1. Introduction

Small extracellular vesicles (small EVs) are 30-200 nm bioactive particles that play crucial roles in cell-cell communication by carrying proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids including microRNAs [

1,

2,

3]. Small EVs also play pivotal roles during pregnancy. They are secreted from trophoblasts, and, thus, flow into maternal circulation [

4,

5]. Their secretion quantity is one of the main factors in small EV-related biology/pathology. This secretion quantity changes based on the cell type and pathological conditions (e.g., cancer, autoimmune disease) [

6,

7,

8,

9]; patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) show a higher number of serum-derived small EVs compared with healthy controls [

10]. Regarding pregnancy, the quantity of serum/plasma-derived small EVs increases as pregnancy progresses [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the quantity of plasma-derived small EVs increases in patients with preeclampsia (PE) [

14,

15,

16]. The amount of small EVs is usually measured by quantitative analyses (e.g., ELISA) using specific markers [

17]. However, the identification of such specific markers remains a subject of debate. A recent study in a high-impact journal investigated EVs and their markers in several materials including cell lines, tissue explants, serum, plasma, lymphatic fluid, bone marrow, and biliary liquid [

18]. The positive rate of the markers totally differed by origin or cell. The most useful biomarker that physicians use is blood (serum, plasma). CD63 has been the most widely used as a small EV marker. However, according to the recent study [

18], CD63 was negative in blood (serum, plasma)-derived small EVs. We aimed to conduct a re-evaluation of small EVs in maternal blood during pregnancy. In this study, we explored small EV markers in maternal plasma, and measured their quantity using another small EV marker other than CD63. Furthermore, we examined the quantity of plasma-derived small EVs in patients with PE compared with normotensive controls.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

Our study followed two designs: a case-control study, and a prospective nested case-control study. First, we show patient characteristics in the case-control study (

Table 1). We compared patients with early-onset preeclampsia (EoPE) with normotensive controls. Compared with normotensive controls in the second trimester, systolic blood pressure (median 165 [interquartile range (IQR) 161–176] vs. 116 [108–123] mmHg, respectively, p < 0.001), diastolic blood pressure (100 [89.5–108.5] vs. 72 [62–79] mmHg, respectively, p < 0.001), and serum creatinine levels (0.70 [0.50–0.79] vs. 0.49 [0.39–0.52] mg/dL, respectively, p = 0.03) were significantly elevated in patients with EoPE (

Table 1). The gestational age at delivery was significantly earlier (33.6 [33.0–34.3] vs. 39.3 [38.1–40.6] weeks, respectively, p < 0.001), and birth weight was significantly lower (1750 [1292–1904] vs. 2994 [2842–3156] grams, respectively, p < 0.001) (

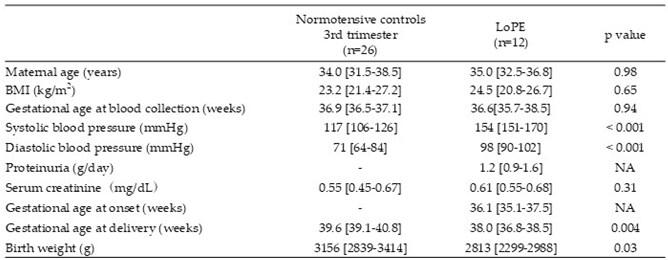

Table 1). Compared with normotensive controls in the third trimester, systolic blood pressure (154 [151–170] vs. 117 [106–126] mmHg, respectively, p < 0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (98 [90–102] vs. 71 [64–84] mmHg, respectively, p < 0.001) were significantly elevated in patients with late-onset preeclampsia (LoPE) (

Table 2). The gestational age at delivery was significantly earlier (38.0 [36.8–38.5] vs. 39.6 [39.1–40.8] weeks, respectively, p = 0.004), and birth weight was significantly lower (2813 [2299–2988] vs. 3156 [2839–3414] grams, respectively, p = 0.03) (

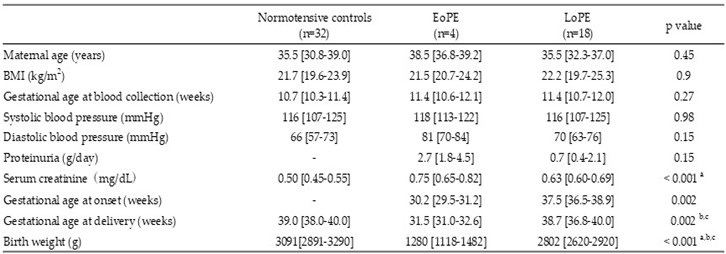

Table 2). Second, we show patient characteristics in the prospective nested case-control study (

Table 3). We included singleton pregnant women in the first trimester prospectively and collected blood samples at that time. Then, we categorized them into three groups based on the perinatal outcome (normal controls, EoPE, LoPE). There were no significant differences in maternal age, BMI, or blood pressure among three groups (

Table 3). The serum creatine level showed a significant increase in patients with LoPE compared with the normotensive controls (

Table 3).

