Introduction

Fungal keratitis (FK) is a severe sight-threatening condition that often results in unilateral blindness and eye loss. It is typically caused by

Aspergillus spp.,

Candida spp., and several species of the genus

Fusarium [

1]. The annual global incidence of FK is not clearly known but highest incidences are estimated to be in Asia (34 per 100,000 people) and Africa (14 per 100,000 people) [

2]. However, in developed countries, the prolonged contact lens use, ocular surface diseases (e.g., dry eye), and the widespread use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and chemotherapeutic drugs have increased the incidence of FK, over the past decade [

3,

4,

5]. The current therapeutic approach involves both topical and systemic antifungal therapies, and surgical intervention when necessary. Concerning topical antifungal therapy, voriconazole and natamycin are the most used drugs, with the latter being shown to be clinically more successful [

6]. Systemic antifungal therapy is used in severe cases of FK, including those with deep corneal involvement, impending corneal perforation, or endophthalmitis. Oral voriconazole and itraconazole are the most used systemic antifungal agents for FK, with voriconazole being preferred because of its better corneal penetration and broad-spectrum antifungal activity [

7]. In cases where medical therapy fails or in the presence of complications such as corneal perforation, surgical intervention may be necessary. This may involve therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PK), and conjunctival flaps, in cases where PK is not feasible or in patients with poor visual potential. Nevertheless, these surgical procedures may have complications, such as recurrence of infection, endophthalmitis, and graft rejection [

8]. Therefore, FK is still a major challenge to treat and alternative strategies to overcome the limited efficacy of currently available antifungal agents are urgently needed.

Essential oils (EOs) are complex mixtures of volatile compounds obtained through distillation or mechanical pressing from aromatic plants. They are characterized by their diverse chemical profiles, which may include terpenes, phenols, aldehydes, and other bioactive constituents. Each EO possesses a unique composition of chemicals, influencing its spectrum of biological activities [

9]. The medical relevance of EOs has gained considerable attention in recent years, with a focus on their potential roles in therapeutics, disease prevention, and overall health promotion. In recent years, EOs have been explored as potential antifungal agents.

Eucalyptus globulus EO was shown to have antifungal efficacy against a range of pathogenic fungi, including

Candida,

Aspergillus, and

Fusarium spp. [

10]. Also, cinnamon leaf EO was found to significantly inhibit the fungal growth [

11]. The antifungal effect of EOs is believed to be due to their ability to disrupt the cellular integrity of fungi, leading to their death. This is thought to occur through a variety of mechanisms, including the disruption of the plasma membrane, leading to the leakage of cellular contents, and the disruption of mitochondrial structure, leading to cell death [

12]. Additionally, EOs have shown promising results in circumventing common resistance mechanisms related to conventional antifungal agents [

13]. This ability to overcome resistance underscores the importance of exploring EOs as an alternative therapeutic approach against FK. In addition to their antifungal activity, EOs have also been found to have synergistic effects with conventional antifungal agents [

14].

In the present study, we tested the EOs extracted from

Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf and

Lavandula pedunculata (Mill.) Cav., for their antifungal activity against selected fungal pathogens isolated from FK patients.

The Cymbopogon citratus EO is known to have significant antifungal and antibacterial activities. Its main component, geranial, is believed to disrupt the cell membrane of fungi and bacteria, leading to cell death. Studies have demonstrated its effectiveness against a variety of pathogens, including

Candida spp. [

15] and

Fusarium spp. [

16]. The

Lavandula pedunculata EO has also been documented for its antifungal properties against a range of dermatophytes, including those responsible for skin infections [

17,

18]. Moreover, both

Cymbopogon citratus and

Lavandula pedunculata EOs are known for their safety and tolerability when used topically, making them suitable candidates for therapeutic applications. Their relatively low toxicity, compared to synthetic antifungal agents, minimizes the risk of adverse effects in patients [

19]. Here, we hypothesise that

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO extracted from aromatic and medicinal plants may be effective against fungal pathogens associated with FK. We collected corneal samples from FK patients in two Portuguese hospitals – University Hospital Center of São João (Porto), and Coimbra University Hospital (Coimbra), identify them and studied their in vitro response to

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO. Our study aims to contributed to the validation of EOs as effective, safe, and sustainable therapeutic agents for FK, providing an alternative to current antifungal treatments.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Ethical Issues

This hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out in two Portuguese hospitals: University Hospital Center of São João, based in Porto (northern region of Portugal), and Coimbra University Hospital, based in Coimbra (central region of Portugal) between February and September 2023. All procedures were conducted following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra, Portugal (approval No. CE-128/2023). From each patient with a clinical diagnosis of FK, data were recorded, including the age, sex, predisposing risk factors, prior ocular diseases, and visual acuity at presentation and after treatment.

