1. Introduction

In 1904, Charles Spearman introduced a groundbreaking statistical methodology aimed at uncovering latent variables, those not directly measurable but estimable through observed correlations. Spearman’s approach, inspired by the pioneering work of Galton and Pearson, sought to operationalize the existence of two intelligence factors inferred from children’s school performance. He posited a general intelligence factor (G factor) and a specific intelligence factor (S factor), suggesting that positive correlations across seemingly unrelated subjects indicated these underlying factors (Spearman, 1904a).

Although Spearman’s theory of intelligence factors faced challenges from researchers like Thomson (1916) and Thurstone (1938),, his method, Exploratory Factor Analysis, became a cornerstone in psychometry. This approach facilitated the estimation of intangible attributes, contributing significantly to the development of psychological assessment.

Around the same period, Rensis Likert (1932) introduced his influential scale to measure opinions and attitudes. This scale, composed of 7-point response items coded from 1 to 7, quickly gained popularity in psychology and remains widely used today for assessing latent psychometric variables.

Consequently, factor analysis is frequently employed to uncover the latent constructs assessed by Likert and similar rating scales. However, the validity of results obtained through factor analysis of ordinal items, which comprise a significant portion of psychometric scales used in daily psychological assessments, remains controversial. Ongoing debates, such as those discussed by Liddell and Kruschke (2018), underscore the need to consider both traditional and modern solutions when addressing the challenges associated with factor analysis of ordinal items.

1.1. Factor Analysis

Factor analysis aims to uncover latent variables through observed correlations. For instance, in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), responses to mood-related items reflect latent depression, with correlations among these items indicating its presence. Spearman’s factor analytic model, explains observed variables’ behavior through latent factors. Thurstone (1938) and Cattell (1943) expanded this model, introducing exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a reduced set of common factors and specific factors for each variable. Here a set of observerved variables (

X1,

X2,…

Xp) can be explained by a reduced

m common factors (

m<< p) and

p specific factors as

1:

where

mi represents the expected value of variable

xi, l

ik represents the loading of factor

k (k ∈{1, …, m}) on variable

i,

fkj represents the common factor

k for individual

j (

j ∈{1,…,

n}), and e

ij represents the residual or specific factor associated with observed

variable i (i ∈{1, …, p}) on individual

j . Common factors are assumed to be independent and specific factors are assumed independent and normally distributed.

The factor analysis can be done on the covariance matrix of the observed variables estimated as:

whose generic element is Galton’s covariance:

Since variables in the social sciences and humanities often have different scales and ranges of measurement, it is common to standardize them, centering the mean to 0 and reducing the standard deviation to 1 as

. The variance-covariance matrix is then reduced to the matrix of the product-moment correlations, also known as Pearson’s correlations:

whose generic element is Pearson’s well-known correlation coefficient:

Using standardized variables, model (1.1) can now be written in matrix form, as:

where L is a matrix of factor loadings, f is a vector of common factors, and e is a vector of specific factors. From model 1.7 the correlation matrix can then be written as:

where y is the diagonal covariance matrix of the specific factors. Common factor loadings can be estimated from eq. 8. However, this equation is nonidentified

2, so Spearman, in his “method of correlations” followed Pearson’s Principal Components method for factorizing the correlation matrix. The variables’ communality (see eq. 2) are therefore estimated as the eigenvalues of the principal components retained from the correlation matrix. More recent methods of extraction of the common factors include the principal axis factoring method and the maximum likelihood method (de Winter and Dodou, 2011). In short, the principal axis factorization method considers that the initial communalities are the coefficient of determination of each variable regressed on all others (and not 1, as in the principal components method) proceeding with an analysis of principal components in a optimization algorithm that stops when the extracted communalities reach their maxima. The maximum likelihood method, as proposed by Lawley and Maxwell (1962), estimates the factor loadings that maximize the likelihood of sampling the matrix of observed correlations in the population. The solution is obtained by minimizing the maximum likelihood (ML) function

3

for and y by a two-step algorithm that estimates the eigenvalues (common factor variance) and specific factor variances of the correlation matrix R.

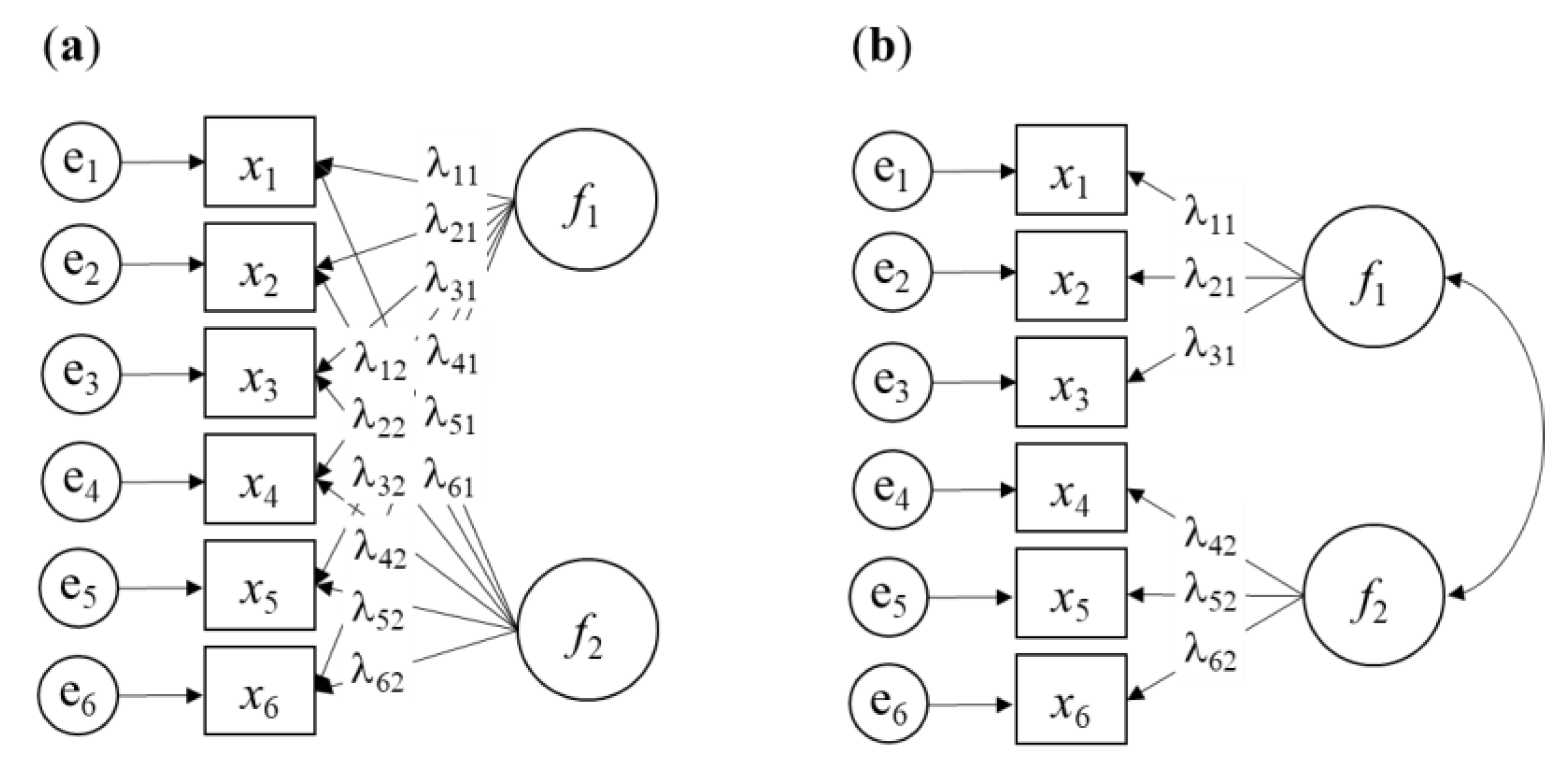

Since the late ‘60s, the maximum likelihood method has been widely used in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Jöreskog, 2007). In CFA, a predefined factor structure is validated, imposing theoretical constraints on the model, in contrast to the “free” estimation in EFA. The key difference between the two models lies in the specific loading of common factors on items in CFA, while EFA allows all common factors to potentially load on all items as illustrated in

Figure 1.

