Introduction

Adaptive immune responses directed against cancer epitopes can significantly influence clinical outcomes, contributing to tumor control and response to immunotherapies. Cancer epitopes encompass a wide range of antigen classes, including mutated gene products, overexpressed proteins, cancer germline antigens, cell-type–specific differentiation antigens, oncoviral proteins, and altered glycolipids and glycoproteins [

1,

2]. Both B cells and T cells participate in the recognition of such epitopes: B cells bind conformational epitopes on surface or secreted antigens, while T cells recognize peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Among these classes, mutation-derived neoepitopes have emerged as especially significant [

3]. Because they are encoded by somatic mutations and absent from healthy tissues, neoepitopes are less subject to central tolerance and more likely to elicit robust immune responses [

4]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) now allows comprehensive identification of tumor mutations, yielding hundreds of potential neoepitope candidates in highly mutated cancers [

4,

5]. Yet, only a small fraction of these candidates are processed, presented, and immunogenic in vivo [

6,

7]. Identifying the relevant subset requires specialized computational methods.

Traditional epitope prediction algorithms were initially developed in the context of infectious diseases, yet many have proven broadly applicable to cancer immunology research [

7,

8]. In recent years, new tools and pipelines have emerged that explicitly incorporate cancer-specific variables, including tumor heterogeneity, immune tolerance, and antigen abundance [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The development of such cancer-adapted tools critically depends on the availability of curated datasets that include experimentally validated cancer epitopes. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB, iedb.org) has long served as a central resource for epitope data across infectious disease, allergy, and autoimmunity, providing the foundation for many of the prediction tools in use today [

14,

15]. The Cancer Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (CEDAR, cedar.iedb.org) was established to address the specific needs of the cancer immunology community, systematically cataloging T and B cell responses to cancer antigens from thousands of studies published in the literature [

14,

16,

17].

As part of CEDAR, novel cancer-specific tools have been developed and integrated with existing prediction algorithms into modular pipelines. This feature enables cancer researchers to address key questions such as identifying neoepitopes from somatic mutations, comparing mutant and wild-type peptide binding, and estimating antigen abundance from public expression datasets. These tools are available on the redesigned Next-Generation IEDB Tools platform (NGT, nextgen-tools.iedb.org/), which provides a unified interface for epitope prediction, modular tool integration, and reproducible pipelines [

18].

Here, we present the design and functionality of these tools, describe their core methodologies, provide guidance for their use, and illustrate how they can be integrated into end-to-end pipelines. We highlight key applications in cancer immunology research, such as the prioritization of shared, overexpressed epitopes, and in personalized cancer immunotherapy, including neoepitope discovery from NGS data. These use cases are supported by case scenarios that demonstrate how to effectively apply the tools in practice.

Results

While several tools within NGT were originally developed for epitope prediction in infectious, allergic and autoimmune diseases, many have proven to be broadly applicable in cancer immunology research. In particular, the T Cell prediction tools for class I and class II remain foundational components of cancer epitope prioritization pipelines [

19]. These tools leverage extensively benchmarked MHC binding prediction models, such as NetMHCpan [

20], MHCFlurry [

20,

21], and other related algorithms, to estimate peptide–MHC affinity across diverse Human Leukocyte Antigen (MHC) alleles. Although they do not incorporate cancer-specific features, their high predictive performance for binding makes them suitable for filtering large candidate sets derived from tumor variants or overexpressed self-antigens.

Building upon these core functionalities, NGT features a dedicated set of cancer-specific tools developed under the CEDAR program. These tools are tailored to address unique aspects of tumor immunology, including the handling of somatic variants, antigen expression, and patient-specific MHC contexts [

22]. Many of these tools integrate additional layers of data, such as peptide abundance estimates or mutation-specific immunogenicity models. To help users identify and access these resources, the NGT platform provides intuitive navigation features; tools associated with cancer applications are annotated with searchable tags such as “cancer” and “neoepitope.”

Furthermore, a number of additional legacy tools remain available on the original IEDB Analysis Resource (AR, tools.iedb.org) site and continue to support cancer epitope prediction workflows [

23]. These include tools for TCR specificity prediction (TCRMatch), peptide synthesis prediction (PepSySco), and MHC binding predictions integrated with antigen abundance (AXEL-F) [

11,

24,

25]. These tools are in active use and will be incrementally integrated into the NGT platform over the coming years. This planned migration will ensure that the full breadth of IEDB’s analytical capabilities is accessible through a unified, modernized interface that supports end-to-end pipeline construction.