Collection and Processing of Ocular Samples

Following the ocular examination of each patient with suspected infectious keratitis, the cornea was anesthetized with topical oxybuprocaine 4 mg/mL (Anestocil®, EDOL, Portugal), and corneal specimens were collected under sterile conditions and following the safety protocols.

The processing of ocular samples and identification of the fungal pathogens were performed according to the protocol implemented in each hospital microbiology laboratory. In the Coimbra University Hospital (Coimbra, Portugal), a portion of each of the acquired specimens was carefully placed on a sterile glass slide for immediate microscopic analysis; the remaining part was sent to the microbiology laboratory, where it was inoculated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) culture medium, supplemented with chloramphenicol and gentamicin. The inoculated SDA media were then incubated at 30ºC, until fungi growth is observed, for a maximum of two weeks. In the University Hospital Center of São João (Porto, Portugal), ocular samples were sent in culture medium to the microbiology laboratory, where they were cultured in blood agar (BA), chocolate agar (CA) and SDA, supplemented with chloramphenicol and gentamicin culture media. BA and CA cultures were incubated at 35ºC, in a capnophilic atmosphere, for five days, whereas SDA culture was incubated at 25ºC, for two weeks.

Molecular Identification of Fungal Pathogens

Fourteen ocular samples from fourteen patients were tested for molecular identification of fungal pathogens. Each clinical sample was inoculated in 5 plates of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium (CM139, Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) supplemented with streptomycin sulfate (20μl/L) [

20], and incubated at 24ºC, for 12 days in the dark. The media were regularly monitored for the emergence of fungal colonies. These emerging colonies were further clinically isolated to axenic cultures onto PDA, and incubated in the same conditions, and their morphologic characterization, including color, texture, and overall colony appearance was observed.

For molecular identification, axenic cultures were assayed for DNA extraction, using the REDExtract-N-Amp™ polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ReadyMix™ Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), with modifications [

20]. The DNA extract was used for molecular identification via the amplification of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-rDNA region by PCR, using the commonly used primer pair for fungal identification ITS1-F and ITS4. When the ITS region proved to be insufficient for conclusive identification, alternative genetic markers were used to increase the accuracy and specificity of the identification. The nucleotide sequence for all used primers in this study is listed in

Table S1. The obtained amplicons were purified with the EXO/SAP Go PCR Purification Kit (GRISP, Portugal), following manufacturer’s recommendations, and sequenced using an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer system (96 capillary instruments) at STABVIDA, Portugal. Furthermore, searches were performed using NCBI Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [

21]. Species identification was confirmed using macroscopic and microscopic analysis of taxonomic traits.

Preparation of Essential Oils

The extraction of EOs from

Cymbopogon citratus and

Lavandula pedunculata was performed by hydrodistillation for 3 h using a Clevenger-type apparatus, according to the protocol described in the European Pharmacopeia [

22]. Following the extraction process, the EOs were separated from the aqueous distillate, and immediately transferred to amber glass vials, and stored at 4ºC. The extracted EOs were chemically characterized using gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC/MS) by our team, previously [

23]. The EOs used in this study were obtained from the same extraction batch to ensure homogeneity, in terms of chemical composition, namely, the presence of compounds with antifungal activity.

Evaluation of Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils

The antifungal activity of Cymbopogon citratus EO and Lavandula pedunculata EO was assessed against selected yeast and molds from our study samples, namely Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and Scedosporium boydii, by solid-phase disk diffusion in vitro assay. The EOs were prepared in four concentrations (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100 (v/v%) by dilution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Sterile paper discs, with a diameter of 8 mm, were impregnated with 25 μL the corresponding dilution, ensuring uniform saturation of the disc. Spores of each filamentous fungus and cells of each yeast strain (104) were uniformly spread per 9 mm-PDA Petri dishes and left to dry. An impregnated disc was placed onto the center of each culture plate. Cultures were incubated at 30ºC, for the growth of each tested pathogen. The inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) were measured on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of incubation, twice. Experiments were conducted in triplicate. The final IZD was determined by averaging the values for the three experiments. Paper discs infused with DMSO without EOs, and without DMSO nor EOs were used as positive and negative control, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0.0.0 [

24]. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in the study were presented as mean ± SD, range and percentage. To evaluate the antifungal activity of the EOs, three independent experiments were performed for each condition (time of incubation and EOs concentration). The IZD values obtained were presented as mean ± SD. Independent t-test was performed to compare the antifungal activity between the EOs. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey

post hoc test was performed to compare the antifungal sensitivity between pathogens. Repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction followed by

post hoc Bonferroni analysis was performed to compare the antifungal activity of the EOs during the study (ie., on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of incubation). The difference was considered significant, if the

p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Characterization of Fungal Keratitis Patients

A total of fourteen ocular fungal infection samples were successfully collected from fourteen patients in two Portuguese university hospitals over 8-months period (from February to September 2023), ensuring a representative sampling of the FK cases in northern and central Portugal. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the donor patients are described in

