Introduction

Context and Justification

Cocoa production is a fundamental economic driver in numerous tropical regions, including the Dominican Republic, which is one of the world’s leading producers of organic cocoa, accounting for 60% of global export volume (CERAI, 2024; Ambiente.gob.do, 2025). However, this sector faces significant challenges such as soil degradation, aging farmers, intensive agrochemical use, and climate change (ICCO, 2023; Codespa, 2024).

Agroecology, integrating sustainable production practices based on biodiversity, integrated pest management, and soil conservation, has been proposed as a viable alternative to reverse productivity loss and promote sustainable local economies (Altieri, 2020; Gliessman, 2015). National and international projects in mountainous regions of the Dominican Republic have demonstrated significant gains in productivity and profitability through agroecological principles, highlighting ecosystem improvement and social inclusion (CERAI, 2024; Codespa, 2024).

Study Objectives

To design a pilot model for agroecological conversion adapted to cocoa farms.

To evaluate productivity, quality, and soil fertility during the transition.

To measure environmental benefits, including biodiversity and the reduction of agrochemicals.

To analyze the perception and acceptance of participating producers.

Theoretical Framework

Key Concepts of Agroecology

Agroecology integrates scientific and traditional knowledge to promote sustainability through diversification, nutrient recycling, fostering biodiversity, and integrated pest management (Gliessman, 2015). In cocoa, it promotes agroforestry systems that optimize ecological synergies, improve resilience, and enhance product quality (Lotter, 2003).

Importance of Cocoa in Agriculture

Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) is a strategic crop with economic and environmental impact. Produced in agroforestry systems, it contributes to the conservation of biodiverse landscapes and ecosystem functions (ICCO, 2023). The sustainability of its production is vital for rural development and international markets.

National Background

In the Dominican Republic, the Cacao Trace Project, funded by the European Union, promotes sustainability through innovative technologies and models benefiting 700 small producers (Codespa, 2024). Additionally, CONACADO has led the transition towards agroforestry and organic systems with experiences of recovering degraded farms, showing clear benefits in productivity and cocoa quality (CONACADO, 2025; SICACAO, 2022). For decades, these efforts have revalued organic cocoa as a strategic product for rural development and environmental conservation, especially in traditional cocoa regions such as Monte Plata (Ferreiras, 2020).

International Background

Globally, agroecological cocoa production is established in countries like Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Mexico, where diversification and integrated management have helped mitigate climate change effects while improving product quality (Méndez et al., 2019). Agroecology in cocoa fosters resilience, reduces chemical inputs, and conserves biodiversity, aligning with FAO and UN Sustainable Development Goals (Altieri, 2020; Lotter, 2003).

Methodology

Pilot Model Design

A pilot model was implemented including initial agroecological diagnosis, participatory training, progressive execution of agroecological practices (diversification, integrated pest management, shade control, and soil rehabilitation), and monitoring productive and environmental indicators. Ten representative farms linked to CONACADO were selected based on commitment and historical data. Data were collected through semi-structured surveys, productivity measurement (kg/ha wet and dry cocoa), physical-chemical and biological soil analysis, biodiversity assessment (tree diversity and beneficial insects), monthly visits, and semiannual evaluations.

Selection of Farms and Participants

Ten pilot farms were selected in representative cocoa-growing areas linked to CONACADO, with an interest in and commitment to adopting agroecological practices and historical records for comparison.

Data Collection Techniques

Semi-structured surveys to understand producer perception.

Measurement of productivity in kg/ha (wet and dry cocoa).

Physical-chemical and biological soil analysis.

Biodiversity assessment (tree diversity and beneficial insects).

Monthly visits and semi-annual evaluations.

