Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

| Reference | Modeling |

|---|---|

| [19] Gonzalez-Negrete et al.(2024) | Title: Optimal planning of oil palm fruit harvest. Objective: Minimize the total costs of the fruit harvesting and transportation operation in an oil palm plantation. Decision Variables: Quantity of raw materials to be collected, lifted and transported. Constraints: Carrying capacity of transport vehicle, size of transport fleet, amount of raw material available for harvesting, market demand. |

| [30] Zhang et al.(2024) | Title: Optimization of biofuel supply chain integrated with petroleum refineries under carbon trade policy. Objective Function: Minimize total SC costs. Decision Variables: Quantity of raw materials to be transported, quantity to be produced, quantity of finished product to be transported. Constraints: Raw material supply capacity, market demand, production capacity. |

| [24] Memari et al.(2017) | Title: An optimization study of a palm oil-based regional bio-energy supply chain under carbon pricing and trading policies. Objective Function: Minimize total cost and carbon emissions. Decision Variables: Quantities to be transported and quantities to be stored. Constraints: Raw material availability, mass balance, storage capacity, reserve limit. |

| [23] Lima et al.(2017) | Title: Stochastic programming approach for the optimal tactical planning of the downstream oil supply chain. Objective Function: Maximize profit. Decision Variables: Import and export costs, Inventory costs, Transportation costs, Inventory quantity, Supply cost, Product quantities processed, Quantity of product exported and imported. Constraints: Processing capacity, Mass balance, Storage capacity, Demand. |

| [18] Ghaithan et al.(2017) | Title: Multi-objective optimization (downstream level) of the oil and gas supply chain. Objective Function: Minimize total supply chain cost and maximize total revenue and service level. Decision Variables: Quantities to produce, Quantities to transport, Inventory levels, Service levels. Constraints: Mass balances, Production capacities, Capacities on each route, Demands, Service Levels, OPEC Quotas. |

| [17] García-Cáceres et al.(2015) | Title: Tactical optimization of the oil palm agribusiness supply chain. Objective: Minimize the operating costs of harvesting and extracting palm oil products. Decision Variables: Material to be transported between the plots and the collection center, Quantity of raw material stored in the plant, Quantity of product stored in the plant, Quantity to be produced, Plant production capacity, Product and raw material storage capacities, Number and type of vehicles used for transport, Number of trips made by each type of vehicle, Number of work teams per zone, Number and type of vehicles, setup (binary). Constraints: Available supply over the planning horizon, Mass balance for each SC node, Production capacity, Storage capacity, Distribution capacity, Distribution infrastructure (in-house and outsourced), Production start-up. |

| [28] Rincón et al.(2015) | Title: Optimization of the Colombian biodiesel supply chain from oil palm crop based on techno-economical and environmental criteria. Objective Function: Minimize total system costs and SC emissions. Decision Variables: Quantity of material flow for each route. Constraints: Biodiesel plant capacity, Biodiesel demand, Quantity of palm oil obtained, Costs. |

| [2] Alfonso-Lizarazo et al.(2013) | Title: Modeling reverse logistics process in the agroindustrial sector: The case of the palm oil supply chain. Objective Function: Maximize the profits obtained from the system. Decision Variables: Quantity in tons of bunches shipped from each hectare of each crop in each vehicle, Quantity in tons of potash shipped from each hectare of each crop in each vehicle, Quantity in tons of fertilizer shipped from each hectare of each crop in each vehicle, Flow between stages of the chain at each harvest, Final inventory at each stage of the chain and at each harvest. Constraints: Flow balance, Capacity, Material balance, Steam demand of each crop, Energy demand of each crop, Inventory balance, Balance of potash and fertilizer, Transport capacity. |

| [4] Avami (2012) | Title: A model for biodiesel supply chain: A case study in Iran. Objective Function: Minimize total SC costs. Decision Variables: Quantity of raw material, Quantity of product to be produced, Quantity of product to be transported. Constraints: Mass balance, Demand, Production capacity. |

| [26] Papapostolou et al.(2011) | Title: Development and implementation of an optimization model for biofuels supply chain. Objective Function: Maximization of the total utility of the chain. Decision Variables: Quantity of production from each grower in each climate scenario, Quantity transported from each grower to the central plant, at each point in time, from each type of storage, in each climate scenario, Capacity of each type of storage, in each time period, from each grower, in each climate scenario, Excess outdoor storage capacity, Shortfall in biomass sent to the central plant. Constraints: Biodiesel demand, Land available for cultivation, Production capacity, Water use, Storage of feedstock and finished product. |

| [9] Cundiff et al.(1997) | Title: A linear programming approach for designing a herbaceous biomass delivery system. Objective Function: Minimization of total supply chain costs. Decision Variables: Biomass flow in the chain at each point in time, Capacity of each type of storage (covered and open storage), Quantity of excess and shortage of biomass. Constraints: Production capacity, Demand, Storage. |