Table 1. Molds and yeasts were equitably identified in the samples collected. The FK patients’ mean age was 63 ± 17 years (range 20-84), with 57.1% (n=8) being male. Molds were identified in younger patients (56 ± 20 years), and mostly in men (71.4%, n=5). Yeasts were identified in older patients (70 ± 10 years), and mostly in women (57.1%, n=4). Main risk factors were found to be ocular surface disease (28.6%, n=4) and previous keratoplasty (28.6%, n=4). Molds infections were mostly found in contact lenses use (21.4%, n=3), whereas previous keratoplasty was mainly observed in yeast infections (42.9%, n=3). Most samples were collected in spring (42.9%, n=6) and summer (42.9%, n=6). Although mold infections were observed mainly in summer (57.1%, n=4), yeast infections were found from winter to summer. The mean visual acuity (VA) (logMAR) was 1.15 ± 1.04 units at initial presentation and worsened to 1.54 ± 1.06 units, by the end of the treatment. Patients diagnosed with mold infection presented better VA than those diagnosed with yeasts infections. The VA changed from 0.33 ± 0.40 units to 0.87 ± 0.63 units, in the mold group, and from 1.74 ± 0.96 units to 2.03 ± 1.07 units, in the yeast group. The individual characterization of patients is presented in

Table S2.

Molecular Identification of Fungal Pathogens

The DNA sequences of the clinical isolates were compared with those in the NCBI BLAST database to establish the best match and determine the similarity percentages (

Table 2). A graphical representation of the distribution and prevalence of different fungal species in the

collected samples is presented in

Table 3.

Candida spp., particularly

Candida albicans and

Candida parapsilosis, were found to be the more prevalent, representing 28.6% (n=4) and 21.4% (n=3), respectively, of the total sample. Other clinical isolates were identified as

Beauveria bassiana,

Scedosporium boydii, and

Aspergillus fumigatus (7.1%, n=1). We also identified unusual strains, namely,

Dicyma olivacea (14.2%, n=2),

Epicoccum nigrum, and

Penicillium tealii (7.1%, n=1).

Table 2.

Identification of fungal pathogens from ocular clinical isolates.

Table 2.

Identification of fungal pathogens from ocular clinical isolates.

| Clinical isolate number |

Fungal species |

NCBI BLAST ® similarity (%) |

| 1 |

Aspergillus fumigatus |

97.9 |

| 2 |

Beauveria bassiana |

99.8 |

| 3 |

Candida albicans |

99.8 |

| 4 |

Candida albicans |

100.0 |

| 5 |

Candida albicans |

99.8 |

| 6 |

Candida albicans |

99.8 |

| 7 |

Candida parapsilosis |

100.0 |

| 8 |

Candida parapsilosis |

100.0 |

| 9 |

Candida parapsilosis |

100.0 |

| 10 |

Dicyma olivacea |

99.6 |

| 11 |

Dicyma olivacea |

99.8 |

| 12 |

Epicoccum nigrum |

99.8 |

| 13 |

Penicillium tealii |

99.6 |

| 14 |

Scedosporium boydii |

100.0 |

Table 3.

Distribution and prevalence of fungal pathogens from ocular clinical isolates.

Table 3.

Distribution and prevalence of fungal pathogens from ocular clinical isolates.

| Fungal species |

Number of clinical isolates |

Percentage (%) |

| Molds |

7 |

50.0 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus |

1 |

7.1 |

| Beauveria bassiana |

1 |

7.1 |

| Dicyma olivacea |

2 |

14.2 |

| Epicoccum nigrum |

1 |

7.1 |

| Penicillium tealii |

1 |

7.1 |

|

Scedosporiumboydii

|

1 |

7.1 |

| Yeasts |

7 |

50.0 |

| Candida albicans |

4 |

28.6 |

| Candida parapsilosis |

3 |

21.4 |

In Vitro Evaluation of Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils

The antifungal efficacy of

Cymbopogon citratus and

Lavandula pedunculata EOs against four selected fungal pathogens associated with FK, namely,