This section provides a condensed overview of factor model parameter estimation methods, as detailed in Jöreskog (2007) and Marôco

(2021b). Iterative techniques minimize a discrepancy function

f (Equation 10) using sample variance-covariance matrix (S) and expected covariance matrix (

):

For maximum likelihood estimation (ML), under the normality assumption for the manifest variables, the discrepancy function to minimize is

Non-normal data analysis recommends the Asymptotic Distribution Free (ADF) (Arbuckle, 2006) or Weighted Least Squares (WLS) (Li, 2014) estimators:

The generic element of W, calculated from the sample covariance elements and fourth-order moments of the observed

x variables, is (Finney & DiStefano, 2013):

The WLS estimator, considering sample covariances and fourth-order moments, may face convergence issues with small samples (<200), addressed by Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) or Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance (WLSMV), both special cases of WLS. However, ignoring item covariances reduces statistical efficiency, impacting model fit. Ordinal factor analysis utilizes the polychoric correlation matrix, with WLS estimator incorporating sample polychoric correlations and thresholds to estimate the asymptotic covariance matrix (W) (Finney & DiStefano, 2013; Muthén, 1984):

where R is the matrix of the polychoric correlations and thresholds estimated from the sample;

is the model implied correlation and thresholds.

Stanley Stevens and the Scales of Measurement

During the 1930s-40s, Stanley Stevens introduced a taxonomy for “scales of measurement,” influenced by the work of a committee from the British Association for the Advancement of Science (N. Campbell, p. 340 of the Final Report, cit in Stevens, 1946). Stevens proposed four scales: Nominal, Ordinal, Interval, and Ratio, which unified qualitative and quantitative measurements. Nominal scales evaluate attributes without magnitude, permitting only frequency and classification. Ordinal scales sort categories without quantifiable order, allowing classification and sorting operations. Interval scales record attributes with fixed intervals but lack an absolute zero, allowing distance comparison but not ratios. Ratio scales assess attributes with interpretable and comparable ratios. Stevens also outlined permissible central tendency and dispersion measures for each scale: nominal scales report modes; ordinal scales report modes, medians, and percentiles but not means or standard deviations; interval or ratio scales allow means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients. Ratio-based statistics, like the coefficient of variation, are only admissible for ratio scales.

1.1.1. Is it Permissible to do Factor Analysis with Ordinal Items?

Stevens’s taxonomy profoundly influenced the social sciences, particularly psychology, guiding statistical analysis for qualitative and quantitative variables. Many textbooks and statistical software rely on his taxonomy for recommendations on appropriate statistical analysis methods. However, criticisms of Stevens’s taxonomy have emerged (Lord, 1953; Velleman & Wilkinson, 1993). Controversy remains regarding the treatment of variables measured on an ordinal scale (Feuerstahler, 2023). Stevens recognizes that most scales used effectively by psychologists are ordinal scales and thus “In the strictest propriety the ordinary statistics involving means and standard deviations ought not to be used with these scales” (Stevens, 1946, p. 679). However, on the same page, Stevens recognizes that “On the other hand, for this ‘illegal’ statisticizing there can be invoked a kind of pragmatic sanction: In numerous instances, it leads to fruitful results.” Despite pragmatic justification for their use, some methodologists advocate against using such statistics for ordinal variables (Jamieson, 2004; Liddell & Kruschke, 2018). According to Stevens, only the mode, median, and percentiles are permissible for ordinal variables. Prohibiting statistics like mean and correlation coefficients raises concerns for psychometry, where Likert items and factor analyses are prevalent. If statistics not permissible for ordinal scales are banned, could it compromise the validity of “correlational psychology” (Spearman, 1904b, p. 205) and countless psychometric scales derived from ordinal measures through factor analysis on the Pearson correlation matrix? The validity of decades of psychometric research may be at risk?

2. Other Methods to Analyze Ordinal Items

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, driven by the need to empirically validate theoretical models across diverse populations. Jöreskorg and Sörbom developed LisRel, the first commercial software for structural equation modeling, laying the groundwork for CFA. Babakus, Ferguson, & Jöreskog (1987) conducted a seminal simulation study on CFA of ordinal items, finding that factor loadings estimated with polychoric correlations surpassed those obtained with Pearson’s, Spearman’s, and Kendall’s correlations. This study confirmed previous observations that Pearson correlations tend to underestimate factor loadings, particularly with ordinal items having fewer than 5 categories and considerable asymmetry. Independent simulation studies have corroborated these findings, noting that as the number of categories increases and distribution bias decreases, Pearson correlation estimates approach those of quantitative variables (Bollen, 1989; Rhemtulla et al., 2012).

2.1. The Spearman Correlation Coefficient

Spearman developed his correlation coefficient as an alternative to Pearson’s, specifically for variables that couldn’t be quantitatively measured. Spearman’s rho, based on rank differences, is an adaptation of Pearson’s coefficient applied to the ranks (

rx1i, rx2i ) rather than the original observations (

x1i, x2i) (Spearman, 1904a):

2.2. The Polychoric Correlation Coefficient

The polychoric correlation coefficient, introduced by Karl Pearson in 1900, evaluates correlations between non-quantitatively measurable characteristics. This coefficient gained attention in factor analysis after simulation studies demonstrated its superiority in estimating associations between ordinal items (Babakus et al., 1987; Finney & DiStefano, 2013; Finney et al., 2016a; Holgado-Tello et al., 2009; Li, 2016; Muthén, 1984). It assumes that qualitative characteristics on ordinal or nominal scales result from discretized continuous latent variables with bivariate normal distributions. Thus, the polychoric correlation coefficient estimates the linear association between two latent variables operationalized by ordinal variables (e.g., Likert-type items). For instance, an item with 5 categories, such as an agreement scale, is conceptualized as dividing a latent variable into categories defined by thresholds on the latent z:

The observed variable’s five response categories represent an approximation of the five intervals at which the latent continuous variable, denoted as

ξ, has been divided using four cutoff points or thresholds:

ξ₁,

ξ₂,

ξ₃, and

ξ₄. Each of these

k-1 thresholds can be determined based on the relative frequency of the

k categories, assuming normality:

where F

-1 is the inverse of the normal distribution,

nk is the absolute frequency of the item’s

k category, and

N is the total of the item’s responses. By convention

ξ0=-∞ and

ξ5 =+∞. The polychoric correlation coefficient is generally estimated by maximum likelihood (see e.g. Drasgow, 1986). In a two-step algorithm, the procedure begins by estimating the tresholds for

x1 and for

x2. If the category

i of variable

x1 is observed when x

1i-1 ≤x

1< x

1i and if category

j of variable

x2 is observed when x

2j-1 ≤ x

2 < x

2j then the joint probability (

Pij ) of observing the category

x1i and

x2j is:

where

is the bivariate normal density function of x

1 and x

2 with m =0 and s = 1 (without loss of generality, since the original latent variables are origin- and scale-free), and Pearson correlation r. If

nij is the number of observations

x1i of

X1 and

x2j of

X2, the sample likelihood is:

where

k is a constant and

r and

s are the number of categories of

X1 and

X2, respectively. In the second step, the maximum likelihood estimate of the polychoric correlation coefficient

(r) is obtained by deriving the

Ln(L) in respect to r:

Equating the partial derivatives of (19), in respect to all model parameters, to 0 and solving it in respect to r gives the polychoric correlation estimate (Drasgow, 1986). The asymptotic covariance matrix of the estimated polychoric correlations can then be estimated using computational methods derived by Jöreskog (1994) after Olsson (1979). The maximum likelihood solution is, generally, obtained iteratively in several commercial software (e.g., Mplus, LisRel, EQS), free software ( R psych and polycor packages) but not in IBM SPSS Statistics (up to version 29).