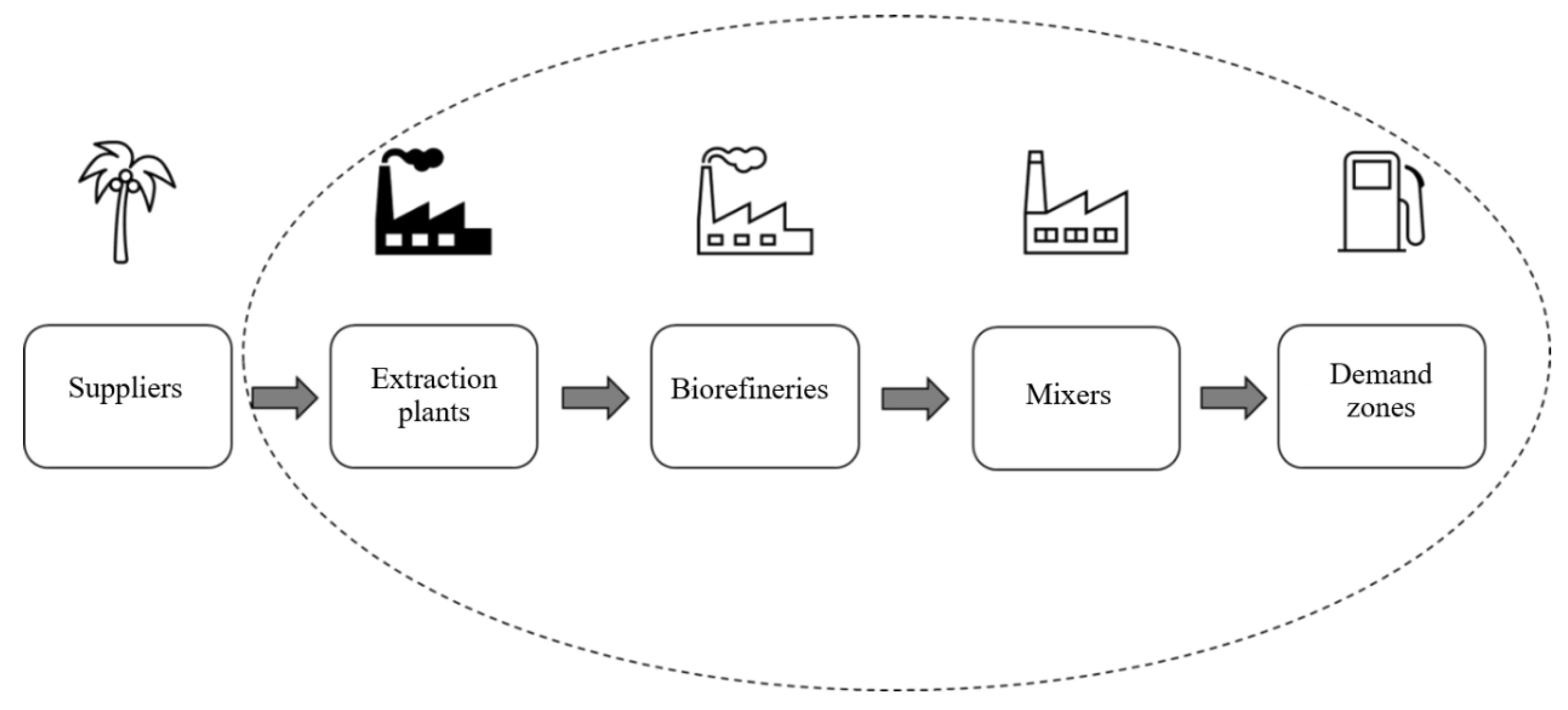

3. Research Methodology

4. The Model

5. Solution Procedure

5.1. Valid Inequalities

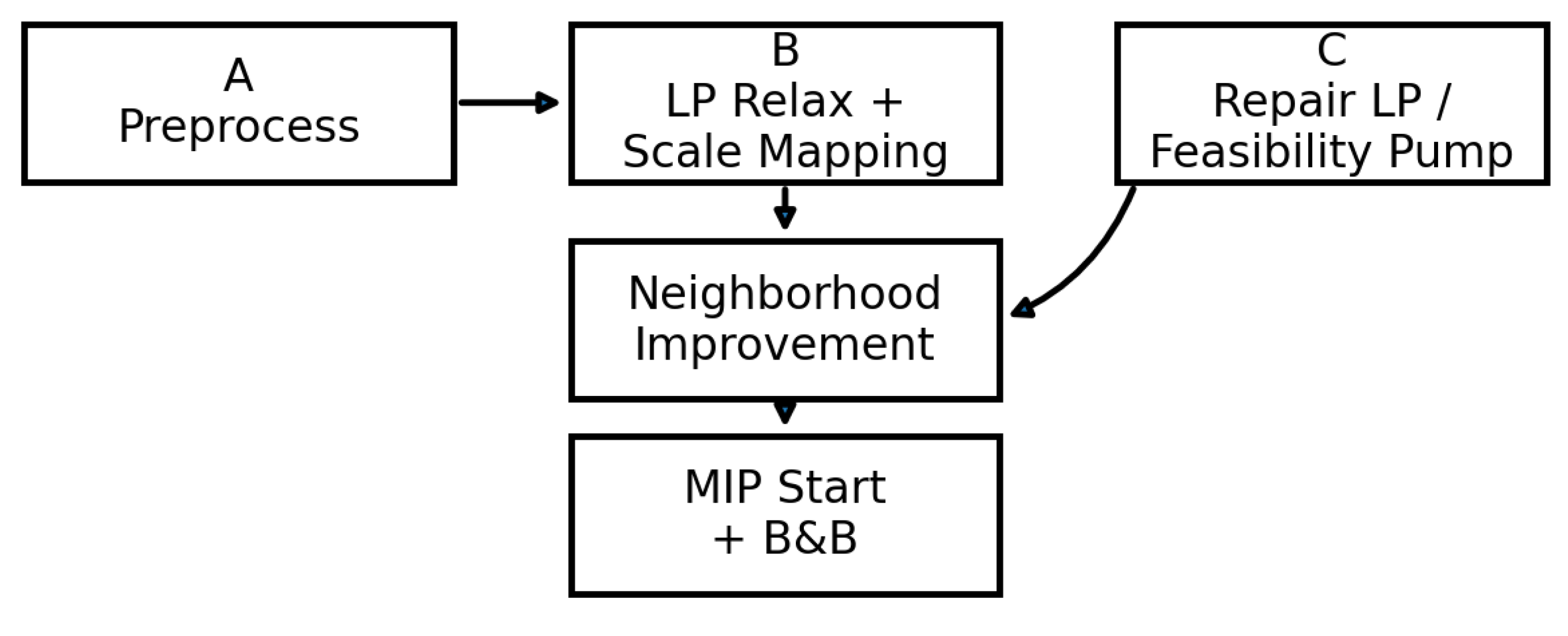

5.2. Proposed Warm-Start Solution Procedure

- WS-PalmBiodiesel():;

- A) PreprocessAndTighten();

- Compute tight big-M or replace with SOS1/indicator constraints;

- Remove dominated arcs and tighten flow bounds by supply-demand balances;

- B) (x̄,ȳ,z̄,h̄) ← SolveContinuousRelaxation (with VI);

- w* ← MapScalesGreedyMonotone (throughputs from x̄,ȳ,z̄,h̄);

- C) (x*,y*,z*,h*) ← RepairLPGivenScales(w*);

- if infeasible:;

- (w*,x*,y*,z*,h*) ← FeasibilityPumpRestrictedTo(w) → RepairLP;

- D) Incumbent ← (w*,x*,y*,z*,h*);

- LoadAsMIPStart(Incumbent);

- ImproveByFixAndOptimize(Blocks);

- LocalBranching(k);

- RINS();

- return Incumbent;

| Symbol | Description | Type | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMAX* | Maximum throughput at scale e | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| GMIN* | Minimum throughput at scale e | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| CAPP* | Facility capacity (resource units/period) | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| FIS* | Safety stock factor | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| H | Inventory holding fraction | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| CT* | Initial transport cost | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| CI* | Inventory cost | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| CSOLB | Surplus penalty | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| CFLB | Shortage penalty | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| PLB | Selling price at demand zone | Parameter | ℝ₊ |