Aspergillus fumigatus (clinical isolate number 1),

Candida albicans (clinical isolate sample number 6),

Candida parapsilosis (clinical isolate sample number 9), and

Scedosporium boydii (clinical isolate sample number 14), is shown in

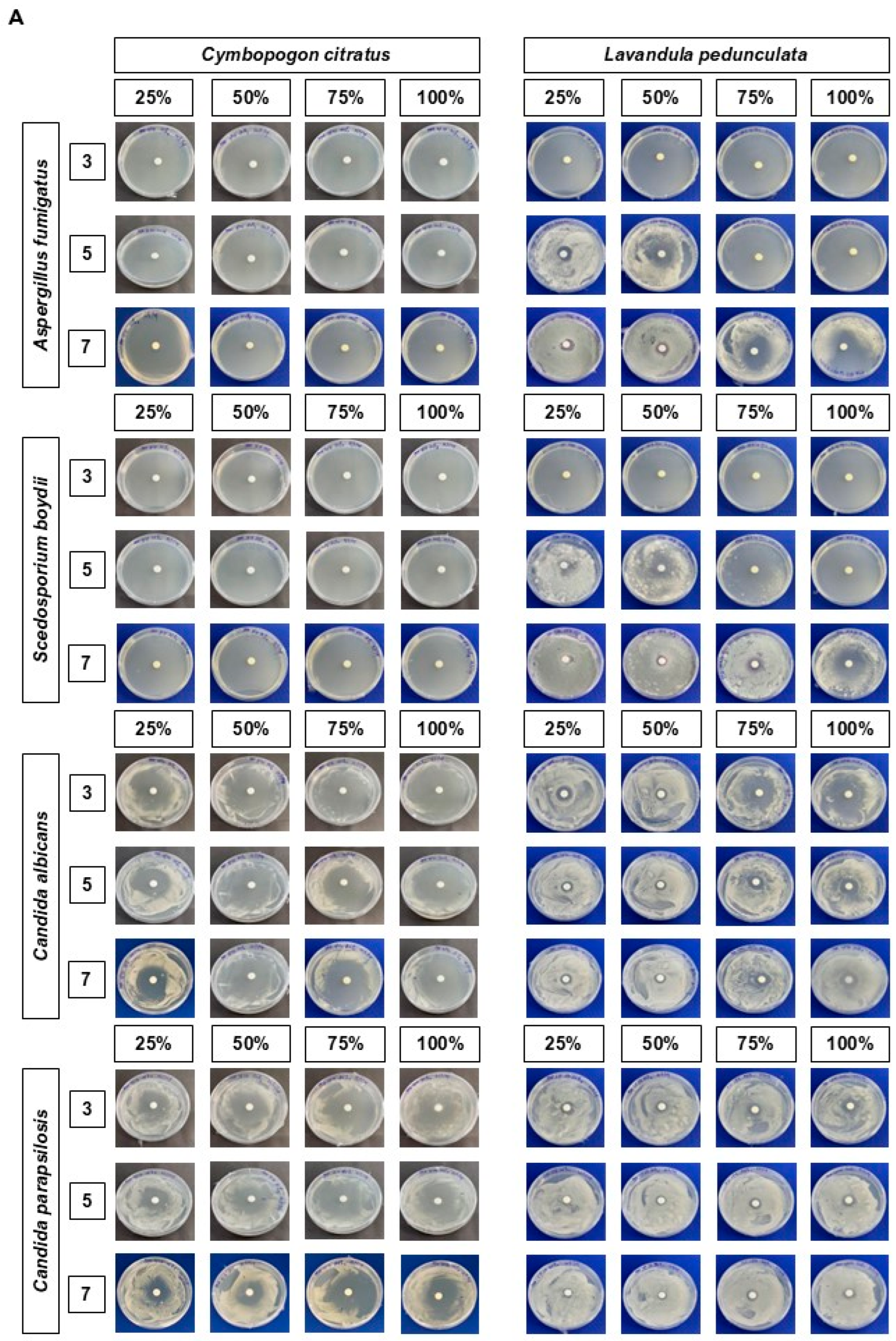

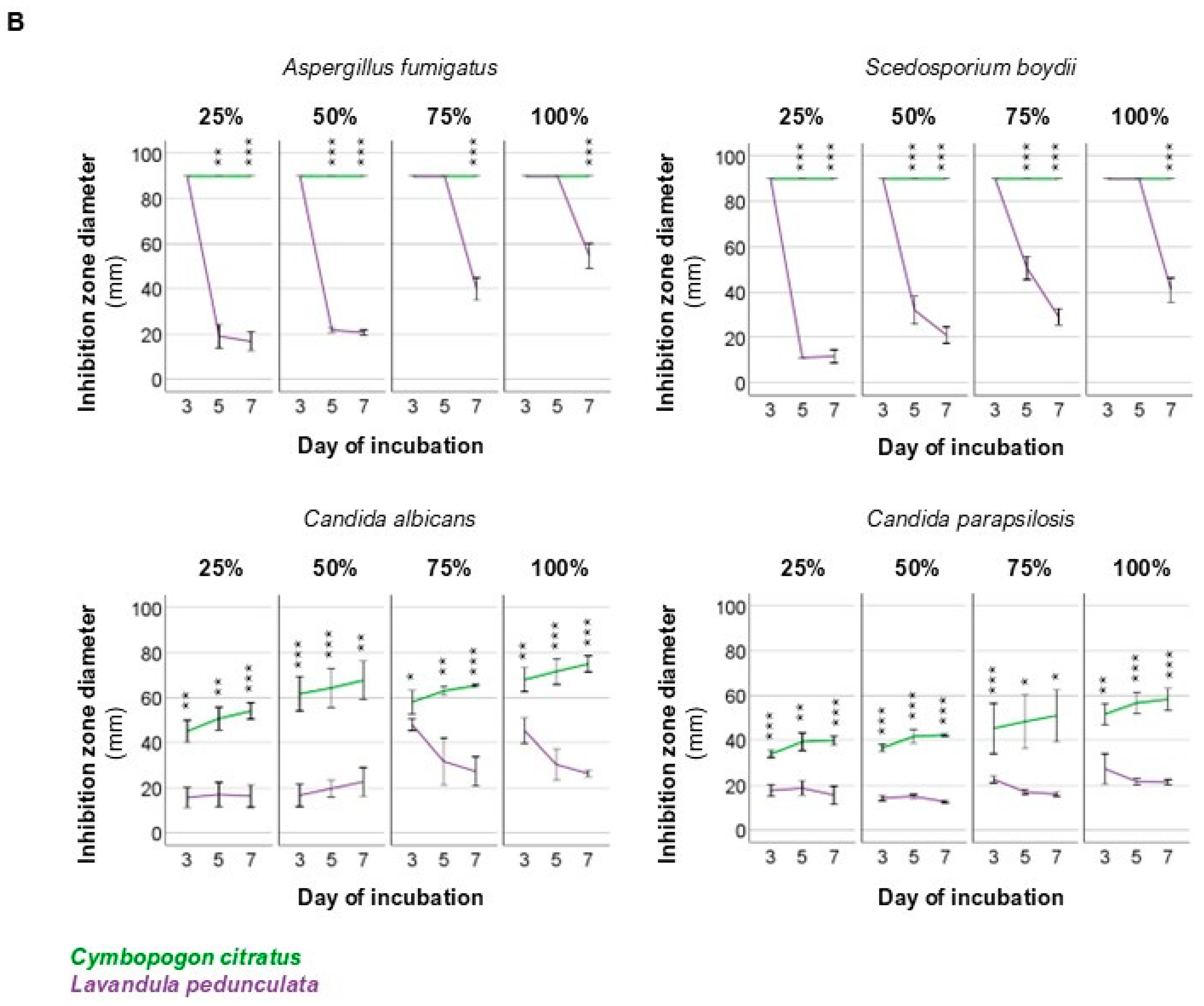

Figure 1.

Figure 1A shows representative images of solid-phase disk diffusion in

vitro assay. IZD values are plotted in

Figure 1B. Detailed values are listed in

Table S3.

We found that the antifungal activity of Cymbopogon citratus EO was the same or statistically significantly higher than Lavandula pedunculata EO, against all clinical isolates tested, in the different concentrations and time of incubation.

We analyzed the antifungal activity of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO against selected clinical isolates (

Figure S1). We found that

Cymbopogon citratus EO had the maximum value of antifungal activity (IZD = 90 mm) against

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Scedosporium boydii, regardless of the concentration and the incubation time. Statistically lower IZD values were measured for

Candida albicans which varied between 45.0 ± 5.0 mm and 75.0 ± 3.6 mm, and for

Candida parapsilosis, which varied between 34.0 ± 1.7 mm and 58.3 ± 4.9 mm, during the incubation time, in different concentrations. IZD values for

Candida albicans were statistically significantly higher than for

Candida parapsilosis, except in the concentration of 75%. Concerning

Lavandula pedunculata EO, the antifungal activity to the different pathogens changed with the incubation time.

Against

Aspergillus fumigatus, IZD values ranged from 90.0 mm to 16.7 ± 4.2 mm, whereas, against

Scedosporium boydii, IZD values ranged from 90.0 mm to 11.0 mm.

Candida albicans and