Simulation studies suggest that the polychoric correlation coefficient outperforms Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlations in reproducing the correlational structure of latent variables when operationalized as ordinal observed variables However, its usefulness as an alternative to the Pearson correlation coefficient is debated. For small samples (n < 300 - 500) with many variables, polychoric correlations may not yield better results than Pearson correlations (Rigdon & Ferguson, 2006). Additionally, assumptions of bivariate normality and large sample sizes (> 2000 observations) are needed for accurate estimation, posing challenges in practical structural equation modeling (Arbuckle, 2006; Yung & Bentler, 1994). Moreover, the polychoric correlation lacks statistical robustness when the underlying distribution deviates strongly from bivariate normality, leading to potential inaccuracies in ordinal factor analysis (Ekström, 2011; Robitzsch, 2020). It may also introduce bias when ordinal factor models impose a normality assumption for underlying continuous variables, which might also often be true in empirical applications (Grønneberg & Foldnes, 2024; Robitzsch, 2020, 2022).

This paper compares Pearson’s, Spearman’s, and Polychoric correlation coefficients using real and simulated data. It demonstrates calculating these coefficients using statistical software and applying the matrices in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA). The findings are discussed regarding their implications for practical factor analysis applications.

3. Results

3.1. Case Study 1. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Items with 3 Points

To demonstrate factor analysis with ordinal items, data from a study on voters’ perceptions (Marôco, 2021a) using a 3-point ordinal scale is considered. Items include “People like me have no voice” (WithoutVoice), “Politics and government are too complex” (Complex), “Politicians are not interested in people like me” (Desinter), “Politicians once elected quickly lose contact with their voters” (Contact), and “Political parties are only interested in people’s votes” (Parties). Using IBM SPSS Statistics, classical EFA can be conducted on the covariance matrix or Pearson correlation matrix. Syntax for factor extraction using principal components with Varimax rotation on the correlation matrix is provided as supplementary material. Furthermore, EFA can be performed on the Spearman correlation matrix in SPSS Statistics. Syntax involves converting variables to ranks before conducting factor analysis. Lastly, EFA on the polychoric correlations matrix is discussed. Since SPSS Statistics does not compute polychoric correlations, one can calculate and import the matrix from R using the polycor package (Fox, 2016). Pearson, Spearman, and Polychoric correlation matrices for the 5 items are shown in

Table 1.

With IBM SPSS Statistics, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) can now be conducted on the polychoric correlation matrix, along with other desired correlation matrices.

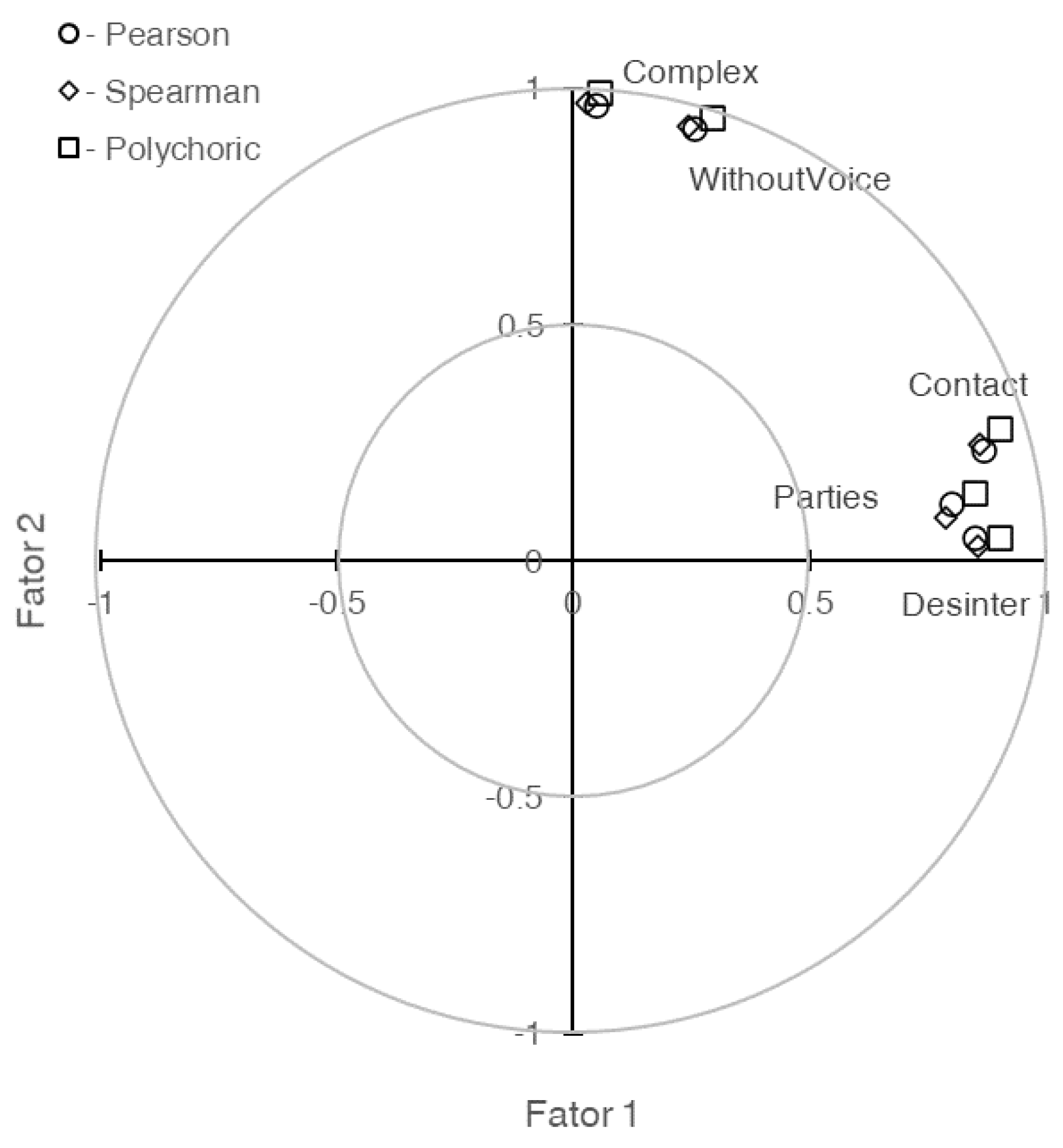

Table 2 provides a summary of the relevant results from the three EFAs conducted on the Pearson, Spearman, and Polychoric correlation matrices. Factors were extracted using Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue greater than 1).

The variance extracted by each of the two retained factors is higher in the analysis conducted on the polychoric correlation matrix compared to the analyses on the Pearson or Spearman correlation matrices (59.9% vs. 53.3% vs. 51.7%, respectively, for the first factor F1; the differences for the second factor F2 are even smaller). Similarly, the factor loadings for each factor are higher when using the polychoric correlations, followed by Pearson’s and then Spearman’s correlations. These differences, often to the second decimal place, are visually depicted in

Figure 2, highlighting their significance.

3.2. Case Study 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Items with 5 Points

Case study two involves confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the USEI, a psychometric inventory assessing academic engagement. Comprising 15 ordinal items, the USEI’s response categories range from “1-Never” to “5-Always” (Maroco, Maroco, Bonini Campos, & Fredricks, 2016). It conceptualizes academic involvement as a second-order hierarchical structure, with three first-order factors: Behavioral, Emotional, and Cognitive engagement, each consisting of five ordinal items (Maroco et al., 2016). Although most items exhibit slight leftward skewness, observed skewness (sk) and kurtosis (ku) values do not indicate severe departures from normal distribution (Marôco, 2021b).

Using the R software and the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012), CFA can be conducted employing various correlation matrices and appropriate estimators based on the measurement scales of observed variables. The recommended estimators include maximum likelihood for normally distributed, at least interval-scale items, or WLSMV/DWLS for ordinal items with underlying bivariate normal latents (Finney et al., 2016). Traditional CFA, utilizing the covariance matrix and maximum likelihood estimation of the model described in equation (11), can be executed with the lavaan library in R using the Pearson correlation matrix (see supplementary material for R code). To perform CFA on the polychoric correlation matrix, ordinal item specification with the ordered keyword is necessary (by default, lavaan utilizes the DWLS estimator).

Table 3 summarizes the primary outcomes of these two analyses. Both models exhibit good fit, whether using the traditional method (maximum likelihood on the covariance matrix) or the more recent method (DWLS on the polychoric correlation matrix). All items display standardized factor loadings exceeding the typical cutoff value in factor analysis (λ ≥ 0.5). Differences in factor loading estimates are minimal, mostly favoring the DWLS method on the polychoric correlation matrix.