| x,y,z,h | Flows between stages | Variable | ℝ₊ |

| w | Scale-activation binaries | Variable | {0,1} |

| g⁺, g⁻ | Surplus / shortage | Variable | ℝ₊ |

6. Solution and Results

Network Sparsity with Cost-Driven Routing

Scale Activation Consistent with Throughput

Mass-Balance Coherence and Capacity Discipline

Service Levels Priced By Penalty Terms

Managerial Takeaway

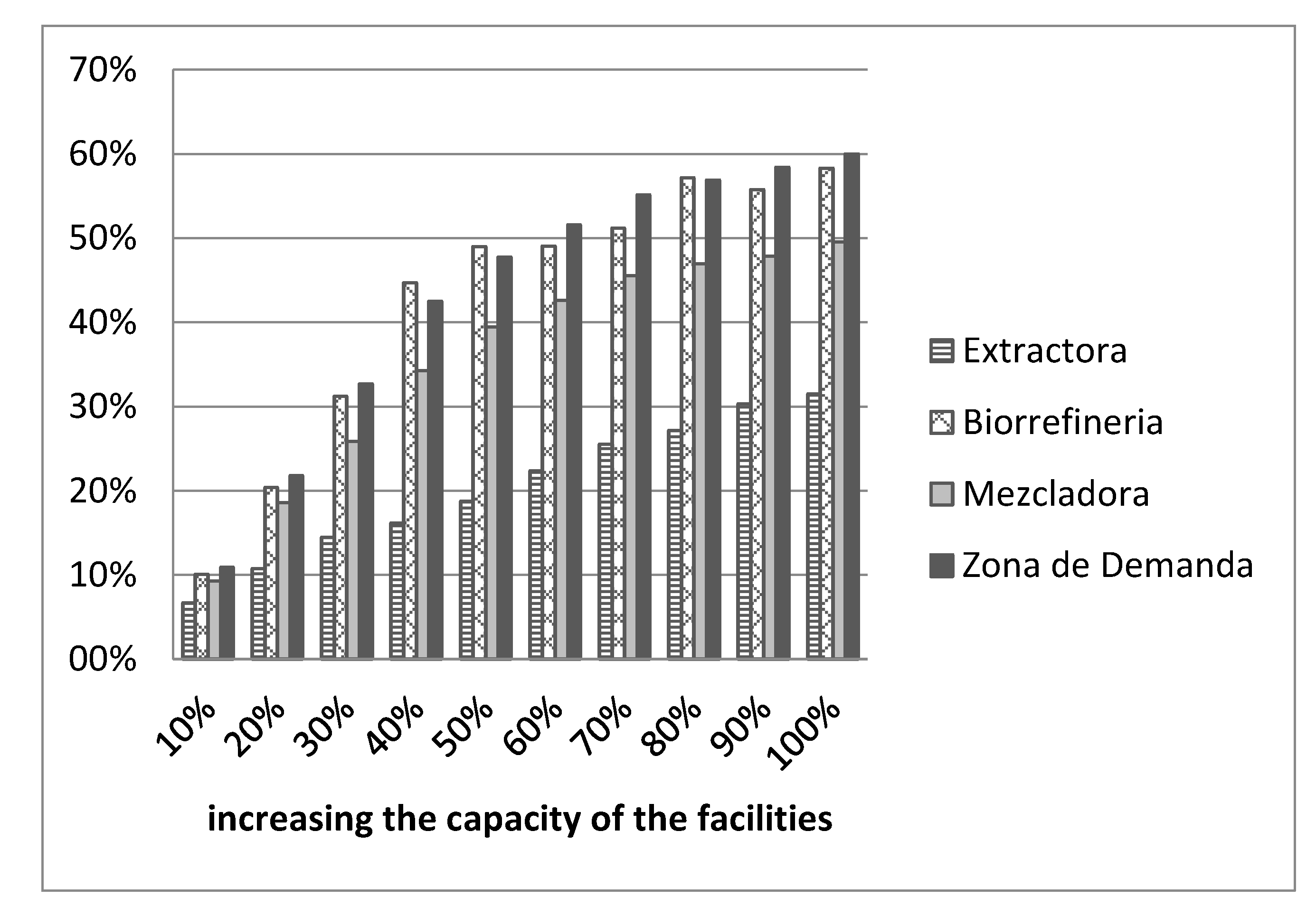

Sensitivity Analysis

Impact of Revenues on Profits

Impact of Capacities on Profits

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| xij1 : Quantity of the item supplied by supplier i to extractor j. | yjq1 : Quantity of the item supplied by extractor j to biorefinery q. | ||||||

| i j | 1 | 2 | 3 | j q | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 648 | 0 | 1008 | 1 | 100.666667 | 268 | 387 |

| 1 | 648 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 573.269231 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 186 | 93 | 0 |

| 1 | 398.333333 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 223 |

| 1 | 0 | 703 | 0 | 2 | 355 | 290.140276 | 301 |

| 2 | 896 | 776.333333 | 610.666667 | 2 | 283.790293 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 517.249784 | 987 | 847 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 428.884615 | 847 | 2 | 325.809707 | 0 | 50.7692308 |

| 2 | 896 | 987 | 847 | 3 | 279 | 0 | 310 |

| 2 | 189.052414 | 0 | 157.319081 | 3 | 43.25 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 361.333333 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 866 | 830 | 680 | 3 | 0 | 242.384615 | 0 |

| 3 | 866 | 0 | 270.019231 | 4 | 216.37381 | 307.333333 | 211 |

| 3 | 0 | 830 | 140 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 151 |

| 3 | 866 | 786.779687 | 680 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 186 |

| 4 | 0 | 768 | 0 | 4 | 158.959524 | 0 | 211 |

| 4 | 830 | 754.109507 | 369.649784 | 5 | 285.733333 | 231.752581 | 347 |

| 4 | 0 | 768 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 163.520147 | 176.040293 |

| 4 | 830 | 0 | 762 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 830 | 0 | 762 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| zqk1: Quantity of the item supplied by biorefinery q to blender k. | hkl1: Quantity of item supplied by blender k to demand zone l. | ||||||

| q k | 1 | 2 | 3 | k l | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 89.289281 | 78.4297603 | 146 | 1 | 89.289281 | 78.4297603 | 146 |

| 1 | 0 | 58.7964302 | 108.335402 | 1 | 0 | 58.7964302 | 108.335402 |

| 1 | 89 | 182 | 26.1491268 | 1 | 89 | 182 | 26.1491268 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 163.520147 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 163.520147 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 93 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 93 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 68.0538887 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 174.330727 | ||||

| xij1 : Item supplied by supplier i to extraction plant j | ||||

| i j | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 524.17033 | 972 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1057 | 0 |

