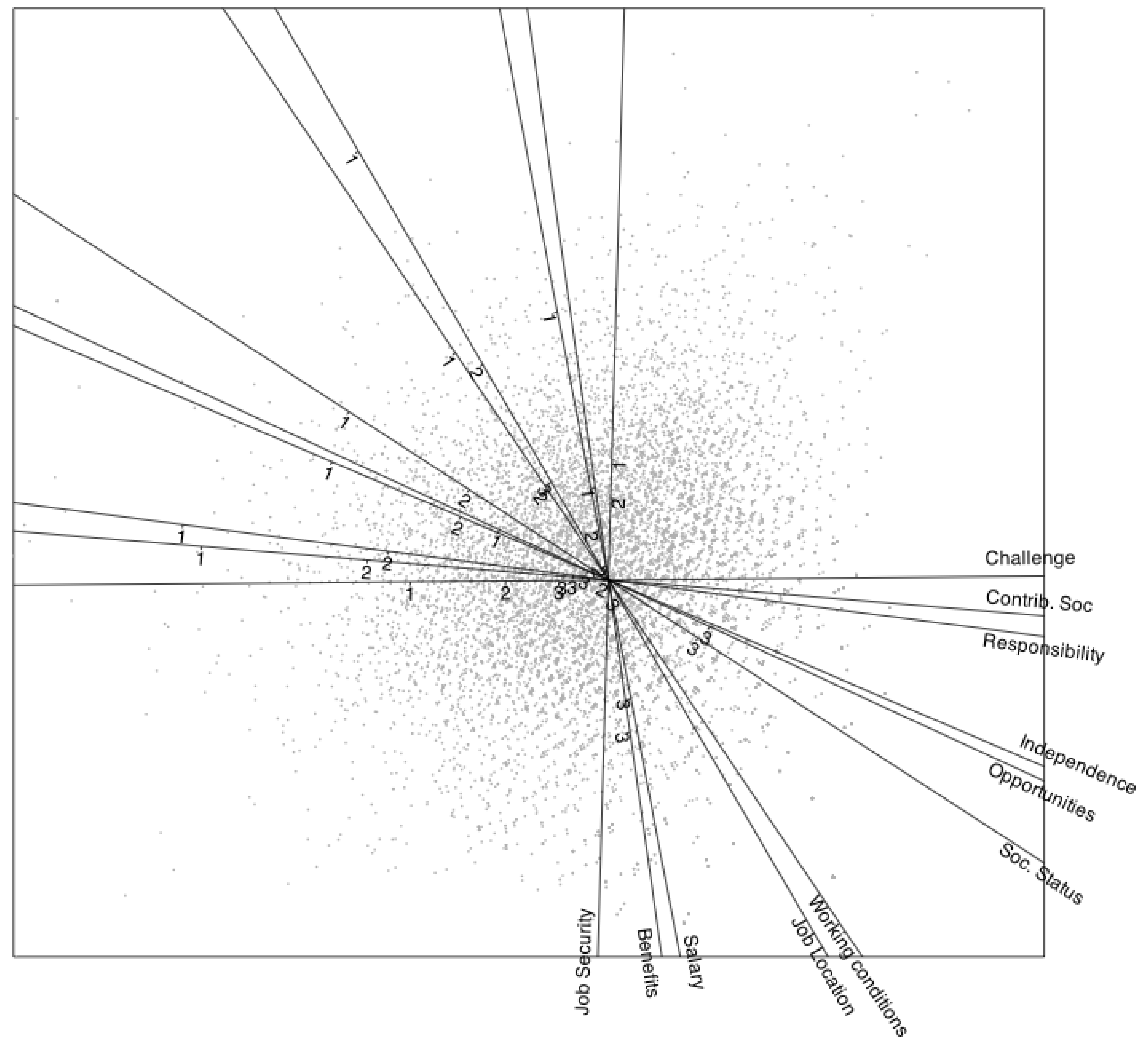

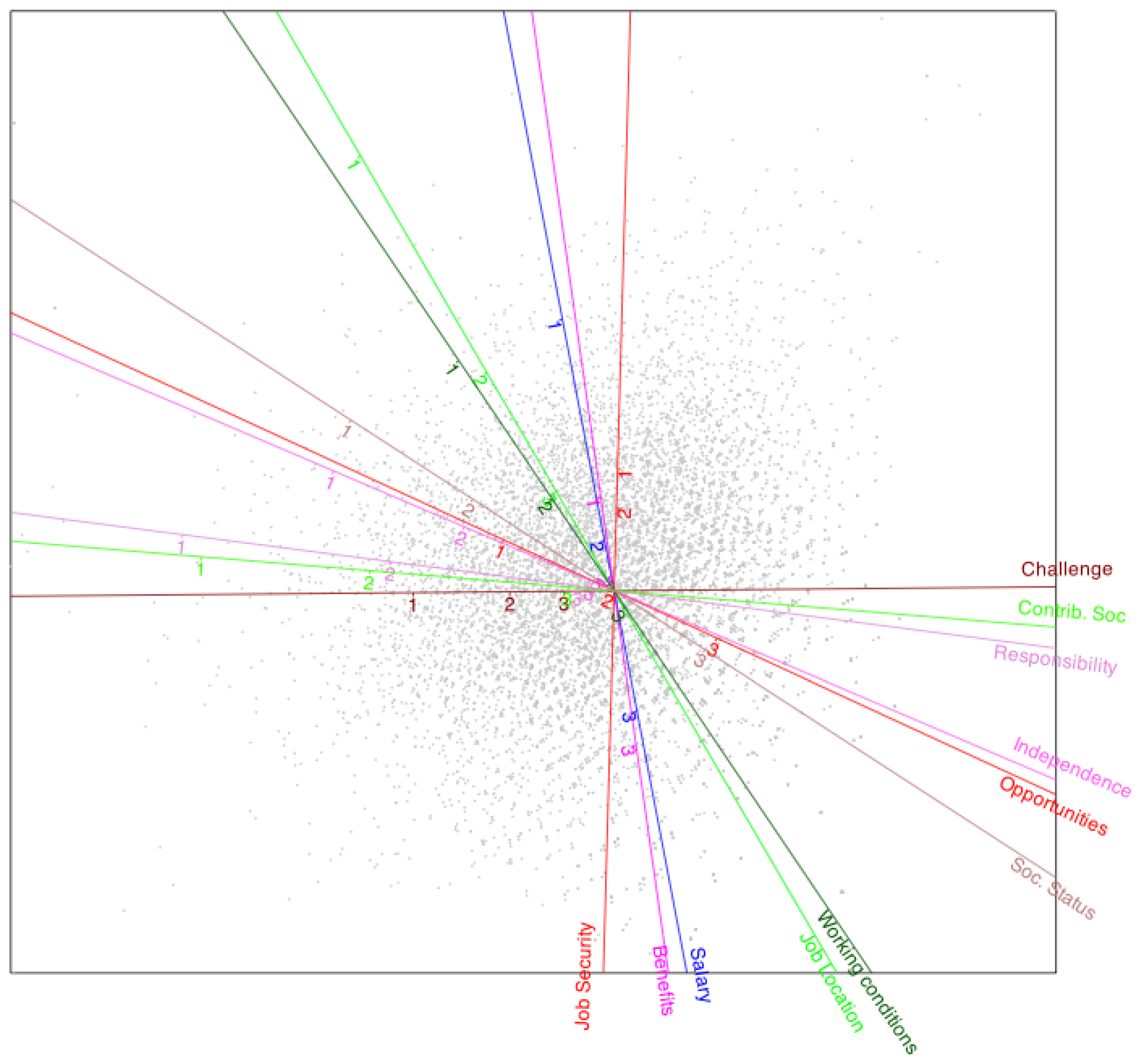

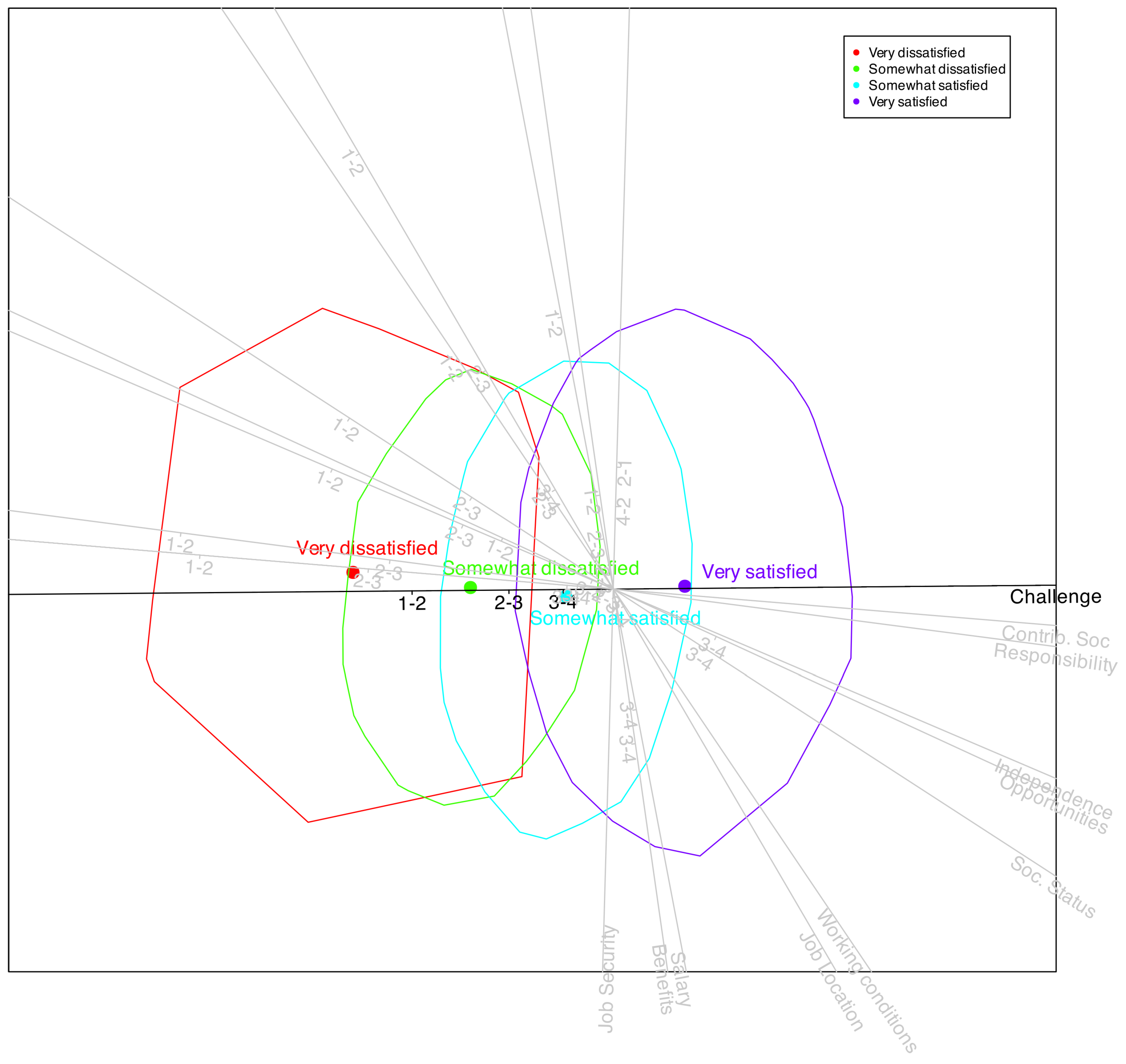

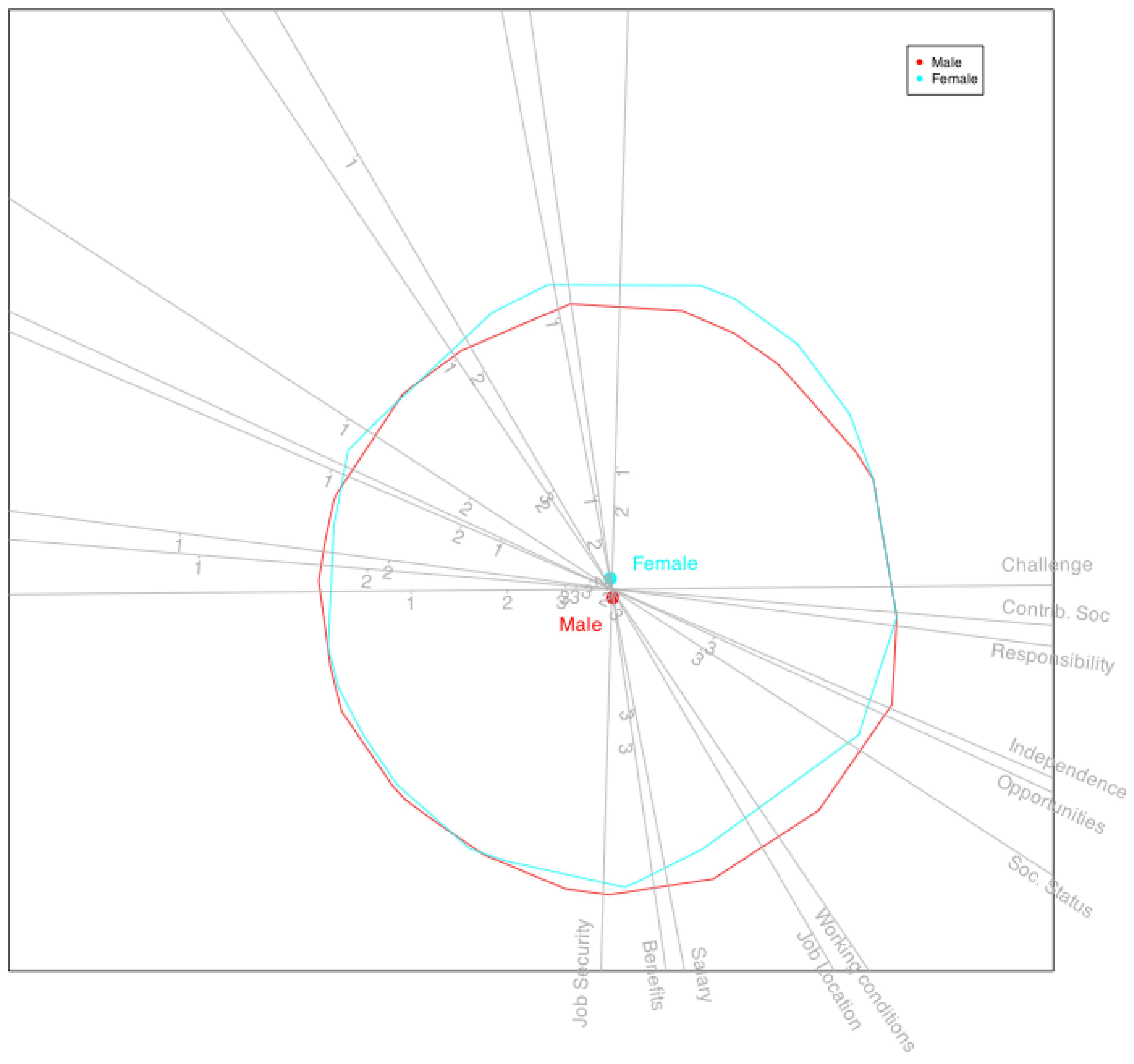

4.2. Results

5. Software Note

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babativa-Márquez, J. G. and Vicente-Villardón, J. L. Logistic biplot by conjugate gradient algorithms and iterated svd. Mathematics 2015, 9, 2015.

- Baker, F. (1992). Item Response Theory. Parameter Estimation Techniques. Marcel Dekker.

- Benzecri, J. P. (1976). L’analyse des donnees. Dunod.

- Canal, J. F. and Muniz, M. A. Professional doctorates and the careers: Present and future. the spanish case. European journal of education. 2012, 47, 153–171. [CrossRef]