3.3. Case Study 3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Items - Artificial Results?

The case studies thus far suggest an advantage in conducting either exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal items using the polychoric correlation matrix over Pearson’s correlation. However, it’s crucial to note that the observed differences in standardized factor loadings between the two methods are typically minimal, only affecting the second decimal place of estimates, and do not significantly alter the researcher’s conclusions regarding the underlying factor structure. Additionally, as highlighted by Finney et al. (2016), while the results with ML and DWLS estimators are promising, there remains uncertainty about their performance with ordinal items exhibiting varying numbers of categories and distributions.

To further illustrate this uncertainty, a case study of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) with 25 ordinal items and 6 categories each is presented (Saur et al., 2016). Descriptive statistics for the PBQ items are provided (see supplementary material). Employing the lavaan package, CFA was conducted on both the Pearson correlation matrix with ML and the Polychoric correlation matrix with DWLS estimation. The results, summarized in

Table 4, indicate notable differences favoring the analysis of the polychoric correlation matrix with DWLS.

In this case study, contrary to the previous ones, the differences in standardized factor loadings, now extending to the first decimal place, significantly favor the analysis of the polychoric correlation matrix with DWLS. While ML analysis on the covariance matrix yields standardized weights mostly below 0.5, DWLS analysis on the polychoric correlation matrix results in higher factor loadings. Consequently, the goodness of fit for the tetra-factorial model obtained with DWLS on the polychoric correlation matrix is substantially better than that obtained with ML on the Pearson covariance matrix. Specifically, using DWLS on the polychoric correlation matrix, the model fit is deemed good, whereas ML on the covariance matrix yields a relatively poor fit.

The apparent superiority of CFA estimates derived from polychoric correlations compared to those from Pearson’s covariance/correlation matrix is evident. However, the reliability of these polychoric correlation-based estimates relative to those from the Pearson correlation matrix warrants scrutiny. Particularly in Case Study 3, where items exhibit significant asymmetry, it raises questions about the accuracy of these estimates.

To address this, a simulation study using various levels of skewness and kurtosis for 5-point ordinal variables with known factor structures can provide valuable insights. By comparing the performance of CFA estimates derived from polychoric correlations with those from Pearson’s correlation matrix under different data conditions, we can evaluate the robustness and reliability of the former approach.