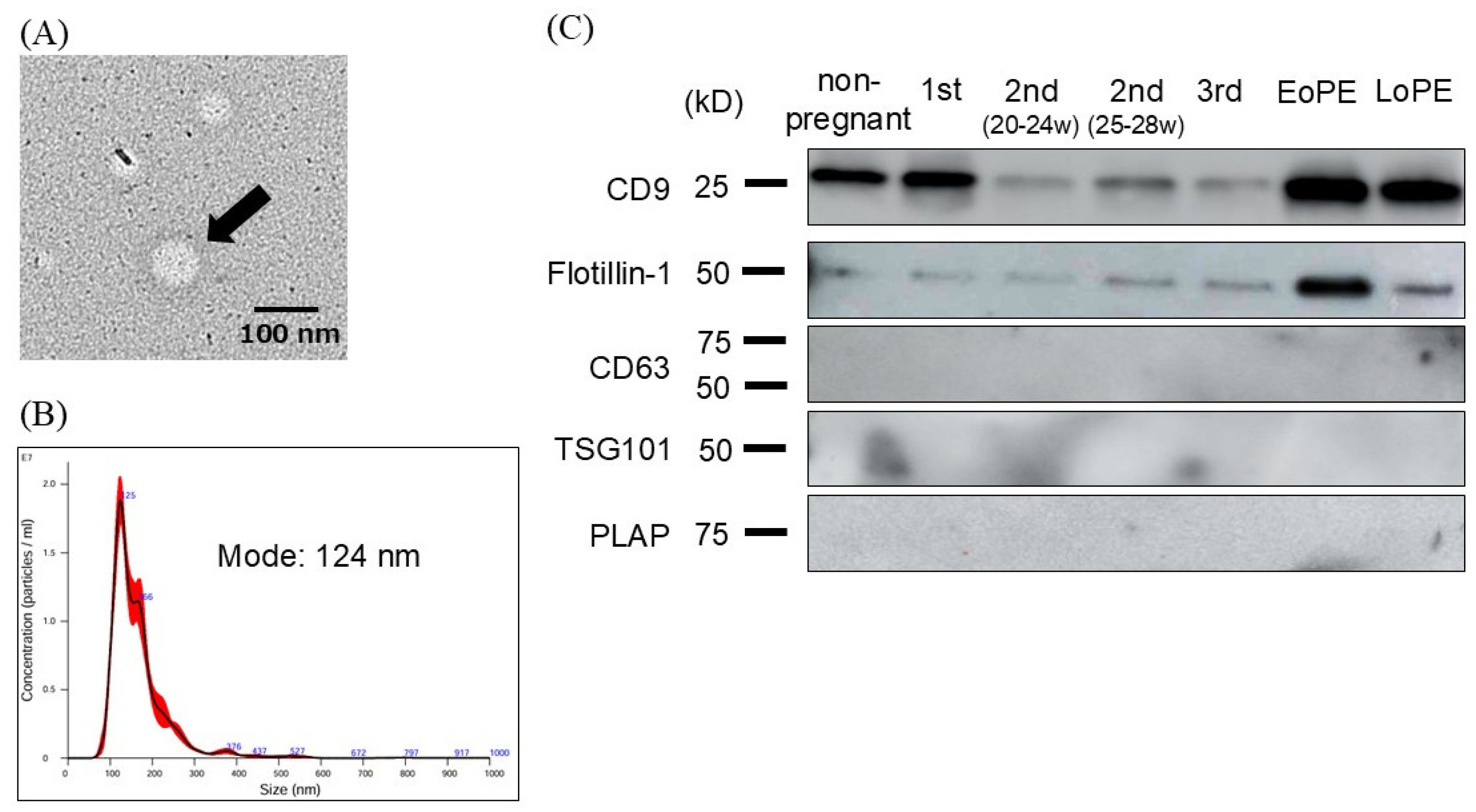

2.2. Characterization and Evaluation of Circulating Small EVs

We evaluated purified small EVs derived from maternal plasma using several methods. We confirmed the presence of particles with a diameter of approximately 100 nm by transmission electron microscopy (

Figure 1A). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) revealed that the majority of particles ranged from 110 to 140 nm in diameter (

Figure 1B). Next, we explored small EV markers in maternal plasma. Western blotting showed positive signals for CD9 and Flotillin-1, while CD63, TSG101, and placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), which are known as other tissue-derived small EV markers, were negative (

Figure 1C).