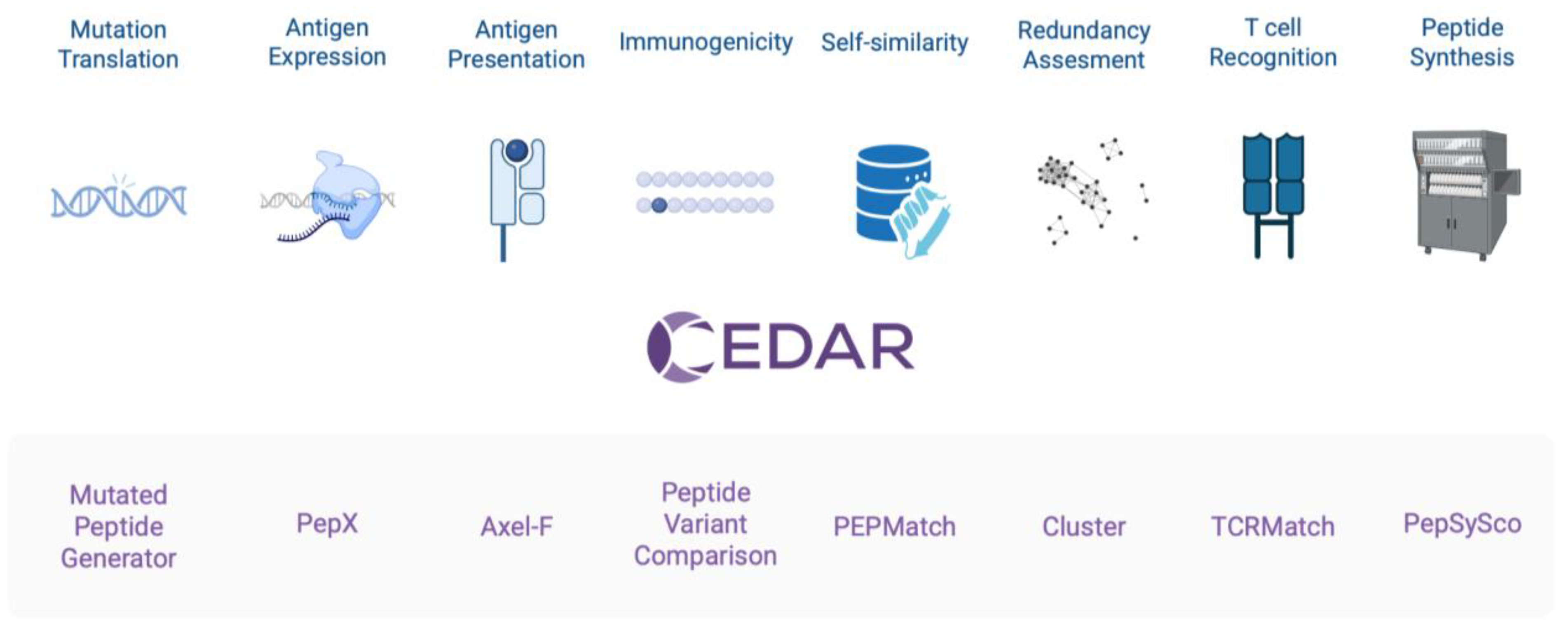

Below, we provide an overview of each tool, focusing on its relevance to cancer epitope analysis (

Figure 1). These tools can be used individually or integrated into pipeline workflows, depending on the user’s study design.

Mutated Peptide Generator (MPG)

MPG is designed to translate somatic variants into peptide sequences. It supports single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), multinucleotide variants (MNVs), insertions and deletions (InDels), and generates peptides that span the mutation site. The tool is particularly useful for identifying candidate neoepitopes from tumor variant datasets and can be integrated into larger prediction pipelines. By preserving alignment between wild-type and mutant peptides, MPG facilitates side-by-side comparison of their immunological properties.

MPG accepts variant call format (VCFs) files as input and uses SnpEff for variant annotation to determine coding consequences, affected transcripts, and resulting amino acid changes [

26]. Users can specify peptide length, mutation position within the peptide, and overlap length for frameshift-derived sequences. To ensure consistent and accurate peptide generation, users are encouraged to normalize and decompose their VCFs before annotation. The tool accepts pre-annotated VCFs or can perform SnpEff annotation internally.

The output includes three structured tables that capture the mapping from variant to peptide at varying levels of resolution. The Variant Table provides one row per variant with detailed annotations. The Peptide Table includes one row per variant–transcript pair, listing all derived peptides and reflecting transcript-specific effects. The Unique Peptide Table collapses redundant sequences across transcripts and selects a representative transcript for each unique peptide. All outputs include metadata such as genomic coordinates, coding context, mutation position, and peptide sequences, supporting their integration into downstream antigen presentation and immunogenicity prediction tools.

Peptide Expression Annotation (PepX)

PepX enables peptide-level expression annotation by estimating the abundance of source antigens using publicly available transcriptomic datasets derived from healthy and cancerous tissues [

27]. It is particularly valuable when patient-specific RNA-Seq data are not available, as it provides context-specific expression estimates from well-established reference cohorts.

The tool accepts peptide sequences as input and identifies all protein isoforms from which each peptide may originate. Users can select from multiple public RNA-Seq datasets, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [

28], Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) [

28,

29], Human Protein Atlas (HPA) [

30], and the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [

31]. Expression can be quantified using either gene-level or transcript-level TPM (transcripts per million) values. The transcript-level option offers higher resolution, particularly when a peptide is encoded by multiple isoforms with varying expression levels.

PepX produces two primary output tables. The Peptide Table summarizes total and median TPM values across all matched transcripts for each peptide, providing a quantitative estimate of peptide-level expression. The Gene Summary Table lists associated genes and transcripts, including gene symbols, Ensembl IDs, tissue-specific expression distributions, and the fraction of isoforms that encode the peptide. These results help refine candidate selection by prioritizing peptides that are consistently and abundantly expressed in relevant tissues or tumor types.

T Cell Prediction – Class I

The T Cell Prediction - Class I tool provides predictions for MHC class I antigen processing, presentation and CD8 T cell recognition, which serve as foundational components for epitope prioritization workflows across cancer and other disease contexts.

Users may submit one or more peptides ranging from 8 to 14 amino acids in length as input, or alternatively, provide full-length protein sequences or longer open reading frame segments. The tool automatically fragments long sequences into overlapping peptides of the selected lengths using a sliding-window. Predictions can be made across single alleles, custom allele panels, or representative MHC supertypes.

The tool supports three prediction types:

(1) MHC class I binding/elution predictions including NetMHCpan EL (eluted ligand), NetMHCpan BA (binding affinity) [

20], MHCflurry [

21], and IEDB Consensus [

32], among others. Predictions are reported as percentile ranks, and binding affinity methods also include binding affinity values (IC50, in nanomolar, nM). The percentile rank represents the predicted binding strength of a peptide relative to a background distribution of random natural peptides. This normalization avoids biases introduced by MHC alleles with inherently higher or lower predicted affinities. Peptides with lower ranks are more likely to be presented, with strong binders having scores ≤ 0.5 and weak binders < 2.0 [

33].

(2) Immunogenicity predictions [

34]. This model estimates the likelihood of T cell recognition based on amino acid enrichment weighted by position within the MHC class I presented peptide. Higher scores indicate a greater probability that the peptide will elicit an immune response.

(3) Antigen processing predictions using the IEDB Consensus [

32], NetCTL [

35], and its updated version NetCTLpan [

36]. These models estimate proteasomal cleavage, transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) transport efficiency, and MHC binding affinity and integrate these results into a single score. NetChop [

37], which predicts proteasomal cleavage sites, is included within NetCTL, but can also be executed alone. It scans protein sequences and assigns a score between 0 and 1 to each residue, with higher values indicating stronger cleavage preference.

Results are returned in tabular format with one row per peptide–allele pair, including the selected prediction methods, affinity estimates, and rank values. Notably, the T Cell Prediction – Class I tool supports multiple simultaneous predictions, enabling users to compare results across methods. This functionality allows for complex filtering and/or the prioritization of candidate epitopes based on consensus across predictive approaches. These predictions can be downloaded, filtered, or passed to downstream tools within the NGT pipeline framework.

T Cell Prediction – Class II

Similar to the T Cell Prediction - Class I tool, the T Cell Prediction - Class II provides predictions of MHC class II antigen processing, presentation and CD4 T cell recognition. These tools are designed to identify peptides likely to be presented on the cell surface of antigen presenting cells (APCs), enabling the filtering of candidate epitopes.