| 1 | 1084 | 710 | 1057 | 0 |

| 1 | 1084 | 0 | 0 | 972 |

| 1 | 1084 | 0 | 0 | 972 |

| 2 | 1084 | 0 | 0 | 972 |

| 2 | 0 | 1077 | 860 | 0 |

| 2 | 816 | 1077 | 0 | 731 |

| 2 | 213.448718 | 340.294872 | 0 | 731 |

| 2 | 0 | 1077 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 798.317682 | 1077 | 860 | 731 |

| 3 | 0 | 377.142523 | 860 | 731 |

| 3 | 747 | 0 | 670 | 203.17033 |

| 3 | 668.619048 | 862 | 670 | 647 |

| 3 | 747 | 862 | 8.49358974 | 647 |

| 4 | 414.356422 | 862 | 670 | 647 |

| 4 | 747 | 862 | 0 | 647 |

| 4 | 0 | 862 | 670 | 647 |

| 4 | 352.131868 | 570.802198 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 150.904762 | 0 | 78.4047619 |

| 5 | 725 | 987 | 1094 | 519.49359 |

| 5 | 725 | 319.773089 | 1094 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 987 | 956.960539 | 83.9605395 |

| 5 | 385.356878 | 987 | 216.642593 | 0 |

| 5 | 845 | 951 | 0 | 879 |

| 6 | 845 | 951 | 608.404762 | 879 |

| 6 | 0 | 951 | 617 | 879 |

| 6 | 0 | 951 | 482.558803 | 627.558803 |

| 6 | 0 | 400.096903 | 617 | 0 |

| 6 | 845 | 951 | 617 | 13.6425927 |

| yjq1 : Item supplied by extractor j to biorefinery q | ||||

| j q | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 45.4844322 | 213 | 54.3461538 |

| 1 | 262.384615 | 186.801282 | 119.384615 | 258 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 86.6666667 | 120.5 |

| 2 | 0 | 160 | 160 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 223.285714 | 168 | 0 | 257 |

| 2 | 160 | 0 | 185 | 0 |

| 2 | 345 | 236 | 166.820763 | 218 |

| 2 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 103.846154 | 236 | 235.679237 | 218 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.80128205 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 160 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 309 | 311 | 245 | 181.214286 |

| 4 | 55.4166667 | 311 | 32.2555921 | 0 |

| 4 | 160 | 204.560356 | 0 | 166.5 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 239.142857 | 93.0760073 | 0 | 214 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 371.769231 | 214 |

| 5 | 0 | 268.499931 | 102.785617 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 286.285714 | 308 | 386 | 237 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| zqkb : Item supplied by biorefinery q to blender k | ||||

| q k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 95.3394659 | 0 | 40.0061325 | 1.74290293 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 108.720821 | 0 | 108.720821 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 160 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 110.339466 | 235.333333 | 160 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 43.1126649 | 0 | 108.720821 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 20 | 165 | 0 | 113.596563 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 65.6081562 | 0 | 0 |

| hkl1 : Item supplied by blender k to demand zone l | ||||

| k l | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.3110181 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 2 | 0 | 235 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 8.02844774 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 108.720821 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| xij1 : Item supplied by supplier i to extraction plant j | |||||

| i j | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 715 | 1053 | 771 | 925 | 744 |

| 1 | 0 | 1053 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1053 | 771 | 925 | 744 |

| 1 | 0 | 1053 | 771 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 744 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 771 | 925 | 744 |

| 2 | 648 | 0 | 965 | 433.172339 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 965 | 1059 | 918 |

| 2 | 648 | 862 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 648 | 0 | 965 | 0 | 918 |

| 2 | 0 | 862 | 0 | 535.154157 | 650.808858 |

| 2 | 648 | 862 | 0 | 331.638678 | 0 |

| 3 | 783 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 333.229096 | 126.610948 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 546.423878 | 830 | 0 | 735.346955 |

| 3 | 783 | 429.824361 | 830 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 760.799767 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 922 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 191.226729 | 0 | 778 | 0 | 759 |

| 4 | 653 | 0 | 637.902637 | 525.166504 | 759 |

| 4 | 653 | 0 | 28.9246796 | 1029 | 0 |

| 4 | 539.252933 | 645 | 0 | 1029 | 759 |

| 4 | 653 | 0 | 778 | 1029 | 0 |

| 4 | 240.744687 | 0 | 586.483977 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 973 | 0 | 0 | 654.999689 |

| 5 | 835 | 973 | 986 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 556.423878 | 0 | 986 | 859.346955 | 1034 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 337.220151 | 1016 | 384.824361 |

| 5 | 0 | 973 | 986 | 1016 | 0 |

| 5 | 835 | 208.638678 | 0 | 0 | 1034 |

| 6 | 0 | 36.3056721 | 175.305672 | 1066 | 0 |

| 6 | 657 | 0 | 0 | 1066 | 675.451319 |

| 6 | 657 | 0 | 1002 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 410.824361 | 0 |

| 6 | 657 | 211.054157 | 979.226807 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 657 | 809 | 1002 | 1066 | 392.742888 |

| yjq1 : Item supplied by extractor j to biorefinery q | |||||

| j q | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 281 | 266.17265 | 0 | 261.866667 | 207 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 213 | 100 | 207 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 260.093706 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 200 | 0 | 100 | 209 | 0 |