Results

Impact on Productivity

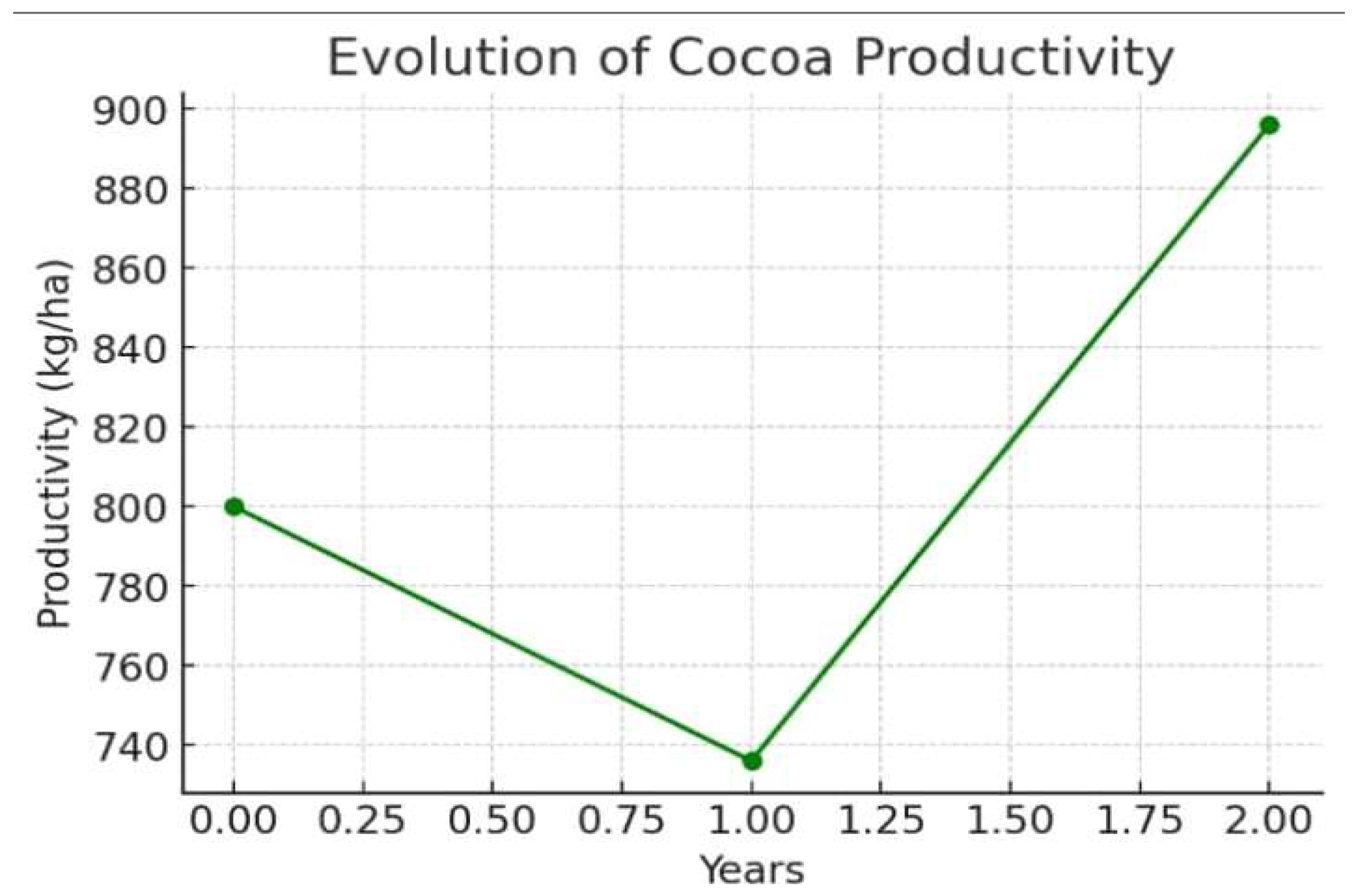

Table 1 shows a typical transition phase in agroecological systems. The initial productivity of 800 kg/ha dropped by 8% in the first year (736 kg/ha). This is an expected outcome, as the soil and plants adjust to the reduction of chemical inputs and changes in management practices. The recovery and growth are seen in the second year, with a 12% increase above the baseline (896 kg/ha), which highlights the resilience and long-term superiority of these systems compared to conventional ones. This “learning curve” pattern is an important factor for producers to consider during the transition phase.