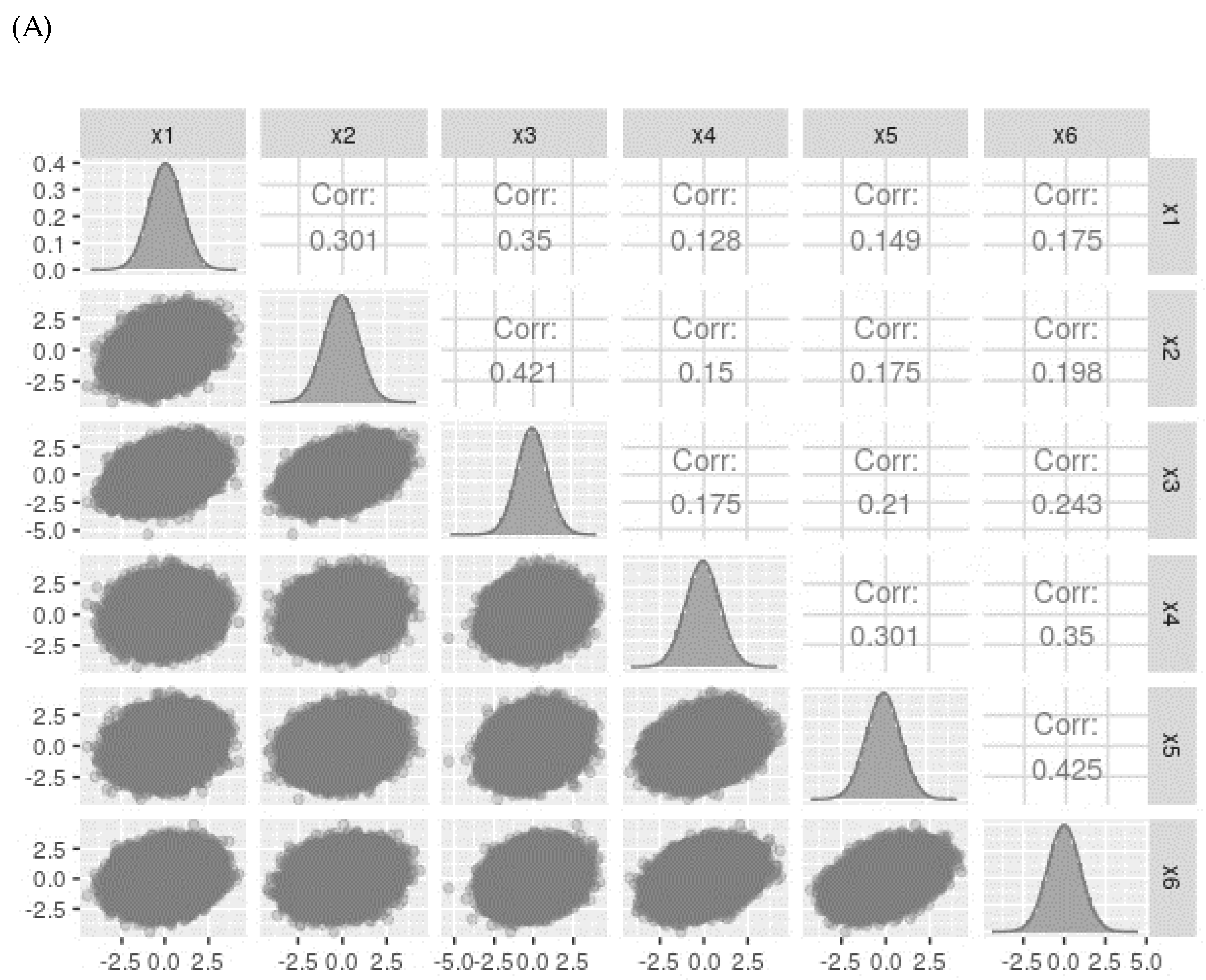

4. Simulation Studies

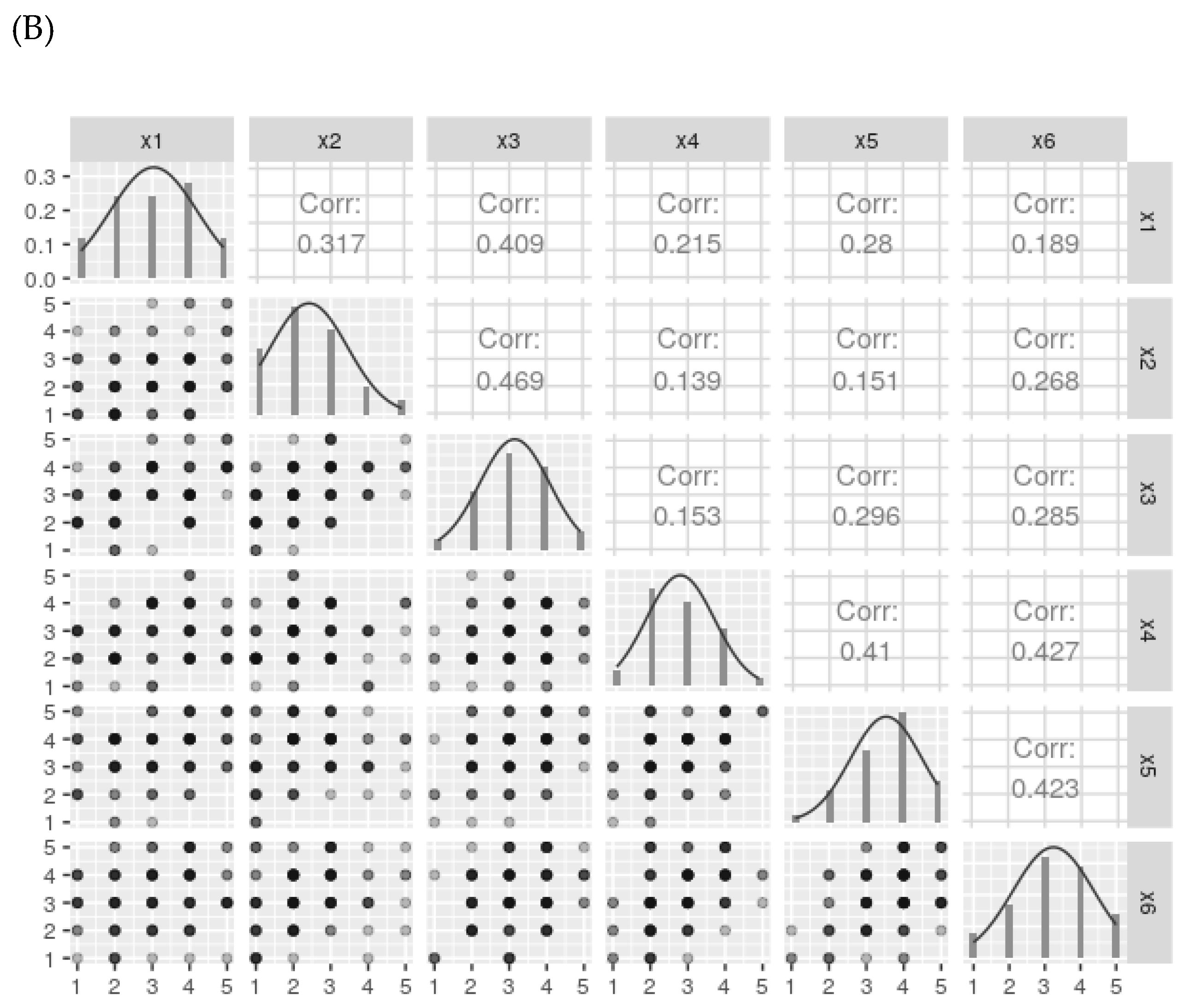

Let’s consider a two-factor population model with three items each (see supplementary material), where the standardized factor loadings are 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7 for each item, and a correlation of 0.5 between the two factors. Using the lavaan package, we can generate one million standardized data observations with skewness and kurtosis values of 0. The descriptive statistics and correlations of the generated items are shown in

Figure 3A, indicating normal distribution with small to moderate observed Pearson correlations between the items.

Assuming the ordinal items result from discretizing latent continuous variables into a given number of categories (ncat = 5, 7, and 9), the continuous variables generated previously can be discretized accordingly. The categorized data is depicted in

Figure 3B.

Subsequent simulations were conducted under two scenarios: (i) Symmetrical (normal) ordinal variables with 5, 7, and 9 categories; (ii) Biased (non-symmetrical) ordinal data generated from biased continuous variables; and (iii) Biased (non-symmetrical) variables obtained by biased sampling from ordinal symmetrical variables.

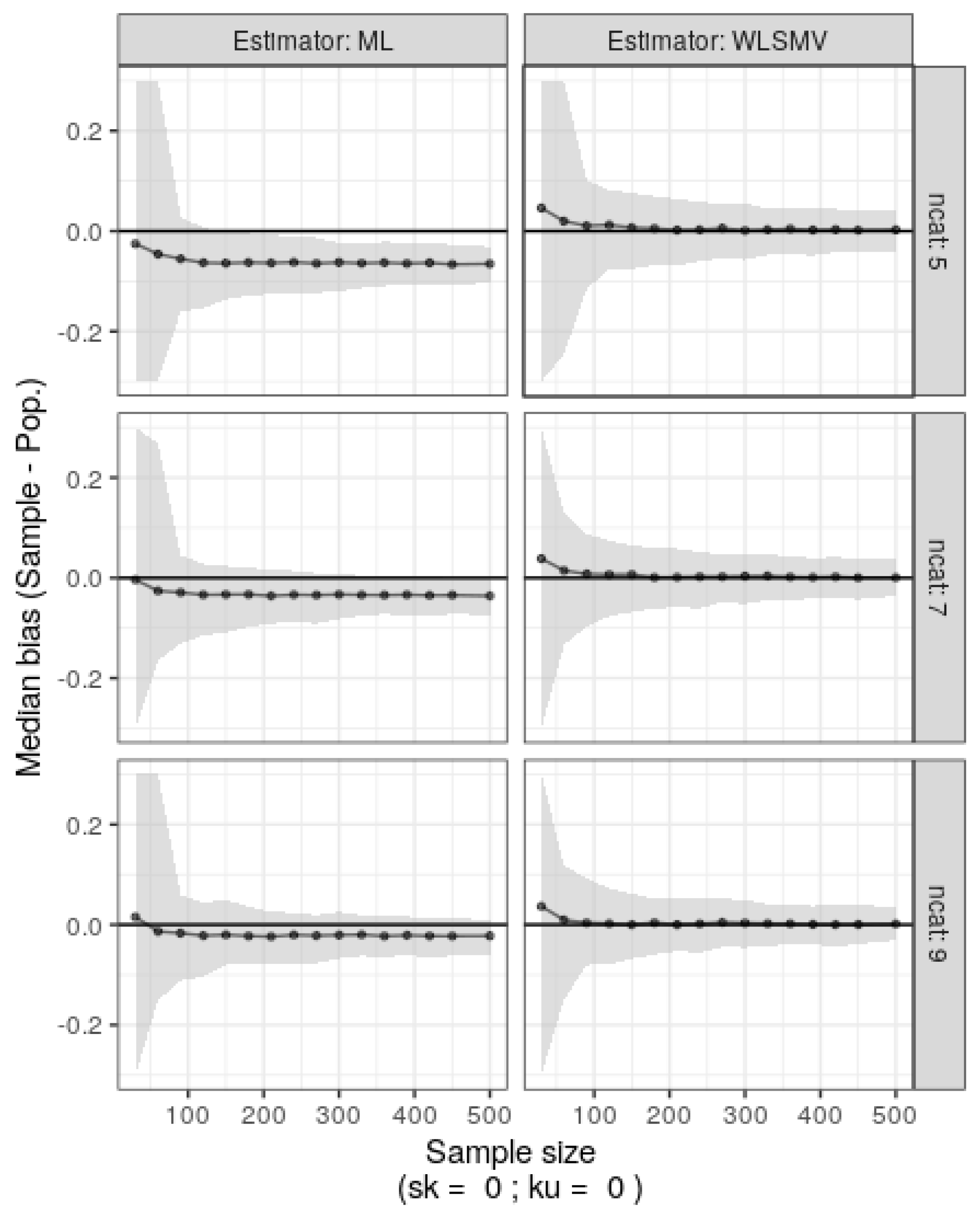

4.1. Simulation 1. Symmetrical Ordinal Data Generated from Normal Continuous Data

A model was created with R-lavaan to fit the two-factor population data. It was then applied using DWLS or ML to data sampled with replacement from the original ordinal generated data with sample sizes ranging from 30 to 500 and 500 bootstrap replicates. Results in

Figure 4 show that ML on Pearson correlations for ordinal items consistently underestimated true population factor loadings. This underestimation increased with fewer categories (from 9 to 5). Conversely, DWLS estimation quickly converged to true population factor loadings, unaffected by the number of categories, even for small sample sizes.