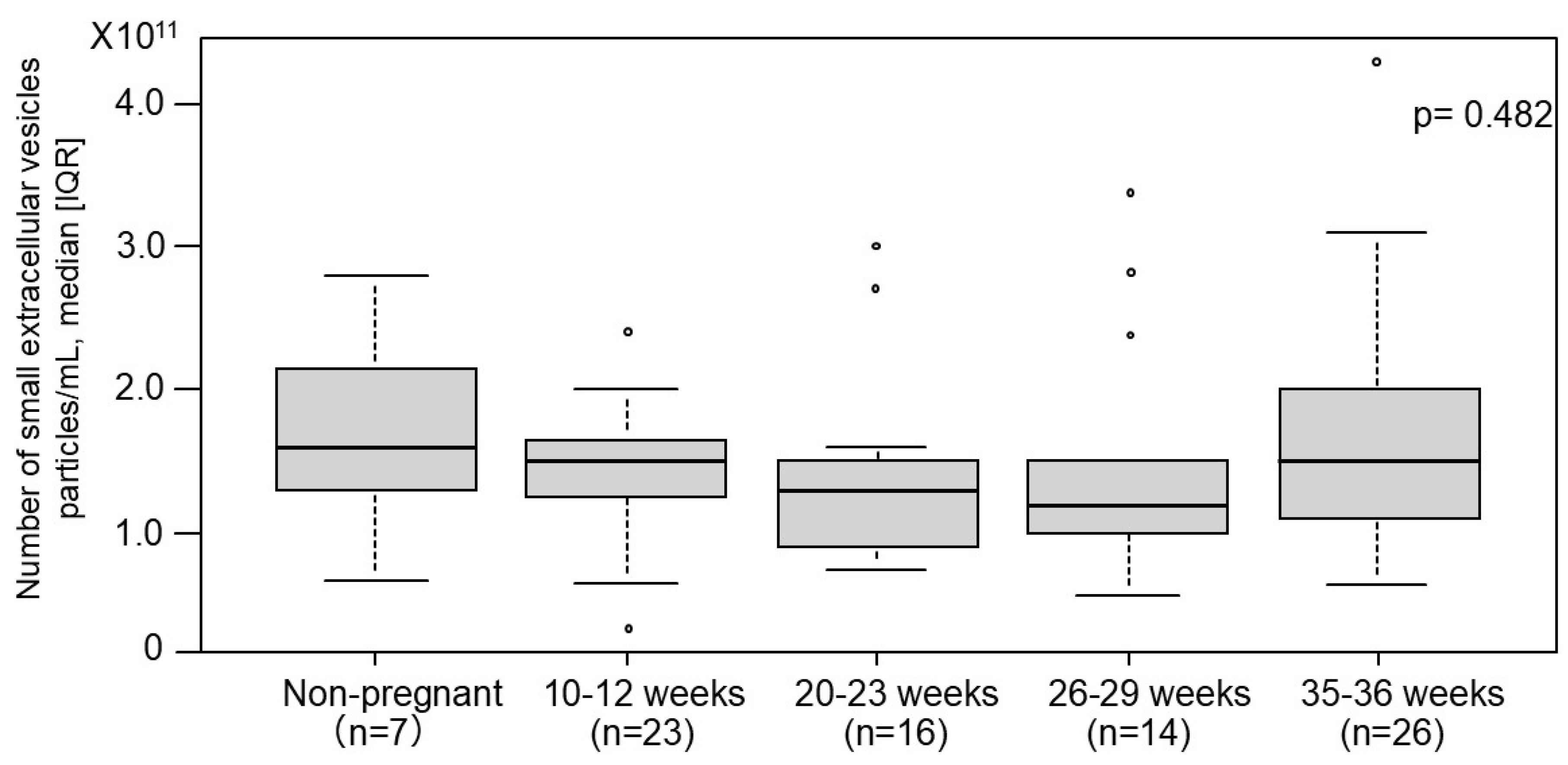

2.3. The Number of Small EVs in Non-Pregnant Women and Normotensive Controls

The number of small EVs was measured using an ELISA-based method targeting the surface marker CD9 based on the above-mentioned experiments (

Figure 2). Among normotensive controls, no significant differences in the number of small EVs were observed across varying gestational ages. Similarly, no significant differences were noted between non-pregnant women and normotensive controls.