Environmental Benefits

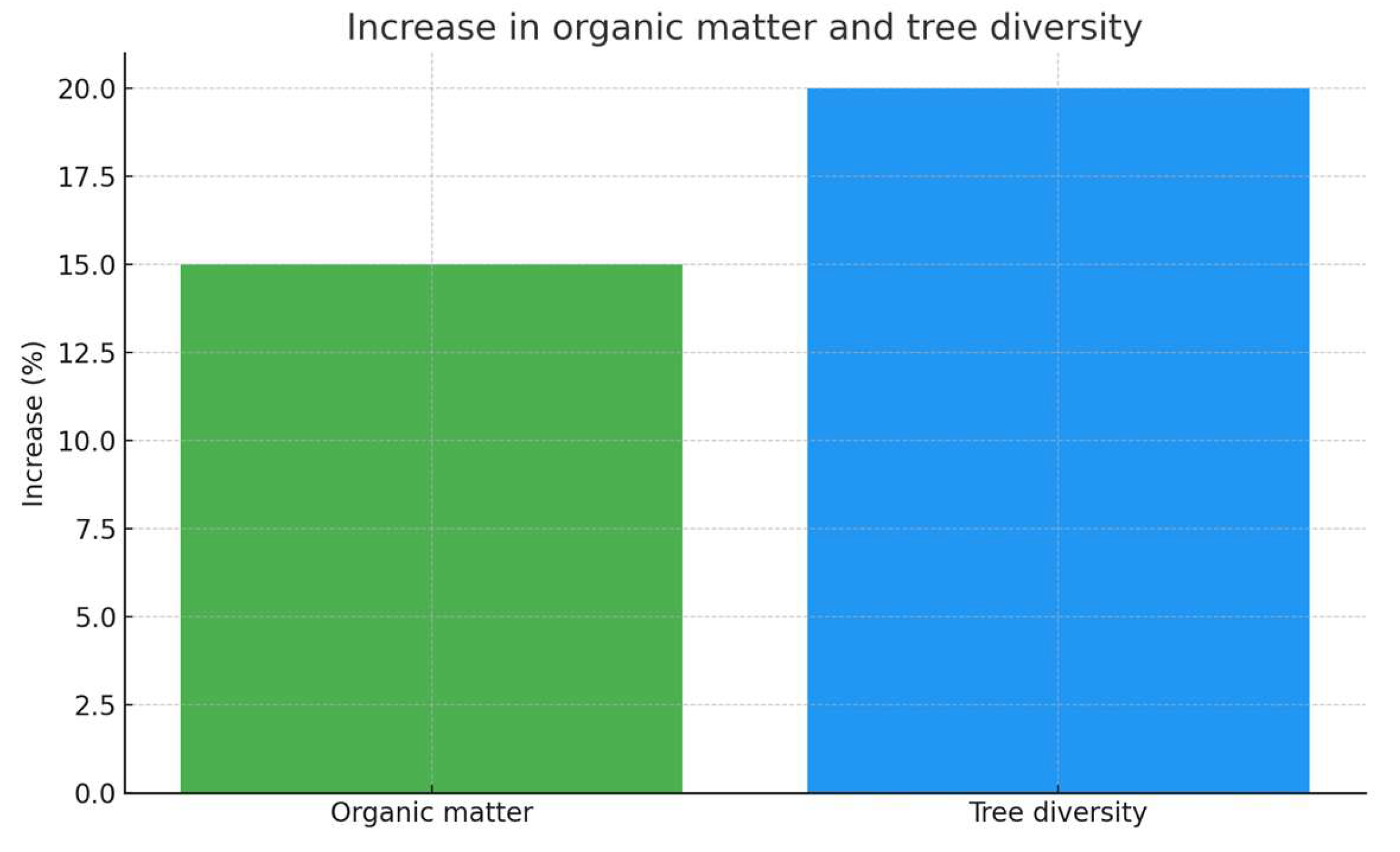

Soil analysis indicated a 15% increase in organic matter, while tree diversity grew by 20%, favoring functional ecosystems for integrated pest management.

Figure 1.

Increase in organic matter and tree diversity (%).

Figure 1.

Increase in organic matter and tree diversity (%).