Candida parapsilosis presented IZD values, ranging from 48.0 ± 2.6 mm and 16.3 ± 5.0 mm, and from 27.3 ± 6.8 mm and 12.7 ± 0.6 mm, respectively. In the concentration of 25%,

Lavandula pedunculata EO presented statistically significantly higher antifungal activity against

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Scedosporium boydii than against

Candida albicans and

Candida parapsilosis, only on the 3rd day of incubation. On the 5th and 7th day of incubation, IZD values decreased, and no statistically significant difference was observed between the antifungal activity against the tested pathogens. In the concentration of 50%, a similar profile was obtained, except that

Lavandula pedunculata EO showed statistically significantly higher antifungal activity against

Scedosporium boydii, still on the 5th day of incubation. In the concentrations of 75% and 100%,

Lavandula pedunculata EO showed statistically significantly higher antifungal activity against

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Scedosporium boydii than against

Candida albicans and

Candida parapsilosis, except on the 7th day of incubation. Concerning the antifungal activity against

Candida albicans and

Candida parapsilosis, no statistically significant difference was observed, except on the 3rd day of incubation.

We evaluated the effect of the concentration of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO on the antifungal activity (

Figures S2A and S2B). We found no statistically significant difference between the concentrations of

Cymbopogon citratus EO, in general. The antifungal activity against

Candida albicans was statistically significantly higher in the concentration of 100% compared to the concentration of 25%, at all days of incubation; moreover, the antifungal activity was statistically significantly higher in the concentration of 50% compared to the concentration of 25%, on the 3rd and 7th days of incubation.