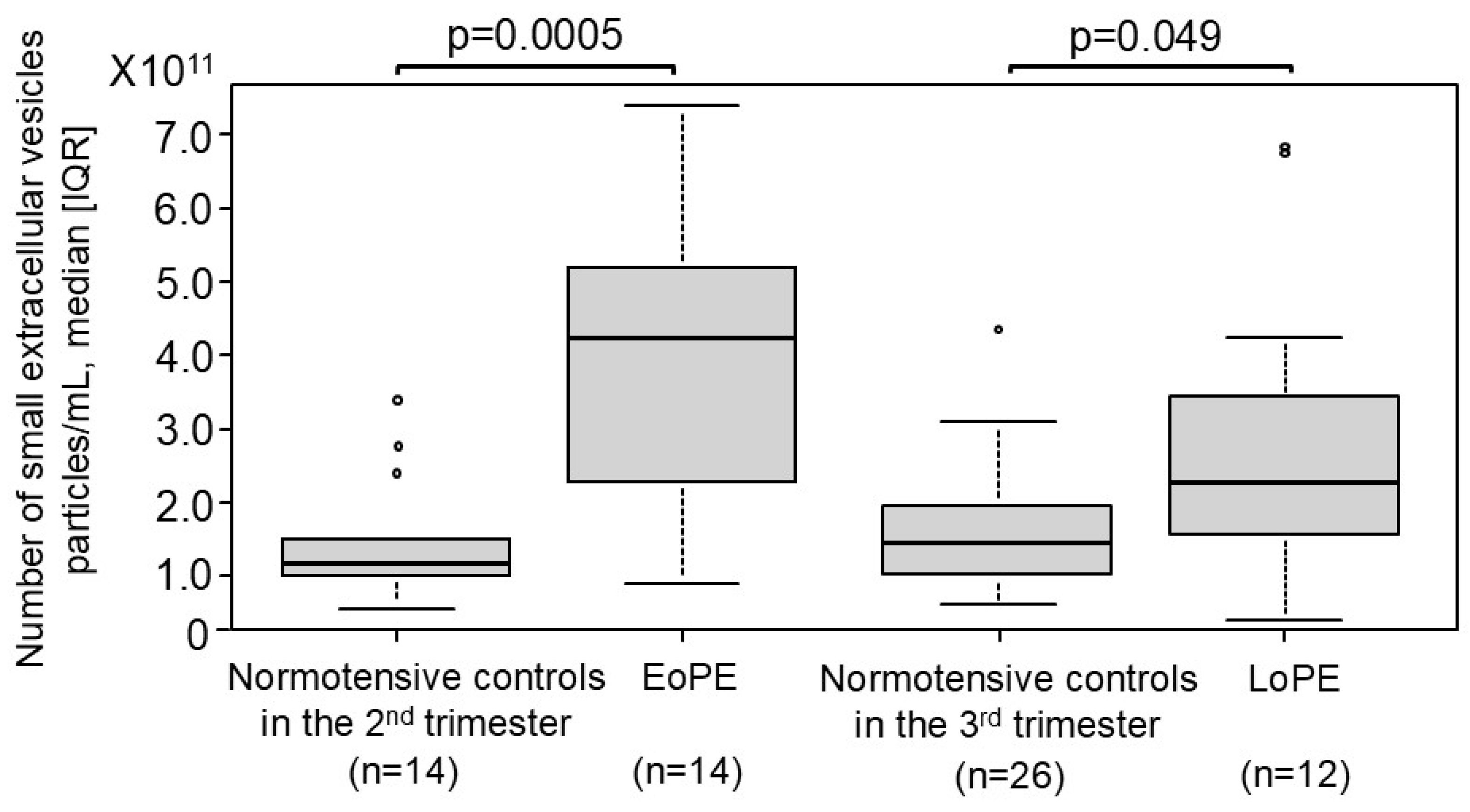

2.4. Comparison of the Number of Small EVs Between Patients with PE and Normotensive Controls

The number of small EVs in patients with EoPE was compared with normotensive controls (

Figure 3). In patients with EoPE, the number of small EVs was significantly higher approximately 3.5-fold than in normotensive controls during the second trimester (4.3×10

11 [2.4×10

11–5.2×10

11] vs. 1.2×10

11 [1.0×10

11–1.5×10

11] particles/mL, respectively, p = 0.0005). Similarly, in patients with LoPE, the number of small EVs was significantly higher approximately 1.5-fold than in normotensive controls during the third trimester (2.3×10

11 [1.6×10

11–3.4×10

11] vs. 1.5×10

11 [1.1×10

11–2.0×10

11] particles/mL, respectively, p = 0.049).