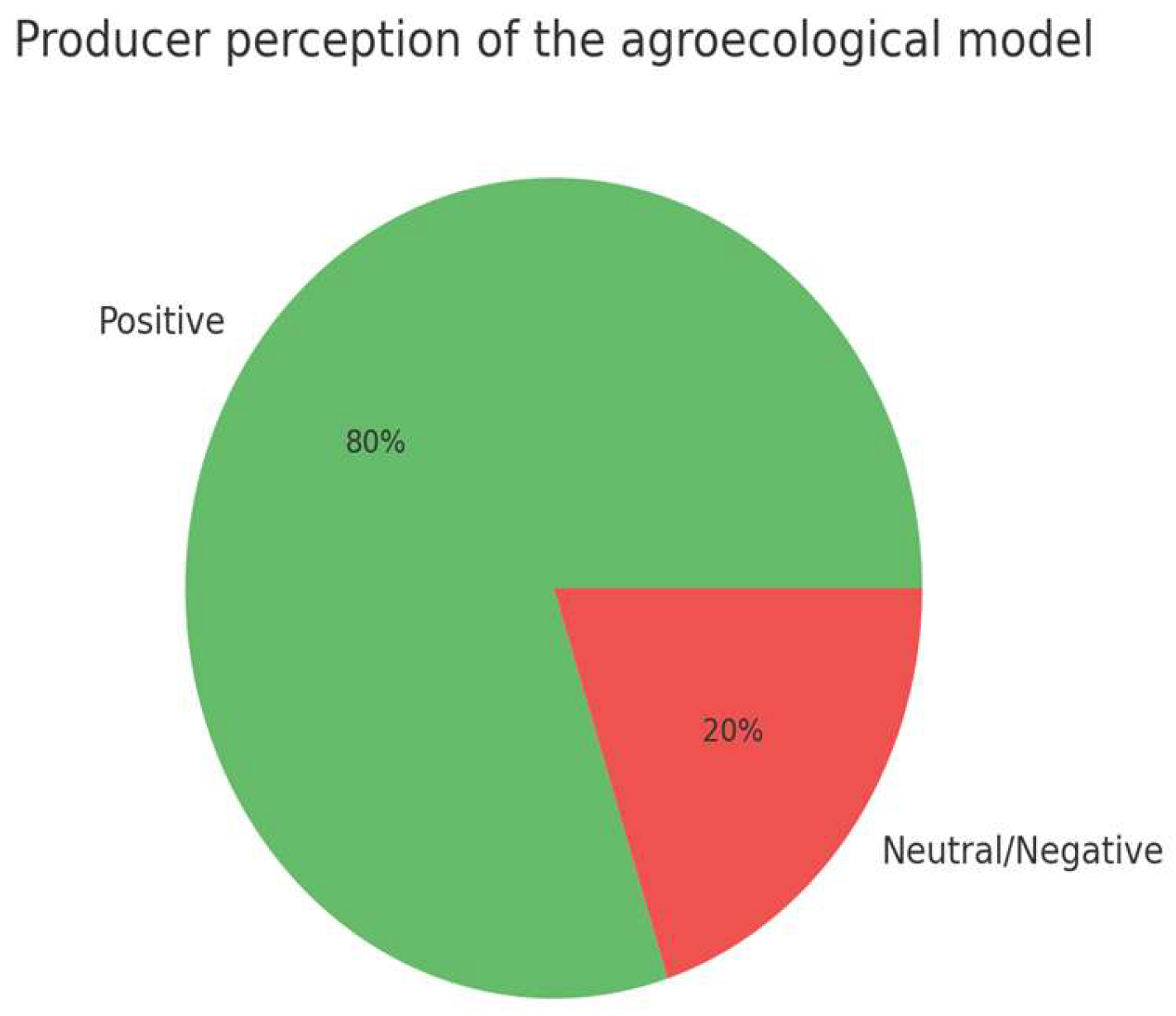

Producer Perception

Eighty percent of producers positively valued the economic and environmental benefits, although 30% requested continued technical support to improve implementation (CONACADO, 2025).

The fact that 80% of producers positively valued the model (

Figure 2) is a key indicator of its success and potential for replication. However, the request for continued technical support from 30% of them highlights that, although the benefits are clear, the transition requires sustained accompaniment to ensure its effective and long-term implementation.

The

Figure 3 would feature a single line connecting three data points:

Year 0: A point at 800 kg/ha, representing the average productivity before the agroecological conversion began.

Year 1: The line would drop slightly to a point at 736 kg/ha, illustrating a temporary decrease in productivity. This is a common and expected result during the initial transition period, as the farms adjust to new organic practices and a reduction in chemical inputs.

Year 2: The line would then rise sharply to a point at 896 kg/ha, demonstrating a significant recovery and a final increase of 12% over the initial baseline productivity.

This line chart is a powerful visual tool that clearly shows the typical “transition curve” of agroecological farming: an initial dip, followed by a strong rebound and improved performance in the long run.