The tool accepts peptide sequences of at least 11 amino acids or entire protein sequences, which are automatically cleaved into the specified lengths. Predictions can be performed for individual MHC class II alleles, custom allele panels (e.g., a patient haplotype), or representative alleles (7-allele panel) [

38]. For DP and DQ molecules, both alpha and beta chains must be specified.

The tool supports three prediction types:

(1) MHC class II binding/elution predictions with NetMHCIIpan EL (recommended) and BA models [

39], the IEDB consensus [

32], and others. Predictions are reported as percentile ranks (see previous section), and BA methods also provide binding affinity values (IC50, in nanomolar, nM). Lower ranks indicate higher likelihood of presentation, with strong binders scoring ≤1 and weak binders <5.

(2) Immunogenicity predictions with the CD4Episcore model [

40]. This artificial neural network was trained on experimentally validated CD4 T cell epitopes and returns a score between 0 and 100, with lower values indicating a higher likelihood that the peptide will elicit an immune response.

(3) Antigen processing predictions with MHCII-NP [

41]. These are based on sequence motifs associated with natural cleavage patterns observed in mass spectrometry-identified MHC class II ligands. The method provides cleavage motifs, a cleavage score (with higher values indicating increased likelihood of natural processing), and a percentile rank.

Peptide Variant Comparison (PVC)

The PVC tool enables systematic evaluation of somatic mutations by comparing mutant and wild-type peptides side-by-side across multiple immunological prediction models. This approach is designed to assess whether a mutation enhances or reduces peptide presentation and immunogenicity, and is particularly relevant in neoepitope prioritization workflows.

As input, PVC accepts pairs of mutant and wild-type peptides, with the option to provide a single list of MHC alleles or specify an allele for each peptide pair. The tool supports three prediction types: (1) MHC class I antigen presentation using algorithms such as NetMHCpan and MHCFlurry, (2) general immunogenicity predictions [

34], and (3) neoepitope immunogenicity predictions using the ICORE-based prediction of neo-epitope immunogenicity (ICERFIRE) model [

9]. ICERFIRE identifies the minimal MHC class I presented peptide, referred to as the “Icore”, and calculates features such as mutation position, expression, antigen presentation, amino acid composition, and self-similarity to estimate the likelihood of T cell recognition. The output of this model is a prediction score ranging from 0 to 1, where values near 0 indicate low immunogenic potential and values near 1 suggest a higher likelihood of immunogenicity.

PVC outputs include side-by-side prediction scores for each peptide pair across all selected models, as well as the computed differences in scores between mutant and wild-type sequences. Visualizations are also generated in the form of scatterplots, allowing users to assess shifts in binding or immunogenicity in a graphical format. These results can be used to rank mutations and identify candidates for further experimental validation. PVC is only available for MHC class I predictions right now and will be expanded to class II.

PEPMatch

PEPMatch enables rapid identification of sequence-similar peptides across curated reference proteomes, supporting the evaluation of potential cross-reactivity in epitope discovery workflows [

42]. By identifying peptides with high sequence similarity to human proteins, PEPMatch aids in refining candidate selection based on predicted specificity and safety.

The tool accepts a list of input peptides and allows users to define the maximum number of amino acid substitutions permitted in the search. Peptide queries are scanned against selected UniProt proteomes, including human, mouse, and a variety of pathogenic organisms. Users can choose whether to return all matching sequences below the mismatch threshold or only the best match per peptide. The best match is determined by additional data such as SwissProt vs. TrEMBL status, protein existence level as curated by the UniProt team, and the match having the lowest number of amino acid substitutions.

The output consists of a tabular summary with one row per input–match pair, reporting the matched sequence, UniProt protein identifier, gene symbol, number of substitutions, and positions where those substitutions are located. Peptides with no matches are retained in the output to ensure complete coverage of the query set. These results can be used to exclude candidate peptides with high similarity to self-antigens, helping to prioritize targets with greater predicted specificity for experimental validation.

Patient Harmonic-Mean Best Rank (PHBR)

PHBR summarizes peptide–MHC binding predictions across a patient’s MHC genotype to identify candidate neoepitopes with high immunogenic potential [

43,

44]. Rather than relying on binding strength to a single allele, PHBR captures the overall likelihood of presentation by aggregating predictions across all relevant alleles using a harmonic mean. This metric has been shown to correlate with immune responsiveness, particularly in the context of checkpoint blockade therapy, and is valuable for filtering and prioritizing neoepitopes in personalized cancer immunotherapy studies [

44].

PHBR requires a list of neopeptide sequences and the patient’s MHC genotype as input. Users may specify class I alleles, class II alleles, or both, depending on the immunological context. For each peptide, binding predictions are performed across the entire set of provided MHC alleles using established algorithms such as NetMHCpan. Optionally, users can include the mutation position within the peptide to focus the analysis on the altered region and exclude flanking wild-type regions from consideration.

The tool outputs a single PHBR score for each peptide, calculated as the harmonic mean of its predicted percentile rank values across the selected alleles. Lower PHBR scores indicate higher and more consistent binding potential, suggesting increased likelihood of antigen presentation and T cell recognition. These scores can be used to prioritize peptides for downstream experimental validation, stratify patient samples, or integrate antigen presentation into multi-parameter models of tumor immunogenicity.

Clustering

The Clustering tool enables redundancy reduction in peptide datasets by grouping highly similar sequences [

45]. This functionality is useful for collapsing overlapping peptides that arise from sliding window predictions, alternative transcripts, or post-translational variants. By reducing redundancy, the tool simplifies downstream analysis, improves interpretability, and helps prioritize non-redundant peptide sets for visualization or experimental testing.

As input, the tool requires a list of peptide sequences and a minimum sequence identity threshold, typically expressed as a percentage. Clustering is performed using single-linkage (nearest-neighbor) methodology, where peptides are grouped together if any pair within the group meets or exceeds the specified identity threshold.

The output includes a cluster assignment for each input peptide, a list of representative peptides (usually the first or longest sequence in each cluster), and pairwise identity scores where applicable. This output facilitates the selection of unique or representative sequences from large candidate sets, making it especially useful for epitope visualization, vaccine design, or minimizing redundancy in peptide synthesis panels.