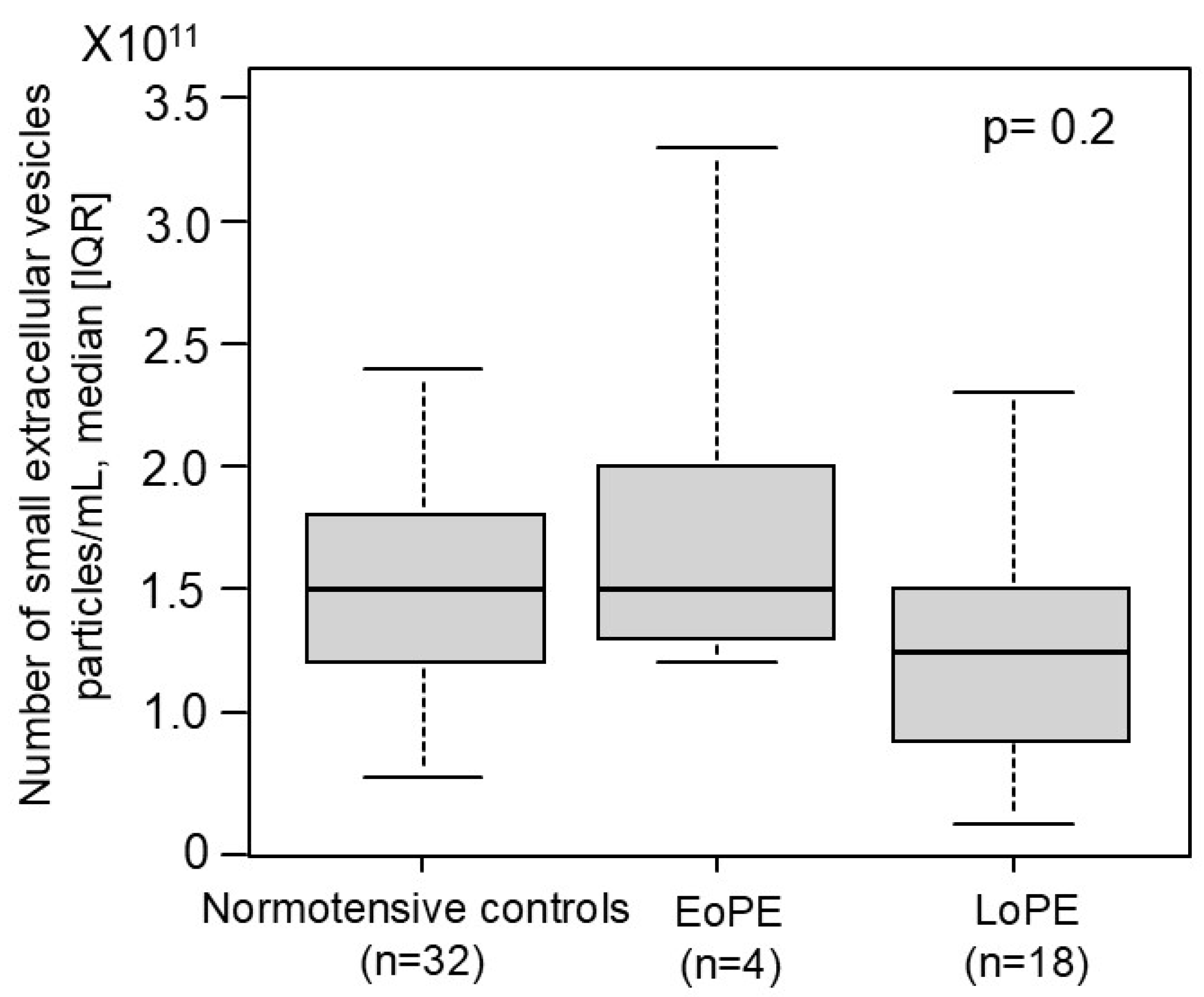

2.5. Comparison of the Number of Small EVs in the First Trimester Between Women Who Later Developed PE and Normotensive Controls in the Prospective Nested Case-Control Study

We investigated whether the number of small EVs in the first trimester can serve as a potential biomarker for PE (

Figure 4). We prospectively collected more than 1,400 blood samples of pregnant women in the first trimester. Of those, 4 cases with EoPE and 18 cases with LoPE occurred. We measured the number of small EVs in each group. No significant difference was observed in the number of small EVs between women who later developed PE (early- and late-onset) and normotensive controls.

3. Discussion

We identified several novel findings. First, the number of small EVs in human plasma was significantly increased in both early- and late-onset PE compared with healthy controls. Second, CD9 may be a more useful small EV marker in maternal plasma than CD63 which is the most widely used as a small EV marker. Furthermore, there was no significant change in the number of small EVs throughout any stage of pregnancy, being inconsistent with previous studies (11,12,13).

Regardless of onset time, the number of small EVs increased in patients with PE compared with gestational age-matched normotensive controls. Several studies reported that the number of small EVs in plasma increased in not only the presence of PE but also several malignancies (19,20,21). Matsumoto et al. (8) demonstrated that the number of serum EVs significantly increased in patients with esophageal cancer compared with those in healthy controls. Similar findings have also been reported in patients with lung (22,23) and prostate (24,25) cancer. It also increased in those with autoimmune disease (10). Regarding isolating small EVs, some of the above-previous mentioned studies did not employ ultracentrifugation. Instead, they used polymer precipitation (8, 10). Although this method is easy to collect small EVs, the rate of contamination other than small EVs is high (26). In our study, isolated EVs were validated using both electron microscopy and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and, thus, we consider that we could collect small EVs with good purity. Several mechanisms suggest that the number of small EVs increase in PE (27). In PE, impaired placental perfusion leads to hypoxia, which induces stress in syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts, resulting in an increased release of small EVs (28,29). The degree of increase is more apparent early- than late-onset PE. Clinical symptoms associated with placental insufficiency (e.g., fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios) can readily manifest in early-onset PE, suggesting that syncytiotrophoblasts can have deleterious effects on maternal cells. When plasma-derived small EVs in patients with PE were applied to human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs), their migration was significantly reduced (15). In addition, treatment with these EVs downregulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Moreover, serum-derived EVs from patients with PE contain increased levels of miR-155, which suppress eNOS expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (30). Plasma-derived small EVs from patients with PE are enriched in sFlt-1 and sEng, leading to HUVECs dysfunction (31).

CD9 may be a promising marker for small EVs in plasma. We performed western blotting for multiple small EV markers. Interestingly, classical small EV markers including CD63 and TSG101 were undetectable in plasma-derived small EVs, whereas CD9 was reliably detected. Our findings are supported by a large-scale study (18), although they did not investigate maternal samples. According to the study, small EVs isolated from the plasma of 120 people were evaluated for expression of 11 classical small EV markers using proteomic techniques. Surprisingly, no samples (0%) were positive for CD63, heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), or TSG101. Of those, CD63 has been one of the most widely-used as small EV markers (10,11,14) detectable in EVs derived from cell lines or tissue explants. However, it was not detected in blood-derived EVs (serum or plasma). CD9 showed the highest positive rate, as high as 62%, followed by heat shock protein family A member 8 (HSPA8) (58%). These results suggest that CD9 is the most reliable marker of plasma-derived small EVs. This comprehensive study also suggested novel EV markers. fibronectin1 (FN1) may serve as a promising novel marker for blood-derived small EVs, showing 100% positive rate. Future analyses of blood-derived small EVs should consider focusing on CD9 as a primary marker, along with novel markers for accuracy and comprehensive characterization.