Lavandula pedunculata EO presented highest antifungal activity against

Aspergillus fumigatus, regardless the concentration, on the 3rd day of incubation; on the 5th day of incubation, IZD values decreased significantly, in the concentration of 50% and 25%, while remaining the same, in the concentration of 100% and 75%; on the 7th day of incubation, IZD values in the concentration of 25% and 50%, were statistically significantly lower compared to the concentration of 75% and 100%. Concerning the antifungal activity against

Candida albicans, differences were obtained only on the 3rd day of incubation, when the IZD values in the concentration of 25% and 50% were statistically significantly lower compared to the concentration of 75% and 100%. The antifungal activity against

Candida parapsilosis was similar, whatever the concentration, on the incubation days tested. Exception was that IZD values in the concentration of 50% were statistically significantly lower compared to the concentration of 100%.

Lavandula pedunculata EO presented maximum antifungal activity against

Scedosporium boydii, regardless the concentration, on the 3rd day of incubation; on the 5th day of incubation, IZD values in the concentration of 75% were statistically significantly higher compared to the concentration of 50%, as well as between the concentration 50% and 25%, while in the concentration of 100% remained the highest; on the 7th day of incubation, IZD values in the concentration of 100% were statistically significantly higher compared to the concentration of 75%, 50% and 25%.

We also assessed the antifungal activity of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO throughout the time (

Figures S2A and S2C). We found not statistically significantly differences in the antifungal activity of

Cymbopogon citratus EO against

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Candida albicans and

Scedosporium boydii during the incubation time, at each concentration tested. Concerning

Candida parapsilosis, IZD values were statistically significantly increased from the 3rd to the 7th day, in the concentration of 25%, 50%, and 75%, and from the 5th to the 7th day, in the concentration of 75%. Conversely, the antifungal activity

Lavandula pedunculata EO against

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Candida albicans and

Scedosporium boydii decreased with time. Regarding

Aspergillus fumigatus, a statistically significant decrease was observed from the 3rd to the 5th day, in the concentration of 25% and 50%, while in the concentration of 75% and 100%, a statistically significant decrease was observed from the 5th to the 7th day. In case of

Scedosporium boydii, IZD values statistically significantly decreased from the 3rd to the 5th day, in the concentration of 25% and 50%, and from the 5th to the 7th day, in the concentration of 100%; in the concentration of 75%, IZD values significantly decreased during the study. Concerning

Candida albicans, a statistically significantly decreased from the 3rd to the 5th day, in the concentration of 100%. No statistically significantly differences were observed in the antifungal activity of

Lavandula pedunculata EO throughout the time against

Candida parapsilosis.

Discussion

FK is characterized by the infection of the cornea by fungal species. It was a condition with a high incidence in agrarian communities, attributed to occupational exposure to vegetative matter. Nowadays, the widespread use of contact lens, corticosteroids, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and chemotherapeutic drugs have increased the incidence of FK [

4,

5]. WHO has recently identified fungal infections as one of the major threats to human health, namely due to the lack of efficacy of current antifungals agents [

25]. Focus on research to strengthen the global response to fungal infections is needed. The complexity of FK etiology, encompassing a vast array of fungal pathogens, each with unique susceptibilities and resistance profiles, underscores the necessity for a broad-spectrum and effective treatment approach. Current therapeutic strategies, predominantly reliant on antifungal medications, are hampered by issues such as drug resistance, limited ocular penetration, and toxicity, which collectively compromise their effectiveness.

Herein, we explored the in vitro antifungal activity of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO derived from well-known aromatic and medicinal plants, against fungal pathogens obtained from corneal samples collected from FK patients in two Portuguese university hospitals. This study aimed to be the first step on the validation of these EOs as an alternative treatment of FK. The choice of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO was based on their known bioactive compounds that exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy, including antifungal activities. The chemical characterization of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO previously performed [

23] showed the presence of compounds with proved antifungal properties, provided a scientific basis for their potential efficacy against FK pathogens. Here, the antifungal assays, demonstrating significant inhibitory activity of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO against

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and

Scedosporium boydii, key fungal species associated with FK, suggests that EOs may act as effective therapeutic agents for FK. Considering the antifungal assay results for

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO, it is imperative to delve deeper into the implications of these findings for developing antifungal treatments for FK. The efficacy of

Cymbopogon citratus EO and

Lavandula pedunculata EO, particularly against filamentous fungi, which are often more challenging to treat due to their complex structures and resistance mechanisms, highlights their potential as a cornerstone in FK therapy. Regarding their apparently less efficacy for the yeasts tested, more studies are needed, namely with other methodology like the standardized dilution method and the use of more fungal species.