Antigen eXpression based Epitope Likelihood-Function (AXEL-F)

AXEL-F integrates MHC class I binding predictions with source antigen expression levels to estimate the likelihood that a peptide is naturally presented on the cell surface [

11]. While MHC binding affinity is a key determinant of presentation, it does not account for whether the source protein is sufficiently expressed to generate detectable peptides. AXEL-F addresses this limitation by combining predicted binding strength with RNA expression data, enabling more accurate epitope prioritization in both infectious disease and cancer settings.

The tool accepts peptide sequences, associated MHC alleles, and gene-level or transcript-level TPM values as input. Expression values may be derived from user-supplied RNA-Seq data or estimated using companion tools such as PepX. Binding predictions are computed using NetMHCpan, and a joint likelihood score is calculated by integrating the expression data with the predicted binding rank, following a Boltzmann-like formulation. This approach models the probability of peptide presentation as a function of both binding and antigen abundance.

The output includes an AXEL-F score for each peptide–allele pair, which can be interpreted as a relative measure of epitope presentation likelihood. Lower scores indicate peptides that are both strong binders and derived from highly expressed transcripts. AXEL-F has been shown to improve prediction performance in both ligand and T cell epitope datasets when compared to binding-only approaches.

Peptide Synthesis Score (PepSySco)

PepSySco predicts the likelihood that a peptide will be successfully synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase chemistry, providing a practical filter for selecting peptides suitable for downstream applications [

25]. The model was trained on large datasets of mass spectrometry-validated peptides and captures sequence-level features that influence synthetic yield. This prediction is particularly useful in large-scale epitope discovery pipelines, where failed peptide synthesis can delay or limit experimental validation.

The tool accepts a list of peptide sequences as input. Peptides can be submitted via direct text entry or batch file upload. Each peptide is independently evaluated using a logistic regression model that outputs a probability score based solely on its sequence characteristics relevant to synthesis.

The output includes a numerical score between 0 and 1 for each peptide, representing the probability of successful synthesis. Higher scores indicate a higher likelihood of synthesis success. The results can be used to prioritize peptides for synthesis and to exclude candidates with low feasibility, helping optimize resources and reduce the rate of synthesis failures in high-throughput workflows.

TCRMatch

TCRMatch predicts the epitope specificity of input T cell receptor (TCR) sequences based on sequence similarity to previously characterized receptors [

24]. By leveraging the IEDB’s curated collection of TCR–epitope pairs, TCRMatch enables annotation of CDR3 sequences with putative antigen targets and supports the interpretation of bulk or single-cell TCR sequencing data.

The tool accepts TCR β-chain CDR3 amino acid sequences as input. Users can also upload output files generated by TRUST4, a widely used tool to reconstruct TCR repertoires from single-cell and bulk RNA-Seq data [

46,

47]. TCRMatch uses a k-mer–based similarity approach to compare query sequences to known TCRs, identifying matches based on shared sequence motifs. Users can adjust parameters, such as the k-mer size and similarity threshold, to control the stringency of the search.

The output includes a list of matched TCRs from the IEDB, along with the corresponding epitope, source antigen, organism, and similarity score. For each query sequence, multiple matches may be returned, ranked by similarity. These results allow users to annotate TCRs with likely antigen targets, explore immune responses in clinical or research settings, and generate hypotheses for downstream validation. TCRMatch is particularly useful for interpreting TCR repertoire shifts in cancer, infection, or autoimmunity studies.

Pipeline Integration

NGT supports the construction of integrated analysis pipelines, enabling users to combine multiple tools into structured, reproducible workflows. Pipelines allow the sequential execution of analyses in which the output of one tool serves as the input for the next. At each stage, intermediate results can be reviewed and filtered, permitting the propagation of selected candidates downstream.

This functionality is designed to facilitate the systematic evaluation of large candidate sets and supports common use cases in cancer epitope discovery, such as prioritization based on MHC binding, expression level, immunogenicity, and self-similarity. The pipeline interface includes a visual sidebar that maps the analysis steps and their parameters. Users may save, revisit, and share pipelines via stable URLs, either including input and output data or preserving only the pipeline specification. Programmatic access is available through a documented API for users requiring automated or large-scale analyses (refer to

https://nextgen-tools.iedb.org/docs/api/index.html).

The following sections describe three representative pipeline scenarios using tools available on NGT to illustrate practical applications of this framework.