There was no significant change in the number of small EVs throughout pregnancy, which showed a different result from previous reports. The previous reports showed that the number of small EVs increased as pregnancy progressed (11,12,13). The previous reports employed other small EV markers (e.g., PLAP, CD63), and the small EVs were extracted using commercial kits or density gradient methods (11,12,13). The placenta grows in volume as pregnancy progresses, and thus, the release of trophoblast-derived small EVs may increase accordingly. In contrast, the plasma volume in pregnant women increases with pregnancy progression. Taken together, our results may be valid. Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) may help in such cases. The percentage of the fetal fraction (amount of trophoblast-derived cell-free DNA) did not significantly change throughout pregnancy (32), although another study has reached different conclusions (33). The fetal fraction does not show a large increase relative to the marked growth in placental volume. Although the number of trophoblasts is small in early gestation, each cell may release small EVs more actively. The rate of small EVs release per trophoblast may decrease, resulting in a relatively stable total small EV level in plasma over time, even in late gestation. To better understand this phenomenon, it may be necessary to identify the cellular origin of small EVs. Some studies attempted to characterize trophoblast-derived small EVs. A report showed that such EVs could be detected in maternal circulation at early as 6 weeks using placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) (34). Further investigation is needed to determine the origin of small EVs using more specific and reliable placental markers. If this becomes feasible, assessment of the placental function through maternal blood sampling may be achievable.

PE prediction using small EVs remains challenging. We investigated the number of plasma-derived small EVs as predictive biomarkers for the development of PE in the first trimester. We observed a declining tendency in patients with LoPE, although the sample number was small. Identifying high-risk patients for PE in the first trimester would be of marked clinical value, because low-dose aspirin can significantly reduce the PE risk. To complete a prospective cohort study, a large sample size is essential. Additional prospective investigation with a large number is planned to clarify this issue.

There are several limitations in this study. First, although CD9 was employed as a marker for small EVs, there is no evidence that CD9 is universally expressed in plasma-derived small EVs. As above-mentioned, a multi-marker approach may be optimal. Second, we focused on the number and quantity of small EVs in blood. As a result, we did not analyze content of EVs, and thus, we were unable to explore their biological or pathological effects. Third, although contamination by non-vesicular extracellular particles (NVEPs) should be carefully assessed (26), this issue was not evaluated in the present study.

In summary, the number of small EVs did not increase throughout pregnancy. However, it significantly increased in patients with both early- and late-onset PE. CD9 may be one of the most reliable markers of small EVs in human plasma. Small EVs can play important roles in pregnancy maintenance and pregnancy-related complications including PE. Additional investigations are needed.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Participants and Sample Collection

The study included singleton pregnant women whose pregnancy course was followed at our institution between July 2013 and August 2023. Plasma samples were collected from 7 non-pregnant women, 79 normotensive controls (10–12 weeks: 23 cases; 20–23 weeks: 16 cases; 26–29 weeks: 14 cases; 35–36 weeks: 26 cases) and 26 patients with PE (early-onset: 14 cases; late-onset: 12 cases) to compare the number of small EVs. Among these, plasma samples from women who later developed PE (early-onset: 4 cases; late-onset: 18 cases) and those who experienced an uncomplicated pregnancy (32 cases) were used to investigate the difference of number of small EVs. PE was defined as new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) after 20 weeks of gestation, accompanied by proteinuria (≥300 mg/day), fetal growth restriction, or organ dysfunction (e.g., low platelet, liver dysfunction). The upper conditions returned to normal within 12 weeks postpartum. Early-onset PE was defined as onset before 34 weeks of gestation, and late-onset PE as onset at or after 34 weeks of gestation (35). Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and centrifuged at 2,700 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C (model 5500, KUBOTA, Tokyo, Japan). The plasma was stored at –80°C. All participants provided written informed consent approved by the institutional ethics committee.

4.2. Purification of Small EVs

Small EVs were purified from plasma using a sequential ultracentrifugation method, as described below. Briefly, 2 mL of plasma were diluted with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 45 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube (Cat. No. 32143650, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) and ultracentrifuged at 110,000 g for 2 hours at 4°C (Optima L-90 Ultracentrifuge, Type SW41Ti swinging-bucket rotor, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS, passed through a 0.2-μm filter (Cat. No. S7597, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany), transferred to a new ultracentrifuge tube, and again ultracentrifuged at 110,000 g for 70 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS and subjected to a final ultracentrifugation at 110,000 g for 70 minutes at 4°C. The final pellet was resuspended in 150 μL of PBS and stored at –80°C. The protein concentration of the purified small EVs was measured using the Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Cat. No. Q33212, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.3. Western Blotting

The small EVs were solubilized in an equal volume of M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Cat. No. 78501, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and diluted with Laemmli Sample Buffer (4X) (Cat. No. 1610747, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) and PBS to achieve a final protein concentration of 30 μg/lane. The samples were incubated at 95°C for 5 minutes. The small EV lysates were subjected to electrophoresis using Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels (Cat. No. 4561094, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA), followed by transfer onto PVDF membranes (Cat. No. 1704156, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies: anti-CD9 (Cat. No. SHI-EXO-M01, COSMO BIO COMPANY, Tokyo, Japan), anti-Flotillin-1 (Cat. No. ab133497, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-CD63 (Cat. No. ab68418, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-TSG101 (Cat. No. ab125011, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-PLAP (Cat. No. ab133602, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), were incubated overnight at 4°C. Following washing with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST), the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cat. No. SA00001-2, Proteintech Group, Rosemont, IL, USA) or goat anti-mouse IgG (Cat. No. SA00001-1, Proteintech Group, Rosemont, IL, USA), for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing the membranes with TBST, Western ECL Substrate (Cat. No. 1705062, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) was added to them, and signals were detected using the Amersham Imager 680 (Cytiva, Tokyo, Japan).