| 2 | 154.333333 | 0 | 0 | 209 | 172 |

| 2 | 269 | 297.715185 | 0 | 0 | 162.94639 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.5555556 | 1.34529915 |

| 3 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 204.930527 |

| 3 | 353 | 100 | 289 | 113.133333 | 200 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 253.570275 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 238.789744 | 209 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 251.89579 | 155.900834 | 0 |

| 4 | 209 | 394 | 200 | 171 | 323.5 |

| 4 | 27.4285714 | 0 | 0 | 1.0991661 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 163 |

| 5 | 169.011966 | 0 | 271.17265 | 312 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 222.1 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 119.078943 | 263.345299 | 100 | 0 | 163 |

| 6 | 0 | 151.89579 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 354 | 0 | 0 | 243 | 261.5 |

| 6 | 299.001799 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 218.345299 | 0 | 0 |

| zqkb : Item supplied by biorefinery q to blender k | |||||

| q k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 112.930527 | 13.005044 | 3.02969272 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 89.3094017 | 112 | 0 | 148 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 49.1726496 | 98.3452991 | 0 | 98.3452991 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 110 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 72.2312044 | 119.68244 | 56.6288914 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49.1726496 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 49.1726496 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 55 | 0 |

| hkl1: Item supplied by blender k to demand zone l | |||||

| k l | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67.9166016 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 10.6160809 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.99386503 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.03598485 |

| 1 | 6.75191327 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49.1726496 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| xij1: Item supplied by supplier i to extraction plant j | ||||||

| i j | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

6 |

| 1 | 745 | 670 | 0 | 946 | 708 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 670 | 0 | 946 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 670 | 0 | 946 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 670 | 746.85 | 946 | 0 | 986 |

| 1 | 181.93 | 670 | 0 | 83.282 | 708 | 986 |

| 1 | 745 | 0 | 758 | 946 | 0 | 986 |

| 1 | 745 | 0 | 0 | 946 | 0 | 635.24 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 366.33 | 930 | 0 | 939 | 945 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 945 | 218.9 |

| 2 | 0 | 930 | 799 | 472.62 | 532.73 | 0 |

| 2 | 1014 | 930 | 799 | 939 | 0 | 952 |

| 2 | 1014 | 930 | 799 | 0 | 945 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 930 | 0 | 939 | 0 | 952 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 956 | 0 | 729 | 826 |

| 3 | 847 | 28.731 | 956 | 0 | 729 | 826 |

| 3 | 847 | 0 | 613.9 | 775 | 0 | 826 |

| 3 | 847 | 873 | 0 | 775 | 729 | 0 |

| 3 | 847 | 873 | 0 | 775 | 729 | 0 |

| 3 | 847 | 873 | 956 | 775 | 0 | 826 |

| 3 | 0 | 873 | 956 | 775 | 729 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 784 | 869 | 907 | 655 | 1057 |

| 4 | 614 | 784 | 869 | 656.73 | 0 | 998.4 |

| 4 | 614 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 655 | 0 |

| 4 | 614 | 0 | 869 | 907 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 869 | 907 | 0 | 905.78 |

| 4 | 0 | 784 | 0 | 0 | 655 | 599.38 |

| 4 | 426.77 | 185.9 | 0 | 907 | 655 | 1057 |

| 5 | 802.29 | 875.29 | 0 | 0 | 69.29 | 130 |

| 5 | 856 | 1081 | 960 | 804 | 0 | 734 |

| 5 | 244.03 | 1081 | 960 | 0 | 0 | 734 |

| 5 | 177.73 | 587.19 | 0 | 804 | 608 | 734 |

| 5 | 856 | 1081 | 0 | 0 | 403.93 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 1081 | 0 | 804 | 0 | 734 |

| 5 | 856 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 614 | 0 | 36.003 | 322.65 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 614 | 846 | 120.26 | 0 | 565.33 | 0 |

| 6 | 614 | 846 | 623 | 665.81 | 0 | 613 |

| 6 | 614 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 405.85 |

| 6 | 0 | 771.86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 432.98 | 677.62 | 261.95 | 477.83 | 792 | 0 |

| 6 | 614 | 846 | 429.45 | 9.544 | 792 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 778 | 0 | 1095 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1095 | 1058 | 679 |

| 7 | 0 | 648.81 | 0 | 1095 | 719.03 | 0 |

| 7 | 675 | 778 | 0 | 0 | 1058 | 679 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 877.78 | 1095 | 1058 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1095 | 646.98 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 778 | 991 | 0 | 465.77 | 0 |

| yjq1: Item supplied by extractor j to biorefinery q | ||||||

| j q | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 152 | 0 | 152 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 209.94 | 0 | 0 | 97.215 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 110.36 | 0 | 394 |

| 1 | 106.64 | 130.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 265 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 133.43 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 258.22 | 258.22 | 161 | 0 |