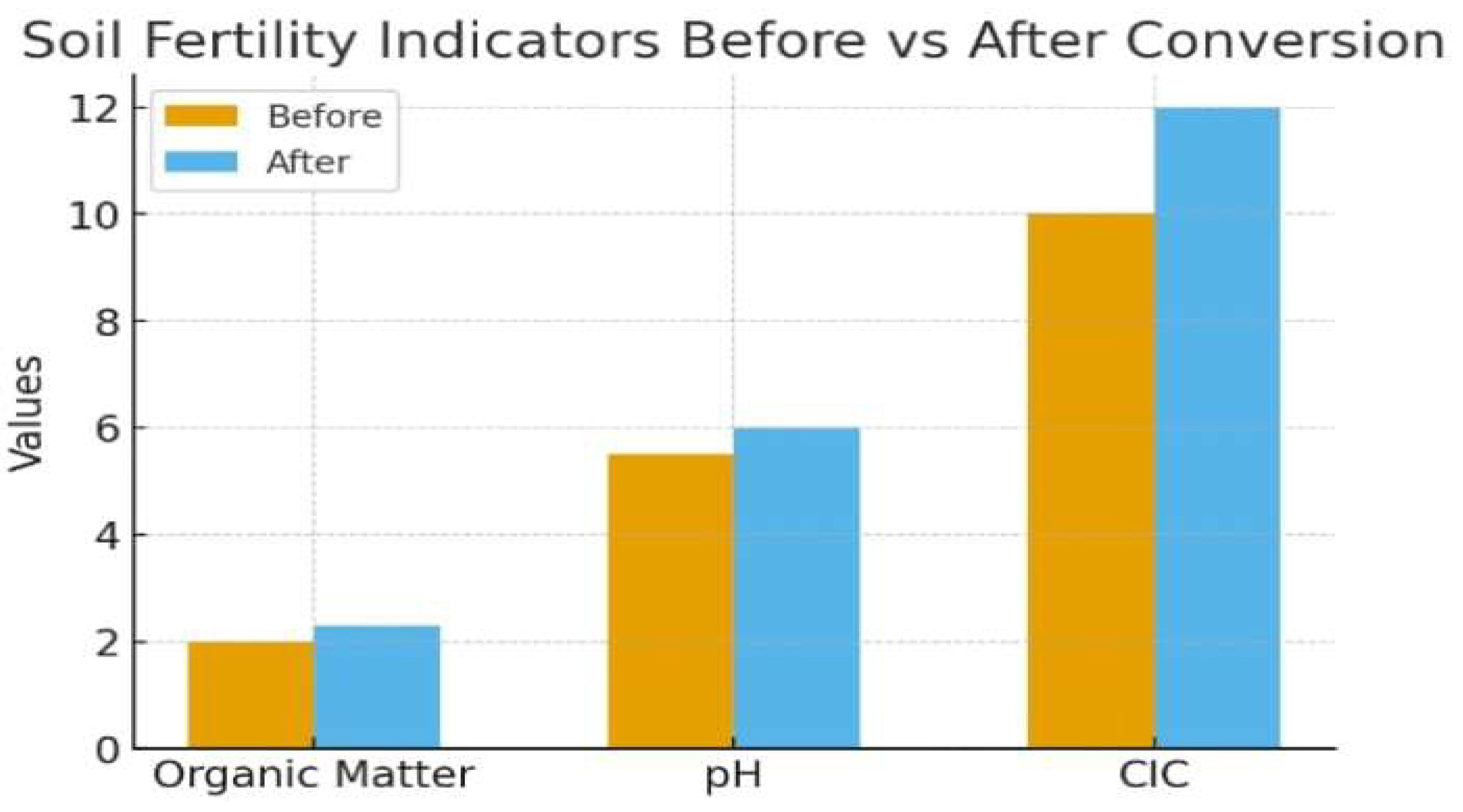

The data from

Figure 4 (Soil fertility) and the description of

Figure 1 (Increase in organic matter) are consistent with the agroecological philosophy. The 15% increase in soil organic matter is a critical indicator of soil health, as it improves water retention, nutrient availability, and microbial activity.

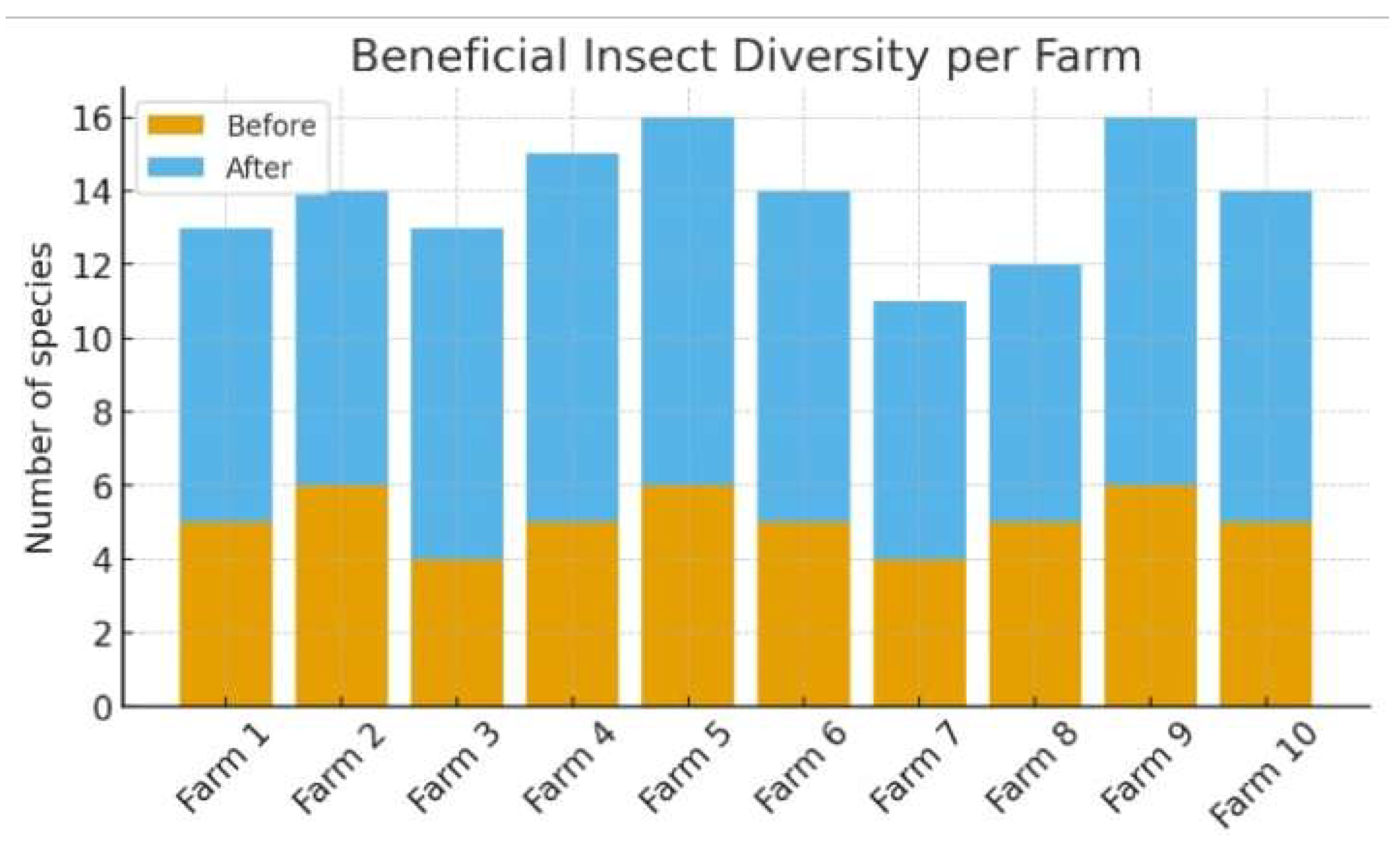

The 20% increase in tree diversity and beneficial insect diversity (

Figure 5) on the farms demonstrates the model’s success in restoring functional ecosystems. This greater biodiversity creates a more balanced system that reduces the need for pesticides, as mentioned in the study.