4.2. Simulation 2. Asymmetrical Ordinal Data Generated from Non-Normal Continuous Data

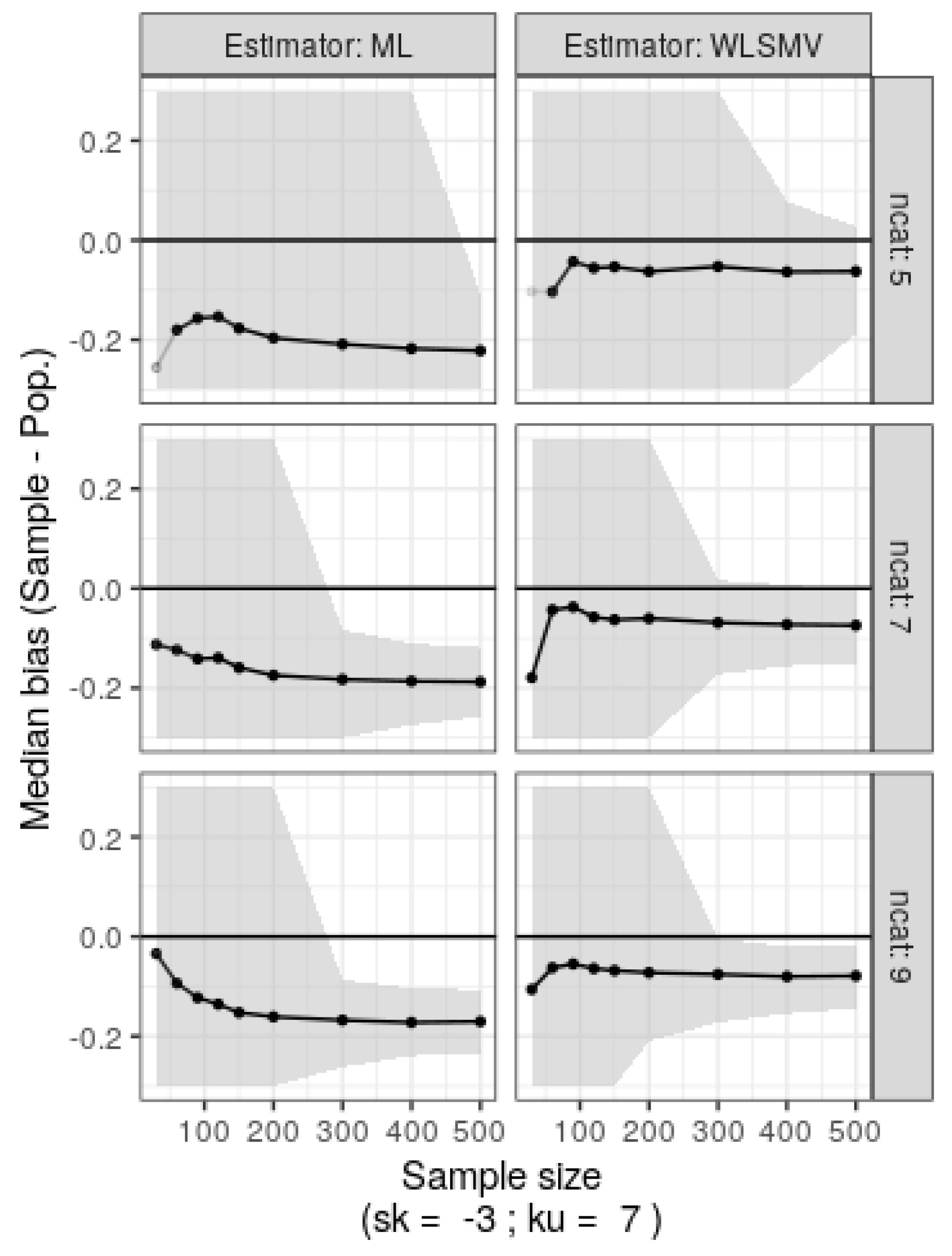

Simulation two mirrored simulation one, except the original data was skewed and leptokurtic (sk=-3, ku=7). Results from 500 bootstrap replicates are shown in

Figure 5. ML and DWLS yielded biased estimates, with ML notably poor for 5-category ordinal variables. DWLS showed resilience to category count, converging even with small sample sizes in SEM (n=100-150), albeit with noticeable bias.

Figure 5.

Median bias (population – sample) estimates for factor loadings and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded) derived from 500 bootstrap samples of the original skewed ordinal data with varying category counts (ncat: 5, 7, or 9) and sample sizes (30 to 500).

Figure 5.

Median bias (population – sample) estimates for factor loadings and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded) derived from 500 bootstrap samples of the original skewed ordinal data with varying category counts (ncat: 5, 7, or 9) and sample sizes (30 to 500).

4.3. Simulation 3. Asymmetrical Ordinal Data Generated from Biased Sampling of Normal Ordinal Data

Simulation three explores biased responses stemming from non-random sampling practices prevalent in psychological and social sciences research. Despite a normative population exhibiting a normal distribution, non-random sampling and respondent bias lead to highly asymmetrical data. Only biased responses from the original population (N=10

6) were sampled. As shown in

Figure 6, with data from biased items featuring 7 categories, ML consistently underestimates the true population factor loadings. Surprisingly, DWLS exhibits an opposite trend, overestimating the true population factor loadings. This contrasts with the asymmetrical data generated in simulation 2.

5. Discussion

The simulation and case studies demonstrate that polychoric correlation coefficients tend to be higher than Pearson and Spearman coefficients, indicating their robustness in estimating latent variables. Polychoric correlations are derived from the normal distribution of latent variables, making them less susceptible to measurement errors. Consequently, factor loadings extracted from the polychoric correlation matrix are higher, supporting consistent theoretical interpretations, even with small sample sizes. Despite this, relying solely on polychoric correlations and weighted least squares methods for factor analysis with ordinal variables and few categories may not be justifiable.

In case study 1 and 2, both Pearson’s ML estimation and polychoric DWLS estimation produced similar results, with negligible differences in standardized factor loadings, supporting consistent interpretations of factor validity. However, case study 3 revealed substantial disparities between estimates obtained from Pearson correlations with ML estimation and polychoric correlations with DWLS estimation. The latter yielded substantially higher factor loadings, leading to conflicting conclusions regarding factorial validity.

Moreover, simulation study 3 highlighted the unreliability of polychoric correlations with DWLS under biased data conditions. ML estimation on Pearson correlations consistently underestimated true population parameters, while DWLS on polychoric correlations overestimated them, particularly evident in biased data scenarios.

The inadequacy of least squares weighted methods with polychoric correlation matrices has also been reported, both under conditions of moderate (Li, 2015; 2016) and severe non-normality (Foldnes & Grønneberg, 2020). Recommendations for method selection based on category counts exist, but our findings suggest that methodological differences are minor under sensible data conditions but significant under strongly biased scenarios. Blind reliance on polychoric correlations with weighted least squares estimates may yield misleading conclusions about factor structure validity and reliability.

6. Concluding Remarks

Method selection should consider data characteristics, with sensitivity analyses imperative, especially under biased conditions. Blind reliance on polychoric correlations with weighted least squares estimates may yield misleading conclusions about factor structure validity and reliability. Further research and sensitivity analyses are essential to ensure robust psychometric evaluations. These findings contribute to ongoing discussions about the appropriate use of correlation matrices and estimation methods in factor analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this per posted on Preprints.org

Notes

| 1 |

For an extensive account of the development of factor analysis see, e.g. Bartholomew (2007). |

| 2 |

The system has p(p+1)/2 known quantities and (m+1)p (matrix mp and p vector quantities with m<< p). |

| 3 |

For a more detailed description see e.g. (Jöreskog, 2007) |

References

- Arbuckle, J. (2006). Amos (Version 4.0) [Computer Software]. Babakus, E., Ferguson, C. E., & Joreskog, K. G. (1987). The Sensitivity of Confirmatory Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis to Violations of Measurement Scale and Distributional Assumptions. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(2), 222–228. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D. J. (2007). Three faces of factor analysis. Em Factor analysis at 100: Historical developments and future directions. (pp. 9–21). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cattell, R. B. (1943). The measurement of adult intelligence. Psychological Bulletin, 40(3), 153–193. [CrossRef]

- Drasgow, F. (1986). Polychoric and polyserial correlations. Em Kotz Samuel, N. Balakrishnan, C. B. Read, B. Vidakovic, & N. L. Johnson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences (pp. 68–74). John Wiley & Sons.

- Ekström, J. (2011). A generalized definition of the polychoric correlation coefficient. Department of Statistics, UCLA, 1–24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/583610fv.

- Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G.R. Hancock & R.O. Mueller (Eds.). A second course in structural equation modeling (2nd ed.,).