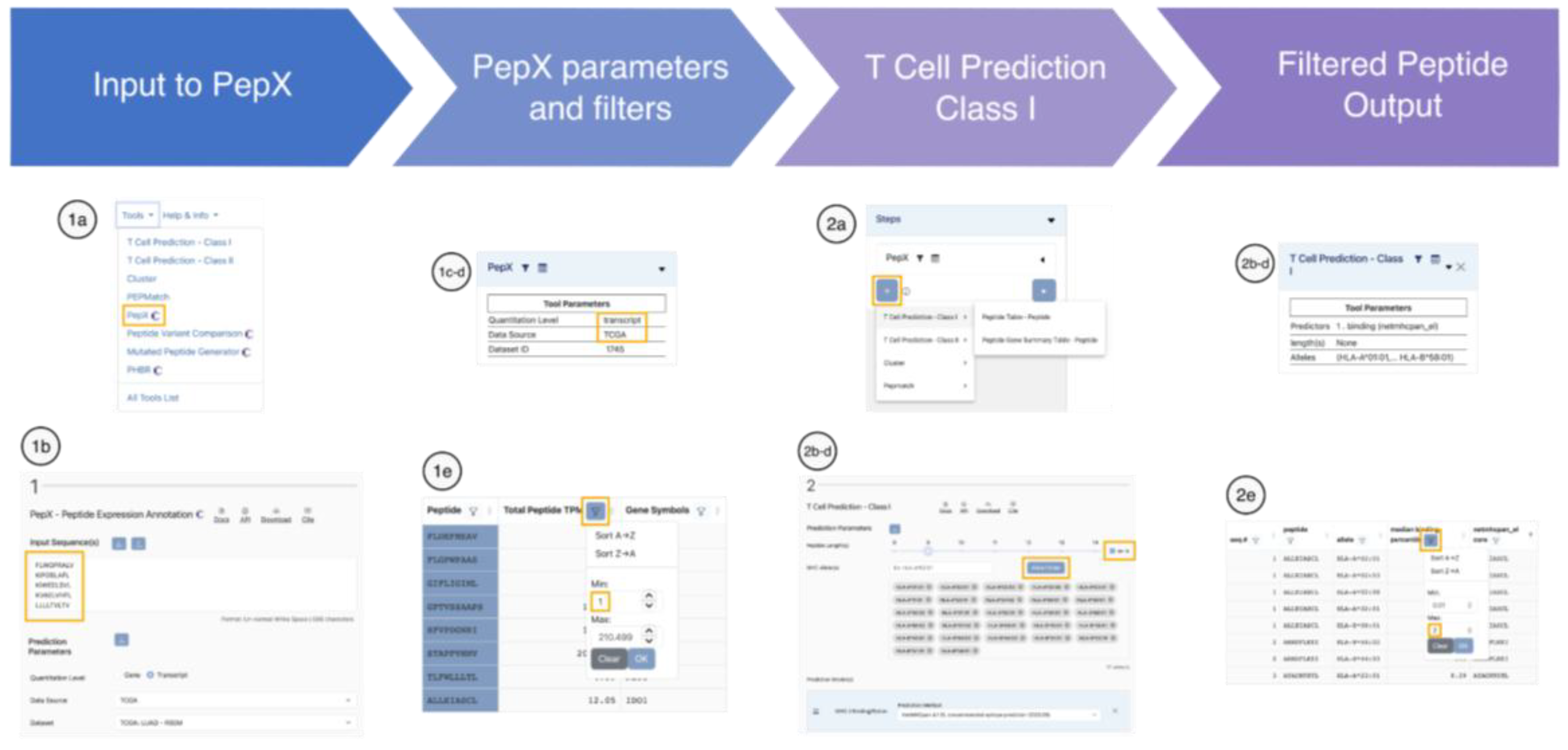

Case Scenario I: Expression-Based Filtering of Candidate Tumor-Associated Antigens in NSCLC

A translational research team discovered a set of tumor-associated proteins in an in-house non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cohort and is now evaluating their immunogenic potential. Although these proteins appeared overexpressed in the initial small dataset, the team seeks to systematically confirm expression patterns and tissue specificity in larger, independent cohorts, and select peptides that might be suitable for inclusion in a therapeutic vaccine.

This pipeline allows the team to focus on peptides that are both expressed in lung cancer and predicted to bind to MHC (

Figure 2). The researchers were able to substantially reduce the initial list of candidate peptides, yielding a more feasible set for downstream experimental validation.

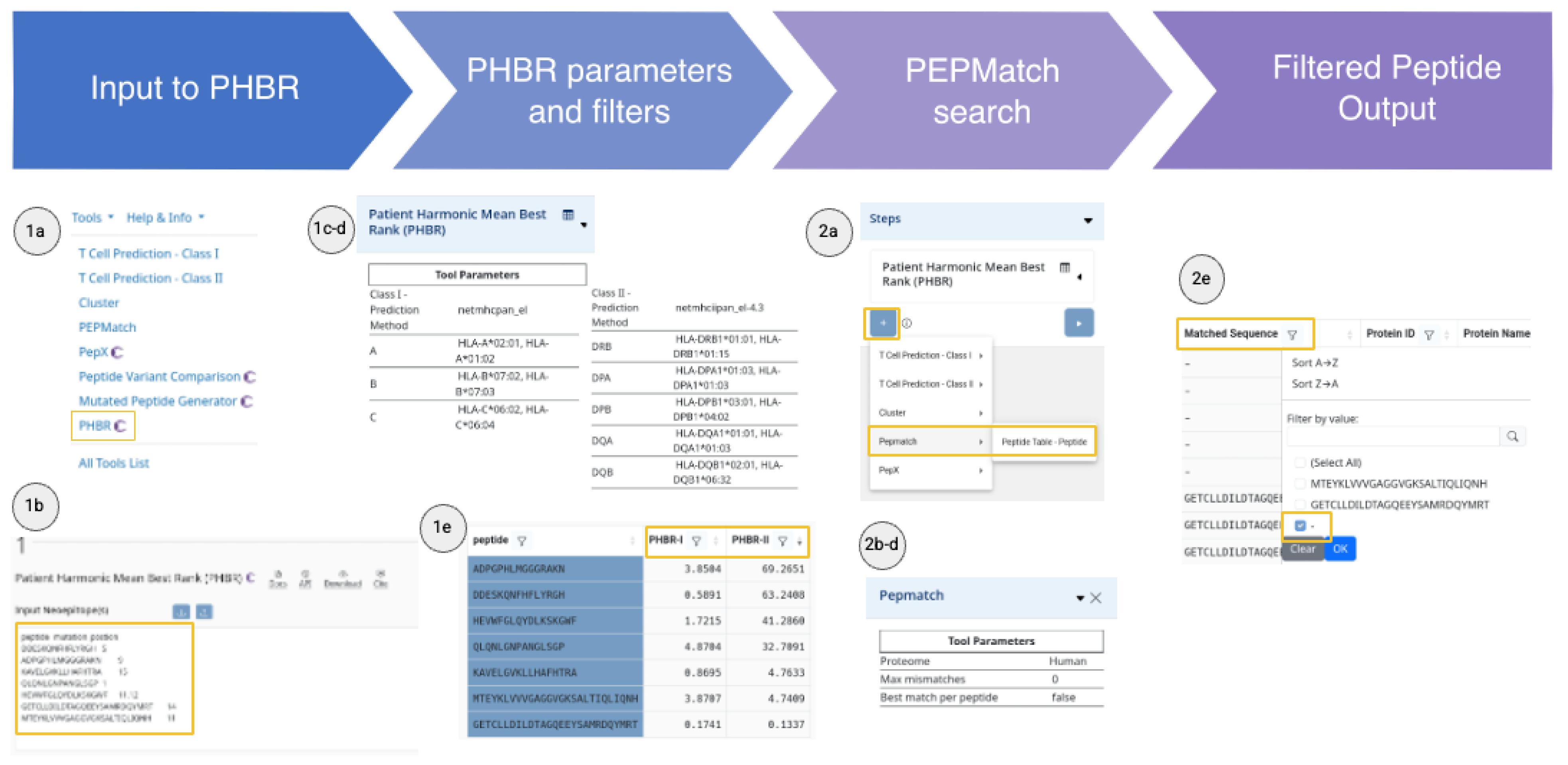

Case Scenario II: Neoepitope Discovery for Personalized Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma

A neuro-oncology team is developing a personalized mRNA vaccine for a glioblastoma patient. They have already performed variant calling based on whole-exome sequencing data of paired tumor and normal samples. Their goal is to prioritize highly expressed mutations subject to T cell recognition.

This pipeline allows the team to prioritize patient-specific glioblastoma neopeptides that are likely immunogenic and not present in the human proteome, yielding a refined set of safe candidates for therapeutic development (

Figure 3). Since they have no exact sequence matches, they are less likely to be tolerated by the immune system.