| 2 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 152.33 | 201 | 73.92 | 327.36 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 256 | 0 | 0 | 18.824 | 0 | 262 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 152 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 170.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 368.13 | 180 | 0 | 152 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 152 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 195 | 0 | 0 | 236 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 120.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76 |

| 4 | 77.215 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 303 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 390 | 74.538 | 177 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 301.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 240.93 | 0 | 181 | 237 | 101.43 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 195 | 195.8 | 0 | 163 | 375 | 93.353 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 90.282 | 108.13 | 0 | 130.07 |

| 5 | 45 | 210 | 207.72 | 0 | 375 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 86.286 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 152 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77.431 |

| 6 | 155.58 | 300.57 | 0 | 118 | 278 | 0 |

| 6 | 138.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 130.07 | 0 |

| 6 | 45.527 | 0 | 0 | 328 | 0 | 49.854 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 370.43 | 0 | 0 | 185 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 181 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 22.982 | 228 | 222 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 39.786 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 181 | 32.573 | 0 | 0 | 280.36 | 244 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 83.538 | 187.22 | 0 | 226 | 0 | 0 |

| zqk1: Item supplied by biorefinery q to blender k | ||||||

| q k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 122.22 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 134.81 | 0 | 212 | 130.65 | 9.8952 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 130.07 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 66.215 | 69.704 | 68 | 178.72 | 13 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 178 | 0 | 68.515 | 0 | 0 | 55.397 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| hkl1: Item supplied by blender k to demand zone l | ||||||

| k l | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

6 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 6.4189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 145.92 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 9.156 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 9.8688 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

References

- T. Achterberg, “SCIP: Solving constraint integer programs,” Mathematical Programming Computation, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–41, 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Alfonso-Lizarazo, J. E. Alfonso-Lizarazo, J. Montoya-Torres, and E. Gutiérrez-Franco, “Modeling reverse logistics process in the agroindustrial sector: The case of the palm oil supply chain,” Applied Mathematical Modelling, vol. 37, no. 23, pp. 9652–9664, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. An, W. H. An, W. Wilhelm, and S. Searcy, “Biofuel and petroleum-based fuel supply chain research: A literature review,” Biomass and Bioenergy, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Avami, “A model for biodiesel supply chain: A case study in Iran,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 4196–4203, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Balat, “Potential alternatives to edible oils for biodiesel production – A review of current work,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 1479–1492, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Berthold, “Measuring the impact of primal heuristics,” Operations Research Letters, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 611–614, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Cortés V., D. R. A. Cortés V., D. Moreno, D. Albornoz, and A. Poveda, Análisis del impacto de la política de Biocombustibles. R. S. Arboleda, Ed., Revista Civilizar, pp. 81–96, 2012.

- Council of Supply Chain Management Professional, “SCM Concepts,” [Online]. Available: http://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Join/About_Us/CSCMP/Join/About_Us.aspx?hkey=e15eb27f-d327-4ef3-89f9-2ade73e34a55. Accessed: 2016.

- J. Cundiff, N. J. Cundiff, N. Dias, and H. Sherali, “A linear programming approach for designing a herbaceous biomass delivery system,” Bioresource Technology, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 47–55, 1997. [CrossRef]

- E. Danna, E. E. Danna, E. Rothberg, and C. Le Pape, “Exploring relaxation induced neighborhoods to improve MIP solutions,” Mathematical Programming, vol. 102, no. 1, pp. 71–90, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Denton, Strategic supply chain management: Creating value in planning semiconductor supply chains. University of Michigan, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://btdenton.engin.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/138/2015/08/Denton-2006.

- DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Documento CONPES 3510. Bogotá, D.C., 2008. [Online]. Available: https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Sinergia/Documentos/Evaluacion_Biocombustibles_Conpes_3510_Documento.

- Fedebiocombustibles, “Federación nacional de biocombustibles en Colombia,” [Online]. Available: http://www.fedebiocombustibles.com/nota-web-id-2484.htm. Accessed: Nov. 15, 2017.

- Fedebiocombustibles, “Federación nacional de biocombustibles en Colombia,” [Online]. Available: https://fedebiocombustibles.com/statistics/#.

- M. Fischetti, F. M. Fischetti, F. Glover, and A. Lodi, “The feasibility pump,” Mathematical Programming, vol. 104, no. 1, pp. 91–104, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Franco, A. Flórez, and M. Ochoa, “Análisis de la cadena de suministro de biocombustibles en Colombia,” Revista de Dinámica de Sistemas, no. 4, pp. 109–133, 2008.