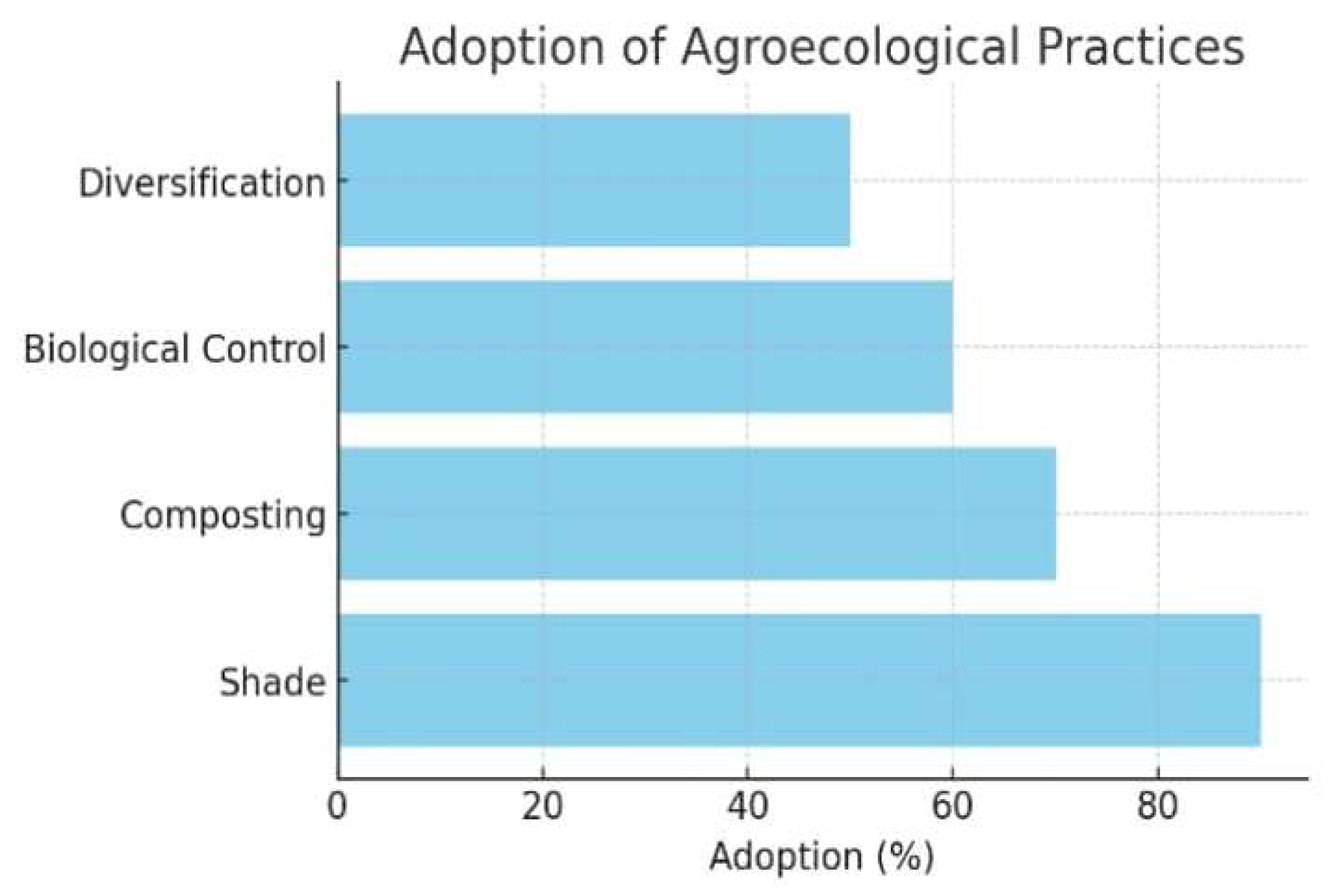

The chart you are proposing would be a horizontal bar chart, with each bar representing a specific agroecological practice. The length of each bar indicates the percentage of producers who adopted that practice during the study.

Shade Management: This bar would be the longest, extending to 90%, indicating that this was the most widely adopted practice.

Composting: This bar would reach 70%, showing a high rate of adoption.

Biological Control: This bar would be at 60%, meaning more than half of the producers implemented this practice.

Diversification: The shortest bar would reach 50%, suggesting that while it is a core agroecological principle, its adoption was lower than the other practices in this pilot phase.