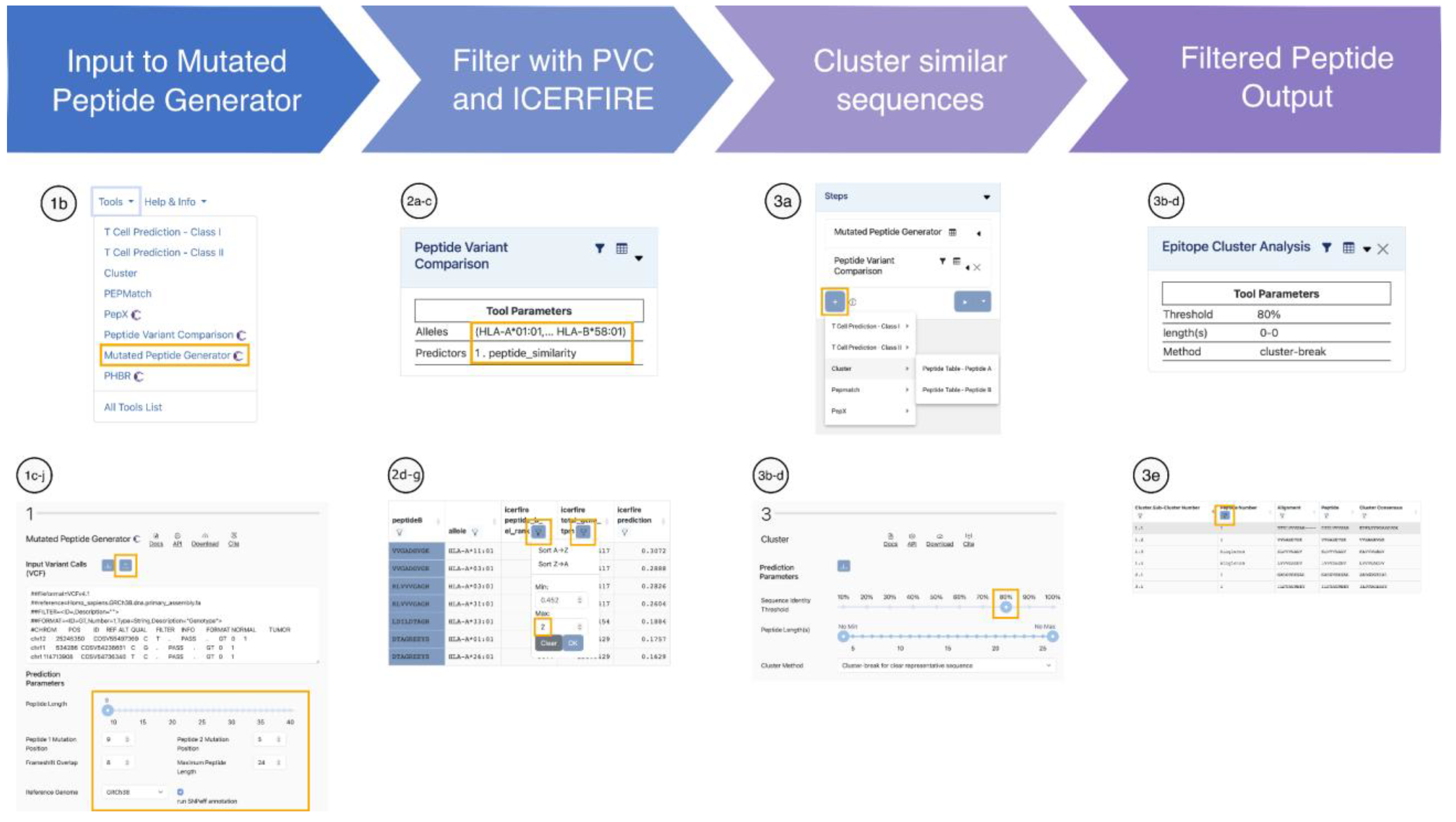

Case Scenario III: Evaluation of Shared RAS Neoepitopes Across Tumor Types

A collaborative team is investigating shared CD8+ T cell neoepitopes arising from common KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS hotspot mutations across multiple cancer types, including pancreatic, colorectal, and lung adenocarcinomas. The aim is to identify widely presented, non-redundant, and low-risk neoepitopes for pan-cancer immunotherapy.

-

Translate RAS mutations into neopeptides with MPG

Compile a set of frequent mutations in the KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS genes.

From the tools menu drop-down, select the Mutated Peptide Generator (MPG).

Upload the mutations in VCF format.

Generate short peptide sequences by selecting a ‘Peptide Length’ of 9 with the slider.

Generate mutated peptides with the mutation located at position 9, a frequent MHC class I anchor, by setting ‘Peptide 1 Mutation Position’ to 9.

Also generate peptides with the mutation in the middle by setting ‘Peptide 2 Mutation Position’ to 5.

Select a ‘Frameshift Overlap’ of 8 to generate all possible overlapping peptides from frameshifting mutations.

Set the ‘Maximum Peptide Length’ to 14 amino acids.

Select the ‘Reference Genome’ corresponding to the one used for generating the VCF file.

Click the checkbox to ‘Run SnpEff annotations’, and click ‘Run’.

-

Prioritize and filter neoepitope candidates with PVC and ICERFIRE

On the left side, under ‘Pipeline Map’, click on ‘+’, select ‘Peptide Variant Comparison’, and choose ‘Unique Peptides - Reference Peptide + Mutant Peptide’. The PVC interface appears below the MPG results.

To select a broad panel of ‘MHC Allele(s)’, click on the ‘Allele Finder’. In the pop-up window select ‘27 Allele Panel’ and click on ‘Submit’.

Under ‘Prediction Model’ select ‘Neo-Epitope Immunogenicity’ and ‘ICERFIRE 1.0’ and click ‘Run’.

ICERFIRE integrates antigen presentation predictions with NetMHCpan 4.1. To view these, click on ‘Display Columns’ and add ‘icerfire peptide_b_el_rank’. Peptides with scores < 2% are considered binders, and those with scores ≤ 0.5% are classified as strong binders. Use the sciphon icon to filter out peptides that are not predicted to bind (e.g. select a maximum value of 2).

ICERFIRE also calculates peptide expression in tumors using PepX with the TCGA pan-cancer dataset. These values are reported in the ‘icerfire total_gene_tpm’ column. Use the sciphon icon to filter out peptides that are not sufficiently expressed (e.g., select a minimum value of 1 TPM).