4.4. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

The particle size of small EVs was measured using the Nanosight LM10 system (NTA software version: NTA 3.2 Dev Build 3.2.16). The small EVs were diluted with PBS and analyzed under the following settings: Camera Type: sCMOS, Camera Level: 14–15, Capture Time: 60 seconds, Number of Repeats: 5, Detection Threshold: 5.

4.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

A collodion-coated grid (Cat. No. 651, NISSHIN EM, Tokyo, Japan) was loaded with small EV solution, followed by negative staining using an equal volume of uranyl acetate solution (Cat. No. 336, NISSHIN EM, Tokyo, Japan). The size and morphology of the small EVs were observed using a transmission electron microscope (H-7600, Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan).

4.6. Measurement of Small EV Numbers

Small EV numbers were measured using CD9, which was identified as the most potent and reliable surface marker for plasma-derived small EVs (as described in Results). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (EXEL-ULTRA-CD9-1, System Biosciences, CA, USA). Measurements were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, plasma-derived small EVs and standard EVs (particle numbers determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis) were applied to the supplied 96-well plate, and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing the plate with Wash Buffer, CD9 primary antibody was added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The plate was washed again, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After a final wash with Wash Buffer, the Super-sensitive TMB ELISA substrate was added and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. The reaction stopped with Stop Buffer, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using the statistical software EZR, which is a graphical user interface for R (version 3.0.2). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparisons between two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis test (with Steel–Dwass post-hoc analysis) was used for comparisons among multiple groups. The p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.; methodology, R.N., H.S. and H.T.; validation, R.N. and H.S.; formal analysis, R.N., H.S., M.O., Y.S., S.T., S.N., A.O. and H.T.; investigation, R.N.; data curation, R.N. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.N. and H.T.; writing—review and editing, R.N., H.S. and H.T.; visualization, R.N., H.S. and Y.S.; supervision, T.T. and H.F.; funding acquisition, H.S., M.O., Y.S. and H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP24K12345, JP22K12000, and JP23K11111. This publication was also subsidized by JKA through its promotion funds from KEIRIN RACE.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We obtained IRB approval in our institution (number: rin25-012).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

We will open our data if there are any requests for our study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mari Matsumoto (Jichi Medical University) for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EVs |

Extracellular vesicles |

| EoPE |

Early-onset preeclampsia |

| LoPE |

Late-onset preeclampsia |

| NTA |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| HAECs |

Human aortic endothelial cells |

| HUVECs |

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| NIPT |

Non-invasive prenatal testing |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