A significant inference from our findings is the potential mechanisms through which EOs exert their antifungal effects. The multi-targeted action of EOs, capable of disrupting fungal cell membranes, inhibiting spore germination, and interfering with fungal metabolism, presents a significant advantage over conventional antifungals, which often target a single cellular pathway, making them susceptible to resistance mechanisms. As EOs are a mix of compounds, it is imperative to acknowledge the inherent volatility of these compounds. This characteristic suggests that a portion of the observed antifungal activity may be attributable to the volatile fraction of the oils, rather than solely their diffusion through the culture media. The volatility of EOs implies that their action might not be confined to direct contact mechanisms but could also encompass airborne antifungal and fungistatic effects. A potential future direction for this research involves comprehensive analytical separation and characterization of the constituents within EOs to clarify the bioactive components responsible for antifungal activity. Such an approach would enable a detailed comparison of the effects attributable to direct diffusion through the culture medium against those derived from the volatile fraction of the EOs. By employing advanced fractionation techniques alongside mass spectrometry and chromatography, researchers could identify specific compounds that contribute to the observed biological effects and distinguish between the contact-dependent and volatile-mediated actions of the EOs against fungal pathogens.

Besides further elucidating the mechanisms underlying the antifungal effects of Cymbopogon citratus EO and Lavandula pedunculata EO, future research should also focus on optimizing formulations for enhanced ocular delivery and retention and evaluating the safety and efficacy of these EOs in vivo. Additionally, the potential for synergistic effects with conventional antifungal agents warrants investigation, as such combinations could enhance treatment efficacy, reduce drug resistance, and broaden the therapeutic window for FK treatments. The translation of these findings into clinical practice, however, requires a cautious approach, considering the safety and pharmacokinetic profiles of the EOs. The potential for toxicity, irritation, or allergic reactions, especially in the sensitive ocular environment, is a critical consideration. Therefore, future studies should include detailed toxicological assessments, formulation studies to enhance ocular delivery and retention, and ultimately, clinical trials to establish efficacy, safety, and dosing guidelines for EO-based treatments for FK.

Importantly, our study provides an insight into the importance of biodiversity, as these medicinal plants represent an invaluable repository of bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic applications. This research thus advocates for a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing ethnobotany, phytochemistry, microbiology, pharmacology, and medicine to explore the full spectrum of possibilities offered by natural products in addressing contemporary health challenges.

The implications of these findings extend beyond the direct treatment of FK. The demonstrated antifungal activity of Cymbopogon citratus EO and Lavandula pedunculata EO reinforces the value of natural products in pharmaceutical development, offering a rich source of bioactive compounds for drug discovery. Moreover, the exploration of EOs in antifungal therapy highlights the value of integrating traditional knowledge with modern scientific methodologies to unlock novel therapeutic potentials. This approach is particularly pertinent in the face of escalating antimicrobial resistance, which poses a global health threat.

Conclusions

The focus on EOs is not only innovative but also timely, considering the urgent need for novel treatments of FK that can overcome the limitations of existing strategies. The in vitro antifungal assays showed the efficacy of Cymbopogon citratus EO against selected of FK pathogens, particularly molds, envisaging its viability as an effective antifungal agent. Concerning Lavandula pedunculata EO, while it exhibited significant initial antifungal effect, its efficacy decreased over time, indicating a need for further optimization to explore its full therapeutic potential. This study highlights the potential of these natural products to address the limitations of current FK therapies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., C.C., A.M.R., E.J.C.; Methodology, N.M., C.C., A.M.R., E.J.C.; Formal Analysis, E.A., N.M., C.C., E.P., L.P., A.C., R.T., D.P., J.P.C., A.M.R., E.J.C.; Investigation, E.A., E.P., L.P., A.C., R.T. D.P., J.P.C.; Resources, N.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, E.A.; Writing – Review & Editing, N.M., C.C., A.C., D.P., J.P.C., A.M.R., E.J.C.; Supervision, N.M., A.M.R., E.J.C.; Project Administration, A.M.R., E.J.C.; Funding Acquisition, A.M.R., E.J.C. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the Portuguese Society of Ophthalmology (SPO), through the Clinical Research Support Grant 2022. EJC is financially supported by Foundation for Science and Technology through the Institutional Scientific Employment program 2nd edition (CEECINST/00038/2021/CP2781/CT005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

procedures were conducted following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra, Portugal (approval No. CE-128/2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

BA: Blood Agar; BLAST: NCBI Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; CA: Chocolate Agar; DMSO: Dimethyl Sulfoxide; EOs: Essential Oils; FK: Fungal Keratitis; GC/MS: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; ITS: Internally Transcribed Spacer; IZD: Inhibition Zone Diameter; PK: Keratoplasty; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PDA: Potato Dextrose Agar; SDA: Sabouraud Dextrose Agar

References

- Trovato, L.; Marino, A.; Pizzo, G.; Oliveri, S. Case Report: Molecular Diagnosis of Fungal Keratitis Associated With Contact Lenses Caused by Fusarium solani. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 579516. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Leck, A.K.; Gichangi, M.; Burton, M.J.; Denning, D.W. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. The Lancet Infectious diseases 2021, 21, e49-e57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.T. Agreement between in vitro fungal drugs sensitivity tests and clinical response to treatment in fungal keratitis. Coimbra: University of Coimbra; 2020.