Prioritize the best candidates by sorting in ascending order by ‘icerfire percentile rank’. The best predicted candidates have the lowest values.

Click on ‘Save Table State’ to select the filtered data for downstream analysis.

-

Remove redundant candidates with Cluster

On the left side, under ‘Pipeline Map’, click on ‘+’, select ‘Cluster’, and choose the ‘Peptide Table – Peptide B’ corresponding to the mutated peptide. The Epitope Cluster Analysis interface appears below the PVC results.

As some of these peptides are highly similar, select a high ‘Sequence Identity Threshold’ (e.g., 80%) to avoid grouping them all in a few or a unique cluster.

Allow all possible ‘Peptide Length(s)’ by selecting ‘No Min’ and ‘No Max’ with the slider.

Choose the ‘Cluster-break for clear representative sequence’ clustering method, and click ‘Run’.

To select a representative sequence per cluster, use the sciphon on the ‘Peptide Number’ column, and filter ‘Singletons’ and peptides number 1.

This pan-cancer discovery pipeline helped the team to identify non-redundant public neoepitope candidates that are broadly presentable for further preclinical development (

Figure 4).

Conclusion and Discussion

Accurate and efficient identification of cancer epitopes remains a central challenge in immuno-oncology. While foundational tools for MHC binding prediction have long served the broader immunology community, recent advances in cancer immunogenomics have created a demand for methods that can accommodate the unique biological and clinical features of tumors. These include somatic mutations, tumor-specific antigen expression, patient MHC diversity, and tolerance mechanisms, all of which impact epitope presentation and immunogenicity.

The tools available in the Next-Generation IEDB Tools (NGT) platform represent a significant advance toward meeting these needs. By combining extensively benchmarked MHC binding predictors with newly developed cancer-specific modules, the platform enables researchers to move systematically from genomic data to prioritized epitope candidates. Tools such as the Mutated Peptide Generator, Peptide Variant Comparison, PepX, and PHBR, address core analytical tasks in cancer epitope discovery, supporting variant annotation, mutant/wild-type comparison, expression-aware filtering, and patient-specific scoring. When used together within NGT’s pipeline framework, these tools facilitate end-to-end workflows for identifying neoepitopes and shared tumor-associated antigens.

One of the strengths of the NGT platform is its flexibility. Tools can be used independently or assembled into custom pipelines that mirror the biological steps of antigen processing and immune recognition. The pipeline builder supports filtering at each step, data retention, and reproducibility through shareable links and programmatic access. These features, together with a minimalistic interface and API support, allow both novice and advanced users to construct analyses tailored to diverse research questions and datasets.

Importantly, the development and refinement of these tools have been guided by feedback from the cancer immunology community. Iterative improvements in functionality, parameterization, and output interpretation have ensured that the tools remain aligned with experimental workflows and translational goals.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. Despite ongoing development, multiple analytical tools relevant to cancer epitope research remain available only through the original IEDB Analysis Resource (tools.iedb.org) and have not yet been fully integrated into Next-Generation IEDB Tools. The planned incremental migration of these tools will help consolidate functionality within a unified, modernized framework. Furthermore, for tools such as PepX, expression annotation currently relies on public datasets including TCGA, GTEx, and CCLE. While these provide valuable surrogates, patient-matched transcriptomic data remains preferable when available, particularly for personalized immunotherapy applications. Finally, although the tools are accessible via web and API interfaces, integration with external pipelines and datasets often requires manual data formatting and preprocessing. Addressing these limitations will be a key focus of future platform enhancements.

In conclusion, the cancer-specific tools available on the Next-Generation IEDB Tools platform offer a comprehensive, flexible, and scalable solution for cancer epitope analysis. By enabling integration of genomic and immunological features into modular workflows, the platform supports both exploratory and hypothesis-driven research. As immunotherapy advances toward greater personalization, these tools provide a critical computational foundation for guiding the discovery and development of clinically actionable cancer epitopes.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [U24CA248138].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

References

- Karl Erik Hellström, IH. Tumor Antigens. In: Bertino JR, editor. Encyclopedia of Cancer (Second Edition). Academic Press; 2002. pp. 459–466.

- Jhunjhunwala, S.; Hammer, C.; Delamarre, L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Shen, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, Z.; Huang, C.; Fu, L. Neoantigens: promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Zhao, X.; Fu, Y.-X.; Liang, Y. Eliciting antitumor immunity via therapeutic cancer vaccines. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 840–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopanenko, A.V.; Kosobokova, E.N.; Kosorukov, V.S. Main Strategies for the Identification of Neoantigens. Cancers 2020, 12, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Lanka, M.; Frentzen, A.; Premlal, A.L.R.; Sidney, J.; Vaughan, K.; Greenbaum, J.; Robbins, P.; Gartner, J.; Sette, A.; et al. Predicting T cell recognition of MHC class I restricted neoepitopes. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1492508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Derhovanessian, E.; Miller, M.; Kloke, B.-P.; Simon, P.; Löwer, M.; Bukur, V.; Tadmor, A.D.; Luxemburger, U.; Schrörs, B.; et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 2017, 547, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Sette, A. T Cell Epitope Predictions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-T.R.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. A large-scale study of peptide features defining immunogenicity of cancer neo-epitopes. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borch, A.; Carri, I.; Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, H.M.G.; Munk, K.K.; Montemurro, A.; Kristensen, N.P.; Tvingsholm, S.A.; Holm, J.S.; Heeke, C.; et al. IMPROVE: a feature model to predict neoepitope immunogenicity through broad-scale validation of T-cell recognition. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1360281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Lee, J.; Greenbaum, J.; Schoenberger, S.P.; Miller, A.; Kim, Y.J.; Sette, A.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B. Combined assessment of MHC binding and antigen abundance improves T cell epitope predictions. iScience 2022, 25, 103850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, H.M.G.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. The role of antigen expression in shaping the repertoire of HLA presented ligands. iScience 2022, 25, 104975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkizova, S.; Klaeger, S.; Le, P.M.; Li, L.W.; Oliveira, G.; Keshishian, H.; Hartigan, C.R.; Zhang, W.; Braun, D.A.; Ligon, K.L.; et al. A large peptidome dataset improves HLA class I epitope prediction across most of the human population. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 38, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 14. Vita R, Blazeska N, Marrama D, IEDB Curation Team Members, Duesing S, Bennett J, et al. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2024 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53: D436–D443.