References

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Small EV-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.K.; Zhang, H.; Becker, A.; Matei, I.; Huang, Y.; Costa-Silva, B.; Zheng, Y.; Hoshino, A.; Brazier, H.; Xiang, J.; et al. Double-stranded DNA in small EVs: A novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.L.N.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular Vesicles: Unique Intercellular Delivery Vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.; Sugiura, K.; Hoshino, A. Impact of small EV-mediated feto-maternal interactions on pregnancy maintenance and development of obstetric complications. J. Biochem. 2021, 169, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.D.; Peiris, H.N.; Kobayashi, M.; Koh, Y.Q.; Duncombe, G.; Illanes, S.E.; Rice, G.E.; Salomon, C. Placental small EVs in normal and complicated pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 213, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Min, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Linhong, M.; Tao, R.; Yan, L.; Song, H. Hypoxia-induced small EVs promote hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and metastasis via miR-1273f transfer. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 385, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Fisher, K.P.; Hammer, S.S.; Navitskaya, S.; Blanchard, G.J.; Busik, J.V. Plasma Small EVs Contribute to Microvascular Damage in Diabetic Retinopathy by Activating the Classical Complement Pathway. Diabetes. 2018, 67, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kano, M.; Akutsu, Y.; Hanari, N.; Hoshino, I.; Murakami, K.; Usui, A.; Suito, H.; Takahashi, I.; Otsuka, R.; et al. Quantification of plasma exosome is a potential prognostic marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016, 36, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Garcia, V.; Rodriguez, M.; Compte, M.; Cisneros, E.; Veguillas, P.; Garcia, J.M.; Dominguez, G.; Campos-Martin, Y.; Cuevas, J.; et al. Analysis of Small EV Release and Its Prognostic Value in Human Colorectal Cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012, 51, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.K.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, E.B.; Song, Y.W. Circulating exosomes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induce a proinflammatory immune response. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016, 18, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.; Torres, M.J.; Kobayashi, M.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Sobrevia, L.; Dobierzewska, A.; Illanes, S.E.; Mitchell, M.D.; Rice, G.E. A Gestational Profile of Placental Small EVs in Maternal Plasma and Their Effects on Endothelial Cell Migration. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e98667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.; Monteiro, L.J.; Acuna-Gallardo, S.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Rice, G.E.; Monckeberg, M.; Diaz, P.; Illanes, S.E. Extracellular vesicle concentration in maternal plasma as an early marker of gestational diabetes. Rev Med Chil. 2019, 147, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.; Guanzou, D.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Longo, S.; Correa, P.; Illanes, S.E.; Rice, G.E. Placental Exosomes as Early Biomarker of Preeclampsia: Potential Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs Across Gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017, 102, 3182–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, P.; Maharaj, N.; Moodley, J.; Mackraj, I. Placental small EVs and pre-eclampsia: Maternal circulating levels in normal pregnancies and, early and late onset pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Placenta. 2016, 46, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Hussey, H.; Saravanakumar, L.; Sinkey, R.G.; Sturdivant, A.B.; Powell, M.F.; Berkowitz, D.E. Extracellular Vesicles From Women With Severe Preeclampsia Impair Vascular Endothelial Function. Anesth Analg. 2022, 134, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, P.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Oin, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yan, Y.; et al. Association of placenta-derived extracellular vesicles with pre-eclampsia and associated hypercoagulability: A clinical observational study. BJOG. 2021, 128, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Dalirfardouel, R.; Dias, T.; Lotcall, J.; Lasser, C. Tetraspanins distinguish separate extracellular vesicle subpopulations in human serum and plasma– Contributions of platelet extracellular vesicles in plasma samples. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022, 11, e12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Kim, H.S.; Bojmar, L.; Gyan, K.E.; Cioffi, M.; Hernandez, J.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Rodrigues, G.; Molina, H.; Heissel, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle and Particle Biomarkers Define Multiple Human Cancers. Cell. 2020, 182, 1044–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, S.; Paisner, R.; Camarda, R.; Gupta, S.; Momcilovic, O.; Kohnz, R.A.; Avsaroglu, B.; L’Etoile, N.D.; Perera, R.M.; Nomura, D.K.; et al. Oncogene Regulated Release of Extracellular Vesicles. Dev Cell. 2021, 56, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebelman, M.P.; Smit, M.J.; Pegtel, D.M.; Baglio, S.R. Biogenesis and function of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 188, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, K.; Zhu, C.; Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; et al. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles as a biomarker for breast cancer diagnosis and metastasis monitoring. iScience. 2024, 27, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.H.; Quan, Y.H.; Rho, J.; Hong, S.; Park, Y.; Choi, Y.; Park, J.; Yong, H.S.; Han, K.N.; Choi, Y.H.; et al. Levels of Extracellular Vesicles in Pulmonary and Peripheral Blood Correlate with Stages of Lung Cancer Patients. World J Surg. 2020, 44, 3522–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrakopoulos, F.; Kottorou, A.E.; Rodgers, K.; Sherwood, J.T.; Koliou, G.; Lee, B.; Yang, A.; Brahmer, J.R.; Baylin, S.B.; Yang, S.C.; et al. Clinical Significance of Plasma CD9-Positive Exosomes in HIV Seronegative and Seropositive Lung Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.J.; Welton, J.; Staffurth, J.; Court, J.; Mason, M.D.; Tabi, Z.; Clayton, A. Can urinary exosomes act as treatment response markers in prostate cancer? J Transl Med. 2009, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Raimo, R.D.; Giuliani, A.; Maggi, M.; Sciarra, A.; Fais, S. Plasmatic Exosome Number and Size Distinguish Prostate Cancer Patients From Healthy Individuals: A Prospective Clinical Study. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 727317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Vizio, D.D.; Driedonks, T.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman-Gibson, S.; Chandiramani, C.; Stone, M.L.; Waker, C.A.; Maxwell, R.A.; Dhanraj, D.N.; Brown, T.L. Streamlined Analysis of Maternal Plasma Indicates Small Extracellular Vesicles are Significantly Elevated in Early-Onset Preeclampsia. Reprod Sci. 2024, 31, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, G.; Guanzon, D.; Kinhal, V.; Elfeky, O.; Lai, A.; Longo, S.; Nuzhat, Z.; Palma, C.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Menon, R.; et al. Oxygen tension regulates the miRNA profile and bioactivity of exosomes released from extravillous trophoblast cells – Liquid biopsies for monitoring complications of pregnancy. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0174514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, G.E.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Sweeney, E.; Peiris, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Duncombe, G.; Mitchell, M.D.; Salomon, C. The Effect of Glucose on the Release and Bioactivity of Exosomes From First Trimester Trophoblast Cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015, 100, E1280–E1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Diao, Z.; Yany, M.; Wu, M.; Sun, H.; Yan, G.; Hu, Y. Placenta-associated serum exosomal miR-155 derived from patients with preeclampsia inhibits eNOS expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018, 41, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Yao, J.; He, Q.; Liu, M.; Duan, T.; Wang, K. Exosomes from women with preeclampsia induced vascular dysfunction by delivering sFlt (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase)-1 and sEng (soluble endoglin) to endothelial cells. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestand, M.S.; Bessem, M.; Rijn, P.; Menezes, R.X.; Sie, D.; Bakker, I.; Boon, E.M.J.; Sistermans, E.A.; Weiss, M.M. Fetal fraction evaluation in non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPS). Eur J Hum Genet. 2019, 27, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Batey, A.; Struble, C.; Musci, T.; Song, K.; Oliphant, A. Gestational age and maternal weight effects on fetal cell-free DNA in maternal plasma. Prenat Diagn. 2013, 33, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Perez, A.; Illanes, S.E.; Mitchell, M.D.; Rice, G.E.; Salomon, C. Placenta-derived exosomes continuously increase in maternal circulation over the first trimester of pregnancy. J Transl Med. 2014, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Matsubara, K.; Nakamoto, O.; Ushijima, J.; Ohkuchi, A.; Koide, K.; Makino, S.; Mimura, K.; Morikawa, M.; Naruse, K.; et al. Outline of the new definition and classification of “Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP)”; a revised JSSHP statement of 2005. Hypertens Res Pregnancy. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).