- Finney, S. J, DiStefano, C., & Kopp, J. P. (2016a). Overview of estimation methods and preconditions for their application with structural equation modeling. Em K. Schweizer & C. DiStefano (Eds.), Principles and methods of test construction: Standards and recent advances (pp. 135–165). Hogrefe Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Finney, S. J, DiStefano, C., & Kopp, J. P. (2016b). Overview of estimation methods and preconditions for their application with structural equation modeling. Em K. Schweizer & C. DiStefano (Eds.), Principles and methods of test construction: Standards and recent advances (pp. 135–165). Hogrefe Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Foldnes, N., & Grønneberg, S. (2020). Pernicious Polychorics: The Impact and Detection of Underlying Non-normality. Structural Equation Modeling, 27(4), 525–543. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. (2016). polycor: Polychoric and Polyserial Correlations. R package version 0.7-9. https://cran.r-project.org/package=polycor.

- Holgado-Tello, F. P., Chacón-Moscoso, S., Barbero-García, I., & Vila-Abad, E. (2009). Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Quality and Quantity, 44(1), 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, S. (2004). Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Medical Education, 38(12), 1217–1218. [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1994). On the estimation of polychoric correlations and their asymptotic covariance matrix. Psychometrika, 59(3), 381–389. [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (2007). Factor analysis and its extensions. Em Factor analysis at 100: Historical developments and future directions. (pp. 47–77). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Lawley, D. N., & Maxwell, A. E. (1962). Factor Analysis as a Statistical Method. The Statistician, 12(3), 209. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H. (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res 48, 936–949 . [CrossRef]

- Li, C. H. (2016). The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 369–387. [CrossRef]

- Liddell, T. M., & Kruschke, J. K. (2018). Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79(August), 328–348. [CrossRef]

- Lord, F. M. (1953). On the statistical treatment of football numbers. American Psychologist, 8(12), 750–751. [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações (2nd ed.). Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal: ReportNumber.

- Marôco, J. (2021). Análise de Equações Estruturais, Fundamentos teóricos, Software & Aplicações (3.a). ReportNumber. www.reportnumber.pt/aee.

- Maroco, J., Maroco, A. L., Bonini Campos, J. A. D., & Fredricks, J. A. (2016). University student’s engagement: Development of the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI). Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica, 29(1). [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B. (1984). A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika, 49(1), 115–132.

- Olsson, U. (1979a). On the robustness of factor analysis against crude classification of the observations. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 14(4), 485–500. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, U. (1979b). Maximum likelihood estimation of the polychoric correlation coefficient. Psychometrika, 44(4), 443–460. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. (1900). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution. Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 191, 241–244. http://ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyhref&AN=TRSL.AIA.BEI.PEARSON.MCTE&site=ehost-live.

- Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E. E., & Ferguson, C. E. (2006). The Performance of the Polychoric Correlation Coefficient and Selected Fitting Functions in Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Ordinal Data. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(4), 491. [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A. (2020). Why Ordinal Variables Can (Almost) Always Be Treated as Continuous Variables: Clarifying Assumptions of Robust Continuous and Ordinal Factor Analysis Estimation Methods. Frontiers in Education, 0, 177. [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Saur, A. M., Sinval, J., Marôco, J. P., & Bettiol, H. (2016). Psychometric Properties of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire for Brazil: Preliminary Data. 10th International Test Comission Conference.

- Spearman, C. (1904a). The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 72. [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. (1904b). "General Intelligence," Objectively Determined and Measured. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 201. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the theory of scales of measurement. Science (New York, N.Y.), 103(2684), 677–680. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G. H. (1916). A Hierarchy Without a General Factor. British Journal of Psychology, 1904-1920, 8(3), 271–281. [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L. L. (1938). Primary mental abilities. Univ. of Chicago Press. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/2471740.html.

- Velleman, P. F., & Wilkinson, L. (1993). Nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio typologies are misleading. American Statistician, 47(1), 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Yang-Wallentin, F., Jöreskog, K. G., & Luo, H. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(3), 392–423. [CrossRef]

- Yung, Y. -F, & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Bootstrap-corrected ADF test statistics in covariance structure analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 47(1), 63–84. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Illustration of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) (a) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (b) models with 6 observed variables (x1, …, x6), two latent variables (f1 and f2), and specific factors (e1, …, e6). Factor loadings are denoted by λ. Constraints on factor loadings or latent variances are omitted for simplicity.

Figure 1.

Illustration of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) (a) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (b) models with 6 observed variables (x1, …, x6), two latent variables (f1 and f2), and specific factors (e1, …, e6). Factor loadings are denoted by λ. Constraints on factor loadings or latent variances are omitted for simplicity.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the two extracted factor loadings on Complex, WithoutVoice, Contact, Departures, and Desinter with exploratory factor analysis on Pearson’s (○), Spearman’s (◊) and the polychoric (☐) correlation matrixes.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the two extracted factor loadings on Complex, WithoutVoice, Contact, Departures, and Desinter with exploratory factor analysis on Pearson’s (○), Spearman’s (◊) and the polychoric (☐) correlation matrixes.

Figure 3.

Data distribution for continuous (A) and categorized (B) variables generated with the model described in

Figure 5. For simplicity, only the ncat= 5 categories variables are presented. Note that for normally distributed data, Pearson correlations are similar for both continuous and 5-categories categorized variables.

Figure 3.

Data distribution for continuous (A) and categorized (B) variables generated with the model described in

Figure 5. For simplicity, only the ncat= 5 categories variables are presented. Note that for normally distributed data, Pearson correlations are similar for both continuous and 5-categories categorized variables.

Figure 4.

Median bias estimates for factor loadings and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) were calculated from 500 bootstrap samples from the original symmetrical ordinal generated data. This was done with different numbers of categories (ncat: 5, 7, or 9) and sample sizes ranging from 30 to 500.

Figure 4.

Median bias estimates for factor loadings and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) were calculated from 500 bootstrap samples from the original symmetrical ordinal generated data. This was done with different numbers of categories (ncat: 5, 7, or 9) and sample sizes ranging from 30 to 500.

Figure 6.

Median bias in factor loading estimates (population – sample) and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) derived from 500 bootstrap samples of the biased ordinal data with 7 categories and varying sample sizes (30 to 500).

Figure 6.

Median bias in factor loading estimates (population – sample) and nonparametric 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) derived from 500 bootstrap samples of the biased ordinal data with 7 categories and varying sample sizes (30 to 500).

Table 1.

Pearson (A), Spearman(B) correlation matrixes obtained with SPSS Statistics, and Polychoric correlation (C) matrix obtained with polycor (v. 0.7-9) package. All p-values for the bivariate normality tests were larger than 0.10.

Table 1.

Pearson (A), Spearman(B) correlation matrixes obtained with SPSS Statistics, and Polychoric correlation (C) matrix obtained with polycor (v. 0.7-9) package. All p-values for the bivariate normality tests were larger than 0.10.

| (A) Correlation types and Correlation Coefficients

|

| |

WithoutVoice |

Complex |

Desinter |

Contact |

Parties |

| WithoutVoice |

1 |

Pearson |

Pearson |

Pearson |

Pearson |

| Complex |

0.829 |

1 |

Pearson |

Pearson |

Pearson |

| Desinter |

0.338 |

0.0523 |

1 |

Pearson |

Pearson |

| Contact |

0.386 |

0.288 |

0.655 |

1 |

Pearson |

| Parties |

0.268 |

0.196 |

0.473 |

0.628 |

1 |

| (B) Correlation types and Correlation Coefficients

|

|

| |

WithoutVoice |

Complex |

Desinter |

Contact |

Parties |

|

| WithoutVoice |

1 |

Spearman |

Spearman |

Spearman |

Spearman |

|

| Complex |

0.828 |

1 |

Spearman |

Spearman |

Spearman |

|

| Desinter |

0.310 |

0.0156 |

1 |

Spearman |

Spearman |

|

| Contact |

0.377 |

0.283 |

0.661 |

1 |

Spearman |

|

| Parties |

0.234 |

0.150 |

0.458 |

0.588 |

1 |

|

| (C) Correlation types and Correlation Coefficients

|

|

| |

WithoutVoice |

Complex |

Desinter |

Contact |

Parties |

|

| WithoutVoice |

1 |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

|

| Complex |

0.932 |

1 |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

|

| Desinter |

0.386 |

0.0601 |

1 |

Polychoric |

Polychoric |

|

| Contact |

0.495 |

0.345 |

0.783 |

1 |

Polychoric |

|

| Parties |

0.333 |

0.228 |

0.599 |

0.753 |

1 |

|

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the exploratory factor analyses with the extraction of Principal Components with Varimax Rotation performed on the Pearson, Spearman, and Polychoric correlation matrixes.