- Cañueto, J., Cardeñoso-Álvarez, E., García-Hernández, J., Galindo-Villardón, P., Vicente-Galindo, P., Vicente-Villardón, J., Alonso-López, D., De Las Rivas, J., Valero, J., Moyano-Sanz, E., et al. (2017). Micro rna (mir)-203 and mir-205 expression patterns identify subgroups of prognosis in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. British Journal of Dermatology, 177(1):168–178.

- de Leeuw, J. (2006). Principal component analysis of binary data by iterated singular value decomposition. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 50(1):21–39.

- de Rooij, M., Breemer, L., Woestenburg, D., and Busing, F. (2024). Logistic multidimensional data analysis for ordinal response variables using a cumulative link function. Psychometrika, pages 1–37.

- Demey, J., Vicente-Villardón, J. L., Galindo, M. P., and Zambrano, A. (2008). Identifying molecular markers associated with classification of genotypes using external logistic biplots. Bioinformatics, 24(24):2832–2838.

- Gabriel, K. (1971). The biplot graphic display of matrices with application to principal component analysis. Biometrika, 58(3):453–467.

- Gabriel, K. R. (1980). Biplot display of multivariate matrices for inspection of data and diagnosis. Technical report, ROCHESTER UNIV NY.

- Gabriel, K. R. (1998). Generalised bilinear regresion. Biometrika, 85(3):689–700.

- Gabriel, K. R. (2002). Goodness of fit of biplots and correspondence analysis. Biometrika, 89(2):423–436.

- Gabriel, K. R., Galindo, M. P., and Vicente-Villardon, J. L. (1998). Use of Biplots to diagnose independence models in contingency tables., pages 391–404. Academic Press.

- Gabriel, K. R. and Zamir, S. (1979). Lower rank approximation of matrices by least squares with any choice of weights. Technometrics, 21(4):489–498.

- Galindo-Villardon, M. P. (1986). Una alternativa de representacion simultanea: Hj-biplot. Questiio, 10(1):13–23.

- Gallego, I. and Vicente-Villardon, J. L. (2012). Analysis of environmental indicators in international companies by applying the logistic biplot. Ecological Indicators, 23(0):250 – 261.