- R. García-Cáceres, M. R. García-Cáceres, M. Martínez-Avella, and F. Palacios-Gómez, “Tactical optimization of the oil palm agribusiness supply chain,” Applied Mathematical Modelling, vol. 39, no. 20, pp. 6375–6395, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghaithan, A. A. M. Ghaithan, A. A. Salih, and O. Duffuaa, “Multi-objective optimization model for a downstream oil and gas supply chain,” Applied Mathematical Modelling, vol. 52, pp. 689–708, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Gonzalez-Negrete, R. G. T. Gonzalez-Negrete, R. G. García-Cáceres, and J. W. Escobar-Velásquez, “Optimal planning of oil palm fruit harvest,” International Journal of Services and Operations Management, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 311–340, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Franco, A. Polo, N. Clavijo-Buritica, and L. Rabelo, “Multi-objective optimization to support the design of a sustainable supply chain for the generation of biofuels from forest waste,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 14, p. 7774, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. E. Huang, Y. Y. E. Huang, Y. Fan, and C. Chen, “An integrated biofuel supply chain to cope with feedstock seasonality and uncertainty,” Transportation Science, vol. 48, pp. 1–15, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Koch et al., “MIPLIB 2010: Mixed integer programming library version 5,” Mathematical Programming Computation, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 103–163, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Lima, S. Relvas, and A. Barbosa-Póvoa, “A stochastic programming approach for the optimal tactical planning of the downstream oil supply chain,” Computers & Chemical Engineering, vol. 108, pp. 314–336, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Memari, R. Ahmad, A. Rahim, and M. Akbari, “An optimization study of a palm oil-based regional bio-energy supply chain under carbon pricing and trading policies,” Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, vol. 20, pp. 113–125, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Orjuela, I. J. C. Orjuela, I. Huertas, J. Figueroa, D. Kalenatic, and K. Katerine, “Potencial de producción de Bioetanol a partir de Caña Panelera: dinámica entre contaminación, seguridad alimentaria y uso del suelo,” Revista Facultad de Ingeniería Universidad Distrital, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 6–26, 2011.

- Papapostolou, E. Kondili, and J. Kaldellis, “Development and implementation of an optimisation model for biofuels supply chain,” Energy, vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 6019–6026, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Ralphs, “Improving the performance of branch-and-cut solvers through warm starting,” in Proc. INFORMS Annu. Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://coral.ise.lehigh.edu/~ted/files/talks/INFORMS07.

- L. Rincón, M. L. Rincón, M. Valencia, V. Hernández, L. Matallana, and C. Cardona, “Optimization of the Colombian biodiesel supply chain from oil palm crop based on techno-economical and environmental criteria,” Energy Economics, vol. 47, pp. 154–167, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Wolsey, Integer Programming. New York, NY: Wiley, 1998.

- W. Zhang, Y. W. Zhang, Y. Luo, and X. Yuan, “Optimization of biofuel supply chain integrated with petroleum refineries under carbon trade policy,” Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering, vol. 18, no. 3, p. 34, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Model type | Supply chain scope | Objective | Novelty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [21] | MIP | Upstream + Mid-stream | Minimize cost | Includes seasonal supply modeling |

| Zhang et al. [30] | Simulation + LP | Downstream | Maximize service level | Real-time blending dynamics |

| Gutiérrez et al. [20] | Simulation + LP | Downstream | Maximize service level | Real-time blending dynamics |

| This study | MIP with VI | Midstream + Down-stream | Maximize net profit | Tactical integration with economies of scale |

| Instance 1 | Instance 2 | Instance 3 | Instance 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of palm fruit suppliers i | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Number of CPO extractors j | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Number of diesel biorefineries q | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Number of blenders k | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Number of demand zones l | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of scales in j | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of scales in q | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of scales in k | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of items or products in i | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of items or products in j | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of items or products in q | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of items or products in k | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of items or products in l | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Instance 1 | Instance 2 | Instance 3 | Instance 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective function value | 1,227,762 | 1,558,010 | 1,182,420 | 1,301,439 |

| Total Variables | 814 | 2,272 | 3,823 | 6,273 |

| Binary Variables | 288 | 900 | 1,530 | 2,520 |

| Number of constraints (not including non-negativity constraints) | 1,376 | 3,405 | 5,689 | 17,704 |

| Memory used (KB) | 326 | 762 | 1,278 | 2,899 |

| LP Iterations | 15,692 | 860,866 | 21,359,983 | 47,366,532 |

| Nodes explored (×103) — Baseline: | 0.191 | 13.786 | 218.940 | 650.025 |

| Final MIP gap (%) — Baseline: | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Seeded MIP start (Y/N) — Baseline: | N | N | N | N |

| Nodes explored (×103) — Warm start: | 0.150 | 9.650 | 157.600 | 487.500 |

| Final MIP gap (%) — Warm start: | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SD (Warm start) | 0.010 | 0.450 | 7.500 | 20.000 |

| Seeded — Warm start (Y/N): | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| TTFF (s) - Baseline | 4 | 20 | 900 | 1,800 |

| TTFF (s) - Warm Start | 1 | 6 | 315 | 720 |

| TTFF - Reducción (%) | 75 | 70 | 65 | 60 |

| TTFF (s) - SD Warm Start * | 0.3 | 1.0 | 45 | 90 |

| CPU (s) - Baseline | 6 | 62 | 2,759 | 10,153 |

| CPU (s) - Warm Start | 5 | 50 | 2,200 | 8,000 |

| CPU - Reducción (%) | 16.7 | 19.4 | 20.2 | 21.2 |

| CPU (s) - SD Warm Start * | 5 | 7 | 45 | 80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).