- Cunha, A.M.; Loja, J.T.; Torrão, L.; Moreira, R.; Pinheiro, D.; Falcão-Reis, F.; Pinheiro-Costa, J. A 10-Year Retrospective Clinical Analysis of Fungal Keratitis in a Portuguese Tertiary Centre. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ) 2020, 14, 3833-3839. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Galal, M.; Kulkarni, B.; Elalfy, M.S.; Lake, D.; Hamada, S.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Fungal Keratitis in the United Kingdom 2011-2020: A 10-Year Study. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Bagga, B.; Singhal, D.; Nagpal, R.; Kate, A.; Saluja, G.; Maharana, P.K. Fungal keratitis: A review of clinical presentations, treatment strategies and outcomes. Ocul Surf 2022, 24, 22-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Song, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Zou, W. Oral voriconazole monotherapy for fungal keratitis: efficacy, safety, and factors associated with outcomes. Frontiers in medicine 2023, 10, 1174264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, R.; Ghaith, A.A.; Awad, K.; Mamdouh Saad, M.; Elmassry, A.A. Fungal Keratitis: Diagnosis, Management, and Recent Advances. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ) 2024, 18, 85-106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezantes-Orellana, C.; German Bermúdez, F.; Matías De la Cruz, C.; Montalvo, J.L.; Orellana-Manzano, A. Essential oils: a systematic review on revolutionizing health, nutrition, and omics for optimal well-being. Frontiers in medicine 2024, 11, 1337785. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Antimicrobial potential and chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus oil in liquid and vapour phase against food spoilage microorganisms. Food Chemistry 2011, 126, 228-235. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Tu, X.F.; Thakur, K.; Hu, F.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, J.G.; Wei, Z.J. Comparison of antifungal activity of essential oils from different plants against three fungi. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2019, 134, 110821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani-López, E.; Cortés-Zavaleta, O.; López-Malo, A. A review of the methods used to determine the target site or the mechanism of action of essential oils and their components against fungi. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 44. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Wani, S.; Rasool, W.; Shafi, K.; Bhat, M.A.; Prabhakar, A.; Shalla, A.H.; Rather, M.A. A comprehensive review of the antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents against drug-resistant microbial pathogens. Microbial pathogenesis 2019, 134, 103580. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Rolta, R.; Dev, K.; Sourirajan, A. Synergistic potential of essential oils with antibiotics to combat fungal pathogens: Present status and future perspectives. Phytotherapy research : PTR 2021, 35, 6089-6100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahal, G.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Visser, A.; Tepper, P.G.; Quax, W.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Bilkay, I.S. Antifungal and biofilm inhibitory effect of Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) essential oil on biofilm forming by Candida tropicalis isolates; an in vitro study. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 246, 112188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, P.; Lin, Z. The Antifungal Activity and Action Mechanism of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) Essential Oil Against Fusarium avenaceum. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2022, 25, 536-547. [CrossRef]

- Chroho, M.; El Karkouri, J.; Hadi, N.; Elmoumen, B.; Zair, T.; Bouissane, L. Chemical composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oil of Lavandula Pedunculata from Khenifra Morocco. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1090, 012022.

- Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Dinis, A.M.; Canhoto, J.M.; Salgueiro, L.R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oils of Lavandula pedunculata (Miller) Cav. Chemistry & biodiversity 2009, 6, 1283-1292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox-Georgian, D.; Ramadoss, N.; Dona, C.; Basu, C. Therapeutic and Medicinal Uses of Terpenes. In: Joshee N, Dhekney SA, Parajuli P, editors. Medicinal Plants: From Farm to Pharmacy. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 333-359.

- Paiva, D.S.; Trovão, J.; Fernandes, L.; Mesquita, N.; Tiago, I.; Portugal, A. Expanding the Microcolonial Black Fungi Aeminiaceae Family: Saxispiralis lemnorum gen. et sp. nov. (Mycosphaerellales), Isolated from Deteriorated Limestone in the Lemos Pantheon, Portugal. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9.

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 1990, 215, 403-410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HealthCare, E.D.f.t.Q.o.M. 9th Edition of the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.). Strasbourg, France2016.

- Marques, M.P.; Neves, B.G.; Varela, C.; Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Dias, M.I.; Amaral, J.S.; Barros, L.; Magalhães, M.; Cabral, C. Essential Oils from Côa Valley Lamiaceae Species: Cytotoxicity and Antiproliferative Effect on Glioblastoma Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corp., I. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 26.0 ed. Armonk, NY2019.

- WHO. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).