This

Figure 6 visually demonstrates the success of the model’s implementation and helps identify which practices were most readily adopted by the farmers, providing valuable insights for future scaling efforts.

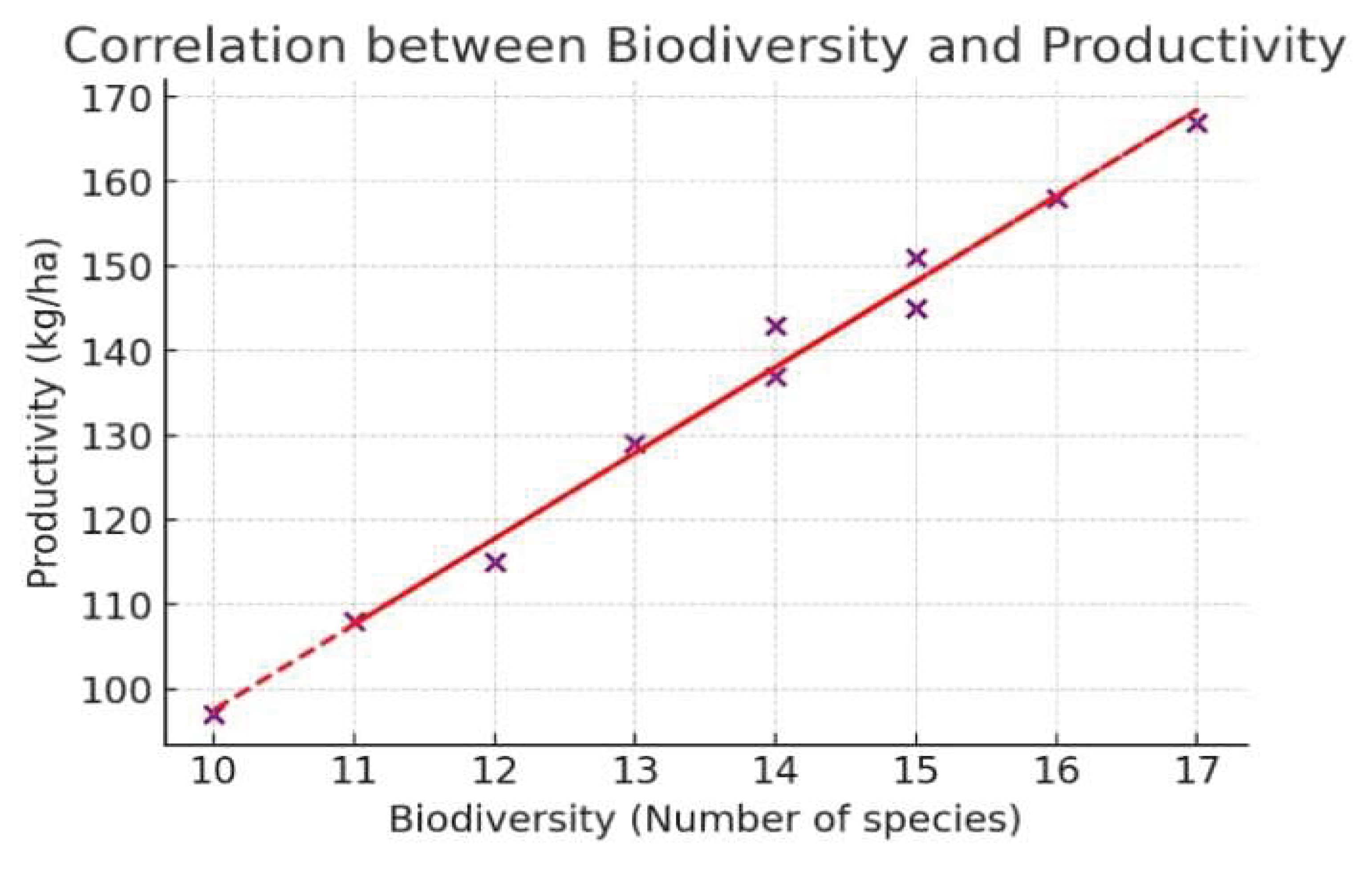

Figure 7, which shows a positive correlation between biodiversity and productivity, is one of the most important findings of the study. This result refutes the idea that sustainable agriculture must sacrifice productivity. Instead, it demonstrates that a healthier and more diversified ecosystem, achieved through agroecological practices (

Figure 6), leads to a more robust and higher-yielding productive system. This establishes a strong argument for adopting agroecology as both an economically and environmentally sound strategy.

Discussion

The results of the pilot model demonstrate that agroecology is a viable and advantageous alternative, as its findings align with national evidence indicating that agroecology demonstrates superior productivity and economic benefits compared to conventional systems (CERAI, 2024).

The initial productivity decline in year one is typical in agroecological transitions, reflecting time needed for soil recovery and biodiversity establishment (Méndez et al., 2019). The subsequent 12% increase in year two evidences the model’s capacity to outperform agrochemical-dependent systems, alongside the enhanced cocoa quality that meets international market demands (ICCO, 2023).