- Gallego-Alvarez, I., Ortas, E., Vicente-Villardón, J. L., and Álvarez Etxeberria, I. (2017). Institutional constraints, stakeholder pressure and corporate environmental reporting policies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(6):807–825.

- Gardner-Lubbe, S., Le Roux, N., and Gower, J. (2008). Measures of fit in principal component and canonical variate analyses. Journal of Applied Statistics, 35(9):947–965.

- Gower, J. and Hand, D. (1996). Biplots. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. 54. London: Chapman and Hall., 277 pp.

- Greenacre, M. J. (1984). Theory and Applications of Correspondence Analysis. Academic Press.

- Hernández, J. C. and Vicente-Villardón, J. L. (2013). Ordinal Logistic Biplot: Biplot representations of ordinal variables. Universidad de Salamanca.Department of Statistics. R package version 0.3.

- Hernández-Sánchez, J. C. and Vicente-Villardón, J. L. (2017). Logistic biplot for nominal data. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification, 11(2):307–326.

- Jöreskog, K. G. and Moustaki, I. (2001). Factor analysis of ordinal variables: A comparison of three approaches. Multivariate Behavioral Research,, 36(3):347–387.

- la Grange, A., le Roux, N., and Gardner-Lubbe, S. (2009). Biplotgui: Interactive biplots in r. Journal of Statistical Software, 30(12).

- Lee, S., Huand, J., and Hu, J. (2010). Sparse logistic principal component analysis for binary data. Annals of Applied Statistics, 4(3):21–39.

- Mair, P., Reise, S. P., and Bentler, P. (2008). Irt goodness-of-fit using approaches from logistic regression. UCLA Statistics Preprint Series, 540.

- R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometric Monograph Supplement, 4(34).

- Schwabe, M. (2011). The careers paths of doctoral graduates in austria. European Journal of Education., 46(1):153–168.

- Song, Y., Westerhuis, J. A., and Smilde, A. K. (2020). Logistic principal component analysis via non-convex singular value thresholding. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 204:104089.

- Vicente-Galindo, P., de Noronha Vaz, T., and Nijkamp, P. (2011). Institutional capacity to dynamically innovate: An application to the portuguese case. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(1):3 – 12.

- Vicente-Gonzalez, L. and Vicente-Villardon, J. L. Partial least squares regression for binary responses and its associated biplot representation. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2580. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Villardon, J., Galindo, M., and Blazquez-Zaballos, A. (2006). Logistic Biplots., pages 503–521. Chapman and Hall.

- Vicente-Villardon, J. L. (2022). MultBiplotR: Multivariate Analysis Using Biplots in R. R package version 2.1.3.

- Vicente-Villardon, J. L. and Sanchez, J. C. H. (2014). Logistic biplots for ordinal data with an application to job satisfaction of doctorate degree holders in spain.

| PCC(Cum) | Cox-Snell | MacFadden | Nagelkerke | PCC | Kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | 90.49 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 71.26 | 0.58 |

| Benefits | 86.60 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 58.75 | 0.52 |

| Job Security | 86.81 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 65.32 | |

| Job Location | 84.93 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.22 | 61.56 | 0.18 |

| Working conditions | 88.81 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 66.04 | 0.55 |

| Opportunities | 85.40 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 56.06 | 0.51 |

| Challenge | 91.65 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 71.53 | 0.64 |

| Responsibility | 87.70 | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.36 | 63.80 | 0.38 |

| Independence | 87.56 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 63.24 | 0.45 |

| Contrib. Soc | 88.61 | 0.37 | 0.77 | 0.37 | 66.57 | 0.39 |

| Soc. Status | 89.74 | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.40 | 70.30 | 0.41 |

| Global | 88.03 | 64.95 |

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Communalities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | 0.16 | -0.82 | 0.70 |

| Benefits | 0.12 | -0.82 | 0.69 |

| Job Security | -0.02 | -0.86 | 0.74 |

| Job Location | 0.33 | -0.57 | 0.44 |

| Working conditions | 0.47 | -0.70 | 0.72 |

| Opportunities | 0.76 | -0.35 | 0.69 |

| Challenge | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.76 |

| Responsibility | 0.77 | -0.10 | 0.61 |

| Independence | 0.75 | -0.32 | 0.66 |

| Contrib. Soc | 0.78 | -0.06 | 0.62 |

| Soc. Status | 0.66 | -0.43 | 0.63 |

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Variance | 3.92 | 3.34 |

| Cummulative | 3.92 | 7.25 |

| Percentage | 35.61 | 30.32 |

| Cum. Percentage | 35.61 | 65.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).