- Vita, R.; Blazeska, N.; Marrama, D.; Members, I.C.T.; Shackelford, D.; Zalman, L.; Foos, G.; Zarebski, L.; Chan, K.; Reardon, B.; et al. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2024 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D436–D443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Blazeska, N.; Vita, R.; Carter, H.; Nielsen, M.; Schoenberger, S.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. The Cancer Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (CEDAR). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D845–D852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan Z, Kim K, Kim H, Ha B, Gambiez A, Bennett J, et al. Next-generation IEDB tools: a platform for epitope prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52: W526–W532.

- Yan, Z.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Ha, B.; Gambiez, A.; Bennett, J.; Mendes, M.F.d.A.; Trevizani, R.; Mahita, J.; Richardson, E.; et al. Next-generation IEDB tools: a platform for epitope prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W526–W532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.-T.; Li, X.; Lan, A.-L.; Ji, P.-F.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Ma, X.-Y. Advances and challenges in neoantigen prediction for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1617654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’dOnnell, T.J.; Rubinsteyn, A.; Laserson, U. MHCflurry 2.0: Improved Pan-Allele Prediction of MHC Class I-Presented Peptides by Incorporating Antigen Processing. Cell Syst. 2020, 11, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Blazeska, N.; Carter, H.; Nielsen, M.; Cohen, E.; Kufe, D.; Conejo-Garcia, J.; Robbins, P.; Schoenberger, S.P.; Peters, B.; et al. The Cancer Epitope Database and Analysis Resource: A Blueprint for the Establishment of a New Bioinformatics Resource for Use by the Cancer Immunology Community. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Paul, S.; Yan, Z.; Kim, H.; Jespersen, M.C.; Jurtz, V.; Andreatta, M.; A Greenbaum, J.; Marcatili, P.; et al. IEDB-AR: immune epitope database—analysis resource in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W502–W506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronister, W.D.; Crinklaw, A.; Mahajan, S.; Vita, R.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Yan, Z.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Jessen, L.E.; Nielsen, M.; Christley, S.; et al. TCRMatch: Predicting T-Cell Receptor Specificity Based on Sequence Similarity to Previously Characterized Receptors. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, I.; Gutman, R.; Sidney, J.; Chihab, L.; Mishto, M.; Liepe, J.; Chiem, A.; Greenbaum, J.; Yan, Z.; Sette, A.; et al. Predicting the Success of Fmoc-Based Peptide Synthesis. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23771–23781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frentzen, A.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Kim, H.; Peters, B.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z. Estimating tissue-specific peptide abundance from public RNA-Seq data. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1082168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KRM, Ozenberger BA, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45: 1113–1120.

- Carithers, L.J.; Moore, H.M. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreservation Biobanking 2015, 13, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Oksvold, P.; Fagerberg, L.; Lundberg, E.; Jonasson, K.; Forsberg, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Kampf, C.; Wester, K.; Hober, S.; et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J, Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER 3rd, et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature. 2019;569: 503–508.

- Moutaftsi, M.; Peters, B.; Pasquetto, V.; Tscharke, D.C.; Sidney, J.; Bui, H.-H.; Grey, H.; Sette, A. A consensus epitope prediction approach identifies the breadth of murine TCD8+-cell responses to vaccinia virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurtz, V.; Paul, S.; Andreatta, M.; Marcatili, P.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.0: Improved Peptide–MHC Class I Interaction Predictions Integrating Eluted Ligand and Peptide Binding Affinity Data. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3360–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calis, J.J.A.; Maybeno, M.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Weiskopf, D.; De Silva, A.D.; Sette, A.; Keşmir, C.; Peters, B. Properties of MHC Class I Presented Peptides That Enhance Immunogenicity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Lundegaard, C.; Lamberth, K.; Buus, S.; Brunak, S.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M. An integrative approach to CTL epitope prediction: A combined algorithm integrating MHC class I binding, TAP transport efficiency, and proteasomal cleavage predictions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranzl, T.; Larsen, M.V.; Lundegaard, C.; Nielsen, M. NetCTLpan: pan-specific MHC class I pathway epitope predictions. Immunogenetics 2010, 62, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keşmir, C.; Nussbaum, A.K.; Schild, H.; Detours, V.; Brunak, S. Prediction of proteasome cleavage motifs by neural networks. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2002, 15, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Arlehamn, C.S.L.; Scriba, T.J.; Dillon, M.B.; Oseroff, C.; Hinz, D.; McKinney, D.M.; Pro, S.C.; Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; et al. Development and validation of a broad scheme for prediction of HLA class II restricted T cell epitopes. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 422, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, J.B.; Kaabinejadian, S.; Yari, H.; Kester, M.G.D.; van Balen, P.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Nielsen, M. Accurate prediction of HLA class II antigen presentation across all loci using tailored data acquisition and refined machine learning. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadj6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.K.; Karosiene, E.; Edwards, L.; Grifoni, A.; Paul, S.; Andreatta, M.; Weiskopf, D.; Sidney, J.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B.; et al. Predicting HLA CD4 Immunogenicity in Human Populations. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Karosiene, E.; Dhanda, S.K.; Jurtz, V.; Edwards, L.; Nielsen, M.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. Determination of a Predictive Cleavage Motif for Eluted Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Ligands. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrama, D.; Chronister, W.D.; Westernberg, L.; Vita, R.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Sette, A.; Nielsen, M.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Peters, B. PEPMatch: a tool to identify short peptide sequence matches in large sets of proteins. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty Pyke R, Thompson WK, Salem RM, Font-Burgada J, Zanetti M, Carter H. Evolutionary Pressure against MHC Class II Binding Cancer Mutations. Cell. 2018;175: 416–428.e13.

- Marty, R.; Kaabinejadian, S.; Rossell, D.; Slifker, M.J.; van de Haar, J.; Engin, H.B.; de Prisco, N.; Ideker, T.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Font-Burgada, J.; et al. MHC-I Genotype Restricts the Oncogenic Mutational Landscape. Cell 2017, 171, 1272–1283.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.K.; Vaughan, K.; Schulten, V.; Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Development of a novel clustering tool for linear peptide sequences. Immunology 2018, 155, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Lin, M.; Liu, M.; Ma, Q. Single cells and TRUST4 reveal immunological features of the HFRS transcriptome. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1403335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, L. TRUST4 Interrogates the Immune Receptor Repertoire in Oncology and Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022, 10, 786–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, J.; Sidney, J.; Chung, J.; Brander, C.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Functional classification of class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules reveals seven different supertypes and a surprising degree of repertoire sharing across supertypes. Immunogenetics 2011, 63, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).