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the exploratory factor analyses with the extraction of Principal Components with Varimax Rotation performed on the Pearson, Spearman, and Polychoric correlation matrixes.

| Items |

Pearson Correlation |

Spearman Correlation |

Polychoric Correlation |

| Factor loadings |

| F1 |

F2 |

F1 |

F2 |

F1 |

F2 |

| WithoutVoice |

.256 |

.918 |

.242 |

.921 |

.292 |

.939 |

| Complex |

.048 |

.968 |

.027 |

.969 |

.056 |

.994 |

| Desinter |

.849 |

.049 |

.857 |

.030 |

.901 |

.052 |

| Contact |

.867 |

.235 |

.859 |

.248 |

.903 |

.283 |

| Parties |

.801 |

.123 |

.787 |

.092 |

.849 |

.146 |

| Extracted Variance (%) |

53.3 |

27.4 |

51.7 |

28.5 |

59.9 |

28.2 |

Table 3.

Standardized factor weights (λ) for the USEI second order hierarchical model estimated with the ML method on the Pearson correlation matrix (χ2(87)=241.22, CFI=0.945, TLI=0.933, RMSEA=0.054 with IC90% ]0.046; 0.062[) vs. DWLS method on the matrix of polychoric correlations (χ 2(87)=172.249, CFI=0.994, TLI=0.993, rmsea=0.040 with IC90% ]0.031; 0.049[) using the lavaan package.

Table 3.

Standardized factor weights (λ) for the USEI second order hierarchical model estimated with the ML method on the Pearson correlation matrix (χ2(87)=241.22, CFI=0.945, TLI=0.933, RMSEA=0.054 with IC90% ]0.046; 0.062[) vs. DWLS method on the matrix of polychoric correlations (χ 2(87)=172.249, CFI=0.994, TLI=0.993, rmsea=0.040 with IC90% ]0.031; 0.049[) using the lavaan package.

| Factor |

Items |

AFC on the Pearson Correlation matrix with ML |

AFC on Polychoric correlation Matrix with DWLS |

Difference |

| ML

|

p |

DWLS

|

p |

ML -DWLS

|

| Ecp |

ECP1 |

0.582 |

0.018 |

0.654 |

0.007 |

-0.072 |

| |

ECP3 |

0.431 |

0.020 |

0.474 |

0.008 |

-0.043 |

| |

ECP4 |

0.530 |

0.018 |

0.559 |

0.007 |

-0.029 |

| |

ECP5 |

0.574 |

0.018 |

0.624 |

0.007 |

-0.050 |

| |

ECP6 |

0.555 |

0.018 |

0.664 |

0.009 |

-0.109 |

| EAt |

EE14r |

0.480 |

<.001 |

0.513 |

<.001 |

-0.033 |

| |

EE15 |

0.794 |

<.001 |

0.845 |

<.001 |

-0.051 |

| |

EE16 |

0.778 |

<.001 |

0.812 |

<.001 |

-0.034 |

| |

EE17 |

0.878 |

<.001 |

0.935 |

<.001 |

-0.057 |

| |

EE19 |

0.662 |

<.001 |

0.722 |

<.001 |

-0.060 |

| ECn |

ECC22 |

0.537 |

<.001 |

0.596 |

<.001 |

-0.059 |

| |

ECC25 |

0.484 |

<.001 |

0.557 |

<.001 |

-0.073 |

| |

ECC26 |

0.614 |

<.001 |

0.670 |

<.001 |

-0.056 |

| |

ECC28 |

0.769 |

<.001 |

0.848 |

<.001 |

-0.079 |

| |

ECC32 |

0.698 |

<.001 |

0.749 |

<.001 |

-0.051 |

| ENG |

ECp |

0.948 |

<.001 |

0.947 |

0.014 |

0.001 |

| |

EAt |

0.646 |

<.001 |

0.662 |

<.001 |

-0.016 |

| |

ECn |

0.726 |

<.001 |

0.726 |

<.001 |

0.000 |

Table 4.

Standardized Factor Weights (λ) for the tetrafatorial model of the PBQ estimated with the maximum likelihood (ML) method on the Pearson correlation matrix (χ2(269)=2838.41, CFI=0.670, TLI=0.632, RMSEA=0.067 with IC90% ]0.064; 0.069[) and with DWLS method on the matrix of polychoric correlations (χ2(87)=172.249, CFI=0.994, TLI=0.993, rmsea=0.040 with IC90% ]0.031; 0.049[) using the lavaan package.

Table 4.

Standardized Factor Weights (λ) for the tetrafatorial model of the PBQ estimated with the maximum likelihood (ML) method on the Pearson correlation matrix (χ2(269)=2838.41, CFI=0.670, TLI=0.632, RMSEA=0.067 with IC90% ]0.064; 0.069[) and with DWLS method on the matrix of polychoric correlations (χ2(87)=172.249, CFI=0.994, TLI=0.993, rmsea=0.040 with IC90% ]0.031; 0.049[) using the lavaan package.

| Factor |

Items |

AFC in Cov matrix with ML |

AFC in Poly matrix with WLSMV |

Difference |

| ML

|

p |

WLSMV

|

p |

ML -WLSMV

|

| F1 |

PBQ.1 |

0.346 |

<0.001 |

0.542 |

<0.001 |

-0.196 |

| |

PBQ.2.Inv |

0.431 |

<0.001 |

0.536 |

<0.001 |

-0.105 |

| |

PBQ.6.Inv |

0.238 |

<0.001 |

0.43 |

<0.001 |

-0.192 |

| |

PBQ.7.Inv |

0.418 |

<0.001 |

0.481 |

<0.001 |

-0.063 |

| |

PBQ.8 |

0.254 |

<0.001 |

0.623 |

<0.001 |

-0.369 |

| |

PBQ.9 |

0.246 |

<0.001 |

0.635 |

<0.001 |

-0.389 |

| |

PBQ.10.Inv |

0.541 |

<0.001 |

0.593 |

<0.001 |

-0.052 |

| |

PBQ.12.Inv |

0.378 |

<0.001 |

0.403 |

<0.001 |

-0.025 |

| |

PBQ.13.Inv |

0.584 |

<0.001 |

0.662 |

<0.001 |

-0.078 |

| |

PBQ.15.Inv |

0.24 |

<0.001 |

0.587 |

<0.001 |

-0.347 |

| |

PBQ.16 |

0.256 |

<0.001 |

0.547 |

<0.001 |

-0.291 |

| |

PBQ.17.Inv |

0.185 |

<0.001 |

0.567 |

<0.001 |

-0.382 |

| F2 |

PBQ.3.Inv |

0.346 |

<0.001 |

0.499 |

<0.001 |

-0.153 |

| |

PBQ.4 |

0.367 |

<0.001 |

0.638 |

<0.001 |

-0.271 |

| |

PBQ.5.Inv |

0.398 |

<0.001 |

0.691 |

<0.001 |

-0.293 |

| |

PBQ.11 |

0.446 |

<0.001 |

0.636 |

<0.001 |

-0.19 |

| |

PBQ.14.Inv |

0.609 |

<0.001 |

0.682 |

<0.001 |

-0.073 |

| |

PBQ.21.Inv |

0.614 |

<0.001 |

0.692 |

<0.001 |

-0.078 |

| |

PBQ.23.Inv |

0.32 |

<0.001 |

0.519 |

<0.001 |

-0.199 |

| F3 |

PBQ.19.Inv |

0.429 |

<0.001 |

0.504 |

<0.001 |

-0.075 |

| |

PBQ.20.Inv |

0.348 |

<0.001 |

0.601 |

<0.001 |

-0.253 |

| |

PBQ.22 |

0.378 |

<0.001 |

0.629 |

<0.001 |

-0.251 |

| |

PBQ.25 |

0.358 |

<0.001 |

0.464 |

<0.001 |

-0.106 |

| F4 |

PBQ.18.Inv |

0.411 |

<0.001 |

0.622 |

<0.001 |

-0.211 |

| |

PBQ.24.Inv |

0.396 |

<0.001 |

0.82 |

<0.001 |

-0.424 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).