Increases in organic matter and tree diversity underpin ecosystem functions critical for integrated pest management and sustainable fertility, supporting international findings linking agroecology to climate resilience and conservation (Lotter, 2003; Altieri, 2020).

Producer acceptance mirrors national reports emphasizing agroecology’s social viability for income diversification and rural welfare enhancement (Codespa, 2024; CONACADO, 2025). However, continued technical support highlights the need for public policies and agricultural extension programs facilitating long-term transitions.

Finally, the model contributes to national and regional strategies for sustainable, competitive cocoa, consistent with the 2022-2032 Regional Cocoa Strategy promoting environmental impact reduction and agroecological practice adoption (SICACAO, 2022).

The evolution of productivity (

Figure 3) is a clear example of the learning curve in the agroecological transition. The initial decline in productivity in the first year (-8%) is a normal and expected phase, reflecting the time needed for soil recovery and biodiversity establishment (Méndez et al., 2019). The subsequent 12% increase in the second year demonstrates the model

’s ability to outperform agrochemical-dependent systems, in addition to enhancing the quality of cocoa to meet the demands of the international market (ICCO, 2023).

Improvements in soil fertility and biodiversity (Figure 1 and Figure 4, and 5) are crucial. The 15% increase in organic matter and the 20% growth in tree diversity strengthen ecosystem functions, such as sustainable fertility and integrated pest management, which aligns with international studies linking agroecology to climate resilience and conservation (Lotter, 2003; Altieri, 2020).

Figure 7, which shows a positive correlation between biodiversity and productivity, is a key finding that reinforces the notion that a healthy ecosystem is the foundation for a robust productive system.

The perception of producers (

Figure 2) is also a point in favor of the model. Their high acceptance reflects the social viability of agroecology for diversifying income and improving rural well-being, which aligns with reports from Codespa (2024) and CONACADO (2025). However, the request for continued technical support (

Figure 6) highlights the need for public policies and agricultural extension programs that facilitate long-term transitions.

Finally, the model contributes to national and regional strategies for sustainable, competitive cocoa, consistent with the 2022-2032 Regional Cocoa Strategy that promotes the reduction of environmental impact and the adoption of agroecological practices (SICACAO, 2022).

Conclusions

This study on the pilot model for agroecological conversion on cocoa farms associated with the National Confederation of Dominican Cocoa Growers (CONACADO) demonstrates that agroecology is a viable and superior strategy for sustainable cocoa production.

The main conclusions are as follows:

Productive Viability: Despite a slight decrease in productivity during the first year of transition, the model proved its ability to generate a 12% increase in cocoa productivity in the second year. This confirms that the productive benefits outweigh the initial challenges of the transition in the medium and long term.

Tangible Environmental Benefits: The implementation of agroecological practices led to significant improvements in the ecosystem health of the farms, including a 15% increase in soil organic matter and an increase in functional biodiversity. This is a key finding, as it establishes a direct link between environmental sustainability and a more robust and resilient productive system.

Producer Acceptance: The model showed a high level of social acceptance, with 80% of producers positively evaluating the results. This demonstrates that farmers are willing to adopt new practices when they perceive clear economic and environmental benefits.

Replication Opportunity: The results obtained on the pilot farms suggest that this model can be a replicable strategy for the cocoa sector, contributing to food security, the conservation of natural resources, and the improvement of social welfare in rural communities in the Dominican Republic.

Overall, the study provides strong evidence for the adoption of agroecology as a path toward a more competitive, resilient, and sustainable cocoa sector.

References

- Altieri, M. A. (2020). Agroecology: The science of sustainable agriculture (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- CONACADO. (2025). Informe de avance del modelo piloto de conversión agroecológica. Comité Nacional del Cacao. https://conacado.com.do/conacado-apoya-a-pequenos-productores-de-cacao-con-172-millones-de-pesos/.

- Gliessman, S. R. (2015). Agroecology: The ecology of sustainable food systems (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- ICCO. (2023). World cocoa economy: statistics and market reports. International Cocoa Organization. https://www.icco.org/statistics/.

- Lotter, D. (2003). Organic agriculture. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 21(4), 59–128. [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V. E., Bacon, C. M., & Cohen, R. (2019). Agrobiodiversity and shade coffee smallholder livelihoods. Springer.

- CONACADO. (2024). CONACADO supports small cocoa producers with 172 million pesos. https://conacado.com.do/conacado-apoya-a-pequenos-productores-de-cacao-con-172-millones-de-pesos/.

- Hoy. (2024, December 1). Cultivating cocoa requires generational renewal: an integral plan presented. https://hoy.com.do/cultivar-cacao-requiere-relevo-generacional-presentan-plan-integral/.

- CONACADO. (2025). The history of cocoa farming. https://conacado.com.do/into-the-deep-in-pacific-with-vero-eeos/.

- SICACAO. (2022). Regional Cocoa Strategy 2022-2032. http://sicacao.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Estrategia-Regional-de-Cacao-2022-2032.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).